The Controversial Origin of Ferruginous “Coprolites”

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Strata that contain ferruginous “coprolites” preserve no vertebrate fossils. Microfossils in the sediment may include pollen and diatoms.

- The ferruginous masses contain no inclusions of undigested material (e.g., skeletal fragments, fish scales, or vegetative fibers).

- The paucity of phosphorus precludes the possibility of excrement by a carnivore.

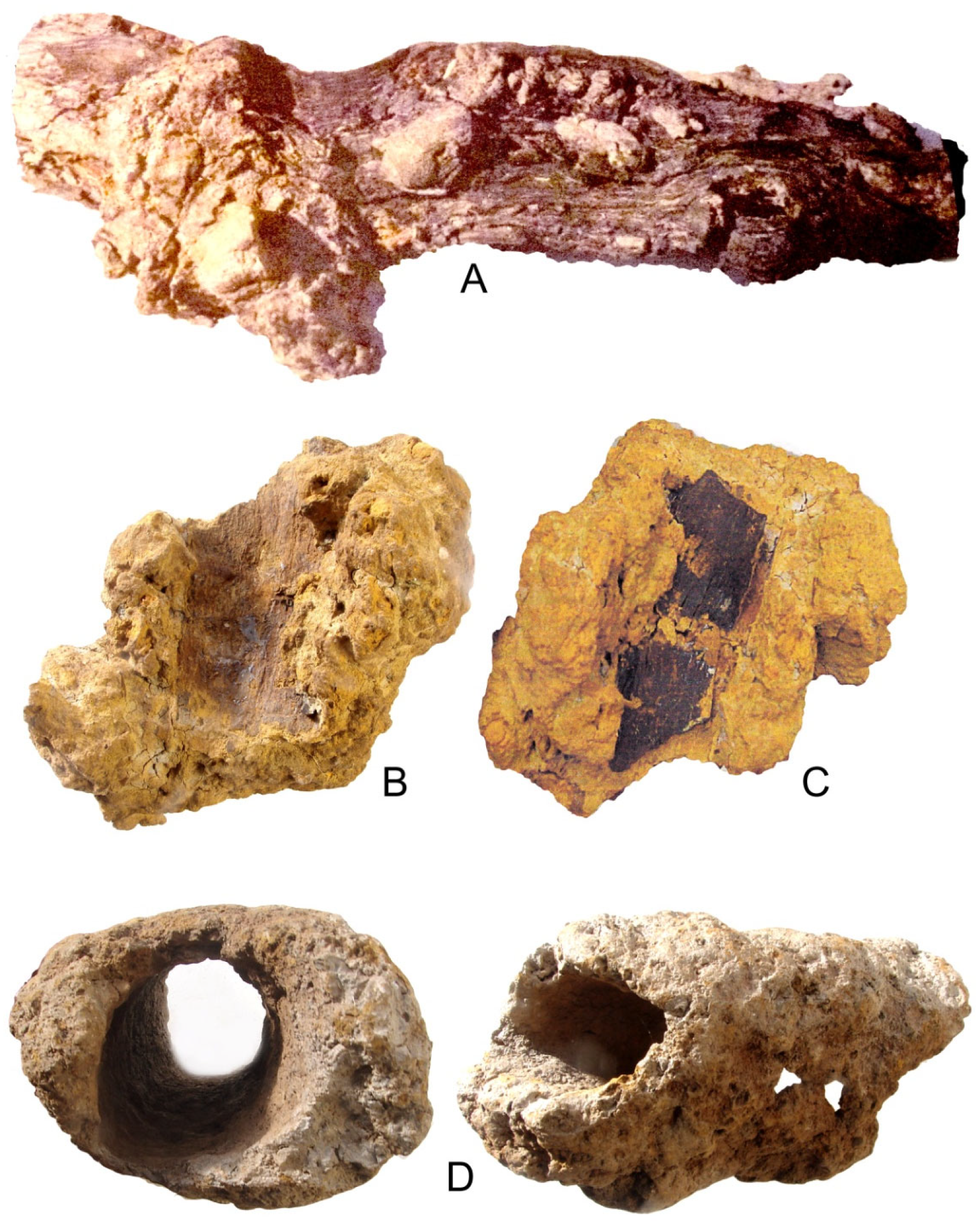

- Ferruginous masses occur in a wide range of sizes and shapes, and “coprolites” include those that can be found in strata that contains non-extrusive shapes.

- Unbiased collection shows that a large percentage of specimens are very small.

- An abundance of unmineralized wood occurs in direct association with ferruginous “coprolites”. At Salmon Creek, Washington, some coprolite-like specimens are attached to or found within ancient wood.

2. Global Occurrences

3. Materials and Methods

4. Salmon Creek, Washington

4.1. Specimen Collecting

4.2. Geologic Setting

4.3. Stratigraphy

4.4. Palynology

4.5. Evidence from Upstream Locations

4.6. Morphologies of Specimens

4.7. Transect Study

4.8. Association of “Bromalites” with Buried Wood

5. Mineralogy

5.1. Thin Section Petrography

5.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

5.3. Density

5.4. X-Ray Diffraction

5.5. Siderite Geochemistry

5.6. Oxidation Processes

5.7. Microbial Processes

6. Discussion

6.1. Uncertainties in Earlier Research

6.2. Problematic Ichnotaxonomy

6.3. Use of Problematic Specimens

6.4. Subjective Data Presentation

6.5. Fanciful Early Interpretations

6.6. Interpretations Based on Pre-Conceived Conclusions

6.7. Diagnostic Criteria for Recognizing Coprolites

- Extrusive forms: “There does not seem to be any process in geology which can produce extrusion shapes of this size or form” (p. 506, [12]).

- A flat base on the side of deposition.

- Striations typical of the great gut of mammals.

- Constantly limited length or quantity, typical for excrements.

- Variations in shape corresponding to variation in viscosity, as known from excrements

- Some forms correspond to the form of the great gut of mammals and were probably extruded as hard excrements.

- Striations can be produced in any soft material that is extruded through an aperture that has rough edges (e.g., a hollow plant stem or a knot hole). It is not a characteristic unique to the great gut of mammals.

- Constantly limited length or quantity (mass) is not a characteristic of Salmon Creek ferruginous specimens. The Amstutz [12] observations were based on specimens that were subject to biased collecting.

- Viscosity is not a diagnostic characteristic for fecal excrement. For a single individual, viscosity may vary in accordance with state of health or diet, e.g., the excremental differences between constipation and diarrhea. Also, digestive processes are highly variable among different animals. Among herbivores the large, moist excrements associated with ruminant digestion (e.g., bovid) are very different from the small, firm pellets produced by elk, deer, and rabbits. Although extrusion characteristics of soft material are strongly affected by viscosity and plasticity, there are no consistent diagnostic characteristics for fecal masses.

- This statement fails to consider the rheology of extrusion: A muscle-controlled sphincter is not required to produce extruded masses that have pointed ends. When a plastic material is extruded through a narrow opening, the terminations may be controlled by surface tension. The effects of surface tension are evidenced by the convex shape of a drop of fluid on a smooth surface. For extrusions, the object shape is likely to be determined by a pressure gradient. This can be demonstrated by soft materials excreted from aerosol cans or squeeze tubes (Figure 43). In the case of aerosol cans (e.g., shaving cream), depressing the tip button results in the extrusion of soft material that initially emerges at relatively low pressure, which quickly increases to produce uniform flow. When the spray button is released, pressure does not instantly cease. Instead, a rapid pressure decrease results in a tapered shape caused by the surface tension of the extruded material. A similar phenomenon occurs with extrusions produced with squeeze tubes (e.g., toothpaste, cake frosting). The person squeezing the tube is likely to begin and end the extrusion process with gentle pressure, pointed ends again resulting from the effects of surface tension.

6.8. Comparative Studies

6.9. Hypotheses for Abiogenic Origin

7. Summary: The Bromalite Enigma

- Despite the occurrence of immense numbers of extrusive ferruginous specimens at localities that range in age from Paleozoic to Quaternary, with the exception of the Poland locality [17] there have been no discoveries where typical coprolite features are present. These characteristics include the presence of inclusions of undigested material, and the occurrence of other fossils in the strata where the ferruginous objects occur.

- The sizes and shapes of the ferruginous specimens have great diversity. The apparent uniformity of specimens is the result of collecting bias. At Salmon Creek, the majority of in situ specimens are very small.

- The common association of ferruginous extrusions with unmineralized wood requires explanation.

- The presumption that organic-rich excrements have been completely replaced by ferruginous minerals requires an explanation that allows wood in the same stratum to remain intact.

- The possibility that the ferruginous extrusions resulted from abiogenic processes is uncertain, because of the lack of discovery of any environment where objects of similar morphology and composition are being created. Precipitation of siderite and various iron oxides and hydroxides is common in the sedimentary record, and pressures created by methane or other gases are well documented. However, there are no known situations where these processes have combined to produce bromalite-like morphologies. In summary, there are no established models for either biogenic or abiogenic production of ferruginous “bromalites”.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duffin, C.J. Records of warfare embalmed in the everlasting hills. Mercian Geol. 2009, 17, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Duffin, C.J. The earliest published record of coprolites. In Vertebrate Coprolites; Hunt, A.P., Milàn, J., Lucas, S.G., Spielmann, J.A., Eds.; Bulletin 57; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 57: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; pp. 25–28. ISSN 1524-4156. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, W. On the discovery of a new species of Pterodactyla: And also the Faeces of the Icthyosaurs; and of a black substance resembling Sepia, or India ink, in the Lias at Lyme Regis. Proc. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1829, 1, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Häntzschel, W.; El-Baz, F.; Amstutz, G.C. Coprolites: An Annotated Bibliography; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1968; 132p. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A.P.; Milàn, J.; Lucas, S.G.; Spielmann, J.A. Vertebrate Coprolites; Bulletin 57; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; 387p. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A.P.; Lucas, S.G. Descriptive terminology of coprolites and Recent feces. In Vertebrate Coprolites; Hunt, A.P., Milàn, J., Lucas, S.G., Spielmann, J.A., Eds.; Bulletin 57; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 57: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; pp. 153–170. ISSN 1524-4156. [Google Scholar]

- Vallon, L.H. Digestichnia (Vialov, 1972)—An almost forgotten ethological class for trace fossils. In Vertebrate Coprolites; Hunt, A.P., Milàn, J., Lucas, S.G., Spielmann, J.A., Eds.; Bulletin 57; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 57: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; pp. 131–136. ISSN 1524-4156. [Google Scholar]

- Zouhier, T.; Hunt, A.P.; Hminna, A.; Saber, H.; Schneider, J.; Lucas, S.H. Laurussain-aspect of the coprolite association from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) of the Argana basin, Morocco. Palaios 2023, 38, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.M. Shasta ground sloth food habits, Rampart Cave, Arizona. Paleobiology 1978, 4, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, J.I.; Agenbroad, L.D. Isotope dating of Pleistocene dung deposits from the Colorado Plateau, Arizona and Utah. Radiocarbon 1992, 34, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.R. The Hillsborough, New Brunswick mastodon and comments on other Pleistocene mastodon fossils from Nova Scotia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1993, 30, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstutz, G.C. Coprolites: A review of the literature and a study of specimens from southern Washington. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1958, 28, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conybeare, C.E.B.; Crook, K.A.W. Manual of Sedimentary Structures; Australia Department of National Development Bulletin 102: Canberra, Australia, 1968; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, P.K. The “coprolites” that aren’t: The straight poop on specimens from the Miocene of southwestern Washington state. Ichnos 1993, 2, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E. Enigmatic origin of ferruginous “coprolites”: Evidence from the Miocene Wilkes Formation, southwestern Washington. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2001, 113, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retallack, G.R. (Earth Science Department, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA). Written communication. 2025.

- Brachaniec, T.; Środek, F.; Surmik, D.; Niedźwiedzki, R.; Georgalis, G.L.; Plamcho, B.J.; Salomon, M.A. Comparative actualistic study hints at origins of alleged Miocene coprolites of Poland. PeerJ 2002, 10, 213562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.W. Paleocene Flora of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains; U.S. Geological Survey Profesional Paper 375; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1962; 119p.

- Seilacher, A.; Marshall, C.; Skinner, C.W.; Tsuihiji, T. A fresh look at sideritic “coprolites”. Paleobiology 2001, 27, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, P.L.; Simpson, F.; Whitaker, S. Preliminary observations on coprolites from the Whitemud-type facies (Late Cretaceous) of south-central Saskatchewan. In Proceedings of the Geological Association of Canada Annual Meeting, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 19–20 May 1974; p. 14, Program and Abstracts. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, P.L.; Simpson, F.; Whitaker, S.H. Late Cretaceous coprolites from southern Saskatchewan: Comments on excretion, plasticity and ichnological nomenclature. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 1977, 25, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, P.L.; Simpson, F.; Whitaker, S.H. Late Cretaceous coprolites from western Canada. Paleontology 1978, 21, 443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, P.L. Casts of vertebrate internal organs from the Whitemud Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of southern Saskatchewan. In Proceedings of the Geological Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Calgary, AB, Canada, 11–13 May 1981; p. A-6, Abstracts vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, P.L. Casts of vertebrate internal organs from the Upper Cretaceous of western Canada. J. Geol. 1981, 89, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, P.L. Ferruginous casts of bromalites in Kaolin beds: Microbial ferrihydrate-goethite transformations as early stage taphonomy in lacutrine and riparian sediments. Lethaia 2021, 54, 928–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, P.L. Fruit taphonomy and origin of hollow goethite spherulites in lacustrine sediments of the Maastrichtian Whitemud Formation, western Canada. PalZ 2022, 96, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Binda, P.L. Coprolites from the Maastrichtian Whitemud Formation of southern Saskatchewan; morphology, classification and interpretation on diagenesis. Paläontologische Z. 1991, 65, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, M. Comments on a Cretaceous coprolite from Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1970, 7, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, M.; Hopkins, W.S., Jr. Coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada, with a description of their microflora. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1970, 7, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tverdokhlebova, G.I. Coprolites of Upper Permian tetrapods as possible indicators of paleoenvironment. Paleontol. J. 1986, 2, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A.P.; Lucas, S.G. Jurassic vertebrate bromalites of the Western United States in the context of the global record. Vol. Jurassica 2014, XII, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Beadnell, H.J.K. 1901 Geological Survey Report 1899; Survey Department Public Works Ministry, National Printing Department: Cairo, Egypt, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, H.M.; Bailey, D.G.; Tewksbury, B. Pseudomorphed mineral aggregates of the Khom Chalk, Western Desert, Egypt (poster). In Proceedings of the Geological Society of America Northeastern Section Meeting, 2014, Lancaster, PA, USA, 23–25 March; 2014; Volume 46, p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, P.F.; Peleckis, G.; Buckman, S.; Archer, G. Goethite pseudomorphs after marcasite from the Gascoyne River. West. Aust. Aust. J. Mineral. 2021, 22, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A.E. Geology and Coal Resource of the Toledo-Castle Rock District, Cowlitz and Lewis Counties, Washington; United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1062; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1958; 71p.

- Brown, R.W. Table 3, List of fossil flora from Cowlitz, Toutle, and Wilkes Formations in the Toledo-Castle Rock coal district, Washington. In Geology and Coal Resource of the Toledo-Castle Rock District, Cowlitz and Lewis Counties, Washington; Roberts, A.E., Ed.; United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1062; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1958; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey, T.E.; Mustoe, G.E.; Leopold, E.B. Mudflow disturbance in latest Miocene forests in Lewis County, Washington. Palaios 2013, 28, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, T.E.; Mustoe, G.E. Depositional environments of the Wiles Formation at Salmon Creek, Washington, source of siderite “coprolite” concretions. In Proceedings of the Geological Society of America Cordilleran Section, 103rd Annual Meeting, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–6 May 2007. Abstract ID# 120944. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E.; Leopold, E.B. Paleobotanical evidence for the post-Miocene uplift of the Cascade Range. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2013, 51, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinost, A.C. Metal oxides. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment; Hillel, D., Hatfield., J.L., Powlson, C., Rosenzweig, K.M., Scow, M.J., Singer, M.J., Sparks, D.L., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 428–438. ISBN 0-12-34-8534-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cudennec, Y.; Lecerf, A. The transformation of ferrihydrite into goethite or hematite, revisited. J. Solid State Chem. 2006, 179, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillemin, A.; Wirth, R.; Kemnitz, H.; Schleichner, A.M.; Friese, A.; Bauer, K.W.; Simister, E.; Nomosatryo, S.; Ordoñez, L.; Aruztegui, F.; et al. Formation of diagenetic siderite on modern ferruginous sediments. Geology 2019, 47, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.; Moon, H.S. Iron reduction by a psychrotolerant Fe (III)-reducing bacterium isolated from ocean sediment. Geosci. J. 2001, 5, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E. Uranium mineralization of fossil wood. Geociences 2019, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota—Masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, D. Leptothrix. In Encyclopedia of Geobiology; Reitner, J., Thiel, V., Eds.; Encyclopedia of Earth Science Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 535–538. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, D.; Weiss, J.R. Bacterial iron oxidation in circumenvironmental freshwater habitats from the field and the laboratory. Geomicrobiol. J. 2004, 21, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, D.; Fleming, E.J.; McBeth, J.M. Iron-oxidizing bacteria: An environmental and genomic approach. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 64, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, R.L.; Keffer, J.L.; Polson, S.W.; Chen, C.S. Gallionellaceae pangeonomic analysis reveals insights into phylogeny, metabolic flexibility, and iron oxidation mechanisms. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 8, e00038-23. [Google Scholar]

- Hallbeck, L.; Pedersen, K. Autotrophic and mixotrophic growth of Gallionella ferrugineas evaluated by comparison of a stalk-forming and non-stalk forming strain and biofilm studies in situ. Microb. Ecol. 1995, 20, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich, S.; Sclömann, M.; Johnson, D.B. The iron-oxidizing Protobacteria. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.P.; Lucas, S.G.; Spielmann, J.A. The bromalite collection at the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution), with descriptions of new ichnotaxa and notes on other significant coprolite collections. In Vertebrate Coprolites; Hunt, A.P., Milàn, J., Lucas, S.G., Spielmann, J.A., Eds.; Bulletin 57; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 57: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; pp. 105–135. ISSN 1524-1564. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, P.L. Enigmatic origin of massive Late Cretaceous-to-Neogene coprolite-like deposits in North America: A novel paleobiological alternative to inorganic morphogenesis. Lethaia 2016, 50, 194–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, L.J. Stratigraphy and Paleobotany of the Golden Valley Formation (Early Tertiary) of Western North Dakota; Geological Society of America Memoir 150: Boulder, CO, USA, 1977; 183p. [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen, G.L. Eocene vertebrates, coprolites, and plants in the Golden Valley Formation of western North Dakota. Geol. Soc. Amer. Bull. 1963, 74, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.M. Origin of Washington “coprolites”. Mineralogist 1939, 7, 363–388. [Google Scholar]

- Dake, H.C. Washington coprolites again. Mineralogist 1960, 28, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, P.K. The method of multiple working hypotheses in undergraduate education with an example of its application and misapplication. J. Geosci. Educ. 1997, 45, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, F.F.; Clarke, J.; Sayegh, S.G.; Perez, R.J. Tubeworm fossils or relic methane expulsing conduits? Palaios 2009, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtle Poop. A Guide to Understanding It. Available online: https://www.allturtles.com/turtle-poop/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Tortoise Poop. Everything You’ve Ever Wanted to Know. Available online: https://a-z-animals.com/blog/tortoise-poop-everything-youve-ever-wanted-to-know// (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Danner, W.R. Origin of sideritic coprolite-like bodies of the Wilkes Formation, late Miocene of southwestern Washington. In Canadian Mineralogist; abstracts of the 13th annual meeting; The Mineralogical Association of Canada: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 1968; p. 571. [Google Scholar]

- Danner, W.R. The Pseudocoprolites of Salmon Creek, Washington; Report 19; Department of Geological Sciences, University of British Columba: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1994; 7p. [Google Scholar]

- Danner, W.R. The Pseudocoprolites of Salmon Creek, Washington. In British Columbia Paleontological Symposium, 2nd ed.; Abstracts; Department of Geological Sciences, University of British Columba: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, P.K.; Tuttle, F.H. Coprolites or pseudocoprolites? New evidence concerning the origin of Washington coprolites. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Program 1980, 12, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, P.K. Washington coprolites again (and again), Geological Society of America Cordilleran Section. In Proceedings of the 115th Annual Meeting, Portland, OR, USA, 15–17 May 2019; Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Volume 51. Paper #38-1. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Location | Formation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | Five Docks, New South Wales, Australia | Clay beds | [13] |

| Late Miocene | Lewis County, Washington State, USA | Wilkes Formation | [12,14,15] |

| Miocene | Madagascar | Not reported | This report |

| Miocene | Nundle, New South Wales, Australia | Not reported | [16] |

| Miocene | Poland | Turów Lignite | [17] |

| Eocene | North Dakota, USA | Fort Union Formation/Golden Valley Formation | [18,19] |

| Upper Cretaceous | Saskatchewan, Canada | Whitemud Formation | [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] |

| Upper Cretaceous | Alberta, Canada | Oldman Formation | [28,29] |

| Permian | Arkhangel’sk, Russia | Not reported | [30] |

| Upper Permian | China | Not reported | [19] |

| Locality | Informal Name | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation (Meters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWU-82177 | HB upstream | 46°23′27′′ N | 122°47′45′′ W | 48 |

| WWU 1571 | Horseshoe Bend | 46°23′26′′ N | 122°47′40′′ W | 47 |

| WWU-82172 | Red Gate | 46°23′24′′ N | 122°47′29′′ W | 47 |

| WWU-6239 | Cougar Creek confluence | 46°23′36′′ N | 122°47′38′′ W | 48 |

| WWU-82174 | Tooley Road Bridge | 46°24′46′′ N | 122°47′38′′ W | 40 |

| WWU-82176 | Upstream from Jackson Bridge | 46°25′23′′ N | 120°48′54′′ W | 40 |

| WWU-82175 | Jackson Highway Bridge | 46°25′23′′ N | 122°50′24′′ W | 33 |

| Wilkes Fm Washington State, USA | Whitemud Fm. Saskatchewan, Canada | Morisson Fm Utah, USA | Madagascar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWU-82175 | WWU-1571 | |||

| 3.63 | 3.07 | 2.92 | 2.99 | 2.92 |

| 3.66 | 2.68 | 2.90 | 3.15 | 2.81 |

| 3.04 | 2.95 | 3.12 | 3.51 | |

| 2.85 | 2.85 | 3.13 | 2.86 | |

| 2.92 | 2.78 | 2.86 | 3.36 | |

| 2.53 | 2.93 | 3.11 | 2.80 | |

| 2.87 | 2.93 | 2.86 | 3.52 | |

| Mean value | ||||

| 4.31 | 2.85 | 2.89 | 3.05 | 3.11 |

| Reference data | ||||

| Siderite | 3.96 | |||

| Hematite | Up to 5.26 | |||

| Goethite | 3.3–4.3 | |||

| Ferrihydrite | 3.8 | |||

| Limonite group | 2.7–4.3 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustoe, G.E. The Controversial Origin of Ferruginous “Coprolites”. Minerals 2025, 15, 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121271

Mustoe GE. The Controversial Origin of Ferruginous “Coprolites”. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121271

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustoe, George E. 2025. "The Controversial Origin of Ferruginous “Coprolites”" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121271

APA StyleMustoe, G. E. (2025). The Controversial Origin of Ferruginous “Coprolites”. Minerals, 15(12), 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121271