Abstract

In order to address challenges in small object recognition for remote sensing imagery—including high model complexity, overfitting with small samples, and insufficient cross-scenario generalization—this study proposes CAGM-Seg, a lightweight recognition model integrating multi-attention mechanisms. The model systematically enhances the U-Net architecture: First, the encoder adopts a pre-trained MobileNetV3-Large as the backbone network, incorporating a coordinate attention mechanism to strengthen spatial localization of min targets. Second, an attention gating module is introduced in skip connections to achieve adaptive fusion of cross-level features. Finally, the decoder fully employs depthwise separable convolutions to significantly reduce model parameters. This design embodies a symmetry-aware philosophy, which is reflected in two aspects: the structural symmetry between the encoder and decoder facilitates multi-scale feature fusion, while the coordinate attention mechanism performs symmetric decomposition of spatial context (i.e., along height and width directions) to enhance the perception of geometrically regular small targets. Regarding training strategy, a hybrid loss function combining Dice Loss and Focal Loss, coupled with the AdamW optimizer, effectively enhances the model’s sensitivity to small objects while suppressing overfitting. Experimental results on the Xingtai black and odorous water body identification task demonstrate that CAGM-Seg outperforms comparison models in key metrics including precision (97.85%), recall (98.08%), and intersection-over-union (96.01%). Specifically, its intersection-over-union surpassed SegNeXt by 11.24 percentage points and PIDNet by 8.55 percentage points; its F1 score exceeded SegFormer by 2.51 percentage points. Regarding model efficiency, CAGM-Seg features a total of 3.489 million parameters, with 517,000 trainable parameters—approximately 80% fewer than the baseline U-Net—achieving a favorable balance between recognition accuracy and computational efficiency. Further cross-task validation demonstrates the model’s robust cross-scenario adaptability: it achieves 82.77% intersection-over-union and 90.57% F1 score in landslide detection, while maintaining 87.72% precision and 86.48% F1 score in cloud detection. The main contribution of this work is the effective resolution of key challenges in few-shot remote sensing small-object recognition—notably inadequate feature extraction and limited model generalization—via the strategic integration of multi-level attention mechanisms within a lightweight architecture. The resulting model, CAGM-Seg, establishes an innovative technical framework for real-time image interpretation under edge-computing constraints, demonstrating strong potential for practical deployment in environmental monitoring and disaster early warning systems.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing image recognition constitutes a fundamental component of Earth observation systems, serving as the core technology for automated geographic information extraction [1]. Its advancement has substantially strengthened decision-making capacities in environmental monitoring, resource management, and emergency response, highlighting its critical importance. The field’s progress is propelled by continuous methodological innovations. Multimodal data processing achieves feature complementarity through optical-SAR fusion, significantly enhancing information extraction accuracy in complex environments [2]. Methodological advances include ensemble learning-based classifiers [3], multi-architecture hybrid networks [4], Transformer–CNN integrated models [5], Mamba-based multimodal fusion networks [6], and CNN–graph neural hybrid change detection systems [7], collectively advancing technical frontiers.

Computational paradigm innovations have created new research pathways. Novel implementations of diffractive neural networks [8] and hybrid quantum self-attention architectures [9] have expanded remote sensing image processing possibilities. To overcome labeled data scarcity, meta-learning frameworks [10], few-shot learning algorithms [11], scribble annotation-based weakly supervised methods [12], and noisy label correction mechanisms [13] effectively improve model adaptability in data-limited contexts. Multimodal collaborative processing integrating optical, SAR, and LiDAR data demonstrates particular value in specialized applications including forest mapping [14] and coastline monitoring [15]. Additional breakthroughs—spanning global-local feature aggregation networks [16], multi-level feature enhancement methods [17], physics-data driven model fusion [18], lightweight multi-source interpretation frameworks [19], and real-time landslide monitoring networks [20]—collectively establish a robust methodological foundation for ongoing research and practical deployment.

Recent research emphasizes the synergistic optimization of lightweight design and generalization capability. For lightweight implementation, tensor decomposition-based dimensionality reduction enables structured parameter pruning that substantially decreases model complexity and storage requirements, facilitating edge computing deployment [21]. Concurrently, field-deployable detection frameworks integrate multi-scale attention with efficient feature learning modules, maintaining detection robustness and adaptability under constrained computational resources [22]. In generalization theory, maximum correntropy criteria provide rigorous mathematical frameworks for characterizing deep convolutional network generalization bounds [23], while emerging out-of-distribution validation methods establish new standards for assessing model reliability through decision logic consistency analysis [24]. Notably, visual prompt integration with large language models [25] and hyperspectral foundation model architectures [26] create unified multi-task learning paradigms with cross-modal knowledge transfer, substantially expanding geographical adaptability and application scope.

Nevertheless, significant challenges persist in achieving efficient model lightweighting. Research shows that compression strategies like parameter pruning often sacrifice the extraction of fine-grained image features for reduced complexity [21]. Lightweight detectors frequently exhibit suboptimal feature fusion in complex scenes [22], while the ecological validity of maximum correntropy-based generalization theory remains unverified [23]. Emerging vision-language and hyperspectral foundation models also require further refinement to maintain efficiency [25,26]. These limitations collectively impede model deployment in edge environments, making the trade-off between compression, representational power, and generalization a pivotal research frontier [27].

To address these challenges, this study proposes CAGM-Seg—an innovative segmentation method founded on the deep fusion of multiple attention mechanisms. Unlike existing lightweight architectures that merely stack attention modules, our approach enables the synergistic integration of attention mechanisms, significantly enhancing feature learning capabilities with limited samples while substantially improving recognition accuracy for small targets. Building on this foundation, we introduce a novel lightweight network architecture and training strategy that achieves an optimal balance between model complexity and performance while drastically reducing parameter count. This design enables exceptional adaptability and generalization in complex, dynamic remote sensing environments.

Inspired by the pervasive geometric symmetry observed in natural and man-made geographic features—such as the linear symmetry of river networks and the approximate radial symmetry of landslide scars—this study systematically incorporates a symmetry-aware design paradigm into the lightweight architecture. This paradigm extends beyond conventional structural symmetries (e.g., encoder–decoder symmetry) to encompass functional symmetry in feature processing. Specifically, the coordinate attention mechanism symmetrically decomposes the global spatial context along height and width dimensions, allowing the model to more effectively capture directional and structural patterns of small objects. This symmetry-aware approach enhances feature representation consistency and significantly improves localization accuracy for structured small targets across diverse remote sensing scenarios.

A hierarchical evaluation framework was established to systematically validate the proposed method. Black and odorous water body detection serves as the core task, representing key small-sample challenges: these water bodies typically appear as small targets with weak, easily corrupted spectral features and scarce training samples [28]. The framework incorporates landslide detection and cloud detection as extended tasks to form multi-dimensional evaluation criteria. Landslide detection demands effective feature representation of morphologically diverse targets under limited samples [29], while cloud detection requires precise identification of small targets such as thin and scattered clouds under small-sample constraints [30]. Progressing from typical small-sample tasks to diverse land cover types, this framework provides comprehensive validation of lightweight model performance in practical remote sensing scenarios.

In summary, the proposed CAGM-Seg method achieves significant improvements in mitigating model overfitting under small-sample scenarios, enhancing recognition capabilities for small targets, and boosting model generalization. It also represents a major breakthrough in balancing model lightweighting and performance. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- An innovative attention fusion mechanism is proposed, effectively enhancing the model’s feature learning capability under limited training samples and significantly suppressing overfitting caused by data scarcity.

- (2)

- A multi-level feature fusion and enhancement strategy was constructed, strengthening the ability to distinguish and locate small targets, thereby maintaining high recognition accuracy even in complex backgrounds.

- (3)

- Through the synergistic design of lightweight network architecture and training strategies, the model’s cross-scenario adaptability and generalization performance are significantly improved while effectively controlling model complexity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Remote Sensing Image Sources and Preprocessing

This study utilizes nine GF-2 satellite images covering the Xingtai City area in Hebei Province, China, acquired between June and August 2024 and sourced from the https://sasclouds.com platform. Specific acquisition dates are provided in Table 1. The panchromatic and multispectral images underwent orthorectification and geometric registration before mosaicking. Pan-sharpening was then applied to generate high-precision imagery with 0.8 m panchromatic resolution [31,32]. The fused imagery was subsequently clipped to the study area’s vector boundaries to obtain target images for analysis. Band characteristics and spatial resolutions are detailed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Temporal Distribution of Remote-Sensing Imagery.

Table 2.

Spatial Resolution and Wavelength Range of GF-2 Satellite Bands.

2.2. Dataset Preparation

2.2.1. The Datasets Not Yet Augmented

The Black and Odorous Water Body Detection Dataset (BOWD) for Xingtai City, Hebei Province (geographic coordinates: 36°50′−37°47′ N, 113°52′−115°49′ E) was constructed using the sliding window method [33,34] based on the preprocessed GF-2 imagery. The specific process is as follows: A fixed 256 × 256-pixel window slides row by row and column by column across the image at a preset stride. Each movement crops out an image block sample. The total number of image blocks generated is calculated using Formula (1).

where and denote the height and width of the input image, respectively; is the stride of the sliding window; and is the total number of samples calculated. Through field surveys, this study identified 17 black and odorous water body areas in Xingtai City, from which 20 target samples were extracted using this method. This area was selected as a test case to evaluate the model’s recognition capability and generalization performance in complex inland urban water environments.

The landslide data (LSDB) employed in this study were adopted from Ji et al. (2020) a public landslide detection dataset [35]. Constructed with Beijing-2 satellite imagery and centered on Bijie City, Guizhou Province (26°51′−27°46′ N, 105°36′−106°43′ E), this dataset captures the complex mountainous terrain of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau—characterized by pronounced topographic variation, intricate geology, and frequent landslides of diverse morphology. This setting offers a representative environment for evaluating model generalization across heterogeneous landscapes. The original dataset contains 2773 sample images of 512 × 512 pixels, comprising 770 landslide (target) samples and 2003 non-landslide samples [35]. To improve sample quality and meet model input specifications, this study first excluded samples with less than 3% landslide pixel coverage to ensure label reliability, then uniformly cropped retained samples to 256 × 256 pixels to enhance local feature perception. Following this quality control, 656 high-quality target samples were retained for subsequent model training and evaluation.

The cloud detection data in this study were sourced from the publicly available HRC_WHU dataset released by Li et al. (2019) [36]. This global dataset incorporates multi-source satellite imagery (Landsat-8, Sentinel, etc.) collected via Google Earth from diverse geographic and climatic regions, with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.5 to 15 m, ensuring broad environmental representativeness and scale diversity. The original 900 samples (512 × 512 pixels) feature cloud masks professionally annotated by Wuhan University to ensure labeling accuracy [36]. This dataset serves as a testbed for evaluating model adaptability across varying atmospheric conditions, terrain types, and imaging scales—crucial for validating cross-regional and cross-sensor generalization. To enhance data quality and meet model requirements, invalid samples with cloud coverage below 3% were first discarded. Retained samples were then uniformly cropped to 256 × 256 pixels to improve consistency and local feature representation. Ultimately, 3366 high-quality cloud detection samples were obtained for model training and evaluation.

2.2.2. The Augmented Datasets

To address the limited number of target samples in the research dataset, this study systematically employed image augmentation techniques to expand the data volume [37]. Specific augmentation methods included: random horizontal or vertical flipping to modify spatial distribution; random rotation within the range of −30° to 30° to introduce directional variation; random translation of −20 to 20 pixels to simulate different imaging perspectives; integrated adjustments of brightness, contrast, saturation, and sharpness combined with Gaussian noise for color perturbation to enhance the robustness of spectral features [38]; and a fusion augmentation strategy that randomly combines multiple transformations to further improve feature representation diversity [39,40]. Table 3 summarizes the application frequency of each augmentation method. Selected examples of enhanced samples are shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Application Frequency of Each Augmentation Method.

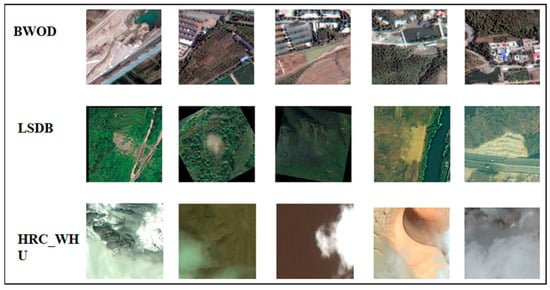

Figure 1.

Typical augmented samples (256 × 256 pixels) from the corresponding dataset.

During the augmentation process, all original target samples were preserved, and multiple augmented versions were generated using the aforementioned methods. To ensure sample quality, a target pixel ratio threshold of 0.03 was established, with only augmented samples meeting this criterion being retained. The detailed composition of the augmented dataset is presented in Table 4. The augmented samples demonstrated significant improvements in both quantity and feature diversity, encompassing variations across multiple dimensions including spatial structure, geometric orientation, and spectral response. This diversified sample representation more accurately reflects the variability of actual imaging environments, establishing a reliable data foundation for high-precision target identification and continuous monitoring [41,42].

Table 4.

Dataset Composition.

2.3. CAGM-Seg

2.3.1. Model Architecture

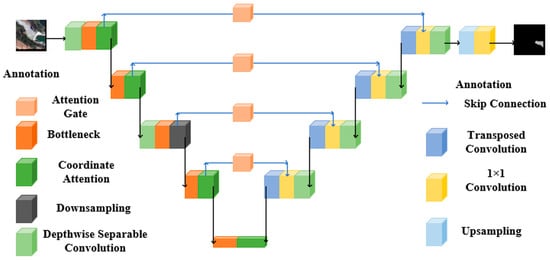

For the task of recognizing small targets in few-shot remote sensing imagery, this paper proposes CAGM-Seg—a lightweight model based on the symmetric architecture of U-Net, with its overall structure depicted in Figure 2. The model adopts a typical symmetric encoder–decoder design: the encoder performs feature extraction, while the decoder is responsible for detail reconstruction; multi-level feature fusion is achieved through symmetric skip connections. This architectural symmetry enables the systematic integration of high-level semantic information with low-level spatial details.

Figure 2.

Architectural Overview of CAGM-Seg.

In the encoder, we employ a pre-trained MobileNetV3-Large as the backbone network, replacing its original attention mechanism with a Coordinate Attention (CA) module. This modification substantially improves the localization of small geospatial targets and their boundary structures. The decoder incorporates an Attention Gate (AG) module, which, via symmetric skip connections with corresponding encoder layers, performs salient information filtering and multi-scale context fusion, thereby establishing an adaptive feature transmission pathway. Furthermore, the decoder makes extensive use of depthwise separable convolutions, maintaining high-quality feature reconstruction capability while significantly reducing both the number of parameters and computational complexity.

This symmetric architectural design not only ensures model stability when processing multi-scale targets, but also achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency through its carefully designed components.

2.3.2. MobileNetV3-Large

To address the challenges of data scarcity and model lightweighting in few-shot remote sensing image recognition, this study employs a pre-trained MobileNetV3-Large feature extraction layer from the ImageNet dataset as the encoder. This approach leverages its learned general visual representation capabilities [43,44], significantly reducing dependency on labeled remote sensing data. The encoder extensively utilizes depthwise separable convolutions and bottleneck structures, achieving an optimal balance between feature extraction capability and model complexity [45,46].

Specifically, depthwise separable convolutions decompose standard convolution into two computationally efficient independent steps: First, in the depthwise convolution stage, each input channel employs an independent 2D convolution kernel to extract spatial contextual information (e.g., edges and textures), as formulated in Equation (2) [46]. Subsequently, during the pointwise convolution (1 × 1 convolution) stage, the feature maps output from depthwise convolution undergo linear transformation and fusion along the channel dimension to produce the final feature map with the target number of channels. This design is particularly suitable for resource-constrained remote sensing image recognition scenarios, enabling more efficient model training and generalization under few-shot conditions [47,48]. The detailed computation is presented in Equation (3).

where denotes the -th channel of the input feature map, is the convolution kernel applied to the -th channel, and is the output feature map’s -th channel. denotes the spatial coordinates on the output feature map, and represent the offsets within the convolution kernel.

This “spatial-first, channel-second” decomposition strategy enables depthwise separable convolutions to significantly reduce both parameter count and computational complexity while maintaining representational capacity [48]. During fine-tuning, we freeze all encoder weights and optimize only the parameters in subsequently modified modules. This approach effectively controls model capacity, mitigates overfitting, and substantially reduces trainable parameters, significantly accelerating convergence. Furthermore, this design encourages the model to adapt general visual features to the remote sensing domain [48], thereby enhancing recognition performance and generalization under small-sample conditions.

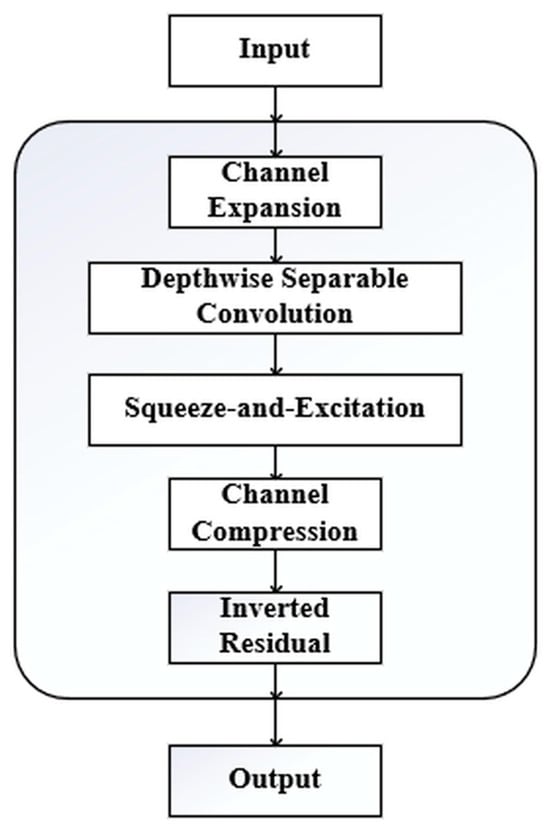

The Bottleneck module in MobileNetV3-Large serves as the fundamental building block for computational efficiency, following an “expand-process-contract” design principle [46]. The module first projects low-dimensional features into a higher-dimensional space via 1 × 1 convolutions to enhance representational capacity. It then applies depthwise separable convolutions for efficient spatial feature extraction [45], followed by a lightweight Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention mechanism that adaptively recalibrates channel-wise feature responses [48]. As illustrated in Figure 3, this integrated design offers particular advantages for remote sensing analysis: the efficiency of separable convolutions facilitates deployment in resource-constrained environments [43]; the SE attention mechanism enhances perception of small objects through adaptive feature calibration [46]; and the inverted residual structure preserves gradient flow through skip connections while maintaining rich low-level features, improving generalization in few-shot scenarios [48].

Figure 3.

Architectural Overview of Bottleneck.

During the channel compression phase, 1 × 1 convolutional layers reduce feature channels back to their original dimensionality. This reduction not only alleviates subsequent computational burden but also selectively preserves the most discriminative features while eliminating redundancy. The inverted residual structure then fuses the processed features with the original input through element-wise addition, as formalized in Equation (4) [48]:

where X denotes the input feature map to the Bottleneck module, F(X) represents the transformed features, and Y is the final output. This residual connection effectively mitigates gradient vanishing in deep networks, promotes cross-layer feature propagation, and enhances feature reuse efficiency [49]. It is important to note that the identity mapping is activated only when input and output channels match, ensuring perfect spatial and dimensional alignment for seamless element-wise addition.

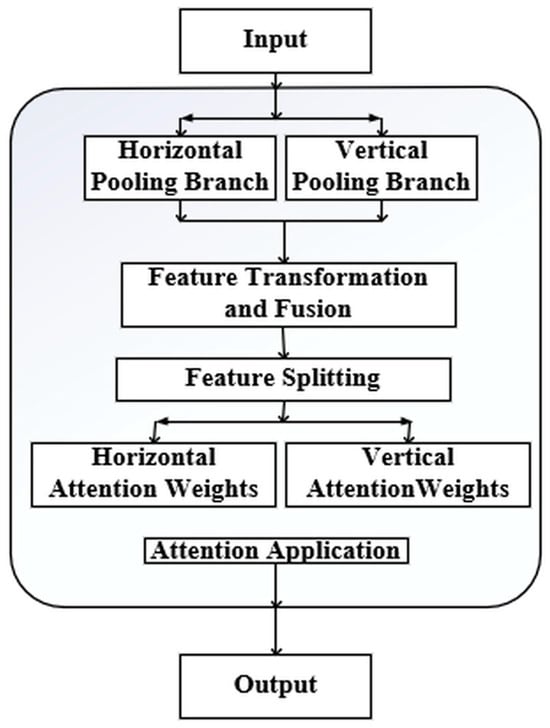

2.3.3. Coordinate Attention

Remote sensing images present significant challenges for small target interpretation due to limited pixel coverage and subtle visual characteristics [50]. To enhance global spatial awareness and improve recognition accuracy for small-scale targets, we introduce two key modifications to the MobileNetV3 architecture: replacing the original Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module with Coordinate Attention (CA), and embedding CA modules after each encoder layer’s bottleneck structure. As shown in Figure 4, the CA module enables the model to determine both feature importance and precise spatial locations of significant features, substantially improving small object recognition in remote sensing imagery [51,52].

Figure 4.

Architectural Overview of CA.

The CA mechanism operates through two sequential stages. The first stage embeds coordinate information through direction-aware encoding that replaces global pooling operations. This approach preserves positional sensitivity by performing symmetric decomposition along horizontal and vertical axes, maintaining equal priority in both directions while avoiding the positional information loss inherent in SE’s global average pooling [53]. This symmetric treatment enables the capture of long-range dependencies with precise positional awareness along orthogonal directions, particularly beneficial for detecting targets with directional characteristics like rivers and linear features. The operation aggregates feature along specific rows and columns while preserving directional positional information, as formalized in Equations (5) and (6).

where denotes the -th channel of the input feature map, and represent the height and width of the feature map, respectively, denotes the width-direction feature of the -th channel at height , and denotes the height-direction feature of the -th channel at width .

In the second stage, coordinate attention is generated through a structured process. The feature maps from both directional encodings are first concatenated, followed by cross-channel information fusion using a shared 1 × 1 convolution and nonlinear activation [54,55]. The combined feature map is then split along the spatial dimension into two separate tensors for height and width directions. Each tensor undergoes Sigmoid normalization to produce directional attention weights in the range (0, 1). The input feature map is then recalibrated through element-wise multiplication with both sets of attention weights, as specified in Equation (7) [55].

where denotes the attention weight in the height direction, represents the attention weight in the width direction, indicates the value of the output feature map at position .

2.3.4. Decoder

To address the dual requirements of model lightweighting and small object detection in remote sensing image recognition, we systematically redesign the decoder based on the U-Net architecture. Traditional decoders often face challenges in balancing computational efficiency with detailed feature recovery, particularly for small objects with complex textures [56,57]. Our solution replaces all standard convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions, creating an efficient multi-layer decoder block cascade.

Each decoder block sequentially executes upsampling, feature fusion, and refinement: transposed convolution first performs 2× upsampling to reconstruct coarse spatial structures; bilinear interpolation then achieves precise size alignment before concatenation with attention-weighted features from the encoder path—a design particularly effective for preserving edges and texture details of small objects; 1 × 1 convolutions subsequently unify channel dimensions; finally, two consecutive depthwise separable convolutions apply nonlinear transformations to enhance the fused features, substantially reducing parameters while maintaining representational capacity [57].

This decoding path progressively reconstructs high-resolution recognition results from low-resolution semantic features through iterative application of the decoder block. The final output is upsampled to match the original input resolution, then processed through a 1 × 1 convolution and Softmax activation to generate pixel-level classifications [58,59]. This optimized design significantly improves small object recognition accuracy and boundary localization while maintaining strict computational efficiency [58,59].

2.3.5. Attention Gate

To meet the specific demands of small object recognition in remote sensing imagery—particularly the preservation of critical details and reconstruction of object boundaries—we substantially enhance the skip connection architecture in the classical U-Net. Conventional skip connections utilize simple feature concatenation, directly transmitting [58,59] multi-scale spatial details from the encoder to the decoder. However, this “hard connection” approach often propagates irrelevant background interference and noise alongside useful information, which becomes particularly problematic when processing remote sensing images with complex backgrounds and small targets, ultimately compromising the reconstruction accuracy of key structures [60].

To overcome these limitations, we introduce an Attention Gate (AG) module to replace direct feature concatenation, transitioning from a “hard connection” to an “adaptive gating” mechanism. The AG module employs high-level semantic features from the decoder as gating signals to assign attention weights to corresponding low-level encoder features. This enables automatic emphasis on small target-relevant regions—such as edge contours and distinctive textures—while suppressing irrelevant background responses during feature fusion [61,62]. Consequently, the decoder achieves precise target contour reconstruction and detailed feature extraction even in complex imaging environments [61]. This design introduces only a minimal parameter overhead. The detailed computational workflow is formalized in Equations (8)–(10).

Here, denotes the feature map from the -th encoder layer, containing rich spatial details (e.g., edges, textures) but semantically simpler information. represents the corresponding gating signal from the decoder, carrying higher-level semantics and enhanced target recognition capability. and denote 1 × 1 convolutional operations applied to and , respectively. represents the fused intermediate feature, which is then processed by a ReLU activation followed by another 1 × 1 convolution, that reduces channel depth to 1, producing a single-channel feature map. The Sigmoid activation σ normalizes values to the range (0, 1), generating the final attention weight map , where values closer to 1 indicate greater importance. ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication, and represents the final AG-weighted feature map—an enhanced version where salient regions are amplified while irrelevant background features are suppressed.

2.3.6. Loss Function and Optimizer

To overcome key challenges in remote sensing image recognition—including class imbalance, blurred object boundaries, and difficulties with small-scale feature identification—this study introduces targeted improvements through a hybrid loss function combining Dice Loss and Focal Loss.

Dice Loss directly optimizes the overlap between predictions and ground truth (Dice coefficient), emphasizing regional consistency and completeness while providing inherent robustness to class imbalance [63]. Simultaneously, Focal Loss incorporates adjustable weighting and modulation factors into standard cross-entropy, dynamically reducing the loss contribution from easily classified samples (e.g., large background areas) and focusing training on challenging cases (e.g., blurred edges or small targets) [64].

The combined loss function, formalized in Equation (13), ensures macro-level recognition accuracy while enhancing micro-level detail capture. This dual approach significantly improves the model’s sensitivity to edges and small objects in remote sensing imagery. The respective formulations are provided in Equations (11) and (12).

where represents summation over all pixels in the feature map or batch. denotes the product between the predicted probability and ground truth label at each pixel position, with the sum approximating the intersection area between prediction and ground truth. The term represents the total predicted foreground area, while corresponds to the actual foreground area in ground truth. The smoothing constant prevents division by zero and ensures numerical stability.

The Dice loss component is computed as shown in Equation (11). For Focal Loss, log(pₜ) constitutes the core cross-entropy term, where pₜ denotes the model’s predicted probability for the true class. The focusing parameter γ (γ ≥ 0) controls the weighting between easy and hard samples, while αₜ represents the class balancing weight corresponding to the ground truth category. The complete Focal Loss expression is provided in Equation (12).

The hybrid loss combines these two components through a balancing coefficient λ (λ ∈ [0, 1]). This design enables flexible adjustment of the optimization direction based on task requirements: when λ approaches 1, the model emphasizes overall segmentation consistency; when λ approaches 0, it focuses more on detailed feature learning from hard examples. By tuning the value of λ, the relative weighting between Dice Loss and Focal Loss during training can be effectively controlled, achieving the dual objective of maintaining macroscopic segmentation accuracy while capturing microscopic details.

To assess the impact of key hyperparameters on model performance, we conducted a systematic sensitivity analysis. Experimental results indicate that CAGM-Seg maintains strong stability across reasonable parameter ranges. Specifically, the model achieves optimal performance when the balancing coefficient λ ranges between 0.4–0.6, effectively coordinating the contributions of Dice and Focal losses. Performance degrades when λ falls below 0.3, with noticeable deterioration in boundary feature identification, or exceeds 0.7, leading to reduced recall in small target detection. For the focusing parameter γ, optimal hard example mining occurs at γ = 2.0. Values below 1.0 impair the model’s ability to distinguish between easy and hard samples, while values above 3.0 cause training instability. Given that black and odorous water bodies typically occupy minimal image area, setting the class weight α to 0.75 effectively mitigates foreground-background imbalance. Notably, ±20% fluctuations in these hyperparameters only cause 0.5–1.2% variation in mean average precision (mAP), demonstrating the model’s low parameter sensitivity and excellent robustness.

Regarding optimizer selection, we employ AdamW to address common challenges in remote sensing recognition, including complex data distributions, overfitting, and training instability. Through decoupled weight decay, AdamW effectively controls model complexity while suppressing overfitting. Training utilizes a small initial learning rate to maintain optimization stability, complemented by weight decay regularization to enhance generalization in complex remote sensing scenarios. The synergistic design of our hybrid loss function and AdamW optimizer ensures efficient and stable convergence, ultimately achieving superior recognition performance [65].

2.4. Model Performance and Reliability Evaluation

2.4.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

To ensure comprehensive and objective evaluation of model performance, we established a multidimensional evaluation framework following standard deep learning practices. The framework integrates multiple complementary metrics: Precision, Recall, Intersection over Union (IoU), Accuracy, Kappa Coefficient, F1-Score, and Boundary F1 Score, ref. [66] with their respective calculations provided in Equations (14)–(21). Model complexity is assessed through total parameter count, trainable parameters, and FLOPs (Floating Point Operations) [67], collectively providing systematic assessment across accuracy, consistency, and efficiency dimensions.

Among these, TP denotes the number of samples correctly predicted as positive by the model; FP denotes the number of samples that are actually negative but incorrectly predicted as positive; FN denotes the number of samples that are actually positive but missed by the model; TN denotes the number of samples correctly predicted as negative. n represents the total number of samples participating in the evaluation; denotes the model’s prediction accuracy rate; denotes the actual accuracy rate; Precision is the proportion of true positives among all samples predicted as positive; Recall is the proportion of all true positive samples successfully predicted by the model. To balance precision and recall, the F1-score is introduced as their harmonic mean, providing a single metric that comprehensively evaluates both false positives and false negatives; Accuracy represents the total proportion of correct predictions among all model predictions, though its reference value diminishes when data distribution is imbalanced; loU measures the degree of overlap between predicted regions and actual regions; Kappa indicates the consistency between model predictions and actual labels; model parameters represent the model’s complexity and capacity; while trainable parameters directly determine computational load and resource consumption during training.

Among these metrics: TP (True Positives) represents correctly identified positive samples; FP (False Positives) indicates negative samples mistakenly classified as positive; FN (False Negatives) refers to positive samples the model failed to detect; and TN (True Negatives) denotes correctly classified negative samples. The variable n represents the total sample size in the evaluation.

In Kappa coefficient calculation, Pₒ represents observed accuracy (overall accuracy), while Pₑ denotes expected agreement by chance. Precision measures the proportion of true positives among all predicted positives, while Recall (Sensitivity) quantifies the model’s ability to identify all actual positive samples. The F1-score, as their harmonic mean, balances both precision and recall, providing a unified measure that accounts for both false positives and false negatives.

While Accuracy reflects the overall correctness of predictions, its reliability decreases under class imbalance. IoU (Intersection over Union) evaluates spatial overlap between predicted and ground truth regions. The Kappa coefficient assesses agreement between predictions and ground truth beyond chance. Total parameters indicate model capacity and complexity, whereas trainable parameters directly determine computational requirements during training. FLOPs serve as a metric for computational efficiency.

In terms of experimental design, this study employed a strict geospatially disjoint principle to partition the three datasets. Specifically, the BOWD (850 samples) was divided into 680 training samples and 170 validation samples in an 8:2 ratio; the LSDB dataset (1500 samples) was split into 1200 training samples and 300 validation samples; and the HRC_WHU dataset (5000 samples) was partitioned into 4000 training samples and 1000 validation samples. This partitioning scheme ensures complete isolation of image patches originating from the same geographic region, effectively preventing data leakage due to spatial autocorrelation.

To ensure balanced data distribution, we analyzed the positive sample (target category) pixel ratios in each dataset. The results show that in the BOWD, the black and odorous water body pixel ratios were 10.92% in the training set and 11.04% in the validation set; in the LSDB dataset, the landslide pixel ratios were 11.31% and 11.51%, respectively; and in the HRC_WHU dataset, the cloud pixel ratios were 42.28% and 42.57%, respectively. The positive sample ratios between the training and validation sets of each dataset are closely aligned, ensuring fairness in model evaluation.

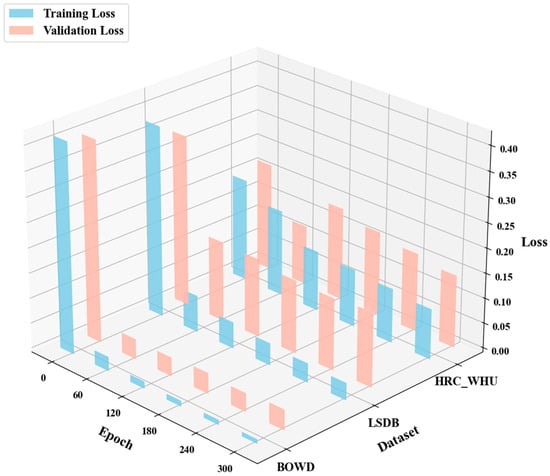

During training, we recorded the trends of the loss function and key performance metrics (such as mAP and IoU) to validate model stability. Experimental results indicate that all three datasets exhibited good convergence characteristics: the training and validation losses decreased synchronously, stabilized after 250 epochs, and the final difference between them was less than 0.05. The performance metrics on the validation set also showed a stable upward trend and convergence. Particularly on the BOWD with the smallest sample size, the validation loss remained stable in the later stages of training without rebound, indicating that the model maintains good generalization capability under limited data conditions, with no signs of obvious overfitting.

Experiments were conducted on a Dell G15 gaming laptop equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 Ti graphics card (8 GB GDDR6 VRAM), an Intel Core i7-12700H processor, 32 GB of DDR5 RAM, and a 512 GB NVMe SSD. At the end of each training epoch, the loss function values and multiple performance metrics were recorded synchronously to ensure complete traceability of the training process and reproducibility of the results. Model performance was evaluated by systematically comparing the predictions on the validation set with the ground truth annotations, and a comprehensive analysis and comparison of the performance of different models was conducted based on the validation set metrics.

Regarding the training strategy, the AdamW optimizer was used with a fixed learning rate of 1 × 10−4 and a weight decay rate of 1 × 10−4, without employing dynamic learning rate scheduling. The weights of the pre-trained MobileNetV3-Large encoder remained frozen throughout the entire training process, and only the parameters of the subsequently added modules were optimized, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters. The loss function used an equally weighted combination (λ = 0.5) of Dice Loss and Focal Loss, achieving complementary advantages of the two losses through direct weighted summation.

2.4.2. Comparative Experiments

In the comparative analysis phase, we uniformly trained and evaluated five models on the BOWD: CAGM-Seg, PIDNet [68], SegFormer [69], Mask2Former [70], and SegNeXt [71]. All models were trained under identical experimental conditions, and their segmentation results were quantitatively compared against ground truth annotations. Performance metrics were computed on the validation set, followed by a comprehensive comparative analysis of the five models to identify CAGM-Seg’s specific advantages and limitations relative to mainstream lightweight architectures.

2.4.3. Ablation Studies

In the ablation study, we evaluated the contributions of individual architectural components by comparing CAGM-Seg against two variants and the baseline U-Net model [72]. The variants include CM-Seg, which removes the Attention Gate (AG) module and replaces depthwise separable convolutions with standard convolutions in the decoder, and CAM-Seg, which only substitutes the depthwise separable convolutions with standard convolutions. All models were trained and tested on the BOWD under identical experimental settings. Through systematic comparison of evaluation metrics and segmentation results, we quantitatively analyzed the performance of each variant, thereby clarifying the specific contributions of both the AG module and depthwise separable convolutions to the overall model performance.

2.4.4. Generalization Capability Testing

This study conducts a systematic evaluation of CAGM-Seg’s generalization capability and reliability across three representative remote sensing scenarios: black and odorous water body identification in Xingtai City, Hebei Province; landslide detection in Bijie City, Guizhou Province; and global-scale cloud recognition. The experiments employ three corresponding datasets—BOWD, LSDB, and HRC_WHU—for training and testing CAGM-Seg under consistent experimental protocols.

For each task, model predictions were quantitatively compared against ground truth annotations, with evaluation metrics computed on the validation set. By analyzing performance patterns across different tasks, we systematically assessed CAGM-Seg’s generalization capabilities and identified its limitations in multi-scenario applications.

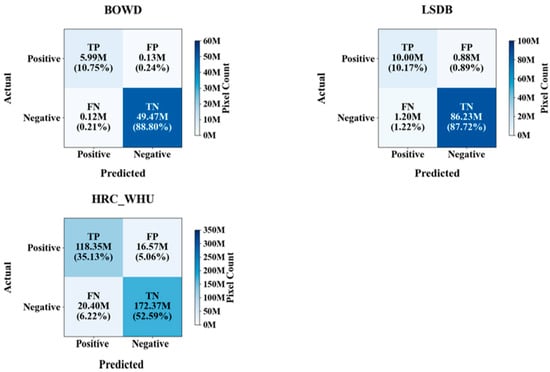

2.4.5. Confusion Matrix Analysis

Building upon the generalization test results, we further employ confusion matrix analysis to examine the model’s prediction characteristics at pixel level. This analytical process involves: (1) categorizing all predictions into True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN); (2) quantifying the frequency and proportion of each category; (3) systematically comparing the distribution patterns across different datasets. This methodology provides detailed insights into CAGM-Seg’s adaptability and primary constraints in handling diverse recognition scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Experimental Results

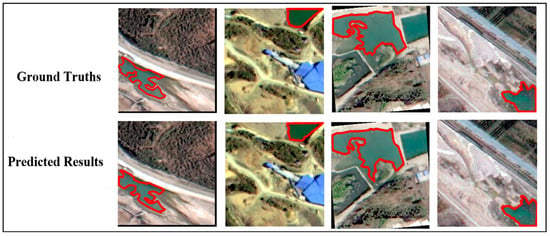

In the task of black and odorous water body recognition under small-sample conditions, we conducted a systematic evaluation of multiple advanced models using the BOWD, with particular emphasis on small target identification. As summarized in Table 5, our proposed CAGM-Seg achieved optimal performance across all evaluation metrics, obtaining 97.85% precision, 98.08% recall, 96.01% IoU, 99.55% accuracy, 97.71% Kappa coefficient, and 97.76% F1-score. Visual results in Figure 5 further confirm CAGM-Seg’s excellence in boundary delineation and fine detail preservation.

Table 5.

Comparative Recognition Performance of Different Models on the BOWD.

Figure 5.

Recognition Results of CAGM-Seg.

CAGM-Seg demonstrates exceptional computational efficiency with an average latency of 17.6 ms per image (≈57 FPS), making it suitable for real-time applications. During inference, GPU memory utilization remains stable at 45–55%, achieving an optimal balance between resource utilization and operational stability. The model maintains these performance advantages while exhibiting remarkable lightweight characteristics, with only 3.489 million total parameters (517,000 trainable) and 0.69 Giga FLOPs computational cost.

When compared with benchmark models, CAGM-Seg’s architectural advantages become particularly evident. PIDNet, while demonstrating faster inference (13.5 ms, 67 FPS) and lower GPU utilization (30–40%) owing to its compact parameter size (1.205 M), shows significantly weaker performance in both IoU (87.46% vs. 96.01%) and F1-score (93.31% vs. 97.76%). SegFormer achieves balanced metrics (94.54% precision, 95.79% recall) with moderate efficiency (18.4 ms, 59 FPS, 40–50% GPU utilization); however, McNemar test results (χ2 = 141,904.5, p < 0.0001) confirm that CAGM-Seg’s performance superiority is statistically significant.

The performance of larger-scale models further underscores CAGM-Seg’s efficiency advantages. Mask2Former, despite its substantial parameter count (73.512 M) and computational load (40.24 GFLOPs), not only delivers inferior performance but also incurs significantly higher latency (179 ms, 4 FPS) and GPU utilization (75–90%). Similarly, SegNeXt (4.308 M parameters, 9.14 GFLOPs) exhibits notably low recall (88.38%) and IoU (84.77%), despite its moderate computational demands (24.6 ms, 39 FPS, 50–65% GPU utilization).

This comprehensive comparison validates that CAGM-Seg successfully strikes a balance between model lightweighting and recognition accuracy. Our architecture not only enables precise identification of black and odorous water bodies in few-shot settings but also ensures practical deployment feasibility through its optimized design—offering a reliable technical solution for remote sensing monitoring in resource-constrained environments.

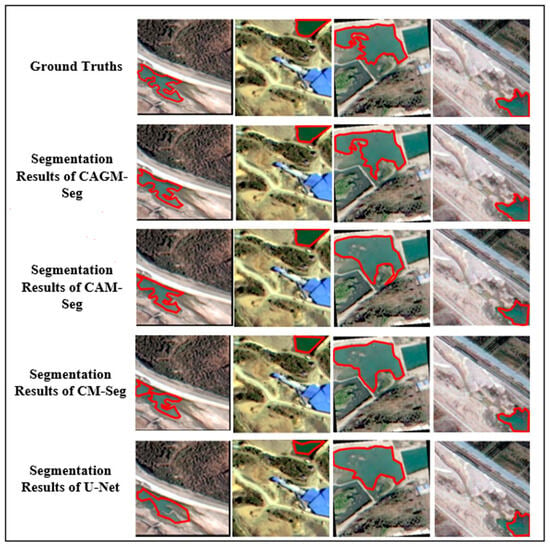

3.2. Ablation Experiment Results

Through systematic ablation studies, we evaluated the individual contributions of key components in CAGM-Seg’s architecture. All models were trained under identical conditions using a hybrid Dice-Focal loss with AdamW optimizer, effectively addressing class imbalance while ensuring fast convergence. Visual comparisons in Figure 6 clearly demonstrate CAGM-Seg’s superiority in target completeness, boundary precision, and detail preservation.

Figure 6.

Comparative Recognition Results of CAGM-Seg and Its Variants.

The progressive architectural refinement is evident in both performance metrics and computational characteristics. As shown in Table 6, CM-Seg, incorporating the pre-trained MobileNetV3-Large encoder and coordinate attention module, achieves substantial improvements over U-Net with 93.77% precision, 95.13% recall, 89.48% IoU, and 81.34% boundary F1-score, while maintaining efficient performance at 18–22 ms (51 FPS) with 48–58% GPU memory utilization.

Table 6.

Ablation Study: Effectiveness Analysis of CAGM-Seg Modules.

Building on this foundation, the CAM-Seg variant further refines feature selection by incorporating an attention gate module, achieving an F1-score of 95.35%, IoU of 91.11%, and a boundary F1-score of 85.77%. These improvements are attained with only minimal computational overhead, maintaining a processing time of 18–22 ms (54 FPS) and GPU memory utilization between 50% and 60%.

The complete CAGM-Seg architecture, enhanced with depthwise separable convolutions, delivers superior performance across all key metrics: 97.85% precision, 98.08% recall, 96.01% IoU, 97.76% F1-score, and 89.30% boundary F1-score. Remarkably, it achieves this with a computational cost of only 0.69 GFLOPs—equivalent to just 3.0% of the baseline U-Net’s parameter count—while operating within 80–150 ms (11 FPS) and 70–85% GPU utilization.

This systematic evaluation confirms that each architectural component contributes significantly to the final performance. Through its carefully calibrated design, CAGM-Seg strikes an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency. The progressive gains observed across model variants validate the effectiveness of our architectural strategy in simultaneously advancing recognition capability and computational economy.

3.3. Generalization Capability Test Results

In the generalization capability assessment, we systematically evaluated CAGM-Seg’s performance across three distinct datasets—BOWD, LSDB, and HRC_WHU—comparing it against established models including SegFormer, Mask2Former, and PIDNet. Quantitative results in Table 7 demonstrate CAGM-Seg’s robust adaptability to datasets of varying scales and characteristics.

Table 7.

Generalization Ability Test Results.

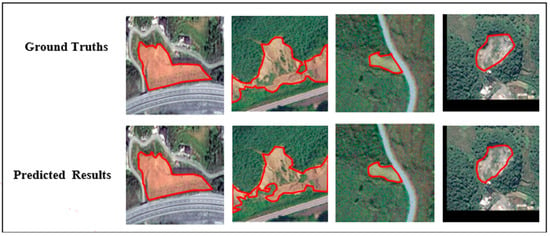

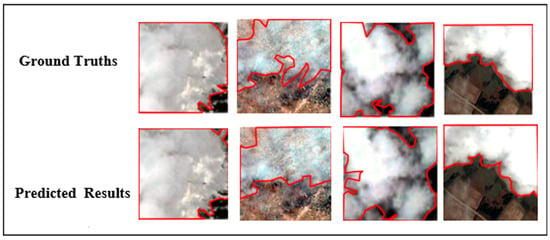

On the globally diverse HRC_WHU dataset, which comprises multi-resolution imagery ranging from 0.5 to 15 m, CAGM-Seg achieved a precision of 87.72%, recall of 85.30%, and an F1-score of 86.48%. These results indicate that it outperforms the compared models in both precision and F1-score, while maintaining competitive recall. The model demonstrated even more pronounced advantages on the LSDB dataset, where it attained 91.93% precision and 90.57% F1-score—significantly surpassing SegFormer (79.41%, 80.01%), Mask2Former (77.35%, 77.12%), and PIDNet (77.90%, 77.45%).

Visual results presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8 further substantiate CAGM-Seg’s capabilities. On the small-scale BOWD (850 samples), the model delivered exceptional performance, with 97.85% precision, 98.08% recall, 97.76% F1-score, and 96.01% IoU. It accurately identified target boundaries while preserving complete contours, despite the limited training data. The medium-scale LSDB dataset (1500 samples) further confirmed the model’s robustness, as it maintained high precision (91.93%) and F1-score (90.57%) while effectively controlling false positives across varied target distributions.

Figure 7.

Recognition Results of CAGM-Seg on the LSDB.

Figure 8.

Recognition Results of CAGM-Seg on the HRC_WHU.

Notably, CAGM-Seg maintains its lightweight advantage with only 3.489 million parameters while exhibiting a graceful performance degradation pattern: as dataset scale and complexity increase from BOWD to HRC_WHU, performance declines gradually without abrupt deterioration. This controlled degradation profile, combined with consistent performance across resolution variations and scene complexities, confirms the model’s strong generalization capability and practical viability for resource-constrained environments requiring multi-scale small target recognition.

3.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis Results

Based on the comprehensive confusion matrix analysis in Figure 9, CAGM-Seg exhibits strong multidimensional recognition capabilities across three remote sensing datasets with varying scene characteristics and spatial resolutions. The model achieves its highest true negative (TN) rate of 88.8% on the BOWD (0.8 m resolution, for water body identification), indicating excellent background discrimination in specialized scenarios. This performance remains robust on the LSDB dataset (87.72% TN at 0.8 m resolution, for landslide detection), but declines to 52.59% on the more challenging HRC_WHU dataset, which contains multi-resolution imagery (0.5–15 m) for global cloud identification. The progressive decrease in TN reflects the growing difficulty in distinguishing complex backgrounds as spatial heterogeneity and target density increase.

Figure 9.

Confusion Matrix for CAGM-Seg Recognition Performance.

Analysis of the true positive (TP) rates reveals a contrasting pattern: CAGM-Seg maintains consistent TP rates of 10.75% on BOWD and 10.17% on LSDB, while achieving a substantially higher TP rate of 35.13% on HRC_WHU. This trend suggests that while the model delivers stable detection performance in specialized scenarios, it also successfully identifies significantly more valid targets in large-scale, globally representative cloud imagery.

Error analysis further highlights distinct patterns across the datasets. False negative (FN) rates progress from minimal (0.21% in BOWD, primarily at water boundary transitions) to moderate (1.22% in LSDB, mainly for shadow-obscured landslides) and higher levels (6.22% in HRC_WHU, particularly for thin cirrus clouds and low-resolution cloud edges). Similarly, false positive (FP) rates rise from 0.24% in BOWD (mainly dark building shadows misclassified as water) to 0.89% in LSDB (such as bare slopes and artificial structures resembling landslides) and reach 5.06% in HRC_WHU (including snow-covered areas and bright surfaces misidentified as clouds).

The comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that CAGM-Seg possesses solid foundational generalization capabilities for specialized small-object recognition tasks. However, when deployed in complex global multi-resolution scenarios like HRC_WHU, while maintaining strong target detection performance, the model shows reduced resistance to complex background interference—particularly across diverse land cover types and varying resolutions. Enhancing fine-grained discrimination between spectrally similar features represents a crucial direction for future optimization of lightweight models in remote sensing applications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Analysis of CAGM-Seg’s Generalization and Recognition Capabilities

To systematically investigate CAGM-Seg’s exceptional generalization and recognition capabilities, we analyze its core mechanisms through two complementary dimensions: data construction and model architecture. The multisource heterogeneous datasets establish the knowledge boundaries and generalization potential, while the lightweight network design determines feature extraction efficiency and information utilization. These elements work synergistically to form the foundation of the method’s performance.

In terms of data construction, our multi-source heterogeneous dataset system provides a robust foundation for model generalization. Unlike previous studies that focused on single scenarios—such as Yuan et al. [73] specializing in urban water bodies or Ghorbanzadeh et al. [74] concentrating on landslide identification with limited samples—our integrated approach encompasses BOWD, LSDB, and HRC_WHU datasets spanning urban environments to natural landscapes. These datasets feature varying sample sizes (850–5000) and spatial resolutions (0.5–15 m), creating a comprehensive testing ground for generalization assessment.

A particularly innovative aspect of our data strategy addresses the inherent resolution imbalance in HRC_WHU through systematic resolution balancing. By strategically distributing samples across four resolution tiers (0.5–2 m, 2–5 m, 5–10 m, and 10–15 m) as detailed in Table 8, we ensure balanced multi-scale learning during training. This multi-level, multi-scale data construction effectively overcomes the sample homogeneity and geographical constraints noted in Li et al. [75], establishing a more reliable benchmark for evaluating model robustness in real-world complex scenarios.

Table 8.

HRC_WHU Sample Resolution Distribution Table.

At the architectural level, CAGM-Seg achieves performance breakthroughs through carefully designed lightweight components and multi-level attention mechanisms. Compared to conventional attention approaches, our coordinate attention module performs symmetric decomposition along spatial dimensions, significantly enhancing perception of small object boundaries while maintaining positional sensitivity [76,77]. The attention-gated module reduces parameters by 53% compared to the base model while outperforming simple concatenation strategies through effective filtering of encoder-transmitted spatial details and background interference suppression.

Notably, the depthwise separable convolution decoder maintains high-quality feature reconstruction with only 3.489 million parameters—significantly lower than large-scale recognition networks while demonstrating exceptional computational efficiency. The integrated design of symmetry-aware mechanisms constitutes another cornerstone of CAGM-Seg’s success, where the coordinate attention mechanism’s symmetric encoding along horizontal and vertical directions enables effective capture of directional features and geometric regularities inherent in remote sensing targets.

This comprehensive design approach, combining sophisticated data strategy with innovative architecture, enables CAGM-Seg to achieve breakthrough performance across diverse remote sensing scenarios while maintaining practical deployment efficiency, with the corresponding loss function curves across different datasets shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Loss Function of CAGM-Seg.

Experimental results confirm CAGM-Seg’s exceptional performance across diverse remote sensing tasks. In black and odorous water body identification, our model achieves a 96.01% IoU on the BOWD, substantially exceeding the 89.5% reported by Liu et al. [18] across comparable datasets. For landslide detection, CAGM-Seg attains a 90.57% F1-score on the LSDB dataset, representing a significant improvement over the 86.3% benchmark established by Tang et al. [78] across varied geographical datasets. In the challenging domain of cloud detection, our model achieves 87.72% accuracy on the HRC_WHU dataset, markedly surpassing the 83.1% performance level reported by Zhu et al. [79] across multiple cloud detection datasets.

These cross-dataset comparisons demonstrate CAGM-Seg’s breakthrough capabilities in feature extraction and generalization, attributable to its innovative architectural design. The model maintains consistent performance advantages across disparate data sources, establishing it as an effective solution for few-shot remote sensing image recognition. The stable performance superiority across different dataset types and geographical conditions underscores the robustness of our approach in addressing the fundamental challenges of small-sample learning in remote sensing applications.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite CAGM-Seg’s strong performance across various remote sensing recognition tasks, this study identifies several limitations that warrant further improvement. First, the model shows limited adaptability when processing cross-resolution images with large spatial resolution differences (e.g., from 0.5 m to 15 m), resulting in inconsistent recognition accuracy. Second, despite significant parameter reduction through lightweight design, the model’s real-time inference capability on edge devices still falls short of practical deployment requirements. Third, the model is sensitive to training data quality; its performance becomes unstable when faced with label noise or severe class imbalance. Finally, the current architecture is primarily designed for semantic segmentation and lacks effective integration with related tasks such as object detection and change monitoring, which limits its applicability in integrated remote sensing analysis workflows. To address these issues, future research should focus on the following directions:

- (1)

- Improve the model’s adaptability to data from diverse sensor types and spatial scales, with an emphasis on stabilizing performance across varying resolutions to enhance generalization in diverse global geographical settings.

- (2)

- Systematically investigate model compression and inference acceleration techniques. While maintaining recognition accuracy, further reduce model complexity and computational cost to enable efficient deployment in resource-limited scenarios.

- (3)

- Develop more robust training mechanisms that are less sensitive to label noise and class imbalance, thereby improving model stability and reliability in real-world complex environments.

- (4)

- Advance the model toward a unified multi-task learning framework that supports collaborative processing of semantic segmentation, object detection, and change detection tasks.

5. Conclusions

This study presents CAGM-Seg, a lightweight model developed for small-object recognition in remote sensing imagery. The model’s recognition accuracy is validated through a case study on identifying black and odorous water bodies in Xingtai City, while its generalization capability is systematically evaluated across three global scenarios: cloud detection, landslide identification in Bijie City, and black and odorous water recognition in Xingtai City. The main findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The CAGM-Seg model achieves an excellent balance between recognition accuracy and lightweight design. It significantly outperforms mainstream models such as PIDNet, SegFormer, Mask2Former, and SegNeXt in identifying black and odorous water bodies. Through its carefully designed architecture, the model reduces the number of parameters by approximately 80% compared to the conventional U-Net, successfully fulfilling the dual objectives of high-precision recognition and operational efficiency.

- (2)

- Ablation experiments confirm the effectiveness and necessity of each core module. The study shows that during the evolution from the baseline U-Net to the complete CAGM-Seg model, the CA module significantly enhances positional awareness of small-object boundaries. The attention gate module effectively optimizes multi-level feature fusion, while depthwise separable convolution substantially improves parameter efficiency without sacrificing performance. The synergistic interaction among these modules validates the rationality of the overall architecture and the effectiveness of the technical approach.

- (3)

- With a total of 3,488,961 parameters (including 517,009 trainable parameters), the model exhibits strong cross-task generalization capabilities while having clearly defined applicability boundaries. For landslide detection, it achieved an IoU of 82.77% and an F1-score of 90.57%, demonstrating effective knowledge transfer enabled by its efficient parameterization. However, when applied to global multi-resolution cloud detection across extensive geographical areas, the model showed a reasonable performance decline, indicating that its strengths are more prominent in fixed-resolution, regional-scale recognition tasks.

In summary, the lightweight recognition model developed in this study strikes an effective balance between accuracy and efficiency. It not only provides a practical technical solution for small-object recognition in remote sensing imagery but also offers valuable insights for model development in related fields through its modular design and lightweight strategy. This work contributes to advancing the practical deployment of lightweight models in resource-constrained environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and H.Y. (Haiming Yan); Methodology, S.Z. and H.Z.; Software, H.Y. (Hao Yao); Validation, J.Z. and H.Y. (Haiming Yan); Formal analysis, Y.L. and J.Z.; Investigation, H.Y. (Hao Yao); Data curation, Y.L. and W.F.; Writing—original draft, H.Y. (Hao Yao); Writing—review & editing, J.Z. and H.Y. (Haiming Yan); Supervision, S.Z. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Hebei Province, China (No. 236Z4201G) and Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (G2023403002).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the editors and reviewers for their careful review, constructive suggestion and reminding, which helped improve the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Shijun Zhang and Hanfei Zhao are employees of the Hebei Provincial Ecological and Environmental Publicity Education and Pollution Source Monitoring Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships.

References

- Sivasubramanian, A.; Vr, P.; V, S.; Ravi, V. Transformer based ensemble deep learning approach for remote sensing natural scene classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 3289–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Geng, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhu, D. Enhanced semantic segmentation in remote sensing images with SAR-optical image fusion (IF) and image translation (IT). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Chang, W.; Ren, W.; Hou, S.; Yang, R. MMFNet: A Mamba-Based Multimodal Fusion Network for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. Sensors 2025, 25, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S. HCGNet: A Hybrid Change Detection Network Based on CNN and GNN. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4401412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Sui, Z.; Lin, K. Hqsan: A hybrid quantum self-attention network for remote sensing image scene classification. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, W.; Zheng, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. A vision-language foundation model-based multi-modal retrieval-augmented generation framework for remote sensing lithological recognition. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 225, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, M.; Liu, S. Selective Prototype Aggregation for Remote Sensing Few-Shot Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5644619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perantoni, G.; Bruzzone, L. A Novel Technique for Robust Training of Deep Networks with Multisource Weak Labeled Remote Sensing Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5402915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rußwurm, M.; Wang, S.; Kellenberger, B.; Roscher, R.; Tuia, D. Meta-learning to address diverse Earth observation problems across resolutions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Tian, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, L.; Yuan, C.; Li, F. A grazing pressure mapping method for large-scale, complex surface scenarios: Integrating deep learning and spatio-temporal characteristic of remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 227, 691–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Xin, H.; Wu, J.; Yao, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, H.-S.; Xu, H.; Luan, H.; Xu, D.; Song, Y. ResWLI: A new method to retrieve water levels in coastal zones by integrating optical remote sensing and deep learning. GIScience Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 2524891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Chowdhury, R.S.; Pal, D.; Bose, S.; Banerjee, B.; Chaudhuri, S. Multiscale probability map guided index pooling with attention-based learning for road and building segmentation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 206, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, P.; Zhang, M.; Tang, W.; Yu, X. CMTFNet: CNN and Multiscale Transformer Fusion Network for Remote-Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 2004612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, R.; Qian, S.; Sun, S. Diffractive Neural Network Enabled Spectral Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Yan, L.; Cao, Y.; Geng, G.; Zhou, P.; Meng, Y.; Wang, T. Global–Local Semantic Interaction Network for Salient Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images with Scribble Supervision. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6004305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, M.; Yuan, S.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Dong, R.; Fu, H. Open-set domain adaptation for scene classification using multi-adversarial learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 208, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolan, J.; Yang, H.-I.; Nosarzewski, B.; Couairon, G.; Vo, H.V.; Brandt, J.; Spore, J.; Majumdar, S.; Haziza, D.; Vamaraju, J.; et al. Very high resolution canopy height maps from RGB imagery using self-supervised vision transformer and convolutional decoder trained on aerial lidar. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 300, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ng, A.H.-M.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Du, Z.; Ge, L. Land subsidence modeling and assessment in the West Pearl River Delta from combined InSAR time series, land use and geological data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaula, C.; Kc, S.; Aryal, J. Enhanced multi-level features for very high resolution remote sensing scene classification. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 7071–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.N.; Biljecki, F. InstantCITY: Synthesising morphologically accurate geospatial data for urban form analysis, transfer, and quality control. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 195, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Fan, J.; Miao, Y.; Hwang, K. Deep Learning Model Compression with Rank Reduction in Tensor Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 1315–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, R.; Luo, T. YOGA: Deep object detection in the wild with lightweight feature learning and multiscale attention. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 139, 109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Fan, J. Generalization analysis of deep CNNs under maximum correntropy criterion. Neural Netw. 2024, 174, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, G.; Maayan, O.; Zelazny, T.; Katz, G.; Schapira, M. Verifying the Generalization of Deep Learning to Out-of-Distribution Domains. J. Autom. Reason. 2024, 68, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, J.; Mao, X. EarthMarker: A Visual Prompting Multimodal Large Language Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5604219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, M.; Jin, Y.; Miao, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, Y.; Qin, X.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.; Li, C.; et al. HyperSIGMA: Hyperspectral Intelligence Comprehension Foundation Model. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6427–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, X.; Pan, S.; Bai, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, T.; Gong, F.; Zhang, X. Satellite retrievals of water quality for diverse inland waters from Sentinel-2 images: An example from Zhejiang Province, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Nava, L.; Zhong, H.; Dong, X.; Qi, J.; Catani, F. A globally distributed dataset of coseismic landslide mapping via multi-source high-resolution remote sensing images. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 4817–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybar, C.; Ysuhuaylas, L.; Loja, J.; Gonzales, K.; Herrera, F.; Bautista, L.; Yali, R.; Flores, A.; Diaz, L.; Cuenca, N.; et al. CloudSEN12, a global dataset for semantic understanding of cloud and cloud shadow in Sentinel-2. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L.; Deng, X.; Wang, K. Reconstruct SMAP brightness temperature scanning gaps over Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.; Benekos, G.; Perrou, T.; Parcharidis, I. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Land Deformation as a Factor Contributing to Relative Sea Level Rise in Coastal Urban and Natural Protected Areas Using Multi-Source Earth Observation Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson, B.; Sveinsson, J.R.; Ulfarsson, M.O. Blind Hyperspectral Unmixing Using Autoencoders: A Critical Comparison. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 1340–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Guo, P.; Sun, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Bai, W. Recent Progress on Vegetation Remote Sensing Using Spaceborne GNSS-Reflectometry. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Yu, D.; Shen, C.; Li, W.; Xu, Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides 2020, 17, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, H.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, Y.; You, S.; He, Z. Deep learning based cloud detection for medium and high resolution remote sensing images of different sensors. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 150, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Poon, S.K. A Deep Learning Approach for Repairing Missing Activity Labels in Event Logs for Process Mining. Information 2022, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zeng, Y.; Gu, M.; Yuan, R.; Li, J.; Ge, J. Multi-level video captioning method based on semantic space. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 72113–72130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-H.; Gao, B.-B.; Wang, C. How to Reduce Change Detection to Semantic Segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 138, 109384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Shao, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, B. LiConvFormer: A lightweight fault diagnosis framework using separable multiscale convolution and broadcast self-attention. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Jiang, J.; Bai, J.; Su, Y.; Su, Z.; Liu, H. Frontiers and developments of data augmentation for image: From unlearnable to learnable. Inf. Fusion 2025, 114, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Tang, C.; Su, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Bai, L.; Dong, Y.; Gong, X.; Ouyang, W. Geometry-enhanced pretraining on interatomic potentials. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Xu, H.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, X. FATL: Frozen-feature augmentation transfer learning for few-shot long-tailed sonar image classification. Neurocomputing 2025, 648, 130652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.F.; Salehpour, P.; Farzinvash, L.; Pashazadeh, S. Multi-Class Brain Lesion Classification Using Deep Transfer Learning with MobileNetV3. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155295–155308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X. A CNN Accelerator on FPGA Using Depthwise Separable Convolution. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2018, 65, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Liu, A.; Chen, X.; Xie, C.; Wang, K.; Chen, X. Reducing calibration efforts of SSVEP-BCIs by shallow fine-tuning-based transfer learning. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2025, 19, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.; Pineda, I.; Lim, W.; Morocho-Cayamcela, M.E. Deep Learning Approaches Based on Transformer Architectures for Image Captioning Tasks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 33679–33694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.S.A.; Syed, H. GSAtt-CMNetV3: Pepper Leaf Disease Classification Using Osprey Optimization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 32493–32506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 3349–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Cui, B.; Fang, X.; Guo, B.; Ma, Y.; An, J. Super-Resolution of GF-1 Multispectral Wide Field of View Images via a Very Deep Residual Coordinate Attention Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 5513305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D. A Novel Lightweight Rotating Mechanical Fault Diagnosis Framework with Adaptive Residual Enhancement and Multigroup Coordinate Attention. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3514517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Peng, Y.; Pan, P. CCAFusion: Cross-Modal Coordinate Attention Network for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Z. EFCA-DIH: Edge Features and Coordinate Attention-Based Invertible Network for Deep Image Hiding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 9895–9908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H. A MultiScale Coordinate Attention Feature Fusion Network for Province-Scale Aquatic Vegetation Mapping from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 1752–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punn, N.S.; Agarwal, S. Modality specific U-Net variants for biomedical image segmentation: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5845–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Li, K.; Chen, J.; Yu, W. CM-Unet: A Novel Remote Sensing Image Segmentation Method Based on Improved U-Net. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 56994–57005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; He, S.; Yang, M.; Lu, X.; Yu, Q.; Liu, K.; Yan, H.; Wang, N. CSC-Unet: A Novel Convolutional Sparse Coding Strategy Based Neural Network for Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 35844–35854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touil, A.; Kalti, K.; Conze, P.-H.; Solaiman, B.; Mahjoub, M.A. A New Collaborative Classification Process for Microcalcification Detection Based on Graphs and Knowledge Propagation. J. Digit. Imaging 2022, 35, 1560–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhu, H.; Lian, L.; Wei, K.; Lai, X. Automatic and visualized grading of dental caries using deep learning on panoramic radiographs. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 82, 23709–23734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]