Abstract

Urban intersections are critical nodes where traffic congestion and energy inefficiency converge. Traditional signal control systems often optimize either mobility or sustainability, creating an asymmetry between flow efficiency and environmental impact. This study introduces a symmetry-aware generative optimization framework that leverages Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) to balance both dimensions. Using the microscopic simulator SUMO, we modeled a signalized intersection in Colima, Mexico, under five control strategies: Fixed Time (baseline), GPT-4o, GPT-5 Thinking, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and DeepSeek V3. Each Large Language Model (LLM) received structured simulation data and generated new phase-duration configurations to minimize queue length, travel time, and CO2 emissions while improving average speed. Step-level performance was evaluated using descriptive statistics, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests paired with Holm–Bonferroni correction. Results show that all LLM-based controllers significantly outperformed the Fixed Time baseline (adjusted p ≤ 4.8 × 10−6), with large effect sizes (|dz| ≈ 1.5–2.6). GPT-5 achieved the strongest performance, reducing queue size by ≈ 44%, CO2 emissions by ≈ 17%, and increasing average speed by ≈ 58%. The results validate the feasibility of symmetry-aware generative reasoning for sustainable traffic optimization and establish a reproducible methodological framework applicable to future AI-driven urban mobility systems.

1. Introduction

Efficient urban traffic management has become a cornerstone of smart city development. Optimizing waiting times at signalized intersections is critical to improving mobility and reducing unnecessary energy waste in modern cities. Vehicular congestion and frequent stops at red lights create delays for commuters and cause excess fuel consumption and increased pollutant emissions [1,2]. In fact, vehicles idling at intersections represent a substantial share of greenhouse gas emissions in the urban transport sector. The constant cycles of acceleration and deceleration at traffic lights contribute directly to increased fuel consumption and urban air pollution [2]. Therefore, optimizing flow at these critical road network nodes is essential for advancing toward more sustainable cities and improving overall quality of life.

Several studies have quantified the negative impact of waiting times at traffic lights on energy use and the environment [3,4,5,6]. For example, research conducted in New Delhi estimated that fuel wasted daily by vehicles idling at intersections waiting for green lights amounts to approximately 9036 L of gasoline and diesel, along with 5461 kg of natural gas, a fuel loss valued at nearly USD 4.5 million annually [7]. Consequently, the associated greenhouse gas emissions reached almost 37 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per day at the studied intersections. These figures highlight how poorly managed traffic signals can exacerbate both environmental and economic problems: time spent waiting at red lights reduces transport efficiency while simultaneously producing avoidable emissions of CO2, methane, nitrogen oxides, and other pollutants. Environmental studies emphasize that reducing vehicle idling times at signalized intersections could significantly lower the transport sector’s urban carbon footprint and energy demand [1,7,8]. Addressing long waiting times at traffic lights, therefore, represents a clear opportunity to improve energy efficiency and mitigate the environmental impacts of urban traffic.

In the context of smart cities, various technological solutions have emerged to address these mobility challenges (such as traffic congestion, excessive waiting times at intersections, fuel waste, and pollutant emissions). Intelligent traffic management leverages artificial intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and the Internet of Things (IoT) to adapt signal operations to real-time traffic conditions dynamically [9]. For instance, synchronized traffic lights to create “green waves” or their red and green phases can be adjusted according to immediate demand in each direction [10,11]. Such innovations have already yielded tangible benefits in cities with intelligent traffic signal systems: real-time monitoring and adaptive control translate into smoother circulation, less congestion, and reductions in pollutant emissions [9]. A notable example is Poland, where the installation of an integrated traffic management system (TRISTAR) incorporating AI algorithms and IoT sensors reduced waiting times at heavily loaded intersections by up to 30 s during peak hours, accompanied by an estimated 10–15% drop in congestion in those periods [12]. This congestion relief directly affects energy efficiency: vehicles consume less fuel over their journeys by shortening stop durations. According to local authorities, introducing this system produced notable environmental benefits, including reduced fuel consumption and lower carbon emissions, improving air quality and resident well-being. These can demonstrate the considerable potential of traffic signal optimization to achieve more efficient and environmentally friendly urban mobility. However, these systems often prioritize mobility efficiency over environmental balance, creating an asymmetry between performance and sustainability that this study seeks to address.

Aligned with these global trends, recent research explores multiple approaches to minimize wasted time at traffic signals and their energy impacts. Some proposals focus on connected vehicles: for instance, Eco-Approach and Departure (EAD) strategies enable cars to adjust their speed when approaching intersections to pass during the green phase and avoid unnecessary braking [13]. Such solutions, enabled by vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication, can eliminate complete stops at intersections, thereby improving local traffic flow and energy efficiency. Researchers have also incorporated techniques for traffic signal coordination and adaptive control algorithms based on machine learning or mathematical optimization. For example, centralized signal coordination along arterial corridors (green waves) helps reduce pollutant emissions by ~10% in specific urban scenarios, by decreasing the frequency of stops and subsequent accelerations [2].

Furthermore, studies indicate that limiting excessively long signal cycles or prioritizing public transport and sustainable modes can balance system efficiency with emission reduction goals [14,15,16,17]. Although smoother traffic flow is generally associated with lower fuel consumption and fewer emissions, in practical traffic operations an imbalance may emerge because improvements in one movement or direction can worsen conditions elsewhere in the intersection. For instance, prioritizing flow efficiency on the major corridor often requires longer red times for minor approaches, increasing their idling and CO2 accumulation. Similarly, optimizing for minimal delays on through movements can reduce the time allocated to turning phases or conflicting flows, generating congestion spillbacks that offset environmental gains. These nonlinear interactions are especially pronounced under high-demand or near-saturation conditions, where small timing adjustments may improve throughput for one approach while degrading sustainability at others. In this work, we refer to this situation as a symmetry problem: the difficulty of simultaneously improving mobility and environmental performance across all competing flows in a complex intersection.

However, achieving simultaneous improvements in mobility (less congestion, shorter delays) and sustainability (lower energy use and emissions) remains a complex challenge: optimizing one dimension often compromises the other [18]. This tension underscores the need for integrated solutions that combine multiple strategies and technologies to maximize overall urban benefits.

Given the difficulty of experimenting with real-world traffic systems (due to safety, costs, and reproducibility concerns), computer-based simulation has become an indispensable tool in this field. Microscopic traffic simulators (such as VISSIM, SUMO, Paramics, among others) allow researchers to model vehicle behavior and signal control in great detail, providing a virtual laboratory for testing optimization schemes without disturbing actual traffic [19,20]. Numerous studies have validated the effectiveness of simulations in estimating potential fuel and time savings before implementing changes in real networks [21,22,23,24,25]. Building on this established methodology, the present study conducted a simulation-based experiment to evaluate traffic signal timing optimization strategies in Colima, Mexico. It is important to highlight this from the outset: simulation enabled us to model intersections in Colima under different intelligent control scenarios, quantifying the effects on key indicators such as travel time, fuel consumption, emissions, and congestion in a controlled way. In essence, the study sought to determine, in a simulated environment, the extent to which these indicators improved by reducing the seconds vehicles spend waiting at red lights.

Colima, the capital of one of Mexico’s smaller states, provides an ideal context for testing traffic signal optimization in a medium-sized urban environment. The city’s mobility relies heavily on private vehicles. Yet, its traffic infrastructure remains limited compared to larger metropolitan areas such as Mexico City or New York, where advanced systems are already in place. Despite ranking relatively low in national congestion indices, residents of Colima still spend dozens of hours each year in avoidable delays caused by inefficient signaling. This paradox, coupled with a high motorization rate driven by inadequate public transportation, makes Colima a representative setting where improvements in signal management can yield tangible mobility and environmental benefits. By focusing on this case, our study demonstrates the feasibility of intelligent traffic solutions beyond large metropolitan centers, highlighting their scalability to cities of similar size and infrastructure.

In fact, the literature provides strong support for selecting Colima as a suitable setting for this type of experimentation, particularly because of its size and infrastructure. Recent research on Colima’s urban mobility highlights how globalization and economic growth have reshaped its transportation dynamics, emphasizing the city’s representativeness as a medium-sized metropolitan area facing the challenges of modernization and sustainable mobility [26]. Likewise, Stanford University conducted a field study in Colima to observe pedestrian interactions with autonomous vehicles, directly contrasting them with behaviors in Mexico City [27]. The results revealed that while pedestrians in Mexico City tended to cross proactively in front of the autonomous vehicle, those in Colima were more cautious, often stopping before crossing. Thus, Colima offers a controlled yet representative environment for exploring how generative AI can improve intersection performance in medium-sized urban networks. This highlights how local mobility patterns and cultural behaviors can shape the interaction with emerging technologies, consolidating Colima as an ideal scenario for piloting traffic innovations tailored to real-world, mid-sized contexts.

However, we must emphasize that although this study focuses on Colima, its findings and methodology are scalable to other cities. The principles of traffic signal optimization and the applied technologies can be transferred to urban areas with similar characteristics, whether in Mexico or other regions, by tailoring the model to local demand and scale. Ultimately, this research aims to contribute to understanding how reducing waiting times at traffic lights positively influences energy efficiency and key indicators of urban performance, serving as a reference point for innovative city initiatives in Colima and beyond.

In this study, “symmetry” refers to the balanced optimization of two competing objectives in urban traffic management: mobility efficiency (e.g., reduced queue length, shorter travel time) and environmental sustainability (e.g., lower CO2 emissions). The goal is to avoid favoring one at the expense of the other. “Generative reasoning” denotes the capacity of LLMs to infer structured, context-aware outputs (such as optimized timing plans) based on simulation data and natural-language prompts. Unlike rule-based or reward-driven approaches, generative reasoning enables the model to internalize trade-offs and propose coherent solutions that align with multiple objectives without explicit multi-objective programming.

It is important to note that in this framework, LLMs are not used as predictive models of traffic behavior, but as optimization assistants that interpret simulation summaries and propose adjusted signal timings through generative reasoning.

Research Contributions

This study introduces a novel framework for symmetry-aware optimization in traffic signal control, in which an LLM interprets simulation feedback and proposes timing adjustments that jointly improve mobility efficiency and environmental sustainability. The contributions are as follows:

- Conceptual contribution: We introduce a methodological framework that leverages Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) to achieve symmetry between mobility efficiency and environmental sustainability. The framework explicitly balances conflicting objectives (queue length reduction, travel time minimization, and CO2 emission mitigation) within a unified optimization loop.

- Methodological integration: We operationalize LLMs as optimization aids within a closed-loop pipeline, coupling microscopic simulation (SUMO) with natural-language-based reasoning to generate interpretable and adaptive signal configurations.

- Empirical validation: We evaluate four LLM-based controllers (GPT-4o, GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and DeepSeek V3) against a fixed-time baseline, demonstrating statistically significant and practically meaningful improvements across all key traffic metrics.

The novelty of this work lies in coupling generative reasoning with deterministic simulation under a symmetry-aware paradigm. This approach provides an interpretable pathway for integrating LLM-driven decision support into real-world traffic systems, advancing the broader agenda of sustainable and intelligent urban mobility.

While prior research in AI-based traffic control (particularly reinforcement learning and heuristic optimization) has demonstrated substantial improvements in mobility, these approaches require explicitly defined reward functions or mathematical formulations that typically prioritize a single objective (e.g., delay reduction) or rely on complex multi-objective programming. It often leads to an inherent imbalance between traffic efficiency and environmental sustainability.

In contrast, the proposed symmetry-aware generative framework introduces a distinct methodological shift: instead of encoding optimization targets into an algorithmic objective function, we leverage large language models as reasoning agents that interpret simulation data and autonomously infer balanced timing adjustments. This integration of deterministic microscopic simulation with generative reasoning enables the model to internalize trade-offs between queue length, travel time, speed, and CO2 emissions without explicit multi-objective optimization. To our knowledge, this is the first work to apply and benchmark multiple state-of-the-art LLMs (GPT-5, GPT-4o, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and DeepSeek V3) as traffic-signal decision-support controllers within a reproducible SUMO-based workflow.

2. Related Works

Traffic signal control has long been a central topic in transportation research; however, the field has undergone a significant transformation with the rise of AI and machine learning [28,29,30]. Adaptive, data-driven strategies have gradually replaced traditional fixed-time schedules to reduce congestion and improve sustainability [31,32]. Current approaches fall into four interconnected directions. First, reinforcement learning has enabled the design of adaptive signal policies that continuously improve through interaction with simulated environments. Second, predictive models combined with advanced metaheuristic algorithms have provided effective tools for anticipating congestion and optimizing timing plans. Third, the recent incorporation of generative AI and large language models has opened new opportunities for urban analytics and decision support [33,34,35]. However, their direct application to traffic light optimization remains largely unexplored [36]. Ultimately, simulation remains the methodological backbone of this research, providing a safe and controlled environment to validate innovative control strategies before deployment in the real world [17].

A dominant paradigm in modern traffic signal control is deep reinforcement learning (DRL), where intelligent agents learn optimal signal timing policies through interaction with a simulated environment [37,38]. For instance, a multi-agent deep Q-network (DQN) system, where a dedicated DQN agent manages each intersection, has achieved a remarkable 44% reduction in vehicle waiting times compared to traditional fixed-timing methods [39]. Recognizing the scalability challenges of centralized RL systems, researchers have also developed federated reinforcement learning frameworks. In this approach, local agents at each intersection train on-site, while a global model aggregates their learned knowledge, enabling network-wide coordination and performance improvements without sharing raw data [40]. In addition to classical AI-based control methods, deep-learning approaches have been extensively applied to traffic speed prediction across large-scale networks [41,42,43,44]. Although the focus of the present study is not prediction but generative optimization, these works highlight the long-standing role of data-driven models in understanding traffic dynamics and provide additional context for the increasing integration of advanced AI techniques in transportation systems.

A parallel research thrust involves the integration of predictive analytics with advanced meta-heuristic algorithms. Khasawneh and Awasthi (2023) developed a system that first forecasts intersection-level congestion using a combination of time-series and machine learning models, including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Decision Tree (DT), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), and Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA), and then applies a novel Enhanced Bat Algorithm (EBAT) to optimize signal timing and minimize vehicle waiting time [45]. This method demonstrated significant reductions in traffic delays and emissions in simulations using data from Canada. Similarly, other hybrid approaches combine real-time data sources with new optimization algorithms. For example, Cheng et al. integrated computer vision (YOLO-X) for traffic flow estimation with a new Snake Optimization (SO) algorithm, achieving a 23.3% improvement in intersection delays over fixed-timing plans [46]. These studies highlight a trend toward fusing real-time sensing with sophisticated heuristics for tangible congestion relief.

More recently, the domain of urban studies has begun to explore the transformative potential of generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs). A systematic review by Xia, Tong, and Long identified a rapid increase in research leveraging GPT-style models for urban policy analysis, traffic demand prediction, and planning [47]. Studies have demonstrated that large language models like GPT-4 can serve as effective analytical co-pilots for transportation planners, outperforming smaller models in geospatial and simulation comprehension tasks [48,49,50]. Furthermore, pioneering work is underway to integrate generative AI into the core of smart city digital twins [17,51]. Huang et al. introduced a Large Flow Model (LFM), a generative framework designed to model and predict complex urban dynamics such as transportation and energy flows, aiding planners in optimizing infrastructure for sustainability [52].

Despite recent advances, optimizing traffic signal timing remains a multi-objective challenge, where improving mobility efficiency often conflicts with reducing energy use and emissions [17]. This imbalance (between smoother flow and environmental sustainability) defines the core of the symmetry problem in traffic management. Conventional AI and ML approaches usually optimize one dimension at the expense of the other, leaving real-time, balanced control largely unresolved.

To address this gap, the present study explores the use of Generative AI for symmetry-aware traffic light optimization, applying large language models (LLMs) to automatically propose timing configurations that balance traffic performance and environmental impact. This represents one of the first empirical efforts to benchmark next-generation models, such as GPT-5 and Gemini, in a smart-city traffic management context.

Recent advances have begun to explore the use of generative models for urban mobility and traffic control. Yuan et al. provide a comprehensive review of generative AI in vehicular systems, highlighting its role in traffic-flow generation and simulation-based decision-making for intelligent transportation infrastructures [53]. Similarly, Maksoud et al. conducted a systematic review of over 60 recent studies that applied large language models to transportation, identifying their transformative potential for traffic prediction, scenario generation, and control tasks [54]. Masri et al. proposed a novel use of LLMs as signal controllers at multi-lane intersections, showing promising results in real-time optimization and logical conflict resolution [55]. These works validate the growing interest in integrating LLMs into traffic simulation environments. Our study complements these trends by focusing on symmetry-aware generative reasoning embedded within a deterministic simulator.

Additionally, Xu et al. demonstrated that generative AI can be used to synthesize realistic vehicle behaviors in mixed-reality driving environments, enhancing virtual testing of control strategies [56]. At a larger scale, Tan et al. introduced SceneDiffuser++, a generative world model capable of simulating full city-scale traffic patterns and light-control schemes with high realism [57]. While these efforts emphasize data realism and behavior modeling, our framework offers a novel structure-centered optimization perspective by leveraging LLM-generated timing plans within SUMO.

In contrast to reinforcement-learning approaches and heuristic optimization methods, which require explicitly defined reward functions, performance metrics, or multi-objective formulations, our framework introduces a conceptual and methodological shift by positioning the LLM as a high-level generative reasoning agent. Instead of optimizing through iterative reward maximization, the model interprets aggregated simulation outputs in natural language and autonomously proposes signal-phase durations that jointly balance mobility and sustainability. This eliminates the need for explicit multi-objective programming and enables a symmetry-aware inference process not present in prior AI-based traffic optimization frameworks.

This methodological approach is well-established, as computer-based simulation is a cornerstone of urban mobility research, providing a safe and data-rich environment for testing new control strategies before real-world deployment. The use of microscopic simulators like SUMO and VISSIM is common across the literature [58,59,60,61]. Studies such as the one conducted in Maceió, Brazil, which used SUMO to evaluate traffic performance and guide signal interventions in a medium-sized city context, support this methodology’s relevance to Latin American cities [62].

Despite substantial progress in reinforcement learning, heuristic optimization, and more recent generative approaches, these systems generally depend on explicitly defined reward structures, performance metrics, or multi-objective formulations that prioritize a single dimension of performance at a time. As a result, they often improve mobility at the expense of sustainability or vice versa, particularly in intersections with competing flows and asymmetric demand. Moreover, prior generative approaches in urban analytics have focused primarily on prediction, planning, or scenario generation rather than direct signal-timing control. In contrast, the proposed symmetry-aware framework positions the LLM as a high-level reasoning layer capable of interpreting simulation summaries and inferring balanced timing plans without explicitly coded optimization objectives, addressing a gap left by previous AI-based traffic control systems.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we explain in detail the method used in this proposal to analyze the impact of generative AI (GAI) on vehicular traffic performance.

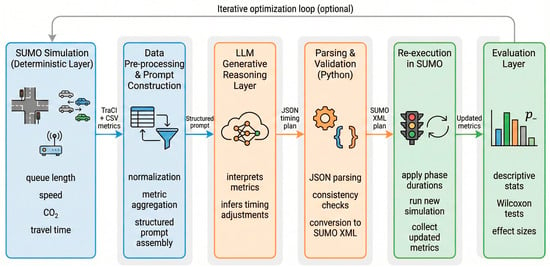

The methodological foundation of this work is a symmetry-aware generative optimization framework designed to balance mobility efficiency and environmental sustainability. The framework integrates three interdependent layers that interact in a closed-loop configuration:

- Simulation Layer (Deterministic Observation): a microscopic traffic simulation in SUMO provides detailed quantitative indicators of system performance, including average speed, queue length, travel time, and CO2 emissions.

- Generative Reasoning Layer (Adaptive Optimization): simulation outputs feed a Large Language Model (LLM) that interprets the data and autonomously generates new traffic-light phase durations aimed at minimizing congestion and emissions while maximizing flow efficiency.

- Evaluation Layer (Comparative and Statistical Validation): the LLM-generated configurations are re-implemented in the simulator, and their outcomes are compared statistically with the fixed-time baseline using descriptive and inferential methods (Wilcoxon tests with Holm–Bonferroni correction).

This cyclic interaction between deterministic simulation and generative reasoning establishes a symmetry-aware optimization process in which both mobility and sustainability objectives are co-optimized rather than treated as competing goals.

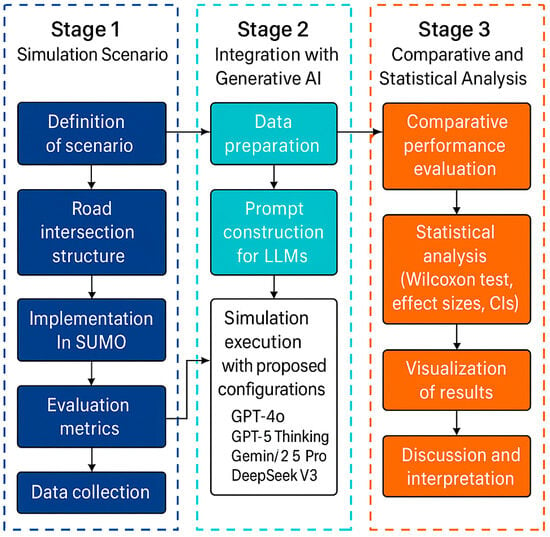

The overall process is illustrated in Figure 1, which represents the sequential workflow of the proposed framework.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed symmetry-aware generative optimization framework. The loop integrates microscopic simulation (SUMO), LLM-based generative reasoning, and statistical evaluation.

3.1. Simulation Scenario

The first stage was the simulation scenario creation and configuration. This stage consisted of several processes, as explained below.

3.1.1. Definition of Scenario

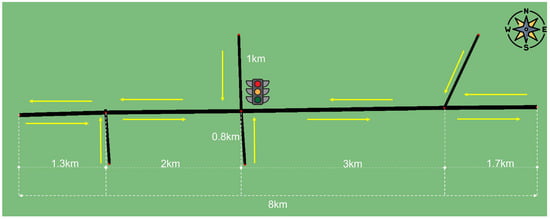

As part of the evaluation process, we defined a roadway environment, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Simulated urban road network in Colima, Mexico. The main avenue connects multiple segments and intersections, including signalized and secondary roads. This layout is used in SUMO to model realistic congestion patterns and test LLM-generated timing strategies. Yellow arrows indicate traffic flow directions along each road segment.

The roadway scenario consists of a main avenue with a length of 8 km. The main avenue is divided into segments of 1.3 km, 2 km, 3 km, and 1.7 km. In the first segment, a secondary road with a south–north direction connects. Two kilometers ahead, there is a road crossing controlled by a traffic signal. Three kilometers after that, another secondary road with a north–south direction connects.

The yellow arrows indicate the direction of traffic flow for each segment. The main avenue has two-way traffic (east–west and west–east) with three lanes per direction. The scenario set a constant traffic volume, assuming a stationary flow throughout the simulation time, with average values of 600 veh/h for the main avenue. The traffic volume for the secondary roads is 200 veh/h. The percentage of vehicles that turn at the intersection controlled by the signal is 20%. The vehicle speed within the scenario is limited to 50 km/h.

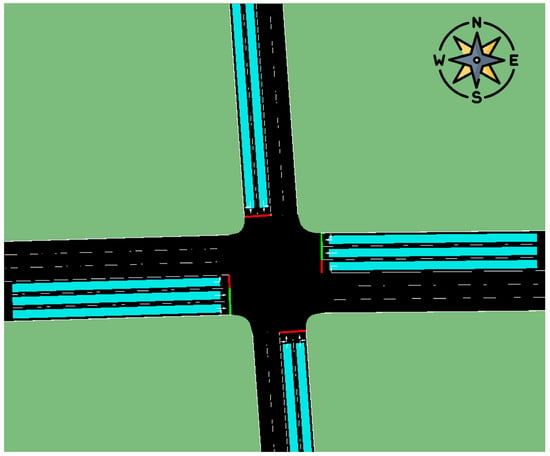

3.1.2. Road Intersection Structure

The crossing is structured as shown in Figure 3. The main avenue has three lanes; the two outer lanes allow through movement, and the inner lane allows left turning to enter the secondary road. U-turns are not allowed. On the other hand, the secondary road has two lanes; the outer lane allows through movement, while the inner lane allows turning left and entering the main avenue. U-turns are not allowed.

Figure 3.

Structure of the signalized intersection used in the simulation. The configuration includes through and turning lanes for both primary and secondary roads, reflecting real-world traffic dynamics. Colored markings indicate lane functions and control areas: cyan segments represent individual traffic lanes, red lines denote stop lines at the intersection, and green lines highlight pedestrian crossing boundaries or designated turning guides.

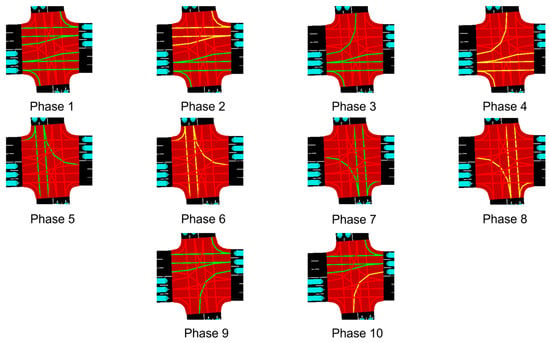

The traffic signal operates through a 10-phase sequence, as illustrated in Figure 4. Phase 1: green light for through movements in both directions of the main avenue. Phase 2: yellow light for east–west movements only. Phase 3: left turn permitted from west to east. Phase 4: yellow light for all west–east movements. Phase 5: green light for north–south and northeast-bound traffic. Phase 6: yellow light for those same movements. Phase 7: green light for traffic flowing from south to north and southwest. Phase 8: yellow light for those movements.

Figure 4.

Full 10-phase traffic signal cycle implemented in the simulation. Each phase controls specific vehicle movements at the intersection, and these durations are adjusted by the LLM-based controllers to optimize traffic flow and reduce emissions. Lane and color semantics correspond to those defined in Figure 3.

Phase 9: green light for east–west and east–south movements along the main avenue. Phase 10, yellow light for the east–south movement. Once Phase 10 finishes, the sequence restarts continuously.

Table 1 summarizes the configuration of each phase, indicating the green and yellow light durations for each vehicle movement.

Table 1.

Configuration values for traffic light durations across different phases.

The scenario represents real conditions in an urban area with high traffic demand, leading to significant congestion and pollutant emissions. The signalized intersection is a critical bottleneck for congestion formation. During red phases, vehicle accumulation produces queues that disrupt traffic flow along the main corridor and secondary approaches. Therefore, increasing travel times induces a stop-and-go driving pattern, which raises fuel consumption and emission levels.

Secondary approaches introduce additional traffic flows, generating priority conflicts and variations in operating speeds, further intensifying congestion during peak hours when inflows and outflows exceed roadway capacity. The corridor length and segmentation (ranging from 0.8 km to 3 km) enable the analysis of congestion propagation and the spatial distribution of emissions. This scenario is suitable for assessing traffic signal control and flow management strategies to reduce delays and air pollution levels.

The Fixed-Time controller used a static cycle plan derived from typical intersection signal timings observed in medium-sized Mexican cities. Green and yellow durations were assigned based on estimated average demand per approach and consistent with engineering practices for symmetric phasing, without dynamic adaptation. This configuration serves as a realistic baseline representing traditional, non-responsive traffic signal control still prevalent in many urban areas.

3.1.3. Implementation in the Simulation Tool

The scenario was modeled in SUMO (Simulation of Urban Mobility) [20], an open-source platform for simulating traffic in networks of varying complexity. The configuration included:

- Road network: intersection geometry with lane lengths, turning radii, and connections based on real data.

- Signal control: cyclic phase sequence implemented via an XML file specifying green and yellow durations, as described in Section 2.

- Vehicle behavior: acceleration, deceleration, driver imperfection, and minimum gap parameters are adapted from SUMO’s reference values for urban traffic.

- Measurement elements: virtual sensors used to capture key performance metrics of the scenario.

One hundred independent runs were conducted under identical demand and configuration conditions. Each run lasted 1000 simulation steps, preceded by a 50-s warm-up period to stabilize traffic flow. Demand was defined as a constant flow of 600 vehicles/h along the main corridor and 200 vehicles/h on secondary approaches, generated through static routes. Each run used a different random seed for demand and behavior generation to introduce variability in arrivals and internal maneuvers.

The scenario was configured using a constant demand level and SUMO’s default car-following and speed parameters. These controlled conditions are commonly used in simulation-based signal-control studies when the objective is to isolate the effects of the control strategy itself rather than reproduce full real-world heterogeneity. Ensuring identical demand patterns across all controllers allows direct comparability and prevents confounding differences arising from stochastic fluctuations. Although these assumptions simplify real traffic behavior, they provide a stable environment in which the contribution of the generative optimization framework can be evaluated transparently.

3.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

Four main metrics were defined to evaluate traffic performance in the proposed scenario:

- Average speed analyzes traffic behavior under given conditions. A decrease in this metric indicates congestion.

- Queue length is defined as the number of vehicles stopped at an intersection due to the traffic signal. It is measured as a count of cars, not as the waiting time, and is used to relate signal operation to congestion levels, travel time, and emissions.

- Travel time per trip represents the total time a vehicle requires to move from its origin to its destination. It is a key indicator of roadway efficiency and service quality perceived by users.

- CO2 emissions assess the environmental impact of traffic flow, directly linked to fuel consumption and operating conditions.

3.1.5. Data Collection

The defined metrics were collected using the built-in modules and SUMO control interfaces. Data were obtained through simulation elements such as detectors, queue detectors, and induction loop detectors, as well as through the TraCI module.

Metrics were recorded at two levels:

- Detector level: virtual sensors placed before the intersection captured vehicle queues (Queue) and instantaneous speed (Speed) during each phase.

- Aggregate level: average travel time (Travel_Time) of complete trips and mean CO2 emissions generated within the scenario were computed.

The specific TraCI functions used were:

- traci.vehicle.getSpeed(): recording instantaneous vehicle speeds to compute averages by segment or time interval.

- traci.lane.getLastStepVehicleNumber(): estimation of queue lengths by direction at the intersection.

- traci.vehicle.getAccumulatedWaitingTime() combined with the Travel Time Measurement (TTM) module: calculation of travel times from entry to exit.

- traci.vehicle.getCO2Emission(): measurement of CO2 emissions generated by each vehicle, later aggregated for analysis.

Vehicle arrivals were uniformly distributed, with no demand peaks. Drivers followed default SUMO parameters for priority rules, acceleration, and deceleration. Data were processed in Python and exported in CSV format for descriptive statistical analysis (mean, standard deviation, percentiles).

3.2. Integration with GAI

Figure 5 provides a schematic overview of the integration pipeline between SUMO and the LLM. Simulation outputs (queue length, speed, travel time, and CO2) collected through TraCI are exported as CSV files and normalized before being passed to the LLM as part of a structured prompt. The LLM returns a JSON file containing the proposed green and yellow timings for each phase. This JSON output is then parsed in Python, validated for structural consistency (e.g., non-negative durations and correct phase indexing), and automatically written to a SUMO-compatible traffic-signal XML file. The updated configuration is executed in a new SUMO run, completing one iteration of the symmetry-aware optimization loop.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the integration pipeline between SUMO and the LLM reasoning layer. Simulation data (speed, queue, CO2, travel time) is preprocessed and formatted into a structured prompt, which the LLM uses to generate new signal-phase configurations. These are parsed and re-implemented in SUMO, closing the symmetry-aware optimization loop.

The integration of Generative AI leverages the generative and reasoning capabilities of a Large Language Model (LLM) to automatically propose adjustments to traffic signal phase durations, balancing traffic flow and emissions, based on data obtained from SUMO simulations. In this work, three LLMs were used: ChatGPT (two versions: ChatGPT-4o and ChatGPT-5 thinking) developed by OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; Gemini (v 2.5 Pro) developed by Google, Mountain View, CA, USA; and DeepSeek (version V3) developed by the Chinese hedge fund High-Flyer, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. All LLMs operated under the same prompt and were isolated from each other to avoid cross-influence during inference.

The LLMs were not used to forecast traffic flows or predict future states. Instead, they served as generative optimizers, producing candidate timing plans based on structured prompts derived from prior simulation results. This role is closer to decision support than prediction.

3.2.1. Data Preparation

Simulation outputs were normalized to ensure consistency among variables. The normalized data were consolidated into a single CSV file for later use in training the LLM. An additional file containing the traffic signal phase configuration for the intersection defined in the simulation scenario was generated.

3.2.2. Prompt Construction for the LLM

At this stage, a structured prompt was designed to convey the essential elements of the simulation to the LLM. The prompt incorporated collected metrics (average speed, travel time, queue length, and emissions) and specified the optimization goal. This structure allowed the LLM to interpret the scenario context and propose an appropriate solution.

The output was requested in JSON format to facilitate direct integration into the experimental workflow.

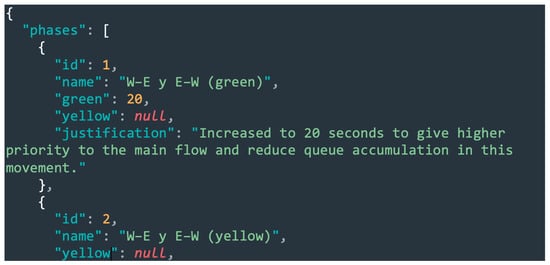

The defined prompt was as follows:

System: You are an expert in urban traffic management and simulation with SUMO. You are provided with two files containing relevant data for the simulated scenario. The first file, fases.csv, contains the configuration of the current duration of the traffic light phases. The second file, estadisticas.csv, reports the statistics collected during the scenario simulation in SUMO. Your mission is to propose adjustments to the green and yellow durations of each traffic light phase at an intersection in Colima, Mexico, to simultaneously reduce the average queue length (Queue) and travel time. The optimization objectives are: queue length less than 25 vehicles, CO2 level below 600 g, and travel time reduced by at least 15%. Based on the current configuration and the statistics: propose new green and yellow durations for each of the 6 phases of the traffic signal cycle. Briefly explain (1–2 sentences) the justification for each adjustment. Format the output as a JSON file with the following structure: { "phases": [ { "id": 1, "name": "W–E and E–W (green)", "green": /* new value in seconds */, "yellow": null, "justification": "..." }, { "id": 2, "name": "W–E and E–W (yellow)", "green": null, "yellow": /* new value in seconds */, "justification": "..." }, { "id": 3, "name": "N–S and S–N (green)", "green": /* new value in seconds */, "yellow": null, "justification": "..." }, { "id": 4, "name": "N–S and S–N (yellow)", "green": null, "yellow": /* new value in seconds */, "justification": "..." }, { "id": 5, "name": "Special turns (green)", "green": /* new value in seconds */, "yellow": null, "justification": "..." }, { "id": 6, "name": "Special turns (yellow)", "green": null, "yellow": /* new value in seconds */, "justification": "..." } ], "expectations": { "Average_Queue": "< 25 veh", "Average_CO2": "< 600 g", "Average_Speed": ">= 17.4 m/s", "Noise": "<= current peak value" } }

Figure 6 shows an example of the LLM results in response to the provided prompt.

Figure 6.

Example of LLM-generated output in JSON format, produced in response to simulation data and the optimization prompt. Each phase includes new green/yellow durations and a justification, allowing direct integration into the SUMO traffic control module.

3.2.3. Simulation Execution

The file generated by the LLM was implemented in the SUMO simulator. At this stage, system performance was observed under the signal phase durations suggested by the model, providing a practical evaluation of the usefulness of the LLM recommendations.

3.2.4. Parsing and Re-Implementation in SUMO

The JSON file returned by each LLM was parsed using Python’s json library. Each phase entry was mapped to the corresponding <phase> element in SUMO’s XML signal plan structure. Before implementation, the system performed basic validation steps (duration > 0; cycle length consistency; matching phase IDs). The updated timing plan was then exported as an XML file and loaded into SUMO through the TraCI interface. This procedure ensured that the generative recommendations were translated into deterministic control actions reproducibly across all models.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

A comparative analysis was conducted between the initial configuration (Fixed time) results and those produced by each LLM. This analysis enabled the assessment of the approach’s effectiveness, highlighting both the benefits and the potential limitations of integrating an LLM into traffic control optimization within SUMO.

3.4. Statistical Analysis of Controller Performance

We quantified step-level performance across five controllers (Fixed Time (baseline), Gemini 2.5 Pro, GPT-5 Thinking, GPT-4o, and DeepSeek) on four outcome metrics: average queue size, average speed, average travel time, and CO2 emissions (simulation units). We computed the mean and a two-sided 95% confidence interval for each controller and metric using a t-based interval over paired time steps (n = 34 steps retained after cleaning). We then conducted paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests contrasting each LLM-based controller against the Fixed Time baseline at the same steps. We report the rank-biserial correlation and Cohen’s dz for paired differences to characterize effect magnitude. To control the family-wise error rate across the four LLM comparisons per metric, p-values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni procedure. Numeric columns were coerced to numeric, and missing values were dropped per step before analysis.

Pairwise Wilcoxon details. Tests are two-sided with SciPy’s Wilcoxon (zero_method = “wilcox”) applied to paired step-level series (one value per controller per step). We report: n (paired steps), unadjusted p, normal-approximation z with continuity correction, rank-biserial correlation r_rb, Cohen’s dz for paired differences, Holm-adjusted p across the four LLM comparisons within each metric, and both absolute and percentage mean differences (mean_diff, mean_diff_pct, where positive indicates higher values than Fixed Time).

All analyses were implemented in Python (v3.12.12) using SciPy 1.16.2, ensuring full reproducibility.

4. Results

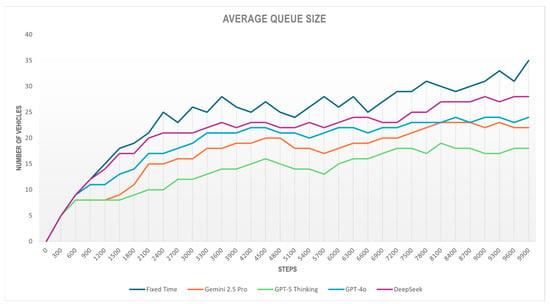

This section presents the results. Across all four metrics, every LLM-based controller significantly outperformed the Fixed Time baseline after Holm–Bonferroni correction (adjusted p ≤ 4.8 × 10−6 for all tests; n = 34 paired steps). Effect sizes were consistently large in absolute value (|dz| ≈ 1.5–2.6), indicating precise and practically meaningful improvements. The descriptive tables below summarize central tendency, dispersion, quantiles, and t-based 95% CIs for the mean. Immediately beneath each table, we provide the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test results vs. Fixed Time (including Δ and Δ%). Figure 7 shows the outcomes for the Queue metric, while Table 2 provides a statistical summary of the results for this metric.

Figure 7.

Comparative results for the average queue length metric for each method.

Table 2.

Statistical results summary for the Queue size metric.

Queue lengths under LLM-based control are consistently lower than those under Fixed Time control throughout the entire simulation, indicating that the strategy proposed by the language models contributes to more effective traffic management, reducing congestion levels.

Average speeds are higher for all LLM controllers than for Fixed Time. GPT-5 Thinking achieves the most significant gains, with sizable improvements also observed for Gemini 2.5 Pro and GPT-4o; DeepSeek exhibits more modest but still positive gains (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests—Queue size.

The results show a typical pattern across all models: queue length increases progressively as simulation time advances, indicating a high-demand environment with accumulated congestion. The Fixed Time scheme maintains the longest queues throughout, peaking at 35 vehicles by the end, which evidences the poor performance of static control under heavy loads. The configuration proposed by GPT-5 achieves the best outcome, with queues between 10 and 18 vehicles during most of the run and an average of 16.91 vehicles, yielding an improvement of over 43% relative to Fixed Time. Gemini improves by roughly 30%, GPT-4o by 21%, and DeepSeek by 12.5% compared with the fixed-time baseline. LLM-based curves are lower and more stable, indicating more balanced signal phase management. GPT-5 exhibits the most uniform and contained trajectory, reflecting greater stability in traffic control, whereas Fixed Time and DeepSeek show wider fluctuations, indicating less suitable cycles for the studied intersection. Table 2 shows GPT-5, Gemini, and GPT-4o meet the target of keeping queues below 25 vehicles, with maxima of 19, 23, and 24, and averages of 13.52, 16.91, and 18.94 cars, respectively.

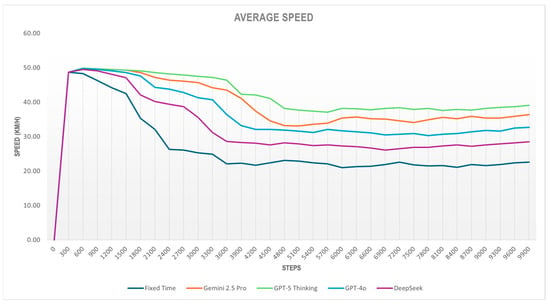

Figure 8 reports the speed metric, and Table 3 provides its statistical summary. As the simulation progresses, average speed declines markedly, consistent with the congestion captured by the queue size graph. Fixed Time shows the weakest performance: the mean speed drops by nearly 50%, down to 25.9 km/h.

Figure 8.

Comparative results for the average speed metric for each model.

DeepSeek outperforms Fixed Time; however, after the first quarter of the simulation, its speed drops quickly and remains within 27–29 km/h.

Gemini and GPT-4o exhibit solid performance, with mean speeds of 38.54 km/h and 35.43 km/h, respectively, exceeding Fixed Time and DeepSeek. GPT-5 consistently maintains the highest average speed, ranging 35–40 km/h even under high demand, improving by more than 57% relative to Fixed Time and showing a steadier curve during the second half of the run. This pattern suggests that a more suitable set of signal phase durations limits queue growth and yields better flow.

Table 4 and Table 5 show average speed by controller (n = 34 paired steps per controller). Values are means with 95% CIs. Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests versus Fixed Time follow immediately below.

Table 4.

Statistical summary for the Average speed metric.

Table 5.

Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests—Average speed.

Figure 9 shows the results for the average travel time metric, and Table 4 provides a statistical summary of this metric for each analyzed model.

Figure 9.

Comparative results of the analyzed models for the average travel time for each model.

Table 6 and Table 7 show the travel time by controller (n = 34 paired steps per controller). Values are means with 95% CIs. Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests versus Fixed Time follow immediately below.

Table 6.

Statistical summary of the results obtained for the Average speed metric for each model.

Table 7.

Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests—Travel time.

All models behave similarly at the beginning of the simulation; as time progresses, travel times rise due to cumulative congestion. Fixed Time records the highest values, peaking at 24–25 min with an average of 19.85 min. This outcome stems from inefficient signal control, extending intersection delay, lowering cruising speeds, and lengthening trips.

DeepSeek exhibits a marked increase in mean travel time from the second quarter onward, later stabilizing around 22 min. GPT-4o and Gemini remain in an intermediate band of 16–17 min, achieving 15% and 20% reductions relative to Fixed Time. GPT-5 sustains the lowest and most stable times through improved queue and speed management, achieving up to 25% reduction versus the fixed-time scheme. Figure 10 reports the Average CO2 metric results, and Table 5 provides its statistical summary.

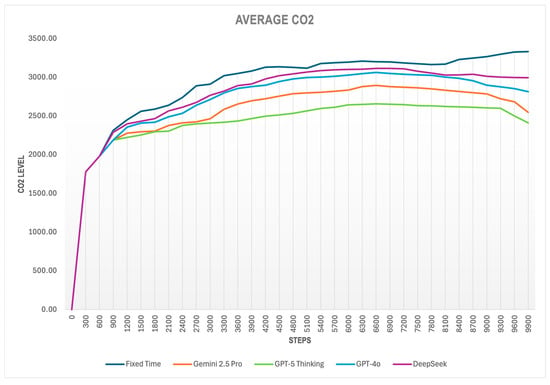

Figure 10.

Comparative results for the average CO2 emissions metric for each model.

Table 8 and Table 9 show CO2 emissions by controller (n = 34 paired steps per controller). Values are means with 95% CIs. Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests versus Fixed Time follow immediately below.

Table 8.

Statistical summary of the results for the CO2 metric for each model.

Table 9.

Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests—CO2 emissions.

The result indicates that all models behave similarly initially; as congestion builds up, CO2 levels rise rapidly. Fixed Time performs worst, sustaining the highest values for most of the experiment: an average of 2931 mg/s and peaks above 3300 mg/s. Gemini 2.5 Pro, DeepSeek V3, and GPT-4o follow comparable trajectories, with averages of 2588.52, 2802.47, and 2739.79 mg/s, respectively. GPT-5 performs best: it curbs the initial surge, stabilizes around 2600 mg/s, and trends downward toward the end. The configuration proposed by GPT-5 yields a CO2 reduction of up to 24% relative to Fixed Time; GPT-4o achieves about 7%, Gemini 2.5 Pro around 12%, and DeepSeek V3 4.4%.

Taken together, the results show a consistent performance hierarchy across all metrics. GPT-5 Thinking achieved the most significant and most stable improvements, followed by Gemini 2.5 Pro and GPT-4o, while DeepSeek V3 yielded smaller but still positive gains relative to the fixed-time baseline. This comparative pattern is preserved throughout the simulation, indicating that differences among the controllers are not only quantitative but also reflect variations in stability under high-demand conditions. Beyond quantitative performance, we analyzed selected outputs to understand how each model operationalizes symmetry-aware reasoning.

A qualitative inspection of LLM-generated outputs reveals different reasoning strategies behind phase-duration adjustments. For instance, GPT-5 tended to slightly increase green time for through movements on the main avenue while shortening yellow intervals, justifying these choices as a way to reduce stop-and-go patterns and maintain continuous flow, thereby improving both speed and emissions. Gemini 2.5 Pro focused more on rebalancing turn phases, often extending green time for minor approaches with high queue values, aligning with symmetry goals. GPT-4o showed moderate adjustments across all phases but occasionally lacked detailed justifications, suggesting a more conservative optimization style. DeepSeek V3 produced structurally valid outputs but with simpler logic (e.g., “reduce congestion by adding green time”), indicating a less nuanced understanding of trade-offs. These variations reflect how each model internalizes the objectives of balancing flow efficiency with sustainability, highlighting the role of generative reasoning in achieving symmetry-aware control.

5. Discussion

A joint analysis of Queue Size, Average Speed, Average Travel Time, and CO2 emissions provides an integrated view of signal control performance. There is a direct link between queue growth, speed loss, longer trips, and higher emissions. As queues build, seen with Fixed Time and, to a lesser extent, DeepSeek, average speeds decline and travel times increase; the stop-and-go pattern intensifies, which raises fuel use and emissions (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Comparative performance summary.

When the number of waiting vehicles is contained, as with GPT-5, flows improve, trips shorten, and driving becomes more regular, leading to lower fuel consumption and fewer emissions. The Fixed Time scheme is ill-suited to urban settings with variable demand due to its lack of adaptability. The evaluated LLMs (GPT-4o, GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and DeepSeek V3) form a viable alternative that outperforms static control with varying degrees of effectiveness.

GPT-5 sustains a more balanced corridor across all metrics, indicating stronger context understanding and phase adjustment. Such performance would translate into less congestion at critical intersections, time savings for drivers, and, through better flow, lower fuel consumption and emissions, with tangible benefits for users’ costs, public health, and progress toward sustainable mobility.

The paired step-level results indicate that adaptive, LLM-guided control policies substantially outperform a fixed timing plan on mobility (queues, speed, travel time) and sustainability (CO2). The magnitude and consistency of effects (very small, adjusted p-values, large |dz|) suggest the differences are statistically reliable and operationally meaningful for the simulated network.

Two considerations temper the interpretation. First, analyses are conducted on step-level pairs (n = 34), which may exhibit temporal autocorrelation; this can increase test power relative to analyses on aggregated runs. Second, results pertain to the specific network demand pattern and controller configurations studied here; generalization to other networks, demand profiles, and LLM configurations warrants confirmatory experiments. Future robustness checks could include block bootstrapping over time, aggregation at episode/run granularity, and replication across seeds, demand levels, and network topologies.

Practically, the improvements appear largest for GPT-5 Thinking and Gemini 2.5 Pro, which may reflect better responsiveness to evolving queues and spillbacks. Even the smallest gains (DeepSeek vs. Fixed Time) remain non-trivial regarding traffic operations, particularly the combined effect of shorter travel times and lower emissions.

Beyond numerical improvements, these findings suggest that generative reasoning can play a complementary role alongside existing reinforcement-learning and optimization-based approaches used in adaptive traffic control. Whereas RL and metaheuristic methods rely on iterative reward maximization and explicit objective functions, LLMs can rapidly interpret aggregated system states, articulate high-level trade-offs, and propose structurally coherent timing plans without requiring retraining. In real-world deployments, this capability could facilitate hybrid architectures in which generative models provide (i) initial timing plans that warm-start RL agents, (ii) interpretable explanations or constraints that guide optimization algorithms, and (iii) rapid adaptation during atypical or non-recurrent conditions where learned policies may underperform. Such integration may enhance flexibility, accelerate controller tuning, and reduce the reliance on extensive historical data, offering a promising direction for next-generation adaptive traffic management systems.

Compared with prior work, the symmetry-aware generative approach implemented with GPT-5 Thinking achieves competitive or superior performance. Masri et al. [55] presented an LLM-based controller designed to detect conflicts and generate contextual explanations in real-time at urban intersections. While their approach emphasizes interaction-level reasoning and compliance with priority rules, it does not report system-level performance metrics such as queue length or emissions. In contrast, our study focuses on how LLMs can infer intersection-level signal plans that co-optimize traffic flow and sustainability goals. This broader operational scope enables direct benchmarking of aggregate outcomes, such as queue reduction and CO2 improvements, under a unified optimization framework.

Compared to other recent AI-based approaches such as Moreno-Malo et al. [39], which applied a Deep Q-Network (DQN) in a 16-intersection Manhattan-style grid, our symmetry-aware LLM-based controller achieved comparable gains without reinforcement learning training. Specifically, while their system reduced average vehicle waiting time by 44.18%, our GPT-5-based controller achieved a similar ~44% reduction. However, our approach additionally integrates symmetry and environmental reasoning, leading to an observed ~24% CO2 reduction, compared to their ~68.6%. Although their emissions results are stronger, our framework operates with no training phase and achieves robust zero-shot reasoning, which may be advantageous in settings with limited real-time data or computer resources.

A key limitation of the study is the use of constant demand and fixed vehicle-speed parameters, which do not capture the variability, driver heterogeneity, or peak-period fluctuations present in real traffic systems. These assumptions were chosen to establish a controlled baseline for evaluating relative improvements among controllers, but future work should incorporate calibrated demand profiles, empirical speed distributions, and stochastic arrival patterns to assess robustness under more realistic conditions. Nevertheless, the use of LLMs in operational traffic control remains constrained by issues such as inference latency, sensitivity to prompt structure, and the need for safety guarantees, which will require careful integration with established RL or optimization mechanisms in future real-world deployments.

Additionally, while the simulation-based design enabled controlled and reproducible testing across models, the results are inherently dependent on modeled assumptions. Real-world validation (whether through hybrid simulation–field calibration, digital twins, or deployment in testbed intersections) would further strengthen confidence in the framework’s practical applicability. Future work should explore such integration to assess how generative reasoning performs under real-time traffic fluctuations, sensor noise, and infrastructure constraints.

A further limitation is that, in the current study, LLMs were not directly integrated with SUMO through an automated interface. Instead, the interaction occurred through conversational interfaces, from which generated timing plans were extracted, validated, and manually incorporated into the simulation pipeline. Although this workflow enabled a controlled evaluation of generative reasoning, it does not represent a real-time closed-loop system. Fully operational deployments would require automated data exchange, deterministic latency, robust validation mechanisms, and safety constraints to ensure that timing plans generated by an LLM are reliable before being executed in live traffic environments.

These findings illustrate a symmetry between operational efficiency and sustainability, where generative AI enables balanced optimization without sacrificing environmental goals. Because the simulation parameters were based on realistic intersection dynamics, the proposed approach can generalize to other mid-sized cities after local calibration.

6. Conclusions

Across a common demand scenario, LLM-based signal controllers delivered sizable and statistically robust gains over a Fixed Time baseline, simultaneously improving throughput (higher speeds), efficiency (lower queues and travel times), and sustainability (lower CO2). Among tested policies, GPT-5 Thinking offered the strongest overall performance, with Gemini 2.5 Pro and GPT-4o close behind, and DeepSeek still outperforming Fixed Time.

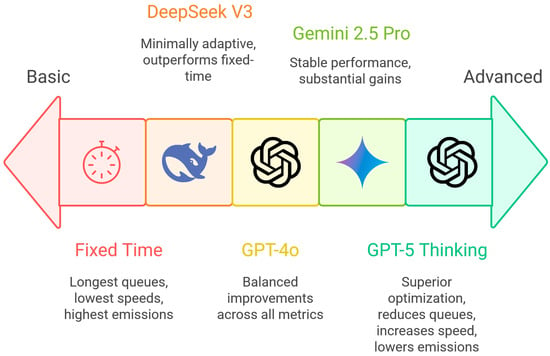

Overall, the findings demonstrate that generative AI can serve as an effective decision-support mechanism for urban traffic management, autonomously generating control strategies that balance competing objectives of mobility and sustainability. By integrating large language models into the signal optimization process, this study provides empirical evidence that such models can simultaneously internalize complex trade-offs, reducing congestion and emissions. The visual summary in Figure 11 illustrates this progression, showing how controller performance transitions from basic, fixed-time schemes to highly adaptive, symmetry-aware LLMs such as GPT-5. The results confirm the feasibility of symmetry-aware traffic control and underscore the potential of generative reasoning to inform broader smart city applications where operational efficiency and environmental responsibility must coexist.

Figure 11.

Comparative spectrum of controller performance, ranging from baseline Fixed Time to advanced LLM-based controllers. The diagram illustrates the progression in traffic performance and environmental gains, highlighting how GPT-5 achieves the most balanced and consistent improvements across all metrics.

Beyond these experimental results, this work consolidates a reproducible symmetry-aware generative optimization framework that unites deterministic simulation and large-scale generative reasoning within a single adaptive loop. The integration of SUMO with multiple LLMs demonstrates that generative models can internalize complex trade-offs between traffic efficiency and sustainability without explicit multi-objective programming. Beyond its immediate findings, the framework offers a scalable methodological foundation for future research on intelligent transportation, where generative AI can serve as a high-level reasoning layer for simulation-driven decision making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sym17122083/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.S.-M. and A.G.-I.; methodology, L.A.-R. and P.C.S.-M.; validation, A.G.-I., P.C.S.-M. and L.A.-R.; formal analysis, A.G.-I. and J.C.-C.; investigation, J.G.-M. and J.C.-C.; data curation, J.G.-M. and J.C.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.S.-M. and A.G.-I.; writing—review and editing, L.A.-R., J.C.-C. and J.G.-M.; visualization, A.G.-I. and J.G.-M.; supervision, L.A.-R. and P.C.S.-M.; project administration, P.C.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT-4o, ChatGPT-5, Google Gemini 2.5 Pro, and DeepSeek V3 for simulation-based reasoning, and Claude Sonnet 4.5 for code generation; all outputs were verified and edited by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jesús García-Mancilla is affiliated with the Department of AI & Digital Solutions at Argomai. This affiliation did not influence the design, execution, or interpretation of the study. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, H.K. The Environmental Benefits of an Automatic Idling Control System of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzoug, R.; Lakouari, N.; Pérez Cruz, J.R.; Vega Gómez, C.J. Cellular Automata Model for Analysis and Optimization of Traffic Emission at Signalized Intersection. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, Y.; Al-refai, M.; Al-refai, G.; Darweesh, D.A.-K.; Zaghal, N.; Darwish, O. Dynamic Traffic Light System to Reduce the Waiting Time of Emergency Vehicles at Intersections within IoT Environment. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2022, 17, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.K. Investigation of Environmental Benefits of Traffic Signal Countdown Timers. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabaci, E.; Orman, R.Ç.; Kiliç, B.; Hepdeniz, K.; Yitik, B. Environmental Impact of Vehicles Waiting at the Signalized Intersections: A Case Study of a Four-Phase Intersection. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Üniversitesi Uygulamalı Bilim. Derg. 2019, 3, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górka, A.; Czerepicki, A.; Krukowicz, T. The Impact of Priority in Coordinated Traffic Lights on Tram Energy Consumption. Energies 2024, 17, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Kumar, P.P.; Dhyani, R.; Ravisekhar, C.; Ravinder, K. Idling Fuel Consumption and Emissions of Air Pollutants at Selected Signalized Intersections in Delhi. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.; Parida, P.; Singh, P. Estimation of Carbon Footprint of Fuel Loss Due to Idling of Vehicles at Signalised Intersection in Delhi. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 104, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzio, E.; Drożdż, W.; Kolon, M. The Role of Intelligent Transport Systems and Smart Technologies in Urban Traffic Management in Polish Smart Cities. Energies 2025, 18, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraj, R.K.; Kamila, N.K.; Pani, S.K.; Balusamy, B.; Rajasekar, V. Artificial Intelligence for Future Intelligent Transportation: Smarter and Greener Infrastructure Design, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-40846-8. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, C.T.; Pham, D.D.; Nguyen, P.M.; Tran, H.V. Green Wave-Based Solution for Intelligent Traffic Lights System Control in Vietnam Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Green Technology and Sustainable Development (GTSD), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 23–24 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Oskarbski, J.; Zawisza, M.; Miszewski, M. Information System for Drivers Within the Integrated Traffic Management System—TRISTAR. In Tools of Transport Telematics; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 531, pp. 131–140. ISBN 978-3-319-24576-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi, Z.; Nowaczyk, S. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Connected Vehicles for Traffic Flow Optimization. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2574–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madireddy, M.; De Coensel, B.; Can, A.; Degraeuwe, B.; Beusen, B.; De Vlieger, I.; Botteldooren, D. Assessment of the Impact of Speed Limit Reduction and Traffic Signal Coordination on Vehicle Emissions Using an Integrated Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Signal Coordination on Traffic Emission. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2012, 17, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-X.; He, R.-C.; Yin, N. Modeling of Vehicle CO2 Emissions and Signal Timing Analysis at a Signalized Intersection Considering Fuel Vehicles and Electric Vehicles. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Castillo, J.; Guerrero-Ibañez, J.; Zeadally, S.; Hong, E.-K. Generative AI for Internet of Vehicles (IoV): Potential and Challenges. IEEE Comm. Stand. Mag. 2025, 9, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello Coello, C.A.; Christiansen, A.D. Moses: A Multiobjective Optimization Tool for Engineering Design. Eng. Optim. 1999, 31, 337–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučera, T.; Chocholáč, J. Design of the City Logistics Simulation Model Using PTV VISSIM Software. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 53, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajzewicz, D. Traffic Simulation with SUMO—Simulation of Urban Mobility. In Fundamentals of Traffic Simulation; Barceló, J., Ed.; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 145, pp. 269–293. ISBN 978-1-4419-6141-9. [Google Scholar]

- Delorme, A.; Karbowski, D.; Sharer, P. Evaluation of Fuel Consumption Potential of Medium and Heavy Duty Vehicles Through Modeling and Simulation; SciTech Connect: Godalming, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, V.T.; Moezzi, R.; Cyrus, J.; Hlava, J. Optimal Fuel Consumption Modelling, Simulation, and Analysis for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Hayes, J.G. Analysis of Electric Vehicle Powertrain Simulators for Fuel Consumption Calculations. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical Systems for Aircraft, Railway, Ship Propulsion and Road Vehicles & International Transportation Electrification Conference (ESARS-ITEC), Toulouse, France, 2–4 November 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, P.; Kjeang, E. Realistic Simulation of Fuel Economy and Life Cycle Metrics for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles: Realistic Simulation of Fuel Economy and Life Cycle Metrics for FCVs. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hodgson, J.W. Modeling and Simulation for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. I. Modeling. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2002, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Velasco, H.E.; Pérez Torres, C.A. Analysis of the Impact of Globalization on Urban Mobility in the State of Colima, Mexico. Int. J. Res. Manag. Econ. Commer. 2018, 8, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Currano, R.; Park, S.Y.; Domingo, L.; Garcia-Mancilla, J.; Santana-Mancilla, P.C.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Ju, W. ¡Vamos!: Observations of Pedestrian Interactions with Driverless Cars in Mexico. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Toronto, ON, Canada, 23–25 September 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Noaeen, M.; Naik, A.; Goodman, L.; Crebo, J.; Abrar, T.; Abad, Z.S.H.; Bazzan, A.L.C.; Far, B. Reinforcement Learning in Urban Network Traffic Signal Control: A Systematic Literature Review. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2022, 199, 116830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y. MalLight: Influence-Aware Coordinated Traffic Signal Control for Traffic Signal Malfunctions. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2879–2889. [Google Scholar]

- Neelakandan, S.; Berlin, M.A.; Tripathi, S.; Devi, V.B.; Bhardwaj, I.; Arulkumar, N. IoT-Based Traffic Prediction and Traffic Signal Control System for Smart City. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 12241–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ei Leen, M.W.; Jafry, N.H.A.; Salleh, N.M.; Hwang, H.; Jalil, N.A. Mitigating Traffic Congestion in Smart and Sustainable Cities Using Machine Learning: A Review. In Computational Science and Its Applications, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2023—23rd International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Braga, A.C., Garau, C., Stratigea, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 13957, pp. 321–331, ISBN 978-3-031-36807-3. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, H.; Ghadirifaraz, B.; Shetab Boushehri, S.N.; Hosseininasab, S.-M.; Rafiei, N. Reducing Traffic Congestion and Increasing Sustainability in Special Urban Areas through One-Way Traffic Reconfiguration. Transportation 2022, 49, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ibarra, M.; Saldaña-Perez, M.; Pérez Rodríguez, S.; Juárez Carbajal, E. Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Context of Urban Spaces. In Telematics and Computing; Mata-Rivera, M.F., Zagal-Flores, R., Barria-Huidobro, C., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2249, pp. 209–222. ISBN 978-3-031-77289-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, A.; Xu, G.; Li, W.; Ban, X.; Ye, X. GenAI-Powered Multi-Agent Paradigm for Smart Urban Mobility: Opportunities and Challenges for Integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) with Intelligent Transportation Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00494. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Omitaomu, F.; Sabri, S.; Zlatanova, S.; Li, X.; Song, Y. Leveraging Generative AI for Urban Digital Twins: A Scoping Review on the Autonomous Generation of Urban Data, Scenarios, Designs, and 3D City Models for Smart City Advancement. Urban Inform. 2024, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, T.; Dawson, P.; Liu, D. Talk Is Cheap: Why Structural Assessment Changes Are Needed for a Time of GenAI. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2025, 50, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, K.; Tamás, T.; Tamás, B. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Approach for Traffic Signal Control. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, N.; Harada, T.; Miyazaki, K. Traffic Signal Control System Using Deep Reinforcement Learning with Emphasis on Reinforcing Successful Experiences. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128943–128950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Malo, J.; Posadas-Yagüe, J.-L.; Cano, J.C.; Calafate, C.T.; Conejero, J.A.; Poza-Lujan, J.-L. Improving Traffic Light Systems Using Deep Q-Networks. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Wu, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhong, L.; Chen, X.; Yin, R. A Scalable Approach to Optimize Traffic Signal Control with Federated Reinforcement Learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Jia, N. A Deep Learning Based Multitask Model for Network-Wide Traffic Speed Prediction. Neurocomputing 2020, 396, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Rahman, H.; Arshad, M.A.; Nabeel, M.; Yasin, A.; Al-Adhaileh, M.H.; Eldin, E.T.; Ghamry, N.A. Augmentation of Deep Learning Models for Multistep Traffic Speed Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Ke, R.; Pu, Z.; Wang, Y. Deep Bidirectional and Unidirectional LSTM Recurrent Neural Network for Network-Wide Traffic Speed Prediction. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1801.02143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, R.; He, Z. Traffic Speed Prediction for Urban Transportation Network: A Path Based Deep Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 100, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.A.; Awasthi, A. Intelligent Meta-Heuristic-Based Optimization of Traffic Light Timing Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Electronics 2023, 12, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Qiao, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, J. Traffic Signal Timing Optimization Model Based on Video Surveillance Data and Snake Optimization Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Tong, Y.; Long, Y. Advancements in the Application of Large Language Models in Urban Studies: A Systematic Review. Cities 2025, 165, 106142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, J.; Yin, Y. LLM-ABM for Transportation: Assessing the Potential of LLM Agents in System Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22718. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Yang, J.; Yin, Y. Toward LLM-Agent-Based Modeling of Transportation Systems: A Conceptual Framework. Artif. Intell. Transp. 2025, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ma, J. Large Language Model as Parking Planning Agent in the Context of Mixed Period of Autonomous Vehicles and Human-Driven Vehicles. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 117, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, H.; Titidezh, O.; Asgary, A.; Bonakdari, H. Building Resilient Smart Cities: The Role of Digital Twins and Generative AI in Disaster Management Strategy. In Digital Twin Computing for Urban Intelligence; Pourroostaei Ardakani, S., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Urban Sustainability; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 95–118. ISBN 978-981-97-8482-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Bibri, S.E.; Keel, P. Generative Spatial Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Smart Cities: A Pioneering Large Flow Model for Urban Digital Twin. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2025, 24, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, A.; Zhou, J.; Du, Y.; Deng, Q.; Liu, L. Generative AI for the Internet of Vehicles: A Review of Advances in Training, Decision-Making, and Security. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, N.; AlJassmi, H.; Ali, L.; Masoud, A.R. Applications of Large Language Models and Generative AI in Transportation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 34, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.; Ashqar, H.I.; Elhenawy, M. Large Language Models (LLMs) as Traffic Control Systems at Urban Intersections: A New Paradigm. Vehicles 2025, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Niyato, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Mao, S.; Han, Z. Generative AI-Empowered Simulation for Autonomous Driving in Vehicular Mixed Reality Metaverses. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.08418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Lambert, J.; Jeon, H.; Kulshrestha, S.; Bai, Y.; Luo, J.; Anguelov, D.; Tan, M.; Jiang, C.M. SceneDiffuser++: City-Scale Traffic Simulation via a Generative World Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.21976. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco Di Torrepadula, F.; Russo, D.; Di Martino, S.; Mazzocca, N.; Sannino, P. Using SUMO towards Proactive Public Mobility: Some Lessons Learned. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Sustainable Mobility, Hamburg, Germany, 13 November 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]