Abstract

Grid-forming (GFM) converters are promising for renewable energy integration, but their overcurrent limitation during grid faults remains a critical challenge. Existing overcurrent-limiting strategies were primarily developed for two-level converters and are often inadequate for Modular Multilevel Converters (MMCs). By overlooking the MMC’s unique topology and internal physical constraints, these conventional methods compromise both operational safety and grid support capabilities. Thus, this paper proposes a dynamic asymmetric overcurrent-limiting strategy for grid-forming MMCs that considers multiple physical constraints. The proposed strategy establishes a dynamic asymmetric overcurrent boundary based on three core physical constraints: capacitor voltage ripple, capacitor voltage peak, and the modulation signal. This boundary accurately defines the converter’s true safe operating area under arbitrary operating conditions. To address the complexity of the boundary’s analytical form for real-time application, an offline-trained neural network is introduced as a high-precision function approximator to efficiently and accurately reproduce this dynamic asymmetric boundary. The effectiveness of the proposed strategy is verified by hardware-in-the-loop experiments. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed strategy reduces the capacitor voltage ripple by 30.7% and maintains the modulation signal safely within the linear range, significantly enhancing both system safety and fault ride-through performance.

1. Introduction

Grid-forming (GFM) converters, which act as voltage sources to establish system frequency and voltage, are pivotal for the integration of renewable energy. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted on GFM converters, covering aspects such as control implementation, transient response, and stability issues, and fault ride-through strategies [1,2]. GFM converters are extremely sensitive to large disturbances, and their overcurrent limitation during faults remains a critical issue to be addressed.

Many recent studies have focused on current-limiting methods for GFM converters. The mainstream approaches can be broadly categorized into three types: the current saturation algorithm, the virtual impedance method, and the voltage limitation method [3].

The current saturation algorithm directly incorporates a limiting block within the current control loop, constraining the dq-axis reference currents to within the maximum current-carrying capacity of the GFM converter during a fault [4]. In ref. [5], a resonant fault current limiter was presented, where its parallel resonant circuit provides high impedance under fault conditions to achieve current limitation. Although the method in [6] can effectively limit the current, its limiter structure is complex and incurs higher hardware costs.

As an indirect current-limiting approach, the virtual impedance method alters the converter’s output characteristics by introducing a virtual impedance in the outer voltage loop, thereby achieving current limitation. In ref. [7], a current-dependent virtual impedance was added at the inverter’s output to increase transient impedance during faults, preventing overcurrent. To address voltage limitation issues of traditional methods, ref. [8] connected the virtual impedance in parallel with the output filter capacitor to limit fault phase current. Additionally, ref. [9] proposed an adaptive virtual impedance strategy for GFM converters in weak grids. However, compared to the current saturation algorithm, the virtual impedance method offers superior fault tolerance but weaker limiting capability, with overcurrent risks persisting under certain conditions [10].

Another indirect limiting approach is the voltage limitation method, which restricts the current magnitude by adjusting the reference voltage of the outer voltage loop. This method is also indirect, but its advantage over the virtual impedance method lies in its ability to avoid potential system stability problems that may arise under specific operating conditions [11]. In ref. [12], an overcurrent protection method based on dynamic voltage limitation was introduced, which indirectly achieves current limitation by constraining the magnitude and phase angle of the output voltage. In ref. [13], on the other hand, a voltage limiter was proposed to proactively control the voltage, thereby maintaining the current within the desired range.

Although the existing mainstream current-limiting strategies are widely adopted [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], they all exhibit inherent limitations in achieving key objectives such as precise current limitation and ensuring grid support. The direct limiting approach of the current saturation algorithm suffers from poor fault recovery capability [10]. Indirect strategies, such as the virtual impedance and voltage limitation methods, generally face the risk of transient overcurrent, and improper parameter selection may lead to system instability [13,14]. These current-limiting strategies primarily originate from two-level converters. More critically, existing research applies them to MMC without considering the unique characteristics and complex internal constraints of the MMC topology. Although MMC-specific strategies have been explored to address unbalanced conditions, such as the method proposed by Freytes et al. [15], they often rely on complex analytical derivations. Similarly, advanced control strategies for seamless switching in virtual synchronous generators have been proposed to enhance grid stability [16], yet applying such concepts to the internal constraint management of MMCs remains a challenge. These analytical methods struggle to simultaneously solve multiple coupled nonlinear constraints—specifically, the coupling between capacitor voltage ripple, peak voltage, and modulation linearity—within the microsecond-level time constraints of real-time control. It is worth noting that more recent works have explicitly mapped MMC internal constraints, such as submodule capacitor ripple, peak voltage, and modulation margin, into current or power bounds. Specifically, in ref. [17], the steady-state operating area is derived by considering submodule capacitor voltage fluctuations and modulation limits. Similarly, Reference [18] utilizes a dynamic phasor model to quantify the feasible operation zone under capacitor voltage constraints. Furthermore, in ref. [19], a joint limiting control strategy based on virtual impedance shaping is proposed to suppress arm overcurrents by reshaping the MMC impedance characteristics. These works provide a theoretical basis for understanding the operational limits of MMCs. However, these studies primarily focus on steady-state operating envelopes, offline capability analysis, or specific DC fault scenarios. They have not yet fully translated these internal constraints into real-time dynamic current-limiting strategies specifically for GFM converters during grid faults. Consequently, existing limiting strategies applied in GFM control still largely originate from two-level converters and overlook the opportunity to dynamically adjust current limits based on the unique topology and complex internal physical constraints of the MMC, thereby compromising operational safety and grid support capabilities.

To address this issue, this paper proposes a dynamic asymmetric overcurrent-limiting strategy for grid-forming MMC that considers multiple physical constraints. Compared with the existing methods, it has the following three characteristics:

- The control strategy takes into account multiple physical constraints unique to the MMC, establishing a dynamic asymmetric current boundary that comprehensively and accurately defines the converter’s true safe operating area under arbitrary operating conditions.

- The strategy is capable of dynamically adjusting the current limit in real-time in response to variations in the grid-side voltage. This achieves optimal dynamic current support while adhering to the established safety constraints, thereby significantly enhancing the converter’s dynamic voltage support and fault ride-through capability.

- The implementation of the proposed strategy achieves both high accuracy and computational efficiency. This strategy eliminates intensive online calculations and enables easy integration into existing digital control systems without modifying the main circuit topology.

In this paper, dynamic limitation is achieved by constructing a current boundary that dynamically changes with operating conditions. Firstly, based on the operational principles of the MMC, three core physical constraint models that restrict its overcurrent capability are analyzed and established: the submodule capacitor voltage ripple constraint, the capacitor voltage peak constraint, and the modulation signal constraint. A unified dynamic overcurrent boundary, which is coupled with the grid voltage and current phase angle, is derived based on these constraint models. A neural network is introduced to accurately reproduce this dynamic boundary, as the analytical form of this boundary is difficult for direct use in microsecond-level real-time control. A dynamic limiter is designed, which uses the trained neural network to calculate the current limit in real-time and proactively constrain the control commands. Experimental results prove the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the differences in overcurrent limitation between conventional two-level converters and MMC. Section 3 provides a detailed derivation of the mathematical models for these core constraints. Section 4 elaborates on the proposed dynamic overcurrent-limiting strategy and presents its implementation scheme. The effectiveness of the proposed strategy is verified by hardware-in-the-loop in Section 5. The conclusions are summarized in Section 6.

2. Difference in Overcurrent Limitation Between MMC and Two-Level Converters

2.1. Traditional Overcurrent Limitation in Two-Level Converters

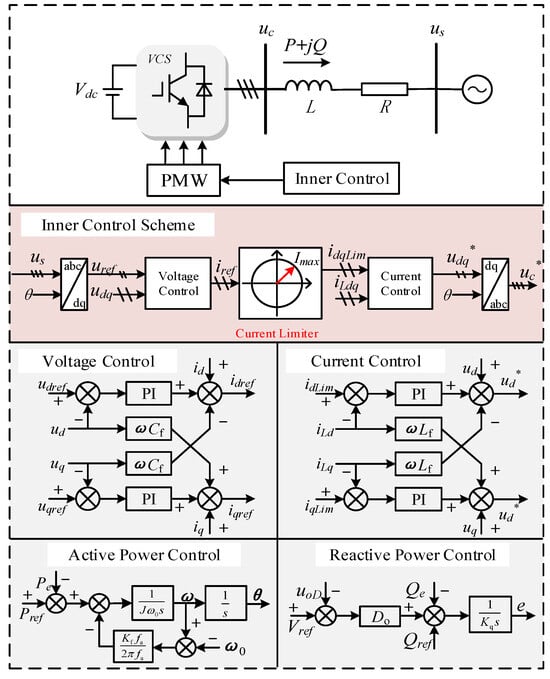

The typical main circuit topology and control block diagram of a two-level converter is shown in Figure 1. In a conventional two-level converter, overcurrent limitation is implemented within a vector control framework. The three-phase AC currents ia, ib, ic are transformed into the synchronous dq-frame, yielding the active id and reactive iq current components.

Figure 1.

Typical main circuit topology and control block diagram of a two-level converter.

The core of this limitation is applied to the current references idref and iqref generated by the outer voltage loop. Before being fed to the current controller, these references are constrained to a preset maximum amplitude. This constraint can be precisely described by the following formula:

where idref is the reference value of the d-axis current, iqref is the reference value of the q-axis current, and Imax is the maximum current amplitude that the converter can withstand.

When the current reference values idref and iqref generated by the control system are such that their vector sum exceeds Imax, overcurrent limiting adjusts idref and iqref to ensure they do not exceed the maximum current that the converter’s power devices can withstand. This maximum current Imax is primarily determined by the thermal limits of the power semiconductors and is often set to 1.5 times the rated current to ensure reliable overload capability.

In addition, the converter operation is subject to modulation signal constraints, which define the output voltage boundaries. To avoid entering the nonlinear overmodulation region, the modulation signal amplitude must be limited to a specific upper limit. This voltage limit determines the maximum current Imax that the converter can output at different power factors. While the converter’s output is also bounded by modulation limits, the semiconductor current rating is typically the dominant constraint defining the overload capability in two-level converters.

Fundamentally, this traditional current limiting strategy can be characterized as both static and symmetrical. Its static nature stems from the enforcement of a fixed current limit Imax, which remains constant irrespective of dynamic operating conditions such as grid voltage variations. It is symmetrical because this fixed limit defines a uniform, circular boundary in the d-q reference frame, implying that the converter’s current-carrying capability is identical regardless of the current’s phase angle. While effective for simpler two-level topologies, this static and symmetrical approach is insufficient for the more complex Modular Multilevel Converter.

2.2. The Overcurrent Limitation in MMC

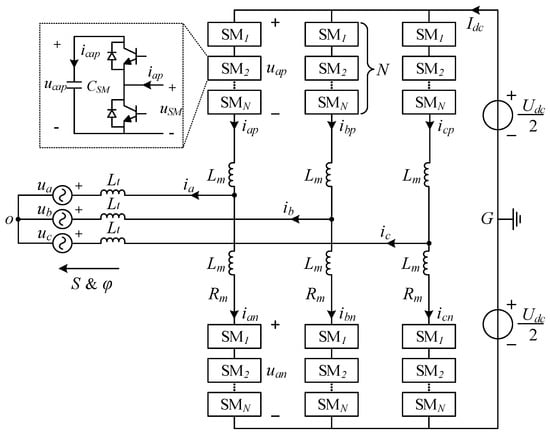

The typical topology of an MMC is shown in Figure 2. Compared to two-level converters, the MMC topology undergoes significant changes. Its DC-side energy storage capacitors are distributed across each submodule (SM) rather than being centrally located at both ends of the DC bus. This structural difference leads to unique complexity in the MMC’s operating mechanism and control methods.

Figure 2.

Typical topology of an MMC.

2.2.1. Problem 1: Submodule Capacitor Voltage Fluctuation

In an MMC, the currents iap(t) and ian(t) of the upper and lower bridge arms flow directly through the capacitors of each submodule. This causes the submodule capacitor voltage to fluctuate, not be a constant value, but rather include a series of low-order harmonics. The capacitor voltage uc(t) of a single submodule can be expressed as the superposition of the DC component Ucap,0 and the harmonic components Ucap,kω(t)

This submodule capacitor voltage fluctuation is an inherent characteristic of MMCs, meaning the voltage provided by each submodule is not constant. Therefore, when analyzing the overload current limit of an MMC, the submodule capacitor voltage ripple limit must be considered.

2.2.2. Problem 2: Submodule Capacitor DC Component Shift

Unlike two-level converters, the DC component of the MMC submodule capacitor voltage varies with power flow, exhibiting the shift phenomenon. The submodules must dynamically exchange energy with the AC/DC system to maintain power balance within the bridge arm. This process directly reflects the rise and fall of the DC component of its capacitor voltage. Therefore, the instantaneous maximum voltage of the submodule capacitor voltage is not determined solely by the ripple, but rather by the superposition of the shift DC component and the voltage ripple peak. Therefore, when analyzing the overload current limit of the MMC, it is necessary to incorporate submodule withstand voltage constraints to ensure that, under any operating condition, the sum of these peak voltages does not exceed the maximum limit of the submodule capacitor voltage.

2.2.3. Problem 3: Complexity and Asymmetry of Modulated Signals

To achieve precise control of the AC voltage, suppress interphase circulating currents, and improve operating efficiency, the modulation signal of an MMC is significantly more complex than the sinusoidal signal of a two-level converter. The modulation signal of an MMC bridge arm typically contains three main components: DC, fundamental, and double frequency. The modulation signals Sap(t) and San(t) for the upper and lower bridge arms can be expressed as

Normally, the value of A0 is equal to 0.5. Therefore, this value is adopted for A0 throughout the remainder of this paper. Unlike two-level converters, the modulation signals of MMCs exhibit composite characteristics, requiring simultaneous achievement of dual control objectives: external power exchange and internal energy balancing. The introduction of this composite modulation mechanism results in fundamental differences between MMCs and two-level converters regarding overcurrent limitation characteristics. The injection of a second-harmonic component creates nonlinear and asymmetric modulation margins. As a result, the modulation signal is constrained by a dynamic and asymmetric boundary, rendering traditional assessment methods based on a fixed modulation index ineffective.

The above analysis demonstrates that overcurrent limitation analysis methods for two-level converters cannot be directly applied to MMCs. It is necessary to establish a multi-constraint overcurrent limitation analysis model. This model should fully consider the modulation characteristic differences of MMCs to accurately evaluate their overload capabilities.

3. Multi-Constraints in Calculating Overcurrent Limitation Boundary

3.1. Constraint of Capacitor Voltage Ripple Under Different Output Current

Taking phase A as an example, the phase voltage and phase current of the ac grid are defined as

where Us is the amplitude of the phase voltage; Is is the amplitude of the phase current; β is the phase angle of the current ia relative to the voltage ua and ω denotes the fundamental angular frequency.

The upper arm current iap(t) and the lower arm current ian(t) can be expressed in (6).

where Idc represents the DC current; Ic,2ω and θ denote the amplitude and phase angle of the circulating current in phase A.

The relationship between capacitor currents and arm currents can be expressed as follows:

where icap,ap(t) and icap,an(t) denote the capacitor currents in the upper and lower arms.

The capacitor voltages can be derived by integrating the capacitor currents, which are shown in (8)

where Ucap,0 is the dc component in the capacitor voltage; CSM is the submodule capacitance; ucap,ap,r(t) and ucap,an,r(t) denote the voltage fluctuation of the submodule capacitor in the upper and lower arms.

Substituting (3), (4), (5), (6), and (7) into (8) yields

where Ucap,0 denotes the dc component in the submodule capacitor voltage; ucap,kω(t) is the k-th harmonic component (k = 1, 2, 3, 4).

Additionally, the ucap,ap,r(t) is expressed as follows:

The ucap,kω(t) values are determined using (11).

These equations quantitatively demonstrate that the phase current of the ac grid directly influences the harmonic content and overall magnitude of the capacitor voltage fluctuations.

To ensure system stability and prevent excessive electrical stress on components, the peak-to-peak amplitude of this ripple must be strictly limited. In engineering practice, this limit is typically set to 10% of the nominal capacitor voltage. Therefore, the capacitor voltage ripple constraint is established as the first fundamental limit in the multi-constraint overcurrent analysis of the MMC. Any valid operating point must satisfy this condition. The voltage ripple constraint can be mathematically expressed as

where UN denotes the submodule capacitor rated voltage.

In summary, this subsection establishes the first physical boundary based on the capacitor voltage ripple magnitude. Equation (12) defines the maximum permissible phase current that ensures the voltage ripple amplitude remains strictly within 10% of the rated voltage, thereby preventing excessive electrical stress on the submodule capacitors.

3.2. Constraint of Capacitor Voltage Peak Considering DC Component Derivation

Unlike in conventional two-level converters, the DC component of the capacitor voltage in an MMC varies with the operating conditions. To maintain power balance between the converter arms and the AC/DC systems, the capacitors must dynamically store or release energy according to the magnitude and direction of the transmitted power. This energy exchange directly manifests as a rise or fall in the DC component of the capacitor voltage. Consequently, the peak capacitor voltage is determined by the superposition of this shifted DC component and the peak voltage ripple. It is important to note that the resistive voltage drops are omitted in the derivation of Ucap,0. For the high-voltage high-power MMC studied in this paper, the system features a high X/R ratio, rendering the resistive drop negligible compared to the DC link voltage and inductive drops during transients. This approximation simplifies the analytical model for real-time applications while providing a slightly conservative, and thus safer, overcurrent boundary by ignoring the resistive damping effect.

The capacitor voltages can be shown as follows:

The upper and lower arm voltages can be obtained from their relationships with the corresponding capacitor voltages.

Substituting (3), (6), (7), and (8) into (14), yields

where Uarm,0 denotes the dc component in the arm voltage; uarm,kω(t) is the k-th harmonic component (k = 1, 2, 3…6).

Under the assumption of negligible arm resistance and transformer equivalent resistance, establishing the power balance equation for the arm reveals that the DC component of arm voltage is approximately equal to half of the DC voltage.

Then, (16) is transformed into the form shown in (17):

The above explanation clearly shows that the submodule capacitor DC voltage Ucap,0 is not a fixed parameter but a dynamic variable dependent on the phase current magnitude Is and power factor angle β. Consequently, the ultimate voltage stress on the capacitor is determined by the superposition of this shifted DC component and the peak voltage ripple. This implies that the MMC’s overcurrent capability is constrained not only by the voltage ripple but also by the DC voltage shift resulting from active power transfer.

To ensure hardware integrity, this peak capacitor voltage must be kept within the maximum voltage rating Ucap,ap,max. In engineering practice, this value is typically set to 1.1 times the nominal capacitor voltage to provide an adequate safety margin. The formulation of the submodule overvoltage constraint is as follows:

The safety thresholds adopted in this study are selected based on typical engineering design trade-offs for large-scale MMCs. Specifically, the 10% ripple limit is chosen to strike a balance between submodule capacitor sizing—in terms of cost and volume—and thermal stress. Excessive voltage ripple leads to higher RMS currents flowing through the capacitors, which increases hotspot temperatures and accelerates component aging; thus, a 10% limit is a standard industrial practice to ensure an optimal lifespan for film capacitors. Furthermore, the 1.1× peak voltage limits are determined by the insulation coordination and the safe operating area (SOA) of the IGBTs. It serves as a “control protection threshold” that is intentionally set lower than the hardware trip threshold. This buffer zone ensures that the proposed control strategy proactively limits the current to prevent overvoltage before hard protection measures are triggered, thereby avoiding unnecessary converter tripping. It is worth noting that while these specific values are used for validation in this paper, the proposed NN-based strategy is generic and can be re-trained to accommodate any specific safety margins required by different project standards or grid codes.

To conclude, this subsection derives the capacitor voltage peak constraint by accounting for the dynamic DC component shift caused by active power transfer. Equation (18) determines the upper limit of the arm current required to maintain the instantaneous peak voltage below 1.1 times the rated value, safeguarding the submodules against overvoltage breakdown.

3.3. Constraint of Modulation Signal Considering Asymmetry Features

In addition to physical hardware limits, the MMC’s operation is constrained by its modulation signal, which must remain in the linear range to prevent saturation and ensure stability. Unlike in two-level converters, the MMC’s modulation signal is inherently asymmetric due to the injection of a second-harmonic component for circulating current suppression. This asymmetry makes traditional assessment methods based on a fixed modulation index ineffective, necessitating a precise calculation of the modulation signal Sap(t) to define the true operational boundary.

The modulation signal Sap(t) and arm current iap(t) can be expressed as a Fourier series containing DC, fundamental, and double-frequency components.

The actual voltage generated by the arm uap(t) is the product of the modulation signal and the sum of capacitor voltages. Crucially, the capacitor voltage ucap,ap(t) itself fluctuates due to the integration of capacitor current.

Substituting this back, the internal arm voltage is expressed as

Expanding this multiplication results in complex cross-coupling. For example, the interaction between the fundamental component of A1 and the fundamental fluctuation of ucap creates a DC shift and a 2nd harmonic term. This explains why the modulation parameters are highly interdependent. The internal arm voltage is also expressed as

From Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL), the external arm voltage uap(t) is determined by the grid state and circuit impedance.

The Uarm,0, uarm,1ω(t), and uarm,2ω(t), shown in (15), can be expressed as follows:

Although analytical expressions for MMC electrical quantities have been derived above, these expressions still contain multiple unknown parameters. Therefore, the steady-state values of electrical quantities cannot be directly determined from these expressions alone, and additional constraint equations must be established to solve for these unknown parameters.

To solve this differential equation, we apply the Harmonic Balance Principle. By substituting the expressions of the arm current ia(t) and grid voltage ua(t) into (26), the equation is expanded into a sum of trigonometric terms. We then separate the terms based on their angular frequencies (ω and 2ω) and orthogonality. According to the method of undetermined coefficients, the coefficients of “cos(kωt)” or “sin(kωt)” on both sides of the equation are equal [20]. Equating the coefficients of the corresponding terms on both sides yields the following set of decoupled algebraic identities, and (26) is transformed into the form shown in (27). Through the above derivation, a set of highly coupled and complex nonlinear algebraic equations is established.

Equation (27) represents a set of nonlinear algebraic equations describing the MMC’s internal electrical characteristics. To address the complex coupling, the Newton–Raphson iterative method is applied to solve for the modulation parameters numerically [21,22]. This yields the exact values of A1, A2, α1, and α2 corresponding to the operating parameters Us, Is, and β. Finally, the accurate modulation signal Sap(t) is constructed to satisfy the linear modulation constraint.

Consequently, the modulation signal Sap(t) is analytically determined as a function of the operating conditions, which can be expressed as

The main circuit parameters, including CSM, Lm, Lt, Udc, N, and ω, are pre-determined values from the converter’s design phase. The terms Ic,2ω and θ denote the amplitude and phase angle of the circulating current, respectively. This current is regulated by a Circulating Current Suppression controller, a widely adopted strategy in MMCs aimed at minimizing converter losses.

The Circulating Current Suppression Controller (CCSC) and the proposed DAOL strategy operate synergistically to maximize the converter’s fault ride-through capability. The CCSC actively suppresses the second-harmonic circulating current Ic,2ω, which contributes to arm current stress and capacitor voltage ripple but does not aid in grid support. By minimizing this non-productive component, the CCSC effectively releases additional current capacity within the converter’s thermal and voltage limits. The DAOL strategy leverages this optimized condition: it calculates the maximum permissible grid current Is under the premise that the CCSC effectively maintains Ic,2ω ≈ 0. Consequently, the suppression of circulating currents directly allows the proposed limiter to authorize a higher active/reactive current injection during faults without violating safety constraints.

It is worth noting that while the general expression in Equation (29) theoretically accounts for the circulating current terms (Ic,2ω, θ), the Circulating Current Suppression (CCS) control is typically mandatory in practical Grid-Forming MMC applications to maximize efficiency and current capability during faults. Therefore, the boundary calculation in this study assumes a well-regulated state, where Ic,2ω ≈ 0 represents the optimal operating condition for grid support. Consequently, the preceding expression can be simplified to (30).

Equation (30) reveals that the modulation signal is highly sensitive to the phase current Is. An abrupt surge in current can drive the converter into overmodulation, leading to severe voltage distortion and system instability. Therefore, to ensure stable operation, the modulation signal must be strictly confined within its linear range, establishing the third fundamental constraint:

Three key constraints are derived from the submodule voltage ripple characteristics, the capacitor voltage with stand limit, and the system modulation capability. Collectively, these constraints constitute the complete boundary conditions for the overcurrent limit of the MMC.

In summary, the modulation signal constraint is formulated to guarantee the converter’s operation within the linear modulation region. Equation (24) defines the safe operating boundary where the required output voltage vector does not drive the arm modulation signal into saturation, ensuring control stability and high waveform quality during faults.

4. Dynamic Asymmetric Overcurrent Limitation Strategy for Grid-Forming MMC Considering Grid Voltage Variation

4.1. Analysis of the Multi-Constraint Dynamic Overcurrent Boundary

During grid-side faults, the conventional current limiting methods with fixed values are insufficient to ensure the safe operation of GFM-MMCs under such dynamic conditions. It is necessary to establish an overcurrent limit boundary derived from the MMC’s intrinsic physical constraints, which dynamically adjusts with operating conditions. This boundary is jointly determined by three core physical constraints: the modulation signal limit, the capacitor voltage peak limit, and the capacitor voltage ripple limit. The specific constraint equations are expressed as follows:

Additionally, it must be considered that the grid-side voltage Us of a GFM-MMC undergoes significant variations during grid faults, which directly impact the converter’s internal operating state. To ensure safe operation under all conditions, the proposed overcurrent limit boundary must dynamically adapt according to real-time variables, notably the grid-side voltage Us and the current phase angle β. Concurrently, the MMC is required to satisfy all the aforementioned physical constraints simultaneously. Therefore, the unified dynamic overcurrent boundary can be expressed as

where Icap,rip, Icap,max and Isig denotes the maximum phase current amplitude that satisfies the capacitor voltage peak constraint, voltage ripple constraint, and modulation signal constraint under the given voltage Us and current phase angle β, respectively; Il denotes the maximum phase current amplitude meeting all three constraints simultaneously. It is important to note that the sub-boundary currents Icap,rip, Icap,max and Isig are derived from the nonlinear constraints established in Section 3.

Due to the transcendental nature of the equations involving trigonometric functions and coupled variables, obtaining explicit closed-form analytical solutions for these currents is mathematically intractable. Consequently, in this study, these sub-results are not solved analytically but are computed using offline numerical iteration methods (e.g., the Newton-Raphson method) to generate the precise dataset for neural network training. The specific constraint that dominates the unified boundary is mathematically determined by the intersection points of the individual limit curves. This switching behavior is strictly governed by the physical coupling between the current phase angle β and the submodule DC voltage shift derived. Specifically, in operating regions dominated by reactive power absorption, the significant positive DC voltage shift superimposes with the voltage ripple, causing the capacitor peak voltage constraint to trigger first. Conversely, during active power injection, where the DC voltage shift is minimized, the safe operating area is primarily restricted by the voltage ripple limit or the modulation linearity limit. This analytical dependence confirms that the proposed strategy dynamically identifies and enforces the most critical physical bottleneck based on the instantaneous state of the converter.

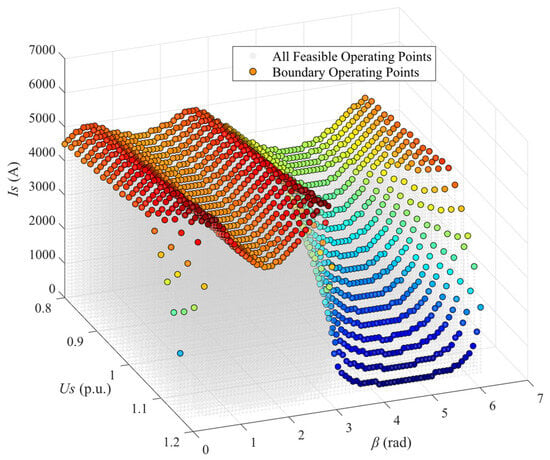

In practical operating conditions, the grid-side voltage Us typically varies within the range of 0.8 per-unit (p.u.) to 1.2 p.u. This study focuses on solving for the boundary conditions within this specific voltage range. The operating points on the dynamic overcurrent limit boundary are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The operating points on the dynamic overcurrent limitation boundary.

Figure 3 illustrates the dynamic current limit boundary, which exhibits three key features. First, the boundary is complex, nonlinear, and coupled with both grid voltage Us and current phase angle β, reflecting the intricate nature of MMC’s multi-constraint operation. Second, the dominant constraint changes with the phase angle β. Near pure reactive power injection, where β is approximately π/2, the limit is set by the capacitor voltage ripple or the modulation signal. In the opposite reactive power direction, where β is approximately 3π/2, the peak capacitor voltage limit becomes the bottleneck. Third, the allowable current boundary narrows as the grid voltage Us drops, preventing overmodulation and capacitor over-voltage. These characteristics underscore the necessity of a dynamic, multi-constraint strategy over traditional fixed-value methods.

The overcurrent boundary generated based on the aforementioned physical constraints is dynamic and asymmetric. Its dynamic nature is manifested in the boundary’s ability to adapt in real-time to varying operating conditions, ensuring the current limits are always optimized for the present state of the system. The asymmetric characteristic reflects the departure from the simplistic circular dq limit, meaning the converter’s true operational envelope is non-uniform. By leveraging this dynamic and asymmetric boundary, the control strategy allows the MMC to operate safely up to its true physical limit.

4.2. Neural Network-Based Construction of the Dynamic and Asymmetric Overcurrent Limitation Strategy

The analytically derived overcurrent boundary is too complex for direct implementation within the MMC’s microsecond-level control loop. Conventional methods like polynomial fitting are inaccurate, while Look-Up Tables are memory-intensive and imprecise.

In light of these limitations, this paper proposes the use of a neural network to serve as a real-time function approximator for the dynamic and asymmetric boundary. The neural network is trained offline to learn the complex, nonlinear boundary. Once trained, its real-time execution is extremely fast, easily meeting the controller’s stringent timing requirements. The function fitted by the neural network can be expressed as follows:

where In denotes the maximum current limit predicted by the neural network under the given voltage Us and current phase angle β.

To ensure the reproducibility and reliability of the proposed strategy, the specific implementation details of the neural network are strictly defined. The training dataset was generated by numerically solving the physical constraint models derived in Section 3 using the Newton–Raphson method. The operational space was traversed with high resolution to cover all potential fault scenarios: the grid voltage Us ranges from 0.8 to 1.2 p.u. with a step size of 0.01 p.u., and the current phase angle β ranges from 0 to 2π with a step size of 1°, resulting in a total of 14,760 verified operating points.

Considering the highly nonlinear, saddle-shaped characteristics of the overcurrent boundary, a deep feed-forward neural network (DNN) architecture was selected. The network consists of an input layer (2 neurons), four hidden layers with a tapered structure of 8-10-15-20 neurons, respectively, and a linear output layer. The Tan–Sigmoid activation function is utilized in hidden layers to capture nonlinear features, while the output layer employs a linear function to generate the continuous current limit ILim.

The network was trained using the Bayesian Regularization algorithm, which was chosen for its superior generalization capabilities and robustness against overfitting—critical attributes for protection-related control. Z-score normalization was applied to both input and output variables to accelerate convergence. The training process was conducted for 1500 epochs. The final model achieved a root mean square error (RMSE) of less than 1.2 × 10−4 and a coefficient of determination R2 of more than 0.999 on an independent test set, confirming that the neural network reproduces the analytical physical model with negligible error. The key parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters and training details of the neural network.

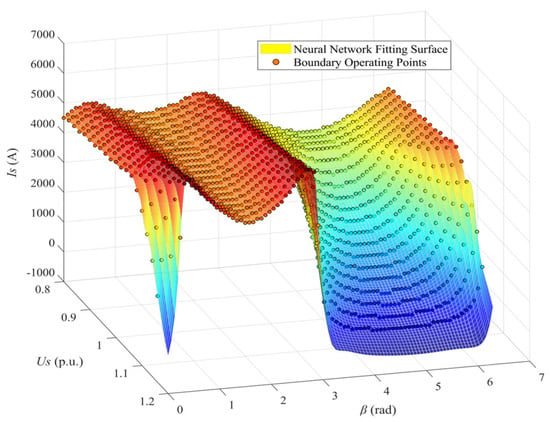

Figure 4 compares the discrete operating points on the current limit boundary, derived from analytical calculations, with the continuous fitted surface generated by the neural network under various grid voltage conditions.

Figure 4.

Dynamic and asymmetric overcurrent limitation surface fitted by the neural network.

As shown in the figure, a clear and high degree of consistency is observed between the NN-generated surface and the analytically calculated points across the entire operating range. Notably, the NN maintains precise tracking even in regions where the boundary curvature changes abruptly and the dominant physical constraint shifts. This high-fidelity fitting performance demonstrates that the trained NN model can accurately reproduce the complex dynamic and asymmetric overcurrent limit boundary with an acceptable engineering error.

It is worth noting that since the neural network is trained offline, its online implementation functions essentially as a lookup table or a simple function approximator involving only basic matrix operations. This process requires minimal memory and computational resources, allowing for fast execution on standard digital controllers and ensuring high compatibility with existing control platforms without requiring hardware upgrades.

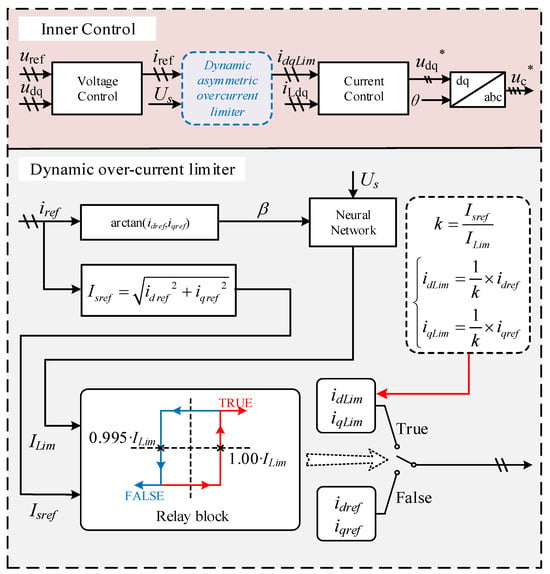

To ensure the safe operation of the MMC while maximizing its dynamic response performance, this paper proposes a dynamic current limiter. Its core idea is to utilize a pre-trained neural network to determine the dynamic and asymmetric current limit in real-time and precisely constrain the current reference command before it enters the inner-loop controller. This proactive protection mechanism prevents the controller from issuing out-of-bounds commands at the source, thereby averting overcurrent events. The implementation and operational principle of this limiter within the control system are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Control block diagram of the proposed dynamic asymmetric overcurrent limitation strategy.

As shown in the figure, in contrast to conventional fixed-value limiting, the limit of this stage is dynamic. Its boundary is not a fixed constant but is determined in real-time by a neural network with the grid voltage magnitude Us and current phase angle β as inputs.

4.3. Calculation Module for Dynamic Overcurrent Limitation

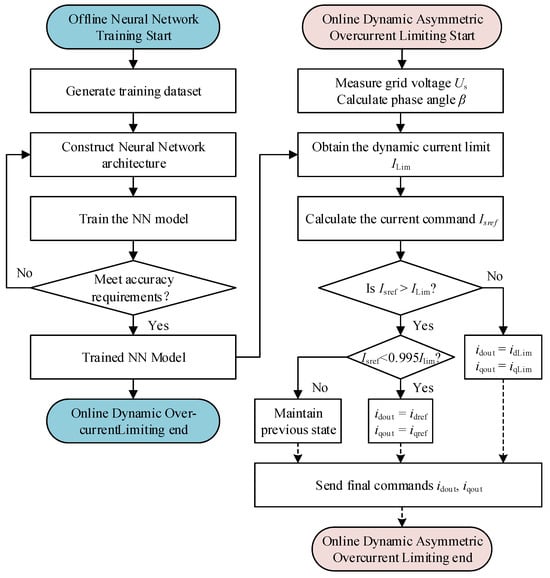

To guarantee a real-time protection response, the dynamic limiting module is executed every control sampling period. The complete procedure for calculating the dynamic overcurrent limitation is shown in Figure 6, with the detailed calculation steps outlined as follows.

Figure 6.

Procedure for calculating the dynamic asymmetric overcurrent limitation.

- The inputs comprise the measured grid voltage magnitude Us and current phase angle β. Notably, β is not a measured value but is derived in real-time from the d-q axis current commands idref and iqref issued by the high-level controller. The calculation formula can be expressed as follows:

This approach focuses on limiting the controller’s command intent at the source, as opposed to reacting to an existing overcurrent. Consequently, it preemptively blocks the generation of boundary-violating commands, offering a fundamentally more forward-looking alternative to traditional reactive methods.

- 2.

- The real-time input vector [Us, β] is fed into the neural network model embedded within the controller. The model then performs a single, rapid feed-forward pass to yield the unified current limit ILim, corresponding to the current operating point.

- 3.

- The magnitude of the current command is computed using the equation below. This value is then compared with the current limit ILim provided by the neural network.

- 4.

- When the command magnitude Isref does not exceed the limit ILim, the limiter is bypassed, and the original command references are passed through unmodified.

- 5.

- When the command magnitude Isref is not less than 0.955 ILim and does not exceed ILim, it is considered to be within the relay block. To avoid control chattering, the limiter’s state is maintained from the previous cycle.

- 6.

- When the command magnitude Isref exceeds the limit ILim, a limiting action is triggered. To preserve the current phase angle β and thus the intended power distribution, the command vector is proportionally scaled down. The scaling factor k and the resulting limited commands are determined as follows:

This approach ensures the command vector is smoothly constrained to the dynamic asymmetric boundary, guaranteeing operational safety while fully leveraging the converter’s instantaneous output capability.

- 7.

- The resulting limited references idout and iqout then serve as the inputs for the MMC’s inner-loop current controller.

5. Case Study

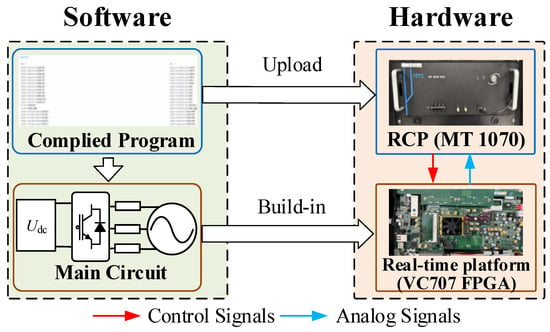

In this section, a control hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experimental platform is established to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The core principle of this platform is to decouple the computationally intensive part, which requires an extremely small simulation step, from the control strategy calculation part to achieve efficient and precise real-time simulation. Specifically, the system is divided into two parts. The main circuit simulation is realized by a Xilinx VC707 Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) board (Xilinx, San Jose, CA, USA), which implements the main circuit model of the MMC. To meet the requirements of high-precision simulation, the circuit model within the FPGA runs in a hardware synchronization mode with a physical clock and an extremely small simulation step.

The control signals are generated by an ARM Cortex-A9 processor embedded in the MT 1070 Rapid Control Prototype (RCP). The control algorithm is executed within the RCP’s processor, and its calculation period can be configured according to the requirements of the control strategy.

This HIL platform constitutes a complete closed-loop real-time environment in the following manner: the states of the main circuit simulated in the FPGA are sampled and transferred to the RCP as feedback analog signals; based on these feedback signals and the predefined control strategy, the RCP calculates the required drive signals; these drive signals are then sent from the output pins of the RCP back to the FPGA and applied to the main circuit model. The overall structure of the HIL platform is illustrated in Figure 7. Through this configuration of combined hardware and software, the entire control loop is closed as a full-time running environment, thereby enabling the acquisition of highly representative experimental results.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the HIL setup.

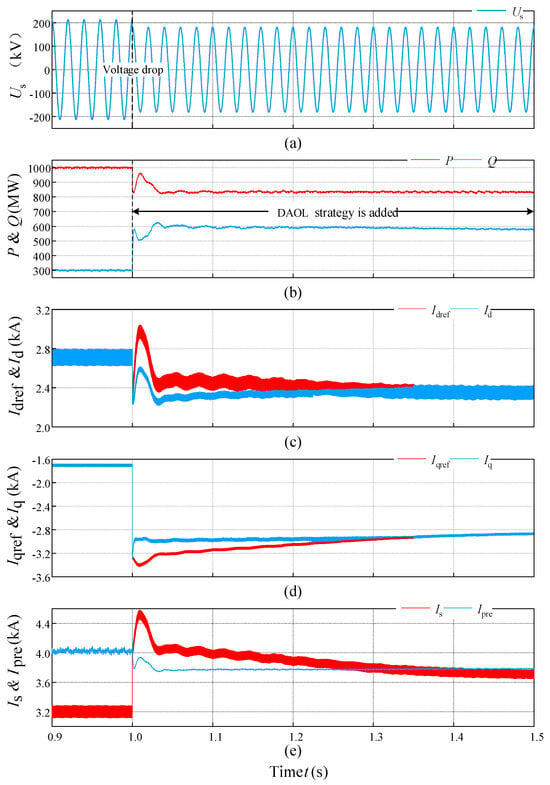

5.1. Experimental Validation of the DAOL Strategy

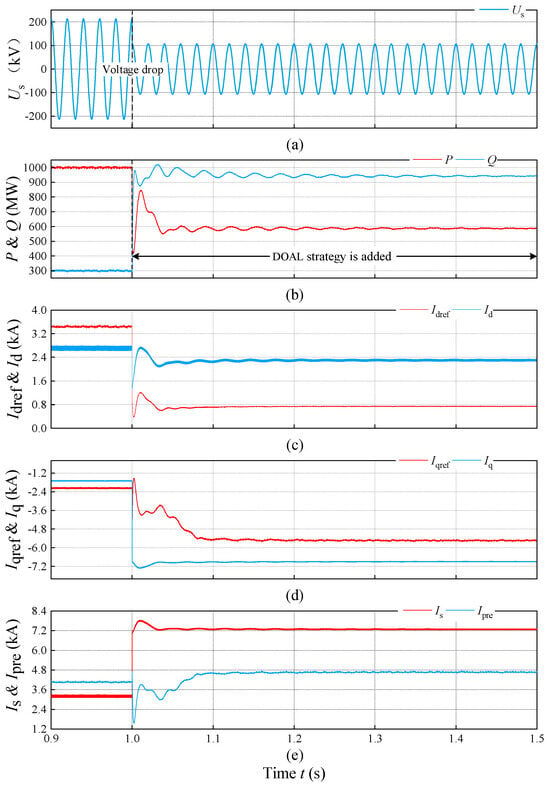

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed dynamic asymmetric overcurrent-limiting (DAOL) strategy, a symmetrical three-phase voltage drop scenario was tested. Initially, the system operates in a steady state at rated power. At t = 1.0 s, the grid voltage Us at the point of common coupling experiences a sudden drop from 1.0 p.u. to 0.85 p.u. The corresponding waveforms are presented in Figure 8. The detailed parameters of the investigated system are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 8.

(a) Grid voltage waveforms during a 0.85 p.u. voltage drop; (b) Active and reactive power responses during a 0.85 p.u. voltage drop; (c) d-axis current and its reference during a 0.85 p.u. voltage drop; (d) q-axis current and its reference during a 0.85 p.u. voltage drop; (e) Output phase current and dynamic current limit during a 0.85 p.u. voltage drop.

Table 2.

Main circuit parameters of the MMC.

The comparative results are presented in Figure 8. As depicted in Figure 8a, upon the voltage drop to 0.85 p.u., the high-level controller immediately demands a substantial increase in reactive current for grid support. This is evidenced by the reactive power Q rapidly increasing from 300 Mvar to a new steady-state value of approximately 600 Mvar, which in turn translates to a sharp drop in the q-axis current reference iqref in Figure 8c.

In response to this demand, the proposed DAOL strategy intervenes proactively. Instead of crudely clipping the current, the strategy first calculates a new, more restrictive dynamic current limit ipre of approximately 3.75 kA, as shown in Figure 8d. This boundary accurately reflects the reduced operational capability of the converter under the drop condition. Subsequently, it employs a proportional scaling mechanism to smoothly constrain the output current, Is, below this dynamic asymmetric boundary. This approach preserves the dynamic power distribution intended by the upper-level controller, ensuring control coordination while prioritizing reactive power support.

Detailed quantitative analysis of the dynamic response confirms the effectiveness of the DAOL strategy. As observed in Figure 8c, the initial transient spike in the d-axis current reference idref is suppressed from 3.04 kA to 2.6 kA, representing an overshoot reduction of approximately 14.5%. Furthermore, the system demonstrates excellent damping characteristics, with a settling time of approximately 250 ms, after which the oscillations are fully attenuated. The iqref is similarly constrained from −3.4 kA to −3.2 kA. Both references are then guided to new, safe steady-state values, effectively mitigating the transient impact on the converter. Ultimately, the DAOL strategy provides direct and proactive protection for internal physical quantities via an accurate boundary model. Throughout the entire transient process, this ensures the peak capacitor voltage is strictly maintained within its physical limit, thereby mitigating voltage stress while simultaneously maximizing the permissible current injection for grid support.

To further verify the robustness of the proposed strategy under severe faults, a 0.5 p.u. deep voltage dip scenario was tested. The results are shown in Figure 9. In this scenario, the grid voltage drops to 50% of the nominal value, significantly reducing the converter’s linear operating region. The proposed DAOL strategy proactively adjusts the current limit to a lower safe value, ensuring the modulation signal remains within the linear range, whereas the traditional method fails to prevent overmodulation, leading to potential instability. This confirms the method’s effectiveness under varying fault depths.

Figure 9.

(a) Grid voltage waveforms during a 0.5 p.u. voltage drop; (b) Active and reactive power responses during a 0.5 p.u. voltage drop; (c) d-axis current and its reference during a 0.5 p.u. voltage drop; (d) q-axis current and its reference during a 0.5 p.u. voltage drop; (e) Output phase current and dynamic current limit during a 0.5 p.u. voltage drop.

Figure 9 presents the experimental results under a severe 0.5 p.u. symmetric voltage dip, simulating a deep fault scenario. As shown in Figure 9a, the grid voltage amplitude drops instantly by 50% at t = 1.0 s. Under such a significant disturbance, the outer-loop power controller attempts to compensate for the voltage loss by demanding a massive current injection to maintain the power setpoint. Consequently, the unconstrained current reference magnitude Is surges drastically, reaching a theoretical peak of approximately 7.2 kA, as illustrated by the red trace in Figure 9e. This value far exceeds the converter’s rated capacity and would typically trigger an immediate overcurrent trip or device damage.

However, the proposed DAOL strategy effectively handles this extreme condition. By sensing the deep voltage sag and the phase angle state, the neural network instantly calculates a constricted safety boundary Ipre, represented by the blue trace in Figure 9e, which stabilizes at approximately 4.6 kA. The strategy proactively clamps the current reference to this dynamic limit, intercepting the potential 7.2 kA surge. As a result, the converter rides through the fault safely without saturation. Despite the severity of the dip, the system maintains stable operation, injecting approximately 600 Mvar of reactive power for grid support while active power settles at a reduced but stable level of 820 MW, demonstrating the method’s strong robustness under deep voltage dip conditions.

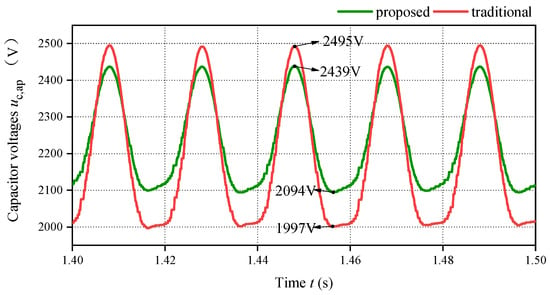

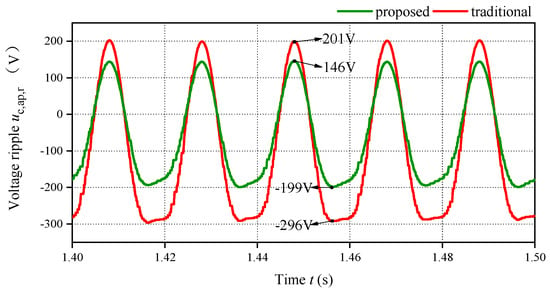

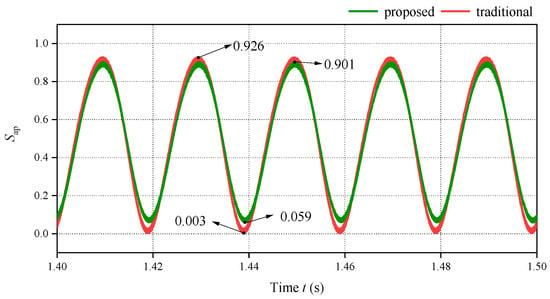

5.2. Comparisons with Traditional Methods

To further validate the superiority of the proposed current-limiting strategy, a steady-state comparison between the proposed DAOL strategy and a traditional limiting method is presented, focusing on three key physical constraints: the capacitor voltage, voltage ripple, and arm modulation signal.

The comparative steady-state waveforms of the phase A upper arm capacitor voltage are shown in Figure 10. As illustrated, with the traditional strategy, although the output current is limited, the internal dynamics lead to a significant increase in capacitor voltage, with the peak value reaching 2495 V. While this does not exceed the 1.1 times rated voltage limit, it approaches this boundary very closely. In contrast, the peak voltage under the proposed DAOL strategy stabilizes at only 2439 V. This demonstrates that the proposed method can effectively reduce the peak capacitor voltage, thereby lowering the breakdown risk for the capacitors.

Figure 10.

Comparative steady-state waveforms of the phase A upper arm capacitor voltage.

Furthermore, the electrical stress on the capacitors is also revealed by the voltage ripple, as illustrated in Figure 11. The large fault current demanded by the traditional strategy results in an excessive voltage ripple, with an amplitude of 249 V. This value clearly exceeds the prescribed safety limit of 229 V, subjecting the capacitors to high electrical stress that can accelerate component aging and shorten the system’s lifespan. In contrast, by leveraging its precise boundary awareness, the DAOL strategy constrains the capacitor voltage ripple to only 172.5 V, a 30.7% reduction compared to the traditional approach. This significant suppression is achieved because the proposed limiter proactively adjusts the arm current reference based on the instantaneous grid voltage. By preventing the injection of excessive current that contributes to the charging-discharging imbalance of the submodules, the strategy effectively minimizes the energy fluctuations stored in the capacitors.

Figure 11.

Comparative steady-state waveforms of the phase A upper arm capacitor voltage ripple.

Figure 12 displays the arm modulation signals of the phase A upper arm for the two current-limiting methods. As illustrated, the traditional strategy forces the modulation signal to operate in a hazardous range near its saturation limit, with the minimum value reaching 0.003. This indicates that the system is on the verge of overmodulation, a condition prompted by its attempt to compensate for the grid voltage drop by demanding a large internal voltage. Operating near saturation can lead to significant harmonic distortion and potential instability. Conversely, the DAOL strategy incorporates modulation signal constraints directly into its boundary model. As a result, the modulation signal is confined between 0.059 and 0.901, ensuring that a safe margin from the saturation limits is maintained. This guarantees linear operation and preserves high control quality throughout the transient event.

Figure 12.

Comparative steady-state waveforms of the phase A upper arm modulation signal.

The above experimental results validate that the proposed DAOL strategy can effectively enhance both system safety and fault ride-through performance.

To further validate the superiority of the proposed current-limiting strategy (DAOL), a comprehensive quantitative comparison between the DAOL strategy and the traditional limiting method is presented. Table 3 summarizes the key performance metrics, specifically focusing on the capacitor voltage safety margin, modulation signal quality, and computational efficiency.

Table 3.

Summary of quantitative performance comparisons between the traditional method and the proposed DAOL strategy.

As detailed in Table 3, the traditional strategy results in a peak capacitor voltage of 2495 V. Given the safety threshold of 2.523 kV, the traditional method leaves a perilously narrow safety margin of only 28 V. In contrast, the DAOL strategy stabilizes the peak voltage at 2439 V, effectively expanding the safety margin to 84 V, which represents a 3.0-fold improvement in safety redundancy.

Regarding the modulation stability, the traditional method forces the modulation signal to a minimum of 0.0033, pushing the system to the verge of saturation. This nonlinearity results in increased harmonic distortion, with the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of the arm modulation signals deteriorating to 11.27%. Conversely, the DAOL strategy maintains the modulation signal well within the linear region, resulting in a superior THD of 7.54%. Furthermore, to address the concern regarding implementation complexity, the real-time execution time of the proposed neural network-based limiter was measured. The forward propagation takes only 3 μs per control cycle. This computational load is negligible compared to the typical control period, confirming the feasibility of the proposed strategy for real-time applications.

6. Conclusions

A dynamic asymmetric overcurrent-limiting strategy for grid-forming MMCs that considers multiple physical constraints is proposed in this paper. The core mechanism and implementation are summarized as follows:

- The overcurrent capability of an MMC is not determined by a single fixed value, but by a complex, dynamic boundary. This boundary is jointly defined by three core internal physical constraints: the capacitor voltage ripple, the capacitor voltage peak, and the modulation signal limit. Each constraint dominates the boundary under different operating conditions, particularly varying with grid voltage Us and current phase angle β.

- To apply this complex boundary in real-time control, an offline-trained neural network is introduced as a high-precision function approximator. This approach effectively decouples the computationally intensive boundary calculation from the online control loop, enabling the strategy to be implemented efficiently without modifying the main circuit topology.

- Based on the neural network, a dynamic asymmetric limiter is designed. It proactively calculates the current limit ILim based on real-time Us and the command-derived β, and then proportionally scales the current reference. This ensures that the control commands always adhere to the MMC’s true safe operating area, maximizing grid support while guaranteeing internal safety.

The effectiveness and superiority of the proposed dynamic asymmetric overcurrent-limiting (DAOL) strategy were rigorously verified through hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experiments and compared against a traditional current-limiting method. The results demonstrate that under a grid voltage drop to 0.85 p.u., the proposed strategy can smoothly constrain the output current within the dynamically calculated safety boundary.

Crucially, the proposed DAOL strategy exhibits significant advantages in respecting the MMC’s internal physical limits. Compared to the traditional method, the peak capacitor voltage was reduced from 2495 V to 2439 V, providing a larger safety margin against overvoltage. Furthermore, the capacitor voltage ripple was suppressed from an excessive 249 V down to a safe level of 172.5 V, a reduction of 30.7%, which mitigates electrical stress and enhances component lifespan. The modulation signal was also maintained well within the linear range 0.059 to 0.901, avoiding the risk of overmodulation and ensuring high control quality. These results collectively prove that the proposed strategy achieves optimal dynamic current support during grid faults while strictly adhering to the MMC’s multiple internal constraints. This approach significantly enhances both system safety and fault ride-through performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.C.; methodology, Y.L.; software, F.X.; validation, F.Z. and M.H.; investigation, G.W.; data curation, Q.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.C.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the State Grid Corporation of China Headquarters Science and Technology Project (5500-202419133A-1-1-ZN).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qian Chen, Yi Lu, Feng Xu, Fan Zhang, and Mingyue Han were employed by the State Grid Corporation of China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the State Grid Corporation of China Headquarters Science and Technology Project (5500-202419133A-1-1-ZN). The funder had the following involvement with the study: Conceptualization, Q.C.; methodology, Y.L.; software, F.X.; validation, F.Z. and M.H.; data curation, Q.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.C.; visualization, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Zhan, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y. An overview of stability studies of grid-forming voltage source converters. In Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering; Chinese Society for Electrical Engineering: Beijing, China, 2023; Volume 43, pp. 2339–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yu, S.; Sun, D.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. An overview of control technologies and principles for grid-forming converters. In Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering; Chinese Society for Electrical Engineering: Beijing, China, 2024; Volume 44, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Dey, S.H.N.; Chowdhury, S.P. A literature review on integration of distributed energy resources in the perspective of control, protection and stability of microgrid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5545–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Pal, D.; Panigrahi, B.K. A Current Saturation Strategy for Enhancing the Low Voltage Ride-Through Capability of Grid-Forming Inverters. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, T.; Farjah, E. Development of an Efficient Solid-State Fault Current Limiter for Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Liu, T.; Zhao, F.; Wu, H.; Wang, X. A Review of Current-Limiting Control of Grid-Forming Inverters Under Symmetrical Disturbances. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2022, 3, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.; Moreira, C.L.; Lopes, J.A.P. Grid-Forming Inverters Sizing in Islanded Power Systems—A stability perspective. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST), Porto, Portugal, 9–11 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Liang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Kang, Y. A Current Limiting Strategy With Parallel Virtual Impedance for Three-Phase Three-Leg Inverter Under Asymmetrical Short-Circuit Fault to Improve the Controllable Capability of Fault Currents. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 8138–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liang, R.; Zhang, Z. Adaptive Virtual Impedance Current Limiting Strategy for Grid-Forming Converter. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Tianjin, China, 14–16 April 2023; pp. 653–657. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.; Wang, X. Fault Recovery Analysis of Grid-Forming Inverters With Priority-Based Current Limiters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5102–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, X. Small-Signal Modeling and Controller Parameters Tuning of Grid-Forming VSCs with Adaptive Virtual Impedance-Based Current Limitation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7185–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemink, J.M.; Iravani, M.R. Control of a Multiple Source Microgrid With Built-in Islanding Detection and Current Limiting. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taul, M.G.; Wang, X.; Davari, P.; Blaabjerg, F. Current Limiting Control With Enhanced Dynamics of Grid-Forming Converters During Fault Conditions. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 1062–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Yi, W.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Wu, W.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, C.; Liu, A. Harmonic Current and Inrush Fault Current Coordinated Suppression Method for VSG Under Non-ideal Grid Condition. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytes, J.; Li, J.; de Préville, G.; Thouvenin, M. Grid-Forming Control With Current Limitation for MMC Under Unbalanced Fault Ride-Through. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 3292–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, W.; Farhan, M.; Bhatti, A.R.; Butt, A.D.; Farid, G. A modified control strategy for seamless switching of virtual synchronous generator-based inverter using frequency, phase, and voltage regulation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Hao, Q.; Wang, S. Operating Area of Modular Multilevel Converter Station Considering the Constraint of Internal Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th IEEE Workshop on the Electronic Grid (eGRID), Xiamen, China, 11–14 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Lin, W.; Wen, J.; Yao, W.; An, T.; Li, Y. Dynamic phasor modelling and operating characteristic analysis of half-bridge MMC. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC-ECCE Asia), Hefei, China, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 2615–2621. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Tao, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Blaabjerg, F.; Wang, P. Joint Limiting Control Strategy Based on Virtual Impedance Shaping for Suppressing DC Fault Current and Arm Current in MMC-HVDC Systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, K.-J.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Javid, Z.; Wang, Z.-D. General Model of Modular Multilevel Converter for Analyzing the Steady-State Performance Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Jiang, Q. Impedance-Based AC/DC Terminal Modeling and Analysis of the MMC-BTB System. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 4359–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.R.; Vittal, V. Harmonic Domain Periodic Steady-State Modeling of Power Electronics Apparatus: SVC and TCSC. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2000, 15, 660–666. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.