Abstract

The Poisson distribution is a discrete probability model, widely used in science and engineering to describe various natural and man-made phenomena. It possesses an important feature, namely being inherently asymmetric, but as its parameter becomes large, the distribution becomes approximately symmetric. To broaden its use, multiple extensions and variations have been developed. Determining whether a data set follows a Poisson distribution involves hypothesis testing at a chosen significance level. When sampling from a Poisson distribution, confidence intervals provide an estimated range instead of a single value. Due to the discrete nature of the Poisson distribution, confidence intervals cannot be derived from a simple formula, and are therefore computed using specialized algorithms. In this paper, three alternatives are given and discussed.

Keywords:

Poisson distribution applications; Poisson distribution testing; Poisson distribution confidence intervals; Poisson distribution modifications; Poisson distribution generalizations MSC:

60E05; 62E17

1. Introduction

A common approach to approximate the value of a function at a point is to express it as a (typically infinite) series called the Taylor series [1]:

where denotes the derivative of f. A special case arises when , which is known as the Maclaurin series [2], although Euler examined similar expansions around the same period [3]. A notable property of the exponential function is that it equals its own derivative. Applying Equation (1) to with yields:

Using Equation (2), it is straightforward to verify that the function in Equation (3) describes an infinite series over whose sum equals 1:

This defines the Poisson distribution [4]. For a Poisson process with an expected number x of events occurring in a given interval, the probability of observing z events in that interval is given by .

The skewness of the Poisson distribution is , meaning the distribution becomes more symmetric as z increases, but it is never perfectly symmetric as long as it has support only on non-negative integers. In other words, since probabilities for negative values are zero, the exact symmetry around a center is broken.

2. Literature Survey

Simon Newcomb [5] applied the Poisson distribution in 1860 to model the number of stars observed within a unit of space. Later, in 1898, Ladislaus Bortkiewicz [6] demonstrated that the occurrence of soldiers in the Prussian army accidentally killed by horse kicks followed a Poisson distribution closely.

One of the simplest methods to generate Poisson-distributed values relies on the uniform distribution. Various algorithms exist for this purpose, with two examples being presented in this paper, in Algorithms 1 and 2.

| Algorithm 1: Knuth’s [7] algorithm on generating a Poisson-distributed series |

| Input: z //Real value, see Equation (3) |

| Algorithm 2: Devroye’s [8] algorithm on generating a Poisson-distributed series |

| Input:

z //Real value, see Equation (3) |

Applications of the Poisson distribution are across several fields.

2.1. Physics and Engineering

Particle Physics and Quantum Mechanics are addressed with particle collision events in Brownian motion [9], asteroid impacts [10], particle clusters [11], electron–positron pair creation in relativistic heavy-ion collisions [12], and other various quantum phenomena [13]. In quantum systems, it describes photocurrent zero-axis crossings in Cassinian oscillators [14], particle dwell times in low-temperature defects [15], and virtual charged pair counts in mesoscopic capacitor theory [16]; the distribution also applies to quantum eigenstate level spacing analysis when uncertainty is sufficiently small [17].

Electromagnetic radiation and Photon Counting Light scattering applications include modeling photon bounces from Earth’s surface in laser altimetry systems [18], particularly in Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar operations [19]. The distribution describes photon counts in various detection systems [20], UV background measurements [21], and stellar occultation events [22]. For radiation emission, it models X-ray photon emission patterns [23] and photon numbers in weak coherent light pulses [24].

Radioactive Decay and Cosmic Phenomena are subject to modeling too. Even if radioactive particle emission technically follows the Ruark–Devol distribution [25,26,27], it is commonly approximated using Poisson distributions for practical applications [28]. In cosmic ray physics, the distribution models particle density [29], flux measurements through detectors [30], and air shower observations [31]; it also describes cosmic ray cluster multiplicities at ultrahigh energies [32], and emission patterns from luminous sources over time [25,26,27].

Astronomical Object Counting is addressed with counting of various celestial objects, including halos per mass bin in cosmic surveys [33], primordial black holes [34], galaxies within dark matter halos [35], and even hypothetical artificial broadcasts from extraterrestrial intelligences [36].

Signal Processing and Manufacturing is addressed with spatio-temporal backhopping in magnetic memory arrays [37], sensor surface binding events in magnetic bead detectors [38], and quantum noise in optical transmission [39]. Manufacturing is covered with spatially uncorrelated defect distribution analysis [40,41], component volume defects classified by size and type [42], and new product development counts across firms [43].

2.1.1. A First Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Physics

In [10], it is assumed that a potential target object, such as a planet or a specific asteroid, is in a heliocentric orbit in which it can collide with other asteroids or with comets. The assumption is that the orbit of this target passes through a region of space which can be characterized as having a constant spatial density of objects with which the target can collide. For such a Poisson ensemble of objects, it follows that a model based on the Poisson distribution is constructed and describes the probability of a collision. Following particle-in-a-box modeling, it is assumed that the target and surrounding asteroids are all simply points rather than extended objects. Spatial distribution of asteroids with respect to the target at a random instant of time is characterized by the Poisson distribution and the probability of finding no asteroids in a sphere of volume V centered at the target is given by Equation (3) with and .

2.1.2. A Second Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Physics

In [33], a differentiable and physics-informed neural network is introduced, which can generate a computationally generated catalog of dark matter halos designed to simulate observations of the universe’s large-scale structure. In doing that, , the number of halos per mass bin and per cubic element (where i is the index of the cubic element and is the mass bin) is assumed to be distributed by Poisson law, model identified by fixing and in Equation (3), and with denoting the Poisson intensity.

2.1.3. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Engineering

Spin-transfer-torque magnetic random-access memory is used for embedded non-volatile memory applications. At high biases, these memories can anomalously increase owing to the switching back or flipping of the magnetization phenomenon commonly referred to as backhopping, undesirable for memory applications. However, the phenomenon gained attention for its potential in spiking neural network applications. In [37], it was found that the probability of backhopping follows a Poisson distribution (Equation (3)) characterized by the rate of backhopping ().

2.2. Transportation and Network Systems

In Vehicle and Aircraft Movement, Poisson distribution effectively models irregular arrival patterns for aircrafts [44], cars [45], and sea ships [46,47,48,49,50] at various transportation hubs. It is particularly useful for analyzing flight delays [51,52], cancellations [53], and service desk operations [54]; the memoryless property makes it ideal for modeling unpredictable arrival scenarios [55,56].

Traffic Flow Analysis is included with highway traffic analysis, when Poisson distribution is applied to vehicles moving in infinitely long lines without traffic controls [57], when predicting overtaking probabilities over time. However, its validity depends on traffic density remaining below critical thresholds, ranging from 600 to 800 vehicles per hour [58,59,60]; the distribution also models inter-vehicle spacing [61] and serves as the foundation for traditional telephony network traffic analysis [62].

Communication systems applications include network traffic with user session arrivals [63], legitimate internet traffic patterns [64,65], and packet reception counts [66]; the distribution proves valuable for capacity planning and server load management in web systems [67]. Email spam retrieval rates also follow Poisson patterns when spammer lists are large and retrieval rates remain constant [68,69]. Phone call modeling includes both incoming switchboard calls [70] and bidirectional calling patterns with variable frequencies [71]; mobile communication applications cover GSM signal paging [72], call logging with time quantization [73], active phone counts per cell area [74], and base station traffic analysis [75].

2.2.1. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Transportation

The problem of determining the optimal number of berths is addressed in [46], considering both service and waiting costs for ships. When the ship arrival rate at the seaport is lower than the service rate (the number of ships handled per unit time), some berths remain idle, reducing the overall service efficiency. Conversely, if the arrival rate exceeds the service rate, ships will form a queue, modeled probabilistically by Equation (3), with z the average number of arrivals and x the number of ships arriving in a seaport in specific time.

2.2.2. A Case Study of the Poisson Distribution Use in Network Systems

Considering that uplink Global System for Mobile Communication power is dependent on the number of nearby mobile phones in an active call, in [74], a nearby approach with mobile phones only in a 10m radius is considered. In this instance, the number of active mobile phones was modeled using the Poisson distribution (Equation (3)), with a mean value , where three mobile phones talking in the 10 m radius were used. Consideration was given to typical places where Radio Frequency Identification systems can be used, such as schools and universities, hospitals, supermarkets, public transportation, and sports events. In this instance, was the number of mobile phones in the selected area.

2.3. Biology and Medicine

Safety and Risk Assessment is addressed by accident modeling when areas are divided into grid patterns where accident counts per quadrat follow the Poisson distribution [76]; however, careful application is required, since the distribution assumes constant hazard rates and does not account for changing risk factors following incidents or seasonal variations in accident-producing conditions [77].

Genetic and Cellular Processes are addressed with DNA mutation analysis using Poisson modeling for mutagenesis rate [78] and mutation frequency data [79], though actual mutant distributions often follow the Luria–Delbrück pattern [80,81,82,83]; the distribution models DNA lesion counts [84] and HPRT gene mutations in lymphocyte cultures, using 96-well plate assays with colony formation analysis [85].

Healthcare System Operations are well addressed, since hospital systems extensively use Poisson modeling for emergency department arrivals [86], obstetric patient flow [87], and disease-specific admission patterns like asthma hospitalizations [88] and annual expected number of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cases by town [89]; the distribution’s appropriateness stems from arrivals representing independent medical incidents from many individuals, each using services infrequently [90].

Disease Surveillance and Outbreaks are addressed with epidemic modeling, employing distributed lag models with Poisson-weighted parameters corresponding to disease-specific incubation periods [91,92], space–time permutation scan statistics, which use Poisson assumptions for early outbreak detection through hospital visit monitoring [93], and modeling case numbers for specific diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis across geographic regions [89].

Medical Error Analysis is addressed with healthcare quality assessments, applying the Poisson distribution to model the intensive care unit medical errors [94], adverse event frequencies [95], emergency department visit patterns, and prescription error rates [96]; models for healthcare worker burnout and depression rates when analyzing workplace safety factors are also reported [97,98,99].

Environmental Health is addressed through natural disaster impacts analysis when Poisson patterns were reported for meteorological threshold exceedances [100], post-disaster suicide rates [101], and catastrophic event frequencies [102], providing frameworks for public health emergency planning.

2.3.1. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Biology

The time evolution of deoxyribonucleic acid damage was placed under scrutiny in [84]. With the Microdosimetric Kinetic Model, the initial distribution of lethal lesions was Poissonian (Equation (3)). When given a cell nucleus, composed by domains, the probability that events deposit an energy z obeys a Poissonian distribution of mean , being the mean energy deposition on the nucleus, and the first moment of the single event distribution, either computed numerically via Monte Carlo or by experimental microdosimetric measurements.

2.3.2. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Medicine

In [94], medical error rates were calculated as the number of medical errors divided by patient-days and number of admissions, when the overall medical error rates were compared between the preintervention (traditional fluorescent) and postintervention (blue-enriched) lighting conditions, assuming that the number of medical errors followed a Poisson distribution (Equation (3)), given the length of stay.

2.4. Economics and Commerce

Customer Behavior Analysis is included with commercial applications modeling transaction item counts [103,104], customer purchase frequencies over time periods [105], and website visitor arrivals for online businesses [106]; the distribution also describes demand patterns for spare parts [107], customer churn prediction [108], and unplanned category purchases during shopping trips [109].

Retail Operations is included with store traffic modeling for online retailing patterns [110], standard product demand at retail locations [111], and shopping intensity, measured by store visit counts in mall environments [112]; these applications help optimize staffing, inventory, and facility management.

Product Lifecycle Management is included with return product analysis using Poisson modeling for reusable product demand and return streams [113,114], return timing patterns [115], and customer-to-customer non-returned item counts [116]; this supports reverse logistics planning and warranty cost estimation.

Service Industry Applications is addressed through call center operations, relying heavily on Poisson modeling for daily and hourly call volume prediction [104,117], banking customer service arrival patterns [86], and capacity planning [67]; the distribution’s memoryless property aligns well with independent customer service needs arising from separate individual circumstances.

2.4.1. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Economics

In [104] is considered an inhomogeneous Poisson model with arrival rate incorporating both strong within-day patterns and day-to-day dynamics, modelled separately and combined in a multiplicative model. If is the number of arrivals to the queue on day during the time interval , with the kth period in the day, the model is obtained by substituting in Equation (3), where is the arrival rate for day j and period k.

2.4.2. A Case Study of Poisson Distribution Use in Commerce

In [116], it is assumed that customers arrive according to a Poisson process with rate during time interval for , and the demand is satisfied at the end of the period, generating a quantifiable revenue per customer. Meanwhile, for items purchased in time period, the number of returns follows a binomial distribution.

3. Testing for Poisson Distribution

A variety of tests is available for testing whether a sample of observations comes from a Poisson distribution. An additional test based on variance stabilizing transformation from [118] is as follows.

If , …, are independent non-negative integer valued random variables with , the basic null hypothesis of interest is that

where .

With and , the statistic for testing vs. can be [119]:

where:

- is conditional (chi-squared) statistic, relying on the fact that, under null hypothesis, the conditional distribution of , …, given is multinomial (each of the draws having chance);

- has an approximately non-central distribution with non-centrality parameter ;

- is based on the Bartlett–Anscombe statistic [118,120];

- , or, even better, , with N being the normal distribution and t being the student distribution.

4. Working with the Poisson Distribution for Unique Observations

Since Poisson is a discrete distribution, one cannot (in general) find values of and such that the probability exactly (or any other coverage). The median is defined as the infimum value for such that , since the probability will generally not equal 50% exactly [121]. One can see this as a 50% confidence interval, with and . It is known that there is no closed-form expression for the median of the Poisson distribution, but there are upper and lower bounds [122].

In a Poisson distribution (see Equation (3)), a certain number of events (let y be that number) are observed over a time interval (an arbitrary value: let us say 1 year). What is the probability of observing events? Or more specifically, with being set (what follows works with any arbitrary level of significance), what is the range of possible observations with % (95%) probability? In this section, the paper will try to provide an answer to this question.

Before proceeding with math, note the following remarks:

- The working hypothesis (what is known) is that the observed number of events follows the Poisson distribution;

- It is not a repeated experiment; more precisely, the repetition of the experiment was not performed;

- As stated in the Poisson experiment, the population (of the occurring events) is infinite, but even so, only one observation was made (the occurrence of y events was observed);

- The parameter of the distribution (z in Equation (3)) is unknown and we need to estimate it.

One would think to estimate z from the formula of the population mean, while another would try to maximize the likelihood. The truth is that the same result will be obtained:

The likelihood (Equation (9)) shows that . So the problem is expressing the confidence interval around y having % probability coverage.

The main issue is that, just as with the first observation, any further observation will also obtain a non-negative integer as the number of events in the specified timeframe (of 1 year). Thus, the boundaries of the (closed) confidence interval should also be non-negative integers. Let and be the boundaries of the confidence interval. This means that:

Equation (10) expresses the fact that a simple, obvious solution to the problem exists, since the sum is built up from discrete quantities; adding some may obtain a value below 0.95, and adding something more may result in a value above 0.95, with no implicit criteria of which solution to be retained. The following example is used to clarify the issue:

It makes sense to express the 95% CI for x from Poisson(x;2) as [0, 4] (the true coverage of [0, 4] is about 0.94735) or [0, 5] (the true coverage of [0, 5] is 0.98334). However, without additional information or constraint, one cannot decide which interval best expresses the expected 95% CI. In some instances, an interval of at least 95% coverage is needed (and then [0, 5] is the solution), while in other instances, the nearest solution is preferred (and then [0, 4] is the solution).

However, one should note that Table 1 is (just an example and) a simplified case in which investigating the lower CI boundary was not necessary because Poisson(0;2).

Table 1.

PMF for Poisson(x;2) and its CDF and 1−CDF.

4.1. Algorithm for CI

The algorithms reported for binomial distribution [123] were adapted to obtain boundaries for the Poisson distribution too (Algorithms 3–5). Since there is no upper limit for the value of a variable from Poisson distribution, the following algorithms are using a special construction, a finite representation of the CDF, which have contained the expected coverage interval in it. This is possible all the time for any imposed level, since the Poisson distribution diminishes its probability with the increasing value of the variate (Equation (11)).

| Algorithm 3: Algorithm for minimal effort (adapted from A1 in [123]) |

| Input data: x, α // the Poisson parameter, the significance level Output data: nl, nu, ne // the CI boundaries, the true coverage //See Equation (11) //Always |

| Algorithm 4: Algorithm for minimal departure (adapted from A2 in [123]) |

| // the Poisson parameter, the significance level // the CI boundaries, the true coverage //See Equation (11) |

| Algorithm 5: Algorithm for the closest but not greater significance (adapted from A3 in [123]) |

| // the Poisson parameter, the significance level // the CI boundaries, the true coverage //See Equation (11) |

4.2. Theoretical Analysis of Algorithms 3–5

Algorithms 3–5 were designed to compute CIs for the Poisson distribution parameter with a range of significance levels . Each algorithm adapts classical approaches to find minimal coverage or significance departure, ensuring the constructed intervals meet desired confidence levels effectively.

The algorithm for minimal effort (Algorithm 3, adapted from A1 of [123]) begins with the exact Poisson cumulative probabilities for a Poisson parameter x and significance level . It iteratively adjusts the lower and upper bounds of the CI to maintain the coverage probability (where is the summation of the tail probabilities outside the interval) just reaching or exceeding . The routine balances the interval symmetrically by comparing probabilities at the boundaries, and expands or contracts the interval with minimal effort to achieve nominal coverage. This approach ensures continuous intervals without gaps, and enlarges the interval only to the minimal extent necessary to achieve the required coverage. The loop terminates when coverage is adequate or when boundaries reach the global range. The complexity is proportional to the number of counts m in r, ensuring accuracy with efficient trimming.

The algorithm for minimal departure (Algorithm 4, adapted from A2 of [123]) refines the output of the minimal effort algorithm (Algorithm 3) by iteratively testing whether removing extreme values from the interval (either from or from ) reduces the departure of the coverage from the nominal level. It prioritizes moves that reduce the absolute difference . By minimizing the absolute coverage error, this algorithm can produce intervals closer to the nominal coverage, but may stop early if further improvements are not beneficial. This strategy gives a local search for minimal deviation, providing potentially tighter intervals than minimal effort by balancing under- and over-coverage considerations.

The algorithm for closest but not greater significance (Algorithm 5, adapted from A3 of [123]) further adjusts the interval found by the minimal departure algorithm (Algorithm 4), expanding it if the current coverage is less than the nominal , stopping as soon as coverage reaches or exceeds , but never exceeding it. Algorithm 5 tries to obtain coverage as close as possible to the intended confidence level without going beyond it, thus strictly controlling type I error under the nominal level, being useful in hypothesis testing where exact control of the significance level is critical, and ensuring the CI is not overly conservative.

Algorithms 3–5 provide iterative optimization routines for discrete distributions since exact coverage calculation and discrete steps pose challenges, relying on cumulative probabilities and carefully adding or removing points to minimize coverage error, length, or deviation from the significance threshold.

Lower and upper boundaries ( and in Algorithms 3–5 as integers), as well as true coverage (, as probability), are collected by the algorithms. Each algorithm is given as a refinement of the solution proposed by the previous one.

An important behavior is related to monotony. All algorithms provide monotonic increases in the boundaries. To show this fact, the first nine confidence intervals are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

CI for Poisson(x; x) with Algorithms 3–5 and their true coverages for .

The monotonicity in the and series is visible for all three algorithms for the first nine confidence intervals expressed in Table 2. Furthermore, the and series are monotone for the values of x till 500, where this simulation ended. The same monotony applies to the width of the confidence interval—all proposed solutions provide monotonic increases in the width of the confidence interval till 500, where this simulation ended. It is thus very likely that the monotonies are to be kept for any arbitrary value of x.

However, the solutions proposed by Algorithms 3–5 are different in general. Therefore, for , Algorithm 3 proposes [2, 11] (with a true coverage of 3.7%), Algorithm 4 proposes [2, 10] (with a true coverage of 6.0%), and Algorithm 3 proposes [1, 10] (with a true coverage of 4.5%).

The solutions proposed by Algorithms 3–5 are related to one another. Thus, and for any x from the studied range (2 to 500). Therefore, is the shortest from all three, and the intersection of the other two (Equation (12)).

4.3. Graphical Representations of the Confidence Intervals

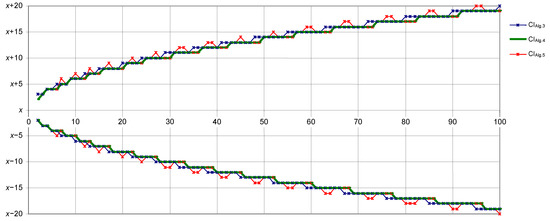

Figure 1 depicts the confidence intervals relative to the mean (x). Despite appearances, these intervals are not symmetric (see as examples (6;6) = [2, 11], (7;7) = [2, 12], and (7;7) = [3, 13] in Table 2).

Figure 1.

Poisson distribution 95% confidence intervals for .

It is visible how the upper boundary of the solutions proposed by Algorithm 3 and by Algorithm 5 jumps up and returns back to the green line expressing the solution proposed by Algorithm 4. Notably, the jumps are not simultaneous. Similarly, the lower boundary interval of the solutions proposed by Algorithm 3 and by Algorithm 5 jumps down and returns back to the green line expressing the solution proposed by Algorithm 4. Additionally, the jumps are not simultaneous with the jumps from the upper boundary and not simultaneous from one algorithm to another. It is an expected behavior, since each algorithm is seeking for boundaries providing true coverages near the imposed level.

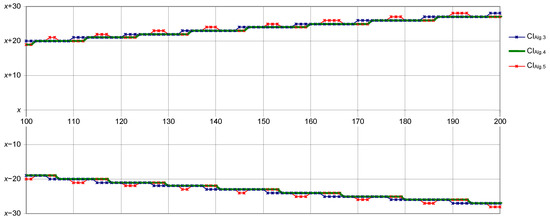

Another remark is about the tendency of the boundaries, made by irregular but monotonic steps (upper are increasing, lower are decreasing). The tendency in the range is approximated by a linear function of the square root of the Poisson parameter (for instance, for ). However, this is only a tendency observed for small x, and the dependency is slightly more complicated. For instance, for is better approximated by , with and (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Poisson distribution 95% confidence intervals for .

A good approximation for (with in the range of ) is while for (with in the range of ) is .

The obtained values of the confidence boundaries for with Algorithms 3–5 are given in Appendix A (Table A1).

The width of the 95% confidence interval is about .

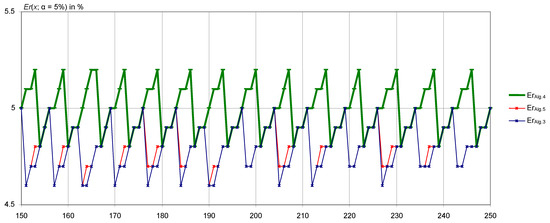

4.4. Graphical Representations of the Error Bounds

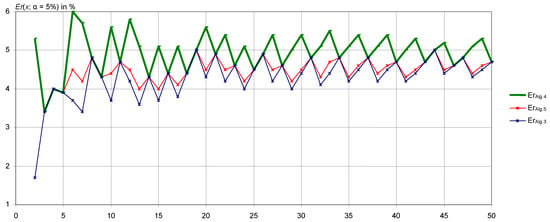

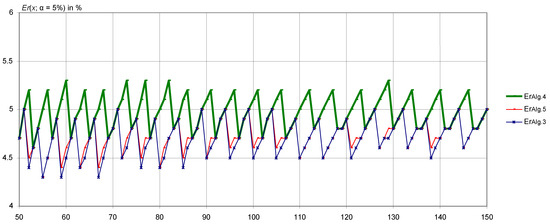

True significance levels (or errors, Er (%) = 100% − True coverage (%)) of the confidence intervals obtained with Algorithms 3–5 are depicted in the following three figures (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 3.

True coverage of 95% confidence intervals for .

Figure 4.

True coverage of 95% confidence intervals for .

Figure 5.

True coverage of 95% confidence intervals for .

The blue line () and the green line () alternate around a middle line located near the red line in a nearly symmetrical reflection. There are a few exceptions breaking the symmetry, which are visible in all three figures (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

The true significance level (and the true coverage) calculated by Algorithm 4 oscillates on both sides of the imposed level of 5% (and of the expected coverage of 95%), while the true significance level (and the true coverage) calculated by Algorithms 3 and 5 are always below the imposed level of 5% (and true coverages are above the expected coverage of 95%).

When comparing the solution proposed by Algorithm 3 with the solution proposed by Algorithm 5, the coverage of Algorithm 5 is better, closer to the imposed level at all times.

In any instance, representations of the true significance levels for larger values of the Poisson parameter (Figure 4 and especially Figure 5) show that the solutions proposed by Algorithms 3 and 5 tend (with increasing Poisson parameter x) to overlap and to mirror with the solution proposed by Algorithm 4.

There is no limit for the value of the Poisson parameter. In the case of typical statistics of the Poisson distribution, their value is calculable exactly, by knowing the parameter of the distribution, but the quality of coverage of the confidence intervals can be obtained only for the values for which Algorithms 3–5 were executed. Thus, having an image of the tendency is useful. The tendencies for the true significance levels, provided by the alternatives Algorithms 3–5 for confidence intervals, are expressed as averages and deviations in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tendencies in the true coverages (in %) for for Algorithms 3–5, expressed with averages and deviations.

The desire to always have a confidence level with at least the imposed significance is implemented in Algorithms 3 and 5, and it comes with a cost in terms of the closeness to the imposed level.

Inspecting the , , and values from Table 3, one can appreciate the solution proposed by Algorithm 3 as the poorest one. It performs the worst at all indicators and its behavior is systematic. In the same series of indicators, one can appreciate the (accelerated) tendency in for Algorithm 4 to the imposed level, as well as the fact that it performs the best at all indicators. The only disadvantage of the solution proposed by Algorithm 4 remains that it oscillates (above and below) around the imposed level, being unsuited for the applications requiring strict coverage of at least .

5. Modifications to the Poisson Distribution

5.1. Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) Distribution

ZIP [124,125,126,127,128] is a model for count data with excess zeros; it assumes with a probability that the only possible observation is 0, and the alternate event is a Poisson random variable—when manufacturing equipment is properly aligned, defects may be nearly impossible, but when it is misaligned, defects may occur, according to a Poisson distribution (Equation (13)).

5.2. Conway–Maxwell–Poisson (CMP) Distribution

CMP distribution [129] generalizes the Poisson distribution [4] by adding a parameter ( in Equation (14)) to model overdispersion and underdispersion, having Poisson distribution and geometric distribution as special cases, and the Bernoulli distribution as a limiting case [130,131,132]. Equation (14) provides the PMF for this distribution:

When , ordinary Poisson distribution results in (); when and , the distribution is geometric (); and as , the distribution is Bernoulli ().

5.3. Consul–Jain–Poisson (CJP) Distribution

CJP distribution [133] generalizes (with in Equation (15)) the Poisson distribution [4] as a limit case from generalized negative binomial distribution [134], while multivariate distributions for count data derived from the Poisson distribution are reviewed in [135]. Equation (15) provides the PMF for this distribution:

describing an event that occurs rarely in a short period, but having its occurrence for longer periods of time [136].

5.4. Pólya–Aeppli–Poisson (PAP) Distribution

PAP distribution, or geometric extension of Poisson distribution (Equation (16)), was introduced in [137] and further reported in [138] and in [139].

It is used for describing objects that come in clusters (groups of students may apply here), where the number of clusters follows a Poisson distribution and the number of objects within a cluster follows a geometric distribution, as noted in [140]. It is referred to as geometric Poisson distribution in [141,142,143,144].

5.5. Snyder–Ord–Beaumont (SOB) Distribution

When evaluations take place in a particular period, their combined size is assumed to follow a shifted Poisson distribution (Equation (17)) defined by Y = X + 1, where X follows the classical Poisson distribution (Equation (3)). This shift to the right leaves the probability of a zero to be defined by a new parameter ( in Equation (17)).

5.6. Other Modifications

Before proceeding, it is helpful to establish a skeleton for defining the PMF via CDF:

where f is the selected discrete distribution and are its parameters.

Please note that the definition of Equation (18) is valid only for discrete distributions having as the first value of their domain.

Exponentiated Poisson (EP) distribution [146,147,148] is defined by Equation (19).

with PMF from Equation (18).

EP (from Equation (19)) is a typical example from a more general case. Imagine a distribution (continuous or discrete) having a certain cumulative distribution function (CDF). Let it be . Then, with one more parameter (let be the new parameter), a new distribution can be imagined (let it be ), having the CDF be the previous one raised to an arbitrary power (): . Such a definition of a distribution is consistent in all instances except , since, at the limit of the domain: , , and thus .

Transmutated Poisson (TP) distribution [149] is defined by Equation (20).

with PMF from Equation (18).

TP (from Equation (20)) is also a typical example from a more general case. Consider the function . Using its derivatives, one can prove that is increasing from (where is 0) to (where is 1). Thus, any such construction is suited to define a distribution from any other distribution.

Another modification to the Poisson distribution is zero-modified Poisson (ZMP), with yet another limit case, zero-truncated Poisson (ZTP) [150,151,152,153,154] as in Equations (21) and (22).

A particular case of ZMP (from Equation (21)) is when , leading to the classical Poisson from Equation (3), while another particular case is , leading to zero-truncated Poisson of Equation (22).

Modified Poisson distributions arise as adaptations or extensions of the classical Poisson distribution to address limitations such as overdispersion, heterogeneity in counts, or clustering effects. To sum up, the above listed distributions extend the classical Poisson model to handle features like excess zeros, dispersion changes, or truncation, each useful in different applied contexts. Thus, ZIP (Equation (13)) models count data with more zeros than a standard Poisson would predict. By mixing a point mass at zero with a Poisson, CMP (Equation (14)) adds a dispersion parameter to handle overdispersion or underdispersion relative to Poisson, CJP (Equation (15)) introduces an extra parameter to accommodate variability and skewness, connected to queueing models, PAP (Equation (16)) mixes geometric and Poisson processes, being useful in clustering or batch arrival contexts, and SOB (Equation (17)) was designed for counting time series with autocorrelation and variable mean. EP (Equation (19)) applies an exponentiation transformation to the Poisson CDF to produce flexible tails and shapes, TP (Equation (20)) adds a skewing parameter via transmutation to adjust shape and kurtosis, ZMP (Equation (21)) alters the Poisson’s zero probability independently, allowing probability mass at zero to differ from a standard Poisson, and ZTP (Equation (22)) is a Poisson distribution conditioned to exclude zero counts, often used when zero observations are impossible or unrecorded.

In the light of the above-given generalizations, one should recognize that there are other modifications to the Poisson distribution too (such as Gamma–Poisson local level [155,156], and linear transformation of the Poisson distribution [157]), which will not be covered here.

5.7. Alternatives to the Poisson Distribution

Poisson distribution have a simple expression, depending only on one parameter, giving great parsimony [158]. This is a great advantage which does have limitations, namely the strict assumption that the mean equals the variance (equidispersion). Real-world count data may exhibit overdispersion (variance greater than the mean) or underdispersion (variance less than the mean), which the standard Poisson model cannot handle. From another point of view, even if it is not a common known fact, the Poisson distribution was originally derived as a limit of the negative binomial distribution [4,159]. Knowing this, it is no longer surprising that, in many instances, including [160,161,162,163], negative binomial distribution has been reported as a better alternative to Poisson distribution for modeling the populations of the sampled data. Other considered alternatives for certain instances were geometric distribution in [164], Gaussian distribution in [165], and Weibull and hyperexponential in [166].

5.8. Connections with Other Distributions

Poisson arrivals with the rate z imply exponentially distributed waiting times between arrivals with the same rate z and vice versa, making these distributions tightly linked in modeling random event arrivals over time, so if one records arrival times and identifies a Poisson distribution, then another will identify inter-arrival times as exponentially distributed [167,168,169]. The key property is that the inter-arrival times between consecutive arrivals in a Poisson process are independent and identically distributed exponential random variables. If the Poisson process has rate z, then each inter-arrival time follows an exponential distribution with parameter z. This means the expected time between arrivals is . Intuitively, the memoryless property of the exponential distribution aligns with the independent increments property of the Poisson process: the waiting time until the next arrival does not depend on when previous arrivals occurred.

6. Conclusions

The Poisson distribution finds extensive application across diverse fields. It is used for studying and characterizing phenomena such as Brownian motion collisions, quantum states, electromagnetic radiation scattering, radiation emission and particle decay, cosmic rays, distribution of stars in space, signal errors, manufacturing defects, and new product development. Additionally, the literature reports numerous simulations and models for a variety of processes including ship arrivals, flight delays, traffic flow, network traffic, email spam, phone calls, website traffic, GSM signals, various types of accidents, mutations in nucleic acids and cells, natural disasters, hospital arrivals and disease outbreaks, medical errors, customer service call volumes, purchasing and sales activities, store traffic, and product returns.

To determine if a data sample follows a Poisson distribution, statistical tests are recommended. Four such tests summarized here are the conditional chi-squared, likelihood ratio, Bartlett–Anscombe, and normality statistics.

For estimation, confidence intervals should be used. Due to the discrete nature of the Poisson distribution, no closed-form formula exists for confidence intervals, and algorithms must be employed for their computation. Three algorithms are presented here, of which one algorithm (Algorithm 4) achieves coverage closest to the desired level, and another (Algorithm 5) provides the closest approach for at least the prescribed coverage.

The many extensions of the Poisson distribution, such as the Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP), Conway–Maxwell–Poisson (CMP), Compound Poisson (CJP), Poisson Autoregressive Process (PAP), and others (SOB, EP, TP, ZMP, ZTP), highlight the model’s simplicity, but also its inherent limitations.

Alternatives and extensions to Poisson distribution provide more flexibility by relaxing the strict Poisson assumption of equal mean and variance, leading to better fit and more accurate modeling of count data. Poisson distribution serves as a key limiting and building-block distribution that links to the binomial, multinomial, negative binomial, gamma, and several other distributions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Level of significance (usually set to 0.05; 0.2, 0.1, 0.01, 0.005, 0.002, 0.001 also in use) | |

| CDF | Cumulative distribution function |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| True significance (as observed, when expected significance is ) | |

| PMF | Probability mass function |

| Poisson | Poisson distribution PMF |

| ZIP | Zero-inflated Poisson distribution PMF |

| CMP | Conway–Maxwell–Poisson distribution PMF |

| CJP | Consul–Jain–Poisson distribution PMF |

| PAP | Pólya–Aeppli–Poisson distribution PMF |

| SOB | Snyder–Ord–Beaumont distribution PMF |

| EP | Exponentiated Poisson distribution PMF |

| TP | Transmutated Poisson distribution PMF |

| ZMP | Zero-modified Poisson distribution PMF |

| ZTP | Zero-truncated Poisson distribution PMF |

| & | Null and alternative hypotheses |

| Conditional chi-squared statistic | |

| Likelihood ratio statistic | |

| Barlett–Anscombe statistic | |

| Normality statistic | |

| HG | Hypergeometric distribution PMF |

| Count | Count function, counting the elements in an array |

Appendix A. Raw Data for 95% CI from Algorithms 3–5

Table A1.

95% coverage confidence intervals with Algorithms 3–5.

Table A1.

95% coverage confidence intervals with Algorithms 3–5.

| Alg. 3 | Alg. 4 | Alg. 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 |

| 5 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| 6 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| 7 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 13 |

| 8 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 13 |

| 9 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 15 |

| 10 | 4 | 16 | 5 | 16 | 5 | 17 |

| 11 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 17 |

| 12 | 6 | 19 | 6 | 18 | 5 | 18 |

| 13 | 6 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 21 |

| 14 | 7 | 21 | 7 | 21 | 7 | 21 |

| 15 | 8 | 23 | 8 | 22 | 7 | 22 |

| 16 | 9 | 24 | 9 | 24 | 9 | 24 |

| 17 | 9 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 26 |

| 18 | 10 | 26 | 10 | 26 | 10 | 26 |

| 19 | 11 | 27 | 11 | 27 | 11 | 27 |

| 20 | 12 | 29 | 12 | 28 | 11 | 28 |

| 21 | 13 | 30 | 13 | 30 | 13 | 30 |

| 22 | 13 | 31 | 14 | 31 | 14 | 32 |

| 23 | 14 | 32 | 14 | 32 | 14 | 32 |

| 24 | 15 | 34 | 15 | 33 | 14 | 33 |

| 25 | 16 | 35 | 16 | 35 | 16 | 35 |

| 26 | 17 | 36 | 17 | 36 | 17 | 36 |

| 27 | 17 | 37 | 18 | 37 | 18 | 38 |

| 28 | 18 | 38 | 18 | 38 | 18 | 38 |

| 29 | 19 | 40 | 19 | 39 | 18 | 39 |

| 30 | 20 | 41 | 20 | 40 | 19 | 40 |

| 31 | 21 | 42 | 21 | 42 | 21 | 42 |

| 32 | 21 | 43 | 22 | 43 | 22 | 44 |

| 33 | 22 | 44 | 23 | 44 | 23 | 45 |

| 34 | 23 | 45 | 23 | 45 | 23 | 45 |

| 35 | 24 | 47 | 24 | 46 | 23 | 46 |

| 36 | 25 | 48 | 25 | 47 | 24 | 47 |

| 37 | 26 | 49 | 26 | 49 | 26 | 49 |

| 38 | 26 | 50 | 27 | 50 | 27 | 51 |

| 39 | 27 | 51 | 28 | 51 | 28 | 52 |

| 40 | 28 | 52 | 28 | 52 | 28 | 52 |

| 41 | 29 | 54 | 29 | 53 | 28 | 53 |

| 42 | 30 | 55 | 30 | 54 | 29 | 54 |

| 43 | 31 | 56 | 31 | 56 | 31 | 56 |

| 44 | 32 | 57 | 32 | 57 | 32 | 57 |

| 45 | 32 | 58 | 33 | 58 | 33 | 59 |

| 46 | 33 | 59 | 33 | 59 | 33 | 59 |

| 47 | 34 | 60 | 34 | 60 | 34 | 60 |

| 48 | 35 | 62 | 35 | 61 | 34 | 61 |

| 49 | 36 | 63 | 36 | 62 | 35 | 62 |

| 50 | 37 | 64 | 37 | 64 | 37 | 64 |

| 51 | 38 | 65 | 38 | 65 | 38 | 65 |

| 52 | 38 | 66 | 39 | 66 | 39 | 67 |

| 53 | 39 | 67 | 39 | 67 | 39 | 67 |

| 54 | 40 | 68 | 40 | 68 | 40 | 68 |

| 55 | 41 | 70 | 41 | 69 | 40 | 69 |

| 56 | 42 | 71 | 42 | 70 | 41 | 70 |

| 57 | 43 | 72 | 43 | 72 | 43 | 72 |

| 58 | 44 | 73 | 44 | 73 | 44 | 73 |

| 59 | 44 | 74 | 45 | 74 | 45 | 75 |

| 60 | 45 | 75 | 46 | 75 | 46 | 76 |

| 61 | 46 | 76 | 46 | 76 | 46 | 76 |

| 62 | 47 | 77 | 47 | 77 | 47 | 77 |

| 63 | 48 | 79 | 48 | 78 | 47 | 78 |

| 64 | 49 | 80 | 49 | 79 | 48 | 79 |

| 65 | 50 | 81 | 50 | 81 | 50 | 81 |

| 66 | 51 | 82 | 51 | 82 | 51 | 82 |

| 67 | 51 | 83 | 52 | 83 | 52 | 84 |

| 68 | 52 | 84 | 53 | 84 | 53 | 85 |

| 69 | 53 | 85 | 53 | 85 | 53 | 85 |

| 70 | 54 | 86 | 54 | 86 | 54 | 86 |

| 71 | 55 | 87 | 55 | 87 | 55 | 87 |

| 72 | 56 | 89 | 56 | 88 | 55 | 88 |

| 73 | 57 | 90 | 57 | 89 | 56 | 89 |

| 74 | 58 | 91 | 58 | 91 | 58 | 91 |

| 75 | 59 | 92 | 59 | 92 | 59 | 92 |

| 76 | 59 | 93 | 60 | 93 | 60 | 94 |

| 77 | 60 | 94 | 61 | 94 | 61 | 95 |

| 78 | 61 | 95 | 61 | 95 | 61 | 95 |

| 79 | 62 | 96 | 62 | 96 | 62 | 96 |

| 80 | 63 | 98 | 63 | 97 | 62 | 97 |

| 81 | 64 | 99 | 64 | 98 | 63 | 98 |

| 82 | 65 | 100 | 65 | 99 | 64 | 99 |

| 83 | 66 | 101 | 66 | 101 | 66 | 101 |

| 84 | 67 | 102 | 67 | 102 | 67 | 102 |

| 85 | 67 | 103 | 68 | 103 | 68 | 104 |

| 86 | 68 | 104 | 69 | 104 | 69 | 105 |

| 87 | 69 | 105 | 69 | 105 | 69 | 105 |

| 88 | 70 | 106 | 70 | 106 | 70 | 106 |

| 89 | 71 | 107 | 71 | 107 | 71 | 107 |

| 90 | 72 | 109 | 72 | 108 | 71 | 108 |

| 91 | 73 | 110 | 73 | 109 | 72 | 109 |

| 92 | 74 | 111 | 74 | 111 | 74 | 111 |

| 93 | 75 | 112 | 75 | 112 | 75 | 112 |

| 94 | 76 | 113 | 76 | 113 | 76 | 113 |

| 95 | 76 | 114 | 77 | 114 | 77 | 115 |

| 96 | 77 | 115 | 78 | 115 | 78 | 116 |

| 97 | 78 | 116 | 78 | 116 | 78 | 116 |

| 98 | 79 | 117 | 79 | 117 | 79 | 117 |

| 99 | 80 | 118 | 80 | 118 | 80 | 118 |

| 100 | 81 | 120 | 81 | 119 | 80 | 119 |

References

- Taylor, B. Methodus Incrementorum Directa & Inversa; Gulielmi Innys: London, UK, 1715; Available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=r-Gq9YyZYXYC (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Maclaurin, C. A Treatise of Fluxions in Two Books; Ruddimans: Edinburgh, UK, 1742; Available online: http://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_a-treatise-of-fluxions-_maclaurin-colin-profes_1742_1 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Euler, L. Methodus universalis series summandi ulterius promota. Comment. Acad. Sci. Petropolitanae 1741, 8, 147–158. Available online: http://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/euler-works/55/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Poisson, S.D. Probabilité des Jugements en Matière Criminelle et en Matière Civile, Précédées des Règles Générales du Calcul des Probabilités; Bachelier: Paris, France, 1839; Available online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k110193z (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Newcomb, S. Notes on the theory of probabilities. Math. Montly 1860, 2, 134–140. Available online: http://jhanley.biostat.mcgill.ca/bios601/Intensity-Rate/Newcomb1860.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- von Bortkiewitsch, L. Das Gesetz der Kleinen Zahlen; B.G. Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1839; Available online: http://archive.org/details/dasgesetzderklei00bortrich (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Knuth, D.E. Seminumerical Algorithms. The Art of Computer Programming, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 2. Available online: https://lccn.loc.gov/97002147 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Devroye, L. Discrete Univariate Distributions. In Non-Uniform Random Variate Generation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Chapter 10; pp. 485–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. On continuum percolation. Ann. Probab. 1985, 13, 1250–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedder, J.D. Asteroid collisions: Estimating their probabilities and velocity distributions. Icarus 1996, 123, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, A.; Velázquez, J.J.L. On the growth of a particle coalescing in a Poisson distribution of obstacles. Commun. Math. Phys. 2017, 354, 957–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alscher, A.; Hencken, K.; Trautmann, D.; Baur, G. Multiple electromagnetic electron-positron pair production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions. Phys. Rev. A 1997, 55, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero-Ruiz, M.; Manke, F.; Furno, I.; Fasoli, A.; Ricci, P. Particle transport at arbitrary timescales with Poisson-distributed collisions. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 100, 052134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielinga, B.; Milburn, G.J. Effect of dissipation and measurement on a tunneling system. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 52, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.; Birge, N.O. Dissipative quantum tunneling of a single defect in a disordered metal. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.C. Mesoscopic capacitor and zero-point energy: Poisson’s distribution for virtual charges, pressure, and decoherence control. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2014, 28, 1450181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gong, Z.; Wu, B. Quantum dynamical tunneling breaks classical conserved quantities. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 054113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.; Markus, T.; Scott, V.S.; Neumann, T. The Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar (MABEL): An airborne simulator for the ICESat-2 mission. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.A.; Brenner, A.; Hancock, D.; Robbins, J.; Gibbons, A.; Lee, J.; Harbeck, K.; Saba, J.; Luthcke, S.; Rebold, T. Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) Project: Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (ATBD) for Global Geolocated Photons; ATL03, Version 6. ICESat-2 Project; Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loredo, T.J.; Wolpert, R.L. Bayesian inference: More than Bayes’s theorem. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2024, 11, 1326926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthamoorthy, B.; Bhattacharya, D.; Sreekumar, P.; Swathi, B. Detection of Faint Sources by the UltraViolet Imaging Telescope Onboard AstroSat Using Poisson Distribution of Background. Astronom. J. 2024, 168, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Colwell, J.; Esposito, L.; Jerousek, R. Particle sizes in Saturn’s rings from UVIS stellar occultations 2. Outlier Populations in the C ring and Cassini Division. Icarus 2024, 416, 116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Sauer, K.D.; Bouman, C.A.; Melnyk, R.; Nett, B. Statistically adaptive filtering for low signal correction in x-ray computed tomography. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2021: Physics of Medical Imaging; Bosmans, H., Zhao, W., Yu, L., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 11595, pp. 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liang, Z.; Huang, W.; Gao, F.; Yuan, J.; Xu, B. Decoy-state quantum-key-distribution-based quantum private query with error tolerance bound. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 052442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruark, A.; Devol, L. The General Theory of Fluctuations in Radioactive Disintegration. Phys. Rev. 1936, 49, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, I.; Kouris, K.; Jones, M.; Spyrou, N. Theoretical and experimental investigations on the applicability of the Poisson and Ruark-Devol statistical density functions in the theory of radioactive decay and counting. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1980, 171, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Kouris, K.; Matthews, I.P.; Spyrou, N.M. Binomial vs poisson statistics in radiation studies. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1983, 212, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitek, A.; Celler, A.M. Limitations of Poisson statistics in describing radioactive decay. Phys. Medica 2015, 31, 1105–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokipii, J. Stochastic variations of cosmic rays in the solar system. Astrophys. J. 1969, 156, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, Z.; Katz, S. Ultrahigh energy cosmic rays from compact sources. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 63, 023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kitamura, T.; Ohara, S.; Konishi, T.; Tsuji, K.; Chikawa, M.; Unno, W.; Masaki, I.; Urata, K.; Kato, Y. Chaos in cosmic ray air showers. Astropart. Phys. 1997, 6, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovsky, S.; Tinyakov, P.; Tkachev, I. Statistics of clustering of ultrahigh energy cosmic rays and the number of their sources. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lavaux, G.; Jasche, J. PineTree: A generative, fast, and differentiable halo model for wide-field galaxy surveys. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 690, A236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasenko, V. Redshift evolution of primordial black hole merger rate. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 123546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos-Gines, B.; Avila, S.; Gonzalez-Perez, V.; Yepes, G. Improving and extending non-Poissonian distributions for satellite galaxies sampling in HOD: Applications to eBOSS ELGs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 530, 3458–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacki, B.C. Artificial Broadcasts as Galactic Populations. I. A Point Process Formalism for Extraterrestrial Intelligences and Their Broadcasts. Astrophys. J. 2024, 966, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Lim, J.; Kwon, J.H.; Naik, V.B.; Raghavan, N.; Pey, K.L. Backhopping-based STT-MRAM Poisson Spiking Neuron for Neuromorphic Computation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Monterey, CA, USA, 26–30 March 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skucha, K.; Gambini, S.; Liu, P.; Megens, M.; Kim, J.; Boser, B. Design considerations for CMOS-integrated Hall-effect magnetic bead detectors for biosensor applications. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 2013, 22, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihashi, C. All Error Detecting Modified Hamming Codes for Ideal Optical Channel and Application to Practical System. Acad. Rep. Fac. Eng. Tokyo Polytech. Univ. 2008, 31, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.O. Effects of manufacturing defects on the device failure rate. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2013, 42, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Bae, S.J.; Kuo, Y. Defects Driven Yield and Reliability Modeling for Semiconductor Manufacturing. In Statistical Quality Technologies: Theory and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Chapter 16; pp. 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjani, H.M.; Sørensen, J.D. Effect of Defects Distribution on Fatigue Life of Wind Turbine Components. Procedia IUTAM 2015, 13, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yli-Renko, H.; Janakiraman, R. How customer portfolio affects new product development in technology-based entrepreneurial firms. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, L.; Ren, P.; Wang, Y.; Szeto, W. From aircraft tracking data to network delay model: A data-driven approach considering en-route congestion. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 131, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.R.; Almeida, M.A.; D’Angelo, M.F.; van Woensel, T. Traffic intensity estimation in finite Markovian queueing systems. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 3018758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumlee, C.H. Optimum size seaport. J. Waterw. Harb. Div. 1966, 92, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, S.N. Berth planning by evaluation of congestion and cost. J. Waterw. Harb. Div. 1967, 93, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noritake, M.; Kimura, S. Optimum number and capacity of seaport berths. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1983, 109, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.C.; Huang, W.C.; Wu, S.C.; Cheng, P.L. A case study of inter-arrival time distributions of container ships. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2006, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Larsen, O.I. Application of queuing methodology to analyze congestion: A case study of the Manila International Container Terminal, Philippines. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2016, 4, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, A. Delays in the New York city metroplex. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2018, 114, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, C. VFDP: Visual analysis of flight delay and propagation on a geographical map. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 3510–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, A.; Sallan, J.M. Analysis of the effect of extreme weather on the US domestic air network. A delay and cancellation propagation network approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 107, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, H. A review of flight delay prediction methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Big Data Engineering and Education (BDEE), Chengdu, China, 5–7 August 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.J.; Vere-Jones, D. An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.M. Introduction to Probability Models; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Herman, R. Statistical properties of low-density traffic. Q. Appl. Math. 1962, 20, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashton, W.D. Distributions for gaps in road traffic. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1971, 7, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuoxian, W. A simple method for predicting kerbside L10 level from a free multi-type vehicular flow. Appl. Acoust. 1987, 20, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Donato, S.R.; Morri, B. A statistical model for predicting road traffic noise based on Poisson type traffic flow. Noise Control Eng. J. 2001, 49, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul-Magd, A.Y. Modeling highway-traffic headway distributions using superstatistics. Phys. Rev. E. 2007, 76, 057101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.K. Mathematical Analysis of Traffic Flow Behaviour of the internet At Ghana Technology University College. Math. Theory Model. 2018, 8, 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, V.; Floyd, S. Wide area traffic: The failure of Poisson modeling. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 1995, 3, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrey, K.; Song, L.; Hongwei, L.; Randall, P. Analyzing Network Traffic for Malicious Activity. Can. Appl. Math. Q. 2004, 12, 479–489. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.G.; Baccelli, F.; Ganti, R.K. A tractable approach to coverage and rate in cellular networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2011, 59, 3122–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cheng, H.; Long, F.; Yang, A. The statistics and analysis of packet traffic distribution characters in access network based on NetMagic platform. In Proceedings of the 2012 2nd International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNet), Yichang, China, 21–23 April 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1468–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roels, G.; Fridgeirsdottir, K. Dynamic revenue management for online display advertising. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2009, 8, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Dong, Y.; Gopalan, K. DMTP: Controlling spam through message delivery differentiation. Comput. Netw. 2007, 51, 2616–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Thomas, M.; Paxson, V.; Feamster, N.; Kreibich, C.; Grier, C.; Hollenbeck, S. Understanding the domain registration behavior of spammers. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Internet Measurement Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 23–25 October 2013; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, W.D. The Poisson Distribution: Probability Function with an Identity Crisis. Sch. Sci. Math. 1989, 89, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.R.; Baazaoui, H.; Ziou, D.; Ghezala, H.B. A predictive model for recurrent consumption behavior: An application on phone calls. Knowl. Based Syst. 2014, 64, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovich, M.; Hesse, M.; Fitzpatrick, P. Paging performance in GSM networks: Analysis and simulation. In Teletraffic Science and Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregni, S.; Cioffi, R.; Decina, M. An empirical study on time-correlation of GSM telephone traffic. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2008, 7, 3428–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Šolić, P.; Stella, M. Probabilistic modeling of harvested GSM energy and its application in extending UHF RFID tags reading range. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2013, 27, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.Q.; Yang, W.C.; Hu, Y.X. Accurate method to estimate EM radiation from a GSM base station. Prog. Electromagn. Res. M 2013, 34, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, A. Analysis of spatial distributions of accidents. Saf. Sci. 1998, 31, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, J. Non-random accident distributions and the Poisson series. In Proceedings of the Casualty Actuarial Society; Casualty Actuarial Society: Arlington County, VA, USA, 1945; Volume 32, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Seong, K.M.; Park, H.; Kim, S.J.; Ha, H.N.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J. A new method for the construction of a mutant library with a predictable occurrence rate using Poisson distribution. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 69, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, H.; Schaid, D.J.; Buettner, V.L.; Haavik, J.; Sommer, S.S. Mutational specificity: Mutation frequencies but not mutant frequencies in Big Blue® mice fit a Poisson distribution. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1996, 28, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.E.; Delbrück, M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 1943, 28, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q. Progress of a half century in the study of the Luria–Delbrück distribution. Math. Biosci. 1999, 162, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, R.E.; Bergthorsson, U.; Roth, J.R.; Ochman, H. Effect of Chromosome Location on Bacterial Mutation Rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002, 19, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Strome, E.D.; Meng, Q.; Hastings, P.J.; Plon, S.E.; Kimmel, M. A robust estimator of mutation rates. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2009, 661, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordoni, F.G.; Missiaggia, M.; Scifoni, E.; La Tessa, C. Cell survival computation via the generalized stochastic microdosimetric model (GSM2); part I: The theoretical framework. Radiat. Res. 2022, 197, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Kyoizumi, S.; Hirai, Y.; Kusunoki, Y.; Iwamoto, K.S.; Nakamura, N. Mutation frequency in human blood cells increases with age. Mutat. Res. DNAging 1995, 338, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Whitt, W. Are Call Center and Hospital Arrivals Well Modeled by Nonhomogeneous Poisson Processes? Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2014, 16, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Kanai, Y.; Misue, K. Queueing network model for obstetric patient flow in a hospital. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zeng, D.; Herring, A.H.; Ising, A.; Waller, A.; Richardson, D.; Kosorok, M.R. Detecting Disease Outbreaks Using Local Spatiotemporal Methods. Biometrics 2011, 67, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, J.; Leleu, J.P.; Preux, P.M.; Corcia, P.; Couratier, P.; Marin, B.; Boumediene, F.; Marin, B.; Couratier, P.; Preux, P.M.; et al. Residential exposure to ultra high frequency electromagnetic fields emitted by Global System for Mobile (GSM) antennas and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis incidence: A geo-epidemiological population-based study. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitt, W.; Zhang, X. A data-driven model of an emergency department. Oper. Res. Health Care 2017, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.; Naumova, E.; Tereschenko, A.; Kislitsin, V.; Ford, T. Daily variations in effluent water turbidity and diarrhoeal illness in a Russian city. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2003, 13, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumova, E.N.; MacNeill, I.B. Time-distributed effect of exposure and infectious outbreaks. Environmetrics 2009, 20, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulldorff, M.; Heffernan, R.; Hartman, J.; Assunção, R.; Mostashari, F. A Space–Time Permutation Scan Statistic for Disease Outbreak Detection. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Broman, A.T.; Priest, G.; Landrigan, C.P.; Rahman, S.A.; Lockley, S.W. The effect of blue-enriched lighting on medical error rate in a university hospital ICU. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2021, 47, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takahashi, M.; Hiro, H.; Kakinuma, M.; Tanaka, M.; Kamata, N.; Miyaoka, H. Differences in medical error risk among nurses working two-and three-shift systems at teaching hospitals: A six-month prospective study. Ind. Health 2010, 48, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Tsai, C.L.; Sullivan, A.F.; Cleary, P.D.; Gordon, J.A.; Guadagnoli, E.; Kaushal, R.; Magid, D.J.; Rao, S.R.; Blumenthal, D. Safety climate and medical errors in 62 US emergency departments. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012, 60, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, L.; Jacobs, D.G.; Meszler-Reizes, J.; Blais, M.; Fava, M.; Kessler, R.; Magruder, K.; Murphy, J.; Kopans, B.; Cukor, P.; et al. Development of a brief screening instrument: The HANDS. Psychother. Psychosom. 2000, 69, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenkopf, A.M.; Sectish, T.C.; Barger, L.K.; Sharek, P.J.; Lewin, D.; Chiang, V.W.; Edwards, S.; Wiedermann, B.L.; Landrigan, C.P. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2008, 336, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalelane, C.; Deutschländer, T. A robust estimator for the intensity of the Poisson point process of extreme weather events. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2013, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orui, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Maeda, M.; Yasumura, S. Suicide rates in evacuation areas after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Crisis 2018, 39, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, D.; Trück, S.; van den Honert, R.; Wong, W.W. Modeling risks from natural hazards with generalized additive models for location, scale and shape. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 275, 111075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Yu, P.S. A new framework for itemset generation. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth ACM SIGACT-SIGMOD-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 1–3 June 1998; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan Weinberg, L.D.B.; Stroud, J.R. Bayesian Forecasting of an Inhomogeneous Poisson Process with Applications to Call Center Data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2007, 102, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, P.S.; Hardie, B.G.; Lee, K.L. “Counting your customers” the easy way: An alternative to the Pareto/NBD model. Mark. Sci. 2005, 24, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cook, V.J., Jr.; Strong, E.C. A two-stage model of the promotional performance of pure online firms. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferguson, M.E.; Fleischmann, M.; Souza, G.C. A profit-maximizing approach to disposition decisions for product returns. Decis. Sci. 2011, 42, 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predić, B.; Radosavljević, N.; Stojčić, A. Time series analysis: Forecasting sales periods in wholesale systems. Facta Univ. Ser. Autom. Control Robot. 2020, 18, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.R.; Corsten, D.; Knox, G. From point of purchase to path to purchase: How preshopping factors drive unplanned buying. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, Q.; Talebian, M. Online versus bricks-and-mortar retailing: A comparison of price, assortment and delivery time. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 3823–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonina-Farkas, A.; Katsifou, A.; Seifert, R.W. Product assortment and space allocation strategies to attract loyal and non-loyal customers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 285, 1058–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, J.; Wu, X. Shopping trip recommendations: A novel deep learning-enhanced global planning approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 182, 114238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesmüller, G.P.; Van der Laan, E.A. An inventory model with dependent product demands and returns. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2001, 72, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, M.P.; Dekker, R. Modelling product returns in inventory control—exploring the validity of general assumptions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 81, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapp, M.; Nebel, J.; Sahamie, R. Forecasting product returns in closed-loop supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 614–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruguz, A.S.; Karabağ, O.; Tetteroo, E.; van Heijst, C.; van den Heuvel, W.; Dekker, R. Customer-to-customer returns logistics: Can it mitigate the negative impact of online returns? Omega 2024, 128, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, A.N.; Deslauriers, A.; L’Ecuyer, P. Modeling Daily Arrivals to a Telephone Call Center. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anscombe, F.J. The transformation of Poisson, binomial and negative-binomial data. Biometrika 1948, 35, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.D.; Zhao, L.H. A test for the Poisson distribution. Sankhyā: Indian J. Stat. Ser. A 2002, 64, 611–625. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, M.S. The use of transformations. Biometrics 1947, 3, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell, J.A.; Jodrá, P. The median of the Poisson distribution. Metrika 2005, 61, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.P. On the medians of gamma distributions and an equation of Ramanujan. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1994, 121, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäntschi, L. Binomial distributed data confidence interval calculation: Formulas, algorithms and examples. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D. Zero-Inflated Poisson Regression, with an Application to Defects in Manufacturing. Technometrics 1992, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.P.; Denuit, M.; Guillen, M. Number of accidents or number of claims? An approach with zero-inflated Poisson models for panel data. J. Risk Insur. 2009, 76, 821–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Holan, S.H.; Wikle, C.K.; Wildhaber, M.L. Semiparametric bivariate zero-inflated Poisson models with application to studies of abundance for multiple species. Environmetrics 2012, 23, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; Patriarca, R.; Petrella, L. Spare parts management for irregular demand items. Omega 2018, 81, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukar-Kinney, M.; Scheinbaum, A.C.; Orimoloye, L.O.; Carlson, J.R.; He, H. A model of online shopping cart abandonment: Evidence from e-tail clickstream data. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, R. A queueing model with state dependent service rate. J. Ind. Eng. 1961, 12, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Minka, T.P.; Kadane, J.B.; Borle, S.; Boatwright, P. A useful distribution for fitting discrete data: Revival of the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson distribution. J. R. Stat. Soc. C Appl. Stat. 2005, 54, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatwright, P.; Borle, S.; Kadane, J.B.; Minka, T.P.; Shmueli, G. Conjugate analysis of the Conway-Maxwell-Poisson distribution. Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, D.; Guikema, S.D.; Geedipally, S.R. Application of the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson generalized linear model for analyzing motor vehicle crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.C.; Jain, G.C. A generalization of the Poisson distribution. Technometrics 1973, 15, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Consul, P. A generalized negative binomial distribution. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1971, 21, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, D.I.; Yang, E.; Allen, G.I.; Ravikumar, P. A review of multivariate distributions for count data derived from the Poisson distribution. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2017, 9, e1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuenter, H.J.H. On the generalized Poisson distribution. Stat. Neerl. 2000, 54, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeppli, A. Zur Theorie Verketteter Wahrscheinlichkeiten: Markoffsche Ketten höherer Ordnung. Ph.D. Thesis (Supervisors: G. Pólya and H. Weyl), ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pólya, G. Eine wahrscheinlichkeitsaufgabe in der kundenwerbung. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1930, 10, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pólya, G. Sur quelques points de la théorie des probabilités. Ann. Inst. Henri Poincare 1930, 1, 117–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, G.; Epifanio, I.; Simó, A.; Zapater, V. Clustering of spatial point patterns. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2006, 50, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, L.L.; Huang, D.W. Ising fluctuations for the intermittent and scaling behaviors of high energy multiparticle productions. Phys. Lett. B 1992, 283, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, L.L.; Huang, D.W. Salient features of high-energy multiparticle distributions learned from exact solutions of the one-dimensional Ising model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W. On multiplicity distributions. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 11, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Wilk, G.; Włodarczyk, Z. Geometric Poisson distribution of photons produced in the ultrarelativistic hadronic collisions. Eur. Phys. J. A 2023, 59, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.D.; Ord, J.K.; Beaumont, A. Forecasting the intermittent demand for slow-moving inventories: A modelling approach. Int. J. Forecast. 2012, 28, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuş, C. A new lifetime distribution. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 4497–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R. Discrete competing risk model with application to modeling bus-motor failure data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2010, 95, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, F.; Luiz Ramos, P.; Henrique Ferreira, P. Exponential-Poisson distribution: Estimation and applications to rainfall and aircraft data with zero occurrence. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2020, 49, 1024–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.T.; Buckley, I.R. The alchemy of probability distributions: Beyond Gram-Charlier expansions, and a skew-kurtotic-normal distribution from a rank transmutation map. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0901.0434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.C.; Gross, A.J. Estimating the zero class from a truncated Poisson sample. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1973, 68, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, E.; Böhning, D. On estimation of the Poisson parameter in zero-modified Poisson models. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2000, 34, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data; Number 53 in Econometric Society Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, K.S.; Andrade, M.G.; Louzada, F. On the zero-modified Poisson model: Bayesian analysis and posterior divergence measure. Comput. Stat. 2014, 29, 959–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirche, C.F.; Bijmolt, T.H.; Gijsenberg, M.J. When offline stores reduce online returns. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.C.; Fernandes, C. Time series models for count or qualitative observations. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1989, 7, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, P.M. Bayesian forecasting for low-count time series using state-space models: An empirical evaluation for inventory management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 118, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, H.; Yang, H. A modified poisson distribution for smartphone background traffic in cellular networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloboff, P.A. Parsimony, likelihood, and simplicity. Cladistics 2003, 19, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Kutschera, M. On the origin of negative binomial multiplicity distributions in proton-nucleus collisions. Phys. Lett. B 1989, 220, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]