Abstract

Interesting new correlations and unidirectional properties of two bosonic modes under the influence of the environment appear when the modes are mutually coupled through the simultaneously applied linear mode-hopping and nonlinear squeezing interactions. Under such double coupling, it is found that while the Hamiltonian of the system is clearly Hermitian, the dynamics of the quadrature components of the field operators can be attributed to the non-Hermicity of the system. This manifests through an asymmetric coupling between the quadrature components, which then leads to a variety of remarkable features. In particular, we identify how the emerging exceptional point controls the conversion of thermal states of the modes into single-mode classically or quantum-squeezed states. Furthermore, for reservoirs in squeezed states, we find that the two-photon correlations present in these reservoirs are responsible for unidirectional flow of populations and correlations among the modes and the flow can be controlled by appropriate tuning of the mutual orientation of the squeezed noise ellipses. In the course of analyzing these effects, we find that the flow of the population creates the first-order coherence between the modes which, on the other hand, rules out an enhancement of the two photon correlations responsible for entanglement between the modes. These results suggest new alternatives for the creation of single-mode squeezed fields and the potential applications for the controlled unidirectional transfer of population and correlations in bosonic chains.

1. Introduction

It has been demonstrated in recent years that unconventional properties of non-Hermitian parity-time —symmetric systems such as exceptional points and nonreciprocity [1,2,3,4,5,6]—are not restricted to the time reversal systems [7,8,9,10,11,12], but can be obtained in quantum systems with a Hermitian Hamiltonian by interfering linear (excitation-preserving) and nonlinear two-mode interactions [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Subsequently, similar approaches have been studied, including the simultaneous application of linear and dissipative interactions [22,23] or creation of two coupling processes through engineering collective atomic systems [24,25]. The simultaneous existence of two coupling processes between quantum systems has been experimentally realized among optomechanical cavities [20,26] and in superconducting circuits [27,28].

To date, most of the treatments of the dynamics of doubly coupled modes have either been concerned with entanglement dynamics [21,29,30], quantum sensing [31,32], or topological phases [33,34,35,36,37]. Here, we consider a system composed of two Gaussian bosonic modes and concentrate on their fluctuation and correlation properties for features indicative of the simultaneous presence of the linear and nonlinear coupling processes. The two-mode system provides the simplest example of the effects generated by the double coupling. In particular, we investigate how the coupling influences the fluctuations, populations, and correlation properties of the modes. The treatment includes the dissipation of the modes to local thermal as well as squeezed reservoirs, which, as we will see, can have a significant effect on the fluctuation and correlation properties of the modes.

Modes interacting with local thermal or squeezed reservoirs will be sensitive to the number of photons and, in the case of squeezed reservoirs, also to the correlations present in the reservoirs, and in general will evolve in a phase-sensitive fashion to a stationary state that will reflect such correlations. A squeezed reservoir is characterized by the mean photon number n and by the phase-dependent two-photon correlations m, which range from zero to . Values of the correlation in the range correspond to a quantum squeezed reservoir while values of the correlation in the range correspond to a classically squeezed reservoir, and correspond to a thermal reservoir [38,39]. The presence of the correlations m leads to a reduction in the fluctuations in one quadrature of the modes.

It is well known that when only linear coupling is applied between two modes, it cannot create any correlations between noisy Gaussian modes [40]. On the other hand, when nonlinear coupling is applied, it can create two-photon correlations between the modes, which are necessary for entanglement, but the correlated modes are left mutually incoherent [41,42,43,44,45,46]. Moreover, the modes are strongly amplified in both populations and fluctuations such that the modes are found in a highly fluctuating thermal state [47,48,49].

In this paper, we demonstrate that when both linear and nonlinear interactions are simultaneously applied, the fluctuation and correlation properties of the modes are significantly different. Analytical expressions are obtained for steady state variances of the quadrature components of the mode operators and for correlation functions, which show that, relative to the mutual coupling strengths of the two interactions, an exceptional point emerges which is characteristic of non-Hermitian systems. To put it another way, our results demonstrate that in the Hermitian quantum system composed of simultaneously linearly and nonlinearly coupled modes, one can construct non-Hermitian dynamics, which can lead to nonreciprocal (one directional) influences of the modes on each other. It also creates an exceptional point which separates two distinctive parameter regimes, an exponential amplification regime and an oscillatory regime. In these two regimes, the fluctuation properties of the modes are found to be differently altered, even to the point of turning the fluctuations from thermal to quantum squeezed fluctuations. Under suitable conditions, the double coupling can establish the nonresiprocal transfer of the population and correlations between the modes.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the Hamiltonian of doubly coupled bosonic modes and provide a description of the independent external reservoirs to which the modes are dumped. Then, we derive the quantum Langevin equations for the quadrature components of the field operators and discuss their nonresiprocal coupling properties. In Section 3, we provide general solutions for the time-dependent quadrature operators which exhibit exceptional point-separating two-parameter regimes, exponential amplification, and oscillatory regimes. In Section 4, we specialize to the exponential amplification regime and apply the solutions to obtain analytic stationary expressions of physical quantities of interest as the variances of the quadrature operators, the populations of the modes, and single- and two-mode correlation functions, and to investigate their dependence on the noise properties of thermal and squeezed reservoirs. Analytic expressions of these physical quantities in the oscillatory regime are presented and extensively discussed in Section 5. Differences and similarities among the results obtained in those two regimes are also examined. Finally, a brief discussion of the results and conclusions is provided in Section 6.

2. Doubly Coupled Bosonic Modes

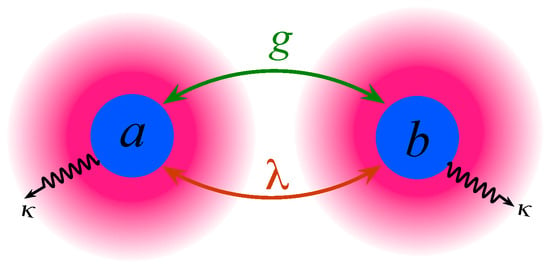

The system under study consists of two frequency degenerate radiation modes described by bosonic creation (annihilation) operators, and , respectively. The modes are directly coupled to each other through the presence of two different types of interaction processes, the linear optical photon exchange (beamsplitter type) and nonlinear two-photon (two-mode squeezing) interaction processes. In addition, both modes are damped with the rate by coupling to local (independent) reservoirs, which will be considered thermal or squeezed reservoirs; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the considered system composed of two modes a and b coupled to each other through linear and nonlinear interactions. The modes are dumped with rate through interaction with local broadband reservoirs.

The interaction between the modes is determined by the Hamiltonian

where and g are real parameters determining the strength and the linear and nonlinear coupling between the modes, respectively, and is the phase of the i-the mode. The simultaneous action of the two interactions will couple the modes and will provide the systematic evolution of the modes due to the mutual interaction. Without loss of generality we will assume that the phase of the mode a is fixed at , while the phase of the mode b can be varied so that will play the role of the relative phase between squeezed reservoirs.

It has been demonstrated that the presence of the nonlinear two-photon interaction process in the Hamiltonian interaction (1) leads to nonreciprocal and non-Hermitian behaviour in the system [14,18,19,20,21]. To see this, we introduce Hermitian operators representing the amplitudes of two quadrature phase components of the fields:

and find that the quadrature components and , satisfy a set of coupled Heisenberg equations of motion:

where and

is the evolution matrix.

It is easily verified that the matrix is non-Hermitian when . Thus, the presence of the nonlinear process in the interaction between the modes induces non-Hermitian dynamics in the system even though the Hamiltonian is Hermitian.

Assuming further that the modes interact with local reservoirs, which results in damping of the modes with a rate and quantum noise of the reservoir incident on the modes, the evolution of the quadrature components obeys the quantum Langevin equation:

where , and

We first observe that inside each pair of equations, quadratures are coupled to each other in an asymmetric manner, such that the X quadratures are coupled to Y quadratures with strength , whereas Y quadratures are coupled to X with strength . For , we have complete coupling asymmetry, so that the evolution of the X quadratures is decoupled from the evolution of the Y quadratures. In this case, there is a unidirectional coupling between the quadratures. Thus, we expect chiral propagation of fluctuations and correlations from Y quadratures to X quadratures of the other mode.

The dynamics of the quadrature operators are influenced by the quantum noise operators and of the input modes to which the modes a and b are coupled. They obey Gaussian statistics and are delta correlated in time. We assume that the input noise operators represent two independent reservoirs, which could be in squeezed vacuum states. Typical sources of a squeezed vacuum field are degenerate parametric oscillators (DPO) operating below threshold, whose fields fill the input modes, resulting in the following input correlation functions [50,51,52,53,54,55]:

where , in which is the damping rate of the DPO cavity and is its amplification amplitude, proportional to the amplitude of a classical field pumping the DPO cavity. Parameters and determine the bandwidth of the squeezed reservoirs.

In the case when and are much larger than , corresponding to broadband reservoirs, the exponentials appearing in Equation (7) can be approximated by functions and then the correlation functions (7) take the following form:

where

from which we see that, by varying parameters and of the parametric oscillator, one can produce a squeezed vacuum field with the desired values of n and m. It is convenient to present the results in terms of n and m rather than and , since n describes the average number of thermal photons and m describes the degree of two-photon correlations between the photons contained in the reservoirs. It can be seen from Equation (8) that the presence of the two-photon correlations m leads to an asymmetric distribution of noise between the quadratures. We assume that the phase of the squeezed reservoir coupled to the mode a is fixed at zero, whereas the phase of the squeezed reservoir coupled to the mode b can be varied. Parameters n and m are related to each other such that corresponds to a classically squeezed field, whereas corresponds to a quantum squeezed field [38,39].

3. Dynamics of the Doubly Coupled Bosonic Modes

To proceed with the solution of the set of differential Equations (5), it is convenient to introduce the Laplace transforms of the following quadratures:

whose application converts the equations into a set of algebraic equations. The set of the algebraic equations can be readily solved for the transformed quadratures:

in which we introduced the following abbreviations:

and and are the roots of the quadratic equation

The roots can be easily computed to obtain the following:

It is clearly seen from Equation (14) that the roots are strongly dependent on the relationship between the coupling constants g and . We distinguish two parameter regimes in which, depending on whether or , the factor can be either the real or the complex parameter. A threshold at which the roots change character is set for , which corresponds to the exceptional point. For , the roots are real:

while for , the roots are complex:

Thus, there are two distinct regimes in which the solutions have different characters. We will call regime an exponential amplification regime, and an oscillatory regime.

For each of the regimes, we will investigate the properties of the steady state variances of the quadrature operators, the populations of the modes, and , single-mode two-photon correlations, and , which we will call “local two-photon correlations”, and two-mode two-photon correlations [56,57], which we will call “global two-photon correlations”. Apart from the global two-photon correlations we will also consider the single-photon two-mode correlations , which are known to carry information about the coherence properties of the modes [40]. This restricted class of correlation functions results from the fact that the dynamics of the modes considered are Gaussian. Note that the local two-photon correlations are responsible for the squeezing of the single-mode fluctuations, whereas the global two-photon correlations are necessary for entanglement [58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

Through inverse Laplace transformation and application of the Cauchy residue theorem, we then have from Equation (7), with the help of Equation (15), that in the case of , the time evolution of the quadrature operators is given by

where .

Similarly, the inverse Laplace transformation of Equation (7) with the complex roots (16) yields to

where . In this case, the quadrature evolves in an oscillatory manner.

The dynamics of the quadrature operators are influenced by the quadratures and of the input modes, whose statistics are shown by the statistics of the reservoirs to which the modes are coupled. The effect of the statistics of the reservoirs will be evident in the fluctuation and correlation properties of the modes.

4. Exponential Amplification Regime,

We begin our discussion of the correlation and fluctuation properties of the modes by considering the exponential regime .

Let us first consider the average number of photons of the modes, i.e., populations of the modes. Since

and we have solutions for the time evolution of the quadrature operators, the populations can be evaluated from

where and are variances of the quadrature operators of the modes. Thus, an evaluation of the populations of the modes requires calculations of the variances of the quadrature operators of the modes.

The Gaussian character of the system enables the quadrature variances to be readily calculated. With the use of Equations (17) and (5), we find that the variances of the quadrature components of the mutually doubly coupled modes are

where all system parameters have been normalised by the damping rate : , , , and the angle is defined through the relation , .

Since , we see that expressing the solutions (21) in terms of the angle constraints to values (threshold occurs at ) at which the solutions are stable. From this constraint, we also see that and are constrained to . In what follows, we will consider the population and correlation properties of the system in that constrained range of the parameters. Note that there is no constraint on n, i.e., the solutions (21) are valid for . For clarity of expression, we will drop the bar on , and with the understanding that we are dealing with dimensionless rescaled quantities.

Equation (21) shows that the double coupling between the modes enhances the variances, indicating enhancement of the fluctuations in the modes. However, the variances are unequally enhanced so that the variances of the X quadratures are less enhanced than the variances of the Y quadratures. This is easily understood since, according to Equation (4), there is an asymmetry in the coupling between the X and Y quadratures, leading to an unbalanced transfer of the fluctuations between the quadratures.

Once the variances have been determined, it is only a matter of the substitution of Equation (21) in Equation (20) to derive explicit expressions for the steady state populations. Thus, we obtain the following expressions for the populations:

and

The first terms on the right-hand sides of Equations (22) and (23) represent the population of the modes in the absence of direct coupling between the modes. The second terms on the right-hand sides are due to the coupling between the modes. Of particular interest to us is the dependence of the populations on the term , which accounts for double coupling between the modes.

It is quite evident from Equations (22) and (23) that the populations are amplified by the mutual couplings and the major role the amplification plays in the nonlinear coupling process. Since , this means that the amplifier is operating below the threshold for the stable steady-state solutions [47,48,51].

Note that the manner in which the populations are amplified by the couplings is different for and , and the populations are very dependent on the nature of the reservoirs. Perhaps the most significant is the insensitivity of the population of the mode b to the phase of the squeezed reservoir to which the mode is coupled. As it is seen from Equation (22) the phase sensitivity is transferred to the mode a. Thus, a variation of the phase of the squeezed reservoir coupled to the mode b will modify the population of the other mode.

The squeezed reservoirs provide the mechanism for controlled amplification of the mode a so that the population of the mode can vary with the phase in such a way that it could be possible to cease the amplification process. Specifically, at the exceptional point, when with and in the strong squeezing limit , Equation (22) takes a simple form:

This result directly shows that, for strongly squeezed reservoirs, the population is extremely phase-sensitive at the exceptional point, and the choice of phase leads to the ceasing of the amplification process.

It is worth noting that the phenomenon of ceasing the amplification process of mode a, derived using , is unique to quantum squeezing in that it is not possible to cease the the amplification process when , i.e., the modes interact with classically squeezed fields of the reservoirs. In addition, this phase-dependent amplification of the mode offers us new control over nonlinear effects in the system of coupled modes.

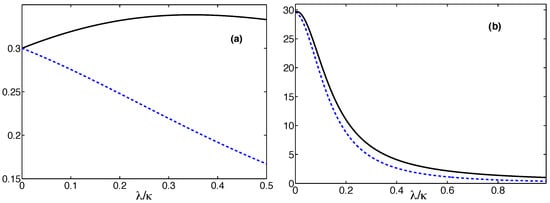

Figure 2 shows the variation in the population of the mode a with the strength of the linear coupling from the purely nonlinear coupling to the exceptional point for two limiting cases of the phase and and two different values of the nonlinear coupling strength g. Note that the limit corresponds to approaching the instability threshold in the nonlinear amplifying interaction [47,48,51]. For g, away from the instability threshold the population varies with the phase and the linear coupling such that, for , it is further amplified and de-amplified for . For g close to the instability threshold, the population exhibits a weak dependence on the phase, rapidly degrades with the increasing strength of the linear interactions and returns to its initial value as approaches the exceptional point .

Figure 2.

Variation in the population of the mode a with the strength of the linear coupling starting from the purely nonlinear coupling to the exceptional point , for , and two different values of g: (a) and (b) . The solid black line is for ; the dashed blue line is for .

4.1. Two-Photon Correlations Inside the Modes

We now turn to the calculation of the single-mode two-photon correlation functions, which are known to give rise to squeezing of the fluctuations in the quadrature operators. To evaluate the correlation functions, we use Equation (19) and find

It is seen that the two-photon correlation functions are not only related to the variances but also to the correlation functions , which are readily evaluated with the use of Equation (17) and are given by

and

Then, the two-photon correlation functions obtained from Equation (25) are

The contribution of the first terms on the right-hand side of Equation (28) obviously correspond to correlations transferred to the modes in the absence of the inter-mode couplings. The second terms correspond to the creation of the correlations inside the modes by the inter-mode couplings. It is seen that the effect of the presence of the double coupling between the modes is to create phase-insensitive and phase-sensitive contributions to the correlations.

The phase-insensitive contributions correspond to those created when the reservoirs are in thermal states , and then the correlations are

This shows that nonzero two-photon correlations arise solely from the presence of the double coupling between the modes. Consequently, uncoupled modes, being in thermal states, are turned by the double coupling to squeezed states. This is clearly seen when one considers the variances of the quadrature components, Equation (21), which in the case of reduce to

Evidently, when , indicating that the modes are in squeezed states with the variances of X quadratures reduced at the expense of the increased variances of Y quadratures. Further inside into the variances reveals that decreases as is increasing and a maximum squeezing, i.e., the minimum value of , is reached for , i.e., at the exceptional point, in which case . Since , it follows that the maximum reduction in the variances (fluctuations) corresponds to maximally classically squeezed fields.

Conditions for squeezed fluctuations in the modes can be more conveniently examined by investigating the degrees of the single-mode two-photon correlations defined as

from which it is clearly seen that and vary from to infinity. Negative values of , with the limiting value , indicate a classically squeezed field, whereas positive values of indicate a quantum-squeezed field, and the larger the positive value the greater the quantum squeezing.

In order to see this more explicitly, it is helpful to introduce normally ordered variances , because the condition for quantum squeezing then has the simple form [38,39,50,52,53,54]. In terms of the degrees of the correlations, the normally ordered variances are of the following forms:

It is clearly seen that in the case of a classically squeezed field where , all the normally ordered variances are nonnegative. However, for the normally ordered variance is negative and, depending on the phase, either or can be negative, indicating that the modes are in quantum-squeezed states.

When we specify the thermal reservoirs interacting with the modes, we obtain

which is always negative. Thus, fluctuations in both modes cannot be reduced below the vacuum limit of . Therefore, both modes display classically squeezed fluctuations.

Further, we would like to point out that Equation (29) provides an interesting example of an unexpected result: interactions applied between the modes create correlations inside the modes. Such an effect is absent when only one type of interaction, linear or nonlinear, is applied between the modes.

The phase-sensitive contributions to the correlations (28) are due to the correlations m existing in squeezed reservoirs. A close look at the correlations, as in Equation (28), reveals that the two-photon correlations inside the modes are created by the linear and nonlinear coupling processes from the correlations existing in the reservoirs under completely different conditions. It can be seen in Equation (28) that for , the phase-sensitive contributions are due to the linear coupling process , whereas for , the contribution to the correlations is achieved through the nonlinear process .

Let us examine how the correlations behave at the exceptional point, when . In this case, we obtain from Equation (28) that

from which it is apparent that the correlations contained in the mode a are sensitive to the phase of the reservoir to which mode b is coupled. Remembering that in the large quantum-squeezing limit, , we see that the process of the enhancement of the correlations inside the mode a can be significantly reduced and ultimately ceased if one chooses . Thus, for strongly squeezed reservoirs, the same dramatic phase dependence exhibited by the population of mode a also appears in the single-mode two-photon correlations.

4.2. Correlations Between the Modes

Now we turn our attention to the two-mode correlations that could exist between the modes. There could be one-photon and two-photon correlations between the two modes, which are determined by the correlation functions and , respectively. From Equation (19), we find that the correlations can be evaluated by calculating the correlations between quadratures of different modes

and

The correlation functions can be evaluated using Equation (17) with the help of Equation (5), and their explicit steady-state expressions are given in the Appendix A. Hence, by inserting Equations (A1) and (A2) into Equations (35) and (36), we obtain

and

From Equation (37), we see that the interaction of the modes with squeezed reservoirs is essential for generating the first-order correlations between the modes, such that it is not possible to have when the modes interact with thermal reservoirs. In addition, the correlations are specifically dependent on the relative phase of the squeezed reservoirs. A comparison of Equations (37) and (38) shows the difference that phase shows between the one-photon and two-photon correlations. Namely, the choice of phase results in with the simultaneous enhancement of the two-photon correlations . Conversely, the choice of phase results in maximal and minimal. Thus, the first-order coherence between the modes can be destroyed or preserved depending on the relative phase of the reservoirs.

In addition, Equations (37) and (38) reveal that the one-photon correlations between the modes are created solely by the nonlinear coupling process from the two-photon correlations existing in the squeezed reservoirs. However, the two-photon correlations between the modes are created by both linear and nonlinear coupling processes. The effect of the nonlinear coupling is to create a phase-insensitive contribution from the reservoirs’ thermal noise , whereas the phase-sensitive contribution is created by the linear coupling process from the two-photon correlations existing in the squeezed reservoirs. Note that becomes phase-insensitive when phase .

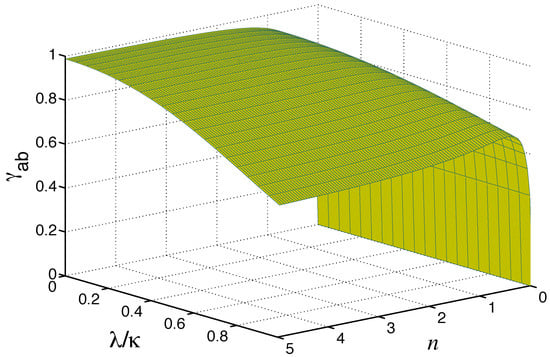

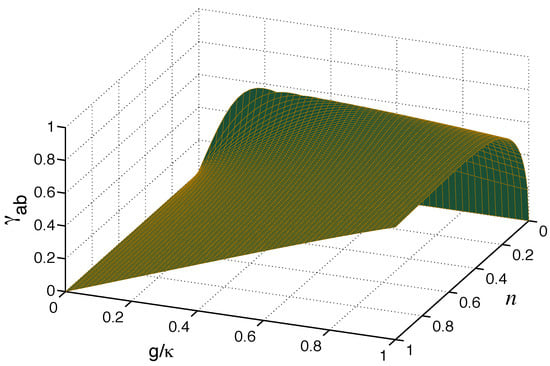

As can be nonzero, it follows that the modes can be coherent to the first-order, and we can determine the degree of the first-order coherence by considering the quantity , which lies between 0 for mutually incoherent and 1, for mutually perfectly coherent fields. For the case considered here, the explicit analytical form of can be found using Equations (22), (23) and (37). With the choice of phase , at which is maximal, we obtain

Figure 3 shows the variation in the coherence function with n and for . It is seen that increases with n, such that for and the purely nonlinear coupling , the degree of coherence is close to unity, indicating that the modes are almost perfectly coherent. The coherence decreases with an increasing linear coupling such that, at the exceptional point , the modes are coherent.

Figure 3.

Degree of the first-order coherence plotted as a function n and starting from the purely nonlinear coupling to the exceptional point , for , , and .

In order to distinguish between the classical and quantum two-photon correlations present between the modes it is useful to define the degree of mutual two-photon correlations by introducing the quantity , which lies between 0 and ∞.

However, there is a threshold value of at which one can distinguish between the cases of classically and quantum correlated (entangled) modes. In the literature, there are several different criteria for the detection of entanglement applicable to Gaussian systems [58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. For example, the DGCZ [60] criterion for the entanglement of two equally populated modes is as follows:

which clearly shows that the modes are entangled when . Another often-used criterion for a quantum (entangle) field involves the Cauchy–Schwartz inequality [40,55], which for two classically correlated Gaussian modes take the following form:

The inequality is violated for quantum correlated modes, and in the case of , the inequality is violated when

Thus, there is a threshold value of which distinguishes between mutually classically and quantum correlated fields. Namely, for classically correlated fields, can be no larger than 1, and can be achieved only for quantum correlated fields.

When the modes interact with squeezed reservoirs, we find that the choices of phases and require significantly different conditions for to be larger than one. With the help of Equations (22), (23) and (38), we find that

when , and

when . Since in the exponential amplification regime, the condition for stable steady-state solutions [40,47,48,51] requires , we see from Equation (42) that in the case of the ordinary vacuum , this ensures that is always larger than one. However, for the thermal or squeezed vacuum, where , the first term in the numerator of Equation (42) may not be large enough to enforce .

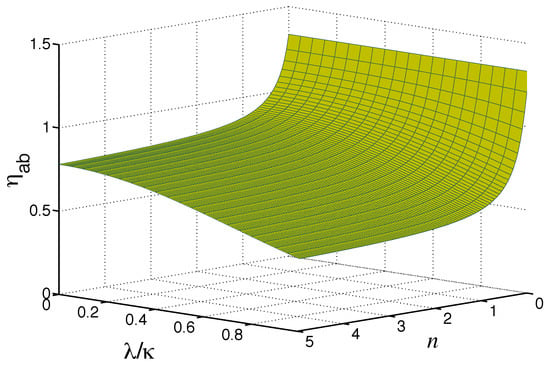

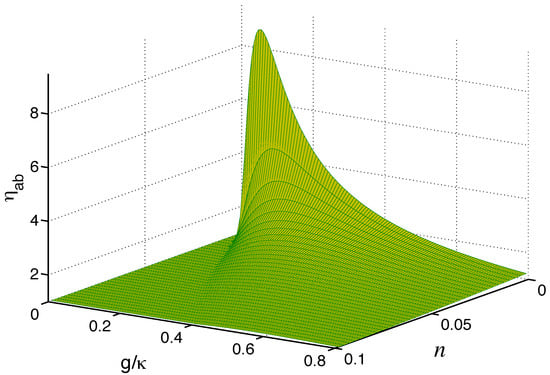

To search for the limits imposed by n on being larger than one, we plot, in Figure 4, the degree of two-photon correlations as a function of and as a function of n for and . The largest value of occurs for at which , degrades with an increasing n, and turns into values smaller than one for . The linear interaction has the effect of further decreasing the correlations.

Figure 4.

Degree of the mutual two-photon correlations plotted as a function n and , starting from the purely nonlinear coupling to the exceptional point , for , , and .

A comparison of Figure 3 and Figure 4 immediately shows the impact that the number of thermal photons has on the degree of coherence and on the degree of two-photon correlations . As is clearly seen, is large in the region of , in which is small, while for the values of n where is large, is smaller than one and even tends towards zero. For , the degree of coherence can, in principle, approach one , the perfect coherence. Thus, unlike the degree of the first-order correlation, which approaches maximal values for large n, the degree of the two-photon correlations has maximal values for small n. In addition, the perfect coherence can be achieved only if the reservoirs are in in quantum squeezed states, . For maximally classically squeezed reservoirs, , the degree of coherence is significantly less than one.

5. Oscillatory Regime

We now turn to consider the case of , in which the quadrature components exhibit oscillatory behaviour and, as in the previous section, we study the fluctuation properties of the modes, their populations, and single- and two-mode correlations. The starting point of our calculations is Equation (18), the solutions for the time evolution of the quadrature components for , and we will first consider the steady-state properties of the variances of the quadrature components.

5.1. Fluctuation Properties of the Modes

Following the same procedure as described in the preceding section, if we evaluate the variances of the quadrature components according to Equation (18), we arrive at the following expressions:

where . These results are in marked contrast to those found in the exponential region given by Equation (21). In particular, we can immediately see that outside the exceptional point the variances of the X quadratures are reduced while the variances of the Y quadratures are enhanced by the double coupling.

The first important fact we can derive from Equation (44) is that even when the modes interact with thermal reservoirs, the variances of the X quadratures can be reduced below their vacuum value of , which indicates that the modes can be found in quantum-squeezed states. To show this more explicitly, we set in Equation (44) and find that

Clearly, the fluctuations in quadratures can be reduced to below if . This implies that outside the exceptional point, the fields of both modes can display quantum-squeezed fluctuations.

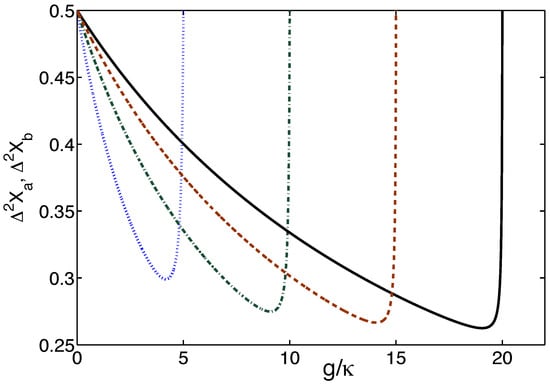

In Figure 5, we plot the variances of the X quadratures as a function of the scaled nonlinear coupling strength for and several different values of . For the purely linear coupling the variances are at the vacuum level of . The presence of the nonlinear coupling leads to a reduction in the variances to below , indicating that the modes are in quantum-squeezed states. The maximum squeezing occurs for g in the vicinity of the exceptional point. It is seen that approaching the exceptional point causes the cessation of quantum squeezing. The largest reduction in the variances is achieved for , in which case , so that we may speak of a reduction in the fluctuations below the quantum level. Again, we point out that this result is in sharp contrast with the exponential case of , Equation (30), where the variances were reduced only to the vacuum level.

Figure 5.

Variation in the variances of the X quadratures with , starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for and several different values of : (blue dotted line); (green dashed–dotted line); (red dashed line); (black solid line).

We can readily adapt the expressions (44) for the variances to calculate the populations of the modes. Upon making use of variances (44) in Equation (20), we obtain

and

Apart from the appearance of in place of , Equations (46) and (47) are formally identical to the corresponding results found in Section 4 for the exponential case . As for the case , only the population of mode a depends on the phase such that, for , the modes are equally populated and by varying the phase, it is possible to vary the population such that the effect of amplification of the population ultimately ceases to occur.

5.2. Two-Photon Correlations Inside the Modes

We now consider the single-mode two-photon correlations. Using the variances (44) in Equation (25), we find

Further insight into the correlation properties of the modes is gained by considering the degrees of the correlations. If we restrict ourselves to the case where the doubly coupled modes interact with local thermal reservoirs, we obtain that the degrees of the correlations are

Apparently, the degrees of the correlations can have positive values, which is quite different from the exponential amplification case of , where and were always negative. It is particularly interesting to note that in the case of the ordinary vacuum state of the reservoirs, and are always positive. Therefore, the fluctuations in the modes can be reduced below the vacuum limit so that the modes can display quantum-squeezed fluctuations. The effect of thermal photons n is to diminish the correlations and, eventually, to turn and into negative values. In other words, thermal fluctuations can turn the fluctuations in the modes from quantum to classically squeezed fluctuations.

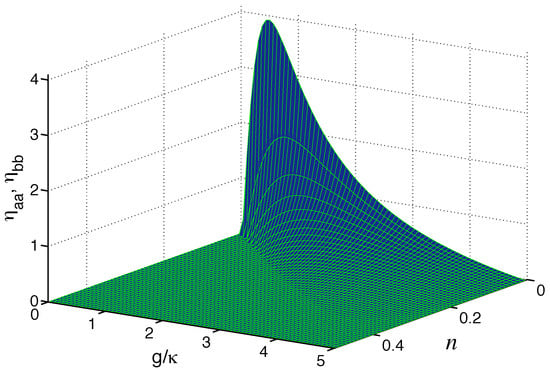

The feature of these correlations are easily seen in Figure 6, which shows and , as given in Equation (49) as a function of and n for . For the purely linear coupling the degrees of the correlations are negative. When , positive values emerge for the degrees, indicating the presence of quantum correlations inside the modes. The largest values of and occur for small g and n, and with an increasing g, the threshold for and to be positive shifts towards a larger n.

Figure 6.

Variation in and with n and , starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for and the modes interacting with thermal reservoirs.

To continue the analysis of the two-photon correlations, we now assume that the modes interact with squeezed reservoirs. In this case, the degrees of the two-photon correlations depend on the phase , such that the choice of the phase results in equal degrees for both modes:

The absolute values appearing in the numerator of this equation involve a difference between the two-photon correlations existing in the squeezed reservoirs and the correlations generated by the double coupling between the modes.

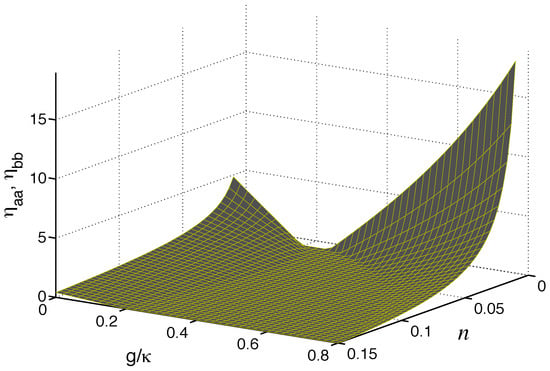

In Figure 7, we plot and as a function of and n for and quantum-squeezed reservoirs with . We can distinguish two separate ranges of the parameters for which the degrees are positive. For the first, occurring for , the quantum correlations are those transferred to the modes due to their interaction with the reservoirs. For the purely linear coupling , the degrees of the correlations are positive. For , the degrees decrease with an increasing g and ultimately cease at . As g increases further, quantum correlations appear again, showing that the double coupling can generate quantum correlations inside the modes independent of the state of the reservoirs.

Figure 7.

Variation in and with n and starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for and the modes interacting with quantum-squeezed reservoirs, .

The choice of phase leads to widely different behaviour among the degrees of the correlations of the modes, such that

and

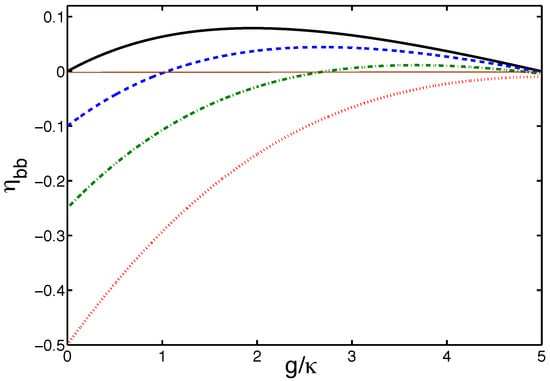

Since , it is clearly seen from the structure of the numerator in Equation (52) that is always positive. Hence, the mode b will exhibit quantum-squeezed fluctuations even if the reservoirs are in classically squeezed states. This is illustrated in Figure 8, where we plot as a function of g for and several different values of . For the purely linear coupling the degree of correlations is always negative, indicating classically squeezed correlations present in the mode. For , is negative over the entire range of g but for larger m, quantum correlations appear in the restricted range of large g. For still-larger m, quantum correlations appear in the less restricted range of g and for quantum correlations occur over the entire range of g.

Figure 8.

Variation in and with starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for , and several different values of m: (red dotted line); (green dashed–dotted line); (blue dashed line); and (black solid line).

5.3. Correlations Between the Modes

Finally, we consider the properties of the two-mode correlations which, in the case of , follow from Equations (35) and (36) with the correlation functions involving quadrature operators of the different modes given by Equations (A3) and (A4). Thus, we find that

and

From the form of the correlations, we can see that the one-photon correlation function is different from zero only for phase choices between 0 and and attains its maximal values for phase , at which point the linear and nonlinear processes equally contribute to the two-photon correlation function. This result is in marked contrast to that found in the case of , where attained a maximal value at . At that phase, the two-photon correlation function was independent of the correlations m.

A better insight into the correlations is obtained by considering the degrees of the correlations. Consider first the degree of the first-order coherence . Using Equation (53) with the populations given in Equations (46) and (47), we readily find that for , the degree of coherence is

The expression is plotted in Figure 9 for and . The degree of the first-order coherence increases with g and attains maximal values no larger than . This result is significantly different from that obtained in the exponential amplification regime , where the degree of the first-order coherence can be as large as 1.

Figure 9.

Degree of the first-order coherence plotted as a function of n and starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for and .

To examine the properties of the two-mode two-photon correlations, we use Equation (54), which, together with the populations given by Equations (46) and (47), obtains

for the choice of phase , and

for the choice of phase .

It is clear from Equation (56) that for , the minimum requirement for to be larger than one is that g should be lower than one. Since in the oscillatory regime there are no limits imposed on g, we have that in the case of the ordinary vacuum , the requirement is necessary and sufficient. However, for the thermal or squeezed vacuum, it is necessary but not sufficient. For , the first term in the numerator of Equation (56) may not be large enough to enforce .

To search for limits imposed by n on being larger than one, we plot, in Figure 10, the degree of two-photon correlations as a function of g and as a function of n for and . For the purely linear coupling , the degree of the correlations is equal to one, but increases to values greater than 1 with an increasing g. For and small n, the correlations attain maximal values, indicating that at the parameter regime, strong quantum two-photon correlations exist between the modes.

Figure 10.

Degree of the two-mode two-photon correlations plotted as a function of n and , starting from the purely linear coupling to the exceptional point , for and maximally classically squeezed reservoirs, .

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the fluctuation and correlation properties of two bosonic modes mutually coupled through a linear photon exchange and nonlinear parametric type processes. This Hermitian quantum system is known to exhibit non-Hermitian dynamics, which can lead to nonreciprocal (one directional) influences of the modes on each other [19,21]. In addition, it results in the appearance of an exceptional point separating two parameter regimes, exponential amplification and oscillatory regimes. The fluctuation and correlation properties of the modes were investigated by evaluating the stationary expressions for the variances of the quadrature components of the field operators, populations of the modes, and single- and two-mode correlations. We assumed that apart from the presence of the double coupling, the modes are in contact (interact) with local thermal or squeezed reservoirs, and showed that the creation of the correlations by the nonreciprocal coupling is strongly influenced by the noise properties of the reservoirs. The differences in the fluctuations and correlations for these two regimes were studied in detail. In particular, for the exponential amplification regime, the nonreciprocal coupling tends to convert thermal fluctuations in independent modes that are in contact with thermal reservoirs into classically squeezed fluctuations. In the oscillatory regime, however, thermal fluctuations in the modes can be turned by the nonreciprocal coupling into quantum-squeezed fluctuations. Apart from the fluctuations, the nonreciprocal coupling can have a significant effect on the amplification of the population of the modes. We showed that when the modes interact with strongly squeezed reservoirs, the amplification of the population of one of the modes can be controlled by varying the phase of the reservoir that interacts with the other mode, and can even be completely ceased. We also discussed the conditions under which the modes could be coherent and simultaneously entangled. We found that the coherence and entanglement exclude each other, such that strongly coherent modes exhibit classical rather than quantum two-photon correlations and, vice versa, strongly two-photon-correlated modes behave as being mutually incoherent.

Funding

This research was funded by the Minister of Science under the “Regional Excellence Initiative” program, Project No. RID/SP/0050/2024/1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In this appendix, we provide analytic expressions of the stationary correlation functions of quadrature operators of the same and different modes, which are required to evaluate single-mode two-photon correlation functions and two-mode one-photon and two-photon correlation functions.

References

- Heiss, W.D. The physics of exceptional points. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2012, 45, 444016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, M.A.; Alu, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 2019, 363, 7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdermir, S.K.; Rotter, S.; Nori, F.; Yang, L. Parity–time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipov, I.I.; Miranowicz, A.; Minganti, F.; Nori, F. Quantum and semiclassical exceptional points of a linear system of coupled cavities with losses and gain within the Scully-Lamb laser theory. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 013812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholtz, E.J.; Budich, J.C.; Kunst, F.K. Exceptional topology of non-hermitian systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Fang, C.; Ma, G. Non-hermitian topology and exceptional-point geometries. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2022, 4, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ganainy, R.; Makris, K.G.; Khajavikhan, M.; Musslimani, Z.H.; Rotter, S.; Christodoulides, D.N. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perina, J.J.; Miranowicz, A.; Kalaga, J.K.; Leoński, W. Unavoidability of nonclassicality loss in PT-symmetric systems. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 108, 033512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, J.; Zheng, C. Theoretical investigation of dynamics and concurrence of entangled PT and anti-PT symmetric polarized photons. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, C. Non-Hermitian quantum Renyi entropy dynamics in anyonic-PT symmetric systems. Symmetry 2024, 16, 584. [Google Scholar]

- Perina, J.J.; Bartkiewicz, K.; Chimczak, G.; Kowalewska-Kudlaszyk, A.; Miranowicz, A.; Kalaga, J.K.; Leoński, W. Quantumness and its hierarchies in PT-symmetric down-conversion models. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 112, 043545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzanjeh, S.; Xuereb, A.; Alu, A.; Mann, S.A.; Nefedkin, N.; Peano, V.; Rabl, P. Nonreciprocity in quantum technology. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.03945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malz, D.; Toth, L.D.; Bernier, N.R. Quantum-limited directional amplifiers with optomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 023601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, A.; Pereg-Barnea, T.; Clerk, A.A. Phase-dependent chiral transport and effective non-Hermitian dynamics in a bosonic Kitaev-Majorana chain. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 041031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Clerk, A.A. Non-Hermitian dynamics without dissipation in quantum systems. Phys. Rev. 2019, 99, 063834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, V.P.; Cobanera, E.; Viola, L. Deconstructing effective non-Hermitian dynamics in quadratic bosonic Hamiltonians. New J. Phys. 2020, 22, 083004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, V.P.; Cobanera, E.; Viola, L. Topology by dissipation: Majorana bosons in metastable quadratic Markovian dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 245701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Piero, J.; Slim, J.J.; Verhagen, E. Non-Hermitian chiral phononics through optomechanically induced squeezing. Nature 2022, 606, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjura, C.C.; Slim, J.J.; del Pino, J.; Brunelli, M.; Verhagen, E.; Nunnenkamp, A. Quadrature nonreciprocity: Unidirectional bosonic transmission without breaking time-reversal symmetry. Nat. Commun. 2023, 7, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Slim, J.J.; Wanjura, C.C.; Brunelli, M.; del Pino, J.; Nunnenkamp, A.; Verhagen, E. Optomechanical realization of the bosonic Kitaev chain. Nature 2024, 627, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Tian, M.; Kong, N.; Fadel, M.; Huang, X.; He, Q. Exceptional-point-induced nonequilibrium entanglement dynamics in bosonic networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzanjeh, S.; Aquilina, M.; Xuereb, A. Manipulating the flow of thermal noise in quantum devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 060601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, B.; Mazurek, P.; Horodecki, P.; Barzanjeh, S. Nonreciprocal quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 210402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimer, F.; Estienne, B.; Parkins, A.S.; Carmichael, H.J. Proposed realization of the Dicke-model quantum phase transition in an optical cavity QED system. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 013804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, W.; Fernholz, T.; Jensen, K.; Madsen, L.S.; Krauter, H.; Muschik, C.; Polzik, E.S. Generation of two-mode squeezed and entangled light in a single temporal and spatial mode. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruesink, F.; Miri, M.A.; Alu, A.; Verhagen, E. Nonreciprocity and magnetic-free isolation based on optomechanical interactions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwa, K.M.; Hatridge, M.; Narla, A.; Shankar, S.; Frunzio, L.; Schoelkopf, R.J.; Devoret, M.H. Reconfigurable Josephson circulator/directional amplifier. Phys. Rev. X 2015, 5, 041020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lester, B.J.; Gao, Y.Y.; Jiang, L.; Schoelkopf, R.J.; Girvin, S.M. Engineering bilinear mode coupling in circuit QED: Theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 012314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, V.K.; Subrahmanyam, V. Quantum correlations and entanglement in a Kitaev-type spin chain. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 052303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, V.K.; Cayao, J. Entanglement dynamics in minimal Kitaev chains. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.17586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.; Clerk, A.A. Exponentially-enhanced quantum sensing with non-Hermitian lattice dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.W.; Zhang, C.; Du, S. Quantum squeezing and sensing with pseudo-anti-parity-time symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 173602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Hughes, T.L. Absence of topological insulator phases in non-Hermitian PT-symmetric Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 153101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzard, S.; Poli, C.; Schomerus, H. Topologically protected defect states in open photonic systems with non-Hermitian charge-conjugation and parity-time symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 200402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peano, V.; Houde, M.; Brendel, C.; Marquardt, F.; Clerk, A.A. Topological phase transitions and chiral inelastic transport induced by the squeezing of light. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Ashida, Y.; Kawabata, K.; Takasan, K.; Higashikawa, S.; Ueda, M. Topological phases of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 031079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjura, C.C.; Brunelli, M.; Nunnenkamp, A. Topological framework for directional amplification in driven-dissipative cavity arrays. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, P.D.; Ficek, Z. Quantum Squeezing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ficek, Z.; Wahiddin, M.R. Quantum Optics for Beginners; Pan Stanford: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, L.; Wolf, E. Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Monken, C.H.; Garuccio, A.; Branning, D.; Torgerson, J.R.; Narducci, F.; Mandel, L. Generating mutual coherence from incoherence with the help of a phase-conjugate mirror. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 53, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mandel, L. Anticoherence. Pure Appl. Opt. 1998, 7, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.H.; Li, G.X.; Ficek, Z. First-order coherence versus entanglement in a nanomechanical cavity. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 022327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, A.; Menzel, R.; Milonni, P. Complementarity in biphoton generation with stimulated or induced coherence. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 033834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, R.; Heuer, A.; Milonni, P. Entanglement, complementarity, and vacuum fields in spontaneous parametric down-conversion. Atoms 2019, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.H.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, K.K.; Yang, W.X.; Ficek, Z. Coherence and anticoherence induced by thermal fields. Entropy 2022, 24, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollow, B.R.; Glauber, R.J. Quantum theory of parametric amplification. I. Phys. Rev. 1967, 160, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollow, B.R.; Glauber, R.J. Quantum theory of parametric amplification. II. Phys. Rev. 1967, 160, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.M.; Knight, P.L. Thermofield analysis of squeezing and statistical mixtures in quantum optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1985, 2, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, D.F. Squeezed states of light. Nature 1983, 306, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, M.J.; Gardiner, C.W. Squeezing of intracavity and traveling-wave light fields produced in parametric amplification. Phys. Rev. A 1984, 30, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudon, R.; Knight, P.L. Squeezed light. J. Mod. Opt. 1987, 34, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, K.; Zubairy, M.S. Squeezed states of the radiation field. Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1990, 28, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, B.J.; Ficek, Z.; Swain, S. Atoms in squeezed light fields. J. Mod. Opt. 1999, 46, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.W.; Zoller, P. Quantum Noise; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, G.S. Anomalous coherence functions of the radiation fields. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 33, 11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahteenmaki, P.; Paraoanu, G.S.; Hassel, J.; Hakonen, P.J. Coherence and multimode correlations from vacuum fluctuations in a microwave superconducting cavity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states: Necessary and sufficient conditions. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 223, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R. Peres-Horodecki separability criterion for continuous variable systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Giedke, G.; Cirac, J.; Zoller, P. Inseparability criterion for continuous variable systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanneti, V.; Mancini, S.; Vitali, D.; Tombesi, P. Characterizing the entanglement of bipartite quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 67, 022320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobińska, M.; Wódkiewicz, K. Witnessing entanglement with second-order interference. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 032304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hillery, M.; Zubairy, M. Entanglement conditions for two-mode states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 050503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Datta, A. Quantum versus classical correlations in Gaussian states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.