Abstract

Vector geographic data require strict preservation of coordinate precision and topological integrity. However, their open transmission poses simultaneous challenges for copyright protection and data security. To address these issues, this study proposes a reversible watermarking framework that integrates difference expansion (DE) for lossless coordinate recovery, the Arnold transform for watermark encryption, and a metadata-assisted dual restoration mechanism to ensure geometric and topological consistency after embedding. Experimental evaluations on multiple vector datasets—including administrative boundaries, hydrographic networks, and road layers—demonstrate that the proposed method achieves near-zero distortion (RMSE ≈ 10−16), complete reversibility, and strong robustness against geometric and noise attacks, outperforming conventional DFT- and QIM-based schemes in terms of imperceptibility and restoration accuracy. The approach provides an efficient and verifiable solution for secure sharing and copyright protection of vector geographic data, contributing to reliable data provenance and trustworthy spatial information management.

1. Introduction

As a core carrier for representing spatial information, vector geographic data constitute fundamental datasets that describe the geometric shapes, spatial locations, and attribute characteristics of geographic entities. They are widely used in domains such as urban planning, resource management, environmental monitoring, transportation scheduling, and military surveying, and hold a pivotal role in spatial information infrastructure and national digital governance systems [1,2,3,4]. In recent years, with the rapid development of GIS platform service models and spatial data-sharing mechanisms, massive volumes of vector geographic data have been frequently transmitted and exchanged over the Internet. While serious security risks have also emerged [5,6,7]. The high-precision spatial geometry and semantic attribute information carried by vector data are highly sensitive; unauthorized copying, tampering, misappropriation, or malicious dissemination may not only lead to the leakage of nationally sensitive information and the exposure of critical infrastructure but also cause substantial economic losses to data rights holders. Therefore, establishing a trustworthy security protection framework for vector geographic data—particularly technical mechanisms targeting copyright authentication, tamper detection, and content traceability—has become an important research direction at the intersection of geographic information science and information security. In parallel, related studies have explored technical approaches that integrate multi-source spatial data with intelligent modeling [8,9,10,11,12], and the experience gained in data fusion, three-dimensional modeling, and spatial feature reconstruction in these studies can likewise inform the security protection of vector geographic data.

As an important technical means in the field of data ownership protection, digital watermarking embeds specific hidden information into a data carrier to enable copyright declaration, infringement tracing, and identity authentication. According to the manner in which watermark information is associated with the carrier data, digital watermarking techniques can be classified into embedded and non-embedded types. Among them, embedded watermarking, which directly incorporates watermark information into the data itself, offers strong imperceptibility, high robustness, and inseparability from the host data, and has thus become the mainstream approach for protecting the copyright of geographic data. Currently, embedded watermarking methods are primarily divided into frequency-domain and spatial-domain algorithms. Frequency-domain methods perform spectral processing on vector data, such as Fourier transform, wavelet transform, or discrete cosine transform (DCT), to extract geometrically invariant features and establish stable watermark embedding positions, thereby effectively resisting common geometric attacks such as rotation, translation, scaling (RST transformation), and cropping. In earlier studies, Wang et al. [13] proposed a DCT-based watermarking method for vector maps, in which watermark bits are embedded by adjusting the relationships between high-frequency DCT coefficients. A dual-error estimation mechanism was introduced, allowing watermark embedding even under vertex distortion constraints, and providing strong resistance against random noise, scrambling, cropping, and geometric attacks. Shen et al. [14] developed a blind watermarking model based on discrete Fourier transform (DFT), converting the vertex sequence of vector graphics into the frequency domain and embedding the watermark via phase quantization, achieving good imperceptibility while remaining resilient to common attacks. Xu et al. [15,16] constructed a watermarking model from both the magnitude and phase dimensions of the frequency domain, embedding the watermark into the modulus and phase of the DFT coefficients to ensure data recovery accuracy and robustness against multiple attack types. Qu et al. [17] proposed a vector map watermarking algorithm based on a combined DFT and singular value decomposition (SVD) transform, where the Douglas–Peucker algorithm is used to extract feature points and construct geometric invariants, enabling robust resistance to common geometric attacks and local vertex modifications.

Given the limitations of frequency-domain methods in spatial accuracy control, topological consistency, and GIS compatibility, recent studies have gradually shifted toward spatial-domain approaches, seeking a balance between reversibility and embedding robustness. Wang et al. [18,19,20] proposed a reversible fragile watermarking method based on spatial feature grouping and interpolation point marking, which enables high-precision restoration of the original coordinates while providing point-level tamper localization. Follow-up research introduced normalized coordinates and a quantization index modulation (QIM) strategy on this basis, further improving resistance to RST (rotation, scaling, and translation) attacks while maintaining a balance between watermark capacity and imperceptibility. Abubahia et al. [21] incorporated spatial clustering and data mining techniques into the watermark embedding framework, proposing a topology-aware embedding mechanism that offers new perspectives for the application expansion and intelligent processing of vector geographic data. These advances indicate that spatial-domain embedding methods are evolving toward higher precision, stronger security, and improved usability.

The second category comprises spatial-domain methods [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], which embed watermark information by directly adjusting the spatial relationships between points. The bit information is typically embedded through adaptive coordinate perturbation, striking a balance between visual quality and practical usability. Representative techniques include coordinate tolerance embedding [22], coordinate offset embedding [23], difference expansion [24], robust schemes for polylines and polygons [25], virtual coordinates [26], direction–distance quantization [27], frequency-domain-assisted embedding [28], and normalization strategies [29]. In recent years, Qu et al. [31] proposed a feature-point embedding method based on discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and the ratio of conjugate singular values decomposition (CSVD) singular values, effectively enhancing robustness against geometric attacks. Qiu et al. [32] incorporated error control coding to design a spatial watermarking model with error-correction capability, significantly improving watermark extraction accuracy. Hou et al. [33] combined clustering and chaotic mapping to develop a fragile watermarking method capable of accurately localizing tampered entities. Guo et al. [34] constructed stable features via space-filling curves and introduced a prediction difference-driven commutative encryption and watermarking (CEW) algorithm for vector point data, greatly improving watermark capacity and security. Zhang et al. [35] integrated spatial- and frequency-domain features to achieve dual-domain embedding, thereby enhancing both anti-attack capability and blind extraction performance. Wang et al. [36] developed a multiple quantization index modulation (QIM) algorithm to enable interference-free embedding of multiple watermarks, improving both robustness and capacity. Building on this, Wang et al. [37] proposed a logic-domain-mapping-based multi-watermarking algorithm that supports blind detection without the original data while offering excellent resistance to attacks.

Although spatial-domain watermarking methods have achieved significant progress, several limitations remain in the context of protecting high-precision vector geographic data. On one hand, conventional spatial-domain embedding approaches often modify the coordinates of vector geographic data directly, a process that frequently results in irreversible precision loss. This limitation is particularly problematic in strictly regulated application scenarios such as land and resource management, where compliance with stringent accuracy standards is required. On the other hand, existing watermarking algorithms often place insufficient emphasis on the security and anti-attack performance of the watermark itself, lacking proactive protection and optimization mechanisms for the embedded information. As a result, watermark data can be easily compromised or rendered invalid under various geometric transformations or malicious data-tampering attacks. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a novel spatial-domain watermarking approach that can embed watermark information through coordinate micro-adjustments while ensuring that precision loss remains well below the application-defined precision thresholds, and that original coordinates can be fully restored. Moreover, such a method should incorporate proactive security mechanisms to protect the watermark information itself, enabling it to withstand complex and hostile operational environments.

To summarize, despite extensive progress in both frequency- and spatial-domain watermarking, two research gaps remain in the context of vector GIS data. First, many spatial-domain schemes directly modify coordinates and thus cannot guarantee exact coordinate-level reversibility under strict precision requirements. Second, while metadata can assist coordinate recovery, existing approaches have rarely explored systematic metadata-guided restoration and often lack mechanisms to ensure full geometric–topological consistency after embedding. In our framework, metadata serve as a structured auxiliary record to achieve reversible restoration under normal conditions; however, if the metadata are entirely lost or corrupted, coordinate reconstruction becomes infeasible—a limitation that defines the theoretical boundary of reversibility.

These observations motivate the proposed reversible watermarking framework that employs difference expansion for lossless coordinate recovery and metadata-assisted restoration to ensure geometric and topological consistency, while explicitly defining the recoverability boundary under metadata degradation. Building upon these observations, this study introduces a spatial-domain watermarking algorithm based on difference expansion. In contrast to conventional methods that rely solely on sub-pixel coordinate adjustments of point positions, the proposed approach directly applies difference expansion to vector data, substantially increasing the degree of data perturbation while enabling precise restoration of the original data through a key-based mechanism. To embed watermark information, Thiessen polygons are employed as structural carriers, allowing watermark bits to be inserted within feature-based partitions, thereby enhancing both embedding capacity and structural consistency. This design is particularly well suited to scenarios requiring encrypted protection of spatial data: by combining difference expansion with key-dependent restoration and structured metadata, the scheme protects the embedded watermark and enables reliable authentication even when the original dataset is unavailable.

In the proposed framework, the notion of symmetry is embodied in the reversible correspondence between the original and the watermarked coordinate domains. Each coordinate perturbation introduced during watermark embedding can be symmetrically restored through the difference expansion and metadata restoration mechanisms, ensuring perfect geometric–topological consistency after recovery.

Conversely, asymmetry is intentionally incorporated into the security design: the embedding and extraction processes are deliberately non-symmetric, since only authorized users possessing the secret key and metadata can execute the inverse reconstruction.

This deliberate balance between geometric symmetry and cryptographic asymmetry establishes a dual safeguard—enabling high-precision reversibility in benign conditions while maintaining strong robustness and confidentiality under adversarial scenarios.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Arnold Scrambling

A common practice for enhancing the security of watermark information is to perform scrambling-based encryption prior to embedding. Typical watermark scrambling techniques include Arnold scrambling, Fibonacci transformation, and Hilbert curve mapping. Among these, Arnold scrambling has become a classical tool in watermarking and encryption due to its periodicity, computational efficiency, strong scrambling capability, and flexible parameterization. Its advantages are particularly evident in scenarios where both security and computational efficiency are critical, such as in Internet of Things (IoT) devices and mobile applications. In Arnold scrambling, the pixel coordinates (x, y) of the original watermark image are mapped to new coordinates (, ) through a linear transformation, which can be expressed mathematically as:

In this transformation, (x, y) denotes the original pixel coordinates of the watermark, (, ) represents the transformed coordinates, and N is the size of the watermark image (i.e., its side length). Arnold scrambling exhibits a periodic property: when the number of transformations reaches a certain threshold k, the image returns to its original state. This periodicity is closely related to the image size N, with different image sizes yielding different periods T(N). If the image size N is unknown to an attacker, the correct number of inverse transformations becomes difficult to determine, thereby effectively safeguarding the watermark information. Figure 1a shows the watermark image before transformation, and Figure 1b illustrates the image after transformation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of watermark images before and after Arnold scrambling: (a) the original watermark image prior to transformation; (b) the scrambled watermark image after applying the Arnold transform. The Chinese character “印” represents the embedded watermark text.

2.2. Thiessen Polygons and Their Applicability in Watermark Embedding

Thiessen polygons, also known as Voronoi diagrams, are a classical spatial partitioning structure that divides space into a set of non-overlapping regions, where any point within a region is closer to its generating point than to any other. Their rigorous mathematical properties—such as uniqueness, convexity, the empty-circle property, and their dual relationship with Delaunay triangulations—ensure both geometric rationality and topological consistency in spatial partitioning.

In vector geographic data processing, Thiessen polygons exhibit strong spatial adaptivity. Polygon area is inversely correlated with point density, making them effective for identifying high-density regions. Furthermore, point sets constructed based on their neighborhood relationships can preserve the original spatial distribution patterns, thereby improving local stability in data processing.

In this study, Thiessen polygons are employed to construct candidate regions for watermark embedding. Feature points are extracted from polygon boundaries, and difference expansion embedding is then applied. Leveraging their topological stability and empty-circle consistency, the proposed approach enhances watermark robustness while maintaining spatial accuracy. In addition, the extensive use of Thiessen polygons in GIS applications supports their effectiveness in neighborhood extraction, spatial indexing, and local perturbation detection.

2.3. Principle of Difference Expansion Steganography

Difference expansion (DE) is a representative reversible data hiding (RDH) technique that embeds bit information by expanding the difference between paired data values, enabling information insertion without compromising the perfect recovery of the original data. Through three steps—difference calculation, expansion embedding, and coordinate reconstruction—the method allows simultaneous restoration of both the watermark and the original data, with its mathematical reversibility widely validated.

This approach offers high information-hiding efficiency, with embedding capacity primarily determined by the dynamic range of the data, making it well-suited for applications requiring high-fidelity reconstruction. In spatial data, DE can be adapted to the spatial distribution characteristics of geographic information, thus avoiding damage to the original topological structure. It also supports differentiated embedding strategies for various geographic objects, balancing spatial accuracy with capacity requirements.

In this study, DE is adopted as the core mechanism for watermark embedding. The method is further enhanced by integrating the Thiessen polygon structure to optimize the selection of embedding points, thereby improving the overall robustness and restoration performance of the system.

2.4. Vector Geographic Information Data Structure (SHP)

In geographic information systems (GIS), points, lines, and polygons constitute the core expression framework of vector data, each with distinct processing methods yet closely interrelated. The SHP file format adopts differentiated storage and handling strategies for these three feature types, forming a complete spatial data representation system.

2.4.1. Point Features

Point features, as the most fundamental spatial entities, are stored in SHP files using a minimal data structure. Each record consists of a feature type identifier (1 for point) and a coordinate pair (x, y). For multipoint features, a sequence of coordinate pairs is stored. Although points lack geometric dimensions, their positional accuracy directly affects spatial analysis results. When embedding watermarks in point features, coordinate modifications are typically applied to the fractional part of the coordinates, with precision requirements dictated by the coordinate reference system. The topology of point features is relatively simple, primarily involving proximity analysis and spatial containment relationships. Therefore, watermarking algorithms must ensure that the relative spatial relationships among points remain essentially unchanged.

2.4.2. Line Features

Line features are represented by ordered sequences of points, with SHP files storing both the number of vertices and the coordinate sequence. For polylines, the SHP format employs the concept of Parts, allowing a single polyline to contain multiple non-contiguous segments. This design introduces two key considerations: (1) vertex density affects the smoothness and accuracy of the line; and (2) connections between parts require special handling. Watermark embedding in line features is generally applied to intermediate vertices, subject to two constraints: preserving the overall geometric shape of the line and limiting vertex displacement to avoid self-intersections. In practice, algorithms such as Douglas–Peucker are often used to identify characteristic vertices, prioritizing those whose modification has minimal impact on overall geometry.

2.4.3. Polygon Features

Polygon features are the most complex to process, as their storage must comply with strict polygon rules. In SHP files, each polygon consists of an exterior ring and optional interior rings (holes), with clearly defined containment relationships between rings. Three constraints are critical in polygon handling: (1) ring closure requires that the first and last vertex coordinates match; (2) ring orientation must be preserved—outer rings clockwise, inner rings counterclockwise; and (3) rings must not intersect. Watermark embedding for polygon features must account for these constraints, typically by prioritizing exterior ring vertices, restricting vertex displacement, and performing topological validation after embedding. Furthermore, since polygon area calculations can be sensitive to coordinate changes, watermarking operations must ensure that any area variation remains within acceptable tolerance limits.

The transformation relationships among points, lines, and polygons form an integrated processing chain. In practical applications, polygon boundaries may be converted into line features, and line vertices may be simplified into point sets. Such transformations impose specific requirements on watermark persistence: an ideal watermarking algorithm should maintain detectability across feature-type conversions. Moreover, given the prevalence of mixed feature types in real-world datasets, watermarking schemes must ensure cross-type compatibility so that watermarks embedded in points, lines, and polygons can coexist without conflict.

3. Methodology

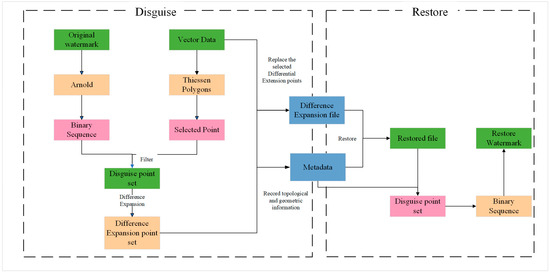

The proposed research framework comprises three main stages. First, the original watermark image is encrypted using the Arnold scrambling method to enhance security. Second, a Voronoi diagram is constructed from the vector geographic data, and feature points requiring difference expansion are selected based on the Voronoi structure. Difference expansion is then applied to these points, and the resulting disguised points are recorded in the metadata. Finally, the vector geographic data are restored from the difference-expanded version, and the disguised points are extracted for watermark recovery. The detailed workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overall workflow of the proposed reversible watermarking scheme for vector geographic data.

3.1. Arnold Scrambling Process

The original binary watermark image W is first processed using the Arnold transform, resulting in the scrambled watermark . The transformed image is then converted into a one-dimensional sequence where M denotes the length of the watermark.

3.2. Construction of the Voronoi Point Set

The vector geographic dataset V is first loaded, and the original coordinate set P is used to construct the Voronoi diagram. Candidate point pairs satisfying the embedding conditions are then selected from the Voronoi cells. The watermark image is converted into a binary sequence, where each bit determines the difference expansion operation: if the watermark bit equals 1, both points in the selected pair undergo difference expansion; if the bit equals 0, only the first point is expanded. The modified point set is subsequently updated in the corresponding shapefile (*.shp).

where denotes the Voronoi cell corresponding to point . The area of each Voronoi cell is then computed.

For the embedding point selection strategy, a density-adaptive approach is adopted. The point set P is sorted in ascending order according to the area of their corresponding Voronoi cells.

where . The first N points with the smallest areas (i.e., highest spatial density) are selected as the candidate embedding set.

For each candidate point , identify its nearest neighbor in P under the Euclidean distance.

Form the candidate point-pair set by pairing each candidate point with its nearest neighbor , ensuring that the pair meets the embedding criteria.

3.3. Metadata Recording and Restoration

In the proposed framework, metadata act as auxiliary records that support coordinate reconstruction in the reversible watermarking process. Each metadata entry consists of topological identifiers (feature ID, part index, vertex order) and geometric invariant descriptors (local edge-length ratios, turning angles, and normalized area ratios), forming a topology–geometry–coupled structure.

This design enables accurate vertex localization under geometric transformations, maintaining reliable recovery even when minor perturbations or partial metadata loss occur.

During the embedding phase, metadata corresponding to modified coordinates are serialized and encrypted using the AES algorithm to ensure confidentiality and integrity during transmission. During restoration, the metadata are decrypted and matched with the spatial topology to guide the inverse difference expansion.

The parity-check mechanism functions as a lightweight verification layer to detect inconsistencies between reconstructed and recorded coordinates, enhancing overall robustness without affecting reversibility. Each modified coordinate serves as an anchor point, whose metadata record provides the necessary topological and geometric references for reversible reconstruction.

3.4. Difference Expansion

In conventional GIS vector digital watermarking, the embedding process often incurs a certain degree of data quality degradation, making it difficult to meet the stringent fidelity requirements of high-precision geospatial datasets. Dynamic difference expansion, as an enhanced reversible watermarking technique—also referred to as lossless data hiding—retains the complete reversibility of the original difference expansion algorithm while introducing an adaptive mechanism to further improve precision control. The basic principle can be described as follows: For two spatially correlated adjacent data points p1(x1, y1) and p2(x2, y2), the difference d and mean mmm are first computed via a reversible transformation:

Here, ⎣.⎦ denotes the floor operation, and and are the integer coordinates obtained after precision-preserving processing (typically with ). The inherent spatial continuity of GIS vector data ensures that the distance between adjacent points remains small, causing the difference d to stay within a relatively narrow range in most cases.

The proposed algorithm introduces three key improvements over the conventional difference expansion method:

- (1)

- Dynamic expansion coefficient is adopted to adaptively adjust the expansion factor, ensuring that the coordinate offset always remains within the predefined threshold

- (2)

- Integer-first restoration strategy is applied, where all computations are performed on integer coordinates before restoring them to floating-point form, thereby strictly preserving the original numerical precision.

- (3)

- Integration with Voronoi-based spatial analysis enables intelligent selection of optimal embedding point pairs, improving the reliability of the embedding process.

Embedding process—Step 1: Coordinate preprocessing

For each candidate point pair (,)∈C:

Convert the coordinates into integer form by determining a scaling factor K based on the decimal precision of the input coordinates, where K is chosen as an integer power of 10:

Convert floating-point coordinates to integer coordinates.

For each coordinate dimension (process x and y separately):

Compute the difference d and the mean m:

Introduce the expansion factor t to adjust the intensity of difference expansion, constraining the perturbation range within (in floating-point scale).

Embed the secret bit .

Compute the new coordinates.

Restore the floating-point coordinates.

Ensuring lossless recovery of vector geographic data during the restoration process is achieved through a three-level verification framework that combines encrypted metadata with parity-check validation. This approach attains nearly 100% recovery accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. Following the difference expansion operation, the expanded points are first recorded into the metadata and stored, after which the metadata is encrypted using the AES algorithm. The main innovation of the proposed method lies in constructing a self-verifying watermark embedding framework that inherently enhances the reliability of both watermark extraction and data restoration.

3.5. Coordinate Watermark Detection and Restoration

Reversible coordinate watermarking in this study is achieved by adopting the Difference Expansion (DE) strategy during embedding and applying a combination of key-based decryption and parity verification during restoration. This approach enables high-accuracy coordinate reconstruction while preserving the reversibility of the watermarking process.

3.5.1. Key Decryption and Restoration Preparation

The user-provided key is first applied to decrypt the metadata, retrieving the watermark bit sequence and its corresponding indices. By matching the pseudo-random mapping derived from the key, the system reconstructs the complete embedding structure and generates positional references for coordinate recovery. If partial metadata corruption occurs, the system automatically switches to a selective restoration mode, restoring coordinates with valid metadata entries and marking unreliable ones with a confidence score derived from parity verification.

3.5.2. Difference Expansion Restoration

For each embedded coordinate pair , restoration is carried out as follows:

Integer rescaling:

Mean restoration:

Original integer pair reconstruction:

Floating-point coordinate recovery:

This process ensures a theoretically 100% coordinate restoration rate, provided that the metadata remains intact.

3.5.3. Parity-Check-Based Recovery

When anchor metadata serve as the structural reference for coordinate recovery, the system can tolerate limited corruption without global failure.

In scenarios where part of the anchor metadata becomes corrupted or unavailable, the system performs selective restoration based on metadata validity. Coordinates associated with intact metadata entries are fully restored, while missing or corrupted records are marked with a confidence score that reflects the reliability of their reconstruction.

This selective strategy enables the framework to maintain functional watermark recovery even under partial metadata loss.

For a 32 × 32 binary watermark (1024 bits), experimental results show that accurate recognition can be achieved as long as at least 448 bits (≈75%) are correctly recovered. Beyond this threshold, additional error-correcting codes—such as BCH or Reed–Solomon—can be integrated to further enhance robustness.

This progressive restoration mechanism ensures graceful degradation of watermark quality rather than complete failure, thereby extending the system’s resilience to metadata corruption.

3.5.4. Non-Embedded Point Handling

For coordinates without watermark embedding, the system preserves their original geometric configuration without modification, ensuring that the overall map maintains its visual integrity and positional accuracy.

3.6. Watermark Extraction

Step 1 Load Restored Vector Geographic Data:

Import the vector geographic dataset obtained from the reversible embedding recovery process.

Step 2 Reconstruct Thiessen Polygons:

Using the restored vector data, regenerate the Voronoi diagram. This step mirrors the initial point selection procedure used during watermark construction.

Step 3 Select Points:

Identify the relevant points from the reconstructed Thiessen Polygons based on the same selection criteria adopted in the embedding phase.

Step 4 Generate Scrambled Copyright Information:

From the selected points, construct a binary feature matrix of the vector data. Perform a bitwise XOR operation between this matrix and the zero-watermark image stored in the Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) system to obtain the scrambled copyright information.

Step 5 Descramble the Watermark Sequence:

Finally, apply the inverse scrambling process to the recovered watermark sequence, yielding the final watermark image.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Design and Implementation

The study employed representative vector geographic layer datasets as experimental subjects, covering major rivers, linear provincial and municipal boundaries, and primary road networks. All datasets were stored in the commonly used. shp format and represented in the WGS 84 geographic coordinate system (EPSG: 4326) with coordinate units in degrees.

These datasets encompass diverse geometric structures—including Polygon, MultiPolygon, Polyline, and MultiLineString—and therefore provide a standardized environment for controlled evaluation of reversibility and robustness. To ensure consistency and prevent projection-induced distortions, all embedding and restoration processes were conducted under this unified coordinate reference system.

Future work will extend the validation to global and multi-thematic datasets such as hydrological networks, land-use parcels, and OpenStreetMap to further assess scalability and general applicability.

The experimental workflow follows three main stages: (1) original data preparation, (2) difference-expansion watermark embedding, and (3) metadata-assisted restoration.

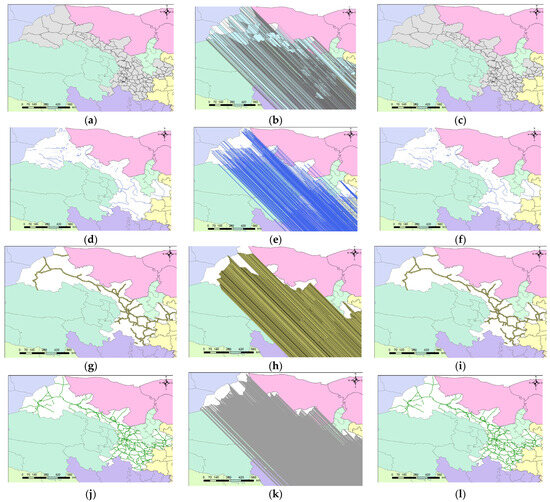

Figure 3 presents the side-by-side visualization of the four thematic datasets across these stages. Each row corresponds to one dataset, arranged from left to right as original, disturbed (after embedding), and restored (after extraction).

Figure 3.

Side-by-side visualization of vector geospatial datasets before and after reversible watermark embedding and restoration. (a–c) Administrative boundaries: (a) original, (b) disturbed after embedding, and (c) restored after extraction. (d–f) hydrological networks: (d) original, (e) disturbed, and (f) restored. (g–i) Expressway networks: (g) original, (h) disturbed, and (i) restored. (j–l) National and provincial roads: (j) original, (k) disturbed, and (l) restored. The three-stage visual comparison demonstrates that the proposed difference-expansion-based scheme preserves the geometric and topological integrity of the datasets while achieving full coordinate-level reversibility.

The visual comparison clearly demonstrates that the proposed difference-expansion-based scheme achieves complete coordinate-level reversibility while maintaining geometric and topological integrity. Even though the disturbed maps contain imperceptible coordinate perturbations, the restored versions successfully reconstruct the original spatial configuration with sub-pixel accuracy.

This confirms that the integration of difference expansion with AES-encrypted metadata recording and parity-check-based recovery provides both precision preservation and robust restorability for high-accuracy vector geographic data.

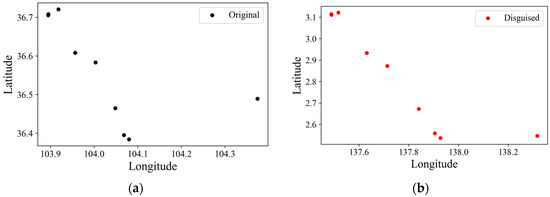

During the difference expansion phase, an expansion factor of 2 was applied to all selected coordinate pairs, with the embedded secret bit fixed to 1, ensuring controlled perturbation amplitude and full reversibility. Figure 4 illustrates the visualized results of the difference expansion camouflage applied to the four test layers, namely administrative boundaries, hydrological networks, national and provincial roads, and expressway networks. The visual comparison demonstrates that the embedded modifications are virtually imperceptible at the map scale, preserving the geometric continuity of spatial features while embedding the watermark information.

Figure 4.

Comparison of coordinates before and after difference expansion: (a) original vertex positions; (b) coordinates after difference expansion. The global spatial pattern remains consistent despite the controlled local perturbation, indicating good imperceptibility at the map scale.

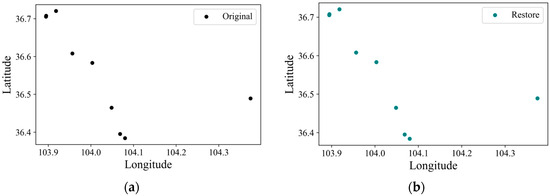

As shown in Figure 4, the vector layers subjected to difference expansion camouflage exhibit pronounced geometric distortions and substantial unrecognizable spatial noise, rendering the data unsuitable for direct application. Subsequently, a restoration process integrating metadata decryption and parity verification was employed to recover the camouflaged data. As illustrated in Figure 5, the overall spatial structure of the layers was effectively reconstructed, resulting in a substantial improvement in information usability.

Figure 5.

Comparison of coordinates before and after restoration: (a) original vertex positions; (b) restored coordinates after metadata-assisted decoding. The restored points nearly coincide with the originals, demonstrating coordinate-level reversibility with negligible numerical errors.

Under the condition that metadata remains fully available, the accuracy of the difference expansion and restoration algorithm was further validated by comparing original points with camouflaged points (Figure 4) and original points with restored points (Figure 5). The results demonstrate that the restored data exhibit negligible geometric deviations, with the spatial structure remaining intact and attribute fields preserved without loss, confirming the reliability of the proposed method in precision restoration.

When metadata is damaged or missing, the restoration process falls back to a parity-check-based recovery mode. Although this approach may introduce a small number of false positives, the overall error rate remains within 3%, ensuring no substantial impact on the accuracy of subsequent watermark extraction. A comparison of the watermark images before embedding and after extraction is shown in Figure 6, where (a) represents the original watermark image and (b) depicts the watermark extracted from the restored data. Both images exhibit a high degree of consistency in clarity and shape, meeting the expected performance.

Figure 6.

Comparison of watermark images before embedding and after extraction from restored data. (a) Original watermark prior to scrambling; (b) Watermark extracted after restoration. Both images show high visual consistency in clarity and shape, indicating that the restoration process preserves watermark integrity. The Chinese character “印” represents the embedded watermark text.

4.2. Invisibility

Invisibility is one of the key metrics for evaluating the performance of reversible watermarking algorithms, where the embedded watermark should cause minimal geometric distortion to the vector map. In this study, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is adopted to measure the precision loss, which is defined as:

where V and V′ denote the two sets of coordinates being compared, and N is the total number of vertices. A smaller RMSE indicates a smaller difference between the two datasets, while a larger value suggests greater distortion. When V and V′ correspond to the original and watermarked datasets, respectively, a lower RMSE reflects a smaller geometric error introduced during embedding.

To quantitatively assess the impact of the embedding and restoration processes on vector geospatial data accuracy, RMSE values were computed for two scenarios:

- (a)

- the difference between the original data and the watermarked (camouflaged) data, and

- (b)

- the difference between the original data and the restored data after watermark extraction.

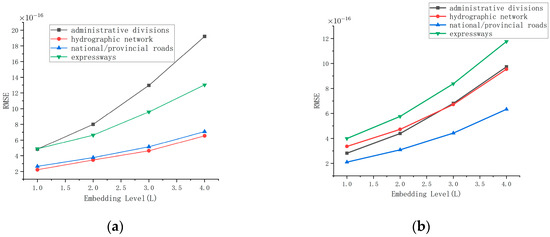

The experimental results are shown in Figure 7, where the x-axis represents the embedding level L, and the y-axis indicates the corresponding RMSE values. As the embedding level increases, the RMSE between the disguised and original datasets rises gradually, reflecting enhanced geometric perturbation under higher embedding intensity. However, in the restoration stage, the RMSE drops to the order of 10−16 through metadata-assisted decoding, effectively minimizing geometric discrepancies. These results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves high reversibility and excellent invisibility. Even under high embedding intensity, the original geometric structure can be reconstructed with nearly lossless precision, ensuring reliable protection for high-accuracy vector geospatial data.

Figure 7.

RMSE analysis of camouflaged and restored datasets across embedding levels: (a) RMSE between disguised and original data, showing increased geometric distortion with higher embedding levels; (b) RMSE after restoration, reduced to the order of 10−16 through metadata-assisted decoding, effectively eliminating geometric errors.

4.3. Reversibility

Reversibility is a key criterion for evaluating the effectiveness of reversible watermarking algorithms, ensuring that the embedding and extraction processes do not cause permanent alterations to the original data. To assess the reversibility of the proposed method, a coordinate-level encryption–decryption accuracy test was conducted. The procedure involved embedding the watermark into the spatial coordinates of the original vector data, extracting the watermark to restore the coordinates, and then performing a point-by-point comparison between the restored and original coordinates.

Table 1 presents a subset of the coordinate accuracy comparison results before encryption and after decryption. It can be observed that, for all tested points, both the X and Y coordinates are fully restored, with zero coordinate error. This demonstrates that, under the condition of intact metadata, the proposed difference expansion embedding mechanism achieves a 100% coordinate recovery rate without introducing irreversible spatial distortion.

Table 1.

Precision comparison before and after encryption.

Overall, the experimental findings confirm the high reversibility and geometric precision preservation of the proposed algorithm, making it well-suited for GIS data security applications where strict coordinate accuracy must be maintained.

4.4. Embedding Capacity

To evaluate the embedding capacity of the proposed reversible watermarking algorithm, three vector map datasets with varying geometric complexity were selected, namely provincial administrative boundaries, highway link segments, and mountainous road networks. For each dataset, the total number of vertices, the number of embeddable point pairs, and the corresponding maximum effective watermark capacity (in bits) were recorded, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maximum watermark capacity of different vector datasets.

Furthermore, to assess the adaptability of the algorithm to different watermark sizes, binary watermark images of various resolutions (32 × 32, 64 × 64, 128 × 128, and 256 × 256) were used in embedding experiments. The relationship between the embedding results and the capacity utilization rate was analyzed. This experimental design not only reflects the capacity performance of the algorithm under different spatial data complexities but also provides a reference for its potential deployment in diverse application scenarios.

The experimental results demonstrate a clear positive correlation between the geometric complexity of vector map data and the number of embeddable point pairs. Higher geometric complexity allows for more embedding points, leading to greater watermark capacity. Specifically, Dataset A supports the complete embedding of a binary watermark image with a maximum size of 128 × 128, whereas the relatively simpler Dataset C can only accommodate a 32 × 32 watermark. These findings confirm the adaptability and scalability of the proposed algorithm across spatial datasets of varying complexity, as well as its high embedding efficiency, making it suitable for effective deployment in diverse geospatial data protection scenarios.

4.5. Time Complexity

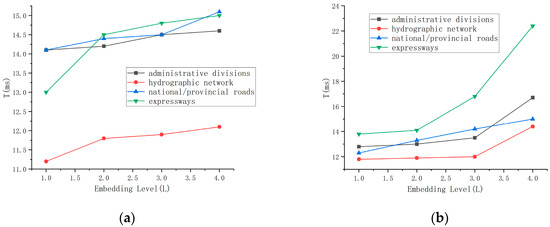

To evaluate the time complexity of the proposed algorithm, experiments were conducted on four different carrier maps to measure the execution time T (ms) for watermark embedding and detection at various embedding levels L, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Execution time analysis of watermark operations: (a) Embedding time across different embedding levels, showing a steady increase with higher L values; (b) Extraction time, significantly lower than embedding, reflecting the method’s low computational complexity and near-linear scalability.

The results indicate that, for a given map, execution time increases with higher embedding levels L; for a fixed embedding level, maps with larger numbers of vertices require more processing time. Since the watermark detection process does not involve computationally intensive operations such as peak value search, its execution time is significantly lower than that of embedding. Overall, the proposed method avoids high-complexity operations such as iterative computation or global sorting, resulting in nearly linear time growth for both embedding and extraction processes. This low time complexity and good real-time performance make the method suitable for practical applications requiring timely watermark embedding and detection.

4.6. Comparative Evaluation with Frequency-Domain Baseline

To establish a quantitative baseline, a DFT-domain quantization index modulation (QIM) watermarking method was implemented under identical payload conditions (2048 bits, 0.0070 bits/coordinate). With τ = 0.01, the DFT-QIM embedded 3 bits per frequency bin (M = 8, 683 bins). The resulting embedding distortion reached RMSE = 2.38 × 10−4, whereas the proposed difference expansion (DE) method achieved a distortion as low as 1.00 × 10−16, approaching floating-point precision.

This magnitude gap of over eight orders reflects the fundamental difference in embedding mechanisms:

DFT-based quantization modifies spectral magnitudes irreversibly, while DE performs pairwise coordinate adjustments that are mathematically invertible.

Consequently, DE enables perfect restoration of all vertex coordinates without introducing detectable perturbations, as confirmed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison between DFT-based and DE-based watermarking schemes under identical payload (2048 bits).

Across administrative, hydrographic, and road datasets, DE consistently restored all coordinates to their original values, confirming lossless reversibility.

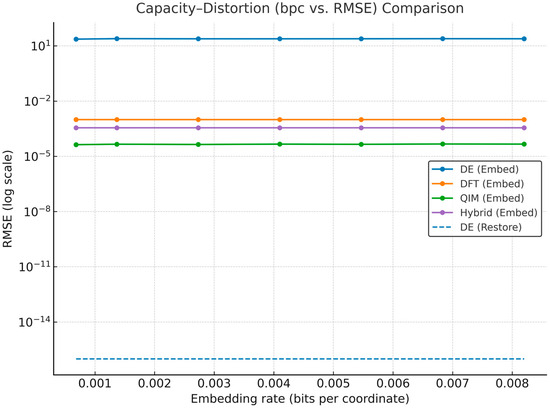

Furthermore, to quantitatively investigate the relationship between embedding capacity and geometric distortion, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was analyzed under varying embedding rates for all four watermarking frameworks (DE, DFT, QIM, and Hybrid).

As illustrated in Figure 9, the proposed DE-based scheme maintains a near-constant RMSE of approximately 10−16 across all embedding rates, demonstrating perfect reversibility and precision preservation.

Figure 9.

Capacity–distortion comparison among DE, DFT, QIM, and Hybrid watermarking methods.

In contrast, DFT-, QIM-, and Hybrid-based schemes show monotonic growth in distortion with increasing embedding density, reflecting the inherent trade-off between capacity and imperceptibility.

This finding highlights that the DE method can simultaneously achieve high embedding capacity and minimal distortion, outperforming frequency- and hybrid-domain baselines by several orders of magnitude. This demonstrates that reversible watermarking in the spatial domain can maintain both precision and security—two objectives that traditional frequency-domain schemes cannot achieve simultaneously.

4.7. Comparative Performance Among DFT, QIM, Hybrid, and DE Schemes

To further evaluate overall trade-offs, four representative watermarking frameworks were compared under a uniform embedding rate (0.0070 bpc):

DFT-based, spatial QIM, hybrid domain, and the proposed DE-based reversible watermarking.

The comparative indicators in Table 4 reveal distinct trends.

Table 4.

Comprehensive performance comparison among DFT, QIM, Hybrid, and DE watermarking methods (embedding rate = 0.0070 bpc).

In terms of imperceptibility, DE achieved a distortion of 2.21 × 10−16, significantly lower than DFT (2.38 × 10−4), QIM (3.28 × 10−6), and Hybrid (8.49 × 10−5).

This confirms that DE preserves the geometric and topological integrity of vector datasets. Under no-attack conditions, all methods correctly recovered the embedded watermark (BER = 0%), proving functional correctness.

For robustness, DE maintained the lowest bit error rates against most perturbations, with only minor degradation under severe operations.

DFT remained rotation-invariant but non-reversible, QIM performed moderately under noise but degraded under affine distortions, and the hybrid method suffered unstable performance.

These findings demonstrate that DE provides a balanced triad of high precision, visual invisibility, and robustness—without sacrificing reversibility—making it a more practical solution for copyright verification.

4.8. Comparative Performance Analysis Among DFT, QIM, Hybrid, and DE Schemes

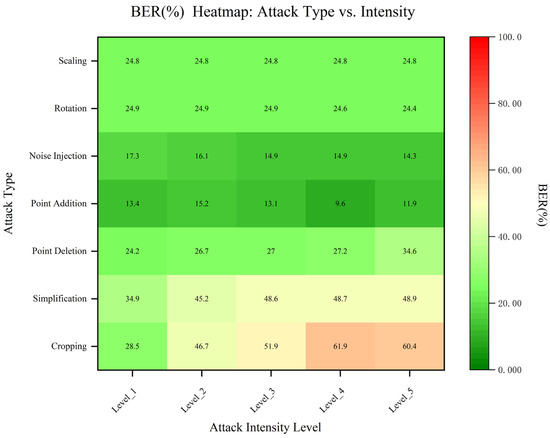

To comprehensively assess geometric robustness, seven distortion models were tested: point addition, noise injection, rotation, scaling, point deletion, simplification, and cropping. The results in Figure 10 and Table 5 reveal consistent degradation patterns.

Figure 10.

Heatmap of bit error rates (BER) for the DE watermarking scheme under seven geometric and affine attack types.

Table 5.

Extracted watermark images under different geometric attack intensities (10–50%). The Chinese character “印” represents the embedded watermark text.

DE achieved strong resilience across all moderate attacks, with BER < 30% in five of seven scenarios (12.64–27.93%). For more destructive distortions such as simplification and cropping, BER increased to ~45–50%, but the extracted watermark images remained structurally recognizable, even under 50% distortion intensity. This indicates that the scheme exhibits graceful degradation—a gradual loss of fidelity rather than catastrophic failure—which is essential for practical forensic verification.

The trend plots show an approximately linear increase in BER with attack strength, suggesting bit-level stability and error locality: errors cluster near perturbed vertices rather than propagating globally. Such localized degradation confirms that the DE embedding is inherently stable under affine perturbations.

Overall, DE demonstrates a robust yet fully reversible watermarking mechanism suitable for secure vector data exchange and copyright tracking.

5. Discussion

5.1. Broader Implications and Reflections

The proposed reversible watermarking framework bridges the gap between high-precision coordinate preservation and robust copyright protection in vector geospatial data. Unlike traditional frequency-domain or non-reversible embedding methods, the presented approach achieves lossless recovery while maintaining both geometric and topological integrity.

Compared with the RST-invariant reversible watermarking proposed by Wang [38], which focuses on resisting geometric transformations such as rotation, scaling, and translation, the present work prioritizes coordinate-level precision and topological consistency, offering complementary advantages in high-accuracy GIS applications. Moreover, in contrast to the self-error-correction mechanism proposed by Qiu et al. [39], which enhances restoration reliability through bit-level redundancy, our metadata-assisted design explicitly defines the recoverability boundary under metadata degradation while ensuring complete coordinate reversibility.

This advancement has important implications for secure data exchange and verifiable ownership in national mapping, land management, and autonomous navigation systems where spatial accuracy is crucial. The integration of difference expansion, Voronoi-based analysis, and metadata-assisted recovery demonstrates that reversible watermarking can be both technically feasible and practically deployable without compromising dataset precision.

These findings contribute to the broader goal of trustworthy spatial data infrastructure (SDI) and provide a reusable foundation for reversible authentication in other structured data modalities such as CAD, BIM, and 3D GIS. As shown in Figure 8, the execution time of the DE-based embedding increases approximately linearly with embedding level across all dataset types, confirming the algorithm’s O(N) complexity. The absolute execution time remains within tens of milliseconds, demonstrating its efficiency for real-time GIS watermarking.

5.2. Limitations and Future Work

Current experiments were conducted on medium-scale administrative and transportation datasets for controlled evaluation. Future studies will extend to large-scale and multi-layer GIS environments (e.g., OpenStreetMap and national archives) to assess computational scalability and adaptability to complex topologies.

Additionally, multi-scale vector hierarchies will be examined to evaluate embedding throughput, memory efficiency, and restoration accuracy under distributed frameworks such as GeoPandas–Dask. The proposed watermarking method maintains full structural compatibility with standard ESRI Shapefiles and commercial GIS (ArcGIS 10.8, QGIS 3.28), ensuring smooth integration into existing workflows.

Subsequent work will explore automated plug-in modules for batch watermarking and verification in real-world GIS pipelines, as well as the introduction of redundant anchor placement and error-correcting codes to enhance resilience against metadata corruption.

5.3. Ethical and Legal Considerations

As with all watermarking technologies, potential misuse must be acknowledged. Unauthorized embedding of watermarks into sensitive geospatial data could lead to ownership ambiguity or privacy violations. To mitigate such risks, deployment should remain within authorized and auditable environments with appropriate access control and provenance tracking.

The proposed method is intended solely for legitimate copyright protection and data verification, fully compliant with institutional and legal standards.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a reversible watermarking framework that integrates difference expansion, Voronoi-based structural analysis, and metadata-assisted restoration to ensure both high-precision coordinate recoverability and robust copyright protection for vector geographic data.

The metadata module serves as a secure and structural anchor for coordinate restoration, combining AES encryption for confidentiality and a parity-check layer for verification. In cases of partial metadata loss, a selective restoration strategy maintains functional watermark recovery with graceful degradation rather than complete failure. Experimental results demonstrate that the method achieves near-zero embedding distortion, perfect reversibility under intact metadata, and high resilience to geometric attacks including rotation, scaling, and point deletion.

Beyond technical performance, the proposed framework provides a practical path toward secure and traceable data exchange in GIS applications such as national mapping, land resource management, and autonomous navigation. Future work will focus on extending this framework to large-scale and multi-layer geospatial datasets (e.g., OpenStreetMap) and on integrating redundant anchors and error-correcting codes for further metadata robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W. and L.-M.G.; methodology, Q.W.; software, Q.W.; validation, Q.W. and L.-M.G.; formal analysis, Q.W.; investigation, Q.W.; resources, L.-M.G.; data curation, Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W.; writing—review and editing, L.-M.G. and L.Z.; visualization, Q.W.; supervision, L.-M.G.; project administration, L.-M.G.; funding acquisition, L.-M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University Faculty Innovation Fund Project, grant number 2024B-114.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their institution for providing technical and administrative support during this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT (GPT-5) to assist with language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hou, X.; Min, L.; Yang, H. A reversible watermarking scheme for vector maps based on multilevel histogram modification. Symmetry 2018, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ren, N.; Zhu, C. Precise Authentication Watermarking Algorithm Based on Multiple Sorting Mechanisms for Vector Geographic Data. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhu, C.; Ren, N.; Chen, W.; Gong, W. Zero watermarking algorithm for vector geographic data based on the number of neighboring features. Symmetry 2021, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, L.; Tan, T. A zero-watermarking algorithm for high-precision maps based on feature invariant. Geogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 40, 811–823. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, N.; Guo, S.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y. A zero-watermarking scheme based on spatial topological relations for vector dataset. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 226, 120217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Martin, M.; Swanlund, D. MapSafe: A complete tool for achieving geospatial data sovereignty. Trans. GIS 2023, 27, 1680–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Gao, S.; Mai, G.; Janowicz, K. Building privacy-preserving and secure geospatial artificial intelligence foundation models (vision paper). In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 13–16 November 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Q.; Li, K.-Q.; Fu, J.-L.; Liu, Y. Hybrid LBM and machine learning algorithms for permeability prediction of porous media: A comparative study. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 172, 106163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Babovic, V. Multi-site multivariate downscaling of global climate model outputs: An integrated framework combining quantile mapping, stochastic weather generator and Empirical Copula approaches. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 5593–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Su, J.; Zhu, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S. Reconstructing unsaturated infiltration behavior with sparse data via physics-informed deep learning. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 172, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, B.Z.; Karaoulis, M. Data fusion of geotechnical and geophysical data for three-dimensional subsoil schematisations. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 52, 101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yu, T.; Dong, P. A new perspective on determination of the critical slip surface of three-dimensional slopes. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 144, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Z. A DCT-based blind watermarking algorithm for vector digital maps. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 179, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Xu, D.; Li, C.; Sun, J. Watermarking GIS data for digital map copyright protection. In Proceedings of the 24th International Cartographic Conference, Santiago, Chile, 15–21 November 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Q. A construction of digital watermarking model for the vector geospatial data based on magnitude and phase of DFT. J. Beijing Univ. Posts Telecommun. 2011, 34, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Wang, Q. The study of watermarking algorithm for vector geospatial data based on the phase of DFT. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Information Security, Beijing, China, 25–27 June 2010; IEEE: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, C.; Du, J.; Xi, X.; Tian, H.; Zhang, J. A hybrid domain-based watermarking for vector maps utilizing a complementary advantage of discrete Fourier transform and singular value decomposition. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 183, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Men, C. Reversible fragile watermarking for 2-D vector map authentication with localization. Comput.-Aided Des. 2012, 44, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Men, C. Reversible fragile watermarking for locating tampered blocks in 2D vector maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2013, 67, 709–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Reversible watermarking for 2D vector maps based on normalized vertices. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 20935–20953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubahia, A. Spatial Data Mining Approaches for GIS Vector Data Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, M.; Busch, C. Watermarking 2D-vector data for geographical information systems. In Security and Watermarking of Multimedia Contents IV, Proceedings of the Electronic Imaging, San Jose, CA, USA, 20–25 January 2002; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2002; Volume 4675, pp. 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, G.; Voigt, M. A high capacity watermarking system for digital maps. In Proceedings of the 2004 Workshop on Multimedia and Security, Magdeburg, Germany, 20–21 September 2004; pp. 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.T.; Shao, C.Y.; Xu, X.G.; Niu, X. Reversible data-hiding scheme for 2-D vector maps based on difference expansion. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2007, 2, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kwon, K.R. Vector watermarking scheme for GIS vector map management. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2013, 63, 757–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Men, C. A high capacity reversible data hiding method for 2D vector maps based on virtual coordinates. Comput.-Aided Des. 2014, 47, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafaye, J.; Béguec, J.; Gross-Amblard, D.; Ruas, A. Blind and squaring-resistant watermarking of vectorial building layers. GeoInformatica 2012, 16, 245–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zope-Chaudhari, S.; Venkatachalam, P.; Buddhiraju, K.M. Copyright protection of vector data using vector watermark. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 23–28 July 2017; IEEE: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2017; pp. 6110–6113. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W. A normalization-based watermarking scheme for 2D vector map data. Earth Sci. Inform. 2017, 10, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncel, V.R.; Nikolaidis, N.; Pitas, I. An optimal detector structure for the Fourier descriptors domain watermarking of 2D vector graphics. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2007, 13, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Xi, X.; Du, J.; Wu, T. Robust watermarking scheme for vector geographic data based on the ratio invariance of DWT–CSVD coefficients. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xiao, Q.; Luo, J.; Duan, H. Construct self-correcting digital watermarking model for vector map based on error-control coding. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2025, 50, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Min, L.; Tang, L. Fragile watermarking algorithm for locating tampered entity groups in vector map data. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2020, 45, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Zhu, C.; Ren, N.; Hu, Y. Vector geographic data commutative encryption and watermarking algorithm based on prediction differences. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Zhu, R.; Du, P. Combinational spatial and frequency domains watermarking for 2D vector maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 31375–31387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, C. A multiple watermarking algorithm for vector geographic data based on coordinate mapping and domain subdivision. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 19261–19279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Ding, K. Multiple watermarking algorithms for vector geographic data based on multiple quantization index modulation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, X.; Xie, C. RST invariant reversible watermarking for 2D vector map. Int. J. Multimed. Ubiquitous Eng. 2016, 11, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zheng, J. A self-error-correction-based reversible watermarking scheme for vector maps. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).