Abstract

Open-winding permanent-magnet synchronous motors feature flexible control and a high fault-tolerance capability, making them widely used in high-reliability and high-power scenarios such as military equipment and electric locomotives. To address the issues that traditional model predictive control fails to balance, such as zero-sequence current suppression, system loss optimization and the reliance of weight parameter design on experience (with online optimization consuming excessive resources), this paper proposes an OW-PMSM MPC strategy for loss optimization and a weight design method based on a residual neural network. Specifically, the former strategy adds a zero-sequence current suppression term and a loss quantification term to the MPC cost function, enabling coordinated control of the two objectives; the latter establishes a mapping between weight parameters and motor performance via ResNet (which avoids the gradient vanishing problem in deep networks) and outputs optimal weight parameters offline to save online computing resources. Comparative experiments under two operating conditions show that the improved MPC strategy reduces system loss by 25%, while the ResNet-based weight design improves the performance of the drive system by 30%, fully verifying the effectiveness of the proposed methods.

1. Introduction

The open-winding permanent-magnet synchronous motor (OW-PMSM) has attracted extensive attention from industry and academia because of its high efficiency, high power density, excellent torque performance and other advantages [1]. Different from the traditional permanent-magnet synchronous motor, the OW-PMSM cancels the original neutral point. Therefore, the OW-PMSM has been widely used in electric vehicles, high-power electric propulsion and aircraft starter generator systems [2,3]. At present, the OW-PMSM has different bus power supply modes, which can be divided into common DC bus type, isolated DC bus type and hybrid power supply type. Among them, the common DC bus-type OW-PMSM drive system has become the most commonly used topology because of its low cost and high integration [4]. The open-winding motor dual-inverter structure increases the system capacity but at the same time increases the OW-PMSM loss and inverter loss [5]. Due to the existence of a zero-sequence circuit, the common bus line leads to the generation of a zero-sequence current. Therefore, in the industrial application of OW-PMSM drive systems, it is necessary to adopt a control strategy with a multi-objective constraint ability to optimize the zero-sequence current and system loss of the OW-PMSM drive system, so as to ensure the advantages of low cost and high power of the OW-PMSM drive system. Model predictive control is widely used in industrial applications because of its simple structure, strong nonlinear processing ability and simplicity and flexibility of multi-objective constraints [6]. Among them, model predictive torque control (MPTC) can accurately track the torque and flux output, with a high dynamic response [7]. When the constraints of torque, flux, zero-sequence current and loss are added, it is difficult to design the weight parameters corresponding to different dimensional variables, and it is also a research hotspot in the optimization of model predictive torque control.

At present, the minimum loss control strategy mainly includes the search method and the minimum loss model method based on iron loss [8]. The search method has the advantages of good robustness and high optimization accuracy, but its convergence speed is slow, and it will cause torque fluctuation within a certain regulation range [9]. Based on minimal iron loss, the mathematical model of the optimal motor efficiency is established, and the stator d-axis current or the initial stator flux amplitude is determined by the extremum method. In reference [10], the PMSM model considering iron loss is further given. Compared with the control mode with id = 0, the efficiency of the motor in high-speed and light load operation is significantly optimized.

For the weight parameter design of MPTC, reference [11] normalizes the cost terms of torque and flux in the cost function of the MPTC control algorithm and takes the change rate as the cost term to complete the weight setting. Reference [12] proposed using the particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize weight parameters online, which not only solved the problem of setting weight parameters but also reduced the total harmonic distortion rate. The literature [13,14] proposes a method combining pseudo-3D space vector modulation with sequential model predictive control. This method involves two stages: in the first stage, it screens the optimal vector group for zero-axis current tracking; in the second stage, it optimizes the dq-axis currents, ultimately achieving the elimination of weighting factors and an improvement in current quality. Reference [15] applies the online neural network to optimize the weight parameters to minimize the hidden layer of the neural network to reduce the amount of calculation. Reference [16] used an offline neural network to optimize the predictive control weight parameters of induction motors, significantly improving overall performance.

In recent years, artificial neural networks have developed rapidly. Reference [17] applies offline neural networks to optimize weights, which does not take up algorithm computation time and can significantly improve the effectiveness of weight parameter design. However, traditional neural networks are prone to problems such as gradient vanishing, leading to a decrease in effectiveness. The development of residual neural networks (ResNets) has brought about a series of breakthroughs in fields such as image recognition, short-term load forecasting in power systems, gearbox fault diagnosis and motor temperature [18]. ResNet uses identity shortcuts to alleviate the difficulty of parameter optimization in deep neural networks in order to avoid problems such as gradient vanishing.

Existing research either focuses on the single-dimensional optimization of current control while neglecting system losses or lacks adaptive design for practical driving scenarios for low-power hybrid inverter topologies or lacks matching between motor structures and control strategies. These areas provide clear exploration space for this study.

To sum up, the OW-PMSM system increases the capacity of the traditional permanent-magnet synchronous motor drive system and has a more flexible control method, but due to its special structure, the system loss becomes larger, so the MPTC with multi-objective constraint ability can be used to drive the OW-PMSM to optimize the system loss. In order to avoid the system jitter caused by the search method in loss optimization, this paper uses the method of establishing the mathematical model of iron loss resistance and uses the same variable to express the switching loss and the OW-PMSM loss, so as to carry out the constraint optimization. Among the methods for designing the weight parameters of variables corresponding to different dimensions, the online weight calculation method has high accuracy, but it consumes a lot of MPTC online computing resources. Using the WWF method, when MPTC constrains many targets, it can easily lead to a linear increase in algorithm complexity and reduce the efficiency of the control strategy. Therefore, this article adopts the method of ResNet to design the weights of variables corresponding to multiple different scales. Offline training of the ResNet can design MPTC weight parameters without occupying MPTC computing resources. The system loss optimization and weight parameter design can ensure the operation performance of the OW-PMSM drive system and further improve the efficiency of the OW-PMSM drive system and control algorithm under the premises of low cost and small volume.

The main content of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 establishes the mathematical model of the OW-PMSM and the loss model of the inverter, laying a foundation for the subsequent research. Building on the work in Section 2, Section 3 derives the system loss model of the OW-PMSM and proposes an optimized model predictive torque control (MPTC) strategy that suppresses zero-sequence current and balances torque error with system loss. To address the difficulty in tuning weight parameters in the control strategy, Section 4 proposes the application of offline training using a residual network (ResNet). This training process outputs a mapping database between weight parameters and system output performance, providing a method for deploying the control strategy in a digital controller. Section 5 conducts full-system experimental validation to verify the effectiveness of the proposed control strategy in the OW-PMSM control system.

2. Mathematical Model of the OW-PMSM Drive System

2.1. Mathematical Model of the OW-PMSM

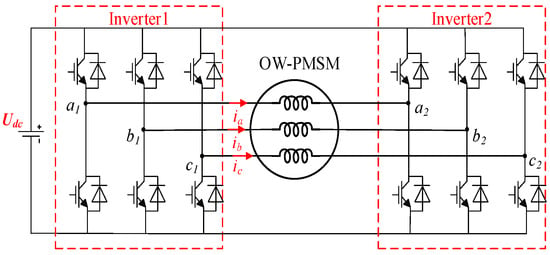

This study adopts a dual-inverter common DC bus topology. Its essence lies in establishing a topological symmetry benchmark by ensuring consistent hardware parameters of the two inverters and providing an equal-magnitude DC bus voltage supply—and this benchmark serves as the prerequisite for the open-winding motor to achieve symmetric voltage vector synthesis. The topology of a common DC bus-type OW-PMSM is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Topology of common DC bus-type OW-PMSM.

Due to the existence of a zero-sequence current, it is necessary to consider not only the dq-axis component but also the 0-axis component when establishing the drive model of the OW-PMSM.

The models established in this article are all based on the dq-axis coordinate system. The mathematical model [14] of the common DC bus type OW-PMSM is as follows:

where ux and ix (x = d, q, 0) are dq0-axis voltage and current; u0 and i0 are zero-sequence voltage and zero-sequence current: R is the stator resistance; L is stator inductance; ωe is motor electrical angular velocity; θe is motor electrical angle; ψf and ψf3 are fundamental and third harmonic amplitude of permanent-magnet flux linkage, respectively.

The flux linkage equation of OW-PMSM in dq0 coordinate system is as follows:

where ψx (x = d, q, 0) represents the dq0-axis flux linkage; L0 is the 0-axis equivalent inductance, and the 0-axis equivalent inductance is calculated as L0 = L − 2M; M is mutual inductance. For the surface mounted motor studied in this paper, the torque equation of the OW-PMSM in the dq0 coordinate system can be simplified as follows:

where Te is the torque of the motor, and Pn is the number of motor poles.

2.2. Inverter Loss Model

In low-loss occasions such as electric doors and small drive systems, the inverter efficiency can reach more than 90%, but for drive systems with high energy requirements, the inverter loss needs to be taken into account.

To better understand the inverter loss model, the mathematical model of the two-level three-phase power supply inverter used in this article is first presented. Taking one side inverter as an example, its mathematical model is established through the switch function method. The bridge arms of the three-phase inverter are defined as three phases: a, b and c. When the upper bridge arm is conducting, the switch function Sx = 1 (x = a, b, c), and when the lower bridge arm is conducting, Sx = 0. Therefore, the single-phase voltage on one side is expressed as follows:

Among them, Va, Vb, Vc are the three-phase phase voltages, and Udc is the DC bus voltage.

Assuming that the losses of IGBT on and off are Eon and Eoff, respectively, the size of the switching loss depends on the current at the time of IGBT on and off, and the expression of switching loss is as follows [19]:

where PINV is the loss of the inverter; VDC is the DC voltage at the input side of the inverter, and is the reference voltage of the IGBT, which can be found in the corresponding data book. Eon(|(i(k))|) and Eoff(|(i(k))|) are the on and off losses of the IGBT at the current value at time k, and f is the current frequency. When k is large enough, the switching loss can be expressed in the form of an integral:

where fsw is the switching frequency; ΔEon and ΔEoff are the turn-on and turn-off losses of IGBT under unit current, respectively. The specific values can be queried in the data book. Im is the output current amplitude of the inverter; θ is the voltage angle, and φ is the power factor angle.

3. Loss Optimization of the OW-PMSM System

3.1. MPTC Strategy Considering Loss of the OW-PMSM

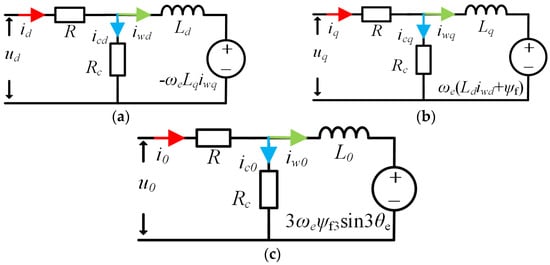

In order to optimize the motor loss combined with MPTC, the loss of the OW-PMSM drive system is analyzed. Similar to the traditional PMSM, its loss is composed of the following parts: copper loss, iron loss, mechanical loss and stray loss. To improve the operation performance of the motor, it is necessary to reduce the loss during the operation of the motor. In actual motor operation, mechanical loss and stray loss account for a relatively small proportion, and it is difficult to establish an accurate mathematical model for the two. They are usually ignored, and copper loss and iron loss are the main research objects. A loss model for the OW-PMSM is established in a two-phase rotating coordinate system. A reliable loss model for the OW-PMSM has been proposed and verified in paper [20], as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Equivalent loss circuit of OW-PMSM: (a) d-axis; (b) q-axis; (c) 0-axis.

In Figure 2, Rc is the equivalent iron loss resistance; iwd, iwq, iw0 are the active power components of the dq0-axis stator current; icd, icq, ic0 are the iron loss components of the dq0-axis stator current. The motor equation under the OW-PMSM loss model can be expressed as follows:

Based on Kirchhoff’s current law, the relationship between currents can be deduced as follows:

Based on Kirchhoff’s voltage law, the voltage relationship can be deduced as follows:

Combining Equations (8) and (9), it can be obtained that id, iq and i0 are expressed in iwd and iwq:

Based on this, the electromagnetic torque based on the loss model can be expressed as follows:

According to the loss model in Figure 2, the copper and iron losses of the OW-PMSM can be expressed as follows:

Among them, Ploss is the sum of the iron and copper consumptions of the motor; PCu is the copper consumption of the motor, and PFe is the iron consumption of the motor.

For the common DC bus-type OW-PMSM, the zero-sequence current must be suppressed before studying its control strategy, so its proportion in the loss can be ignored. In combination with Equations (8), (10) and (11), the steady-state motor loss equation containing only the effective component iwd of the stator current can be derived; that is, the differential term is 0, Ld = Lq = L. After simplification, it can be expressed as follows:

To sum up, the loss of the OW-PMSM can be mathematically expressed by Equation (13), and the numerical value is substituted into the MPTC cost function as the constraint to obtain the MPTC strategy for optimizing the loss of the OW-PMSM.

3.2. MPTC Strategy Considering Switching Loss

The inverter loss model in Section 2.2 can accurately calculate the switching loss. Since the opening and loss of power of electronic devices are not linear processes, involving more integral operations, it is very time consuming. However, the actual calculation does not pay much attention to the nonlinearity of switching elements, and the main concern is to accurately represent the conduction loss of the inverter. Based on this, the linear segmentation method is used to establish the inverter model in reference [19], and the correctness of the proposed model is verified by simulation and experiment. Taking the opening of the IGBT as an example, it can be simplified into two stages:

In the first stage, the collector–emitter voltage is maintained at the bus voltage UDC Uudelt, and the current rises linearly to the stable load current value.

In the second stage, the collector–emitter voltage drops to the on-state voltage instantaneously, and the current remains unchanged.

For the FGH60N60SMD model IGBT used in this paper, based on its official data book, the above parameters were fitted. Under the working condition of 50–100 °C, the on-state voltage and on-state resistance of the IGBT were 0.73 v and 0.00263 Ω, respectively.

Since the voltage current characteristic is still nonlinear at the subsection, the inverter loss needs to be analyzed and deduced in the three-phase static coordinate system.

In order to further study the power loss of the system, the park transformation adopted in this paper is equal power transformation. The power is equal in different coordinate systems, and the impedance value remains unchanged [21]. Therefore, the loss of the IGBT in on-state resistance is as follows:

where PinvRon is the power consumed by the switching device with the on-state resistance, and the loss is multiplied by 2 because the OW-PMSM drive system has two groups of inverters. The power PinvUon consumed by the on-state voltage drop is as follows:

where , , are the average values of absolute values of the phase current at steady state.

is is expressed by Iwd and iwq:

By combining Equations (14), (16) and (17), the on-state loss of the inverter can be solved, and iwq is replaced by electromagnetic torque through Equation (11), so that there is only one unknown iwd in the whole equation:

To sum up, the system switching loss can be mathematically expressed by Equation (18), and the value is substituted into the MPTC cost function as a constraint to obtain the MPTC strategy for system switching loss optimization.

3.3. MPTC Strategy Considering System Loss of the OW-PMSM

By analyzing the loss of the OW-PMSM and inverter, the copper loss, iron loss and inverter loss of the drive system of the OW-PMSM can be expressed by iwd, and the loss of OW-PMSM system can be expressed as follows:

where POW-PMSM is the total loss of the OW-PMSM drive system; that is, the sum of the OW-PMSM loss and the inverter loss. When the system is stable, ωe and Te are constant. At this time, the motor loss is only related to iwd. The zero point can be derived from it to obtain the minimum value of the OW-PMSM loss; that is, the corresponding iwd is as follows:

iwd, i0 can be discretized by a first-order forward Euler, and iwd, i0 prediction value can be obtained as follows:

where Ts is the sampling period; iwd(k), i0(k) are the active current values at the current time; iwd(k + 1), i0(k + 1) are the active current values at the next time; udq(k) is the d-q equivalent voltage at the current time; udq(k + 1) is the d-q equivalent voltage at the next time; idq(k) is the d-q equivalent current value at the current time, and idq(k) is the dq-axis equivalent current value at the next time. Based on Equations (20) and (21), the expected values and predicted values of iwd and i0 can be obtained. Due to the delay in the actual system, it is necessary to compensate for the predicted variable with one beat; that is, the time k + 2 is the final predicted value, as shown in Equation (22).

Due to the shared DC circuit of the common bus-type OW-PMSM, there is a zero-sequence circuit, and it is necessary to suppress the zero-sequence current. Based on the previous section, the OW-PMSM driving system improves the MPTC cost function and compensates for one beat delay with the following expression:

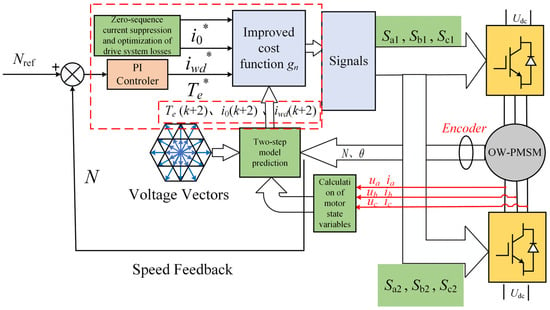

where λ0 is the zero-sequence current constraint term, and λloss is the weight of the loss constraint term. Since the constraint values of the effective component iwd of stator current and electromagnetic torque already exist in the cost function, the original flux constraint term can be canceled. The optimized MPTC (OPT-MPTC) block diagram is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of OPT-MPTC.

According to Figure 3, the OPT-MPTC control strategy can be briefly described as follows: the expected torque value is given by the speed outer loop PI controller; the expected value of zero-sequence current suppression is set to 0, and the expected value of the active current component iwd is set to the calculation result as shown in Equation (22). At the same time, the three-phase current, motor speed value and motor rotor position of the motor at that time (recorded as time k) can be obtained through the current and speed sensors. The current value in the two-phase rotating coordinate system at time k can be obtained through coordinate transformation. Combined with the voltage and speed at time k, the current value at time k + 1 can be deduced. Based on this, the predicted values of the three (at time k + 1) can be calculated by successively bringing eight voltage vectors (six non-zero vectors and two zero vectors) into the prediction equation of electromagnetic torque Te, zero-sequence current i0 and active current iwd. By inputting the predicted and expected values into the OPT-MPTC cost function and selecting the voltage vector corresponding to the minimum cost function value, the optimal voltage vector can be output.

In summary, the advantage of the OPT-MPTC proposed in this paper over the traditional MPTC, which only considers torque ripple and flux linkage tracking, lies in the following aspects: based on the special structure of the OW-PMSM, the introduction of a zero-sequence current constraint term reduces system fluctuations and losses caused by the zero-sequence current; the system losses of the OW-PMSM, including copper and iron losses of the OW-PMSM itself and losses of the dual-inverter group, are considered and expressed in terms of unique variables incorporated into the cost function to optimize the overall system losses.

4. Weight Parameter Design of Model Predictive Torque Control for the OW-PMSM System Based on a Back Propagation Neural Network

In Section 3, the zero-sequence current and system loss of the OW-PMSM system are constrained by the OPT-MPTC cost function to further improve the performance of the drive system. However, there are three variables of different dimensions in Equation (22), and the selection of their corresponding weights λTe, λ0, λloss plays a key role in the output performance of the system. Therefore, this section uses the ResNet method to design the weight parameters of the OW-PMSM system model predictive torque control.

4.1. ResNet Design

ResNet is a deep neural network architecture proposed in 2015, which introduces the idea of residual learning and effectively solves the problems of gradient vanishing and network degradation in deep neural network training through skip connections. Compared with traditional neural networks, it effectively solves problems such as gradient vanishing, network depth limitations and difficulty in parameter optimization. The basic principles of ResNet can be found in reference [22] and will not be elaborated in this article.

To facilitate the collection of data and the selection of neural networks, an evaluation index function is designed as a measure of optimal weights, as well as a measure of the performance of the system output. In this article, the evaluation function can be set as a combination of torque ripple, zero-sequence current and drive system losses:

Among them, α1, α2, α3 are the torque error, zero-sequence current and the loss coefficient of the motor drive system in the evaluation function, respectively, and their size depends on the emphasis on the motor drive system. For example, if the user requires a smaller output performance loss for the OW-PMSM, the proportion of α3 in the formula can be increased. Depending on the actual working conditions, the combination of model predictive control weight parameters corresponding to the required working conditions can be selected at any time.

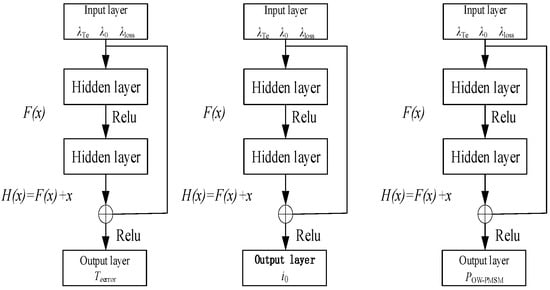

The basic network structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ResNet basic structure.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the ResNet model constructed in this study takes three core weight parameters in the OPT-MPC cost function as inputs, specifically the λTe, λ0 and λloss. The hidden layer of the network consists of three stacked “Residual Blocks”, each following the design philosophy of “residual learning”—instead of directly learning the target mapping H(x), it learns the “residual mapping” F(x) = H(x) − x between the input x and the target mapping. Its core operation is expressed as follows:

where x and y are the input and output vectors of the residual block, respectively, and F(x, {Wi}) represents the transformation of weighted layers in the “convolution-batch normalization-ReLU” double-layer structure within the residual block. The “Skip Connection” directly performs element-wise addition of the input x and the output of F(x, {Wi}). This design allows gradients to flow back directly through the skip connection during backpropagation, effectively alleviating the “vanishing gradient problem” and ensuring stable training and convergence of the ResNet model in this study.

The output layer of the ResNet targets three key performance indicators of the motor: Teerror, i0 and POW-PMSM. Through an end-to-end learning framework, this model can efficiently fit the implicit coupling law between weight parameters and performance indicators, replacing the high-computational-cost iterative process of “parameter adjustment-performance verification” in traditional trial-and-error methods or numerical optimization.

After model training, it traverses a predefined refined weight space for each weight combination in real time. These values are then substituted into Equation (23) to calculate the minimum f value. The corresponding weight parameters are the optimal solution for the current operating condition. This design provides a dynamically adaptive parameter configuration scheme for the MPC controller, ultimately achieving coordinated optimization of motor control accuracy and operational efficiency.

4.2. Weight Parameter Design Method

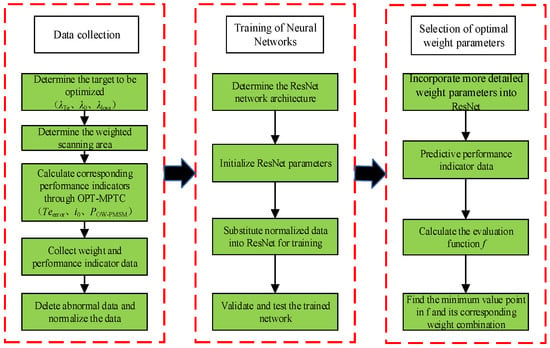

The weight parameter design based on ResNet can be divided into three steps: designing corresponding evaluation index functions and collecting training data, designing neural network architecture and conducting training and selecting the optimal weight parameter combination based on the evaluation function.

The weight parameter design diagram based on ResNet is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Design block diagram of weight parameters based on ResNet.

As shown in Figure 5, the design process is as follows:

Data Collection: After the previous experimental test, the motor data such as torque, speed, zero-sequence current and drive system loss obtained based on the MATLAB/Simulink 2022b simulation platform are similar to the actual motor test bench test data. Considering the frequent change of weight parameters and the loss of the motor bench caused by long-time operation, the training data in this paper were collected through the MATLAB/Simulink simulation platform, which can change the simulation parameters at any time and repeat a large number of long-time experiments, greatly reducing the difficulty of obtaining training data. In this paper, the OPT-MPTC cost function is shown in Equation (22). The trained network takes weights (λTe, λ0, λloss) as inputs and performance indicators (Teerror, i0, POW-PMSM) as outputs. In order to ensure the representativeness of the trained weight parameter combinations, simulation data collection was conducted under the operating conditions of traversing the rated torque and rated speed range. After simulation and experimentation, the weight parameter scanning area for stable motor startup was determined as follows: λTe ranging from 7 to 15, step size of 0.32; λ0 ranging from 800 to 10,000, step size of 368, and λoss ranging from 0.125 to 1, step size of 0.035. Traversing each weight parameter change value under each operating condition one by one, a data sample of 15,625 can be obtained. The setting of the step size is to ensure the alignment of data dimensions and is determined through multiple debugging. The function values of Teerror, i0 and POW-PMSM are automatically calculated during the simulation process. After the simulation, the data is exported; the abnormal data is screened and normalized, and then the network training can be carried out.

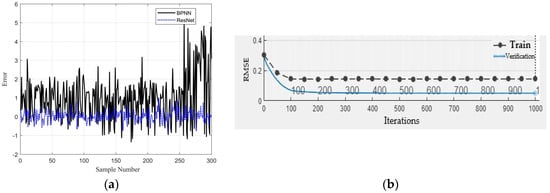

ResNet training: Firstly, the data set is divided into training set, cross validation set and test set, accounting for 70%, 15% and 15%, respectively. According to the number of inputs and outputs of the data set, and the output neurons are the performance indicators of individual motors, namely, Teerror, i0, POW-PMSM. The number of output neurons is set to 1. After initialization is complete, the residual block is set to 5, the number of iterations to 1000, the initial learning rate to 0.0003 and the single-layer neurons to 64. The matching between the feature dimension of the ResNet input layer and the weight parameters adheres to a direct correspondence principle: the input layer is configured with three neurons, each respectively associated with the three to-be-optimized weight parameters λTe, λ0 and λloss, thus rendering the input feature dimension strictly 3. In practical input scenarios, each set of weight parameters is converted into a three-dimensional vector in the form of [λTe λ0 λloss], which is directly fed into the subsequent five residual blocks via the input layer neurons for feature extraction. This design ensures accurate mapping between weight parameters and input features, laying a solid foundation for the network to learn the correlation between “weight parameters → motor performance indicators.” The Adam optimizer is used to complete the process, and then the ResNet training is started. Finally, the ResNet that has completed training is verified by training and prediction. If it is confirmed that the prediction accuracy meets the required requirements, the OPT-MPTC weight design based on OW-PMSM can be started. Otherwise, it is necessary to continue training until the conditions are met. This article introduces a comparison of prediction performance between traditional back propagation neural networks (BPNNs) and the ResNet, in which the BPNN and ResNet maintain consistent training parameters such as iteration times. Taking the training of zero-sequence current output performance as an example, the following figure shows the training error results of the ResNet and BPNN, as well as the RMSE results of ResNet training, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Training results: (a) training error results of ResNet and BPNN; (b) RMSE of ResNet training output.

As shown in Figure 6a, the error of ResNet fluctuates within the range of [−0.5, 0.5], while the error of BPNN fluctuates within the range of [−0.5, 3]. In this case, the accuracy of ResNet is improved by 28% compared with that of BPNN, indicating the effectiveness of ResNet prediction. The training set had an initial RMSE of approximately 0.35, which dropped rapidly to 0.15 around the 100th iteration and remained stable in subsequent iterations. The validation set also had an initial RMSE of about 0.35, decreasing to 0.1 around the 200th iteration and staying stable afterward. The overall trend of the validation set was consistent with that of the training set, indicating no overfitting of the model and excellent generalization ability. Eventually, the training set stabilized at an RMSE of 0.15, while the validation set stabilized at 0.1. Both maintained low error levels with no significant increase in the later iterations, demonstrating high prediction accuracy of the model in both training and validation phases, as well as a stable and reliable training process. The model’s fast convergence and low, stable error indicate that the ResNet can effectively learn the mapping relationship between weight parameters and motor performance, which provides a guarantee for generating a high-precision weight database through subsequent offline training and further supports the multi-objective optimization performance of the OPT-MPTC during online table lookup.

Selection of optimal weight parameters: The ResNet that has been trained and meets the requirements is derived as a separate model, and a more detailed combination of weight parameters—λTe from 7 to 15 in steps of 0.004, λ0 from 800 to 10,000 in steps of 4.6 and λloss from 0.125 to 1 in steps of 0.00044—is brought into ResNet for prediction. In order to ensure the balanced performance of the motor, α1, α2 and α3 are set to 100, 100 and 1, respectively, and the main performance indicators of the motor torque error, zero-sequence current and loss value range of the motor drive system are set to 0–100. The predicted motor performance indexes are added as shown in Equation (23), and the weight parameter combination corresponding to the minimum value of the performance function is the optimal weight parameter.

5. Comparative Experimental Verification

5.1. Loss Comparison of the OW-PMSM System Between Traditional MPTC and OPT-MPTC

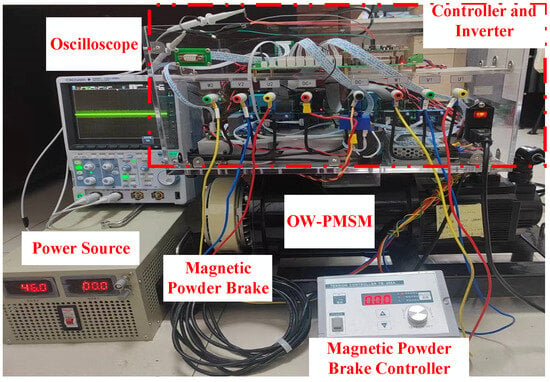

In order to verify the effectiveness of the above OPT-MPTC strategy, this section carries out experimental verification with zero-sequence current, motor loss, inverter loss and motor comprehensive performance indicators. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 7. It includes a control board with TMS320F28335 as the main controller, a dual-inverter group, a 300 V DC power supply, an oscilloscope, a 1.5 Kw OW-PMSM and a magnetic powder brake.

Figure 7.

Experimental platform of OW-PMSM.

The motor model parameters are shown in Table 1. The comparative working condition is 1000 r·min−1, and the load torque is 3 N·m.

Table 1.

Motor parameters of OW-PMSM.

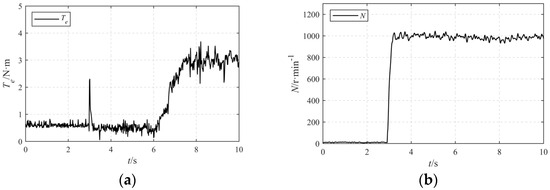

In Figure 8a, the electromagnetic torque Te maintains a stable state over the interval of 0–3 s, and after load application at 6 s, it rises rapidly to fluctuate within the range of 3–3.5 N·m. In Figure 8b, the rotational speed N remains at 0 r·min−1 from 0 to 3 s, rises sharply after 3 s, reaches approximately 1000 r·min−1 at around 4 s, experiences a slight decrease during load application at 6 s and ultimately achieves a steady state at approximately 8 s. To verify the zero-sequence current suppression effect of the OPT-MPTC under steady-state conditions, the traditional MPTC and the OPT-MPTC were compared and validated under the same operating conditions.

Figure 8.

Motor torque and speed diagram: (a) speed; (b) torque.

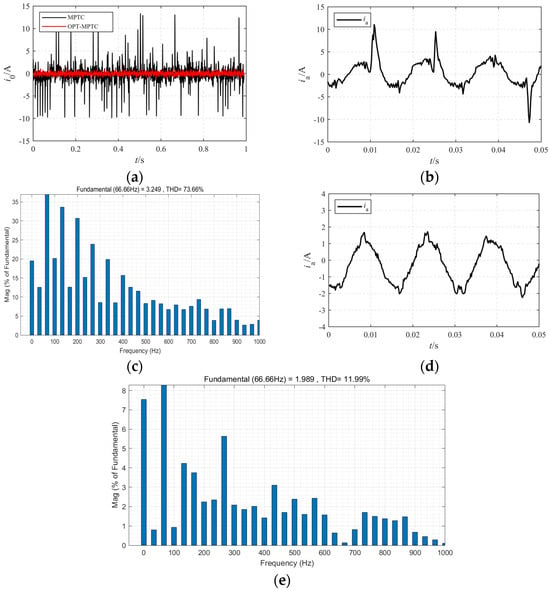

As can be seen from Figure 9 below, the zero-sequence current of the system under OPT-MPTC can be basically suppressed to 0 A, whereas the amplitude of the zero-sequence current under the traditional MPTC strategy can reach over 10 A. A comparative analysis of the phase current waveform quality of the OW-PMSM shows that the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the phase current under the traditional MPTC strategy is as high as 73.66%. In contrast, the THD of the phase current under the OPT-MPTC strategy can be reduced to 11.99%, exhibiting a significant improvement.

Figure 9.

Comparison of zero-sequence current and A-phase current FFT under traditional MPTC and OPT-MPTC: (a) comparison of zero-sequence current; (b) MPTC-driven A-phase current of OW-PMSM; (c) FFT analysis of A-phase current driven by MPTC; (d) OPT-MPTC-driven OW-PMSM A-phase current; (e) FFT analysis of A-phase current driven by OPT-MPTC.

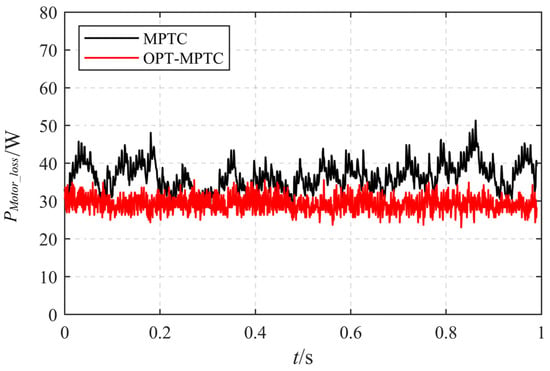

As shown in Figure 10, for the traditional MPTC strategy, the motor power loss fluctuates significantly within the range of 30–50 W during the interval of 0–1 s, with an average value of 40 W. In contrast, when the OPT-MPTC strategy is adopted, the power loss is stably maintained around 30 W with extremely minimal fluctuations. The OPT-MPTC control strategy can be optimized by nearly 10 W compared with the traditional MPTC, and the loss is reduced by 25%. The inverter loss comparison experiment is carried out. Since the inverter loss is small, the calculation method of average loss per unit time is adopted for comparative experiments, and its value is shown in Table 2.

Figure 10.

Motor loss.

Table 2.

Average loss of inverter per unit time.

To determine the loss of the OW-PMSM driven by the OPT-MPTC and the MPTC, a comparison is shown in Figure 10.

As shown in the table above, OPT-MPTC reduces the inverter loss by about 18% compared with MPTC in actual operation. After the comparison experiment of OW-PMSM loss and inverter loss is completed, the comparison experiment of OW-PMSM system loss is further compared.

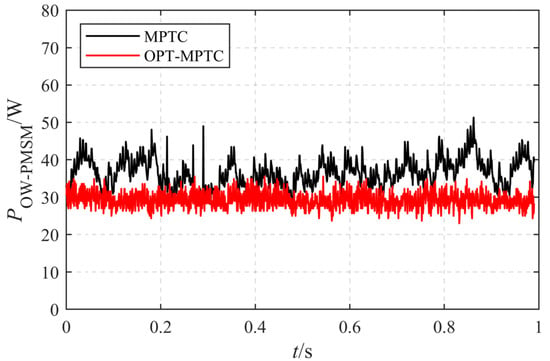

Since the inverter loss is small, the system loss diagram is basically consistent with the loss of the OW-PMSM. As shown in Figure 11, the OPT-MPTC control strategy can reduce the loss by 25% compared with the traditional MPTC.

Figure 11.

System loss of OW-PMSM.

To sum up, the experiment proves that the improved cost function can reduce the zero-sequence current and drive system loss in the actual experiment.

5.2. Comparison with WWF Weight Parameter Design Method

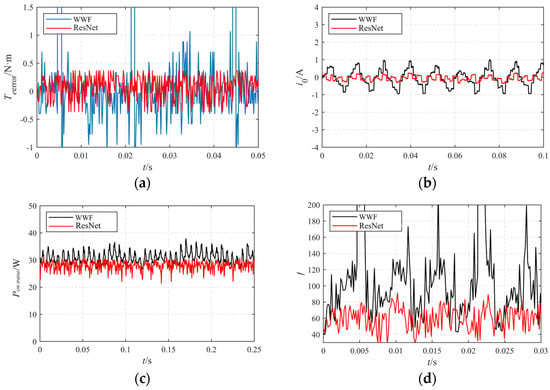

In order to verify the effectiveness of the weight design based on ResNet proposed by the OW-PMSM in actual working conditions, this paper conducts experimental comparison with WWF control strategy, which is mentioned in [23], and compares the output torque ripple, drive system loss and zero-sequence current of the drive system under steady-state conditions, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Output performance of OW-PMSM: (a) torque ripple; (b) system loss; (c) zero-sequence current; (d) comprehensive evaluation function.

It can be observed from Figure 12 that the difference in the torque ripple between the two optimization strategies is not significant. However, the WWF strategy is prone to abnormal fluctuations with a fluctuation amplitude exceeding 1 N·m, whereas under the ResNet-based strategy, the torque fluctuation is below 0.5 N·m. Regarding the zero-sequence current, the WWF strategy results in a fluctuation amplitude of approximately 1 A, while the zero-sequence current under the ResNet strategy is basically 0 A. In terms of drive system loss, the loss is approximately 35 W for the WWF strategy, while it is below 30 W for the ResNet strategy. For the comprehensive performance evaluation index, the WWF strategy has an average value of approximately 100, while the ResNet strategy has an average value of approximately 70, exhibiting stronger comprehensive optimization performance and ensuring higher system stability. Compared with the WWF strategy, the ResNet strategy can improve the comprehensive performance of the system by approximately 30%.

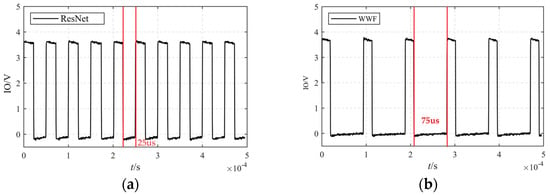

Because the weightless design method uses the method of splitting the cost function, the algorithm efficiency is relatively low when there are many optimization objectives. The efficiency of the two algorithms is verified by the three optimization objectives in this paper. In this experiment, the time of an algorithm cycle is calculated by the high–low level jump of the I/O port; that is, the I/O port outputs a low level at the entrance of the control function, and the I/O port outputs a high level at the end of the control function. As for TMSF28335, the low-level voltage is 0 V, and the high-level voltage is 3.3 V. To sum up, the operation efficiency can be obtained by comparing the low-level duration of the I/O port, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Algorithm cycle: (a) calculation period of weight parameter design method based on ResNet; (b) calculation period of weight parameter design method based on WWF.

As shown in Figure 13, the cycle of weight parameter design method based on ResNet is about 25 μs, while the cycle of WWF optimization method is about 75 μs. It can be seen that the efficiency of the weight parameter design algorithm based on ResNet is about three times that of the WWF strategy.

To sum up, the experiment verifies the effectiveness of the weight parameter design method based on ResNet proposed in this paper, improves the control performance of the OPT-MPTC and improves the weight design efficiency of the OPT-MPTC.

6. System Performance Verification Under Different Working Conditions

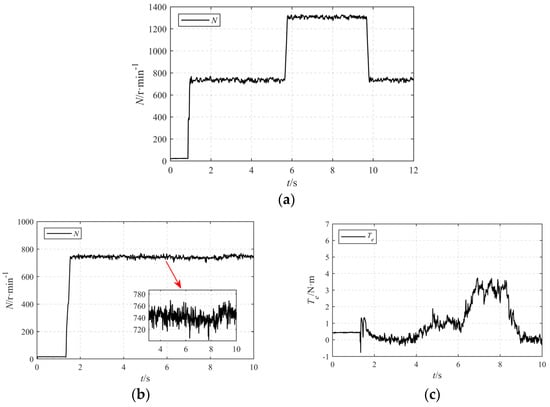

Experiments on acceleration, deceleration, load increase and load decrease were conducted on the OW-PMSM to verify the dynamic stability performance and robustness of the proposed control strategy. Specifically, the acceleration and deceleration process is as follows: the OW-PMSM is controlled to start at an initial speed of 750 r·min−1; after reaching a stable state, it accelerates to 1300 r·min−1; once stabilized again, it decelerates back to 750 r·min−1. For the load increase and decrease process: the OW-PMSM is driven to start at 750 r·min−1; after stabilization, the load torque is increased to 1 N·m; upon re-stabilization, it is further increased to 3 N·m; finally, after achieving stability again, the load is gradually reduced to 0 N·m. The speed–torque diagrams for verifying the dynamic response are presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Dynamic acceleration/deceleration and loading/unloading experiment. (a) Speed curve of dynamic acceleration and deceleration experiment. (b) Velocity curve in loading and unloading experiments. (c) Torque curve in loading and unloading experiments.

As shown in Figure 14a, in the dynamic acceleration and deceleration experiment, the speed increased to 750 r·min−1 in response to the command at around 1 s, and after verifying its stable operation, it increased to 1300 r·min−1 in response to the command at around 5.8 s. After verifying its stable operation, the speed decreased to 750 r·min−1, completing the performance verification of OW-PMSM dynamic acceleration and deceleration under the control strategy proposed in this paper. As shown in Figure 14b,c, dynamic loading and unloading experiments were conducted after rising to 750 r·min−1 at around 1.5 s. After the speed reached the target value, the load torque was loaded to 1 N·m. After verifying its stable operation, the load torque was loaded to 3 N·m. It can be seen that there is a slight downward trend in the speed curve, and then it stabilizes. After verifying the stable operation of the load condition, the load torque was unloaded to 1 N·m, and the corresponding speed in the speed curve increased. This experiment can verify the stability of the control strategy proposed in this paper under the OW-PMSM dynamic loading and unloading condition.

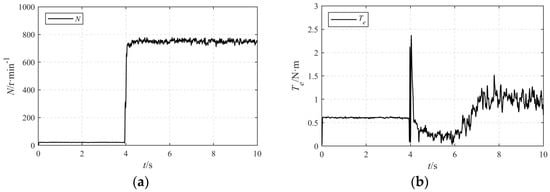

To further verify the effectiveness of the control strategy proposed in this article, after completing dynamic acceleration and deceleration and addition/subtraction experiments, system performance verification was carried out under four different stable operating conditions, namely, zero-sequence current output, system loss output and corresponding three-phase current output. The weight parameters designed for the operating conditions and the corresponding operating conditions are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Table of working conditions and weight parameters.

Condition 1 refers to a speed of 750 r·min−1 and a load torque of 1 N·m, with corresponding weight parameters of λTe = 14.564, λ0 = 4843.4, λloss = 0.1316. After stabilization, the system performance data is output.

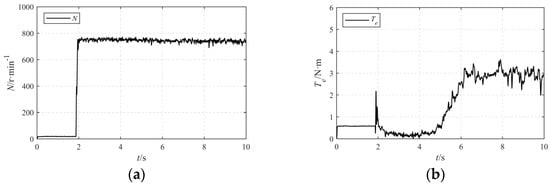

As can be seen from Figure 15, under this condition 1, the OW-PMSM has been verified to achieve fast startup, with smooth commutation and excellent steady-state performance. It can be observed that, under this operating condition, the OW-PMSM enables a dynamic acceleration of 750 r·min−1. With a load application of 1 N·m, the amplitude of the three-phase currents is approximately 0.8 A; the fluctuation range of the zero-sequence current is about 0.03 A, and the power loss of the OW-PMSM drive system is roughly 11 W. Thus the stability of the system is verified under this operating condition.

Figure 15.

Experimental verification condition 1: (a) speed; (b) torque; (c) current; (d) sero-sequence current; (e) system loss.

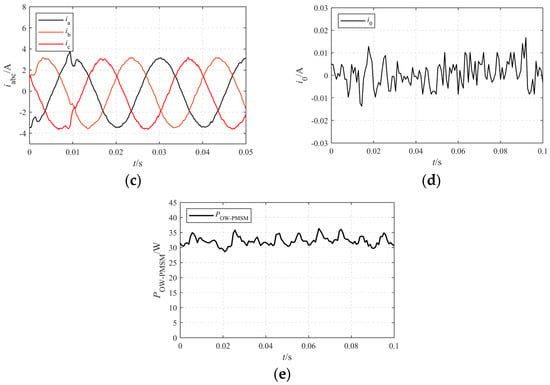

Condition 2 refers to a speed of 750 r·min−1 and a load torque of 3 N·m, with corresponding weight parameters of λTe = 13.756, λ0 = 6876.6, λloss = 0.4728. After stabilization, the system performance data is output.

As can be seen from Figure 16, under this condition 2, the OW-PMSM has been verified to achieve fast startup, with excellent steady-state performance. It can be observed that under this operating condition, the OW-PMSM enables a dynamic acceleration of 750 r·min−1. With a load application of 3 N·m, the amplitude of the three-phase currents is approximately 3 A, the fluctuation range of the zero-sequence current within 0.02 A, and the power loss of the OW-PMSM drive system is roughly 35 W. Verified the stability of the system under this operating condition.

Figure 16.

Experimental verification condition 2: (a) speed; (b) torque; (c) current; (d) zero-sequence current; (e) system loss.

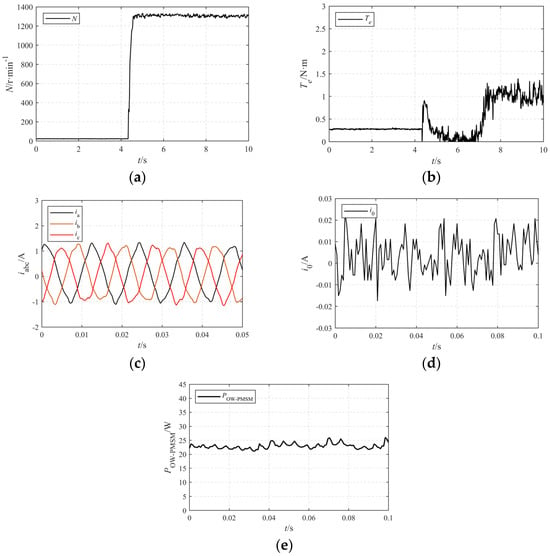

Condition 3 refers to a speed of 1300 r·min−1 and a load torque of 1 N·m, with corresponding weight parameters of λTe = 11.272, λ0 = 8873.0, λloss = 0.2514. After stabilization, the system performance data is output.

As can be seen from Figure 17, under condition 3, the OW-PMSM has been verified to achieve fast startup, with excellent steady-state performance. It can be observed that, under this operating condition, the OW-PMSM enables a dynamic acceleration of 1300 r·min−1. With a load application of 1 N·m, the amplitude of the three-phase currents is approximately 1.2 A; the fluctuation range of the zero-sequence current within 0.02 A, and the power loss of the OW-PMSM drive system is roughly 25 W. Thus the stability of the system under this operating condition is verified.

Figure 17.

Experimental verification condition 3: (a) speed; (b) torque; (c) current; (d) zero-sequence current; (e) system loss.

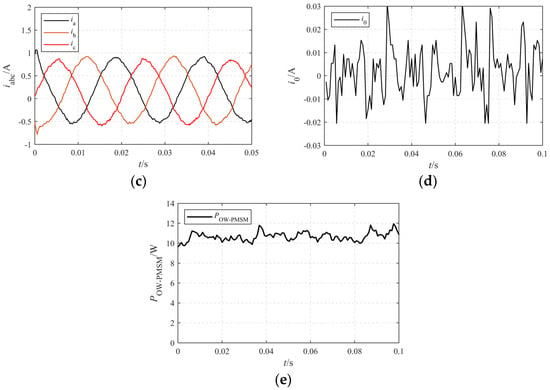

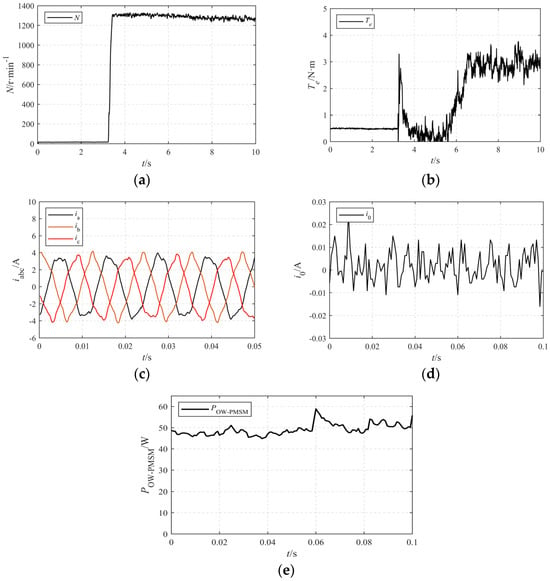

Condition 4 refers to a speed of 1300 r·min−1 and a load torque of 3 N·m, with corresponding weight parameters of λTe = 9.252, λ0 = 8799.4, λloss = 0.8534. After stabilization, the system performance data is output.

As can be seen from Figure 18, under this operating condition, the OW-PMSM has been verified to achieve fast startup, with smooth commutation and excellent steady-state performance. It can be observed that, under this operating condition, the OW-PMSM enables a dynamic acceleration of 1300 r·min−1. With a load application of 3 N·m, the amplitude of the three-phase currents is approximately 4.1 A; the fluctuation range of the zero-sequence current is about 0.02 A, and the power loss of the OW-PMSM drive system is roughly 50 W. Thus the stability of the system under this operating condition is verified.

Figure 18.

Experimental verification condition 4: (a) speed; (b) torque; (c) current; (d) zero-sequence current; (e) system loss.

In summary, the above content verifies the performance of the drive system under acceleration, deceleration, loading and unloading conditions, as well as four different operating conditions. In dynamic condition verification, the system speed and torque can quickly respond and stabilize according to the expected value. In the steady-state performance verification, the system performance metrics such as zero-sequence current, drive system loss and three-phase current were verified. Through the output performance parameters, it can be seen that the OW-PMSM system under the control strategy proposed in this paper has certain stability and robustness.

7. Conclusions

This study focuses on an OW-PMSM integrated with an MPTC. Firstly, to address the issue that the zero-sequence current of the OW-PMSM causes significant losses in the drive system, an OPT-MPTC strategy is proposed. Building upon the traditional MPTC cost function, this strategy incorporates both zero-sequence current constraints and loss constraints of the OW-PMSM drive system, thereby enhancing motor operational performance. Secondly, targeting the challenge of weight parameter design for the MPTC of OW-PMSMs, a ResNet-based weight parameter design method for the OPT-MPTC is developed on the basis of existing theoretical foundations. This method employs offline network training without occupying the real-time computational resources of the control algorithm. It integrates highly refined weight parameter combinations into the network for optimization, yielding the optimal weight parameter configuration and effectively improving the overall efficiency and performance of the OW-PMSM drive system. Finally, experimental studies are conducted to perform comprehensive comparative analyses and verifications between MPTC and OPT-MPTC, as well as between the WWF and the ResNet-based approach. The experimental results demonstrate that, compared with the traditional MPTC, the proposed OPT-MPTC can effectively suppress the zero-sequence current to below 0.04 A, reduce motor losses by approximately 25% and decrease average switching losses by around 18%; in contrast to the WWF strategy, the ResNet-based method enhances the overall system performance by 30% and improves the weight parameter design efficiency by roughly threefold. Additionally, the OW-PMSM drive system exhibits stable operation and rapid response under various operating conditions. In conclusion, the experimental results fully validate the effectiveness and practical application value of the proposed OPT-MPTC strategy and the ResNet-based weight parameter design method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.; Methodology, X.Z. and X.G.; Software, X.L.; Verification X.G. and R.Z.; Data organization, X.L.; Drafting the initial draft, X.Z.; Writing comments and editing, X.Z. and X.G.; Visualization, R.Z.; Supervision, X.L.; Master of project management, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lei, G.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y. Quasi-direct power control of dual-battery electric vehicle integrated charging system based on an open-winding motor. J. Electr. Technol. 2024, 39, 3007–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Lakhimsetty, S.; Somasekhar, V. An Open-End Winding BLDC Motor Drive with Fault Diagnosis and Auto reconfiguration. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 3723–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. A Simple Deadbeat Predictive Current Control for OW-PMSM Drives Based on Reference Voltage Redistribution. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 7362–7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welchko, B.; Nagashima, J. The influence of topology selection on the design of EV/HEV propulsion systems. IEEE Power Electron. Lett. 2003, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Dong, Y. Robust Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors Based on Improved Predictive Control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2025, 6, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, X.; He, M.; Xiao, D.; Wang, Z. A Universal Model Predictive Control Strategy for Dual Inverters Fed OW-PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 7575–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xia, C.; Chen, W. Modified predictive torque control for PMSM drives with parameter robustness. J. Electr. Eng. 2018, 33, 965–972. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Choi, J.W. MTPA Control Method for MIDP SPMSM Drive System Using Angle Difference Controller and P&O Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 15382–15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, A.; Zielonka, A.; Woźniak, M.; Orság, P.; Mlčák, T.; Hrabovský, L. Fuzzy control system to improve the efficiency of the brushless direct current motor by correcting the control angle. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 169, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, S.; Davari, S.; Naderi, P.; Garcia, C.; Rodriguez, J. Robust Loss Minimization for Predictive Direct Torque and Flux Control of an Induction Motor with Electrical Circuit Model. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 5417–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Ke, D. Weighting factors design of model predictive control for permanent magnet synchronous machine using particle swarm optimization. J. Electr. Eng. 2021, 36, 50–59, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Davari, S.; Nekoukar, V.; Garcia, C.; Rodriguez, J. Online Weighting Factor Optimization by Simplified Simulated Annealing for Finite Set Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, H. Two-vector-based model predictive torque control without weighting factors for induction motor drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gan, C.; Ni, K.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Qu, R. Improved Sequential Model Predictive Control of Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor with Pseudo 3-D Space Vector Modulation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 3896–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseiro, A.; Mendes, S.; Cruz, A. Dynamically weighted optimal switching vector model predictive control of power converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Xie, H.; Dragicevic, T.; Wang, F.; Rodriguez, J.; Blaabjerg, F. Optimal Cost Function Parameter Design in Predictive Torque Control (PTC) Using Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 7309–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, W.; Xiong, W.; Kennel, R. Predictive torque control of induction machines fed by 3L-NPC converters with online weighting factor adjustment using Fuzzy Logic. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 7–10 August 2017; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgässner, W.; Wallscheid, O.; Böcker, J. Estimating electric motor temperatures with deep residual machine learning. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 7480–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, S.; Krein, P.T. Minimization of System-Level Losses in VSI-Based Induction Motor Drives: Offline Strategies. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.F.; Xu, N.; Chu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.K.; Yang, Z.H. Control Strategy for an Open-End Winding Induction Motor Drive System for Dual-Power Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 8844–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, R.A.; Biswas, S.P.; Hosain, K.; Hossain, S.; Mondal, S.; Islam, R.; Fekih, A. Improved Switching Technique to Mitigate THD and Power Loss of NPC Inverters. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Garcia, C.; Mora, A.; Flores-Bahamonde, F.; Acuna, P.; Novak, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tarisciotti, L.; Davari, S.A.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Latest Advances of Model Predictive Control in Electrical Drives—Part I: Basic Concepts and Advanced Strategies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Ankam, S.; Hussein, L.; Durgadevi, G.; Arunachalam, P. Classifying Atrial Fibrillation Using Deep Residual Networks (ResNet) on ECG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology (ICICAT), Gorakhpur, India, 23–24 November 2024; pp. 1303–1307. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).