Abstract

We introduce the Symmetric- (Sy-) family, a unified class of symmetric discrete distributions on the integers obtained by multiplying a three-point symmetric sign variable by an independent non-negative integer-valued magnitude. This sign-magnitude construction yields interpretable, zero-centered models with tunable mass at zero and dispersion balanced across signs, making them suitable for outcomes, such as differences of counts or discretized return increments. We derive general distributional properties, including closed-form expressions for the probability mass and cumulative distribution functions, bilateral generating functions, and even moments, and show that the tail behavior is inherited from the magnitude component. A characterization by symmetry and sign–magnitude independence is established and a distinctive operational feature is proved: for independent members of the family, the sum and the difference have the same distribution. As a central example, we study the symmetric Poisson model, providing measures of skewness, kurtosis, and entropy, together with estimation via the method of moments and maximum likelihood. Simulation studies assess finite-sample performance of the estimators, and applications to datasets from finance and education show improved goodness-of-fit relative to established integer-valued competitors. Overall, the Sy- framework offers a mathematically tractable and interpretable basis for modeling symmetric integer-valued outcomes across diverse domains.

1. Introduction

Many discrete datasets encountered in practice take values on the non-negative integers that are routinely modeled using standard families, such as the Poisson or geometric distributions. In contrast, there are important situations where the natural support is the whole set of integers , most notably when observations are signed differences of counts or other zero-centered measurements. Canonical examples include score differences in sports, day-to-day changes in transaction counts or sales, inter-rater differences in clinical tallies, and discretized (symmetric) return increments in finance. For such problems, modeling directly on with distributions that respect symmetry around zero is both natural and desirable.

Several integer-valued distributions on have been proposed. Prominent instances include the Skellam distribution [1], obtained as the difference of two independent Poisson variables; the discrete Laplace distribution [2], along with related skew/asymmetric variants [3,4]; the discrete normal distribution [5]; and, recently, perturbed Laplace–type models [6]. Applications of signed count differences appear in medical and reliability studies [7,8] and in sports analytics, such as goal differences [9]. For general background on count modeling and discrete distributions, see refs. [10,11]. In addition, substantial probability mass at zero frequently arises in practice, creating links with the zero-inflated literature [12].

Beyond these classical constructions, there has been a notable increase in recent work on flexible integer-valued distributions supported on , including several models explicitly designed to capture symmetry and tunable dispersion. For example, ref. [13] introduced the discrete skew logistic distribution, which can accommodate symmetric and asymmetric count data and provides a useful reference for tail-shape control. Two recent contributions by refs. [14,15] developed new symmetric and perturbation-based distributions on the integers, with applications to stock exchange and hydrological data. In parallel, ref. [6] proposed a general perturbation of the discrete Laplace distribution, demonstrating improvements in financial and health datasets. More broadly, ref. [16] reviewed Skellam-type models and related integer-supported families, while ref. [17] provided an up-to-date survey on models for integer-valued data, highlighting the importance of distributions supported on in modern applications. These recent works underscore the need for simple, interpretable, and analytically tractable symmetric models on , a gap that the present Sy- family aims to fill. These recent developments further motivate the need for a symmetric decomposition-based model with explicit identifiability and analytical tractability, such as the Sy- and Sy- formulations proposed in this work.

This paper introduces a unified and tractable framework for symmetric integer-valued data on , named the Sy- family. The construction separates a three-point symmetric sign component from a non-negative magnitude: a data-generating sign takes values in with a tunable mass at zero and is multiplied by an independent, non-negative integer-valued variable. This sign–magnitude representation yields zero-centered, exactly symmetric models with interpretable control of the atom at zero while allowing the analyst to inherit tail behavior, dispersion, and computational convenience from the chosen baseline magnitude distribution.

We develop a coherent set of distributional results for the family: closed-form probability mass functions and cumulative distribution functions, bilateral probability generating functions, and moment identities. Symmetry implies vanishing odd moments, whereas even moments factor through the baseline magnitude. We also establish a characterization by symmetry and independence: an integer-valued distribution belongs to the proposed family if and only if it is symmetric and its sign is independent of the magnitude with a three-point symmetric distribution. Beyond these foundations, we study general consequences of the product structure, including tail transfer from the magnitude, conditions for unimodality or bimodality, and simple obstructions to infinite divisibility.

A distinctive feature of this framework is a strong symmetry property for operations on independent variables, where for two independent members of the family, the sum and the difference have the same distribution. This identity is a direct consequence of the bilateral generating function symmetry and does not generally hold for standard two-sided competitors, such as Skellam [1], discrete Laplace [2], perturbed Laplace [6], or extended Poisson models [18].

As a central example, we particularize the family with a Poisson magnitude, thereby obtaining the symmetric Poisson model. We derive distributional formulas (including entropy), discuss the induced zero mass in relation to zero-inflated counts [12], and develop estimation via the method of moments and maximum likelihood. Simulation studies assess finite-sample behavior, and applications to datasets from finance and education illustrate a competitive or improved fit relative to established alternatives supported on .

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the Sy- family, detailing the construction from a symmetric modified Bernoulli sign and an independent non-negative magnitude. Section 3 develops core distributional results for the family, including closed-form probability mass function (PMF) and cumulative distribution function (CDF) identities, bilateral generating functions, characterization by symmetry and sign–magnitude independence, tail transfer from the magnitude, modality conditions, criteria precluding infinite divisibility, the quantile function, and the median, as well as a discussion of first-order stochastic dominance for . Section 4 specializes in the Sy–Poisson model, deriving the moment generating function (MGF) and probability generating function (PGF), closed-form even moments (via Touchard polynomials), skewness, kurtosis, and Shannon entropy. Section 5 presents inference for Sy–Poisson: method-of-moments estimation (with asymptotic variance via the delta method), likelihood-based estimation, and both observed and expected Fisher information. Section 6 reports a simulation study evaluating the finite-sample bias and mean squared error of the maximum likelihood estimators. Section 7 provides two empirical applications (finance and education) comparing Sy–Poisson with established competitors on . A concluding section summarizes implications and outlines directions for future research.

2. The Sy- Family: Construction and Basic Setup

A key building block of the Sy- family is a three-point symmetric distribution on that combines a random sign with a controllable mass at zero. This distribution will serve as the canonical sign mechanism in our sign–magnitude representation of Z. We refer to it as the symmetric modified Bernoulli distribution.

Definition 1.

Let . A discrete random variable X is said to follow the symmetric modified Bernoulli distribution with parameter θ, denoted , if its PMF is

Proposition 1.

Let and be independent random variables. Define

Then with support and .

Proof.

Write , so and , where ⊥ denotes independence between random variables. Then, we obtain

which matches the symmetric modified Bernoulli distribution with parameter . □

To facilitate simulation and highlight the structural symmetry of , we present it in Appendix A two equivalent stochastic constructions for generating . These representations are convenient for both algorithmic sampling and concise derivations of basic properties.

2.1. Stochastic Representation

Definition 2.

Let be as defined in Definition 1, and let Y be a discrete random variable with support . Assume X and Y are independent. We say that a discrete random variable Z belongs to the Sy- family if it admits the stochastic representation

Proposition 2.

Let with , let Y be an independent -valued random variable, and set . Then:

- (i)

- Moments of X. For every odd integer r, . For every even integer , . In particular, , , and .

- (ii)

- Moments of . If , then for all , , and for all ,In particular, and .

Proof.

For , , and . Hence for , which is 0 for odd r and for even r; the variance follows since and . For with , we have whenever the moments exist; the claims for odd and even powers follow by substituting the moments of X obtained above. □

2.2. Characterization by Symmetry and Independence

We show that the Sy- family is exactly the class of symmetric integer-valued distributions for which the sign is independent of the magnitude and is represented by the symmetric modified Bernoulli distribution.

Theorem 1.

Let Z be an integer-valued random variable with . The following statements are equivalent:

- (i)

- Z belongs to the Sy- family; that is, there exist with and an independent such that .

- (ii)

- Z is symmetric about zero, i.e., for all , and there exist random variables S and W such that for some , , S, and W are independent, and .

Proof.

(i) ⇒ (ii). Suppose with , , and independent of X. Then Z is symmetric because

Set and . By construction, , , , and . Thus (ii) holds. (ii) ⇒ (i). Conversely, suppose (ii) holds. Take and . Then , , and , with . Hence Z belongs to the Sy- family, so (i) holds. □

Remark 1.

Theorem 1 establishes that Definition 2 is not merely a constructive scheme but a complete characterization of the class: symmetry, together with sign–magnitude independence and a three-point symmetric sign distribution, is equivalent to membership in Sy-. This validates the use of (Definition 1) as the canonical mechanism for the sign component.

Further analytical properties of the Sy- distribution, including its moment generating function and characteristic function, are provided in Section 3.

3. Main Properties of the Sy- Family Distributions

Proposition 3.

Let with and support , and let be independent of X. Define . Then Z belongs to the Sy- family, and its PMF is

Proof.

Since X and Y are independent and , consider three cases:

For . Then

For . Writing with ,

For . The event occurs if (regardless of Y) or if with . By independence,

Combining the three cases yields the result. Normalization follows since

□

Corollary 1.

Let Z be an integer-valued random variable and define . Then W has support , and its PMF is

Moreover, we have

3.1. Identifiability Within Sy-

Let , where with and is independent of X. Denote and for . The PMF of Z is

Proposition 4.

From the marginal distribution alone, the pair is not identifiable in the model class

More precisely, for any fixed , there exist infinitely many pairs satisfying (5).

Proof.

Fix . From (5) and the constraint , we have for

Thus, whenever is chosen, the off-zero masses of Y must satisfy for . Using normalization,

which yields

On the other hand, the zero-mass identity in (5) gives

so (6) is consistent for any that makes and for . For all such , we obtain a valid PMF producing the same . Hence, the mapping is not one-to-one on , proving non-identifiability. □

Proposition 5.

Suppose Y belongs to a parametric family with known as a function of λ, and such that for every λ, the map is injective in λ on a set of indices with nonzero . Then the parameter pair is identifiable from .

Proof.

From (5), for any ,

If and produce the same , then agrees for all , and hence

If , the injectivity of in implies that the ratio cannot be constant in k on any set of indices with positive mass; thus, the equality above cannot hold for all unless . Therefore , and then follows from any single . Finally, is automatically satisfied, so is identifiable. □

Corollary 2.

- (i)

- If , then is identifiable.

- (ii)

- If , then is identifiable.

Proof.

For Poisson, and ; distinct produce non-proportional sequences , so the injectivity condition holds. For geometric distributions with success probabilities q, , and ; distinct q once again yield non-proportional sequences on . Proposition 5 applies in both cases. □

Corollary 3.

If θ is known (such as from external calibration), then is recovered from via

and this defines a valid PMF provided arises from a Sy- model with the given θ.

Proof.

Proposition 4 clarifies that, without additional structure on the magnitude Y, the sign parameter , and the zero mass are confounded through , while only the products and are determined by . Imposing a parametric family for Y restores identifiability (Proposition 5), as illustrated by Sy-Poisson and Sy-Geometric (Corollary 2). When is externally known, is uniquely reconstructed from (Corollary 3).

3.2. Tail Behaviour

Proposition 6.

Under the assumptions of Proposition 3, for all ,

Consequently, is tail-equivalent to Y up to factor : if as for some reference function g, then .

Proof.

By (3), for ,

The asymptotic equivalence follows immediately. □

Remark 2.

If Y has exponential (light) tails (for example, Poisson, binomial, geometric), then so does ; if Y has regularly varying (power-distribution) tails, then so does with the same index. The parameter θ scales tail probabilities but does not change their rate.

3.3. Unimodality and Number of Modes

Proposition 7.

Let with , , and be independent. Define the off-zero mode of Y by

Then:

- (i)

- For , . Hence, the positive (and negative) sides of Z are proportional copies of the PMF of Y restricted to , and is the (unique smallest) mode on the positive side of Z as well as the mode of on .

- (ii)

- The global modes of Z are determined by comparing the mass at zero with the peak on the positive side:In particular, using ,

Proof.

Part (i) is immediate from the Sy- PMF: for , , so the positive and negative sides inherit the shape of Y on . For (ii), because both sides are scaled copies of , the only competitors for the global maximum are and . Comparing with yields three cases. □

Corollary 4.

If Y is unimodal with a mode at (such as, geometric or binomial with ), then Z is unimodal at 0 for all . More generally, if Y is log-concave on , then Z is either unimodal at 0 or bimodal at , depending on the inequality in Proposition 7 (ii); no additional modes can appear.

3.4. Cumulative Distribution Function

Proposition 8.

Let with , be a random variable with CDF , independent of X and . The CDF of Z is

Proof.

From the given PMF, , and .

For ,

For ,

For ,

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 5.

Under the assumptions of Proposition 8, let denote the survival function of Z. Then

where denotes the survival function of Y.

3.5. First-Order Stochastic Dominance

We say that A dominates B in the first-order sense if holds for all . For Sy- distributions with and being independent, write

From Proposition 8, for any ,

Theorem 2.

Let with , , and (). If for all , then for all . In particular, strict first-order dominance cannot occur between two distinct members of the Sy- family.

Proof.

Remark 3.

Classical first-order dominance is too restrictive on symmetric two-sided supports. A more informative comparison works on magnitudes. Since ,

This provides a practical dominance notion for dispersion comparisons and for tail–probability assessments based on .

Remark 4.

Other stochastic orders can still distinguish members of the family. In particular, the convex order and increasing–convex order separate distributions with the same mean (zero by symmetry) but different tail weights. For Sy-, many such comparisons reduce to corresponding orders on (or on Y) via the product representation; a systematic treatment is left for future work.

3.6. Generating Function

Proposition 9.

Under the assumptions of Proposition 8, let denote the MGF of Y, and its PGF. Then, for all t,

Proof.

By independence and conditioning on X,

Since and , we obtain

which proves the first identity. The second follows from for integer . The stated domain requires simultaneous finiteness of and . □

Corollary 6.

If , then and .

Proof.

Differentiating at : , and . □

3.7. Quantile Function and Median

Let , , , and be such that . From Proposition 8, for integers ,

Equivalently, for ,

Proposition 10.

Let denote the (left-continuous) quantile function. Set

Then, for ,

where are obtained from Y via

Proof.

The direct inversion of the three pieces above, using that is non-increasing and is non-decreasing on . □

3.8. Median

Corollary 7.

Every Sy- distribution has 0 as a median. Moreover, if , then 0 is the unique median.

Proof.

Since and , we have , so 0 is the unique integer m with . □

3.9. Distribution of Sums and Differences

We now characterize the distribution of sums and differences of independent Sy- variables, showing that they share the same law and admit explicit convolution formulas for their PMFs.

Proposition 11.

Let , , , and be independent of , and be independent. Write and for the one–sided PGF of . Then, for ,

the following holds:

- (i)

- The bilateral PGF of isso for all . Consequently, for the sum and the difference ,and therefore .

- (ii)

- Let . For ,For ,and by symmetry for all . By part (i), the same formulas hold for D.

Proof.

For with and independent of X, we have

thus, using independence and , ,

which yields for all . For independent ,

Since , we obtain , and hence .

On the other hand, let and . By independence,

Splitting the sum into the disjoint cases , , , , and with , and using and for yields

which is (10).

For ,

and substituting the same probabilities gives (11). The symmetry of each implies for , and by part (i) the same formulas hold for D. □

Remark 5.

Equations (10) and (11) decompose the mass of the sum S into three types of contributions: first, cases where one addend is zero; second, positive–positive convolution over ; and third, positive–negative cross terms with unbalanced magnitudes (tails). This partition is useful both for theoretical bounds (for example, tail comparisons driven by the ) and for stable numerical evaluation. If some has finite support, the infinite sums truncate automatically. By Proposition 11, the same decomposition applies to the difference D.

4. Special Case: The Sy-Poisson Distribution

In this subsection, we particularize the Sy- family by taking the mixing variable Y to be Poisson. Recall the set-up in Definition 2 (and Proposition 8): with , takes values in , and .

Definition 3.

Let with and , , be independent. The random variable is said to follow a Sy-Poisson distribution, denoted . Its PMF, inherited from the Sy- construction, is

Consequently, the CDF of Z is obtained from Proposition 8 by replacing with the Poisson CDF.

It is useful to contrast the proposed Sy–Poisson specification with classical symmetric models on . The Skellam distribution, obtained as the difference of two independent Poisson variables, is symmetric but couples the zero mass and tail decay through a single intensity parameter. Similarly, symmetric negative binomial variants provide heavier tails but still link dispersion and central mass through a common shape parameter. Zero-inflated symmetric count models allow for additional mass at zero but do not preserve exact symmetry unless extra constraints are imposed. In contrast, the Sy–Poisson model separates the sign and magnitude mechanisms, offering exact bilateral symmetry, independent control of the zero mass via , and inherited Poisson-type tail behavior through . This decomposition makes the model both flexible and analytically tractable, and it ensures identifiability under mild parametric assumptions, providing advantages over the alternatives above.

Proposition 12.

Let with , , , and be independent. Then the CDF of is

where for , , and denotes the incomplete gamma function defined by .

Proof.

Apply Proposition 8 with equal to the CDF: for , and for . □

Remark 6.

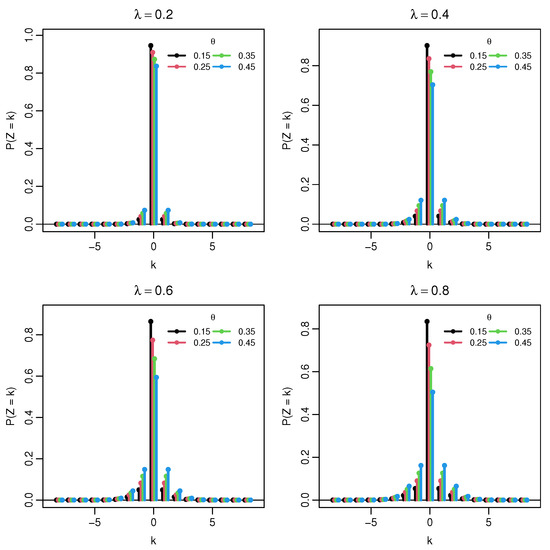

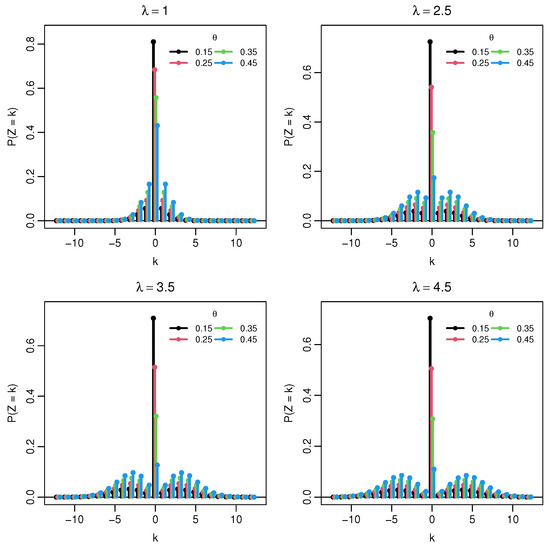

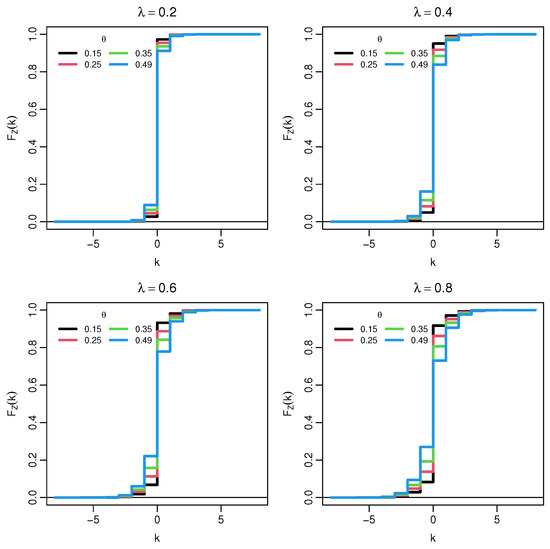

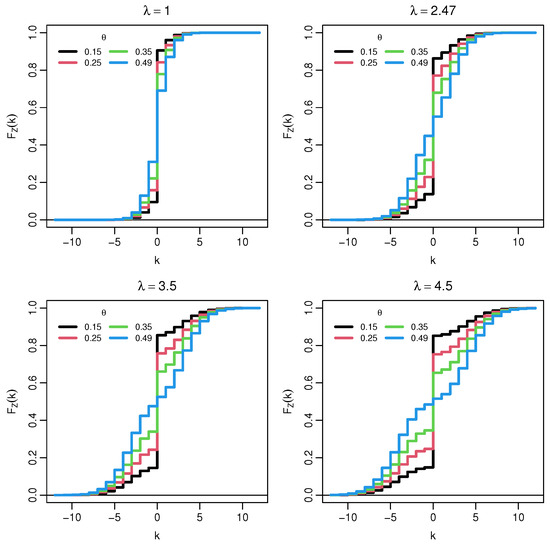

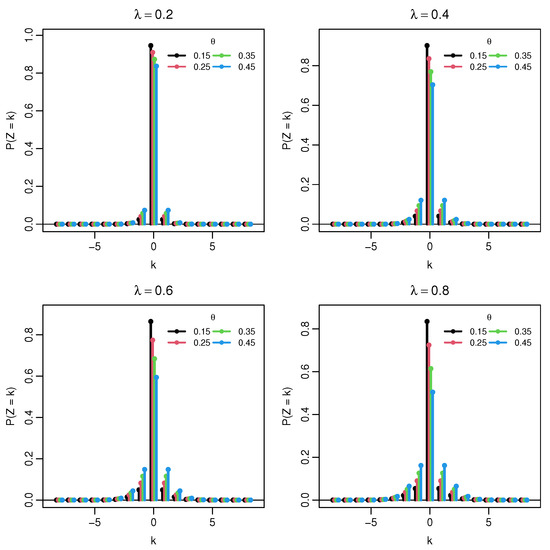

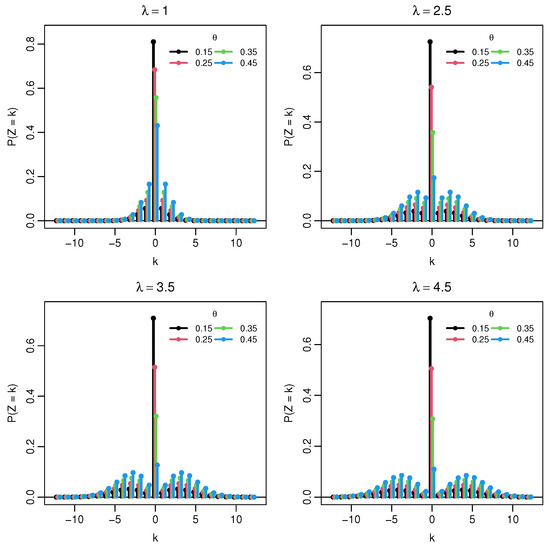

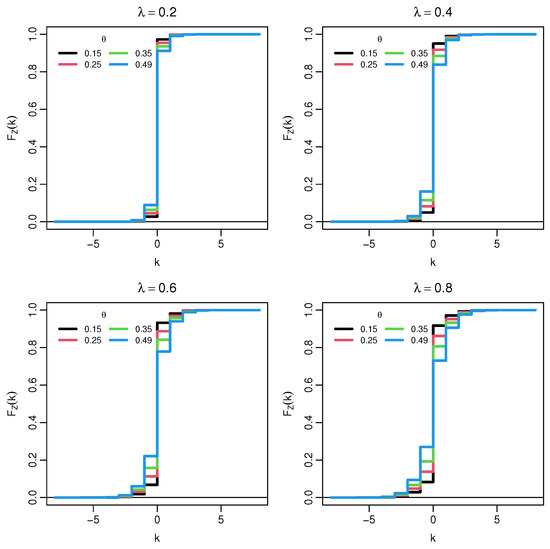

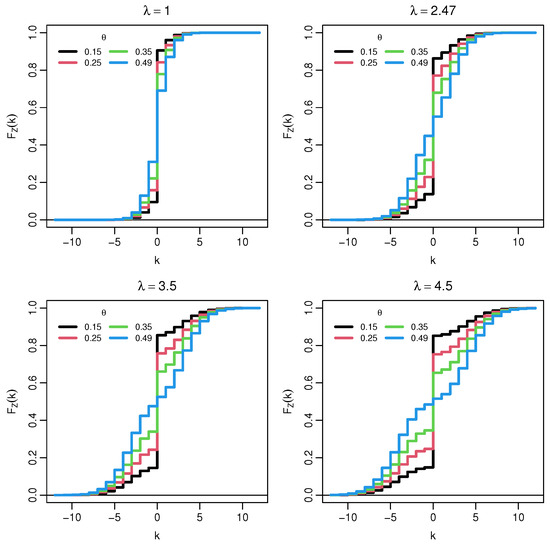

The distribution is symmetric about 0 and zero–inflated, with . For small λ, most of the mass is concentrated at 0, so the PMF is sharply unimodal at the origin. As λ increases, the Poisson component spreads out, and two symmetric shoulders emerge on the positive and negative sides; for moderate and large λ, the central mode at 0 is flanked by two lighter side peaks, yielding an overall three–bump shape. In the limit , the point mass at 0 tends to , and the side peaks become more pronounced, whereas when , the concentration at 0 dominates for any fixed λ. These behaviors are illustrated by the PMF in Figure 1 and Figure 2, and the corresponding CDF in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 1.

Probability mass function of . Each panel fixes .

Figure 2.

Probability mass function of . Each panel fixes .

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution function of . Each panel fixes .

Figure 4.

Cumulative distribution function of . Each panel fixes .

4.1. Generating Functions

Proposition 13.

Let with and , constructed as where and are independent. Then:

Moreover, for all , reflecting the exact symmetry of Z.

Proof.

Condition on X. Since , , and . Use , , and the independence of X and Y. □

Corollary 8.

All odd raw moments vanish, for . For ,

where is the r-th Touchard polynomial [10] (raw moment of a Poisson). In particular,

Hence .

Corollary 9.

Skewness is 0 due to symmetry, and the (non–excess) kurtosis is

and the excess kurtosis equals .

Remark 7.

(i) The identities (14) and (15) yield derivatives at (or ) that recover the even moments without resorting to series expansions. (ii) The symmetry implies that the distributions of and coincide for independent Sy–Poisson variables; see Section 3.9.

4.2. The Total Time on Test Transform

The total time on test (TTT) transform is a standard tool in reliability analysis and quality-control methodology for assessing distributional shape and aging properties. For a non-negative random variable X with distribution function F and survival function , the TTT transform is defined by

where denotes the (generalized) quantile function of F. The function is increasing in u, and its curvature reveals information about the underlying failure rate behavior: concave curves indicate a decreasing failure rate (DFR), convex curves indicate an increasing failure rate (IFR), and curves close to the diagonal correspond to approximately exponential or memoryless behavior.

In practice, the TTT transform is implemented through its discrete empirical version. For ordered non-negative observations , the empirical TTT values are computed as

and the TTT plot is obtained by graphing against . The diagonal line serves as a natural reference: empirical curves lying above the diagonal suggest DFR behavior, while those below the diagonal suggest IFR behavior.

In our setting, we apply the TTT transform to the non-negative magnitudes (equivalently, to the Y component in the Sy- representation), and we compare the empirical TTT plot with the TTT curve implied by the fitted model as a diagnostic tool; see Section 6.

4.3. Shannon Entropy

Proposition 14.

Under the assumptions of Proposition 13, the Shannon entropy (natural logarithm) admits an exact representation

where and . In base-2 units, replace with .

Proof.

Corollary 10.

Using Stirling’s expansion [19] and taking expectations for ,

so that

5. The Statistical Inference of the Model

5.1. Method of Moments Estimation (MoM)

Consider an i.i.d. sample from with and . From Section 4.1 we have

Let the empirical moments be

Matching and to their population counterparts yields a closed form solution. If and , the MoM are

The feasibility conditions and ensure and . If , the estimate lies outside the parameter space; in practice, one may either declare the MoM fit infeasible or project to for a small and use the projected value as initialization for maximum likelihood.

5.2. Asymptotic Distribution and Standard Errors (Delta Method)

Let and . From the closed-form moments,

so

Using ,

A multivariate central limit theorem [20] yields

Define the transformation by and . The Jacobian at is

By the delta method,

with a practical plug-in estimator of V obtained by replacing with .

5.3. Algorithm for MoM Estimation

To facilitate the practical implementation of the inference method, we summarize the computational procedure below, by the Algorithm 1 that outlines the step-by-step calculation of the moment-based estimates.

Remark 8.

The closed form pair provides stable initialization for maximum likelihood, typically improving convergence and reducing sensitivity to local optima. In very small samples, the method of moments may yield close to ; in that case, it is advisable to compare the implied modality (see Proposition 7) using the empirical shape as a diagnostic check.

| Algorithm 1 Computation of MoM estimates |

|

5.4. Likelihood-Based Inference

Given an i.i.d. sample from with and , let and be the numbers of zeros and nonzeros, respectively. Writing , the likelihood factorizes as

so that the log-likelihood is

The score equations are obtained from

The maximum likelihood estimators (MLEs) solve and numerically (no closed form in general). For numerical maximization of the log-likelihood, we used the quasi-Newton BFGS algorithm [21], which provides stable performance for smooth two-parameter models such as . The optimization was initialized at , where is the empirical proportion of zeros, and is the empirical second moment. A convergence tolerance of on both the absolute and relative change in the objective value was imposed. To guard against potential local maxima, the optimization was repeated from five random starting points generated uniformly over . The algorithm converged to identical estimates, indicating that the likelihood is well behaved for the model. These implementation details ensure reproducibility and support the observed numerical stability of the MLE.

5.5. Score Derivatives and Information Matrices

Hessian (second derivatives).

5.6. Observed Information

The observed information matrix is :

An asymptotically consistent covariance estimator for is .

5.7. Expected Fisher Information

Let . Using , , and , the expected (per-observation) Fisher information is

Remark 9.

The observed Fisher information matrix for the model is positive definite whenever belongs to the interior of the parameter space . This follows from the strict concavity of the log-likelihood in both parameters: the sign component induces a strictly negative second derivative in θ, while the Poisson magnitude contributes a negative curvature in λ for all . Consequently, the Hessian matrix is negative definite, and the observed information and its negative remain positive definite away from the boundary. Loss of positive definiteness can only occur near the boundary limits , , or , where the model collapses to a degenerate or nearly degenerate form, and classical asymptotic theory is no longer applicable. Thus, for all practical estimation scenarios in the interior region, the observed information matrix provides a valid and reliable approximation to the asymptotic covariance.

Hence, under standard regularity conditions,

and a large-sample covariance estimator is .

5.8. Percentile Estimators

Percentile estimators provide a robust and intuitive alternative to likelihood and moment based procedures. Because the distribution is defined through a symmetric, zero-centered mixture structure, its shape is largely determined by its quantiles, particularly those away from the median. Percentile estimators, therefore, offer a way to capture the distributional form using direct CDF inversion, without relying on the smoothness of the likelihood or long-tailed moments. Percentile estimators are obtained by matching the empirical and model based percentiles at two symmetric quantiles, namely the 25th and 75th percentiles. Let be the CDF, and let denote the population p-th percentile, given as .

Given empirical percentiles and , which are the sample percentiles at level p, the goal of percentile estimation is to find parameter values such that the model percentiles match the data percentiles. We thus define the percentile estimators as the solution of

These two non-linear equations can be solved numerically to obtain the estimators. The practical utility of the proposed percentile estimators is illustrated in Section 6, where they are applied to both empirical datasets alongside the MLE estimators. The comparison highlights the robustness of percentile-based estimation, especially in settings with moderate tails or irregular zero concentrations.

6. Simulation Study

To evaluate the finite-sample properties of the proposed estimators for , we performed a comprehensive Monte Carlo experiment. This simulation mechanism follows directly from Proposition 1, which characterizes any Sy- random variable as the product of an independent symmetric sign and a non-negative magnitude. Specifically, the representation

The constructive form is associated with the probability mass function given in Equation (12): determines whether or applies, selects the sign when , and Y supplies the magnitude. Thus, the generative steps above reproduce exactly the distribution implied by the theoretical results. For each parameter configuration, 10,000 independent samples of size were drawn under the true parameters . This parameter configuration is representative of many practical scenarios: yields a moderate zero mass in the model, while produces a magnitude distribution with moderate dispersion. Together, these values generate datasets whose symmetry, central concentration, and tail behavior closely resemble those encountered in empirical applications, making them well suited for assessing estimation accuracy in realistic settings. The log-likelihood was maximized numerically to obtain MLEs, and MoM estimators were computed from the first two empirical moments. The Algorithm 2 below provides a concise summary of the exact data-generation procedure used in all Monte Carlo experiments. This step-by-step formulation clarifies how independent draws from the model are produced and ensures full reproducibility of the simulation design.

| Algorithm 2 Generation of an i.i.d. sample from |

|

6.1. Comparison of MLE and MoM Estimators

For each n, bias and mean-squared error (MSE) were calculated as

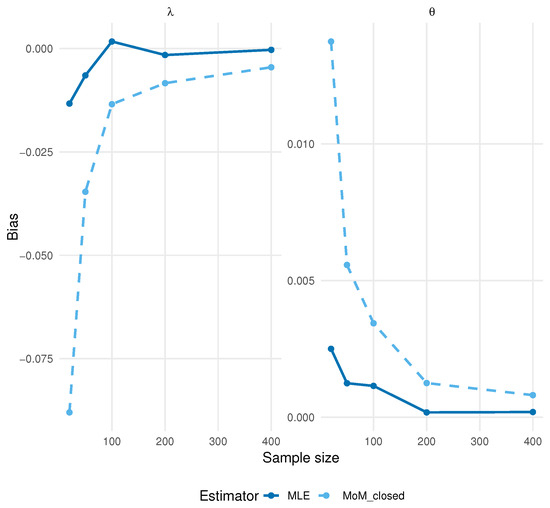

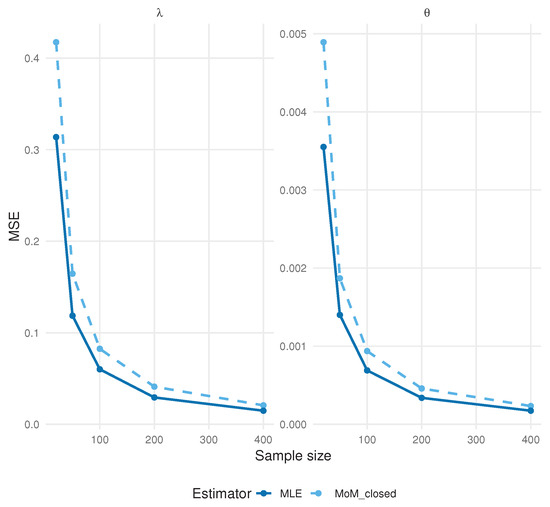

with . Figure 5 plots Monte Carlo estimates of against n, whereas Figure 6 plots Monte Carlo estimates of against n.

Figure 5.

Bias of and under . Curves compare MLE and MoM estimators across sample sizes.

Figure 6.

MSE of and under . Curves compare MLE and MoM estimators across sample sizes.

Both MLEs and MoM estimators show rapidly vanishing bias and MSE as the sample size increases, consistent with standard asymptotic theory. The MoM estimator displays a slightly higher MSE for small n compared to the MLE, but its performance converges to that of the MLE as .

Across the grid of n, shows a mild positive bias, while tends to underestimate the true value. Moreover, remains larger than , reflecting the higher sampling variability of the rate parameter. These bias patterns are consistent with the structure of the log-likelihood and the Fisher information described in Section 5.8. The information for is primarily driven by the zero and near zero observations, where the curvature of the likelihood is pronounced; this yields relatively strong identifiability for and explains the small positive finite-sample bias. In contrast, the information for depends on the dispersion of the magnitude component: when many observations fall at or near zero, the effective information about is reduced, leading to a mild tendency toward underestimation. As the sample size increases, both information components scale linearly with n, causing the biases in and to diminish, in agreement with the asymptotic theory.

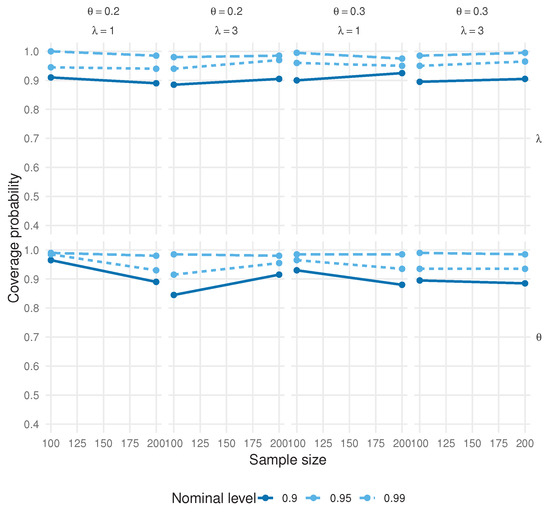

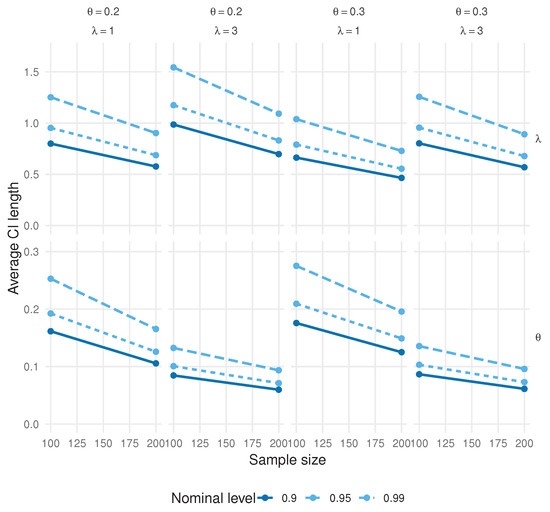

6.2. Standard-Error Accuracy and Confidence-Interval Coverage

To assess standard-error accuracy and validate asymptotic normality, we formed observed Wald confidence intervals using the inverse Hessian at the MLE, as given by . For each replication and parameter, we constructed two-sided Wald intervals at the 90%, 95%, and 99% nominal levels and recorded empirical coverage along with the average interval length. Figure 7 reports the CI coverage, whereas Figure 8 shows the average CI length as functions of n.

Figure 7.

Empirical coverage probabilities of the observed Wald confidence intervals for and as a function of n.

Figure 8.

Average lengths of the observed Wald confidence intervals for and as a function of n.

The observed Wald intervals show coverage approaching nominal levels as n increases, with noticeable gains between small and moderate sample sizes. In cases of small , the intervals can be slightly conservative for very small n, but accuracy improves quickly with n, and the average lengths decrease at the expected rate, consistent with the asymptotic theory for the MLE.

A further point of reassurance concerns the use of Wald confidence intervals in a discrete setting. Although discrete models sometimes induce irregular likelihood shapes and poor Wald performance, the model benefits from a smooth and strictly concave log-likelihood in both parameters. The independence between the symmetric sign and the Poisson magnitude yields well-behaved score functions and a Fisher information matrix that remains finite and positive for all admissible . These properties ensure that the MLEs lie well within the interior of the parameter space and satisfy standard differentiability conditions, so Wald intervals inherit the usual asymptotic validity even in finite samples. This explains why the simulation results show accurate coverage levels despite the inherent discreteness of the data-generating process. The observed coverage behavior can be directly linked to the analytical form of the Fisher information derived in Section 5.8. When the zero mass is large, the term in the information matrix (where ) dominates, yielding high curvature of the log-likelihood with respect to and, therefore, tighter confidence intervals. Conversely, the information component associated with depends on both and through , which can be relatively flat for small . This explains why the empirical coverage for tends to be slightly conservative in small samples, whereas the coverage for rapidly approaches nominal levels. As the sample size increases, both components of the Fisher information scale linearly with n, leading to asymptotic normality and the near-exact coverage observed for .

7. Practical Data Analysis

We illustrate the applicability of the proposed model using two real-life datasets. After first-differencing (day-to-day or session-to-session changes), the outcomes lie on , matching the model’s support.

7.1. PTT Stock Price Increments (Thailand, 2014)

The first dataset, previously analyzed in ref. [4], consists of daily closing prices for the Petroleum Authority of Thailand (PTT), recorded from 1 April 2014 to 20 October 2014 (Stock Exchange of Thailand). For completeness, the data are as follows:

-12, -11, -9, -8, -7, -6, -6, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -4, -4, -4, |

-4, -4, -4, -4, -4, -4, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -2, -2, |

-2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, |

-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, |

1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, |

3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5, 5, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 7, 7, |

7, 7, 8, 8, 9, 9, 9, 10, 14 |

According to ref. [4], we model price increments; that is, the day-to-day change in the closing price is measured in integer Baht. A Mann–Kendall test against a monotonic trend yields a p-value of , providing no evidence of such a trend and supporting the i.i.d. working assumption for the increment series.

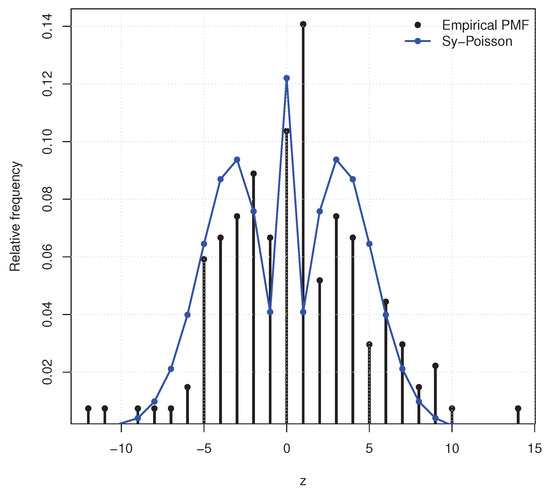

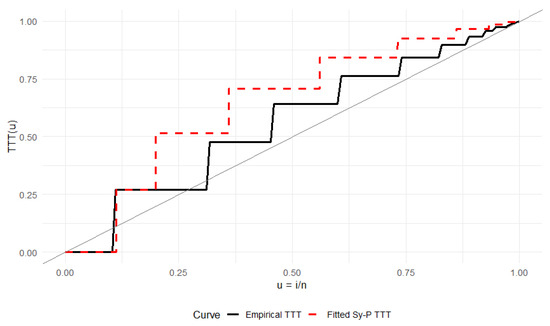

We fit by maximum likelihood, obtaining . A Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test gives , indicating an adequate fit. Furthermore, we also find the percentile estimators by fixing of the parameters, which are given by . Figure 9 overlays the fitted probability mass function on the empirical frequencies. Figure 10 contains the total time on test (TTT) plot, as described in Section 4.2. The empirical TTT curve was compared to the TTT curve implied by the fitted model. A close alignment of the curves indicates an adequate fit.

Figure 9.

Empirical PMF and fitted for PTT price increments.

Figure 10.

TTT plot for PTT price increments comparing the empirical curve with the fitted model. The diagonal line represents the exponential distribution reference.

For benchmarking, we also fit the perturbed discrete Laplace [6], the discrete Laplace , the discrete normal [5], and the discrete asymmetric Laplace [4]. Table 1 reports log-likelihood, AIC, and BIC. The model attains the smallest AIC/BIC, and, following ref. [22], the BIC differences relative to competitors exceed 2, providing positive evidence in favor of . This good empirical fit is consistent with the theoretical properties of the model. The financial return increments are nearly symmetric and exhibit a pronounced central mass at zero; the structure accommodates both features naturally through its symmetric sign component and the tunable zero probability governed by . Moreover, the inherited Poisson tail behavior aligns well with the moderate dispersion observed in the positive and negative increments, explaining the improved information-criteria performance over classical competitors.

Table 1.

Model comparison for PTT price increments.

Remark 10.

The fit closely tracks competitors while imposing exact symmetry around zero and supporting closed-form manipulations for sums and differences (Section 3.9).

7.2. Attendance Increments in a Marketing Course (Lyon, 2012–2013)

We revisit a dataset previously analyzed in ref. [18], where the extended Poisson model was introduced. The data record attendance counts for 60 consecutive marketing sessions in the Bachelor program at IDRAC International Management School (Lyon, France), between 1 September 2012 and 1 April 2013. For completeness, the exact dataset is as given below:

-5, -5, -5, -4, -4, -4, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -3, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, |

-2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, 0, |

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, |

3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

As documented in ref. [18], we analyze first differences between consecutive sessions, yielding integer-valued observations ranging from to 7. This transformation centers the process and produces signed counts, providing a natural benchmark for two-sided discrete models.

As a preliminary diagnostic, the runs test reported in ref. [18] indicates that while the raw series is not random (p-value ), the differenced series behaves as an approximately random sample (p-value ), supporting independent-sample modeling at the differenced scale. We fit the symmetric Poisson model by maximum likelihood and compare it with standard competitors: discrete Laplace , perturbed discrete Laplace [6], discrete normal [5], and the extended Poisson introduced in ref. [18]. Model fit is assessed via log-likelihood and information criteria (AIC/BIC), using grouped frequencies consistent with ref. [18] for the goodness-of-fit evaluation.

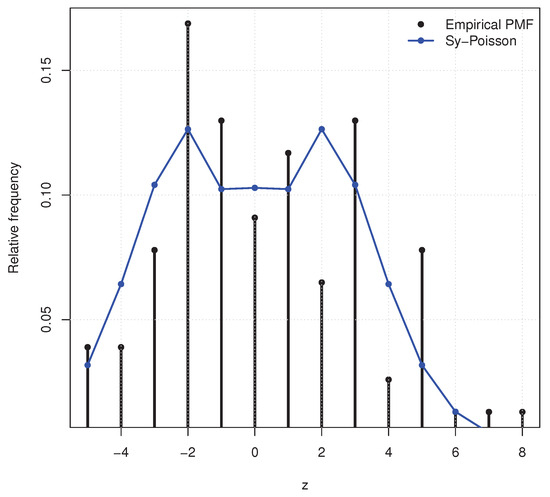

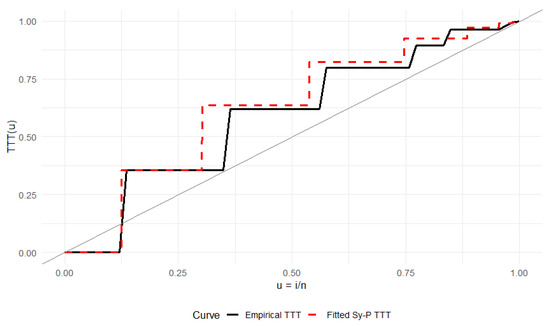

Figure 11 displays the fitted probability mass functions, whereas Figure 12 contains the Total Time on Test (TTT) plot. The empirical TTT curve was compared to the TTT curve implied by the fitted model. A close alignment of the curves indicates an adequate fit. Table 2 reports the numerical comparisons. The symmetric Poisson achieves the best (smallest) AIC and BIC, marginally improving upon the extended Poisson while preserving explicit symmetry around zero. The estimated parameters for are and , consistent with a zero-centered, moderately dispersed pattern with a high concentration of probability near the origin. Further, we also find the percentile estimators by fixing of the parameters, which are given by . The favorable fit obtained for attendance differences directly reflects the strengths of the specification. These data are balanced around zero and moderately dispersed; the model captures these patterns through exact symmetry, flexible control of the zero mass via , and tail heredity from the Poisson magnitude. Such theoretical features translate into practical performance, as confirmed by the reduced AIC/BIC values relative to other symmetric alternatives.

Figure 11.

Empirical PMF and fitted for attendance increments.

Figure 12.

TTT plot for attendance increments comparing the empirical curve with the fitted model. The diagonal line represents the exponential distribution reference.

Table 2.

Model comparison for attendance increments (IDRAC, Lyon, 2012–2013).

Remark 11.

(i) The fit closely tracks the extended Poisson while enforcing exact symmetry and offering closed-form tools for sums/differences (Section 3.9). (ii) The estimate lies near the upper boundary , aligning with pronounced concentration at zero and balanced tails; convergence diagnostics were stable under maximum likelihood with MoM initialization.

8. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we introduce the Sy- family, a unified and tractable framework for symmetric integer-valued modeling based on a simple sign-magnitude decomposition. Writing with and as independent variables yields models that are exactly symmetric around zero, allowing for interpretable control of the atom at zero and inheriting tail behavior and dispersion from the chosen magnitude distribution. Within this framework, we derived closed-form expressions for the PMF and CDF, bilateral generating functions, and even-order moments; established a characterization by symmetry and sign-magnitude independence; and studied tail transfer, modality, and the equality in law between sums and differences of independent Sy- variables.

Specializing in a Poisson magnitude leads to the Sy-Poisson model, for which we obtained explicit generating functions, moment identities, and entropy, and developed both method-of-moments and likelihood-based inference. Monte Carlo simulations showed that the maximum likelihood estimators exhibit small finite-sample bias and accurate Wald confidence-interval coverage, while the TTT plots and empirical applications in finance and education confirmed that Sy-Poisson can match or improve upon classical two-sided competitors on . Beyond these case studies, the sign-magnitude structure suggests further applications in quality-control contexts, where signed deviations from target defect levels or specification limits arise naturally. Promising directions for future work include regression extensions, dependence modeling and time-series formulations, multivariate constructions, and the development of Sy- based monitoring tools for quality-control problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.B. and M.K.; methodology, M.K., H.S.B., H.S.S., S.R.B. and L.A.; software, M.K. and S.R.B.; validation, M.K., H.S.B., H.S.S. and S.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., H.S.B., H.S.S. and S.R.B.; writing—review and editing, M.K., H.S.B., H.S.S., S.R.B., L.A. and A.F.D.; visualization, M.K., S.R.B., L.A. and A.F.D.; funding acquisition, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Easy Funding Program grant code (NU/EFP/SERC/13/239).

Data Availability Statement

This paper’s application section includes a list of the data that were used, along with their citations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Easy Funding Program grant code (NU/EFP/SERC/13/239).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proposition A1.

Let . Consider independent random variables and . Define the random variable

Then , and its PMF is given by

Proof.

By the definition of X, we have

Hence . Using the independence of S and T,

and similarly

Thus X has a PMF

which is exactly . □

Proposition A2.

To generate a random variable :

- 1.

- Generate .

- 2.

- Set

Proof.

Since , for any interval we have . By the construction,

Hence

Thus X has PMF

which is exactly . □

References

- Skellam, J.G. The frequency distribution of the difference between two Poisson variates belonging to different populations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1946, 109, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inusah, S.; Kozubowski, T.J. A discrete analogue of the Laplace distribution. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2006, 136, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, A. An alternative discrete skew Laplace distribution. Stat. Methodol. 2014, 16, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpoom, S.; Bodhisuwan, W. The discrete asymmetric Laplace distribution. J. Stat. Theory Pract. 2016, 10, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. The discrete normal distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2003, 32, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, S.R.; Bakouch, H.; Chesneau, C. A distribution on Z via perturbing the Laplace distribution with applications to finance and health data. STAT 2023, 12, e535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chakravarty, D. A new discrete probability distribution with integer support on (−∞,∞). Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2016, 45, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.H.; Shimizu, K.; Choung, M.N. A class of distribution arising from difference of two random variables. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, D.; Ntzoufras, I. Analysis of sports data using bivariate Poisson models. Statistician 2003, 52, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L.; Kemp, A.W.; Kotz, S. Univariate Discrete Distributions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics 1992, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Lateef, S.G. A discrete probability model suitable for both symmetric and asymmetric count data. Filomat 2020, 34, 2559–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesneau, C.; Pakyari, R.; Kohansal, A.; Bakouch, H.S. Estimation and prediction under different schemes for a flexible symmetric distribution with applications. J. Math. 2024, 2024, 6517277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesneau, C.; Bakouch, H.S.; Tomy, L.; Veena, G. A new discrete distribution on integers: Analytical and applied study on stock exchange and flood data. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2022, 25, 1899–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomy, L.; Veena, G. A retrospective study on Skellam and related distributions. Austrian J. Stat. 2022, 51, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, D.; Mamode Khan, N. Models for integer data. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2023, 10, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakouch, H.S.; Kachour, M.; Nadarajah, S. An extended Poisson distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2016, 45, 6746–6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi, V.K.; Saleh, A.K. An Introduction to Probability and Statistics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Raftery, A.E. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol. Methodol. 1995, 25, 111–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).