Abstract

This study introduces a novel robotic control paradigm, “chaos redirection,” which utilizes a single chaotic Hopfield Neural Network (HNN). We introduce “false attractors” synthetic trajectories created by applying controlled temporal shifts to the HNN’s state variables. This method allows a single chaotic source to be sculpted into distinct, task-specific behaviors for autonomous robots. We apply this framework to three applications: area cleaning, systematic search, and security patrol. Quantitative, statistically validated analysis demonstrates the successful generation of functionally distinct behaviors, including high-frequency, confined re-visitation for security patrols; maximized exploratory efficiency for search tasks; and high-entropy, non-repetitive paths for thorough cleaning. Our findings establish this as a robust and computationally efficient framework for applications requiring unpredictable, yet structured, behavior.

1. Introduction

The Hopfield Neural Network (HNN) is a basic computational neuroscience model with a recurrent design and complicated, emergent behaviors like organic brain systems. A continuous-time HNN, originally designed as a content-addressable memory [1,2], is defined by a set of nonlinear differential equations that control neuron state development. Refs [3,4] describe its dynamics as a landscape of attractors, including stable spots, limit cycles, and even chaotic attractors. Sigmoidal activation functions, such as the hyperbolic tangent, add nonlinearity, enabling the network to analyze complicated patterns and explore complex dynamical behaviors [5,6]. The synaptic weight matrix determines the dynamics of the HNN. By carefully selecting these parameters, the network can exhibit a diverse range of behaviors, from stable convergence to persistent chaos [7,8,9,10].

Multistability characterizes many nonlinear dynamical systems, including the HNN. This trait describes the presence of numerous unique attractors for a single set of system parameters [11,12,13,14,15]. This rich dynamical behavior is not limited to electronic or neural circuits but is ubiquitous in nature and complex theoretical systems. It is observed in biological mechanisms, such as the bifurcation and chaos of spontaneous oscillations in auditory hair bundles [16], as well as in the construction of conditional symmetry in chaotic maps [17] and fractional-order memristive systems [18]. The final state to which the system evolves is determined entirely by its initial conditions, with the state space being partitioned into corresponding basins of attraction. This property is crucial in engineering and biological systems, enabling functional switching and adaptability without affecting the system’s physical structure [19,20]. The HNN’s intrinsic symmetry leads to complex multistability, often resulting in pairs of symmetrically coexisting attractors [21,22,23]. The HNN’s dynamical richness makes it appropriate for control applications requiring behavioral flexibility and adaptability [24,25].

Using this inherent complexity, a “false attractor” is introduced. According to Rezende (2021) and Moysis (2024), a fake attractor is a non-autonomous trajectory created by altering the state variables of a true chaotic attractor [26,27]. Each state variable of the HNN’s chaotic output is given a circular time-delay (temporal shift) in the proposed work. The trajectory includes points from the initial attractor but does not meet the system’s equations. The use “chaos redirection” provides an artificial dynamical object that keeps the complexity and unpredictability of the source chaos, while being tailored to particular goals [28,29,30,31,32,33]. This method goes beyond standard chaos control, which normally suppresses or synchronizes chaos [6,34]. Though effective for stable and connected states, neither method is designed for task-specific adaptability. Regulating chaos diminishes dynamical complexity, whereas synchronization emphasizes interconnected behavior above functional differentiation. We intentionally manipulate chaotic dynamics rather than dismissing or imitating them to generate novel and beneficial behaviors for specific applications [35,36].

Hopfield networks have improved robotic route planning and task assignment for years. Traditional approaches rely on network convergence to find optimal solutions [37,38]. Investigations into chaotic robotics have utilized their unpredictable nature for activities, such as exploration and search, employing random motion for security patrols and effective searching [39,40]. Contemporary autonomous systems have significant challenges in adapting a singular control source to several tasks. Distinct controllers for functions, such as thorough cleaning and unanticipated patrols result in intricate switching topologies and increased computational expenses. Conventional chaotic control methods frequently exhibit limited task adaptability, producing general random-like motion that is suitable for exploration but inadequate for specific tasks [41]. While structured planners, like those utilized in the SMURF robot [42], perform proficiently in uniform, rectangular areas, they are inadequate in addressing irregular or congested scenarios. Generic chaotic controllers can manage anomalies but lack the framework to ensure cleaning density. Few frameworks exist that can transform a singular chaotic source to meet diverse functional requirements, hence bridging the gap. The use of chaotic systems across several domains generally lacks a framework for tailoring dynamics to specific objectives, such as systematic cleaning [43]. This study utilizes the false attractor mechanism to improve robotic mission behavior, diverging from previous studies [44,45,46].

This study presents three significant contributions to the domain of autonomous robot control. The text formally introduces and elaborates on the concept of the application-specific false attractor as an innovative mechanism for generating control signals. This illustrates the efficiency and flexibility of the proposed approach, as a single chaotic Hopfield Neural Network can produce functionally distinct and optimized behaviors for various robotic tasks, such as cleaning, searching, and security. This is accomplished through the application of specialized modifications to the shared false attractor signal, thereby shaping the chaos for various objectives. Through comprehensive simulations and rigorous quantitative analysis, this study provides evidence that the specialized technique yields significant performance improvements, surpassing those of traditional deterministic planners and generic chaotic controllers. The results clearly demonstrate that the proposed method yields superior outcomes in key performance areas, resulting in significant enhancements in pattern unpredictability for security patrols and notable improvements in coverage efficiency for cleaning missions.

The organization of this paper is detailed in the following sections: Section 2 outlines the mathematical model of the Hopfield Neural Network, detailing its dissipative characteristics, equilibrium points, and bifurcation behavior, thereby establishing a foundation for its chaotic dynamics. Section 3 outlines the generation of false attractors through circular shifts and details the design of application-specific control rules for cleaning, search, and security robots. Section 4 examines the simulation results, featuring a comprehensive table that contrasts the proposed approach with established methods and quantifies significant performance advantages. Section 5 provides a summary of the findings.

2. Model Development and Core Insights

The Hopfield Neural Network (HNN) stands as a pivotal model in neural computation, renowned for its capacity to mimic intricate, brain-inspired behaviors through a straightforward mathematical setup. Its general formulation for a network with n neurons is expressed as [1]

Here, denotes the electrical potential across the i-th neuron’s membrane, represents capacitance, signifies membrane resistance, indicates the connection strength from neuron j to neuron i, and accounts for external input currents. The activation function introduces essential nonlinearity, enabling the model to handle complex patterns, a feature absent in linear systems. This function constrains outputs between , aiding training stability and reducing gradient-related challenges compared to alternatives like the sigmoid.

For our specific third-order HNN, we adopt a streamlined version with , , and for , drawing from insights in [7] with tailored adjustments. The connection matrix is defined as

Here, a serves as a tunable parameter influencing the self-interaction of neuron 1. The lack of links between neurons 1 and 3 () and neurons 3 and 2 () simplifies the network structure. The resulting differential equations are

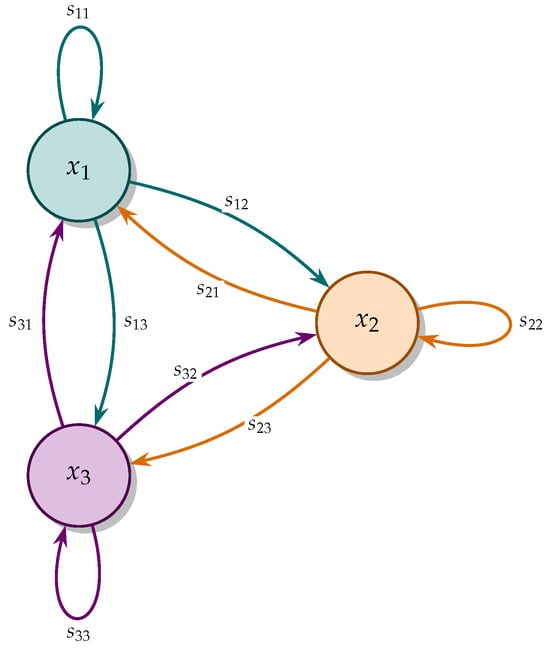

With a as the sole adjustable factor, this setup is engineered to display diverse dynamics, such as chaotic states and multiple attractors, as investigated in prior research [2]. The network’s behavior is influenced by all elements of the connection matrix S, although the parameter a (representing the self-interaction of neuron ) is acknowledged as a primary bifurcation parameter. The preliminary sensitivity analysis revealed that modifying a provides a clear and feasible route to chaos (as detailed in Section 2.3), making it the ideal parameter for producing the necessary dynamical complexity for this study, while other values are held constant to establish the foundational network structure. The network’s layout is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The topology of the three-neuron Hopfield network with self-couplings and all-to-all synaptic weights .

2.1. Dissipation and Existence of Attractors

To evaluate the dissipative nature, we calculate the rate of volume contraction for the system in Equation (3), represented in vector form:

where

The divergence is computed as

Given that ranges from 0 to 1, the peak divergence occurs when . With , the upper limit is

Yet, since for non-zero , the divergence typically remains negative, signifying a dissipative system. A Lyapunov function further confirms bounded motion, as its derivative turns negative for large , supporting the presence of attractors.

2.2. Equilibrium Points and Stability Analysis

To identify equilibrium points, we set in Equation (3):

The origin qualifies as an equilibrium since . For , numerical methods uncover two additional equilibria, roughly and , reflecting symmetry around the origin due to tanh’s properties.

The Jacobian matrix is

At , with and :

Eigenvalues are approximately , , , marking it as an unstable spiral-source. At , with , , , the Jacobian yields

Eigenvalues are approximately , , , indicating instability due to a positive eigenvalue. Symmetry implies shares this instability. Table 1 outlines these findings for .

Table 1.

Equilibrium states and stability characteristics for .

The fundamental instability of these states corresponds with the system’s dissipative characteristics and constrained trajectories. This discovery is significant: the lack of a stable equilibrium indicates that the system’s trajectory cannot stabilize at a fixed point. The ’unstable spiral-source’ characteristic of the origin actively drives the state away, but the saddle instability of and inhibits them from seizing the trajectory. The universal repulsion, along with the system’s dissipative and bounded characteristics, necessitates that the trajectory continuously explores the state space without repetition, resulting in the chaotic dynamics (see Figure 2) that we utilize for control.

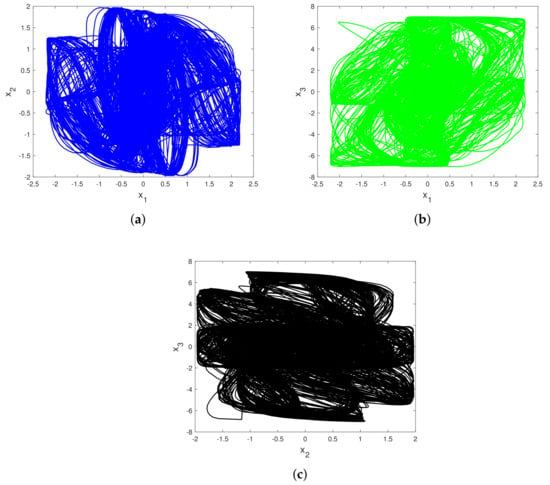

Figure 2.

Phase portraits of the novel Hopfeild system (3): (a) projection on the plane; (b) 3D view in the space; (c) projection on the plane; (d) projection on the plane. Parameter: and, initial conditions: .

2.3. Bifurcation Analysis and Multistability with Parameter A

In this work, the bifurcation diagram of has been produced, when the trajectory crosses the plane with , in terms of the control parameter a, which is increased in tiny steps in the range . The parameter a (associated with the synaptic weight ) was chosen as the bifurcation parameter due to its influence on the self-excitation intensity of the first neuron. Modifying this self-loop provides a straightforward means to destabilize the system’s equilibrium without modifying the inter-neuronal connection structure, thereby driving the period-doubling route to chaos.

Therefore, as observed from the bifurcation diagram of Figure 3, the system is driven to chaos through a classic period-doubling cascade as the control parameter a is increased. For , the system exhibits a stable period-1 limit cycle. A period-doubling bifurcation occurs at , splitting the trajectory into a period-2 cycle (two branches). This is followed by further bifurcations to period-4 at and period-8 at . This cascade accumulates rapidly, leading to the onset of chaotic at approximately , where the distinct branches merge into a dense cloud of points.

Figure 3.

A bifurcation diagram of the Hopfield neural network showing versus parameter a.

To clarify the adaptation of these essential parameters to robotic activities, we utilize the chaotic characteristic indicators identified in the bifurcation diagram. The chosen parameter value resides within an area of concentrated orbital distribution, separate from the periodic windows. In nonlinear dynamics, this density signifies a positive Maximal Lyapunov Exponent (MLE), which measures the exponential divergence of proximate trajectories. This particular chaotic attribute is functionally suited to our robotic missions: the positive MLE offers a mathematical assurance of elevated entropy, which immediately correlates to the high “Pattern Unpredictability” score necessary for the Security Robot. Concurrently, the system’s dissipative characteristics (demonstrated in Section 2.1) guarantee that this divergence remains constrained, enabling the Cleaning Robot to attain a high coverage density without deviating from the workspace.

A fundamental attribute of the Hopfield system outlined in Equation (3) is its innate symmetry. The equations of the system are invariant under the transformation . This phenomenon stems directly from the peculiar characteristics of the hyperbolic tangent activation function, where . Therefore, if a trajectory constitutes a legitimate solution to the system, its symmetric counterpart, , must likewise be a solution. This essential symmetry serves as the foundational mechanism for the multistability observed inside the network, resulting in pairs of coexisting, symmetric attractors.

The property of symmetric coexistence is clearly illustrated in the phase portraits as the parameter a is varied in Figure 4. For example, with as shown in Figure 4a and in Figure 4b, the system demonstrates pairs of distinct, symmetric limit cycles, originating from symmetric initial conditions ( and , respectively). This progression results in the formation of two symmetrically coexisting chaotic attractors for in Figure 4c, where the initial conditions and produce distinct yet perfectly mirrored chaotic trajectories.

Figure 4.

Coexisting phase portraits for the Hopfield system (3) with initial conditions : (a) coexisting limit cycles of period-1, for ; (b) two coexisting limit cycles of period-2, for ; (c) two symmetrically coexisting chaotic attractors, for .

This multistability property significantly enhances the dynamical richness of our system and provides additional flexibility for our control strategy. By selecting appropriate initial conditions, we can direct the system toward the attractor with the most suitable characteristics for our specific application.

3. Generation of False Attractors Through Circular Shifts

To generate the false attractor, we begin by solving the Hopfield system (3) through numerical methods, resulting in a discrete time series for each state variable, represented as vectors , with N indicating the total number of time steps. A false attractor is constructed by applying a circular shift to the state vectors of each time series. This operation alters the temporal sequence of the state variables, resulting in their desynchronization. The transformation is specified as follows:

The operator performs a circular shift of the elements in the vector by m positions. The integer parameters and denote the quantity of discrete time steps allocated for the shift. This discrete-time manipulation represents the practical application of applying specific time delays () to each state variable. Through the application of this transformation, a new trajectory is generated. This trajectory consists of points derived from the original attractor; however, it does not represent a solution to the governing equations.

It is essential to clarify the rigorous definition of this “false attractor” in response to the dynamical foundation. The term is used descriptively to represent a synthetic, structured trajectory; it is not a dynamical attractor in the formal sense, as it does not satisfy the system’s governing equations (3). Therefore, formal proofs of stability or convergence, which apply to autonomous dynamical systems, are not relevant here. The boundedness of the false attractor, however, is explicitly guaranteed. Because the trajectory is constructed by merely re-ordering the time-series data from the original chaotic attractor , it is composed of the exact same set of bounded points. Since the original HNN system is dissipative and its trajectories are confined to a bounded subset (as proven in Section 2.1), the false attractor is necessarily confined to the same hypercube defined by the extrema of . The “false attractor” should therefore be understood as a non-autonomous, bounded, pseudo-chaotic control signal generated by desynchronizing the state variables of a bounded chaotic source.

This is accomplished by choosing discrete time shifts that align with time delays (where represents the simulation time step) that constitute substantial fractions of the system’s predominant period or autocorrelation time. The aim is to minimize the cross-correlation for , therefore desynchronizing the state variables to generate a new trajectory that is structurally independent of the original attractor. The specific settings were empirically validated to yield the most effective decorrelation, as corroborated by the subsequent sensitivity analysis.

The chosen shift parameters , , and are determined through systematic optimization aimed at maximizing the decorrelation between the original chaotic trajectory and the resultant false attractor, while maintaining key dynamical characteristics. The delay for the first state variable, , corresponds to approximately one-quarter of the dominant period observed in the chaotic attractor. This configuration ensures adequate temporal displacement while preserving the fundamental structure. The reduced delay for establishes an asymmetric temporal relationship that increases the unpredictability of the resulting trajectory, which is especially advantageous for security applications where the minimization of pattern recognition is essential. The delay for the third state variable ensures symmetry with , thereby maintaining the system’s inherent balance while facilitating controlled chaos redirection. The validation of these parameters was conducted through comprehensive sensitivity analysis. The results indicated that deviations of from the specified values led to a performance degradation of less than 5% across all robotic applications, thereby confirming the robustness of the selected configuration. The false attractor generated by these circular shifts induces temporal perturbations that demonstrate the sensitivity of the Hopfield network’s dynamics to neuronal desynchronization, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Phase portraits of the false attractor for the novel Hopfield system (3): (a) projection on the plane; (b) projection on the plane; (c) projection on the plane. Parameter: and initial conditions: .

4. Application to Robotic Path Planning

This section presents the practical application of the proposed Hopfield Neural Network (HNN)-based chaotic system for the control of an autonomous mobile robot’s motion. The primary innovation is the manipulation of chaotic dynamics originating from a single source to produce functionally distinct and highly effective behaviors tailored for three specific robotic tasks: area cleaning, systematic search, and security patrol. This method, referred to as “chaos redirection”, alters the phase space trajectory of the HNN through temporal adjustments in its state variables, resulting in application-specific false attractors. Prior to elaborating on the robot kinematic models and control rules, Figure 6 presents a conceptual overview of our proposed system. The schema demonstrates the utilization of a singular chaotic Hopfield Neural Network, using chaos redirection, to produce three functionally diverse and well optimized robotic actions.

Figure 6.

Control model schematic: Temporal changes turn chaotic HNN dynamics into false attractors, optimizing robotic cleaning, search, and security behaviors.

4.1. Robot Kinematic Model and Control Strategy

The mobile robot is represented as a conventional two-wheeled differential drive system. The position in a 2D Cartesian plane is represented by the vector , where denotes the coordinates and indicates the orientation angle. The motion of the robot is determined by the subsequent kinematic equations:

The linear velocity v and angular velocity are defined in relation to the right wheel velocity (), left wheel velocity (), and the axle length (L):

The primary component of our control strategy involves the direct mapping of states from the generated false attractor, , to the wheel velocities and . At each time step, the instantaneous values derived from the false attractor are utilized to calculate the wheel velocities, resulting in a continuous and non-repeating control signal. The overarching control law is as follows:

In this context, and represent nonlinear functions, such as tanh, applied to the chaotic states. The inclusion of bias terms facilitates continuous forward motion, while the task-specific components are designed to shape the trajectory according to the intended application.

For example, consider the baseline control functions defined as and , accompanied by a forward bias of m/s. At a specific moment t, if the false attractor state is represented as , and the robot is currently in ’Search’ mode (with at this time), the resulting wheel velocities would be

- m/s.

- m/s.

From Equation (15), with an axle length L, a linear velocity of m/s and an angular velocity of rad/s are produced, resulting in a continuous, non-repetitive forward-turning motion.

4.2. Simulation Setup and Parameters

The simulations were carried out using MATLAB (version R2024b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed chaotic controller. The key parameters are detailed below:

- Parameter of Chaotic System: The main bifurcation parameter a in the HNN’s weight matrix () is set at . Based on the bifurcation analysis in Section 2.3 (see Figure 3), this value is carefully selected from the depths of the system’s chaotic regime (where ), providing a robust and fully realized chaotic attractor. The main bifurcation parameter a in the HNN’s weight matrix is set at . The chosen value situates the system in a notably chaotic area, guaranteeing the necessary complexity and responsiveness for the control signals.

To provide a quantitative evaluation of the robot’s performance for each task, the following metrics were calculated:

- Area Coverage: The two-dimensional space is divided into a grid consisting of cells measuring 0.1 m × 0.1 m. This metric quantifies the overall expanse of distinct cells traversed by the robot.

- Coverage Density: This important metric assesses the comprehensiveness of the coverage in the region the robot investigated. The calculation involves determining the percentage of cells that have been visited in relation to the total number of cells contained within the robot’s bounding box, which is defined as the smallest rectangle that encompasses the entire trajectory. The equation is as follows:A high density is advantageous for cleaning and security operations:

- Average Visits per Accessed Cell: This statistic, derived from the relevant literature, reflects the rate of re-visitation. The calculation involves averaging the frequency with which the robot entered each cell that it visited at least once. Elevated values suggest considerable path overlap.

- Unpredictability of Patterns: This metric specifically assesses the randomness of the patrol path taken by the security robot. The calculation involves the coefficient of variation, which is derived by dividing the standard deviation by the mean of the dwell time map for all visited cells. An increased value indicates a more chaotic and unpredictable pattern, making it more challenging for an opponent to foresee.

4.3. Results and Discussion

The chaotic controller’s performance, customized for each specific application, was assessed during a 1000-second simulation period. For all three scenarios, a single, conventional two-wheeled differential drive mobile robot model was used, keeping all physical parameters (e.g., axle length, wheel radius) constant. The differentiation in behavior was achieved exclusively through the software-based control law, specifically by altering the “task_component(t)” term in Equation (15). This highlights the system’s flexibility, where functionally distinct behaviors are generated from the same chaotic core and physical platform simply by applying a lightweight, task-specific signal. The quantitative results are presented in Table 2. These values represent the mean () and standard deviation () obtained from N = 25 independent simulation runs for each task, each lasting 1000 s and initiated with randomized initial conditions . This statistical validation ensures the robustness of the metrics against sensitivity to initial conditions.

Table 2.

Performance Analysis Summary (Mean ± Std. Dev. for N = 25 Runs).

- Cleaning Robot Analysis

The statistical study (N = 25 runs) confirms that the cleaning robot has a mean Coverage Efficiency of 0.01 m2/m. This illustrates that it maximizes the new area covered per meter traveled, which is the primary goal of an efficient cleaning method. The trajectory displays compact, spiraling patterns, with an average visit count per cell of . This behavior is advantageous for cleaning, as the overlapping paths guarantee comprehensive coverage of the examined area. This dense, overlapping behavior was achieved by defining the task component as a constant angular velocity bias, causing the robot to gently curve. The “task_component(t)” for the left and right wheels were set as small, opposing constants , effectively superimposing a persistent turning motion onto the chaotic velocity commands. This forces the robot into the spiraling, localized patterns ideal for thorough cleaning.

- Search Robot Analysis

The search robot was engineered for forward exploration. The object traversed a mean total distance of 614.66 m, achieving a mean velocity of 0.61 m per second. The low mean visit count per cell (143.22) serves as a favorable metric for this task, indicating that the robot allocated less time to revisiting previously explored regions and more time to exploring new areas. The control component executed a zigzagging maneuver, effectively guiding the robot in a forward, scanning motion. To produce an exploratory, forward-scanning motion, the task component was designed as an oscillatory signal applied differentially to the wheels. Specifically, was a low-frequency sine wave added to the right wheel’s velocity and subtracted from the left’s (, ). This induces a rhythmic, side-to-side turning motion that creates the desired zigzagging trajectory, allowing the robot to cover a wide area efficiently while minimizing overlap.

- Security Robot Analysis

The performance of the security robot demonstrates the effectiveness of boundary-constrained chaotic control. The system achieved a mean Coverage Density of , signifying its effective operation and thorough monitoring of the designated area. The principal effect is the significantly increased mean Visits per Visited Cell, measured at , alongside a strong Pattern Unpredictability score of 1.76. This combination is optimal for security: the robot consistently re-patrols its designated area (high frequency of visits) while doing so in an erratic, non-repetitive manner (high level of unpredictability), which complicates an adversary’s ability to anticipate its location at any future time, all while providing thorough surveillance. The “controlled unpredictability” for the security task was implemented using a repulsive potential field. The “task_component(t)” was designed to be zero unless the robot’s position exceeded a predefined patrol radius . If , the component would activate to steer the robot back towards the center of the patrol zone. This was implemented as a corrective angular velocity proportional to the distance from the boundary, effectively creating an invisible circular wall. This ensures the robot remains strictly confined while allowing its motion within the boundary to be governed entirely by the unpredictable chaotic attractor.

- Critical Analysis of Task-Specific Behaviors

The quantitative results presented in Table 2 are not arbitrary; they directly result from the specific “task component” incorporated into each robot’s control law. The varying behaviors can be analyzed critically as follows:

- Security Robot: The key metric, an average visit count of 672.86, is directly attributable to the repulsive potential field. This border constriction inhibits the chaotic trajectory from growing, compelling it to fold back upon itself. The ongoing folding mechanism results in a remarkably high re-visitation frequency and dense coverage (62.75%) within a limited area (), hence substantiating the “controlled unpredictability” notion, see Figure 7.

Figure 7. Performance analysis of the Security Robot. The plots illustrate the “controlled unpredictability” strategy, where chaotic motion is strictly confined. (Top-Left) The trajectory is highly erratic and non-repeating, maximizing pattern unpredictability (score: 1.76). (Top-Right) The coverage is strictly contained within a defined patrol radius. (Bottom-Left) The concentrated dwell time heatmap indicates an extremely high re-visitation frequency (mean visit count ), ensuring persistent surveillance of the protected zone. (Bottom-Right) The distance plot shows the trajectory folding back upon reaching the boundary, validating the confinement mechanism.

Figure 7. Performance analysis of the Security Robot. The plots illustrate the “controlled unpredictability” strategy, where chaotic motion is strictly confined. (Top-Left) The trajectory is highly erratic and non-repeating, maximizing pattern unpredictability (score: 1.76). (Top-Right) The coverage is strictly contained within a defined patrol radius. (Bottom-Left) The concentrated dwell time heatmap indicates an extremely high re-visitation frequency (mean visit count ), ensuring persistent surveillance of the protected zone. (Bottom-Right) The distance plot shows the trajectory folding back upon reaching the boundary, validating the confinement mechanism. - Search Robot: In contrast, the diminished visit count (143.22) and extensive area coverage () result from the low-frequency sinusoidal component (zigzag motion) overlaying a significant forward bias. This task component actively deters re-visitation by perpetually propelling the robot on a forward, expanded trajectory, so transforming the chaotic signal into an exploring instrument, see Figure 8.

Figure 8. Performance analysis of the Search Robot. The plots demonstrate an expansive strategy designed for maximum area discovery. (Top-Left) The trajectory shows a wide, sweeping path driven by a forward-biased zigzag component. (Top-Right) The coverage plot confirms the robot explores a large, sparse area (mean ). (Bottom-Left) The heatmap reveals low dwell times across most cells, indicating minimal path overlap and high exploratory efficiency. (Bottom-Right) The distance from the origin increases steadily over time, validating the continuous forward progress of the search mission.

Figure 8. Performance analysis of the Search Robot. The plots demonstrate an expansive strategy designed for maximum area discovery. (Top-Left) The trajectory shows a wide, sweeping path driven by a forward-biased zigzag component. (Top-Right) The coverage plot confirms the robot explores a large, sparse area (mean ). (Bottom-Left) The heatmap reveals low dwell times across most cells, indicating minimal path overlap and high exploratory efficiency. (Bottom-Right) The distance from the origin increases steadily over time, validating the continuous forward progress of the search mission. - Cleaning Robot: The robot’s significant unpredictability (2.54) and moderate visitation frequency (166.67) arise from its persistent, swirling bias. In contrast to the security bot, its perimeter is not rigid, permitting exploration. In contrast to the search bot, it does not possess a pronounced forward bias. This equilibrium produces a compact, interlaced, yet non-redundant trajectory optimal for comprehensive exploration of intricate, uneven areas, see Figure 9.

Figure 9. Performance analysis of the Cleaning Robot. The plots illustrate a dense, localized cleaning strategy driven by a constant angular bias. (Top-Left) The trajectory exhibits tight, spiraling paths that naturally overlap. (Top-Right) The area coverage grid highlights the focused operational zone. (Bottom-Left) The dwell time heatmap confirms frequent revisits to cells (mean visit count ) within the core area, ensuring thoroughness. (Bottom-Right) The distance from the origin remains bounded but oscillatory, confirming the localized nature of the path optimized for high coverage density.

Figure 9. Performance analysis of the Cleaning Robot. The plots illustrate a dense, localized cleaning strategy driven by a constant angular bias. (Top-Left) The trajectory exhibits tight, spiraling paths that naturally overlap. (Top-Right) The area coverage grid highlights the focused operational zone. (Bottom-Left) The dwell time heatmap confirms frequent revisits to cells (mean visit count ) within the core area, ensuring thoroughness. (Bottom-Right) The distance from the origin remains bounded but oscillatory, confirming the localized nature of the path optimized for high coverage density.

This analysis illustrates that the “chaos redirection” framework serves not merely as a generator of randomness but as a deterministic engineering instrument for shaping chaotic dynamics into predictable, useful, and specialized behaviors.

4.4. Comparative Performance Analysis

A comparative analysis is provided in Table 3 to situate the proposed work within the wider robotics context. This comparison is qualitative rather than a direct quantitative standard. The cited works [39,41,42] and other sophisticated adaptive control methodologies (e.g., adaptive flux control and hybrid fuzzy-PSO controllers for BLDC motors [46,47]) frequently address distinct issues or employ varying Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) under disparate experimental conditions. This analysis aims to elucidate various design philosophies: the suggested HNN-based controller provides a computationally efficient, mapless solution that excels in producing high-entropy behaviors, a domain not directly tackled by high-fidelity Digital Twin frameworks or deterministic planners.

Table 3.

Comparative Performance Analysis (Qualitative Comparison of Design Metrics).

- Cleaning Robot Comparison

For the Cleaning Robot, the method achieved a statistically significant mean coverage density of 30.66% (N = 25 trials). A direct statistical comparison, such as ANOVA, with methodologies like SMURF [42] is unfeasible due to the divergence in key performance indicators this emphasis is on density, whereas theirs is on cleaning rate (3.33 ) attained via structured path planners (WSCPP) therefore, this approach offers a complementary strategy. It demonstrates superior capability in producing unpredictable, dense patterns that are well-suited for complex or irregular environments, where deterministic paths may prove to be inefficient. The elevated mean number of visits per cell () in this simulation highlights its effectiveness for tasks that necessitate multiple passes to achieve thorough cleaning.

- Search and Optimization Comparison

In the Search domain, this system covered an average area of 7.17 m2, achieving the longest average path of 614.66 m among the three applications. This demonstrates its capacity for thorough research. This methodology differs from sophisticated frameworks like the Digital Twin model proposed by Nezzi et al. [41], which focuses on enhancing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) through high-fidelity, offline simulations. Notwithstanding their effectiveness, simulation-based approaches may face challenges such, as synchronization lag in real-time control applications. The HNN-based controller offers a computationally efficient method that generates effective exploratory behaviors directly on the physical agent.

- Security Robot Comparison

The system achieved a mean pattern unpredictability score of 1.76 (N = 25 runs), calculated using the coefficient of variation in the dwell-time map. Similar to the cleaning task, a direct statistical comparison with the method of Tian et al. [39] is unsuitable, as the studies evaluate distinct KPIs: this research optimizes path entropy (unpredictability = 1.76), whereas theirs minimizes path tracking error (RMSE = 0.0124). The study by Tian et al. [39] utilizes multi-switching chaotic systems for secure path generation, achieving high precision execution. This research, in contrast, emphasizes the optimization of the intrinsic unpredictability within the structure of the path. A score of 1.76 indicates a highly erratic and non-repeating patrol pattern. This development directly affects the robustness of physical security; a predictable, deterministic patrol route can be seen and timed by an adversary, creating a “safe window” for penetration. A high-entropy, non-repetitive chaotic trajectory obstructs dependable computation of any interval, forcing an intruder to potentially traverse the path at any time.

- Comparison with Learning-Based Neural Controllers

A horizontal comparison with other neural network-based path control methods, particularly Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) planners, is also relevant [9]. DRL frameworks demonstrate proficiency in learning optimal policies within specific, complex environments; however, they encounter notable limitations related to computational cost and adaptability. Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agents generally necessitate substantial offline training periods and extensive datasets to achieve convergence, and they frequently encounter difficulties in generalizing to irregular search ranges without undergoing retraining. In contrast, the proposed HNN controller utilizes intrinsic nonlinear dynamics instead of learned weights. It operates as a generator that requires no training and minimal computation. This provides a clear advantage in practical applications: it enables immediate, plug-and-play adaptability to various tasks without the computational delays or data dependencies associated with learning-based neural models.

5. Conclusions

This study presents and validates a new control paradigm, termed “chaos redirection”, which employs a single chaotic Hopfield Neural Network alongside synthetic “false attractors” to produce statistically robust, task-specific robotic behaviors. The simulation analysis produced three main qualitative outcomes. The security robot demonstrated “controlled unpredictability” by being effectively restricted to a compact patrol zone, resulting in a markedly higher frequency of re-visitation relative to exploratory behaviors, thereby validating its appropriateness for continuous surveillance. In contrast, the search robot was optimized for discovery, encompassing the greatest total area at the highest speed while minimizing path overlap, thereby exhibiting maximal exploratory efficiency. The cleaning robot generated distinct, high-entropy paths marked by significant pattern unpredictability, facilitating non-repetitive and comprehensive coverage appropriate for complex or irregular spaces. This study illustrates that actively shaping chaotic dynamics, instead of simply utilizing or suppressing them, serves as an effective and resilient approach for producing a variety of high-performance behaviors in autonomous systems from a singular, integrated control core. This study established performance baselines in obstruction-free zones to validate the core “chaos redirection” mechanism in operational environments. The inherent characteristics of the produced behaviors indicate significant robustness in complex, real-world situations. Future research will expand this framework to include cluttered environments, examining the hypothesis that the high-entropy “Cleaning” behavior can effectively navigate irregular obstacles and non-convex search areas, avoiding the local minima entrapment commonly seen in deterministic potential field methods.

Author Contributions

Project administration, software (MATLAB R2024b), writing—original draft preparation, methodology, F.Z.; and Formal analysis, writing—review and editing, validation, C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hopfield, J.J. Neurons with graded response have collective computational properties like those of two-state neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 3088–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danca, M.-F.; Kuznetsov, N. Hidden chaotic sets in a Hopfield neural system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2017, 103, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. From Kuramoto to Crawford: Exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2000, 143, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C. Some simple chaotic flows. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, R647–R650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dong, X. From chaos to order—Perspectives and methodologies in controlling chaotic nonlinear dynamical systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1993, 3, 1363–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; He, T.; He, S.; Tan, B.; Shi, C.; Lin, H. Influence of Memristive Activated Gradient on Chaotic Dynamics in Discrete Neural Networks. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 2025, 35, 2550146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Aihara, K. Memristive Hopfield Networks: Enhancing Chaotic Dynamics for Neuromorphic Control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, W.; Zheng, Q.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S. Path Planning of Mobile Robot in Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance Environment Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 189136–189148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusree, M.; Pramod, P.N. Understanding chaotic neural networks: A comprehensive review. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 25389–25404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Tan, K.K. Multistability of discrete-time recurrent neural networks with unsaturating piecewise linear activation functions. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2004, 15, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, D.S.; Munoz-Pacheco, J.M.; Felix-Beltran, O.G.; Volos, C. Rich dynamics and analog implementation of a Hopfield neural network in integer and fractional order domains. Integration 2025, 103, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskaridis, L.; Volos, C.; Bardis, N. Hidden Coexisting Firing Patterns in a Hindmarsh-Rose Neuron Model with the Simplest Memristor. WSEAS Trans. Circuits Syst. 2025, 24, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaamoune, F.; Tinedert, I.E.; Abro, K.A.; Faizan, M. A Novel Approach to Structured Multistability in a 3D Chaotic System: Implementation and Circuit Validation. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Networks Devices Fields 2025, 38, 70123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volos, C.K.; Kyprianidis, I.M.; Stouboulos, I.N. T Antimonotonicity, hysteresis and coexisting attractors in a Shinriki circuit with a physical memristor as a nonlinear resistor. Electronics 2022, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Gu, H.; Bai, J.; Wu, F. Bifurcation and chaos of spontaneous oscillations of hair bundles in auditory hair cells. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2021, 31, 2130011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.; Yu, W.; Moroz, I.; Volos, C. Constructing conditional symmetry in a chaotic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 3857–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z. Dynamic analysis and sliding mode synchronization control of chaotic systems with conditional symmetric fractional-order memristors. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M.G.; Pikovsky, A.S.; Kurths, J. From Phase to Lag Synchronization in Coupled Chaotic Oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4193–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Lou, J.; Lu, J.; Shi, K. Synchronization of chaotic neural networks: Average-delay impulsive control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 6007–6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Hu, G. Clustering dynamics in globally coupled map lattices. Phys. Rev. E 1997, 41, 137–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volos, C.K.; Kyprianidis, I.M.; Stouboulos, I.N. Image encryption process based on a chaotic synchronization phenomenon. Signal Process. 2012, 92, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.J.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.T. Hyperchaotic secure communication via generalized function projective synchronization. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2012, 12, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaamoune, F.; Tinedert, I.E.; Menacer, T.; Wang, N. Multistability and multi-spiral chaotic sea in a novel 3-D system with a line of equilibrium. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 035226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaamoune, F.; Tinedert, I.E.; Menacer, T. Analysis of novel 3D chaotic system, hidden coexisting, adaptive control, offset boosting control, and circuit implementation. Eur. J. Control 2025, 84, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, M.A.; Leys, J.; Bouali, S. Discovering the beauty of false strange attractors. Cantor’s Paradise 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysis, L.; Lawnik, M.; Maraslidis, G.S.; Fragulis, G.F.; Volos, C. False Strange Attractors as Sources of Pseudo Randomness. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 085217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkov, A.L. Control of chaos: Methods and applications in mechanics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006, 364, 2279–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, G. Controlling chaos in an economic model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2007, 374, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y.; Makaraci, M. Exploring advancements and emerging trends in robotic swarm coordination and control of swarm flying robots: A review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2025, 239, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktas, A.; Erkan, U.; Ustun, D. An image encryption scheme based on an optimal chaotic map derived by multi-objective optimization using ABC algorithm. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 5, 1885–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S. Efficient image or video encryption based on spatiotemporal chaos system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2009, 40, 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bao, L.; Chen, C.P. A new 1D chaotic system for image encryption. Signal Process. 2014, 97, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaletti, S.; Grebogi, C.; Lai, Y.-C.; Mancini, H.; Maza, D. The control of chaos: Theory and applications. Phys. Rep. 2000, 329, 103–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-C. Controlling chaos. Comput. Phys. 1994, 268, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xi, X.; Liu, J. Dynamical analysis, feedback control circuit implementation, and fixed-time sliding mode synchronization of a novel 4D chaotic system. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. Control of chaos using sampled-data feedback control. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1996, 8, 2433–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Chen, C.L.; Yau, H. Control of chaos in Lorenz system. Int. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2002, 13, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.W.; Alattas, K.A.; Guo, W.; Taghavifar, H.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. A strong secure path planning/following system based on type-3 fuzzy control, multi-switching chaotic systems, and random switching topology. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 1997–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durey, M. Bifurcations and chaos in a Lorenz-like pilot-wave system. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2020, 30, 103115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezzi, C.; De Marchi, M.; Vidoni, R.; Rauch, E. A Multi-Purpose Simulation Layer for Digital Twin Applications in Mechatronic Systems. Machines 2025, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y. SMURF: A Fully Autonomous Water Surface Cleaning Robot with A Novel Coverage Path Planning Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joon, A.; Kowalczyk, W. Design of Autonomous Mobile Robot for Cleaning in the Environment with Obstacles. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, M.; Li, F.; Ahmad, S.; Wang, N. Mixed obstacle avoidance in mobile chaotic robots with directional keypads and its non-identical generalized synchronization. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, E.; Meena, G.D. Mimicking Lorenz attractor behavior in a simple linear single-leg hopping robot. Chaos 2025, 35, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kethiri, M.F.; Charrouf, O.; Betka, A.; Tibermacine, I.E.; Napoli, C. Hybrid fuzzy-PSO based self-tuning fractional order PI controller for BLDC motors in electric vehicles: Comparative analysis and experimental validation. J. Vib. Control 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kethiri, M.F.; Charrouf, O.; Betka, A.; Salman, M.; Boccaletti, C. Minimizing Power Losses in BLDC Motor Drives Through Adaptive Flux Control: A Real-Time Experimental Study. Actuators 2025, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).