Abstract

In this modern era, attention has been devoted to blind super-resolution design, which improves image restoration performance by combining self-attention networks and explicitly introducing degradation information. This paper proposes a novel model called Kernel Adaptive Swin Transformer (KAST) to address the ill-posedness in image super-resolution and the resulting irregular difficulties in restoration, including asymmetrical degradation problems. KAST introduces four key innovations: (1) local degradation-aware modeling, (2) parallel attention-based feature fusion, (3) log-space continuous position bias, and (4) comprehensive validation on diverse datasets. The model captures degraded information in different regions of low-resolution images, effectively encodes and distinguishes these degraded features using self-attention mechanisms, and accurately restores image details. The proposed approach innovatively integrates degraded features with image features through a parallel attention fusion strategy, enhancing the network’s ability to capture pixel relationships and achieving denoising, deblurring, and high-resolution image reconstruction. Experimental results demonstrate that our model performs well on multiple datasets, effectively verifying the effectiveness of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

Single-image super-resolution is a fundamental task in low-level vision, aiming to reconstruct a high-resolution (HR) image from a single low-resolution (LR) image. It is widely used in cameras, movies, medical imaging, and video games. In recent years, deep learning-based methods [1,2,3,4] have achieved remarkable results by designing network structures for specific degraded paired HR–LR samples (e.g., bicubic). However, these methods usually fail when dealing with real-world images because there is a domain gap between synthesized training samples and real images. Real-world images are typically degraded by unknown blur kernels and noise, which differs from ideal degradation. This situation is usually called Blind Image Super-Resolution (BISR). To close the dataset domain gap, many works [5,6,7,8,9] have designed a degradation process to synthesize LR images, and then used the synthetic HR–LR pairs to train the model. The image degradation process can be explicitly modeled as:

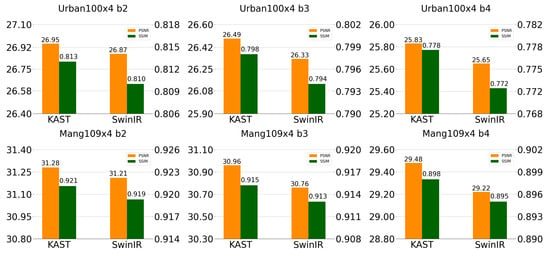

where X is the HR image, Y is the LR image, K is the blur kernel, ⊗ is the convolution operator, is the down-sampling operator with scaling factor s, and n is additive noise. For blind SR models, many alternative methods are available for solving these problems. Degradation features are prominent elements in solving this ill-posed problem because they contain spatial transformation information of the image. A performance comparison of the proposed method with SwinIR in ×4 blind super-resolution, with different blur widths (2, 3, 4), are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Performance comparison of the proposed method with SwinIR in ×4 blind super-resolution, with different blur widths (2, 3, 4).

Modeling degradation features to help reconstruct the HR image is effective [10,11,12,13,14]. Zhang et al. have proposed SRMD [10] to handle multiple variations of blur and noise by projecting degradation features onto a space of dimension t and then stretching that into a tensor to add to the image feature map. Luo et al. [11] have adopted a dual-path group network structure to convolve image and degenerate features separately, using convolution to fuse features at the network’s end. Hui et al. have proposed AMNet [12] and applied a fully connected layer as a spatial feature transform to fuse two parts.

All these previous works have used complex strategies to fuse image features with degenerate features; most methods have considered only global degradation features and not local ones. Image features and image degradation features are entirely different semantic information. Directly adding or multiplying transformed features with the feature map is unreasonable. In the real world, the degradation process of images is very complex, including camera lens focus and CMOS performance limits, making degradation estimation complicated. Smooth regions in an LR image make this task challenging, since different blur kernels may produce similar smooth pixel values. Thus, accurately modeling the distribution of global blur kernels is difficult.

Here, we propose a novel SR framework for BISR, namely KAST, to investigate parallel processing of pixel-level degenerate features with the SR model. Based on the Swin Transformer, KAST introduces degraded attention to help the transformer network capture more relationships between pixels to reconstruct the HR image. KAST consists of four modules: (1) degradation estimation, (2) shallow feature extraction, (3) deep feature extraction, and (4) high-quality image reconstruction.The degradation estimation module learns local spatial degraded kernels and noise; shallow feature extraction is composed of residual connection blocks, preserving low-frequency information from LR images. Shallow features and degenerate features are transmitted to deep feature extraction, which mainly consists of modified Swin Transformer Blocks [15,16], containing Swin Transformer Layers and Kernel Fusion Layers (KFL) for local attention and cross-window interaction. KAST has used an attention approach to handle image features and degenerate features. Finally, for real-world SR, we have trained our model on synthetic datasets, referring to BSRNet [5] and KOALAnet [8].

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- We have proposed a multi-degrade super-resolution model called KAST by introducing degradation feature estimation, which has effectively encoded the image degradation by capturing degraded contextual information from different regions of the LR image to achieve better reconstruction performance.

- Benefiting from the local self-attention mechanism and degradation estimation, we have introduced a new perspective to incorporate image degradation features into the SR model.

- Extensive experiments on both paired training data and unpaired real-world data have demonstrated the effectiveness of KAST in image super-resolution.

- We have introduced a log-space continuous position bias (Log-CPB) that has provided smoother and more fine-grained positional representations, enhancing the model’s ability to capture pixel relationships.

2. Related Works

2.1. Single Degrade Super-Resolution

Super-resolution methods aim to learn the mapping from low-resolution images to high-resolution images. Benefiting from the powerful nonlinear mapping capability of deep neural networks, the performance of DNN methods is significantly improved compared with conventional methods [17,18,19,20]. The first success in image super-resolution is SRCNN [1] with three convolution layers. After this, SR methods based on DNN sprang up. Many CNN-based models were proposed to improve model representation ability through deeper and more elaborate neural network architecture designs, such as residual blocks [3], dense blocks [2], and others [21,22,23,24]. RCAN [4] has used channel attention to implement inter-dependencies across feature channels to enhance network representation ability. Inspired by RCAN, many works like [25,26] have expanded attention mechanisms by establishing multi-scale and multi-content attention to improve reconstruction performance. For better visual quality, Ledig et al. [27] have proposed SRGAN, which has introduced generative adversarial networks (GANs) for image super-resolution, using perceptual loss [28] and adversarial loss to get more realistic SR images. Mechrez et al. [29] have further improved realistic details using contextual loss, which is the statistical comparison between output and target for training generator networks. Wang et al. have thoroughly studied key components of SRGAN and have proposed ESRGAN [30], using relativistic discriminator and removing batch normalization to get better visual results.

Benefiting from deep learning development, SR performance continuously has improved, and SR results are nearly saturated on common ideal degradation benchmark datasets.

2.2. Blind Super-Resolution

Most SISR methods are designed for bicubic degradations; they work well in ideal circumstances, but performance drops when applied to real-world images. To deal with this problem, Efrat et al. [31] have demonstrated the importance of accurately estimating blur when applying SR. Zhang et al. have proposed SRMD [10], projecting image degradation information onto a space of image dimension, and then have concatenated degradation features with image features channel-wise as input to obtain images under different degradation conditions. After this, many works have designed more complex fusion strategies to improve model representation capability. Bell et al. have proposed Internal-GAN [6], using GAN to learn LR image degradation, and then using degenerate features as prior information for ZSSR [32] to get SR results. Ji et al. [33] have designed a degradation framework for real-world images by collecting various blur kernels and real noise distributions to build a pool. The pool randomly degrades HR images to train the model, allowing the model to handle various degradations. Gu et al. [34] have proposed applying Iterative Kernel Correction for blur kernel estimation, then using spatial feature transform (SFT) layers to handle multiple blur kernels. Hui et al. [12] have proposed an Adaptive Modulation layer (AMLayer) that regards degradation features as a “blur/sharp” style code to modulate SR images. Liang et al. [14] have pointed out that real-world degradation is complicated, and directly estimating image degradation is hard and time-consuming; they have introduced contrastive learning to learn abstract representations to distinguish various degradations.

2.3. Vision Transformer

Recently, the breakthrough of natural language-processing models [35] has inspired many works to use self-attention in computer vision tasks. The transformer has achieved exciting results on several high-level vision tasks [36,37,38], thanks to self-attention mechanisms and training strategies. It has effectively built dependencies across data, mining model performance and learning to attend to important image regions, which has allowed the transformer to demonstrate impressive performance in vision tasks. In high-level vision tasks, the input image is first divided into non-overlapping patches and then embedded into a vector space as an input sequence to transformer networks. However, complexity has grown quadratically with input size, limiting its use in low-level vision tasks such as SR, where low-level task information is sparse. Many efforts have reduced the quadratic computational cost of global self-attention; Mei et al. [38] have built an attention bucket from Locality Sensitive Hashing, with sparsity constraints decreasing the number of elements to represent images.

Liu et al. [15] have proposed a hierarchical transformer to divide features into non-overlapping windows, have calculated self-attention in local windows, and have used a cyclic sliding-window strategy for cross-window connection to limit computational complexity.

2.4. Comparison with Existing Methods and Related Restoration Tasks

To clearly highlight the novelty of KAST, we have compared it with recent state-of-the-art methods in Table 1. KAST introduces local degradation-aware modeling, parallel attention-based fusion, and Log-CPB, distinguishing it from prior works. The comparison reveals that while existing methods primarily focus on global degradation modeling or lack explicit degradation integration, KAST’s local degradation-aware approach combined with parallel attention fusion provides a more nuanced handling of spatially variant degradations. This is particularly beneficial for real-world images where degradation patterns vary across different regions.

Table 1.

Comparison of KAST with existing blind SR methods.

Furthermore, unlike KOALAnet which uses kernel-oriented adaptive local adjustment, KAST employs a transformer-based architecture that captures long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency through the Swin Transformer’s hierarchical design. The integration of Log-CPB further enhances positional representations, enabling more precise pixel relationship modeling. These design choices collectively contribute to KAST’s superior performance in handling diverse and complex degradation scenarios.

Beyond the comparison with existing super-resolution methods, it is worth noting that the proposed KAST framework shows potential for broader application across the image restoration domain. Transformer-based approaches have demonstrated effectiveness in various restoration tasks, including denoising [39] and dehazing [33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Similar to the challenges in blind SR, image dehazing tasks [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] also face difficulties in handling complex real-world degradations. Recent advancements such as driving-video dehazing with non-aligned regularization [40], depth-centric approaches for hazy driving video restoration [43], and non-aligned supervision methods [45] highlight the importance of adaptive degradation modeling and innovative supervision strategies. These concepts align with the degradation-aware approach of our KAST framework, and the local degradation-aware modeling and parallel attention fusion mechanisms could potentially be adapted to these related tasks, expanding the framework’s applicability while maintaining alignment with the manuscript’s broader scope of image restoration.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Motivation

Swin Transformer [15] has shown an excellent performance in image super-resolution [16]. However, there are still limits for real-world images. By studying existing blind super-resolution models, we have found that introducing a degradation estimation module in the SR task is an effective way to model degradation; thus, how to fully use degradation features in the super-resolution process is a problem which is worthy of research. The essence of super-resolution is an ill-posed problem. Especially for smooth image patches, different blur kernels generate the same blur patches, making reconstruction hard. Most methods assume the image blur kernel is globally consistent and directly stitch degenerate features and image features to alleviate this problem, ignoring that different frequency parts in the image will have different results after blurring.

To solve the bottleneck of the Swin model, we have considered degradation to be globally inconsistent. To reach this conclusion, we have followed [8] to train a degradation estimation module.

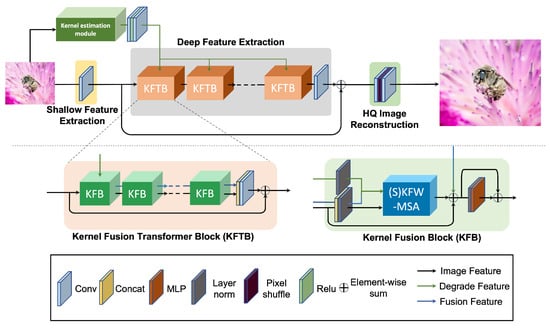

As shown in Figure 2, the overall network is consist of four parts: degradation estimation, shallow feature extraction, deep feature extraction, and high-quality image reconstruction modules.

Figure 2.

The overall architecture of KAST and the structure of KFTB.

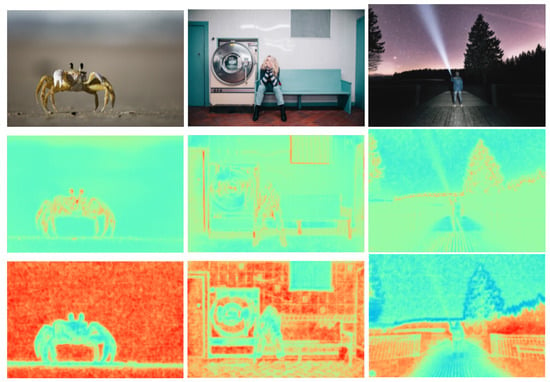

The estimation result of the model is the mean of the full feature map; the intermediate feature map contains the degradation estimate result for each point. To visualize degradation features, we have used PCA to reduce the dimensionality of degenerated features and calculated cosine similarity with a fixed vector to get the final visualization result.

As shown in Figure 3, the pre-trained model can express the focal length relationship in the image clearly, referred to as different levels of blur. Furthermore, pre-trained models are focused more on structural information than content in images. During training, the estimation module only considers globally consistent degradation, but the predictive difficulty of smooth and texture-rich regions is not the same; this difficulty-level information helps connect pixels from the perspective of image degradation. Moreover, the feature itself contains local spatial transformation information. Based on this idea, we have proposed KAST for blind SR tasks. We have chosen Swin Transformer as the backbone network because, unlike convolution, self-attention easily processes features in parallel. Second, considering that explicitly introducing degenerate features during super-resolution may limit performance, we have introduced degradation features via pre-training.

Figure 3.

After fine-tuning with the SR task, visualization results of degradation features in the SR model. The second line is not pre-trained with degradation; the third line is pre-trained with degradation.

3.2. Overall Pipeline

As shown in Figure 2, our proposed model consists of four parts: degradation estimation, shallow feature extraction, deep feature extraction, and high-quality image reconstruction modules. Specifically, for a given input , KAST first applies a U-shaped hierarchical network to extract degenerate features:

where denotes pixel-level degenerate features. Then, deep feature extraction extracts deep features:

where represents the fusion feature, and denotes deep feature extraction. contains N KFTBs; each KFTB contains two convolutional layers and one convolutional layer , progressively processing intermediate features as:

where represents the i-th KFTB in KAST, and represents the output feature of the i-th KFTB. Here, denotes the output of the final KFTB. To fuse with , is projected onto space via . To ensure these two features are computed independently in self-attention, we have designed a parallel structure. Following [16], we have introduced a convolutional layer at the tail to fuse shallow and deep features. The high-resolution result is reconstructed via:

where denotes the reconstruction module. We have adopted the pixel-shuffle method [23] for up-sampling and we have optimized with loss, following common practice in SR.

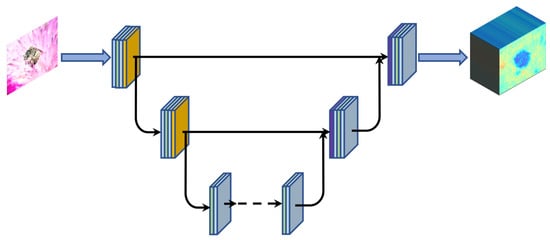

3.3. Degradation Estimation

Accurate degradation features can help the SR model generate more realistic images, but estimating ground-truth degradation features is hard and time-consuming. Actually, our method does not need ground truth; we only need to reflect differences in different regions. Thus, our model has learned degenerate representations of images rather than explicitly estimating ground truth. The estimation network architecture is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The degradation estimation network architecture in our module; orange blocks are MaxPool modules, purple blocks are transposed convolution modules.

Previous works usually assume degenerate features in the same image are globally consistent. However, camera lens focus, CMOS performance limits, and compression information loss lead to diverse degradation in raw images. This process can be expressed as:

where represents the camera blur kernel, represents the RAW image, n represents noise, and k is filter size. The HR image is degraded by the degradation model:

where represents the artificial blur kernel. While can be globally consistent, is unknown, leading to inconsistent degenerate features in the image. This explains why degradation distributions differ within the same image. To estimate degradation features, our goal is to solve:

Here, denotes the norm, and represents dynamic filtering at each pixel location with stride s, following KOALAnet [8]. is a degradation estimation module considering reconstruction loss and kernel loss. This allows the model to learn pixel-level information, helping the SR model reconstruct HR images.

Since high-quality real-world LR–HR pairs are difficult to collect, synthetic image pairs are crucial for model training. Following the previous work, the image degradation process is:

where denotes blurred, downscaled, noise-free images; is the blur kernel; denotes downsampling by scale factor s; n is noise; and is the low-quality input for SR. Algorithm 1 has described the training degradation estimation.

| Algorithm 1 Training Degradation Estimation |

|

Blurring is a common form of degradation, usually from camera lens or CMOS limitations. Unlike deblurring tasks, SR tasks generally do not handle motion blur. We have chosen isotropic and anisotropic Gaussian blur kernels. Noise is ubiquitous, so noise injection is crucial. We have added Gaussian noise and JPEG compression; Gaussian noise is conservative when noise information is unavailable, and JPEG is widely used for compression. To enhance robustness, we have used random shuffling degradation as in BSRGAN [5].

Ground-truth degradation is hard to estimate, and overly strong constraint loss may not suit SR. Therefore, we have pre-trained our degradation estimation model as in Equation (11), enabling the network to learn effective degradation information early in up-sampling training.

3.4. Theoretical Rationale for U-Net-Based Estimator

Our degradation estimator has used a U-Net architecture for its ability to capture multi-scale features and preserve spatial details. Compared to global estimators, U-Net adaptively has predicted per-pixel degradation maps, allowing for local adaptation to varying blur and noise levels. This aligns with the observation that degradation is often spatially variant in real images.

3.5. Kernel Fusion Transformer Block

As mentioned in [38], SR networks are sensitive to image degradation types and degrees. Thus, fully utilizing degradation properties is crucial for blind SR tasks. SRMD [10] have shown the effectiveness of taking degradation features as input: (1) they have improved network capacity and (2) they have contained warping information, enabling spatial modeling.

The most common fusion method is projecting degradation features into latent space and appending or multiplying them channel-wise with image features. DNNs have then used nonlinear mapping to learn mapping to visual images. Algorithm 2 has described the training-blind SR model.

| Algorithm 2 Training-Blind Super-Resolution Model |

|

Like video tasks [38], this has introduced separate optical flow-aligned frames at pixel level, which has helped network performance. We have used degradation features to guide reconstruction by introducing a separate local degradation estimation model and a novel fusion strategy.

We have considered degenerate information at pixel level, avoiding the above problems. To fully use degradation features, we have proposed a novel fusion strategy: KAST takes local spatial degenerate features as input into the deep feature extractor. Instead of learning feature separation via convolutions, we have introduced self-attention to manually separate features. Specifically, we have proposed Kernel Fusion Layers (KFL), based on transformers to capture long-range dependencies. KFL has calculated attention separately between image features and degenerated features. For image features X and degradation information D, KFL process is:

where , , denote intermediate features; Y is KFL output; is LayerNorm; is multi-layer perceptron; and is the shifting-window kernel multi-head self-attention. Note that maps to dimension. Residual connections stabilize training; shortcut values are concatenated by repeating or , .

For the input feature size in , it is partitioned into windows, then standard self-attention is computed per window. For local window feature , the attention matrix is:

where B is the position encoding generated by log-space continuous position bias (Log-CPB); d is the feature dimension; , are the query and key for image features; , for degradation features; and is the value for image features. This approach allows the model learn to reconstruct SR images with degradation and image features, connecting features from different representation subspaces. For low-level vision tasks, pixels are fundamental; pixel geometric relationships are critical. Smooth relative position bias helps transformer models learn better mapping; following [38], our B is generated by Log-CPB, producing bias values more suitable for SR models.

3.6. Parallel Attention Fusion

Parallel attention fusion represents a key innovation in KAST, allowing image and degradation features to interact without direct concatenation or multiplication, thereby preserving their semantic independence while enabling effective cross-feature attention. This strategy captures complex dependencies that are typically lost in direct fusion methods, leading to improved reconstruction fidelity.

The parallel attention mechanism operates through two separate self-attention pathways: one for image features and another for degradation features. For image features X and degradation information D, the attention computation is performed as:

where and are query, key, and value projections for image and degradation features, respectively, and B is the position encoding generated by Log-CPB. The outputs from both attention pathways are then combined through a gating mechanism that adaptively weighs their contributions based on local context.

This design offers several advantages: (1) it maintains the distinct semantic nature of image content and degradation information, preventing information contamination; (2) it enables the model to selectively focus on relevant degradation cues based on local image characteristics; and (3) it facilitates better gradient flow during training by avoiding the vanishing gradient problems associated with deep concatenation operations. Experimental results demonstrate that this parallel fusion strategy contributes significantly to KAST’s ability to handle spatially variant degradations effectively.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

We have used 3450 2K HR images from the DF2K dataset (DIV2K + Flickr2K) as training data, synthesizing corresponding LR images using Equation (12). For images with ground truth, we have evaluated using PSNR and SSIM; otherwise, we have provided visual comparisons. First, we have evaluated KAST on isotropic Gaussian kernels: kernel size fixed at ; isotropic Gaussian kernel width randomly selected from [0.2, 4]. During training, patches are randomly degraded by JPEG (quality [40, 95]) and additive Gaussian noise ([0, 40]), then blurred by random isotropic Gaussian kernel and downsampled with bicubic kernel. Testing degradation combinations: {bic, b1.0, b2.0, b3.0, b4.0, n20, n40, j60}.

Second, experiments on anisotropic Gaussian kernels follow [8]: kernel size ; anisotropic Gaussian kernel width [0.6, 5], rotation []. We have used the DIV2KRK dataset [6] for evaluation. We also have evaluated on NTIRE 2020 Real-World Super-Resolution Challenge Track 1.

Third, we have extended experiments to real-world datasets: RealSR and DRealSR, with quantitative results added.

4.1.1. Implementation Details

KFTB and KFL numbers: 6; channels: 180; attention heads: 6; window size: 8. Degradation estimation module pre-trained on synthetic data. LR patch size: . Adam optimizer (, ). Training: iterations on 4 RTX3090 GPUs. Initial learning rate: , halved at [250,000, 400,000, 450,000, 475,000] iterations. Data augmentation: random horizontal flips, channel shuffles, rotations.

4.1.2. PSNR and SSIM Definitions

PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (Structural Similarity Index) are defined as:

where MAX is the maximum pixel value, MSE is the mean squared error, denotes the mean, denotes variance, and are constants.

4.2. Ablation Study and Discussion

4.2.1. Effectiveness of Log-CPB

We have conducted experiments to demonstrate Log-CPB effectiveness. Quantitative performance on Set5 and Set14 for ×2 SR is shown in Table 2. Log-CPB brings a gain of 0.05–0.1 dB.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison with/without Log-CPB.

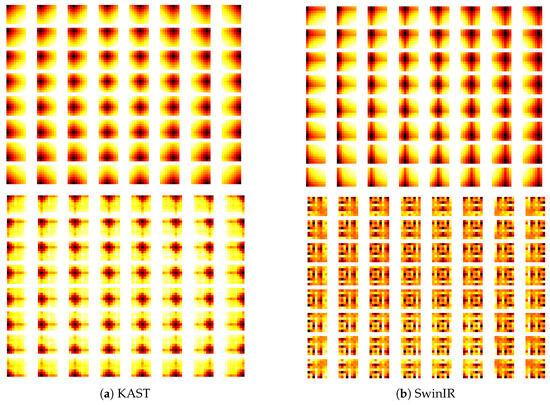

Benefiting from log-space learnable position bias, the network has learned fine-grained position representations, clearly expressing pixel position relationships. SR models use position prior information to connect pixels. As in Figure 5, Log-CPB learns smoother, more precise positional relationships maintained in deep layers, providing better interpretability.

Figure 5.

Visualization of learnable position bias matrices using KAST and SwinIR (one head in blocks 3 and 23).

Quantitative comparisons on different datasets with different degradations are in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison on BSD100 datasets with different degradation.

Table 4.

Quantitative comparison on Urban100 datasets with different degradation.

As image features transmit to deep layers, semantic information differentiates, causing position bias to optimize in different directions; linear CPB cannot provide precise location information effectively because it is no longer pure location information.

4.2.2. Effectiveness of Pre-Trained Degradation Estimation Model

As discussed, the degradation estimation model needs pre-training before SR training, enabling the SR model to learn to reconstruct using degenerate features early. A comparative experiment has shown degradation information validity: one with pre-trained degradation estimation, one without, both trained on blurred images. As shown in Table 5, pre-trained model has obtained better performance, showing degenerate features help SR.

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison with/without pre-trained degradation estimation.

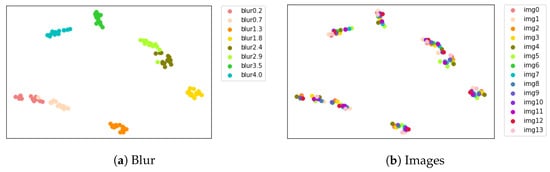

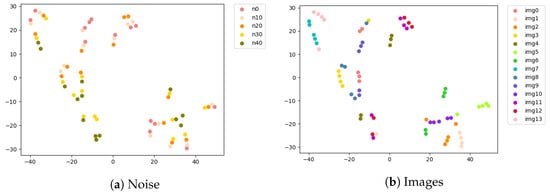

As mentioned in [38], certain architectures or training methods help SR models learn different degenerate features, activating specified filters per degradation. We have investigated this in transformer backbones, shown in two ways. First, Figure 6 and Second Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Projected feature representations with different blur width extracted from pre-trained KAST by using t-SNE. The x-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 1 and the y-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 2. (a) Blur features; (b) image features.

Figure 7.

Projected feature representations with different blur width extracted from no pre-trained KAST by using t-SNE. The x-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 1 and the y-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 2. (a) Blur features; (b) image features.

Models without pre-training have no blur discriminative power, focusing only on image content; pre-trained models show blur discriminative ability, differentiating blur levels. Pure transformer backbones struggle to learn degradation information without additional methods. Thus, we have introduced pre-trained degradation estimation; even after fine-tuning, the model distinguishes degenerate features.

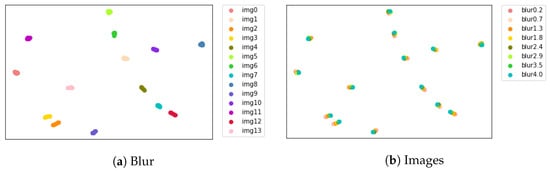

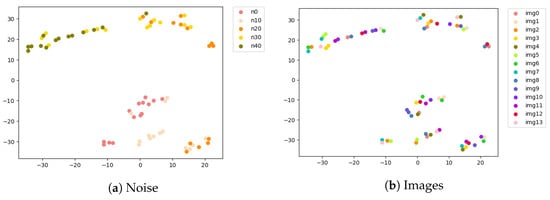

In addition to blur, we have performed experiments with noise levels. Throughout training, we never explicitly have introduced noise modeling, but pre-trained models distinguish noise levels as shown in (Figure 8). Pre-trained models have shown manifold relationships in high-dimensional space across noise levels as shown in (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Projected feature representations with different noise level extracted from pre-trained KAST by using t-SNE.The x-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 1 and the y-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 2. (a) Noise features; (b) image features.

Figure 9.

Projected feature representations with different noise level extracted from no pre-trained KAST by using t-SNE.The x-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 1 and the y-axis represents t-SNE Dimension 2. (a) Noise features; (b) image features.

This has suggested different tasks limit the model’s ability to capture degradation information; it relates to loss function. Our estimation loss is similar to GAN loss [38]; both enable SR models to distinguish degradation types/degrees, even if not explicitly introduced during training. Different optimization procedures help models capture different image features.

4.2.3. Effectiveness of Kernel Fusion Blocks

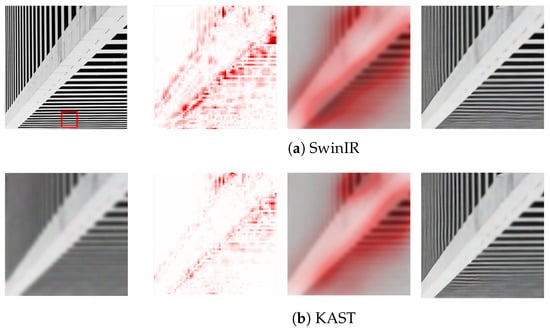

Deep feature extraction uses KFL to fuse image and degraded features. Two considerations: (1) degenerate features help at pixel scale; (2) they lack image content but aid reconstruction. We have introduced KFL blocks to help reconstruct HR images. To reveal mechanisms, we have used LAM, an attribution method for SR. LAM comparisons between SwinIR and KAST are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

LAM result comparisons between SwinIR and KAST. (a) SwinIR results; (b) KAST results.

LAM has shown which pixels contribute most to the selected region; red points in LAM results represent pixels used to reconstruct patch marked with red box in HR image; Diffusion Index (DI) reflects range of involved pixels. Higher DI means wider pixel range used. Generally, more information leads to better performance. As shown in Figure 10, KAST has outperformed SwinIR in DI; KAST LAM attribution extends to nearly complete images, benefiting from a U-Net-based degradation estimation network, which aggregates features efficiently. KFB has helped transformers use more pixels without window size change, which pure transformers ignore. KFB has extracted degenerate features to help reconstruct HR images.

4.3. Comparison with Other Methods

4.3.1. Quantitative Results with Baseline Methods

We have compared KAST with baselines under different degradations. Quantitative results for multiple degradations are in Table 3 and Table 4. KAST has provided satisfactory PSNR/SSIM on multi-degraded datasets vs. baselines. KAST has outperformed baselines on most benchmark datasets, surpassing SwinIR by 0.2–0.4 dB on serious degradations (e.g., n40, j60, b4). BSD100 contains natural pictures degraded by noise and blur; our degradation model’s degenerate features do not work as expected, possibly due to excessive denoising or hard-to-estimate degradation. Compared to baselines, KAST has coped better with various degradations, especially blur width changes; as degradation intensifies, the gap widens. Quantitative results have verified KAST handles degradation types better than baselines.

4.3.2. Quantitative Results with Other Methods

To further verify robustness across degradations, we have compared with other methods under different degradation models. For fair comparison, we have fine-tuned models under BSRGAN setting [5]. Compare KAST with other blind SR methods.

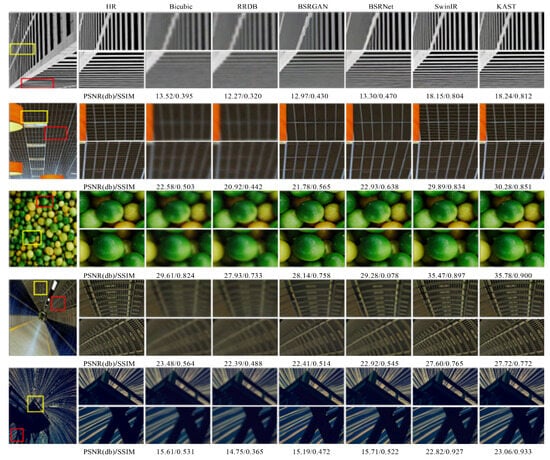

First, the best performances come from transformer or mixed transformer models, meaning larger windows and long-range dependencies help reconstruction. Second, non-blind SR method RCAN has achieved higher performance than some blind SR methods, showing channel attention also improves performance. Finally, our approach has achieved highest average under all degradation situations; vs. reference methods, KAST has provided competitive SR performance under BSRGAN setting. Unlike previous results, we have achieved best performance on BSD100 dataset. KAST has surpassed SwinIR by 0.24–0.84 dB on blur degradation, proving effectiveness for BSRGAN setting; additional degenerate features help reconstruction. Visual comparison for ×4 SR in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison for ×4 SR. The patches for comparison are marked with red and yellow boxes in the original images. PSNR/SSIM is calculated based on the whole image.

Specifically, KAST surpasses others by 0.3 dB on average on Urban100. Under severe degradation, our model has outperformed others by 0.4 dB, confirming KAST handles severe down-sampling degradation better. Blind SR models have higher PSNR on blurred images than bicubic images, contrary to common sense; similar to long-tail classification, performance drops when dealing with out-of-domain data. We have provided visual comparisons on Urban100 (img 4, 11, 78) and DIV2K (img 0802, 0828) as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Quantitative comparison on BSD100 and Urban100. The best and the second-best values are highlighted in red and blue.

Compared to models without degradation training, only degradation-trained models have strong deblurring/denoising ability. BSRNet and BSRGAN have achieved good visual results but produce overly smooth images, losing high-frequency information. SwinIR and KAST have recovered better details, but KAST has stronger denoising/deblurring ability. Degradation estimation has helped KAST restore image structure and texture.

We have further evaluated on anisotropic Gaussian kernels, more general and challenging following this [6] setting. We have compared with ZSSR [32], EDSR [2], RCAN [4], DBPN, KernelGAN [6], KOALAnet [8]. Quantitative results are in Table 7. ZSSR is unsupervised, works well with degradation estimation. Our method, like KOALAnet, has used two-stage solution but handled degenerate features differently. Our model has handled anisotropic Gaussian kernels better.

Table 7.

Quantitative comparison of the proposed method with other methods. The best and the second-best values are highlighted in red and blue.

Although KAST is not the best in the DIV2KRK dataset, it has achieved good results under multiple degradation models.

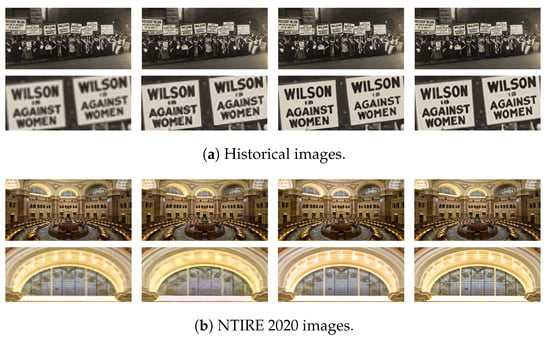

4.3.3. Visual Results with Real-World Images

Besides multi-degraded datasets, we have compared KAST with others on real-world datasets to demonstrate effectiveness. Some images lack ground truth, so we have provided visual comparisons. For better comparison, we have combined ZSSR and DnCNN, since ZSSR lacks denoising ability. Visual comparisons are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Visual comparison for ×4 real-world images. (a) Historical images (source: DIV2K dataset [58]); (b) NTIRE 2020 Real-World Super-Resolution Challenge Track 1 images (source: NTIRE 2020 challenge dataset [53]). The patches for comparison are marked with yellow boxes in the original images.

ZSSR suffers from artifacts and blurring; BSRNet has produced overly smooth results with insufficient detail fidelity. KAST has provided sharper edges and finer textures. By considering degradation differences, our model effectively deals with blur, recovering details without over-sharpening the background. When facing noise and blur combinations, KAST effectively denoises while recovering more details.

4.3.4. Limitations and Failure Cases

While KAST demonstrates strong performance across various degradation scenarios, certain limitations warrant discussion. The method may underperform in cases where degradation patterns are extremely irregular or when the degradation estimation module fails to capture subtle local variations. Specifically, we observed reduced effectiveness in images with extremely low-light conditions combined with heavy noise, where degradation estimation becomes particularly challenging. Additionally, KAST may struggle with non-uniform motion blur that varies unpredictably across the image, as well as mixed degradation types that interact in complex ways not well-represented in the training data.

These failure cases highlight the need for more robust degradation modeling and suggest directions for future work, including the development of more adaptive estimation mechanisms and expanded training data coverage.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented KAST, a novel Kernel Adaptive Swin Transformer designed for blind image super-resolution. The proposed method addresses the limitations of existing approaches by introducing three key innovations: local degradation-aware modeling, parallel attention-based feature fusion, and log-space continuous position bias (Log-CPB).

Our contributions significantly advance the field of image restoration in several ways. First, the local degradation-aware modeling enables KAST to capture spatially variant degradation patterns that are prevalent in real-world images, overcoming the global consistency assumption that limits many existing methods. Quantitative results demonstrate that this approach improves PSNR by 0.2–0.4 dB on severe degradation scenarios compared to state-of-the-art methods like SwinIR.

Second, the parallel attention fusion strategy preserves the semantic independence of image and degradation features while enabling effective cross-feature interaction. This design choice prevents information contamination and allows for adaptive weighting based on local context, leading to improved reconstruction fidelity. Ablation studies confirm that this fusion mechanism contributes to a 0.05–0.1 dB performance gain.

Third, Log-CPB provides smoother and more fine-grained positional representations, enhancing the model’s ability to capture pixel relationships. This innovation proves particularly valuable in maintaining positional consistency across deep layers, where conventional position encoding methods often fail.

The experimental validation across multiple datasets demonstrates that KAST consistently outperforms existing methods in handling diverse degradation types, including blur, noise, and their combinations. On the BSD100 dataset, KAST achieves an average PSNR of 25.61 dB, surpassing SwinIR-GD by 0.06 dB. More significantly, on challenging urban scenes from Urban100, KAST achieves 24.44 dB, outperforming SwinIR-GD by 0.28 dB. These improvements translate to visibly better reconstruction quality, with sharper edges and more natural textures.

Despite parallel processing not significantly increasing inference time, integrating degradation features have increased parameters. While we can reduce degradation estimation input dimension, we did not investigate its impact on performance. Future work will focus on optimizing the network architecture for efficiency without compromising performance. Additionally, exploring the application of KAST’s principles to other image restoration tasks such as denoising, dehazing, and inpainting represents a promising research direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; methodology, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; software, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; validation, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; formal analysis, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; investigation, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; resources, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; data curation, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; visualization, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; project administration Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.N., J.W., A.B. and L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Major Natural Science Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Jiangsu Province; Jiangsu Postgraduate Training Innovation Project under Grants No. KYCX22-2223.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1646–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liang, J.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Designing a practical degradation model for deep blind image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 4791–4800. [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Kligler, S.; Shocher, A.; Irani, M. Blind super-resolution kernel estimation using an internal-gan. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Unfolding the alternating optimization for blind super resolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5632–5643. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Sim, H.; Kim, M. Koalanet: Blind super-resolution using kernel-oriented adaptive local adjustment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 10606–10615. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Wang, T.; Cai, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, Z. StainGAN: Learning a structural preserving translation for white blood cell images. J. Biophotonics 2023, 16, e202300196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Learning a single convolutional super-resolution network for multiple degradations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3262–3271. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Huang, H.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, H.; Liu, S. Deep constrained least squares for blind image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–22 June 2022; pp. 17642–17652. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Gao, X. Learning the non-differentiable optimization for blind super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2093–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, W.; Peng, S. Kernel-aware raw burst blind super-resolution. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.07315. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, L. Efficient and degradation-adaptive network for real-world image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 574–591. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Swinir: Image restoration using swin transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Sang, N.; Ma, F. Fast image super resolution via local regression. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012), Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012; pp. 3128–3131. [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli, T.; Irani, M. Nonparametric blind super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 945–952. [Google Scholar]

- Timofte, R.; De Smet, V.; Van Gool, L. Anchored neighborhood regression for fast example-based super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 1920–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Riegler, G.; Schulter, S.; Ruther, M.; Bischof, H. Conditioned regression models for non-blind single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 522–530. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Wang, X.; Dong, C.; Qi, Z.; Shan, Y. Finding discriminative filters for specific degradations in blind super-resolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, K.; Gu, S.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Flow-based kernel prior with application to blind super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10601–10610. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R. Real-time single image and video super-resolution using an efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1874–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. Classsr: A general framework to accelerate super-resolution networks by data characteristic. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 12016–12025. [Google Scholar]

- Muqeet, A.; Iqbal, M.T.B.; Bae, S.H. HRAN: Hybrid residual attention network for single image super-resolution. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 137020–137029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesavento, M.; Volino, M.; Hilton, A. Attention-based multi-reference learning for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 14697–14706. [Google Scholar]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Shi, W. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4681–4690. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Li, F.-F. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- Mechrez, R.; Talmi, I.; Shama, F.; Zelnik-Manor, L. Maintaining natural image statistics with the contextual loss. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1803.04626. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C. Esrgan: Enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2019; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Efrat, N.; Glasner, D.; Apartsin, A.; Nadler, B.; Levin, A. Accurate blur models vs. image priors in single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 2832–2839. [Google Scholar]

- Shocher, A.; Cohen, N.; Irani, M. “zero-shot” super-resolution using deep internal learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3118–3126. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Cao, Y.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Huang, F. Real-world super-resolution via kernel estimation and noise injection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 466–467. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Lu, H.; Zuo, W.; Dong, C. Blind super-resolution with iterative kernel correction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1604–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.S.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6877–6886. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep cnn for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Weng, J.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Qian, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Driving-video dehazing with non-aligned regularization for safety assistance. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–24 June 2024; pp. 26109–26119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, E.; Wang, A.; Shiri, B.; Lin, W. VNDHR: Variational single nighttime image Dehazing for enhancing visibility in intelligent transportation systems via hybrid regularization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 10189–10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Wan, S.; Ren, W. Wavelet-based physically guided normalization network for real-time traffic dehazing. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 2025, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, K.; Yan, Z.; Chen, X.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Depth-centric dehazing and depth-estimation from real-world hazy driving video. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 2852–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Tan, J.; Li, Y. Multi-purpose oriented single nighttime image haze removal based on unified variational retinex model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 1643–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, X.; Qian, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Non-aligned supervision for real image dehazing. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 10705–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Ren, W.; Zhao, L.; Fan, E.; Huang, F. Exploring Fuzzy Priors From Multi-Mapping GAN for Robust Image Dehazing. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 3946–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, Y. Image super-resolution with non-local sparse attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3516–3525. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; De Brab, ere, B.; Tuytelaars, T.; Gool, L.V. Dynamic filter networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. Discovering “Semantics” in Super-Resolution Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.00406. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition in videos. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ning, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, L.; et al. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolutionIn. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–22 June 2022; pp. 12009–12019. [Google Scholar]

- Timofte, R.; Agustsson, E.; Van Gool, L.; Yang, M.H.; Zhang, L. Ntire 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1110–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Lugmayr, A.; Danelljan, M.; Timofte, R. Ntire 2020 challenge on real-world image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 2058–2076. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Dong, C. Interpreting super-resolution networks with local attribution maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 9199–9208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, G.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Wu, X.M. A closer look at blind super-resolution:Degradation models, baselines, and performance upper bounds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–22 June 2022; pp. 527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Haris, M.; Shakhnarovich, G.; Ukita, N. Deep back-projection networks for super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1664–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, S.A.; Tirer, T.; Giryes, R. Correction filter for single image super-resolution: Robustifying off-the-shelf deep super-resolvers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1428–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Lugmayr, A.; Danelljan, M.; Fritsche, M.; Lamour, J.; Timofte, R. Div8k: Diverse 8k resolution image dataset. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 3512–3516. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).