Abstract

The paper presents a statistical model based on the two-weighted exponential distribution (TWED) to examine censored Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) survival information. Identifying HIV as a disability, the study endorses an inclusive and sustainable health policy framework through some predictive findings. The TWED provides an accurate representation of the inherent hazard patterns and also improves the modelling of survival data. The parameter estimation is achieved in both a classical maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and a Bayesian approach. Bayesian inference can be carried out under general entropy loss conditions and the symmetric squared error loss function through the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method. Based on the symmetric properties of the inverse of the Fisher information matrix, the asymptotic confidence intervals (ACLs) for the MLEs are constructed. Moreover, two-sided symmetric credible intervals (CRIs) of Bayesian estimates are also constructed based on the MCMC results that are based on symmetric normal proposals. The simulation studies are very important for indicating the correctness and probability of a statistical estimator. Implementing the model on actual HIV data illustrates its usefulness. Altogether, the paper supports the idea that statistics play an essential role in promoting disability-friendly and sustainable research in the field of public health in general.

Keywords:

survival analysis; maximum likelihood estimation; Bayesian estimation; disability and sustainable health systems; HIV data MSC:

62E10; 62F15; 62N02; 62P10; 60E05

1. Introduction

HIV is a major public health problem around the world impacting millions of people. In addition to medical implications, HIV has social and legal implications. Most countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, have included HIV as a disability under the laws against discrimination due to the long-term effects of the virus on health and involvement in society. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), people with HIV are considered to be covered by all the discrimination protections, notwithstanding the presence of symptoms. For more details, refer to the U.S. Department of Justice [1]. Statistical modelling can be used to analyse survival patterns, estimate life expectancy, and assess risk factors of death in HIV-positive individuals. Furthermore, evidence-based policy, resource allocation, and observance of legal and ethical provisions stipulated by international frameworks may be affected by disability data, especially those informed as a result of high-end statistical techniques; see Mitra et al. [2]. Recently published research indicates the iterative exploration of new statistical instruments, namely, survival models and Bayesian models, to comprehensively overcome the challenges of censored statistics, time-to-event results, and inaccuracy in the real-life datasets related to disability; see Groce [3] and Lee and Wang [4].

We point out that the TWED is a generalization of the traditional exponential distribution, as presented by Gupta and Kundu [5] and generalised by Shakhatreh [6], which can be used to represent non-constant hazard rates. Our contribution will involve developing Bayesian inference techniques for the TWED and comparing the outcomes of classical methods with those of the Bayesian method. Shakhatreh [6] previously determined the MLEs of the TWED; we extend this to obtain the Bayesian estimates corresponding to a loss function of both symmetric squared error and general entropy using a Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler. An extensive simulation study, along with an application on real data, is also provided to illustrate the power of the Bayesian approach in terms of interval estimation and performance of censored data. Moreover, we quote the results of Shakhatreh [6] on the TWED better fitting an HIV survival dataset than alternative distributions to justify focusing on the TWED in the analysis of such data.

This paper has been framed to give a clear statistical model of the survival of HIV-infected patients using the two-weighted exponential distribution (TWED). In Section 2, the model formulation and theoretical basis of the TWED, a flexible distribution with two extra shape parameters, are presented. The flexibility enables the TWED to capture the differences in the hazard behaviours and adapt to different censoring structures regularly observed in survival data. Section 3 obtains the MLEs of the model parameters and suggests their confidence intervals with asymptotic and bootstrap methods. In Section 4, the Bayesian estimation technique is presented, and the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method is used with both symmetric squared error loss (SEL) and general entropy loss (GEL) functions. A simulation study of the performance of the suggested estimators with different sample sizes was conducted as outlined in Section 5. Section 6 describes our use of the model on a real dataset of HIV patient survival times and compares and contrasts the results of classical and Bayesian inference. Lastly, Section 7 presents the major findings and future recommendations.

2. Model Description

This section presents the TWED as a model for survival data subject to right-censoring. The section shows how the distribution can adapt to different hazard rates and includes a model based on proportional hazard, which is the basis for the next estimation method. Consider an experiment setup with n units, each of which has a lifetime represented by the notation . With cumulative distribution function (CDF), , and probability density function (PDF), , these lifetimes are defined as independent and identically distributed (iid) random variables. Furthermore, the iid random censoring times for these units are represented by the additional sequences defined by CDF and PDF We can observe iid random pairs where assuming mutual independence between and Furthermore, we define , described by the CDF as

It becomes apparent that the joint PDF of and is

Additionally, the random variable X and T adhere to the proportional hazards model, governed by the proportionality constant given by

For more details on the proportional hazards model, see Danish et al. [7]. From Equations (1) and (2) we obtain the joint density joint of Y and D

Gupta and Kundu [5] proposed the weighted exponential distribution, which has been used to describe the classical exponential model as an attempt at generalization to capture non-constant hazard rates. Extending the model on their foundation, Shakhatreh [6] further generalized the model by introducing yet another parameter to make it even more flexible in fitting lifetime data. Shakhatreh [6] determined key statistical features of the TWED, like the moments and quantiles. Shakhatreh [6] obtained only the maximum likelihood estimates, showing that the model works better with censored survival data. The PDF of the TWED is given as follows:

where

The survival and hazard functions for the TWED are given, respectively, as

and

From Equations (4) and (5), the density function in Equation (3) appears as follows:

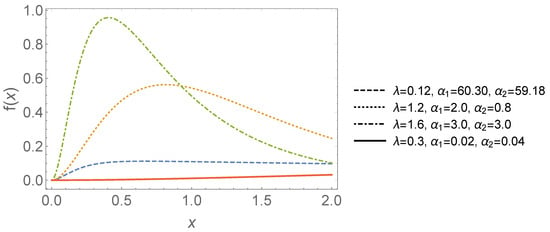

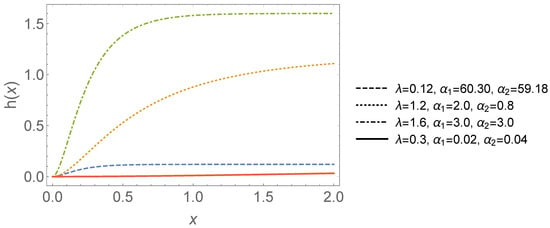

To conclude, the TWED offers a general model that is generative with a wide range of modelling characteristics of hazard rate behaviour. Its shape and hazard functions vary in a meaningful way as the parameters are varied, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2; therefore, it is suitable for the analysis of survival data, especially in situations where some censored data are used.

Figure 1.

PDF of the TWED (inspired from Shakhatreh [6]).

Figure 2.

The hazard function of the TWED (inspired from Shakhatreh [6]).

3. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

This section gives an outline of MLE when fitting the TWED model. It obtains the log-likelihood function with right-censorship, and it estimates the parameters numerically. Based on the model observations, deciphered in Section 2, and referring to Equation (3), the likelihood function can be written as follows:

where The likelihood function is the basis of inferences, and it varies based on the nature of observed datasets, whether these data are complete or right-censored; see Casella and Berger [8]. Taking the logarithm of Equation (7), we have

Equating each of the first partial derivatives of Equation (8) to zero with respect to the involved parameters results in the following:

and

Since Equations (9)–(12) cannot be solved analytically, the Newton–Raphson iteration approach is one of the appropriate numerical techniques that may be used to obtain the estimates. Wolfram Mathematica Version 12 has been used, through some commands, to deploy the Newton–Raphson iteration; for more details, see Mohammad et al. [9].

3.1. Approximate Confidence Interval

The asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimates is applied asymptotically to determine approximate confidence intervals for TWED parameters, where approximate variances are produced based on the inverse of the observed result of a Fisher information matrix. The delta method is used to estimate these variances in the case of survival and hazard functions so that the construction of confidence intervals is practical, on a case-by-case basis, as a function of the estimated parameters; for more details see Greene [10].

The ACIs of the TWED parameters at a confidence level , can be given as follows:

while the ACI of the proportionality hazard constant is given by

The variance quantities of the MLEs , and are estimated from the inverse of the Fisher information matrix.

Referring to the delta method approach, the variance of and can be approximated, respectively, by

where represents the inverse of the Fisher information matrix, which is a symmetric squared matrix, while and are the gradients of and , respectively, with respect to and

For computational purposes, the survival and hazard functions may be written as functions in TWED parameters and the proportionality hazard constant but keep in mind that

which is to justify the algebraic operations when multiplying matrices; refer to Equation (13) as the square matrix is from the rank

3.2. Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

In this subsection, confidence intervals are proposed based on the parametric bootstrap methods where the parametric model for the data is known, , where bootstrap data are sampled from where are the MLEs obtained from the original data. For the resampling process, a Wolfram Mathematica command, “RandomChoice”, is used to generate 1000 bootstrap samples based on the principle of drawing with replacement. For an explanation of how the “RandomChoice” command works, see the following URL: https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/RandomChoice.html, accessed on 20 July 2025. Recently, many papers have dealt with bootstrap methods based on the idea of Efron [11], such as Qin et al. [12] and Al Luhayb et al. [13]. After the bootstrap samples are generated based on the MLEs and the inference approaches have been applied to these samples, the results that represent the bootstrap estimates, say , are sorted, and the confidence intervals for the parameters, survival, and hazard functions are constructed in the following manner to obtain the percentile bootstrap (Boot-P) confidence intervals: let be the cumulative distribution function of Define for given z. The approximate bootstrap-p confidence interval of is given by

4. Bayesian Estimation

This section introduces Bayesian estimation of the TWED model with the MCMC method with the loss functions of the squared error and general entropy. The Bayesian method makes use of prior knowledge, and it is applicable in censored survival data with flexible inference and credible intervals due to uncertainty regarding parameters.

It is assumed that the prior knowledge about the parameters and is represented by the informative gamma priors as follows:

The joint prior density function can be written as follows:

The expressions in Equations (7) and (14) are combined to obtain the joint posterior of and as follows:

The Bayesian estimates of any function of the parameters, say , under the squared error loss (SEL) function are

The general entropy loss (GEL) function, which was proposed by Calarbria and Pulcini [14], is another loss function that can be applied. The following represents this loss function, which is a generalization of the entropy loss function:

where is the decision rule which estimate Under the GEL function the Bayes estimate of the parameter, is given as follows:

It is noted that when q is equal to , the Bayes estimators of the GEL function are reduced to those of the SEL function.

The Bayes estimates for a function employing the GEL function, can be represented as

The ratio of two integrals presented by Equations (16) and (17) cannot be provided in the form of a closed expression. Thus, Gibbs sampling and more generally the Metropolis–Hastings (M-H) algorithm within-Gibbs samplers are regarded as an important subclass of Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approaches. The Metropolis algorithm was first formulated by Metropolis et al. [15], and Hastings [16] later generalised the Metropolis algorithm. The complexity of Bayesian computations, in this case, can be addressed by implementing a coded software package to execute the Metropolis–Hastings (M-H) algorithm to guarantee a convergence behaviour of the estimates. In this study the “Metropolis–Hastings” coded package in Wolfram Mathematica was used: https://resources.wolframcloud.com/FunctionRepository/resources/MetropolisHastingsSequence/, accessed on 1 November 2025. The application of the MCMC method requires the conditional posterior distributions of the unknown parameters to be defined as follows:

Based on Equation (15), we get

where The derivation of conditional posteriors from the joint posterior distribution (15) is a common strategy in the literature to obtain the Bayesian estimates of the parameters; see, for example, Casella and Berger [8].

Since the conditional posteriors of and are unknown distributions, the MCMC approach based on Metropolis-within-Gibbs samplers is used as follows:

1. Start with and .

2. Let .

3. Generate from

4. Using the following M-H algorithm, generate and from (18)–(20) with normal suggested distribution (symmetric proposals) , and , where , , and , respectively, can be obtained from the main diagonal in the inverse fisher information matrix.

(i) Generate a proposal from from and from

(ii) Evaluate the acceptance probabilities

5. Compute and

6. Evaluate the reliability and hazard functions as follows:

7. Let .

8. Repeat Steps (4–6) 1000 times.

9. To guarantee the convergence to remove the influence of the selection of initial values, the first M simulated varieties are ignored. Then the selected samples are and for sufficiently large L, which forms an approximate posterior sample which can be used to obtain the Bayes MCMC point estimates of and based on SEL, respectively:

10. Now, the Bayes estimates of and under the GEL function using MCMC method are, respectively, obtained as

11. To compute the credible intervals of and order , and Then the credible intervals of are given by

5. Simulation Study

In general, simulation studies can play a strong role in interpreting, confirming, and comparing procedures of statistical inference when theory or real data is insufficient. A simulation study was performed to assess the performance of the proposed estimators developed in Section 3 and Section 4. Six sample sizes ( 40, 80, 100, and 120) were considered, and all calculations were implemented using Wolfram Mathematica version 12. The command that was adopted for the generation of samples is “ProbabilityDistribution”. An explanation of this command can be obtained through the following URL: https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/ProbabilityDistribution.html, accessed on 20 November 2025. Parameters values that were used for generating the simulated samples were chosen as follows: . The Bayesian estimates were computed based on the MCMC method hyperparameters under the SEL and GEL functions as for the case of the GEL function. The hyperparameters for Gamma priors were all selected equally to be which expresses weakly knowledgeable priors. The survival and hazard functions were estimated at The comparison of the estimates was performed using their mean square error (MSE) and bias using 12,000 simulated samples. The coverage probability (CP) and average length of confidence intervals (ALCI) were also considered in the comparison between the simulated samples.

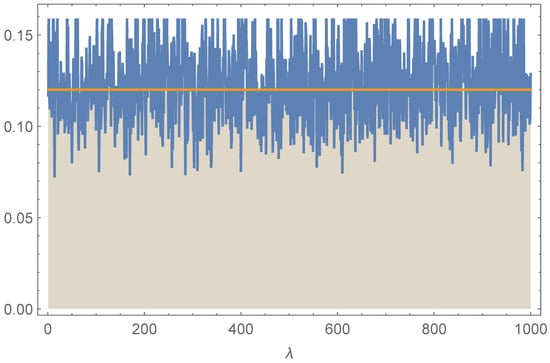

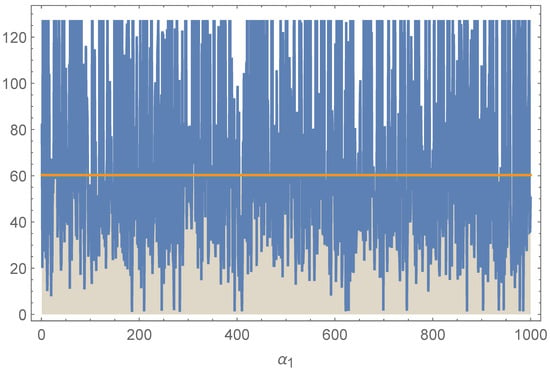

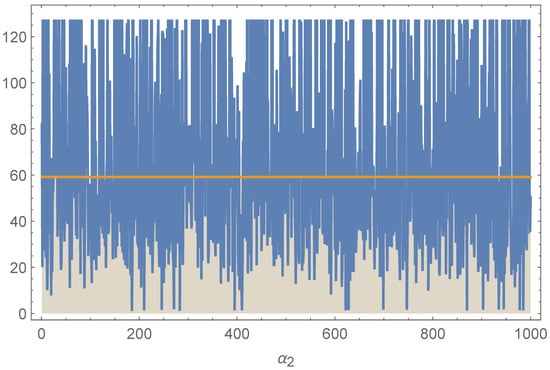

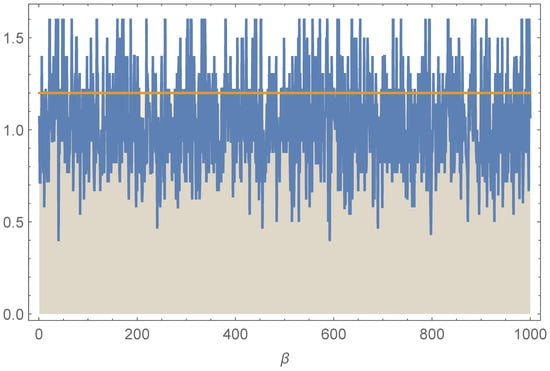

Tracing plots of the posterior samples of the parameters calculated based on the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. These plots depict well-mixed chains with stable fluctuations and no visible trends, indicating satisfactory convergence, which indicates that the Bayesian estimates provided were valid.

Figure 3.

Tracing plots for the parameter .

Figure 4.

Tracing plots for the parameter .

Figure 5.

Tracing plots for the parameter .

Figure 6.

Tracing plots for the parameter .

Further, the simulation results are tabulated in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, providing a comprehensive comparison across different methods as follows:

Table 1.

Estimates for the parameter .

Table 2.

Estimates for the parameter .

Table 3.

Estimates for the parameter .

Table 4.

Estimates for the parameter .

Table 5.

ALCIs and CPs for the parameters and .

Table 6.

ALCIs and CPs for the parameters and .

Table 7.

ALCIs and CPs for the functions and at .

- Table 1: Across all sample sizes, MLE of performs better, having less bias and less MSE than both Bayesian SEL and GEL. The Bayesian SEL and GEL estimators, on the contrary, have greater bias and MSE. Generally, it is evident that MLE is better at estimating the parameter

- Table 2: MLE yields very large bias and MSE for , especially at smaller sample sizes, whereas SEL and GEL deliver much lower bias with far better accuracy. Consequently, as n increases, Bayesian estimates remain steady and continue to outperform MLE, highlighting their robustness.

- Table 3: The estimation of again shows extremely high bias and MSE with MLE; however, Bayesian SEL and GEL consistently provide low bias and strong accuracy. As a result, performance becomes particularly stable for n ≥ 80, with both Bayesian methods producing almost identical outcomes.

- Table 4: Although all methods exhibit negative bias when estimating , they remain close in overall performance, and MSE decreases steadily with larger n. Therefore, estimator stability improves for all approaches, and no major differences emerge among the three methods.

- Table 5: Bayesian intervals for and are much shorter than non-Bayesian ACIs, yet their coverage probabilities remain relatively stable across sample sizes. Nevertheless, the non-Bayesian ACIs achieve slightly higher coverage but only at the expense of extremely wide intervals, especially for .

- Table 6: For , non-Bayesian ACIs are extremely wide, while Bayesian intervals are far more practical and precise, leading to acceptable, though slightly lower, coverage due to their tightness. Similarly, intervals benefit from increased precision in Bayesian estimation, particularly at larger sample sizes.

- Table 7: Bayesian intervals for and remain consistently shorter than their MLE-based counterparts, while coverage probabilities stay stable across all n. Hence, Bayesian methods provide clearly more precise functional estimates, especially once n reaches 80 or higher.

According to the results of the simulation, MLE is not always better than Bayesian estimation in small samples, particularly when its bias and MSE values are large ( and ). Bayesian SEL and GEL do not change with n and are obviously better with larger sample sizes, especially above . These gains are particularly pronounced in interval estimation and the estimation of such functionals as the survival and hazard functions, where Bayesian techniques provide more accurate inferences as the sample size increases. This simulation further enables the Bayesian approaches to have more power to be used in the real data context, as discussed in the next section on the HIV survival dataset.

6. Data Analysis

In this section, a real-data application is presented to demonstrate the practicality of the proposed methods. Survival times (in months) of 100 HIV-infected patients were analysed, as reported by Hosmer and Lemeshow [17], with right-censored observations indicated by a plus sign.

| Observed HIV dataset | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 8 | 3 | 22 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 15 | 34 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| 6 | 11 | 5 | 13 | 30 | |||||||||||||

| 36 | 35 | 11 | 15 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 32 | 11 | 31 | 58 | 1 | 43 | ||||||||||||

| 14 | 54 | 10 | 57 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | 10 | 53 | |||||||||||||||

Shakhatreh [6] showed that the TWED is a well-fitted distribution to the HIV data and compared the TWED with other alternatives like generalised Weibull, weighted exponential, Weibull, and log logistic distributions. The comparison showed that the TWED was superior in fitting the data through the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

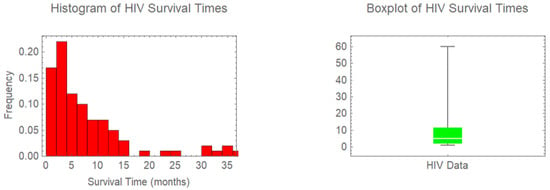

The important statistics of the HIV survival data are provided in Table 8, which shows a high right skewness () and much variability. Mean survival is months but with a median survival of a mere five months, implying that the majority of patients have short survival periods, with some of them having far longer survival periods. The dispersion index (D as D is the ratio of the variance to the average) shows the presence of over-dispersion since the value is considerably above 1. This implies that the variability in survival distribution is higher than it would be under a regular exponential model, where the risk is constant.

Table 8.

Summary statistics for HIV data.

These observations can be supported by Figure 7 with the major concentration in the histogram of the patients with low survival times, and the data is skewed, with the boxplot showing extreme survival times. The combination of the numerical and graphical evidence supports the necessity of a flexible surviving distribution, such as the TWED, that fits such heterogeneity and skewed behaviour in the data.

Figure 7.

Histogram and boxplot of HIV data.

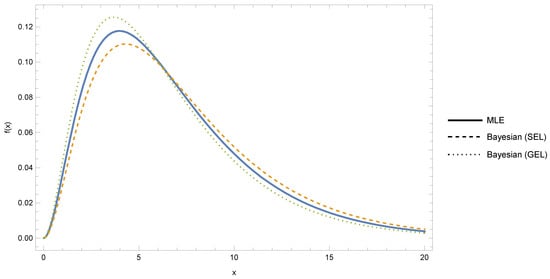

Both classical (MLE) and Bayesian (SEL and GEL) methods were used with the the same dataset, which makes it possible to directly compare the obtained point estimates, confidence intervals, and predictive functions, including survival and hazard rates. This empirical framework explains and complements the results of the simulation in Section 5.

In Table 9, point estimates are given in the MLE and Bayesian approaches of under SEL and GEL functions. The findings demonstrate that there is a strong association in all the techniques and little variation. Specifically, the estimates are almost equal (about ), and the same could be said about (it varies around 0.582–0.587). This strengthens the validity of both Bayesian and classical methods.

Table 9.

Different point estimates for .

As illustrated in Figure 8, the PDF curves using MLE, SEL, and GEL estimations are almost the same, with slight distinctions only in the early parts of the distribution. This tight fit indicates the strength of the TWED fit and proves that both the Bayesian and classical analysis methodologies provide consistent inferences to the HIV survival data.

Figure 8.

PDF based on MLE, SEL, and GEL estimates of the TWED parameters.

Table 10 provides confidence intervals and their length. The Bayesian yield results in much narrower intervals than the non-Bayesian (bootstrap) method. As an example, the credible interval of the is much smaller (length ) than the bootstrap interval (length ). This finding indicates that Bayesian methods yield interval estimates that are narrower, and it confirms the trend seen in the simulation study.

Table 10.

The 95% confidence intervals for .

The results focus on the significance of early intervention and lifelong care, and a conjoint impression of risk and survival during early HIV progression is presented in terms of the probability of and . At two months, the probability of survival in HIV patients will be about , which translates to the fact that more than of the HIV patients will survive until after the two months. The hazard rate is approximated to be , which implies that if a patient survives to two months, that person will have a risk of dying of at that instance. Bayesian techniques, particularly in GEL, give very precise approximations; this kind of statistical accuracy increases the confidence of clinical expectations and planning.

7. Conclusions

The TWED is explored in this paper in terms of its role as a strong model for analysing censored data of HIV survival. Using the classical and the Bayesian approaches of estimation, the TWED is demonstrated to capture a large array of hazard behaviour, providing relevant information on patient survival. Bayesian estimation was more accurate, and narrower credible intervals were obtained, especially when using the general entropy Loss. As shown in Section 6, the model gave consistent survival probabilities and hazard rates, thus indicating its practical applicability. The above observations justify the importance of high-tech statistical methods in the study of disability-related healthcare and long-term care planning. In the future, the associations of the survival risk factors might be further clarified in the context of a regression-based TWED model including covariates. The robustness of the model could further be tested through comparative studies with alternative distributions. The simulation study was performed on large sample sizes to demonstrate the dependence of the performance of the estimators on the amount of data. These findings prove that Bayesian estimators (symmetric SEL and GEL) converge to MLE, yielding smaller intervals with confident coverage. Figure 1 and Figure 2 graphically show the influence of the parameters of the simulation on the PDF and hazard functions. It is also shown in Figure 4 that the fitted curves of the PDF of estimates of MLE, symmetric SEL, and GEL are almost identical to the HIV data, which indicates the consistency of these estimation methods and the stability of the TWED model in real data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.S. and M.M.M.M.; Methodology, A.S.A.-M., K.S.S., and M.M.M.M.; Software, M.M.M.M.; Validation, A.S.A.-M. and M.M.M.M.; Formal analysis, K.S.S.; Investigation, K.S.S.; Resources, A.S.A.-M.; Data curation, M.M.M.M.; Writing—original draft, M.M.M.M.; Writing—review and editing, A.S.A.-M.; Visualization, M.M.M.M.; Supervision, K.S.S.; Funding acquisition, A.S.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2601).

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- U.S. Department of Justice. HIV and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section. 2017. Available online: https://archive.ada.gov/hiv/ada_qa_hiv.htm (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mitra, S.; Posarac, A.; Vick, B. Disability and poverty in developing countries: A multidimensional study. World Dev. 2013, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groce, N.E. Global disability: An emerging issue. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e724–e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.T.; Wang, J.W. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. A new class of weighted exponential distributions. Statistics 2009, 43, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, M.K. A two-parameter of weighted exponential distributions. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2012, 82, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.Y.; Arshad, I.A.; Aslam, M. Bayesian inference for the randomly censored Burr-type XII distribution. J. Appl. Stat. 2018, 45, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, G.; Berger, R.L. Statistical Inference, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.H.; Sultan, K.S.; Mansour, M.M.M. Unified hybrid censoring samples from Power Pratibha distribution and its applications. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap, and Other Resampling Plans; Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics CBMS-NSF Monographs; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Piao, J.; Ning, J.; Shen, Y. Conformal predictive intervals in survival analysis: A resampling approach. Biometrics 2025, 81, ujaf063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Luhayb, A.S.M.; Coolen, F.P.A.; Coolen-Maturi, T. Smoothed bootstrap for right-censored data. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2023, 53, 4037–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, R.; Pulcini, G. An engineering approach to Bayes estimation for the Weibull distribution. Microelectron. Reliab. 1994, 34, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, A.H.; Teller, E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, W.K. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.