Key Noise Evaluation of Analog Front-End in Microradian-Level Phasemeter for Space Gravitational Wave Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

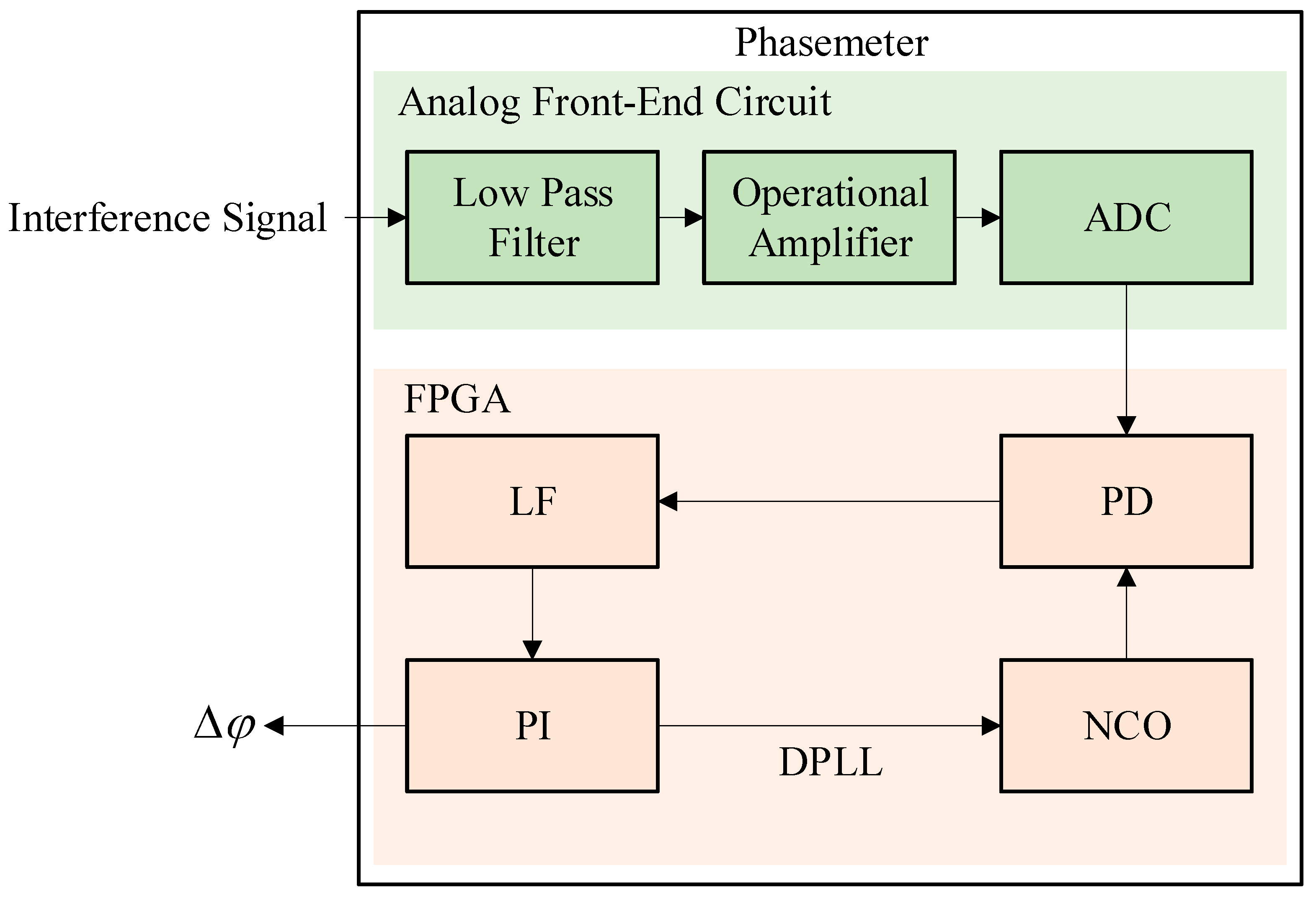

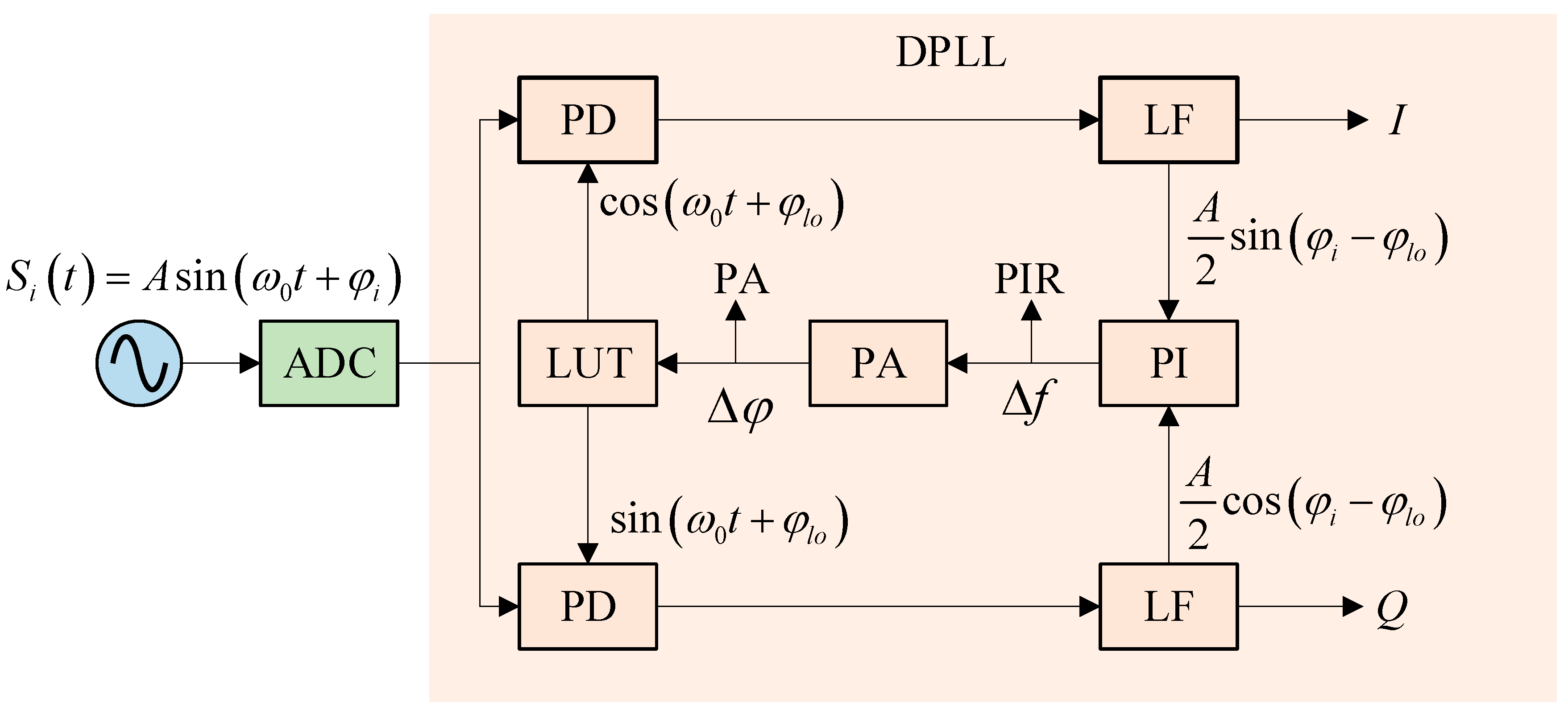

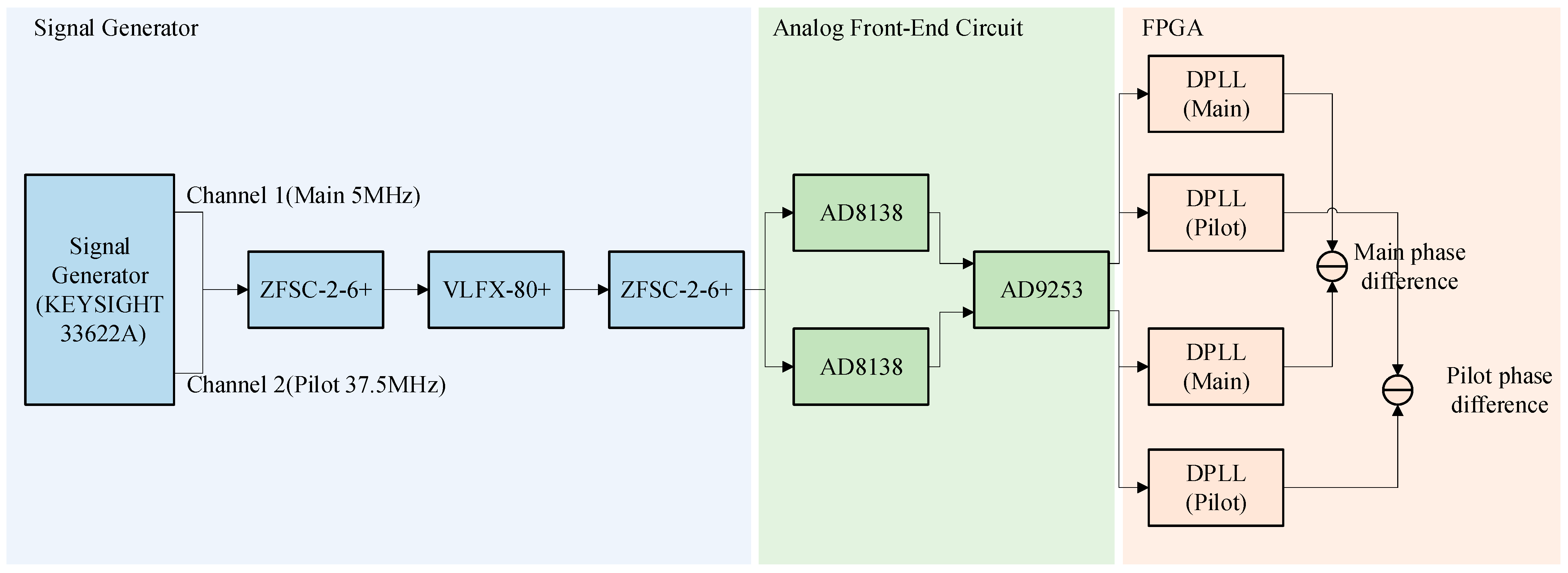

2. System Modeling and Noise Propagation Mechanism

2.1. System Architecture and Signal Flow

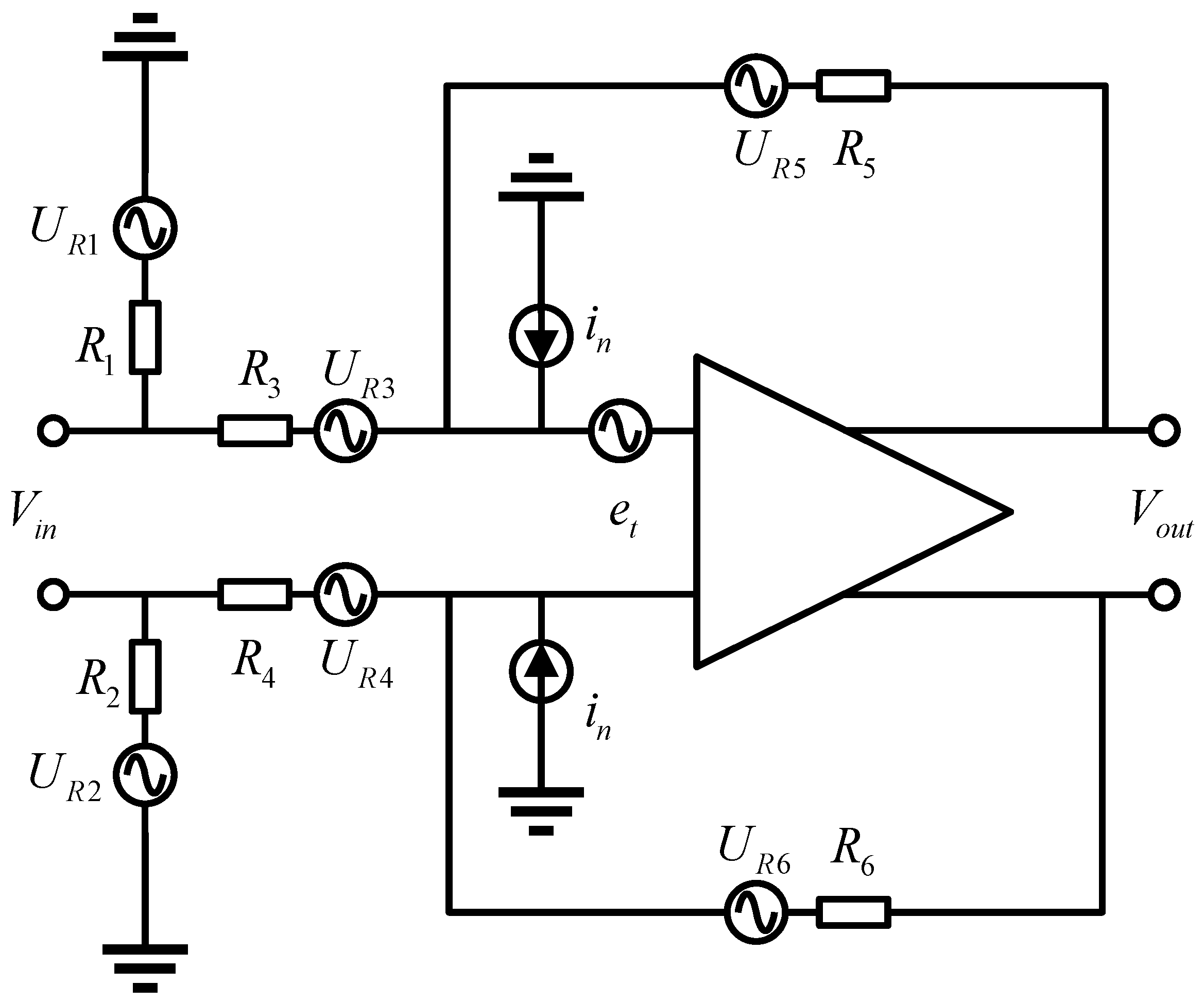

2.2. Input Signal and Noise Model

- Input voltage noise:

- 2.

- Input current noise:

- 3.

- Resistor thermal noise:

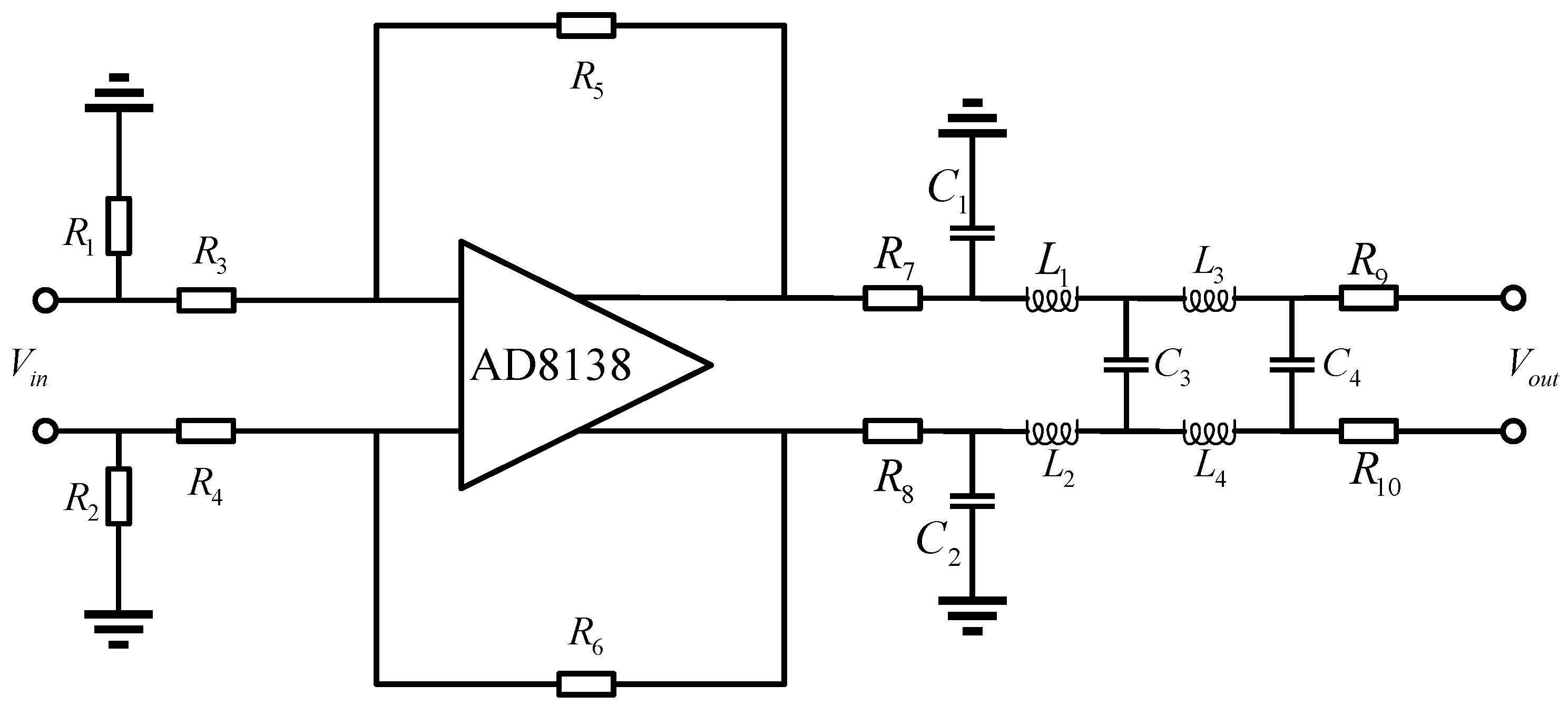

3. Differential Operational Amplifier Analog Front-End Design and Simulation

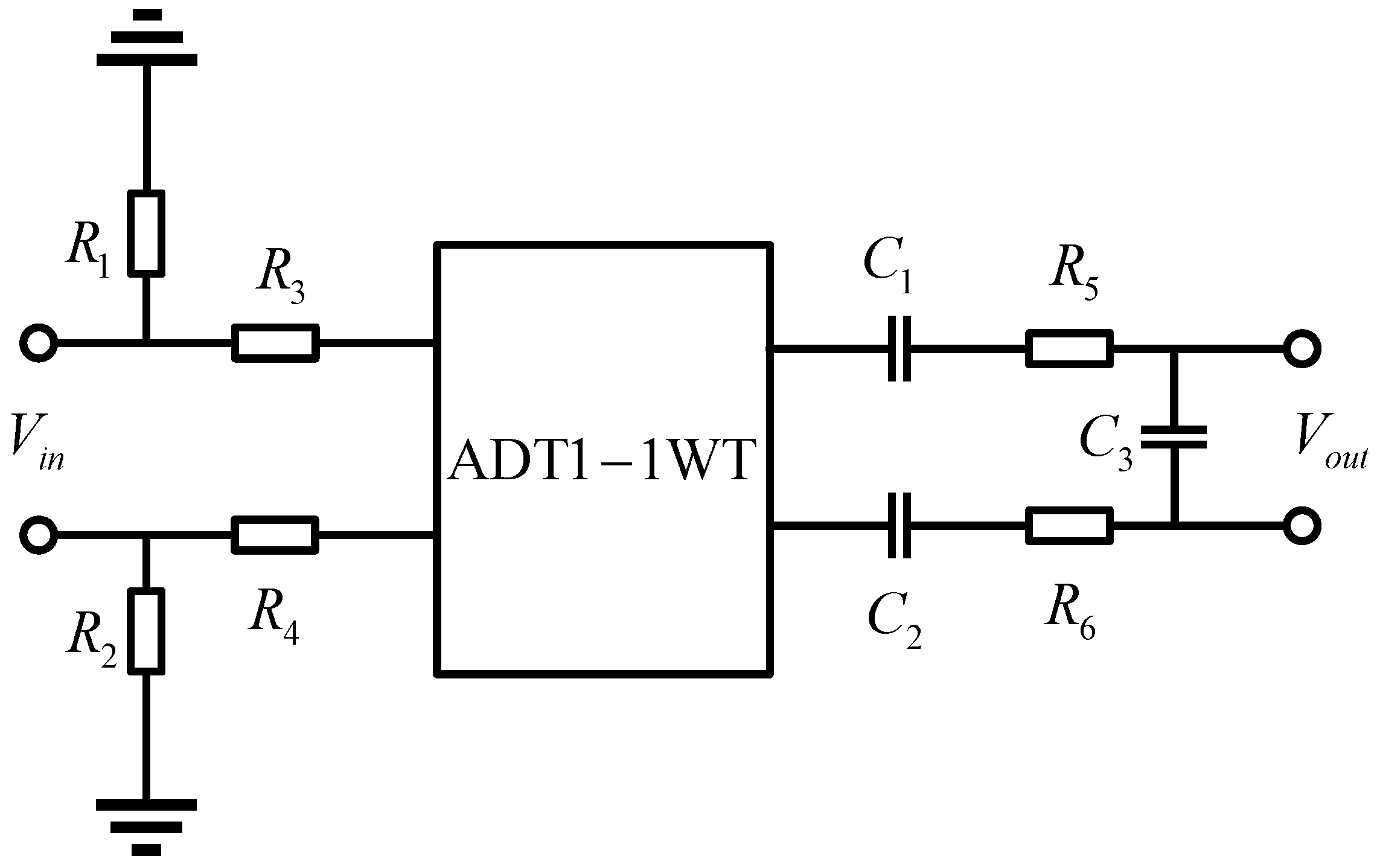

3.1. Differential Operational Amplifier Front-End Architecture

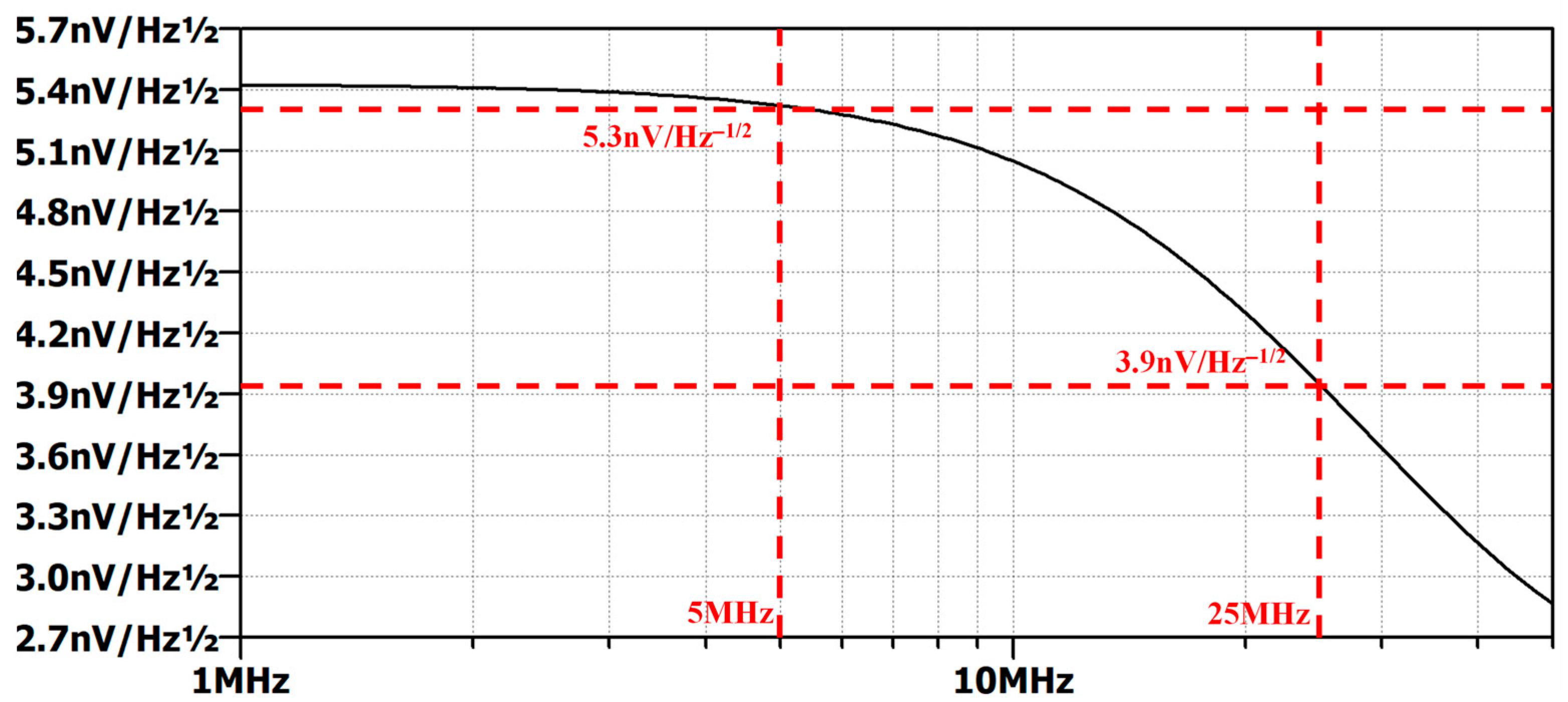

3.2. Noise Simulation of the Front-End Circuit

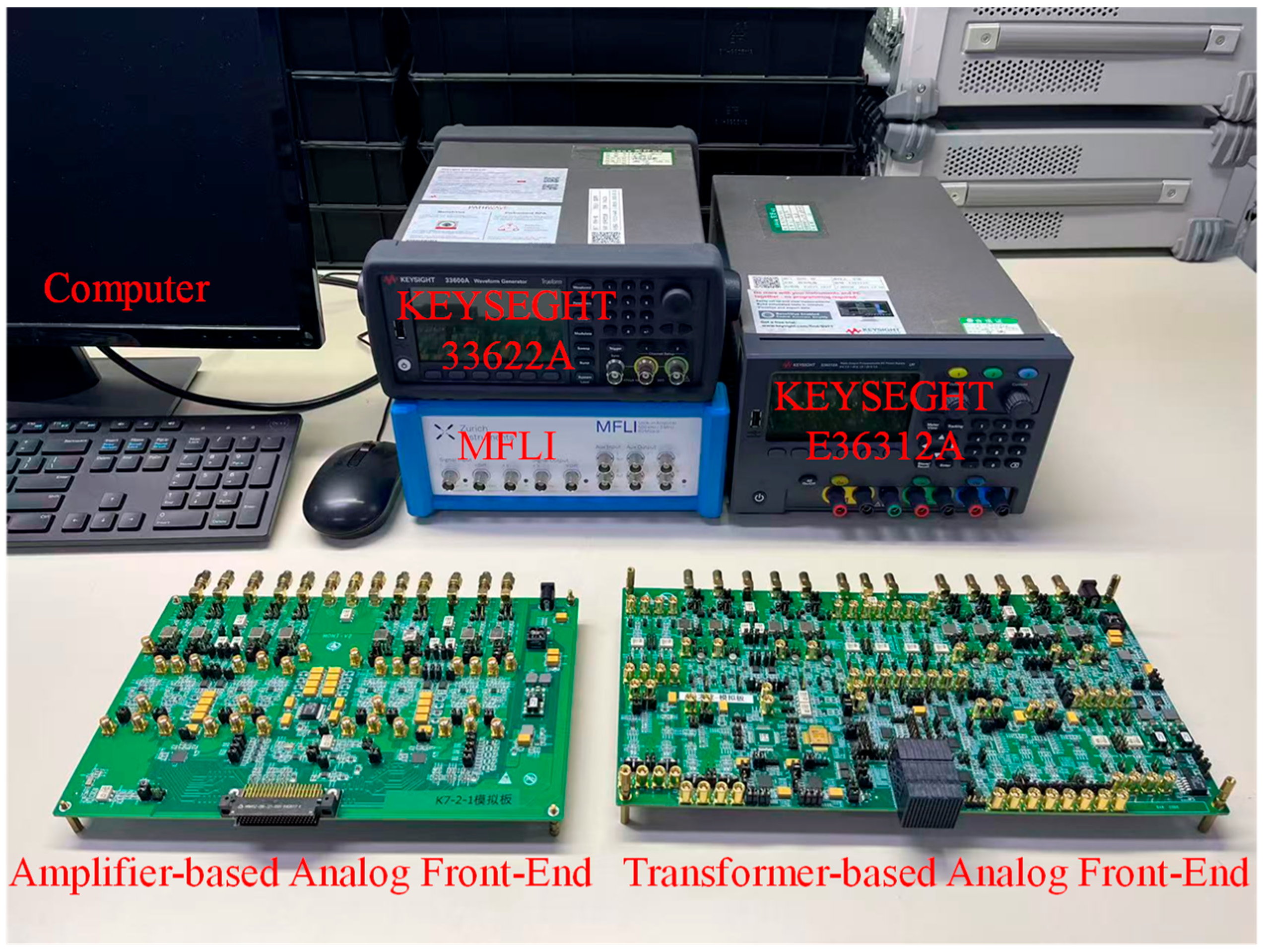

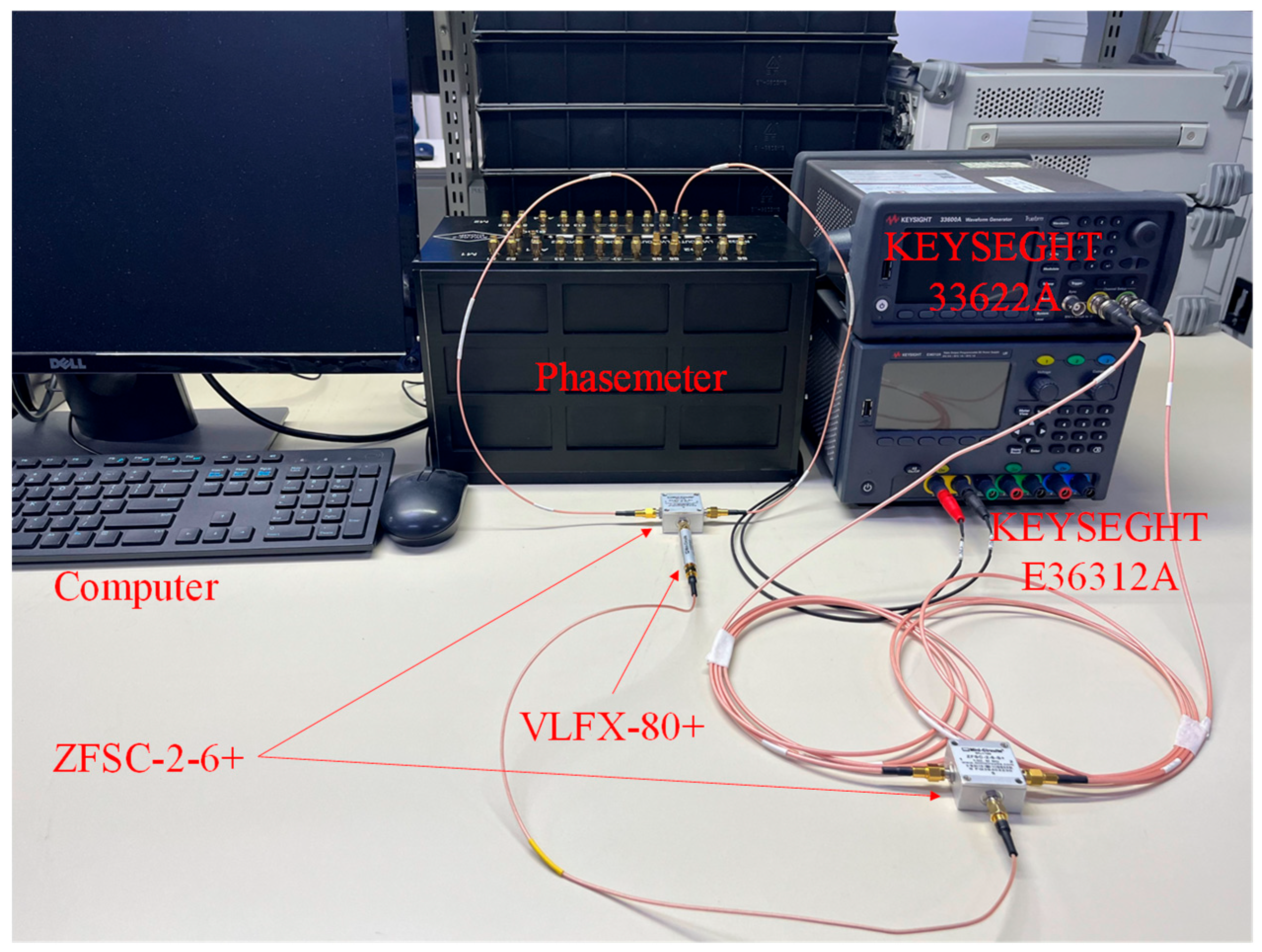

4. Experimental Verification

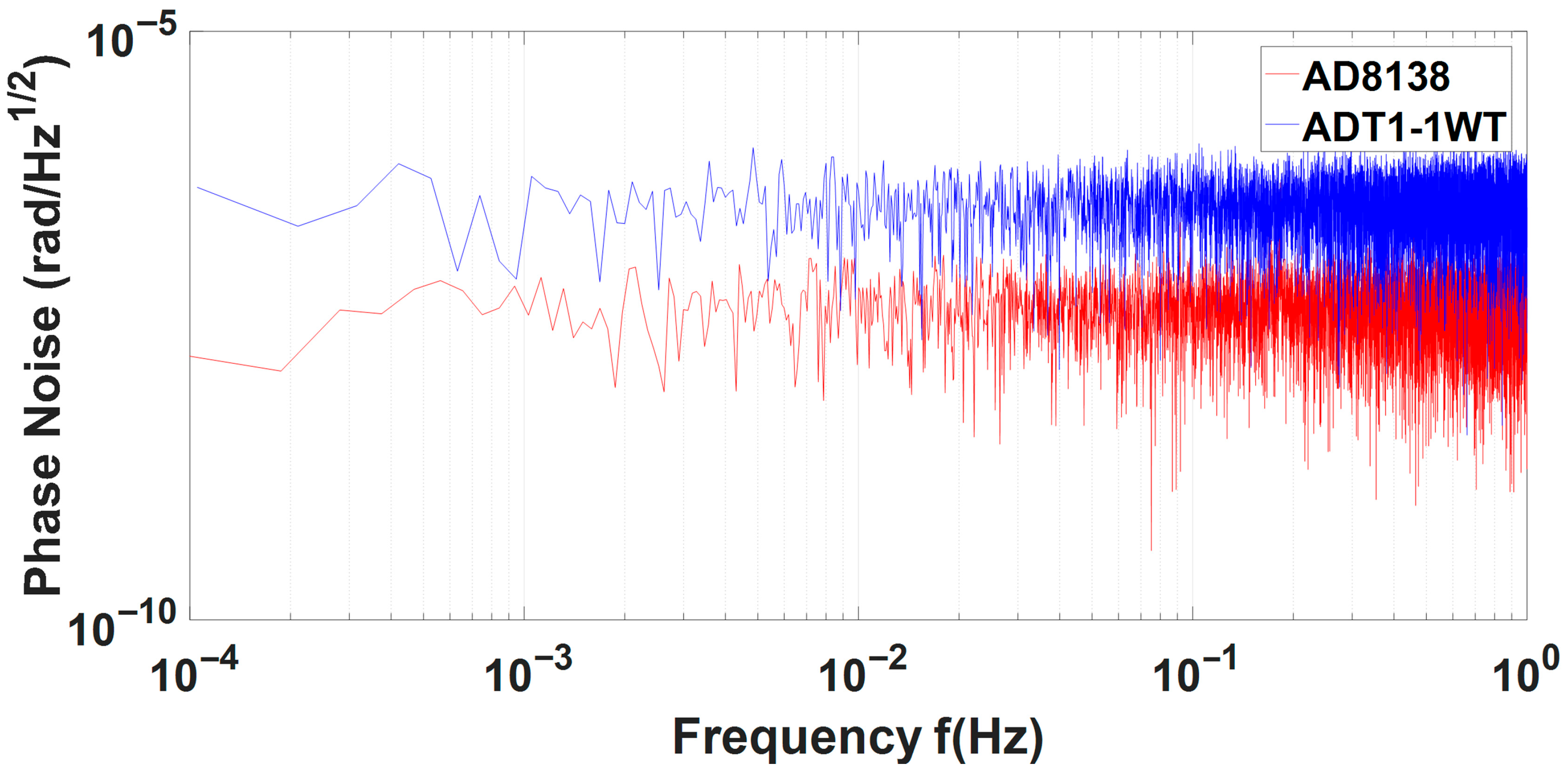

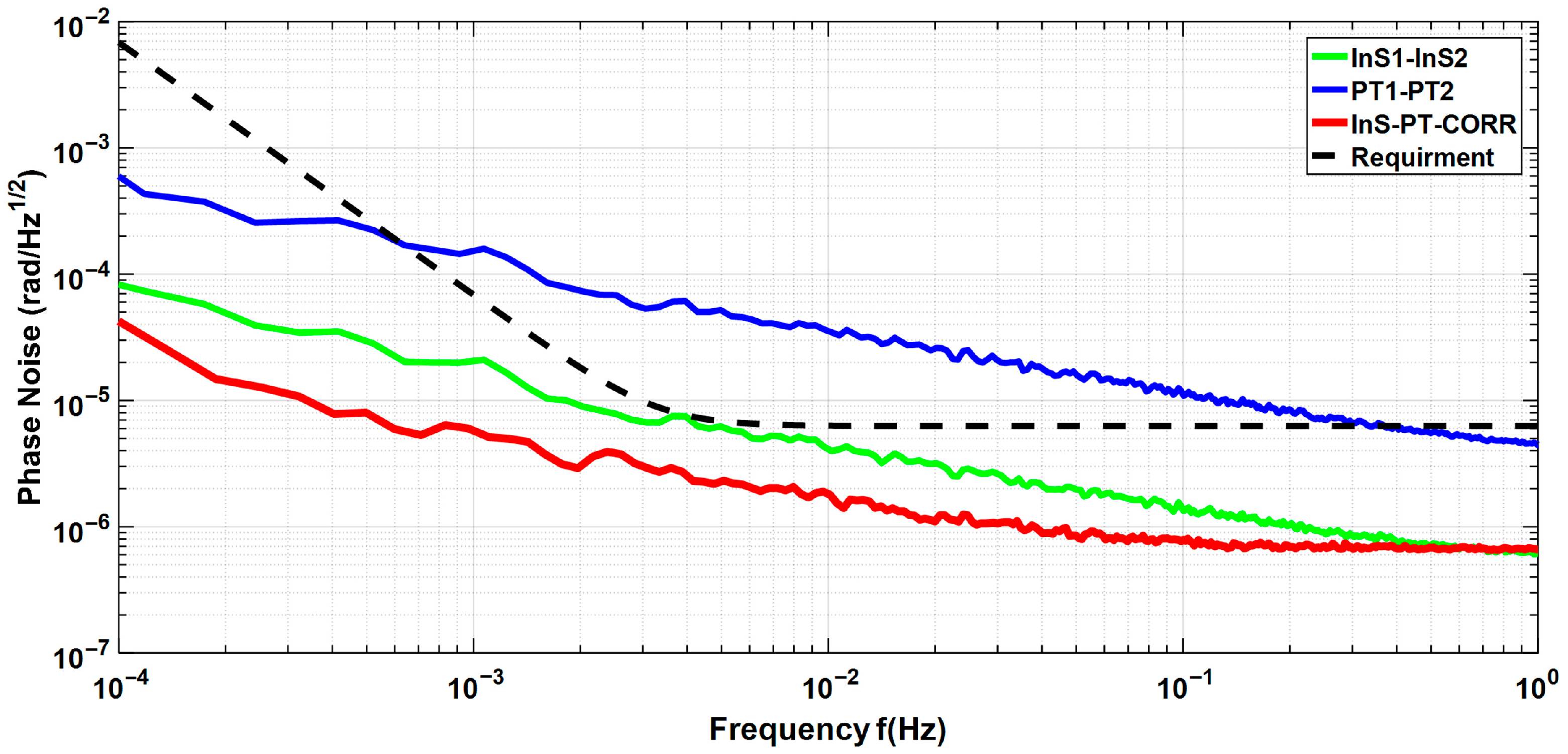

4.1. Comparison Between Differential Operational Amplifier and Transformer

4.2. Differential Operational Amplifier Noise Evaluation Method

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abernathy, M.R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, D.; Abernathy, R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P. Ligo Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration; et al. Directly comparing gw150914 with numerical solutions of einstein’s equations for binary black hole coalescence. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 064035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Seoane, P.; Audley, H.; Babak, S.; Baker, J.; Barausse, E.; Bender, P.; Berti, E.; Binetruy, P.; Born, M.; Bortoluzzi, D.; et al. Laser interferometer space antenna. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.00786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, L.-S.; Duan, H.-Z.; Gong, Y.-G.; Hu, S.; Ji, J.; Liu, Q.; Mei, J.; Milyukov, V.; Sazhin, M.; et al. Tianqin: A space-borne gravitational wave detector. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Guo, Z.; Jin, G.; Wu, Y.; Hu, W. A brief analysis to taiji: Science and technology. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmann, J. Development of a Digital Phase Measuring System with Microradian Precision for Lisa. Ph.D. Thesis, Leibniz University, Hannover, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, W.; Jin, G. The taiji program: A concise overview. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 2021, 05A108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyukov, V.K. Tianqin space-based gravitational wave detector: Key technologies and current state of implementation. Astron. Rep. 2020, 64, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.J.; Li, X.H.; Yu, P.Y.; Chen, Y.; Ren, L.; Liu, H.S. Research on high-sensitive quad photodetector for gravity waves detection. Semicond. Optoelectron. 2021, 42, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Qi, K.; Wang, S.; Gao, R.; Li, P.; Yang, R.; Liu, H.; Luo, Z. Advance and prospect in the study of laser interferometry technology for space gravitational wave detection. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 2024, 54, 270405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-R.; Feng, Y.-J.; Xiao, G.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Li, L.; Jin, X.-L. Experimental scheme and noise analysis of weak-light phase locked loop for large-scale intersatellite laser interferometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 92, 124501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Xue, K.; Long, H.; Pan, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Development of a micro-radian phasemeter and verification based on single pilot tone for space gravitational wave detection. Symmetry 2025, 17, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, T.; Luo, Z. A low-noise analog frontend design for the taiji phasemeter prototype. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 92, 054501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, C.H. Noise in the Lisa Phasemeter; Institutionelles Repositorium der Leibniz Universität Hannover: Hannover, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Luo, Z.; Jin, G. The development of phasemeter for taiji space gravitational wave detection. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2018, 30, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerberding, O.; Diekmann, C.; Kullmann, J.; Tröbs, M.; Bykov, I.; Barke, S.; Brause, N.C.; Delgado, J.J.E.; Schwarze, T.S.; Reiche, J.; et al. Readout for intersatellite laser interferometry: Measuring low frequency phase fluctuations of high-frequency signals with microradian precision. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 86, 074501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Villuendas, F.; Borja, J.; Barragán, L.A.; Salinas, I. Low-cost, digital lock-in module with external reference for coating glass transmission/reflection spectrophotometer. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, P.B. A new method for processing of basic electric values. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Ren, R.; Kou, Y.; Sun, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Hou, D. Direct loop gain and bandwidth measurement of phase-locked loop. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2017, 88, 084704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerberding, O.; Sheard, B.; Bykov, I.; Kullmann, J.; Delgado, J.J.E.; Danzmann, K.; Heinzel, G. Phasemeter core for intersatellite laser heterodyne interferometry: Modelling, simulations and experiments. Class. Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 235029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Xue, K.; Long, H.; Pan, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Development and verification of sampling timing jitter noise suppression system for phasemeter. Photonics 2025, 12, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xue, K.; Yu, T.; Long, H. Key Noise Evaluation of Analog Front-End in Microradian-Level Phasemeter for Space Gravitational Wave Detection. Symmetry 2026, 18, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010093

Xue K, Yu T, Long H. Key Noise Evaluation of Analog Front-End in Microradian-Level Phasemeter for Space Gravitational Wave Detection. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Ke, Tao Yu, and Hongyu Long. 2026. "Key Noise Evaluation of Analog Front-End in Microradian-Level Phasemeter for Space Gravitational Wave Detection" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010093

APA StyleXue, K., Yu, T., & Long, H. (2026). Key Noise Evaluation of Analog Front-End in Microradian-Level Phasemeter for Space Gravitational Wave Detection. Symmetry, 18(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010093