Abstract

Detecting aircraft in Airport Surface Movement Radar (SMR) imagery presents a unique challenge rooted in the conflict between object symmetry and data asymmetry. While aircraft possess strong structural symmetry, their radar signatures are often sparse, incomplete, and highly asymmetric, leading to target loss and position jitter in traditional detection algorithms. To overcome this, we introduce SWCR-YOLO, a keypoint detection framework designed to learn and enforce the target’s implicit structural symmetry from its imperfect radar representation. Our model reconstructs a stable aircraft pose by localizing four keypoints (nose, tail, wingtips) that define its symmetric axes. Based on YOLOv11n, SWCR-YOLO incorporates a MultiScaleStem module and wavelet transforms to effectively extract features from the sparse, asymmetric scatter points, while a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention (MSCA) module refines salient information. Crucially, training is guided by a Geometric Regularized Keypoint Loss (GRKLoss), which introduces a symmetry-based prior by imposing angular constraints on the keypoints to ensure physically plausible pose estimations. Our symmetry-aware approach, on a real-world SMR dataset, achieves an mAP50 of 88.2% and reduces the trajectory root mean square error by 51.8% compared to MTD-CFAR pipeline methods, from 8.235 m to 3.968 m, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling asymmetric data for robust object tracking.

1. Background

As the core sensing equipment in modern airport ground traffic management systems, Airport Surface Movement Radar (SMR) plays an irreplaceable role in ensuring aircraft taxiing safety, enhancing operational efficiency, and preventing ground conflicts [1]. By actively emitting electromagnetic waves and receiving target echoes, SMR achieves all-weather, round-the-clock detection of all moving and stationary non-cooperative targets within runways, taxiways, and apron areas [2]. This capability operates independently of airborne transponders (e.g., ADS-B or Mode S), effectively covering non-cooperative targets such as aircraft, service vehicles, and personnel, thereby significantly enhancing the completeness and robustness of airport ground surveillance [3,4].

With the continuous growth of global air traffic, particularly the intensifying pressure of high-density ground operations during peak hours at major hub airports, higher demands are placed on the object detection accuracy, tracking stability, and real-time response capabilities of SMR systems. However, constrained by the physical imaging mechanisms of radar and complex operational environments, existing SMR systems still face numerous technical challenges in practical applications, severely limiting further improvements in their intelligence levels [5,6].

First, constrained by the characteristics of near-horizontal beam illumination, target objects are very easily partially obscured due to their own structure or surrounding obstacles [7]. Since SMRs typically employ near-horizontal polarization and low-elevation scanning antenna beam designs, aircraft targets often appear partially visible in radar images and are susceptible to occlusion by nearby buildings, other aircraft, or terrain undulations. Furthermore, distinct scattering characteristics exist across different aircraft sections: metallic protrusions like landing gear, engines, wingtips, and antennas act as strong scattering centers, while large flat surfaces such as the fuselage belly and upper wing surfaces tend to reflect incident energy away from the receiving direction, resulting in weak or absent echo signals [8]. This uneven distribution of Radar Cross Section (RCS) causes aircraft to appear as discrete clusters of strong scattering points in radar imagery rather than continuous, complete outlines, posing significant challenges for overall target identification and pose estimation [9].

Second, traditional detection algorithms suffer significant performance degradation in low-speed and stationary scenarios. Current mainstream SMR systems predominantly employ a technical approach combining Moving Target Detection (MTD) with Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) detection [10]. MTD utilizes the Doppler effect to distinguish moving targets from ground clutter. However, when aircraft are taxiing, decelerating, waiting, or parked, their radial velocity approaches zero. This causes Doppler shifts to fall within the main clutter lobe, making targets highly susceptible to suppression by MTD filters and resulting in detection failures. Simultaneously, in dense target environments, the presence of strong scatterers within the reference window in CFAR algorithms elevates the estimated local noise level, raising the detection threshold. This further suppresses the detection probability of weak or low-speed targets, creating a “masking effect” [11,12]. These issues collectively cause traditional methods to exhibit track discontinuities, jumps, or jitter during critical aircraft maneuvers such as approach, departure, and turns, severely impairing air traffic controllers’ situational awareness and decision-making.

Furthermore, limited radar image resolution and low signal-to-noise ratio(SNR) exacerbate the difficulty of detecting small targets [13]. Although modern SMR systems achieve high range and azimuth resolution, within a 6-kilometer detection range, typical commercial aircraft (such as the B737 or A320) occupy only a few to over ten pixel units in the image, falling squarely within the category of small targets. Compounded by clutter interference from environmental factors like rain, snow, fog, and ground reflections, the target SNR is often low. Traditional methods relying on threshold segmentation and morphological processing struggle to reliably extract target features, leading to frequent false positives and false negatives [14].

Recently, deep learning has achieved breakthroughs in computer vision, demonstrating powerful feature extraction and pattern recognition capabilities, particularly in tasks like object detection, semantic segmentation, and keypoint localization [15]. Single-stage detectors, exemplified by the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series [16], have gained widespread adoption in fields such as remote sensing, medical imaging, and autonomous driving due to their high real-time performance and balanced accuracy. However, directly transferring general-purpose visual models to radar image processing presents significant challenges. First, radar and optical images exhibit fundamental differences in imaging mechanisms, texture features, and noise patterns. Second, existing models are predominantly designed for large-scale objects and are ineffective in detecting small, sparse scatter points within SMR images. Third, the lack of effective modeling for aircraft geometric structure a priori knowledge leads to unreasonable pose estimation.

Moreover, the inherent structural symmetry of aircraft, particularly bilateral symmetry along the fuselage axis, introduces a fundamental ambiguity in pose estimation: without explicit geometric constraints, keypoint detectors may confuse left and right wings or flip the nose-tail direction, especially when radar echoes are sparse or asymmetric. While such symmetry-induced ambiguities have been studied in optical-domain pose estimation (e.g., for cars, humans, or household objects), existing solutions often rely on texture cues, color gradients, or dense contour information that are absent in SMR imagery. Consequently, directly applying these methods to radar data leads to physically implausible poses and unstable trajectories.

To address these challenges, we propose SWCR-YOLO (Stem-WaveletConvolution-Regularized YOLO), a novel keypoint detection framework tailored for airport surface movement radar imagery. This method abandons the traditional bounding box detection paradigm. Instead, it precisely locates four key structural points, the nose, tail, and both wings, to reconstruct the target’s center and heading angle. This fundamentally avoids track jitter and loss issues caused by changes in echo energy distribution during low-speed/stationary states. Building on this foundation, we systematically optimize multiple dimensions, including network architecture, feature extraction, attention mechanisms, and loss functions, to construct a lightweight, high-precision keypoint detection model highly adapted to radar image characteristics. We provide a new technical pathway to achieve highly reliable, intelligent airport surface surveillance.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows.

- Proposing a novel aircraft keypoint detection framework (SWCR-YOLO) specifically tailored for airport surface movement radar images. This method innovatively transforms aircraft detection into locating four keypoints effectively resolving trajectory jitter and target loss issues common in traditional algorithms during slow, stationary, or turning aircraft.

- A network architecture deeply adapted to the characteristics of small radar objects is designed. Addressing the small size and low SNR of aircraft objects in radar images, we deeply optimize the YOLOv11n architecture.

- Deliberately designed a loss function and attention mechanism integrating geometric prior knowledge. To further improve keypoint localization accuracy, we introduced a Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention (MSCA) module to optimize feature representation. Concurrently, we designed a Geometric Regularized Keypoint Loss (GRKLoss) that incorporates a priori knowledge of aircraft geometry into training by imposing constraints on the angle between fuselage and wing axes. This effectively corrects unreasonable pose predictions and accelerates model convergence.

- Experiments demonstrate that our proposed SWCR-YOLO algorithm significantly outperforms baseline models across key metrics, reducing the root mean square error (RMSE) of flight paths by 51.8% compared to traditional radar algorithms. This provides an effective and reliable new technical approach for precise target detection and tracking in airport surface movement radar systems.

2. Related Work

In recent years, the rapid advancement of deep learning technology has driven the widespread application of deep neural network models in radar object detection [17]. Yavuz et al. proposed a convolutional neural network-based radar object detection method. This approach generates data by simulating the range-Doppler ambiguity function of radar waveforms and uses the resulting range-Doppler spectrum as network input. With only a slight increase in computational complexity, its detection performance significantly outperforms traditional CA-CFAR detectors [18]. Su et al. [19] proposed a graph convolutional network (GCN)-based maritime radar object detection method. By structuring radar signals as graph data to fully leverage their spatiotemporal correlation characteristics, it effectively detects maritime objects at SNR above −5 dB while suppressing false alarms from pure clutter regions not adjacent to objects. Pan et al. [20] proposed an impulse radio ultra-wideband (IR-UWB) radar system and designed a low-complexity CNN model based on self-attention for human event detection. This model significantly outperformed other traditional machine learning models and techniques while maintaining low computational complexity; Akhtar et al. [21] proposed an FMCW radar object detection method based on an optimized hybrid deep learning (OHDL) model. By constructing radar echo data cubes and utilizing an enhanced particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize hyperparameters, they achieved precise prediction of distance-Doppler plots and joint detection of target distance and velocity; Huang et al. [22] proposed a 3D ground-penetrating radar image crack detection method integrating ECA-ResNet with a tensor voting algorithm. By locating crack grid centers as feature points via the network and employing tensor voting for continuous crack path reconstruction, they achieved a 90% crack extraction rate.

Under this trend, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of object detection algorithms, with their outstanding balance of real-time performance and accuracy, have also been gradually introduced into the field of radar object detection [23]. Luo et al. [24] proposed a bidirectional path aggregation attention network based on YOLOv5s for aircraft target detection in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images. This approach enhances the extraction of multi-scale scattering features and effectively suppresses interference from complex backgrounds and speckle noise by introducing the enhanced path aggregation (IEPA) module and residual washing attention (ERSA) module; Wu et al. [25] proposed a YOLOv5-based Multi-Pulse Lidar System (YMPL), which converts one-dimensional pulse signals into two-dimensional images and utilizes the YOLO algorithm for object recognition, effectively improving lidar object detection accuracy and anti-interference capabilities in foggy environments. Zheng et al. [26] introduced the Tunnel Lining Anomaly Detection network TLAD-YOLO for ground-penetrating radar B-scan images, which incorporates a lightweight Spatial and Channel Synergistic Multi-shape Attention (SCSMSA) module within the YOLOv11n framework to enhance feature expression capabilities for complex scenes and multi-scale anomalies. Combined with Ghost convolution to reduce model parameters and computational overhead, this approach improves detection accuracy for railway tunnel linings. Liu et al. [27] introduced the YOLOv8-pose keypoint detection model to achieve automated detection of airport runway force transmission rod endpoints. By constructing small-sample B-scan datasets from 600 MHz and 900 MHz ground-penetrating radar and designing a multi-constraint (MC) loss function integrating Keypoint Angular Similarity (KAS) and Midpoint Similarity (KMS), the model’s ability to model the spatial geometric relationship between the two ends of the force transmission rod was effectively enhanced, significantly improving the accuracy and robustness of vertical corner misalignment detection.

In computer vision, the challenge of pose ambiguity due to object symmetry has long been recognized. For bilaterally symmetric objects (e.g., cars, chairs, or humans), standard keypoint detectors often suffer from left-right confusion, leading to incorrect orientation estimates. To address this, several approaches incorporate geometric or semantic priors. Tung et al. [28] proposed a self-supervised method that enforces consistency under known symmetries. Pavlakos et al. [29] used ordinal depth relationships to resolve front-back ambiguity in human pose. However, these methods assume rich visual appearance cues (e.g., texture, shading, or silhouette continuity) that are largely missing in radar imagery. In contrast, our work adapts the principle of geometric regularization to the radar domain, where symmetry must be inferred from sparse scatter points rather than dense pixel patterns. By explicitly modeling the minimum angle between fuselage and wing axes, SWCR-YOLO resolves ambiguity without relying on appearance-based disambiguation.

Traditional methods employ moving target detection techniques, which filter out signals when aircraft are moving slowly or stationary. Motivated by the limitations of traditional methods, we propose an innovative application of the improved YOLOv11 keypoint detection model to aircraft detection in surface movement radar imagery. By locating four keypoints: nose, left wing, right wing, and tail, it effectively mitigated common issues in traditional methods, such as track jitter and loss during slow movement, stationary states, or turns. First, the MultiScaleStem module was designed and integrated with WTConv, HWD, and MSCA modules to enhance multiscale feature extraction and keypoint representation capabilities. Subsequently, the geometric regularization keypoint loss function GRKLoss was proposed, introducing axis angle constraints and a dynamic weighting mechanism based on fuselage-wing aspect ratios. This suppresses unreasonable pose estimates, improving robustness for small objects and keypoint localization accuracy. Finally, based on high-precision keypoint detection results, the aircraft target center point parameters are rapidly calculated. This technical framework achieves high-precision perception of airport surface targets, providing a feasible technical pathway for enhancing the intelligent detection capabilities of surface movement radar systems.

3. The SWCR-YOLO Framework: Symmetry-Aware Keypoint Detection for SMR

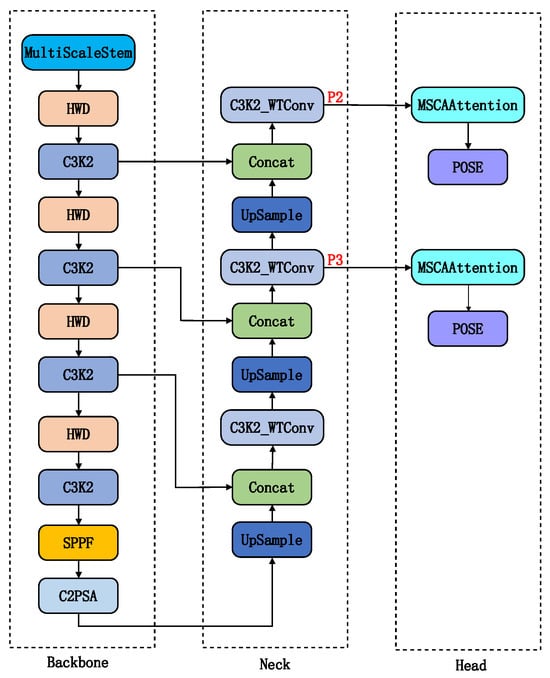

To address the critical challenges in object detection within SMR images, we deeply optimized the YOLOv11 architecture [30] and proposed the SWCR-YOLO model. The network architecture is shown in Figure 1. First, in order to improve the model’s detection ability of small objects, the feature pyramid structure is redesigned: the P4 and P5 high-level feature layers with large computation and unfavorable for small target detection are removed. Since the P4 and P5 layers perform 16× and 32× downsampling respectively, they lose significant detail information and are unsuitable for detecting small objects. A high-resolution P2 detection layer (4× downsampling) is added to retain more shallow spatial detail information. This constructed a dual-detection-head structure focused on small and medium-sized objects, significantly enhancing sensitivity to minute targets. Second, for feature extraction, we designed the MultiScaleStem module to replace the traditional first layer of the backbone network. Its multi-branch convolutional structure fuses texture and structural information across different scales, effectively addressing the issue that the target scatter points in SMR images are discrete. Simultaneously, we introduced an attention mechanism to improve the ability of the model to focus on key feature regions. Furthermore, we innovatively integrated the HWD wavelet downsampling module. By employing Haar transforms, it preserves more spatial details while avoiding information loss inherent in conventional downsampling. The C3K2_WTConv module leverages the lightweight nature and large receptive field advantages of wavelet convolutions, improving feature extraction efficiency for small objects. Finally, we designed specialized loss functions to improve bounding box regression accuracy and keypoint pose estimation rationality. These combined enhancements aim to comprehensively elevate the model’s detection performance and robustness under low signal-to-noise ratios and complex backgrounds.

Figure 1.

Improved YOLOv11 Network Architecture.

3.1. MultiScaleStem Module

In SMR images, aircraft targets generally consist of sparse and discrete scatter points, exhibiting multiscale texture and structural features. Traditional network STEM modules commonly employ single-scale convolutional kernels for initial feature extraction. This approach struggles to simultaneously capture scatter points of varying sizes and their combination patterns, often losing critical detail information for small objects at an early stage, thereby limiting subsequent detection performance.

To address these limitations, the MultiScaleStem module is designed to build a more robust initial feature extractor. By processing information across multiple scales in parallel, it preserves richer spatial details and textural information from the outset of feature extraction. This provides subsequent network layers with a more discriminative and robust feature representation, enhancing the model’s initial perception capabilities for weak and small targets. The design of MultiScaleStem is motivated by two key observations: (i) SMR imagery shows aircraft scatter points exhibit multi-scale characteristics, which single-scale convolutions fail to capture. (ii) Theoretical support stems from multi-scale feature fusion principles in computer vision, where parallel branches enhance representation diversity.

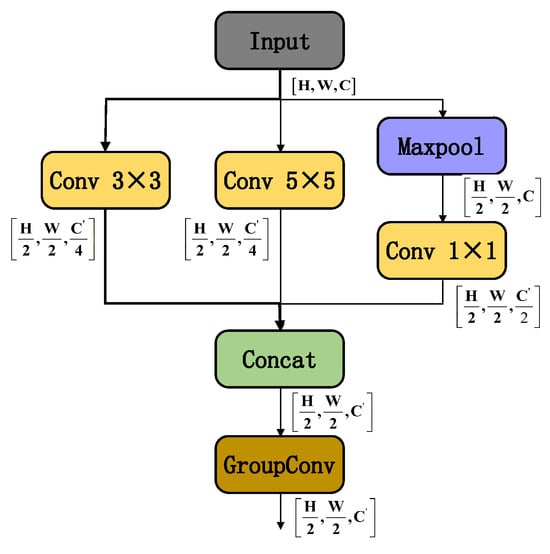

The MultiScaleStem module is used to replace the first convolutional layer of the original YOLOv11n backbone. As illustrated in Figure 2, its multi-branch structure allows for preliminary multiscale feature extraction: the 3 × 3 convolution branch extracts fine-texture features, the 5 × 5 convolution branch captures medium-scale structural information, and the “MaxPool + 1 × 1 convolution” path extracts strong reflection features of radar scatter points. This design greatly improves the network’s joint representation ability for scatterer distribution, object contours, and energy concentration characteristics in radar images by multiscale feature fusion. It offers a multi-dimensional feature base for the subsequent feature pyramid construction in the backbone, enhancing object detection robustness in complex environments.

Figure 2.

MultiScaleStem Module Structure.

For computational efficiency, the module controls the overall number of parameters through a channel allocation strategy (each convolution branch takes 25% output channels and the pooling branch takes 50%), maintaining computational cost similar to conventional large convolution kernel methods. Grouped convolutions (groups = ) split output channels into groups for sparse connections. This structure retains the variety of multi-branch features and merges multiscale features through intra-group local interactions while reducing parameters.

3.2. HWD Module

In convolutional neural networks, traditional downsampling operations effectively aggregate local features and expand the receptive field, but inevitably result in the loss of crucial spatial information. For object detection tasks involving SMR images that require fine details, this early-stage information loss is detrimental, as it weakens the model’s ability to perceive small objects.

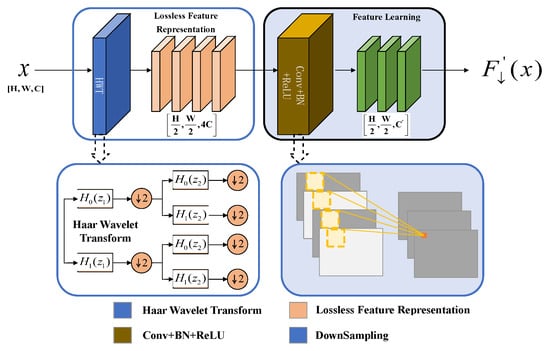

We propose the HWD (Haar wavelet downsampling) module to replace the Conv downsampling module in the original Backbone. The wavelet transform decomposes an image into low-frequency approximation components and high-frequency detail components. The downsampling operation primarily affects the low-frequency components to reduce data volume, while the high-frequency components are preserved and can be used for reconstruction. This approach minimizes the loss of critical detail information, fundamentally differing from traditional methods that directly discard pixels. Compared with the traditional downsampling, the features extracted by HWD preserve more boundary, texture, and detail information of the object, which is suitable for extracting and detecting low-observable aircraft objects from Surface Movement Radar images [31]. It first uses Haar wavelet transform to expand the number of feature map channels and reducing resolution without information loss. Then, convolutional operations are used to process the features, removing redundant information. The 1D Haar transform Scaling function and Wavelet Basis Function for the first stage are given by

where, is defined as follows:

In Equation (2), j and k denote the stage and direction of the Haar transform, respectively. After applying the one-dimensional Haar transform to the input image, the original image is divided into two parts: the low-frequency component and the high-frequency component . Subsequently, the one-dimensional Haar transform is applied sequentially column-wise, thereby dividing the original image into four parts. These four components are then concatenated and fed into the feature learning block (convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

HWD Module Structure.

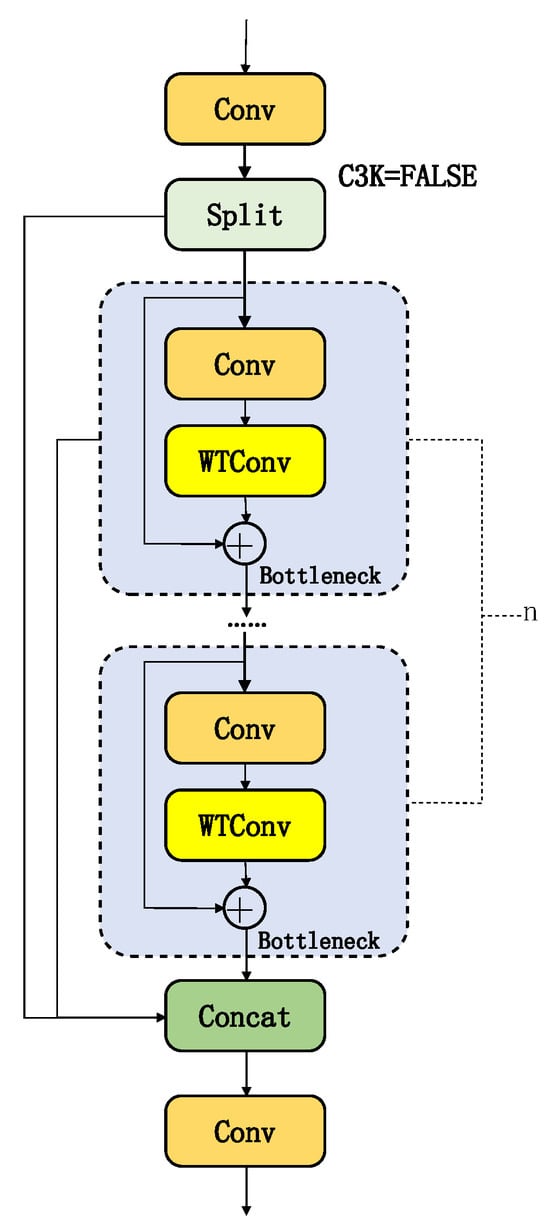

3.3. C3K2_WTConv Module

In convolutional neural networks, expanding the receptive field to capture global contextual information has traditionally relied on increasing the size of convolutional kernels or deepening the network. However, this inevitably leads to a sharp increase in the number of parameters and computational cost. To address this issue, the C3K2_WTConv module is designed to achieve effective coverage of a large receptive field while maintaining a lightweight model. This enables the capture of richer local and global features at a lower cost in terms of parameters.

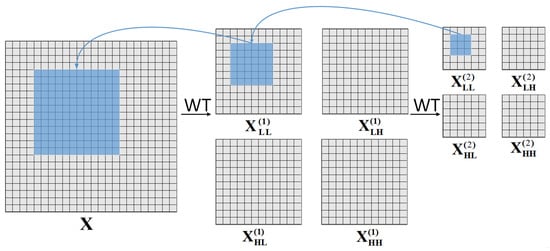

WTConv decomposes input features using Haar wavelets into low-frequency components and high-frequency components, then reconstructs the output via inverse wavelet transform [32]. Figure 4 illustrates the execution of a 3 × 3 convolution on the low-frequency subband of the second-level wavelet domain X. The corresponding receptive field encompasses a 12 × 12 area of the input feature map, markedly decreasing the number of parameters. The high-frequency subband is concurrently retained in the inverse wavelet transform to avert the loss of high-frequency information. The components are then reconstructed and output via the inverse wavelet transform. This design significantly increases the receptive field while eliminating the parameter redundancy typical of conventional big convolutional kernels, hence improving its capacity to extract features from blurred outlines and varied forms [33].

Figure 4.

Principle of WTConv.

To maintain consistency with feature processing in the HWD (Haar wavelet downsampling) module of the Backbone, the second 3 × 3 standard convolution in the Bottleneck of the C3K2 module within the Neck section is replaced with WTConv (wavelet convolution), while preserving the residual connection structure, as shown in Figure 5. This design enhances the extraction of multi-scale features in radar images through the continuity of wavelet domain processing, optimizing the hierarchical fusion of edge and texture features for low-observable objects.

Figure 5.

C3K2_WTConv Network Architecture.

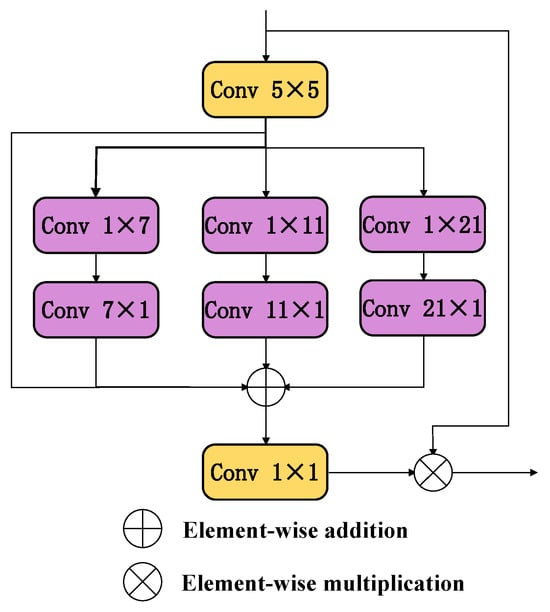

3.4. MSCAAttention Module

In convolutional neural networks, while the self-attention mechanism in Transformers effectively encodes long-range dependencies, its quadratic computational complexity brings significant challenges when processing high-resolution images. Simultaneously, the limited receptive field of traditional convolutions makes it difficult to capture global contextual information effectively, which constrains the understanding of complex scenes and the recognition of multi-scale objects.

MSCAAttention (Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention) is an efficient multi-scale convolutional attention module. Through its lightweight design, it integrates multi-scale contextual information to improve keypoint detection accuracy in YOLOv11 for pose estimation tasks. This module replaces traditional large-kernel convolutions with multi-branch deep strip convolutions, reducing computational complexity while enhancing feature representation capabilities for object keypoints.

The MSCA module [34], illustrated in Figure 6, comprises three core components: First, deep convolutions aggregate local information; second, multi-branch deep strip convolutions capture multi-scale contextual information; finally, 1 × 1 convolutions model inter-channel relationships. The output of the 1 × 1 convolutions directly serves as attention weights to adjust the MSCA input. We integrate the MSCAAttention module into the Head of YOLOv11.

Figure 6.

MSCAAttention Network Architecture.

3.5. Symmetry-Constrained Geometric Regularized Keypoint Loss

The overall loss function for keypoint detection typically consists of four components: classification loss for object detection, bounding box regression loss, keypoint confidence loss, and keypoint localization loss. The YOLOv11n model employs CIOU as the bounding box regression loss function. However, in SMR imagery, the small size of aircraft objects often results in limited overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, leading to generally low IOU values and consequently affecting the detection accuracy of small objects. Simultaneously, aircraft appear in radar images as discrete clusters of strong scatter points rather than continuous, complete contours. This low SNR and high detection difficulty make overall object recognition and pose estimation challenging. We introduce two loss function improvements: First, incorporating EIoU loss as the bounding box regression term. Second, proposing a Geometric Regularization Keypoint Loss (GRKLoss) to strengthen the geometric plausibility of keypoint localization.

First, we adopt EIOU as the bounding box regression loss. EIOU further optimizes CIOU by placing greater emphasis on the geometric center distance and size discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth boxes. Crucially, EIOU incorporates an edge length difference term that directly quantifies deviations in both width and height dimensions, making the loss function more sensitive to box size matching [35]. The EIOU loss function is defined as follows:

where IOU measures the overlap between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes; represents the Euclidean distance between the center points of the predicted bounding box b and the ground truth bounding box , measuring the deviation between the two center points; c denotes the diagonal length of the minimum bounding rectangle that can simultaneously enclose both the predicted and ground truth boxes, reflecting their spatial relationship. Similarly, and denote the squared differences in width and height between the ground truth and predicted boxes, respectively. represents the width of the minimum bounding rectangle, and denotes its height.

To further enhance the accuracy and geometric plausibility of keypoint detection, we propose the Geometric Regularized Keypoint Loss function (GRKLoss). This method leverages the a priori geometric structure of aircraft object keypoints by introducing axis angle constraints, enforcing that the angle between the wing axis and fuselage axis exceeds 30° to suppress physically implausible abnormal postures. A dynamic weighting mechanism is introduced in GRKLoss to optimize the model’s robustness toward small targets. It adaptively adjusts the weighting coefficient of the constraint term based on the aspect ratio of the object’s fuselage-to-wing dimensions. Finally, is treated as a regularization term, weighted by a fixed coefficient , and combined with the original keypoint baseline loss of YOLOv11n to form the proposed keypoint loss . This effectively improves the plausibility of pose estimation and detection accuracy for small-scale aircraft objects.

The original YOLOv11n keypoint base loss is as follows:

In the above formula, denotes the Euclidean distance between the predicted position and the ground truth position of the kth keypoint for the ith object [27], where and represent the ground truth and predicted coordinates, respectively. indicates the area of the corresponding object bounding box. The standard deviation parameter , is used to prevent division-by-zero errors, and represents the similarity between keypoints of the object. In this task, all four keypoints of the object are visible, so the total number of keypoints , the mask term , and the keypoint loss factor .

The geometric regularization constraint loss , assuming the nose coordinates of the aircraft target are , the tail coordinates are , and the coordinates of the two wings are and respectively, the loss function formula is expressed as follows:

where,

The design core of the dynamic weight is to establish an adaptive feedback mechanism based on the target’s geometric morphology. This mechanism uses the fuselage length-to-width ratio R as a proxy signal to perceive prediction uncertainty or geometric anomalies. The scaling factor 5 in the formula is used to enhance the system’s sensitivity to deviations of R from normal values, ensuring that the weight can respond quickly. The Sigmoid function ensures the smoothness and gradient stability of weight changes. Finally, the weight is restricted to the range (0.5, 1.0).

The key loss functions are as follows:

where the geometric regularization constraint weight coefficient is empirically set to 0.4, which was identified as the optimal value through extensive ablation studies.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Construction and Preprocessing of Dataset

The datasets used were collected from the SCR-25 (Abbr. of Sun Create Radar) surface movement radar systems at Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport (CGO) and Lanzhou Zhongchuan International Airport (LHW), as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

SCR-25 radars at Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport (left) and Lanzhou Zhongchuan International Airport (right).

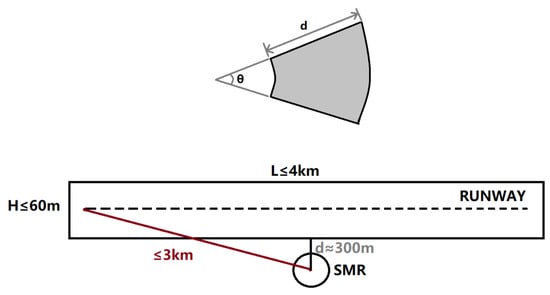

The Surface Movement Radar at an airport is a fixed-site installation that typically employs real-aperture imaging. To enhance its angular resolution and target discrimination capability, the system utilizes a large physical antenna aperture (21 feet for this specific radar). Concurrently, a high sampling rate (40 MHz for the comparative radar, yielding a range resolution of 3.75 m) is adopted. Consequently, each imaging cell is not a standard rectangle or square, but rather a sector (Figure 8). The imaging principle of SMR real-aperture radar is fundamentally different from that of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). Given that commercial transport aircraft have typical dimensions of approximately 35 m × 33 m and the SMR is tasked with monitoring the runway vicinity, it is estimated that a single transport aircraft at a range of 3 km would occupy approximately 15 imaging cells. Because the angular resolution is defined in polar coordinates, image quality is range-dependent: the closer an aircraft is to the SMR, the less significant the effect of angular resolution, resulting in a better image. Conversely, the farther the range, the more pronounced the effect, leading to a degradation in image quality. For this radar, the key parameters are = 0.32° and d = 3.75 m. The main technical parameters and performance indicators of these radar systems are shown in Table 1.

Figure 8.

Geometry of SMR: coverage area, runway layout, and resolution cell structure.

Table 1.

Main Technical Parameters and Performance Indicators of the SCR-25 Surface Movement Radar.

Using the radar station as the image center point, map the echo information from each bearing and range cell of the radar onto a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system image. Let the coordinates of target point P in the radar polar coordinate system be , where represents the radial distance between the target and the radar, and represents the azimuth angle of the target relative to the radar. After coordinate transformation, point P becomes . Let the coordinates of point in the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system image be . The coordinate mapping formula is as follows:

where (CenterX, CenterY) represents the center coordinates of the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system image.

The 5587 radar images collected for this study originate from the following sources: two video datasets (totaling 1192 images) from Lanzhou Zhongchuan International Airport (LHW) and six video datasets (totaling 4395 images) from Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport (CGO). To ensure objective model evaluation, the validation set was constructed using independent video sequences: one video sequence (582 images) from Lanzhou Airport and one video sequence (540 images) from Zhengzhou Airport, collectively forming a 1122-image validation set. The remaining 6 video datasets (4465 images) were divided into a training set (3929 images) and a validation set (536 images) at a 7.33:1 ratio, guaranteeing the independence of validation data during training. To enhance the performance of aircraft keypoint detection algorithms, we performed high-quality annotations on the radar images. All images were annotated by experienced professionals using the LabelMe annotation tool to mark the aircraft’s four key points, ensuring data accuracy and reliability. Detailed statistics of the dataset are presented in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Detailed Dataset Statistics.

4.2. Experimental Environment and Hyperparameter Settings

The experimental environment configuration is shown in Table 3. All experiments were conducted under identical environmental settings. To ensure experimental rigor and fairness, we standardized the experimental configuration parameters. Specific locations are detailed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Experimental Hardware Environment.

Table 4.

Experimental Hyperparameters.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

This study evaluates performance using Precision (P), Recall (R), Parameters (Params), Mean Average Precision (mAP), and Frames Per Second (FPS). Precision measures the ratio of true positives to predicted positives. Recall assesses the ratio of correctly identified positives to actual positives. Mean Average Precision provides a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s detection performance across object categories, and Frames Per Second indicates the number of frames processed per second by the model. The calculation of each metric is as follows:

4.4. Detection Performance Analysis

As shown in Table 5, evaluation results of SWCR-YOLO on the test set (1122 images) demonstrate that compared to YOLOv11n, our model achieves a 6.0% increase in precision (P) to 92.5% and a 4.5% increase in recall (R) to 89.9%, while reducing the number of parameters by 41% (5.39 M vs. 3.18 M), while mAP50 and mAP50–95 improved by 3.7% and 2.4% to 88.2% and 61.2%, respectively. Despite a 35.8% increase in computational complexity (9.1 vs. 6.7 GFLOPs), SWCR-YOLO achieves a 74% improvement in the mAP50/Parameters ratio through multi-scale feature fusion optimization. This significantly enhances parameter utilization, making it more suitable for long-term operation on edge devices.

Table 5.

Comprehensive Comparison of Experimental Results. Bold indicates the best results.

Compared to lightweight YOLO models, our approach achieves improvements across all metrics. This is primarily due to our modifications to the YOLOv11 architecture, making it more suitable for this task. These enhancements not only boost detection accuracy but also increase detection efficiency. When compared to heavyweight models, our detection capabilities have also improved, while achieving a significant increase in detection efficiency. Our model parameters are only one-tenth of those in RT-DETR-L.SWCR-YOLO achieves an effective enhancement and balance between detection accuracy and efficiency, further validating the effectiveness of this improved model for detecting aircraft keypoints in radar images.

4.5. Ablation Study

To systematically validate the effectiveness of each component proposed in our SWCR-YOLO model, we conducted a comprehensive ablation study. Starting with the YOLOv11n baseline model, we incrementally integrated our proposed modifications: the redesigned feature pyramid, the MultiScaleStem module, the wavelet transform blocks (HWD and C3k2_WTConv), the MSCAAttention module, and finally, the enhanced loss functions (EIOU and GRKLoss). The performance of each configuration was evaluated on the independent test set using Precision (P), Recall (R), mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP50) and 0.5–0.95 (mAP50–95), as well as model complexity metrics (Parameters and GFLOPs). The detailed results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ablation study of SWCR-YOLO. The checkmark (✓) indicates the inclusion of the corresponding module. The baseline is the original YOLOv11n model. “FP” refers to our Feature Pyramid modification (adding P2, removing P4/P5). Exp 1–5 uses CIOU. Bold indicates the best results.

The study begins with the baseline YOLOv11n model (Exp 1), which achieves an mAP50 of 84.5%. In Exp 2, we adapted the network architecture for small radar objects by adding a high-resolution P2 detection layer and removing the deeper P4/P5 layers. This change immediately yielded a 0.5% improvement in mAP50 and, more importantly, reduced the model’s parameters by 35% and GFLOPs by 25%, confirming the efficiency of this streamlined structure for the task at hand. Next, the MultiScaleStem module was introduced (Exp 3) to enhance initial feature extraction. This led to a notable 0.7% increase in mAP50 to 85.7%, demonstrating its superior capability in capturing multi-scale features from sparse radar scatter points.

The integration of wavelet transforms (Exp 4), including Haar Wavelet Downsampling (HWD) and Wavelet Convolution (WTConv), marked the most significant performance leap among the architectural changes, boosting the mAP50 by 1.1–86.8%. This validates our hypothesis that wavelet-based operations can effectively expand the receptive field and reduce information loss during downsampling, which is crucial for preserving the fine details of small targets. The subsequent addition of the MSCAAttention module (Exp 5) further refined the feature representation by focusing on key salient regions, contributing another 0.7% gain in mAP50.

Finally, we evaluated the impact of the loss function optimizations. Replacing the original CIOU loss with EIOU Loss (Exp 6) provided a clear improvement in bounding box regression accuracy, raising the mAP50 to 87.9%. This highlights the effectiveness of EIOU in handling small targets. The final model, SWCR-YOLO (Exp 7), incorporates our proposed Geometric Regularized Keypoint Loss (GRKLoss). This final addition pushed the mAP50 to 88.2% and mAP50–95 to 61.2% by enforcing physically plausible pose constraints, thereby correcting unreasonable keypoint predictions. In summary, the ablation study confirms that each proposed module contributes positively and synergistically to the final model’s superior performance, justifying the design of SWCR-YOLO.

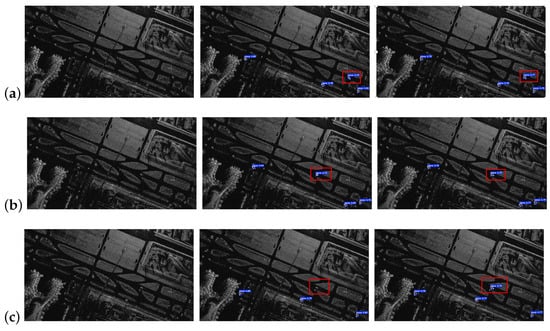

4.6. Visual Comparison of Detection Results

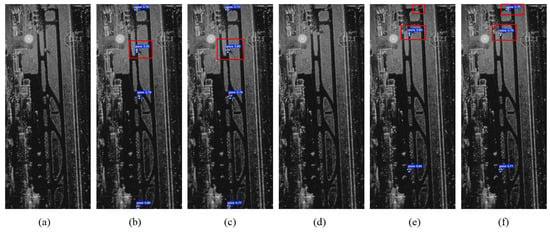

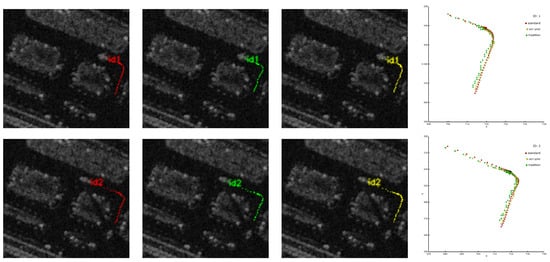

As shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, compared to YOLOv11n, SWCR-YOLO demonstrates higher localization accuracy in detecting the left and right wings of aircraft, effectively reducing false positives and false negatives in keypoint detection. Furthermore, under the test scenario at Lanzhou Airport (where the training dataset contained only 517 sample images), the model still maintains stable detection performance, further validating its generalization capability.

Figure 9.

Inference results of YOLOv11n and SWCR-YOLO on radar images from Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport: (a) Original image, (b) YOLOv11n, (c) SWCR-YOLO. The blue boxes represent the detected aircraft and keypoints, and the numbers are the confidence of the prediction.

Figure 10.

Inference results of YOLOv11n and SWCR-YOLO on radar images of Lanzhou Zhongchuan International Airport (a,d) Original images (b,e) YOLOv11n (c,f) SWCR-YOLO. The blue boxes represent the detected aircraft and keypoints, and the numbers are the confidence of the prediction.

4.7. Comparison with Traditional Radar Algorithms

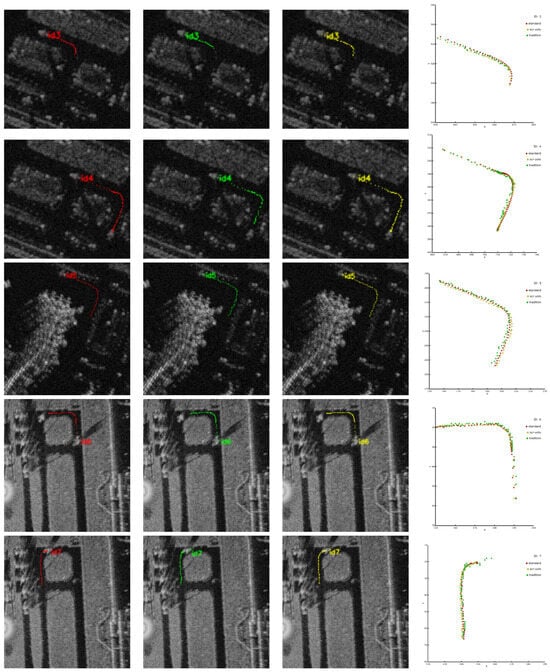

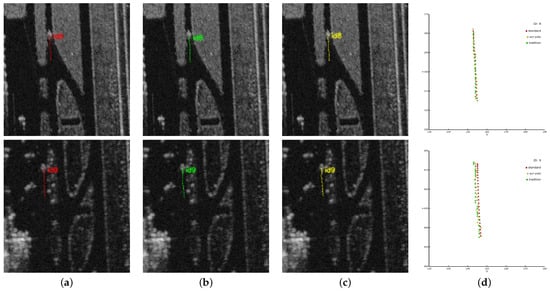

To provide a comprehensive evaluation, the performance of SWCR-YOLO was benchmarked against a traditional radar processing chain commonly employed in Airport SMR systems. This traditional baseline algorithm combines MTD with CFAR detection to generate aircraft tracks. The process is implemented as follows: (i) MTD. The initial stage processes sequences of coherent radar pulses to perform Doppler processing. By analyzing the phase shifts between consecutive pulses, the MTD filter suppresses stationary returns, such as ground clutter, while enhancing targets with non-zero radial velocities. This step is effective for moving aircraft but struggles with stationary or slow-moving targets whose Doppler shifts fall within the clutter filter’s rejection band. (ii) CFAR Detection. The clutter-suppressed output from the MTD stage is then fed into a Cell-Averaging CFAR detector. For each cell under test, the algorithm estimates the local background noise and clutter level by averaging the power of neighboring cells in a reference window. A detection threshold is dynamically calculated based on this estimate. If the power of the cell under test exceeds this threshold, it is declared a “hit.” This adaptive process aims to maintain a constant rate of false alarms across the radar’s coverage area. (iii) Centroid Calculation. Since a single aircraft typically generates multiple detection hits corresponding to its strong scattering centers (e.g., engines, landing gear, wingtips), a clustering algorithm is applied. Raw hits in close proximity are grouped into single plots. The geometric centroid of each cluster is then calculated to represent the aircraft’s estimated position for that specific radar scan. (iv) Track Filtering. Finally, the sequence of position centroids generated over multiple scans is processed by a Kalman filter. The filter performs track initiation, plot-to-track association, state prediction, and track maintenance. This final step smooths the trajectory; however, the resulting track is highly susceptible to positional jitter if the centroid of the clustered hits shifts between scans, and prone to track loss if the MTD or CFAR stages fail to detect the target.

The tracks generated by this MTD-CFAR pipeline serve as the baseline for evaluating the trajectory accuracy improvements achieved by our proposed SWCR-YOLO model. The experimental results are shown in Figure 11 and Table 7. The comparative analysis in Figure 11 indicates that, compared to traditional algorithms, the tracks generated by SWCR-YOLO demonstrate superior spatial alignment, continuity, and completeness. The trajectory instability of the traditional MTD-CFAR pipeline is clearly visible in Figure 11, particularly during segments where the aircraft decelerates, holds position, or executes low-speed turns (e.g., near taxiway intersections or holding points). This behavior is not merely a detection error but stems from fundamental limitations in the velocity-dependent detection paradigm. As the aircraft’s radial velocity approaches zero, its radar echoes fall within the main clutter lobe and are suppressed by the MTD filter. Scatter plot analysis reveals that SWCR-YOLO’s detection points cluster more tightly around the reference line, exhibiting significantly reduced dispersion than traditional algorithms. The quantitative analysis of root mean square error (RMSE) in Table 7 further validates this advantage. Under the SCR-25 radar’s 3.75-m distance sampling interval, SWCR-YOLO achieves a mean pixel-level RMSE of 1.058, corresponding to a meter-level error of 3.968. This represents a 51.8% reduction compared to the traditional algorithm’s 8.235, fully validating SWCR-YOLO’s significant improvement in flight path detection accuracy. To assess the statistical significance of the performance improvement, we conducted a paired t-test on the per-trajectory RMSE values across 9 independent aircraft sequences. The proposed SWCR-YOLO method achieved a mean pixel-level RMSE reduction of 1.058, with a highly significant p-value of <0.001.

Figure 11.

Algorithm comparison results for target trajectory detection, including: (a) standard reference trajectory, (b) trajectory detected by SWCR-YOLO algorithm, (c) trajectory detected by traditional algorithm, (d) scatter plot comparison of the three trajectories.

Table 7.

Comparison of RMSE errors between traditional trajectory detection methods and the SWCR-YOLO algorithm (pixels/meter).

5. Conclusions

This paper introduces a novel SWCR-YOLO model that combines SMR imagery with deep learning techniques for aircraft object detection. Building upon the traditional YOLOv11n architecture, it enhances small object detection capabilities by adding a P2 high-resolution detection layer while removing the P4/P5 large object layers. The MultiScaleStem module was designed to enhance shallow-layer small object representation through grouped feature interaction mechanisms. The C3k2_WTConv module, based on wavelet convolutions, employs Haar wavelet downsampling (HWD) and multi-scale convolutional attention (MSCA) to expand the receptive field while effectively preserving low-frequency structural information, thereby improving feature expression capabilities. For loss functions, EIoU Loss optimizes bounding box regression to improve small object box matching accuracy. A geometric regularized keypoint loss is proposed, introducing prior pose constraints to enhance the physical plausibility of keypoint distributions.

Experimental results validate SWCR-YOLO’s effectiveness. Compared to baseline YoloV11n, it achieves 92.5% accuracy, 89.9% recall, 88.2% mAP50, and 61.2% mAP50–95, representing improvements of 6.0%, 4.5%, 3.7%, and 2.4%, respectively. Compared to traditional trajectory detection methods, the root mean square error (RMSE) decreased from 8.235 m to 3.968 m, a 51.8% reduction, effectively mitigating target loss and positioning jitter issues. Compared with traditional trajectory detection methods, the root mean square error (RMSE) of the trajectory is reduced from 8.235 m to 3.968 m (decrease of 51.8%), effectively alleviating the issues of object loss and positional jitter.

In future work, we will further optimize the SWCR-YOLO model to expand its applicability in complex airport environments. While our method demonstrates significant robustness, a potential weakness arises in scenarios with extreme sparsity, such as when only two prominent scatter points are visible, creating an ambiguity between the nose-tail axis and the lateral axis. We will also address these challenges in our future work.Extending our method to other ground-traffic objects, such as vehicles and personnel, represents a promising yet challenging direction. Unlike aircraft, which have a fixed rigid structure, vehicles exhibit significant shape and size diversity, and personnel are highly non-rigid. To address this, future work could involve developing category-specific keypoint models for different vehicle types or integrating advanced human pose estimators for personnel tracking. The key challenge will lie in creating a unified framework capable of fusing these heterogeneous data sources for comprehensive scene understanding.

Although our dataset is currently limited to two airports, our method has been validated in practical deployments, which aligns with the common practice of training models for a specific airport. In the future, we will collect data from more airports to improve the model’s generalization, aiming for a unified model that can be deployed across multiple locations after a single training session. Furthermore, we are committed to promoting the deployment and field validation of this model at more major international airports. Our goal is to achieve broader, faster, and more accurate intelligent monitoring of airport surface activity through advanced deep learning technology, providing core technical support for future smart airports, low-altitude safety control, and autonomous guidance systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. (Xiaoyan Wang); methodology, X.W. (Xiaoyan Wang) and Z.H.; software, X.W. (Xiaoyan Wang) and J.J.; validation, Z.H.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, X.W. (Xiangli Wang); resources, P.L.; data curation, Z.T.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. (Xiaoyan Wang); writing—review and editing, M.W.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, X.W. (Xiaoyan Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (The data are not publicly available due to policy restrictions).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xiaoyan Wang, Jiangyan Ji, Peng Li, Xiangli Wang were employed by the company Sun Create Electronics Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Perl, E. Review of airport surface movement radar technology. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Radar, Verona, NY, USA, 24–27 April 2006; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz, M.; Hatke, G.; Campbell, S.D. Active geolocation using the small airport surveillance sensor (SASS) system. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Phased Array System & Technology (PAST), Waltham, MA, USA, 15–18 October 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vavriv, D.; Volkov, V.; Vinogradov, V.; Kravtsov, A.; Bulakh, E.; Sosnytskiy, S.; Sekretarov, S.; Nechaev, O.; Gikalov, V.; Gordeev, K.; et al. Surveillance radar “OKO”: An effective instrument for security applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th International Conference on Ultrawideband and Ultrashort Impulse Signals (UWBUSIS), Odessa, Ukraine, 4–7 September 2018; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Turin, F.; Pastina, D.; Lombardo, P.; Corucci, L. ISAR imaging of ground targets with an X-band FMCW Radar system for airport surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2014 15th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Gdansk, Poland, 16–18 June 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadmanesh, M.; Rashidi, A.; Schonfeld, P.; Rakas, J.; Marković, N. Aircraft surface movement and operation monitoring systems in general aviation and commercial airports: A state-of-the-art review. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2025, 49, 1009–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, F.; Frías, M.C.; Liu, J.; Simkus, K.; Karagkiolidou, S.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Challenges with regard to Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs) measurement of river surface velocity using Doppler radar. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Qiu, P.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. Radar and vision fusion for the real-time obstacle detection and identification. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2019, 46, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Dogaru, T. Full-wave characterization of rough terrain surface scattering for forward-looking radar applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2012, 60, 3853–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, Y. Surface movement radar target detection. In Proceedings of the 2014 12th International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP), Hangzhou, China, 19–23 October 2014; pp. 1993–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, B.; Huang, K.; Wu, Z.; Yan, K. Radar technology for river flow monitoring: Assessment of the current status and future challenges. Water 2023, 15, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wei, Z. Radar target MTD 2D-CFAR algorithm based on compressive detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 8–11 August 2021; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, D. Multi-fold high-order cumulants based CFAR detector for radar weak target detection. Digit. Signal Process. 2023, 139, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Robust small object detection on the water surface through fusion of camera and millimeter wave radar. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 15263–15272. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, P.S.; Alves, T.; Poussot, B.; Azarian, S. A review of radar detection fundamentals. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2022, 39, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Gupta, M.K.; Srivastava, C.; Dixit, P.; Pandey, S.K. Object detection using yolo: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Uttar Pradesh, India, 14–16 December 2022; pp. 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Guan, R.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Sha, X.; Yue, Y.; Lim, E.G.; Seo, H.; Man, K.L.; Zhu, X.; et al. Radar-camera fusion for object detection and semantic segmentation in autonomous driving: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 2094–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, F.; Kalfa, M. Radar Target Detection via Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Gaziantep, Turkey, 5–7 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Chen, X.; Guan, J.; Huang, Y. Maritime target detection based on radar graph data and graph convolutional network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Zhu, W.P.; Hasannezhad, M. Self-attention CNN based indoor human events detection with UWB radar. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.M.; Li, Y.; Cheng, W.; Dong, L.; Tan, Y. OHDL: Radar target detection using optimized hybrid deep learning for automotive FMCW. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 158, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Zang, B.; Yu, H. Three-dimensional ground-penetrating radar-based feature point tensor voting for semi-rigid base asphalt pavement crack detection. Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 21, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y. MS-YOLO: Object detection based on YOLOv5 optimized fusion millimeter-wave radar and machine vision. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 15435–15447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Chen, L.; Xing, J.; Yuan, Z.; Tan, S.; Cai, X.; Wang, J. A fast aircraft detection method for SAR images based on efficient bidirectional path aggregated attention network. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gong, F.; Yang, X.; Xu, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, W. The YOLO-based multi-pulse lidar (YMPL) for target detection in hazy weather. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 177, 108131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhang, A.; Shi, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z. TLAD-YOLO: Lightweight network for intelligent detection of railway tunnel lining anomalies using ground penetrating radar. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 241, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, X.; Chang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. Estimation of vertical rotational misalignment angle of airport runway dowel bars using keypoint detection with multi-constraint loss and B-scan GPR Images: Applying a small-scale dataset. Measurement 2025, 253, 117430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.Y.; Tung, H.W.; Yumer, E.; Fragkiadaki, K. Self-supervised learning of motion capture. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.01337. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlakos, G.; Zhou, X.; Daniilidis, K. Ordinal depth supervision for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7307–7316. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; He, X.; Wu, X. Haar wavelet downsampling: A simple but effective downsampling module for semantic segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chi, N.; Dai, Q. WaveFusion: A Novel Wavelet Vision Transformer with Saliency-Guided Enhancement for Multimodal Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 7526–7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.H.; Lu, C.Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.M.; Hu, S.M. Segnext: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Hua, L.; Kong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Dong, R.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Z. GS-YOLO: An improved plateau pika’s hole and bare patch detection algorithm based on YOLOv5s for UAV images. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).