1. Introduction

Researchers have conducted thorough investigations into the nonlinear conformable partial differential equations, aiming to derive exact and explicit soliton solutions through a variety of methodological [

1]. Each method offers unique insights into the behavior of solitons under different conditions, enabling scientists to better understand and predict soliton dynamics. The ongoing research in this area not only enhances the theoretical framework of soliton theory but also has practical implications for fields like fiber optics, fluid dynamics, and plasma physics, where soliton solutions play a crucial role [

2]. Recently, various mathematical models have been thoroughly studied and are drawing significant interest. As science and technology continue to advance rapidly, soliton theory has become increasingly important in contemporary scientific research [

3]. Its applications span various crucial physical domains, such as optoelectronics, nonlinear optics, and water wave analysis, among others [

4,

5,

6].

Optical solitons are a significant type of wave, known for their capacity to retain their shape over extended distances while experiencing minimal disruption from scattering. These distinctive characteristics play a key role in nonlinear optics, where they contribute to the development and enhancement of equations designed to precisely model soliton solutions. Research on optical solitons is advancing rapidly across various fields of applied sciences [

7,

8,

9]. Soliton solutions have found extensive application in multiple domains, including nonlinear communication engineering, fluid dynamics, plasma physics, and optics. These solutions are pivotal for enhancing global communication networks, which are essential for modern technological advancement. To introduce soliton solutions for nonlinear evolution equations, mathematicians have devised advanced analytical and numerical methods [

10,

11,

12]. Researchers employ a variety of nonlinear physical models to investigate and predict the behavior of soliton waves. Consequently, soliton waves are becoming increasingly significant in areas such as ferromagnetic materials and nonlinear optics. Optical solitons [

13,

14], in particular, are known for their ability to maintain their shape over long distances with minimal scattering. This characteristic makes them highly valuable in nonlinear optics, where their distinctive properties contribute to the development and analysis of equations that model soliton solutions. The study of optical solitons is progressing rapidly across several applied scientific fields [

15,

16].

In [

17], N. Kudryashov, a Russian mathematician, presented a model for the nonlinear refractive index, offering a thorough framework to describe pulse propagation within nonlinear optics. These concepts are enhancing soliton pulse performance, helping manage Internet bottlenecks in optical fibers, photonic crystal fibers, optical metamaterials, and similar waveguides. Recently, novel forms of nonlinear refractive index have introduced diverse self-phase modulation (SPM) effects in the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE) [

18,

19]. Consider the following form of time-conformable nonlinear Schrödinger equation [

20]:

In the above equation,

t signifies temporal variables while

x denotes spatial variables. Here,

n and

m are the power nonlinearity parameter and the maximum intensity. The coefficient

a is the chromatic dispersion and

are the nonlinearity coefficients. Further, the coefficients

and

represent the nonlinearity dispersion and the higher order coefficients, respectively. The present model with fourth order dispersion and third order dispersion using improved modified extended tanh method was studied by Samir et al. [

21]. Cubic-quartic exact solutions for the Kudryashov law, featuring a dual form of generalized nonlocal nonlinearity are constructed in [

22]. Compare to the soliton solutions presented in [

20,

21,

22], the optical soliton solutions constructed in this paper are novel and have not been reported previously in the literature. Further,

represents the conformable derivative. We explore the fundamentals of conformable derivatives, essential for understanding the dynamics of complex physical phenomena. conformable derivatives find applications across physics, engineering, finance, and biology, highlighting their value in analyzing complex systems. The Conformable derivative define as:

Suppose that

and

are conformable differentiable of order

, and

. The following hold [

23]:

- i.

- ii.

for all .

- iii.

.

- iv.

.

This study investigates the nonlinear Schrödinger equation incorporating a self-phase modulation (SPM) type, utilizing Kudryashov’s generalized refractive index with a conformable derivative relevant to diverse aspects of pulse propagation in optical fibers. By applying the modified simplest equation method, several novel soliton solutions are derived. The principal objective of this research is to examine the dynamic behavior of these newly constructed optical soliton solutions within the framework of the NLSE with a conformable derivative. Physically, the conformable parameter can be interpreted as a measure of the medium’s degree of nonlocality or heterogeneity. When , the model reduces to the classical integer-order case, representing an ideal homogeneous optical fiber. For , the system accounts for nonuniformities, memory effects, or deviations from perfect homogeneity that naturally arise in realistic nonlinear optical materials. Thus, offers a tunable link between ideal and conformable behaviors, enabling a more flexible description of soliton dynamics in complex or weakly disordered media.

Symmetry plays a central role in analyzing nonlinear evolution equations, including the conformable NLSE studied here. Invariant transformations—such as scaling, phase rotation, translation, and amplitude–phase couplings—help organize the equation’s solution space and explain why certain soliton profiles persist under conformable -order effects. These symmetry features also support the stability and classification of the soliton families derived through the modified simplest equation method. By linking the model to its underlying symmetry structure, this study fits naturally within current symmetry-oriented research and contributes to ongoing developments in the analysis of nonlinear optical wave equations.

3. Application of Modified Simplest Equation Method

In this section, we present several novel optical soliton solutions for the current model using the modified simplest equation method. We assume that the solution to Equation (

9) can be expressed as the following series:

where

are real constants, and

N denotes a balancing parameter. By balancing principle for

and

in Equation (

9), we obtain

. Thus, Equation (

10) reduces to the following series:

where

satisfies the following relation:

The solutions to the above equation with parameter s can be defined as follows:

By substituting Equations (

11) and (

12) into Equation (

9), we obtain a polynomial in terms of the powers of

. Next, we organize the terms according to their respective powers and equate each corresponding coefficient to zero. This procedure results in a system of algebraic equations as follows:

Case 1: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

13)–(

17) and (

23), the following solutions are acquired:

Case 2: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

18)–(

22), and (

23), the following solutions are acquired:

where

.

Case 1: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

13)–(

17) and (

34), the following solutions are acquired:

Case 2: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

18)–(

22), and (

34), the following solutions are acquired:

where

Case 1: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

13)–(

17) and (

45), the following solutions are acquired:

Case 2: If

Utilizing Equations (

3), (

6), (

7), (

11), (

18)–(

22), and (

45), the following solutions are acquired:

where

.

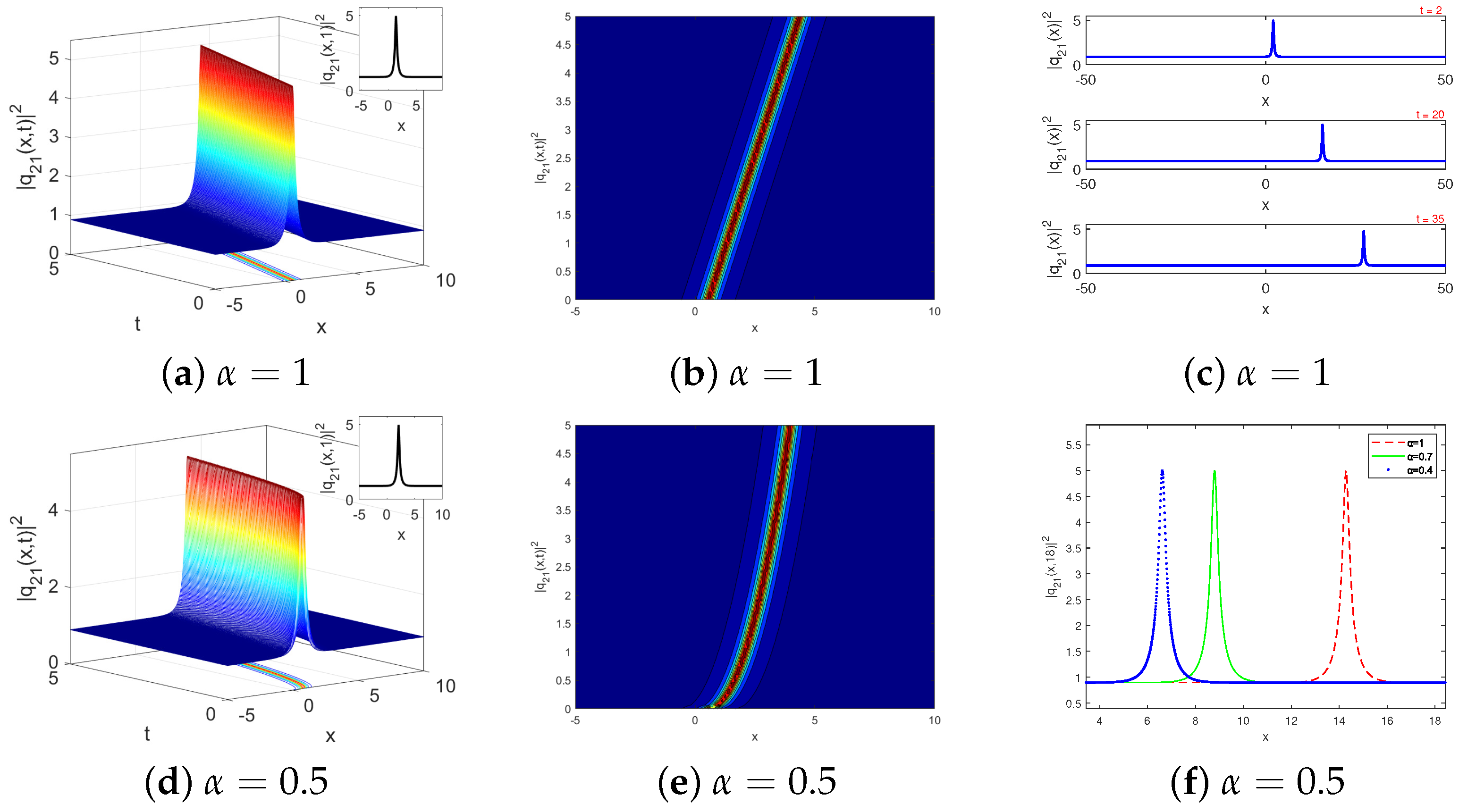

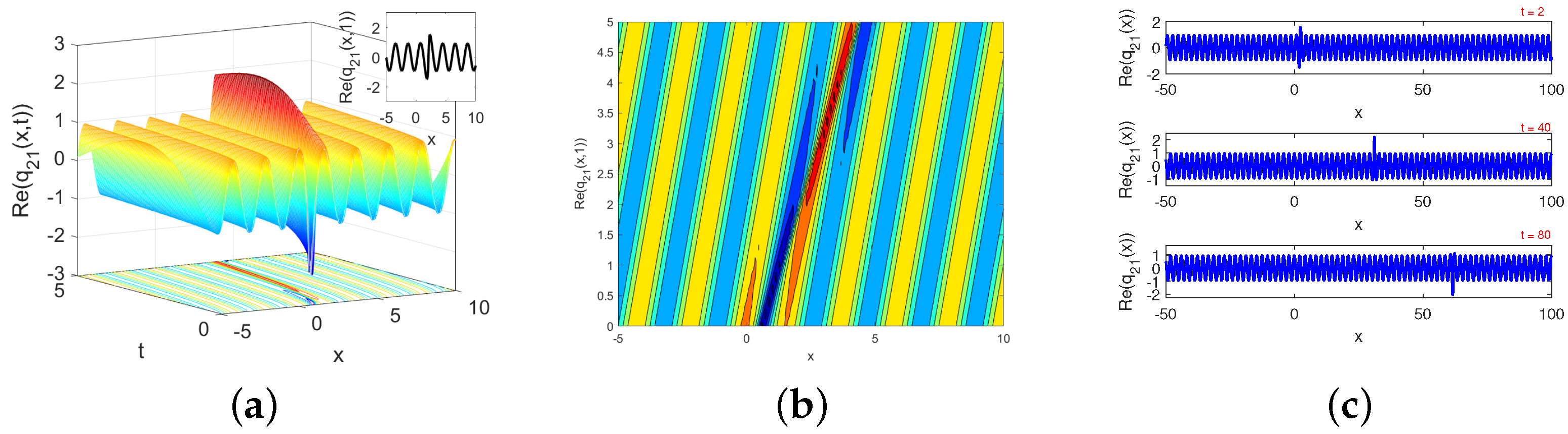

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, specific values of the physical parameters are selected to emphasize the significance of the newly derived optical solutions in the context of the governing equation. The effect of the parameters

and

t on the derived soliton solutions is demonstrated using three-dimensional and two-dimensional plot graphs.

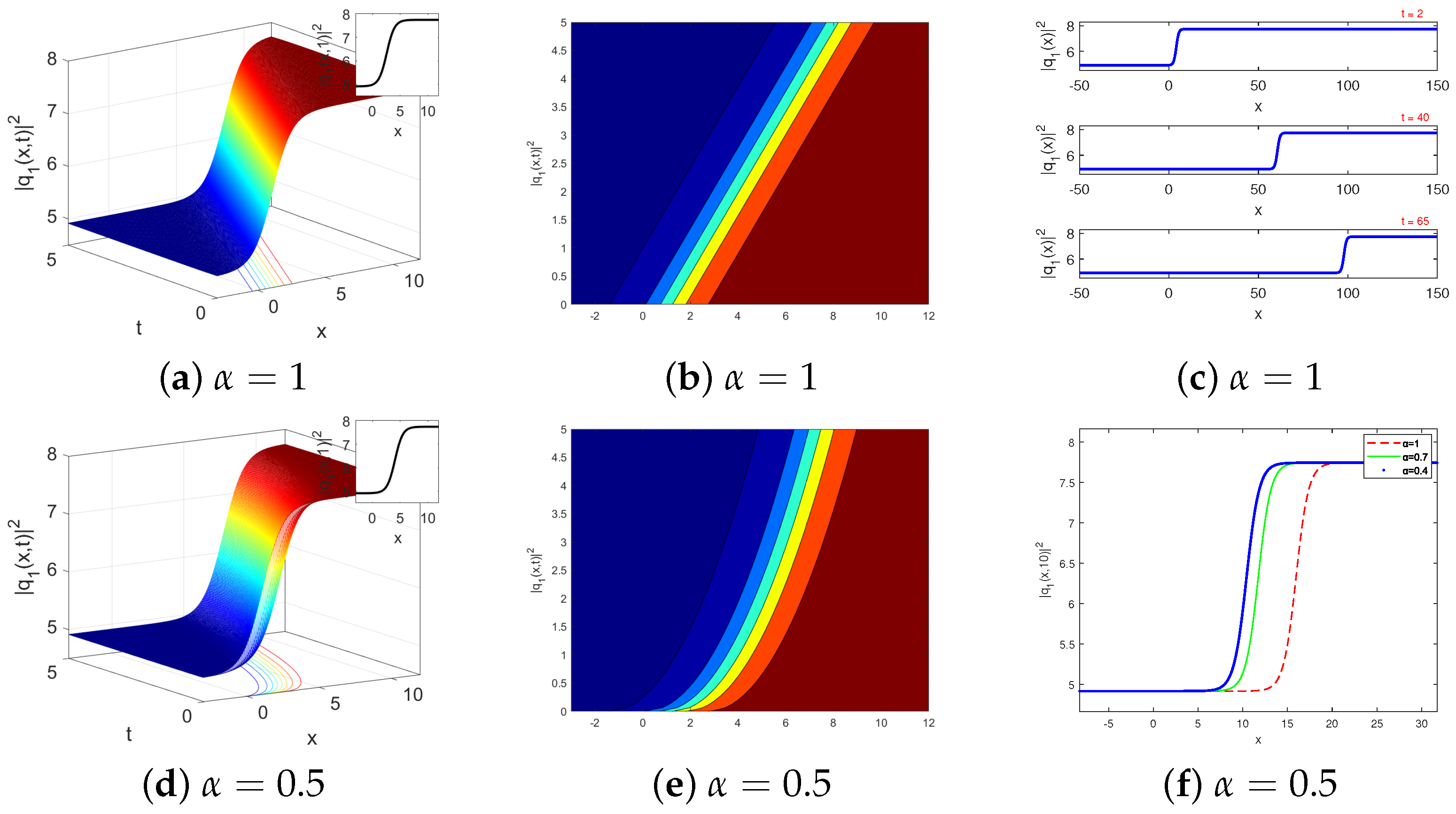

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 provide contour, three-dimensional, and two-dimensional visualizations that depict the behavior of the current solutions.

The three-dimensional plot and the contour plot, and the two-dimensional plot illustrate the effect of the temporal parameter on the two-dimensional plot of the kink-type soliton solutions of

is presented in

Figure 1a,

Figure 1b, and

Figure 1c, respectively. However, the effect of the conformable parameter on the three-dimensional plot, the contour plot, and the two-dimensional plot of the kink-type soliton solutions of

is presented in

Figure 1d,

Figure 1e, and

Figure 1f, respectively. In optical fiber systems, modulating input pulses to mimic kink-type soliton profiles can lead to more robust data transmission. Engineers can adjust parameters like pulse width, amplitude, and fiber nonlinearity to optimize transmission characteristics and achieve desired stability.

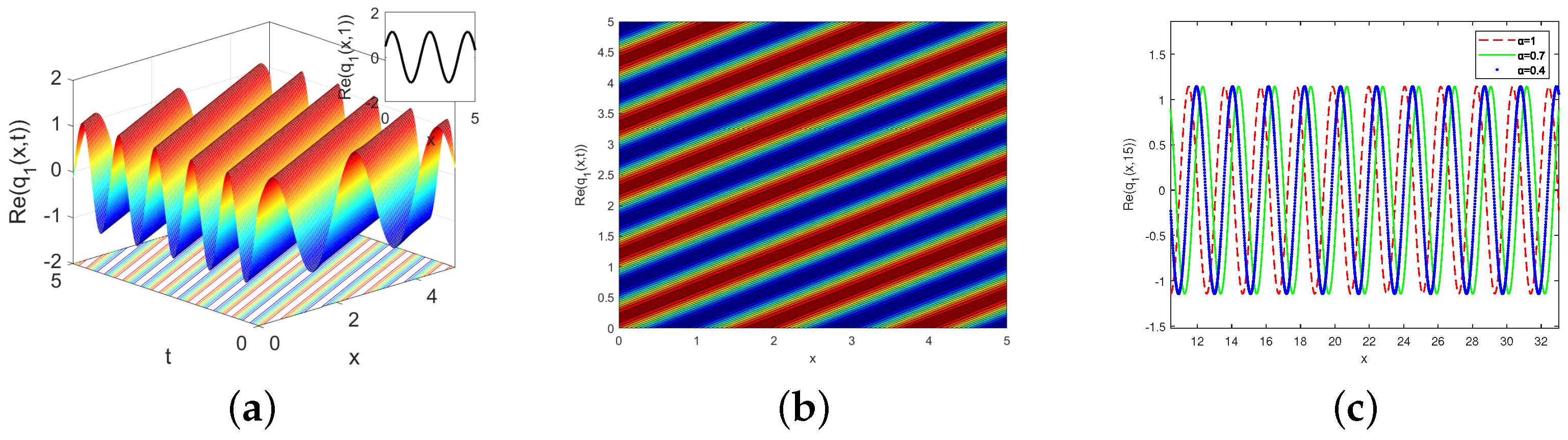

Figure 2a,

Figure 2b, and

Figure 2c depict the three-dimensional plot, the contour plot, and the effect of the temporal parameter on the two-dimensional plot of the wave optical solution

, respectively. In the context of optical fiber communication systems, modulating input pulses to mimic kink-type soliton profiles can enhance signal robustness and resistance to dispersion and noise. Practical control over parameters such as pulse width, amplitude, and fiber nonlinearity enables engineers to optimize energy confinement and transmission stability.

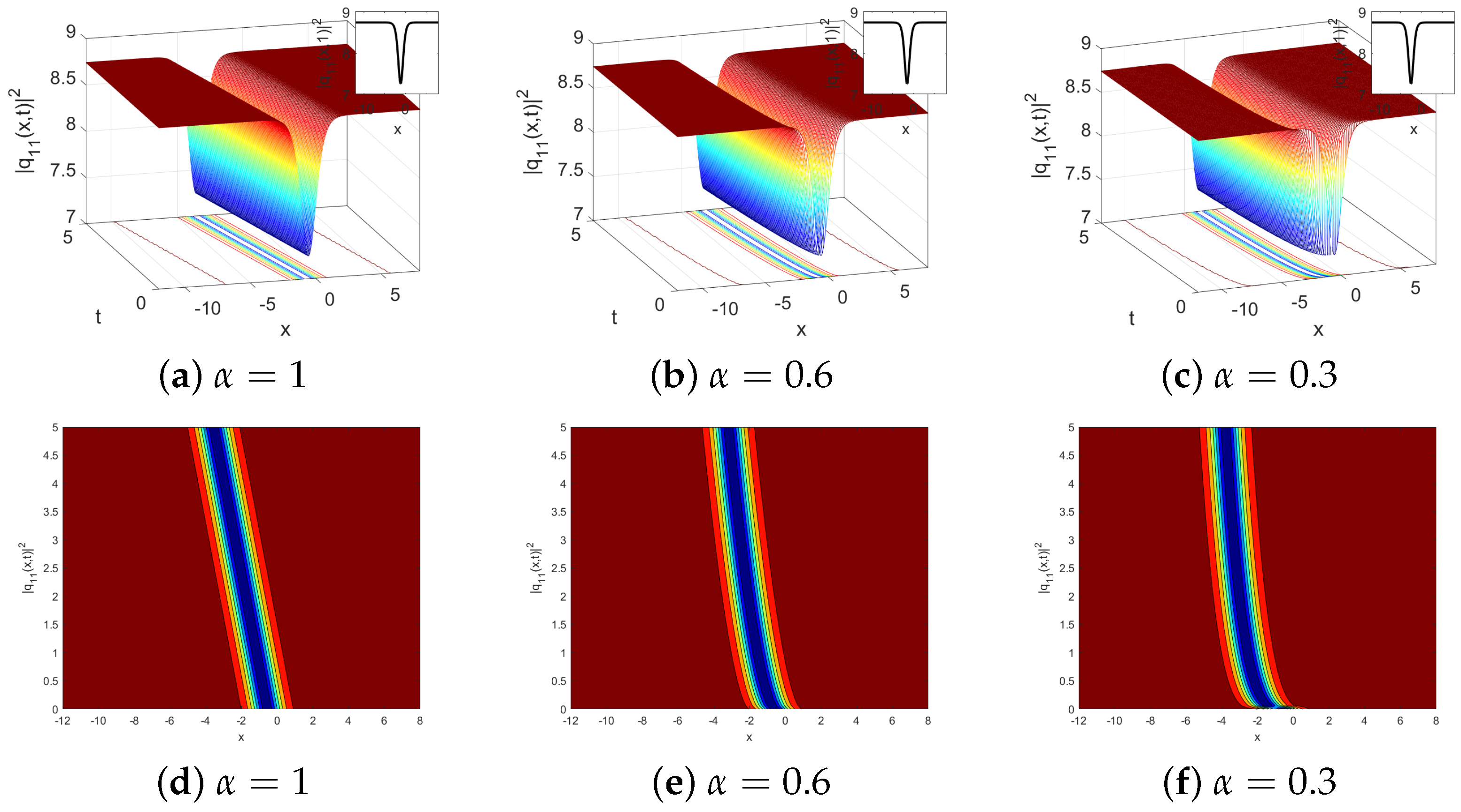

The three-dimensional plot, contour plot, and two-dimensional plot in

Figure 3a,

Figure 3b, and

Figure 3c, respectively, illustrate the impact of the time parameter on the two-dimensional plot of the dark soliton solutions of

. However, the effect of the conformable parameter on the three-dimensional plot, the contour plot, and the two-dimensional plot of the dark soliton solutions of

is presented in

Figure 3d,

Figure 3e, and

Figure 3f, respectively. Dark solitons are crucial for optical communication, where they can propagate without distortion over long distances, preserving the integrity of transmitted signals. The analysis of different values of the conformable derivative allows for a deeper understanding of how solitons behave under varying conditions, which is essential for managing dispersion and nonlinearity in fiber optics. This insight can aid in optimizing pulse propagation in optical fibers, enhancing the efficiency of high-speed data transmission, and improving the design of optical switches, modulators, and filters in photonic devices. These results reveal how variations in the conformable parameter alter the soliton’s amplitude, width, and velocity, reflecting the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity within the medium.

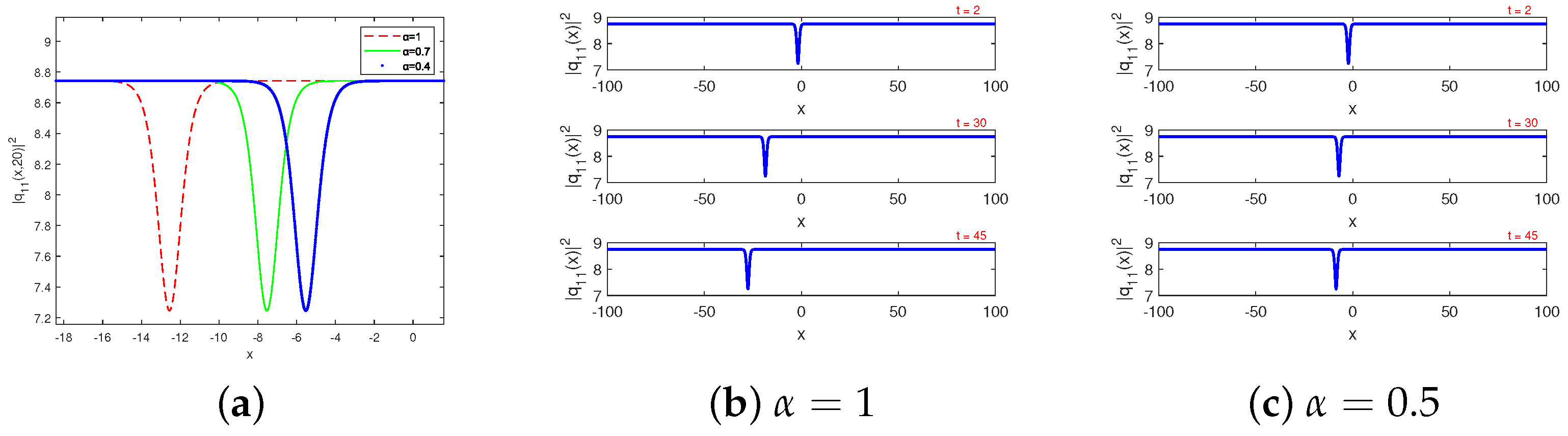

Figure 5a illustrates the impact of the conformable parameter on the soliton solution

, while

Figure 5b and

Figure 5c depict the effect of the temporal parameter on the soliton solution

for two different values,

and

, respectively. The three-dimensional plot and the contour plot, and the two-dimensional plot illustrate the effect of the temporal parameter on the two-dimensional plot of the bright soliton solutions of

is presented in

Figure 5a,

Figure 5b, and

Figure 5c, respectively. However, the effect of the conformable parameter on the three-dimensional plot, the contour plot, and the two-dimensional plot of the bright soliton solutions of

is presented in

Figure 5d,

Figure 5e, and

Figure 5f, respectively. It is evident that decreasing

leads to a broader soliton width and a slight reduction in peak amplitude, indicating that the conformable derivative directly modulates the soliton’s energy confinement and propagation stability.

Figure 6a,

Figure 6b, and

Figure 6c depict the three-dimensional plot, the contour plot, and the effect of the temporal parameter on the two-dimensional plot of the wave optical solution

, respectively. These results suggest that the conformable derivative parameter

plays a significant role in controlling dispersion and nonlinearity balance, making it a tunable factor for managing pulse dynamics in practical optical fiber systems such as dispersion-managed or photonic crystal fibers.

The conformable derivative, applied in the context of optical fibers, can be used to model more complex and realistic physical phenomena, such as nonlinearity and dispersion, in ways that traditional calculus might not fully capture. The conformable derivative generalizes the classical derivative, allowing conformable -order dynamics to be incorporated into models. In optical fiber systems, this can enhance the modeling of pulse propagation, including the behavior of solitons. By using the conformable rule, researchers can explore how varying degrees of nonlinearity and dispersion affect the stability, shape, and speed of solitons, providing more flexibility in fine-tuning optical fibers for specific applications. This can improve signal processing, such as in high-capacity data transmission, optical switches, and the control of light pulses in photonic circuits.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive exploration of the nonlinear conformable Schrödinger equation enhanced by Kudryashov’s generalized refractive index, uncovering novel soliton solutions with unique dynamic characteristics. By applying the modified simplest equation method, we derived a range of soliton profiles, including kink-type, wave, dark, and bell-shaped solitons, each visualized through 2D, 3D, and contour plots. These results highlight the significance of the conformable order parameter in modulating soliton behavior, demonstrating the valuable role of conformable calculus in modeling nonlinear wave dynamics. Alongside the analytical results, the extensive collection of the 2D and 3D, and contour figures offers a clear visual interpretation of how the obtained solutions evolve under varying physical parameter regimes. The graphical analyses demonstrate the influence of the conformable derivative order, nonlinear refractive index on the amplitude, and dispersion parameters, width, and propagation behavior of the obtained solitons. Moreover, relative to prior studies of the NLSE model incorporating Kudryashov-type refractive indices and fractional or conformable operators, the present work offers a wide range of solutions and more intricate dynamical features. Previous works typically focus on limited soliton categories or confine their analysis to classical-order derivatives. In contrast, this work identifies novel solitons and parameter-dependent dynamical behavior that have not been documented in earlier literature. The combined graphical and analytical comparison illustrates the unique contribution of this research and reinforces the suitability of the conformable NLSE framework for modeling complex optical pulse propagation. Our findings mark a substantial improvement over classical models, offering new perspectives for optical fiber communication, where controlling pulse distortion and maintaining signal integrity are vital. This research thereby makes an important contribution to the study of nonlinear wave propagation, enhancing the potential for robust, efficient communication technologies within complex optical systems.