Abstract

Under varying operating conditions, motor bearings undergo continuous changes, necessitating the development of deep learning models capable of robust fault diagnosis. While meta-learning can enhance generalization in low-data scenarios, it is often susceptible to overfitting. Domain adaptation mitigates this by aligning feature distributions across domains; however, most existing methods primarily focus on global alignment, overlooking intra-class subdomain variations. To address these limitations, we propose a novel Dynamic Balance Domain-Adaptation based Few-shot Diagnosis framework (DBDA-FD), which incorporates both global and subdomain alignment mechanisms along with a dynamic balancing factor that adaptively adjusts their relative contributions during training. Furthermore, the proposed framework implicitly leverages the concept of symmetry in feature distributions. By simultaneously aligning global and subdomain-level representations, DBDA-FD enforces a symmetric structure between source and target domains, which enhances generalization and stability under varying operational conditions. Extensive experiments on the CWRU and PU datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of DBDA-FD, achieving 97.6% and 97.3% accuracy on five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot tasks, respectively. Compared to state-of-the-art baselines such as PMML and ADMTL, our method achieves up to 1.4% improvement in accuracy while also exhibiting enhanced robustness against domain shifts and class imbalance.

1. Introduction

The fault diagnosis of rolling bearings is critical across key sectors such as industrial manufacturing, aerospace, energy, and transportation, as bearing performance directly impacts system safety, stability, and lifespan. However, external loads, friction, and structural fatigue during prolonged operation often cause failures such as bearing wear, gear fractures, and rotor imbalance. If not promptly detected and diagnosed, these failures can lead to reduced performance, increased energy consumption, or even catastrophic accidents [1,2]. Therefore, research into bearing fault diagnosis is of both significant engineering value and vital importance to the efficient operation of modern industrial systems.

Traditional fault diagnosis methods mainly rely on signal processing and statistical techniques such as time-domain, frequency-domain, and time–frequency analysis. These approaches extract feature parameters from signals to identify faults but often depend heavily on expert knowledge and are susceptible to noise, leading to reduced diagnostic accuracy and reliability, especially under complex and variable operating conditions. To overcome these limitations, data-driven methods have gained traction. Compared to traditional approaches, machine learning techniques offer stronger self-learning capabilities, enabling the automatic discovery of underlying patterns in large datasets while reducing dependence on domain expertise. In bearing fault diagnosis, supervised learning methods such as support vector machines (SVM) [3] and k-nearest neighbors (kNN) [4] have shown the ability to classify faults based on features extracted from vibration signals, providing accurate and reliable solutions. Despite overcoming some limitations of traditional methods, machine learning approaches still face challenges when dealing with high-dimensional, complex signals, particularly in low-data regimes.

To overcome these challenges and enhance feature extraction in complex signal environments, deep learning methods have been increasingly explored. Deep learning has shown great promise in this domain due to its powerful feature learning capabilities. CNNs [5] excel at extracting spatiotemporal features, RNNs [6] and LSTMs [7] effectively capture temporal dependencies, and Transformers [8] leverage self-attention mechanisms to enhance the modeling of long-sequence data. These advancements have significantly boosted the capabilities of intelligent fault diagnosis, especially under big data scenarios. However, in practical industrial settings, two key challenges persist: (1) limited labeled fault samples in the target domain, and (2) significant domain shifts caused by varying operating conditions, load levels, or sensor settings. These issues lead to distribution mismatch and poor generalization of diagnostic models trained in source domains.

To address this, few-shot domain adaptation (FSDA) has emerged as a promising direction, aiming to leverage limited target samples to enable cross-domain generalization. Several recent studies have combined meta-learning with domain adaptation to improve performance in FSDA settings. For example, ADMTL [9] introduces attention-based meta-transfer learning to reuse source knowledge in new tasks, while PMML [10] employs prototype-based matching to facilitate few-shot fault classification. These methods demonstrate the effectiveness of episodic training and representation reuse.

However, two important limitations remain unresolved: (1) GlBA-only alignment: Most existing domain adaptation methods rely on aligning global feature distributions via adversarial training or maximum mean discrepancy. These approaches fail to consider intra-class variations that naturally exist across different operational modes within the same fault category. Ignoring these subdomain discrepancies often leads to feature distortion or negative transfer [10]. Recent studies [11,12] have further emphasized that global alignment techniques often fail to preserve class-conditional structures and inter-class margins across subdomains, highlighting the need for subdomain-level feature adaptation in practical diagnostic settings. (2) Static alignment weights: prior methods typically use fixed loss weights to balance domain adaptation and classification losses and lack flexibility in dynamic FSDA scenarios where the domain shift severity and task difficulty vary across episodes.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a novel meta-learning based framework named Dynamic Balance Domain-Adaptation based Few-shot Diagnosis (DBDA-FD). Our approach explicitly incorporates both global and subdomain adversarial alignment mechanisms to improve feature matching fidelity. A dynamic balance factor is further introduced to adaptively modulate the importance of global vs. subdomain alignment during training. This enables our model to dynamically focus on more critical alignment levels according to domain discrepancy and task complexity. From a broader perspective, symmetry plays a critical role in various scientific domains, including physics, biology, and artificial intelligence. In the context of fault diagnosis, symmetry can be interpreted as the consistency or invariance in feature distributions across different domains and fault conditions. Our proposed method exploits this notion by enforcing symmetric alignment between the source and target domain features at both global and subdomain levels, leading to more robust and transferable representations for few-shot learning scenarios. Extensive experiments on the benchmark CWRU and PU datasets have demonstrated that DBDA-FD consistently outperforms existing methods in both five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot diagnostic tasks. Our model achieves over 97.6% accuracy and shows significant improvements in robustness under severe domain shifts and class imbalance conditions.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Dual-Level Alignment: We propose a novel few-shot diagnosis framework named DBDA-FD, which for the first time integrates both global and subdomain adversarial alignment into a meta-learning structure. This enables more fine-grained feature alignment and better handling of domain shifts across diverse working conditions.

- Dynamic Balance Factor: A dynamic balancing factor is introduced to adaptively weigh global and subdomain alignment losses during adversarial training. This mechanism enhances feature transferability while mitigating overfitting, especially under data imbalance.

- Superior Performance: Extensive experiments on CWRU and PU datasets show that DBDA-FD achieves 97.6% and 97.3% accuracy on five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot tasks, respectively, outperforming recent SOTA methods including ADMTL and PMML by 0.6–1.4%.

2. Related Work

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been widely adopted in mechanical fault diagnosis due to their powerful feature extraction capabilities. Unlike traditional methods that rely on handcrafted features, CNNs enable end-to-end learning of critical local patterns, making them particularly effective for time–frequency images and vibration signal pattern recognition. Ince et al. [13] proposed a real-time motor fault detection method based on one-dimensional CNN (1D-CNN) that directly processes raw current signals without additional feature extraction, learning temporal features through multiple convolutional and pooling layers for efficient classification. Zhu et al. [14] employed the symmetrized dot pattern (SDP) technique to convert rotor vibration signals into visual representations, enabling CNN-based feature extraction and enhancing adaptability to complex signal patterns. Iqbal et al. [15] integrated vibration and acoustic signals, constructing time–frequency maps via short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and feeding them into CNNs for feature extraction and classification, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy under multimodal inputs. Addressing computational complexity, Pan et al. [16] developed a lightweight CNN (LW-CNN) for real-time intelligent diagnosis, optimizing network architecture to reduce computational costs and employing sliding window-based data augmentation to enhance generalization. Zhong et al. [17] further combined transfer learning and self-attention mechanisms, proposing a lightweight CNN (SLCNN) where vibration signals are transformed into time–frequency images using continuous wavelet transform (CWT), a self-attention module (SAM) is embedded into an optimized SqueezeNet architecture, and parameters are transferred from ImageNet pre-trained models, achieving high classification accuracy even with limited training data. These studies demonstrate that CNNs and their variants exhibit strong feature extraction and classification capabilities, particularly suited for time–frequency image-based fault detection.

For vibration signals and other time-series data, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants, such as long short-term memory networks (LSTM), are valuable for capturing long-term dependencies, proving effective in mechanical fault prediction and diagnosis. Yang et al. [18] proposed an LSTM-based fault diagnosis approach by first converting sensor data from rotating machinery to the frequency domain, applying sparse representation and random projection for dimensionality reduction and subsequently modeling temporal relationships using LSTM for accurate classification. Sabir et al. [19] utilized LSTM to directly model stator current signals, effectively capturing sequential features and enhancing bearing fault diagnosis accuracy. Zhang et al. [6] introduced a method combining gated recurrent units (GRUs) by converting time-series vibration signals into two-dimensional images, using GRUs to learn key temporal information and employing multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) for classification, effectively integrating temporal and spatial features. Additionally, Pan et al. [20] proposed a hybrid 1D-CNN and LSTM model, where CNN extracts local features and LSTM models long-term dependencies for accurate bearing fault classification. Khorram et al. [21] developed an end-to-end CNN-LSTM model that directly processes accelerometer vibration signals without the need for explicit feature extraction, where CNN learns local features and LSTM captures long-range dependencies, thus avoiding reliance on traditional preprocessing. Overall, LSTM and its variants exhibit strong modeling capabilities for time-series data, mitigating gradient vanishing issues typical in traditional RNNs and achieving outstanding performance in mechanical fault prediction and diagnosis.

Although RNNs and LSTMs have succeeded in sequence modeling, their inherently sequential computation limits training speed and parallelism. Transformers, leveraging global self-attention mechanisms and efficient parallel computation, have emerged as promising tools for time-series analysis and have been rapidly applied in mechanical fault diagnosis. Jin et al. [22] proposed a time-series Transformer (TST)-based method for rotating machinery fault diagnosis, introducing a sequence tokenizer to segment one-dimensional vibration signals into subsequences, transforming them into high-dimensional representations suitable for Transformer-based feature learning. The multi-head self-attention mechanism enhances the model’s ability to capture global patterns, improving classification accuracy. Li et al. [23] introduced a variational attention-based Transformer network (VATN), incorporating variational inference into the standard Transformer encoder and optimizing attention weights via Dirichlet distributions, thereby enhancing the interpretability of causal relationships between signal patterns and fault types. Wu et al. [24] proposed a Transformer-based classification model for manufacturing rotational systems, capable of identifying known fault types and detecting novel faults, thus improving system adaptability. Furthermore, Pei et al. [25] proposed a hybrid Transformer-CNN (TCN) model, where Transformers capture long-range dependencies and CNNs extract local features, with transfer learning employed to enhance generalization. Experimental results showed that TCN outperforms traditional LSTM and CNN models in classification accuracy across multiple vibration datasets, while also achieving higher computational efficiency.

Few-shot learning approaches for bearing fault classification have shown significant promise in addressing the challenge of data scarcity. For instance, Han et al. [26] introduced domain-adversarial networks into a meta-learning framework, enabling effective feature transfer from source to target domains by generating meta-knowledge. Chen et al. [27] adopted a model-agnostic meta-learning strategy to enhance generalization across varying operating conditions, refining parameters through gradient-based adaptation on novel tasks.

In addition to these works, some recent methods have attempted to integrate domain adaptation and meta-learning strategies for fault diagnosis, such as ADMTL and PMML.

ADMTL [9] introduces an attention-based meta-transfer learning framework, aiming to reuse knowledge from previously learned fault categories for quick adaptation to new ones under domain shifts. PMML [10], on the other hand, adopts a prototype-based meta-learning approach, which learns task-invariant knowledge from source domains and performs feature matching in target domains. While both methods provide valuable insights into few-shot domain adaptation, they primarily focus on global feature alignment and do not explicitly consider subdomain-level discrepancies that may exist within the same domain due to varying operational conditions. In contrast, our proposed DBDA-FD introduces a subdomain discriminator to capture fine-grained domain differences and a dynamic balancing factor to adaptively weight global and subdomain alignment objectives. This dual-level alignment framework promotes symmetric structure not only globally but also within subdomains, enhancing the model’s ability to generalize under varying operational conditions.

Recently, Yang et al. [28] proposed an enhanced diagnosis framework that combines Relief-F-based feature selection with an optimized random forest algorithm. By identifying the most discriminative features from vibration signals using Relief-F, the model reduces computational complexity without sacrificing performance. The optimized random forest further addresses class imbalance by dynamically adjusting tree-splitting criteria and sample weighting, leading to improved robustness in imbalanced datasets. In parallel, Zhang et al. [29] developed a hybrid dilated convolutional network (HDCN) that leverages multi-scale dilated convolutions to capture both local and global features. A novel class-aware attention (CAA) mechanism is introduced to adaptively reweight feature maps based on class rarity, ensuring adequate representation of minority fault types. Experiments demonstrate that HDCN outperforms conventional CNN and LSTM models in imbalanced scenarios, particularly in identifying rare and underrepresented fault conditions. Building on these advances, recent studies have also explored more scalable and generalizable paradigms in mechanical fault diagnosis. For instance, Mehta et al. [30] proposed a federated transfer learning framework to achieve cross-factory fault generalization without sharing raw data, while Vijayalakshmi et al. [31] designed a decentralized federated learning scheme to preserve data privacy and mitigate distribution discrepancies. In the context of long-range dependency modeling, Tang et al. [32] introduced Signal-Transformer, which captures spectral-temporal patterns under variable conditions using attention mechanisms. Moreover, Wang et al. [33] developed a Transformer-based few-shot learning model tailored for noisy labels and limited samples, achieving high accuracy under changing working conditions. These studies highlight the growing demand for fault diagnosis frameworks that support privacy, domain robustness, and data efficiency—further motivating our dynamic dual-alignment strategy within the DBDA-FD framework.

In summary, these recent methods—spanning CNNs, RNNs, Transformers, and few-shot learning frameworks—demonstrate a clear trend toward improving diagnostic performance under practical constraints such as limited or imbalanced data. However, achieving robust domain adaptation remains a persistent challenge.

3. Problem Definition

To address the challenges of few-shot fault diagnosis in rotating machinery, this study categorizes datasets into three types: domain-specific training data , domain-adaptive validation data , and test data . We define a dataset as , where all three subsets are disjointed and the dataset contains B classes of data, each class consisting of instances, with C labeled instances and E unlabeled instances. In this work, a “task” is defined as a specific scenario, denoted as , where represents the support set containing labeled samples, represents the label corresponding to the fault situation, and denotes the query set with labeled samples. indicates ground-truth labels used only for testing or validation purposes. The term refers to the predicted labels for query examples from a source domain task, which excludes any samples in the corresponding support or query sets. Our proposed method treats the query set of a target domain as the ground truth, leverages the remaining samples as the source domain, and finally evaluates model performance by averaging the prediction results across all target scenarios.

4. Methodology

This section aims to develop the DBDA-FD model framework based on a few-shot learning architecture, addressing the issues outlined earlier. The proposed model primarily focuses on feature transfer at the global domain level while neglecting subdomain alignment and overfitting in domain feature adaptation. To overcome this limitation, specific bearing datasets are utilized as input, with both source and target domains fed into a global domain discriminator and a subdomain discriminator. The discriminators are designed to differentiate whether input data belong to the source or target domain. Through adversarial training between the generator and the discriminators, the model is progressively optimized to learn highly transferable features. This section provides a comprehensive description of the overall model architecture and details the design and structure of each component module.

4.1. Overview

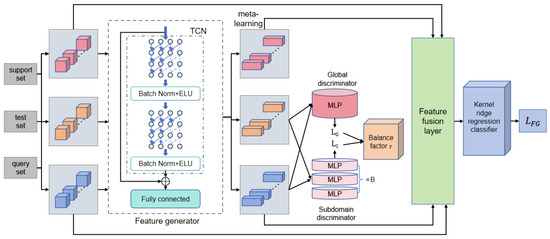

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed DBDA-FD model, which consists of four main components. Each component is detailed as follows. The model takes three types of inputs—support set, test set, and query set—which are first passed into the feature generation module. This module employs a temporal convolutional network (TCN) to extract sequential features. These features are then enhanced through batch normalization and ReLU activation, followed by a fully connected layer that projects them into a unified feature space. The resulting representations for both the source and target domains are discussed in Section 4.2. Next, the initial features are fed into the domain discrimination and alignment module, which consists of two parallel components: a global discriminator and multiple subdomain discriminators. The global discriminator, based on a multilayer perceptron (MLP), evaluates inter-domain discrepancies at the overall distribution level, while the subdomain discriminators—also implemented as parallel MLPs—focus on aligning local feature subspaces to mitigate overfitting during domain adaptation (see Section 4.3). After processing, the inter-domain gap is significantly reduced, resulting in preliminary aligned features. To balance the influence of global and local alignment, these intermediate features are passed into the dynamic balance factor module. This module adaptively learns weighting coefficients based on alignment errors from the global and subdomain components, dynamically adjusting the optimization direction to prevent overemphasis on any single alignment level. The output is a fused representation that jointly reflects global consistency and local adaptability (see Section 4.4). Finally, the fused features are fed into the classification module. After multi-source information integration through a feature fusion layer, the kernel ridge regression classifier produces the final diagnostic result, completing the mapping from raw input to fault category label. The entire data flow is illustrated in Figure 1, where each module is sequentially connected to reflect the end-to-end diagnostic process.

Figure 1.

DBDA-FD overall.

4.2. Feature Generator

In the process of generating high-quality meta-features, the feature generator effectively captures the relationship between the source and target domains while enhancing the expression of source domain information through transfer learning. These meta-features are then passed to the feature fusion layer, which focuses on improving the embedding representation of bearing fault feature vectors, further promoting effective feature transfer and integration. The generator not only enhances the model’s performance in fault diagnosis tasks but also maximizes the indistinguishability between domains, making it difficult for the discriminator to distinguish between data samples from the source and target domains. The core structure of this module includes the temporal convolutional network (TCN) and fully connected layers (i.e., feedforward neural networks), which together enable efficient feature learning and transfer. First, causal and dilated convolutions are used to capture information in sequence data, effectively modeling the relationships between features within the sequence and improving the quality of the sequence vector representation. The sequence feature representation, denoted as , is input into the TCN network, with task as a sample. It is first processed through the causal convolution layer, which ensures that the output at the current time step depends on both the current and previous time steps, as described by the computation process in Equation (1):

Here, denotes the hidden state at time step t and layer l for a support sample, represents the convolutional kernel weight of layer l, k is the kernel size, and is the input from the previous layer. Traditional convolution operations are limited by small receptive fields, making it difficult to capture long-term dependencies. To address this, we incorporate dilated convolutions, which expand the receptive field and introduce a dilation rate d. This parameter typically increases exponentially with the layer index, allowing the network to attain a larger receptive field with fewer layers. The detailed computation is shown in Equation (2).

where denotes the feature representation at time step in the l-th layer of the causal dilated convolution module. The variable d represents the dilation rate, which controls the spacing of the kernel sampling. To ensure stable gradient propagation, the network adopts a residual connection mechanism, originally proposed by He et al. [34]. The detailed computation is shown in Equations (3) and (4).

Here, is a nonlinear activation function, denotes the convolutional weight parameters, and * represents 1D convolution. This structure ensures temporal consistency for residual operations. The term is the bias parameter. To enhance training stability, a dropout operation is applied after normalization, yielding the output . The symbols and represent the query and source domains, respectively, and follow the same computational procedure as above. Finally, a fully connected layer followed by a softmax function is used in the final layer to obtain the element-wise feature representations , as defined in Equation (5).

where and represent the weight matrix and bias of the fully connected layer, and is a T-dimensional vector containing the high-quality meta-features generated by the generator.

4.3. Domain Discriminator

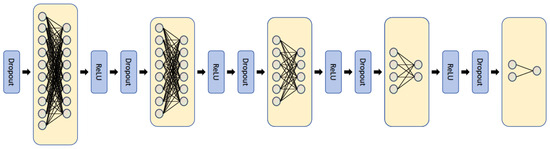

Previous studies primarily focused on global alignment, neglecting fine-grained issues such as the problem of new bearing fault classes. This often leads to confusion between source and target domain data, and the loss of fine-grained information for each class [35]. When fitting global domain feature alignment, overfitting is a common issue. To address this, we introduce cross-domain feature alignment, specifically by incorporating multiple sub-domain discriminators. These discriminators are designed to identify whether each class sample belongs to the source or target domain. This approach not only mitigates overfitting during alignment but also enables the model to learn high-quality transferable features. This mechanism allows the model to better adapt to the target domain’s feature distribution during the adversarial competition between the feature generator and the discriminator, encouraging the feature generator to produce more generalizable and transferable features. The proposed domain discriminator consists of multiple sub-domain discriminators and a global domain discriminator. Both the global and sub-domain discriminators are implemented using a four-layer feedforward neural network. Experimental results show that the model achieves a balanced performance with this four-layer structure. The specific architecture is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Domain discriminator.

The sub-domain discriminators play a crucial role in feature alignment, as they ensure the fine-grained alignment of features for each class, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to discriminate features. To challenge and confuse the enhanced domain discriminators, the feature generator must narrow the feature distribution for each class individually. This narrowing is crucial for the effective cross-domain feature transfer, enabling better feature alignment. In the output layer, a softmax function is used to calculate the probability distributions for the target and source domains, denoted as , where 0 represents the target domain and 1 represents the source domain. The specific calculation process is given by Equation (6).

4.4. Feature Fusion and Fault Diagnosis Classification

We hypothesize that the meta-features generated through the adversarial interaction between the feature extractor and domain discriminator are transferable, meaning the feature generator produces features similar to those of the target domain. In the feature fusion layer, the meta-features generated by the feature generator are combined with the sample features to produce higher-quality feature vectors. Since the source domain data does not require classification, no fusion computation is necessary for it. Therefore, fusion is only applied to the support set and query set, with the final fusion process for the feature vectors calculated as shown in Equations (7) and (8).

Here, represents the final representation of the support set samples, and represents the final representation of the query set samples. To accelerate convergence and improve model performance, we incorporate the residual connection concept from the self-attention mechanism to optimize the computation process, ensuring efficient and stable information transmission and feature learning.

For the bearing fault diagnosis classification task, we use ridge regression as the classifier. Ridge regression adds an L2 regularization term to mitigate overfitting, enabling the classifier to train from scratch on the support set. There are three main reasons for selecting ridge regression: first, ridge regression [36] provides an end-to-end differentiable closed-form solution through the model, using the least squares method to solve for parameter weights. Second, ridge regression has low computational complexity and fast training speed, which is particularly advantageous when the support set sample size is small, as other neural network classifiers may not have enough data to train effectively. Third, ridge regression’s L2 regularization term restricts the size of the weights, making the model smoother and alleviating overfitting. The parameter weight matrix calculation process for the ridge regression classifier is shown in Equation (9): this matrix is primarily used for fault diagnosis classification.

Here, E denotes the identity matrix, represents a one-hot label vector in the support set, and is a regularization coefficient used to control overfitting. The final prediction is computed as

where and are learnable scaling and bias parameters, respectively. These, along with , are updated during meta-training and are fine-tuned minimally during testing.

During training, classifier parameters are updated using the support set, while the feature generator and domain discriminator remain fixed. The classification loss is defined as in Equation (11).

Here, denotes the Frobenius norm. During training, the domain discriminator is updated using both source and target domains, while the classifier and feature generator parameters remain fixed. For both the global domain discriminator loss and the subdomain discriminator loss , cross-entropy loss is used. The computations are as follows:

where and represent the prediction logits from the global and q-th subdomain discriminators, respectively. y is a binary label indicating whether a sample belongs to the target or source domain. During this process, the domain feature generator is updated using the corresponding data from both domains. The final adversarial loss is defined in Equation (14).

Here, denotes the label sequence of the query set. Due to the data imbalance and uneven class distribution between the source and target domains, domain adaptation models may suffer from domain and feature alignment biases, which degrade performance on the target domain. To address this, a dynamic learning balance factor is introduced. This factor adjusts the trade-off between global and subdomain alignment, encouraging the model to learn more domain-invariant features. is a hyperparameter. The calculation of is as follows:

where denotes the loss from the q-th subdomain discriminator. Initially, is set to 0.5. When is high, indicating that the feature generator fails to deceive the global domain discriminator, the model is biased more toward subdomain alignment. This adaptive mechanism adjusts the model’s focus to achieve better domain adaptation. The update of is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: The specific update process of the balance factor |

|

5. Experiments and Results Analysis

This section first introduces the experimental setup, including the datasets used, baseline methods for comparison, and specific experimental details. It then presents a series of experiments conducted on two publicly available datasets, followed by an analysis and discussion of the results. Additionally, ablation studies on the model’s components are conducted to validate the importance of each module.

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Datasets

Rolling bearings are a critical component of motor operations and are commonly found in integrated motor equipment. Bearing failures, often caused by prolonged rotation wear and high temperatures generated during rotation, are a frequent issue. Early detection of bearing failures improves production efficiency, product quality, and prevents safety accidents, making it of significant practical importance. This study focuses on fault detection of motor rolling bearings under unknown working conditions with a limited number of samples. To evaluate the performance and effectiveness of the proposed method, a series of experimental analyses were conducted using two mainstream fault detection datasets: the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset [37] and the Paderborn University bearing dataset [38].

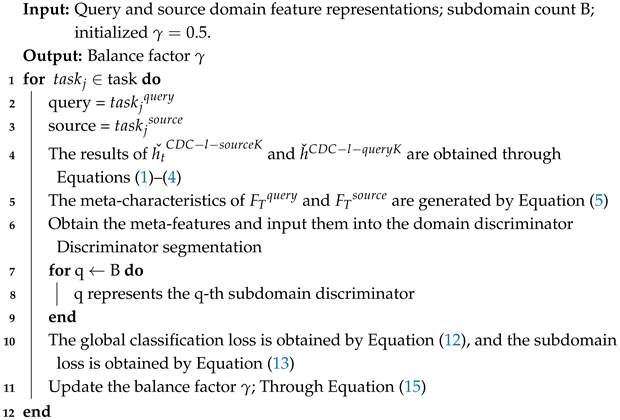

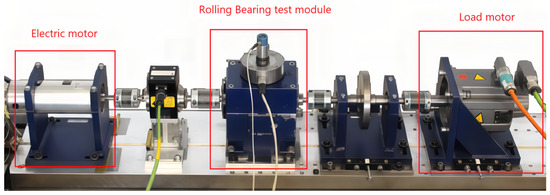

CWRU Bearing Dataset: Vibration signals from the motor drive end were collected at a 12 kHz sampling frequency under various health conditions of the bearings. The experimental setup, as shown in Figure 3, consists of three main components: a 1.5 kW (2 horsepower) Reliance motor, a torque sensor, and a power meter. Vibration signals were captured by installing various faulty bearings on the test rig. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the selected CWRU bearing dataset, which includes four health conditions of the bearing, including one normal and three fault states. The fault diameters of the bearings are 0.007 inches, 0.014 inches, and 0.021 inches, resulting in 10 different health conditions for each load. Additionally, the dataset considers different loads, which are related to motor speed, as shown in Table 2. In this study, vibration signals under different conditions and health statuses were divided into 200 sub-samples using a sub-sampling window, as described in Table 3. With the assumption that vibration signals from different bearings under different operating conditions represent distinct types, the dataset contains 40 different types of vibration signals and 8000 labeled samples. Since the focus of this study is fault detection of motor rolling bearings with limited samples under unknown conditions, the dataset is split into meta-training, meta-validation, and meta-testing categories, with 20, 10, and 10 conditions, respectively. Data from conditions C0 and C1 were used for model training, C2 for model validation, and C3 for model testing. The details of the data split are provided in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the test stand.

Table 1.

Details of the CWRU Bearing dataset under various load and health states.

Table 2.

Relationship between motor load and rotation speed.

Table 3.

Details of each working condition under the CWRU dataset.

Table 4.

Details of data division under CWRU dataset.

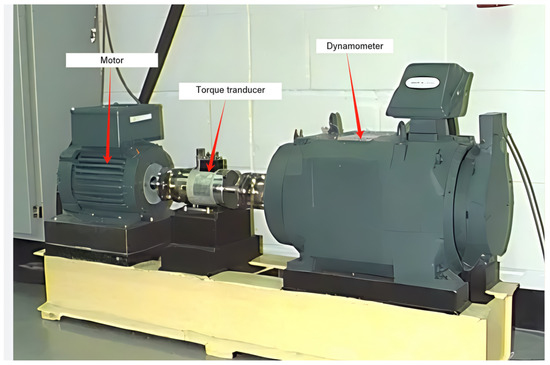

Paderborn University (PU) Bearing Dataset: Vibration signals were collected from both damaged and undamaged bearings under different loads. The damaged bearings include two types: artificially damaged and naturally damaged. Artificial damage can be induced by discharge machining, reaming, and electro-etching, while natural damage is obtained through accelerated life testing. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 4, consisting of a driving motor (Hanning synchronous motor: 425 W, 3000 r/min), rolling bearings, and a load motor (Siemens synchronous servo motor: 1.7 KW, 3000 r/min). The test rig is also equipped with a torque measurement device and a flywheel, collecting vibration signals from bearings under 32 different health states across four operating conditions (26 damaged bearing types and 6 healthy bearing types). Based on the location of the bearing faults, the bearings are categorized into three types: undamaged (UD), inner race fault (IR), and outer race fault (OR). The goal is to diagnose three different bearing health statuses under unknown operating conditions. Specifically, vibration signals from bearings with different health statuses under various conditions are divided into 400 sub-samples using a sub-sampling window, with each sample containing 2500 sampling points. A detailed description of the dataset under each condition is provided in Table 5. The dataset includes 12 types of vibration signals and 4800 labeled samples. Data from two conditions are used for model training, data from one condition for model validation, and data from the remaining conditions for model testing. Since data from different conditions are used for training, validation, and testing, 12 possible combinations are generated. Four of these combinations are selected to construct the dataset for model training, validation, and testing to evaluate the model’s effectiveness. The data partition details are shown in Table 6.

Figure 4.

Illustration of test stand under Paderborn University Rolling Bearing dataset.

Table 5.

Details of each working condition under the PU dataset.

Table 6.

Details of data division under the PU dataset.

In this study, the commonly used public datasets CWRU and PU are adopted to evaluate the performance of the proposed model. The CWRU dataset consists of bearing fault samples collected under various rotational speeds and loads, while the PU dataset contains fault samples obtained under different operating parameter settings. The number of working conditions and the data partitioning used in the experiments are summarized in Table 7. Specifically, for the CWRU dataset, the fault categories are divided into 20, 10, and 10 classes for meta-training, meta-validation, and meta-testing, respectively. For the PU dataset, the categories are split into six, three, and three classes for the same purposes.

Table 7.

Basic statistics for CWRU and PU datasets.

5.1.2. Baseline Methods

We selected the following six competitive methods as comparison models for the proposed DBDA-FD and conducted extensive experiments on two public bearing fault datasets to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach

- WDCNN-few-shot [39] is a few-shot bearing fault diagnosis model based on WDCNN, which enables effective bearing fault diagnosis with limited data. It captures periodic or global features from raw input signals using large convolutional kernels in the first layer of the network, effectively extracting low-frequency components to accurately identify vibration signals from bearings under different health states.

- IPN [40] builds upon the prototype network (PN) and introduces a class attention strategy and distance scaling strategy. The class attention strategy assigns different weights to samples based on their representativeness to mine intra-class information, while the distance scaling strategy extracts inter-class discriminative information. The combination of both strategies reduces intra-class differences and increases inter-class differences, facilitating effective differentiation between faults of different bearing categories.

- MAML [41] is a model-agnostic meta-learning algorithm that adapts to new tasks with only a few gradient updates.

- GMAML [42] employs multi-core efficient channel attention to extract general diagnostic knowledge from multiple meta-tasks for fault diagnosis under limited data conditions.

- ADMTL [9] utilizes an attention mechanism to drive the model in extracting meta-knowledge, leveraging transfer learning to acquire prior knowledge from existing fault samples, enabling rapid adaptation to fine-grained faults under new conditions.

- PMML [10] is a prototype matching-based meta-learning method for fault diagnosis with limited samples under data-constrained conditions. It learns prior meta-knowledge from multiple fault classification tasks under known operating conditions in the source domain and then uses a trained feature extractor to derive meta-features from limited samples in the target domain for metric learning.

5.1.3. Experimental Setup

We evaluate the model’s performance based on its accuracy on the test set. To ensure a fair comparison with the baseline methods, we set up 400, 200, and 1000 randomly selected task sets for the training, validation, and testing phases, respectively. Additionally, we implement an early stopping strategy if the model’s performance does not improve over 40 epochs. All model parameters are optimized using the Adam optimizer, with a learning rate of 1 × . The detailed parameter settings are shown in Table 8. Finally, all experiments are conducted on the same server, with the hardware environment consisting of an AMD EPYC 7543 32-Core Processor and an NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPU. The software environment includes PyTorch 1.13.1 and Python 3.7.

Table 8.

Experimental parameter settings.

5.2. Experiments Results and Analysis

5.2.1. Baseline Experiment Results Analysis

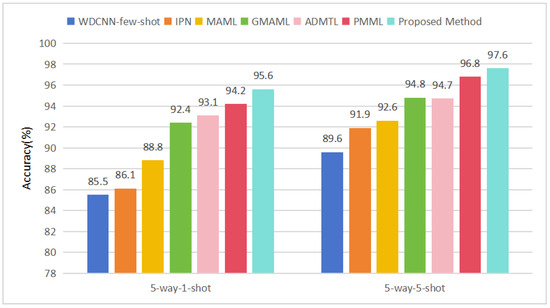

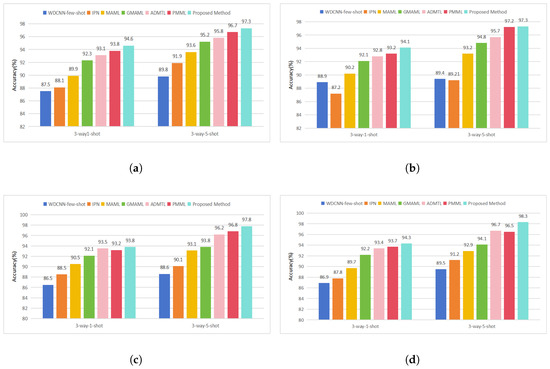

To evaluate the performance of the proposed DBDA-FD model for few-shot fault diagnosis under unseen working conditions, we conducted experiments on the CWRU dataset using five-way one-shot and five-way five-shot task settings and on the PU dataset using three-way one-shot and three-way five-shot settings. The DBDA-FD model was trained on the training set for meta-knowledge learning and transfer, with classification accuracy on the test set serving as the evaluation metric. Each experiment was repeated 10 times, and the average results are reported in Table 9 and Table 10. Comparative performance trends are further illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Table 9.

Few-shot fault diagnosis experiment result on CWRU dataset.

Table 10.

Few-shot fault diagnosis experiment results on the PU dataset.

Figure 5.

Results compared with six baselines on CWRU dataset.

Figure 6.

Results compared with six baselines on Paderborn University Rolling Bearing dataset under different data division: (a) combination 0, (b) combination 1, (c) combination 2, and (d) combination 3.

The DBDA-FD model enhances generalization in target domains through adversarial domain adaptation, consistently outperforming conventional classifiers such as WDCNN-few-shot and IPN. Additionally, DBDA-FD employs a dynamic balancing factor to adaptively align features at both global and sub-domain levels, enabling richer and more discriminative transferable feature learning. In the five-way one-shot and five-way five-shot tasks, DBDA-FD achieved accuracies of 95.6% and 97.6%, surpassing the best baseline methods by 1.4% and 0.8%, respectively. Similarly, in the three-way one-shot and three-way five-shot tasks across four different working condition combinations, DBDA-FD consistently delivered superior performance. For instance, under Combination 0, it attained 94.6% and 97.3% accuracy, outperforming the strongest baselines by 0.8% and 0.6%, respectively. These results confirm DBDA-FD’s efficacy in few-shot fault diagnosis under unknown conditions. Performance improvement of DBDA-FD on the CWRU dataset is more pronounced than on the PU dataset, indicating its unique advantage in capturing fine-grained subdomain features while maintaining a balanced representation of global features. This aligns well with the CWRU dataset, which contains a wider variety of fault types, and highlights the potential applicability of DBDA-FD in complex diagnostic scenarios that closely resemble real-world industrial conditions.

Unlike ADTML and PMML, which focus solely on global domain alignment, DBDA-FD explicitly addresses fine-grained sub-domain feature discrepancies through a sub-domain discriminator. While model-agnostic meta-learning methods (e.g., MAML and GMAML) prioritize rapid task adaptation, they often overlook domain shift-induced overfitting risks. In contrast, DBDA-FD’s sub-domain alignment strategy enhances discriminative feature transfer, particularly in fine-grained datasets like CWRU. Moreover, even in the coarse-grained PU bearing dataset, DBDA-FD surpasses baselines by dynamically balancing global and sub-domain feature alignment, thereby improving classification accuracy under unseen conditions.

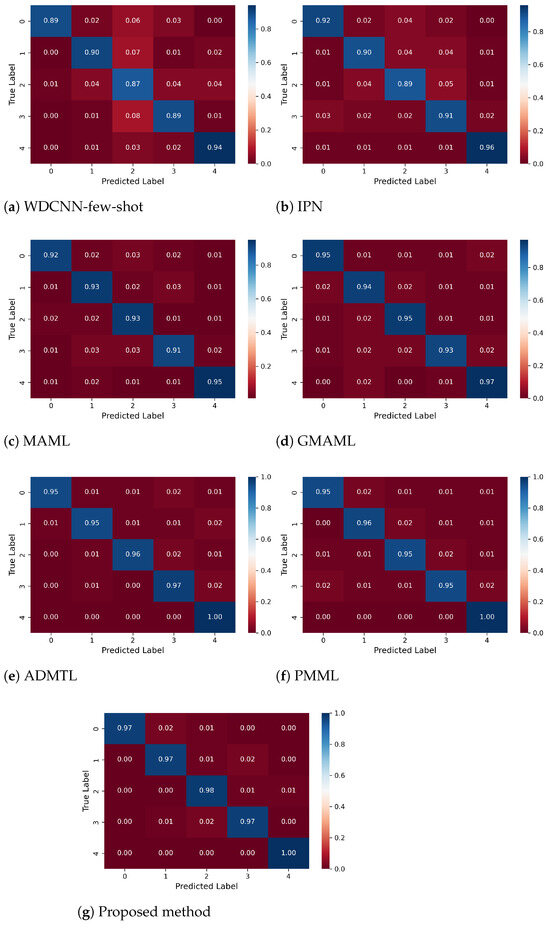

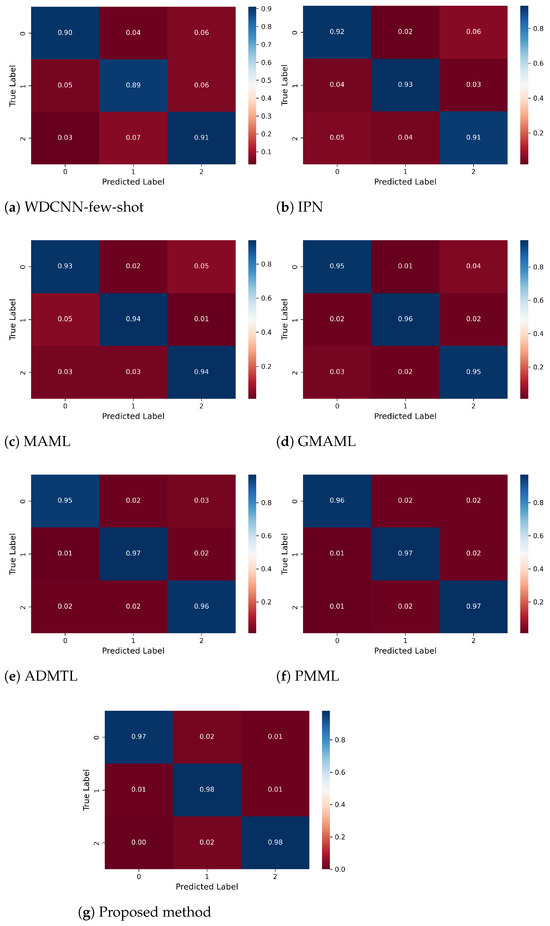

To further validate the improvements of the proposed DBDA-FD over baseline methods, we present the confusion matrices of all models under the five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot settings, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. It is evident that DBDA-FD achieves higher classification accuracy for each fault category, with a maximum inter-class accuracy gap of only 3%, which is lower than those of the baseline methods (PMML: 5%, GMAML: 4%). This indicates a more balanced fault recognition capability. The improvement is attributed to the synergistic optimization of the parallel dynamic dual-granularity feature alignment mechanism and the adaptive weight adjustment strategy. DBDA-FD constructs a multi-granularity representation space through parallel global and subdomain feature branches, adaptively adjusts feature fusion weights during training via a dynamic balancing factor, and jointly optimizes domain invariance and class discriminability through adversarial training with dual discriminators. These designs collectively contribute to improved accuracy and balanced fault identification. On the PU dataset, DBDA-FD further demonstrates its robustness under unknown operating conditions.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of the 5-way 5-shot fault diagnosis on CWRU dataset.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix of the 3-way 5-shot fault diagnosis on PU dataset.

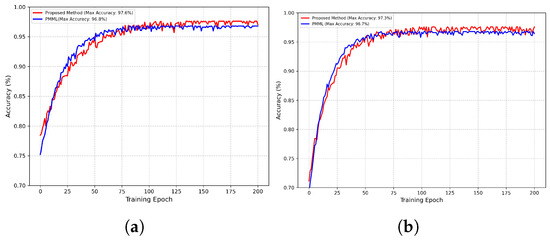

We plotted the classification accuracy curves of DBDA-FD and the second-best method, PMML, during training, as shown in Figure 9. Notably, under both five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot tasks, DBDA-FD converges more slowly than PMML yet achieves higher classification accuracy upon convergence. For instance, in the five-way five-shot setting, DBDA-FD reaches 97.6% accuracy at epoch 132, surpassing PMML’s 96.8% at epoch 108 by 0.8%. This is because PMML employs a single feature extractor and a fixed-weight meta-learning framework, resulting in a straightforward parameter update path without the need for multi-branch feature alignment, thus enabling faster convergence. However, this simplicity limits its capacity to capture complex fault features, making it difficult to surpass existing performance ceilings. In contrast, DBDA-FD adopts a dual-branch feature extraction architecture (global and subdomain) that dynamically adjusts feature fusion weights through a balancing factor . It also jointly optimizes adversarial losses from both global and subdomain discriminators (Equations (12)–(14)), leading to a more complex parameter coordination process and a longer convergence period. Nevertheless, this multi-constraint optimization forces the model to learn more robust cross-class feature representations, ultimately resulting in higher classification accuracy, particularly in scenarios with subtle differences between fault categories.

Figure 9.

Accuracy of the proposed method and PMML during the model training in different few shot scenarios. (a) Five-way five-shot on CWRU dataset. (b) Three-way five-shot on PU dataset.

5.2.2. Impact of K and N on Model Performance

In this section, we investigate the impact of different K (number of classes per meta-task) and N (number of samples per class) on model performance in few-shot learning. Given that the CWRU dataset contains more fine-grained categories, we examine various combinations of K and N, while for the coarse-grained PU dataset, we focus on K = 3 with varying N.

Table 11 presents the impact of increasing the number of classes K on model performance while keeping the number of samples N constant. As K increases, classification accuracy consistently declines. This is because a larger number of classes increases task complexity, requiring the model to learn more discriminative features from limited data. Therefore, under a fixed sample size N, model performance tends to degrade as K grows. To further investigate, we analyzed the effect of increasing the number of samples N while keeping K constant. As shown in Table 12, model performance improves steadily with more samples per class, indicating that greater data availability enhances the model’s ability to distinguish between categories.

Table 11.

The influence of the number K of different categories on the model performance.

Table 12.

Impact of different sample sizes (N) on model performance for few-shot fault diagnosis.

5.3. Ablation Study

We conduct ablation studies to validate the effectiveness of key components in the proposed DBDA-FD model, specifically examining the dynamic balancing factor, domain adversarial module, and feature aggregation layer.

Experiments are performed on both CWRU (five-way five-shot) and PU (three-way one-shot) datasets, with results summarized in Table 13. First, replacing the dynamic balancing factor with a fixed averaging operation leads to accuracy drops of 1.0% (CWRU) and 1.2% (PU), demonstrating its critical role in surpassing baseline performance. Second, removing the domain adversarial module causes significant degradation, reducing accuracy by 5.5% (CWRU) and 7.1% (PU), which confirms its essential contribution to cross-domain adaptation. Finally, eliminating the feature aggregation layer results in declines of 2.3% (CWRU) and 1.4% (PU), verifying its effectiveness in enhancing discriminative feature learning. These results collectively validate the necessity of each module in optimizing DBDA-FD’s diagnostic performance.

Table 13.

Ablation experiment results on CWRU and PU datasets.

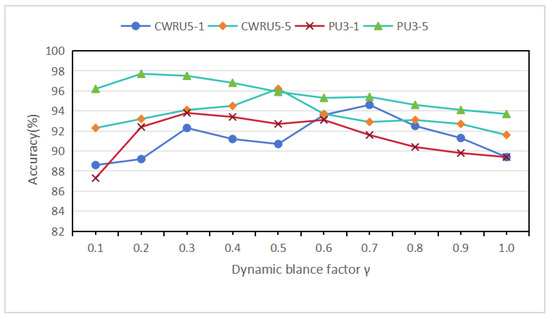

5.4. Impact of Parameter on Model Performance

This section evaluates the impact of the dynamic balance factor on model performance, validating both the necessity of global and sub-domain alignment and the effectiveness of .

Dynamic balance factor is a dimensionless number. Figure 10 illustrates the variation in classification accuracy on the validation set with respect to changes in the dynamic balance factor on the CWRU and PU datasets. Evidently, the classification performance of the model fluctuates significantly as the dynamic balance factor varies, indicating that the balance between global and subdomain feature alignment is not trivial but rather a critical regulatory mechanism. Properly tuning this balance is essential for optimizing the model. Moreover, the optimal dynamic balance factor differs across few-shot tasks. For instance, the optimal values for the five-way one-shot and five-way five-shot tasks on the CWRU dataset are 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, while for the three-way one-shot and three-way five-shot tasks on the PU dataset, they are 0.3 and 0.2. These variations can be attributed to the inherent characteristics of the datasets (e.g., noise levels and fault type diversity) and task complexity, as one-shot tasks impose stricter requirements on feature generalization. For example, in the data-scarce five-way one-shot setting, the model tends to rely more on global domain alignment, resulting in a higher on CWRU. Additionally, we compare model performance under different computation strategies, including two baselines: (1) a fixed average value and (2) step-wise increments from the set {0.1, 0.2, …, 1}. As summarized in Table 14, the first two methods (global and subdomain) only consider global or subdomain alignment independently. The proposed dynamic balance strategy outperforms both, demonstrating that jointly aligning global and subdomain features yields superior results. For example, in the PU dataset under the three-way five-shot task, our method achieves 2.4% and 2.1% higher accuracy than the global and subdomain baselines, respectively. These findings highlight the importance of synergistic global–subdomain alignment in few-shot fault diagnosis and confirm that the proposed dynamic factor effectively maximizes this synergy by adaptively adjusting alignment weights.

Figure 10.

Verification of the accuracy rate of the model under different values of the dynamic balance factor on the verification set.

Table 14.

Performance of different domain adaptation methods on CWRU and PU datasets.

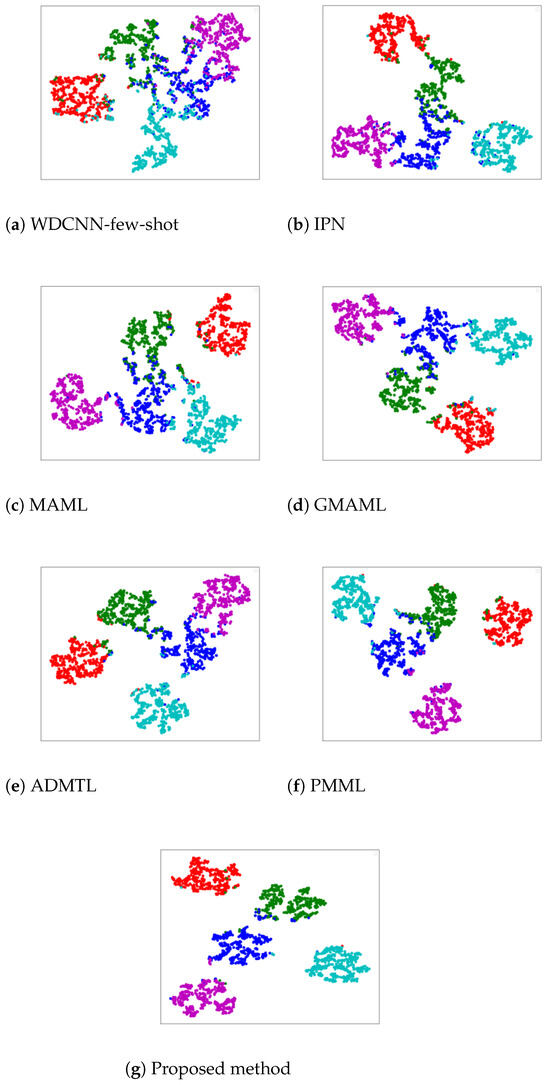

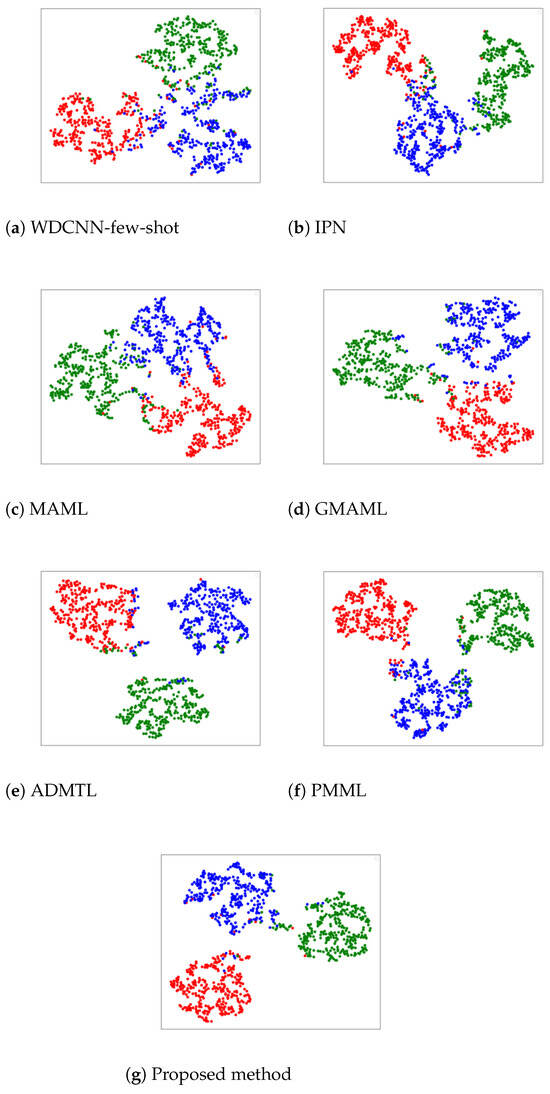

5.5. Visualization Analysis

We conducted a visualization analysis of the output features from the feature aggregation layer of the proposed model DBDA-FD, on the CWRU and PU datasets. Specifically, we set up five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot tasks for both datasets. First, we trained the model on the training set, then tested the trained model on the test samples to obtain their high-dimensional vector representations. Finally, we used t-SNE to reduce these high-dimensional vectors to two dimensions and visualized them.

Figure 11 shows the feature space visualization results of various methods on the CWRU dataset. The DBDA-FD model generally achieves the best separation among the five classes, with the cyan class almost entirely grouped together, maintaining a significant distance between classes and high separability. In contrast, WDCNN-few-shot exhibits some confusion between the green, blue, cyan, and magenta classes, with some blue points assigned to green and cyan to magenta, indicating that WDCNN-few-shot does not effectively distinguish these four categories. Similarly, IPN and MAML show some confusion between blue and green, with some blue points classified as green. Therefore, both IPN and MAML do not perform well in classification. In GMAML, ADMTL, and PMML, the overall clustering is better, but there is still slight overlap in some colors, suggesting room for improvement. Figure 12 displays the feature space visualization results on the PU dataset. It is evident that WDCNN-few-shot, IPN, MAML, and GMAML effectively separate red, blue, and green, but confusion still occurs at the edges, particularly between green and blue, where some blue points are classified as green. In ADMTL and PMML, the separation between blue, green, and red is generally good, with noticeable gaps between different colors, indicating superior classification performance. However, some points of other colors still appear at the cluster edges. In contrast, the proposed model demonstrates almost perfect consistency in color regions within each cluster, with excellent separation between clusters, indicating superior classification capability.

Figure 11.

Feature visualization results on the CWRU dataset.

Figure 12.

Feature visualization results on the PU dataset.

To facilitate a more intuitive comparison of visualization differences between the two datasets, the key results are summarized in Table 15. As evidenced by the analysis and tabulated comparisons, the proposed DBDA-FD demonstrates the most effective feature separation on both the CWRU and PU datasets, while other models exhibit varying degrees of feature confusion. Moreover, the performance gradients across the two datasets reveal both similarities and distinctions among the models.

Table 15.

The comparison between CWRU and PU datasets for feature visualization.

5.6. Model Complexity and Inference Time Analysis

Finally, we evaluated the model complexity and inference time of DBDA-FD under the five-way five-shot setting to assess its feasibility for deployment in real-world industrial scenarios, as summarized in Table 16. In terms of memory consumption, PMML demonstrates the most lightweight design with 6850 ± 80 KB, while MAML exhibits the highest usage (12,800 ± 180 KB) due to the complexity of its meta-parameter update mechanism. DBDA-FD occupies 7920 ± 105 KB, representing a moderate level—lower than more complex models such as MAML and GMAML and slightly higher than IPN and PMML. For inference time per sample, PMML (0.035 ± 0.002 s) and IPN (0.038 ± 0.002 s) achieve the fastest response due to their streamlined architectures. In contrast, MAML requires the longest inference time (0.125 ± 0.008 s) because of its repeated gradient updates. The proposed DBDA-FD achieves an inference time of 0.045 ± 0.003 s, which, while marginally slower than PMML, is significantly faster than MAML and GMAML. This demonstrates that DBDA-FD maintains a favorable balance between classification performance and real-time responsiveness, making it suitable for practical industrial deployment.

Table 16.

Inference time and model complexity for five-way five-shot fault diagnosis on the CWRU dataset.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

When trained with limited samples, deep learning models often suffer from overfitting and poor generalization, especially in fault diagnosis tasks under domain shift. To address these challenges, we proposed a novel few-shot fault diagnosis framework, DBDA-FD, which integrates global and subdomain feature alignment within a meta-learning paradigm. A dynamic balancing factor is introduced to adaptively regulate the contribution of global and subdomain alignment objectives, enabling the model to generate more transferable features across varying working conditions. Comprehensive experiments conducted on the CWRU and PU bearing fault datasets confirm the superior performance of DBDA-FD. Specifically, the model achieved classification accuracies of 97.6% and 97.3% in five-way five-shot and three-way five-shot tasks, respectively, outperforming representative state-of-the-art methods such as PMML and ADMTL by up to 0.7%. These results demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of our approach in handling cross-domain scenarios with limited annotated data. In practical applications, DBDA-FD holds strong potential for real-world deployment in intelligent maintenance systems, where labeled fault data are scarce, and domain conditions are highly variable. However, its performance may degrade when the discrepancy between source and target domains is excessively large, limiting the effectiveness of feature transfer. To further improve the scalability and adaptability of the framework, future research will focus on developing quantitative transferability scoring metrics to evaluate domain similarity prior to adaptation. This will guide the dynamic selection or weighting of source domains, improving alignment efficiency and reducing negative transfer. Additionally, we plan to incorporate self-supervised pretraining techniques to alleviate the reliance on labeled source data—ensuring that the model learns reliable and high-quality transferable features, thereby enhancing its performance and stability in few-shot mechanical fault detection under unknown operating conditions and better meeting the needs of real-world applications.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—original draft, visualization. K.X.: data curation, supervision. X.C.: visualization, investigation, editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Association of the Third-Line Construction in Sichuan Province (SXJS202324).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available for download at the following web links: https://github.com/11124asda/DBDA-FD (accessed on: 28 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Choudhary, A.; Goyal, D.; Shimi, S.L.; Akula, A. Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis of Induction Motors: A Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2018, 26, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangsar, P.; Tiwari, R. Signal based condition monitoring techniques for fault detection and diagnosis of induction motors: A state-of-the-art review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 144, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Pan, H.; Cheng, J.; Cheng, J. A novel deep stacking least squares support vector machine for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Comput. Ind. 2019, 110, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, D.H.; Upadhyay, S.H.; Harsha, S.P. Fault diagnosis of rolling element bearing with intrinsic mode function of acoustic emission data using APF-KNN. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 4137–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiranyaz, S.; Avcı, O.; Abdeljaber, O.; Ince, T.; Gabbouj, M.; Inman, D.J. 1D Convolutional Neural Networks and Applications: A Survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.03554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Huang, X.; Cao, L.; Zhou, Q. Fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on recurrent neural networks. Measurement 2021, 171, 108774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Peng, D.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Goebel, K.F.; Wu, D. Planetary gearbox fault diagnosis using bidirectional-convolutional LSTM networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 162, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing System, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. Attention-based deep meta-transfer learning for few-shot fine-grained fault diagnosis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 264, 110345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, S.; Fu, S.; Liu, Y.; Suo, S.; Hu, G. Prototype matching-based meta-learning model for few-shot fault diagnosis of mechanical system. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 129012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agajie, T.F.; Ali, A.; Fopah-Lele, A.; Amoussou, I.; Khan, B.; Velasco, C.L.R.; Tanyi, E. A Comprehensive Review on Techno-Economic Analysis and Optimal Sizing of Hybrid Renewable Energy Sources with Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agajie, T.F.; Khan, B.; Guerrero, J.M.; Mahela, O.P. Reliability enhancement and voltage profile improvement of distribution network using optimal capacity allocation and placement of distributed energy resources. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, T.; Kiranyaz, S.; Eren, L.; Askar, M.; Gabbouj, M. Real-Time Motor Fault Detection by 1-D Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 7067–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hou, D.; Zhou, P.; Han, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yin, Q. Rotor fault diagnosis using a convolutional neural network with symmetrized dot pattern images. Measurement 2019, 138, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Madan, A. CNC machine-bearing fault detection based on convolutional neural network using vibration and acoustic signal. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Bin, G. Real-time intelligent diagnosis of co-frequency vibration faults in rotating machinery based on lightweight-convolutional neural networks. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Kim, B. 1D convolutional neural network-based adaptive algorithm structure with system fault diagnosis and signal feature extraction for noise and vibration enhancement in mechanical systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 197, 110395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Huang, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhong, M. Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Using Long-short-term Memory Recurrent Neural Network. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, R.; Rosato, D.; Hartmann, S.; Guehmann, C. LSTM Based Bearing Fault Diagnosis of Electrical Machines using Motor Current Signal. In Proceedings of the 2019 18th IEEE International Conference On Machine Learning And Applications (ICMLA), Boca Raton, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2019; pp. 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; He, X.; Tang, S.; Meng, F. An improved bearing fault diagnosis method using one-dimensional CNN and LSTM. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 64, 443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Khorram, A.; Khalooei, M.; Rezghi, M. End-to-end CNN+ LSTM deep learning approach for bearing fault diagnosis. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 736–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Hou, L.; Chen, Y. A Time Series Transformer based method for the rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2022, 494, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, C.; Chen, X.; Yan, R. Variational attention-based interpretable transformer network for rotary machine fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 6180–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Triebe, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. A transformer-based approach for novel fault detection and fault classification/diagnosis in manufacturing: A rotary system application. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 67, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zheng, X.; Wu, J. Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Through a Transformer Convolution Network Subjected to Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 2515611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Qiu, M.; Gao, M.; Zhou, A. Meta-learning adversarial domain adaptation network for few-shot text classification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.12262. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Hu, W.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Blaabjerg, F. A meta-learning method for electric machine bearing fault diagnosis under varying working conditions with limited data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 2552–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhai, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wen, J. An Improved Fault Diagnosis Method for Rolling Bearing Based on Relief-F and Optimized Random Forests Algorithm. Machines 2025, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hao, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yan, H.; Lv, Z.; Fan, Q.; Xu, C.; Xu, L.; Wen, Z.; et al. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on improved hybrid dilated convolution network for unbalanced samples. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Chen, S.; Tang, H.; Shao, C. A federated learning approach to mixed fault diagnosis in rotating machinery. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, K.; Amuthakkannan, R.; Ramachandran, K. Federated Learning-Based Futuristic Fault Diagnosis and Standardization in Rotating Machinery. Int. J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2024, 11, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zheng, G.; Wei, C.; Huang, W.; Ding, X. Signal-Transformer: A robust and interpretable method for rotating machinery intelligent fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3511911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Ding, P.; Li, S.; Tian, D.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Z. A novel transformer-based few-shot learning method for intelligent fault diagnosis with noisy labels under varying working conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 251, 110400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhuang, F.; Wang, J.; Ke, G.; Chen, J.; Bian, J.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. Deep subdomain adaptation network for image classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center. Bearing Data Center. 2017. Available online: https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter/download-data-file (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Lessmeier, C.; Kimotho, J.K.; Zimmer, D.; Sextro, W. Condition monitoring of bearing damage in electromechanical drive systems by using motor current signals of electric motors: A benchmark data set for data-driven classification. In Proceedings of the PHM Society European Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 5–8 July 2016; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Yang, W.; Dong, R.; Hu, J. Limited data rolling bearing fault diagnosis with few-shot learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 110895–110904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Chai, X.; Yu, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Improved prototypical networks for few-shot learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 140, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, T.; Lv, H.; Pan, T. Meta-learning as a promising approach for few-shot cross-domain fault diagnosis: Algorithms, applications, and prospects. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 235, 107646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Shao, H.; Zhou, X.; Cai, B.; Liu, B. Generalized MAML for few-shot cross-domain fault diagnosis of bearing driven by heterogeneous signals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 230, 120696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).