Abstract

This paper studies the information interaction process in Bayesian theorem-based swarm systems. Through theoretical analysis, model construction, and simulation experiments, it explores how Bayesian decision-making utilizes information cascades to update its state step by step in group information interaction. The system operates within a theoretical framework where an underlying symmetry governs the dynamic combination of prior knowledge, neighbor information, and target guidance, leading to spontaneous aggregation behavior similar to biological swarms. A key embodiment of this symmetry is the action–reaction force parity between agents, which ensures local stability.The simulation results show that groups with different prior information exhibit a multi-stage convergence characteristic, which reveals that within each iteration step, the agent adheres to the rules for information-symmetric communication and interaction. This dynamic behavior is a true reflection of natural biological populations and provides theoretical support for practical applications such as traffic management and robot collaboration.

1. Introduction

Group information interaction refers to a dynamic process in which multiple individuals or organizations transmit, share, and collaborate through specific channels and mechanisms. This complex system exhibits significantly different characteristics and evolutionary paths at different historical stages. In 1948, Shannon [1] first quantified the mathematical model of information interaction, providing a theoretical foundation for subsequent information interaction. In 1955, Asch [2] demonstrated through the classic line judgment experiment that information interaction is not only a transmission process but also a result of social identification. In 1967, Milgram [3] proved through the letter transmission experiment that group information interaction can span social distances through short paths. In 1998, Watts and Strogatz [4] proposed the small-world network model to explain why group information can both locally cluster and rapidly diffuse globally. In 2018, Rahwan et al. [5] proposed a new framework for studying AI agents participating in group interaction. In 2023, Acerbi and Stubbersfield [6] proved that large language models can simulate human group interaction behavior, providing new tools for studying information flow in human–machine hybrid groups. This evolutionary process not only reflects the transformative power of technological innovation on social interaction but also reveals the key role of information as a core production factor in the operation of modern society. Traditional group information interaction is mostly based on the assumption of complete information transmission, which means that individuals can acquire all information from their neighbors without noise or loss, and then update their own states accordingly. For example, the classic DeGroot model [7] assumes that the group reaches consensus through linear weighted averaging, while the Friedkin and Johnsen model [8] further introduces individual stubbornness, but still relies on deterministic interaction. Subsequent studies, such as the Hegselmann and Krause (HK) model [9] and the Bounded Confidence model [10], relaxed the assumption of complete connectivity, but still implicitly assumed perfect information transmission. In recent years, Bayesian information decision-making has provided a new modeling approach for group information interaction. Its core lies in treating information transmission as a probability updating process, rather than a deterministic state replication. Reference [11] jointly studied the Bayesian decision-making mechanism in animal cluster behavior, revealing how biological groups achieve efficient collective behavior through probabilistic reasoning at the individual level. Reference [12] experimentally demonstrates that human group decision-making spontaneously follows approximate Bayesian inference rules. Real-world networks usually evolve dynamically over time, and Bayesian networks provide a powerful modeling framework for simulating information cascading effects in this evolutionary process [13]. For example, the critical point of opinion polarization in public opinion formation can be explained by Bayesian models. Similarly, Bayesian methods can also be used to estimate reasoning about epidemic prevention behaviors and individual health risk perception. In the field of multi-agent systems, Reference [14] first realized the collaborative localization of drone swarms in a completely GPS-free environment through Bayesian belief propagation using a layered factor graph model. Roumeliotis and Bekey [15] developed a distributed Bayesian estimator to solve the problem of relative pose estimation for robot swarms, making breakthrough progress in the field of distributed group intelligence. Against the background of microscopic particle interactions, the Cranmer team [16] used Bayesian neural networks in the LHC experiment to distinguish the signal of Higgs bosons from background noise, achieving efficient approximate calculation of the likelihood ratio. The Burov [17] developed a Bayesian filtering-based algorithm for reconstructing the trajectory of single particles. Based on the above literature review, Bayes’ Theorem is commonly applied in group decision-making. In group systems, interactions between individuals often depend on their distance and local environment. Such interactions can be described through potential energy functions, which are typically functions of distance and effectively characterize changes in attraction or repulsion. The attractive and repulsive interactions between individuals are essentially a dynamic decision-making process based on local information feedback, which aligns closely with the core idea of Bayes’ Theorem. By combining prior probabilities with observational data to update posterior probabilities, individuals in a group similarly rely on historical experience and current environmental perception to adjust their behavioral strategies. Therefore, this paper provides a detailed analysis of the importance of Bayes’ Theorem in group interactions from the perspective of information exchange. This framework elucidates the mechanisms of individual interactions within swarms and is highly valuable in fields such as traffic management, medical diagnosis, financial risk assessment, prediction of group interactive behaviors, and autonomous exploration of robots. In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) This paper achieves a paradigm shift by applying Bayes’ Theorem to the study of group information exchange processes. Unlike the idealized state in classical theories where information is assumed to be perfectly transmitted within the perception radius, the information acquisition in this paper is based on a decision-making process of Bayesian probability, where both the sender and receiver probabilistically transmit and receive information. It explores how groups reach consensus through Bayesian inference under non-ideal information conditions, which more realistically simulates the decision-making process in biological populations and social systems.

(2) This paper proposes an information interaction model based on Bayesian information cascading, which breaks through the limitations of traditional idealizations and establishes a theoretical framework that better aligns with the complexity of the real world. Firstly, it adopts a probabilistic cascading mechanism to simulate the information dissemination process, treating each individual as an information node for dynamic evaluation based on Bayesian rules. Then, it characterizes real-world constraints by using the dynamic balance between an individual’s safety radius and perception radius. Finally, the system models the non-ideal interaction features. These findings profoundly reveal the unique self-organizing characteristics exhibited by the Bayesian inference process under realistic conditions that consider the incompleteness of information transmission.

Furthermore, this paper delves into the inherent symmetry principles within the model and reveals their critical role in ensuring system stability and convergence. Specifically, we demonstrate that Newton’s third law governing the attractive and repulsive interactions between individuals—that is, the symmetry of action–reaction forces—serves as the cornerstone for maintaining the physical structural stability of the swarm. Simultaneously, the unified application of information update rules and behavioral control protocols across all individuals constitutes symmetry at the behavioral and cognitive levels. The synergy of these multi-level symmetries represents the underlying mechanism through which the swarm emerges as a robust and highly efficient self-organizing system.

2. Preliminary Knowledge

Bayes’ Theorem, as a core theory in probability, fundamentally operates through a “prior-likelihood-posterior” framework to achieve dynamic belief updating. The formula for Bayes’ Theorem is P(A/B) = P(B/A)P(A)/P(B), where P(A) is the prior probability and P(A/B) is posterior probability. This theory provides a mathematical description of individual cognition and, more importantly, lays a theoretical foundation for understanding swarm behavior. Generally, Bayes’ Theorem allows us to quickly abstract complex probabilities and patterns from limited experiences [18], considering it an idealized computational process at the individual level, while neglecting its complex manifestations in group interaction environments. Therefore, when individuals are embedded in social networks, their belief update is influenced by both private information and public behavior, forming a more complex dynamic process. Based on this phenomenon, the pioneering research by Bikhchandani [19] and in [20] reveals a key mechanism: rational individuals may overly rely on public information and neglect private signals, leading to information cascades. This discovery provides important insights for this study, but it also has the limitation of assuming complete and immediate information transmission. Subsequent work by Eyster [21], although expanding the application of social learning scenarios, still does not address this core issue. Hence, this study utilizes information cascades to establish an observable Bayesian decision-making framework, introducing an information transmission efficiency matrix to depict information interaction. Both the sender and receiver of information will interpret information differently based on their own knowledge structures and neighbor states, exhibiting different decision behaviors. Theoretical predictions suggest that groups with higher initial information awareness will demonstrate a strong memory effect, where early information advantages are continuously amplified, driving information to flow towards areas with lower awareness in a gradient diffusion manner, accelerating its spread, and ultimately exhibiting multi-stage convergence characteristics. The significant value of this theoretical framework lies in its incorporation of multiple loss mechanisms in the information interaction process into the Bayesian decision-making model, making predictions of group behavior more aligned with reality.

The key to information cascades lies in the incompleteness of information, meaning individuals cannot directly observe others’ private signals and can only infer them from behavior. This demonstrates that information cascades are an inevitable product of Bayesian rationality, rather than simple irrational imitation. Research shows that the accuracy of group decision-making is extremely sensitive to initial conditions, with random choices by a few individuals in the early stages being amplified through positive feedback effects, ultimately leading the entire system to become locked into suboptimal or even incorrect equilibrium paths. After integrating Bayes’ Theorem, the probability of incorrect cascades can be reduced by 40–50%, endowing cascade dynamics with a richer connotation. Assume a Bayesian information cascade dynamic propagation model, where blue, green, and red colors are used to represent individuals with different prior information within the group. The first type of individual is numbered 1 … A, the second type is numbered 1 … B and the third type is numbered 1 … C. Moreover, during system initialization, each node initializes its learning rate based on its prior distribution and satisfies. Subsequently, the model enters the Bayesian updating phase, where individuals continuously update their learning rate based on their historical states, forming an information cascade. After n iterations of updates, the system emerges with a global consensus phenomenon, where the posterior probabilities of all nodes converge to 1. This process vividly illustrates the dynamic mechanism in Bayesian social learning theory, where agents continuously absorb observational evidence and perform sequential Bayesian inference, ultimately forming an information cascade. The model clearly demonstrates the complete evolutionary path from an initially uncertain prior distribution, through multiple iterations of Bayesian belief propagation and message passing in probability graphical models, to a stable, high-confidence posterior distribution. This fully embodies the progressive consistency of evidence accumulation and belief updating Bayesian inference.

3. Bayes Information Interaction Model Construction

Group aggregation control algorithms are a class of algorithms designed to control the aggregation behavior of multiple individuals or agents in space. Their core purpose is to enable dispersed individuals to autonomously adjust their behavior in complex environments, following established logic, and orderly converge to designated areas or form specific group structures. These algorithms not only simulate biological swarm intelligence to solve large-scale, distributed problems that are difficult to handle with traditional control methods but also effectively respond to complex environments to enhance group action efficiency. Utilizing Bayes’ Theorem to study group aggregation involves multiple influencing factors, such as individual safety radii, perception radii, initial distributions, and attractive or repulsive forces. It is crucial to deeply investigate the relationship between individual properties and group structures.

Based on the aforementioned swarm phenomena, when exploring their underlying principles, we consider a group of particles moving in a two-dimensional Euclidean space with double integrator dynamics, defined as follows:

where represents the position state of the individual i, represents the velocity state of the individual, and here we assume that each individual has equal mass, hence, denotes the range of interaction between two agents.

where denotes the Euclidean norm of . In a swarm, each individual and its neighbors maintain equal distances d, satisfying the condition that the distance between any two neighbors is equal.

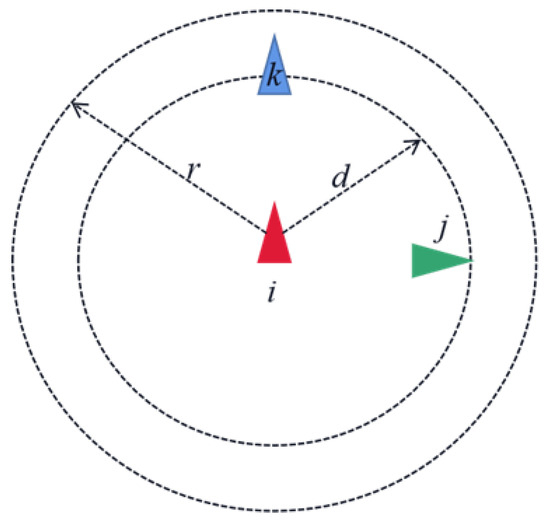

where i = 1, 2, …, N, , represents the perception radius and . Additionally, we model the relationships between agents as shown in the figure, where each agent is represented by a symbol. According to the definitions above, the safety radius of an agent is denoted by r, and the perception radius is denoted by d.

As shown in Figure 1, When the distance between agents is less than d, that is, , agent i exhibits repulsion to avoid collision with agent j. In contrast, when the distance between agents is greater than d, that is, , agents will attract each other to achieve aggregation. Furthermore, when the distance between agents is equal to d, agents i and j remain stable.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Bayesian information cascade.

According to the defined rules, adjacent agents will generate repulsive forces when they are too close and attractive forces when they are too far apart. To describe this phenomenon between agents, we employ a potential energy function, which is defined as follows:

Specifically, the formula for the interaction force is given by:

where and are the repulsion and attraction coefficients, respectively, and x is the actual distance between the two agents.

The design of the interaction force is fundamentally architected to embed dynamic symmetry into the very fabric of agent interactions. This is mathematically mandated by the strict adherence to Newton’s third law, ensuring that the force exerted by agent i on agent j is always equal and opposite to the force exerted by agent j on agent i. Specifically, the formula for the interaction force is given by:

This action–reaction symmetry is not merely a mathematical formality; it is a profound physical principle that confers critical stability properties upon the swarm. As a direct local manifestation of momentum conservation, it guarantees that internal forces sum to zero at the system level. This elegant property is the primary mechanism that actively suppresses the emergence of non-physical net internal forces during collective motion.

The absence of such symmetry would lead to pathological behaviors, such as self-acceleration of the swarm without external input or the buildup of destructive internal oscillations. In contrast, our model, by enforcing this force parity, ensures that all accelerations are solely the result of external guidance or dissipative terms. Consequently, this force symmetry serves as the cornerstone for maintaining coherent spatial structures, allowing the swarm to translate and maneuver as a cohesive whole while efficiently dissipating disruptive energy through its interaction topology. It is, therefore, the indispensable physical foundation upon which robust and stable collective intelligence emerges.

Therefore, based on the three basic rules of swarming [22] (aggregation, collision avoidance, and velocity matching) and Bayes’ Theorem, we have improved the classic Olfati-Saber model [23] using the Bayesian information cascade model [24]. We introduce a Bayesian decision-making mechanism into the control input, so that the motion control of each agent is influenced not only by the spatial interactions with other agents in the physical neighborhood but also by the group decision-making behavior in the information neighborhood. Specifically, the control input of agent i consists of three parts: The first part is the traditional spatial interaction force based on the Olfati-Saber model, including attractive forces for maintaining swarm aggregation, repulsive forces for avoiding collisions, and coordination forces for achieving velocity matching. The second part is the Bayesian decision term, where the agent performs Bayesian updates based on the decision behaviors of neighboring individuals and its own private information, calculates the posterior belief, and adjusts the direction of movement. The third part is a stochastic perturbation term, used to enhance the robustness and exploration capability of swarm behavior. The fourth part is the navigational feedback term, which, through the global guidance of virtual leaders, provides the swarm with a clear objective orientation. This integrated design enables the swarm system to maintain self-organizing characteristics at the physical level while achieving distributed decision-making optimization at the information level. When the majority of agents in the swarm make similar decisions based on high-quality private information, the information cascade effect guides the entire swarm to rapidly converge to the optimal state, while the interaction forces based on distance ensure the stability of the swarm structure during this process. The control input for agent is given by:

where is a gradient-based term; is the velocity consensus term; is the Bayes term; is the Random disturbance term; is the navigational feedback term from the kth virtual leader.

We assume the existence of three groups of multi-agents, each representing a different ideal state. We define a matrix of coefficients i × 4 consisting of random range coefficients for these three groups of heterogeneous agents.

where represents the probability that the first agent in the first group knows the position information of the virtual leader in x-direction, represents the probability that the first agent in the first group knows the position information of the virtual leader in y-direction, represents the probability that the first agent in the first group knows the velocity information of the virtual leader in -direction, and represents the probability that the first agent in the first group knows the velocity information of the virtual leader in -direction. Subsequently, we extract the probabilities of knowing the velocity and position information of the virtual leader in the x and y directions for all three groups and form N × 2 matrices and (where N is the total number of agents). The formula is given by:

where represents the probability that the group knows the position information of the virtual leader in the x and y directions, and represents the probability that the group knows the velocity information of the virtual leader in the and directions.

In the process of modeling and analyzing swarm systems, making full use of available information is crucial for accurately describing and predicting swarm behavior. Therefore, we utilize the initial state weights , of each individual i to construct the prior knowledge for Bayes’ formula, denoted as:

where and is the state difference between each individual and the virtual leader. This prior construction method takes into account the deviation between the individual’s current state and the target state, enabling individuals to have an initial assessment of their own state at the initial stage, providing a foundation for subsequent state updates.

After obtaining prior knowledge, individuals need to integrate information from their neighbors to further optimize their judgments. In this process, weight calculation is a key step. We use the Gaussian kernel weight formula to determine the importance of neighbor information. The formula is given by:

where and represent the position coordinates and velocity vector of neighbor j, respectively, r and represent the position coordinates and velocity vector of the current individual i, and is the bandwidth parameter of the Gaussian kernel.

To ensure parameter optimization and adjustment, and to avoid excessively large or small values after calculation, we normalize the weights so that the sum of the normalized weights is 1. The formula is given by:

where is the set of neighbors of agent i. is an infinitesimally small value to prevent the denominator from being zero, with a size of .

Based on the calculated weights, the system optimizes the state of the agents through a posterior update formula, which is given by:

where represents the updated new position state and represents the updated new velocity state. and represent the position and velocity states at the current time, and represents the learning rate. Through this formula, the agent combines prior knowledge, neighbor information, and target guidance to achieve dynamic updates of its own state, thereby better adapting to environmental changes and completing collaborative tasks.

We must emphasize that the Bayesian update rules presented here define a symmetric interaction paradigm. Although Formulas (18) and (19) only describe how agent i is influenced by its neighbors, the same rules apply equally when neighbor j updates its own state. Specifically, when agent i updates itself based on the state of its neighbor j, agent j simultaneously incorporates the state information of its neighboring agent i into its own belief update using the identical update rules, thereby revising its own state estimation and . Therefore, as shown in Formula (6), the mutual influence between agents i and j is completely symmetric in both mathematical form and algorithmic logic.

Simultaneously, this paradigm further ensures the symmetry of synchronous information exchange, meaning that in each discrete iteration step, the agents participating in the exchange simultaneously execute Bayesian update rules. The direct consequence is that the information fusion and state correction processes experienced by any pair of interacting agents (i and j) are mathematically identical and temporally synchronized. It guarantees the symmetry of bidirectional information flow in each interaction round. Each agent not only updates its state estimate based on its own observations but also simultaneously receives observational information from its interaction partner. Both agents then compute their posterior distributions using identically structured Bayesian update formulas. This bidirectional information exchange model, grounded in unified rules, enables the propagation of local consensus throughout the entire system, thereby promoting coordinated collective behavior at the macro level.

Next, we derive the new position and velocity information rates based on the new position and velocity states, denoted as , . The formula is given by:

where is the vector difference between the agent’s position and the leader’s position, is the vector difference between the agent’s velocity and the leader’s velocity, and is a small constant to avoid division by zero.

In multi-agent simulations, the progression is typically made by iteration steps (Iteration). After a certain number of iteration steps, the formula for the control input becomes:

where is the control input term. Combining the analysis of the above control inputs, we have:

By integrating the Bayesian probability update mechanism with distributed control input design, swarm intelligence systems can achieve collaborative decision-making that adapts to environmental changes, thereby exhibiting greater robustness and flexibility in dynamic and complex scenarios. This fusion method not only enhances the intelligence level of swarm behavior but also enables the system to continuously optimize control strategies based on real-time observational data, ultimately achieving more efficient and stable collaborative motion control.

In the scenario of multi-agent collaborative interaction, the dynamic demonstration mechanism of the virtual leader’s trajectory plays a decisive role in studying swarm information interaction. This mechanism not only serves as an external guidance medium to coordinate information exchange among agents but also precisely regulates swarm behavior patterns by constructing a multi-level information transmission network. Specifically, the virtual leader continuously outputs directional guidance signals and feedback instructions, driving the swarm to form orderly self-organizing motion and ultimately reach the target area. At the level of system control architecture design, the Semi-Flocking [25] algorithm is used to divide the swarm into active interaction groups and passive interaction groups. By controlling the behavior of the virtual leader, the interaction process of groups with different properties and structures is simulated, allowing for a deeper study of the dynamic characteristics of swarm information interaction. The navigational feedback terms for the virtual leader and the virtual leaders of different ideal state groups are given by:

where and represent the position weight and velocity weight, M represents the total number of agents following the virtual leader and N represents the total number of agents following different ideal state virtual leaders . The guidance and control capabilities of the virtual leader over the swarm increase with the enhancement of the navigational feedback. During the aggregation process, continuous feedback causes the agents to move closer to or farther from the virtual leader. Additionally, to avoid collisions between agents, they constantly adjust their positions through attractive and repulsive interactions. Therefore, the gradient consensus term is set as follows:

where is a linear constant, in this paper, and represents the number of interconnected individuals perceived by the ith individual. Furthermore, to achieve swarm consistency, the control of agents also requires a velocity consensus term, which is achieved by matching the velocities of interacting agents. Therefore, the velocity consensus term is as follows:

where is the element of the adjacency matrix . In summary, the control input for the kth virtual leader is given by:

where k represents the number of virtual leaders, represents the total number of agents following the kth virtual leader, represents the position of the virtual leader, and represents the velocity of the kth virtual leader. Therefore, by controlling the position and velocity of the virtual leaders, the movement habits and trajectories of the agents are simulated.

Finally, the entire control architecture embodies a profound symmetry at the behavioral rule level, forming the cornerstone of the system’s self-organizing capability. This symmetry manifests as the universal application of an identical, symmetric control law that governs all individuals within the swarm. Crucially, this unified rule set is applied irrespective of the agents’ initial states, group affiliations, or local information advantages. By ensuring that every agent—whether initially well-informed or poorly informed—processes information, updates beliefs, and executes actions according to the same principled protocol, the system achieves remarkable consistency in collective decision-making. This behavioral symmetry effectively eliminates arbitrary algorithmic biases that could fragment the swarm, thereby guaranteeing that emergent coordination arises genuinely from local interactions rather than from predefined individual roles. Consequently, this rigorous adherence to symmetric rules at the individual level provides the necessary and sufficient conditions for the emergence of predictable, stable, and scalable collective intelligence at the system level, where the macro-level orderly patterns directly reflect the micro-level symmetric rule structures.

4. Simulation Design and Analysis

This section simulates the behavior of a swarm based on the Bayesian information interaction cascade model designed in this paper. In the experiments of this section, using MATLAB R2019b software, some basic parameters of the swarm are set as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main simulation parameters.

The agents are divided into three groups based on their distinct initial information awareness rates. The physical parameters of these groups are completely consistent, as shown in Table 1. Through this controlled design, we can analyze how differences in initial information levels drive the groups to form different convergence patterns, so as to explore the differences in information perception capabilities.The safety radius d establishes the minimum threshold for collision avoidance between agents. The perception radius r defines the neighborhood for information exchange, thereby facilitating the formation of dense and stable swarm structures through collective aggregation. Parameters and serve as feedback weight gains for position and velocity states, respectively, jointly guiding the agent to converge stably and smoothly toward the target state. and are force coefficients of equal magnitude but opposite direction. This embodies a symmetrical design in physical interactions, which helps maintain the local stability of the cluster system. Simulation steps t define the total duration of the iterative process to ensure the system dynamics have sufficient time to fully evolve and reach a steady state. Additionally, the introduction of the learning rate ensures the robustness of the belief update process, effectively preventing unstable oscillations during convergence.

To study the dynamic behavior of swarm interactions based on Bayes’ Theorem, we mark the three groups of agents with triangles and distinguish them with different colors: red for the first group, green for the second group, and blue for the third group. Their initial positions and velocities are randomly and uniformly distributed within the range of (−1, 1) according to a normal distribution. The initial position and velocity of the virtual leader are both (1, 1). Additionally, the perception of interconnectedness between agents is represented by solid blue lines.

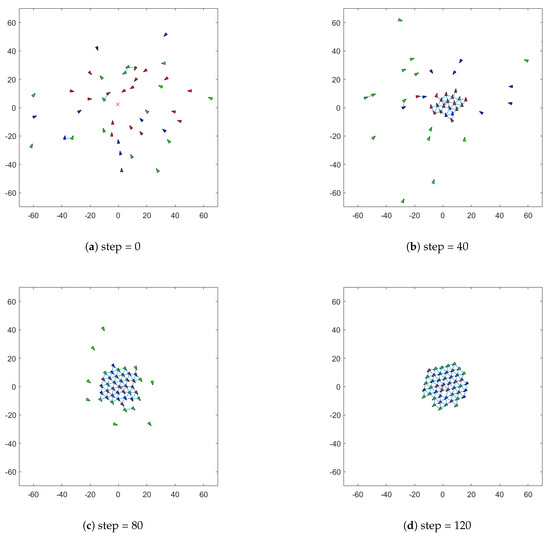

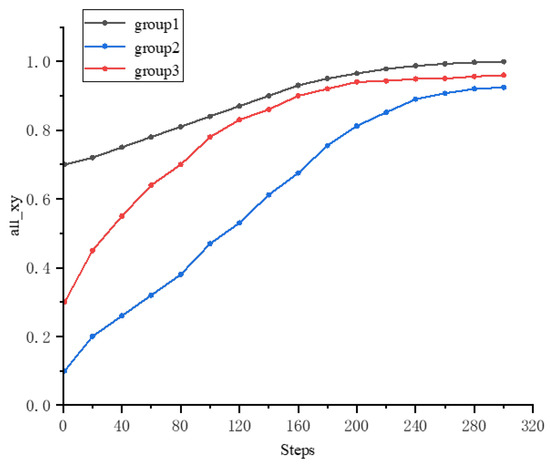

As shown in Figure 2, the red-marked first group of agents 1 = 0.7 exhibits the fastest convergence speed, quickly moving towards the virtual leader’s state in the early stages of iteration. The blue-marked third group of agents 3 = 0.3 begins to show a convergence trend after the red group reaches a preliminary convergence. The green-marked second group of agents 2 = 0.1 demonstrates a significant lag in response. The entire convergence process is characterized by multiple stages: a rapid convergence stage, a gradual diffusion stage, and a final convergence stage. A higher information awareness rate can first form a convergence core and significantly improve the agents’ response efficiency to the global goal, then drive the agents with a medium information awareness rate through swarm interaction. The agents with a lower information awareness rate show a lag in response, and their convergence behavior requires a significantly longer iteration cycle to become apparent. This indicates that the lower limit of the information awareness rate directly affects the time scale for the swarm to reach consensus. The experimental results verify that in distributed swarm intelligence systems, even with significant differences in individual information acquisition, the system can still achieve global consistency through appropriate interaction mechanism design.

Figure 2.

Simulation process of Bayesian information interaction model. (a) Initial state with no apparent clustering structure. In the initial state, the data points are randomly scattered without any clear grouping. (b) Formation of local clusters. As the process continues, the clustering becomes more apparent, with points consolidating into larger, well-defined clusters. (c) Formation of larger and well-separated clusters. By this stage, the clusters have not only grown larger and more compact through consolidation, but the distances between them have also significantly increased, resulting in well-separated groups. (d) Compact and stable clusters. In the final state, the clusters are stable and exhibit high internal density, with points tightly packed within their respective groups. The formation and maintenance of this structure benefits from the symmetry of the forces in the model, which enables the attraction and repulsion between individuals to reach a dynamic balance, thus showing a stable spatial configuration symmetry on the macro level.

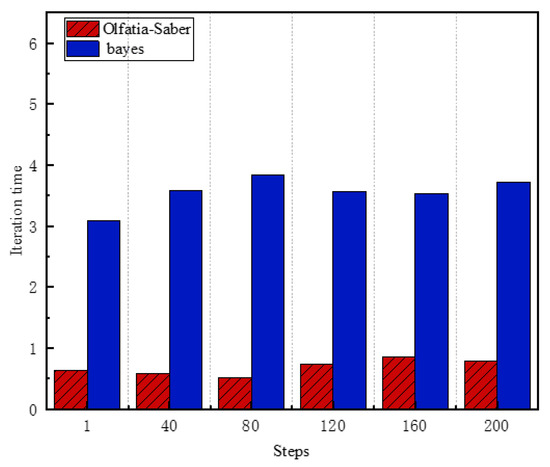

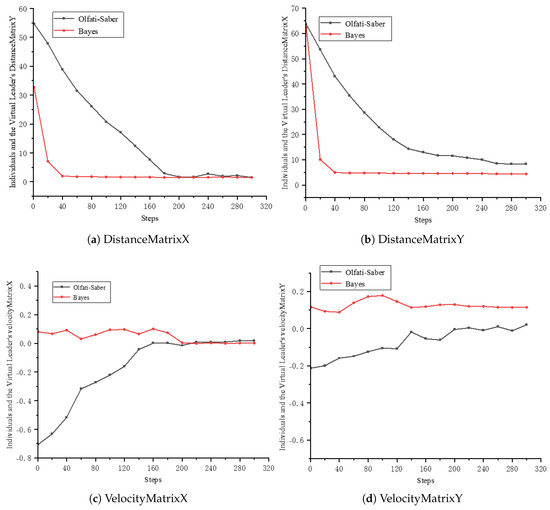

From the following Figure 3, it is clearly observed that compared to the traditional Olfati-Saber method, the iteration time using the Bayes method is significantly increased, which intuitively reflects the higher cost brought by the Bayes term in the calculation process. This is because the Bayes method needs to continuously integrate prior knowledge and real-time observational data during operation, updating the state of agents through complex probability calculations. However, this increase in computational cost is not meaningless. In swarm systems, the dynamic changes and uncertainties of the environment are challenges that cannot be ignored. The Bayes method, with its unique advantages, enables the swarm to better adapt to these complex situations, allowing agents to dynamically adjust their positions and velocities based on the state of their neighbors. Specifically, by calculating adaptive weights, the swarm can allocate weights more reasonably by combining the Gaussian kernel function considering relative positions and velocities, thereby more effectively integrating neighbor information with their own prior state. This mechanism allows agents to make better decisions when facing environmental changes. Although the Bayes method increases the computational complexity to some extent, it significantly improves the convergence quality.

Figure 3.

Comparison of computation time between the Olfati-Saber and Bayes information interaction models under identical simulation counts.

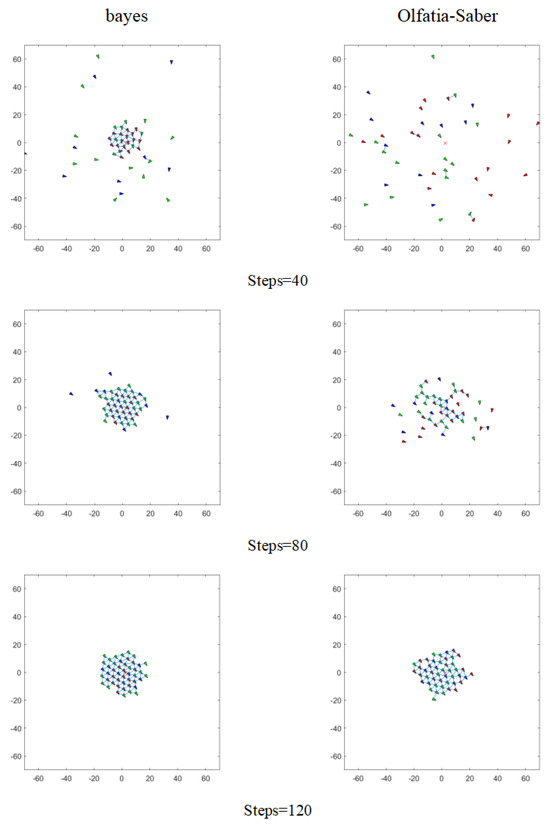

In Figure 4, the left side is the Bayes information interaction model, and the right side is the Olfati-Saber classical model. The Bayes method takes longer for each iteration, but its convergence process is more robust. As the number of iterations increases, the position and velocity deviations between agents gradually decrease with a lower fluctuation range, indicating that the system is more orderly and reasonable when converging to a stable state, better meeting task requirements. In contrast, the Olfati-Saber classical model may still exhibit slight oscillations after convergence. According to the three iterative process diagrams provided, the Bayes and Olfati-Saber classical models show significant differences in dynamic evolution (Iteration = 40, 80, 120). When Iteration = 40, the Bayes information interaction model gradually aggregates information between agents through its unique probability update mechanism, causing the probability distribution to show a preliminary aggregation trend, and the posterior probability begins to deviate from the prior distribution. This is because Bayes updates its probability estimates in a progressive manner based on the neighbor information received each time, while the Olfati-Saber model has not yet established strong connections between agents. When Iteration = 80, the Bayes information interaction model continues to perform local interactions between agents, and these gradual accumulations of information interactions have a significant effect, with the probability density function showing significant modal differentiation, fully demonstrating the “cumulative evidence effect” of Bayes. Each small-scale information interaction is like accumulating evidence, gradually shaping the form of the probability distribution, while the classical model begins to show significant aggregation. When Iteration = 120, the Bayes posterior distribution is basically stable. In this process, Bayes continuously adjusts its state through small amounts of information exchange with neighbors, while the classical model has just entered the collaborative stage. Both models have completed convergence, but the Bayes posterior distribution presents a unimodal symmetric form. It can be seen from the figure that compared to the classical model, the Bayes method requires significantly fewer iterations. Although both models will show convergence after a certain number of iterations, the Bayes method has already stabilized completely, while the Olfati-Saber classical model may still exhibit slight oscillations.

Figure 4.

Comparison of simulation times between the Olfati-Saber classical model and the Bayes information interaction model.

In profound contrast, our Bayesian model ensures that at every iteration step, all agents adhere to the rules for symmetric information communication. This symmetry is algorithmically embedded through a unified protocol: each agent, without exception, executes the same Bayesian update rules. Consequently, the agent’s control input is not a mere reaction to the immediate snapshot of its neighborhood but a symmetrically balanced synthesis of its past state (prior) and current observations (posterior). This process effectively distributes the system’s “attention” over a short history, smoothing out the response to transient perturbations and noisy measurements. The inertia from a previous direction of motion is not disregarded but is intelligently balanced against new neighbor information, allowing for smoother directional changes and mitigating the overshoot–undershoot cycle.

Furthermore, the symmetry of information exchange within each identical time step operates in synergy with the physical force symmetry embedded in the potential function. While the force law ensures momentum conservation and prevents internal divergence, the Bayesian term ensures that the application of these forces is carried out in a temporally consistent and reasoned manner. This dual-layered symmetry—physical and cognitive—is the cornerstone of the observed robust stability. The system does not merely converge, it converges along a smoother, more deterministic, and energy-efficient trajectory, effectively filtering out the noise and myopic decisions that plague the purely reactive classical approach. This distinction underscores a paradigm shift from reactive control to predictive and historically aware coordination, where symmetry in decision-making over time is key to achieving superior collective stability.

As shown in Figure 5, the comparison of position standard deviation between the classical Olfati-Saber model and the Bayesian information interaction model reveals that the incorporation of the Bayesian term markedly accelerates swarm convergence. The curves clearly indicate that the position error in the Bayesian model decreases substantially faster with increasing iterations and stabilizes more rapidly. This improvement stems from the model’s ability to adaptively aggregate neighbor information via Gaussian kernel weighting. Leveraging the incremental learning nature of Bayesian updating, the model dynamically balances historical states and new neighbor information. It quickly counteracts inertia from the previous direction during initial turns, while leveraging the positional influence of neighbors in the new direction to form a swift turning resultant—demonstrating high swarm consistency.In contrast, the classical Olfati-Saber model requires multiple iterations to accomplish directional correction, leading to delayed response and often inducing unnecessary fluctuations and energy dissipation during repeated adjustments.

Figure 5.

Distance matrix and velocity matrix between individuals and the virtual leader in the Olfati-Saber and Bayes information interaction models. (a) This heatmap shows the distance in the X-direction between each individual agent and the virtual leader over time. (b) This heatmap displays the distance in the Y-direction between individuals and the virtual leader. (c) This heatmap illustrates the velocity difference in the X-direction between each agent and the virtual leader. (d) This heatmap represents the velocity difference in the Y-direction.

Correspondingly, the other two plots illustrate how the Bayesian information interaction model substantially alters the characteristics of inter-agent relative velocity differences. While the classical Olfati-Saber approach—relying solely on instantaneous neighbor information—results in pronounced short-term oscillations and slow convergence in velocity differences, the Bayesian method enables more intelligent velocity regulation by learning from historical interaction data. It mitigates noise through adaptive weighting and effectively utilizes influential neighbors. Owing to the integration of historical trends, the Bayesian model smooths the velocity difference profile and achieves faster convergence, underscoring its enhanced robustness. Even under noisy conditions, it maintains stable velocity synchronization.

This divergence is most critical in the velocity and distance difference. The model’s symmetric rule consistency across iterations enables a coordinated dynamics, allowing it to gracefully orchestrate velocity matching as a smooth, system-wide transition. In stark contrast, the classical model’s velocity profile exhibits the oscillatory “chatter” characteristic of a purely reactive system that lacks this temporal balancing. The former demonstrates the smooth, predictive harmony of a well-conducted orchestra, while the latter resembles the disjointed efforts of individuals reacting only to their immediate neighbors’ last move.

In conclusion, Figure 5 visually certifies that the Bayesian framework, through its symmetric integration of information across both the spatial and temporal domains, transforms the swarm’s convergence from a disjointed negotiation into a symphonic alignment, where the emergent macroscopic order is a direct and faithful reflection of its symmetric microscopic rules.

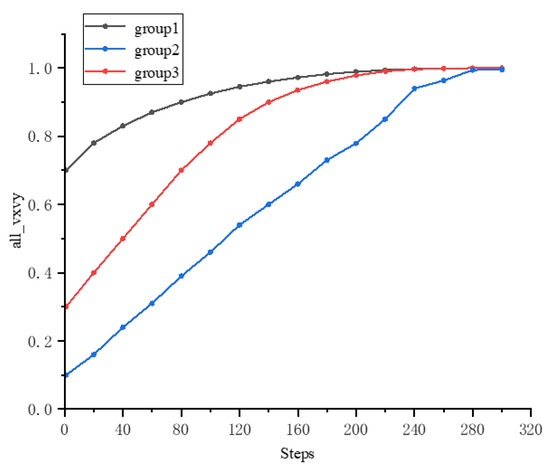

The evolutionary trajectories of the position and velocity information rates, depicted in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively, provide a compelling narrative of the Bayesian model’s capacity for symmetry restoration and adaptive, staged convergence. These curves transcend mere performance metrics; they vividly illustrate how the model orchestrates a sophisticated dynamical process that systematically erases initial asymmetries to achieve a unified, optimal state.

Figure 6.

Position information variation curve.

Figure 7.

Speed information rate curve.

Firstly, the convergence patterns of all three groups—despite their starkly different initial conditions ( 1: 0.7, 2: 0.1, 3: 0.3)—onto the same optimal trajectory is a powerful demonstration of behavioral symmetry emergence. The system does not perpetuate the initial informational asymmetry; instead, the universally applied symmetric Bayesian rule acts as a great equalizer. It guarantees that the collective outcome is not dominated by a privileged few but emerges from a fair and consistent iterative process applied to all. This final state, where all groups coincide, represents a symmetrized equilibrium achieved through distributed intelligence. Secondly, the distinct, multi-stage convergence paths reveal an intelligent and resource-efficient strategy. 1, with its high prior awareness, forms a rapid convergence nucleus. Its swift ascent creates an informational gradient that actively pulls the rest of the system forward. This is not a simple averaging but a directed diffusion of certainty, where 2 and 3 are dynamically recruited into the consensus. The Bayesian cascade effect ensures that the high-confidence signals from 1 are not diluted but are amplified and propagated through the network, guiding the less informed groups. Finally, the remarkable asymptotic stability and smoothness of the curves, especially for 3, underscore the model’s noise resilience. The system exhibits minimal overshoot or hesitation, indicating that each belief update is a precise and calculated step within a coherent, long-term strategy. This smoothness is the hallmark of a system that has learned to distill true signal from noise, achieving robustness not through rigidity, but through intelligent, evidence-based adaptability.

In summary, Figure 6 and Figure 7 do not just show that the system converges; they reveal a sophisticated dynamical narrative, showing how a system, governed by symmetric rules at the individual level, can intelligently manage initial asymmetries through staged, gradient-driven convergence, ultimately restoring symmetry at the global level with remarkable efficiency and stability.

The foregoing results demonstrate the effective convergence of the Bayesian framework under the setting of baseline parameters. To investigate the model’s performance under varying parameter settings, we systematically adjusted key parameters such as the learning rate and perception radius r, and evaluated changes in the convergence speed and stability of the population.

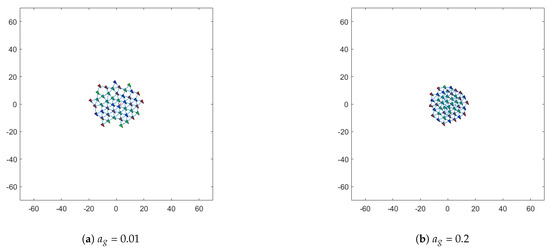

As shown in Figure 8, comparative analysis based on learning rate parameters indicates that when = 0.01, a dispersed distribution pattern emerges locally. Agents become overly reliant on their own prior knowledge, causing delayed information propagation within the group. When = 0.2, overly dense clusters form in certain regions. Agents overreact to local information, resulting in energy loss within the system. Therefore, both excessively high and low learning rates disrupt the smoothness and stability of the consensus process, preventing the group from forming a stable aggregation structure.

Figure 8.

Performance comparison under different safety radii d. (a) Convergence state with = 0.01. (b) Convergence state with = 0.2.

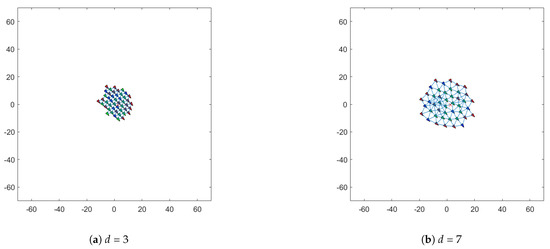

As shown in Figure 9, comparative analysis based on safety radius indicates that when d = 3, the internal distribution becomes uneven and chaotic, with excessive density in localized areas triggering internal oscillations. When d = 7, the group exhibits an abnormally loose spatial distribution, resulting in longer propagation paths within the group and excessive internal space leading to resource wastage. Therefore, both excessively high and excessively low safety radii disrupt the spatial structural equilibrium of the group, leading to decreased collaborative efficiency and compromised stability.

Figure 9.

Performance comparison under different learning rates . (a) Convergence state with d = 3. (b) Convergence state with d = 7.

Therefore, the systematic experimental validation of this model’s parameter combinations not only ensures the formation of group cohesion but also avoids structural oscillations and resource wastage. This provides a foundation for stable coordination and efficient operation of swarm intelligence in dynamic environments.

In summary, the parameters designed in this model exert varying influences on group convergence at different stages of the convergence process. During the rapid convergence phase, ensures 1 can leverage its higher prior information to swiftly adjust its state toward the virtual leader via the Bayesian formula. Given the random initial positions of individuals, provides sufficient short-range repulsion to effectively prevent collisions during the initial rapid movement, clearing obstacles for the formation of orderly aggregation. As 1 gradually stabilizes, the symmetrical information exchange enables the perception radius r to serve as a physical channel for information propagation. 2 and 3, possessing lower prior information, continuously integrate neighboring state information into their posterior estimates under the coordination of through the attraction generated by , achieving robust and smooth information diffusion. During the final convergence phase, the safety distance d provides equilibrium for the entire system, establishing optimal inter-agent spacing. The symmetric force fields of and rapidly correct minor deviations, suppressing oscillations to ensure the global stability and smooth convergence of the cluster’s final state.

It is important to note that the effectiveness of the current model relies on the ability of individuals to maintain interactions through local information exchange. Within a specific perception radius r, Bayesian rules can effectively facilitate coordination and consensus among agents. However, when the distance between individuals exceeds the perception radius, extreme cases such as sparsity may arise. In such scenarios, local information exchange becomes challenging. Although agents cannot directly update and integrate neighborhood states via Bayesian rules, they can still follow specific behavioral patterns at the macro level, maintaining a certain convergence trend—albeit with more complex paths and reduced stability. This analysis reveals how information symmetry evolves between ideal connectivity and extreme sparsity, clarifies the model’s applicability boundaries and points the way for research into maintaining swarm intelligence under more stringent communication constraints, revealing how information symmetry evolves between ideal connectivity and extreme sparsity.

5. Conclusions

This paper has systematically investigated the role of the Bayesian theorem in swarm collective behavior through a modeling framework grounded in principles of symmetry. By integrating theoretical analysis, model construction, and simulation experiments, we have demonstrated how a Bayesian decision-making framework enables robust and adaptive collective intelligence in multi-agent systems. Simulation results confirm that belief convergence is achieved when environmental information is consistent and prior knowledge is concentrated. Under such conditions, the swarm exhibits temporal and structural symmetry in its convergence process, with all agents progressively aligning their states through iterative Bayesian updates. Notably, even in the presence of conflicting information or strong social influence, the system shows the capacity to resist maladaptive information cascades or restore consensus after disruption, highlighting the role of dynamic symmetry restoration embedded in the Bayesian mechanism. When faced with ambiguous or insufficient information, the swarm relies on incremental belief revision—a form of stepwise symmetric updating—that ensures stable adaptation without erratic collective shifts.

While the proposed Bayesian model, with its inherent symmetric structure, offers a principled approximation of real-world swarm dynamics, several limitations define the scope for future work. First, the model does not fully capture irrational or emotionally driven deviations often present in biological and social systems. Second, although simulation-based validation confirms theoretical advantages, physical platform experiments are necessary to evaluate performance under real-world sensing and actuation constraints. Finally, the primary purpose of setting the virtual leader as a static target in this paper is to validate the performance of our proposed symmetric Bayesian framework in agent information exchange for the first time in a controlled experimental environment. However, we acknowledge that, in practical applications such as robotic search and rescue or autonomous fleets, leaders often exhibit dynamic and noisy characteristics. This provides a clear path for future research exploring the performance of the Bayesian framework when tracking moving targets and when subject to misleading information. Such scenarios would rigorously test the robustness and adaptability of symmetric Bayesian interaction mechanisms.

In future research, we will focus on three key challenges: introducing realistic constraints—such as dynamic obstacles and communication delays—to study symmetry breaking and recovery; improving computational efficiency to enable large-scale swarm emulation while preserving functional symmetry; and developing more sophisticated noise-handling mechanisms to maintain robustness under asymmetric uncertainty. Despite these challenges, our model demonstrates potential in addressing specific challenges. Currently, we have incorporated a decay factor into the Bayesian update rule to investigate the issue of information obsolescence caused by communication delays. This factor does not simply discard outdated information but instead smoothly attenuates the influence of neighboring nodes’ historical states. Preliminary analysis indicates that even in scenarios with significant delays, this mechanism effectively reduces the variance of state errors during convergence, ensuring the group maintains robust aggregation properties and consensus stability. Furthermore, in preliminary studies involving obstacles, we observed that although obstacles disrupt local spatial symmetry, the model guides the group through Bayesian updating rules to achieve coordinated obstacle avoidance and reconfiguration, thereby preserving the group’s overall integrity and stability. Therefore, the Bayesian symmetric framework established in this work provides a valuable theoretical foundation and a scalable methodological paradigm for swarm intelligence, with promising applications in adaptive robotics, distributed sensing, and complex system simulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and X.-B.C.; methodology, H.S.; software, H.S.; validation, H.S., Y.Y. and X.-B.C.; formal analysis, H.S. and P.Y.; investigation, H.S. and C.L.; resources, H.S. and P.Y.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, H.S.; visualization, H.S.; supervision, X.-B.C. and Y.Y.; project administration, X.-B.C. and P.Y.; funding acquisition, X.-B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 71571091 and Grant 71771112.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Opinions and social pressure. Sci. Am. 1955, 193, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, S. The small world problem. Psychol. Psychol. Today 1967, 1, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective dynamics of `small-world’ networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahwan, I.; Cebrian, M.; Obradovich, N.; Bongard, J.; Bonnefon, J.F.; Breazeal, C.; Crandall, J.W.; Christakis, N.A.; Couzin, I.D.; Jackson, M.O.; et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 2019, 568, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, A.; Stubbersfield, J.M. Large language models show human-like content biases in transmission chain experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2313790120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, M.H. Reaching a consensus. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1974, 69, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedkin, N.E.; Johnsen, E.C. Social influence networks and opinion change. Adv. Group Process. 1999, 16, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hegselmann, R.; Krause, U. Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence models, analysis and simulation. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2002, 5. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:8130429 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Deffuant, G.; Neau, D.; Amblard, F.; Weisbuch, G. Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. Adv. Complex Syst. 2001, 3, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couzin, I.D.; Krause, J.; Franks, N.R.; Levin, S.A. Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature 2005, 433, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, P.M.; Shmueli, E.; Griffiths, T.L.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Pentland, A. “Sandy”. Bayesian collective learning emerges from heuristic social learning. Cognition 2021, 212, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, J.; Rauhut, H.; Schweitzer, F.; Helbing, D. How social influence can undermine the wisdom of crowd effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9020–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, M.; Abd El-Latif, A.A. Intelligent computational methods for multi-unmanned aerial vehicle-enabled autonomous mobile edge computing systems. ISA Trans. 2023, 132, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, S.I.; Bekey, G.A. Distributed multirobot localization. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2002, 18, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, K.; Pavez, J.; Louppe, G. Approximating likelihood ratios with calibrated discriminative classifiers. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.02169. [Google Scholar]

- Burov, S.; Tabei, S.M.; Huynh, T.; Murrell, M.P.; Philipson, L.H.; Rice, S.A.; Gardel, M.L.; Scherer, N.F.; Dinner, A.R. Distribution of directional change as a signature of complex dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19689–19694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, J.B.; Kemp, C.; Griffiths, T.L.; Goodman, N.D. How to grow a mind: Statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 2011, 331, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S.; Hirshleifer, D.; Welch, I. A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 992–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, M.; Shapiro, J.M. Media bias and reputation. J. Political Econ. 2006, 114, 280–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyster, E.; Rabin, M. Naive herding in rich-information settings. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2010, 2, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfati-Saber, R. Flocking for multi-agent dynamic systems: Algorithms and theory. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2006, 51, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfati-Saber, R.; Murray, R.M. Consensus problems in networks of agents with switching topology and time-delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.W. Flocks, Herds and Schools: A Distributed Behavioral Model. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Anaheim, CA, USA, 27–31 July 1987; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Semnani, S.H.; Basir, O.A. Semi-flocking algorithm for motion control of mobile sensors in large-scale surveillance systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2014, 45, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).