Symmetry-Aware Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Under Real-World Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

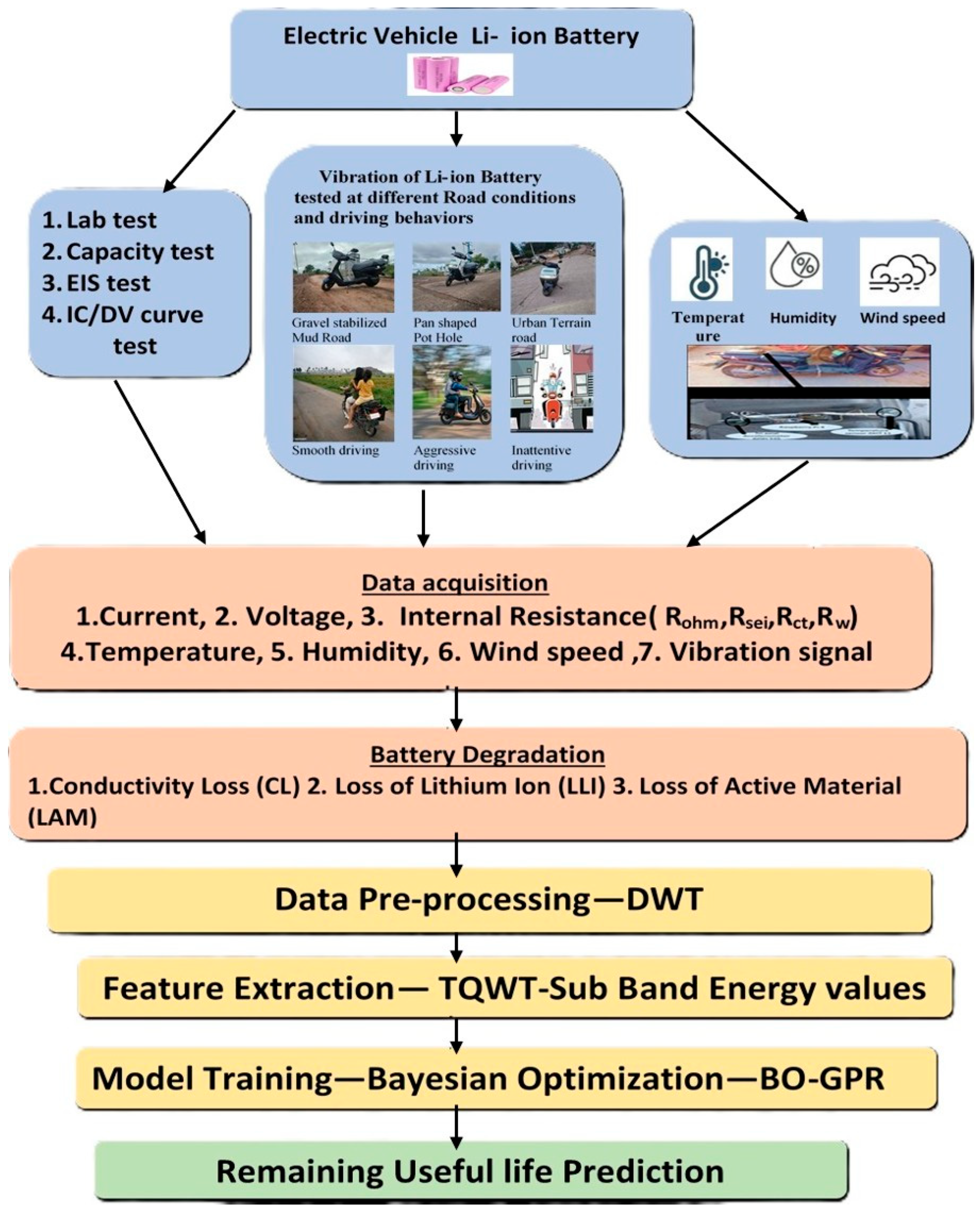

- Integration of multi-domain factors: Unlike conventional approaches, the proposed framework incorporates battery internal resistance, degradation characteristics, micro-climatic conditions (temperature, humidity, wind speed), road surface types, and driving behaviors.

- Advanced vibration signal processing: Vehicle-induced vibration signals are denoised using DWT, and TQWT is employed for band-specific feature extraction.

- Bayesian optimization of regression model: The BO-GPR algorithm is developed to combine micro-climatic and vibration features with degradation data, achieving robust and accurate RUL prediction.

- Experimental validation: The proposed method achieves an accuracy of 98.1%, outperforming conventional regression and machine learning approaches. Experimental analysis further confirms that Z-axis vibrations, aggressive driving, and urban terrain roads significantly accelerate degradation under micro-climatic variability.

1.1. Problem Statement

- RQ1: How do driving behavior and micro-climatic conditions influence battery degradation during EV operation?

- RQ2: How can RUL be analyzed and predicted using degradation parameters and micro-climatic data?

- RQ3: Which degradation parameters have the most significant influence on RUL prediction?

1.2. Contributions

- Detection of the impact of vibration on the battery pack due to different road conditions, such as a pan-shaped pothole, gravel-stabilized mud road, and urban terrain road, through an accelerometer fixed on the battery module and motor driver circuit. Simultaneously, battery degradation modes are analyzed during different driving behaviors such as inattentive driving, aggressive driving, and smooth driving.

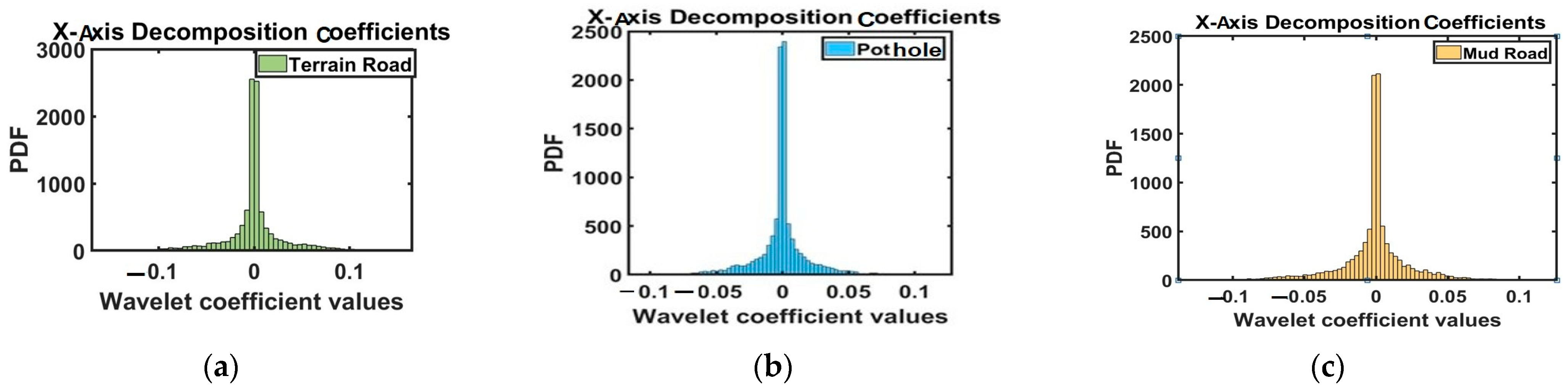

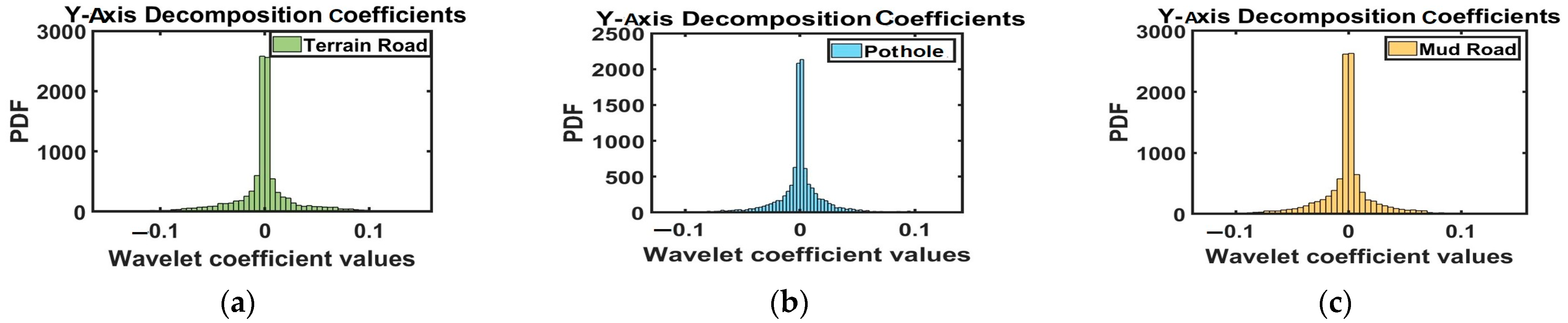

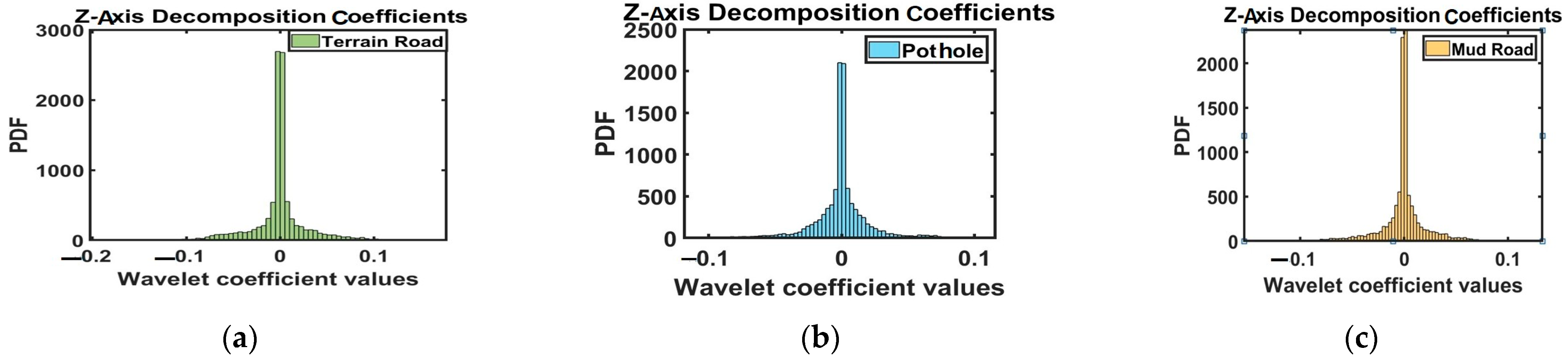

- Analysis of the low-frequency vibration impact on the battery through DWTs applied to the low-frequency vibration signals and performing residual coefficient analysis.

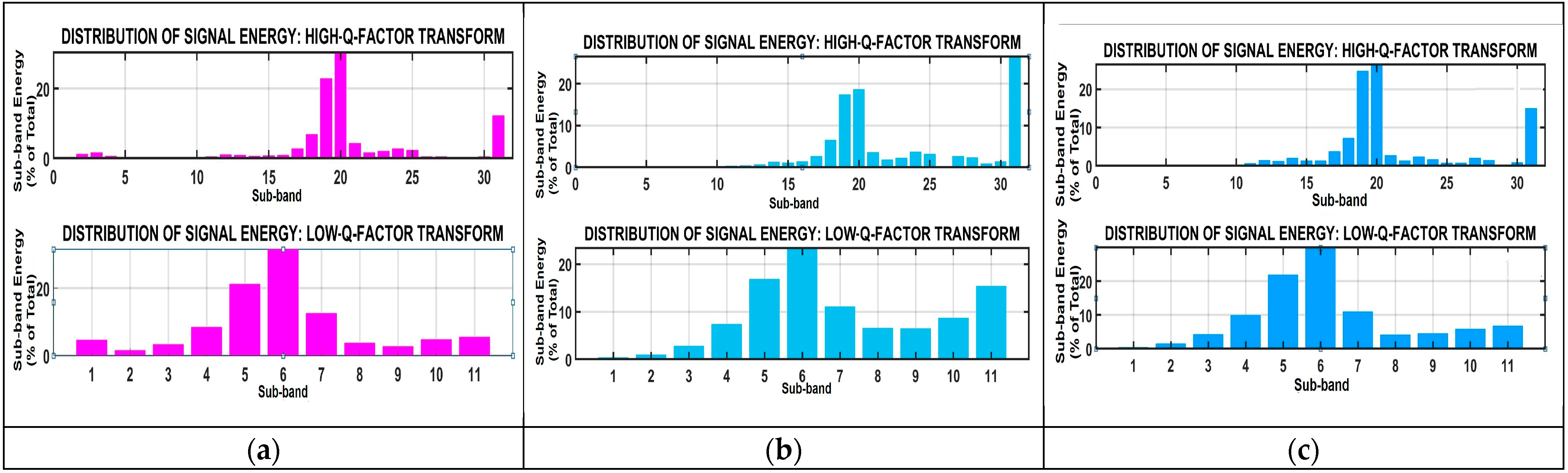

- Energy band analysis of low- and high-vibration signals and analysis of their impact on the battery through a proposed algorithm, TQWT, under different road conditions and with different driving behaviors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Lab Based Measurements

2.1.1. Capacity Test

2.1.2. EIS Test

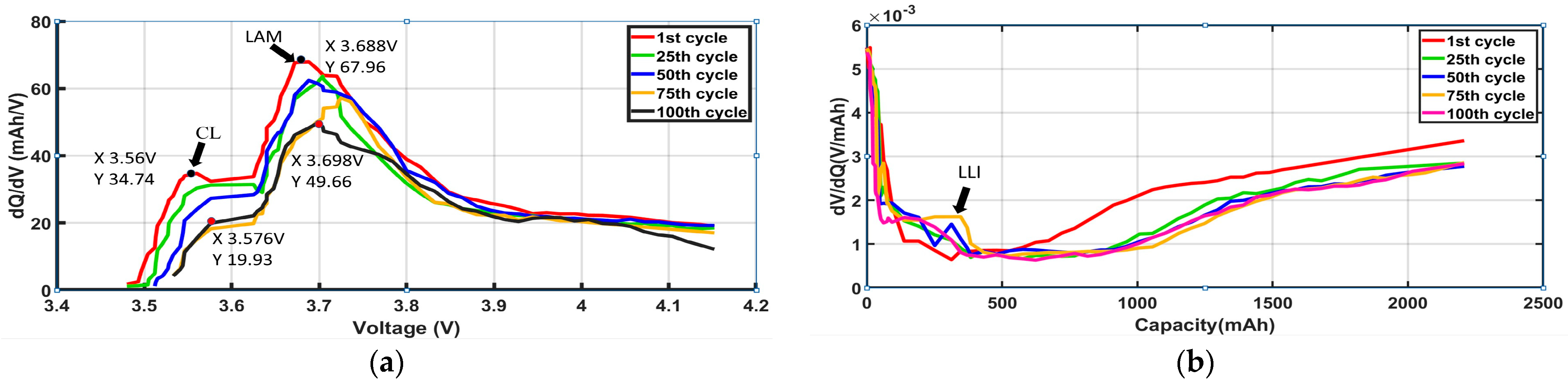

2.1.3. IC/DV Curve Test Analysis

2.2. On-Road EV Running Condition-Based Vibration Signal Acquisition

2.3. Vibration Signal Processing Using DWT

2.4. Energy and Transient Feature Extraction of Vibrational Signals Using TQWT

2.5. Bayesian-Optimized Regression Framework for RUL Prediction

2.5.1. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR)

2.5.2. Multiple Linear Regression

3. Results and Discussion

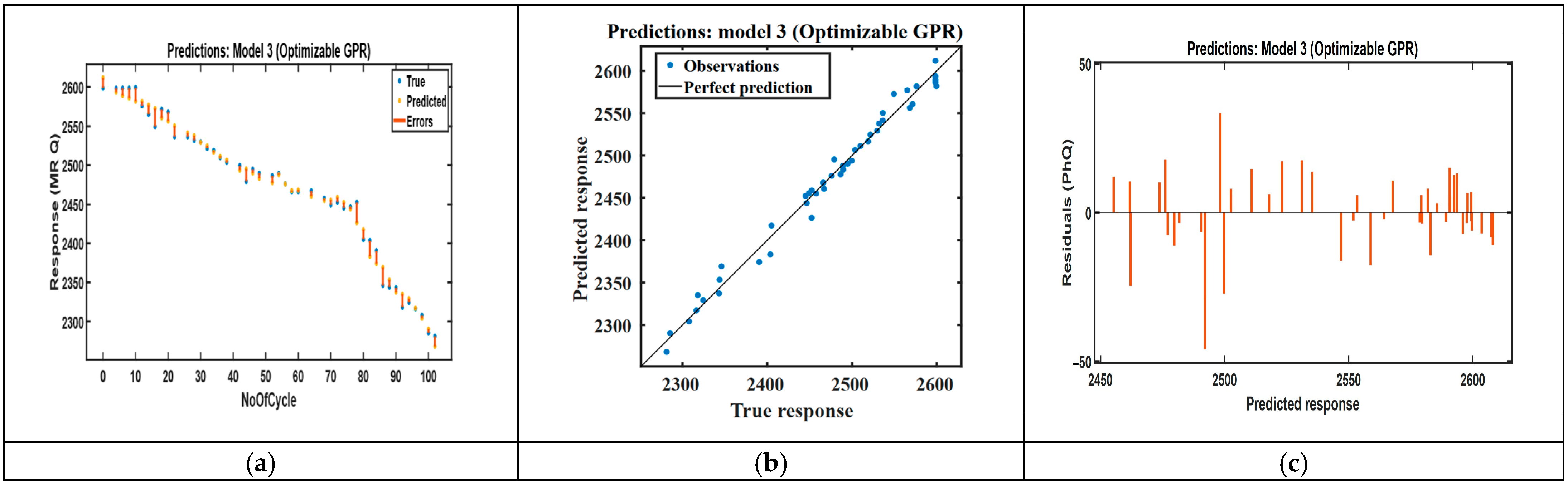

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

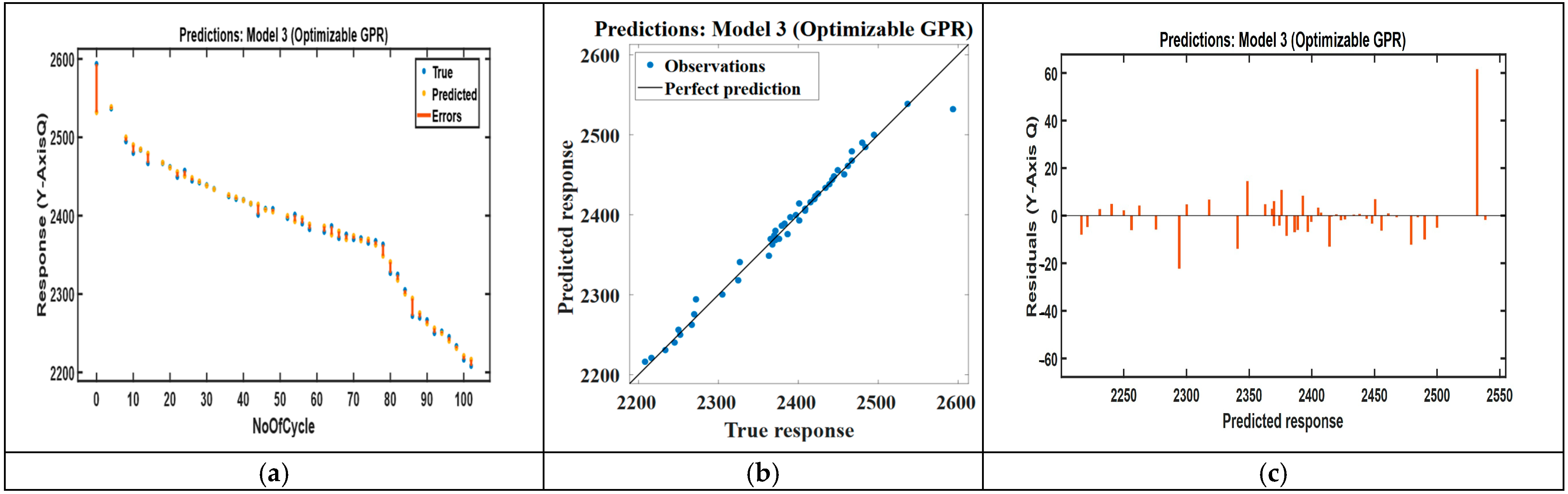

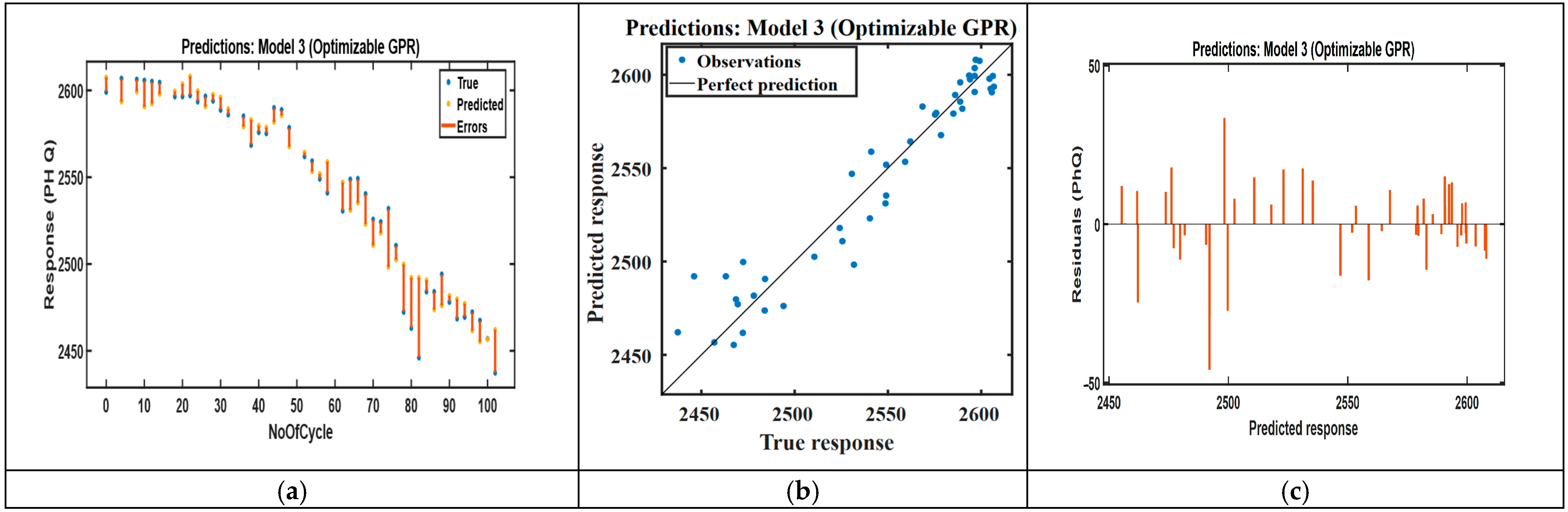

3.1.1. RUL Capacity Prediction Fade for Vibration

3.1.2. RUL Capacity Prediction with Different Road Conditions

3.1.3. RUL Capacity Prediction Fade for Driving Behavior

3.2. Effect of Micro-Climatic Conditions

3.3. Influence of Road Surface Condition and Driving Behavior

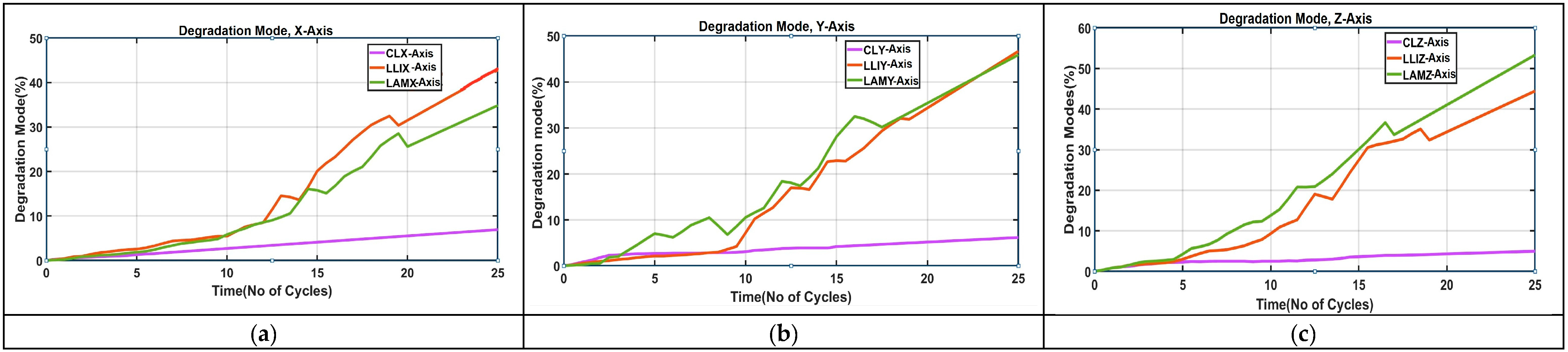

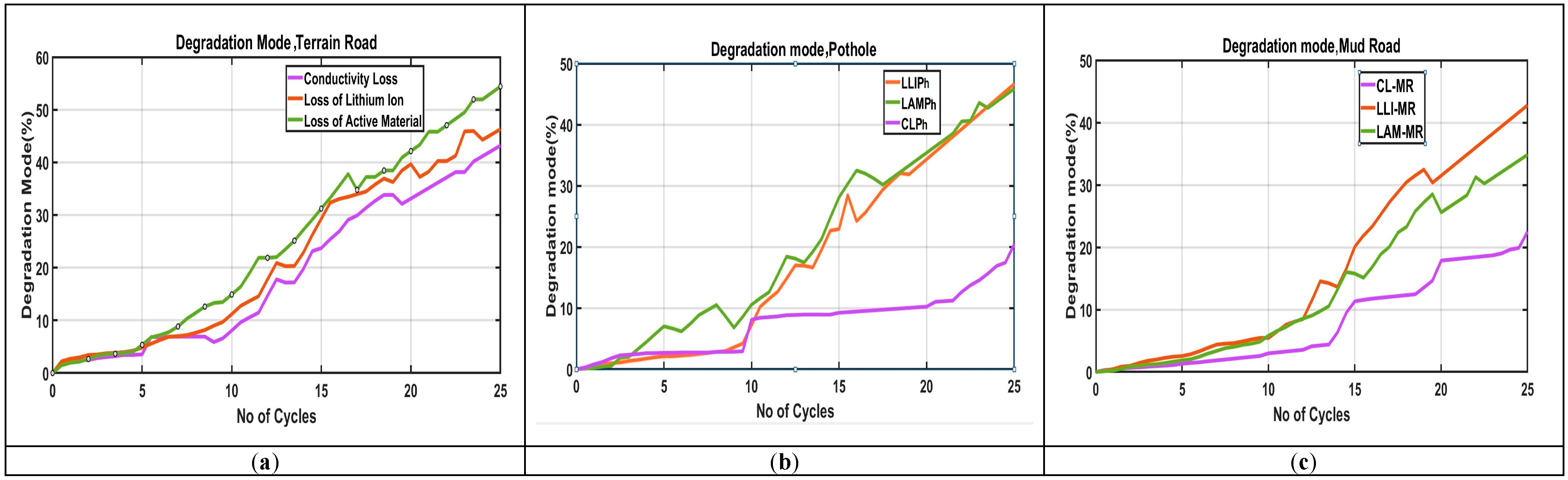

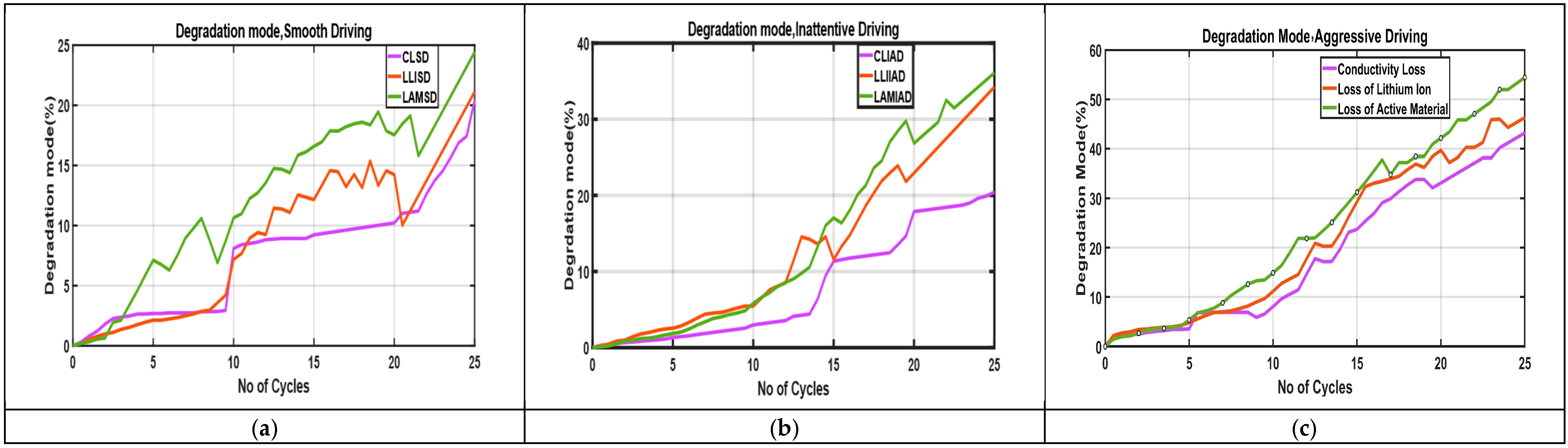

3.3.1. Effect of Road Condition, Vibration, and Driving Behavior on Battery Degradation

3.3.2. Degradation Modes for Vibration Along X-, Y-, and Z-Axes

3.3.3. Degradation Modes for Different Road Conditions

3.3.4. Degradation Modes for Different Driving Behavior

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Degradation Parameter

3.5. Validation Against Experimental Data

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOGPR | Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression |

| CL | Conductivity Loss |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| EOL | End of Life |

| LAM | Loss of Active Material |

| LLI | Loss of Lithium Ion |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| SOH | State of Health |

| SEI | Solid Electrolyte Interphase |

| TQWT | Tunable Q-factor wavelet Transform |

References

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, H.; Xing, J.; Yang, Q.; Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J. LightGBM-based framework for lithium-ion battery remaining useful life prediction under driving conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 11353–11362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.R.M.; Tasnim, S.; Mahmud, S.; Van Heyst, B. Thermal field investigation of lithium-ion battery with porous medium under vibration. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Jin, Y.; Mu, Y.; Meng, J.; Zhang, T.; Teodorescu, R. Improved LightGBM-based framework for electric vehicle lithium-ion battery remaining useful life prediction using multi health indicators. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.; Siddique, A.R.M.; Venkateshwar, K.; Mohaghegh, M.R.; Tasnim, S.H.; Mahmud, S. Experimental investigation on thermal field measurement of lithium-ion batteries under vibration. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Mohammed, H.I.; Chen, S.; Alkali, B.; Luo, M.; Yang, J. Mechanical vibration’s effect on thermal management module of Li-Ion battery module based on phase change material (PCM) in a high-temperature environment. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, X.; An, W.; Shi, B. Impacts of vibration and cycling on electrochemical characteristics of batteries. J. Power Source 2024, 601, 234274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Wu, W.; Huang, J. Influence of mechanical vibration on composite phase change material based thermal management system for lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F. Study on the capacity degradation mechanism and capacity predication of lithium-ion battery under different vibration conditions in six degrees-of-freedom. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2023, 20, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Tang, T.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, K.; Tian, J.; Hu, D.; Yang, D.; Sun, B.; Feng, Q.; Qian, C. A data and physical model joint driven method for lithium-ion battery remaining useful life prediction under complex dynamic conditions. J. Energy Storage 2024, 79, 110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Transfer learning-based hybrid remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries under different stresses. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3501810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lu, C.; Li, B.; Liu, C.; Cheng, D. Capacity evaluation and degradation analysis of lithium-ion battery packs for on-road electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Thomas, A. Effect of dynamic loads and vibrations on lithium-ion batteries. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control. 2021, 40, 1927–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Yin, S.; Kaynak, O. Remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion battery with adaptive noise estimation and capacity regeneration detection. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 28, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyucu, S.; Dümen, S.; Duru, İ.; Aksöz, A.; Biçer, E. Discharge Capacity Estimation for Li-Ion Batteries: A Comparative Study. Symmetry 2024, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. A data-driven method with mode decomposition mechanism for remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 13684–13695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, L.; Badr, P.R.; Hoang, P.H.; Ozkan, G.; Papari, B.; Edrington, C.S. Battery degradation in electric and hybrid electric vehicles: A survey study. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 42431–42462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Hong, W.; Zhou, X. Transformer network for remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19621–19628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Mao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J. Hybrid data-driven approach for predicting the remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Chow, M.Y.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Luo, H.; Yin, S. A data-model interactive remaining useful life prediction approach of lithium-ion batteries based on PF-BiGRU-TSAM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Intelligent Learning Method for Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Partial Charging Curves. Energies 2024, 17, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Li, G.H. A Bayesian deep learning framework for RUL prediction incorporating uncertainty quantification and calibration. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 7274–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Wei, Y.; Qi, H. Joint Prediction of Li-Ion Battery Cycle Life and Knee Point Based on Early Charging Performance. Symmetry 2025, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zeng, S.; Guo, J.; Skaf, Z. State of Health Estimation of Li-ion Batteries with Regeneration Phenomena: A Similar Rest Time-Based Prognostic Framework. Symmetry 2017, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wreikat, Y.; Serrano, C.; Sodré, J.R. Driving behaviour and trip condition effects on the energy consumption of an electric vehicle under real-world driving. Appl. Energy 2021, 297, 117096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Liu, Z. Transfer Learning-Based Remaining Useful Life Prediction Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Considering Individual Differences. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Fan, X.; Fan, Y.; Wang, R.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, D. A Transferable Prediction Approach for the Remaining Useful Life of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Small Samples. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, W.; Yue, C.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, W. Remaining Useful Life Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Small Sample Models. Energies 2024, 17, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxandi-Santolaya, M.; Mora-Pous, A.; Canals Casals, L.; Corchero, C.; Eichman, J. Quantifying the impact of battery degradation in electric vehicle driving through key performance indicators. Batteries 2024, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, B.; Liu, W. Symmetry-Guided Electric Vehicles Energy Consumption Optimization Based on Driver Behavior and Environmental Factors: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. Symmetry 2025, 17, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhsissin, S.; Sael, N.; Benabbou, F. Driver behavior classification: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 14128–14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raslan, E.; Alrahmawy, M.F.; Mohammed, Y.A.; Tolba, A.S. Evaluation of data representation techniques for vibration based road surface condition classification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ríos, E.A.; Bustamante-Bello, M.R.; Arce-Sáenz, L.A. A review of road surface anomaly detection and classification systems based on vibration-based techniques. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Xing, J.; Liu, X. A Rolling Bearing Vibration Signal Noise Reduction Processing Algorithm Using the Fusion HPO-VMD and Improved Wavelet Threshold. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Remaining useful life prediction of high-capacity lithium-ion batteries based on incremental capacity analysis and Gaussian kernel function optimization. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Shen, S.; Ye, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhen, A. An interpretable online prediction method for remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Cai, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, L. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries using CEEMDAN and WOA-SVR Model. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 984991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lyu, Z.; Li, X. An Optimized Random Forest Regression Model for Li-Ion Battery Prognostics and Health Management. Batteries 2023, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cheng, X.; Huang, H.; Fang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Xing, J. Remaining useful life prediction of Lithium-ion batteries based on PSORF algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 937035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Gaussian Process Regression | Multiple Linear Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | Model Equation | |

| X-axis-RUL capacity prediction | 1.61 | 0.99 | 11.1 | 98.39 | 2.25 | 0.95 | 16.9 | 96.46 | RUL = 2350.25 − 12.66n + 2379.11R_ohm + 351.22R_ct − 12236.41R_sei − 580.93R_w − 0.21temp + 0.64humidity − 0.21wind speed + 154.8CL + 5.12LLI − 6.73LAM |

| Y-axis-RUL capacity prediction | 1.14 | 0.98 | 6.7 | 98.48 | 2.43 | 0.92 | 20.69 | 96.84 | RUL = 2554.66 + 0.45n − 517.55R_ohm − 2665.49R_ct − 3162.57R_sei − 1294.06R_w + 0.68temp + 2.40humidity − 0.70wind speed − 50.71CL − 3.34LLI + 4.47LAM |

| Z-axis-RUL capacity prediction | 1.54 | 0.98 | 8.3 | 98.32 | 2.36 | 0.95 | 17.87 | 96.35 | RUL = 2632 − 4.72n − 1943.4R_ohm − 1160R_ct − 1824.8R_sei − 2736.26R_w − 5.2temp + 2.13humidity + 0.50wind speed − 16.51CL − 7.14LLI + 7.94LAM |

| Model | Gaussian Process Regression | Multiple Linear Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | Model Equation | |

| Urban terrain road-RUL capacity prediction | 1.24 | 0.99 | 9.46 | 97.53 | 2.56 | 0.96 | 20.45 | 95.87 | RUL = 2600 − 2.78n − 1624.6R_ohm − 1186.5R_ct − 1788.9R_sei − 2515.7R_w − 8.27temp + 0.94humidity − 1.19wind speed − 9.8CL − 8.2LLI + 4.2lo |

| Pan-shaped pothole-RUL capacity prediction | 1.44 | 0.97 | 11.32 | 98.25 | 1.51 | 0.92 | 12.12 | 97.96 | RUL = 2818.62 − 0.073n + 403.2R_ohm − 3762.08R_ct − 5613.37R_sei + 773.16R_w − 4.17temp − 1.05humidity + 0.12wind speed + 1.53CL − 0.08LLI − 0.36LAM |

| Gravel-stabilized mud road-RUL-capacity prediction | 1.07 | 0.98 | 8.51 | 98.41 | 2.73 | 0.91 | 20.96 | 97.48 | RUL = 2818.62 − 0.073n + 403.2R_ohm − 3762.08R_ct − 5613.37R_sei + 773.16R_w − 4.17temp − 1.05humidity + 0.12wind speed + 1.53CL − 0.08LLI − 0.36LAM |

| Model | Gaussian Process Regression | Multiple Linear Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | RMSE | R2 | MAE mAH | Prediction Accuracy % | Model Equation | |

| AD-RUL capacity prediction | 1.44 | 0.98 | 8.74 | 97.9 | 2.34 | 0.96 | 18.69 | 96.48 | RUL = 2642.3 − 3.95n + 143.12R_ohm − 2652.49R_ct − 7834.75R_sei − 1159.11R_w + 1.86temp − 1.68humidity − 7.28wind speed − 0.15CL − 1.62LLI − 2.45LAM |

| IAD-RUL capacity prediction | 1.15 | 0.98 | 15.70 | 97.38 | 1.91 | 0.95 | 8.21 | 96.55 | RUL = 2500.5 − 1.5n + 3000R_ohm − 4000R_ct − 9000R_sei − 2000R_w − 7temp + 5humidity − 13wind speed − 2CL + 2LLI − 0.3LAM |

| SD-axis-capacity prediction | 1.17 | 0.97 | 8.89 | 98.29 | 1.70 | 0.89 | 12.96 | 96.11 | RUL = 2818.62 − 0.073n + 403.2R_ohm − 3762.08R_ct − 5613.37R_sei + 773.16R_w − 4.17temp − 1.05humidity + 0.12wind speed + 1.53CL − 0.08LLI − 0.36LAM |

| ON-ROAD Condition | ON-ROAD Values | Lab Test | Predicted RUL Ah | Measured RUL Ah | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TQWT Sub-Band Energy Values (in % of Total) | Temperature °C | Humidity % | Wind Speed Km/h | EIS Test | Degradation Test | |||||||||

| Rohm (mΩ) | Rsei (mΩ) | Rct (mΩ) | Rw (mΩ) | CL % | LLI % | LAM % | ||||||||

| Vibration | X-axis | 23 | 36 | 55 | 16 | 173 | 6 | 37 | 28 | 6.9 | 42.7 | 34.8 | 2364.49 | 2403.18 |

| Y-axis | 26 | 38 | 58 | 19 | 180 | 21 | 36 | 25 | 6.1 | 46.6 | 45.8 | 2302.48 | 2338.02 | |

| Z-axis | 38 | 37 | 49 | 19 | 178 | 18 | 35 | 27 | 4.9 | 44.4 | 53.3 | 1776.49 | 1806.85 | |

| Road Condition | Urban terrain road | 28 | 38 | 51 | 19 | 31 | 24 | 81 | 28 | 42 | 44.4 | 53.4 | 1821.12 | 1867.24 |

| Gravel-stabilized mud road | 24 | 37 | 55 | 18 | 29 | 26 | 67 | 25 | 22.5 | 42.7 | 34.8 | 2435.08 | 2474.42 | |

| Pan-shaped pothole | 25 | 36 | 52 | 14 | 28 | 22 | 52 | 27 | 20.4 | 46.6 | 45.9 | 2232.89 | 2272.66 | |

| Driving Behavior | Aggressive driving | 39 | 36 | 54 | 12 | 290 | 32 | 50 | 26 | 43.2 | 46.3 | 54.4 | 2181.88 | 2560.33 |

| Inattentive driving | 26 | 37 | 52 | 15 | 325 | 26 | 77 | 24 | 20.4 | 21.1 | 24.4 | 2291.23 | 2228.68 | |

| Smooth driving | 22 | 38 | 48 | 15 | 178 | 9 | 37 | 21 | 20.4 | 34.2 | 36.1 | 2516.55 | 2352.88 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karkuzhali, V.; Jothi Swaroopan, N.; Shanker, N.R.; Senthilraj, S. Symmetry-Aware Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Under Real-World Conditions. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122039

Karkuzhali V, Jothi Swaroopan N, Shanker NR, Senthilraj S. Symmetry-Aware Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Under Real-World Conditions. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122039

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarkuzhali, Vikraman, Nesamony Jothi Swaroopan, Nagalingam Rajendiran Shanker, and Sarangapani Senthilraj. 2025. "Symmetry-Aware Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Under Real-World Conditions" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122039

APA StyleKarkuzhali, V., Jothi Swaroopan, N., Shanker, N. R., & Senthilraj, S. (2025). Symmetry-Aware Bayesian-Optimized Gaussian Process Regression for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Under Real-World Conditions. Symmetry, 17(12), 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122039