Abstract

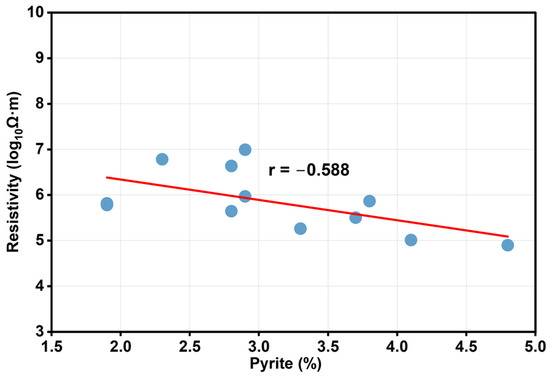

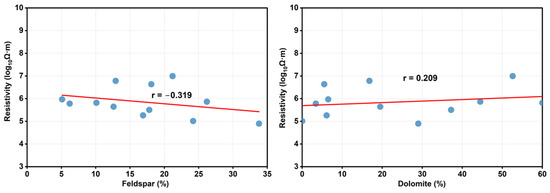

Ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag, characterized by difficult-to-drill formations, exhibits high resistivity. This study uses XRD and petrophysical testing on 12 dry core samples (depths 4600–5000 m) to characterize mineral composition and evaluate resistivity-influencing factors. Mineralogical analysis reveals that brittle minerals, dominated by quartz and feldspar (>50%), constitute the primary components of the ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag, with quartz, feldspar, and carbonates collectively accounting for ~80%. Clay (~6%) and pyrite (<5%) contents are notably low, resulting in elevated resistivities of 105–107 Ω·m. Resistivity correlates negatively with pyrite (r = −0.588) and feldspar (r = −0.319) but positively with dolomite (r = 0.209), quartz (r = 0.017), and porosity (r = 0.749). At elevated temperatures (100 °C), resistivity declines owing to enhanced ionic conduction. These findings clarify high-resistivity mechanisms, supporting resistivity-based drilling parameter optimization.

1. Introduction

Shale oil, as a crucial unconventional hydrocarbon resource, has emerged as a research hotspot in the global energy sector in recent years. Compared to conventional reservoirs, shale oil exhibits widespread resource distribution, ultra-low permeability, and complex accumulation mechanisms [1]. China’s continental shale oil resources are abundant and widely distributed, with geological resources exceeding 300 billion tons [2,3,4]. As exploration and development targets shift from shallow to ultra-deep layers, proven reserves of ultra-deep shale oil continue to increase [5]. Currently, the deepest target formation for continental shale oil in China is the Permian Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag of the Junggar Basin, with burial depths ranging from 4500 to 6100 m and potential resources of approximately 530 million tons [6,7,8]. The ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag exhibits substantial potential for large-scale hydrocarbon production. Efficient exploitation of such reservoirs advances theoretical models for unconventional resource development and offers practical guidance for global ultra-deep shale oil exploration.

The ultra-deep continental shale in the Mahu Sag has undergone multiple tectonic movements and diagenetic processes, exhibiting characteristics of high temperature (>110 °C), high geostress (>80 MPa), high rock strength (~500 MPa), and strong heterogeneity (“three highs and one strong”) [9]. High geostress and rock strength substantially elevate the energy demands for rock resistance during cutting and crushing. Meanwhile, pronounced heterogeneity induces uneven stress distribution and hinders local fracturing. These factors collectively intensify bit wear, diminish energy transfer efficiency, and heighten rock-breaking difficulty. Conventional drilling speed-up measures are ineffective, and low rock-breaking efficiency has become a core bottleneck constraining the economic development of ultra-deep continental shale oil in the Mahu Sag. Traditional empirical-based drilling parameter adjustment models can no longer meet current speed-up demands.

Resistivity, as a key parameter in logging-while-drilling, can reflect rock composition, pore structure, and mechanical properties in real time, theoretically correlating with rock-breaking efficiency [10,11]. Drilling practices in the ultra-deep continental shale of the Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag also indicate a significant correlation between resistivity and mechanical drilling rate. Therefore, a systematic investigation of resistivity response mechanisms in this region elucidates the linkage between rock-breaking efficiency and resistivity. This enables the development of resistivity logging-based models for predicting rock-breaking efficiency and dynamically optimizing drilling parameters. This is of significant importance for overcoming the over-reliance on field experience in current drilling parameter adjustments and advancing the development of ultra-deep continental shale oil.

Current research on the correlation mechanisms between shale rock-breaking efficiency and resistivity logging responses is still in its nascent stage. Existing studies indicate that rock-breaking efficiency is primarily related to rock mechanical properties and drilling engineering parameters [12,13,14], while shale resistivity is synergistically controlled by factors such as pyrite and clay mineral content, organic matter graphitization degree, porosity, and fluid saturation [15,16,17,18,19]. Cao et al. [20,21] employed multiple experimental methods, including scanning electron microscopy, TOC testing, X-ray diffraction whole-rock analysis, porosity, and resistivity testing, and found that shale resistivity is mainly influenced by pyrite and clay mineral content. Dong et al. [22] used petrophysical experiments and three-dimensional digital core simulations to demonstrate that shale resistivity is jointly affected by framework structure, pore fluids, and mineral composition, with clay minerals like montmorillonite and illite reducing resistivity through cation exchange. Li et al. [23] further observed that the layered structure and high surface area of clay minerals promote micropore development in shale reservoirs, thereby increasing bound water saturation and reducing resistivity. Additionally, Clegg et al. [24] conducted electromagnetic three-dimensional inversion on ultra-deep shale and found that increased overburden pressure reduces rock porosity and fluid volume, thereby increasing resistivity. Shi et al. [25] performed petrophysical experiments on shales with varying properties under different saturation states, analyzing the influence of parameters such as porosity, permeability, and saturation on shale resistivity, revealing that it is comprehensively affected by rock physicochemical parameters. Zhou et al. [26,27] established a relationship between organic matter graphitization degree and resistivity using Raman spectroscopy and petrophysical experiments, discovering that higher graphitization significantly reduces shale resistivity. Nie et al. [28] analyzed two-dimensional SEM-EDS images of shale reservoirs to characterize mineral distributions. They applied Markov chain-Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to generate three-dimensional digital cores, demonstrating that shale resistivity is governed by clay mineral content, pyrite content, pore types, and organic matter graphitization degree. Cheng et al. [29] integrated mineral composition analysis, electron microscopy, total organic carbon (TOC) content, water saturation measurements, and logging data. Using random modeling techniques, they constructed three-dimensional numerical core models and simulated shale resistivity responses through finite element analysis. The results indicate that increases in clay mineral content, pyrite content, water saturation, and organic matter graphitization degree all lead to decreased resistivity in shale reservoirs. However, existing research predominantly focuses on marine shale reservoirs and shallow-to-medium burial depths, with few reports on the genesis of high resistivity in ultra-deep shale from the Mahu Sag. The ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag is continental, featuring complex geological conditions, strong rock heterogeneity, numerous resistivity influencing factors, and intricate coupling relationships among them. Therefore, there is an urgent need to refine the resistivity response mechanisms in ultra-deep continental shale, reveal the genesis of high resistivity, and provide a theoretical basis for further exploring the association mechanisms between ultra-deep continental shale rock-breaking efficiency and resistivity.

This study systematically characterizes the mineral composition of ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and petrophysical methods. It further investigates the effects of mineral composition, porosity, water saturation, temperature, and cementation on shale resistivity. These findings enhance the comprehension of electrical responses in ultra-deep shale, elucidate the interrelationships among resistivity parameters, rock mechanical properties, and rock-breaking efficiency, and facilitate the development of resistivity-based real-time models for predicting rock-breaking efficiency. This is expected to provide scientific support for addressing challenges such as high costs, low accuracy, and high difficulty in predicting rock-breaking efficiency in ultra-deep continental shale, as well as the lack of theoretical basis for drilling parameter adjustments.

2. Materials and Methods

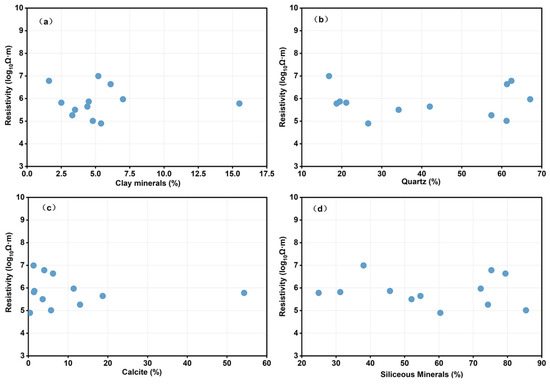

The rock samples used in this study are authentic downhole specimens from the Permian Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag of the Junggar Basin (Figure 1), representing typical ultra-deep continental shale in China. The mineral composition is dominated by felsic, dolomitic, and mixed minerals [30]. The experimental samples were cored at depths of approximately 4600–5000 m, with lithology characterized as mixed shale and porosity ranging from 2.3% to 6.6%.

Figure 1.

Location map of the Mahu Sag in the Junggar Basin, northwest China.

2.1. Sample Preparation

Cylindrical core plugs with a diameter of 25 mm and length of 50 mm were obtained from full-diameter cores using wire cutting. To minimize end-face effects on the plugs and ensure the parallelism of the upper and lower surfaces meets experimental requirements, the core plugs were mechanically polished using an MC004 grinder-polisher (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). After polishing, the surface height variation ranged from 500 to 1000 nm, with parallelism of the upper and lower surfaces not exceeding 0.01 mm and vertical deviation not exceeding 0.05° (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Selected high-resistivity rock samples based on logging resistivity.

2.2. Resistivity Testing

Empirical evidence in shale oil exploration indicates that resistivity thresholds are typically set at 100 Ω·m for high resistivity and 1000 Ω·m for ultra-high resistivity. Therefore, this study focuses on the ultra-high resistivity phenomenon in shale exceeding 1000 Ω·m. From a total of 29 rock sample groups, 12 cylindrical core plug samples with resistivity exceeding 1000 Ω·m were selected. All samples were dried in a muffle furnace at 100 °C for 24 h prior to testing to eliminate interference from pore water and free water. Resistivity measurements were conducted using an ST2643 ultra-high resistance tester (Beijing Oriental Jicheng Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) (measurement range: 1–10,000 Ω·m), strictly adhering to the Chinese national standard GB/T 1410-2006/IEC 60093:1980 [31] “Methods of Test for Volume Resistivity and Surface Resistivity of Solid Insulating Materials.” The testing method employed the two-electrode approach, applying a direct current voltage to the upper and lower end faces of the sample and recording the current to calculate volume resistivity. To enhance measurement accuracy, the sample end faces were coated with metal electrodes prior to testing to minimize contact resistance effects. Other operations, such as drying and dimensional measurements, followed conventional laboratory procedures using standard equipment and are not detailed here.

2.3. XRD Analysis

The remaining core samples, after wire cutting, were crushed and ground into fine powders for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The powdered samples were evenly spread on a flat sample holder to minimize preferred orientation effects. Diffraction patterns were collected using a Bruker AXS D8 Advance A25 diffractometer (Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Scans were performed over a 2θ range of 2°–70°, with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning rate of 2° min−1.

Quantitative phase analysis was performed using JADE 9.0 software (Materials Data Inc., Ashburn, VA, USA) integrated with the ICDD PDF-4+ 2019 database. The Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) method, also known as the K-value method, was employed, with α-Al2O3 (corundum) serving as the internal reference material. RIR (K) values for all identified phases were obtained from the PDF-4+ 2019 database. The weight fraction (WX) of each phase was determined according to:

IX is the integrated intensity of the primary diffraction peak of phase X, KX is its RIR value relative to corundum, and the denominator represents the sum over all detected crystalline phases. A fixed amount of corundum was added to each sample as an internal standard to correct for matrix effects, with background subtraction and peak fitting conducted in JADE 9.0.

Relative standard uncertainties in the calculated phase fractions were derived from triplicate analyses, accounting for peak overlap, background noise, and instrumental variability. These uncertainties ranged from 3% to 10%, corresponding to 3%–5% for major phases (>20 wt%), 5%–8% for minor phases (5–20 wt%), and 8%–10% for trace phases (<5 wt%). These results are consistent with established benchmarks for RIR-based quantitative XRD analysis, where the absolute uncertainty is typically less than ±50 X−0.5 wt% at the 95% confidence level, with X denoting the weight fraction.

3. Results

3.1. Mineral Characterization

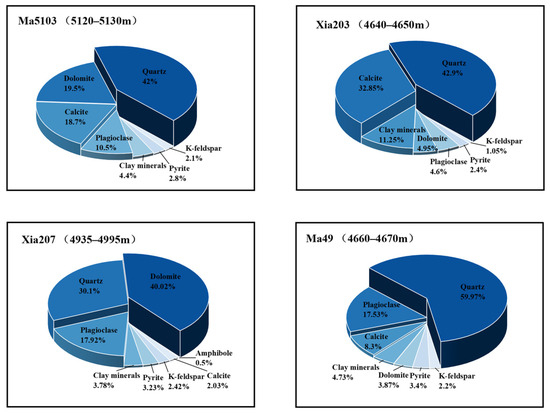

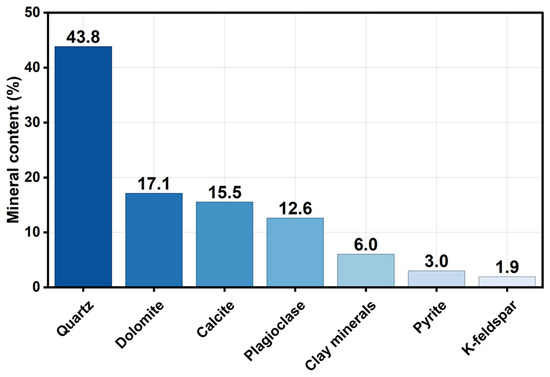

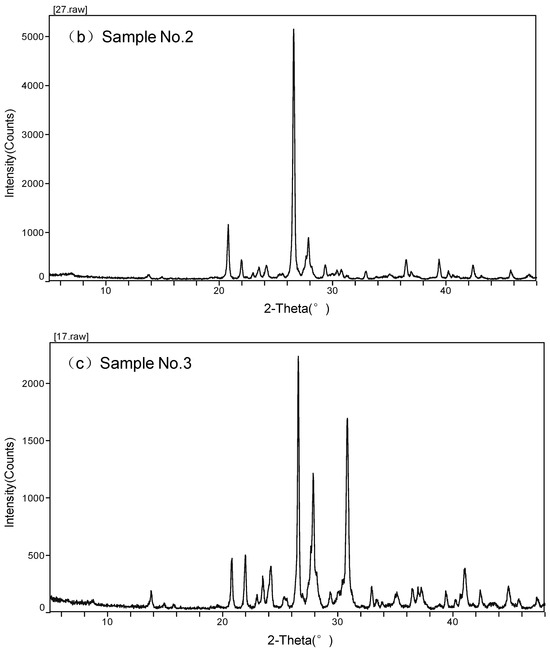

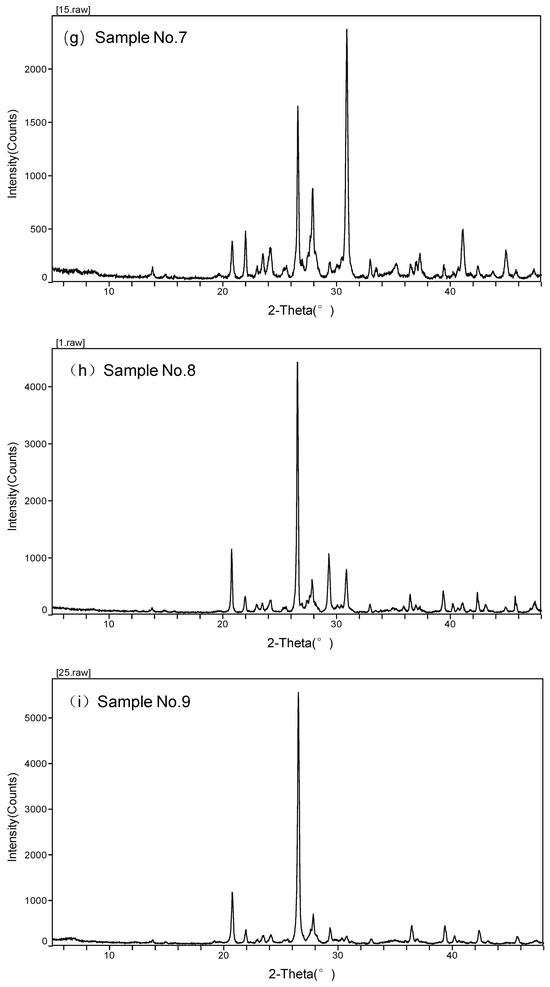

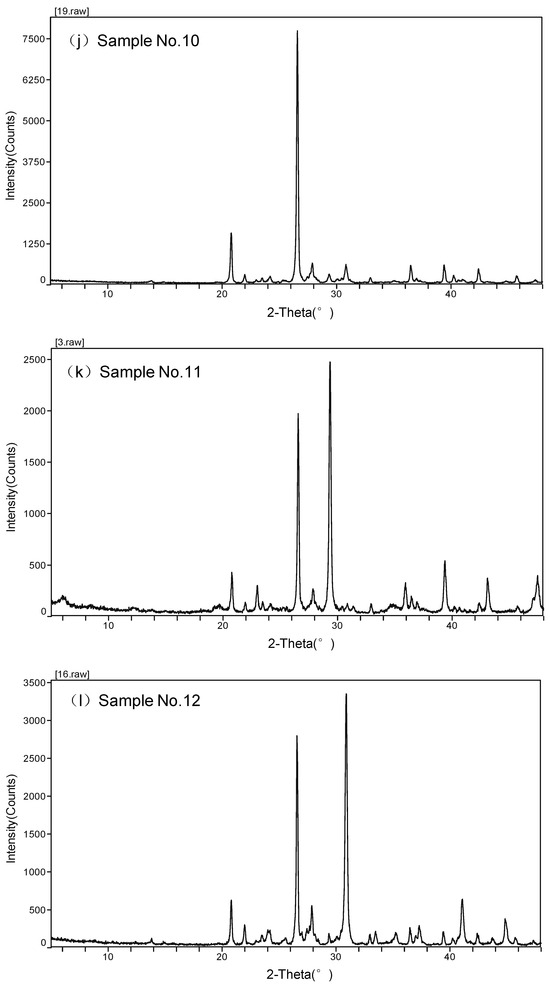

Based on the X-ray diffraction (XRD) whole-rock quantitative analysis of 12 samples (Figure 3 and Figure 4), the mineral composition of ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag exhibits the following characteristics. (1) Dominance of brittle minerals: Quartz and feldspar are predominant, with total contents typically ranging from 50% to 70%; quartz varies significantly between wells (Ma49 ≈ 60%; Xia207 ≈ 30%), while feldspar ranges mostly from 10% to 30% (average ≈ 20%), collectively imparting high brittleness to the reservoir. (2) Carbonates display a bimodal distribution, with dolomite and calcite occurring ubiquitously. Select samples exhibit pronounced enrichment (>30%; e.g., dolomite ≈ 40% in Xia207, calcite ≈ 32.9% in Xia203), whereas others contain <15% carbonates. This variability reflects alternating terrigenous clastic inputs and alkaline lacustrine chemical precipitation during sedimentary-diagenetic evolution. (3) Low clay content (sample range ≈ 3–15%, group average ≈ 6%), indicating transformation or compaction of primary argillaceous components due to deep burial diagenesis. (4) Accessory minerals dominated by pyrite (generally 2–4%, highest in Ma49 ≈ 3.4%), with local detection of hornblende (Ma5103 ≈ 0.5%), suggesting localized anoxic–reducing depositional environments and possible volcanic ash input. In summary, quartz, feldspar, and carbonates (collectively averaging ≈ 80%) dominate the mineral composition of ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag. This assemblage confers high brittleness and yields a pore system dominated by microfractures and intergranular pores. The XRD analytical patterns of the samples are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 3.

XRD mineral composition analysis for various well areas in the Mahu Sag.

Figure 4.

Average XRD mineral composition analysis in the Mahu Sag.

3.2. Analysis of Resistivity

3.2.1. Mineral Composition

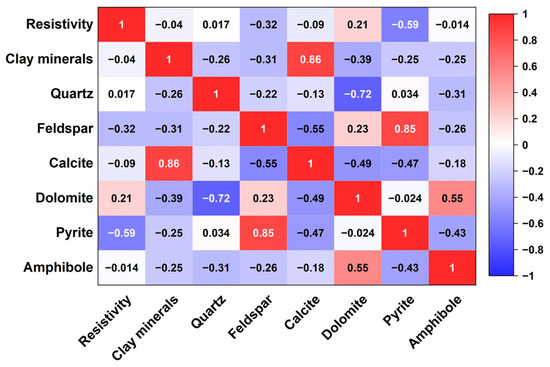

Mineral composition, as the fundamental building block of the shale framework, directly determines charge carrier migration paths, thereby controlling apparent resistivity. Intrinsic resistivities of minerals differ markedly. Insulating minerals, such as quartz and dolomite, elevate rock resistivity due to their high intrinsic values, which occupy pore spaces and form dense frameworks. In contrast, conductive minerals like pyrite and certain feldspars reduce overall resistivity by creating low-resistance pathways through semiconductor behavior or ionic migration. Synergistic interactions among minerals further complicate electrical responses and may be influenced by thermal evolution, recrystallization, and microstructural heterogeneity, rendering traditional effective medium models (e.g., Bruggeman equation) not directly applicable. To systematically evaluate the comprehensive regulation of mineral composition on resistivity, this study utilized X-ray diffraction quantitative analysis results, combined with logarithmically transformed experimental resistivity measurements, to generate a correlation heatmap for multivariate visualization analysis.

The results (Figure 5) show that pyrite exhibits a significant negative correlation with resistivity (r = −0.59), indicating its strong inhibitory effect as a conductive mineral. The presence of pyrite also reflects deposition under an anoxic environment, which favored the preservation of organic matter, potentially influencing pore-filling and conductivity characteristics. Feldspar displays a moderate negative correlation (r = −0.32), suggesting its potential to introduce conductive paths via ion migration. Clay minerals and calcite show very weak correlations with resistivity (r = −0.04 and −0.09), indicating limited contributions to conductivity in dry samples. In contrast, dolomite and quartz exhibit weak positive correlations (r = 0.21 and 0.017), reflecting the potential contributions of their insulating intrinsic properties. Hornblende, due to its extremely low content (average 0.25%), has a near-zero correlation (r = −0.014). Furthermore, cross-correlations among minerals reveal synergistic and competitive relationships, such as the negative correlation between quartz and feldspar (r = −0.22), indicating mutually exclusive distribution of aluminosilicate minerals, and between dolomite and calcite (r = −0.49), reflecting competitive precipitation of carbonate minerals during diagenesis. Overall, the high resistivity of ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag is not dominated by a single mineral but results from the mutual balance between conductive and insulating minerals, shaped by both mineral composition and depositional environment.

Figure 5.

Pearson correlation heatmap of resistivity and mineral composition.

3.2.2. Porosity

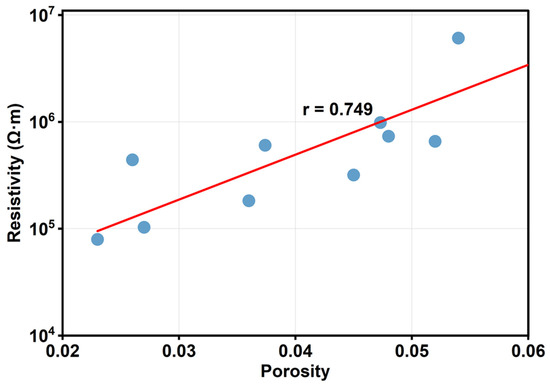

In the study of ultra-deep shale reservoirs, resistivity serves as a core geophysical parameter, commonly used to characterize reservoir fluid saturation and pore structure. Traditional models (e.g., the Archie equation) are primarily applicable to sandstone reservoirs under saturated fluid conditions, where resistivity typically exhibits a negative correlation with porosity, as conductive fluids like formation water filling the pores reduce overall resistivity. This study focuses on ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag, employing dried core samples for experiments to exclude fluid influences and concentrate on the intrinsic relationship between rock framework resistivity and porosity. This approach aids in revealing the contributions of mineral composition and microstructure to the genesis of high resistivity, potentially involving the distribution of insulating minerals (e.g., quartz or calcite) or thermal evolution effects.

Table 1 lists the porosity and resistivity measurement data for ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag under dry rock sample conditions. Porosity ranges from 0.023 to 0.066, with an average of 0.0437; resistivity ranges from 7.9 × 104 to 9.9 × 106 Ω·m, with an average of 2.0 × 106 Ω·m, reflecting significant high-resistivity characteristics consistent with the low conductivity of the dry rock framework.

Table 1.

Resistivity and porosity test data for samples.

Pearson correlation analysis indicates a significant positive correlation between porosity and resistivity, with a correlation coefficient r = 0.749 (Figure 9). As porosity increases, resistivity tends to rise. Linear regression model fitting results show that the 95% confidence interval confirms reliable model parameters, with residual diagnostics revealing no significant heteroscedasticity or nonlinear deviations. In dried rock samples, conductive fluids (e.g., formation water) in the pore space are completely removed, and pores are primarily filled with high-resistivity air [27]. At this point, the rock’s conductivity almost entirely depends on the ionic and electronic conductivity of the solid framework minerals themselves, as well as the limited contact points between mineral particles. Elevated temperatures induce thermal expansion of the rock framework, thereby enlarging pore spaces and increasing porosity. This enhances the volumetric fraction of highly insulating air within the rock, while proportionally reducing the conductive solid mineral matrix capable of current transmission. The presence of insulating pores directly replaces potential conductive paths while also altering the flow of current through the solid framework. Elevated porosity reduces inter-particle contact points, thereby increasing contact resistance. This compels current to follow longer, more tortuous paths through the residual framework, diminishing the effective cross-sectional area for conduction and prolonging pathway lengths, which ultimately elevates apparent resistivity [39].

Figure 9.

Correlation between resistivity and porosity.

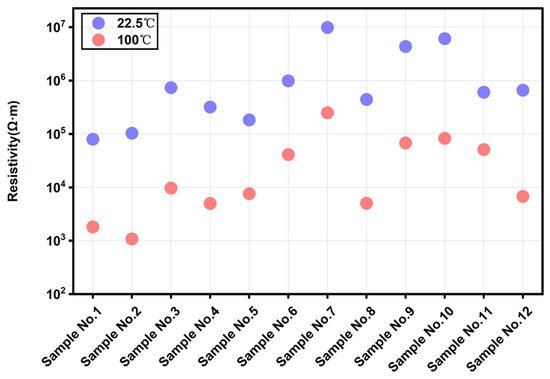

3.2.3. Temperature

The resistivity measurements of twelve ultra-deep shale samples from the Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, China, were conducted at two distinct temperatures: 22.5 °C (ambient conditions) and 100 °C (simulating elevated reservoir thermal regimes). The results, presented in Figure 10, reveal a consistent inverse relationship between temperature and electrical resistivity across all samples. At 22.5 °C, the resistivity values ranged from 7.94 × 104 Ω·m (Sample No. 1) to 9.87 × 106 Ω·m (Sample No. 7), with a mean value of 2.03 × 106. In contrast, at 100 °C, the resistivity decreased markedly, ranging from 1.08 × 103 Ω·m (Sample No. 2) to 2.48 × 105 Ω·m (Sample No. 7), yielding a mean of 4.40 × 104. This temperature-induced reduction is visually evident in the semi-logarithmic scatter plot (Figure 1), where blue points (22.5 °C) cluster at higher resistivity magnitudes compared to red points (100 °C), indicating a systematic downward shift.

Figure 10.

Resistivity at room temperature (22.5 °C) and high temperature (100 °C).

Statistical analysis further quantifies this correlation. The Pearson correlation coefficient between resistivity at the two temperatures is 0.9408 on a linear scale and 0.9176 on a logarithmic scale, underscoring a strong positive association despite the overall decline in values with increasing temperature. The average resistivity ratio (22.5 °C/100 °C) was calculated as 58.49, highlighting an approximately 58-fold decrease on average, though variability suggests influence from sample-specific mineralogical or microstructural factors.

To model the thermal dependence, an Arrhenius-type relationship was approximated for the resistivity behavior, assuming ionic conduction dominance in these shales: ρ = ρ0 eEa/kT, where ρ is resistivity, Ea is the apparent activation energy, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is absolute temperature. Using the two-point data, the computed Ea values ranged from 0.3033 to 0.5615 eV, with a mean of 0.4790. These energies align with thermally activated conduction processes typical in clay-rich sedimentary rocks [40].

The observed temperature-dependent resistivity decline in the Mahu Sag ultra-deep shales can be attributed to enhanced ionic mobility and solid-state conductivity at elevated temperatures, which are prevalent mechanisms in argillaceous formations enriched with clay minerals such as illite and smectite. In these dry samples, the high resistivity at ambient conditions likely stems from the insulating effects of organic matter, pyrite dissemination, and low-porosity matrices, characteristic of the alkaline lacustrine depositional environment in the Fengcheng Formation [41]. As temperature rises to 100 °C, thermal agitation facilitates ion dissociation in bound water within clay interlayers and mineral defects, reducing overall resistivity. This is particularly pronounced in ultra-deep shales where maturation processes, including graphitization of organic matter, may further modulate conductivity.

The strong correlation coefficients indicate that mineralogical composition exerts a controlling influence, with outliers (e.g., Sample No. 7 exhibiting the highest resistivity and ratio) potentially reflecting higher organic content or fracture sealing, which impedes conduction pathways at lower temperatures but becomes less effective under thermal stress. The calculated activation energies (mean ~0.48 eV) suggest a conduction regime dominated by surface-bound water and electrolyte migration rather than electronic semiconduction, consistent with observations in analogous shale systems where salinity and clay content amplify temperature sensitivity [33]. This thermal sensitivity has implications for the genesis of high resistivity in the Mahu Sag: it underscores that anomalous high-resistivity zones may arise from low thermal maturity or diagenetic alterations that restrict ion mobility, rather than solely from hydrocarbon saturation.

Variability in the resistivity ratios (standard deviation ~28) highlights heterogeneity, possibly linked to differential pyrite oxidation or clay transformation during burial, which could be exacerbated in ultra-deep settings exceeding 5000 m depth. Comparative studies in other basins, such as the Bakken Formation, report similar thresholds where resistivity drops sharply above ~74 °C due to kerogen maturation, reinforcing that temperature acts as a key modulator of electrical properties in organic-rich shales [42].

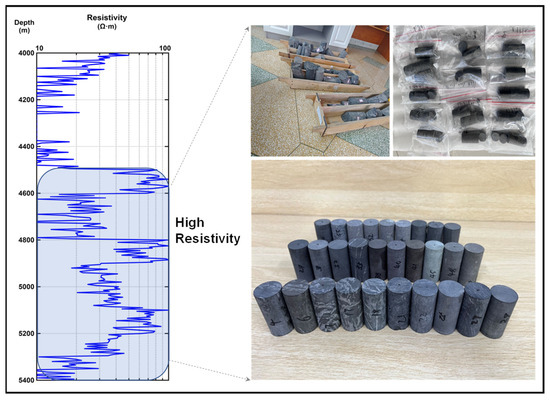

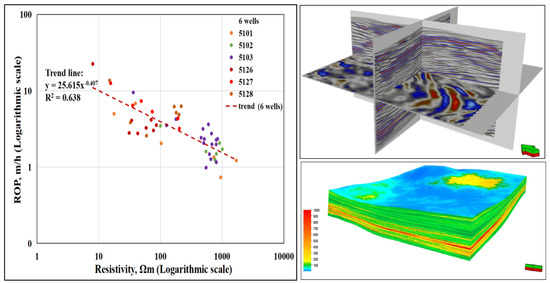

3.3. Engineering Practice Analysis

Field logging-while-drilling (LWD) data from pilot horizontal wells in the Mahu Sag provide critical insights into resistivity patterns within the Permian Fengcheng Formation, highlighting the interplay between electrical properties and drilling performance. In wells MaHW5102 and MaHW5103, resistivity logs exhibit a progressive escalation with depth. Upon penetrating the C8 layer, values rise from approximately 100 to 400 Ω·m, reflecting a transition into more compact, low-porosity zones influenced by diagenetic compaction and mineral cementation. This increase intensifies in the C9-10 layers, peaking at 400–800 Ω·m and occasionally exceeding 4000 Ω·m in ultra-high resistivity intervals (Figure 11). These anomalies correspond to regions dominated by insulating minerals such as quartz and dolomite, as identified in prior XRD analyses, where reduced conductive phases like pyrite minimize charge pathways. The elevated resistivity signals zones of heightened rock resistance, characterized by strong heterogeneity and high geostress (>80 MPa), which exacerbate bit wear and fracture propagation challenges during drilling. Such patterns align with the formation’s alkaline lacustrine origin, where burial depths exceeding 4500 m promote densification, further amplifying electrical insulation and correlating with reduced permeability.

Figure 11.

Resistivity logs of horizontal wells in the Mahu Sag pilot area.

To quantify the impact on drilling efficiency, cross-plot analysis was conducted between average rate of penetration (ROP) during trip drilling in the third spud section and average resistivity values across multiple wells. The data reveal a pronounced negative correlation, empirically modeled by the linear equation:

with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.78 (Figure 12, left). This relationship indicates that as resistivity increases—driven by factors like low porosity and insulating mineral dominance—ROP declines exponentially on a logarithmic scale, confirming higher resistivity’s association with harder, more brittle formations that demand greater mechanical energy for breakage. For instance, in intervals exceeding 1000 Ω·m, ROP often drops below 5 m/h, underscoring the bottleneck in ultra-deep shale operations where conventional parameters fail to adapt dynamically. This correlation integrates seamlessly with the resistivity elucidated earlier, where positive temperature coefficients and porosity effects further stiffen the rock matrix under in situ conditions.

y = 25.615 x−0.407

Figure 12.

Cross-plot of average ROP versus average resistivity in the Mahu Sag (logarithmic scale) and 3D resistivity models of the Fengcheng Formation.

The right panel of Figure 12 presents 3D resistivity models constructed via geostatistical interpolation of LWD data, visualizing spatial variations across the Fengcheng layers. The cross-sectional view depicts heterogeneous distributions, with high-resistivity cores (red hues > 1000 Ω·m) embedded in compact, low-conductivity zones, indicative of localized dolomite cementation and quartz enrichment. The layered model illustrates lateral and vertical gradients, revealing fault-influenced discontinuities that contribute to uneven stress fields and variable drillability. These models facilitate advanced reservoir characterization, enabling geosteering adjustments to avoid high-resistance barriers and target sweeter spots with optimal fracture potential.

Collectively, these engineering analyses validate resistivity as a robust proxy for real-time drillability prediction in ultra-deep continental shale. By leveraging LWD resistivity for intelligent parameter optimization—such as weight-on-bit and rotary speed adjustments—drilling efficiency can be enhanced by up to 20%–30%, reducing operational costs and non-productive time. This approach not only addresses the “three highs and one strong” challenges of the Mahu Sag but also provides a scalable framework for global ultra-deep shale exploitation, bridging petrophysical insights with practical development strategies.

4. Discussion

Based on the XRD testing and petrophysical analysis results, the genesis of high resistivity in ultra-deep shale from the Mahu Sag can be summarized into the following four aspects: (1) Sedimentary environment and mineral composition. The Fengcheng Formation shale in the Mahu Sag formed in an alkaline lacustrine sedimentary environment, where terrigenous clastic and chemical deposits alternate. Under strong evaporation conditions, high-salinity lake water promoted the precipitation of carbonate minerals (e.g., dolomite) while inhibiting the massive formation of clay minerals; the provenance area provided abundant quartz and feldspar, with limited clay supply. This alkaline lacustrine sedimentary environment shaped the initial mineral composition characterized by high brittle minerals and low clay content in the shale, laying the mineral foundation for high resistivity. (2) Transformation by ultra-deep continental diagenesis. In the ultra-deep continental environment, the shale underwent intense compaction and cementation, resulting in a substantial reduction in primary pores and extremely low permeability. Meanwhile, clay minerals experienced dehydration and transformation (e.g., montmorillonite to illite) during deep burial, releasing interlayer water and reducing exchangeable cations, thereby decreasing rock conductivity. The high-temperature and high-pressure environment also prompted partial organic matter pyrolysis to generate bitumen or graphite, filling pores and expelling pore water, further reducing conductivity. Therefore, ultra-deep continental diagenesis renders the shale more compact, further elevating resistivity. (3) Pore fluid characteristics: The ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag typically has porosity less than 5%, dominated by nanoscale micropores and intercrystalline pores, with essentially no free water. The primary pore fillings are shale oil and minor bound water. Since bound water is adsorbed on mineral surfaces, ion migration is severely restricted, rendering its contribution to conductivity negligible. Thus, the shale’s conductivity is almost entirely determined by the solid framework. In this state, the shale naturally exhibits extremely high resistivity. In contrast, conventional shallow shale often contains certain amounts of free water or brine, leading to lower resistivity. (4) Temperature-pressure conditions: The high-temperature conditions in ultra-deep layers have a dual impact on resistivity: on one hand, high temperatures enhance ionic mobility in mineral lattices, increasing charge carrier activation and reducing resistivity; on the other hand, high temperatures may induce mineral phase transitions or decomposition, generating new conductive phases. However, samples from the study area indicate that at 100 °C, major mineral components remain stable without evident decomposition, with high temperature primarily facilitating the intrinsic conductivity characteristics of minerals in dry conditions. Under high-pressure conditions, rock pores decrease and fractures reduce, to a certain extent decreasing rock resistivity.

In summary, resistivity in Mahu Sag ultra-deep shale results from the coupled effects of sedimentary, diagenetic, mineralogical, fluid, and temperature-pressure controls. Mineral composition serves as the intrinsic controlling factor, while temperature and pressure further reinforce high-resistivity characteristics. Integrating resistivity analysis with logging data and mineralogical characterization enables enhanced prediction of mechanical properties, offering both scientific and practical value for drilling operations in ultra-deep continental shale.

5. Conclusions

Through comprehensive research on the mineral composition and resistivity of ultra-deep shale samples from the Mahu Sag, the following main conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- Mineral composition characteristics: The ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag is dominated by brittle minerals such as quartz and feldspar, along with carbonate minerals, with extremely low contents of clay and conductive minerals. The total content of quartz and feldspar is typically greater than 50%, carbonate minerals exhibit a wide distribution range, clay minerals average 5%, and minerals like pyrite are less than 5%. This mineral assemblage imparts high brittleness, high hardness, and high resistivity to the ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag.

- (2)

- High dry rock sample resistivity: All dry rock sample resistivities fall within the range of 105 to 107 Ω·m, far exceeding the typical logging resistivity values of 102 to 104 Ω·m for conventional shale. Considering that logging resistivity represents the rock resistivity in the near-wellbore zone under in situ formation conditions, influenced by pore water. Some samples exhibit dry rock resistivities as high as 107 Ω·m; this anomalously high resistivity reflects the scarcity of conductive pathways in dry samples, with the high resistivity phenomenon primarily influenced by high-resistivity minerals.

- (3)

- High-temperature (100 °C) resistivity tests indicate that the resistivity of Mahu shale significantly decreases with rising temperature, exhibiting a negative correlation with temperature. This contrasts with the behavior of conventional water-bearing rocks, suggesting that the conduction mechanism in dry samples is dominated by intrinsic mineral conduction. High temperatures enhance lattice vibrations, increase charge carrier mobility, and lead to decreased resistivity. This finding holds significant implications for understanding rock electrical properties in ultra-deep high-temperature environments.

- (4)

- Mechanisms of high resistivity genesis: The high resistivity of ultra-deep shale in the Mahu Sag results from the combined effects of multiple factors, including sedimentation, diagenesis, minerals, fluids, and temperature-pressure conditions. (1) Regarding mineral composition, high quartz, feldspar, and carbonate contents form a high-resistivity framework, while low clay and pyrite levels minimize conductive pathways. Collectively, these mineral interactions drive the elevated resistivity of Mahu Sag shale. (2) Ultra-deep burial results in extremely low porosity and minimal water content, rendering the contribution of pore fluids to conductivity negligible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; methodology, D.Z.; validation, P.Z.; resources, S.T.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.Z.; supervision, Y.T.; funding acquisition, P.Z. and Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 52504047); Youth Science Fund Project of the Department of Science and Technology of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2025D01B194); the Sub-project of the Key R&D Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (No. 2024B01017-3); and the Introduction Program for Young Doctors (“Tianchi Talents”) in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yangfei Yu was employed by the company Xinjiang Oilfield Company, PetroChina. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

XRD patterns of 12 ultra-deep shale core samples (depths 4600–5000 m) from the Fengcheng Formation, Mahu Sag, China.

References

- Guo, X.S.; Shen, B.J.; Li, M.W.; Liu, H.M.; Li, Z.M.; Zhang, S.C.; Yang, Y.; Guo, J.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, P.; et al. Research progress and key research directions on shale oil in continental faulted lacustrine basins. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Zhu, R.K.; Zhang, J.Y.; Yang, J.R. Types of continental shale oil in China, exploration and development status and development trends. China Pet. Explor. 2023, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.Z.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, Y.F. Unconventional hydrocarbon resources in China and the prospect of exploration and development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Q.; Zhang, J.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Tang, Y.; Yu, W.J. Progress and prospects of unconventional oil and gas exploration and development in China. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.X.; Wang, S.Y.; Li, M.P.; Ouyang, J.L.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.Y.; Zeng, F.D.; Fan, J.J.; Jia, P. Progress and implications of deep and ultra-deep oil and gas exploration in China. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.H.; Li, W.L. Unconventional oil and gas in China become an important support for increasing reserves and production. China Pet. Enterp. 2024, 3, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.G.; Yu, C.L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Q.; Jia, L.H.; Sun, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.X.; Fan, F. Current status and prospects of experimental technology for continental shale oil development. Oil Gas Geol. Recovery Effic. 2024, 31, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.S.; Li, M.W.; Zhao, M.Y. Development and utilization of shale oil and its role in energy. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 38, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.Z.; Yong, R.; Hu, D.F.; She, C.Y.; Fu, Y.Q.; Wu, J.F.; Jiang, T.X.; Ren, L.; Zhou, B.; Lin, R. Deep and ultra-deep shale gas fracturing in China: Problems, challenges and development directions. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, J.F.; Guo, Y.J. Progress and development trends of logging while drilling technology. Well Log. Technol. 2006, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.Z.; Sun, J.M. Summary of new progress in logging technology. Prog. Geophys. 2005, 3, 786–795. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Chen, P. A review of the evaluation, control, and application technologies for drill string vibrations and shocks in oil and gas well. Shock Vib. 2016, 2016, 7418635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Li, G.S.; Shi, H.Z.; Huang, Z.W.; Wu, Z.B. Progress and application of new methods for efficient rock breaking. China Pet. Mach. 2012, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.S.; Liu, J.P.; Shi, K.; Pan, Y.C.; Huang, X.; Liu, X.W.; Wei, L. Influence of rock brittleness indices on hob rock-breaking efficiency. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2016, 35, 498–510. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Study on the anisotropy of complex resistivity in eastern Guizhou shale and its relationship with shale gas reservoir parameters. Chin. J. Geophys. 2021, 64, 3344–3357. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.M.; Xiong, Z.; Luo, H.; Zhang, H.P.; Zhu, J.J. Analysis of low-resistivity genesis and logging evaluation of shale gas reservoirs in the Lower Paleozoic of the Yangtze region. J. China Univ. Pet. 2018, 42, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.Q.; Feng, R.; Zhou, J.G.; Qian, S.Q.; Gao, J.T. Discussion on the mechanism of resistivity changes during rock fracture process. Chin. J. Geophys. 2002, 45, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.S. Characteristics and genesis of low resistivity in marine shale in southeastern Sichuan. Oil Gas Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.Q.; Ding, A.X.; Cai, X.; He, G.S. Analysis of abnormal resistivity genesis in marine shale in the Middle-Upper Yangtze. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2016, 23, 578–582. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G.Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, K.; He, X.L. Study on the differences in electrical characteristics based on shale brittleness: Taking shale from Wujiaping Formation in eastern Sichuan as an example. Geophys. Prospect. Pet. 2024, 63, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Sun, J.; Zeng, X.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J.; Yan, W.; Yan, W. Analysis of the influencing factors on electrical properties and evaluation of gas saturation in marine shales: A case study of the Wufeng-Longmaxi formation in Sichuan Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 824352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.M.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, D.L.; Zhu, J.; Golsanami, N.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Insights into the multiscale conductivity mechanism of marine shales from Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in the southern Sichuan Basin of China. J. Energy Eng. 2023, 149, 04023008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, C. An improved method for improving the calculation accuracy of marine low-resistance shale reservoir parameters. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1001287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, N.; Sinha, S.; Rodriguez, K.R.; Walmsely, A.; Sviland-Østre, S.; Lien, T.; Mouatt, J.; Marchant, D.; Schwarzbach, C. Ultra-deep 3D electromagnetic inversion for anisotropy, a guide to understanding complex fluid boundaries in a turbidite reservoir. In Proceedings of the SPWLA 63rd Annual Logging Symposium, Stavanger, Norway, 11–15 June 2022; p. D031S002R005. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.J.; Zhao, J.B.; Xiao, Z.S.; Xie, W.B.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ke, S.Z.; Bai, S. Analysis of shale electrical dispersion characteristics and influencing laws based on complex resistivity experimental measurements. Prog. Geophys. 2025, 40, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Cai, J.; Mou, S.; Zhao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Sun, S.; Guo, W.; Gao, J.; Cheng, F.; Wang, H.; et al. Influence of low-temperature hydrothermal events and basement fault system on low-resistivity shale reservoirs: A case study from the Upper Ordovician to Lower Silurian in the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Minerals 2023, 13, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Sun, S.; Cheng, F. Geological controlling factors of low resistivity shale and their implications on reservoir quality: A case study in the southern Sichuan Basin, China. Energies 2022, 15, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zou, C.C.; Meng, X.H.; Jia, S.; Wang, Y. Three-dimensional digital core modeling of shale gas reservoir rocks: Taking conductivity model as an example. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2016, 27, 706–715. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Yan, J.P.; Song, D.J.; Liao, M.J.; Guo, W.; Ding, M.H.; Luo, G.D.; Liu, Y.M. Low resistivity response characteristics and main controlling factors of shale gas reservoirs in the Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Silurian Longmaxi Formation in Changning area, southern Sichuan. Lithol. Reserv. 2024, 36, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, R.K.; Dong, L.; Fu, J.H.; Liu, H.M.; Yun, L.; Liu, G.Y.; Li, M.W.; Zhao, X.Z.; et al. Classification of continental shale oil in China and its significance. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 801–819. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 1410-2006/IEC 62631-3-1:2016; Methods of Test for Volume Resistivity and Surface Resistivity of Solid Insulating Materials. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Ma, B.; Li, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, G.; Lyu, C. Pyrite characteristics in lacustrine shale and implications for organic matter enrichment and shale oil: A case study from the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, NW China. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 16519–16535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Fu, G.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, H. Controlling factors of low resistivity in deep shale and their implications on adsorbed gas content: A case study in the Luzhou area. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, S.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Genesis mechanism of low resistivity in the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation shale and its response characteristics to pore structure—Take the Z201 Well as an example. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 43995–44011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Berraud-Pache, R.; Yang, Y.; Jaber, M. Biocomposites based on bentonite and lecithin: An experimental approach supported by molecular dynamics. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 231, 106751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, D.Y.; Zhuang, G.Z.; Li, X.L. Advanced development of chemical inhibitors in water-based drilling fluids to improve shale stability: A review. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 1977–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Berraud-Pache, R.; Souprayen, C.; Jaber, M. Intercalation of lecithin into bentonite: pH dependence and intercalation mechanism. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 244, 107079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, P.; Wen, Z. Quantifying the pore characteristics and heterogeneity of the Lower Cambrian black shale in the deep-water region, South China. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Zhou, X. Key factors of marine shale conductivity in southern China—Part II: The influence of pore system and the development direction of shale gas saturation models. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Jongmans, D. Temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity of water-bearing rocks. Geophysics 1989, 54, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarenko, M.Y.; Kondrasheva, N.K.; Saltykova, S.N. Electrical resistivity of coal and oil shales. Coke Chem. 2018, 61, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; He, H.; Fu, L.Y. New insights into how temperature affects the electrical conductivity of clay-free porous rocks. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 238, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).