Abstract

Pascal’s Triangle, renowned for its geometric elegance and profound applications across combinatorics, algebra, and probability, has fascinated mathematicians for centuries. While its origins can be traced to Chinese, Persian, and European mathematical traditions, the study of its higher-dimensional analogues remains notably underexplored. This paper offers a systematic and self-contained study of Pascal Pyramids and Pascal Simplexes with their proofs. It encompasses both classical results (such as multinomial identities) and novel contributions (including boundary and scaling properties), as well as fresh perspectives (such as graph-theoretic interpretations) that are rarely documented in the existing literature.

1. Introduction

Pascal’s Triangle is a geometric arrangement of binomial coefficients that has intrigued mathematicians for centuries. Although it is named after the French mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), who systematically studied it in his treatise Traité du triangle arithmétique, its origins can be traced back to earlier Chinese and Persian mathematics [1]. The 11th-century Chinese scholar Jia Xian documented this triangular structure in his now-lost work Shi Suo Suan Shu, which was later cited by Yang Hui in Xiangjie Jiuzhang Suanfa [2]. Around the same period, the Persian mathematicians Al-Karaji and later Omar Khayyám explored similar triangular configurations, leading to the structure being known in Iran as Khayyam’s Triangle [1].

Pascal’s Triangle serves as a fundamental object in enumerative combinatorics, giving rise to classical identities such as the hockey-stick identity and subset enumeration formulas [3]. These coefficients also play a central role in probability theory, particularly in modeling Bernoulli trials and in foundational results of statistical inference, such as those formalized by Feller in his treatment of the limit theorems [4]. Beyond combinatorics and probability, Pascal’s Triangle encodes rich number-theoretic structures, most notably, the Fibonacci sequence emerges along its shallow diagonals, illustrating deep interconnections between combinatorial arrays and recursive sequences [5]. Furthermore, the triangle’s recursive and symmetric properties naturally extend to the framework of Pascal matrices, which have proven useful in linear algebra for tasks such as solving systems of equations and analyzing matrix inverses and eigenstructures [6].

Pascal’s Triangle exhibits striking fractal properties under modular arithmetic, notably forming the Sierpiński triangle pattern, which has been applied in computational models and image compression algorithms [7]. In computer science, its recursive structure supports dynamic programming and enables efficient row generation algorithms with linear space complexity [8]. Binomial coefficients from the triangle also arise in quantum mechanics to describe probability amplitudes [9] and play a critical role in the design of error-correcting codes in engineering contexts [10]. Beyond science, the triangle’s intrinsic symmetry and generative rules have inspired artistic visualizations and parametric designs in architecture and digital media [11].

While the two-dimensional version of Pascal’s Triangle was documented as early as the 11th century, relatively few scholarly works addressed its generalizations to higher dimensions prior to the 20th century. Subsequently, a number of studies on the generalized Pascal’s Triangle began to emerge, such as [12,13]. Some works have even referred to the concept of a “Pascal’s Pyramid”. For example, Dario Picozzi [14] investigated the connections between projection operators and the generalized binomial coefficients proposed by Strehl [15]. In his work, Picozzi visualized these coefficients using a Pascal’s Pyramid structure and employed the properties of projection operators to develop more efficient algorithms for enforcing particle number conservation in quantum computation.

It is important to note, however, that the “Pascal Pyramid” described in [14] does not constitute a strict generalization of Pascal’s Triangle. A rigorous Pascal pyramid is a higher-dimensional combinatorial structure that encodes multinomial coefficients as volumetric elements, thereby extending the triangular concept into three dimensions and beyond. To date, formal publications that provide a rigorous generalization of Pascal’s Triangle, commonly referred to as the Pascal Pyramid, remain limited to only a few scattered sources [16,17]. Scholarly literature addressing generalizations to d-dimensional Pascal simplexes is even more scarce.

In this paper, we revisit the concept of the Pascal Pyramid and present several novel properties, each accompanied by rigorous mathematical proofs. While a few of these theorems may have appeared informally in unpublished or non-peer-reviewed sources, no formal references are available. The majority of the properties discussed herein are, to the best of our knowledge, presented for the first time.

This paper serves dual purposes: (1) to provide a systematic, self-contained reference for properties of Pascal Pyramids and Pascal Simplexes with rigorous proofs, and (2) to present original results and novel perspectives. Where appropriate, we provide multiple proofs for key theorems to illuminate different aspects: algebraic (via generating functions), combinatorial (via counting arguments), and graph-theoretic (via path counting).

Classical results presented for completeness (with proper citations):

- Theorem 1 (Recurrence relation)—well-known, see [18,19]

- Theorem 2 (Symmetry)—follows from factorial definition

- Theorem 3 (Sum equals )—consequence of multinomial theorem

Original contributions:

- Theorem 4 and congruence-class formulation

- Theorem 5 (Boundary property)

- Theorem 6 (Scaling property)

- Theorem 7 (Weighted sum formula)

- Theorem 8 (Multinomial convolution identity)

- Theorem 9 (Maximal coefficients in each layer)

- Systematic generalization framework (Section 5)

It is important to clarify that our identification of original contributions is based on a comprehensive review of publicly available literature to date. We acknowledge that this analysis may have overlooked results documented in specialized monographs, personal websites, patent databases, or non-indexed technical reports. This declaration of novelty is therefore qualified by the current accessibility of scholarly resources rather than implying absolute primacy of discovery.

We adopt the terms “Pascal Pyramid” and “Pascal Simplexes” to refer, respectively, to the three-dimensional and higher-dimensional generalizations of Pascal’s Triangle. These terms are used primarily for their intuitive clarity and accessibility.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we define the Pascal Pyramid and explore its relationship with trinomial coefficients. Section 3 presents a detailed examination of the recurrence relations. In Section 4, we discuss various properties such as the sum of coefficients and the root of unity identity. Section 5 extends these concepts to the Pascal Simplexes, providing analogous definitions and theorems. Finally, we conclude the paper in Section 6.

2. Pascal Pyramid and Trinomial Coefficients

The Pascal Pyramid is a three-dimensional extension of Pascal’s Triangle.

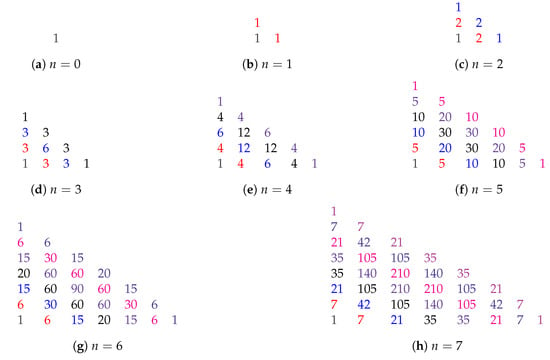

Definition 1

(Pascal Pyramid). Let represent the element at layer n and position in the Pascal Pyramid, where:

- 1.

- is the layer index,

- 2.

- are indices within the layer,

- 3.

- , ensuring valid positions within the pyramid,

- 4.

- is the third implicit index.

Each entry in the Pascal Pyramid represents the coefficient of a term in the trinomial expansion:

where and

is the trinomial coefficient, denoted by .

3. Recurrence Relation

Remark 1.

The following recurrence relation is well-known in the literature (see [18,19]) and is presented here for completeness and as a foundation for subsequent results.

Theorem 1.

The values in the Pascal Pyramid satisfy the recurrence relation:

where represents the trinomial coefficient with , and the base case is

Proof.

We now prove Theorem 1 using mathematical induction.

For the base case (), we have a single term:

Inductive Step: (), for , we consider the expansion:

Multiplying both sides by , we obtain

For n, by the definition of trinomial coefficients,

Comparing coefficients, we obtain:

which is precisely the recurrence relation.

Thus, the recurrence relation holds for all n, completing the proof. □

Combinatorial Proof.

The trinomial coefficient counts the number of ways to distribute n distinct objects into three labeled bins containing exactly a, b, and c objects, respectively.

To establish the recurrence, consider one particular object. We count all distributions of the remaining objects according to which bin contains this distinguished object:

- If it goes in bin 1: We need other objects in bin 1, giving ways

- If it goes in bin 2: We need other objects in bin 2, giving ways

- If it goes in bin 3: We need other objects in bin 3, giving ways

Summing these three disjoint cases yields: □

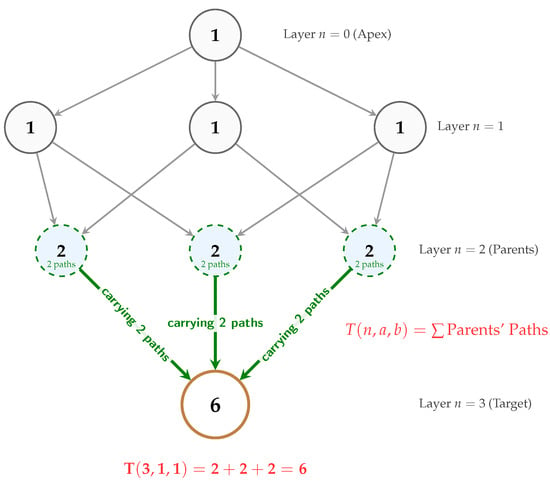

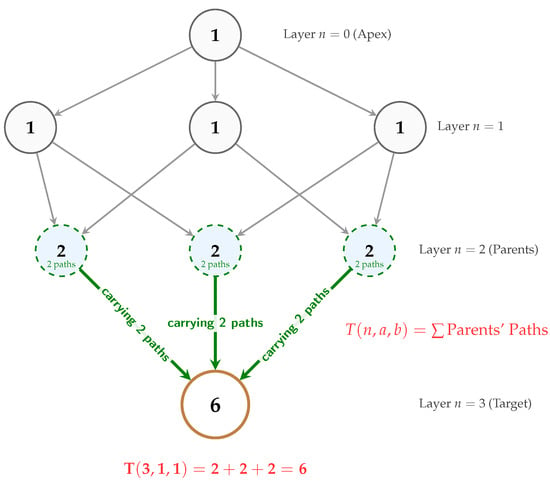

Remark 2 (Graph-theoretic interpretation).

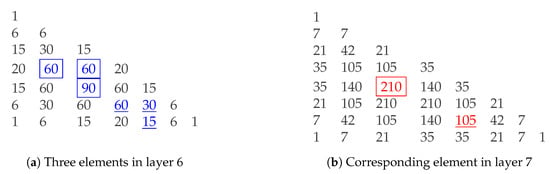

The recurrence relation admits a natural graph-theoretic interpretation. If we view the Pascal Pyramid as a directed graph where each element at layer n is connected to its three “parent” elements in layer , then equals the number of distinct paths of length n from the apex to the position . As illustrated in Figure 2, this path-counting perspective provides an alternative combinatorial understanding and illuminates connections between different theorems.

Figure 2.

Graph-theoretic interpretation of the Pascal Pyramid recurrence.

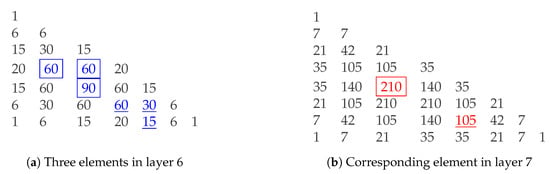

Example 2.

As shown in Figure 3,

Figure 3.

The recurrence relation in the Pascal Pyramid.

- 1.

- The element at position (row: 3, column: 2) in layer 7 can be calculated by summing three elements of layer 6:

- 2.

- The element at position (row: 1, column: 4) in layer 7 can be calculated as:

4. Some Properties of Pascal Pyramid

Remark 3.

The following symmetry property follows directly from the factorial definition of multinomial coefficients and is well-known.

Theorem 2.

The coefficients are symmetric under any permutation of the indices a, b, and c. This means that:

reflecting the inherent symmetry in the trinomial expansion.

Proof.

By Equation (2), we obtain:

□

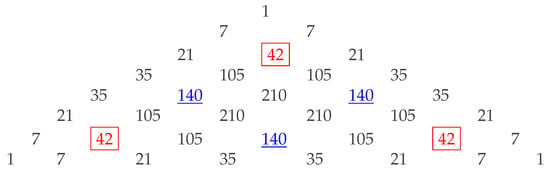

Figure 4 demonstrates the symmetry in the Pascal Pyramid.

Figure 4.

The symmetry in the Pascal Pyramid.

Remark 4.

The following result is a direct consequence of the multinomial theorem and is included for completeness.

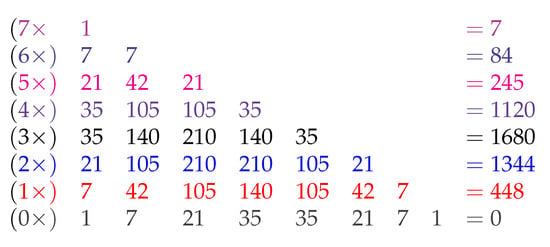

Theorem 3.

The sum of all elements in the n-th layer of the Pascal Pyramid is given by:

Proof.

Let the expansion be

If we set , then the left-hand side becomes

On the right-hand side, we have

Thus, we obtain the identity

□

It can be verified that the sum of all elements in Figure 4 equals 2187, namely, .

Theorem 3 is the three-dimensional analogue of the Pascal’s Triangle identity:

Theorem 4.

For any positive integer , the following identity holds:

where ω is a primitive cube root of unity (that is, ).

Proof.

Consider the trinomial expansion:

Substitute

Since

it follows that

On the other hand, by the trinomial expansion we have

Thus, for any positive integer , we obtain the following identity:

□

Example 3.

When , the calculation of involves the sum of 36 terms. However, it can be verified that the sum of any three symmetric elements is zero. For example, as shown in Figure 4,

Likewise,

Therefore, the total sum is zero.

Corollary 1 (Congruence-class sums).

For any positive integer , define

Then .

This provides an alternative formulation of Theorem 4: the root-of-unity cancellation occurs because the three congruence classes contribute equally, and . This is analogous to the alternating sum property of Pascal’s Triangle where the sum of alternating terms equals zero.

Theorem 5.

The outermost elements of the cross-section of the Pascal Pyramid form the n-th row of the Pascal’s Triangle. Specifically, the boundary elements of the cross-section (diagonals) collectively form a Pascal’s Triangle.

Proof.

Therefore, the diagonal elements correspond to the n-th row of the Pascal’s Triangle. □

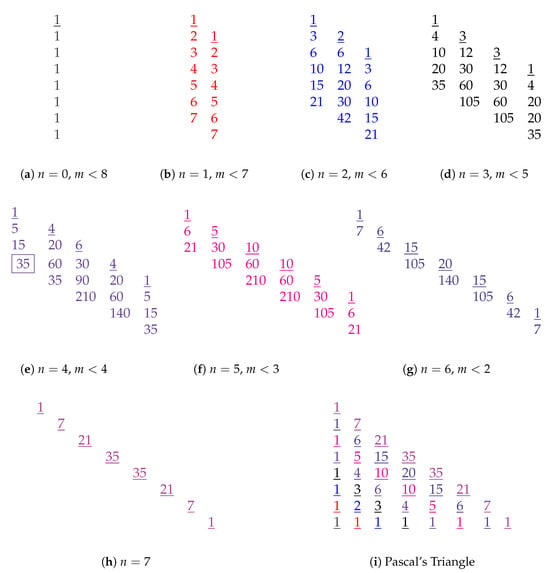

The Pascal’s Triangle formed in Theorem 5 is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The diagonals of the cross-section of the Pascal Pyramid form a Pascal’s Triangle.

Remark 5 (Graph-theoretic interpretation).

As explained previously, in the directed acyclic graph underlying the Pascal Pyramid, each vertex has up to three incoming edges from its “parent’’ vertices in layer . The boundary of the pyramid, where one coordinate is zero, such as , forms an induced subgraph in which only two parent edges remain valid. Consequently, each boundary vertex satisfies the same two-parent recurrence as a vertex in Pascal’s Triangle. This induced subgraph is therefore isomorphic to the standard Pascal-triangle graph, and the boundary entries correspond exactly to the binomial coefficients forming the n-th row of the Pascal’s Triangle.

In the cross-section of the Pascal Pyramid at layer n, consider any diagonal sequence of trinomial coefficients. Below this diagonal sequence, there exists an entire family of sequences, each of which has the same length as the original diagonal sequence. Furthermore, every sequence in this family is proportional to the original diagonal sequence.

Theorem 6.

Let

be a diagonal sequence in the n-th layer of the Pascal Pyramid, where each is a trinomial coefficient. Then for every , there exists a sequence

in the -th layer such that

where the proportionality constant depends only on m and n.

Example 4.

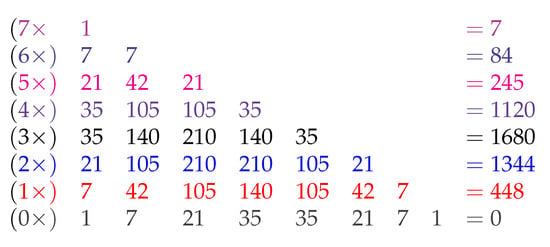

Theorem 7 (Weighted Sum of Trinomial Coefficients).

For any non-negative integer n, the following identity holds:

Proof.

We start from the trinomial expansion:

Differentiating both sides with respect to x and then setting , we obtain:

□

Example 5.

Figure 6.

Weighted row sum in layer 7.

The RHS is . Both sides agree, confirming the theorem for the case n = 7.

Theorem 8.

For non-negative integers satisfying and , the following identity holds:

where the summations are constrained by .

Proof.

Equation (8) is equal to the following equation:

The generating function for multinomial coefficients is:

Multiply the generating functions:

The coefficient of in the product is:

Simplifying yields the LHS.

The coefficient of in is (RHS), confirming the identity. □

Example 6.

For , , , , , the LHS becomes:

Terms occur when , , and . The LHS can be calculated as .

The RHS is

Both sides agree, confirming the Theorem 8 for this case.

Theorem 9 (Maximal Coefficients in Pascal Pyramid Layers).

For each non-negative integer n, the maximal multinomial coefficient in the n-th layer of the Pascal Pyramid occurs at the triplet where each component is as equal as possible. Specifically:

- 1.

- If , the maximal coefficient is

- 2.

- If , the maximal coefficient is

- 3.

- If , the maximal coefficient is

Proof.

Consider two adjacent triplets and . The ratio of their coefficients is:

The coefficient increases when and decreases when . Thus, the maximum occurs when .

Specifically,

- 1.

- If , then the maximum occurs at .

- 2.

- If , then the maximum occurs at .

- 3.

- If , then the maximum occurs at .

□

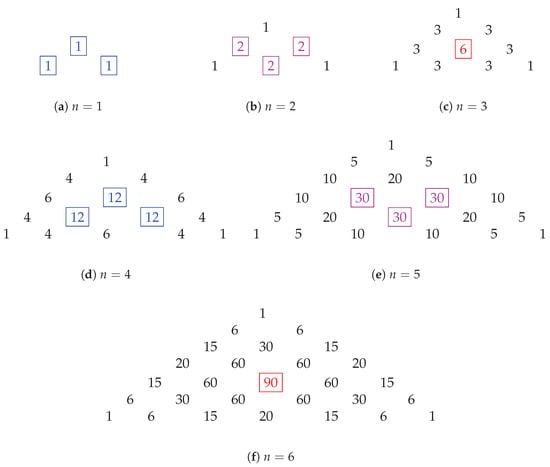

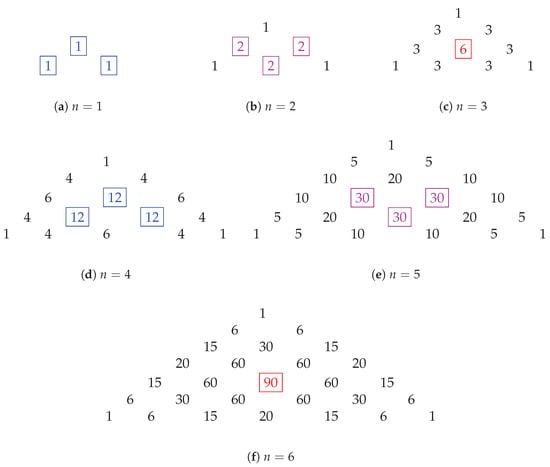

Example 7.

Figure 7 lists the maximal coefficients in layers 1–6. As shown in Figure 7e, for , the maximal coefficient 30 occurs at .

Figure 7.

Maximal coefficients in layers 1–6.

The maximal coefficients correspond to the “center” of the layer in the Pascal Pyramid.

Corollary 2.

If , then the center of the layer includes only one maximum. If , then the center of the layer includes three maxima.

For the case of , the center includes , , and . For the case of , the center includes , , and . Different centers can be observed in Figure 7a–f.

5. Generalization to Pascal Simplexes

The theorems mentioned in the previous section can be generalized from the Pascal Pyramid to higher dimensions. Currently, there is no widely accepted terminology for the higher-dimensional analogs of the Pascal Pyramid in formal publications. However, the term Pascal Simplexes occasionally appears in informal discussions. We consider this term to be appropriate and will adopt it throughout this paper.

To facilitate a comparison between the theorems presented in this section and their counterparts from the previous section, we provide Table 1, which outlines the corresponding relationships. The majority of the theorems concerning Pascal Simplexes listed here have proofs that are analogous to those of their corresponding theorems in the context of the Pascal Pyramid. Therefore, to maintain conciseness, we omit these proofs.

Table 1.

Pascal simplexes generalized from Pascal pyramid.

For Theorem 17, however, we provide a detailed proof. This proof differs from that of its corresponding theorem (Theorem 8) and is intended to illustrate that such theorems often admit multiple proofs. It is also worth noting that Zeng [20] had already proposed and proved Theorem 17 in 1996. Nevertheless, Zeng’s formulation and proof were developed independently of any connection to the Pascal simplex.

Definition 2 (Pascal Simplex).

Let denote the element at layer n and position in the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex, where:

- 1.

- is the layer index,

- 2.

- for all are the position indices within the layer,

- 3.

- , ensuring valid positions within the simplex.

Each entry in the Pascal Simplex represents the multinomial coefficient appearing in the expansion of a multinomial expression:

where

is the multinomial coefficient. The position corresponds to the coefficient , where .

Theorem 10.

The entries in the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex satisfy the following recurrence relation:

where the expression inside the sum omits , which is implicitly defined by

and where any term with a negative index (i.e., ) is interpreted as zero.

The base case is given by

Theorem 11.

The multinomial coefficients represented by the entries of the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex are symmetric under any permutation of the indices , where . That is, for any permutation , we have:

which reflects the intrinsic symmetry of the multinomial expansion. Consequently, for all such index tuples, the corresponding coefficients satisfy:

where the d-th component is always determined by , and the equality holds for any permutation σ of .

Theorem 12.

Let be an integer. Denote by the multinomial coefficient

where , and all . Then the sum of all such coefficients in the n-th layer of the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex satisfies the identity:

Theorem 13.

Let ω be a primitive d-th root of unity, i.e., and for all . Then for any positive integer , the following identity holds:

Equivalently, using the notation of the Pascal Simplex, we may express this as:

where the last coordinate is defined by , and the sum ranges over all non-negative integer tuples such that .

Theorem 14.

In the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex, the boundary elements of the n-th layer, namely, the coefficients for which at least one of the indices equals zero, collectively form the entries of the -dimensional Pascal Simplex of layer n.

In particular, for any fixed , the outermost elements of the n-th layer of the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex project onto the -dimensional Pascal Simplex at the same layer. This generalizes the well-known fact that the boundary elements of the Pascal Pyramid (i.e., the 3-dimensional case) form Pascal’s Triangle rows.

Theorem 15.

Let be a fixed integer, and let . Consider the diagonal sequence in the n-th layer of the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex defined by:

where each term corresponds to a coefficient along a specific diagonal direction with all but two indices fixed at zero.

Then, for every integer , there exists a corresponding sequence in the -th layer:

such that

where the proportionality constant depends only on m, n, and the dimension d, but is independent of the index i within the sequence.

Theorem 16.

Let be an integer. For any non-negative integer n, the following identity holds:

where denotes the multinomial coefficient

Theorem 17 (Multinomial Convolution Identity).

Let be an integer. Let , and let such that

Then the following identity holds:

where each term implicitly satisfies and .

Combinatorial Proof.

Let S be a finite set with n distinguishable elements. We consider the number of ways to partition S into d ordered parts , such that for . The total number of such ordered partitions is given by the multinomial coefficient:

We now re-count this quantity via a two-stage combinatorial process. We partition the process of dividing the set S into the desired parts in two steps:

We first choose m elements from S (in ways), but we will account for this choice implicitly. We then partition these m elements into d ordered subsets , such that , where . The number of such partitions is:

where .

Next, we partition the remaining elements into d ordered subsets , such that for . The number of such partitions is:

with .

By combining for all i, we obtain an ordered partition of the full set S into , with .

To account for all ways in which this two-stage process can yield the final partition, we sum over all possible values of , satisfying and implicitly .

Hence, the total number of such two-step decompositions is:

Since both the left-hand side and right-hand side count the same set of ordered partitions of S into with respective sizes , the identity holds combinatorially:

□

Theorem 18.

Let be an integer, and let n be a non-negative integer. The maximal multinomial coefficient in the n-th layer of the d-dimensional Pascal Simplex occurs at the multi-index where each component is as equal as possible. Specifically, for where and , the maximal coefficient is given by one of the following:

If , the maximal coefficient occurs at:

If , the maximal coefficient occurs at:

If , , the maximal coefficient occurs at:

6. Conclusions

In this study, we present a comprehensive examination of the Pascal Pyramid, elucidating its structural properties and deriving several novel mathematical results. Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of multidimensional combinatorial systems and address a significant gap in the existing literature, as formal studies on the Pascal Pyramid and Pascal simplices remain relatively limited.

While this paper provides a systematic exposition of Pascal Pyramids and their higher-dimensional analogues, several intriguing questions remain open for future investigation:

- Is there a natural q-analogue of the Pascal Pyramid that generalizes the Gaussian binomial coefficients to the trinomial case? What properties would such a structure possess?

- The classical Vandermonde identity states that . Does there exist a natural analogue for trinomial coefficients?

- What can be said about the asymptotic distribution of coefficients in Pascal Pyramids? Are there central limit theorem analogues for random walks in 3D or higher dimensions?

- Following Németh [16], what other geometric interpretations or generalizations (hyperbolic, elliptic, etc.) might yield interesting combinatorial structures?

- Can the multinomial coefficients be interpreted in terms of discrete probability distributions in ways that parallel the binomial–Bernoulli connection?

- What is the computational complexity of efficiently computing specific entries or patterns in high-dimensional Pascal Simplexes?

We hope these questions inspire further research into the rich structure of multidimensional Pascal arrays.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sym18010097/s1. An animated visualization illustrating the rotational dynamics of a Pascal pyramid is provided in RotationalPyramid.mp4. Readers interested in the Python code used to produce this animation are welcome to contact the author by email.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wilson, R. Anniversaries: Pascal. In The Mathematical Intelligencer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lay-Yong, L. The Chinese connection between the pascal triangle and the solution of numerical equations of any degree. Hist. Math. 1980, 7, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampiris, E.; Caire, G. Adapt or Wait: Quality Adaptation for Cache-aided Channels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 73, 4868–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, W. The Fundamental Limit Theorems in Probability. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1945, 51, 800–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budgor, A.B. Star Polygons, Pascal’s Triangle, and Fibonacci Numbers. Fibonacci Q. 1980, 18, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. Revisiting the Pascal matrix. Am. Math. Mon. 2010, 117, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Dai, J.; Zhou, X.; Kuttner, J.; Hilt, G.; Shao, X.; Gottfried, J.M.; Wu, K. Assembling molecular Sierpiński triangle fractals. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms. In Section on Pascal’s Triangle Algorithms, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Sudarshan, E. Complex measures and amplitudes, generalized stochastic processes and their applications to quantum mechanics. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1994, 27, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, H.S.; Slotnick, D.L. On the mathematical theory of error-correcting codes. Ibm J. Res. Dev. 1959, 3, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakhov, A. The Generalized Principle of the Golden Section and its applications in mathematics, science, and engineering. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2005, 26, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Ollerton, A.G.S. Some Properties of Generalized Pascal Squares and Triangles. Fibonacci Q. 1998, 36, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.; Brandt Kronholm, J.W. Iterated rascal triangles. Aequationes Math. 2024, 98, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picozzi, D. Pascal’s pyramid and number projection operators for quantum computation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.16561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehl, V. Polynômes d’Hermite généralisés et identités de SZEGÖ-une version combinatoire. In Proceedings of the Polynômes Orthogonaux et Applications, Bar-le-Duc, France, 15–18 October 1984; Brezinski, C., Draux, A., Magnus, A.P., Maroni, P., Ronveaux, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, L. On the hyperbolic Pascal pyramid. Beiträge Zur Algebra Und Geom. Algebra Geom. 2016, 57, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Properties and Applications of Pascal’s Triangle and Pascal’s Pyramid. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2025, 84, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbachir, H.; Mehdaoui, A.; Szalay, L. Diagonal sums in Pascal pyramid. J. Comb. Theory Ser. A 2019, 165, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitler, H. Trinomial formula, Pascal- and Sierpinski-pyramid. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 33, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J. Multinomial convolution polynomials. Discret. Math. 1996, 160, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.