Improved YOLOv5s-Based Crack Detection Method for Sealant-Spraying Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A sealant-spraying device is designed to automate the sealing process for train door cracks.

- (2)

- An enhanced YOLOv5s object detection algorithm is developed, demonstrating improved performance in detecting sealing targets.

- (3)

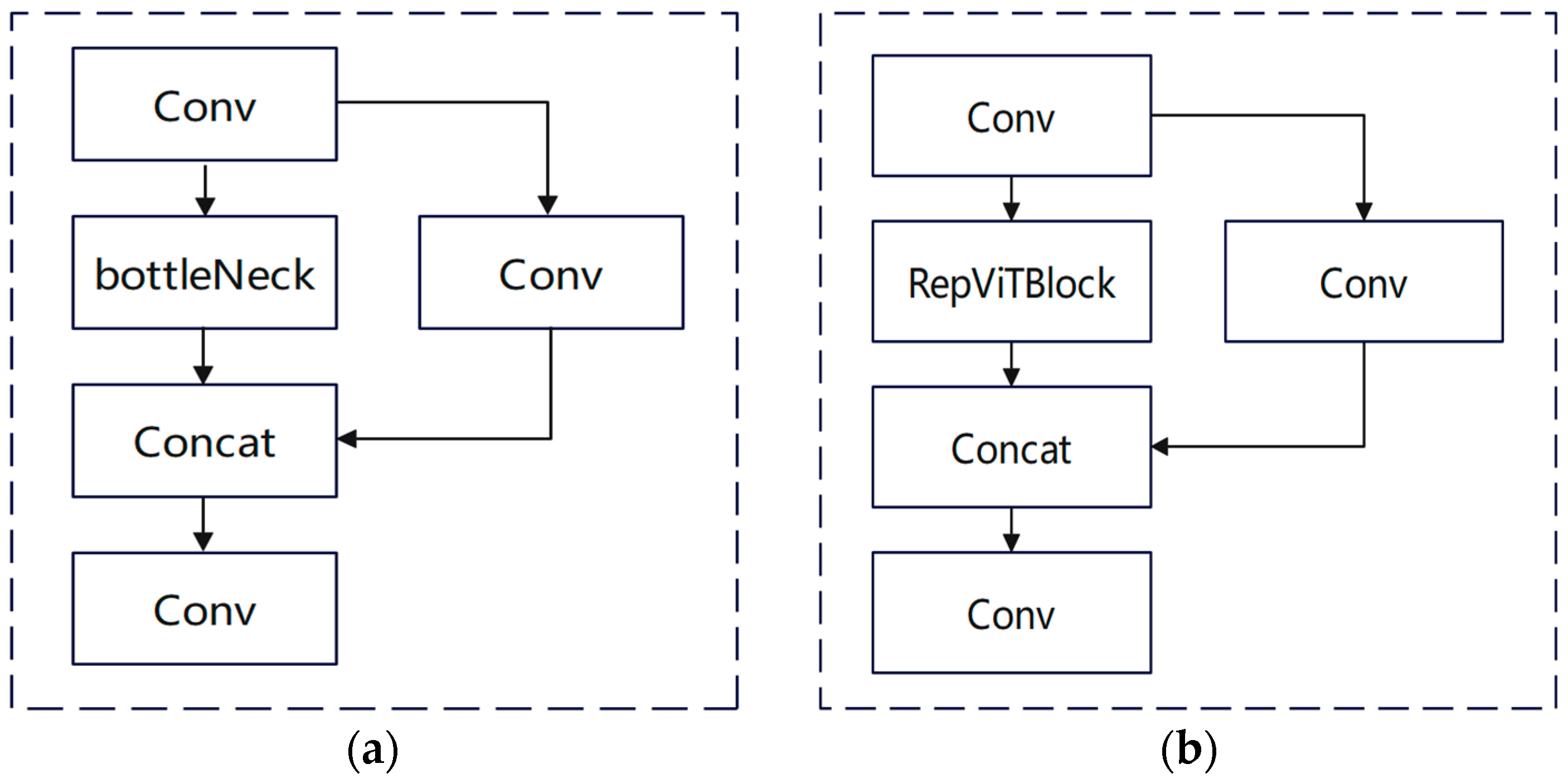

- The integration of C3 and re-parametrized Vision Transformer (RepViT) blocks into the YOLOv5s network achieves model lightweighting and inference acceleration while maintaining detection precision.

2. Positioning and Spraying Scheme for Train Door Cracks

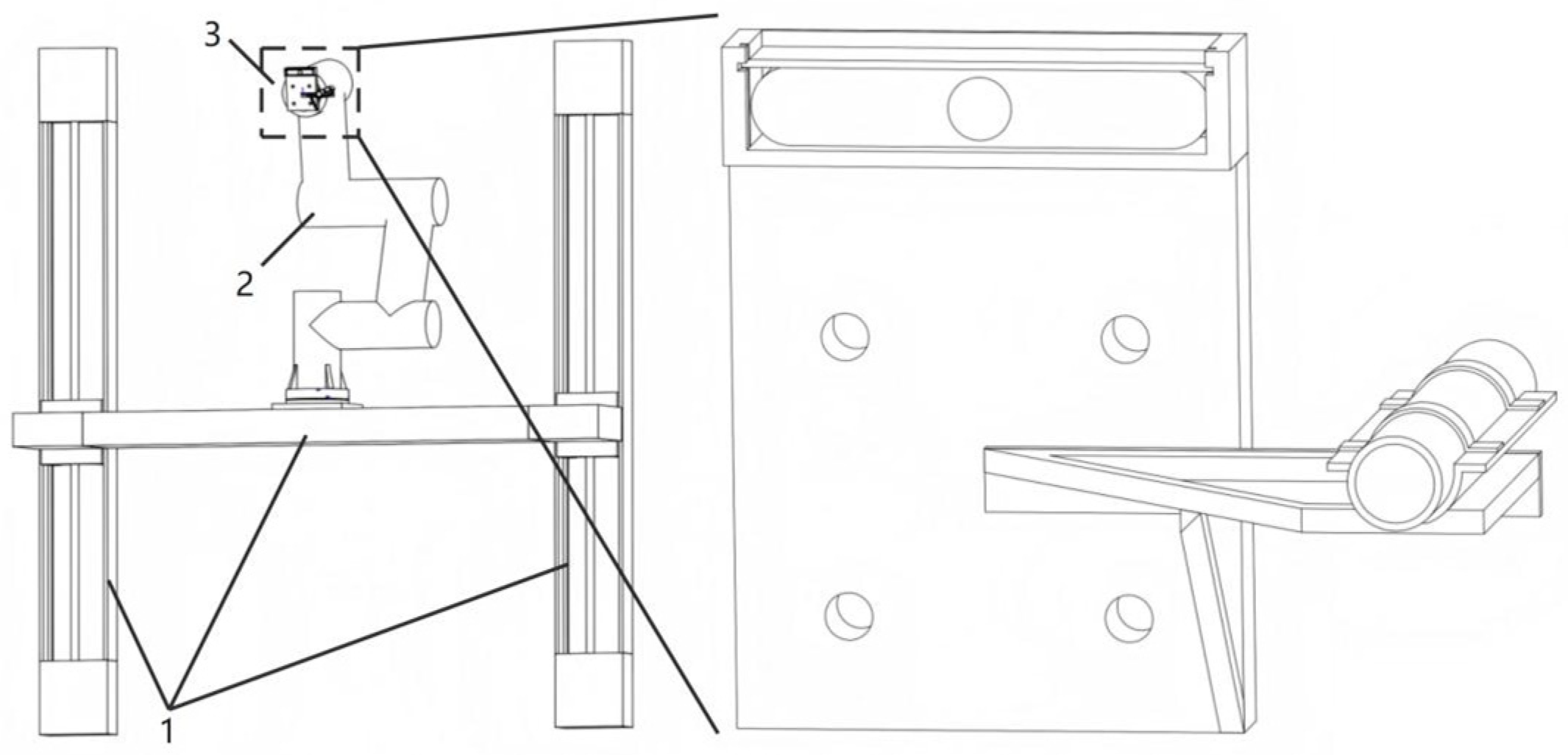

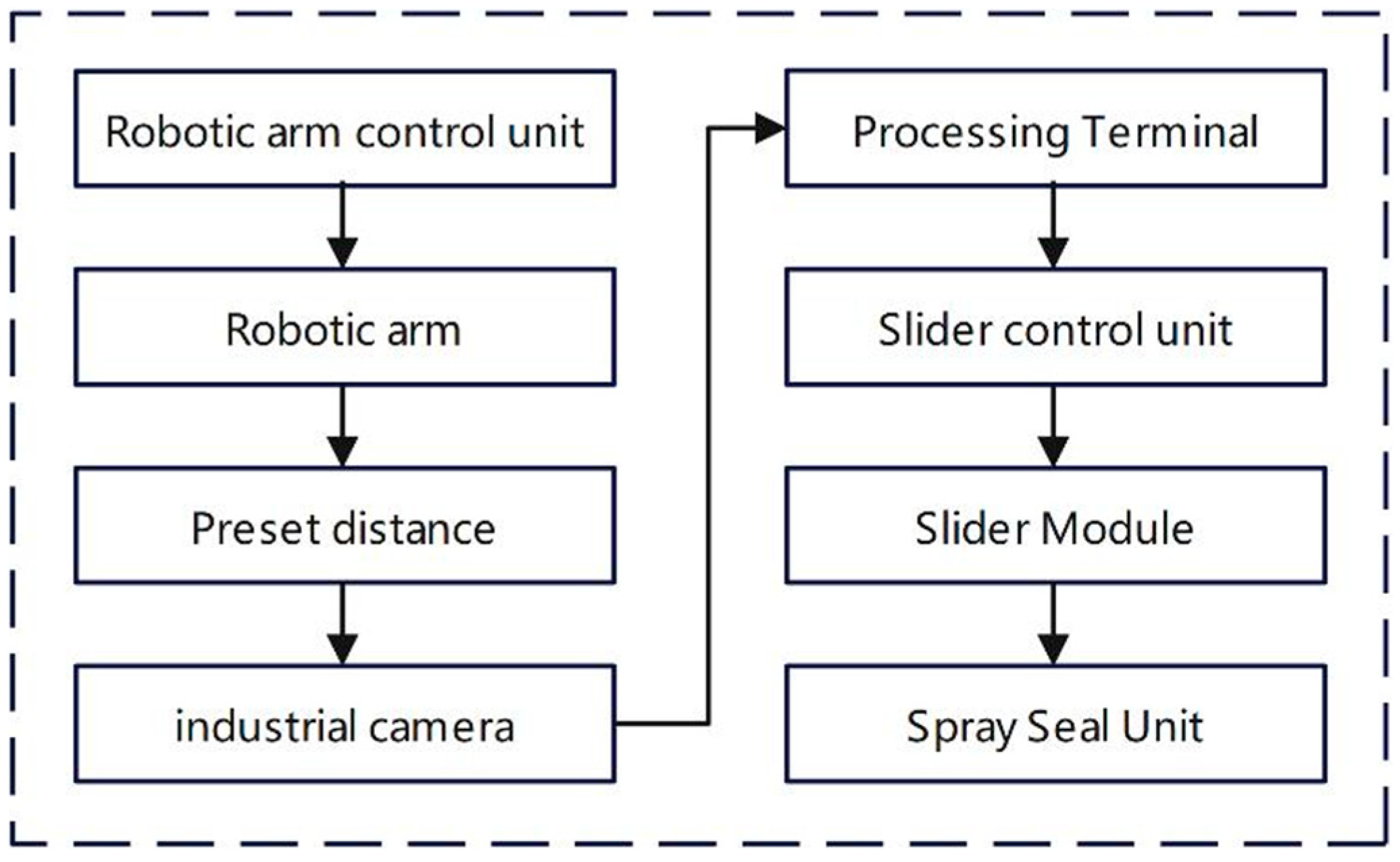

2.1. Sealant-Spraying Device Overview

2.2. Train Door Sealing Process

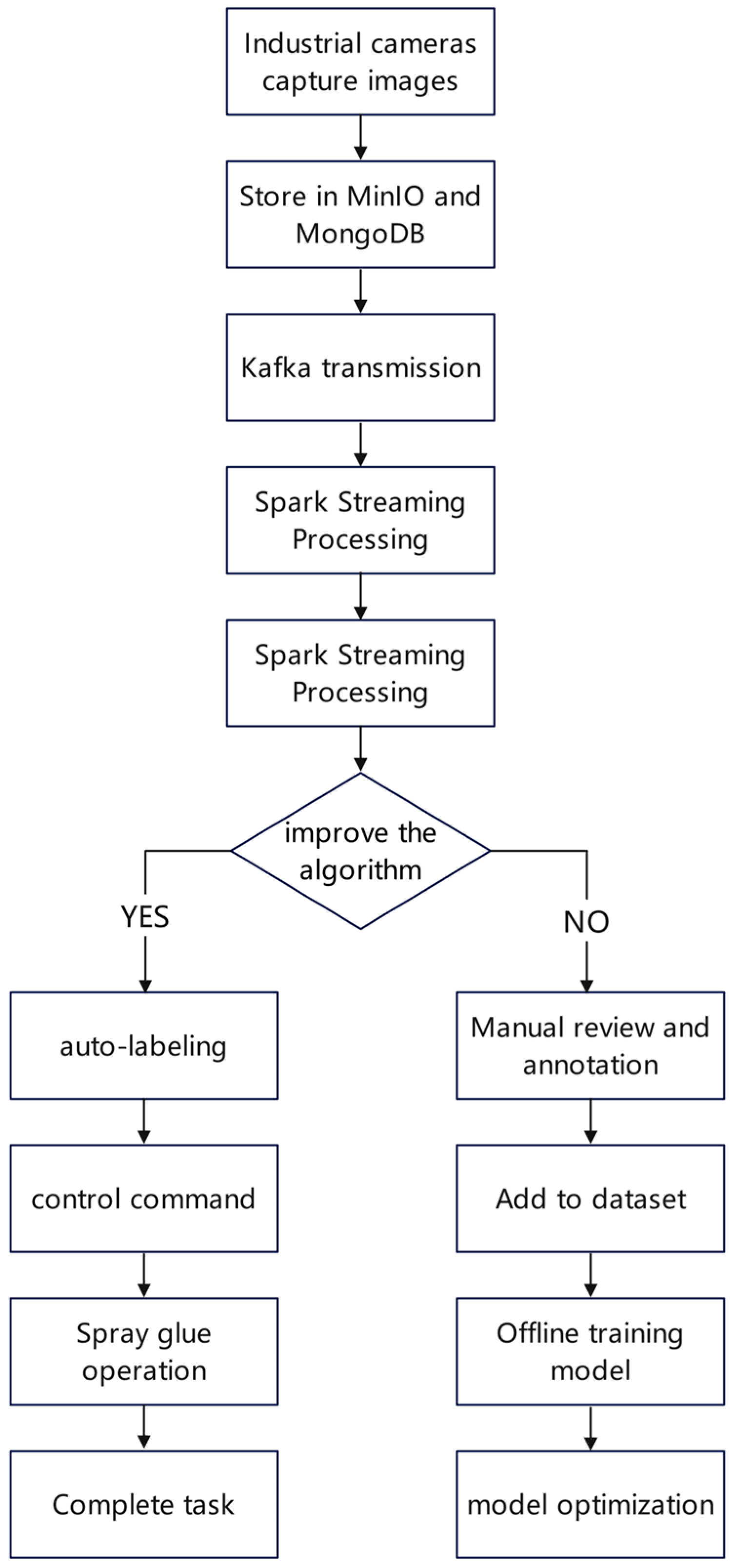

2.3. Technical Workflow of the Improved Algorithm

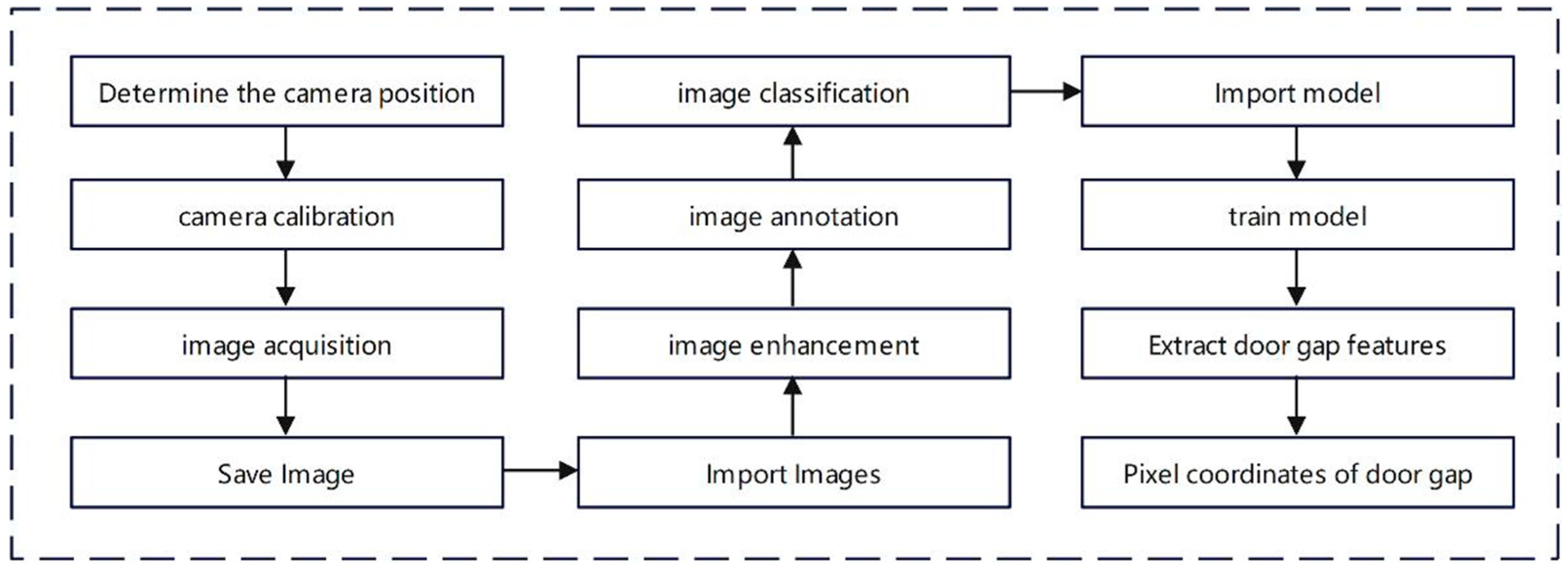

3. Camera Calibration

4. Improved YOLOv5s Network

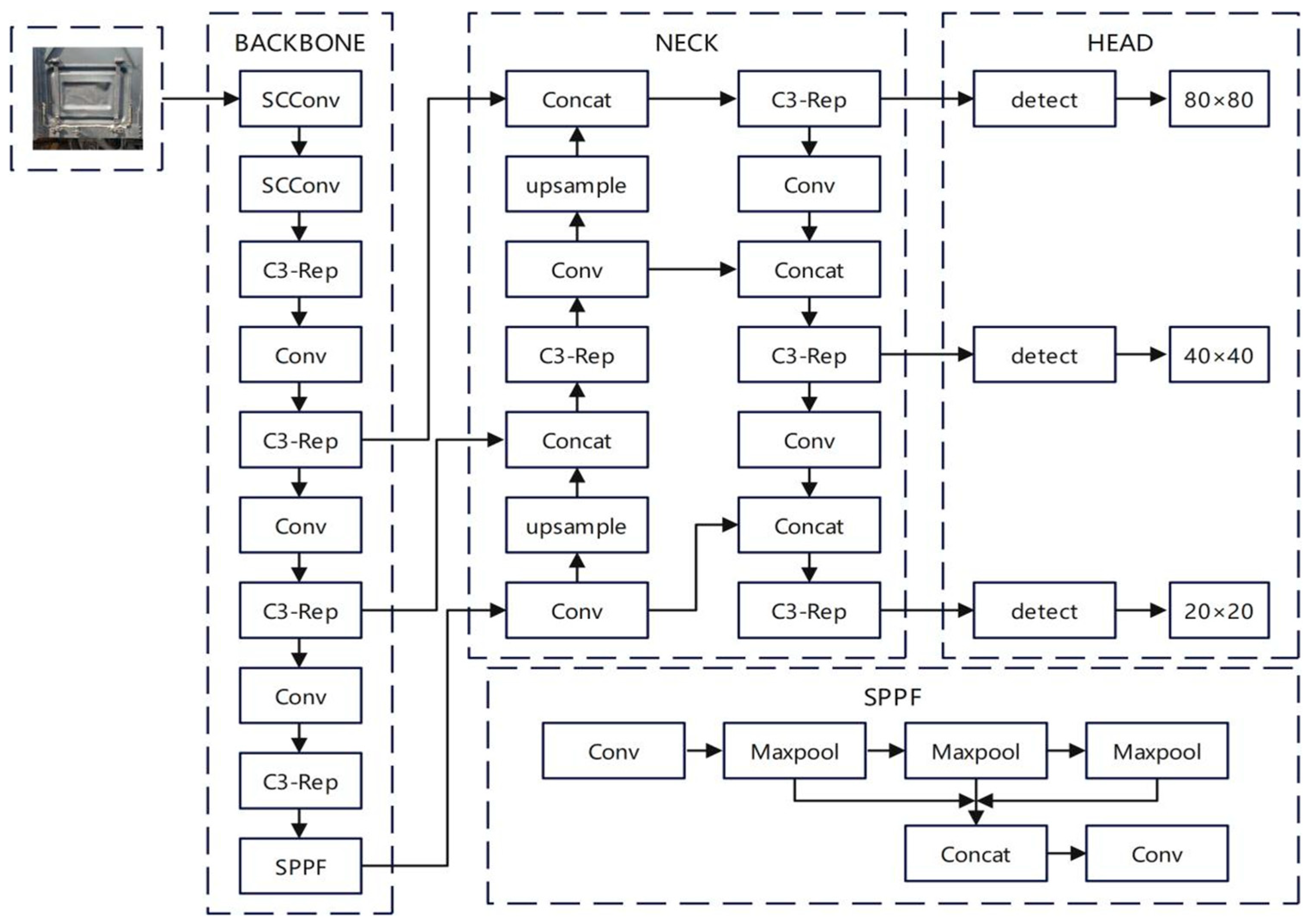

4.1. Network Structure

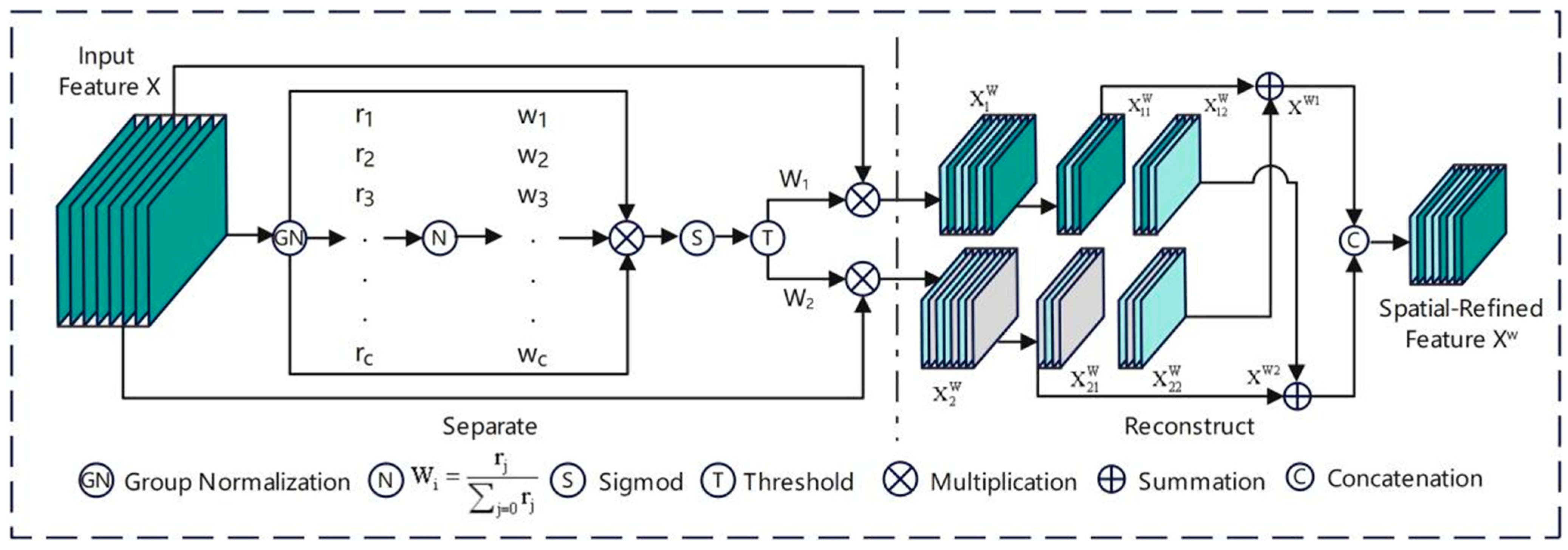

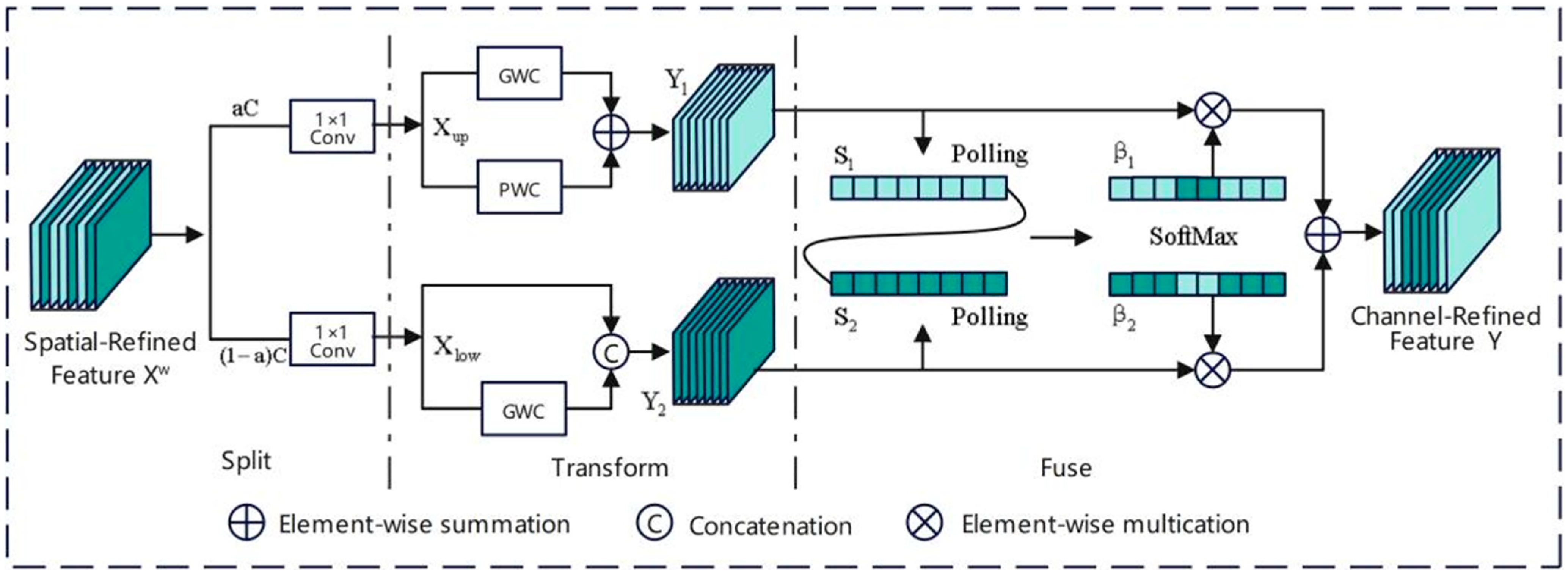

4.2. SCConv Module

4.3. C3 Module

4.4. Loss Function

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. Configuration of the Running Environment

5.2. Image Acquisition and Dataset Production

5.3. Evaluation Indicators

5.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

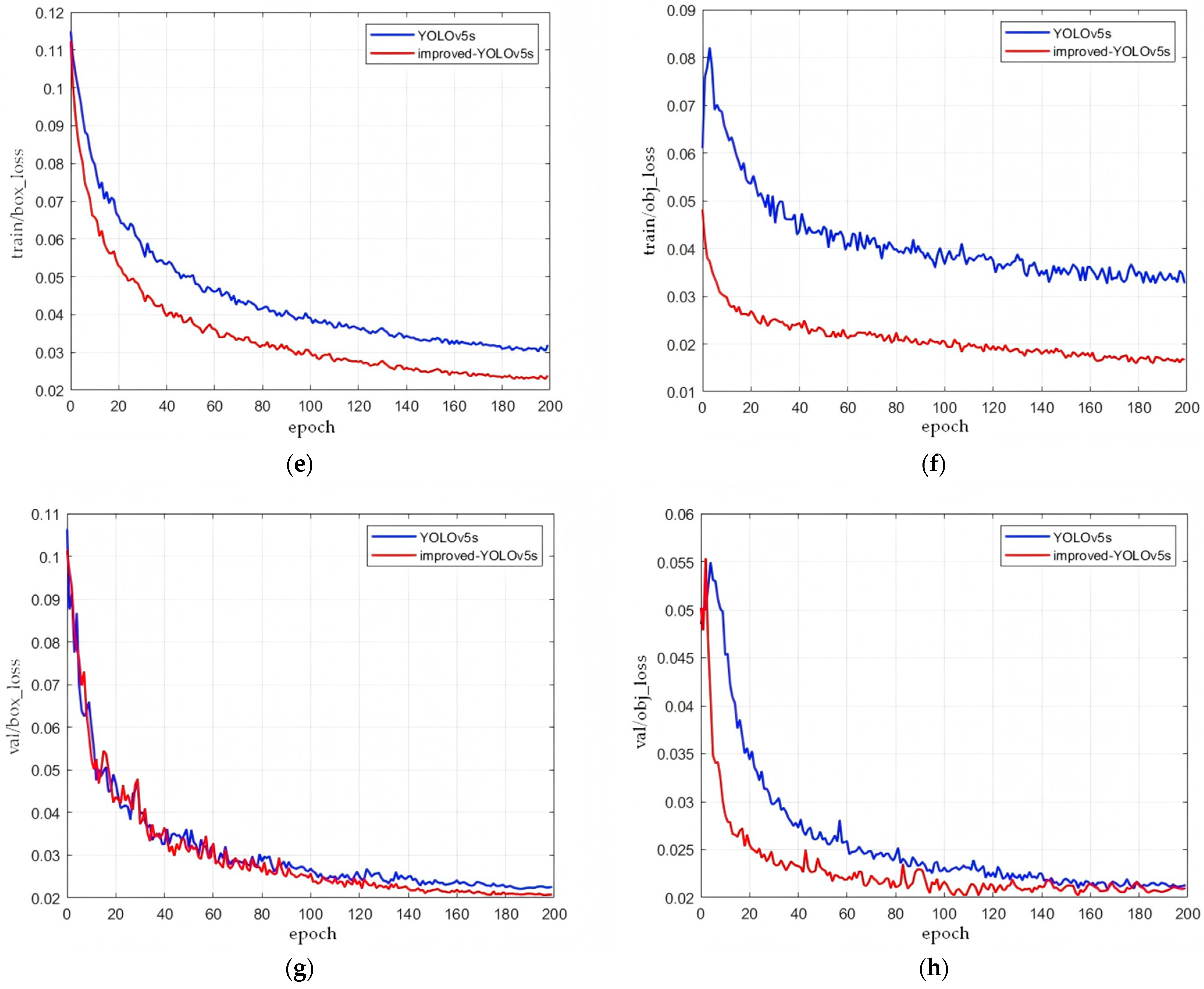

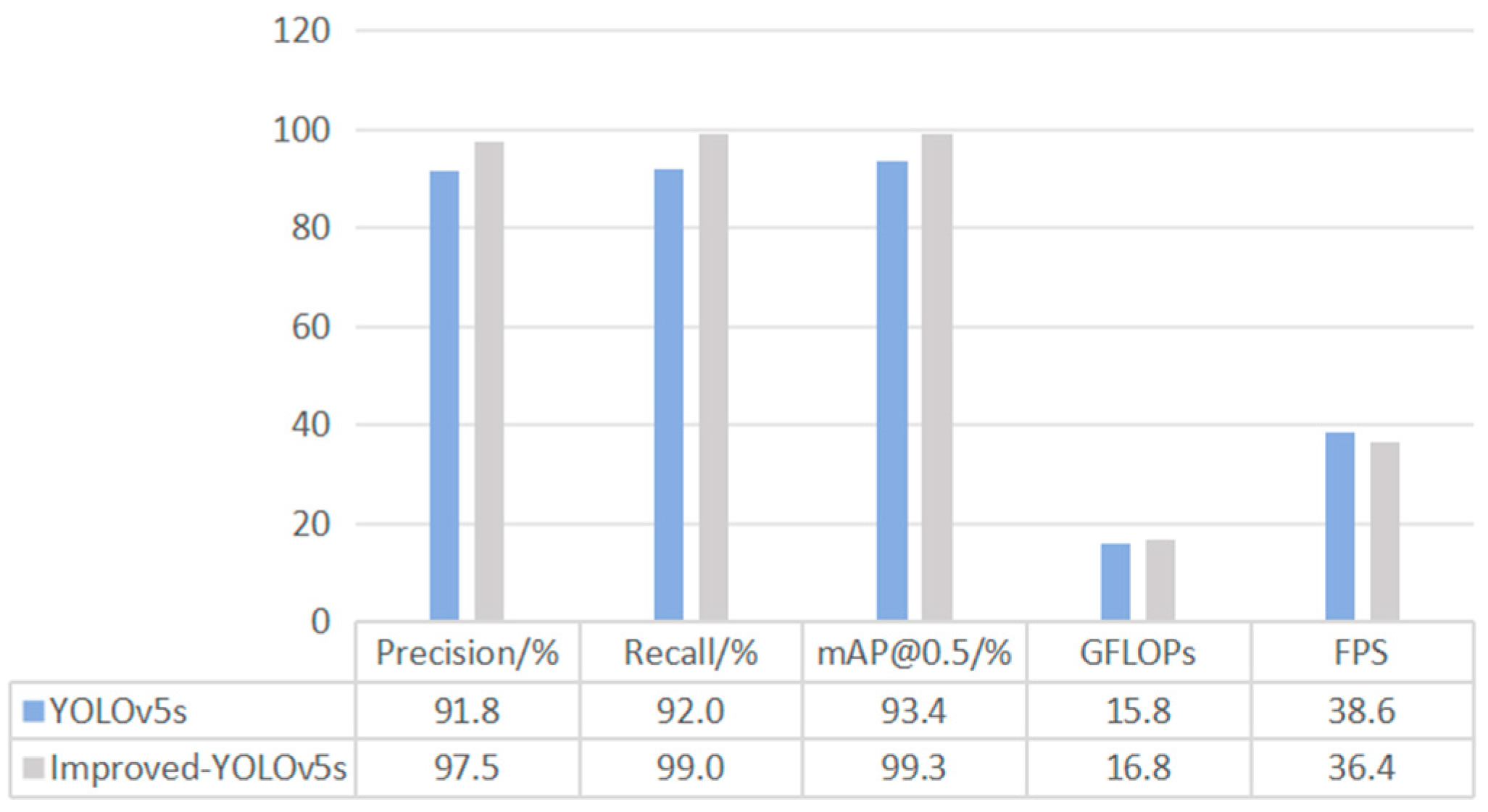

5.4.1. Ablation Experiment

5.4.2. Comparative Experiments of Different Models

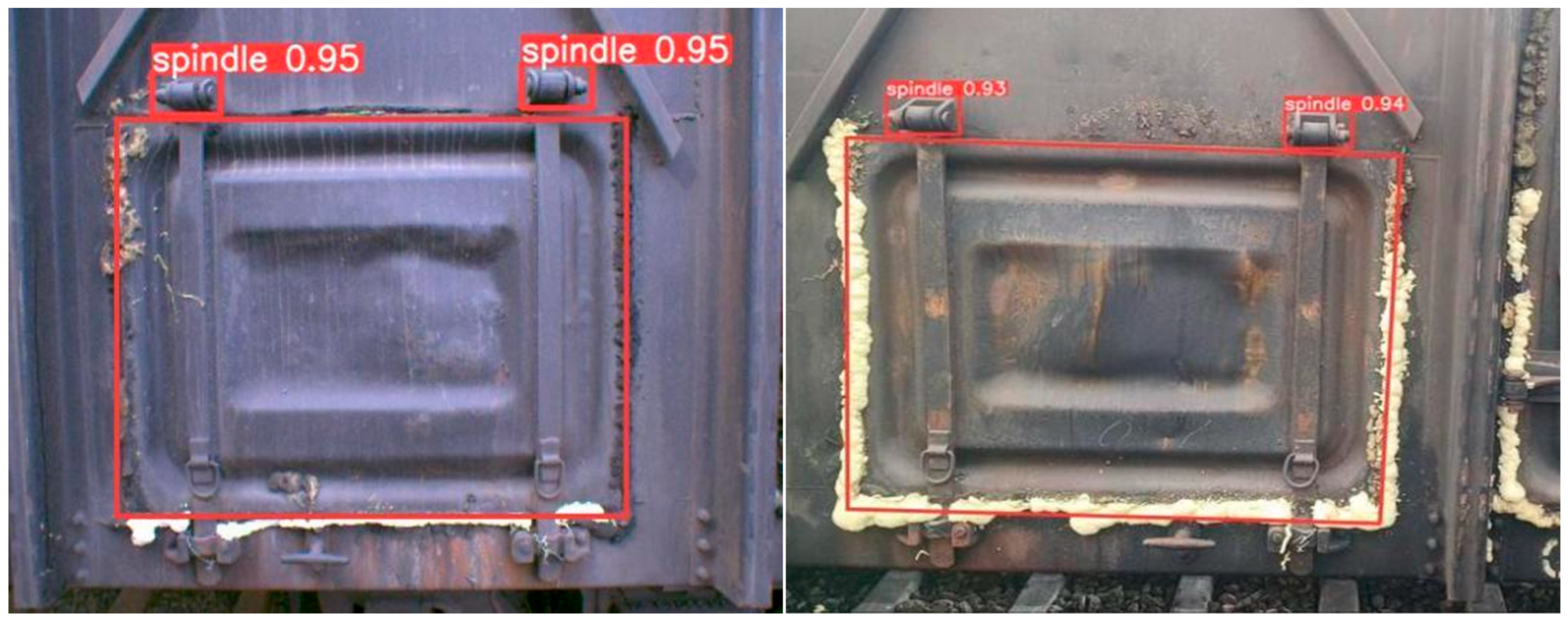

5.5. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vijayakumar, A.; Vairavasundaram, S. YOLO-based Object Detection Models: A Review and its Applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 83535–83574. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeser, T.; Bachofer, F.; Kuenzer, C. Object Detection and Image Segmentation with Deep Learning on Earth Observation Data: A Review—Part II: Applications. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hwang, K.I. YOLO with adaptive frame control for real-time object detection applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 81, 36375–36396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, R.; Li, X.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M. YOLO-MS: Rethinking Multi-Scale Representation Learning for Real-time Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 4240–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xu, W. Multi-Oriented Object Detection in High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery Based on Convolutional Neural Networks with Adaptive Object Orientation Features. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Han, Y.; Wang, S. Object feedback and feature information retention for small object detection in intelligent transportation scenes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121811–121825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Xu, S. A Deep Learning Model for Transportation Mode Detection Based on Smartphone Sensing Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 5223–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, I.E.C.; Padilha, R.M.S.; Paz, R.F.; Zuanetti, D.A. Automated high-resolution microscopy for clinker analysis: A divide-and-conquer deep learning approach with mask R-CNN and PCA for alite measurement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 293, 128552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.B.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Portland, OR, USA, 23–28 June 2013; Volume 10, pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.K.; Girshick, R.B.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. What is YOLOv5: A deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.20892v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yan, S.; Duan, C. A Lightweight Vehicles Detection Network Model Based on YOLOv5. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 113, 104914–104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushra, S.N.; Shobana, G.; Maheswari, K.U.; Subramanian, N. Smart Video Surveillance Based Weapon Identification Using Yolov5. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Systems and Intelligent Computing (ICESIC), Chennai, India, 22–23 April 2022; pp. 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Z.; Li, H.; Zuo, Z.; Pan, L. Design a Robot System for Tomato Picking Based on YOLOv5. IFAC PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, L. CNN and Transformer-based deep learning models for automated white blood cell detection. Image Vis. Comput. 2025, 161, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaur, B.; Mishra, K.K. Small-object detection based on YOLOv5 in autonomous driving systems. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2023, 168, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasamurthy, C.; SivaVenkatesh, R.; Gunasundari, R. Six-Axis Robotic Arm Integration with Computer Vision for Autonomous Object Detection using TensorFlow. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Advances in Computational Intelligence and Communication (ICACIC), Kakinada, India, 21–22 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Flexible camera calibration by viewing a plane from unknown orientations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision, Kerkyra, Greece, 20–27 September 2000; Volume 22, pp. 1330–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. SCConv: Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution for Feature Redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6153–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. RepViT: Revisiting Mobile CNN From ViT Perspective. 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.09283 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU Loss: More Powerful Learning for Bounding Box Regression. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09283 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. 2020. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Ding, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, K.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Re-Parameterizing Your Optimizers Rather than Architectures. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.15242 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Wadekar, S.N.; Chaurasia, A. MobileViTv3: Mobile-Friendly Vision Transformer with Simple and Effective Fusion of Local, Global and Input Features. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.15159 (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

| Technical Name | Technical Specification |

|---|---|

| Name | CMOS industrial camera |

| pixel size | 3.45 μm × 3.45 μm |

| target size | 2/3′ |

| resolution | 2448 × 2048 |

| maximum frame rate | 24.1 fps |

| Parameter Name | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| image size | 640 × 640 |

| confidence threshold | 0.25 |

| IoU threshold | 0.45 |

| initial learning rate | 0.01 |

| weight decay | 0.0005 |

| epoch | 200 |

| Methods | Precision/% | Recall/% | mAP@0.5/% | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 91.8 | 92.0 | 93.4 | 15.8 | 38.6 |

| YOLOv5s + SCConv | 93.9 | 98.3 | 96.7 | 13.7 | 40.3 |

| YOLOv5s + RepViT | 92.4 | 96.3 | 98.1 | 12.3 | 41.3 |

| YOLOv5s + SLoU | 94.9 | 94.6 | 94.2 | 16.2 | 34.1 |

| YOLOv5s + SCConv + RepViT | 94.2 | 95.5 | 98.7 | 15.9 | 39.7 |

| YOLOv5s + SCConv + RepViT + SLoU | 97.5 | 99.0 | 99.3 | 16.8 | 36.4 |

| Methods | Precision/% | Recall/% | mAP@0.5/% | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 91.8 | 92.0 | 93.4 | 15.8 | 38.6 |

| YOLOv5m | 91.1 | 91.2 | 91.3 | 47.9 | 41.1 |

| YOLOv5l | 90.4 | 90.4 | 89.9 | 107.7 | 43.7 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 92.3 | 89.7 | 94.1 | 13.2 | 47.2 |

| YOLOv8s | 94.1 | 91.5 | 95.6 | 29.3 | 51.7 |

| YOLOv9-c | 95.6 | 93.2 | 95.9 | 102.1 | 54.5 |

| Improved YOLOv5s | 97.5 | 99.0 | 99.3 | 16.8 | 36.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, W.; Ding, H.; Cheng, Q.; Li, N.; Sun, X.; Dong, X. Improved YOLOv5s-Based Crack Detection Method for Sealant-Spraying Devices. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122089

Kong W, Ding H, Cheng Q, Li N, Sun X, Dong X. Improved YOLOv5s-Based Crack Detection Method for Sealant-Spraying Devices. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122089

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Weiyi, Hua Ding, Qingzhang Cheng, Ning Li, Xiaochun Sun, and Xiaoxin Dong. 2025. "Improved YOLOv5s-Based Crack Detection Method for Sealant-Spraying Devices" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122089

APA StyleKong, W., Ding, H., Cheng, Q., Li, N., Sun, X., & Dong, X. (2025). Improved YOLOv5s-Based Crack Detection Method for Sealant-Spraying Devices. Symmetry, 17(12), 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122089