Abstract

Real-world systems frequently exhibit hierarchical multipartite graph structures, yet existing graph neural network (GNN) approaches lack systematic frameworks for hyperparameter optimization in heterogeneous multi-level architectures, limiting their practical applicability. This study proposes a Bayesian optimization framework specifically designed for heterogeneous GNNs operating on three-level graph structures, addressing the computational challenges of configuring partition-aware architecture. Four GNN architectures—Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), Graph Attention Networks (GATs), Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs), and GraphSAGE—were systematically evaluated using Gaussian Process-based Bayesian hyperparameter optimization with inter-partition message-passing mechanisms. The framework was validated on the TIMSS 2023 dataset (10,000 students, 789 schools, 25 countries), demonstrating that Bayesian-optimized GraphSAGE achieved the highest explained variance (R2 = 0.6187, RMSE = 71.73, MAE = 64.32) compared to seven baseline methods. Bayesian optimization substantially improved model performance, revealing that two-layer architectures optimally capture cross-partition dependencies in three-level structures. GNNExplainer was used to identify the most influential student-level features learned by the model, providing explanatory insight into how the model represents individual characteristics. The optimization framework is broadly applicable to other heterogeneous and multi-level graph settings; however, the empirical findings, such as the optimal architecture depth, are specific to hierarchical graphs with structural properties like the TIMSS topology.

1. Introduction

Graph theory provides a fundamental framework for the mathematical modeling of discrete structures representing entities and their relationships. Graph G = (V, E) consists of a set of nodes V and a set of edges E, which represent binary relationships between the nodes. Traditional graph theory studies have primarily focused on homogeneous graphs, where all nodes and edges are of the same type [1]. However, many real-world problems require heterogeneous graph structures, that is, systems containing multiple node types and differentiated edge relationships. Heterogeneous graphs, also known as multi-relational or typed graphs, extend the classical definition of a graph by assigning type information to nodes and edges [2]. In these structures, each node and edge belongs to a predefined set of types and is associated with type-matching functions. The combinatorial properties of heterogeneous graphs, such as chromatic number, independence count, cross-partition matching, connectedness, and graph parameters, are fundamentally different from those of homogeneous graphs [3]. K-partite heterogeneous graphs exhibit a special structure in which the node set is partitioned into disjoint sets, with edges connecting only nodes across these sets [4]. Such graphs can be used to naturally model social networks, knowledge graphs, and multi-level hierarchical organizations (such as student–school–country or patient–hospital–region). While similar multi-level structures appear in diverse fields, including healthcare and organizational analysis, our empirical findings should not be interpreted as directly transferable to domains whose graph topologies differ fundamentally from the sparse, low-diameter tripartite structure examined in this study. The methodological framework remains broadly applicable, but architectural conclusions are topology dependent. For example, recent work on g-good-neighbor diagnosability in multiprocessor networks highlights how fault propagation patterns depend on hierarchical graph topology [5,6]. Hierarchical stochastic network models have also been proposed to assess fault behavior in multi-level industrial processes [7].

Analyzing heterogeneous graph structures gives rise to various combinatorial optimization problems. For example, problems such as node attribute prediction in multi-level structures, heterogeneous neighborhood aggregation, and modeling inter-partition information flow are too complex to be addressed by classical graph algorithms. These problems require significant computational resources, especially in large-scale graph structures, and even sub-problems such as hyperparameter selection can be inefficient without systematic optimization strategies. Therefore, developing computationally efficient algorithms for heterogeneous graph structures is an important area of research in graph theory. However, despite growing interest in graph-based learning, the integration of optimization strategies with heterogeneous and multi-level graph representations remains largely unexplored. This represents a critical methodological gap that this study seeks to address.

In recent years, the integration of graph theory with computational methods has marked the beginning of a new era in theoretical and applied research. Graph machine learning (GML) focuses on developing and applying computational algorithms based on graph structures. Unlike classical tabular data methods, this field exploits the combinatorial properties of graphs to uncover hidden structural patterns by modeling the relational dependencies between nodes. Graph neural networks (GNNs) have become one of the most important tools in graph-based computational methods. Based on message passing and state updating mechanisms, GNNs model the flow of information between nodes [8]. These mechanisms enable each node to update its representation by integrating information from neighboring nodes, as well as its own features. This facilitates learning at the node, edge, and graph levels. From a graph theory perspective, GNNs can be viewed as recursive functions defined on the graph. Architectural choices, such as neighborhood aggregation strategies and the number of message-passing layers, influence the model’s ability to capture structural properties. For instance, the number of layers determines the receptive field size (K-hop neighborhood), and different aggregator functions (e.g., mean, maximum, or attention-based) may respond differently to varying degree distributions. In heterogeneous, multi-level graphs, these architectural decisions are particularly critical, as information must propagate across partitions with distinct structural characteristics. Various GNN architectures have been developed in the literature, each with distinct theoretical foundations and computational characteristics. The Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) aggregates neighbor information via spectral-based convolution filters, leveraging the spectral properties of the graph Laplacian matrix [9]. The Graph Attention Network (GAT) employs an attention mechanism to dynamically assign importance weights to neighboring nodes, enabling adaptive aggregation based on learned attention coefficients [10]. The Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) achieves high expressive power by implementing aggregation functions equivalent to the Weisfeiler–Lehman graph isomorphism test. This enables the model to distinguish between diverse graph structures [11]. GraphSAGE addresses the challenge of scalability in large-scale graphs by sampling neighborhoods, thus enabling inductive learning on previously unseen nodes [12]. Theoretically, these architectures can be extended to heterogeneous, multi-level graphs by incorporating type-specific parameters for different nodes and edges. However, optimizing these models—including hyperparameters such as embedding dimensions, learning rates, and the number of message-passing layers—remains problem-dependent and requires systematic optimization strategies. Despite the theoretical extensibility of GNN architectures to heterogeneous settings, most existing studies have focused on homogeneous, single-level graphs. Systematic investigations of the performance of heterogeneous GNNs on multi-level relational structures are scarce, as is the integration of such GNNs with principled hyperparameter optimization frameworks, such as Bayesian optimization. Multi-level heterogeneous graphs introduce substantial combinatorial complexity due to differentiated node types, asymmetric inter-partition connections, and partition-specific structural properties. Such structures are prevalent in education (student–school–country), healthcare (patient–hospital–region), and the social sciences, where relationships inherently span multiple hierarchical levels. Consequently, the development of Bayesian-optimized heterogeneous GNN frameworks for multi-level data represents a significant gap in both graph theory and computational methods. Recent years have witnessed the development of several heterogeneous GNN architectures. Zhang et al. [13] developed the HetGNN model to learn node representations in heterogeneous graphs, and encoded content interactions by sampling heterogeneous neighbors. Yang et al. [14] proposed the SeHGNN model to simplify overly complex attention mechanisms and provided wider neighborhood interactions by using long meta paths. Zhu et al. [15] presented the RSHN model to jointly learn node and edge representations in heterogeneous graphs and captured edge relationships with a coarsened line graph approach. In addition to these developments, Zhu et al. [16] introduced a high-order topology-enhanced graph convolutional network that incorporates multiscale structural information to improve representation learning on dynamic graphs. Their formulation demonstrates how higher-order and multi-level topological dependencies can be leveraged to strengthen message passing, providing insights relevant to graph partitioning and multiscale graph theory. The performance of computational methods on heterogeneous graph structures is highly sensitive to hyperparameter selection. Parameters such as the learning rate, the number of layers, the embedding dimension, and the aggregator type can have a direct impact on the model’s generalizability. Classical grid-search or random search methods are computationally inefficient in high-dimensional parameter spaces. Bayesian optimization offers a systematic solution to this problem based on probabilistic modeling. Acquisition function-based approaches (e.g., Expected Improvement and Upper Confidence Bound) enable convergence to optimal parameters with a limited number of trials [17,18]. Although this method is widely used in machine learning literature, it has rarely been applied to graph-based computational problems, particularly multi-level heterogeneous graph structures. This study aims to investigate the theoretical properties of heterogeneous, multilevel graph structures, and to develop computational algorithms supported by Bayesian optimization on these structures. The TIMSS 2023 eighth-grade mathematics dataset was selected as a case study because it naturally represents a three-partite heterogeneous graph consisting of student, school, and country levels. While only a limited number of studies have combined Bayesian optimization methods with GNN architectures [16,19], these works have predominantly focused on engineering and bioinformatics applications rather than on multi-level or educational data modeling. The multilevel hierarchical structure inherent in the educational data (e.g., students, schools, countries) reveals unique combinatorial properties when considered from the perspective of heterogeneous graph theory. In particular, the modeling of information flow between partitions in a three-partite graph structure, and its sensitivity to hyperparameter selection, has not been systematically investigated in the literature. Accordingly, the methodological contributions of this study focus on the following: theoretical formulation of a three-partition graph structure consisting of student, school, and country levels, analyzing the edge structures and graph parameters across partitions; systematic comparison of GraphSAGE, GCN, GAT, and GIN architectures on heterogeneous structures and examining the performance characteristics of each with respect to structural features; application of acquisition function-based Bayesian optimization to the hyperparameter search problem of graph-based computational algorithms and demonstration of its effectiveness compared to classical methods. This integrated approach provides a methodological framework for the theoretical modeling of heterogeneous multilevel graph structures, the design of computational algorithms on these structures, and the integration of Bayesian optimization methods to graph problems. The educational data serves as a concrete example to demonstrate the applicability of this framework. This integration bridges the theoretical foundations of heterogeneous graph theory with probabilistic optimization, establishing a unified framework for multi-level relational modeling.

2. Methodology

2.1. Heterogeneous Graph Framework

Traditional graph neural networks (GNNs) are designed for homogeneous graphs, which have identical node and edge types. However, many real-world relational systems naturally take the form of heterogeneous graphs comprising multiple types of entities and interactions. Heterogeneous graphs facilitate the modeling and learning of complex, multi-level relationships within such systems [20,21]. These structures are expressed mathematically as follows:

Here, V represents the set of nodes and E represents the set of edges. is the node type mapping function, and represents the edge type mapping function [22].

A special case of heterogeneous graphs is the k-partite graph, where the node set is partitioned into k disjoint subsets and edges only connect nodes from different partitions. Formally, a k-partite heterogeneous graph satisfies:

where for all

This structure enforces that no edges exist within the same partition (intra-partition edges), ensuring a clear separation between different entity types. In hierarchical systems, such as educational data with student–school–country relationships, a tripartite structure (k = 3) with sequential connectivity naturally represents multi-level dependencies. This formalization provides the theoretical foundation for modeling hierarchical relationships in real-world applications. The structural properties of k-partite heterogeneous graphs, such as degree distribution, graph diameter, clustering coefficient, and connectedness, determine the efficiency of information flow and directly affect the performance and generalization ability of algorithms defined on these structures [3,4].

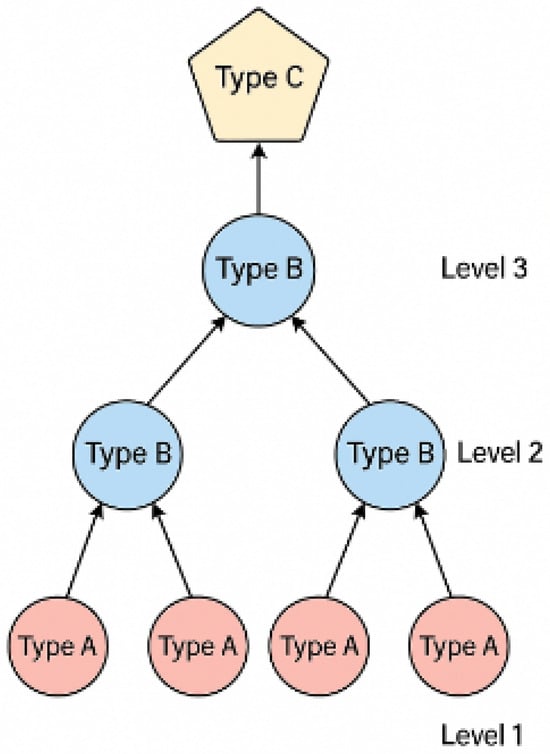

Figure 1 illustrates a generic schematic representation of a heterogeneous multi-level graph, where nodes belong to different types and are organized across hierarchical levels. In these structures, each node type (e.g., Type A, Type B, Type C) occupies a distinct partition, and edges appear only between nodes from adjacent levels, reflecting the layered multi-partite organization. Such graphs support representation learning by enabling message passing across node types, where each level contributes complementary structural or contextual information to the others. This provides a flexible and expressive framework for modeling systems in which interactions are inherently multi-level and type dependent [23]. The diagram is intended to convey the hierarchical nature of these relationships rather than specify a particular domain or direction of information flow.

Figure 1.

General structure of a heterogeneous multi-level graph.

2.2. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks

Learning on heterogeneous graphs requires GNN architectures that can propagate and integrate information across multiple node and edge types. To provide a unified perspective on how information flows within such structures, we adopt a general heterogeneous message-passing framework that encompasses all architectures used in this study. The general update rule for a node at layer is defined as:

where denotes the relation-specific neighborhood of node . The function determines how information is transmitted from a neighbor to under relation type , whereas specifies how these incoming messages are integrated with the current node representation. This formulation provides a unified template for understanding message passing on heterogeneous graphs [20,21].

Different GNN architectures instantiate this template using distinct MESSAGE and COMBINE operators. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), Graph Attention Networks (GATs), Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs), and GraphSAGE represent four widely used variants, each offering different mechanisms for information propagation and representation learning. The following subsections describe how each architecture is adapted to heterogeneous graph structures.

2.2.1. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are one of the most fundamental structures among graph-based learning models and are based on the principle of layered convolution to generate meaningful representations (embeddings) from the relationships between nodes. Each node updates its representation by combining its own features as well as information from neighboring nodes under specific weights [9]. Although the GCN model was originally developed for homogeneous graphs, the types of nodes and relationships often vary in complex data structures. Consequently, the model has been adapted for use with heterogeneous data structures and expanded to incorporate separate transformation matrices () for each relationship type. This enables information to flow in different directions depending on the relationship type, allowing the model to learn multi-level dependencies between node types jointly.

This adaptation is based on the relational graph convolutional network (R-GCN) formulation developed by Schlichtkrull et al. [20]. In the heterogeneous GCN structure, information transfer is defined for each relationship type separately, and the model can be expressed as follows:

Here, R denotes the set of relation (edge) types in the heterogeneous graph.

denotes the relation-specific neighborhood of node ; is the normalization constant for relation , (e.g., ); is the embedding of node at layer . Each relation-specific transformation matrix satisfies ; is the self-loop transformation matrix and is the activation function.

2.2.2. Graph Attention Networks (GAT)

A Graph Attention Networks (GATs) is a model that uses an attention mechanism to implement information propagation in graph-based learning methods. Rather than assuming equal influence from each neighbor when transferring information between nodes, this structure determines the effect of learnable weights based on relationship type and context [10]. The classical GAT model, which was developed for homogeneous graphs, has a single type of node and edge. In heterogeneous structures, where nodes and relationships have multiple types, separate attention coefficients and transformation matrices are defined for each relationship type (), a separate transformation matrix and attention vector are learned. The unnormalized attention coefficient between node and its neighbor under relation type is computed as:

where is the relation-specific transformation matrix; is the learnable attention vector for relation ; denotes vector concatenation. The normalized attention weights are obtained via a softmax over the relation-specific neighborhood:

The node update for heterogeneous GAT is then defined as:

Here, , denotes the activation function. This formulation directs the flow of information between nodes in a relationship-type-specific manner and enables the model to learn interactions at different levels in a context-aware manner.

2.2.3. Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN)

Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) are among the graph neural network (GNN) models with the strongest discriminative capabilities. When updating node representations, the GIN model processes the node’s own properties and information from its neighbors using a multi-layer perception (MLP). This approach is rooted in graph isomorphism theory and ensures graph discriminability across various structures [14]. The classical GIN model, which was developed for homogeneous graphs, assumes that all node and edge types are identical. However, in heterogeneous data structures, node and relationship types represent different layers of meaning. Therefore, the model is adapted to the heterogeneous environment by defining separate transformation matrices for each relationship type () [24]. The heterogeneous GIN update is given by:

Here, R denotes the set of relation types in the heterogeneous graph denotes the relation-specific neighborhood of node ; is the learnable transformation matrix associated with relation type ; denotes the embedding of node at layer ; is the learnable self-loop coefficient, is the embedding of neighbor node at layer ; is the learnable self-loop coefficient, and denotes the layer-specific multilayer perceptron applied to the aggregated message. Combining these two components enables heterogeneous GIN to learn about the interactions between nodes in a relationship-aware manner, capturing structural differences more robustly.

2.2.4. GrapSAGE

GraphSAGE is one of the most widely used sampling and embedding-based methods within the graph neural network (GNN) family. The model uses information directly from neighbors to update node representations and summarizes this information via a learnable aggregation function [12]. This enables GraphSAGE to generate embeddings for both existing and new nodes that were not previously present in the graph structure. In homogeneous graphs, GraphSAGE assumes uniform node and edge types. However, as with other graph models, in heterogeneous data structures the node and relationship types differ, so separate aggregation functions and transformation matrices are defined for each relationship type (r ∈ R) [23]. This enables information to flow in different directions depending on the relationship type and allows the model to learn multi-level interactions more flexibly. The heterogeneous GraphSAGE update for node at layer is defined as:

Here, is the representation of node at layer (with ), and denotes the relation-specific neigborhood of node for edge type . The operator denotes a permutation-invariant aggregation function that maps a multiset of vectors in to a single vector in . Relation-specific transformation matrices are defined as , and the output transformation matrix is . When a mean aggregator is used, the normalization constant for edge type is , and this normalization is absorbed into . Finally, denotes the activation function.

In this formulation, the model processes neighborhood information from each relationship type via relationship-specific transformations, combining this information using a learnable aggregation mechanism. Consequently, the flow of information between nodes is sensitive to both structural connections and the contextual effects of relationship types. Heterogeneous GraphSAGE architecture improves the ability to represent multi-level data structures by adapting the way sampling and aggregation operations are carried out for different node and edge types.

2.3. Baseline Models

2.3.1. Linear Regression

Linear regression estimates the linear relationship between dependent and independent variables using ordinary least squares [25]. The method minimizes the sum of squared errors between observed and predicted values, providing interpretability and computational efficiency. In educational research, it serves as a baseline model for large-scale datasets such as TIMSS, though violations of linearity assumptions or multicollinearity may require regularization methods.

2.3.2. Ridge Regression

Ridge regression is a regularization method developed to reduce the problem of multicollinearity in linear regression models. In this method, an L2 regularization term is added to the least squares function to reduce the variance of coefficient estimates [26]. In educational research, ridge regression provides reliable results, particularly in large-scale datasets with numerous independent variables and high correlations between these variables [27]. However, if the penalty coefficient (λ) is not selected appropriately, the model’s bias may increase, and its interpretability may decrease.

2.3.3. Random Forest Regression

Random Forest Regression is an ensemble learning method that creates multiple decision trees using bootstrap samples and aggregates their predictions [28]. By evaluating random subsets of variables at each node, it reduces variance and prevents overfitting. Its robust performance on high-dimensional datasets makes it widely used in educational research.

2.3.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a tree-based ensemble learning algorithm that builds decision trees sequentially, where each tree attempts to correct the residual errors of the previous ones [29]. The model incorporates regularization terms in its objective function to prevent overfitting and employs an efficient gradient boosting optimization strategy for enhanced accuracy. XGBoost can natively handle missing values, efficiently parallelize computations, and provide high predictive performance on complex and large-scale datasets, making it widely adapted for regression and predictive modeling tasks.

2.3.5. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Support Vector Regression (SVR) extends support vector machines to regression tasks using ε-insensitive loss functions that ignore errors within a specified tolerance [30]. Kernel functions enable modeling of non-linear relationships, making SVR suitable for complex data structures. Its resilience to overfitting is particularly valuable for high-dimensional educational data.

2.3.6. CatBoost

CatBoost is a gradient-boosted decision tree algorithm that particularly excels in handling categorical variables. Unlike other boosting algorithms, it can process categorical variables directly without the need for preprocessing, such as dummy coding [31]. Furthermore, its symmetric tree structure and regularization techniques ensure computational efficiency and resilience against overfitting.

2.3.7. LightGBM

LightGBM uses histogram-based splitting and leaf-wise tree growth for fast, memory-efficient gradient boosting [32]. Unlike level-wise approaches, it grows trees by selecting leaves with maximum loss reduction, achieving high accuracy with fewer iterations. Its computational efficiency enables effective handling of large-scale datasets.

2.4. Hyperparameter Optimization

In Graph Neural Network (GNN) models, hyperparameters such as the learning rate, embedding size, dropout rate, number of layers, neighborhood sampling rate and activation function are critical components that directly impact the model’s ability to generalize and its predictive performance, as also shown in recent GNN-based student performance prediction research [33]. In heterogeneous multi-level graph structures, the hyperparameter space becomes particularly complex due to the interaction between graph topology, node type distributions, and message-passing depth.

In this study, the hyperparameters of heterogeneous GNN models (GCN, GAT, GIN and GraphSAGE) were determined using the Bayesian optimization (BO) method. BO is a probabilistic approach used to optimize objective functions that are computationally expensive and cannot be derived analytically [17,34]. The objective is to identify the combination of hyperparameters that minimizes the error value (e.g., root mean square error—RMSE) in the model’s validation set. In this context, the objective function is defined as follows [18]:

Here, x is the hyperparameter vector and is the error value on the validation set. The goal of the optimization process is to minimize this function:

Rather than evaluating the target function directly, Bayesian optimization uses a Gaussian process (GP) to model it probabilistically [35]. The GP model estimates the distribution of the target function based on previously observed data points.

Here, represents the mean function and represents the covariance function. An acquisition function is then used to select the next point to evaluate. In this study, the Expected Improvement (EI) criterion was used due to its effectiveness in balancing exploration and exploitation. Under the Gaussian surrogate model, EI admits the following closed-form expression [35]:

where is the lowest RMSE observed so far, and and are the posterior mean and standard deviation of the surrogate model at point and denote the cumulative distribution function and probability density function of the standard normal distribution, respectively.

The EI criterion guides the search toward regions with high expected improvement while still exploring uncertain areas of the hyperparameter space.

In all model evaluations—including those performed inside the BO routine, the validation error was computed as a design-based weighted RMSE, using TIMSS sampling weights (TOTWGT). The corresponding weighted squared-error loss is:

Here, is the TIMSS sampling weight (TOTWGT), proportional to the inverse probability of selection under the multistage stratified sampling design; is the observed achievement score; is the prediction given parameters . The term represents the contribution of each population-representative unit to the design-based estimator of the population mean squared prediction error [36,37]. When survey weights are correctly specified and the model is well defined, minimizing the weighted validation RMSE yields parameter estimates and predictive performance measures that approximate population-level generalization. Because the BO routine optimizes this weighted validation RMSE, the selected hyperparameters target improved performance at the population level rather than over the observed sample. Bayesian optimization therefore provides a sample-efficient and computationally effective approach for tuning heterogeneous GNN architectures, particularly in large multi-level graph structures where each model evaluation requires full forward and backward propagation. Compared with grid or random search, BO explores far fewer configurations while reliably identifying high-performing hyperparameter settings.

2.5. Model Explainability (GNNExplainer)

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) provide high prediction accuracy, but the limited interpretability of the model’s decision-making mechanism poses a significant disadvantage. Therefore, the GNNExplainer method was used in this study to increase the model’s explainability [38]. GNNExplainer aims to identify the edge structure and features that most influence the model’s prediction at a node or subgraph level. To this end, a continuous-valued mask matrix M is learned for each edge and feature. Mask values range from 0 to 1, with the following definitions:

- Values close to 1 indicate that the relevant edge/feature is critical for prediction.

- Values close to 0 indicate that it is insignificant.

This approach is mathematically formulated as follows:

Here, denotes the subgraph selected by the mask, represents the features selected by the mask, and indicates the mutual information between the prediction and this substructure. The objective is to optimize the mask matrix M such that the resulting subgraph and features can explain the original model’s prediction as accurately as possible. In this way, GNNExplainer reveals which structural relationships and features the model relies on most during the prediction process [38]. In heterogeneous graph structures, GNNExplainer can, in principle, analyze the contribution of multi-level interactions between different node types (e.g., students, schools, and countries). However, in this study, explanations were computed only for student nodes, consistent with our focus on student-level prediction outcomes. This approach enables a structural-level interpretation of the decision mechanisms of graph-based models and improves model reliability.

Beyond this core formulation, GNNExplainer learns node and edge masks through a gradient-based optimization procedure, which seeks to identify the minimal subgraph that preserves the model’s prediction [38]. However, the optimization objective is non-convex, which may lead to instability across runs depending on initialization [39]. Furthermore, GNNExplainer yields node-level (local) explanations, meaning that an explanation is computed independently for each node. As a result, global interpretability demands aggregating these local explanations across many nodes [40].

In this study, GNNExplainer was applied at the individual student-node level to identify which student-level features contributed most strongly to the model’s predictions. Since GraphSAGE aggregates information from school and country nodes into student representations through message passing, these contextual factors influence predictions indirectly via learned embeddings. However, GNNExplainer does not decompose this influence into explicit edge- or neighbor-level importance scores in this setting. Therefore, the explanations should be interpreted as reflecting feature-level (node-attribute) importance rather than edge-level or explicit cross-hierarchical relational importance.

To obtain population-level insights, the local explanations computed for each student were aggregated to produce global feature-importance rankings. This approach provides interpretability for student-level characteristics while acknowledging that cross-hierarchical effects are implicitly encoded in the learned representations rather than directly isolated by the explainer.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

Evaluation metrics are quantitative indicators that measure the performance of regression models. Using different metrics together reveals different aspects of the model’s accuracy and error structure [41].

3. Application

In this section, the heterogeneous graph-based methodology is applied to the TIMSS 2023 eighth-grade mathematics achievement data. TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) offers a multi-level structure where students are connected to schools, and schools to countries, forming a natural tripartite graph. This structural organization makes TIMSS a suitable case study for evaluating graph-based methods on educational data with hierarchical dependencies. This section describes the data characteristics, the generation of the heterogeneous graph structure from the TIMSS data, preprocessing procedures, and technical details specific to this application.

3.1. Data Description

The dataset used in this study was obtained from the Grade 8 mathematics test and contextual questionnaires of the 2023 TIMSS survey. TIMSS determines student achievement using a multistage sampling method (country → school → class → student), meaning each student does not have an equal probability of being selected [42] This hierarchical sampling structure naturally aligns with the tripartite graph formulation, this sampling structure naturally corresponds to a tripartite graph, where student nodes are connected to school nodes via enrollment edges, and school nodes to country nodes via location edges. The consideration of sampling weight is necessary in weighted analyses, as emphasized in TIMSS technical reports [43].

In this study, 25 countries and 10,000 students were selected to balance computational feasibility and representativeness. The 25 selected countries were chosen to represent diverse education systems and provide sufficient variability for comparative analysis. The student sample was created using stratified random samples to preserve distributions at the country and school levels, resulting in a total of 789 schools. This sampling strategy yields a tripartite graph with |V| = 10,814 nodes (10,000 students + 789 schools + 25 countries). Descriptive statistics reveal that the weighted mean of mathematics achievement scores for Grade 8 students in the selected sample is 458.2, with a standard deviation of 121.4. Distributions of student characteristics show balanced gender representation; variables such as parental education level, socio-economic indicators, number of books at home, and computer and internet access exhibit distributions consistent with the broader TIMSS population.

The node features are defined for each partition as follows: Student-level features include demographic characteristics (e.g., gender and language), family background (e.g., parental education), home learning resources (e.g., books and technological access) and internet usage patterns. School-level features capture institutional characteristics such as school type, class size, teacher–student ratios and available resources. Country-level features incorporate dummy variables and macro indicators representing system-level characteristics (Appendix A). These multi-level variables form the feature sets for the three node types in the heterogeneous graph structure.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

A comprehensive preprocessing procedure was applied to the TIMSS 2023 dataset. Missing values were imputed using median imputation to prevent sample loss, in line with recommendations for large-scale educational research [43]. Categorical variables (e.g., gender and language spoken at home) were dummy-coded, while ordinal and numerical variables (e.g., parental education level and number of books at home) were included directly. Variables reflecting the home environment (own room, study desk, computer and internet access) and internet usage patterns were integrated into student-level features. School-level contextual variables were assigned directly to the relevant school nodes and country-level dummy variables were created to capture system-level characteristics.

To prevent differences in scale from affecting the performance of the model, z-score standardization was applied to all numerical features. During model training, the target variable (mathematics achievement score) was also z-standardized using only statistics from the training set to prevent data leakage. At inference stage, the predictions were de-standardized to obtain final scores on the original TIMSS scale.

The target variable was used directly, without residualization (i.e., removing higher-level variance components such as school or country effects before constructing the graph), enabling the heterogeneous GNN models to learn the effects specific to each partition through node embeddings. School-level node embeddings capture institutional characteristics and contextual effects in aggregate, while country-level embeddings encode system-wide patterns and macro-level factors. The message-passing mechanism enables information to flow hierarchically, from country nodes to school nodes and then to student nodes. This enables the model to learn about individual students, school-level contextual effects and country-level systemic patterns simultaneously through the tripartite graph structure.

3.3. Graph Construction

3.3.1. Construction Process

A tripartite heterogeneous graph structure representing relationships between students, schools, and countries was constructed using TIMSS 2023 data. This structure incorporates three distinct node types: student-level nodes (characterized by BSBG variables), school-level nodes (contextualized by ACBG variables), and country-level nodes (representing system-level factors). Students are connected to their schools, and schools to their countries via undirected typed edges, thus capturing multi-level hierarchical relationships directly through the network topology. While the education system exhibits a natural hierarchy (students belong to schools, schools belong to countries), the graph structure is undirected to enable bidirectional message passing in GNN learning. Formally, the tripartite heterogeneous graph.

is defined with the following structure:

Node Set (3-partite structure): where and ensuring pairwise disjoint partitions.

Edge Set (hierarchical constraints):

and all edges are treated as undirected for GNN computation.

For any edge , the reverse edge is implicitly included, ensuring symmetric adjacency.

That is, This construction preserves the hierarchical structure of the TIMSS data while enabling the bidirectional information flow required by standard GNN message-passing mechanisms. Accordingly, two relationship types are defined:

No intra-partition edges (e.g., student-student, school-school, or country-country) are permitted.

Type Mapping Functions:

assigns each node to its partition type, and

assigns each edge to its relationship type (student—school or school—country).

The resulting graph forms a hierarchical undirected tripartite structure, where edges exist only between adjacent levels of the educational hierarchy. The tripartite constraint—no intra-partition edges—combined with typed inter-level edges preserves the multi-level semantics of the TIMSS framework without requiring edge directionality.

For GNN computation, message-passing operations are performed on this undirected structure, which enables bidirectional information flow. Under this mechanism, student nodes receive contextual information from their associated school and indirectly from country nodes through 2-hop propagation, while school and country nodes aggregate information from their constituent students and schools, respectively.

- Node features:

Student nodes: 72 socio-economic and demographic indicators (BSBG variables), median imputation and z-score standardization applied.

School nodes: Learnable embedding vectors, H = 192 dimensions. School node embeddings were initialized using ACBG contextual variables (e.g., school type, class size, teacher–student ratio, available resources) and subsequently refined through backpropagation during model training. This initialization strategy provides a meaningful starting point based on institutional characteristics, which is then adapted through end-to-end learning to capture school-level effects on student achievement.

Country nodes: Learnable embedding vectors with H = 192 dimensions, randomly initialized and updated during training to represent system-level differences across education systems.

- Edge structure:

: Each student node is connected to the school node it is enrolled in via an undirected edge (identified by IDSCHOOL). Total number of students–school edges:

: Each school node is connected to its country node via an undirected edge (identified by IDCNTRY). Total number of schools–country edges:

- Target variable:

Student-level mathematics achievement was defined as the average of five plausible values (BSMMAT01-05) and weighed using TIMSS sampling weights. During model training, the target variable was standardized using the mean and standard deviation of the training set; during the estimation phase, it was converted back to the original TIMSS scale.

- Embedding size selection:

For school and country nodes, the embedding size (H) is a critical hyperparameter that affects the performance of the model. In the initial phase, preliminary experiments were conducted with H set to 192 and the Adam optimizer to examine the model structure’s general behavior and verify the trainability of the graph structure. This value produced stable convergence and competitive validation performance in the preliminary experiments, aligning with standard practices outlined in the GNN literature [12]. Subsequently, all hyperparameters, including H, the embedding size for each GNN model, were systematically determined using a Bayesian optimization process. This two-stage approach ensured the validation of the model structure and identification of the optimal combination of hyperparameters.

Given the hierarchical nature of the tripartite TIMSS graph, we formalize the relationship between graph structure and optimal GNN depth by analyzing the information propagation properties under the message-passing scheme.

Let be the undirect tripartite graph defined above and let denote its underlying graph structure (ignoring node and edge type information). Since all edges in E are undirected, preserves.

For any two nodes , the graph distance is defined as the length of the shortest path between and in .

In the TIMSS tripartite graph, each student node is adjacent to exactly one school node , and each school node is adjacent to exactly one country node . Therefore, the distances satisfy

Thus, the diameter of the tripartite structure (restricted to meaningful educational pathways) equals 2.

Under a standard message-passing GNN, each layer aggregates information from the 1-hop neighborhood in . Formally, for each layer :

where denotes the 1-hop neighbors of .

Proposition 1.

Under this message-passing scheme [44] two GNN layers are sufficient for any student node to aggregate information from both its school node and its country node .

Proof.

- Layer 1:

- School nodes aggregate from their country neighbors; student nodes aggregate from their school neighbors.

Hence, encodes both school- and country-level information.

- Layer 2:

Student nodes aggregate again from their school neighbors. Because already contains country-level information,

meaning the student representation incorporates all three hierarchical levels.

Thus, two layers are sufficient for complete hierarchical aggregation in the tripartite graph. Since the graph diameter is 2, additional layers do not expand the receptive field but may cause over-smoothing, where repeated aggregation reduces representational discriminability [45].

3.3.2. Graph Properties

The structural properties of the constructed heterogeneous graph are presented in Table 1, including node and edge counts, degree statistics, and network density.

Table 1.

Structural Properties of the Heterogeneous TIMSS Graph.

As can be seen in Table 1, the generated heterogeneous graph contains 10,814 nodes and 10,789 edges. The graph density (edge-to-node ratio of 0.9977) is quite low, reflecting the sparse nature of the hierarchical educational data. Sparse graph structures offer computational advantages for GNN models and allow message-passing mechanisms to operate effectively [9,12]. These structural features demonstrate that the proposed heterogeneous graph preserves the inherent hierarchy of real-world educational data and is suitable for large-scale GNN applications.

4. Results

The TIMSS 2023 eighth-grade mathematics achievement data was subjected to a comprehensive modeling process that considered its multilevel structure. Three modeling approaches were evaluated: baseline models (linear regression, ridge regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, SVR, and CatBoost), heterogeneous GNN models (GCN, GAT, GIN, and GraphSAGE), and GNN models optimized with Bayesian optimization. All models were applied to the same dataset, and their predictive performance was compared using the R2, RMSE, and MAE metrics. In the second stage, the model with the best performance was analyzed using the GNNExplainer method to improve interpretability. Baseline models were constructed using student-level demographic and home environment variables, as well as school- and country-level contextual variables (as fixed effects). The data were randomly split at the student level into 70% training data and 30% test data. Missing values were imputed using the median; categorical variables were dummy-coded; and numerical variables were z-score standardized. To prevent data leakage, all preprocessing steps were applied only to the training data, with transformation applied to the test data. To account for the multistage sampling design of TIMSS, the total sampling weight (TOTWGT) was used as the case weight in all analyses. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using systematic grid search and 3-fold cross-validation. Table 2 shows the optimized hyperparameters of the baseline models.

Table 2.

Tuned hyperparameters of baseline models are estimated with cross-validation.

Different configurations were tested in terms of model depth and embedding size when training heterogeneous GNN models (GCN, GAT, GIN and GraphSAGE). Initially, an embedding size of H = 192 and two- to three-layer structures were employed. This value produced consistent results in preliminary experiments and was found to align with settings commonly employed in GNN literature [12]. Dropout regularization was applied to all GNN models to prevent overfitting, and the Adam optimization algorithm [46] was used. During model training, an early stopping strategy based on RMSE of the validation set was employed to enhance generalization. Then, the optimal hyperparameters for each GNN model were determined using Bayesian optimization. A systematic search was performed for the learning rate, dropout rate, number of layers, embedding size (H) and weight decay parameters, using a Gaussian process-based expected improvement (EI) gain function. The best hyperparameter combinations for each model were obtained by minimizing the root mean square error (RMSE) on the validation set. Table 3 shows the optimal hyperparameters obtained through Bayesian optimization. Notably, the embedding size (H) values varied between 71 and 192 across models, suggesting that different GNN architectures require distinct representation capacities. Notably, smaller embedding sizes were found for the GCN_Bayesian and GraphSAGE_Bayesian models compared to the H = 192 value used in preliminary experiments. This reduction suggests that better generalization performance can be achieved by optimizing the hyperparameters together to create a more compact representation [17].

Table 3.

Optimal hyperparameter values for heterogeneous GNN models obtained via Bayesian optimization.

As shown in Table 3, the optimal number of layers for all heterogeneous GNN models was found to be two. This result has a rigorous graph-theoretical justification: in the tripartite graph with structure

the diameter of the underlying undirected graph equals 2. Thus, any student node can reach country-level information in exactly two hops. Since a -layer GNN aggregates information from the -hop neighborhood under standard message passing [44], two layers are both necessary (to reach the full 2-hop receptive field) and sufficient (as deeper layers do not expand the receptive field but instead cause over-smoothing [45,47]

Deeper architectures (three to four layers) exhibited lower validation performance, confirming the over-smoothing effect, where repeated aggregation reduces representational discriminability.

For each architecture, the cost of a single message-passing layer depends on the number of nodes , edges , and embedding dimension . Using sparse adjacency matrices, the per-layer time complexity of GCN, GIN, and GraphSAGE with mean aggregation is

where the dominant cost arises from sparse matrix–vector multiplication along edges and linear transformations at nodes. In contrast, GAT requires computing attention coefficients and weighted messages for every edge; with attention heads, the per-layer complexity becomes

which is typically more expensive in both computation and memory.

In the tripartite TIMSS graph used in this study, edges exist only between students, schools, and countries (no intra-partition edges). As a result, grows approximately linearly with , and node degrees remain bounded. This sparse structure enables nearly linear scaling for aggregation-based architectures (GCN, GIN, GraphSAGE), whereas attention-based GAT incurs additional overhead due to edge-level attention computations.

Table 4 shows a comparison of the performance of the test sets for the baseline models, the heterogeneous GNN models and the Bayesian-optimized GNN models. All performance metrics were calculated by applying the TIMSS sampling weights (TOTWGT).

Table 4.

Model performance comparison across baseline and GNN variants.

As shown in Table 4, linear methods (Linear Regression and Ridge Regression) exhibited relatively high error metrics, with R2 values around 0.52–0.53 and RMSE values exceeding 80. In contrast, ensemble methods (XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM) outperformed these models, with XGBoost achieving the best baseline performance (R2 = 0.5786, RMSE = 74.87).

When examining the performance of heterogeneous GNN models before Bayesian optimization, significant differences are observed across architectures. The GCN model (R2 = 0.5153, RMSE = 86.66) performed lower than baseline methods, falling behind even linear regression models. This weak performance stems from the spectral convolution mechanism failing to adapt to the tripartite graph structure with initial hyperparameter configurations, particularly the embedding dimension H = 192. The subsequent determination of the optimal embedding size for GCN as H = 71 through Bayesian optimization confirms that the initial configuration was unsuitable for this architecture. In contrast, GAT (R2 = 0.5593, RMSE = 83.35) and GIN (R2 = 0.5646, RMSE = 82.94) models demonstrated substantially better performance than linear baseline models (R2 ≈ 0.52–0.53), with accuracy levels approaching ensemble methods. These results represent acceptable performance for educational data in literature. Most notably, the GraphSAGE model exhibited strong performance even without Bayesian optimization (R2 = 0.5798, RMSE = 74.85, MAE = 58.24)—outperforming all baseline methods and achieving results nearly identical to XGBoost. This exceptional robustness stems from GraphSAGE’s architectural design, which is inherently well-suited to hierarchical graph structures. The fixed-size neighborhood sampling mechanism manages information flow across school nodes with heterogeneous student enrollments (in-degree: 1–60, mean: 12.29), while the concatenation-based aggregation strategy creates representations more resilient to hyperparameter misspecification compared to spectral convolution or attention mechanisms. Significant performance improvements were observed in all heterogeneous GNN models following Bayesian optimization. The improvement was particularly dramatic for GCN (R2 = 0.5153 → 0.5845, RMSE = 86.66 → 71.38), demonstrating the critical importance of hyperparameter optimization for convolution-based architectures. GAT and GIN models achieved similar gains, with error metrics converging to RMSE ≈ 71–72 and surpassing all baseline methods.

The GraphSAGE_Bayesian model achieved the highest explanatory power among all models (R2 = 0.6187, RMSE = 71.72, MAE = 64.32), surpassing the best baseline model (XGBoost: R2 = 0.5786) and demonstrating the best modeling capacity of graph-based representations on multi-level educational data. The strong performance of GraphSAGE was further enhanced through Bayesian optimization, indicating that systematic hyperparameter search can improve performance beyond the architecture’s inherent robustness.

The Bayesian optimization process identified architecture-specific optimal hyperparameters tailored to the tripartite structure (Table 3). Notably, two-layer architecture achieved the highest accuracy across all models, consistent with the tripartite graph’s characteristics: two message-passing layers provide sufficient information flow for student nodes to access contextual information at school and country levels. Deeper architectures (3–4 layers) caused over-smoothing problems on the validation set and exhibited lower performance.

These findings demonstrate that architecture selection and hyperparameter optimization must be considered jointly in heterogeneous GNN models. While robust architectures like GraphSAGE perform well initially, spectral methods like GCN reach their potential only through systematic optimization. Consequently, heterogeneous graph representations combined with Bayesian optimization outperform fixed-effects models on multi-level educational data.

The higher explained variance of GraphSAGE_Bayesian is directly related to how the graph structure represents multi-level relationships. Traditional regression models explain student achievement through variable coefficients and represent school and country contexts as fixed effects, capturing complex relationships only to a limited extent. The GraphSAGE model, conversely, incorporates school- and country-level contextual information alongside individual student characteristics into the graph structure via learnable embeddings. However, while GraphSAGE provides strong predictive performance, it does not directly indicate which features are most critical. To address this, the best-performing GraphSAGE_Bayesian model was analyzed using GNNExplainer.

To address this, the best-performing GraphSAGE_Bayesian model was analyzed using GNNExplainer. GNNExplainer calculated the relative importance of each variable using weighted gradient-saliency scores. Since these scores are derived from the model’s gradient sensitivities, significance should be evaluated based on variable rankings and cumulative contributions [38]. Figure 2 shows the top 20 student-level variables with the highest contribution of all students.

Figure 2.

Top Global Features Across All Students by GNNExplainer.

The findings indicate that the most influential determinants of student achievement are home learning resources, parental education level, and access to digital learning opportunities. Key indicators include availability of personal study space (own room and desk), access to technology (computer, smartphone, internet), number of books at home, and parental education level—all markers of socioeconomic status. Internet use for educational purposes showed strong associations with achievement, as did motivational and psychosocial factors such as valuing mathematics achievement, discussing environmental issues, and perceiving school safety.

While GNNExplainer analyzed only student nodes, school- and country-level contextual information was incorporated indirectly through GraphSAGE’s message-passing mechanism. Thus, the explainer does not isolate the importance of school or country nodes explicitly, but these contextual effects are reflected implicitly in the learned student representations. This explains why two students with similar socioeconomic characteristics may receive different predictions depending on the school and country to which they are connected. Whereas traditional methods encode school and country contexts as fixed dummy variables, GraphSAGE represents them as learnable embeddings interacting with student features.

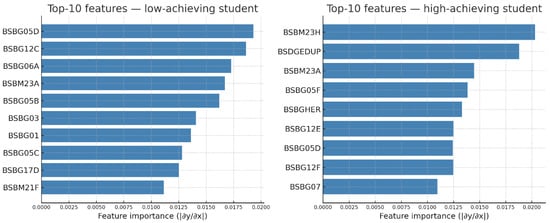

Analyses were also conducted for low- and high-achieving student groups. Figure 3 presents the top 10 variables with the highest contribution for both groups.

Figure 3.

Top 10 Features for a Low-Achieving Student and a High-Achieving Student by GNNExplainer.

Figure 3 shows that predictive factors for low-achieving students relate more closely to home environment and digital access opportunities: internet access, online collaboration with classmates, access to shared computing facilities, and language spoken at home. In contrast, predictive factors for high-achieving students include parental education level, attitudes toward mathematics achievement, and home educational resources (see Appendix B). Therefore, low-achieving students’ performance is more strongly explained by basic digital access, while high-achieving students’ performance is more strongly explained by parental education and cultural capital indicators. These results align with findings in the TIMSS literature [43,48,49].

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study presents a methodological framework for using heterogeneous graph neural networks in modeling multilevel educational data. Hierarchical structures where students are linked to schools and schools to countries have long been a fundamental analytical challenge in educational research. While traditional approaches address this structure, they confine school and country effects to predetermined parametric forms. The graph-based approach proposed in this study aims to overcome this limitation by incorporating school and country contexts into the model for learnable node representation. TIMSS 2023 eighth-grade mathematics achievement data was used to assess the validity of the methodology. A tripartite graph structure consisting of 10,000 students, 789 schools, and 25 countries were created. Four different heterogeneous GNN architectures (GCN, GAT, GIN, GraphSAGE) were evaluated, and optimal hyperparameters were determined for each using Bayesian optimization. The results demonstrate that heterogeneous GNN architecture exhibits distinct performance characteristics. Even without Bayesian optimization, the GraphSAGE model outperformed all baseline methods, performing competitively with the strongest baseline model (XGBoost; R2 = 0.5786 vs. GraphSAGE; R2 = 0.5798). This robustness stems from GraphSAGE’s sampling-based aggregation mechanism, naturally fitting hierarchical training data. The GAT and GIN models also significantly outperformed linear methods. In contrast, the GCN model initially performed poorly but surpassed all baseline methods following Bayesian optimization. These findings emphasize the importance of both hyperparameter and architecture selection. Following Bayesian optimization, GraphSAGE_Bayesian achieved the highest explained variance (R2 = 0.6187), while GCN_Bayesian achieved marginally lower RMSE (71.38 vs. 71.72) and MAE (64.21 vs. 64.32). These differences are practically negligible on the TIMSS scale, and both models substantially outperformed baseline methods. The optimal number of layers in all GNN models is 2, which is consistent with the topological properties of the tripartite graph structure. Two message-passing layers provide sufficient information flow for student nodes to access contextual information at school and country levels. GNNExplainer analyses further clarify the modeling behavior of the graph structure. Individual characteristics such as parental education level, number of books at home, and access to digital resources emerged as strong predictors, as expected. Since GNNExplainer was applied only to student nodes, the explanations primarily reflect student-level features. However, the model’s predictions also vary across students with similar individual characteristics, which indicates that contextual information from school and country nodes is incorporated indirectly through GraphSAGE’s message-passing mechanism, even though this influence is not isolated explicitly by the explainer. The fact that digital access and basic resources are more significant for low-achieving students, and parental education and cultural capital are more significant for high-achieving students, offers important insights into the design of targeted interventions for different student groups. The original contribution of this study lies in the systematic application of heterogeneous graph neural networks to multi-level educational data and the comparative evaluation of different GNN architectures’ performance characteristics. While traditional multi-level modeling approaches have been successful in representing hierarchical educational data within parametric structures, they constrain school and country effects through predetermined functional forms [50,51]. This study empirically demonstrates how graph-based representations can overcome this limitation. Notably, GraphSAGE’s strong performance even without hyperparameter optimization constitutes an original finding that reveals this architecture’s natural compatibility with hierarchical educational data. The sampling-based aggregation mechanism proposed by Hamilton et al. [12] demonstrated more robust performance in tripartite educational data compared to spectral convolution [9] or attention mechanisms [10], emphasizing the importance of architectural design alignment with data structure.

The necessity of jointly considering architecture selection and hyperparameter optimization provides an important methodological insight for the effective use of graph-based models in educational research. The Bayesian optimization process [17], identifying different optimal hyperparameters for each architecture, demonstrates that GNN models require dataset-specific tuning. A notable implication of these results is that heterogeneous GNNs do not automatically outperform strong tabular baselines on multi-level educational data. In our study, the initial GraphSAGE model performed statistically equivalently to XGBoost (R2 ≈ 0.58), which reflects the robustness of tree-based ensemble methods and the well-known sensitivity of GNNs to architectural choices such as embedding size, number of layers, and aggregation strategy. However, once hyperparameters were systematically optimized through Bayesian optimization, the GraphSAGE model achieved substantially higher explained variance (R2 = 0.6187), revealing modeling capacity that remained latent under default settings. This demonstrates that the advantage of graph-based representations is not inherent but emerges only when hyperparameters are aligned with the structural properties of the tripartite educational graph. Importantly, the generalizability of empirical findings should be interpreted with care. The conclusions drawn from this study—such as the suitability of two message-passing layers—reflect the specific structural properties of the TIMSS graph, which is sparse, low-diameter, and strictly hierarchical. These results are most directly transferable to other multi-level or k-partite systems that exhibit comparable topological characteristics. Broader applications to domains with substantially different graph structures (e.g., dense, highly cyclic, or non-hierarchical networks) would require separate empirical validation rather than direct extrapolation. In this respect, our methodological framework is general, but the numerical findings are context dependent. Accordingly, our contribution lies not only in applying heterogeneous GNNs to educational data, but also in providing a systematic optimization framework that enables these models to fully exploit multi-level relational structures.

Furthermore, the direct relationship between the optimal number of layers and the graph diameter in the tripartite structure (diameter = 2 → optimal layers = 2) empirically validates the link between graph topology and deep learning architecture. This result is consistent with the over-smoothing behavior observed in deeper GNN models, which became apparent after two layers in our structure [45]. The GNNExplainer analysis further illustrates how contextual information from school and country nodes is integrated into student representations—even though explanations were computed only for student nodes—demonstrating that the model captures multi-level dependencies implicitly through message passing.

An important limitation concerns the scope of generalizability of our empirical findings. While the Bayesian optimization framework introduced in this study is methodologically applicable to a broad range of heterogeneous or multi-level graph settings, the specific architectural results—such as the optimality of a two-layer message-passing architecture—are inherently tied to the structural characteristics of the TIMSS tripartite graph (diameter ≈ 2, sparse hierarchical connectivity). These findings may reasonably extend to other domains that exhibit comparable layered multi-level structures (e.g., student–school–country; employee–department–company; patient–clinic–hospital). However, they should not be directly extrapolated to domains whose topologies differ fundamentally, such as dense biological interaction networks or scale-free protein systems, where optimal depth and aggregation behavior follow different structural dynamics.

Taken together, these results show that heterogeneous GNNs offer meaningful advantages over traditional multi-level modeling approaches from both methodological and practical perspectives. For education policymakers and school administrators, this framework provides a valuable tool for early identification of at-risk student groups, as well as a deeper understanding of contextual effects and the design of targeted interventions. GraphSAGE’s robustness also indicates that effective models can be constructed even under limited computational resources, which is particularly advantageous in applied educational settings.

Future work should extend this framework to heterogeneous graphs with diverse topological properties, including bipartite, k-partite, and dynamic graph structures. Systematically evaluating how structural features—such as graph diameter, degree distribution, and clustering coefficient—affect optimal hyperparameters and model performance would help define the broader applicability and limitations of heterogeneous GNNs in complex relational systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Methodology, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Software, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Validation, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Formal analysis, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Investigation, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Resources, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Data curation, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Writing—original draft, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Writing—review & editing, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Visualization, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Supervision, M.A.C.; Project administration, T.K., M.A.C. and H.K.; Funding acquisition, M.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number: IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are derived from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2023 database, publicly available at https://timssandpirls.bc.edu. Processed datasets and graph structures generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix lists the official TIMSS 2023 codebook variables used to construct student-, school-, and country-level features for the heterogeneous graph structure.

Table A1.

Official TIMSS Codebook Variables.

Table A1.

Official TIMSS Codebook Variables.

| Official Codebook Code | Official Description |

|---|---|

| BSBG05D | Home Possessions—Internet access |

| BSBG05F | Home Possessions—Own room |

| BSBG04 | Number of books in your home |

| BSDGEDUP | Parents’ Highest Education Level |

| BSBG05E | Home Possessions—Study desk |

| BSBG12A | Internet use—For learning (frequency) |

| BSBG05C | Home Possessions—Smartphone |

| BSBG05A | Home Possessions—Own computer |

| BSBG05D | Home Possessions—Internet access |

| BSBG12B | Internet use—Access assignments (frequency) |

| BSBG12C | Internet use—Collaborate with classmates (frequency) |

| BSBG12D | Internet use—Ask teacher questions (frequency) |

| BSBG12E | Internet use—Find info to aid in math or science (frequency) |

| BSBG12F | Internet use—Access learning games (frequency) |

| BSBGHER | Home Educational Resources (Index) |

| BSDGHER | Home Educational Resources (Scale) |

| BSDG05S | Number of Home Study Supports |

| BSBM23I | Math—Agree: Important to do well in math |

| BSBG15C | General—How often talk about environment |

| BSBG16B | General—Agree: Safe at school |

Appendix B

This appendix provides the list of features most influential in distinguishing low- and high-achieving student groups as identified by feature importance analysis.

Table A2.

Feature Codes for Low-Achieving Student.

Table A2.

Feature Codes for Low-Achieving Student.

| Official Codebook Code | Official Description |

|---|---|

| BSBG05D | Home Possessions—Internet access |

| BSBG12C | Internet use—Collaborate with classmates (frequency) |

| BSBG06A | GEN—Highest level of education of parent/guardian |

| BSBM23A | Math—Agree: Mathematics will help me |

| BSBG05B | Home Possessions—Shared computer |

| BSBG03 | GEN—Often speak language of test at home |

| BSBG01 | Sex of student |

| BSBG05C | Home Possessions—Smartphone |

| BSBG17D | GEN—How often refused to talk |

| BSBM21F | Math—How often other students’ behavior affects learning |

Table A3.

Feature Codes for High-Achieving Student.

Table A3.

Feature Codes for High-Achieving Student.

| Official Codebook Code | Official Description |

|---|---|

| BSBM23H | Math—Agree: Parents think math important |

| BSDGEDUP | Parents’ Highest Education Level |

| BSBM23A | Math—Agree: Mathematics will help me |

| BSBG05F | Home Possessions—Own room |

| BSBGHER | Home Educational Resources (Scale) |

| BSBG12E | Internet use—Find info to aid in math or science (frequency) |

| BSBG12F | Internet use—Access learning games (frequency) |

| BSBG05D | Home Possessions—Internet access |

| BSBG12F | Internet use—Access learning games (frequency) |

| BSBG07 | How far in education do you expect to go |

References

- Wang, X.; Bo, D.; Shi, C.; Fan, S.; Ye, Y.; Yu, P.S. A survey on heterogeneous graph embedding methods, techniques, applications and sources. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2022, 9, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, R.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, M.; Meng, F.; Ma, H.; Qiao, S. Heterogeneous graph neural networks analysis: A survey of techniques, evaluations and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8003–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chartrand, G. Introduction to Graph Theory; Tata McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.L.; Yellen, J.; Anderson, M. Graph Theory and Its Applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Klasing, R. The g-good-neighbor diagnosability of product networks under the PMC model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.19463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; Du, Y.; Fan, Y.; Chen, X. The G-Good-Neighbor Conditional Diagnosabilities of Hypermesh Optical Interconnection Networks Under the PMC and Comparison Models. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. 2024, 35, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Sun, B.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Gui, W. A hierarchical stochastic network approach for fault diagnosis of complex industrial processes. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2025, 12, 1683–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 20, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. Stat 2017, 1050, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Multi-order-content-based adaptive graph attention network for graph node classification. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; NIPS: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Huang, C.; Swami, A.; Chawla, N.V. Heterogeneous graph neural network. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, M.; Pan, S.; Ye, X.; Fan, D. Simple and efficient heterogeneous graph neural network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 10816–10824. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, C.; Pan, S.; Zhu, X.; Wang, B. Relation Structure-Aware Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Beijing, China, 8–11 November 2019; pp. 1534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, L.; Li, H. High-order topology-enhanced graph convolutional networks for dynamic graphs. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; NeurIPS: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriari, B.; Swersky, K.; Wang, Z.; Adams, R.P.; de Freitas, N. Taking the human out of the loop: A review of Bayesian optimization. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 148–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, N. BMO-GNN: Bayesian mesh optimization for graph neural networks to enhance engineering performance prediction. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtkrull, M.; Kipf, T.N.; Bloem, P.; van den Berg, R.; Titov, I.; Welling, M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 15th Extended Semantic Web Conference (ESWC 2018), Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 3–7 June 2018; pp. 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ji, H.; Shi, C.; Wang, B.; Ye, Y.; Cui, P.; Yu, P.S. Heterogeneous graph attention network. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhu, W. Deep learning on graphs: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H. The heterogeneous network community detection model based on self-attention. Symmetry 2025, 17, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ni, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Collaborative representation learning for nodes and relations via heterogeneous graph neural network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 255, 109673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics a Modern Approach; South-Western Cengage Learning: Independence, KY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]