Abstract

In recent years, there has been growing interest in discrete probability distributions due to their ability to model the complex behavior of real-world count data. In this paper, a new discrete mixture distribution based on two Weibull components is introduced, constructed using the general discretization approach. Several important statistical properties of the proposed distribution, including the survival function, hazard rate function, alternative hazard rate function, moments, quantile function, and order statistics are derived. It was concluded from the descriptive measures that the discrete mixture of two Weibull distributions transitions from being positively skewed with heavy tails to a more symmetric and light-tailed form. This demonstrates the high flexibility of the discrete mixture of two Weibull distributions in capturing a wide range of shapes as its parameter values vary. Estimation of the parameters is performed via maximum likelihood under Type II censoring scheme. A simulation study assesses the performance of the maximum likelihood estimators. Furthermore, the applicability of the proposed distribution is demonstrated using two real-life datasets. In summary, this paper constructs the discrete mixture of two Weibull distributions, investigates its statistical characteristics, and estimates its parameters, demonstrating its flexibility and practical applicability. These results highlight its potential as a powerful tool for modeling complex discrete data.

1. Introduction

In recent years, discrete lifetime distributions have attracted considerable attention due to their suitability for modeling real-world data recorded on discrete scales. Discretization becomes essential when continuous lifetime distributions fail to provide adequate fit or when the data collection process yields discrete values such as cycles, shocks, or discrete time intervals; these situations are common in reliability and survival studies, where observations may be recorded in terms of cycles, shocks, or discrete events before system failure. Typical examples include the number of times an electrical device is switched on/off before failure, the number of voltage fluctuations that an electronic component can withstand, the number of completed cycles of equipment before failure or the number of cutouts produced by a stabilizer prior to deterioration.

Similar contexts arise in survival and medical studies; in survival analysis the survival function (sf) can be viewed as a function of discrete random variable (drv) that serves as a discrete analog of a continuous random variable (crv) or in which survival times are often recorded in days or weeks. For example, the length of stay in observation ward may be recorded in days or the survival time of the leukemia patients after therapy may be counted in days or weeks. These situations require statistical models that reflect the discrete nature of observed time, and accordingly, discrete analogs of continuous lifetime distributions have been proposed extensively in the literature.

Ref. [1] introduced the discrete Weibull (DW) distribution, which is widely considered as a foundational contribution in reliability theory; their work provided the first mathematically rigorous and well-developed discrete analog of a major continuous distribution (W distribution), exceeds the geometric distribution, which is the discrete counterpart of the exponential. The main motivation behind their study was to construct a flexible and theoretically sound discrete version of the continuous W distribution, capable of modeling failure data observed in discrete units such as cycles, shocks, or time intervals rather than in continuous time.

Over the years, many researchers have introduced discrete analogs of well-known continuous distributions to deal with lifetime and count data. Examples include discrete versions of Chen, W, Lindley, Burr, Pareto, inverse W, Burr Type-XII and inverted Kumaraswamy distributions. For instance, Ref. [2] presented a discrete analog of Chen distribution, while Ref. [3] introduced a new discrete family of distributions and studied the generalized DW distribution as a particular case of their proposed framework. Further developments include the discrete Gumbel distribution derived by Ref. [4] and the discrete one-parameter Teissier distribution presented by [5]. In addition, Ref. [6] introduced the one-parameter discrete Burr-Hatke exponential distribution and Ref. [7] proposed a discrete version of Generalized Gompertz distribution.

Moreover, Ref. [8] proposed a discrete analog of the continuous logistic exponential distribution, while Ref. [9] introduced a one parameter distribution named the discrete odd Lindley half-logistic distribution. In the same direction, Ref. [10] introduced the discrete odd inverse Pareto exponential distribution for modeling count data; this distribution can be viewed as a generalization of the discrete Marshall–Olkin exponential, discrete exponentiated exponential and discrete exponential distributions. Additionally, Ref. [11] introduced a discrete version of Fréchet–W distribution; they obtained some statistical properties and applied it to five real-life datasets from diverse application area.

In recent years, many researchers have developed several discrete analogs of well-known continuous distributions, as well as new single-parameter discrete distributions. For example, Ref. [12] suggested a discrete analog of the alpha power inverted Kumaraswamy distribution and demonstrated its effectiveness through applications to real datasets, while Ref. [13] obtained a discrete analog of the continuous new generalized Rayleigh distribution. Similar developments include the one-parameter discrete linear-exponential distribution derived by Ref. [14] and the discrete power quasi-Xgamma distribution formulated by Ref. [15]. Furthermore, Ref. [16] constructed two discrete counterparts of the Rayleigh–Lindley distribution using both the general discretization technique and the hazard rate preservation method and examined their properties in detail. Additional advances were made by Ref. [17], who introduced discrete analogs of both the one-parameter half-logistic distribution and its two-parameter generalization obtained through exponentiation of the cumulative density function (cdf) and by Ref. [18], who developed a one-parameter discrete version of the XLindley distribution. Ref. [13] derived another discrete analog of the continuous new generalized Rayleigh distribution, while Ref. [19] proposed the discrete W-exponential distribution through the discretized W-G family of distributions. More recently, Ref. [20] proposed the discrete Topp–Leone generated family of distributions, offering new distributions to modeling lifetime data.

In addition to discretization, another important approach is the use of mixture distributions, which allow researchers to model heterogeneous populations composed of subgroups with different failure mechanisms by combining two or more distributional components. A finite mixture distribution can be defined as a probability distribution obtained from a weighted combination of two or more component distributions, arising either from the same distribution with varying parameters or from completely different distributional forms, with corresponding mixing proportions that determine the relative contribution of each component to the overall mixture. Mixture distributions are highly flexible and particularly useful in reliability studies when the data comes from systems with multiple subgroups, such as weak versus strong components, populations with different failure forms or those exhibiting multimodal lifetime patterns.

Several studies have explored mixture distributions (e.g., Refs. [21,22,23,24,25]). Combining discretization with mixture modeling yields highly flexible distributions capable of capturing the complex structure of count and lifetime data. A discrete mixture model retains the interpretability and tractability of discrete distributions while benefiting from the adaptability and robustness of mixture modeling. This synergy enhances model fit and enables the effective representation of multimodality, tail behavior, and diverse hazard rate shapes.

In this context, Ref. [26] employed the concept of mixing followed by discretization through pdf preservation to develop a two-parameter discrete Lindley distribution, illustrating the value of combining mixture modeling with discretization techniques. The integration of these two approaches is particularly important for modeling discrete lifetime and count data that exhibit both population heterogeneity and complex hazard rate patterns. Though discrete analogs of continuous distributions and finite mixture distributions have been widely studied, most previous works have generally treated these two directions independently, without formulating a discrete mixture distribution derived directly via the general discretization (survival) approach of a continuous finite mixture. The proposed discrete mixture of two W (DMTW) distributions addresses this gap by preserving key reliability properties from its continuous counterpart while enhancing flexibility through mixture components, thereby enabling the modeling of heterogeneity and complex hazard rate behaviors in discrete settings.

Identifiability is a fundamental theoretical property in finite mixture modeling: it guarantees that different parameter settings yield distinct mixture distributions, thereby making model estimation meaningful and unique. This issue was first rigorously addressed by Ref. [27], who showed under transform-based conditions (e.g., via moment-generating or characteristic functions) that finite mixtures of several classical families (such as normal and gamma) are identifiable. Building on this, Ref. [28] derived a necessary and sufficient condition based on linear independence of component densities, which provides a more general and powerful criterion for identifiability.

Ref. [29] extended these ideas by introducing a transform (namely, the moment-generating function of ) and used it to prove identifiability for finite mixtures involving W, log-normal, chi, Pareto, and power-function distributions. These foundational works have been complemented more recently by surveys and generalizations (e.g., Ref. [30]) that systematize sufficient conditions for identifiability across a variety of kernel distributions.

Although continuous W mixtures have been widely studied, discrete analogs capable of flexibly modeling complex count data remain largely unexplored. To fill this gap, we propose a discrete mixture of two W distributions, deriving key statistical properties such as sf and hrf, moments, quantiles, and order statistics. The proposed distribution demonstrates high flexibility in capturing a wide range of shapes and tail behaviors, is applicable to censored data, and is validated through simulations and real-life datasets, highlighting its practical significance as a versatile tool for modeling complex count data.

Despite many advancements, existing discrete distributions often lack dual flexibility. Therefore, in this paper, a new distribution called DMTW distribution is proposed. Our motivations to introduce the DMTW distribution are listed as follows:

- To model various hazard rate behaviors using a discrete framework.

- To represent data from heterogeneous populations via a finite mixture.

- To derive closed-form expressions for reliability and related functions.

- To demonstrate superior goodness of fit over existing discrete models.

Discretizing a Continuous Distribution

The general approach of discretization can be used to construct a discrete distribution by introducing a grouping on the time axis. If the crv has the sf, and times are grouped into unit intervals so that the drv of denoted by ; which is the largest integer less than or equal to , will have the probability mass function (pmf).

The pmf of drv, , can be viewed as discrete concentration of pdf of . Thus, given any continuous distribution it is possible to construct corresponding discrete distribution using (1).

One advantage of applying this approach of discretizing is that the sf for discrete distributions retain the same functional form as the sf of the continuous distributions, consequently, many reliability characteristics and properties remain unchanged. Therefore, discretizing a continuous lifetime distribution via this approach provide a simple and effective way to derive a discrete lifetime distribution that corresponds to the continuous one.

Regarding alternative models such as discrete generalized gamma, Poisson–Lindley mixtures, and hurdle models are valuable for addressing specific data features such as excess zeros and over-dispersion. However, while these models are suitable for such situations, they do not preserve the survival or hazard interpretations of the underlying continuous distributions. In contrast, the DMTW model is specifically designed for cases where the discrete counts represent discretized lifetimes or event counts exhibiting significant hazard behavior.

The other portions of this work are structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the construction of a new DMTW distribution. Section 3 discusses how some statistical properties of the proposed distribution are derived. An estimation of the parameters is investigated in Section 4. Simulation study, applications, conclusion, and suggestions for further research are presented, respectively, in Section 5, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8.

2. Construction of Discrete Mixture of Two Weibull Distributions

Mixtures of W distributions have attracted considerable attention in recent statistical research due to their flexibility and capacity to model complex data. They are particularly useful in reliability analysis, where they effectively represent heterogeneous failure mechanisms and diverse lifetime behaviors. The W distribution is a natural choice in lifetime analysis due to its flexibility in modeling a variety of hazard rate behaviors, as its two parameters control scale and shape, allowing it to represent the principal hazard patterns of interest. Consequently, combining two W components produces a highly flexible distribution. As demonstrated in our paper, even with only two components, the resulting distribution can capture population heterogeneity and generate a wide variety of probability mass function and hazard-rate shapes, including increasing, decreasing, bathtub-like, and multimodal behaviors.

Finite mixture of W distributions consists of two or more component distributions, with at least one of which is a W distribution. These components of distributions are often referred to as sub-populations or mixture components. In the literature, such distributions have been referred to by various names, including additive-mixed W distributions, bimodal-mixed W (for two-component mixtures), mixed-mode W, W of the mixed type, and multimodal W distributions (see Ref. [31]). These names reflect the variety of contexts in which mixture of W distributions are applied, particularly in reliability analysis and lifetime modeling.

The pdf of the standard W distribution with two parameters is given by

where is the scale parameter and is the shape parameter.

The pdf of MTW distribution is given as follows:

where is the mixing parameter, are a shape parameter, and are scale parameters.

The cumulative density function (cdf) and sf function are, respectively, given by

Using (1) can be viewed as the discrete analog to the continuous MTW variable and is commonly said to have DMTW distribution with five parameters denoted by DMTW where the pmf of can be written as

The cdf, sf and hazard rate function (hrf) are, respectively, given by

There are some problems associated with the definition of which are mentioned below:

- is not additive for series system.

- The cumulative hrf in the discrete case,

- has the interpretation of a probability.

Therefore, it was necessary to find an alternative definition that is consistent with its continuous counterpart. Ref. [32] provided an excellent alternative definition of a discrete hrf denoted by

The relation between , is given by

The two concepts of and have the same monotonic property, i.e., is increasing (decreasing) if and only if is increasing (decreasing).

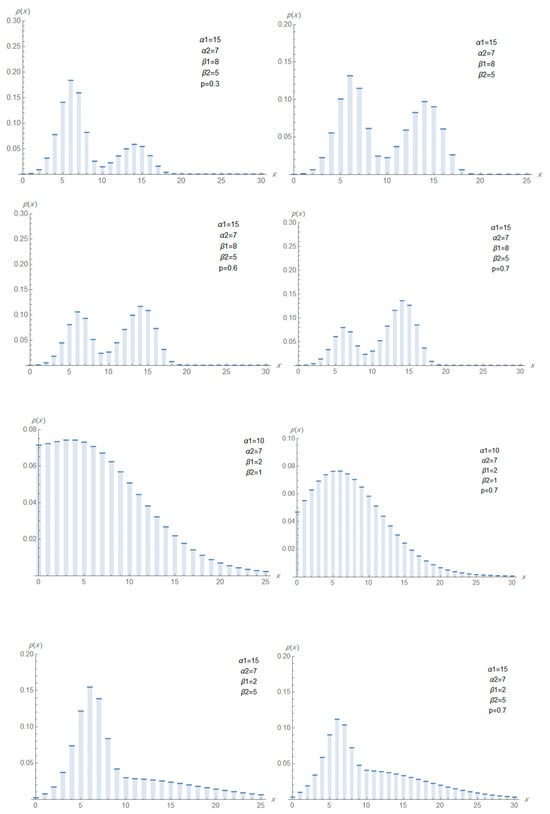

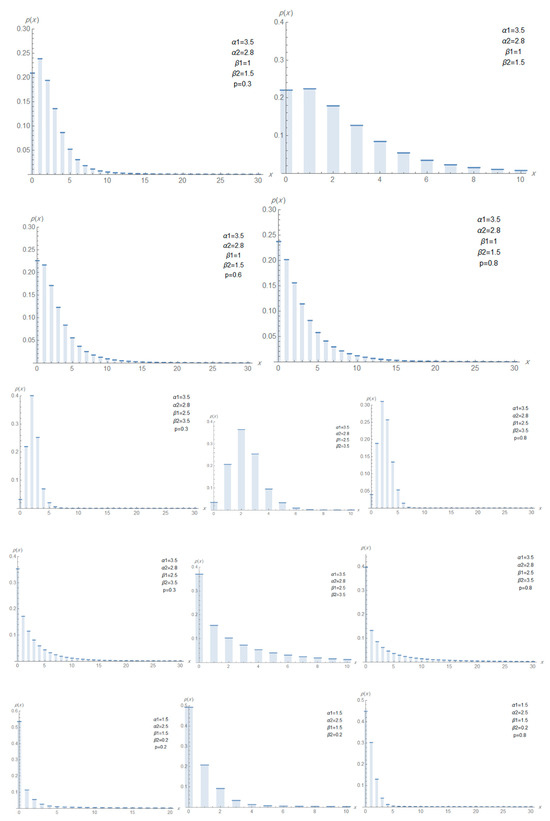

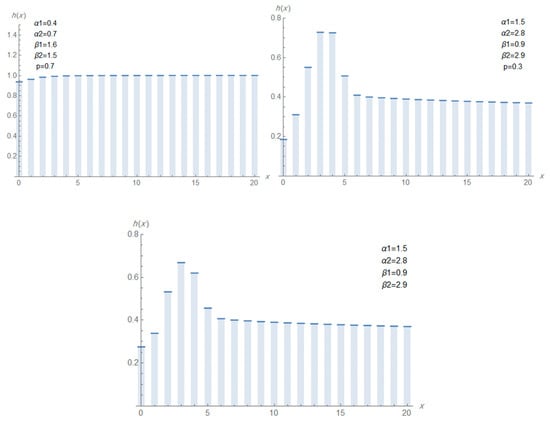

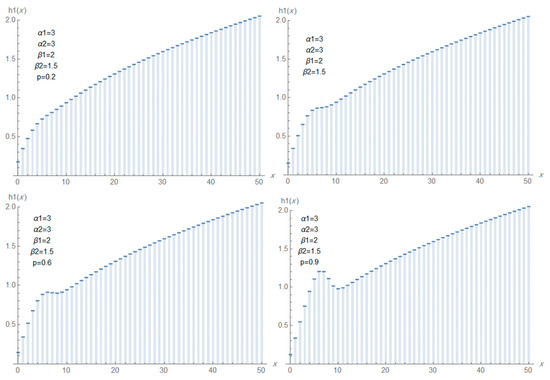

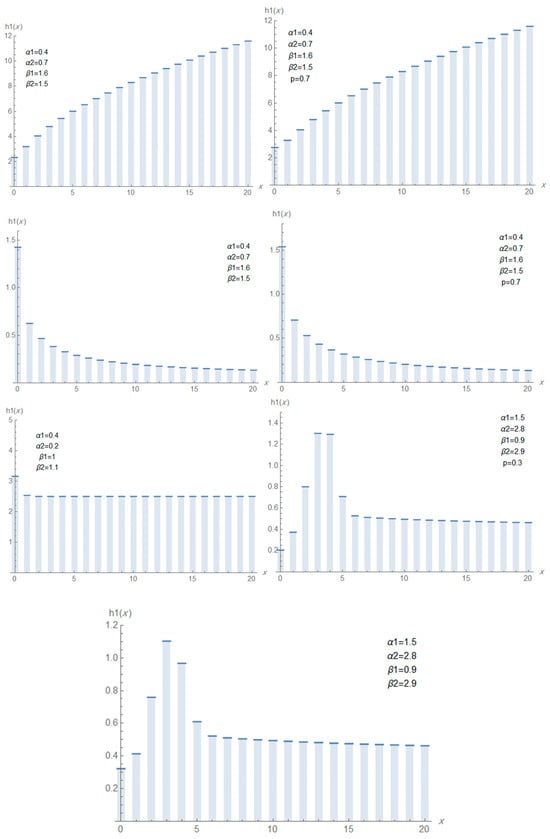

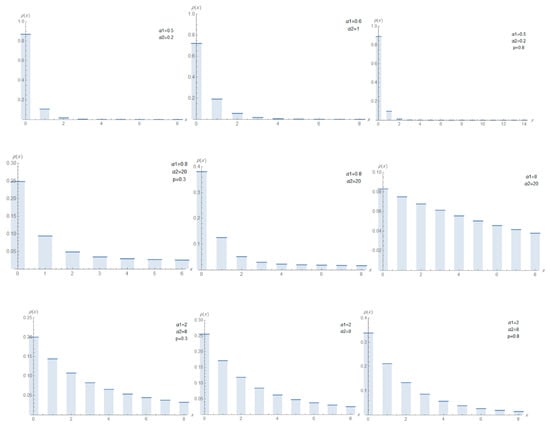

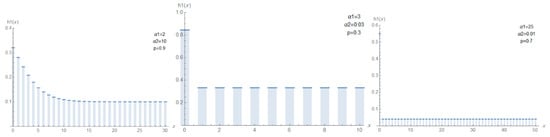

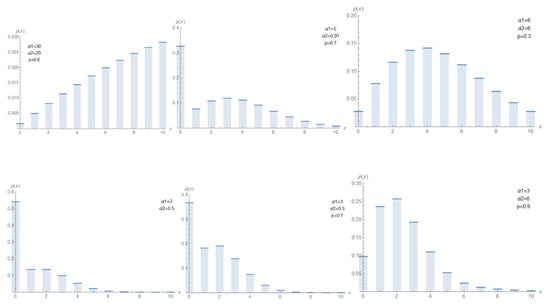

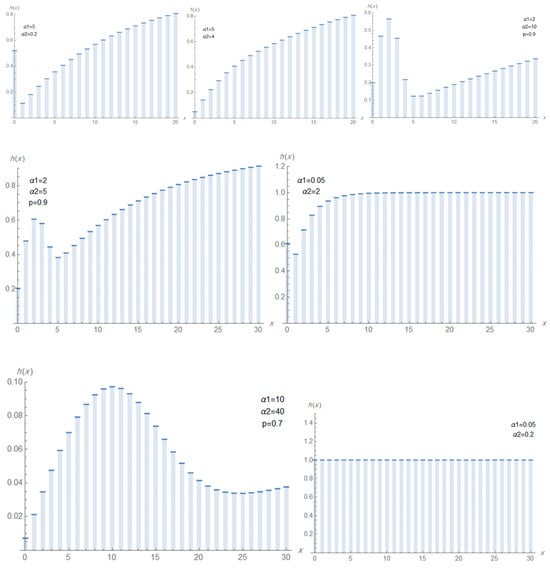

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 display the pmf, hrf, and ahrf of the DMTW distribution under different values of the parameters. In certain plots, the parameter is explicitly shown, whereas in others it is kept constant at (though not indicated on the figures).

Figure 1.

Plots of pmf of DMTW for different values of

Figure 2.

Plots of hrf of DMTW for different values of

Figure 3.

Plots of ahrf of DMTW for different values of

One can observe from Figure 1 that the pmf of DMTW distribution can be decreasing, unimodal, bimodal or right skewed and may take other forms depending on the selected values of the parameters.

The influence of the mixing proportion becomes evident only when the two component W distributions differ meaningfully in their scale and shape parameters. In such cases, varying shifts the total distribution between the two distinct components, sometimes producing bimodality. However, when the two components have very similar parameter values, the effect of changing is less noticeable, since the mixture essentially combines distributions with nearly identical shapes.

The DMTW distribution exhibits considerable flexibility in modeling hazard rate shapes, depending on the parameter values showed in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Specifically, it can be represented increasing, decreasing, approximately constant and upside-down bathtub (inverted bathtub); such a pattern indicates that the failure rate increases during early life, potentially due to initial wear or instability, then decreases and stabilizes, which may reflect enhanced reliability or self-selection of stronger units over time. This behavior is highly relevant in industrial and biological contexts, where early-life failure (infant mortality) is followed by a period of higher reliability.

As result, the DMTW distribution demonstrates flexibility in modeling various reliability patterns. Unlike classical lifetime distributions that are often limited to monotonic hazard functions, the DMTW distribution through its mixture and discretization structure can capture complex behaviors such as this one. This flexibility makes it a suitable candidate for modeling real-world lifetime data exhibiting different reliability shapes.

2.1. Special Sub-Model

In this subsection, two sub-models can be studied from DMTW distribution given in (6); discrete mixture of two Exponential (DMTEx) and discrete mixture of two Rayleigh (DMTR) distributions.

2.1.1. The Discrete Mixture of Two Exponential Distribution

The DMTEx distribution is a special case of DMTW, when in (6)–(10) with pmf, cdf, sf and ahrf are as follows:

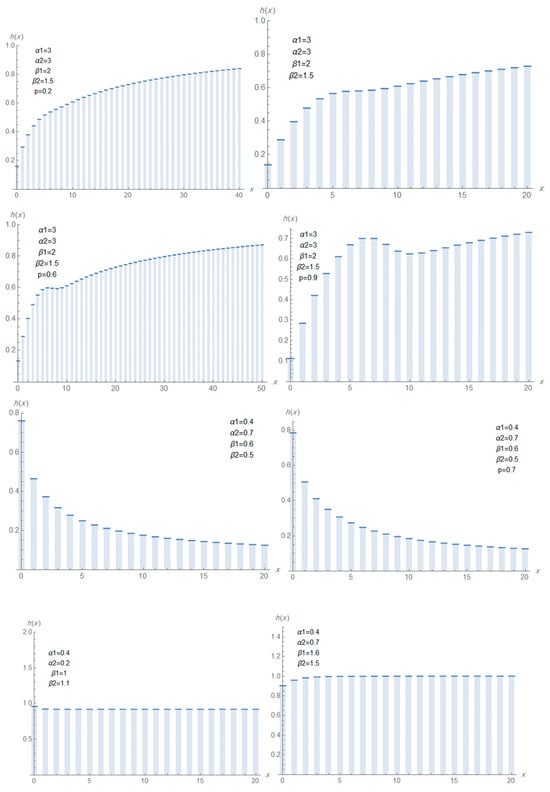

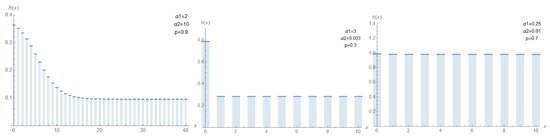

The plots of the pmf, hrf, and ahrf of the DMTEx for different values of the parameters are presented in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. Figure 4 shows some pmf plots for various parameter combinations, illustrating that the pmf may exhibit a decreasing pattern. This behavior confirms the capability of the DMTEx pmf to model data characterized by monotonically decreasing frequencies, a feature commonly observed in discrete lifetime and count-based applications. Figure 5 and Figure 6 display the hrf and ahrf for different values of the parameters, exhibiting both decreasing and constant shape. This flexibility results from the interaction between the two exponential components within the mixture structure. Such adaptability is crucial for modeling systems in which the failure rate either decreases over time or remains stable across specific intervals. These hazard-rate patterns further demonstrate the practical value of the DMTEx distribution in reliability and survival analyses, where accurately representing diverse failure-rate behaviors is essential.

Figure 4.

Plots of pmf of DMTEx for different values of α1, α2, and p=0.5.

Figure 5.

Plots of hrf of DMTEx for different values of α1, α2 and p.

Figure 6.

Plots of hrf of DMTEx for different values of and p.

2.1.2. The Discrete Mixture Two Rayleigh Distribution

The DMTR distribution is a special case of DMTW, when in (6)–(10) with pmf, cdf, sf, hrf, and ahrf are as follows:

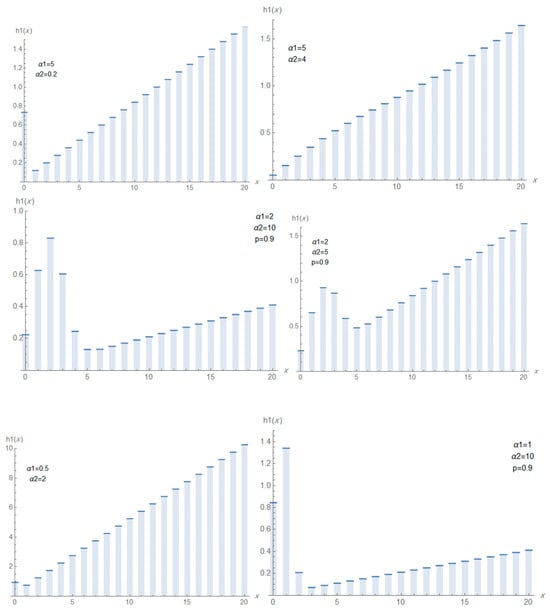

and

The plots of the pmf, hrf, and ahrf of the DMTR distribution for different parameter values are presented in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. Figure 7 displays the pmf for various parameter values, which can exhibit increasing, decreasing, unimodal and right skewed shapes. This reflects the distribution’s flexibility and its ability to model diverse forms of discrete data, including both light- and heavy-tailed behaviors. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the hrf and ahrf can be decreasing, increasing and constant depending on the parameter values. These illustrate that the hrf and ahrf can exhibit a strictly increasing pattern, indicating that the hazard rate increases over time. Other plots display a decreasing shape, corresponding to situations where the hazard rate decrease over time. Additionally, some curves exhibit non-monotonic behavior, where the hrf or ahrf initially increases and then decreases (or vice versa), demonstrating unimodal or bathtub-shaped patterns. This variety of shapes confirms that the DMTR distribution can effectively model datasets with diverse hazard structures, including increasing, decreasing, and more complex hazard patterns.

Figure 7.

Plots of the pmf of DMTR for different values of and p.

Figure 8.

Plots of the hrf of DMTR for different values of and p.

Figure 9.

Plots of the ahrf of DMTR for different values of and p.

3. Properties of Discrete Mixture of Two Weibull Distributions

This section discusses the main statistical properties of DMTW distribution. Several fundamental characteristics are examined, such as the quantile function, order statistics, Rényi entropy, and moments, as well as other related measures. These properties illuminate the distribution’s behavior and enhance its applicability for modeling lifetime data, reliability analysis and various applied statistical contexts.

3.1. Quantile Function

The th quantile function of distribution, say , is the solution of

where denotes the smallest integer greater than or equal to ,

3.2. The Moments of Discrete Mixture of Two Weibull Distribution

The th moments of the drv DMTW distribution may be obtained as follows:

Also, one can use the first fourth rth moments to obtain mean, variance, skewness () and kurtosis () as follows:

and

The moments of DMTW distribution provide important visions around its central tendency, dispersion, and overall shape. These moments are obtained as weighted averages of the moments of two components of DW distributions, based on a specified mixing proportion. Specifically, the th moments of the DMTW distribution are expressed as a linear combination of the th moments of each component, with weights corresponding to their mixing probabilities. Because of the complex structure of the DMTW pmf, the moments usually cannot be expressed in closed forms and must be evaluated numerically. The first moment represents the mean of the distribution, while the second moment, together with the mean, is used to obtain the variance. Higher-order moments, such as sk and ku, can also be evaluated as they play an important role in describing the asymmetry and tail behavior of the distribution.

3.3. Index of Dispersion

The index dispersion (ID) is defined as the ratio of the variance to the mean, It serves as a diagnostic tool to assess whether the distribution is over-dispersed , under-dispersed () or equi-dispersed , which is particularly important in count data modeling and reliability analysis. Due to the DMTW distribution which may involve different shape and scale parameters across its components, the ID can vary significantly depending on the mixing parameter and the component parameters’. Consequently, numerical evaluation of both the mean and variance is typically required to compute this index.

Table 1 shows the main descriptive measures of the DMTW distribution, including the mean, median, variance, sk, ku, and the ID for selected parameter values. These summaries help to illustrate how the distribution behaves under different choices of its parameters.

Table 1.

Mean, Median, Variance, Sk, Ku and ID of DMTW distribution for some values of the parameters and .

The following significant observations can be interpreted as follows:

For fixed parameters and varying from 2 to 4:

The mean increases slightly from 0.8203 to 0.8409.

The variance decreases significantly from 0.7897 to 0.5146.

The ID ranges from 0.9626 to 0.6119.

As increases and fixed the parameters and , the distribution turns into under-dispersed, showing less variability around the mean. Similarly, sk decreases from 1.0993 to 0.2967, while ku drops from 4.1535 to around 2.1477. In practical, the distribution moves from being positively skewed with heavy tails to more symmetric and light-tailed form. These reflect the high flexibility of the DMTW distribution in capturing a wide range of shapes as its parameter values differ.

For ( and shows over-dispersion, meaning the distribution can model highly variable data more effectively than the Poisson distribution.

Also, for certain parameter combinations such as ( with different values of and the ranges from 0.4583 to 1.1580. This shows the notable flexibility of the DMTW distribution, which can capture both under-dispersed and over-dispersed behavior depending on the parameter values.

In general, Table 1 illustrates the strong flexibility of the DMTW distribution in modeling a wide range of statistical behaviors. It can effectively represent symmetric or skewed distribution. It is also able to accommodate both light- and heavy-tailed data, as well as over-dispersed and under-dispersed count data. This flexibility makes it a valuable distribution in several areas such as reliability analysis, medical statistics, insurance modeling and environmental studies, where classical distributions may fail to adequately capture the underlying data structure.

3.4. Rényi Entropy

Entropy is a fundamental concept that quantifies the uncertainty associated with rv X. It has a wide range of applications in various fields; including econometrics, survival analysis, and computer science, [for more details, see Ref. [33]]. The Rényi entropy measure of order for drv with pmf is defined as

where is the vector of W parameters.

In the context of the DMTW distribution, the Rényi entropy can be expressed as follows:

Shannon Entropy

Shannon entropy is a special case of the Rényi entropy when , can be defined as follows:

3.5. Mean Time to Failure, Mean Time Between Failure, and Availability

Mean Time to Failure (MTTF), Mean Time between Failure (MTBF), and Availability (Av) are key reliability metrics used to evaluate and predict the lifecycle performance of a product or system. Both manufacturers and end users depend on these metrics, because they provide estimates of expected failure rates and operational durations. MTTF, MTBF, and Av allow for informed decision-making based on historical data or reliability testing.

In addition, incorporating MTTF, MTBF, and Av during the design stage is essential for developing systems that are both reliable and maintainable. Accurately predicting these measures early in the process ensures that the system will meet performance requirements throughout its intended operational lifetime.

The MTTF represents the expected time until the first failure of a non-repairable system. It can be calculated as (in discrete units)

The MTBF is applicable for repairable systems and reflects the average operational time between two successive failures. It can be given using the formula:

The Av is considered as the probability that the component is successful at given time. It is computed as the ratio between MTTF and MTBF:

3.6. Order Statistics of DMTW Distribution

Let be a random sample from the DMTW distribution with cdf where is the vector of the W parameters , and Let denote the order statistics, he cdf of the th order statistics, denoted is given by

Using the binomial expansion for

For the DMTW distribution, the cdf is as follows:

If in (37), one can obtain the cdf of the first order statistics; as given below:

If in (37), one can obtain the cdf of the largest order statistics; as given below:

The pmf of is defined by

Using the binomial expansion for , then the pmf in (40) is

The pmf of the smallest order statistics is obtained by substituting in (41) as follows:

The pmf of the largest order statistics is obtained by substituting in (41) as follows:

For further details, refer to Ref. [34].

4. Estimation of the Parameters of Discrete Mixture Two Weibull Distribution

In this section, the method of maximum likelihood (ML) is employed to estimate the unknown parameters, sf, hrf and ahrf of the DMTW distribution. The ML method is one of the most powerful and widely used techniques in statistical inference due to its desirable properties. In particular, ML estimators are consistent, asymptotically unbiased and efficient, meaning that as the sample size increases, the estimates converge to the true parameter values with minimal variance. These advantages make the ML method a preferred choice for parameter estimation in many applied and theoretical studies.

Suppose that is a Type II censored sample of size r obtained from a life-test on n items whose lifetimes have DMTW distribution. Then the likelihood function is

where and , are given, respectively, by (6) and (8). The are ordered times for

The natural logarithm of the likelihood function is given by

By differentiating the log-likelihood function with respect to the parameters as follows:

,

The ML estimators can be obtained by equating (48)–(52) with respect to zero. The resulting system of non-linear equations can then be solved numerically, using the Newton–Raphson method, to derive the estimators

Depending on the invariance property, the ML estimators of sf, hrf, and ahrf can be obtained by replacing with their corresponding ML estimators in (8), (9) and (10), respectively, as given below:

and

The asymptotic distribution of the ML estimators can be used to construct the asymptotic confidence intervals (CIs) for the parameters . Under regularity conditions, the ML estimators have approximately multivariate normal with mean and variance covariance matrix , where is the observed Fishers information matrix and is defined as

The diagonal elements of represent asymptotic variances for respectively.

Consequently, the two-sided approximate CI for and are as follows:

where and are the lower and upper bounds, respectively, is the standard deviation, is the percentile of the standard normal distribution with right-tail probability and is, respectively,

5. Simulation Study

In this section, a simulation study is performed to illustrate the accuracy and efficiency of the ML estimates for the parameters of the DMTW distribution for different samples of sizes (30, 50, 100, 150, 200) and population parameter combinations using number of replication (NR) = 1000. The computations are conducted using Mathematica 11.

The steps of the simulation procedure are as follows:

- Using three different combinations of population parameter values:

- ➢

- ➢

- ➢

- Generate 1000 random samples of size n = 30, 50, 100, 150 and 200 from DMTW distribution based on levels of percentage of uncensored observations Type II censoring.

- Computing the averages, estimated risks (ERs), relative errors (Res), variance for ML estimates of the parameters, sf, hrf and ahrf for each model parameters and for each sample size as follows:

- Average (estimate) =

- ER (estimate) =

- RE (estimate) =

- Variance (estimate) =

- Repeat the previous steps 1000 times for each sample size and for each selected set of the parameters.

The results are summarized in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 for different parameter combinations based on Type–II censoring scheme with level of percentage of uncensored observations.

Table 2.

Averages, ERs, REs, Variance of the ML estimates, and 95% confidence intervals of the parameters based on Type II censoring of DMTW. .

Table 3.

Average, ERs, REs, Variance of the ML estimates, and 95% confidence intervals of the parameters based on Type II censoring of DMTW. .

Table 4.

Average, ERs, REs, Variance of the ML estimates, and 95% confidence intervals of the parameters based on Type II censoring of DMTW. .

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 highlight key observations on the performance of the ML estimators across varying sample sizes. Notably, as the sample size grows, the average ML estimates gradually approach the true parameter values, demonstrating the consistency and reliability of the proposed estimators. Furthermore, the results demonstrate a significant improvement in estimation accuracy. In particular, Res, ERs, and variances of the ML parameter estimates, along with the reliability measures (sf, hrf, and ahrf), systematically decrease as the sample size increases. This reduction highlights the enhanced precision and stability of the estimates, confirming that larger samples yield more reliable and consistent estimates of the model parameters and their associated reliability functions. Also, the CIs exhibit a consistent pattern, with the lengths of the 95% CIs for all parameters and reliability measures decreasing as the sample size increases. This narrowing reflects improved estimation accuracy and further emphasizes the efficiency of the ML method in estimating the parameters.

6. Applications

In this section, the flexibility and applicability of the proposed distribution are demonstrated by analyzing two real datasets. For each data, the DMTW distribution is compared with some distributions, such as DW proposed by Ref. [1], discrete generalized inverse W (DGIW) studied by Ref. [35], discrete alpha power W (DAPW) introduced by Ref. [36], exponentiated DW (EDW) presented by Ref. [37] and discrete modified W (DMW) proposed by Ref. [38]. The comparison is based on a set of criteria, namely Kolmogorov –Smirnove (K-S) statistic and its p-value, the −2log-liklihood (−2lnL), Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion with correction (AICc):

and

where k denotes the number of estimated parameters, is the log-likelihood function evaluated at the ML estimates, and is the sample size. The distribution that yields the smallest values of these statistics is regarded as the best for fitting the data.

6.1. Dataset I

The first dataset comprises the remission times (in weeks) for the 21 patients who received placebo in a clinical trial of 97 patients with acute leukemia investigating the effect of 6-mercaptopurine, originally reported by Ref. [39]. The data were as follows: 1,1,2,2,3,4,4,5,5,8,8,8,8,11,11,12,12,15,17,22 and 23 weeks.

Table 5 presents the ML estimates along with their corresponding standard errors (SEs), together with the values of −2lnL, AIC, BIC, AICc, and the K–S statistic with its associated p-value. The results indicate that all considered distributions provide an acceptable fit to the data based on the K–S statistics and their p-values. However, the DMTW distribution clearly outperforms the others, as it yields the smallest K–S statistic (0.190) and the largest p-value (0.820). In addition, the DMTW model attains the lowest values of −2lnL (170.323), AIC (180.323), BIC (185.546), and AICc (184.323), collectively supporting its superior fit under the specified criteria. In contrast, the remaining distributions, including DW, DGIW, DAPW, EDW, and DMW, exhibit comparatively larger values of −2lnL, AIC, BIC, and AICc, along with smaller K–S statistics and p-values. Consequently, the DMTW distribution is identified as the best model among the alternatives based on the provided goodness-of-fit measures.

Table 5.

Goodness-of-fit measures for fitted models for real dataset I.

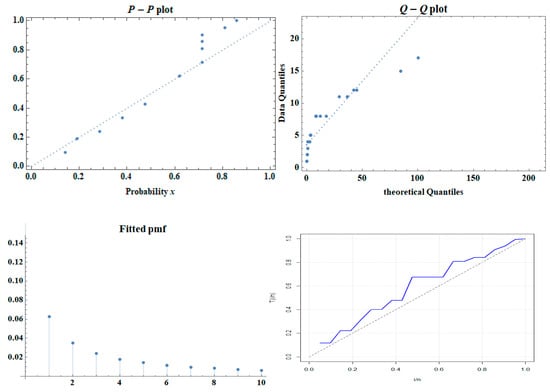

The total time test (TTT) plot is used to assess the shape of the hrf, which aids in selecting appropriate models for the dataset. Figure 10 displays the full set of diagnostic plots for the fitted DMTW distribution, including the P–P plot, Q–Q plot, TTT plot, and the fitted pmf. Together, these graphical tools provide strong evidence that the proposed distribution adequately fits the data. The TTT plot is particularly useful for assessing the general shape of the hrf. The pattern exhibited in the TTT plot suggests the underlying hazard structure of the dataset I and assists in determining whether the DMTW distribution is an appropriate choice. The observed curve of the TTT plot aligns with the expected behavior of the DMTW hazard rate (increasing), supporting the suitability of the distribution for representing the data. Also, both the P–P and Q–Q plots show points lying close to the fitted line, indicating strong agreement between the empirical distribution and the fitted DMTW model. Furthermore, the fitted pmf closely matches the empirical frequencies across the support of Dataset I, confirming that the DMTW model accurately represents the distributional shape. These diagnostic plots collectively demonstrate that the DMTW distribution provides an excellent fit for Dataset I, effectively representing both the distributional form and the underlying hazard-rate behavior.

Figure 10.

P-P, Q-Q, TTT plots and fitted pmf of the DMTW distribution for dataset I.

6.2. Dataset II

The second dataset consists of the number of shocks before failure, as reported in [31]. The data are as follows: 1,3,3,4,4,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,10,11,12,14.

Table 6 presents the same calculations as those in Table 5 but applied to Dataset II. The results indicate that all compared distributions provide an adequate fit; however, the DMTW distribution exhibits the smallest K–S statistic (0.25) and the largest p-value (0.684), indicating the best agreement between the empirical and fitted distributions. Furthermore, the DMTW distribution achieves the lowest values of −2lnL, AIC, BIC, and AICc. Based on these criteria, the DMTW distribution emerges as the best model for Dataset II.

Table 6.

Goodness-of-fit measures for fitted models for real Dataset II.

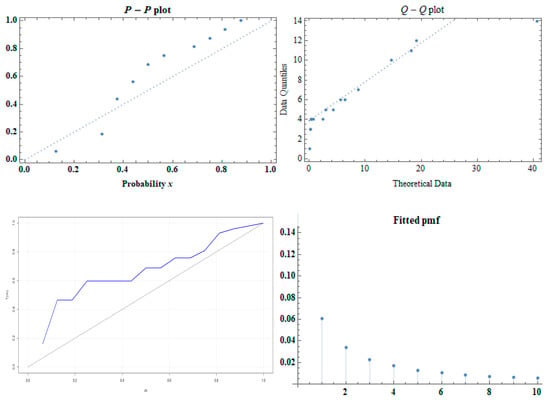

The diagnostic plots in Figure 11 provide further evidence of the suitability of the DMTW model for Dataset II. The shape of the TTT curve indicates an increasing hrf, confirming that the DMTW distribution aligns with the observed hazard behavior. Both the P–P and Q–Q plots show points close to the fitted line, reflecting strong agreement between the observed data and the model. The fitted pmf also matches the empirical frequencies closely, providing additional support for the model’s performance. Overall, these results demonstrate that the DMTW distribution offers the best fit for Dataset II compared with other distributions.

Figure 11.

P-P, Q-Q plots, TTT and fitted pmf of the DMTW distribution for Dataset II.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, a discrete mixture of two Weibull distributions (DMTW) was introduced, offering flexible shapes for the pmf, hrf, and ahrf, making it suitable for modeling diverse behaviors in discrete lifetime and count data. Several important statistical properties of the DMTW distribution were investigated, including the index of dispersion, order statistics, moments, and Rényi entropy. The unknown parameters, sf, hrf, and ahrf, were estimated using the ML method. The performance and applicability of the proposed DMTW distribution were illustrated using two real datasets, and its fit was compared with several well-known discrete distributions, including DW, DGIW, DAPW, EDW, and DMW. The results from both goodness-of-fit measures and diagnostic plots confirmed that the DMTW distribution consistently outperforms the competing distributions, demonstrating the smallest K-S statistics, lowest −2lnL, AIC, BIC, and AICc values, and the best overall agreement with observed data. Overall, the findings indicate that the DMTW distribution is a highly flexible tool for modeling discrete lifetime and count data, capable of capturing heterogeneity and complex hazard rate patterns, and provides a robust framework for practical applications in reliability and lifetime analysis.

8. Suggestions for Further Research

Future research may focus on developing predictive inference for the proposed DMTW distribution, including both Bayesian and non-Bayesian approaches. Particular attention can be devoted to one-sample and two-sample prediction problems. Also, alternative estimation techniques beyond the traditional ML approach could be investigated, such as the modified ML and maximum product spacing methods. The E-Bayesian and empirical Bayesian procedures also represent another direction for estimating the model parameters, sf, hrf and ahrf.

Moreover, the DMTW framework can be further extended by considering mixture distributions with more than two components or by constructing new classes of mixture distributions. Furthermore, the robustness of both ML and Bayesian estimation methods can be investigated under various censoring schemes, including Type I, progressive Type II, and hybrid censoring.

Future research should focus on translating the methodological advances of the DMTW distribution into practical applications for relevant authorities and healthcare agencies, such as the Ministry of Health. The enhanced flexibility of the DMTW distribution allows more accurate modeling of real-world medical data, particularly in cases of heterogeneity or complex hazard structures. It can be applied to reliability assessment of medical devices, analysis of patient survival times, modeling the number of clinical events, and evaluating treatment response patterns. Incorporating alternative estimation techniques and extending the framework to mixtures with more components could further improve the reliability and applicability of these models, providing policymakers and healthcare institutions with actionable insights for evidence-based decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.M., G.R.A.-D. and A.A.E.-H.; Methodology, M.A.H., Z.I.K., G.R.A.-D. and M.K.A.E.; Software, A.A.E.-H. and M.K.A.E.; Validation, Z.I.K. and G.R.A.-D.; Formal analysis, D.R.S., M.A.H. and M.K.A.E.; Investigation, M.A.H., Z.I.K. and G.R.A.-D.; Resources, H.H.M.; Data curation, D.R.S., M.A.H., H.H.M., A.A.E.-H. and M.K.A.E.; Writing—original draft, D.R.S., M.A.H. and M.K.A.E.; Writing—review & editing, D.R.S., M.A.H., H.H.M. and Z.I.K.; Visualization, H.H.M., Z.I.K. and G.R.A.-D.; Supervision, G.R.A.-D. and A.A.E.-H.; Project administration, A.A.E.-H.; Funding acquisition, H.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R745), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R745), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nakagawa, T.; Osaki, S. The discrete Weibull distribution. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1975, 24, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, A.M. A two-parameter discrete distribution with a bathtub hazard shape. Commun. Stat. Appl. Methods 2017, 24, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jayakumar, K.; Sankaran, K.K. A generalization of discrete Weibull distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2018, 47, 6064–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chakravarty, D.; Mazucheli, J.; Bertoli, W. A discrete analog of Gumbel distribution: Properties, parameter estimation and applications. J. Appl. Stat. 2021, 48, 712–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Agiwal, V.; Nayal, A.S.; Tyagi, A. A discrete analogue of Teissier distribution: Properties and classical estimation with application to count data. Reliab. Theory Appl. 2022, 17, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, R.P.; Tyagi, A. An inferential study of discrete Burr-Hatke exponential distribution under complete and censored data. Reliab. Theory Appl. 2022, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Das, B.; Hazarik, P.J. Discretized version of Generalized Gompertz Distribution with Application to Real life data. Int. J. Agric. Stat. Sci. 2023, 19, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bossly, A.; Eliwa, M.S.; Ahsan-ul-Haq, M.; El-morshedy, M. Discrete logistic exponential distribution with application. Stat. Optim. Inf. Comput. 2023, 11, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamlan, D.; Baaqeel, H.; Fayomi, A. A discrete odd Lindley half-logistic distribution with applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2701, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengthong, P.; Seenoi, P. Discrete odd inverse Pareto exponential distribution: Properties, estimation and applications. Prog. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Das, B. Discretized Fréchet–Weibull Distribution: Properties and Application. J. Indian Soc. Prop. Stat. 2023, 24, 243–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Dayian, G.R.; EL-Helbawy, A.A.; Hegazy, M.A. A discrete analog of the alpha power inverted Kumaraswamy distribution with applications to real-life data sets. Egypt. J. Bus. Stud. Fac. Commer. Mansoura Univ. 2024, 48, 1018–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Haj Ahmad, H.; Ramadan, D.A.; Almetwally, E.M. Evaluating the discrete generalized Rayleigh distribution: Statistical inferences and applications to real data analysis. Mathematics 2024, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, K.; Fayomi, A.; Baaqeel, H.; Alsuraihi, A. A novel discrete linear-exponential distribution for modeling physical and medical data. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan-ul-Haq, M.; Hussain, M.N.; Babar, A.; Al-Essa, L.A.; Eliwa, M.S. Analysis, estimation, and practical implementations of the discrete power quasi-Xgamma distribution. J. Math. 2024, 2024, 1913285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Ahmad, H. The efficiency of hazard rate preservation method for generating discrete Rayleigh–Lindley distribution. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, A.; Hitaj, A. Discrete half-logistic distributions with applications in reliability and risk analysis. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 340, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, R.; Jodrá, P.; Aswathy, S.; Irshad, M.R. The discrete new XLindley distribution and the associated autoregressive process. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2024, 20, 1767–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balubaid, A.; Klakattawi, H.; Alsulami, D. On the discretization of the Weibull-G family of distributions: Properties, parameter estimates, and applications of a new discrete distribution. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opone, F.C.; Ekhosuehi, N.; Nzei, L.C. The discretization of the Topp-Leone generated family of distributions. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2025, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.E.; Moustafa, H.M.; Abd-Elrahman, A.M. Approximate Bayes estimation for mixture of two Weibull distributions under Type-2 censoring. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 1997, 58, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, A.I.; Bakoban, R.A. On infinite mixture of two component exponentiated gamma distribution. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2009, 5, 1351–1369. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Lee, S.X.; Rathnayake, S.I. Finite Mixture Models. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2019, 6, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.H.; Sim, S.Z.; Liu, S.; Srivastava, H.M. A Family of Finite Mixture Distributions for Modelling Dispersion in Count Data. Stats 2023, 6, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahona, J.A.; Gomez, Y.M.; Gomez-Deniz, E.; Venegas, O.; Gomez, H.W. Scale mixture of exponential distribution with an application. Mathematics 2024, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Aslam, M.; Ahmad, M. A two parameter discrete Lindley distribution. Rev. Colomb. De Estadística 2016, 39, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, H. Identifiability of finite mixtures. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakowitz, S.J.; Spragins, J.D. On the identifiability of finite mixtures. Ann. Math. Stat. 1968, 39, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.E. Identifiability of finite mixtures using a new transform. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 1988, 40, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawaty, B. A Survey on the Identifiability of Finite Mixtures. Neliti. 2024. Available online: https://www.neliti.com/id/publications/245925/a-survey-on-the-identifiability-of-finite-mixtures (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Murthy, D.N.P.; Xie, M.; Jiang, R. Weibull Models; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D.; Gupta, R.P. Classification of discrete lives. Microelectron. Reliab. 1992, 34, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. Math. Stat. Probab. 1961, 1, 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, B.; Balakrishnan, N.; Nagaraja, H.N. A First Course in Order Statistics; John-Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Para, P.A.; Jan, T.R. On three parameter discrete Generalized inverse Weibull distribution: Properties and applications. Ann. Data Sci. 2019, 6, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.O.; Hassan, N.A.; Abdelrahman, N. Discrete Alpha-Power Weibull Distribution: Properties and Application. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2022, 13, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoukhou, V.; Bidram, H. The exponentiated discrete Weibull distribution. Stat. Oper. Res. 2015, 39, 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nooghabi, M.S.; Rezaei Roknabadi, A.H.; Mohtashami Borzadaran, G.R. Discrete modified Weibull distribution. Int. J. Stat. 2011, 2, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Freireich, E.J.; Gehan, E.; Frei, E., III; Schroeder, L.R.; Wolman, I.J.; Anbari, R.; Burgert, E.O.; Mills, S.D.; Pinkel, D.; Selawry, O.S. The effect of 6- mercaptopurine on the duration of steroid induced remissions in acute leukemia: A model for evaluation of other potentially useful therapy. Blood 1963, 21, 699–716. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).