Abstract

To investigate the influence mechanism of hanger damage and arch-beam combined parameters on the failure behavior of tied-arch bridges, this study employs an advanced damage failure model within the LS-DYNA. A comprehensive simulation of the entire failure process was conducted, considering the coupled effects of hanger damage parameters and structural parameters of the arch-beam system, using a tied-arch bridge as the engineering case. The primary innovation of this study lies in overcoming the limitations of previous research, which has largely been confined to single hanger failure or static parameter analysis, by achieving, for the first time, dynamic tracking and quantitative identification of structural failure paths under the coupled influence of multiple parameters. The results demonstrate that both the severity and spatial distribution pattern of hanger damage significantly influence the structural failure mechanism. When damage is either uniformly distributed across the bridge or relatively concentrated—particularly when long hangers experience severe degradation—the structure becomes susceptible to cascading stress redistribution, substantially increasing the risk of global progressive collapse. This finding provides a theoretical foundation for developing risk-informed maintenance and repair strategies for hangers. It is therefore recommended that practical maintenance efforts prioritize monitoring the condition of long hangers and regions with concentrated damage. Furthermore, variations in arch-beam combined parameters are shown to have a significant effect on the structure’s collapse resistance. For the case bridge studied herein, the original design parameters achieve an optimal balance between anti-collapse performance and economic efficiency, underscoring the importance of rational parameter selection in enhancing system robustness. This work offers both theoretical insights and numerical tools for evaluating and optimizing the collapse-resistant performance of under-deck tied-arch bridges, contributing meaningful engineering value toward improving the safety and durability of similar structures.

1. Introduction

The tied-arch bridge, characterized by its esthetically pleasing form and efficient load transfer mechanism, has been extensively adopted in modern urban transportation systems [1,2,3,4,5]. As a critical load-transmitting component connecting the arch ribs to the bridge deck system, the reliability of hangers plays a decisive role in ensuring the overall safety and durability of the bridge structure. Nevertheless, in recent years, frequent bridge collapse incidents caused by hanger damage have raised serious concerns [6,7], such as the collapses of the Nanfangao Bridge and the Shaoxing Bridge, which highlight the vulnerability of this bridge type to progressive failure under hanger chain rupture [8,9]. Existing studies have shown that while the failure of a single or localized hanger may not immediately result in total collapse, cumulative damage and parameter coupling can induce internal force redistribution, leading to overloading of adjacent hangers. This may initiate a cascading failure process and ultimately result in systemic collapse [10].

Most existing studies on hanger failure have primarily focused on the static and dynamic responses induced by single cable breakage. For example, Ben et al. [11] simulated the dynamic fracture process by removing the failed hanger and applying equivalent nodal forces. They observed that cable breakage can induce oscillatory responses in adjacent struts, with greater tension loss and structural impact occurring when the breakage location is farther from the bridge centerline. Wang et al. [12] compared the structural responses under sequential and simultaneous cable breakage scenarios, concluding that middle-span cable failure exerts the most significant influence, and that the two loading cases yield generally similar responses. They also noted that suspension bridges can maintain overall stability after the failure of one or multiple cables, although local stress concentrations require careful attention. Chen et al. [13] proposed a three-dimensional damage index to assess continuous cable breakage in cable-stayed bridges. Their results indicated that dynamic responses under sequential breakage are less severe than those under simultaneous breakage, and that bridge deck displacements remain within acceptable limits. Yu et al. [14] conducted scaled model tests and found that the rupture of short hangers near the arch foot has the most pronounced effect on internal force redistribution. Wu et al. [15] reported that the failure of a single hanger may initiate a “domino effect,” while the consecutive failure of multiple cables can lead to main arch instability or even bridge deck collapse.

Regarding failure mechanisms, Zhang Jiquan et al. [16] investigated the effects of key parameters such as the rise-to-span ratio and cross-bracing configuration on structural stability, and concluded that the non-conservative force characteristics of stay cables can effectively delay the onset of instability. Xu et al. [17] introduced the concept of the “node buckling mechanism” in suspension domes, demonstrating that the likelihood of node buckling fundamentally determines the risk of global collapse. Fan et al. [18] enhanced the technical condition assessment methodology for half-through and deck-level arch bridges by incorporating robustness evaluation indicators. Qiu et al. [19,20] developed a cable-breakage model for suspension bridges that accounts for local vibrations of the main cable, highlighting that such vibrations significantly affect the accuracy of structural calculations.

In summary, existing studies have clearly established that the progressive failure of hangers is closely tied to the overall structural system. However, systematic investigations into the coupling between the dynamic evolution of damage and the combined arch-beam parameters remain limited, particularly regarding the evolutionary patterns of failure paths, which hinders the advancement of design strategies against progressive collapse. This study focuses on a typical tied-arch bridge, for which a three-dimensional finite element model is developed and validated. The research emphasizes the coupled influence of hanger damage severity and variations in arch-beam parameters on failure paths and failure mechanisms, aiming to address this knowledge gap and provide a scientific basis for the operational management and maintenance of such bridge structures.

2. Structural Characteristics and Hanger Failure Analysis Methodology for Through Tied-Arch Bridges

2.1. Structural Design and Configuration of Background Engineering Bridge

A representative standard span of a deck-stiffened tied-arch bridge was selected for analysis. The span length is 100 m, with a calculated span of 95.5 m. The center-to-center distance between the two arch ribs is 22.37 m, the rise-to-span ratio is 1/4.5, and the arch axis is defined by a catenary coefficient of 1.347. The arch ribs feature dumbbell-shaped cross-sections, internally filled with C50 concrete, and are laterally braced by a single central I-shaped cross-brace and K-shaped cross-braces on both sides. The bridge deck system consists of Π-shaped precast slabs. Twelve pairs of hangers, spaced at intervals of 7.1 m, are arranged along the span, each composed of 91 galvanized high-strength steel wires with a diameter of Φ7 mm (designated D1 to D12). The actual structural configuration of the bridge is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The actual situation of a through tied-arch bridge.

2.2. Development of Finite Element Model

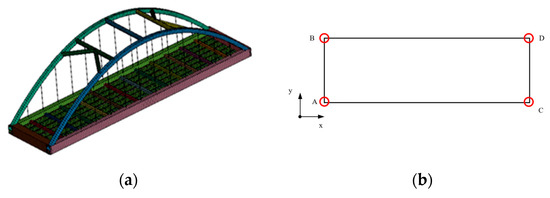

During the finite element modeling process, to accurately simulate the actual mechanical behavior of the hangers, three rotational degrees of freedom were coupled at both the upper and lower connection nodes of each hanger, while all translational degrees of freedom were released, to reflect the hinged connection characteristics of the hangers in the model. For the numerical simulation, beam elements were used to model the arch ribs, cross beams, longitudinal beams, and cross bracing, as these components exhibit primarily bending and axial deformation characteristics. The tie bars and hangers were also modeled using beam elements to capture their tensile behavior. The bridge deck was simulated using shell elements, which are appropriate for capturing its thin-plate structural behavior. The mesh sizes for various components should not differ excessively. Specifically, for main load-bearing components such as the arch rib, hangers, and deck system, considering the high stress gradients that may occur during hanger fracture, the element size was controlled within the range of 10–20 cm. For other secondary components, the same element type was used, but the mesh size was appropriately coarsened to 30–50 cm. Additionally, the “virtual topology” function was utilized to merge small geometric surfaces and reduce redundant elements.

The hanger fracture time was determined based on the fundamental frequency of the bridge structure, satisfying t ≤ 0.01T (where T is the fundamental period of the structure). For the simulation of the arch rib, the pre-camber of the through tied-arch bridge was preliminarily calculated before modeling to offset the vertical displacement caused by gravity. The pre-camber value was determined by Equation (1), where represents the total deflection and K is the adjustment factor.

According to the “General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts”, the adjustment factor generally ranges between 1.0 and 1.2. In the finite element model, the pre-camber was achieved by adjusting the geometry of the tie beam and hangers.

The boundary conditions of the arch rib were set based on the actual bearing arrangement: End A is a fixed bearing; End B is a unidirectional sliding bearing constrained in the x-direction; End C is a unidirectional sliding bearing constrained in the y-direction; and End D is a custom bidirectional sliding bearing. A schematic diagram of the established finite element model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Finite element model of a through tied-arch bridge: (a) Finite element model and (b) Boundary condition diagram.

2.3. Finite Element Simulation Methodology for Analyzing Dynamic Responses Induced by Hanger Failure

Structural failure criteria serve as the fundamental basis for evaluating whether a structure or its components transition from a normal operational state to a condition in which they no longer fulfill their intended functions—such as load-bearing capacity, stability, and serviceability—under the influence of applied loads, environmental conditions, and other external factors. These criteria essentially establish the failure threshold by quantitatively relating structural responses (stress, strain, displacement, and energy dissipation) to the ultimate capacity of the constituent materials or the structural system as a whole.

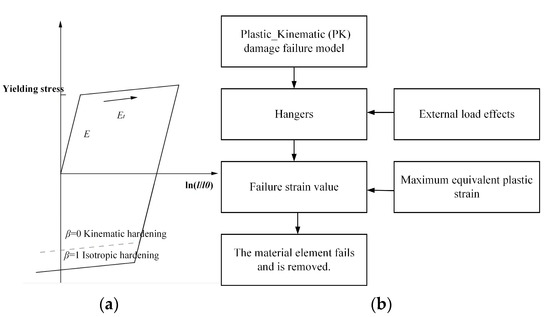

The Plastic_Kinematic material damage failure model is employed to simulate the rupture of the hangers. In this model, material failure is governed by the maximum equivalent plastic strain. Once the equivalent plastic strain reaches the predefined failure strain threshold, the corresponding material element is deemed failed and removed from the simulation, thereby capturing the progressive failure behavior of the material. The Plastic_Kinematic (PK) damage failure model is a strain rate-dependent elastoplastic constitutive model that incorporates failure criteria. The stress–strain relationship is represented by two linear segments: the first segment has a slope equal to the material’s elastic modulus, while the second segment has a slope corresponding to the tangent modulus. This model can describe different hardening behaviors depending on the value of the parameter β, as illustrated in Figure 3. Specifically, it represents isotropic hardening (β = 1), kinematic hardening (β = 0), or a combination of both (mixed hardening) when 0 < β < 1. The strain rate effect is modeled using the Cowper–Symonds formulation, which accounts for the viscoplastic response of the material. It is recommended to activate the viscoplastic strain rate effect by setting the parameter VP to 1. The mathematical formulation of the PK damage failure model is given in Equations (2) and (3).

Figure 3.

PK damage failure model: (a) Principles of the Damage and Failure Model and (b) Explanation of the Failure Process in the Damage and Failure Model.

The material behavior of the high-strength strands was modeled using the plastic kinematic model. The key parameters were assigned as follows: a yield stress of 1860 MPa, a tangent modulus of 2.0 GPa to define post-yield stiffness, and a hardening parameter of β = 1 for pure isotropic hardening. Strain rate sensitivity was considered using the Cowper-Symonds model with coefficients C = 40.0 s−1 and p = 5.0. Material failure was triggered at a plastic strain of 0.04.

Herein, σy denotes the yield strength, whereas σ0 refers to the initial yield strength. The plastic hardening modulus is represented by Ep, and its computational expression is provided in Equation (3). The effective plastic strain is defined as ε(eff,p), the elastic modulus is denoted by E, and the tangent modulus is indicated by Et. The parameters l0 and l correspond to the initial and final lengths of the specimen after a single-cycle tensile test, respectively. Furthermore, p and C are strain rate-dependent parameters.

2.4. Constitutive Modeling of Bridge Collapse and Structural Failure

The investigation into the damage and failure mechanisms of bridges, including their failure processes and propagation paths, was conducted using LS-DYNA. Constitutive models for reinforced concrete materials (MAT_CONCRETE_EC2, MAT_BRITTLE_DAMAGE, MAT_RC_BEAM), steel materials (MAT_PLASTIC_KINEMATIC), and discrete beam elements (MAT_CABLE_DISCRETE_BEAM) were implemented. To simulate the progressive collapse behavior, damage material models *MAT_172, *MAT_174, *MAT_003, *MAT_071, and *MAT_096 were applied. The damage and failure mechanism is characterized by establishing initiation criteria and damage evolution laws for different failure modes, which enables the description of material stiffness degradation under loading. Once the accumulated damage reaches a critical threshold, the material loses its load-bearing capacity and ultimately fails. Since LS-DYNA does not support anisotropic cross-sections, the corresponding cross-sections are converted into equivalent-area sections. The parameters of all structural components are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of each component of the model.

3. Verification of Finite Element Model and Simulation Method

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Load Test Results and Field Bridge Inspection Data

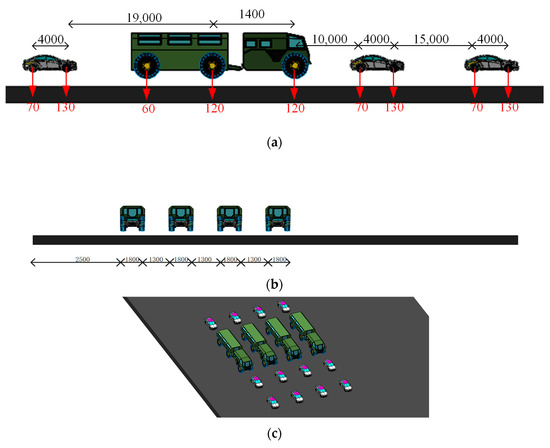

Based on the load test report, the test loading cases were classified into two categories: one involving only the dead load, and the other involving a combination of dead load and live load. According to the General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts (BG-2015-Q2-TS 0507) [21], the most unfavorable vehicle load configuration on the bridge was determined. The corresponding loading case is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the most unfavorable position (Dimension units: mm, Load units: kN): (a) Schematic diagram of the longitudinally critical position arrangement of vehicular loads; (b) Schematic diagram of the transversely critical position arrangement of vehicular loads; and (c) Schematic diagram of the transversely critical position arrangement of vehicular loads.

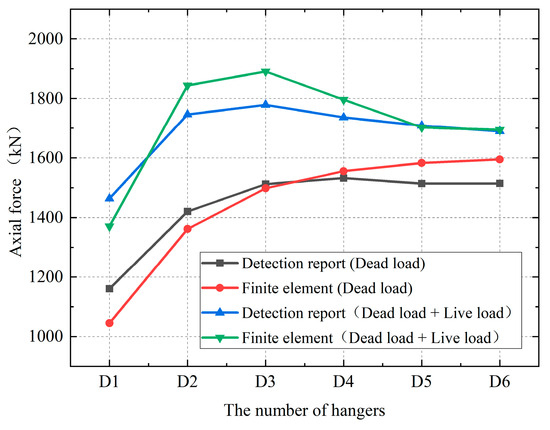

As shown in Figure 5, under both loading conditions, the maximum discrepancy between the finite element results and the inspection report was 6.3%. Furthermore, the stress distribution patterns of the hanger remained consistent under both conditions. Therefore, the established finite element model was validated as reasonable and can be reliably applied to subsequent research calculations.

Figure 5.

Comparison of axial force under two working conditions.

3.2. Experimental Validation of Finite Element Simulation Approach for Analyzing the Dynamic Effect of Hanger Fracture

The hanger-breaking simulation method employed the PK damage failure model presented in Section 2.3, which is specifically designed to simulate the sudden failure of hangers under emergency conditions. To validate the accuracy of this simulation approach, a comparative analysis was conducted based on an actual hanger-breaking test.

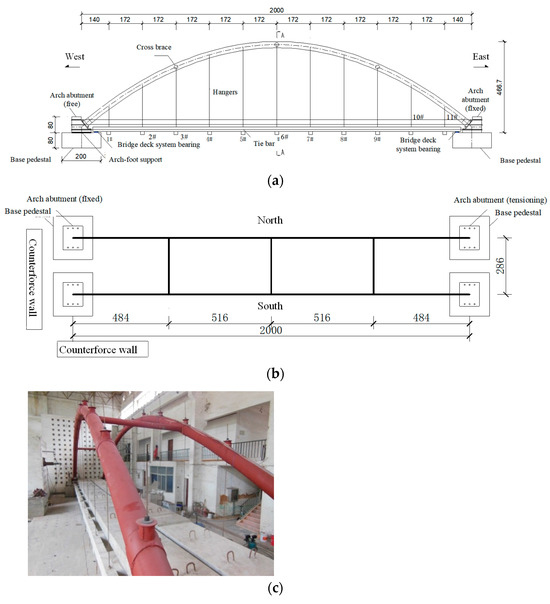

The experimental model was developed based on a prototype of a lower-deck rigid-frame tied-arch bridge, with the overall configuration illustrated in Figure 6. To facilitate model fabrication and experimental implementation, bridge piers were omitted from the design. As a result, the structural system was simplified to a simply supported tied-arch, comprising key components such as main arch abutments, end cross beams, the bridge deck system, hangers, and tie bars. The scaling of prestress levels followed similarity theory, ensuring that the prestressing forces in the prototype were proportionally converted according to the geometric scale ratio to determine the appropriate tensioning control stresses for the model’s prestressed tendons. Considering spatial constraints and loading capacity at the testing facility, the model was designed with a maximum length of 20 m and width of 3 m. This experiment establishes a scaled model based on stiffness similarity theory. Given the relatively small scale ratio of 1:6.4, the strain rate discrepancy between the model and the prototype becomes negligible after stiffness similarity matching. Consequently, the constitutive parameters of the model material at the “corresponding strain rate” can be directly adopted without requiring further correction. To simulate self-weight loading on the superstructure, the suspended bridge deck system was designed by applying similarity principles to the target hanger forces. Specifically, the longitudinal girders of the bridge deck are supported at both ends on abutments and suspended at midspan via hangers connected to the underside of the main arch. Importantly, the bridge deck system operates independently of the tie hangers. The model parameters of each component are presented in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Diagram of test model (units: mm): (a) General layout drawing; (b) Floor plan; and (c) On-site loading conditions.

Table 2.

Parameters of the test model.

Prior to initiating the test, the horizontal alignment of the bridge deck system serves as a practical indicator for assessing the compatibility between tie forces and hanger forces. A level bridge deck generally indicates a balanced force distribution among the ties and hangers, suggesting that the initial force equilibrium aligns with the intended experimental setup.

In the experiment, a total of 11 pairs of hangers were installed. This study examined the dynamic responses under six different conditions involving the failure of a pair of hangers, focusing on their effects on the displacement and stress of the arch rib and bridge deck system, as well as the axial forces in adjacent hangers. The overall configuration of the experimental model is illustrated in Figure 6a,b. To enhance the observable dynamic response during hanger failure, counterweight blocks were evenly distributed across each cross beam structure during the experiment. The specific loading positions of these counterweight blocks are shown in Figure 6c. The process of hanger fracture was initiated using a dedicated hanger-breaking trigger device.

To simulate hanger rupture during the experiment, a specialized hanger-breaking trigger device was employed. This mechanism operates on electromagnetic actuation and lever amplification principles, consisting primarily of an electromagnet-equipped clamp and two wedge-shaped steel connectors. By controlling the energization and de-energization of the electromagnet, the device enables secure connection followed by instantaneous release, thereby realistically simulating sudden hanger failure; the detailed configuration is depicted in the referenced Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The test device of hanger breaking: (a) Fixture construction and (b) Wedge-shaped connecting block.

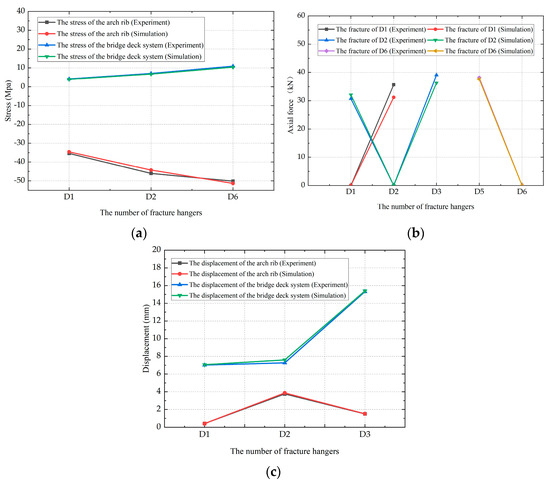

Herein, six failure conditions were established. To validate the reliability of the hanger simulation method, three representative failure conditions were selected for comparative analysis: the short hangers D1 and d1, the moderately short hangers D2 and d2, and the long hangers D6 and d6. The comparison between the experimental results and finite element simulations is illustrated in Figure 8. The comparison of maximum response values and the corresponding deviation are summarized in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the maximum deviation between the experimental model and the finite element simulation remains within 12.5%, indicating a relatively low error. Therefore, the PK damage failure model used to simulate the hanger-breaking effect is consistent with actual structural behavior, and is suitable for the subsequent analysis of hanger failure. Comprehensive experimental data regarding the axial force in the hangers are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 8.

Comparison of test results and finite element results under three working conditions: (a) Maximum displacement at the damaged hanger position; (b) The maximum axial force of adjacent hangers; and (c) Maximum stress value.

Table 3.

Comparison between test and finite element model.

4. Analysis of Key Influencing Parameters on the Failure Mechanism

4.1. Influence of Hanger Damage Degree and Spatial Distribution on the Failure Mechanism

Upon the commissioning of a bridge, damage initiation in hangers becomes inevitable. The extent of hanger damage, however, exhibits a stochastic nature and is challenging to predict with high accuracy. This damage can be characterized by two key aspects: the reduction in load-bearing capacity of individual hangers and the spatial distribution of damaged hangers across the entire bridge structure. Accordingly, this study focuses on investigating the overall damage patterns of hangers within the entire bridge system. For through tied-arch bridges, the failure of one pair of hangers typically does not lead to structural collapse. However, if the remaining hangers experience varying degrees of damage that reduce their load-bearing capacity, the entire bridge may become susceptible to collapse. When the corroded area of a hanger exceeds 50% of its surface area, and the corrosion thickness significantly alters the cross-sectional dimensions and mechanical properties of the hanger, or when the measured force deviates from the designed value by more than 20%, indicating that the overall mechanical performance of the bridge structure is affected by the hanger [22]. Based on these criteria, the linear damage states of the hangers were classified into three distinct conditions, as summarized in Table 4. As indicated in Reference [23], long hangers play the most critical role in structural performance. Therefore, this study initiated the analysis with the initial rupture of two pairs of long hangers (D6, D’6, d6, d’6), aiming to investigate the bridge’s failure paths under various damage patterns of the remaining hangers. The subsequent analysis was conducted under the full-bridge dead load condition. The ultimate bearing capacity of the stay cables in the bridge design phase was specified as f = 5848.57 kN. The hangers damage pattern is illustrated in Figure 9, where the damage gradient was symmetrically applied to both sides of the arch ribs.

Table 4.

Hangers damage conditions.

Figure 9.

The damage degree of hangers.

Current domestic standards for assessing corrosion damage primarily adopt the limit state principle, focusing on the reduction in effective cross-sectional area and stress concentration effects induced by corrosion. Once cracks initiate on the material surface, their subsequent propagation is governed by the interplay between the material’s fracture toughness and the prevailing stress conditions. Taking bridge wire rope structures as an example, the corrosion-induced broken wire rate serves as a critical indicator of mechanical performance degradation. Existing studies have demonstrated that when the broken wire rate reaches 10%, it enters a phase of rapid increase, leading to a sharp decline in the structure’s resistance to fatigue loading. In practical engineering contexts, bridge hangers are continuously exposed to atmospheric environments and subject to fluctuating environmental conditions, resulting in considerable variability in damage progression. To address this, the three distinct gradient damage scenarios proposed in this study are designed to encompass representative damage evolution patterns in hangers, enabling a qualitative analysis of their damage severity and developmental characteristics. It should be emphasized that the present analysis assumes idealized conditions, with the primary objective of elucidating the failure mechanisms underlying the observed damage gradients. This research approach aligns with the methodology of China’s “Bridge Technical Condition Evaluation Standard,” which also centers on qualitative grading for assessing structural damage, categorizing technical conditions through defined levels. In this study, the assumption of 80% damage as the critical threshold is grounded in the ultimate limit state of hangers under damaged working conditions. Using this threshold as a boundary point to establish a five-level damage evaluation system not only reflects the actual mechanical behavior of hanger structures but also remains consistent with the evaluation framework specified in the standard, thereby ensuring the practical engineering applicability of the research findings.

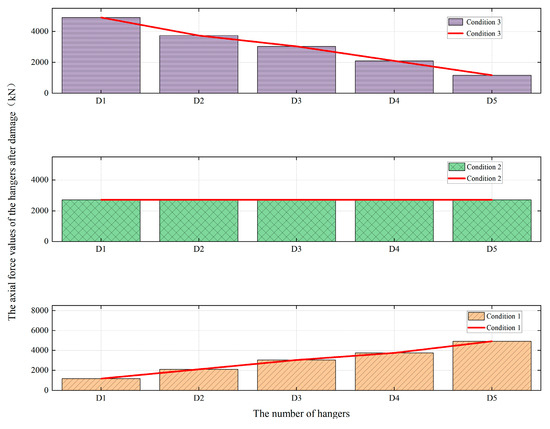

Under the coupled action of atmospheric environmental corrosion and repeated loading, the damage distribution along the hangers of the bridge exhibits significant randomness. To investigate this randomness, three representative loading conditions were considered. In the second condition, all hangers were assumed to be uniformly damaged up to a critical level. This represents the most common case, as all hangers are generally subjected to the same operational, management, and maintenance conditions. In the first condition, the damage distribution followed an opposite gradient, progressively increasing from the long hangers toward the short ones near the bridge piers (with the long hangers being the most severely damaged). In the third condition, an extreme gradient distribution of damage was considered, where the degree of damage gradually increased from the short hangers to the longer ones in the mid-span region (with the short hangers experiencing the most severe damage). When the actual damage distribution lies between these two extreme gradient conditions (first and third), the characteristics of a uniform unidirectional gradient damage distribution are examined.

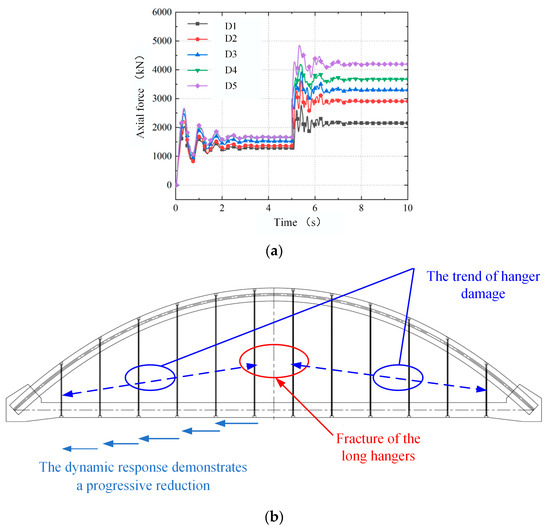

Based on the aforementioned test data, it is evident that following the rupture of the long hangers (D6, D′6, d6, d′6), the remaining hangers experience internal force redistribution. The peak axial force of hanger D5 under dynamic loading is 4849.03 kN. The maximum axial forces of hangers D4, D3, D2, and D1 are 4189.03 kN, 3925.29 kN, 3624.76 kN, and 2775.37 kN, respectively. The dynamic time-history curves and the corresponding force transmission patterns are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Load path: (a) D(d)6, D(d)’6 fracture, the axial force of remaining hangers and (b) Response path.

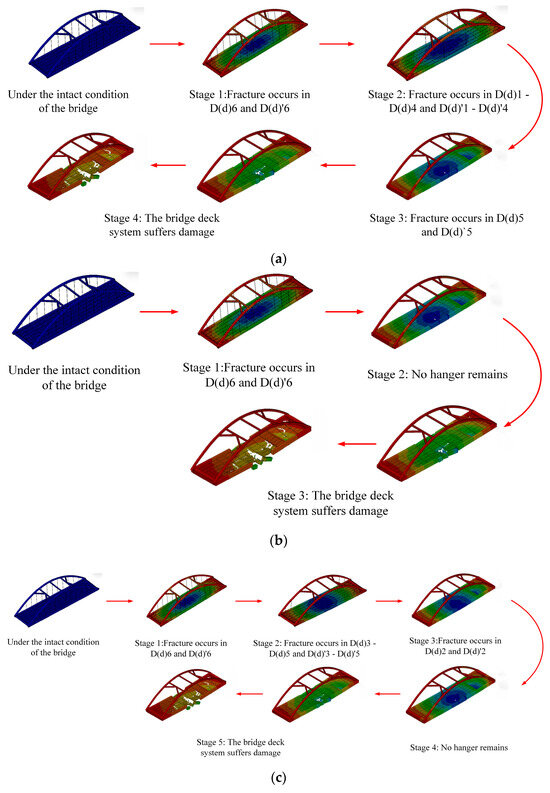

Therefore, under Working Condition 1, the failure path of the overall bridge collapse can be categorized into four distinct stages:

Stage 1: The long hangers D(d)6 and D(d)′6 undergo sudden failure; Stage 2: The hangers D(d)1~D(d)4 and D(d)′1~D(d)′4 exceed their ultimate load-bearing capacities and subsequently rupture; Stage 3: The hangers D(d)5 and D(d)′5 rupture, leading to the failure of all remaining hangers across the bridge; Stage 4: The displacement of the bridge deck system surpasses its critical threshold, initiating structural damage. The failure path is illustrated in Figure 11a.

Figure 11.

Failure path: (a) Condition 1; (b) Condition 2; and (c) Condition 3.

Under Working Condition 2, the failure path of the bridge’s complete collapse can be categorized into three distinct phases:

Stage 1: The long hangers D(d)6 and D(d)′6 undergo sudden failure; Stage 2: All hangers across the bridge rupture; Stage 3: The displacement of the bridge deck system surpasses its critical threshold, initiating structural damage. The failure path is illustrated in Figure 11b.

Under Working Condition 3, the failure path of the bridge’s complete collapse can be divided into five distinct stages:

Stage 1: The long hangers D(d)6 and D(d)′6 undergo sudden failure; Stage 2: The hangers D(d)3–D(d)5 and D(d)′3–D(d)′5 rupture sequentially; Stage 3: The hangers D(d)2 and D(d)′2 experience rupture; Stage 4: The hangers D(d)1 and D(d)′1 undergo rupture; Stage 5: The displacement of the bridge deck system surpasses its critical threshold, initiating structural damage. The failure path is illustrated in Figure 11c.

Consequently, under Working Condition 3, the bridge exhibits the longest failure path. Conversely, under Working Condition 2, the failure path is the shortest, which indicates that the bridge structure is most vulnerable to collapse under this condition. This suggests that during inspections, if damage to the hangers is detected and all hangers across the bridge exhibit the same (or similar) level of severe damage, such a condition should be assigned the highest priority in maintenance and repair decision-making, necessitating the immediate implementation of intervention measures. When variations exist in the degree of hanger damage across the bridge, a situation involving severe damage to the long hangers is more critical compared to one involving severe damage to the short hangers. In such cases, it becomes even more essential to prioritize the scheduling of maintenance and repair actions accordingly.

4.2. Influence of Arch-Beam Combined Parameters on the Failure Mechanism

The arch-beam composite structure can be classified into three distinct structural configurations based on the stiffness ratio between the arch ribs and the main girders: the rigid-girder-flexible-arch type, the flexible-girder-rigid-arch type, and the rigid-girder-rigid-arch type. Modifying the stiffness ratio between the arch and the girder leads to transformations in the structural configuration of the bridge, as summarized in Table 5. Furthermore, variations in the arch-girder composite parameters can significantly alter the failure mechanism of the overall bridge structure.

Table 5.

The influence of arch-beam combination parameters on bridge structure.

Given that the through tied-arch bridge features a dumbbell-shaped arch rib structure, the “Technical Specifications for Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Arch Bridges” recommend using Equation (4) to calculate the equivalent cross-sectional stiffness when converting variable cross-sections. Specifically, Es denotes the elastic modulus of steel, Is represents the moment of inertia of the steel cross-section, Ec stands for the elastic modulus of concrete, and Ic refers to the moment of inertia of the concrete cross-section.

Following the cross-sectional conversion of the arch rib, the bridge stiffness ratio relative to its design value was defined as K0. While maintaining constant cross-sectional areas of both the arch and the beam, the stiffness of the arch rib was preserved. The stiffness of the bridge deck system was then adjusted to 50%, 75%, 150%, and 200% of the original design value, corresponding to 0.5K0, 0.75K0, 1.5K0, and 2K0, respectively. This study investigates how variations in the arch-beam stiffness ratio influence the failure mechanism of the through-type tied-arch bridge under a complete hanger fracture condition. To further explore this relationship, different arch-beam stiffness ratios were selected under the assumption that all hangers were initially intact. A controlled failure of four pairs of hangers was introduced, thereby triggering a progressive failure of the remaining hanger system. The resulting displacement, stress, and strain time-history curves at the point of structural failure were employed as key comparative indicators to systematically analyze the failure behavior of the bridge.

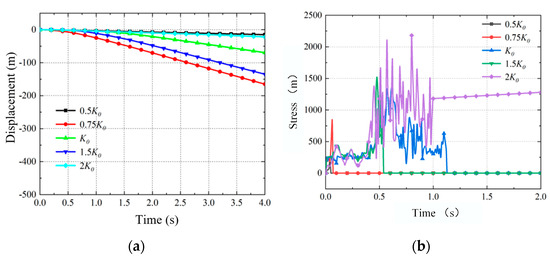

The bridge deck slab at the mid-span (i.e., 1/2 position) of the structure is selected as the object of investigation. As shown in Figure 12a, when the arch-beam combined parameter is 0.5K0, the downward deflection displacement of the bridge deck system at this location exhibits minimal variation over time. The 2K0 case follows a similar trend, with a slower bridge deck drop speed compared to the original structure. In contrast, when the arch-beam combined parameters are set to 1.5K0 and 0.75K0, the displacement increases more significantly with time, and the rate of change is notably faster than that observed under the original structural parameters.

Figure 12.

Dynamic time history curve: (a) Displacement and (b) Stress.

As illustrated in Figure 12b, the stress value dropping to 0 MPa indicates that the bridge deck at this specific location has experienced structural damage and subsequent detachment. When the arch-beam combined parameter is 0.5K0, the bridge deck at the mid-span (1/2 position) experiences the lowest stress level. Damage initiates at this location after the stress reaches 49.5 MPa at 0.03 s. For the case with the arch-beam combined parameter set to 0.75K0, structural failure occurs when the stress attains 843 MPa at 0.06 s. When the arch-beam combined parameter is 1.5K0, damage initiation begins after the stress reaches 1470 MPa at 0.48 s. In the case of 2K0, the bridge deck at the mid-span remains structurally intact within the observed time frame.

Based on the observed variations in displacement and stress at the mid-span (1/2 position), as summarized in Table 6, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted to assess the influence of arch-beam combined parameters on the mechanical behavior of the bridge deck. The results indicate that when the arch-beam combined parameter is set to 2K0, the bridge deck system demonstrates superior anti-collapse performance compared to other parameter configurations. In practical engineering design and construction, setting the arch-beam combined parameter to K0 not only satisfies the required load-bearing capacity but also achieves better anti-collapse performance than the 1.5K0 configuration. Furthermore, this choice leads to a reduction in overall construction costs. These findings collectively suggest that increasing the arch-beam combined parameter does not inherently guarantee improved anti-collapse performance of the bridge deck system.

Table 6.

The influence of arch-beam combination parameters on failure mechanism.

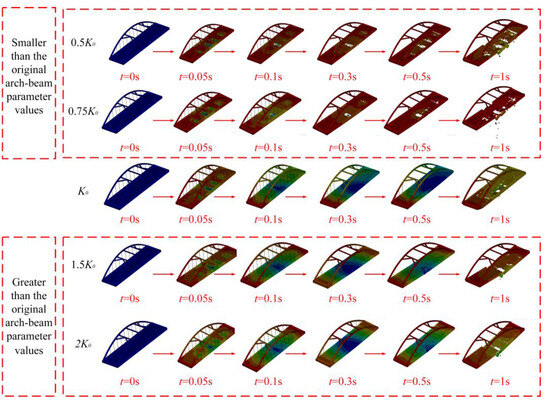

The Simple–Johnson–Cook damage failure model is employed to simulate the progressive damage and failure behavior of the bridge’s residual structure. This model quantifies the extent of material damage using the dimensionless damage parameter D. At the initial stage, D is set to 0, and when D reaches or exceeds 1, the material is considered to have failed. The damage parameter D is calculated using the following expression : where denotes the plastic strain increment during a single time step, and represents the failure strain corresponding to the current stress state, strain rate, and temperature at that time step. The failure processes under various arch-beam combination parameters are illustrated in Figure 13. According to the analysis of the bridge failure patterns shown in the figure, when the arch-beam combination parameter is set to 2K0, no beam-dropping failure occurs at the mid-span (i.e., the 1/2 position) of the bridge deck system. However, initial damage begins to appear on both sides of the bridge deck system, and the area of outward crack propagation remains relatively limited. This indicates that an increased arch-beam combination parameter (i.e., a higher relative stiffness of the main beam) does not necessarily lead to improved anti-collapse performance of the bridge deck system. In the context of structural robustness design, the methodology proposed herein can be employed for preliminary trial calculations to determine an appropriate main beam stiffness. This approach facilitates the achievement of favorable progressive collapse resistance while maintaining cost-effectiveness.

Figure 13.

Failure process.

The constitutive behavior of the concrete was characterized using a simplified Johnson–Cook material model. The key parameters were defined as follows: the compressive strength was set to 50 MPa (f’c), while the pressure constant was assigned a value of 40 MPa (A). Damage evolution was governed by the constants D1 = 0.04 and D2 = 1.0. The strain rate sensitivity was accounted for with a constant C of 0.003.

5. Discussion

The present study systematically investigates the influence of hanger damage levels, spatial distribution patterns, and arch-beam combination parameters on the failure mechanism of through tied-arch bridges using LS-DYNA-based damage failure modeling, with a specific case study bridge as the research object. The findings provide critical insights into the structural vulnerability and collapse prevention strategies for this bridge type, which are discussed in detail below.

The results clearly demonstrate that both the severity and spatial distribution of hanger damage significantly govern the failure mechanism of through tied-arch bridges. This aligns with prior research highlighting hangers as critical load-carrying components in tied-arch systems, where their damage can trigger load redistribution and cascading failures. Notably, our study reveals two key risk conditions:

Uniform or symmetric damage distribution across hangers leads to uneven stress redistribution between the arch rib and tie beam, exacerbating local buckling in the deck and accelerating the loss of structural stability. This phenomenon is consistent with observations by Wu et al. [24], who reported that symmetric damage in cable-supported structures disrupts load equilibrium more severely than asymmetric damage. Severe damage to short hangers (typically located near the mid-span or arch springings) poses a higher collapse risk due to their role in resisting concentrated vertical loads from the deck. Short hangers, with stiffer geometric properties, exhibit more abrupt load release upon failure, inducing impulsive forces that propagate through the arch-beam system—an effect less pronounced in longer, more flexible hangers. These findings emphasize the need for targeted maintenance strategies: prioritizing inspection and reinforcement of short hangers, and implementing real-time monitoring for early detection of symmetric damage patterns, which may otherwise remain unnoticed in conventional visual inspections.

The arch-beam system, as the primary load-resisting framework of through tied-arch bridges, is shown to play a critical role in mitigating progressive collapse. The case study indicates that the original design parameters (e.g., arch rib stiffness, tie beam cross-sectional dimensions, and arch-to-beam stiffness ratio) achieved an optimal balance between load-bearing capacity and deformation compatibility. This aligns with the principle that arch-beam interaction should be tailored to distribute both vertical and horizontal forces efficiently. Notably, deviations from the original parameters—such as reducing arch rib stiffness or increasing tie beam flexibility—led to either excessive arch deformation (risking rib buckling) or overloading of the tie beam (causing tensile failure). This contrasts with studies on truss-arch bridges, where higher beam flexibility can sometimes enhance energy dissipation, highlighting the unique mechanical behavior of through tied-arch systems. The superior performance of the original design in collapse prevention, coupled with its cost-effectiveness, underscores the importance of optimizing arch-beam parameters during the initial design phase rather than relying solely on post-construction retrofits.

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the numerical model assumes idealized damage initiation (e.g., uniform corrosion or sudden fracture), whereas real-world hanger damage often involves gradual degradation (e.g., fatigue cracking) or environmental factors (e.g., moisture-induced material deterioration). Future work should integrate probabilistic damage evolution models to better simulate realistic failure conditions. Second, the case study focuses on a single bridge configuration, and the generalizability of findings to other through tied-arch bridges (e.g., with different span ratios or hanger layouts) requires validation. Expanding the analysis to a broader range of bridge geometries could identify universal vulnerability patterns. Finally, dynamic effects (e.g., traffic loads or seismic excitation) were not considered in the present static/dynamic-coupled simulations. Incorporating time-dependent loads would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how hanger damage interacts with dynamic stress cycles to accelerate collapse.

In conclusion, the study’s outcomes have direct implications for engineering practice. For existing through tied-arch bridges, the identified high-risk damage patterns (uniform distribution and short hanger failure) should inform maintenance protocols, such as prioritizing non-destructive testing of short hangers and deploying sensor networks to monitor symmetric load redistribution. For new designs, the optimal arch-beam parameters highlighted herein offer a reference for balancing safety and cost, ensuring that structural resilience is embedded in the design phase rather than retrofitted reactively.

6. Conclusions

A three-dimensional finite element model is developed using Workbench and LS-DYNA to analyze the dynamic time-history responses resulting from the fracture of a pair of hangers. By incorporating a damage failure model, this study investigates the effects of hanger damage severity and arch-beam combination parameters on the failure mechanism of a through tied-arch bridge. The conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) The accuracy of the finite element model of the bridge presented is validated through integration with the load test report. The PK damage failure model is employed to simulate the dynamic response induced by hanger fracture. Experimental verification demonstrates that the simulated hanger-breaking effect aligns well with the actual test results, indicating its suitability for dynamic response simulation of hanger fracture in tied-arch bridges.

(2) The damage severity of different hangers has a significant influence on the failure mechanism of through tied-arch bridges. When the hanger damage is distributed homogeneously (similarly) across the entire bridge, maintenance and repair should be prioritized. Conversely, when the damage in longer hangers is more severe compared to that in shorter hangers, maintenance and repair efforts should be prioritized accordingly.

(3) Various arch-beam combination parameters can influence the failure mechanism of through tied-arch bridges. For the bridge case analyzed in this study, the originally designed arch-beam combination parameters yield the best performance in preventing progressive collapse and demonstrate optimal comprehensive cost-effectiveness, thereby achieving a balanced trade-off between structural safety and economic efficiency.

Author Contributions

B.-H.F.: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. Q.S.: Writing—original draft, Software, Resources. S.-G.W.: Writing—review and editing. Q.C.: Supervision, Formal analysis. B.-B.Z.: Investigation, Resources. J.-Q.Z.: Investigation, Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (grant no. 2024J01355).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Sinohydro Bureau 16 Co., Ltd. for providing the experimental data and research conditions during the research period.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qiang Chen and Bin-Bin Zhou was employed by the company Sinohydro Bureau 16 Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Data summary of axial forces in remaining hangers (Units: kN).

Table A1.

Data summary of axial forces in remaining hangers (Units: kN).

| Conditions | No.1 | No.2 | No.3 | No.4 | No.5 | No.6 | No.7 | No.8 | No.9 | No.10 | No.11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The breakage of No.1 | Before the fracture | 17.04 | 23.18 | 22.09 | 22.31 | 20.85 | 20.92 | 20.28 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | / | 35.68 | 24.07 | 24.11 | 22.76 | 22.00 | 21.92 | 21.46 | 21.99 | 21.69 | 17.48 | |

| Change ratio (%) | / | 53.93 | 8.963 | 8.068 | 9.161 | 5.163 | 8.087 | 2.282 | 2.279 | 2.894 | 0.807 | |

| The breakage of No.2 | Before the fracture | 17.91 | 22.89 | 22.79 | 22.31 | 20.85 | 20.92 | 20.28 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | 30.72 | / | 39.07 | 29.43 | 24.37 | 23.09 | 27.32 | 27.05 | 27.86 | 27.62 | 21.21 | |

| Change ratio (%) | 71.52 | / | 71.43 | 31.91 | 16.88 | 10.37 | 34.71 | 29.93 | 29.58 | 31.03 | 22.32 | |

| The breakage of No.3 | Before the fracture | 17.91 | 20.77 | 21.86 | 22.51 | 21.70 | 22.16 | 20.28 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | 24.75 | 37.00 | / | 35.31 | 26.21 | 24.58 | 24.31 | 25.23 | 27.21 | 26.98 | 20.30 | |

| Change ratio (%) | 38.19 | 78.14 | / | 56.86 | 20.78 | 10.92 | 19.87 | 20.26 | 26.56 | 27.99 | 17.07 | |

| The breakage of No.4 | Before the fracture | 17.91 | 21.81 | 22.09 | 22.11 | 21.70 | 22.16 | 20.28 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | 20.86 | 29.76 | 38.07 | / | 38.83 | 26.22 | 25.87 | 25.74 | 26.22 | 29.24 | 20.11 | |

| Change ratio (%) | 16.47 | 36.45 | 77.18 | / | 78.94 | 18.32 | 27.56 | 22.69 | 21.95 | 38.71 | 15.97 | |

| The breakage of No.5 | Before the fracture | 17.91 | 21.81 | 20.52 | 21.16 | 21.15 | 21.31 | 20.28 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | 19.85 | 28.62 | 29.90 | 38.97 | / | 36.14 | 28.68 | 26.56 | 24.89 | 26.92 | 20.79 | |

| Change ratio (%) | 10.83 | 37.22 | 45.71 | 87.33 | / | 69.59 | 41.42 | 26.60 | 15.77 | 27.70 | 19.90 | |

| The breakage of No.6 | Before the fracture | 17.91 | 21.77 | 22.79 | 22.31 | 22.15 | 22.44 | 21.48 | 20.98 | 21.50 | 21.08 | 17.34 |

| After the fracture | 20.49 | 26.79 | 25.66 | 27.88 | 38.14 | / | 36.52 | 27.38 | 26.17 | 26.89 | 20.33 | |

| Change ratio (%) | 14.41 | 23.06 | 23.59 | 24.97 | 72.19 | / | 70.01 | 30.51 | 21.72 | 27.56 | 17.24 |

References

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Long, P.H. Calculation and Analysis of Through Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Tied Arch Bridge. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2148, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, M. Damage Identification Method for Tied Arch Bridge Suspender Based on Quasi-static Displacement Influence Line. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 200, 110518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michele, F.G. Stressing Sequence for Hanger Replacement of Tied-arch Bridges with Rigid Bars. J. Bridge Eng. 2022, 27, 04021099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani, H.; Xiang, Y.; Ye, X.; Yun, C.; Shadabfar, M. Localization of Damaged Cable in a Tied-arch Bridge Using Arias Intensity of Seismic Acceleration Response. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.X. Damage Diagnosis and Fretting Wear Performance Analysis of Short Suspenders in Cable-supported Bridges. Structures 2023, 56, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Research on Using Electromagnetic Detection Technology to Identify Broken Wires in Bridge Cables. Bridge Constr. 2020, 50, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhuo, Q. Numerical Analysis on the Impact Effect of Cable Breaking for a New Type Arch Bridge. Buildings 2023, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Miyachi, K. Ultimate Strength and Chain-reaction Failure of Hangers in Tied-arch Bridges. Struct. Eng. Int. 2021, 31, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.F. Local Collapse of a Bridge Under Construction in the Urban Section of Hangzhou-Shaoxing-Taizhou expressway. Shaoxing E. News. 2021, 5, 10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.W. A Boom Damage Prediction Framework of Wheeled Cranes Combining Hybrid Features of Acceleration and Gaussian Process Regression. Measurement 2023, 221, 113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Kahla, N.; El Ouni, M.H.; Ali, N.B.H.; Khan, R.A. Nonlinear Dynamic Response and Stability Analysis of a Tensegrity Bridge to Selected Cable Rupture. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Agrawal, A.K.; El-Tawil, S.; Bhattacharya, B.; Wong, W. Dynamic Response and Progressive Collapse of a Long-span Suspension Bridge Induced by Suspender loss. J. Struct. Eng. 2022, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, K.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, H. Research on Dynamic Response of a Single-tower cable-stayed Bridge with Successive Cable Breaks Based on a 3D Index. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zhang, R.L.; Bi, L.Y.; Zhang, L.; Lv, W.; Dang, L. Study on the Influence of Single Hanger Fracture on the Internal Force Redistribution of the Tied Arch Bridge. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 52, 889–894, 904. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.X.; Yu, Y.G.; Chen, B.C. Dynamic Analysis for Cable Loss of a Rigid-frame Tied Through Concrete-filled Steel Tubular Arch Bridge. J. Vib. Shock. 2014, 33, 144–149. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Ji, R.C. Elastic Stability Analysis of Railway Long Span CFST Arch Bridge. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yan, S. Progressive-collapse Mechanism of Suspended-dome Structures Subjected to Sudden Cable Rupture. Buildings 2023, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.H.; Wang, S.G.; Chen, B.C. Dynamic Effect of Tie-Bar Failure on Through Tied Arch Bridge. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 04020089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.L.; Yang, H.R.; Wu, G.R. Parameter Study on Finite Element Model of Abrupt Hanger-breakage Event Induced Dynamic Responses of Suspension Bridge. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2022, 56, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.L.; Jiang, M.; Huang, C.L. Parametric Study on Responses of a Self-anchored Suspension Bridge to Sudden Breakage of a Hanger. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 512120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi’an Changda Highway Testing Center. Zhengzhou Liujiang Yellow River Highway Bridge (BG-2015-Q2-TS 0507); Xi’an Changda Highway Testing Center: Xi’an, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.W.; Su, M.B.; Wang, C. Static Deflection Difference-Based Damage Identification of Hanger in Arch Bridges. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 5096–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.M.; Wu, Q.X.; Luo, J.P.; Wang, H. Equivalent Static Calculation Method for Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Arch Bridges Considering Dynamic Effect of Suspenders Fracture. China Civ. Eng. J. 2023, 56, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Qiu, W.; Wu, T. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of the self—Anchored suspension bridge subjected to sudden breakage of a hanger. Eng. Fail. Anal. J. 2019, 97, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).