Abstract

In this investigation, two new subfamilies of bi-univalent functions defined on the open unit disk are presented using Liouville–Caputo fractional derivatives. We determine bounds on the initial Maclaurin coefficients and as well as Fekete–Szegö inequality results based on the bonds of and for functions belonging to certain bi-univalent function subfamilies. Additionally, some novel subfamilies are inferred that have not yet been examined within the context of Liouville–Caputo fractional derivatives.

1. Introduction

Let denote the family of holomorphic functions of the form:

Further, the family of all functions in that are univalent in the symmetric domain is denoted by . Therefore, every function has an inverse , defined by

and

where

If both and are univalent in , then a function is in the family (the family of bi-univalent functions in .

For holomorphic functions f and J in . The function f is subordinate to J, if there exists a holomorphic function w in , such that , and Also, if J in , then iff and

Operators have been used since the early development of complex function theory. They may yield new findings, especially those concerning the convexity and starlikeness of specific functions, and they have simplified the application of many established discoveries. New families of analytic functions are typically introduced as a result of operator-based research. In recent years, the use of operators to analyze bi-univalent functions has also become a common approach, as demonstrated by the latest results in refs. [1,2]. Getting Fekete–Szegö (Fekete and Szegö [3]) functional for special families is of particular interest, according to the most recent publication [4].

The investigation of non-integer-order integro-differential operators is known as fractional calculus (FC). This subject was initially brought up by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in a 1695 letter addressed to Guillaume de L’Hospital. When he asked What happens if the order of a derivative is half, W. Leibniz replied that “it will lead to a paradox, from which one day a useful consequence will be drawn” (for more details, see ref. [5]). The literature claims that the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral and derivative play a major role in FC growth [6]. We used earlier concepts and their well-known extensions involving fractional derivatives (FDs) and fractional integrals (FIs). In 1984, Srivastava and Owa [7] introduced the operator , defined by

where .

Definition 1.

Let be defined on a simply connected region of the z-plane containing the origin. The fractional integral (FI) of f of order ρ is defined as follows:

Additionally, the fractional derivatives (FD) of f of order ρ is defined as follows:

where the multiplicity in the expressions and is resolved by imposing that be real for .

Definition 2.

The FD of f of order is defined as follows:

The fractional-order derivative is defined in the sense of Liouville–Caputo [8], and it is assumed that

where and is the initial value of

Additionally, Owa [9] proposed an operator that extends and unifies the Salagean derivative operator [10] and the Libera integral operator [11].

Recently, Salah et al. in ref. [12] examined

Simple calculations yield

where

Note that, and

We express

Studying subfamilies by additional geometric or analytic criteria, such as starlike functions, convex functions, bi-starlike, bi-convex, highly starlike, quasi-convex functions, etc., provides insight into how analytic functions transform the unit disk; it is helpful for readers and researchers because it helps extend classical results such as coefficient bounds or distortion theorems for univalent functions that do not directly apply to bi-univalent ones. It also develops coefficient bounds and subfamilies enable applications in the applied sciences, better estimation, and comprehension of the features of inverse functions.

The investigation of coefficient estimates for functions belonging to specific special families traces back to the early development of univalent function theory. Gronwall’s Area Theorem, which was discovered in 1914 and is used to compute restrictions on the coefficients of the family of meromorphic functions, is a significant finding in the theory of univalent functions. Bieberbach’s well-known conjecture led to the development of numerous techniques in the geometric theory of functions of a complex variable, which was only confirmed in 1984, and his solution of an equivalent problem for the family in 1916. Similar to the families Gronwall and Bieberbach looked at, the first two coefficients of Maclaurin are usually estimated when studying bi-univalent functions.

For each function in given by (1), Lewin [13] proved that . Brannan and Clunie [14] then refined Lewin’s conclusion and postulated that . Netanyahu [15] later proved that . The challenge of estimating Maclaurin coefficient problem for remains an open problem (for more information, see ref. [16]).

The concepts of quantum or fractional calculus are applied to develop new families of holomorphic functions. Consequently, one can investigate various useful results such as the Fekete–Szegö problem, coefficient estimations, and subordination features. This brings up important topics for scholars, such as radius challenges, convolution characteristics, distortion theorems, and closure theorems. These results can also be applied to meromorphic and multivalent functions, which are inspired by recent studies on bi-univalent functions, for example, [17,18], as well as by the methods previously employed (see refs. [19,20]).

The recurrence relation quantifies the traditional telephone numbers, often known as involution numbers

with initial conditions

Heinrich August Rothe connected these numbers over symmetric groups in 1800 and discovered that is the number of involutions in the symmetric group (see, for instance, refs. [21,22]). It is true that the vth involution number is also the number of the Young tableaux on the set since involutions resemble a typical Young tableaux (for more information, see ref. [23]). John Riordan claims that the number of construction patterns in a telephone system with n customers can be found using the above recurrence relation (see ref. [24]). Wlochand Wolowiec-Musial [25] introduced generalized telephone numbers , which are defined for integers and by the following recursion:

with initial conditions and

Bednarz and Wolowiec-Musial [26] have provided an easily accessible generalization of phone numbers by

with initial conditions

Most recently, Deniz [27] derived the exponential generating function for with the domain as follows:

(see Deniz [27] for more information).

We note that is holomorphic in such that and maps onto a starlike region with respect to 1 and symmetric with respect to the real axis.

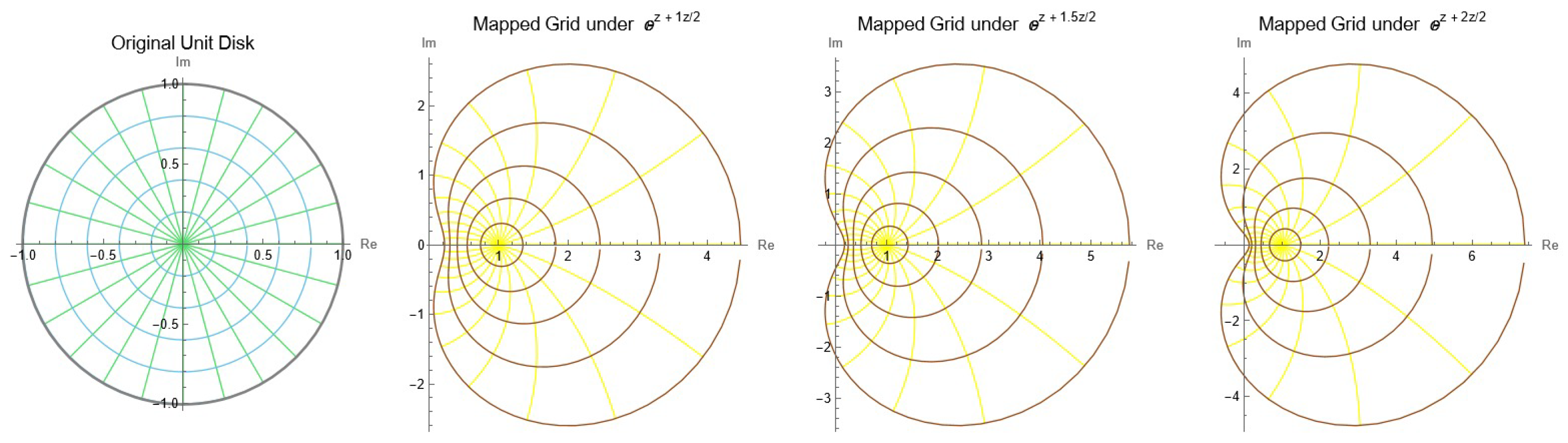

Figure 1 shows the image of the mapping for special choices of parameter ℓ.

Figure 1.

The image of the mapping .

Recently, many scholars have investigated different families of holomorphic and univalent functions by choosing appropriate special functions (see, for example, refs. [28,29,30]). In this work, we employ the function for this purpose.

Lemma 1 ([31]).

Let be a function of the form:

then .

In this work, according to the modified Liouville–Caputo fractional derivative operator , we create two new families and in , then we determine and , as well as the Fekete–Szegö issue for functions in these new families with considering and unless otherwise stated.

2. The Main Results of Function Family

In this section, we will provide the family of holomorphic functions and then estimates for the coefficients , and the Fekete-Szegö functional for functions in this family.

Definition 3.

A function is said to belong to the family provided that it satisfies the following subordination conditions:

and

where and

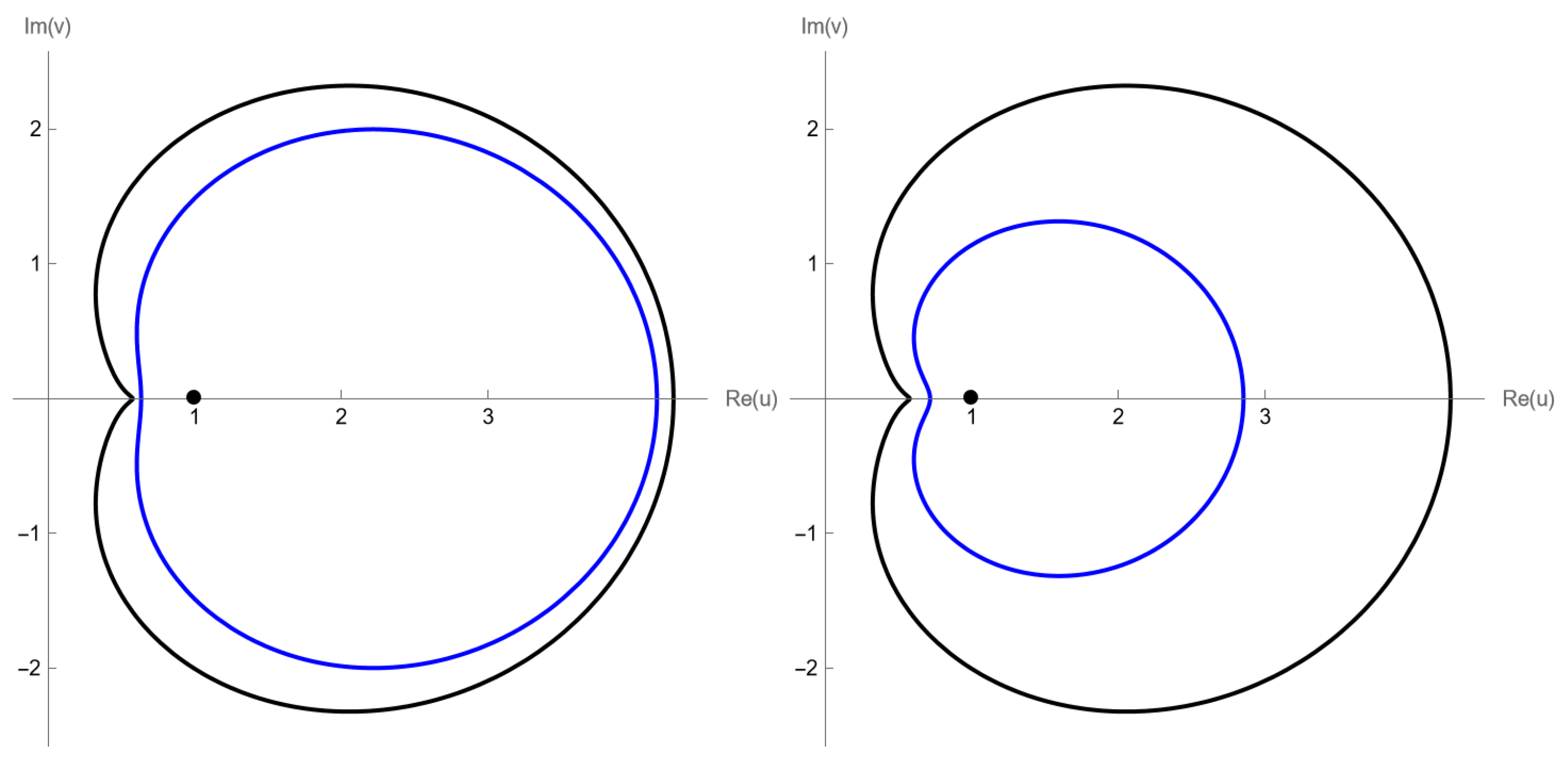

We may compute examples of functions in the aforementioned family using Mathematica, as demonstrated by the following example, which graphically illustrates this inclusion:

Example 1.

The family is not empty; for example, let . Then

and hence

- (1)

- Taking , , , , thenTherefore

- (2)

- Taking , , , , thenTherefore

Figure 2 below illustrate the inclusion observed in the previous example. Readers can also explore numerous special cases by varying the parameter values and performing computations and plots using Mathematica 14.3.

Figure 2.

The inclusion depicted in (1) is represented by the left figure, and the inclusion depicted in (2) is represented by the right figure.

The remaining examples will be special cases that come from the newly introduced family of functions. For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 2.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

where

For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 3.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

where

For and , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 4.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

For and , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 5.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 6 ([32]).

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

where and

Theorem 1.

The bounds in Theorem 1 are not sharp.

Proof.

Let and . Then there are two holomorphic functions with and satisfying the conditions:

and

Define the functions C and B by

and

It is clear that C and B are holomorphic in and . Then the functions are defined such that each of C and B has a positive real part in , and we have

and

From (10) and (11), we get

and

Next, by subtracting (15) from (13) and using (16), we get hence

then by substituting the value of from (17) into (20), we have

Applying Lemma 1, we have

Applying Lemma 1, we have

According to Lemma 1, we get

□

By setting in Theorem 1, we obtain.

Corollary 1.

By setting in Theorem 1, we obtain.

Corollary 2.

By setting in Corollary 1 or in Corollary 2, we get.

Corollary 3.

By setting in Corollary 3, we obtain.

Corollary 4.

By setting in Theorem 1, we obtain.

Corollary 5 ([32]).

3. The Main Results of Function Family

In this section, we will present the family of holomorphic functions and then provide estimates for the coefficients , and the Fekete-Szegö functional for functions in this family.

Definition 4.

A function is said to belong to the family if it meets the following subordinations

and

In accordance with Example 1, we leave it to the reader to use any program at their disposal to locate examples of functions that correspond to the aforementioned family.

We also include a number of examples below that give us notable special instances. For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 7.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 8.

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

For and , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 9 ([33]).

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

For , the family leads to the next subfamily.

Example 10 ([33]).

A function is said to belong to the family if

and

Theorem 2.

The bounds in Theorem 2 are not sharp.

Proof.

Let and . Then there are two holomorphic functions with satisfying the conditions:

and

where given by (8) and given by (9).

From (23) and (24), we get

and

If we subtract (28) from (26) and use (29), we get hence

then by substituting the value of from (30) into (33), we have

Applying Lemma 1, we have

Applying Lemma 1, we have

According to Lemma 1, we get

□

By settig in Theorem 2, we obtain.

Corollary 6.

By setting in Theorem 2, we have.

Corollary 7.

By setting in Corollary 6, we have.

Corollary 8 ([33]).

Corollary 9 ([33]).

Finally, we now offer particular numerical examples for the families and to demonstrate the efficacy and applicability of the theoretical results derived in this study.

Example 11.

Examine the subfamily with and in Theorem 1 or the subfamily with and in Theorem 2. The coefficient estimates yield

and

4. Conclusions

This work has established estimates for the Fekete–Szegő functional and the initial Maclaurin coefficients and for the new bi-univalent function families and , along with their subfamilies detailed in Examples 2–10. The application of a specialized operator to generate these families underscores the novelty of our approach. Looking forward, this research opens avenues for further investigation, particularly the study of second- and third-order Hankel determinants and upper bounds related to the Zalcman conjecture within these families [34].

Ongoing research continues to elucidate the fundamental characteristics of these function classes, motivating the systematic exploration of new families. The consequent refinement of coefficient estimates and the pursuit of original findings remain primary drivers of progress in geometric function theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, B.A.F.; validation T.A.-H.; formal analysis, B.A.F.; investigation I.A.; data curation and resources, T.A.-H. writing—review, B.A.F.; visualization and editing and supervision, I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Srivastava, H.M.; Motamednezhad, A.; Adegan, E.A. Faber polynomial coefficient estimates for bi-univalent functions defined by using differential subordination and a certain fractional derivative operator. Mathematics 2020, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, F.; Al-Hawary, T.; Frasin, B.A.; Alameer, A. Inclusive Subfamilies of Complex Order Generated by Liouville–Caputo-Type Fractional Derivatives and Horadam Polynomials. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Szegö, G. Eine bemerkung uber ungerade schlichte funktionen. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1933, 2, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illafe, M.; Mohd, M.H.; Yousef, F.; Supramaniam, S. A subclass of bi-univalent functions defined by a symmetric q-derivative operator and Gegenbauer polynomials. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2024, 17, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katugampola, U.N. A new approach to generalized fractional derivatives. Bull. Math. Anal. Appl. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, S.G.; Kilbas, A.A.; Marichev, O.I. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives, Theory and Applications; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: Montreux, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, H.M.; Owa, S. An application of the fractional derivative. Math. Jpn. 1984, 29, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Owa, S. Some properties of fractional calculus operators for certain analytic functions. Inst. Math. Anal. Emphasizes Rec. 2009, 1626, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Salagean, G.S. Subclasses of univalent functions. In Complex Analysis—Fifth Romanian-Finnish Seminar: Part 1—Proceedings of the Seminar, Bucharest, Romania, 28 June–3 July 1981; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; Volume 1013, pp. 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Libera, R.J. Some classes of regular univalent functions. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 1969, 16, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, J.; Darus, M. A subclass of uniformly convex functions associated with a fractional calculus operator involving Caputo’s 180 fractional differentiation. Acta Univ. Apulensis 2010, 24, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, M. On a coefficient problem for bi-univalent functions. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 1967, 18, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannan, D.A.; Clunie, J.G. (Eds.) Aspects of Contemporary Complex Analysis. In Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute, (University of Durham), Durham, UK, 1–20 July 1979; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Netanyahu, E. The minimal distance of the image boundary from the origin and the second coefficient of a univalent function in < 1. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1969, 32, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, H.M.; Mishra, A.K.; Gochhayat, P. Certain subclasses of analytic and bi-univalent functions. Appl. Math. Lett. 2010, 23, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanas, A.K.; Pall-Szabo, A.O. Coefficient bounds for new subclasses of analytic and m-fold symmetric bi-univalent functions. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Math. 2021, 66, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoboh, A.; Tayyah, A.S.; Amourah, A.; Al-Maqbali, A.A.; Al Mashraf, K.; Sasa, T. Hankel Determinant Estimates for Bi-Bazilevič-Type Functions Involving q-Fibonacci Numbers. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, F.; Frasin, B.A.; Al-Hawary, T. Fekete–Szegö inequality for analytic and bi-univalent functions subordinate to Chebyshev polynomials. Filomat 2018, 32, 3229–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illafe, M.; Hussen, A.; Mohd, M.H.; Yousef, F. On a subclass of bi-univalent functions affiliated with Bell and Gegenbauer polynomials. Bol. Soc. Parana. Mat. 2025, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowla, S.; Herstein, I.N.; Moore, W.K. On recursions connected with symmetric groups I. Can. J. Math. 1951, 3, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1973; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Beissinger, J.S. Similar constructions for Young tableaux and involutions, and their applications to shiftable tableaux. Discret. Math. 1987, 67, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, J. Introduction to Combinatorial Analysis; Dover: Mineola, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Włoch, A.; Wołowiec-Musiał, M. On generalized telephone number, their interpretations and matrix generators. Util. Math. 2017, 10, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz, U.; Wolowiec-Musial, M. On a new generalization of telephone numbers. Turk. J. Math. 2019, 43, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, E. Sharp coefficient bounds for starlike functions associated with generalized telephone numbers. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2021, 44, 1525–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, W. Extremal problems for a family of functions with positive real part and for some related families. Ann. Pol. Math. 1970, 23, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugusundaramoorthy, G.; Vijaya, K. Certain Subclasses of Analytic Functions Associated with Generalized Telephone Numbers. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupaş, A.A.; Tayyah, A.S.; Sokół, J. Sharp Bounds on Hankel Determinants for Starlike Functions Defined by Symmetry with Respect to Symmetric Domains. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, P.L. Univalent Functions. In Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, Band 259; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Tokyo, Japan, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hawary, T.; Amourah, A.; Almutairi, H.; Frasin, B. Coefficient inequalities and Fekete–Szegö-type problems for family of bi-univalent functions. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotîrla, L.-I.; Wanas, A.K. Coefficient-Related Studies and Fekete–Szegö Type Inequalities for New Classes of Bi-Starlike and Bi-Convex Functions. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ityan, M.; Sabri, M.A.; Hammad, S.; Frasin, S.; Al-Hawary, T.; Yousef, F. Third-Order Hankel Determinant for a Class of Bi-Univalent Functions Associated with Sine Function. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).