Abstract

Against the backdrop of artificial intelligence (AI) empowering the medical industry, achieving symmetric coordination between patients and medical intelligent systems has emerged as a key factor in enhancing the efficacy of medical human–computer collaborative diagnosis. This study systematically identified the factors influencing the effectiveness of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare by combining literature analysis with expert interviews, based on the Socio-technical Systems Theory. It constructed a symmetric evaluation framework consisting of 19 indicators across four dimensions: user, technology, task, and environment. An integrated DEMATEL method incorporating symmetric logic was employed to quantitatively analyze the interdependent relationships among factors and identify 18 key factors. Subsequently, ISM was applied to analyze the dependency relationships between these key factors, thereby constructing a clear multi-level hierarchical structure model. Through hierarchical construction of a multi-level hierarchical structure model, four core paths driving diagnostic effectiveness were revealed. The research shows that optimizing user behavior mechanisms and technology adaptability and strengthening dynamic coordination strategies between tasks and the environment can effectively achieve the two-way symmetric mapping of the medical human–machine system from fuzzy decision-making to precise output. This has not only improved the efficacy of medical human–computer collaborative diagnosis, but also provided a theoretical basis and practical guidance for optimizing the practical application of medical human–computer collaborative diagnosis.

1. Introduction

The deep integration of artificial intelligence (AI) has provided a new paradigm for the medical human–AI collaboration model to advance the construction of a sustainable healthcare service system. Currently, the industry of AI-driven medical intelligent systems is at the intersection of the explosive growth phase and the technology maturity phase. Practical applications of human–AI collaboration are facing multiple challenges [1]. Although the accuracy and reliability of medical AI systems in disease diagnosis and healthcare services continue to improve, they have made significant contributions to the sustainable development of healthcare services. However, it is noteworthy that differences in the expression of consultation questions can lead to fluctuations in the output accuracy of intelligent systems, with a variation range of up to 36% [2]. This data reflects the vulnerability of intelligent systems in actual collaborative scenarios. Patients are core participants in medical human–machine collaboration. During their interaction with intelligent systems, their collaborative diagnostic effectiveness is disturbed by multiple internal and external factors. Such disturbances not only affect the reliability of diagnostic results, but also increase the risks of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis, and reduce patient experience. Ultimately, it restricts the full exploitation of the potential of the medical human–machine collaboration model [3].

In the scenario of medical intelligent diagnosis, achieving sustainable healthcare services is a complex and multidimensional goal. The core of this goal lies in optimizing resource utilization, improving service quality, and promoting the coordinated development of society, technology and economy [4,5]. However, how to balance the accessibility of healthcare services and the optimization of diagnostic quality in medical systems remains a key challenge at present. As a key pathway to improving service efficiency, the performance of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis is profoundly influenced by patient-related factors. Existing studies have initially revealed that patients’ psychological and cognitive differences are key factors affecting the effectiveness of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis. For instance, the quality of patients’ information input behavior, cognitive load, and level of trust in intelligent systems all significantly impact the accuracy and reliability of diagnostic outcomes. These factors may also induce extreme trust tendencies, ultimately leading to a marked decline in diagnostic efficacy [6,7,8]. However, relevant discussions mostly focus on a single dimension. Currently, there is a lack of systematic analysis on multi-dimensional influencing factors and their interaction mechanisms. Furthermore, the causal pathways and hierarchical structure of key influencing factors remain unclear, thereby limiting the theory’s ability to guide practical applications.

In view of this, focusing on the patient-centric perspective and based on the Socio-technical System Theory (SST), this study aims to establish an evaluation system covering four dimensions: personnel, technology, task, and environment. It also integrates the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) and Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) methods (DEMATEL-ISM). From a multi-dimensional perspective, it reveals the hierarchical structure and action paths of key factors to address the following core questions: Q1 Influence Factor Analysis: What are the key influencing factors affecting the effectiveness of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis? Q2 Structural Relationship and Mechanism of Action: What intrinsic relationships exist among these key factors? Q3 Path and Strategy: Based on theoretical analysis, how to construct an operable strategy system? This system aims to improve the robustness and service effectiveness of human–AI collaborative diagnosis, thereby supporting the construction of a sustainable healthcare service system. This study intends to address the fragmentation of existing research through theoretical analysis of the aforementioned questions. It also provides a holistic theoretical model for understanding human–AI collaborative diagnosis. Meanwhile, at the practical level, it can help medical institutions identify key influencing factors during human–AI collaboration. It also supports the development of phased and priority-based effectiveness improvement plans, contributing to the construction of a sustainable healthcare service system.

Through theoretical analysis of the aforementioned issues, this study aims to address the fragmentation of existing research. It also makes three core contributions as follows:

- (1)

- It systematically identifies the influencing factors and key influencing factors of Medical Human–Computer Collaborative Diagnosis Efficiency through a comprehensive methodology, which supplements the existing knowledge system in terms of research theory.

- (2)

- It provides a causal relationship model for analyzing diagnostic efficiency. By exploring the mechanism of action among the key influencing factors of Medical Human–Computer Collaborative Diagnosis Efficiency, it helps medical institutions accurately identify the root causes of inefficiency in the collaborative process.

- (3)

- The research results can help medical institutions and enterprises clarify the priority order and key paths for efficiency improvement. This enables the formulation of phased and targeted efficiency improvement plans, thereby promoting the practical construction of a sustainable medical service system.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Medical Human–Machine Collaboration

Human–machine collaboration is based on the in-depth interaction between humans and intelligent systems (such as algorithms, artificial intelligence, and robots). It is a process of jointly completing content creation by complementing each other’s unique knowledge and capabilities [9]. Its core lies in integrating human emotions, creativity, and complex decision-making capabilities with machines’ data processing, pattern recognition, and high-precision execution capabilities. This integration enables efficient, reliable, and high-quality task performance [10]. At present, the human–machine collaboration model has proven its value in fields such as industry, finance, and transportation [11]. However, when the human–machine collaboration model is applied to medical diagnosis scenarios, it not only requires in-depth coordination between humans and machines, but also needs to closely align with the core characteristics of the medical field. These characteristics include the balance between diagnostic accuracy and time urgency, the conflict between limited resources and complex needs, and the tension between standardized processes and personalized auxiliary diagnosis and treatment. On this basis, medical human–machine collaboration aims to assist doctors and patients in medical activities such as diagnosis, treatment, auxiliary decision-making, and prevention of various diseases through medical intelligent systems [12]. It strives to achieve core values including low misdiagnosis rate, personalized treatment plans, and dynamic allocation of medical resources [13].

The deep integration of artificial intelligence technologies has promoted the sustainable development of the human–machine collaboration model in the medical field. In the field of intelligent diagnosis, AI medical systems play a crucial role. By integrating multiple types of data such as patients’ electronic medical records and medical images, they assist doctors or patients in symptom analysis and provide diagnostic suggestions, significantly improving diagnostic efficiency [14,15,16,17]. In the field of intelligent treatment, and patients’ multi-modal data, provide diagnosis and treatment suggestions supported by evidence-based medicine, and quickly generate accurate consultation opinions through teleconsultation [18,19]. In the field of intelligent rehabilitation and health management, AI systems formulate personalized rehabilitation plans based on patients’ physiological indicators and pathological reports. These plans include medication guidance, dietary advice, and disease prevention strategies, thereby enabling precise and continuous management from hospital to home [20,21]. The wide application of medical intelligent systems has not only changed the service model of medical institutions [22], but also promoted the transformation of medical concepts from “institution-centered” to “patient-centered” [23]. This has laid a solid technical and practical foundation for the achievement of sustainable healthcare services.

2.2. The Efficacy of Medical Human–Machine Collaborative Diagnosis from the Patient Perspective

With the deepening of the medical human–machine collaboration model, it is widely recognized in the academic community that the role of patients is shifting from passive information providers in traditional diagnostic processes to active collaborators interacting with medical intelligent systems [24]. The repositioning of this role has turned diagnostic effectiveness into a systemic value generated by the dynamic interaction between patients and the system. Specifically, this value is reflected in multiple dimensions, including improved diagnostic efficiency, enhanced patient experience and satisfaction, reduced risk of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis, and increased patient trust [25]. However, existing studies lack a unified theoretical framework to integrate these dimensions and explain the trade-off relationships between them. Furthermore, when verifying these values in real-world medical scenarios, how constraints such as interpretability, safety, and ethical compliance specifically regulate the aforementioned values has not yet been systematically explored.

Existing studies have explored the impact of patient behavior on diagnostic effectiveness from multiple dimensions, including information input, interaction behavior, psychological behavior, and system design. However, these studies lack cross-fertilization and comparison, making it difficult to gain insights into the relative importance of factors across different dimensions and their interaction mechanisms. At the level of information input behavior, the completeness and authenticity of information provided by patients form the basis of diagnostic accuracy. Studies have shown that the detail of patients’ symptom descriptions, the omission of key information, and vague expressions using non-professional terminology all significantly affect the accuracy of preliminary diagnostic results [26,27]. However, such studies mostly adopt retrospective analysis or static questionnaires and fail to fully capture the dynamic processes in real-world scenarios. Furthermore, Gaebel et al. further verified through experimental research on clinical decision-aids that when patients provide comprehensive and accurate information, the system can generate more precise treatment recommendations [28]. At the level of interactive behavior, the timeliness of feedback and depth of interaction of medical intelligent systems are crucial. Meskó et al. also adopted an experimental approach to investigate the impact of interactive behavior. Studies have shown that patients’ active “symptom clarification” in multi-round interactions can significantly improve the adoption rate and credibility of diagnostic recommendations. In contrast, single-round interactions may reduce diagnostic efficiency [29,30]. At the psychological behavior level, scholars have widely focused on the impact of patients’ trust in intelligent systems and their perception of the systems’ capabilities on diagnostic effectiveness. Isaac Ng argues that patients skeptical of intelligent systems tend to repeatedly verify diagnostic recommendations, which leads to prolonged diagnosis and treatment time and increased tolerance for errors [31]. In contrast, patients who fully understand the limitations of intelligent systems exhibit higher satisfaction and trust [32]. Stevens et al. note that patients’ subjective perception is a core factor influencing privacy concerns, and those who fully understand the boundaries of intelligent systems often demonstrate higher trust [33]. However, most studies regard trust as a static psychological state. They overlook the dynamic evolution of trust during the interaction process, which varies with the accuracy of diagnostic results and the clarity of system explanations. This results in a superficial understanding of how trust specifically regulates patient behavior. At the level of system quality and design, the naturalness of voice interaction, user-friendliness of interface design, and practicality of functions significantly affect patient collaborative behaviors and medical diagnostic effectiveness [34,35,36,37]. Wienrich et al. found that endowing AI voice assistants with anthropomorphic characteristics in medical settings can enhance patients’ trust in the system, thereby improving diagnostic efficiency [38]. S Wang et al. contend that optimizing functionalities such as user experience within intelligent systems can effectively reduce confusion and uncertainty when users articulate problems through proactive questioning, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy [39].

To summarize, studies in this field exhibit two major limitations: fragmentation and staticity. First, existing literature is fragmented across the aforementioned four dimensions, lacking systematic comparison and integration of the relative importance, causal priority, and interaction mechanisms among factors. Second, most research methods rely on static correlation analysis, failing to effectively capture and model the dynamic and evolutionary essential characteristics in the human–machine collaboration process. This makes it difficult for current studies to reveal the core pathways affecting diagnostic effectiveness. Therefore, this study aims to systematically integrate multi-dimensional factors, go beyond static descriptions, and construct a multi-level hierarchical structural model by introducing the DEMATEL-ISM method. Therefore, this study aims to systematically integrate multi-dimensional factors, go beyond static descriptions, and construct a multi-level hierarchical structural model by introducing the DEMATEL-ISM method.

2.3. Research on the Efficiency of Human–Machine Collaborative Diagnosis Based on SST

The Socio-technical Systems Theory was introduced by Trist et al. in the 1950s [40], aiming to explore the interactive relationship between technology and social organizations. This theory emphasizes the mutual adaptability and interactivity between social and technical subsystems, asserting that the introduction and application of technology must account for societal needs and values. Concurrently, society must actively engage in and guide technological development. Later, Bostrom and Heinen divided the social subsystem into personnel and structural dimensions, while the technical subsystem was subdivided into technological and task-related aspects. Each subsystem operates independently yet interacts with others, forming a dynamic equilibrium system.

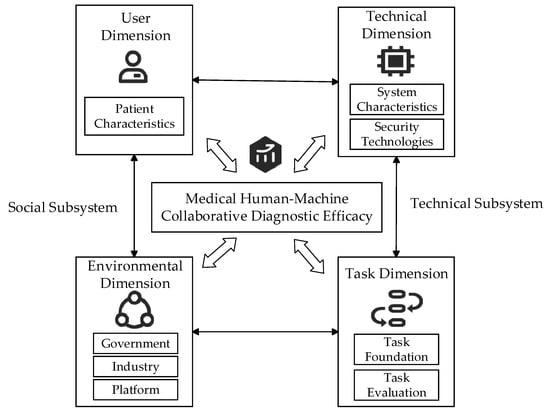

In the field of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis, multi-dimensional influencing factors need to be considered. It is necessary to not only focus on the role of patients’ behaviors in diagnostic effectiveness, but also further incorporate the characteristics of medical intelligent systems, practical evaluation of task effectiveness, and multi-dimensional impacts of environmental factors. Socio-technical Systems Theory provides an effective analytical framework for understanding and optimizing diagnostic effectiveness, as well as for promoting sustainable health services. Sustainable healthcare services have multiple requirements for AI medical intelligent systems. They not only require the systems to have high accuracy and efficiency in diagnosis, but also emphasize their long-term resilience, broad accessibility, and service quality stability under resource constraints [41]. Therefore, a systematic perspective is required when analyzing the effectiveness of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis. In addition to focusing on patients’ cognitive behaviors, system technical levels, and task complexity, external environmental factors must be incorporated into the scope of consideration. To more accurately reflect the actual scenario of medical human–machine collaboration, this study deepens the dimensions of the Socio-technical System Theory. It refines the “structural dimension” in the social subsystem into the “environmental dimension”. Specifically, the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare is jointly influenced by four dimensions: users, technology, tasks, and environment. As core users, patients provide medical data through interaction with medical intelligent systems. The systems are responsible for processing data, generating diagnostic results, and providing personalized services. This process must operate within the constraints of governmental, industry, and platform-specific regulations to ensure diagnostic compliance and safety.

3. Research Methodology and Construction of the System of Influencing Factors

3.1. The DEMATEL-ISM Method

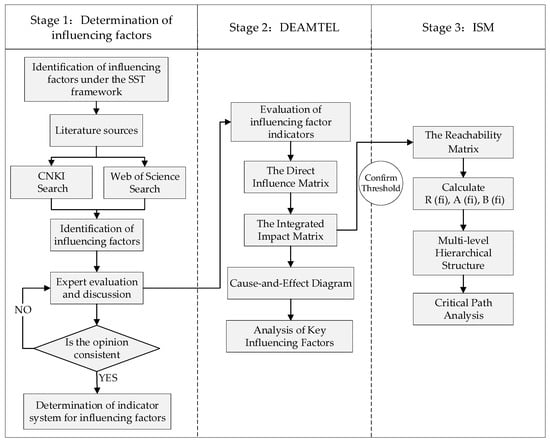

The Decision Experiment and Evaluation Laboratory Method (DEMATEL) was developed under the leadership of A. Gabus and E. Fontela to deconstruct causal relationships within complex systems [42]. This method, grounded in graph theory and matrix operations, calculates the degree of influence, degree of being influence, centrality, and causality degree of each factor by constructing direct influence matrices and comprehensive influence matrices. It ultimately generates a causal relationship diagram that visually represents the interrelationships between factors [43]. The DEMATEL method was initially applied to global complex issues such as energy crises and environmental governance [44], and is now widely employed in fields including business management [45], social sciences [46], and healthcare management [47]. The ISM method, proposed by J. Warfield, is used to analyze the complex structures of socio-economic systems. Through structured modeling, this approach transforms the intricate and ambiguous relationships between system factors into an intuitive hierarchical model, revealing both direct and indirect relationships among elements [48]. DEMATEL provides a quantified measure of causal strength, while ISM constructs hierarchical structures. The integration of DEMATEL and ISM methodologies enables a comprehensive analysis of critical drivers and key evolutionary pathways within complex systems (Figure 1) [49,50]. Specific steps:

Figure 1.

Research Flowchart.

3.2. Development of an Efficiency Metrics Framework for Human–Machine Collaborative Diagnosis

Based on socio-technical systems theory and drawing upon practical scenarios of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare, a theoretical framework is constructed across four dimensions: user, technology, task, and environment. Through systematic literature review, 39 initial influencing factors were identified. Five experts in the medical field were invited for semi-structured interviews. Based on the two criteria of factor importance and independence, after two rounds of expert review, we merged semantically duplicate items (e.g., combining “system response speed” and “timeliness of system feedback” into “system operation capability”), deleted factors with low clinical importance, and supplemented key practical factors. Following two rounds of interviews, the experts’ opinions converged, ultimately distilling 19 key influencing factors, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework of Socio-Technical Systems.

3.2.1. User Dimension

The user dimension primarily concerns patients’ subjective perceptions of the intelligent diagnostic system, encompassing the influence of five factors: perceived health bias, perceived uncertainty, perceived technology usability, perceived service accuracy, and perceived system credibility, as shown in Table 1. Health perception bias refers to the discrepancy between a patient’s subjective perception of their health status and objective medical assessment, arising from a lack of specialized medical knowledge [12,51,52,53,54]. Perceptual uncertainty focuses on the patient’s usage process. It is triggered by patients’ insufficient digital literacy. This uncertainty manifests as cognitive strain and psychological distress stemming from ambiguous information and complex procedures, making outcomes and processes difficult to predict. This uncertainty significantly heightens the risk of diagnostic bias [55,56,57]. Perceived technology usability reflects the psychological closeness patients feel towards intelligent systems, and whether their needs are met during usage. Perceived service accuracy focuses more on the output results of intelligent systems, representing users’ objective assessment of the attributes of the system’s output content [55,56,58]. At the same time, the accuracy of perceived healthcare outcomes is also a key consideration [27,59,60]. The credibility of the perception system is a pivotal factor that permeates the entire diagnostic process and plays a central role, directly determining the patient’s level of trust in the intelligent system [60,61].

Table 1.

User Dimension Influencer Factors.

3.2.2. Technical Dimension

The technical dimension is built around the characteristics of intelligent systems and security technologies, as shown in Table 2. System characteristics serve as the core vehicle for functional implementation, and may be categorized into the foundational layer, core layer, and interaction layer according to the system lifecycle. The foundational layer embodies the system’s knowledge comprehensiveness capability, including the quality of standard datasets such as various disease etiologies, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment methods. It provides a scientific basis for auxiliary diagnosis [62,63,64]. The core layer encompasses system operational capability and processing capability. The former constitutes the foundational performance of the system, encompassing system stability, compatibility, response speed, and fault tolerance [62,65]. The latter relies on big data, machine learning, and other technologies to enhance the system’s abilities in reasoning, induction, creativity, and algorithmic transparency [27,59,66]. The interaction layer encompasses system interaction capability and anthropomorphic capability. System interaction capability refers to the user-friendliness of intelligent system interface design, alongside the accessibility, continuity, and scalability of communication channels with patients and other systems [67,68]. System anthropomorphic capability refers to presenting information to patients in a human-like communication style, thereby offering compassionate care and reducing interpretative biases regarding diagnostic outcomes [61,67]. Security technology primarily concerns data privacy, security, and network communication security within intelligent systems [69,70,71].

Table 2.

Technical Dimension Influencer Factors.

3.2.3. Task Dimension

The task dimension focuses on the implementation process and effectiveness measurement of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare, primarily encompassing task foundations and task evaluation, as shown in Table 3. The task foundation represents the supporting conditions for the execution of diagnostic tasks, encompassing data support and process adaptability. Data support level reflects the quality of data required for intelligent systems. It covers the authoritativeness of data sources, clarity and professionalism of content, data error rate, as well as the readability of tables and images [72,73]. It serves as the foundation for task execution. Process alignment refers to the degree of compatibility, rationality, and standardization between an intelligent system’s workflow and the patient’s cognitive workflow. It focuses on issues such as whether the system adheres to clinical pathways or diagnostic and treatment guidelines, and whether the diagnostic and treatment operation steps are consistent with the doctors’ diagnostic and treatment process. Significant fitting deviations will directly impact the accuracy of the diagnostic process and the patient’s treatment experience [74,75,76].

Table 3.

Task Dimension Influencer Factors.

Task evaluation focuses on an objective, comprehensive assessment of diagnostic efficacy, encompassing service precision and service coordination. The precision of service delivery is reflected in the feedback data generated by intelligent systems when providing a suite of services to patients. The quality of this feedback—whether it is professional and accurate—directly impacts the efficacy of medical diagnosis [77]. Service Synergy Degree focuses on the integration and coherence of processes. In the service process, it enables intelligent systems to drive the personalization, humanization, and feedback mechanisms of medical services, so as to achieve medical support and patient services covering the entire diagnostic process [67,69].

3.2.4. Environmental Dimension

External environmental factors significantly influence diagnostic efficacy and implementation outcomes, primarily through three domains: governmental, industry-specific, and platform-related, as shown in Table 4. The governmental environment establishes reasonable institutional standards and regulatory frameworks for human–machine collaboration in healthcare through policies and regulations [27,78]. For example, the Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services clearly stipulates that the use of AI systems in different scenarios shall comply with ethical and moral standards, data security standards, and statutory procedures. It aims to avoid deviations in diagnostic results caused by data errors, and ensure the reliability of diagnosis and treatment recommendations as well as patients’ privacy protection [79].

Table 4.

Environmental Dimension Influencer Factors.

The industry environment jointly influences the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis through ethical norms and regulatory standards [59,80]. Ethical frameworks define the boundaries for data usage within intelligent systems, addressing ethical dilemmas such as algorithmic bias, patient data management, and privacy and security safeguards. Platform Environment refers to the behavioral systems and norms formulated by the platform. It exerts rigid constraints on patients’ diagnostic behaviors and the use behaviors of intelligent systems, so as to ensure the standardization and controllability of the human–AI collaborative process [81,82].

4. DEMATEL-ISM Analysis

4.1. DEMATEL Method Analysis

4.1.1. The Direct Influence Matrix

Based on the consensus reached through expert interviews, the interrelationships among influencing factors were identified by constructing an expert scoring questionnaire for the indicator system. The survey participants comprised 10 experts in the field of medical artificial intelligence, 5 clinicians, and 5 patient representatives. The scoring system employs a 0–4-point scale (0 indicating no impact, 1 indicating very weak impact, 2 indicating weak impact, 3 indicating strong impact, and 4 indicating very strong impact). Twenty questionnaires were distributed, with 19 valid responses collected. Based on the DEMATEL method, the scoring data from 19 experts were collated to produce an initial relationship matrix of 19 × 19. By calculating the average influence strength between each factor, a direct influence matrix was constructed. Due to space constraints, the direct impact matrix obtained by collating the evaluation results from 19 experts is presented in Table A1 of Appendix A.

4.1.2. Ethical Considerations

This study involved expert consultation with 20 professionals in the field of medical diagnosis. The participants included 10 experts in medical artificial intelligence, 5 clinicians, and 5 patient representatives. Their professional insights were collected regarding the factors influencing the efficiency of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis. The consultation was not designed as a formal research study collecting data for analysis, but rather as a means to obtain expert opinions. Prior to the interview, all participants were informed about the purpose of the consultation, how their responses would be used, and that their participation was voluntary. All 20 experts provided verbal consent to participate, which was documented in written form for official record-keeping. To protect participant anonymity, all responses were anonymized in the final manuscript, with no identifying information (e.g., names, institutional affiliations) included in the published work. Given the nature of this expert consultation (without systematic data collection and without potential risks to participants), formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required.

4.1.3. The Integrated Impact Matrix

After constructing the direct influence matrix, normalization is performed using the row and maximum value method according to Equation (1) to obtain the normalized matrix N. This serves to reduce errors arising from differing dimensions and subjective judgements among various influencing factors. Based on the normalized matrix, Equation (2) is employed to compute the comprehensive influence matrix T for determining the direct and indirect relationships among factors affecting the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis. The standardized matrix N multiplied by itself represents the incremental indirect effects between factors. denotes the sum of all indirect effects. I denotes the identity matrix. The inverse of is . The comprehensive influence matrix is shown in Table A2.

4.1.4. Cause-And-Effect Diagram

Having established the comprehensive influence matrix, calculate the degree of influence Di, degree of being influenced Bi, centrality Mi, and causality Ri for each influencing factor according to Equations (3)–(6). The degree of influence represents the aggregated influence value of each row factor in the comprehensive impact matrix on all other elements. The degree of being influenced represents the aggregate impact value of each factor on all other factors. Centrality is the sum of the impact and being-influenced degrees of each factor, reflecting the significance of the factor within the overall system relationship. Causality is the difference between the influence degree and being influenced degree corresponding to each factor, indicating the extent to which the factor affects the system as a “cause” or its contribution degree. That is, it represents the degree of logical relationship between each factor and other factors.

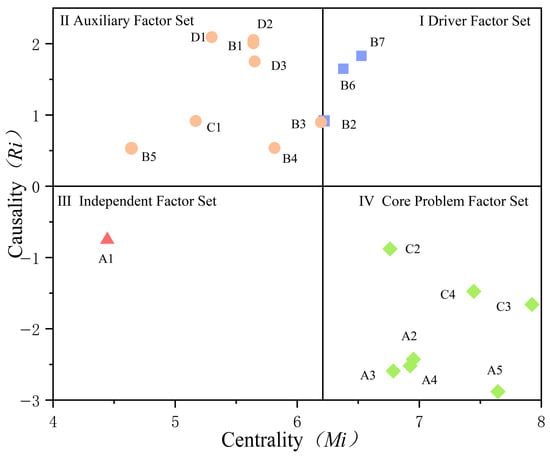

where denotes the factor in row i and column j of the composite influence matrix T. In Table 5, the ranking of causal factors affecting the efficacy of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis is as follows: policy and regulations (D1), industry standards (D2), system knowledge comprehensiveness (B1), network communication security (B7), platform rules (D3), data privacy security (B6), system operational capability (B2), data support level (C1), system processing capability (B3), system interaction capability (B4), and system anthropomorphism capability (B5). These factors exert a significant influence on other elements and should be prioritized as key areas for control in enhancing the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare. For instance, policy and regulations (D1) and industry standards (D2) exert the most significant influence among all factors. By establishing legitimacy, ensuring system stability and security, clarifying responsibilities and obligations, and upholding ethical principles, they create a credible environment for the effective operation of the entire system. Governments should prioritize improving laws, regulations, and systems. They should also strengthen cyber security and privacy protection. This will enhance trust in the use of medical intelligent systems among users and the entire society, thereby influencing other factors.

Table 5.

Centrality and causality of factors influencing the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis.

The ranking of outcome factors is as follows: service precision level (C3), perceived system reliability (A5), service coordination level (C4), perceived uncertainty (A2), perceived service accuracy (A4), perceived technology usability (A3), process adaptability level (C2), and perceived health bias (A1). Among the outcome factors, service precision level (C3) exhibits the highest absolute value and is most susceptible to influence from other factors. It is regarded as a hub indicator for the efficacy of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis. Service accuracy depends both on the fundamental characteristics of technical systems and on user perception. Enhancing the technical underpinnings of medical intelligence systems can improve patient perception. Furthermore, service precision is also influenced by factors such as data privacy and network communication. To more intuitively illustrate the various influencing factors, a cause-effect diagram was plotted (Figure 3) with centrality as the horizontal axis and causality as the vertical axis, using the median centrality value of 6.21 for the 19 factors as an internal auxiliary axis.

Figure 3.

Causes and consequences of factors affecting diagnostic efficacy.

- The three factors in the first quadrant—system operational capability (B2), data privacy security (B6), and network communication security (B7)—exhibit high centrality and causality. These constitute the driving factor set for medical human–machine collaborative diagnostic efficacy, exerting the most significant influence on diagnostic performance.

- The second quadrant’s systemic knowledge comprehensiveness (B1), systemic processing capability (B3), systemic interaction capability (B4), systemic anthropomorphism capability (B5), data support level (C1), policy and regulations (D1), industry standards (D2), and platform rules (D3) exert strong active influence on resultant factors. They serve as important auxiliary factors for medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis.

- Perceived health bias in the third quadrant (A1), exhibiting low centrality and ranking low in causality, indicates that this factor holds limited importance and low associativity within medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis. Its impact on diagnostic efficacy is minimal, constituting an independent factor set.

- The factors in the fourth quadrant, including perceived uncertainty (A2), perceived technology usability (A3), perceived service accuracy (A4), perceived system credibility (A5), and Process adaptability level (C2), Service precision level (C3), and Service coordination level (C4), have high Centrality Degree, and their absolute values of Cause Degree are relatively large. This indicates that these factors are susceptible to the influence of other factors, serve as the key to improving the efficacy of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis, and constitute the core problem factor set.

4.2. Analysis of the ISM Method

ISM (Interpretative Structural Modeling) is a method for analyzing relationships between factors within a system. By constructing an adjacency matrix through the complex relationships or directed graphs between influencing factors, it determines the simplest directed network to achieve the matrix. Then, through methods such as result-first, cause-first, or rotation, a hierarchical topology diagram is obtained, representing the hierarchical network among the various influencing factors.

4.2.1. Construct the Reachability Matrix

Based on the 18 key influencing factors derived from DEMATEL analysis, reconstruct the comprehensive influence matrix T′. Considering the influence of factors themselves, the overall influence matrix F is obtained by adding the composite influence matrix T′ to the identity matrix I. To simplify the system structure, factors with lesser influence within the overall influence matrix F must be eliminated. For this purpose, a threshold λ is introduced. To filter out weak influence relationships between indicators, λ is determined by considering the values of elements within the overall influence matrix. From this matrix, λ values close to the average of 0.164 are selected, specifically set at 0.114, 0.139, 0.164, 0.189, and 0.214. After repeated evaluation and analysis of the node degree at each threshold, and following discussions with experts, it was determined that yields the most appropriate hierarchical structure for the system [83]. In the overall influence matrix, set values below the threshold to 0 and all others to 1 to obtain the reachability matrix K (Table A3). The calculation formulas are shown in Equations (7) and (8).

where nij denotes the element in row i and column j of the overall influence matrix F; Kij denotes the element in row i and column j of the reachability matrix. When Kij equals 1, it indicates that ni exerts a direct influence upon nj; when Kij equals 0, it indicates that ni exerts no direct influence upon nj.

4.2.2. Multi-Level Hierarchical Structure Decomposition

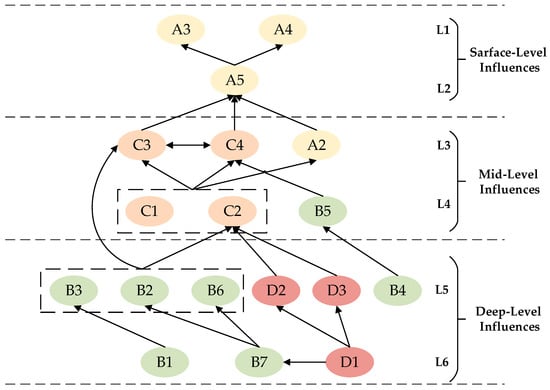

Based on the reachability matrix K, the reachable set R(fi) is computed through result-priority hierarchy processing. This set constitutes the influence exerted by a particular factor within the reachability matrix upon other factors. The antecedent set A(fi) refers to the collection of factors within the reachability matrix that can reach a given factor. The intersection set B(fi) is defined as the intersection of the reachability set and the antecedent set, namely R(fi) ∩ A(fi) = B(fi). Based on the hierarchical processing of reachability sets, antecedent sets, and intersection sets, a multi-level hierarchical structure diagram of the influencing factors for human–machine collaborative diagnostic effectiveness is derived (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Visualization of factors influencing the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis.

Figure 4 categorizes influencing factors into six levels, with L1 and L2 representing surface-level influences factors. Perceived technology usability (A3), perceived service accuracy (A4), and perceived system credibility (A5) are factors directly impacting human–machine collaborative diagnostic efficacy. L3 and L4 represent mid-level influences factors. Service precision level (C3), service coordination level (C4), perceived uncertainty (A2), data support level (C1), process adaptability level (C2), and system anthropomorphism capability (B5) are closely interrelated with both surface-level and deep-level factors. These factors are influenced by deep-level elements while simultaneously driving the evolution and development of surface-level factors. L5 and L6 represent deep-level influences factors: system operational capability (B2), system processing capability (B3), system interaction capability (B4), data privacy security (B6), industry standards (D2), platform rules (D3), System Knowledge Comprehensiveness (B1), Network Communication Security (B7), and Policy and Regulations (D1) constitute the most critical determinants of medical human–machine collaborative diagnostic efficacy. These factors are interrelated while exerting direct or indirect influence upon both surface-level and mid-level factors.

5. Results

A hierarchical structural model of factors influencing the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis was constructed based on the ISM methodology. The specific process for revealing the hierarchical relationships among these factors and their respective pathways of influence is as follows:

5.1. Surface-Level Dependency Factors

Among the surface-level dependency factors (L1–L2), perceived technology usability, perceived service accuracy, and perceived system credibility are key influencing factors at the patient perception level, having the most direct impact on diagnostic efficacy. In human–machine collaboration, regarding perceived technology usability, when system functionality fails to align with patients’ actual needs, it reduces the perceived value of intelligent systems. This diminishes patients’ willingness to adopt these systems, increases decision-making barriers, and may even lead to abandonment. The perceived service accuracy, as the core value of diagnostic efficacy, serves as the primary basis for patients to evaluate the value of intelligent systems. It directly influences patients’ assessment of outcomes and subsequent actions. When patients perceive high accuracy, they establish an initial level of trust in the intelligent system, thereby enhancing its perceived reliability. Sustained trust is crucial for maintaining long-term patient engagement and retention, enabling the provision of more comprehensive and sensitive health data. Perceived inaccuracy erodes trust and leads to system abandonment.

5.2. Mid-Level Interdependent Factors

The composition of mid-level interdependent factors (L3–L4) is relatively complex. Within level L3, service precision level and service coordination level mutually influence each other, and both are jointly affected by data support level and process adaptability level at level L4 alongside perceptual uncertainty. The system’s anthropomorphic capability impacts the service coordination level.

From the user’s perspective of perceptual uncertainty, errors or omissions may occur when patients describe symptoms or upload medical information during medical human–machine collaboration. Such deviations in system input data can induce or exacerbate uncertainty. Additionally, patients’ difficulty in fully understanding information such as diagnostic suggestions output by intelligent systems can further impair the system’s trustworthiness. From the perspective of the system’s anthropomorphic ability in the technical dimension, patients in medical intelligent consultation scenarios are prone to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression due to illness-related distress. Consequently, they tend to demonstrate a strong need for emotional support and humanistic care. Therefore, the anthropomorphic capability of the system, coupled with the collaborative service of intelligent systems, presents diagnostic suggestions and conveys care through natural conversations, emotional responses, and personalized expressions. This enhances patients’ perception of goodwill towards the system and strengthens their trust in it.

In terms of data support level, process adaptability level, service precision level, and service coordination level within the task dimension, service coordination level is a “modulator” of patient perception. Through full-chain services covering pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, and post-diagnosis, it collaborates with service accuracy to regulate patients’ perception of system value. This forms a positive value cycle of “the more it is used, the more trustworthy and accurate it becomes”. It indirectly impacts the effectiveness of human–machine collaborative diagnosis. Data support is the medium and starting link for the effectiveness of human–machine collaborative medical diagnosis. High-quality input data serves as the premise for the system to generate accurate diagnostic suggestions and services. Process adaptability converts medical professional logic into understandable and trustworthy interaction paths for patients. Together, they act on service accuracy, service collaboration, and perceived uncertainty. This indirectly influences patient perception.

5.3. Deep-Level Driving Factors

Deep-level driving factors (L5–L8) constitute the fundamental determinants of the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare, encompassing primarily technological and environmental dimensions.

Technical dimension. System knowledge completeness refers to the capability of medical intelligence systems, following training on high-quality medical datasets, to reduce rates of missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses while providing more accurate and reliable clinical recommendations. The operational capability, processing capability, and interaction capability of the system provide patients with intelligent systems featuring strong stability, fast responsiveness, robust reasoning and induction abilities, and high algorithmic transparency. This positively influences patients’ perceived value of the system. It also indirectly acts on diagnostic effectiveness. Data privacy security and network communication security directly impact patient perception. When patients perceive that intelligent systems may infringe on their personal privacy or that data transmission is insecure, due to concerns about privacy and security, they will not provide true and complete data. They may even abandon the system entirely. Therefore, data privacy and communication security within medical intelligence systems are crucial factors that influence diagnostic efficacy.

Environmental dimension. Policies and regulations guide the medical industry and medical platforms to standardize the application of intelligent medical systems through institutional standards and regulatory frameworks. They also promote and guide the general public’s trust in intelligent medical systems. Industry standards serve as binding constraints for medical ethics, technical specifications, and regulatory implementation, ensuring the safety and reliability of systems. Platform rules establish behavioral standards for patients using medical intelligence systems, such as standardized operational guidelines and data specifications. They provide support for patient trust and the system’s technical capabilities.

5.4. Key Action Pathways

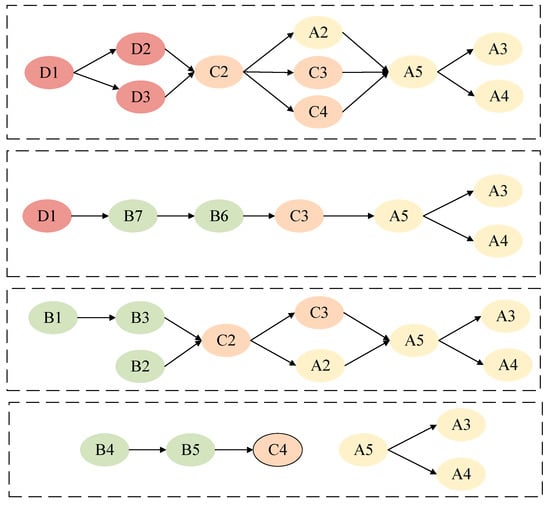

To enhance the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare, improve the efficiency of medical diagnostic decision-making, and optimize the allocation of healthcare resources, four key pathways promoting the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare have been identified from a multi-level hierarchical diagram featuring diverse relationships (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Pathways to enhancing the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis.

- Environmental Pathway: Policy and Regulations D1 → (Industry Standards D2, Platform Rules D3) → Process Adaptability Level C2 → (Perceived Uncertainty A2, Service Precision Level C3, Service Coordination Level C4) → Perceived System Credibility A5 → (Perceived Technology Usability A3, Perceived Service Accuracy A4);

- Security Technology Pathway: Policy and Regulations D1 → Network Communication Security B7 → Data Privacy Security B6 → Service Precision Level C3 → Perception System Credibility A5 → (Perception Technology Usability A3, Perception Service Accuracy A4);

- System Foundational Capability Pathway: System Knowledge Comprehensiveness B1 → System Processing Capability B3 → System Operational Capability B2 → Process Adaptability Level C2 → (Service Precision Level C3, Perceived Uncertainty A2) → Perceived System Credibility A5 → (Perceived Technology Usability A3, Perceived Service Accuracy A4);

- System Interaction Capability Path: System Interaction Capability B4 → System Anthropomorphism Capability B5 → Service Coordination Level C4 → Perceptual System Credibility A5 → (Perceptual Technology Usability A3, Perceptual Service Accuracy A4).

These four pathways demonstrate that environmental factors—policy and regulations, industry standards, and platform rules—serve as foundational institutional underpinnings throughout the entire human–machine collaborative diagnosis process, thereby bolstering patient trust and the system’s technical capabilities. Security technologies (data privacy security, network communication security) and foundational system capabilities (system knowledge comprehensiveness, system operational capability) are key drivers of diagnostic efficacy. Interaction capabilities and service precision level exert their influence on patient perception through task-related mediating factors, ultimately shaping the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare.

6. Discussion

This study establishes an influence mechanism model for the effectiveness of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis using the ISM method. It clearly reveals that the influencing factors do not exist in isolation, but instead follow a hierarchical driving logic from “environmental support” to “patient perception.” Based on the structural relationships and causal hierarchies, this study proposes systematic strategies to improve the effectiveness of medical human–AI collaborative diagnosis. Specifically, it is necessary to start from four dimensions: patient perception, service collaboration, technical support, and environmental support. Special attention should be paid to the supporting role of environmental and technical factors in patient trust and system capabilities. Therefore, the following countermeasures and suggestions are proposed:

6.1. Enhancing Patient Perception: Dual-Pronged Approach of Health Literacy and System Trust

The patient perception level is a critical entry point for enhancing the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare. Therefore, improving patient perception not only needs to start from the superficial level of patients themselves, but also requires the adoption of systematic driving strategies. On one hand, efforts should be made to enhance patients’ medical knowledge reserve and cognitive ability regarding intelligent diagnosis and treatment through health literacy improvement programs. Specifically, governments, healthcare institutions and social organizations should collaborate to conduct multi-tiered, multi-format medical science outreach activities. The focus should be on popularizing basic medical knowledge and the advantages of intelligent diagnosis and treatment systems. This helps patients accurately describe their symptoms and understand diagnostic recommendations. Thereby, it reduces perceived uncertainty. For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has launched the “Health Information and eHealth Education (HealthIT.gov)” initiative. It provides patient resources and educational activities, particularly focusing on electronic health records (EHRs) and AI-based diagnostic medical tools. This aims to streamline the processes of disease management and data sharing [84]. On the other hand, the establishment of patients’ trust in intelligent systems needs to be combined with the driving factors revealed by the model. Governments should improve laws and policies related to intelligent medical systems and clarify the ownership of rights and responsibilities. Medical institutions should leverage their professional credibility to enhance patients’ trust in the systems through transparent service processes and promotion of typical cases. Meanwhile, at the technical level, efforts should be made to strengthen data privacy security and system operation stability, providing reliable technical support for patients.

6.2. Optimizing Service Synergy: Dual Enhancement of Precision Services and Process Alignment

Service collaboration is not only a manifestation of technical capabilities, but also a link in shaping patients’ direct experiences. It is recommended to optimize service processes by focusing on two dimensions: service precision level and service coordination level. Firstly, medical institutions should strengthen the integration of full-chain services covering pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, and post-diagnosis. By virtue of accurate consultation guidance, personalized diagnostic recommendations, and continuous health monitoring, they can enhance patients’ perception of service value. Secondly, service processes should take full account of patients’ actual needs and optimize human–AI interaction interfaces and operational pathways. This is aimed at mitigating usage barriers caused by task complexity as revealed in the model. In addition, the enhancement of the system’s anthropomorphic capabilities (such as natural language interaction and emotional expression) can further strengthen patients’ perception of goodwill, thereby fostering trust. For example, in the HealthIT initiative, medical institutions utilize EHRs to integrate patients’ pre-diagnostic medical history, intra-diagnostic feedback, and post-diagnostic rehabilitation advice. This provides patients with a higher-quality diagnostic experience. Meanwhile, the initiative also aims to reduce operational complexity through disease management and simplified patient-system interactions. This thereby facilitates the establishment of deep-seated trust.

6.3. Strengthening Technical Support: Dual Safeguards for System Capability and Data Security

The technical dimension not only accepts norms from underlying environmental factors but also directly determines the quality-of-service output and the foundation of patient trust. Firstly, efforts should focus on continuously enhancing the knowledge completeness and operational capabilities of medical intelligence systems. And EHR achieves this by integrating relevant patient data and supporting AI algorithm training for medical intelligent systems. It reduces the rates of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis, and improves the accuracy of diagnostic recommendations when patients participate in medical human–machine collaboration. Secondly, data privacy and security, along with network communication security, form the bedrock of patient trust. It is recommended that technical measures such as encrypted transmission and privacy-preserving algorithms be employed to ensure the security and confidentiality of patient data. Furthermore, the system’s interactivity and service adaptability require further optimization to enhance patients’ perceived value of the intelligent system.

6.4. Enhancing Environmental Safeguards: Systematic Development of Policy Standards and Platform Regulations

Environmental factors, which serve as the institutional foundation for the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare, require attention at three levels: policy and regulations, industry standards, and platform rules. Firstly, governments should accelerate the construction of policies and regulations for intelligent medical systems. They should clarify service boundaries, responsibility attribution, and supervision mechanisms, so as to provide institutional guarantees for the widespread application of such systems. Secondly, the formulation of industry standards should focus on harmonizing medical ethics, technical specifications and regulatory implementation to ensure the safety and reliability of medical intelligent systems. Finally, the improvement of platform rules should focus on the standardized guidance of patients’ behaviors. For instance, through operation guidelines and data specifications, it can help patients use intelligent diagnosis and treatment systems correctly and improve the quality and completeness of system input data.

6.5. Critical Path Optimization: Systematic Enhancement from Environment to Perception

Optimization will be undertaken across the following four aspects, based on four key pathways: Firstly, we should strengthen the linkage effect between the environment and technology. By virtue of the synergy between policies and regulations and technical means, we can improve the system’s security and basic capabilities, so as to provide underlying support for patient perception. Secondly, optimize the precision and coordination of services. By refining service processes and enhancing service capabilities, we can strengthen patients’ trust in the system and their willingness to use it. Thirdly, we should improve the interaction capability and data quality. By virtue of naturalized interaction design and data privacy protection, we can enhance patients’ user experience and the quality of data input. Fourthly, we should establish a positive feedback loop. By virtue of accurate services and continuous accumulation of trust, we can form a value loop of “the more it is used, the more reliable and accurate it becomes”, and thereby promote the continuous improvement of diagnostic effectiveness.

In summary, enhancing the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis in healthcare requires addressing both superficial factors and systematically optimizing underlying factors. By virtue of health literacy improvement, service process optimization, technical capability enhancement, and environmental norm improvement, we can achieve the two-way improvement of patients’ trust and system capabilities. And thereby, it promotes the continuous improvement of the effectiveness of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis.

7. Conclusions

Based on Socio-technical Systems Theory, an indicator system consisting of 19 factors across four dimensions was established to investigate the factors influencing the efficacy of human–machine collaborative diagnosis from the patient’s perspective. Using the DEMATEL method, the causal relationships affecting the efficacy of medical human–machine collaborative diagnosis were identified, and 18 key influencing factors were determined. On this basis, the ISM methodology intuitively presents the hierarchical structure of key influencing factors. It reveals a systematic mechanism that operates from deep-seated drivers to surface-level manifestations: Environmental support and technical support, as deep-seated root factors, drive mid-level service collaboration and task adaptation through multiple key pathways, including safety technology, basic capabilities, and interaction capabilities. They ultimately exert an effective impact on the surface-level patient perception. This forms a complete functional chain of “institutional guarantee—technical implementation—service transmission—perception response”.

However, this study has certain limitations. On one hand, the construction of the research model is based on experts’ subjective judgments. Although we have strived for robustness by integrating the opinions of multiple experts, individual differences, and subjective perception, the model needs to be improved by enhancing model sensitivity or adopting more scientific modeling methods. They can also attempt to collect larger-scale expert data to conduct cross-group robustness tests on the model. On the other hand, the factor system of this study aims for universality, but it fails to fully consider the heterogeneity of different patient groups. Future research can further explore the applicability and differences in this model in specific user portraits. This will promote the design of more personalized medical human–computer collaboration schemes. It will be a key step in advancing the in-depth application of AI healthcare in sustainable health services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; project administration, S.L.; writing—original draft, J.M. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 23BTQ068.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all participants in this study for providing valuable data that significantly contributed to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Below are the collated evaluation results from 19 experts, including the direct influence matrix obtained by calculating the average impact intensity between various factors, the comprehensive influence matrix derived through normalization processing, and the reachability matrix constructed based on the comprehensive impact matrix.

Table A1.

The direct influence matrix.

Table A1.

The direct influence matrix.

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| A1 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 1.68 | 2.37 | 2.16 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 1.79 | 1.11 | 2.05 | 1.74 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| A2 | 1.68 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 2.63 | 2.26 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 1.74 | 2.00 | 2.16 | 1.89 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| A3 | 0.42 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 2.11 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 2.11 | 1.95 | 1.84 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

| A4 | 1.68 | 2.79 | 2.21 | 0.00 | 2.74 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 1.32 | 1.53 | 2.42 | 1.89 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.42 |

| A5 | 1.53 | 2.11 | 2.89 | 2.53 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.89 | 1.89 | 1.58 | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| B1 | 2.68 | 2.32 | 2.58 | 3.32 | 2.95 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 3.32 | 2.00 | 1.21 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 1.53 | 2.00 | 3.58 | 2.53 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| B2 | 0.89 | 2.16 | 2.68 | 2.42 | 2.84 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 1.63 | 1.37 | 2.00 | 0.58 | 2.74 | 2.58 | 2.63 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.37 |

| B3 | 0.53 | 2.32 | 2.58 | 3.26 | 3.26 | 1.58 | 2.37 | 0.00 | 2.21 | 1.58 | 1.32 | 1.16 | 0.74 | 2.21 | 3.32 | 2.58 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| B4 | 0.53 | 2.21 | 3.21 | 2.32 | 2.58 | 0.63 | 1.95 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 2.74 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 2.74 | 2.32 | 2.95 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| B5 | 0.42 | 1.89 | 2.37 | 1.95 | 2.37 | 0.58 | 1.37 | 1.42 | 2.47 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 2.00 | 1.63 | 2.53 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| B6 | 0.47 | 2.42 | 1.89 | 1.74 | 3.47 | 1.26 | 2.58 | 1.47 | 1.32 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 3.53 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 1.47 | 0.74 | 2.84 | 2.95 | 3.11 |

| B7 | 0.47 | 2.58 | 1.84 | 1.74 | 3.47 | 1.11 | 2.53 | 1.95 | 1.32 | 0.84 | 3.42 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 2.11 | 1.05 | 3.00 | 3.05 | 3.11 |

| C1 | 3.05 | 2.37 | 1.68 | 1.95 | 1.58 | 2.21 | 1.21 | 1.42 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 3.42 | 2.42 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| C2 | 1.16 | 2.53 | 2.84 | 2.21 | 2.53 | 0.68 | 1.79 | 1.42 | 1.84 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 2.53 | 2.89 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| C3 | 2.42 | 2.84 | 2.53 | 3.63 | 3.37 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 1.37 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 1.95 | 0.00 | 3.32 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| C4 | 1.47 | 2.42 | 2.42 | 2.21 | 2.95 | 0.79 | 1.21 | 1.26 | 1.74 | 1.63 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 2.26 | 2.79 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

| D1 | 0.47 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 1.42 | 1.26 | 1.16 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 3.16 | 3.32 | 1.32 | 1.42 | 1.84 | 1.74 | 0.00 | 3.47 | 3.26 |

| D2 | 0.37 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 1.05 | 1.74 | 1.47 | 1.63 | 1.68 | 1.16 | 3.16 | 3.11 | 1.32 | 1.58 | 1.89 | 2.11 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 3.26 |

| D3 | 0.42 | 1.89 | 1.68 | 0.95 | 2.05 | 1.42 | 1.68 | 1.63 | 1.68 | 1.42 | 2.95 | 2.84 | 1.74 | 1.47 | 2.05 | 2.11 | 1.26 | 1.63 | 0.00 |

Table A2.

The comprehensive influence matrix.

Table A2.

The comprehensive influence matrix.

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| A1 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| A2 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| A3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| A4 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| A5 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| B1 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| B2 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| B3 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| B4 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| B5 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| B6 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| B7 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| C1 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| C2 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| C3 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| C4 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| D1 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| D2 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| D3 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

Table A3.

The Reachability Matrix.

Table A3.

The Reachability Matrix.

| A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| A2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

References

- Shastry, K.A.; Sanjay, H.A. Cancer Diagnosis Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 2641–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Chang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Screening/Diagnosis of Pediatric Endocrine Disorders through the Artificial Intelligence Model in Different Language Settings. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 2655–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-Performance Medicine: The Convergence of Human and Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Creamer, G.G.; Ning, Y.; Ben-Zvi, T. Healthcare Sustainability: Hospitalization Rate Forecasting with Transfer Learning and Location-Aware News Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, F.; Chen, N.; Chen, J. The Impacts of Technology Shocks on Sustainable Development from the Perspective of Energy Structure—A DSGE Model Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijor, S.; Rallis, G.; Lad, N.; Gokcen, E. Patient Safety Issues from Information Overload in Electronic Medical Records. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e999–e1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asan, O.; Bayrak, A.E.; Choudhury, A. Artificial Intelligence and Human Trust in Healthcare: Focus on Clinicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, S.; Zhuang, Q.; Gong, B. Human-Computer Interaction Based Interface Design of Intelligent Health Detection Using PCANet and Multi-Sensor Information Fusion. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 216, 106637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Liu, X.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, V. Can Bots Help Create Knowledge? The Effects of Bot Intervention in Open Collaboration. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 148, 113601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M.; Wu, T.-J.; Wu, Y.J.; Goh, M. Systematic Literature Review of Human–Machine Collaboration in Organizations Using Bibliometric Analysis. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 2920–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishowo-Oloko, F.; Bonnefon, J.-F.; Soroye, Z.; Crandall, J.; Rahwan, I.; Rahwan, T. Behavioural Evidence for a Transparency–Efficiency Tradeoff in Human–Machine Cooperation. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Cha, D. Human–Machine Cooperation Meta-Model for Clinical Diagnosis by Adaptation to Human Expert’s Diagnostic Characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Malviya, R.; Verma, S. Personalized Medicine: Advanced Treatment Strategies to RevolutionizeHealthcare. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ying, B.; Wang, C. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Artificial Intelligence Methods in Medical Imaging for Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-G.; Jun, S.; Cho, Y.-W.; Lee, H.; Kim, G.B.; Seo, J.B.; Kim, N. Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: General Overview. Korean J. Radiol. 2017, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGenity, C.; Clarke, E.L.; Jennings, C.; Matthews, G.; Cartlidge, C.; Freduah-Agyemang, H.; Stocken, D.D.; Treanor, D. Artificial Intelligence in Digital Pathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, L.; Meek, D.; Leontidis, G.; Campbell, M.; Harrison, E.; Anderson, L. The Clinical Practice Integration of Artificial Intelligence (CPI-AI) Framework: A Proposed Application of IDEAL Principles to Artificial Intelligence Applications in Trauma and Orthopaedics. Bone Jt. Res. 2024, 13, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, L. Advances in the Application of Human-Machine Collaboration in Healthcare: Insights from China. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1507142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, A.; Colella, T.J.F.; Pakosh, M.; Khan, S.S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Virtual Rehabilitation for People Living in the Community: A Scoping Review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, O.O.; Mustofa, J.; Daley, M.J.; Walton, D.; Tawiah, A. Current Applications and Outcomes of AI-Driven Adaptive Learning Systems in Physical Rehabilitation Science Education: A Scoping Review Protocol. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoy, I.A.; Hassan, O. AI-Driven Technology in Heart Failure Detection and Diagnosis: A Review of the Advancement in Personalized Healthcare. Symmetry 2025, 17, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.; Hanna, M.; Wheeler, R.; Camp, R.; Scott, A.; Nguyen, F.; Oehrlein, E.; Perfetto, E. Patient Centered Special Interest Group Lg What Do We Mean by Patient Engagement? A Qualitative Content Analysis of Current Definitions. Value Health 2018, 21, S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keij, S.M.; Lie, H.C.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Kunneman, M.; De Boer, J.E.; Moaddine, S.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Pieterse, A.H. Patient-Related Characteristics Considered to Affect Patient Involvement in Shared Decision Making about Treatment: A Scoping Review of the Qualitative Literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 111, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.T.; Amara, D.; Bhattacharya, A.; Wei, M.L. Patient and General Public Attitudes towards Clinical Artificial Intelligence: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e599–e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Lei, W.; Lam, W.; Chua, T.-S. A Survey on Proactive Dialogue Systems: Problems, Methods, and Prospects. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgetti, C.; Contissa, G.; Basile, G. Healthcare AI, Explainability, and the Human-Machine Relationship: A (Not so) Novel Practical Challenge. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1545409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaebel, J.; Wu, H.-G.; Oeser, A.; Cypko, M.A.; Stoehr, M.; Dietz, A.; Neumuth, T.; Franke, S.; Oeltze-Jafra, S. Modeling and Processing Up-to-Dateness of Patient Information in Probabilistic Therapy Decision Support. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 104, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meskó, B. Prompt Engineering as an Important Emerging Skill for Medical Professionals: Tutorial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e50638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, F.; Islam, Y.Z.; Furtado, N.; Burns, C. Trust and Accuracy in AI: Optometrists Favor Multimodal AI Systems over Unimodal for Glaucoma Diagnosis in Collaborative Environment. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 198, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I.S.H.; Siu, A.; Han, C.S.J.; Ho, O.S.H.; Sun, J.; Markiv, A.; Knight, S.; Sagoo, M.G. Evaluating a Custom Chatbot in Undergraduate Medical Education: Randomised Crossover Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Performance, Utility, and Perceptions. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P.; Kariotis, T. Ethics and Law in Research on Algorithmic and Data-Driven Technology in Mental Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e24668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.F.; Stetson, P. Theory of Trust and Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence Technology (TrAAIT): An Instrument to Assess Clinician Trust and Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 148, 104550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasey, B.; Ursprung, S.; Beddoe, B.; Taylor, E.H.; Marlow, N.; Bilbro, N.; Watkinson, P.; McCulloch, P. Association of Clinician Diagnostic Performance with Machine Learning–Based Decision Support Systems: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e211276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, K.L.; Mayhorn, C.B. It’s Not What You Say but How You Say It: Examining the Influence of Perceived Voice Assistant Gender and Pitch on Trust and Reliance. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 106, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S.; Gohil, K. Can We Trust a Chatbot like a Physician? A Qualitative Study on Understanding the Emergence of Trust toward Diagnostic Chatbots. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 165, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiseh, M.; Simkute, A.; Zieni, B.; Jiang, N.; Ali, R. C-XAI: A Conceptual Framework for Designing XAI Tools That Support Trust Calibration. J. Responsible Technol. 2024, 17, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienrich, C.; Reitelbach, C.; Carolus, A. The Trustworthiness of Voice Assistants in the Context of Healthcare Investigating the Effect of Perceived Expertise on the Trustworthiness of Voice Assistants, Providers, Data Receivers, and Automatic Speech Recognition. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 685250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Z. Roles of Artificial Intelligence Experience, Information Redundancy, and Familiarity in Shaping Active Learning: Insights from Intelligent Personal Assistants. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 2525–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]