Effects of Sports Flooring on Peak Ground Reaction Forces During Bilateral Drop Landings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

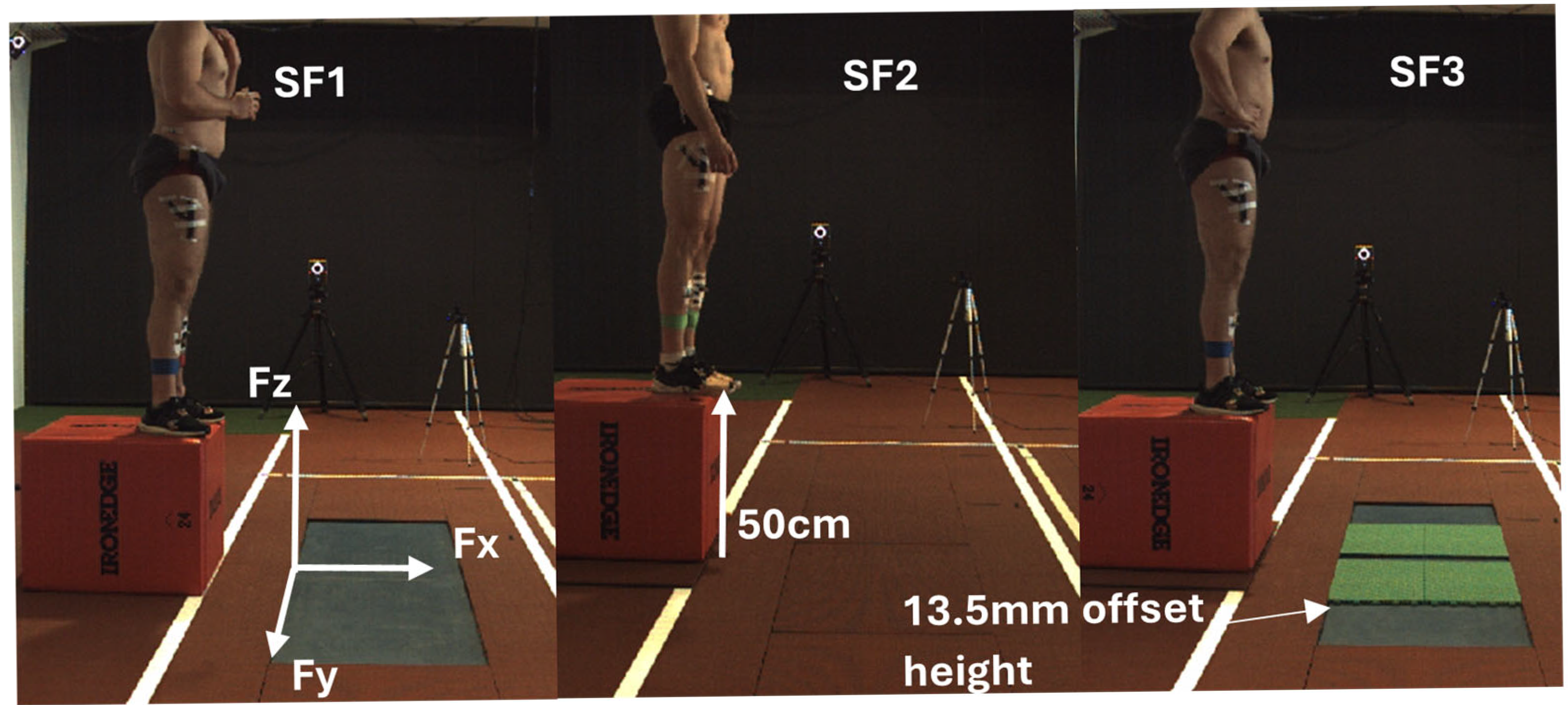

2.2. Testing Procedure and Protocol

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Main Effect of Flooring Type

3.2. Main Effect of Limb

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical GRF Landing Symmetry

4.2. Anterior, Posterior, and Lateral GRFs

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stiles, V.; Dixon, S. Sports Surfaces, Biomechanics and Injury. In The Science and Engineering of Sport Surfaces; Dixon, S., Fleming, P., James, I., Carre, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoo, J.L.; Braun, H.J. The effect of playing surface on injury rate: A review of the current literature. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.; Hume, P.A.; Kara, S. A review of football injuries on third and fourth generation artificial turfs compared with natural turf. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 903–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, L.; Kocaoglu, B.; Cole, B.; Arundale, A.J.; Bytomski, J.; Amendola, A. (Eds.) Basketball Sports Medicine and Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, D.L.; Murphy, K.M.; Nicoll, J.X.; Sullivan, W.M.; Henderson, J. Effects of different athletic playing surfaces on jump height, force, and power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malisoux, L.; Gette, P.; Urhausen, A.; Bomfim, J.; Theisen, D. Influence of sports flooring and shoes on impact forces and performance during jump tasks. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186297. [Google Scholar]

- Cismaru, I.; Filipașcu, M.; Fotin, A. Wooden flooring—Between present and future. Pro Ligno 2015, 11, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Turcas, O.M.; Fotin, A. The evolution and the characteristics of wooden flooring for gym and sport courts. Pro Ligno 2017, 13, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A.; Whiteley, R.; Bleakley, C. Higher shoe-surface interaction is associated with doubling of lower extremity injury risk in football codes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krosshaug, T.; Nakamae, A.; Boden, B.P.; Engebretsen, L.; Smith, G.; Slauterbeck, J.R.; Hewett, T.E.; Bahr, R. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: Video analysis of 39 cases. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. Modelling and analysis of alternative “tile to tile” attachment mechanism designs, for a modular plastic tile sports surface using FEA. Procedia Eng. 2016, 147, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Tang, Y. Shock absorption properties of synthetic sports surfaces: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 2954–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heebner, N.R.; Rafferty, D.M.; Wohleber, M.F.; Simonson, A.J.; Lovalekar, M.; Reinert, A.; Sell, T.C. Landing kinematics and kinetics at the knee during different landing tasks. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, F.; Lewis, M.; Lopes, H.; Fonseca, E.M. An evaluation of the accuracy and precision of jump height measurements using different technologies and analytical methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, S.; Antonacci, G.; Marinelli, S.; Cifelli, P.; Di Giminiani, R. The acute effect of verbal instructions on performance and landing when dropping from different heights: The ground reaction force-time profile of drop vertical jumps in female volleyball athletes. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1474537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianasab, H.; Mohammadipour, F.; Amiri-Khorasani, M. Comparison of knee joint kinematics during a countermovement jump among different sports surfaces in male soccer players. Sci. Med. Football 2017, 1, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, A.; Stefanescu, A.; Bosio, A.; Riggio, M.; Rampinini, E. The cost of running on natural grass and artificial turf surfaces. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, N.; Morrison, S.; Van Lunen, B.L.; Onate, J.A. Landing technique affects knee loading and position during athletic tasks. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, N.; Onate, J.; Abrantes, J.; Gagen, L.; Dowling, E.; Van Lunen, B. Effects of gender and foot-landing techniques on lower extremity kinematics during drop-jump landings. J. Appl. Biomech. 2007, 23, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, J.; Zehetner, J.; Klien, S.; Ausserer, F.; Velkavrh, I. Production and tribological characterization of tailored laser-induced surface 3D microtextures. Lubricants 2019, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardo, A.; Costagliola, G.; Ghio, S.; Boscardin, M.; Bosia, F.; Pugno, N.M. An experimental-numerical study of the adhesive static and dynamic friction of micro-patterned soft polymer surfaces. Mater. Des. 2019, 181, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.V.; Corazza, S.; Chaudhari, A.M.; Andriacchi, T.P. Shoe-surface friction influences movement strategies during a sidestep cutting task: Implications for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, B.M.; Stefanyshyn, D.J.; Rozitis, A.I.; Mündermann, A. Resultant knee joint moments for lateral movement tasks on sliding and non-sliding sport surfaces. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias Bocanegra, J.M.; Fong, D.T. Playing surface traction influences movement strategies during a sidestep cutting task in futsal: Implications for ankle performance and sprain injury risk. Sports Biomech. 2022, 21, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.V.; Andriacchi, T.P. The Role of Shoe-Surface Interaction and Noncontact ACL Injuries. In ACL Injuries in the Female Athlete: Causes, Impacts, and Conditioning Programs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross, M.F.; Johnson, S.T.; Bovbjerg, V.E.; Koester, M.C.; Hoffman, M.A. Factors influencing high school coaches’ adoption of injury prevention programs. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 16, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talia, A.J.; Busuttil, N.A.; Kendal, A.R.; Brown, R. Gender differences in foot and ankle sporting injuries: A systematic literature review. Foot 2024, 60, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talia, A.J.; Busuttil, N.A.; Hotchen, A.; Kendal, A.R.; Brown, R. Sex Differences in Foot and Ankle Sports Injury Rates in Elite Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 25,687,866 Athlete Exposures. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2025, 13, 23259671251364261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navacchia, A.; Bates, N.A.; Schilaty, N.D.; Krych, A.J.; Hewett, T.E. Knee abduction and internal rotation moments increase ACL force during landing through the posterior slope of the tibia. J. Orthop. Res. 2019, 37, 1730–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.C.; Neptune, R.R.; van den Bogert, A.J.; Nigg, B.M. The influence of foot positioning on ankle sprains. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, D.G.; Goodman, D. Effects of visual guidance on the reduction of impacts during landings. Ergonomics 1991, 34, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNitt-Gray, J.L. Kinetics of the lower extremities during drop landings from three heights. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donelon, T.A.; Edwards, J.; Brown, M.; Jones, P.A.; O’Driscoll, J.; Dos’ Santos, T. Differences in biomechanical determinants of ACL injury risk in change of direction tasks between males and females: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med.-Open 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, B.M.; Liu, W. The effect of muscle stiffness and damping on simulated impact force peaks during running. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Collop, A.C.; Batt, M.E. Surface effects on ground reaction forces and lower extremity kinematics in running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bare Force Plate | Athletic Track | Modular Tiles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Reaction Forces (N·Kg−1) | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right |

| ab Anterior | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| Posterior | −2.8 ± 1.1 | −3.1 ± 1.0 | −2.8 ± 0.9 | −3.6 ± 0.7 | −2.4 ± 0.6 | −2.9 ± 0.9 |

| b Lateral | −2.7 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | −2.8 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | −2.6 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

| b Vertical | 24.4 ± 2.9 | 28.9 ± 3.5 | 24.4 ± 2.5 | 30.6 ± 3.1 | 23.8 ± 2.7 | 27.4 ± 2.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Busuttil, N.A.; Dunn, M.; Roberts, A.H.; Viglione, A.J.; Middleton, K.J. Effects of Sports Flooring on Peak Ground Reaction Forces During Bilateral Drop Landings. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122045

Busuttil NA, Dunn M, Roberts AH, Viglione AJ, Middleton KJ. Effects of Sports Flooring on Peak Ground Reaction Forces During Bilateral Drop Landings. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122045

Chicago/Turabian StyleBusuttil, Nicholas A., Marcus Dunn, Alexandra H. Roberts, Anthony J. Viglione, and Kane J. Middleton. 2025. "Effects of Sports Flooring on Peak Ground Reaction Forces During Bilateral Drop Landings" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122045

APA StyleBusuttil, N. A., Dunn, M., Roberts, A. H., Viglione, A. J., & Middleton, K. J. (2025). Effects of Sports Flooring on Peak Ground Reaction Forces During Bilateral Drop Landings. Symmetry, 17(12), 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122045