Abstract

When trained on long-tailed distributions, deep neural networks often suffer performance degradation and model bias due to the dominance of head classes. Existing reweighting and sampling strategies have significant limitations, such as reliance on fixed heuristics and inability to adapt to dynamic sample difficulty and class imbalance. Additionally, they fail to integrate sample-level granularity with class-level balance, further inadequately addressing the global imbalance issue. Motivated by these challenges, we introduce the Progressive Hierarchical Adaptation for Sample-Efficient rebalancing (PHASE) training framework, which employs a double-layer tuning paradigm to optimize performance under long-tailed distributions. Specifically, the double-layer tuning paradigm adopted by PHASE runs as follows: (1) an early-stage difficulty-aware mechanism targets those difficult-to-classify samples to guide representation learning; and (2) a later-stage multi-scale reweighting strategy integrates class distribution statistics with sample characteristics. This method ensures fine-grained adaptability and global balance, and thus outperforming those static or localized techniques. Extensive experiments on CIFAR10-LT, CIFAR100-LT, and ImageNet-LT datasets demonstrate that PHASE can significantly improve the accuracy of tail classes without degenerating head class performance, and acquire state-of-the-art classification results. PHASE provides a novel paradigm for long-tailed image recognition.

1. Introduction

In recent years, deep neural networks have made significant advancements in various computer vision tasks, such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. These advancements have been largely attributed to the availability of meticulously annotated [,,] and well-balanced benchmarks like ImageNet [], COCO [], and Places []. These datasets play a crucial role as they provide a solid training foundation with evenly distributed classes and ample samples, facilitating the learning of comprehensive and transferable feature representations by the models. However, real-world data typically exhibit a long-tailed distribution, where a small number of classes (head classes) contain the majority of samples, leaving the remaining classes (tail classes) significantly under-represented. This class imbalance leads to a bias in training, where standard models tend to prioritize learning the dominant head classes, resulting in skewed decision boundaries and declined performance on the under-sampled tail classes. This bias poses a particular challenge in critical domains like medical diagnosis [] and autonomous driving [], where misclassification or neglect of rare yet crucial categories can have severe consequences. To tackle this issue, researchers have explored various strategies, including advanced data augmentation methods, class-aware resampling techniques, and specific loss function designs. The objective of these approaches is to enhance recognition rates for minority classes while maintaining overall accuracy levels.

The most commonly utilized technique for addressing class imbalance in machine learning is resampling, which involves adjusting the class distributions in training data through either under-sampling the majority classes or over-sampling the minority classes. Despite its popularity, resampling has notable limitations: under-sampling can diminish the diversity and generalization capabilities of the majority classes, while over-sampling may result in overfitting the minority classes [].

In contrast to resampling, reweighting presents a more direct and computationally efficient solution by assigning varying weights to the training loss of each class, thereby adjusting their relative importance during training. Traditional reweighting methods typically employ fixed weight allocation strategies based on the sample sizes of each class []. However, these static weights do not meet the dynamic training requirements of learning models, thereby constraining the adaptability and generalization of the model.

Motivated by aforementioned issue, we present a novel dynamic reweighting framework called Progressive Hierarchical Adaptation for Sample Effective rebalancing (PHASE) which is specifically designed to meet the challenges associated with long-tailed data distributions. PHASE adaptively tunes the weights of both head and tail classes throughout the entire training process for ensuring that each class is sufficiently represented. By dynamically balancing the contributions of both majority and minority classes, PHASE effectively lowers the inherent biases in long-tailed datasets, further enhancing overall performance and robustness of the learning model. Extensive experiments on three benchmark long-tailed image recognition datasets demonstrate that the proposed PHASE framework significantly improves recognition accuracy for tail classes, and meanwhile, improves the generalization of the overall model. It successfully overcomes the limitations of traditional resampling and static reweighting techniques, and provides a robust and extended solution for treating long-tailed data learning issues.

Three main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- By combining sample-level difficulty tuning with class-level weight allocation, PHASE systematically reconfigures optimization strategies tailored for long-tailed scenarios. Theoretically, PHASE achieves dynamic adaptation of local weights and equilibrium of global weights, creating a multi-stage, multi-scale adaptive optimization system that enhances learning model performance on long-tailed datasets.

- (2)

- In the initial phase, PHASE incorporates a dynamic tuning factor utilizing sample prediction probabilities to establish a Difficulty-Aware Weighting (DAW) framework. This framework enables the adjustment of the learning impact of individual samples, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to the intricate sample distributions of tail classes. It actively redirects the trajectory of representation learning, further constructing a more robust feature space. In the second phase, a Multi-Scale Reweighting (MSR) approach is introduced. MSR integrates statistical patterns obtained from class distributions with the intrinsic data characteristics of each class. This approach effectively merges local and global class weight assignments, dynamically balancing the optimization paths of head and tail classes. It alleviates the adverse effects of weight competition-induced negative transfer between classes.

- (3)

- Extensive experiments are performed on three commonly utilized long-tailed datasets: CIFAR10-LT, CIFAR100-LT, and ImageNet-LT. The results indicate that PHASE outperforms existing state-of-the-art long-tailed reweighting approaches in terms of both overall classification accuracy and tail class recognition accuracy. Moreover, when integrated with data augmentation methods, PHASE achieves better or comparable accuracy than/to those of the current state-of-the-art techniques, indicating its efficacy and superiority in addressing tasks involving imbalanced data distributions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews some previous work closely associated with this study, including reweighting methods and decoupling representation techniques. In Section 3, we describe the proposed method in detail. Section 4 provides the experimental results and the corresponding analysis to verify the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method. Finally, Section 5 concludes this study.

2. Related Work

2.1. Reweighting

Reweighting methods generally involve two different types: loss weighting and logit adjustment. Loss weighting balances the model’s focus between head and tail classes by assigning different loss weights to samples belonging to different classes. Such methods include Class-Balance Loss [], which uses the number of samples as weights, and Focal Loss [], which emphasizes those difficult-to-learn samples by adjusting weights based on prediction probabilities. Logit adjustment techniques [], on the other hand, allocate larger margins to tail classes, further alleviating imbalance. Additionally, methods such as Label-Distribution-Aware Margin (LDAM) loss [], which enforces class-dependent margins, and Vector-Scaling (VS) loss [], which combines additive and multiplicative logit adjustments, have also been proposed. These reweighting strategies effectively reduce bias towards head classes and improve classification performance of tail classes.

2.2. Decoupling Representation

Recent advancements in long-tailed visual recognition have emphasized using decoupling representation learning to enhance performance. The first method in such type, LDAM-DRW [], adopts a two-phase training strategy, in which the first phase concentrates on learning robust feature representations, and the second phase employs delayed reweighting to refine decision boundaries. This approach significantly improves long-tailed prediction accuracy, although its underlying mechanisms could not be fully understood at that time. The foundational work on decoupled training [] introduced this double-stage framework, and explained how it is different from traditional end-to-end paradigms. In the initial phase, various sampling strategies are empirically tried to search the most effective one for representation learning. In the second phase, the feature extractor is first fixed, and then different training strategies are evaluated and compared. Results indicate that the best choice is to use random sampling for optimizing representation learning and classifier re-adjustment as the training strategy, as this combination can significantly improve long-tailed recognition performance.

Based on these findings, MiSLAS [] has been proposed. It adopts data augmentation by mix-up techniques in the first phase to strengthen representation learning, and employs a label-aware smoothing strategy in the second phase to improve classifier generalization. The improvements on both stages help to yield superior classification performance on long-tailed datasets. More recent studies have further refined the classifier training phase to alleviate specific challenges induced by long-tailed distributions. For example, SimCal [] proposed a double-layer class balancing sampling strategy for dealing with long-tailed instance segmentation issue. It is helpful for calibrating the classification head and reinforcing the classifier training procedure.

These strategies have consistently shown superior classification performance on the aforementioned long-tailed datasets. To more clearly situate our proposed PHASE framework within the existing landscape and highlight its unique contributions, we provide a comparative summary of main characteristics between PHASE and several representative state-of-the-art methods [,,,] in Table 1.

Table 1.

A comparative summary of main characteristics between PHASE and several representative state-of-the-art methods.

As illustrated in Table 1, while existing methods often focus on a single aspect—such as sample difficulty (Focal Loss [], SURE []), class-level margins (LDAM-DRW []), or intra-class distribution (AREA [])—the PHASE framework is uniquely designed to systematically and explicitly integrate these complementary strategies in a progressive manner.

Unlike LDAM-DRW [], which applies a static margin and delayed reweighting, PHASE introduces a dynamic, sample-level difficulty-aware weighting in the first stage to guide a more robust representation learning.

Unlike AREA [], which uses a fixed feature distribution for reweighting in the second stage, PHASE proposes a multi-scale reweighting strategy that combines global class imbalance statistics with local, dynamic intra-class characteristics.

This progressive hierarchical adaptation—first refining features by sample difficulty, then refining the classifier by both class and intra-class balance—constitutes the novel contribution of PHASE, enabling a more fine-grained and effective handling of long-tailed distributions.

3. Methods

In this section, we introduce PHASE that is a novel approach designed to address long-tailed distributions issue in visual recognition tasks. Specifically, PHASE comprises two core components: DAW and MSR. Section 3.1 describes the primary challenges of long-tailed learning, followed by detailed descriptions of DAW in Section 3.2 and MSR in Section 3.3.

3.1. Preliminaries

The most critical challenge in long-tailed learning lies in effectively learning under inherently imbalanced class distributions. Consider a training set composed of samples, where each sample associates with a label . If the dataset exhibits a highly imbalanced class distribution , where denotes the number of training instances in the -th class, and typically the classes with fewer samples are less represented than those with more samples, it is considered a long-tailed dataset. This imbalance poses significant challenges to conventional training paradigms. The large discrepancy in the number of samples across different classes leads to representation biases, making learning models focus more on the head classes, but neglect the tail classes. To address the core challenges in long-tailed learning outlined above, we propose the PHASE framework. It is built on a progressive hierarchical adaptation paradigm, whose core idea is to decouple and sequentially optimize two critical aspects: robust feature representation learning and balanced classifier calibration.

3.2. Difficulty-Aware Weighting Framework

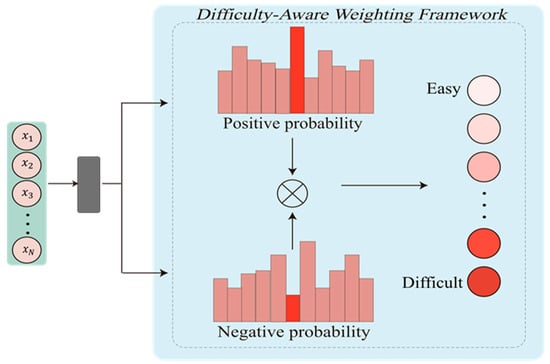

We propose DAW framework that prioritizes those challenging instances during representation learning. Inspired by asymmetric focal-like paradigms [], the DAW framework reduces the weights of easily classified samples and meanwhile, emphasizes those more difficult ones, thereby providing valuable information for later training. By adaptively tuning weights based on sample recognition difficulty level, it lays a solid foundation for further weight optimization at second stage, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The difficulty-aware module dynamically guides representation learning to construct a robust feature space.

The model predicts a probability distribution satisfying the condition of , where denotes the predicted probability that belongs to the class . Then it can be used to calculate the following asymmetric loss (‘ASL’):

where and represent dynamic weights for positive and negative samples, respectively. These weights can be defined as:

where and are hyper-parameters which are used to control the degree of gradient decay. The positive sample weight decreases with the increase in , which can be used to lower the contribution of easily classified samples, while the negative sample weight reduces for small , which can be used to avoid excessive penalties on well-separated negative samples. To unify the gradient tuning mechanism for both positive and negative samples, we introduce a weight correction function as follows:

where is an indicator function that is used to distinguish positive samples and negative samples . With , the ASL Loss can be rewritten as:

where is the one-hot label distribution of . To further improve the model’s robustness to tail-class samples and label noise, we also adopt the label smoothing technique to transform the one-hot label into a smoothed distribution as follows:

where is the smoothing parameter that is used to balance the probabilities between the real class and other classes. By incorporating label smoothing, the final loss function can be expressed as:

The optimization objective for the first stage is then defined as:

where represents the training dataset used at the first stage. After finishing the training of the first stage, the model parameters have been optimized, and would be then fixed to provide stable feature representations for the second stage.

The complete procedure of the proposed ASL-based Difficulty-Aware Weighting (DAW) is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: DAW |

| Input: Training set , the number of classes C, the positive and negative focusing parameters γ+, γ−, the label smoothing parameter ϵ |

| Output: Optimized feature extractor parameters |

| Procedure: |

| 1. Initialize the model with γ+, γ− and ϵ; |

| 2. Define the log-softmax function for output normalization; |

| 3. For each training instance (xi,yi) (a) Calculate predicted class probabilities p(xi) using softmax; (b) Generate one-hot label vector ti,j; (c) Calculate asymmetric weights A(xi,j) as defined in Equation (3); (d) Apply label smoothing to obtain smoothed labels according to Equation (5); |

| 4. Aggregate the instance-wise losses to obtain the final loss Lfinal; |

| 5. Optimize model parameters by minimizing the expected loss on as defined in Equation (7). |

3.3. Multi-Scale Reweighting

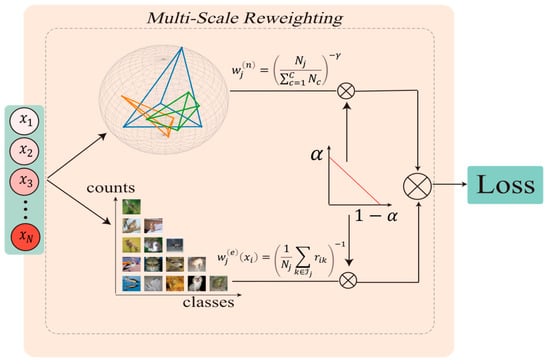

In long-tailed distributions, relying solely on static reweighting based on sample quantities always fails to adequately capture the complex intra-class feature distributions. To address this issue, we propose a Multi-Scale Reweighting (MSR) method and conduct it at the second stage of training. Specifically, MSR combines global weights tuning based on sample quantities with local dynamic weights tuning based on the effective area [], which is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The weight allocation mechanism combines class distribution statistics with sample characteristics to balance the optimization between head and tail classes.

Both tunings are conducted at the class level to dynamically determine the integrated weight of each sample for enhancing the learning quality of tail classes. First, to address the imbalance issue existing in sample quantities among classes, we define a global tuning weight to balance the contributions of different classes. Let denote the number of samples in class , and represent the number of classes. The global tuning weight can be defined as follows:

where is a hyperparameter that is used to control the sensitivity of the weight distribution to sample quantities. This formulation is inspired by the concept of effective number of samples []. The parameter governs the trade-off between alleviating head-class bias and maintaining training stability. As , , the loss reduces to a standard balanced loss, treating all classes equally but failing to address the imbalance. As , the weight for the smallest class becomes excessively large, which may lead to overfitting on tail classes and instability. Thus, an appropriate is chosen to smoothly amplify the gradient contributions of tail classes during backpropagation without causing divergence. Here, classes with fewer samples (i.e., tail classes) are generally assigned larger weights to amplify their contributions to the overall optimization. Furthermore, the global weight should be normalized as:

Although the global tuning alleviates inter-class imbalance, it cannot fully capture the diversity within each class. To model the discrepancy among intra-class distributions, we further introduce a local dynamic tuning mechanism based on the similarity among samples within each class. Using the feature extractor that has been fixed at the first stage, we compute the feature representation of a sample , denoted as . For a specific class , the class feature center is calculated by:

where is the set of indices for indicating which samples belong to the class . Based on the feature deviation , the similarity between a sample and another sample within the same class can be calculated as follows:

where denotes the Euclidean norm. By using these similarity scores, the local dynamic tuning weight for the sample is defined as:

This equation highlights those samples which deviate more significantly from the class center or have weaker relationships with other samples, making the model better handle the diverse feature distribution within each class. To combine global tuning and local dynamic tuning, we define the integrated class-level weight as:

where is an tradeoff factor that controls the relative contributions of global and local weight tunings. The convex combination in Equation (13) is crucial for stability. The factor balances trust between global class-level statistics and local sample-level characteristics. Setting = 1 relies solely on robust global statistics but may ignore intra-class diversity. Setting = 0 focuses entirely on intra-class similarity, which might be sensitive to feature noise. A value harnesses the complementary strengths of both. Importantly, this formulation ensures the integrated weight is bounded, i.e., , preventing gradient explosion or vanishing that could arise from uncontrolled weight scaling, thereby enhancing training stability. At the second stage of training, the model uses the integrated weight to optimize the classifier. The objective function is defined as:

where represents the cross-entropy loss. The loss function in Equation (14) is a weighted empirical risk minimization. Since the feature extractor is fixed in stage two, the weights are positive and bounded scalars determined prior to classifier training. Given that the cross-entropy loss is smooth and differentiable with respect to the classifier parameters , the gradient of remains Lipschitz continuous. Therefore, when optimized using standard stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with a suitable learning rate schedule (as in Section 4.1), the training process is expected to converge to a stationary point [,], consistent with the convergence guarantees of the underlying optimizer. The role of MSR is to reshape the loss landscape for more balanced learning without altering these fundamental convergence properties. By integrating the global weight tuning based on sample quantity with the local weight tuning based on intra-class similarity, MSR can effectively enhance the learning quality of tail classes, and meanwhile preserve the diversity within class distributions, helping achieve a more balanced optimization for long-tailed distributions.

The procedure of the proposed MSR algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: MSR |

| Input: Training set ; the sample counts of each class ; the feature extractor ; the hyper-parameter γ > 0; the tradeoff factor |

| Output: The integrated class-level weights |

Procedure:

|

4. Experiments

In this section, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of the proposed PHASE framework on three widely used long-tailed image classification benchmark datasets: CIFAR10-LT, CIFAR100-LT, and ImageNet-LT. These datasets exhibit varying degrees of class imbalance and serve as standard benchmarks for assessing the robustness and generalization capabilities of long-tailed learning approaches. To gain a deeper understanding of the specific contributions of each component within the PHASE framework, we also performed extensive ablation studies. These analyses enable us to independently assess the impact of individual modules and investigate the interactions between different components, offering valuable insights into the internal mechanisms and design decisions of the PHASE framework. Furthermore, we conducted comparative evaluations against several state-of-the-art long-tailed learning methods. The comparative results show the efficacy of our proposed approach across datasets with diverse levels of class imbalance, thereby confirming the superior performance of PHASE in addressing real-world long-tailed recognition tasks.

4.1. Experiment Settings

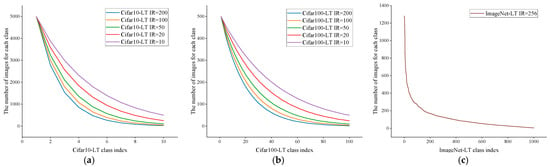

To assess our proposed approach thoroughly, we initially generated various long-tailed versions from both CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using an exponential decay sampling method [] applied to the original balanced datasets. An imbalance factor (IF ) was defined, in where and represent the sample counts in the most and least represented classes, respectively. By adjusting the IF, we could precisely manage the degree of imbalance in the resulting dataset. Subsequently, CIFAR10-LT (Figure 3a) and CIFAR100-LT (Figure 3b) each produced five training subsets with varying imbalance ratios in . Furthermore, we utilized ImageNet-LT (Figure 3c), a subset of the ImageNet dataset comprising 200 classes and 100,000 images resized to 64 64 pixels. ImageNet-LT demonstrates an imbalance factor of 256, providing a more demanding benchmark for assessing the resilience and generalization capabilities of the proposed method. Detailed information regarding these long-tailed datasets is available in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Class-wise image distributions of three long-tailed benchmark datasets: (a) Cifar10-LT, (b) Cifar100-LT, and (c) ImageNet-LT. Each curve represents the number of images per class under a specific imbalance ratio (IR). The figure illustrates the severity of class imbalance, where head classes contain significantly more samples than tail classes.

Table 2.

The detailed information of the used long-tailed datasets.

In our experiments, all models were trained using the PyTorch (v2.0.1) framework [] on a GeForce RTX 3090 GPU(NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). We utilized the ResNet-32 architecture as the backbone for training on both CIFAR10-LT and CIFAR100-LT datasets, following the configuration specified in []. The models were trained for 200 epochs using standard SGD with a momentum of 0.9 and weight decay . The initial learning rate was 0.1 with a linear warmup schedule [], which was subsequently reduced to at epoch 160 and further decreased to at epoch 180 to facilitate convergence. For experiments on the ImageNet-LT dataset, we employed ResNet-50 as the backbone, with an initial learning rate of 0.1 and weight decay of . To ensure fair comparisons with baseline methods, consistent data augmentation techniques such as random horizontal flipping and random cropping were applied to all models.

4.2. Long-Tailed Benchmark Results

To validate the effectiveness and superiority of our proposed method, we conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on multiple long-tailed image recognition datasets. Given the rapid advancements in this field, we selected various state-of-the-art methods for comparison, including single-stage reweighting methods and double-stage decoupled representation approaches. For instance, the Class-Balanced Loss method [] adjusts the loss function by inversely weighting it based on the effective number of samples, thus ensuring a balanced training influence across different classes. In contrast, methods like LDAM-DRW [] and AREA [] employ a double-stage training approach, which consists of initial training followed by subsequent rebalancing, aiming to improve classification performance on long-tailed datasets. These strategies have consistently shown superior classification performance on the aforementioned long-tailed datasets.

It is notable that methods utilizing double-stage decoupled representation strategies exhibit a closer association with our PHASE approach. We conducted extensive experiments on the CIFAR10-LT and CIFAR100-LT datasets to assess the performance of our method, PHASE, in comparison to several state-of-the-art baseline approaches [,,,,,], across five different imbalance factors (10, 20, 50, 100, 200). Table 3 displays the Top-1 accuracy of each approach on these datasets. The results of our experiments demonstrate that class-based reweighting techniques, such as DRW [] and AREA [], notably improve model accuracy regardless of the degree of class imbalance when combined with DAW. Particularly, integrating DAW with DRW and/or AREA yields substantial enhancements in accuracy, underscoring the efficacy of the proposed DAW component.

Table 3.

Comparison results on CIFAR10/100-LT datasets. Top-1 accuracy (%) are reported, with the highest accuracy on each dataset have been highlighted in bold.

Also, we observe that integrating DAW with MSR in our proposed PHASE method yields additional performance enhancements. In comparison to the leading reweighting method AREA, PHASE demonstrates accuracy improvements of {0.94%, 0.49%, 0.96%, 0.31%, 0.33%} on the CIFAR10-LT dataset and {0.99%, 0.24%, 1.02%, 0.74%, 0.46%} on the CIFAR100-LT dataset.

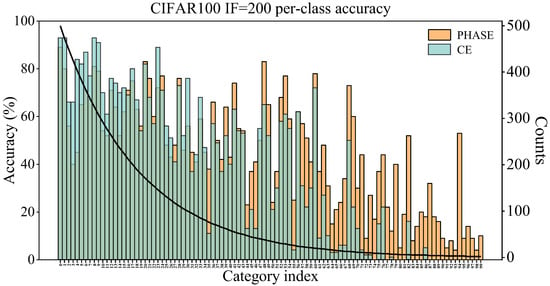

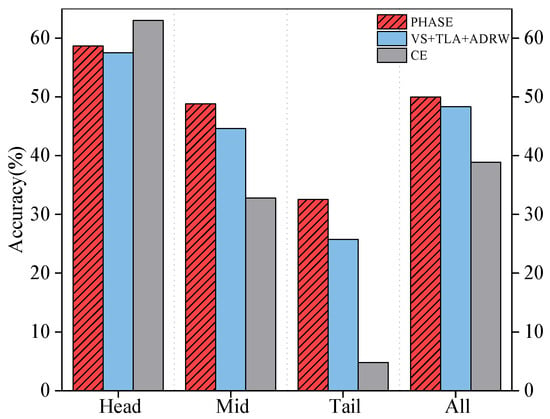

The consistent improvements observed in both datasets with all imbalance levels clearly verify that PHASE is superior to existing reweighting strategies. Besides enhancing overall accuracy, the detailed class-wise performance depicted in Figure 4 demonstrates that PHASE significantly improves the recognition accuracy of tail classes, which are often underrepresented in long-tailed distributions. It verifies the effectiveness of PHASE in addressing class imbalance and facilitating balanced feature learning, indicating that it is particularly suitable for long-tailed visual recognition tasks.

Figure 4.

Classification accuracy and sample count of each class on CIFAR100-LT dataset (IF = 200).

Next, an extensive assessment of PHASE was conducted to compare its performance with current state-of-the-art baseline methods on the ImageNet-LT dataset. The results in Table 4 demonstrate that PHASE achieves a Top-1 accuracy of 49.96% on the ImageNet-LT dataset, outperforming all existing reweighting techniques. To comprehensively evaluate the impact of PHASE on long-tailed distributions, we implemented a categorization approach based on the number of training samples as suggested in []. Specifically, classes in the ImageNet-LT dataset were categorized into three groups: head classes (more than 100 samples per class), medium classes (20 to 100 samples per class), and tail classes (fewer than 20 samples per class). Subsequently, the average accuracy was calculated for each group to assess whether the PHASE model can specifically enhance the performance of tail classes.

Table 4.

Comparison results of various methods on ImageNet-LT dataset, in where the highest accuracy has been highlighted in bold.

The results presented in Figure 5 demonstrate that PHASE consistently outperforms the double-stage method VS + TLA + ADRW [] by 1.14%, 4.22%, and 6.78% in terms of Top-1 accuracy for head, medium, and tail classes, respectively. Additionally, PHASE shows significant superiority over the CE baseline by 16.10% and 27.74% in terms of Top-1 accuracy for medium and tail classes, with a minor decrease of 4.36% for head classes. These results suggest that PHASE effectively enhances the performance of tail and medium classes without compromising the performance of head classes, indicating its efficacy and superiority in managing long-tailed distribution data.

Figure 5.

Comprehensive results on ImageNet-LT dataset.

4.3. Ablation Study

To rigorously assess the effectiveness of the proposed PHASE method, we conducted a series of thorough ablation experiments using the CIFAR100-LT dataset with an imbalance factor of 200. These experiments were carefully designed to systematically evaluate the individual contributions of each component within the PHASE framework. By analyzing each component both independently and in combination, the ablation study aims to deepen our understanding of the specific functional roles and interactions between DAW and MSR in addressing the class imbalance issue. This method enables us to not only determine the impact of each module on performance enhancement but also to explore how their integration results in synergistic benefits that surpass the capabilities of each component in isolation. The outcomes of this analysis further confirm the robustness, modularity, and efficacy of the PHASE framework, indicating its relevance to long-tailed visual recognition tasks characterized by highly skewed class distributions.

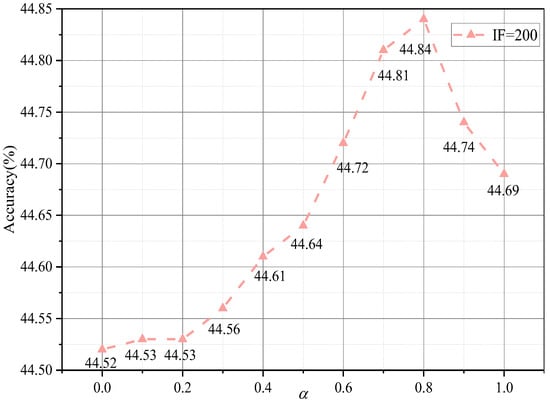

In Equation (13), we introduced a hyper-parameter, denoted as , to balance the tradeoff between two factors, and . To assess the impact of on model performance, we present the accuracy–weight variation curve in Figure 6. In this curve, varies from 0 to 1 with an increment of 0.1. The results depicted in Figure 6 indicate that the performance initially improves with an increase in . However, once it reaches an optimal value, the performance starts to decline. This observation aligns with our expectation that both weights are crucial for improving the performance of the model. Furthermore, we find that an optimal setting can significantly improve the performance of the model. Notably, when is set to 0.8, it enhances the performance by 0.15% and 0.32% compared to using and independently, respectively.

Figure 6.

Impact of the parameter α at classification accuracy on CIFAR-100-LT (IF = 200) dataset.

As previously outlined, the PHASE framework comprises two main modules: DAW and the MSR. To assess the efficacy of these two components individually and in combination, we conducted an ablation study using the CIFAR100-LT dataset with an imbalance factor of 200. The results, detailed in Table 5, indicate that both DAW and MSR, when employed separately, significantly enhance classification performance compared to the baseline approach. Furthermore, the integration of these two components within the PHASE framework leads to additional performance improvements, highlighting a synergistic relationship between the two strategies. These results not only confirm the effectiveness of each component in mitigating class imbalance challenges, but also verify the overall robustness of the unified PHASE framework in addressing long-tailed visual recognition tasks.

Table 5.

Ablation results of two main components of PHASE, where the best classification accuracy (%) on CIFAR100-LT (IF = 200) dataset has been highlighted in bold. Specifically, √ and × denote the corresponding component is involved or not, respectively.

4.4. Comparison with SOTA Methods

In our initial experiments, we utilized a ResNet-32 architecture with 16 filters in the initial convolutional layer. However, recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods [,] suggest that employing deeper ResNet-32 architectures with 64 filters in the initial layer enhances classification performance. To ensure a fair comparison with these SOTA methods and fully maximize the potential of our proposed model, we also implemented a ResNet-32 architecture with the same number of channels. Furthermore, we integrated the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) technique [] to enhance the optimization capability for tail classes. This technique assists in steering clear of saddle points and reaching flatter minima, thereby improving the overall performance [].

In addition to the optimization techniques mentioned above, we also implemented various advanced image augmentation techniques [], such as random cropping, horizontal flipping, and color jittering. These techniques aim to enhance input diversity, thereby enhancing the generalization ability of learning models in practical settings. We still conducted experiments on CIFAR100-LT dataset, with IF in range of {10, 50, 100}, respectively. The results presented in Table 6 demonstrate that the enhanced PHASE framework can achieve classification accuracy that is equal to or better than those state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods [,,,,], thus confirming its efficacy and superiority. Specifically, PHASE performs best on CIFAR100-LT with IF = 100, and takes the second places on two other IF settings (only performs a little worse than SURE []). The results show that PHASE is robust enough as it performs excellent even if the class imbalance level is excessively high.

Table 6.

Compared results with current SOTA methods on CIFAR100-LT dataset with IF in range of {10, 50, 100}, in where the highest accuracy on each IF setting has been highlighted in bold.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced PHASE, a novel progressive hierarchical adaptation framework for sample-efficient rebalancing in long-tailed classification. PHASE is designed around a two-stage tuning paradigm that systematically addresses both sample-level difficulty and class-level imbalance.

The effectiveness of PHASE is strongly demonstrated by our extensive experimental results. On CIFAR-100-LT with a high imbalance factor (IF) of 200, PHASE achieved a top-1 accuracy of 44.84%, significantly outperforming the state-of-the-art AREA method (43.85%). More notably, on the large-scale ImageNet-LT dataset, PHASE reached a top-1 accuracy of 49.96%, surpassing the previous best reweighting techniques and demonstrating a substantial improvement over the CE baseline (38.88%). A detailed analysis revealed that these gains were particularly pronounced for medium and tail classes, confirming PHASE’s capability to alleviate model bias without compromising head class performance. The consistent superiority of PHASE across multiple benchmarks and imbalance ratios underscores the validity of its core design principle: decoupling difficulty-aware representation learning from multi-scale classifier rebalancing.

These findings highlight that adaptive, hierarchical tuning is a highly promising direction for long-tailed visual recognition. The PHASE framework provides a robust and effective baseline for future research in this area.

In future work, we plan to explore more efficient approximations for the MSR computation to enhance scalability. Furthermore, we will prioritize investigating the application of the PHASE paradigm to more complex and noisy real-world scenarios, as well as other challenging vision tasks suffering from data imbalance, such as object detection and semantic segmentation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, C.S.; formal analysis, J.L. and J.D.; investigation, J.D.; resources, H.Y.; data curation, J.L. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and H.Y.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, H.Y.; project administration, H.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No.62176107.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the following sources: CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 are available at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 21 September 2025) and ImageNet is available at https://image-net.org/ (accessed on 21 September 2025). The codes of the proposed PHASE algorithm can be freely downloaded from https://github.com/Darren20000/PHASE (accessed on 10 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASL | Asymmetric Loss |

| PHASE | Progressive Hierarchical Adaptation for Sample-Efficient rebalancing |

| DAW | Difficulty-Aware Weighting |

| MSR | Multi-Scale Reweighting |

| LDAM | Label-Distribution-Aware Margin |

| VS | Vector-Scaling |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| SAM | Sharpness-Aware Minimization |

| SOTA | State-of-the-art |

References

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Boykov, Y.; Porikli, F.; Plaza, A.J.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Terzopoulos, D. Image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3523–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Li, F.F. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Lapedriza, A.; Khosla, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Places: A 10 million image database for scene recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 1452–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, M.S.; Kühlewein, L.; Aliyeva, G.; Inhoffen, W.; Ziemssen, F.; Berens, P. Expert-validated estimation of diagnostic uncertainty for deep neural networks in diabetic retinopathy detection. Med. Image Anal. 2020, 64, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Chun, D.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.-J. Gaussian YOLOv3: An accurate and fast object detector using localization uncertainty for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Cui, Q.; Wei, X.-S.; Chen, Z.-M. BBN: Bilateral-branch network with cumulative learning for long-tailed visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 9719–9728. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Yu, C.; Ma, X.; Zhao, H.; Yi, S. Balanced meta-softmax for long-tailed visual recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 4175–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jia, M.; Lin, T.Y.; Song, Y.; Belongie, S. Class-balanced loss based on effective number of samples. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9268–9277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.K.; Jayasumana, S.; Rawat, A.S.; Jain, H.; Veit, A.; Kumar, S. Long-tail learning via logit adjustment. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Wei, C.; Gaidon, A.; Arechiga, N.; Ma, T. Learning imbalanced datasets with label-distribution-aware margin loss. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 1567–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Kini, G.R.; Paraskevas, O.; Oymak, S.; Thrampoulidis, C. Label-imbalanced and group-sensitive classification under overparameterization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 18970–18983. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Xie, S.; Rohrbach, M.; Yan, Z.; Gordo, A.; Feng, J.; Kalantidis, Y. Decoupling representation and classifier for long-tailed recognition. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Cui, J.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. Improving calibration for long-tailed recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16489–16498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Kang, B.; Li, J.; Liew, J.; Tang, S.; Hoi, S.; Feng, J. The devil is in classification: A simple framework for long-tail instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 728–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, D.; Yang, C.; Li, B.; Hu, Q.; Wang, W. Area: Adaptive reweighting via effective area for long-tailed classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 19277–19287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, D.; Shen, X. SURE: Survey recipes for building reliable and robust deep networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 17500–17510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridnik, T.; Ben-Baruch, E.; Zamir, N.; Noy, A.; Friedman, I.; Protter, M.; Zelnik-Manor, L. Asymmetric loss for multi-label classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 8024–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foret, P.; Kleiner, A.; Mobahi, H.; Neyshabur, B. Sharpness-aware minimization for efficiently improving generalization. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Han, Z.; Wen, Q. Deep quantization network for efficient image retrieval. In Proceedings of the 13th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; pp. 3457–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P. Accurate, large minibatch SGD: Training ImageNet in 1 hour. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zeng, W.; Yang, B.; Urtasun, R. Learning to reweight examples for robust deep learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4334–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lim, J.; Jeon, Y.; Choi, J.Y. Influence-balanced loss for imbalanced visual classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Miao, Z.; Zhan, X.; Wang, J.; Gong, B.; Yu, S.X. Large-scale long-tailed recognition in an open world. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2537–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Z.; He, Y.; Cao, X.; Huang, Q. A unified generalization analysis of re-weighting and logit-adjustment for imbalanced learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 48417–48430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Yang, P.; Jia, Q.; Nan, F.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y. Global and local mixture consistency cumulative learning for long-tailed visual recognitions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 15814–15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwani, H.; Aithal, S.K.; Mishra, M. Escaping saddle points for effective generalization on class-imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; pp. 22791–22805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Mane, D.; Vasudevan, V.; Le, Q.V. Autoaugment: Learning augmentation policies from data. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.K.; Seo, S.W. Long-tailed recognition by mutual information maximization between latent features and ground-truth labels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 32770–32782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwani, H.; Mondal, P.; Mishra, M.; Asokan, A.R.; Babu, R.V. DeiT-LT: Distillation strikes back for vision transformer training on long-tailed datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 23396–23406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jiang, C.; Hu, W.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J. MDCS: More diverse experts with consistency self-distillation for long-tailed recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 11597–11608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).