Abstract

Recent studies have achieved significant advances in all-in-one adverse weather image restoration, primarily driven by the development of sophisticated model architectures. In this work, we find that effectively coordinating the complex interactions and potential optimization conflicts among different restoration tasks is also a critical factor determining the overall performance of all-in-one adverse weather image restoration models. To this end, we propose an effective all-in-one adverse weather image restoration framework, named MOE-WIRNet, designed to harmonize the learning process across various degradation types and ensure well-balanced performance among different restoration tasks. To enhance training equilibrium, we integrate a multi-task collaboration optimization strategy into the framework, coordinating the convergence dynamics of distinct restoration objectives. Furthermore, we incorporate an asymmetric mixture-of-experts (MoE) architecture into the framework to effectively address the distinct degradation patterns and varying severity levels presented by different tasks. Extensive experiments demonstrate that our framework consistently outperforms current state-of-the-art models on multiple real-world adverse weather benchmark datasets.

1. Introduction

Visual perception systems are critically important under adverse weather conditions such as rain, snow, and haze, with their performance significantly impacting practical applications including autonomous driving [1,2], intelligent transportation [3,4], and outdoor surveillance [5,6]. Such weather phenomena introduce challenges like occlusion, scattering, and reduced contrast, which severely degrade image quality and consequently impair the accuracy of downstream vision tasks such as object detection and tracking [7,8]. Therefore, the development of robust all-in-one adverse weather image restoration techniques capable of effectively eliminating multiple degradation factors is essential for enhancing visual clarity and ensuring the reliability of high-level perception systems.

While deep learning-based specialized models have exhibited outstanding performance in individual tasks such as desnowing [9], deraining [10,11,12], and dehazing [13,14,15], they confront a fundamental limitation in real-world applications. A model demonstrating superior performance on one specific task may entirely fail when applied to other tasks, revealing its limited robustness in cross-task scenarios. To advance this field, general image restoration approaches [16,17] have developed foundational frameworks capable of addressing multiple subtasks. While these methods show enhanced generalization compared to task-specific restoration methods [18,19,20], they still necessitate separate training processes for distinct restoration tasks, resulting in resource consumption.

Recently numerous all-in-one adverse weather image restoration frameworks [21,22,23,24] are considered potential solutions for foundational models, as they can simultaneously handle multiple restoration tasks within a single model. However, these methods commonly adopt a mixed training paradigm that directly combines the optimization objectives of multiple tasks. We observe that due to the complex interdependencies and potential conflicts among different degradation types, the simultaneous convergence of all tasks is hindered during the joint optimization process, resulting in significant performance bottlenecks [25]. By introducing a training scheme with sequential and prompt learning strategies, MioIR [26] has enhanced all-in-one image restoration performance. Unfortunately, this method fails to resolve inter-task conflicts, becoming a critical limitation in achieving robust multi-degradation restoration. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a multi-objective optimization strategy for unified models to facilitate all-in-one adverse weather image restoration.

In practice, we note that most existing all-in-one models rely on homogeneous network designs to handle diverse restoration tasks [27,28]. However, if a model employs a uniform and rigid architecture, it inherently lacks the flexibility to address the distinct and heterogeneous reconstruction requirements across different restoration tasks [29]. For example, dehazing [30] requires broader contextual understanding, while deraining [31] demands localized processing with strong spatial awareness, necessitating adaptive processing aligned to the task requirements. Thus, this motivates us to develop an adaptive task-capacity matching framework, improving the joint optimization of various restoration capabilities under diverse and composite adverse weather conditions.

To address these issues, we propose MOE-WIRNet, an effective all-in-one adverse weather image restoration framework that integrates a multi-objective optimization strategy and leverages an asymmetric mixture-of-experts model. Different from existing all-in-one restoration frameworks that rely on mixed multi-task training, as well as prior MoE-based architectures and adaptive loss reweighting strategies, our method explicitly models task-wise optimization behaviors and their interactions during joint training. To achieve better training balance, we incorporate a multi-task collaborative training strategy into the framework to harmonize the optimization of multiple restoration tasks. In particular, we introduce two convergence-aware indicators: a relative convergence index (RCI), which characterizes short-term convergence inconsistency among tasks within individual iterations, and an absolute convergence index (ACI), which monitors long-term performance deviation and dynamically adjusts optimization targets when a task underperforms. By jointly considering these complementary convergence signals, our optimization strategy goes beyond static heuristics or gradient-based reweighting, enabling stable and fine-grained coordination across heterogeneous degradation tasks. Furthermore, we develop an asymmetric mixture-of-experts (MoE) architecture tailored to accommodate the heterogeneous reconstruction requirements associated with different image restoration tasks. The encoder employs a soft MoE module that utilizes a global weighting strategy to mitigate forward information attenuation, while the decoder adopts a hard MoE design, leveraging Top-K routing to achieve high-fidelity texture reconstruction. Experimental results demonstrate that our approach achieves favorable performance against state-of-the-art ones on the benchmark datasets.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We propose MOE-WIRNet, a unified framework for adverse weather image restoration, addressing inconsistency and conflicts among multiple restoration tasks.

- We integrate a multi-task collaborative training strategy that dynamically balances learning across heterogeneous degradation types, ensuring stable and harmonized optimization.

- We design an asymmetric mixture-of-experts architecture to address the distinct and heterogeneous reconstruction requirements across different restoration tasks.

- Experimental results on both synthetic and real-world benchmarks demonstrate that our approach performs favorable performance against state-of-the-art ones.

2. Related Work

2.1. Single-Weather Image Restoration

Single-weather image restoration refers to a class of image processing and computer vision techniques aimed at removing visual degradations caused by a single type of adverse weather condition. In real-world outdoor environments, imaging systems often suffer from weather-induced distortions such as haze, rain streaks, or snow particles, which significantly reduce scene visibility, contrast, and structural fidelity. Single-weather restoration models focus on learning the specific degradation characteristics of one weather phenomenon and generating a clean, high-quality image that approximates the underlying scene radiance. Single-image weather restoration primarily encompasses tasks such as image dehazing, deraining, and desnowing.

Despite their success, single-weather restoration methods are typically designed under task-specific assumptions and optimized independently for each degradation type. As a result, these models often lack generalization across different weather conditions and cannot effectively handle scenarios where multiple or unknown degradations coexist. This task-isolated design also limits their scalability and applicability in real-world settings, motivating the exploration of more unified and adaptive restoration frameworks.

Image dehazing seeks to remove haze or fog that arises from the scattering and absorption of light by atmospheric particles. Haze reduces global contrast and introduces depth-dependent attenuation, making distant objects appear washed out. Dehazing algorithms estimate the transmission map and atmospheric light or learn the haze formation process through deep networks to recover clear scene information. Early dehazing methods heavily rely on physical priors or simplified atmospheric models, which often break down in complex real-world scenes with non-uniform haze or unknown depth distributions. Zhang et al. [13] proposed a depth-assisted dual-task collaborative mutual promotion framework that jointly optimizes image dehazing and depth estimation, addressing the limitation that many dehazing methods overlook the intrinsic correlation between scene depth and haze distribution. Feng et al. [14] introduced a real-world image dehazing framework incorporating a multi-factor haze degradation model, a localization and removal network, and a Gaussian perceptual contrastive loss, effectively alleviating the domain gap and poor generalization issues commonly observed in prior dehazing approaches. Nevertheless, these methods remain specialized for haze removal and are not readily extensible to other weather degradations.

Image deraining aims to eliminate rain streaks, raindrops, or rain accumulation that degrade outdoor images. Rain causes structured, high-frequency streaks and spatially varying occlusions. Deraining methods focus on separating rain components from background content by leveraging priors, motion cues, or data-driven features. Many existing deraining models assume a specific rain scale or pattern, which limits their robustness when facing diverse rain types or mixed degradations. Chen et al. [11] proposed a bidirectional multi-scale Transformer enhanced with implicit neural representations to jointly capture scale-specific and shared rain degradation features, addressing the limitation of single-scale Transformer models. Song et al. [10] proposed ESDNet, an efficient spiking neural network with spiking residual blocks and mixed attention to mitigate information loss and training instability in SNN-based deraining. Wu et al. [32] proposed MSPformer, which leverages conditional soft prompts and multi-scale feature fusion to dynamically adapt to varying rain patterns. Although effective, these approaches are still tailored to rain-specific artifacts and lack a unified mechanism to adapt across different weather conditions.

Image desnowing deals with removing snow particles or snow accumulation that occlude the visual scene. Compared to rain, snow introduces irregular shapes, varying opacity, and large opaque regions, making restoration more challenging. The high diversity and randomness of snow distributions further exacerbate the data scarcity and generalization issues in desnowing models. Lai et al. [9] proposed the RealSnow10K dataset along with an expert-ranked preference learning strategy and the SnowMaster framework, which improves evaluation reliability and pseudo-label filtering for real-world snowy images. However, similar to dehazing and deraining methods, existing desnowing models are developed in isolation and cannot generalize beyond the snow-specific setting.

Overall, while single-weather restoration methods achieve impressive performance within their respective domains, their task-specific design and limited adaptability hinder their effectiveness in open-world scenarios involving diverse or mixed weather degradations. These limitations motivate the development of more unified and flexible restoration frameworks capable of generalizing across weather conditions, which is the focus of our proposed approach.

2.2. All-in-One Weather Image Restoration

All-in-one weather image restoration refers to a unified restoration framework designed to handle multiple types of weather induced degradations within a single model, such as haze, rain, snow, and low-light conditions. Instead of training separate networks for each weather scenario, all-in-one approaches aim to learn a generalized degradation representation that can adaptively identify diverse weather patterns and recover clean images accordingly. This unified paradigm not only reduces model redundancy and improves computational efficiency but also enhances robustness and generalization in real world environments where different weather conditions often coexist or appear unpredictably.

Li et al. [33] proposed AirNet, an end-to-end unified framework for multi-degradation image restoration that does not require prior knowledge of the type or intensity of degradation. AirNet addresses the limitations of existing image restoration methods, where models designed for a single degradation can only handle specific types of degradation, and multi degradation methods depend on degradation priors or complex multi branch structures. It is capable of handling unknown, mixed, and spatially varying degradations in real world scenarios. Valanarasu et al. [21] proposed TransWeather, a transformer-based model with a single encoder and a single decoder. The model introduces novel intra-patch transformer blocks and learnable weather type queries in the decoder, enabling unified restoration of images degraded by various adverse weather conditions. TransWeather overcomes key limitations of existing methods, such as the high computational cost of multi-encoder architectures, the limited generalization of models fine-tuned for a single task, and the inefficiency of single models in handling multiple weather degradations. At the same time, it achieves superior quantitative and qualitative performance while offering faster inference speeds. Patil et al. [22] proposed a unified framework for multi-weather image restoration based on domain translation. This framework addresses the limitations of existing multi-weather restoration methods, including the reliance on weather-specific encoders or separate training, limited ability to handle complex real world weather, and high computational cost, while improving domain generalization and enhancing performance in downstream tasks. Wen et al. [23] proposed the MPMF-Net for all-in-one weather degraded image restoration, it solved the issues of poor image quality, long inference time, single dimensional prompt learning, weak adaptive feature fusion, and difficult degradation normalization in existing all-in-one weather image restoration methods.

2.3. Multi-Task Learning

Multi-task learning (MTL) is a machine learning paradigm in which a single model is trained to simultaneously learn multiple related tasks by sharing representations across them. Instead of training separate models for each task, MTL leverages the intrinsic correlations among tasks to promote mutual reinforcement, enabling the model to learn more robust and generalized features. By sharing knowledge across tasks, MTL improves learning efficiency, reduces overfitting, and often yields superior performance compared to single-task approaches, especially when tasks exhibit strong semantic or structural relationships [34,35,36,37,38].

Despite these advantages, naïvely applying multi-task learning often leads to negative transfer, task imbalance, or optimization conflicts, especially when task difficulties, data distributions, or convergence behaviors differ significantly. These challenges limit the effectiveness of conventional MTL frameworks when directly extended to complex real-world restoration scenarios. Chen et al. [39] systematically studied optimization techniques for MTL, including loss construction, gradient regularization, data sampling, and task scheduling, and summarized their applications across auxiliary MTL, joint MTL, and multilingual/multimodal NLP tasks. Fifty et al. [40] proposed task affinity grouping (TAG), which quantifies inter-task gradient interactions to determine optimal task groupings, addressing performance degradation caused by indiscriminately training all tasks together and the high cost of exhaustive task grouping search. These works highlight that effective MTL requires careful modeling of task relationships and controlled knowledge sharing, rather than uniform parameter sharing across all tasks. Wu et al. [24] addressed the challenge of restoring UAV remote sensing images under diverse adverse weather conditions by proposing a multiple-in-one image restoration strategy. They designed a scale-aware Trident Mamba architecture with multi-resolution and multi-patch modeling to enable unified feature extraction across different weather degradations.

However, existing multi-task or all-in-one restoration models often rely on shared backbones with limited task-specific adaptation, which may struggle to accommodate heterogeneous degradation characteristics and dynamic task interactions. In this work, we leverage multi-task learning not merely as a parameter-sharing strategy, but as a collaborative learning mechanism. By integrating a mixture-of-experts feature extraction module with a multi-task collaborative training strategy, our model dynamically routes task-relevant features and mitigates task interference. This design enables more flexible knowledge sharing across weather restoration tasks while preserving task-specific discrimination, effectively overcoming the limitations of prior MTL-based restoration approaches.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overall Network Architecture

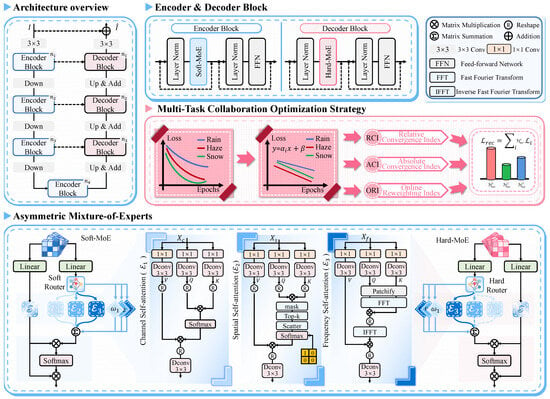

We present a unified image restoration framework tailored for adverse weather conditions, named MOE-WIRNet, as shown in Figure 1. The proposed network adopts a symmetric encoder-decoder framework characterized by an asymmetric routing mechanism across its feature extraction and reconstruction stages. The asymmetric MoE routing strategy is intentionally aligned with the optimization characteristics of different network stages. The encoder prioritizes adaptive representation learning through soft routing to accommodate diverse degradation patterns, while the decoder enforces stable expert selection via hard routing to ensure consistent high-frequency reconstruction across tasks. Specifically, both the encoder and decoder incorporate a comprehensive mixture-of-experts (MoE) feature extraction module at each level. This module concurrently integrates three specialized self-attention experts, spanning the channel, spatial, and frequency domains, to capture diverse degradation characteristics. In the encoder stage, a soft routing mechanism is employed to perform dynamic weighted fusion of these multi-dimensional features, thereby adaptively synthesizing task-specific representations . Conversely, the decoder utilizes a hard routing mechanism, which assigns uniform weights to the three expert branches to ensure stable and balanced feature restoration within a unified parameter space. From the perspective of symmetry, the proposed encoder–decoder framework adopts a structurally symmetric design, where all degradation types are projected into a shared latent space through a unified encoder and reconstructed via decoder branches of consistent topology. This architectural symmetry enforces a common representational basis, facilitating feature alignment and knowledge sharing across tasks. However, functional asymmetry is deliberately introduced at the decoding stage, where task-specific decoding pathways adapt the shared latent representations to heterogeneous degradation characteristics. Such asymmetric decoding enables the model to preserve degradation-specific restoration behaviors while maintaining global structural consistency, thereby balancing universality and specificity.

Figure 1.

The overall structure of the MOE-WIRNet, designed for all-in-one weather image restoration.

In the operational workflow, a degraded image initially undergoes overlap patch embedding via convolutions to generate high-dimensional shallow features . The encoder subsequently processes these features through a four-tier hierarchy, where downsampling operations progressively increase channel depth while expanding the semantic receptive field. This architectural design enables the encoder to decouple complex degradation components through scale-aware feature synthesis under soft routing guidance, while the decoder accurately reconstructs the clean image by integrating features through a consistent hard routing integration.

After capturing highly abstract context in the bottleneck layer, the decoder reinstates spatial resolution through symmetrical upsampling. Skip connections [11] facilitate the fusion of multi-scale encoder details with decoder features to replenish lost high-frequency information. This process is mathematically formulated as:

where signifies the channel-wise concatenation, and and represent the upsampling and decoder layer transformations, respectively. The final output is derived through global residual learning, the residual map is generated via the refinement module , adding the predicted residual map to the original input:

To harmonize learning across diverse weather tasks within a unified parameter space, we introduce an active reweighting-based multi-objective optimization strategy during training. By framing multi-weather restoration as a multi-task learning challenge, this approach equilibrates optimization rates across various degradation tasks, effectively resolving gradient interference and convergence disparities inherent in mixed training. This synergy of a robust perception architecture and dynamic optimization enables high-fidelity restoration for complex weather scenarios, including rain, haze, and snow.

3.2. MoE Feature Extraction Module

The asymmetric routing strategy in MOE-WIRNet is grounded in the distinct functional requirements of the encoder and decoder. Specifically, the encoder focuses on adaptive feature extraction from diverse degradation scenarios, allowing the soft routing mechanism to dynamically weight multiple experts based on the input feature characteristics. In contrast, the decoder prioritizes stable and high-quality reconstruction, where hard routing ensures balanced integration of expert features and prevents oscillations or artifacts. This alignment of routing strategy with stage-specific functional needs motivates the encoder-decoder asymmetry in our design.

To efficiently mitigate adverse weather degradations with distinct physical characteristics, such as rain streaks, haze, and snow, within a unified framework, the proposed architecture integrates MoE feature extraction module in the encoder stages. The core philosophy of this module involves distributing the feature stream among multiple parallel expert sub-networks to address diverse degradation representations, subsequently utilizing a dynamic soft routing mechanism for adaptive feature fusion. At each hierarchical level of the encoder, the module accepts input features from the preceding layer. To facilitate high-efficiency multi-dimensional feature extraction, the module first applies a convolutional layer for linear mapping and subsequently partitions the features along the channel dimension into three distinct sub-feature spaces. These spaces correspond to the channel, spatial, and frequency self-attention experts:

where denote the respective input features for each specialized expert branch. The denotes a linear transformation that projects the input features into a more discriminative embedding space, which helps the soft router make more effective routing decisions and improves feature selection. This design allows the encoder to capture complex degradation cues across channel, spatial, and frequency domains simultaneously, ensuring a robust perception of heterogeneous weather distortions.

Channel Self-attention Expert. The channel self-attention expert is specifically engineered to mitigate global image distortions, such as the contrast reduction characteristic of haze induced by dust storms, where degradation exhibits high spatial correlation. This expert utilizes MDTA [27] to extract global contrast information and model inter-channel dependencies while deliberately bypassing redundant spatial-dimension interactions. By prioritizing cross-covariance modeling, the expert effectively reconstructs scenes affected by global clarity loss, rectifying anomalous and skewed luminance distributions.

The process begins by projecting the input feature into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) representations. To compute attention without sacrificing local spatial integrity, the module integrates point-wise convolution with depth-wise convolution:

where aggregates information across channels via point-wise convolution, while encodes localized spatial constraints during the projection stage via depth-wise convolution. The transposed attention strategy shifts the computational bottleneck from spatial pixels to feature channels. The generated and V tensors are reshaped from to , where . To enhance training stability and constrain feature magnitudes, normalization is applied to Q and K prior to computing their inner product. The resulting channel-wise attention map is derived as:

where and represent the normalized matrices, and is a learnable temperature coefficient that adaptively smooths the attention distribution. This map effectively captures global feature correlations, such as the unique wavelength distribution of haze particles. Finally, the attention map is applied to the value tensor V, followed by a linear transformation and a residual connection to produce the restored features:

where signifies the output projection layer. This mechanism identifies and rectifies global weather-related degradations at a minimal computational cost.

Spatial Self-attention Expert. Unlike the channel self-attention expert, which emphasizes cross-channel global modeling, the spatial self-attention expert focuses on extracting pixel-level spatial dependencies to address degradations with pronounced spatial non-uniformity, such as rain streaks and snowflakes. While both experts employ a similar parallel branch structure during the feature projection phase, the spatial self-attention expert exhibits a distinct interaction logic centered on a sparsification pipeline designed to enhance restoration specificity. Upon generating the Query (Q) and Key (K) tensors, this expert does not compute cross-covariance matrix like its channel-based counterpart. Instead, it establishes associations directly in the pixel dimension and immediately applies a mask operation to filter the interaction matrix. This step suppresses interference from clear background regions on the attention distribution. To further minimize computational redundancy and precisely isolate significant degradation areas, the expert utilizes a unique Top-k selection strategy, formulated as:

where represents the raw correlation scores between any two spatial coordinates. The mask operation prunes physically irrelevant long-range or low-quality interactions. The critical Top-k operator then implements the spatial sparsification logic, for each query pixel, the model retains only the k most correlated points. This process is vital for tasks like snow or heavy rain removal, as it forces the model to concentrate its attention on the most salient degradation features, such as snowflake edges or rain streak trajectories, while disregarding redundant clear background information. The filtered scores are subsequently remapped to the full matrix dimensions via a scatter operation and normalized using a softmax function to produce the sparse spatial attention map . Following the feature aggregation stage, the spatial self-attention expert introduces a distinct architectural refinement, an additional depth-wise convolution (DConv) layer at the output. This process is defined as:

where performs feature aggregation based on sparse weights, and the reshape operation restores the aggregated sequence into a four-dimensional spatial tensor. The final DConv acts as a local structure reinforcer. Since the self-attention mechanism primarily captures long-range dependencies, and the Top-k selection may introduce spatial discretization or block artifacts, this convolutional layer provides secondary filtering over local neighborhoods. This significantly enhances the continuity between restored regions and surrounding pixels. This supplementary spatial smoothing ensures that restored edge details possess higher coherence in visual perception, resulting in superior fidelity when processing weather tasks with complex spatial structures.

Frequency Self-attention Expert. The frequency self-attention expert aims to achieve precise separation of degradation components from a signal processing perspective. This is necessitated by the fact that weather-related degradations, such as rain streaks or structural noise, frequently overlap with image textures in the spatial domain but exhibit distinct energy distributions in the frequency domain. Fundamentally different from the channel or spatial experts, this module relies on non-linear mappings across the spatio-temporal and frequency domains combined with global feature interactions. Following the parallel projection to generate the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) tensors, the frequency expert initiates a feature transformation process. To efficiently capture local frequency patterns and reduce computational complexity, the input feature maps are partitioned into patches before applying the Fourier transform. Patchification enables the module to focus on localized spectral components, improving the discrimination between degradation signals (e.g., rain streaks) and natural image textures, while keeping the attention computation tractable. For partitioned feature patches, a 2D fast fourier transform (FFT) maps the spatial features into the complex frequency domain:

where denotes the FFT operator. It decomposes local features into a feature representation where amplitude information reflects the energy distribution of the signal, and phase information encapsulates its structural characteristics. The core interaction of the frequency expert occurs within the feature plane, implementing a self-attention mechanism through the complex conjugate dot product of the frequency components:

where represents the complex conjugate operation. The physical significance of this formula lies in performing frequency-domain correlation retrieval to identify feature components in that are similar to . This operation performs a correlation retrieval between the query and key in the frequency domain, effectively highlighting energy distributions associated with weather-induced degradations (e.g., rain streaks or structural noise). Since these degradations often exhibit distinct periodic patterns compared with natural image textures, the frequency-domain dot product selectively amplifies these degradation components, enabling their separation from the authentic textures. The subsequent IFFT mapping transforms this attention back to the spatial domain, providing a weight map that emphasizes degraded regions. Finally, the element-wise multiplication with V ensures that only the degraded components are filtered or suppressed while preserving the underlying image structures, allowing precise and physically meaningful restoration. Subsequently, the resulting weight matrix is mapped back to the spatial domain via an inverse fast fourier transform (IFFT) operator, , yielding a spatial weight map integrated with global frequency insights. In the final feature synthesis stage, the frequency expert generates the refined features through the following mapping:

where ⊗ denotes the element-wise multiplication, which utilizes the learned feature saliency weights to re-calibrate the value tensor V. This enables the precise filtering of pixel components contaminated by weather degradations in the spatial domain. To mitigate periodic artifacts potentially introduced by feature truncation or the initial patchification process, the outermost layer incorporates a depth-wise convolution. This convolutional layer functions as a feature smoothing filter, ensuring that the final output maintains frequency fidelity while exhibiting natural spatial coherence and continuity.

Soft Routing Mechanism. The soft routing mechanism adaptively modulates the contributions of various experts by learning the distribution patterns of different degradation types within the feature space. The module defines a set of learnable gating parameters , which represent the fundamental weight baselines for the channel, spatial, and frequency experts at the current hierarchical level. To establish a balanced relationship of both competition and collaboration among experts, the system employs a Softmax function during the inference phase to perform a non-linear mapping on these gating parameters, yielding normalized mixing coefficients :

Through exponential computation, the softmax operator amplifies the disparities between weights. This allows the model to significantly elevate the confidence of a specific expert, such as the share expert (s) when encountering periodic rain streaks, while simultaneously suppressing noise interference from irrelevant dimensions, thereby achieving precise task focusing.

Upon obtaining these adaptive weights, the output feature maps from each expert branch undergo weighted scaling before entering the fusion layer via a channel-wise concatenation operation:

where operator denotes concatenation along the channel dimension. Since each expert branch processes only one-third of the original channel count (), the concatenation re-aggregates these heterogeneous features into a mixed tensor of dimension C. A subsequent Fusion Convolution layer facilitates cross-expert information interaction, performing a non-linear integration of features derived from the spectral, local spatial, and global channel domains. To maintain training stability when the deep network processes extreme weather conditions, the module ultimately outputs the final features through Layer Normalization (LN) and a global residual connection:

the LN layer standardizes the feature distribution by its mean and variance, which effectively prevents potential gradient explosion or vanishing issues that might arise from drastic fluctuations in gating weights. This ensures the robustness of the multi-task collaborative optimization process.

Hard Routing Mechanism. In contrast to the soft routing mechanism, the hard routing mechanism enforces a discrete selection of a single expert for each feature map, effectively choosing the most relevant pathway based on the current degradation characteristics. Specifically, the gating parameters are first computed in the same manner as in soft routing. Instead of applying a softmax to obtain weighted contributions, the expert with the highest gating value is selected:

and only the corresponding feature map is forwarded to the fusion stage. The selected feature is then passed through the same fusion convolution, residual connection, and Layer Normalization as in the soft routing design. This hard selection strategy reduces computational overhead by avoiding unnecessary processing of irrelevant experts, and enforces a more decisive expert specialization. While it may be less flexible than soft routing in blending complementary features, it can improve efficiency and encourage expert modules to fully focus on their designated degradation types.

3.3. Multi-Task Collaborative Training Strategy

In adverse weather restoration tasks, traditional joint training paradigms with fixed weights often suffer from unbalanced optimization rhythms due to the significant heterogeneity in feature distributions, optimization difficulties, and gradient magnitudes across various degradation types. From a multi-task optimization perspective, such imbalance arises because different tasks progress at different convergence rates and may temporarily dominate shared parameters, leading to task interference and suboptimal joint solutions. To address this challenge, this study formulates the restoration process as a multi-task collaborative system and introduces an online reweighting strategy based on convergence state awareness. By quantifying the convergence status of each task in real-time, this strategy dynamically evolves an optimal loss weight distribution, facilitating seamless synergy among sub-tasks within a unified parameter space. Rather than heuristically assigning fixed or pre-defined weights, our strategy explicitly monitors task-wise convergence behaviors and dynamically coordinates their optimization priorities, aiming to equalize effective learning progress across tasks.

Relative Convergence Index. To accurately characterize the instantaneous optimization dynamics of each restoration task during specific training stages, we define the relative convergence index (RCI), denoted as . Conceptually, RCI serves as a normalized indicator of relative convergence speed, measuring whether a task is currently learning faster or slower than its recent historical trend under the same optimization conditions. Given the stochastic fluctuations of loss values in deep learning, we first establish a smoothed historical loss baseline, , utilizing an exponential moving average (EMA) strategy to suppress high-frequency noise inherent in mini-batch training:

where is the dynamic weight vector across t types, represents the raw loss value of task t at the current iteration, while serves as the momentum coefficient controlling the decay of historical information. Based on this baseline, the RCI for task t is defined as the normalized ratio of the current loss to the smoothed historical baseline:

where functions as a metric for the adaptive evolutionary pace. An indicates that the learning progress of the task lags behind its historical average, suggesting a weakened ability of the model to capture those specific degradation features. Conversely, signifies that the task is in a stable state of convergence.

Absolute Convergence Index. Monitoring RCI alone is insufficient to reflect the model’s progress relative to the global optimum. A task may exhibit stable short-term convergence while still remaining far from its best-achieved performance, which motivates the need for an absolute reference. Therefore, we propose the absolute convergence index (ACI), denoted as , to serve as a long-term steady-state anchor. This factor constrains the optimization direction by quantifying the absolute deviation between the current performance state and the limit performance achieved during its training history:

where represents the global minimum loss recorded for task t since the start of training. The introduction of the logarithmic transformation aims to compress the fluctuation range of loss values, thereby providing a more robust feedback signal. A rising alerts the system that the model is drifting away from its best-attained state for a specific weather condition, triggering a restorative force to pull the optimizer back toward the high-fidelity restoration trajectory.

Online Reweighting Index. By integrating the RCI () with the ACI (), we generate the final online reweighting index (ORI), denoted as , for the dynamic allocation of loss weights across tasks. The joint use of RCI and ACI provides complementary feedback: RCI emphasizes short-term convergence imbalance, while ACI enforces long-term performance consistency, enabling principled task coordination during optimization. To ensure higher discriminative power while maintaining weight normalization, we employ a Softmax function with a temperature coefficient for adaptive synthesis:

where the speed and quality of convergence through the product term . The temperature coefficient modulates the smoothness of the weight distribution, a lower encourages the model to exhibit a stronger punishment bias towards extremely difficult tasks. Consequently, this strategy enables the model to actively identify and intensify training on weak tasks during every iteration. By harmonizing the optimization paths of rain, haze, and snow tasks, the ORI mechanism significantly enhances restoration accuracy and robustness in complex multi-degradation scenarios.

3.4. Loss Function

To facilitate comprehensive feature learning, we design a composite loss function that integrates pixel-, edge-, and frequency-level constraints for remote sensing image dehazing. We adopt the robust Charbonnier loss to penalize pixel-wise discrepancies between the reconstructed image and the ground truth at multiple scales ():

To preserve structural details, an edge-aware loss based on the Laplacian operator is introduced:

Spectral consistency is enforced via an loss in the Fourier domain ( denotes Fourier Transform):

The total loss is a weighted combination of the above terms:

where the weights are set as , following common practice in prior work [31].

4. Experiments

4.1. Experiments Setup

This research utilizes WeatherBench [28] and FoundIR-Weather [4] as the primary benchmarks for training and evaluation. These datasets are specifically curated to assess the performance of all-in-one restoration algorithms within heterogeneous outdoor environments. WeatherBench encompasses not only isolated degradations such as rain streaks, snow accumulation, and dense haze but also addresses composite degradation processes resulting from overlapping weather phenomena. The WeatherBench dataset contains a total of 42,002 image pairs, including 14,729 training pairs in the Rain subset, 13,614 training pairs in the Haze subset, and 13,059 training pairs in the Snow subset; each subset includes 200 image pairs for testing. While the FoundIR dataset offers an extensive range of scenarios, this study focuses exclusively on four weather-centric categories: haze, rain streaks, raindrops, and nighttime rain. In the FoundIR-Weather dataset, the haze subset contains 79,800 images for training and 200 images for testing; the rainstreak subset contains 39,900 images for training and 100 images for testing; the raindrop subset contains 44,828 images for training and 100 images for testing; and the nighttime rain subset contains 40,111 images for training and 50 images for testing. To ensure a fair comparison, we use the officially released code for all comparison methods and retrain and test them under the same experimental settings.

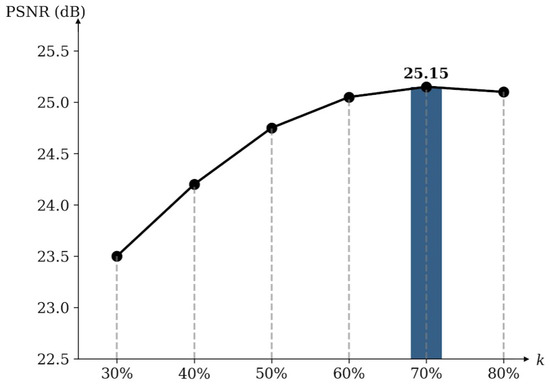

In our network, we adopt the same number of heads configuration as MDTA [27], i.e., [1, 2, 4, 8], and set the k value to 70%. Regarding implementation, the computational framework operates on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090D GPU, where the Adam optimizer facilitates end-to-end parameter learning. The initial learning rate is established at and undergoes adaptive reduction to through a cosine annealing strategy to ensure a stable and smooth optimization trajectory. The training configuration maintains a batch size of 1 to balance memory constraints and gradient stability. The entire optimization procedure spans approximately 300,000 iterations, allowing the model to fully converge and capture the underlying statistical distributions of diverse weather-induced artifacts.

4.2. Evaluation on the WeatherBench Dateset

In the experimental evaluation on the WeatherBench dataset, the proposed framework demonstrates competitive overall performance among the compared methods in both quantitative metrics (as shown in Table 1) and qualitative visual results. Quantitative assessments reveal that the model consistently outperforms state-of-the-art (SOTA) restoration algorithms across two primary metrics, PSNR and SSIM. This comprehensive performance gain is largely attributed to the MoE feature extraction module, which accurately decouples heterogeneous degradation features, and the multi-task collaborative training strategy, which effectively synchronizes multi-task convergence trajectories. Consequently, the restored outputs achieve high-level semantic alignment with ground-truth imagery.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of different categories of methods on the WeatherBench [28] dataset. The best and second-best values are bold and underlined. “↑” indicates better performance with higher values.

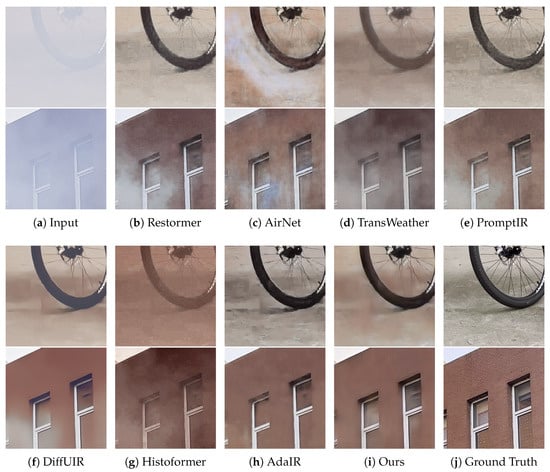

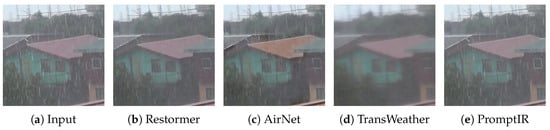

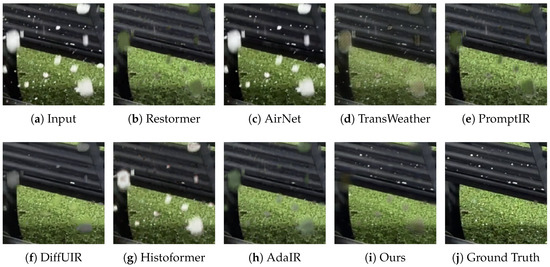

Regarding qualitative visual comparisons, the architecture exhibits exceptional high-fidelity reconstruction capabilities, as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. In rainy scenarios, the frequency self-attention expert leverages its sensitivity to spectral cues to precisely identify and eliminate rain patterns characterized by periodic physical patterns. When addressing global degradation caused by dense haze, the channel expert utilizes cross-covariance modeling to rectify spectral shifts induced by atmospheric scattering. As shown in Figure 2, compared with AdaIR [49], our method can more accurately restore colors and preserve finer structural details, such as the wall cracks highlighted in the figure. Simultaneously, the spatial self-attention expert employs a sparse Top-k selection strategy to handle non-uniform snow degradation, thereby ensuring the structural continuity and integrity of object boundaries.

Figure 2.

The restored results of dehazing on the WeatherBench dataset. Our method restores high-quality images with more defined details than the restored results shown in (b–h).

Figure 3.

The restored results of deraining on the WeatherBench dataset. Our method restores high-quality images with more defined details than the restored results shown in (b–h).

Figure 4.

The restored results of desnowing on the WeatherBench dataset. Our method restores high-quality images with more defined details than the restored results shown in (b–h).

4.3. Evaluation on the FoundIR-Weather Dataset

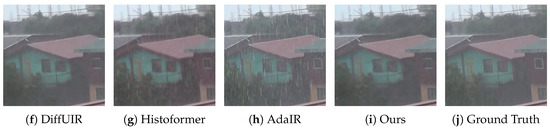

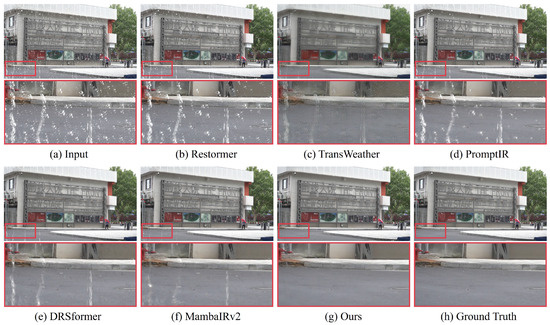

In extended experiments on the FoundIR-Weather dataset, the proposed method achieves superior performance across four highly challenging weather scenarios: haze, rain streaks, raindrops, and nighttime rain. Quantitative assessments reveal that our approach consistently outperforms SOTA algorithms in PSNR and SSIM for all degradation categories. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, our method outperforms the dedicated dehazing algorithm DehazeFormer [41] by approximately 5.48 dB in PSNR on the dehazing task. It also surpasses the multi-weather restoration method TransWeather [21] by about 1.46 dB in average PSNR and 0.0169 in SSIM. This superiority substantiates that the multi-task optimization training strategy effectively prevents the model from converging to local optima or suffering from performance degradation during the simultaneous optimization of multiple tasks. Qualitative visual analysis further confirms the model’s robustness against complex physical degradations, as depicted in Figure 5. This collaborative multi-expert paradigm ensures that the model maintains macro-level contrast and visual naturalness while simultaneously reconstructing micro-level geometric details across the diverse degradation distributions of FoundIR-Weather.

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluations on the FoundIR-Weather [4] dataset. The best and second-best values are bold and underlined. “↑” indicates better performance with higher values.

Table 3.

Quantitative evaluation using no-reference metrics on the RainStreak and Haze subsets of the FoundIR-Weather [4] dataset. The best and second-best values are bold and underlined. “↑” indicates higher is better, while “↓” indicates lower is better.

Figure 5.

The restored results of raindrop removal on the FoundIR-Weather dataset. Our method restores high-quality images with more defined details than the restored results shown in (b–f).

4.4. Model Complexity

To evaluate the model complexity (number of parameters) and computational cost (floating-point operations, FLOPs), we compare our method with representative state-of-the-art approaches, including task-specific methods (DehazeFormer [41], DRSformer [12], and NeRD-Rain [11]), task-general methods (MPRNet [43] and Restormer [27]), and the all-in-one method PromptIR [44]. Specifically, all efficiency evaluations are conducted under a unified input resolution of , and the results are summarized in Table 4. The analysis indicates that our method achieves lower model complexity while maintaining competitive performance, thereby attaining a better balance between restoration quality and computational efficiency.

Table 4.

Comparisons of model complexity. The size of the test image is pixels.

4.5. Ablation Studies

Effectiveness of the asymmetric MOE network architecture. This study validates the pivotal role of the proposed asymmetric routing mechanism in the all-in-one image restoration task through ablation experiments, as summarized in Table 5. During the encoding phase, the model encounters highly heterogeneous degradation features such as rain, haze, and snow. The implementation of a soft routing mechanism enables the model to dynamically and adaptively calibrate the contribution ratios of various experts according to the specific degradation distribution of the input image, thereby facilitating precise feature decoupling and artifact capture.

Table 5.

Ablation study of the asymmetric mixture-of-experts network architecture. “✓” indicates that the corresponding component is used, and “✗” indicates that the corresponding component is not used. “↑” indicates better performance with higher values.

Conversely, the decoding stage prioritizes high-fidelity image reconstruction and synthesis. By adopting a hard routing strategy that assigns uniform weights (1/3 each) to the three expert branches, the decoder provides a robust and balanced feature integration environment. This asymmetric design significantly outperforms all variants from (a) to (d) in terms of evaluation metrics, substantiating that customizing routing strategies based on the functional characteristics of the encoder and decoder is essential for enhancing the precision of all-in-one restoration models.

Effectiveness of different expert types in the MoE architecture. To ascertain the individual efficacy of various expert types within the MoE, we evaluate several configurations of channel, spatial, and frequency self-attention experts, as summarized in Table 6. Case (e) serves as a baseline utilizing only channel self-attention, which exhibits limited capacity in mitigating degradations characterized by intricate geometric structures or periodic textures.

Table 6.

Ablation study of different MoE expert types in Hard-MoE and Soft-MoE. “✓” indicates that the corresponding component is used, and “✗” indicates that the corresponding component is not used. “↑” indicates better performance with higher values.

The integration of spatial self-attention in case (f) markedly bolsters the model’s ability to localize non-uniform physical distortions, yielding substantial gains in PSNR and SSIM. Simultaneously, case (g) validates the pivotal role of the frequency self-attention expert in eliminating periodic physical artifacts. Ultimately, our comprehensive MoE framework, which integrates all three specialized dimensions, achieves superior performance across all evaluation metrics. This confirms the high degree of complementarity among these feature domains, their collaborative decoupling allows the model to attain optimal restoration fidelity when addressing diverse and heterogeneous weather-induced degradations.

Effectiveness of multi-task collaborative training strategy. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-task collaborative training strategy, we conduct a comprehensive ablation study by comparing it with alternative schemes adopting different optimization strategies. The quantitative results are reported in Table 7. It is observed that, without any optimization strategy, the model exhibits a clear performance bias, resulting in inferior restoration quality on more challenging degradation scenarios. Introducing the RCI-based reweighting approach alleviates this issue to some extent by adjusting task weights according to short-term optimization dynamics; however, this method remains sensitive to stochastic loss fluctuations and may lead to unstable weight oscillations. In contrast, the full collaborative training strategy consistently achieves the best performance across all degradation types, confirming that the absolute convergence index provides a crucial long-term constraint that anchors each task to its historical optimum. These results demonstrate that the proposed multi-task collaborative training strategy effectively balances convergence speed and restoration quality among heterogeneous tasks, enabling more coordinated optimization and exhibiting superior robustness in multi-degradation image restoration scenarios.

Table 7.

Ablation study on our multi-task collaborative training strategy. “✓” indicates that the corresponding component is used, and “✗” indicates that the corresponding component is not used. “↑” indicates better performance with higher values.

Effect of different values of k. To investigate the performance variation of the model under different top-k values, we conduct an ablation study, as shown in Figure 6. The results indicate that setting k to 70% achieves the best performance, with PSNR reaching 25.15 dB. When k is small, some useful information may be filtered out, leading to performance degradation. When k is increased to 80%, the performance instead shows a declining trend, which further demonstrates the effectiveness of the top-k selection mechanism. This mechanism reduces redundant information and suppresses irrelevant interference, thereby enhancing the model’s image restoration capability.

Figure 6.

Ablation studies for different values of k of the top-k token selection mechanism in the model.

4.6. Discussion and Limitations

While MOE-WIRNet demonstrates strong performance on unified adverse weather image restoration, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the proposed framework is primarily designed for adverse weather restoration tasks (e.g., rain, haze, and snow), which share common physical characteristics such as atmospheric scattering, occlusion, and visibility degradation. When extending MOE-WIRNet to more general all-in-one image restoration scenarios that include heterogeneous degradations (e.g., noise, blur, compression artifacts, and low-light conditions), performance gains may become less consistent. This is mainly because the assumption of partial task relatedness, which underlies both the collaborative optimization strategy and the expert-sharing mechanism, becomes weaker in such settings. We plan to further explore more general all-in-one image restoration scenarios in future work, such as sandstorms, noise, blur, and compression artifacts.

5. Conclusions

We have presented an effective all-in-one adverse weather image restoration framework, named MOE-WIRNet. We formulate a multi-task collaborative optimization strategy that dynamically coordinates the training of multiple restoration objectives to harmonize cross-task learning and enhance overall performance. Furthermore, we integrate an asymmetric mixture-of-experts architecture into the framework to adaptively address the distinct degradation patterns and varying severity levels across different adverse weather conditions. Extensive experiments and ablation analysis confirm the importance of multi-task equilibrium in training, and demonstrate that our method achieves state-of-the-art results on multiple real-world benchmarks.

Author Contributions

Methodology, J.C.; Software, J.C.; Validation, J.C.; Formal analysis, J.C.; Data curation, Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, J.C.; Writing—review & editing, Z.Z.; Supervision, Z.Z.; Funding acquisition, Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62475077).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [WeatherBench] at https://github.com/guanqiyuan/WeatherBench (accessed on 28 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Dong, J.; Tang, J. Towards unified deep image deraining: A survey and a new benchmark. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 5414–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, G.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, T. Testing of autonomous driving systems: Where are we and where should we go? In Proceedings of the 30th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Singapore, 14–18 November 2022; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chavhan, S.; Gupta, D.; Gochhayat, S.P.; Chandana, B.N.; Khanna, A.; Shankar, K.; Rodrigues, J.J. Edge computing AI-IoT integrated energy-efficient intelligent transportation system for smart cities. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2022, 22, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Dong, J.; Tang, J.; Pan, J. Foundir: Unleashing million-scale training data to advance foundation models for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 12626–12636. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, P.; Guan, Q.; Jin, G.; Jin, J. Rethinking Rainy 3D Scene Reconstruction via Perspective Transforming and Brightness Tuning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.06734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Yao, K.; Goel, S. Surveilling surveillance: Estimating the prevalence of surveillance cameras with street view data. In Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Virtual, USA, 19–21 May 2021; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q.; Chen, X.; Jin, G.; Jin, J.; Fan, S.; Song, T.; Pan, J. Rethinking Nighttime Image Deraining via Learnable Color Space Transformation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.17440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shu, X.; Feng, C.M.; Feng, Y.; Zuo, W.; Tang, J. Surgical video workflow analysis via visual-language learning. npj Health Syst. 2025, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, Y.; Ye, T.; Liu, Y.; Fei, S.; Xing, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, L. SnowMaster: Comprehensive Real-world Image Desnowing via MLLM with Multi-Model Feedback Optimization. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 4302–4312. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.; Jin, G.; Li, P.; Jiang, K.; Chen, X.; Jin, J. Learning a spiking neural network for efficient image deraining. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.06277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Dong, J. Bidirectional multi-scale implicit neural representations for image deraining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 25627–25636. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Pan, J. Learning a sparse transformer network for effective image deraining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 5896–5905. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, H. Depth information assisted collaborative mutual promotion network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 2846–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Ma, L.; Meng, X.; Zhou, F.; Liu, R.; Su, Z. Advancing real-world image dehazing: Perspective, modules, and training. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 9303–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Fan, S.; Li, P.; Jin, J.; Jin, G.; Fan, L. Learning an effective transformer for remote sensing satellite image dehazing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Swinir: Image restoration using swin transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, USA, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ren, D.; Jiang, D.; Tian, Q.; Zuo, W. Improving image restoration through removing degradations in textual representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 2866–2878. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.; Li, P.; Jin, G.; Jin, J.; Fan, S.; Chen, X. Image deraining transformer with sparsity and frequency guidance. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Brisbane, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; pp. 1889–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Song, T.; Jin, G.; Jin, J.; Li, Q.; Xia, X. A lightweight cloud and cloud shadow detection transformer with prior-knowledge guidance. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8003405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Li, P.; Fan, S.; Jin, J.; Jin, G.; Fan, L. Exploring a context-gated network for effective image deraining. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2024, 98, 104060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Yasarla, R.; Patel, V.M. Transweather: Transformer-based restoration of images degraded by adverse weather conditions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 2353–2363. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.W.; Gupta, S.; Rana, S.; Venkatesh, S.; Murala, S. Multi-weather image restoration via domain translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 21696–21705. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, T. Multi-axis prompt and multi-dimension fusion network for all-in-one weather-degraded image restoration. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Xiao, Z.; He, J.; Lei, J.; Zeng, X.; Xu, G. Multi-weather unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing image restoration via scale-aware Trident Mamba. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2025, 19, 046507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yu, H.; Liao, C.; Liu, B.; Chen, C.; Li, J. Coba: Convergence balancer for multitask finetuning of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.06741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Dong, C.; Zhang, L. Towards effective multiple-in-one image restoration: A sequential and prompt learning strategy. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.03379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H. Restormer: Efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q.; Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Song, T.; Jin, G.; Jin, J. Weatherbench: A real-world benchmark dataset for all-in-one adverse weather image restoration. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Dublin, Ireland, 27–31 October 2025; pp. 12607–12613. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, E.; Wu, Z.; Mehta, N.; Tan, Y.; Paudel, D.P.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R. Complexity Experts are Task-Discriminative Learners for Any Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Yang, Q.; Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, P.; Chen, X. SmokeBench: A Real-World Dataset for Surveillance Image Desmoking in Early-Stage Fire Scenes. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Dublin, Ireland, 27–31 October 2025; pp. 12722–12728. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Y. Rethinking Multi-Scale Representations in Deep Deraining Transformer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, G. Multi-scale transformer with conditioned prompt for image deraining. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 156, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, X.; Hu, P.; Wu, Z.; Lv, J.; Peng, X. All-in-one image restoration for unknown corruption. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 17452–17462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, R.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, K. Advances and challenges of multi-task learning method in recommender system: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, R.M.; Bachute, M.R.; Gite, S.; Kotecha, K. Framework for deep learning-based language models using multi-task learning in natural language understanding: A systematic literature review and future directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17078–17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, S.; Hiss, J.A.; Schneider, G. Neural multi-task learning in drug design. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. A survey on multi-task learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 34, 5586–5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Meng, L.; Sun, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Q. Multi-task learning framework for emotion recognition in-the-wild. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. Multi-task learning in natural language processing: An overview. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifty, C.; Amid, E.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, T.; Anil, R.; Finn, C. Efficiently identifying task groupings for multi-task learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 27503–27516. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; He, Z.; Qian, H.; Du, X. Vision transformers for single image dehazing. IEEE TIP 2023, 32, 1927–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Ye, T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, E. SnowFormer: Context interaction transformer with scale-awareness for single image desnowing. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.09703. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Multi-stage progressive image restoration. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Virtual, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14821–14831. [Google Scholar]

- Potlapalli, V.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, S.; Khan, F. PromptIR: Prompting for All-in-One Image Restoration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 71275–71293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Fu, X.; Yang, X.; Guo, X.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, X. Learning weather-general and weather-specific features for image restoration under multiple adverse weather conditions. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 21747–21758. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Wu, X.M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.F.; Zheng, W.S. Selective hourglass mapping for universal image restoration based on diffusion model. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 25445–25455. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Tu, Z.; Liu, J.; Bovik, A.C.; Fan, Y. Mwformer: Multi-weather image restoration using degradation-aware transformers. IEEE TIP 2024, 33, 6790–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Ren, W.; Gao, X.; Wang, R.; Cao, X. Restoring images in adverse weather conditions via histogram transformer. In Proceedings of the ECCV, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, S.; Knoll, A.; Shah, M.; Khan, F.S. AdaIR: Adaptive All-in-One Image Restoration via Frequency Mining and Modulation. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Law, K.L.; Wang, X.; Qin, H.; Li, H. IDR: Self-Supervised Image Denoising via Iterative Data Refinement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Gustafsson, F.K.; Zhao, Z.; Sjölund, J.; Schön, T.B. Image restoration with mean-reverting stochastic differential equations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Gustafsson, F.K.; Zhao, Z.; Sjölund, J.; Schön, T.B. Controlling vision-language models for universal image restoration. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Pu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. A Comparative Study of Image Restoration Networks for General Backbone Network Design. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Li, J.; Dai, T.; Ouyang, Z.; Ren, X.; Xia, S.T. Mambair: A simple baseline for image restoration with state-space model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 222–241. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Guo, Y.; Zha, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Dai, T.; Xia, S.T.; Li, Y. Mambairv2: Attentive state space restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 28124–28133. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.