Abstract

Image inpainting, a pivotal technology for restoring damaged regions of images, has emerged as a significant research focus in computer vision. This review systematically surveys recent advances in deep learning-based image inpainting. We begin by categorizing prevailing methods into three groups based on their core architectures: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Generative Models, and Transformers. Through a comparative analysis of their symmetric versus asymmetric network architectures, applicable scenarios, and performance bottlenecks, we provide a critical discussion of the strengths and limitations inherent to each approach. The evolution of underlying design principles, such as symmetry, and the corresponding solutions to core challenges are also discussed. Furthermore, we introduce key benchmark datasets and commonly used image quality assessment metrics, offering a multidimensional framework for evaluation. We highlight that mainstream datasets collectively foster a greenhouse-like evaluation environment detached from real-world complexities and that existing metrics are critically misaligned with the fundamental objective of inpainting: generating plausible new content. Finally, we summarize the prevailing challenges in current deep learning-based inpainting research and outline promising future directions. We highlight critical issues, such as enhancing restoration quality, reducing computational costs, and broadening application scenarios, thereby providing valuable insights for subsequent research.

1. Introduction

The technique of image inpainting originated in the art world for the manual restoration of damaged paintings, with its core principle being to reconstruct missing regions by interpolating information from adjacent areas. The application scenarios for image inpainting technology are remarkably broad, encompassing diverse fields such as cultural relic restoration [1], rectangular block occlusion removal, irregular occlusion removal, text erasure, object removal [2], image denoising [3], image dehazing [4], watermark removal [5], and old photograph restoration [6]. With the rapid advancement of computer vision, image inpainting has been formally defined as the process of reconstructing missing or corrupted parts of an image based on known pixel information, with the goal of achieving a seamless and natural-looking restoration. Consequently, its application scope has broadened significantly, spanning from cultural heritage preservation to everyday photo editing. Traditional image inpainting methods primarily relied on techniques such as Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) [7] and exemplar-based matching [8]. These approaches demonstrated efficacy in handling small-area defects. However, they often reached limitations when confronted with large missing regions or complex semantic scenes, failing to capture the underlying semantic features of an image effectively. In recent years, deep learning-based image inpainting methods have emerged. By leveraging deep neural networks to learn and model high-level semantic features of images, these methods have substantially improved inpainting performance. This progress is particularly pronounced in handling large missing areas, marking a new chapter in the field.

Existing surveys have made valuable contributions by summarizing specific periods or technical branches, such as reviews of traditional methods [9], specialized summaries of CNN- and GAN-based approaches [10], or dedicated assessments of emerging architectures such as Transformers [11]. Additionally, Xu et al. [12] reviewed deep learning-based inpainting methods from three perspectives: components, network architectures, and training optimization, comparing their performance on public datasets in scenarios such as object removal, general inpainting, and face restoration. Zhang et al. [13] provided an in-depth analysis of existing methods based on neural network structures and information fusion strategies, categorizing inpainting tasks according to application scenarios. Quan et al. [14] systematically surveyed deep learning-based image and video inpainting, offering a classification and performance evaluation across dimensions, including the inpainting pipeline, mainstream architectures, module designs, training objectives, datasets, and evaluation metrics. Yang et al. [15] categorized and analyzed deep learning inpainting models from the dimensions of model strategies, loss functions, evaluation metrics, and application domains.

While these existing reviews offer significant value in systematic summarization, there remains room for improvement in the timely coverage of frontier paradigms, the depth of critical analysis, and the provision of practical guidance regarding evaluation frameworks. The field urgently requires a survey with a more comprehensive perspective, more critical analysis, and the ability to keep pace with technological frontiers.

Therefore, this review systematically examines deep learning-based image inpainting methods. We categorize them according to their core network architectures—CNN-based, generative model-based, Transformer-based, and diffusion model-based approaches—and provide a critical analysis of the evolution, representative works from 2021 to 2025, and technical characteristics of each category. Concurrently, we outline key datasets, including those for masks, natural images, artistic images, and detection-related images, as well as the characteristics and applicable scopes of image quality assessment metrics ranging from PSNR and SSIM to LPIPS and NIQE. Furthermore, the article highlights current challenges in semantic understanding, joint texture–structure restoration, the application of diffusion models, high-resolution inpainting efficiency, dataset construction, and evaluation mechanisms. It also offers an outlook on future research directions, aiming to provide a more comprehensive and profound perspective for subsequent studies. The unique contributions of this article are as follows:

- An integrative perspective is provided across methodological evolution, introducing unified design principles (e.g., symmetry) underlying technological development and the evolution of solutions to core challenges.

- A precise alignment analysis framework is constructed linking inpainting challenges to model mechanisms, thereby enhancing the review’s practical utility.

- A more diagnostic evaluation perspective oriented toward the open world is advocated for and preliminarily constructed, promoting the field’s development toward robust and practical applications.

2. Deep Learning-Based Inpainting Methods

In 2006, Hinton et al. [16] pioneered the concept of deep learning in a seminal Science paper. They posited that artificial neural networks with multiple hidden layers possess exceptional feature learning capabilities, enabling them to effectively extract salient features from data, thereby facilitating data visualization and classification. Subsequent research advancements have led to the emergence of numerous key technologies, including Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) [17], Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [18], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [19], and the Transformer [20] architecture. These innovations have become foundational pillars across diverse fields such as computer vision, natural language processing, speech recognition, and bioinformatics, driving significant progress in practical applications such as facial recognition, cross-lingual translation, gene sequencing, and autonomous driving.

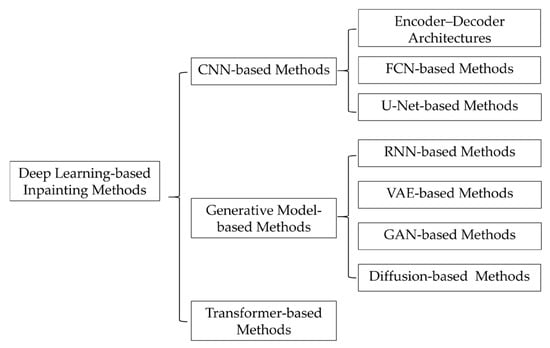

Within the domain of image inpainting, deep learning methods have substantially enhanced restoration quality by incorporating various constraints into deep models. Several deep learning architectures, notably Autoencoders [21], U-Net [22], Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [23], and Transformers [20], have demonstrated remarkable performance in this task. By training these deep networks, models can effectively capture high-level semantic information and learn intricate image structures and textures, enabling the plausible reconstruction of large missing regions. Compared with traditional inpainting approaches, deep learning models overcome critical limitations in handling complex image corruptions and high-resolution restoration, yielding significantly more precise and natural-looking results. Consequently, deep learning-based inpainting holds considerable promise in modern computer vision, offering novel and effective solutions for addressing the challenge of large-area reconstruction. Based on their core network architecture, deep learning-based image inpainting methods can be categorized as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of deep learning-based image inpainting methods.

2.1. CNN-Based Methods

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) represent a powerful class of neural networks specifically designed for image data processing. First introduced by LeCun et al. [18] and inspired by biological visual systems, CNNs were successfully applied to handwritten digit recognition. By integrating convolutional and pooling operations, they heralded a new era in deep learning. A pivotal breakthrough came in 2012 when Hinton and his students [24] demonstrated the immense potential of deep learning through the groundbreaking success of AlexNet in image classification. Since then, CNNs have been extensively applied across various computer vision domains, including object detection and semantic segmentation. Consequently, CNN-based models have become a dominant paradigm for image inpainting. The core architecture of a CNN typically comprises convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and classifiers. This foundational structure has accelerated the rapid development of image inpainting technologies in numerous applications. Based on specific architectural designs, CNN-based inpainting methods can be primarily categorized into encoder–decoder models, Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) models, and U-Net-like architectures.

2.1.1. Encoder–Decoder Architectures

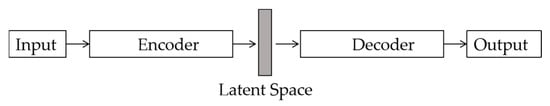

The Encoder–Decoder (E–D) architecture stands as a cornerstone model in deep learning and has achieved remarkable progress in the field of image inpainting. In this framework, an encoder first extracts features from the input image and compresses them into a latent space representation. Subsequently, a decoder utilizes these features to reconstruct the corrupted image (Figure 2). The primary strength of this architecture lies in its ability to effectively capture information from the known regions of an image and leverage it to reconstruct the missing parts through a relatively streamlined structure, yielding superior performance in inpainting tasks.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of an encoder–decoder architecture.

Introduced in 2016, the Context Encoder (CE) model [25] stands as a classic example of the encoder–decoder framework. This model integrates unsupervised learning with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), generating restored content by leveraging contextual information from the regions surrounding the missing area. The Context Encoder employs a combined reconstruction and adversarial loss function, which significantly enhances the quality and flexibility of the generated images. However, a notable limitation of the CE model is its tendency to produce discontinuities and structural inconsistencies between the inpainted and intact regions. To address this issue, Iizuka et al. [26] proposed the Globally and Locally Consistent Image Completion (GLCIC) model, which incorporates both global and local discriminators to substantially improve the coherence of inpainted results.

Technological advancements have since spurred the development of numerous variants and innovative methods. For instance, Yeh et al. [27] introduced a deep generative model that optimizes semantic inpainting by searching for the nearest encoding representation in the latent space. Zhang et al. [28] proposed StackGAN, which enhances output quality through a two-stage inpainting process. Wang et al. [29] developed GMCNN, which utilizes a Multi-Column CNN (MC-CNN) to capture image features at different scales and receptive fields, thereby improving the diversity and accuracy of the restoration. Further refinements have been achieved by incorporating edge-aware context decoders and semantic segmentation information, which enhance detail and structural consistency. Yu et al. [30] advanced the field with gated convolutions and a parallel decoding network (PEPSI) [31], accelerating the inpainting process while improving precision. More recently, He et al. [32] presented the Masked Autoencoder (MAE), which combines a Transformer architecture with the encoder–decoder framework, promoting the application of self-supervised learning in inpainting and pushing its technical boundaries. Subsequent studies continue to refine this core architecture.

Li et al. [33] proposed the MISF framework, which employs multi-level interactive dynamic filter prediction for high-fidelity inpainting. Zhao et al. [34] introduced TransCNN-HAE, a lightweight and efficient model for blind image inpainting that utilizes a Transformer encoder coupled with a CNN decoder. Liu et al. [35] developed CoordFill, a model that achieves efficient high-resolution inpainting through restorative feature synthesis and per-pixel coordinate querying. Kumar et al. [36] presented a hybrid encoder–decoder architecture, incorporating a sub-module derived from the DenseNet-121 structure as its encoder. Lian et al. [37] designed a dual-encoder framework guided by structural and texture features and incorporated a multi-scale receptive field to further enhance semantic coherence and fine-grained detail. Zhang et al. [38] proposed a multi-stage decoding network (MSDN) that leverages multiple decoders to decode and integrate features from each layer of the encoding stage, thereby improving the utilization of encoder features across different scales. Hu et al. [39] introduced the ClusIR model, which employs a probabilistic cluster-guided routing module (PCGRM) and a degradation-aware frequency-domain modulation module (DAFMM) to decouple degradation identification from expert activation and optimize frequency-domain synergy.

In summary, the encoder–decoder (E-D) architecture serves as the foundational paradigm for deep learning-based image inpainting. Its evolution, from the initial Context Encoder to innovations incorporating attention mechanisms, multi-scale processing, and separate structural–textural encoding, has centered on refining feature extraction and utilization to enhance semantic consistency and detail quality. However, this approach has inherent limitations. Its serial “encode-then-decode” pipeline is prone to information loss during feature transmission, particularly for large missing regions where maintaining long-range structural coherence is challenging. Furthermore, the decoder’s performance is heavily reliant on the contextual features provided by the encoder. When sufficient, valid context is unavailable within the missing region, and the decoder’s generative and creative capacity is constrained, often necessitating the integration of external generative priors, such as those from GANs or Transformers, to compensate.

2.1.2. FCN-Based Methods

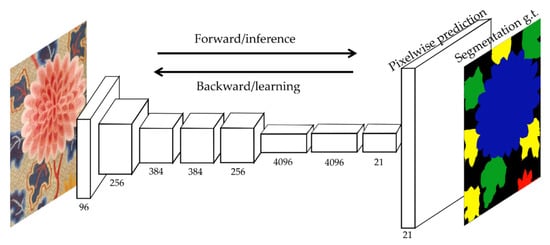

Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs), first proposed by Long et al. [40] in 2015 for semantic segmentation, replace the fully connected layers of traditional CNNs with deconvolutional layers. This enables upsampling of the input image, producing an output identical in size to the original (Figure 3). This characteristic has led to their widespread adoption in image inpainting [41]. In an FCN, the final convolutional layer generates a high-dimensional feature map, which is then fed into deconvolutional layers for upsampling to reconstruct the final image. In this setup, the convolutional layers act as an encoder for feature extraction and denoising, while the deconvolutional layers serve as a decoder for image reconstruction.

Figure 3.

Schematic of a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) architecture, which efficiently learns to perform dense prediction for pixel-wise tasks such as semantic segmentation.

In 2017, Yang et al. [42] introduced a multi-scale neural patch synthesis approach, which harmoniously updates feature patches in the intermediate layers of a deep classification network. This method successfully preserves the contextual structure of the image and generates sharper, more coherent high-resolution inpainting results, underscoring the FCN’s efficacy in capturing global structure and semantics. Further innovations followed. Godard et al. [43] proposed a recurrent fully convolutional deep neural network functioning as a “feature accumulator,” a framework that also exhibits excellent generalization for image super-resolution. Song et al. [44] proposed the Segmentation Prediction and Guidance Network (SPG-Net), which leverages segmentation information to improve boundary recovery and texture consistency in the inpainted image, enabling multimodal inpainting and significantly enhancing output quality. More recent work continues to refine FCNs. Xiao et al. [45] presented a High-Pass Filter Attention Fully Convolutional Network (HPA-FCN), incorporating Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks and applying parallel spatial and channel attention during feature extraction to augment the information gleaned. Channel attention was also introduced in the upsampling stage to boost detection and localization capabilities. Dong et al. [46] developed a Residual Low-Pass Filter (RLPF) module that employs a standard FCN with residual learning to model high-frequency information, while utilizing a learnable low-pass filter based on a self-attention mechanism to model low-frequency information.

Thus, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) achieve efficient, end-to-end pixel-level prediction owing to their fully convolutional nature. Their evolution, through the introduction of strategies such as multi-scale patch synthesis, attention mechanisms, and residual filtering, has enhanced feature extraction and contextual modeling capabilities, thereby improving high-resolution inpainting performance. The core limitation of this approach, however, lies in its fundamental reliance on stacking local operations. This inherently restricts its capacity for explicit modeling of long-range semantic dependencies and complex global structures within an image, making it difficult to ensure semantic coherence when inpainting large missing regions. Furthermore, its performance heavily depends on manually designed multi-scale and attention modules to compensate for insufficient receptive fields—a reliance that stems more from incremental engineering than from foundational architectural innovation. Consequently, this often results in complex model designs with limited interpretability.

2.1.3. U-Net-Based Methods

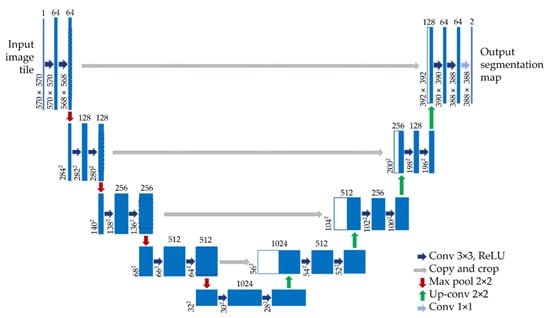

The U-Net architecture was first introduced by Ronneberger et al. [22] for biomedical image segmentation and has rapidly become a cornerstone method in image inpainting. Its core strength lies in the efficient fusion of multi-scale, low-level features (e.g., color, edges) with high-level semantic features (e.g., texture, object parts), providing powerful representational capabilities for the task. The U-Net architecture consists of two symmetrical core components: a contracting path (encoder) that extracts multi-scale features through convolutional and pooling layers, and an expanding path (decoder) that progressively restores spatial resolution. Critically, skip connections fuse features from the encoder directly to the corresponding decoder layers, ensuring that the final output maintains consistency in both fine-grained details and broader contextual continuity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic of the U-Net architecture. Each blue box corresponds to a multi-channel feature map, with the number of channels indicated at the top of the elongated box. The x–y dimensions are provided at the lower left edge of each box. White boxes represent copied feature maps, and arrows denote different operations.

The powerful capabilities of U-Net have spurred numerous enhanced designs to further boost its performance in complex inpainting tasks. For instance, Yan et al. [47] introduced Shift-Net, which incorporates shift-connection layers into the U-Net structure to significantly improve the restoration of complex structures and fine-grained textures. Liu et al. [48] proposed the use of partial convolutions to replace standard convolutional layers in U-Net, combined with nearest-neighbor upsampling, effectively enhancing its capability to handle irregular missing regions. Wang et al. [49] developed a multi-scale attention module that augments the fusion of low-level details and high-level semantic information, thereby elevating inpainting quality. Zeng et al. [50] presented a Pyramid-context Encoder Network (PEN-Net), which ensures both visual and semantic consistency during inpainting through the encoding and decoding of contextual semantics. Hong et al. [51] proposed DFNet, which embeds multiple fusion modules within the U-Net decoder to effectively eliminate discontinuities between missing and intact areas. For high-resolution inpainting, Yi et al. [52] introduced an approach that aggregates weighted contextual residual samples, repairing details through multi-scale high-frequency residual aggregation and further enhancing results with an attention module.

The evolution of U-Net continues to address more complex challenges. For example, Shamsolmoali et al. [53] combined convolutional and Transformer mechanisms within a U-Net-like framework, optimizing image content representation for more comprehensive and robust inpainting. Wang et al. [54] proposed ISFRNet, which integrates a pre-trained generative model with an enhanced U-Net architecture to improve the quality and authenticity of facial image inpainting. Suvorov et al. [55] introduced LaMa, a novel image completion model built upon U-Net that utilizes Fast Fourier Convolutions (FFCs) to capture global context at an early stage, markedly improving performance on large missing areas. Zhang et al. [56] designed a mutual dual-task generator that models the interdependency between image texture and semantic segmentation, achieving superior semantics-guided inpainting.

Hou et al. [57] proposed SC-Unet, a symmetric U-Net-based model for image inpainting enhanced with a Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN). The model integrates dilated convolutions and a multi-head self-attention mechanism, achieving superior performance in reconstructing missing image regions. Zhao et al. [58] introduced the CAML model, which employs context-aware mutual learning to jointly perform mask estimation and inpainting. This approach delivers blind inpainting performance close to state-of-the-art (SOTA) results and demonstrates easy extensibility to other tasks. Chen et al. [59] developed SEM-Net, which incorporates a state space model (SSM) for pixel-level image inpainting and features spatially enhanced perception. Jiao et al. [60] presented SymUNet, a symmetric U-Net equipped with skip connections and bidirectional semantic guidance. This architecture offers advantages including a concise structure, strong generalization, stable training, and computational efficiency; however, it does not fully leverage external prior knowledge.

In summary, U-Net, with its distinctive symmetric encoder–decoder architecture and skip connections, has established itself as a core paradigm in image inpainting. By efficiently fusing multi-scale features, it has significantly improved the detail coherence and semantic consistency of inpainted results. Subsequent research has continuously expanded its capabilities—addressing irregular holes, large missing regions, and multi-task generalization—through innovations such as partial convolutions, attention mechanisms, Fourier convolutions, and task-specific prompting. The fundamental limitation of this approach, however, lies in its foundational reliance on local convolutional operations. This creates an inherent constraint in modeling long-range global dependencies and complex semantic relationships within images. Consequently, most recent advancements have depended on external integration with non-local architectures, such as Transformers or diffusion models, rather than on breakthroughs within the U-Net architecture itself.

2.1.4. Summary of CNN-Based Methods

The development trajectory of CNN-based image inpainting methods has consistently centered on mitigating the inherent limitations of standard convolutions in modeling long-range dependencies and global semantic relationships. Innovations such as attention mechanisms, multi-scale feature fusion, and Fourier convolutions have progressively enhanced their ability to handle irregular holes, complex structures, and exceptionally large missing regions. This evolutionary path, however, also underscores the fundamental constraints of the CNN paradigm. While its inductive bias, rooted in local connectivity, excels at feature extraction, it inherently struggles to model long-range semantic associations within an image and to generate highly creative content. Consequently, achieving state-of-the-art performance frequently necessitates integration with external generative paradigms, such as GANs, Transformers, and diffusion models. The current research landscape suggests that optimizing CNN architectures in isolation is approaching its performance ceiling. The field’s focus is therefore shifting from refining CNNs to exploring multi-architecture fusion. This transition signifies a critical juncture for image inpainting, moving beyond the local perspective of convolution toward a new stage characterized by more powerful global modeling and generative capabilities.

2.2. Generative Model-Based Inpainting Methods

Generative model-based inpainting methods reconstruct missing regions by inferring the prior distribution of the corrupted image. Broadly speaking, these methods have evolved upon the foundations of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Diffusion models, and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), collectively driving the advancement of inpainting technology.

2.2.1. RNN-Based Methods

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [19] are models capable of capturing dependencies between outputs and previous inputs through parameter sharing. The output of an RNN depends not only on the current input but also on a “memory” of previous time steps, making them effective for modeling correlations in sequential data. When applied to image inpainting, RNNs can model spatial relationships between pixels, leveraging contextual information to restore images. However, as the inpainting process advances, the connections between distant pixels diminish, leading to low efficiency, especially for large missing areas. Furthermore, traversing all global pixels increases computational complexity, often resulting in inferior performance compared with Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based approaches.

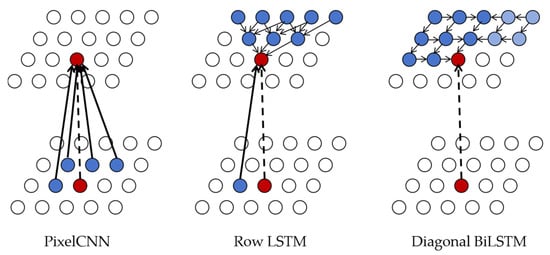

To address these limitations, Van Oord et al. [61] introduced the PixelRNN model, which integrates two-dimensional RNNs with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layers [62]. This architecture effectively models both global and local pixel dependencies, thereby improving inpainting quality. However, the model still faces challenges due to high computational complexity when applied to high-resolution images. To mitigate this, subsequent architectures such as Row LSTM and Diagonal BiLSTM were proposed. The former enhances training speed through parallelization, while the latter optimizes the shape of the receptive field to better capture contextual information. Despite these improvements, challenges persist in processing high-resolution images, particularly in modeling the relationships between color channels. The PixelCNN model [63] further refined PixelRNN by incorporating masked convolutional layers. This modification restricts the context for generating each pixel to only the left and top pixels, thereby accelerating the generation process (Figure 5). Salimans et al. [64] subsequently proposed PixelCNN++, which significantly boosts training speed and the efficiency of high-resolution image generation through a discretized logistic mixture likelihood and other modifications. In a more recent approach, Chen et al. [65] developed a Multi-Level Generative Chaotic Recurrent Neural Network for image inpainting. This technique employs a unified framework that combines multiple chaotic RNNs, enabling more robust and efficient learning of image priors from a single corrupted image. The method utilizes a randomly initialized parameterization process, equipped with a unique four-directional encoder structure, chaotic state transitions, and adaptive importance sampling to update the multi-level RNNs.

Figure 5.

Schematic visualization of the input-state and state-state mappings for three RNN architectures.

In summary, RNN-based image inpainting approaches frame image generation as a sequence prediction problem. By employing autoregressive modeling to capture strict dependencies between pixels, they achieve precise probabilistic modeling in theory. The fundamental flaw of this approach, however, stems from its sequential generation nature, which inherently prohibits parallel computation. This results in prohibitively high computational complexity and low efficiency when processing high-resolution images. Moreover, the pixel-by-pixel generation process struggles to effectively capture the global semantic structure and long-range contextual information of an image, leading to suboptimal performance in inpainting large missing regions. Consequently, these methods have largely been superseded by more efficient generative paradigms, such as VAEs, GANs, and diffusion models.

2.2.2. VAE-Based Methods

The Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [66] is a deep generative model composed of an encoder and a decoder, designed to model the latent space probabilistically (Figure 6). Unlike traditional autoencoders, which focus solely on reconstructing input data, the VAE introduces a prior distribution (typically Gaussian) over the latent representations. This key innovation enhances the diversity and realism of the generated data. The training objective of a VAE is to maximize the likelihood of the observed data while minimizing the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the latent representations and the chosen prior distribution.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the standard Variational Autoencoder (VAE) model structure.

Within image inpainting, VAE-based approaches have been extensively explored. Zheng et al. [67] proposed a pluralistic image completion framework featuring a dual-branch network. In this design, a reconstruction branch models the prior distribution of the missing parts, while a generation branch infers the latent conditional prior distribution for the missing regions. Han et al. [68] decomposed the inpainting process into shape and appearance generation, employing a VAE-based network to achieve both compatible and diverse fashion image inpainting. Tu et al. [69] leveraged a pre-trained VAE to search for plausible solutions for corrupted images within the encoded vector space, ensuring robust predictions for the missing areas. Further advancements include the work of Peng et al. [70], who designed a two-stage pipeline: the first stage employs a Hierarchical Vector-Quantized VAE (VQ-VAE) to generate multiple coarse results with diverse structures, and the second stage synthesizes detailed textures upon these. Razavi et al. [71] extended VQ-VAE by enhancing the autoregressive prior with simple feedforward encoder and decoder networks, improving the consistency and fidelity of generated samples. Most recently, Wang et al. [2] introduced a post-processing technique named ASUKA (Alignment-Stable inpainting with Unknown region priors) to mitigate unwanted object insertion. This method utilizes a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) to provide reconstruction-based priors, reducing object hallucinations while preserving the model’s generative capacity. To address color inconsistency, they designed a dedicated VAE decoder that treats the latent-space-to-image decoding as a local harmonization task, significantly reducing color shifts and achieving color-consistent inpainting.

VAE-based image inpainting methods introduce a continuous latent variable space, providing a probabilistic foundation for diverse inpainting outcomes. Their evolution has focused on improving latent variable representations to enhance generative controllability and achieve structure–texture disentanglement. This approach, however, suffers from fundamental limitations. The constraint imposed by the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence term in its training objective can easily lead to posterior collapse, causing the model to generate blurry and detail-deficient results with notably weaker visual realism compared with adversarial generative methods. Furthermore, its generation process lacks an iterative refinement mechanism akin to that of diffusion models, limiting its capacity to produce high-fidelity textures and complex structures. Consequently, VAE-based methods often require integration with other paradigms, such as GANs or Transformers, to bridge the quality gap.

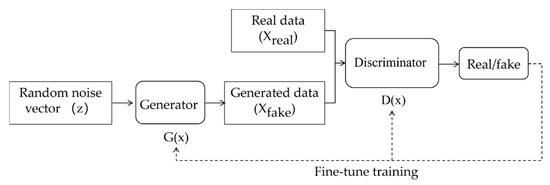

2.2.3. GAN-Based Methods

Since their introduction in 2014 by Goodfellow et al. [23], Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have become a cornerstone of image inpainting. The adversarial training process between a generator and a discriminator enables GANs to produce highly realistic inpainted results (Figure 7). For instance, Li et al. [72] developed a method combining a Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) with an improved GoogLeNet for restoring occluded offline handwritten Chinese characters, demonstrating notable performance in complex inpainting tasks. Shin et al. [73] proposed PEPSI++, a fast and lightweight GAN-based network that maintains high-quality results while significantly improving inpainting efficiency.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the standard Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) model structure.

In the realms of inpainting diversity generation, Zhao et al. [74] proposed the unsupervised cross-space translation model UCTGAN, which enhances output diversity for a single corrupted image by generating multiple plausible results. Within medical image inpainting, Armanious et al. [75] developed MedGAN, which integrates a patch-based discriminator with a style loss function, demonstrating superior performance on medical modalities such as CT and MRI compared with methods designed for natural images. Chai et al. [76] proposed an Edge-Guided GAN (EG-GAN) for brain MRI restoration, showing excellent capability in recovering fine details and structural similarity. Other notable advancements include the CVAE-GAN by Bao et al. [77], which combines an encoder, generator, classifier, and discriminator to optimize inpainting under complex scenes. Karras et al. [78] improved the image quality and stability of generated results with StyleGAN2 by refining the mapping between latent codes and images in a progressive growing framework. Liu et al. [79] proposed PD-GAN, which enhances output diversity through a Spatial Probability Diversity Normalization module. Gao et al. [80] presented a face inpainting method using a GAN with global and local discriminators and improved training stability via a weighted combination of mean squared error and adversarial loss, ultimately generating highly realistic images. Recent work continues to expand GAN applications. Guo et al. [81] proposed the CTSDG model, which incorporates bidirectional gated feature fusion (Bi-GFF) and contextual feature aggregation (CFA) modules to achieve synergistic structure–texture restoration and robust contextual modeling. More recently, Chen et al. [82] introduced SafePaint, a method for anti-forensic image inpainting utilizing domain adaptation techniques. Xie et al. [83] developed TurboFill, a triple-component inpainting framework based on fast and slow generators designed to enhance the repair capability of adapters while improving the quality of inpainted regions. Li et al. [84] proposed the STNet model, which employs a three-stage pipeline for structure decomposition, texture restoration, and refinement. This process offers strong interpretability but incurs substantial computational costs and requires external pre-processing. Zhang et al. [85] introduced the MMInvertFill model, which leverages a multimodal guidance encoder (MGE) for latent space manipulation. It excels in large-area inpainting and out-of-domain generalization but suffers from high training complexity.

In summary, GAN-based image inpainting methods, through the adversarial training of a generator against a discriminator, have achieved a milestone breakthrough in the visual realism of generated images. Their evolution has expanded from enhancing basic architectural stability to enabling diverse generation, multimodal guidance, and precise inpainting for specific domains (e.g., medical imaging, anti-forensics). This paradigm, however, is fundamentally constrained. Its adversarial training process is inherently unstable, often leading to mode collapse and convergence difficulties. Furthermore, the lack of an explicit probabilistic model and likelihood function presents significant challenges in controlling generation diversity, assessing sample quality, and performing interpretable editing in the latent space. These limitations are driving current research increasingly toward utilizing pre-trained GANs for inversion or integrating them with more stable paradigms, such as diffusion models.

2.2.4. Diffusion-Based Methods

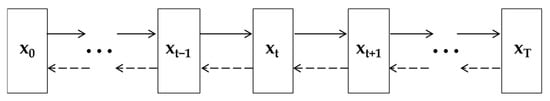

The theoretical foundation of diffusion models can be traced back to the non-equilibrium thermodynamics framework proposed by Jascha et al. in 2015 [86]. However, it was through subsequent pivotal work—notably the noise-conditioned score network (NCSN) introduced by Song et al. in 2019 [87] and the denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) by Ho et al. in 2020 [88]—that this, field underwent systematic formulation and achieved significant performance breakthroughs. Together, these studies established the core technical groundwork for modern diffusion-based generative modeling. By formalizing a forward noise-adding process and a reverse denoising process (Figure 8), they successfully enabled learning complex data distributions from random noise, thereby laying the theoretical and practical cornerstone for contemporary diffusion models.

Figure 8.

Schematic of the forward noising and reverse denoising processes in diffusion models. The forward diffusion process is fixed and does not require learning. It progressively adds a small amount of Gaussian noise to the original data, x0, over multiple steps. In the reverse generative process, given a noisy image xt at timestep t, the model is tasked with predicting the noise added at this step or directly estimating the denoised image xt−1. The process iterates until t = 0, yielding the final, clean generated image x0.

Diffusion-based image inpainting represents the current frontier in the field. Its core strength lies in leveraging a progressive denoising generative paradigm, which surpasses traditional generative models in ensuring global semantic consistency and delivering high-quality results. Current research breakthroughs primarily address two major challenges. First, by introducing structural guidance or designing dual-branch architectures, researchers aim to bridge the semantic gap between masked regions and known contexts, thereby enhancing the plausibility and harmony of the inpainted content. Second, strategies such as constructing short Markov chains, employing efficient sequence modeling modules, or adopting test-time training are being developed to significantly optimize the iterative sampling process, addressing the inherent computational efficiency bottleneck of diffusion models. For example, Ju et al. [89] proposed BrushNet, a novel plug-and-play dual-branch model that embeds masked image features into the diffusion framework via an auxiliary branch to ensure output consistency. Yue et al. [90] developed an efficient diffusion model that establishes a short Markov chain to enhance both the speed and performance of image inpainting, successfully resolving the trade-off between perceptual quality and distortion. Zhuang et al. [91] presented PowerPaint, a high-quality and versatile inpainting model that incorporates learnable task prompts and fine-tuning strategies, demonstrating excellent performance across diverse inpainting tasks. Xue et al. [92] proposed CycleRDM, which employs a three-stage diffusion inference process for gradual optimization and incorporates a feature gain module with multimodal-driven appearance reconstruction to improve inpainting stability. Liu et al. [93] proposed StrDiffusion, which uses structure-guided texture diffusion and adaptive re-sampling to significantly alleviate semantic discrepancies, albeit with high training complexity and slow inference. Lu et al. [94] introduced the DiffRWKVIR framework, which integrates a diffusion mechanism to enhance computational efficiency and quality in super-resolution and image inpainting tasks.

In summary, diffusion-based inpainting methods have set a new benchmark for the field regarding generation quality, diversity, and global consistency through their rigorous, progressive denoising paradigm. Current research is intensely focused on optimizing semantic consistency via structural guidance and overcoming computational bottlenecks through accelerated sampling strategies. However, this approach is fundamentally constrained by the high computational cost and slow inference speed inherent to its multi-step iterative sampling process, severely limiting real-time applications. Moreover, it exhibits strong reliance on the accuracy of conditional guidance information (e.g., structural maps) when handling complex defects, while precise control over the generation process remains challenging, often leading to semantic ambiguity or detail distortion.

2.2.5. Summary of Generative Model-Based Methods

Among generative model-based image inpainting methods, RNN-based approaches offer theoretical rigor but suffer from prohibitive computational inefficiency. VAEs provide a framework for diverse inpainting yet sacrifice output sharpness. GANs achieved a breakthrough in visual realism, but their fundamental flaws—training instability and mode collapse—prove difficult to overcome. Presently, diffusion models have emerged as the dominant paradigm by virtue of their optimal balance between generation quality, diversity, and stability. Research in this area is now intensely focused on addressing two core challenges: semantic consistency constraint and inference efficiency optimization. Examining this evolution reveals a deeper paradigm shift: GANs and VAEs are increasingly transitioning from stand-alone solutions to serving as embedded “prior components” within larger systems, while diffusion models have ascended as the foundational base for a new generation of generative inpainting. The key to future breakthroughs lies in constructing novel architectures that achieve a balanced trade-off between perception, distortion, and efficiency, while also developing highly efficient and controllable generation techniques. This dual pursuit will be crucial to advance the field from an academic benchmark toward practical, real-world application.

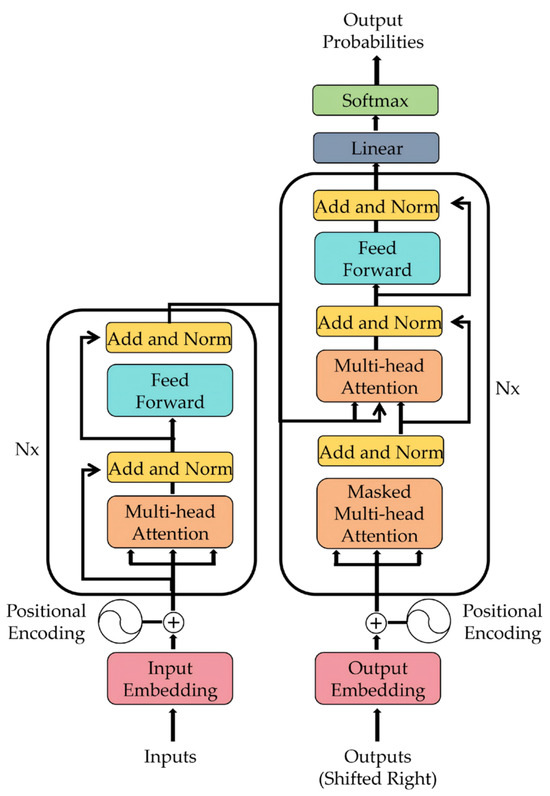

2.3. Transformer-Based Methods

Originally introduced by Vaswani et al. [20] for natural language processing (NLP), the Transformer model has become a powerful tool in computer vision. Unlike traditional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the Transformer utilizes a self-attention mechanism to effectively capture global dependencies within a sequence, overcoming issues such as vanishing gradients that plague long-sequence modeling. This innovation has led to significant success across various tasks, particularly in image inpainting, where it demonstrates superior capability in restoring complex structures and fine details. The core Transformer architecture comprises an encoder and a decoder, each consisting of multiple self-attention layers and feed-forward neural networks. The self-attention mechanism allows the model to assess relationships between all positions in the sequence. When applied to images, this enables the modeling of global context, overcoming the locality constraint inherent in CNNs (Figure 9). Consequently, Transformers are exceptionally well-suited for inpainting large missing regions, as they can meticulously model dependencies for each pixel position.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the Transformer model architecture.

Many researchers have adapted Transformers for inpainting. For instance, Zhou et al. [95] proposed TransFill, which merges multiple color and spatial transformations to inpaint complex scenes, successfully addressing color matching and disparity issues. Wan et al. [96] introduced a high-fidelity pluralistic image completion method that combines a Transformer for recovering the global image structure with a CNN for enhancing local details. Wang et al. [97] developed FT-TDR, a frequency-guided Transformer and top-down refinement network focused on blind face inpainting. Cao et al. [98] integrated a Vision Transformer (ViT) with a masked autoencoder, leveraging attention to handle long-range dependencies between corrupted and uncorrupted regions, significantly improving results. Dong et al. [99] proposed ZITS, which incorporates masking positional encoding and a Fourier CNN texture restoration module to boost performance on images with large missing areas.

Multimodal and multi-scale Transformer approaches have also gained traction. Yu et al. [100] proposed BAT-Fill, which models the autoregressive distribution using a bidirectional autoregressive Transformer to enhance inpainting performance. Li et al. [101] introduced the Mask-Aware Transformer (MAT), the first Transformer-based framework capable of directly processing high-resolution images, employing a multi-head context attention block to efficiently model long-range dependencies. Despite their advantages, Transformers demand substantial computational resources, and processing large images can lead to prohibitive inference time and memory usage. To address this, several optimized solutions have emerged. Chen et al. [102] proposed a lightweight Stripe Window Transformer that incorporates CNN features to improve efficiency. Naderi et al. [103] employed a Swin Transformer to enhance efficiency and balance global and local features. More recently, Ko et al. [104] proposed CMT, which employs a two-stage inpainting framework and uses masked self-attention that is amenable to irregular mask updates; however, it incurs substantial computational overhead and does not achieve fully blind inpainting. Phutke et al. [105] introduced OmniWavNet, which leverages wavelet query attention and omni-dimensional gated attention mechanisms to accomplish blind inpainting. Liu et al. [106] developed the PUT framework, designing a patch-based autoencoder and incorporating semantic and structural conditions as additional guidance. Wan et al. [107] presented a method for high-fidelity and efficient pluralistic image completion, achieving, for the first time, an inference speed improvement exceeding 70×. He et al. [108] proposed Dabformer, a frequency-domain fusion Transformer model that integrates wavelet transforms with Gabor-filter-based attention to enhance multi-scale structural modeling and detail retention. Ning et al. [109] introduced CIOCR, which adopts a strategy of first restoring structure and then using that structure as a guide for texture restoration. This approach enhances inpainting quality through multi-scale feature fusion and dual-domain (spatial and frequency) feature enhancement.

In summary, Transformer-based image inpainting methods leverage their self-attention mechanism to demonstrate significant advantages in modeling long-range dependencies and enforcing global semantic consistency within images. They are particularly adept at handling large missing regions. Their evolution, through the incorporation of mask-awareness, frequency-domain guidance, and hybrid architectures, continuously refines performance and efficiency. The fundamental limitation of this approach, however, stems from the quadratic computational complexity of its self-attention mechanism with respect to input sequence length. This imposes prohibitive memory and computational costs when processing high-resolution images. Furthermore, these methods are relatively inefficient at capturing fine-grained local texture details. Consequently, state-of-the-art solutions predominantly rely on hybrid Transformer–CNN designs, a trend that underscores the inherent constraints of pure Transformer methods for dense pixel prediction tasks.

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Representative Methods

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the development trends in deep learning-based image inpainting and to compare the strengths and limitations of various models, we conducted a systematic comparative analysis of 19 models proposed between 2021 and 2025. The selected models are as follows: Encoder–Decoder (E-D)-based: MISF [33], TransCNN-HAE [34], CoordFill [35], ClusIR [39]; U-Net based: LaMa [55], CAML [58], SEM-Net [59], SymUNet [60]; GAN-based: CTSDG [81], STNet [84], MMInvertFill [85]; Transformer-based: CMT [104], OmniWavNet [105], PUT [106], CIOCR [109], Dabformer [108]; and diffusion-based: PowerPaint [91], StrDiffusion [93], DiffRWKVIR [94]. For quantitative evaluation, we compiled the performance metrics of 11 representative models on the Places2 dataset using irregular random masks, as detailed in Table 1. Furthermore, we provide a systematic summary of all 19 models, encompassing their core architectures, innovations, mechanisms, strengths, and limitations, which is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation of representative models on the Places2 dataset using irregular random masks. Results in bold and underlined denote the best and second best performance, respectively. † indicates a higher value is better, while ¶ indicates a lower value is better.

Table 2.

Summary of the core architecture, innovations, advantages, and limitations of representative models (2021–2025).

A comprehensive analysis of the data in Table 1 reveals significant disparities between different models regarding performance, efficiency, and robustness on the irregular mask inpainting task using the Places2 dataset. The CAML model demonstrates the best overall performance, particularly for medium (20–40%) and hard (40–60%) masking ratios. It achieves leading or excellent results across multiple metrics, including PSNR, SSIM, FID, and LPIPS, striking a favorable balance between restoration quality and perceptual effect. SEM-Net delivers optimal performance in areas with simple masks (0.01–20%), whereas TransCNN-HAE achieves remarkable parameter efficiency with a notably low parameter count (3 M) and computational cost (20 G FLOPs). The analysis indicates that model performance is not strictly correlated with parameter count or computational complexity. For instance, CMT, despite having 143 M parameters, does not exhibit outstanding performance. Furthermore, as the masking difficulty increases, the performance divergence between models intensifies, underscoring the critical importance of robustness in complex scenarios. Current technological trends suggest that successful inpainting models must achieve a balance between traditional fidelity metrics (PSNR/SSIM) and modern perceptual metrics (FID/LPIPS). Meanwhile, lightweight and efficient architectural design emerges as a key direction for future research.

As detailed in Table 2, the field of image inpainting has undergone significant paradigm evolution and technological convergence in recent years. Early models were predominantly based on GANs and U-Nets, focusing on modular innovations such as feature fusion. Subsequently, Transformers emerged as mainstream due to their superior long-range modeling capabilities, and their integration with frequency-domain analysis (e.g., wavelet, Fourier) enhanced detail recovery. In recent years, diffusion models have risen to prominence, distinguished by their exceptional generative quality. Concurrently, the research focus has shifted from mask-dependent inpainting toward more practical “blind” inpainting. The inpainting pipeline itself has become increasingly refined, giving rise to multi-stage, progressive approaches, as well as multimodal controllable methods guided by structural cues or task-specific prompts.

This survey reveals that models excelling at specific inpainting challenges derive their strengths from a precise alignment between their core design and the fundamental nature of the problem. For handling large missing regions, the key lies in global semantic comprehension and long-range structure generation. Architectures such as Transformers and diffusion models excel here. Transformers establish long-range dependencies between any pixels via self-attention, enabling the “borrowing” of plausible information from distant parts of the image. Diffusion models, by contrast, leverage their strong generative prior to synthesize coherent content consistent with the overall semantics through a gradual denoising process starting from noise. Addressing irregular masks demands high adaptability to unpredictable shape boundaries. Strategies employing progressive mask updating dynamically adjust the inpainting focus, while attention mechanisms based on content similarity naturally search for reference regions across irregular boundaries. Both approaches effectively reduce dependence on mask regularity. The central tension in processing high-resolution inputs is between computational efficiency and detail preservation. On one hand, models manage the explosion in complexity through hierarchical design and efficient computation, employing techniques such as coordinate querying, chunked processing, or linear-complexity architectures to significantly reduce memory and computational burden. On the other hand, to preserve high-frequency details, advanced models have turned to frequency-domain and multi-scale representations. Tools such as wavelet transforms and Gabor filters are used to explicitly separate and process edge-related high-frequency information that carries texture. Alternatively, within structure–texture separation frameworks, macroscopic structures are restored first, followed by the filling of microscopic textures, enabling high-fidelity detail reconstruction within a manageable computational budget.

Furthermore, we observe that many key architectural components incorporate principles of symmetry. The encoder–decoder structure exhibits strict mirror symmetry in both hierarchy and function, facilitating a balanced transition from comprehension to creation. Skip connections symmetrically compensate for detail loss during upsampling across spatial scales, ensuring balanced multi-scale feature fusion. The attention mechanism establishes dynamic, content-driven symmetric relationships, allowing information to flow non-locally and symmetrically between any known and unknown regions. Advanced masking techniques, such as continuous mask updating, embody a symmetry of exploration versus exploitation, dynamically balancing the boundary between known and unknown areas. This demonstrates how symmetry-informed design is guiding image inpainting away from purely data-driven pattern completion and toward more controllable and rational, prior-guided generative reasoning.

Finally, technological advancement is invariably accompanied by the navigation of core trade-offs. Current models commonly face difficult compromises between three factors: output quality, inference speed, and model complexity. Models that pursue high-fidelity detail, strong generalization, and high-resolution processing (e.g., diffusion models, complex Transformers) are often constrained by substantial computational costs and slow inference. Conversely, lightweight designs aimed at improving efficiency may sacrifice performance. Moreover, models specialized for specific domains (e.g., cultural relic restoration), while able to incorporate domain-specific priors, often do so at the expense of generalization ability. Looking forward, developing unified, lightweight frameworks that can balance generative quality, inference efficiency, and generalization, effectively extending the success of 2D inpainting to higher-dimensional data such as video, will be crucial.

3. Datasets

The widespread adoption of deep learning-based image inpainting models across various domains has spurred the development of numerous datasets, serving as cost-effective alternatives to manual annotation. This section categorizes these datasets into two primary groups: mask datasets and image datasets. Image datasets are further subdivided into natural images, artistic images, and scientific/detection images. Natural image datasets consist of photographs depicting everyday scenes, typically captured by consumer devices such as smartphones and cameras, and include portraits, landscapes, etc. Artistic image datasets comprise works shaped by artistic processing and human creativity. Scientific/detection image datasets contain data acquired with specialized instruments for research or industrial purposes, such as medical and satellite imagery. The following subsections detail these categories. The key characteristics of major image inpainting datasets are evaluated in Table 3.

3.1. Mask Datasets

In image inpainting, masks are primarily categorized into regular and irregular types. Regular masks, typically square or rectangular, are suitable for simple inpainting tasks. However, as real-world image corruption is often irregular, irregular masks have become increasingly prevalent. Several key irregular mask datasets include the following:

NVIDIA Irregular Mask Dataset [48]: This dataset contains 55,116 training masks and 12,000 test masks at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels, categorized into six ranges based on hole size. It is extensively used in inpainting research and serves as a standard benchmark for algorithm evaluation.

The Quick Draw Irregular Mask Dataset [110]: This dataset, constructed from 50 million human-drawn vector sketches, comprises 50,000 training masks and 10,000 testing masks. Each binary mask has dimensions of 256 × 256 pixels.

LaMa Masks Dataset [55]: This dataset categorizes free-form masks into narrow masks, large wide masks, and large box masks to simulate irregular missing regions that are large-area, continuous, and have coarse edges.

3.2. Natural Image Datasets

Natural image datasets are the primary resources for training and evaluating image inpainting algorithms. They feature scenes from daily life, captured by standard photographic equipment.

General scene datasets: These include ImageNet [111], DIV2K [112], and LAION-5B [113], widely used for image restoration, recognition, and multimodal tasks. ImageNet, a cornerstone for image recognition, contains over 14 million images across numerous categories with varying resolutions. DIV2K, designed for super-resolution research, offers 1000 high-resolution images and is commonly used for super-resolution algorithm evaluation. LAION-5B is one of the largest publicly available image-text datasets, containing 5.85 billion images and often used for training large multimodal models.

Landscape and urban scene datasets: Datasets such as Paris StreetView [114], Cityscapes [115], and Places2 [116] are frequently used for inpainting and segmentation. Paris StreetView contains urban landscape images from Paris, widely used for street scene analysis. Cityscapes provides 25,000 urban street scene images, suitable for semantic segmentation tasks. Places2 contains over 10 million images spanning more than 400 scene categories, supporting robust scene understanding.

Facial image datasets: These include CelebA [117], CelebA-HQ [118], and Helen Face [119], extensively used for face recognition and attribute prediction. CelebA contains over 200,000 celebrity images annotated with 40 attributes. CelebA-HQ comprises high-resolution versions of CelebA images, suitable for high-quality facial inpainting and generation. Other notable datasets: Additional datasets such as SVNH [120] (street view house numbers), DTD [121] (describing textures), and Stanford Cars [122] are applied to tasks such as digit recognition and fine-grained classification.

3.3. Artistic Image Datasets

Artistic images differ from natural and scientific images; they are often imbued with emotion and cultural context, presenting unique aesthetic and restorative challenges. WikiArt Dataset: This dataset contains approximately 250,000 artworks from 3000 global artists, encompassing diverse cultural styles and forms. It is widely used for artistic image analysis. Art Images-9k Dataset: Comprising about 9000 artworks across five major art forms, it provides a rich resource for artistic image processing and inpainting. Domain-specific studies: Yu et al. [123] employed a partial convolution U-Net to restore 10,000 Dunhuang fresco fragments, providing significant data support for cultural heritage preservation. Wang et al. [124] compiled a dataset of 2782 Thangka mural images, each with a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

3.4. Scientific and Detection Image Datasets

These datasets are captured using specialized instrumentation, containing data not directly perceivable by the human eye. Prominent examples include medical and remote sensing imagery. Medical image datasets: These include DRIVE (vessel segmentation), SCR (chest X-rays), Cardiac MRI (atrial segmentation), and NIH Chest X-rays. They are primarily used for tasks such as MRI artifact correction and CT image inpainting. Remote sensing datasets: Key datasets include NWPU VHR-10, RSOD, DIOR, DOTA, and HRRSD. Research using these datasets often addresses data gaps, such as cloud removal, to enhance image quality and utility. Research in this domain primarily focuses on data restoration and image enhancement via deep learning techniques.

Table 3.

Evaluation of major datasets for image inpainting.

Table 3.

Evaluation of major datasets for image inpainting.

| Type | Representative Dataset | Primary Contributions and Generality | Core Limitations | Directions for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masks | NVIDIA Irregular Mask [48] | Established the benchmark for irregular masks; large-scale. | Diverges from real-world damage (e.g., tears, corrosion) in morphology and degradation patterns. | Develop physically simulated masks and semantic-guided mask generation. |

| Scene Images | Places2 [116] | Rich in scene categories, beneficial for scene understanding. | High intra-scene homogeneity; aesthetically filtered, lacking cluttered, unstructured real-world scenes. | Supplement with unstructured scene data. |

| Face Images | CelebA [117] CelebA-HQ [118] | Large-scale with rich annotations; de facto standard for face inpainting. | Primarily composed of celebrity facial images, Lacks diversity in race, age, expression, illumination, and pose. | Cross-validate using diverse sets (e.g., FFHQ) and report biases. |

| Artistic Images | WikiArt | Covers diverse art styles, promoting digital art restoration and stylized generation. | Strong style–content coupling requires style consistency; lacks damage annotations and professional evaluation. | Establish sub-benchmarks for artistic styles with expert ratings and damage-paired data. |

| Dunhuang Murals [123] Thangka [124] | Important cultural heritage, providing domain-specific data. | Highly specialized; limited data; difficult to acquire; features unique damage types. | Expand scale via high-fidelity synthetic data; explore domain adaptation methods. | |

| Medical Images | NIH Chest X-ray | Relatively large-scale public medical imaging dataset. | Data lacks fine-grained annotations; suffers from class imbalance and bias; presents issues with image quality and consistency. | Expand the dataset with clinically balanced categories and employ expert evaluation for annotation. |

| Remote Sensing | NWPU VHR-10 | High-resolution remote sensing imagery; high-quality annotations. | Its small scale impairs the model’s adaptability to diverse real-world scenarios. | Supplement with real multi-temporal and multispectral data; introduce spectral fidelity metrics during evaluation. |

| Large-Scale Multimodal | LAION-5B [113] | Unprecedentedly large-scale image–text paired dataset, supporting guided inpainting. | High noise and bias; risk of data contamination. | Requires rigorous cleaning, deduplication, and auditing. |

As detailed in Table 3, while current image inpainting datasets have propelled technological advancement, their inherent biases, simplifications, and domain-specific isolation collectively foster a “greenhouse-like” evaluation environment. This leads many studies to chase metric improvements on specific, sanitized data, thereby becoming disconnected from the complex, diverse, and high-stakes inpainting demands of the open world. Future efforts must focus on constructing more challenging, diagnostic, and responsible datasets. Placing generalization, fairness, and safety on par with peak performance will be essential to steer the field toward robust and trustworthy inpainting intelligence.

4. Image Quality Assessment (IQA)

Image Quality Assessment (IQA) is a fundamental technology in image processing, aiming to quantify human visual perception and guide algorithm optimization. It holds significant value in computer vision, image compression, and related fields. Current IQA methodologies are broadly divided into subjective and objective assessment. Subjective assessment relies on Mean Opinion Scores (MOSs) from human observers. While intuitive and reliable, it suffers from inherent subjectivity and high labor costs. Objective assessment employs mathematical models to automatically compute quality scores. However, discrepancies exist between different metrics, and their alignment with human perception requires further improvement. These metrics can be categorized according to whether the original reference image is required during evaluation and the amount of information needed, as detailed in Table 4. Furthermore, our suggestions for metric selection tailored to different inpainting scenarios are presented in Table 5. An overview of commonly used image quality assessment metrics and their calculation formulas follows.

Table 4.

Categorization of evaluation metrics.

Table 5.

Suggested metric selection for different inpainting scenarios.

- (a)

- PSNR

The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [125] is a full-reference image quality assessment metric based on mean squared error. It quantifies image fidelity by computing the ratio between the maximum possible signal power and the noise power. PSNR offers advantages of computational simplicity and clear physical interpretation, with higher values indicating better reconstruction quality. However, it fails to adequately account for the characteristics of the human visual system, exhibits poor correlation with subjective quality assessments, and may lead to misleading conclusions in practical applications. The formula is defined as follows:

where is the maximum fluctuation of the input image data type. is the mean squared error between original and processed images.

- (b)

- SSIM

The Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) [126] establishes a perceptually consistent full-reference quality assessment model by simulating the human visual system’s perception of luminance, contrast, and structural information. This metric demonstrates superior consistency with subjective evaluations across various distortion types, significantly outperforming traditional PSNR. However, its assessment performance degrades noticeably when handling low-contrast images or high-noise scenarios. The function is expressed as follows:

where and are the mean intensities of images and . and are the standard deviations. represents the covariance. and are constants to stabilize division.

- (c)

- FID

The Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [127] provides an effective performance benchmark for generative models such as Generative Adversarial Networks by computing the Wasserstein-2 distance between multivariate Gaussian distributions of real and generated images in deep feature space. This metric comprehensively reflects both the quality and diversity of generated images but exhibits sensitivity to training sample size, potentially yielding unstable evaluations in small-sample scenarios. The formula is expressed as follows:

where and are the mean feature vectors extracted from pre-trained networks. and are the corresponding covariance matrices. is the matrix trace.

- (d)

- IS

The Inception Score (IS) [128] evaluates the visual quality and category diversity of generated images using prediction confidence distributions from pre-trained image classifiers. This metric requires ideal generation results to possess both distinct semantic category characteristics and sufficient category distribution coverage. However, IS cannot effectively identify model overfitting and shows sensitivity to the architectural choices of the base classification network. The function is defined as follows:

where is the class prediction probability distribution for generated image . is the marginal class probability distribution across all generated images. is the Kullback–Leibler divergence.

- (e)

- L1 Loss

L1 Loss, also known as the mean absolute error, is a fundamental full-reference image quality assessment metric that computes the average absolute difference between corresponding pixels in target and generated images. This method provides straightforward quality assessment with advantages of computational simplicity and optimization ease. Its primary limitation lies in neglecting image structural information and human visual perception characteristics. The formula is defined as follows:

where is the pixel value in the ground truth image. is the pixel values in the reconstructed image. is the total number of pixels.

- (f)

- IFC

The Information Fidelity Criterion (IFC) [129] is a full-reference image quality assessment metric derived from information theory, modeling image quality as information shared between reference and distorted images or as information loss. Based on natural scene statistics and information theory, this method fully considers image structure and information content to provide more perceptually consistent quality assessment. However, its complex computational pipeline limits real-time application. The function is expressed as follows:

where denotes coefficients from the RF of the kth subband, and similarly for and .

- (g)

- VSNR

The Visual Signal-to-Noise Ratio (VSNR) [130] is a full-reference image quality assessment metric that incorporates a human visual system perception model for visual errors, decomposing error signals into perceptually visible and invisible components. This metric performs well for common distortion types, but its assessment accuracy decreases under extreme noise conditions. The formula is expressed as follows:

where denotes the RMS contrast of the original image I. is the visual distortion.

- (h)

- FSIM

The Feature Similarity Index Measure (FSIM) [131] is a full-reference image quality assessment metric based on the premise that the human visual system understands images primarily through low-level features, such as phase consistency and gradient magnitude. This metric performs well across various distortion types but shows sensitivity to illumination changes and color distortion. The formula is defined as follows:

where denotes the local similarity between the reference image x and the distorted image y at position i; represents the phase consistency weight at position i.

- (i)

- MS-SSIM

The Multi-Scale Structural Similarity Index Measure (MS-SSIM) [132] extends the SSIM metric as a full-reference image quality assessment approach that simulates human multi-scale perception by combining structural similarity computations across multiple scales. This method provides more comprehensive quality assessment by evaluating structural similarity at multiple scales, better reflecting human multi-scale perception characteristics than single-scale SSIM, though at the cost of increased computational complexity. The function is expressed as follows:

where represents the number of image scales. The terms , , and are non-zero constants used to adjust the relative importance of the luminance, contrast, and structural similarity estimates, respectively, relative to the original image.

- (j)

- NIQE

The Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) [133] is a no-reference (blind) image quality assessment metric that evaluates quality by measuring the deviation between statistical features of test images and a statistical model learned from high-quality natural images. This method requires no original reference image, enabling completely blind assessment. However, its applicability to specific image types remains limited. Lower scores indicate better quality, representing smaller deviation from the reference model. The formula is expressed as follows:

where , and , are the mean vectors and covariance matrices of the natural multivariate Gaussian model and the distorted image’s multivariate Gaussian model.

- (k)

- LPIPS

The Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [134] is a full-reference image quality assessment metric that computes distances between images in deep feature spaces using convolutional neural networks pre-trained on large-scale datasets. This method demonstrates strong alignment with human visual perception and currently represents one of the best-performing metrics regarding correlation with subjective scores. However, its high computational requirements limit real-time applications. The function is expressed as follows:

where and are the feature representations at layer of the deep network. is the channel-wise weight for layer . represents element-wise multiplication.

- (l)

- PIQUE

The Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator (PIQUE) [135] is a no-reference image quality assessment metric that operates without any training data, relying instead on handcrafted features and perceptual rules. This approach represents a distinct technical pathway from data-driven machine learning methods. Its strengths lie in its clear interpretability, elimination of the training requirement, computational efficiency, and its ability to generate a spatial distortion map. However, a key limitation of PIQUE is its potential inferiority in modeling complex or mixed distortions compared to deep learning models trained on extensive datasets.

- (m)

- TOPIQ

TOPIQ [136] is a deep learning-based image quality assessment metric applicable to both FR-IQA and NR-IQA tasks. Its core innovation lies in emulating the top-down perceptual mechanism of the human visual system. A cross-scale attention network guides the model to focus on semantically important local distortion regions, achieving high accuracy alongside exceptional computational efficiency. The advantages of this approach include its biomimetic perceptual design, efficient feature interaction, and an outstanding performance-efficiency trade-off. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for practical scenarios that are sensitive to computational resources and where distortion types correlate with image content, such as mobile image processing and large-scale quality screening. However, its performance is contingent upon the backbone architecture (ResNet50), and its advantage may diminish when assessing globally uniform distortions that have low relevance to semantics. Furthermore, as a convolutional neural network, it possesses a theoretical ceiling in modeling extremely complex distortions. Consequently, its generalization capability requires further validation when pursuing state-of-the-art performance or handling distortions specific to particular professional domains.

As summarized in Table 4 and Table 5, image inpainting quality assessment metrics can be categorized into full-reference metrics for pixel fidelity, no-reference metrics requiring no reference image, and distribution-based metrics for evaluating the overall performance of generative models. The most significant challenge currently facing the inpainting evaluation framework is the misalignment between existing metrics and the core objective of the task: the former were designed to measure known distortions, whereas the latter centers on generating plausible new content. Mathematical fidelity metrics such as PSNR/SSIM exhibit weak or even negative correlation with human judgment in semantic generation scenarios, often misleading research toward overly smooth results. Perceptual metrics such as LPIPS show higher correlation but may fail to capture errors that violate overarching semantics or physical logic. A deeper misalignment stems from a cognitive gap: humans rely on high-level reasoning to judge correctness, while metrics compute only the realism of low-level features. This can lead metrics to assign high scores to semantically absurd yet texturally natural generations. Current practices also involve metric misuse, such as prioritizing PSNR for subjective quality assessment, overlooking the sample sensitivity of FID, or indiscriminately applying no-reference metrics outside their intended domain. A layered evaluation mechanism is now commonly adopted. For example, a foundational layer employs PSNR/SSIM to ensure reproducibility, a perceptual layer uses LPIPS/FID to gauge visual naturalness, culminating in human judgment or deep learning-based diagnostic methods. The future evaluation paradigm must evolve toward greater interpretability, interactivity, and task utility. By quantifying cognitive load or downstream task performance, we may genuinely bridge the gap between objective scores and subjective value.

5. Challenges and Future Directions