Abstract

A graphoid is a mixed multigraph with multiple directed and/or undirected edges, loops, and semiedges. A covering projection of graphoids is an onto mapping between two graphoids such that at each vertex, the mapping restricts to a local bijection on incoming edges and outgoing edges. Naturally, as it appears, this definition displays unusual behaviour since the projection of the corresponding underlying graphs is not necessarily a graph covering. Yet, it is still possible to grasp such coverings algebraically in terms of the action of the fundamental monoid and combinatorially in terms of voltage assignments on arcs. In the present paper, the existence theorem is formulated and proved in terms of the action of the fundamental monoid. A more conventional formulation in terms of the weak fundamental group is possible because the action of the fundamental monoid is permutational. The standard formulation in terms of the fundamental group holds for a restricted class of coverings, called homogeneous. Further, the existence of the universal covering and the problems related to decomposing regular coverings via regular coverings are studied in detail. It is shown that with mild adjustments in the formulation, all the analogous theorems that hold in the context of graphs are still valid in this wider setting.

Keywords:

mixed-graph graphoid; covering projection; voltage action; homotopy; monoid action; lifting automorphisms; decomposition of coverings MSC:

05C50; 05C20; 05C25; 57M10

1. Introduction

Informally, a covering projection of digraphs (directed graphs) is an onto mapping such that at each vertex, ℘ restricts to a local bijection on incoming arcs and outgoing arcs. This is the only sensible definition that extends the usual concept of a covering projection of two graphs. To build a unified theory of coverings of graphs and coverings of digraphs, it is inevitable to consider coverings of graphoids, that is, coverings of multidigraphs with multiple directed and/or undirected edges, loops, and semiedges. However, in this wider context, the above definition displays unusual behaviour in the sense that the mapping might not correspond to a topological covering of the underlying graphs. This phenomenon was explained and studied in an earlier paper [1], along with a thorough discussion of the problem of lifting automorphisms in the abstract setting in terms of the action of the fundamental monoid as well as combinatorially when reconstructing coverings in terms of voltage assignments on arcs. In that paper, graphoids were called general digraphs.

In the present paper, we go a step further. After reviewing the essential definitions and results from the above-mentioned earlier paper, which we include to make the text easier to follow, we first consider regular coverings of graphoids. Then, comes the existence theorem and an extensive treatment of decomposing projections.

The existence theorem in the context of graphoids is given in terms of the action of the fundamental monoid. A more conventional formulation in terms of a group, the so-called weak fundamental group, is possible because the action of the fundamental monoid is permutational. The standard formulation in terms of the fundamental group, as it is known in topology, holds for a restricted class of coverings, called homogeneous coverings. Finally, we consider the decomposition of coverings, particularly the decomposition of regular coverings of graphoids. It is shown that with mild adjustments, all theorems regarding decomposing regular coverings of graphs are still valid in this wider setting. The results of the present paper were presented by the first author at the Bled conference in 2019.

In Graph Theory, covering space techniques appeared in the early seventies with the works of Biggs [2], Djoković [3], Gross [4], and Ezzel [5]. In the next decade, further developments took place (see, for instance, Biggs [6] and Škoviera [7]), which culminated with the appearance of the monograph by Gross and Tucker [8]. From a long list of authors who in the past 30 years used covering techniques in studying symmetries of graphs we mention Archdeacon, Brodnik, Conder, Du, Feng, Gramlich, Gvozdjak, Hofmann, Hofmeister, Jones, Kuzman, Kwak, Li, Ma, Malnič, Marušič, Neeb, Nedela, Potočnik, Požar, Sato, Šiřán, Šparl, Venkatesh, Waller, Wang, Xu, and Zhu, among others. See [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] and the references therein.

Covers of digraphs were probably first studied by Dörfler, Harary, and Malle [30]. A different formalisation of objects that we call graphoids was recently introduced by Fiala and Seifrtová [31].

2. Preliminaries

For the benefit of the reader, we first review the essential definitions and certain results from [1], some of which are appropriately reformulated for convenience.

2.1. Graphoids

A graphoid (or a general digraph) is an ordered 4-tuple , where is a set of vertices, is a set of darts, and is a function (bd stands for “border”) that assigns to each dart an ordered pair of (not necessarily distinct) vertices , its initial vertex , and its terminal vertex . Usually, we write . Finally, −1: is a partial involution acting on a subset of darts such that and . A dart without an inverse is either a directed edge (a directed link) when , or a directed loop when . A pair of inverse darts and is called an undirected edge when , an unoriented loop when and , and a semiedge when and . A graphoid in which every dart has an inverse is a graph, whereas when no dart has an inverse, it is a (genuine) digraph. The underlying graph of X is the graph obtained by adjoining a formal inverse to each dart without an inverse. The span is a digraph that has the same sets of vertices and darts as X and the same functions beg and , while the involution −1 is the empty function. An edge in X becomes two “oppositely” directed links in ; an undirected loop becomes a pair of directed loops, while a semiedge becomes a directed loop. The spanning digraph of preferred orientation arising from X is obtained by including in its dart set all darts from X that have no inverse, exactly one of the darts from each pair of distinct darts that are inverse of each other, and all semiedges.

Each dart x determines two arcs, and , defined as traversals and . Note that “opposite” arcs are distinct by definition, , even if this is a semiedge. A walk of length from a vertex u to a vertex v is a sequence , where , such that for each arc in the sequence, we have that

The trivial walk at v is the walk of length 0. Occasionally, the endvertices of a walk are omitted by only giving the sequence of arcs for simplicity. The walk is the inverse walk to W. A walk is a closed walk at v. A graphoid is connected if for each pair of vertices , there exists a walk , which coincides with the connectivity of the underlying graph in the usual (topological) sense. If and are walks, then is the concatenated walk obtained by juxtaposition of the two sequences (and omitting the “middle” vertex v). The set of all closed walks at some vertex (usually referred to as the “base vertex”), equipped with concatenation as the operation, forms a monoid with the involution , called the fundamental monoid at .

Two walks of the same length, and , are congruent, written , whenever for each index , we have

This defines an equivalence relation. If a walk W contains a subsequence of the from or of the form , which means travelling forth and back along a dart (or a dart and its inverse, if it exists), we can delete it. This is called an elementary reduction. A sequence of elementary reductions until no further reductions are possible leads to a reduced walk .

Reduced walks of congruent walks are themselves congruent. In particular, any two reduced walks of a given walk are congruent. Two walks with congruent reduced walks are called homotopic. This defines an equivalence relation, with equivalence classes (the homotopy classes) denoted as . It corresponds to the usual notion of homotopy in the underlying graph. Restricted to the fundamental monoid , the set of homotopy classes forms the fundamental group . The homotopy class is the trivial group element, and . As X is tacitly assumed to be connected, a minimal generating set for can be constructed by taking the homotopy classes of fundamental closed walks at with respect to an arbitrary spanning tree in X. This tree is obtained by taking a spanning tree T in together with the inverses of all darts from T that exist in X. The number of generators is known as the Betti number and is equal to , where is the number of cotree directed links and directed loops in , whereas is the number of semiedges. The group is isomorphic to the free product of copies of (corresponding to generators of infinite order) and copies of (corresponding to semiedges).

Two walks in a connected graphoid X are weakly homotopic if the homotopic changes that transform W to are performed exclusively by deletion and/or insertion of subwalks of the form . This defines an equivalence relation with equivalence classes called weak homotopy classes. Note that each such class contains a unique weakly reduced walk. The weak homotopy classes of closed walks at a vertex constitute the weak fundamental group . There is a natural monoid epimorphism and a group epimorphism .

Weak homotopy in a graphoid X is homotopy in the span . Hence, of a finite graphoid is finitely generated. For X connected, a minimal generating set is formed by the weak fundamental closed walks at defined by the cotree darts relative to a genuine spanning treeT in X arising from a spanning tree T in . The corresponding weak Betti number is . Observe that is a free group of rank .

A homomorphism of graphoids maps the vertex set and the dart set of Y to the vertex set and the dart set of X, respectively, such that , , and . Graphoids and their homomorphisms form a category. Injective, surjective, and bijective homomorphisms are commonly referred to as monomorphisms, epimorphisms, isomorphisms, and automorphisms.

2.2. Coverings of Graphoids

A homomorphism of graphoids is a covering projection (or just a covering for short) if the following two conditions are satisfied:

- (1)

- The mapping ℘ is an epimorphism. It maps the set of vertices of onto the set of vertices of X, and it maps the set of darts of onto the set of darts of X.

- (2)

- For each vertex in , the set of darts with initial vertex is mapped bijectively onto the set of darts with initial vertex , and the set of darts with terminal vertex is mapped bijectively onto the set of darts with terminal vertex .

For a vertex v and a dart x in X, the preimage is called the vertex fibre over v (or just the fibre for short), and is the dart fibre over x. From conditions (1) and (2), it follows that there exists a bijection , which implies that all fibres have equal cardinality whenever X is connected; if this cardinality is n, the covering is n-fold. Additionally, each walk lifts to a unique walk that projects to W and starts at an arbitrarily given vertex . This is the unique walk lifting property. For convenience, we denote the terminal vertex of the walk as . This is an action, the walk action, since the trivial walks act trivially and holds for all walks and .

Coverings of graphoids can be rather incongruent with the standard topological perception of this concept since the induced projection of the underlying graphs may not be a topological covering. Consider, for instance, the following trivial examples from [1].

Example 1.

There is a covering , where denotes the directed 4-cycle and is the complete graph on two vertices. Similarly, two directed loops attached at a common vertex project as a covering onto an undirected loop . As a third example, consider the covering projection from a directed 3-cycle onto the semistar with one semiedge. The induced maps of the corresponding underlying graphs , , and are not covering projections. Note that illustrates the need to consider the positive and negative traversals of a semiedge as distinct entities: the positive traversal of lifts to a walk consistent with the natural orientation of , whereas the negative one lifts to a walk that goes against it.

The reason behind these anomalies is that a dart without an inverse is mapped to a dart that has an inverse. We define a covering projection of graphoids as homogeneous whenever no dart in without an inverse is mapped to a dart that has an inverse. This notion is relevant because of the fact described below.

Theorem 1.

Let be an onto homomorphism of graphoids. Then, the associated homomorphism of the underlying graphs is a covering projection if and only if is a homogeneous covering.

A less restrictive concept than the homogeneity of coverings is inverse consistency. A covering projection is inverse-consistent whenever two darts and in must form a pair of inverse darts provided that they project to a pair of inverse darts in X. Note that a homogeneous covering is inverse-consistent, but the converse does not hold. Another important fact is that a composition of two covering projections is a covering projection. Moreover, the composition of inverse-consistent coverings is inverse-consistent, and the composition of homogeneous coverings is homogeneous. However, a composition of a homogeneous covering and a non-inverse-consistent one can be inverse-consistent, as illustrated by the following examples from [1].

Example 2.

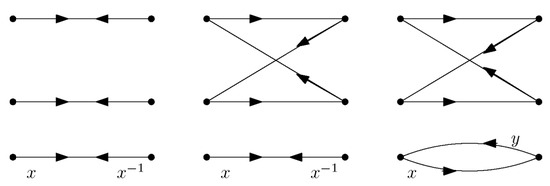

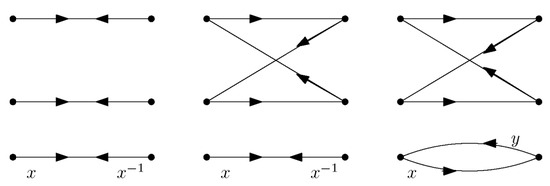

For example, the projection is homogeneous, whereas is not inverse-consistent. Yet their composition is inverse-consistent. The projection of two copies of onto is a graph covering and hence homogeneous. The projection is an inverse-consistent yet non-homogeneous covering, whereas is a covering projection of genuine digraphs and hence homogeneous (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coverings , , and from Example 2.

2.3. Isomorphism and Equivalence of Covering Projections

We restrict our consideration to inverse-consistent coverings in the class of all coverings , where X is a given connected finite graphoid. The covering is connected whenever is also connected. The reason for restricting to inverse-consistent coverings is that certain structural properties cannot be analysed algebraically in a sufficiently meaningful manner when coverings are not inverse-consistent.

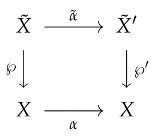

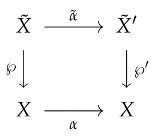

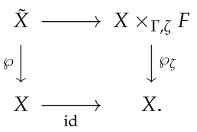

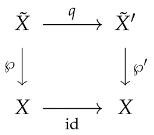

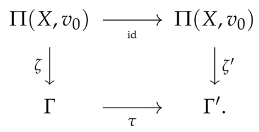

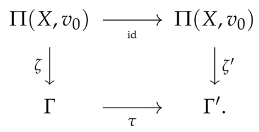

Let and be covering projections of graphoids. A morphism of covering projections is a pair of graphoid homomorphisms and such that the following diagram is commutative:

This is denoted as . If in the above diagram, and are isomorphisms, then is an isomorphism of covering projections. This is a standard concept that formalises the intuitive notion of “coverings that are structurally the same”. In particular, and are equivalent whenever there exists an isomorphism of the form . Observe that the set of self-equivalences forms a group, called the group of covering transformations.

This is denoted as . If in the above diagram, and are isomorphisms, then is an isomorphism of covering projections. This is a standard concept that formalises the intuitive notion of “coverings that are structurally the same”. In particular, and are equivalent whenever there exists an isomorphism of the form . Observe that the set of self-equivalences forms a group, called the group of covering transformations.

This is denoted as . If in the above diagram, and are isomorphisms, then is an isomorphism of covering projections. This is a standard concept that formalises the intuitive notion of “coverings that are structurally the same”. In particular, and are equivalent whenever there exists an isomorphism of the form . Observe that the set of self-equivalences forms a group, called the group of covering transformations.

This is denoted as . If in the above diagram, and are isomorphisms, then is an isomorphism of covering projections. This is a standard concept that formalises the intuitive notion of “coverings that are structurally the same”. In particular, and are equivalent whenever there exists an isomorphism of the form . Observe that the set of self-equivalences forms a group, called the group of covering transformations.In concrete cases, the essential task is to classify (connected) inverse-consistent coverings in up to equivalence, or possibly up to isomorphism. Also of interest is studying the symmetry properties of in terms of the symmetry properties of X. A first step in this direction is a special case of the isomorphism problem, the problem of lifting automorphisms: Given an automorphism , is there an automorphism such that is a self-isomorphism, or an automorphism, of ℘?

The above questions can be studied algebraically in terms of the action of the fundamental monoid via unique walk lifting on , as follows.

Theorem 2.

Let be a covering projection of graphoids, where X is connected. Then, the following statements hold:

- (i)

- The connected components of are in a one-to-one correspondence with the orbits of the action of on the fibre through unique walk lifting. In particular, is connected if and only if the action of is transitive.

- (ii)

- Let . Then, the induced monoid homomorphism (denoted by the same letter for simplicity) is a monomorphism, and the stabiliser of the action of , which consists of all those closed walks at that lift as closed walks at , is equal to .

Theorem 3.

The inverse-consistent covering projections and , where X is connected, are isomorphic if and only if there exists an automorphism and a bijection such that holds for all closed walks at .

This defines the lifted isomorphism on vertices (which naturally extends to darts) by the rule , where is an arbitrary walk. Consequently, is an isomorphism of coverings.

Note that the above monoid actions are permutational because the representation homomorphism is, in fact, a homomorphism into the right symmetric group . Such monoid actions have a lot in common with group actions. Also note that the induced monoid isomorphism is denoted by the same letter for simplicity.

The system of “action equations”, as in Theorem 3, states that projections are isomorphic if and only if maps the action of on isomorphically onto the action of on . We call such an induced monoid isomorphism admissible for the respective monoid actions. Actually, this is how Theorem 3 was formulated in [1]. In particular, and are equivalent if and only if the actions of on and are equivalent, that is, holds for all closed walks W at .

If the covering is connected, then by the unique walk lifting we have that the action of is semiregular, and each lift of an automorphism is determined by the mapping of just one vertex. Moreover, an isomorphism of actions and the lifting condition in Theorem 3 can be expressed in terms of the stabilisers of the fundamental monoids, similarly as in the context of transitive group actions.

Corollary 1.

Let and be connected inverse-consistent covering projections, and let in and in . Then, there exists an isomorphism such that and if and only if α maps the stabiliser isomorphically onto the stabiliser . The isomorphism is uniquely determined by α. In particular, ℘ and are equivalent if and only if , for some and .

Theorem 3 gives a necessary and sufficient condition in terms of an infinite number of action equations. However, the corresponding system can be made finite if we replace the monoid actions with the actions of the weak fundamental groups. This can be done since the following holds.

Theorem 4.

Along a covering projection, weak homotopy lifts, whereas homotopy lifts if and only if the covering is homogeneous.

Theorem 4 implies that if are weakly homotopic, then . It follows that there is a well-defined action of the weak homotopy group on , which acts “in the same way” as . The above remarks immediately imply the following.

Corollary 2.

In Theorems 2 and 3 and Corollary 1, the action of the fundamental monoid can be replaced with the action of the weak fundamental group. With homogeneous coverings, and only with homogeneous coverings, we can use the action of the fundamental group instead of .

This is relevant for performing computations in concrete examples. The action equations stated in Theorem 3 can be replaced with . Again, note that is actually the induced mapping of the weak fundamental groups, denoted by the same symbol for simplicity. To further simplify this system of equations, we only need to consider the finite number of generators of . Actually, we only need to consider the weak fundamental closed walks at . In the case of homogeneous coverings, we can use the action of the homotopy group , and Theorem 3 can be reformulated as in topology.

2.4. Combinatorialisation in Terms of Voltage Actions

Let be a graphoid, and let be a group that acts on a labelling set F on the right, with representing the corresponding permutation. The group action is denoted as , and the corresponding induced permutation is . The group is called the voltage group, whereas F is the abstract fibre.

Furthermore, let be a voltage function that assigns to each dart its voltage . The derived graphoid has a vertex set and a dart set . The functions beg and are defined by

The partial involution is defined for darts for which exists and . Then, .

Theorem 5.

The mapping , given by the projections onto the first coordinate and , is an inverse-consistent covering projection. If we require that (where denotes the inverse group element, not the inverse function) holds whenever exists, then the corresponding covering is homogeneous.

The mapping is called the derived covering projection. Important special cases include permutation voltages (with the natural action on of the right symmetric group ); coset voltages, also known as relative voltages (with an arbitrary group acting by right multiplication on the set of right cosets of some subgroup ); and regular voltages, also known as ordinary or Cayley voltages (with an arbitrary group acting by right multiplication on itself).

Theorem 6.

If we have an inverse-consistent covering projection , then there exists a derived covering such that the following diagram is commutative: Furthermore, if the projection is homogeneous, then we can assume that holds whenever a dart x has an inverse.

Furthermore, if the projection is homogeneous, then we can assume that holds whenever a dart x has an inverse.

Furthermore, if the projection is homogeneous, then we can assume that holds whenever a dart x has an inverse.

Furthermore, if the projection is homogeneous, then we can assume that holds whenever a dart x has an inverse.In view of Theorem 6, the symmetry properties of inverse-consistent coverings can be studied combinatorially in terms of voltages. This holds also because an automorphism has a lift along a given covering if and only if it lifts along any other equivalent covering (observe that an automorphism that lifts along a given covering might not lift along an isomorphic covering). To consider the lifting problem combinatorially, we first extend the voltage function to a function defined on walks. The voltage of a walk W, denoted as or , is defined recursively, as follows:

This implies that inverse walks receive inverse voltages, . Consequently, the mapping

defines a monoid homomorphism into the voltage group. Its image is called the local voltage group at . Moreover, since any two weakly homotopic walks have the same voltage, there is a group homomorphism (denoted by the same letter for simplicity). Additionally, if the covering is homogeneous, we may assume that the voltage function satisfies (whenever exists). Then, homotopic walks have the same voltage, and so there exists a group homomorphism (again denoted by the same letter).

The voltages of the weak fundamental closed walks at form a generating set for . Let T be a genuine spanning tree, and let be the darts not in T. Denote by the corresponding weak fundamental closed walks defined by T and the positive arcs defined by the cotree darts. If W is a closed walk traversing (in this order) the arcs not in T, then W and are weakly homotopic and thus have the same voltage: . In the case of a homogeneous covering, the local group is generated by the voltages of the fundamental closed walks at .

Theorem 7.

A walk in X lifts along the derived covering by the rule

The bijection , defined by , establishes an equivalent action of on the abstract fibre, written , with the operation defined as

In view of (1), we have , and so the abstract action of as a subaction of is induced by the action of via unique walk lifting. Moreover, the action induced by can be substituted by the action induced by or by the action induced by in case the covering is homogeneous. Consequently, all previous facts about the orbits, stabilisers, and isomorphism of covering projections are conveniently rephrased in terms of voltages, as summarised in the next two results.

Corollary 3.

Let be a covering projection, where X is connected. Then, the following statements hold:

- (i)

- The connected components of the derived graphoid are in bijective correspondence with the orbits of in its action on F. In particular, the covering is connected if and only if acts transitively.

- (ii)

- Closed walks at the vertex are in bijective correspondence with closed walks at whose voltages belong to the stabiliser .

Corollary 4.

Let and be the derived covering projections of a connected graphoid X. Then, an automorphism lifts to an isomorphism if and only if there exists a bijection that satisfies the following system of action equations:

where W runs through the weak fundamental closed walks at (which can be replaced with fundamental closed walks when the covering is homogeneous).

Corollary 4 states that two coverings are isomorphic if the action of is mapped isomorphically onto the action of by . In particular, the coverings are equivalent whenever the actions of and are equivalent.

A bijection that satisfies the finite system of “action equations” (2) describes the mapping of the base fibre , . By Theorem 3, this uniquely determines the action of on other vertices. Indeed, let . If is an arbitrary walk, then

The voltage functions and are typically taken with respect to the same voltage action of on . Corollaries 3 and 4 provide several specific results for different voltage actions, with permutation and regular voltage actions being the most interesting cases. For instance, when dealing with permutation voltages, the necessary and sufficient lifting condition (2) can be rewritten as a system

of permutation equations in . The problem is known as the simultaneous conjugacy problem (see [10,26]).

If a connected covering is reconstructed using regular voltages, the system of action Equations (2) can be written as: . In particular, for a covering transformation, the condition reduces to for . As each covering transformation is uniquely determined by the mapping of one vertex, we have , where the action of on the base vertex fibre is given by

Furthermore, has the same action on all fibres. Indeed, let be an arbitrary walk. Since , there is a closed walk W at with . Thus, has a trivial voltage. By (3), we have that , as required.

It is important to note that the voltage action is given by the right multiplication of on itself, whereas the action of on the labelling set is given by the left multiplication of on itself. Also, in the connected case, the action of is semiregular on darts as well. In particular, the action on the dart fibre at u is given by .

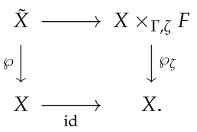

An alternate method for treating isomorphisms of coverings involves replacing admissible isomorphisms between monoids (weak fundamental groups, fundamental groups) with admissible isomorphisms between local groups, as shown on the following diagram:

Because the fundamental monoids act permutationally, projects to if and only if maps the algebraic kernel isomorphically onto . Since we are tacitly assuming that the base graphoids are finite, the above condition can be expressed by requiring that the following implication

holds for all closed walks at (actually, for all weak homotopy classes of walks at , which can be replaced with the homotopy classes of walks whenever the covering is homogeneous). For simplicity, we state the next result in terms of monoids.

Corollary 5.

Let and be the derived covering projections of a connected graphoid X. Further, let be an automorphism. Then the following statements hold:

- (i)

- Suppose that projects to an isomorphism . Then, α lifts to an isomorphism of covering projections if and only if is admissible for the action of local groups.

- (ii)

- Suppose that the local groups act faithfully. Then, α lifts to an isomorphism of covering projections if and only if α projects to an admissible isomorphism .

Please note the subtle difference in assumptions in (i) and (ii). In (i), we assume that projects to an isomorphism, whereas in (ii), we do not need to make this assumption beforehand. Corollary 5 has several useful consequences in cases when the voltage actions or isomorphisms are of a special kind, in particular, when a connected covering is given by regular voltages [1]. Since any isomorphism between groups that act regularly is an isomorphism of actions, it follows from part (ii) of Corollary 5 that condition (5) alone is necessary and sufficient for an automorphism of the base graphoid to lift. We summarise these remarks below.

Corollary 6.

Let and be connected derived coverings by regular voltages. An automorphism lifts to an isomorphism if and only if for all (weak homotopy classes) of closed walks at , the following implication holds:

For homogeneous coverings, it is sufficient to consider homotopy classes of closed walks at .

In particular, the coverings are equivalent if and only if holds. Alternatively, there is an isomorphism between the voltage groups such that

2.5. T-Reduced Voltages

Local groups at different vertices are conjugate subgroups of . If is an arbitrary walk, then implies . However, there is an easy way to transform a given voltage function to an equivalent function , where all local groups are equal. We simply need to ensure that the voltages of closed walks at remain unchanged. To achieve this, we use a genuine spanning tree T of X. A voltage function is referred to as T-reduced if each dart in T carries the trivial voltage.

Theorem 8.

Let be a derived covering projection, and let T be a genuine spanning tree of X. Set

where is the weak fundamental closed walk at determined by the cotree dart x in X. Then, is a T-reduced voltage function with the property that for each closed walk W at . Furthermore, the derived covering projection arising from is equivalent to ℘. The local group remains unchanged and can be chosen as the (new) voltage group.

Proof.

Let W be an arbitrary closed walk at a base vertex . Denote by the arcs not in T that are traversed (in this order) by W, and let be the respective weak fundamental closed walks determined by the above cotree darts. Then, . The voltage function is T-reduced by construction, and since the subwalks of W that belong to T have trivial -voltage. As by definition, we have . Thus, the actions of on F via unique walk lifting with respect to and are the same:

Consequently, the derived projection arising from is equivalent to ℘ by Theorem 3. The last claim stated in the corollary is obvious. □

3. Regular Coverings

3.1. The Concept

If one is to single out a particularly nice class of covering projections, the choice is to focus on regular coverings. Their importance is justified not only because they are the easiest to deal with but also because they play such a vital role in analysing the symmetry properties of covering (di)graphs in terms of the symmetry properties of smaller base (di)graphs. This broadens their significance in the study of graphoids as well.

An inverse-consistent covering projection of graphoids, where X is connected, is considered to be regular if the fundamental monoid acts with all stabilisers being equal. The common stabiliser is denoted as for convenience. Coverings that do not meet this criterion are called irregular.

It is important to note that a regular covering is inverse-consistent by definition. Although the stabilisers of can be all equal even if the projection is not inverse-consistent, the structural properties of the covering can only be studied combinatorially in terms of voltages if the covering is inverse-consistent. This is because the action of on the vertex set cannot generally differentiate between a pair of inverse and non-inverse darts projecting to a pair of inverse darts.

Example 3.

A typical example of a regular covering is taking the quotient projection by the action of a semiregular group of automorphisms of the graphoid Y. By a semiregular action, we mean that the identity is the only automorphism in H fixing a vertex (and hence a dart). The quotient graphoid is obtained by collapsing the vertex- and the dart-orbits and defining the functions beg and in the quotient in a natural way. Observe that . Note that such a projection is homogeneous. However, a regular covering need not be homogeneous.

Observe that if the covering is regular and disconnected, then all connected components are isomorphic. This follows from Corollary 1 since for any pair of components of the covering, there is a lift of the identity automorphism that takes one component isomorphically to the other. Also, from the definition, it follows that a covering is regular if and only if for each closed walk , its lifted walks are either all closed or all open. Yet another characterisation of regular coverings that is most convenient for the computations in concrete cases is given in Theorem 9.

Theorem 9.

An inverse-consistent covering projection is regular if and only if it can be reconstructed by regular voltages. Additionally, such a covering is homogeneous if and only if the regular voltages satisfy whenever the dart x has an inverse.

Proof.

Suppose that a covering projection is equivalent to a derived covering , where the voltage group acts regularly on F. Then, acts semiregularly on F. By Corollary 3, a closed walk at lifts as a closed walk at if and only if it has a trivial voltage. But then it lifts as a closed walk at all vertices in the fibre. Hence, acts with all stabilisers being equal, and the covering projection is regular by definition. □

For the converse, let be a regular covering, and let be a derived covering by permutation voltages that reconstructs ℘. By Theorem 8, we may assume that the voltage function is T-reduced. In this case, all local groups are equal to the image of the representation homomorphism , and can be taken as the new voltage group. Now, let us consider two cases.

If the covering is connected, then acts transitively with a common stabiliser for all vertices, forcing the voltage group to act regularly on F. Hence, appropriately reconstructs the covering. Moreover, we may take an isomorphic regular action of an abstract group on itself by right multiplication. By selecting an arbitrary vertex of reference in each fibre and relabelling the fibres by the elements of using the above regular action, we may reconstruct the covering in terms of the regular action of on itself by right multiplication.

In addition, we need to consider the case when the covering graphoid has connected components, say, . By the first part above, each of them can be reconstructed by a regular voltage action. Let denote the voltage function on the dart set of X that reconstructs the component . Additionally, since the components are pairwise isomorphic under the action of , we can choose the same voltage group and the same voltage function for all components. So, each component is identified with . The whole covering graphoid is then reconstructed by taking the voltage group , which acts regularly on itself by . Hence, preserves each component , whereas induces a cyclic permutation . The voltage function is defined by the rule . Then, a dart with voltage lifts as . Hence, each component is correctly reconstructed.

If invertible darts receive inverse voltages, then the covering is homogeneous. Conversely, if a covering is homogeneous, then the walk must be lifted to a contractible walk. Hence, in the case of regular voltages, the voltage has a fixed point, and so .

Let us assume that the covering is connected. Then, the necessary and sufficient condition for a connected covering to be regular can be expressed in a variety of ways.

Corollary 7.

An inverse-consistent covering projection of connected graphoids is regular if and only if one of the following equivalent conditions is satisfied:

- 1.

- acts transitively with all stabilisers being equal.

- 2.

- The lifts of any closed walk are either all closed or all open.

- 3.

- The image of the representation homomorphism is a regular subgroup of .

- 4.

- The group acts transitively with a normal stabiliser, denoted as , or, in the case of homogeneous coverings, acts transitively with a normal stabiliser, denoted as .

- 5.

- The covering can be reconstructed in terms of regular voltages.

- 6.

- acts transitively (and hence regularly) on each vertex fibre.

- 7.

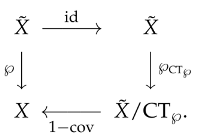

- The homomorphism is a 1-fold covering (see the diagram below).

Proof.

Item (1) is simply the definition of a regular covering combined with the fact that the covering is connected (see Theorem 2), whereas (2) is a simple reformulation of (1). Item (3) follows from (1) combined with the fact that the kernel of the action is the intersection of the stabilisers. Item (4) is a consequence of (1) since and are quotient groups of , and all stabilisers form a conjugacy class of subgroups. Item (5) corresponds to Theorem 9.

Let us consider item (6). First, suppose that a connected covering is regular, and let be arbitrary vertices. Since , by Corollary 1, we have that there is a lift of the identity automorphism taking to . Therefore, acts transitively. Connectivity and the unique walk lifting trivially imply that acts without fixed points. Consequently, acts regularly on . Conversely, let ℘ be a connected inverse-consistent covering such that there is a covering transformation mapping to . By Corollary 1, we have that . Thus, the stabilisers of all vertices in are equal. By definition, ℘ is regular.

In order to prove item (7), observe that with any covering of connected graphoids, we may form the quotient projection since acts semiregularly. This is a homogeneous regular covering with the group of covering transformations equal to (see Example 3). Now, if is regular, then the vertex sets and the dart sets of X and correspond bijectively. However, the graphoids X and need not be isomorphic since ℘ need not be homogeneous. In fact, is a 1-fold covering. Conversely, if is a 1-fold covering, then acts transitively on each fibre in , implying that ℘ is regular. □

Remark 1.

Regarding item 6 above, observe that also acts regularly on each dart fibre. Note, however, that a group acting semi(regularly) on the set of darts need not act (semi)regularly on the set of vertices. Quotienting by such an action may not result in a covering projection.

Example 4.

As the next example shows, two non-isomorphic covering projections , a regular and an irregular one, may involve the same pair of graphs.

Let Y be a digraph on four vertices A, B, C, and D, informally described as consisting of a directed cycle , two directed 2-cycles and , and a directed loop at each vertex. These three sets of cycles represent three 2-factors. Hence, there is a homomorphism of Y onto a one-vertex digraph X with three directed loops. Each of the three 2-factors is mapped to one of the loops. This defines a regular covering projection .

But in the digraph Y, we can find yet another 2-factorisation: the first 2-factor is formed by the directed 3-cycle and the loop at D, the second one is formed by the directed 3-cycle and the loop at B, whereas the third one comprises both directed loops at A and C, as well as the directed 2-cycle . Thus, the mapping of these three factors onto the digraph X gives rise to a covering projection that is evidently not regular. The only non-identity automorphism that preserves this 2-factorisation is the identity mapping. Thus, the group of covering transformations is trivial.

3.2. Lifting Automorphism Groups along Regular Coverings

Studying the symmetry properties of the covering graphoid in terms of the symmetries of the base graphoid is particularly relevant when a given covering is connected and regular. Typically, such a situation is encountered when taking a quotient by a semiregular group of automorphisms, which, as we have already mentioned, is a homogeneous regular covering. In this context, we do not lift only individual automorphisms. We lift groups of automorphisms.

A group lifts along if each automorphism from G has a lift. The respective covering is called G-admissible. The collection of all lifts of all constitutes a group. This is the largest group in that projects along ℘ to G. By the remarks following Theorem 6, the lifting problem can be studied in terms of voltages. The basic lifting lemma trivially implies the following corollary.

Corollary 8.

Let be a connected derived covering by regular voltages. Then, a group lifts along if and only if the set of closed walks with trivial voltage is invariant under the action of G.

Let a group lift along . Then there is an associated group epimorphism defined by . Its kernel is precisely , the group of covering transformations. Thus, the set of lifts of a particular automorphism is a coset of . Along with the lifting problem, we may naturally consider the following: if a group lifts, determine the isomorphism class of the lifted group, or more precisely, study the extension . Note that if the covering projections ℘ and are equivalent, then the extensions and are isomorphic. This allows us to study this extension combinatorially in terms of voltages. For the relevant results in the context of graphs, see [23,24,25].

The following proposition is one of the most basic results when comparing the symmetry properties of the covering graphoid and the base graphoid. It was initiated by Djokovič [3], who proved that along regular covers of graphs, s-transitive groups lift to s-transitive groups.

Proposition 1.

Let be a connected regular covering projection, and let a group be the lift of a group . Then, for the actions of G and on the respective vertex sets, the following statements hold:

- (i)

- is transitive if and only if G is transitive.

- (ii)

- is semiregular if and only if G is semiregular.

- (iii)

- In particular, is regular if and only if G is regular.

Proof.

Suppose that acts transitively, and let u and v be arbitrary vertices in X. For an arbitrary pair of vertices and , there exists mapping to . But then the corresponding projection maps u to v. Hence, G is transitive on the vertex set of X. Note that in this direction, we do not need the assumption that the covering is regular. For the converse, however, we do. Suppose that G acts transitively on the vertex set of X, and let and be arbitrary vertices in . Then, there exists taking u to v, and there is a lift mapping to some vertex in . But all lifts of form a coset . Because ℘ is assumed to be regular, acts transitively on each fibre, which implies that some lift of takes to . Thus, acts transitively on the vertex set of . This proves (i).

Suppose now that G acts semiregularly on the vertex set of X, and let some fix a vertex . Then, the corresponding projection must fix the vertex u, which implies that . Consequently, . As acts semiregularly, we have . Hence, acts semiregularly on the vertex set of . Again, note that in this direction, the assumption about the regularity of the covering is not needed. As for proving the converse, let act semiregularly on the vertex set of , and suppose that some fixes a vertex . Let be an arbitrary lift and be an arbitrary vertex. If , then, since acts transitively on as the covering is assumed to be regular, there exists a lift fixing . By assumption, , which implies that . Hence, G acts semiregularly on the vertex set of X, as required. This proves (ii).

Claim (iii) is an obvious consequence of (i) and (ii). □

4. Existence Theorem

According to Theorem 3, two inverse-consistent covering projections and are equivalent if and only if the actions of the fundamental monoid on and are equivalent. However, it remains uncertain whether an arbitrarily given abstract permutational action of on a set F actually determines a covering up to equivalence such that the action of via unique walk lifting is equivalent to a given abstract action of on F. Unfortunately, in general, this is not the case. To support this claim, consider the following example.

Example 5.

Let X be a genuine digraph on two vertices u and v with only one dart x, where and . The shortest nontrivial closed walk at u is . This walk generates the fundamental monoid , and since , we have . An action of is defined by specifying the action of W. For instance, let act on by and . This action is permutational, but it cannot be realised via unique walk lifting on any covering digraph as W should act trivially.

What goes wrong in the above example is that weakly homotopic walks do not act in the same way. It transpires that for an abstract action of to be realisable, it is sufficient to require that closed walks in must have the same action provided they are homotopic within a fixed chosen genuine spanning tree. This is the content of the next theorem.

Theorem 10

(Existence theorem for covering projections). Consider a connected graphoid X with a fundamental monoid that acts permutationally and transitively on an abstract set F. Suppose this action is such that any two closed walks W and in have the same action provided they are homotopic within a genuine spanning tree T in X.

Under these conditions, there exists an inverse-consistent covering , up to equivalence, such that the action of on the fibre of via unique walk lifting is equivalent to the given abstract action of on F. To construct this required covering, we take an arbitrary epimorphism , along with the naturally induced action of Γ (which exists) and a T-reduced voltage function given by:

Proof.

Let be the representation homomorphism for the given abstract action of on F, and let be an epimorphism onto a finite group such that inherits the action of . Such a group exists; if nothing else, it is . The induced action of is given by

Choosing a genuine spanning tree T in X, let us define a T-reduced voltage function valued in as follows:

This defines an inverse-consistent derived covering projection . Let be the corresponding submonoid in generated by the fundamental closed walks at defined by the cotree darts of T. Clearly, any walk is homotopic within T to a closed walk . Denote by the action of on F via unique walk lifting. Then,

.

The first equality holds due to unique walk lifting. The second equality holds since W is homotopic within T to . The third equality holds because from the definition of , it follows that q and coincide on the submonoid . (However, and q need not coincide on the whole of (see Example 6). The fourth equality holds because the action of is induced by the abstract action of . Finally, the last equality holds because of the assumption that the walks that are homotopic within T have the same abstract action on F.

We conclude that , and so the action of via unique walk lifting is equivalent to the given abstract action of on F. □

Example 6.

This example shows that ζ and q, as in Theorem 10, need not coincide on the whole of . Let X be a genuine dumbell digraph on two vertices and three darts with and . The spanning tree T is defined by the dart x.

The fundamental monoid is not finitely generated. With and , we have that

where the walk is . Define a monoid epimorphism by setting

where , , and extending the definition on the generating set to the whole of . Next, let act on the set by the rule . This defines an abstract permutational action of on F by setting

The above abstract action of is such that walks, homotopic within T, have the same action. First of all, as , , and , the walks and act trivially, and . Observe now that since X is a genuine digraph, is a free group of rank 2. Moreover, two walks at u are homotopic within T if and only if they are homotopic. The walk is contractible, the walk is homotopic to itself, whereas is homotopic to . The first two act trivially, whereas . Thus, , , and have the same abstract action as their homotopic reductions. Now, an arbitrary walk can be written as a product , where each is , , or some . Its homotopic reduction is . Since each of the factors and have the same action, we may conclude that homotopic walks have the same action, .

Let us now define a covering of by taking a T-reduced voltage function, where , , and . The action of via unique walk lifting is given by

A closed walk is homotopic to a walk from the submonoid . Thus, , and . Note that q and ζ agree on the submonoid since , and . Therefore, the abstract action of and its action via unique walk lifting coincide:

However, for odd since and .

The condition imposed on the abstract action of is equivalent to the requirement that there be an abstract action of the weak homotopy group , which can be replaced with the action of the fundamental group in the case of homogeneous coverings. As the coverings are required to be connected, a transitive action of or is determined by a conjugacy class of stabilisers. The classic formulation of the existence theorem for covering projections is the following.

Corollary 9.

An inverse-consistent connected covering projection is determined by a conjugacy class of subgroups in the weak homotopy group , up to equivalence. Similarly, a homogeneous covering projection is determined, up to equivalence, by a conjugacy class of subgroups in .

5. Decomposition Theorems

5.1. Decomposition of Coverings and the Universal Covering

The composition of two covering projections is a covering projection. Here, we do the opposite: we would like to write a given covering as a composition of two covering projections and .

With ℘ and given, we say that ℘ has a decomposition via . The following theorem resolves the problem of the existence of such a decomposition.

Theorem 11.

Let and be inverse-consistent covering projections. Then, there exists a decomposition if and only if there exists an epimorphism of actions .

Proof.

(Sketch) The proof is similar to the proof of Theorem 2.5 in [1]. If a decomposition exists, it is clear that for and . Conversely, if such an action exists, we extend the mapping to by setting , where . One shows that this mapping is well defined, extends to darts, and is consistent with the involution −1. Further details can be found in the aforementioned reference. □

If the coverings are connected, we have an analogue of Corollary 1.

Corollary 10.

Let and be connected inverse-consistent covering projections. Then, there exists a decomposition if and only if, for an arbitrarily chosen vertex , there exists such that

Equivalently, , or in the case of homogeneous coverings.

A natural consideration arising from decomposition is the following: Given a connected graphoid X, let denote a subclass of connected inverse-consistent coverings . A covering projection is -universal over X if it has a decomposition via any other covering projection in . The graphoid is called the -universal covering graphoid. If it exists, such a covering could rightly be declared as the “largest covering” in . It transpires that for the class of all connected inverse-consistent coverings over X, the universal covering, as it is generally known in the literature, indeed exists and is denoted simply by . The approach to studying covering projections using universal coverings is, in some sense, dual to using voltages and has been successfully applied, particularly in topology.

In view of Theorem 11, a covering arising from the regular action of , where the stabiliser is trivial, can be factorised via any covering arising from a transitive action of . Therefore, the existence theorem guarantees that the universal covering not only exists but is also determined up to equivalence. To construct the universal covering, we essentially need to “unwind” all closed walks. This is because no closed walk should lift as a closed walk, since the stabiliser of the action of the weak fundamental group would not be trivial. Similarly, there exists a universal homogeneous covering that arises from a regular action of .

Theorem 12.

Given a connected graphoid X, the universal covering projection exists; the universal covering digraph is a genuine tree (which is infinite unless X is a genuine tree). For the subclass of homogeneous coverings over X, the universal covering exists; the universal graphoid is a tree (and infinite unless X is a tree with at most one semiedge).

Proof.

Let be the covering obtained using the construction outlined in the existence theorem for the regular action of . The weak homotopy group , , projects isomorphically onto the stabiliser for the action of , which is trivial. Hence, is trivial, and so Y is a genuine tree (a digraph). Next, let be an arbitrary inverse-consistent covering. Then, has a decomposition via ℘ by Theorem 11 because the stabiliser for the action of on is trivial and is contained in the stabiliser for the action of on . Thus, Y has the desired universal property. Additionally, let be any covering with the universal property. Then, there exists a decomposition of via . Hence, is a covering digraph of Y and therefore isomorphic to Y since Y is a genuine tree.

The proof for the class of homogeneous coverings is similar and is left to the reader. □

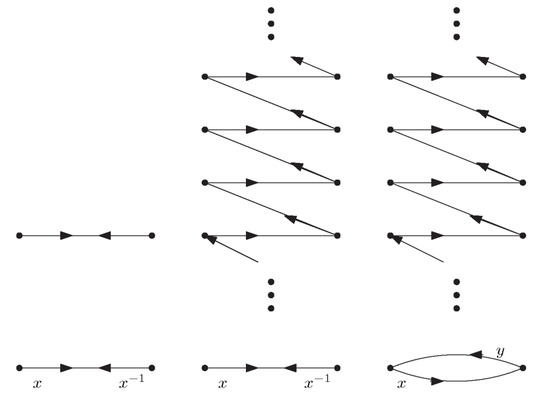

Examples of universal covers of and are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The homogeneous universal covering of graphs, the inverse-consistent but not homogeneous universal covering from the directed infinite path onto , and the homogeneous covering onto the directed 2-cycle.

5.2. Decomposing Regular Coverings

Theorem 11 and Corollary 10 give the necessary and sufficient condition for a decomposition to exist. We would now like to consider the decomposition of regular coverings via regular coverings. However, we have a problem here since the composition of two regular covering projections need not be regular. This is the content of the following theorem.

Theorem 13.

Let a connected covering projection decompose via covering projections, as depicted in the following commutative diagram:

- (i)

- Suppose that q and are regular coverings. Then, ℘ is regular if and only if lifts along q. In this case, is the lift of along q.

- (ii)

- Suppose that ℘ is regular. Then, q is necessarily regular. In contrast, is regular if and only if it is inverse-consistent and projects along q. In this case, projects along q onto .

Proof.

To prove (i), suppose that lifts along q. For an arbitrary let be any of its lifts. Then, , and since , we have that . Thus, , and so . As is transitive on , its lift acts transitively on by Proposition 1. It follows that acts transitively and hence regularly on . As ℘ is inverse-consistent because q and are, ℘ is regular by Corollary 7(6).

For the converse, suppose that ℘ is regular, and let in be an arbitrarily chosen vertex. To prove that lifts along q we need to see, by Corollary 1, that any maps the stabiliser of in its action on to the stabilisers of the action of on . Let . Then, W and project to the same closed walk at since . This means that the lifted walks of W and along q are the lifted walks of along ℘. Because ℘ is assumed to be regular, the lifts of are either all closed or all open. In fact, they must be closed since lifts along q as a closed walk. Thus, the lift of along q is also closed, and so belongs to .

As for the last claim, since acts transitively on and q is regular, the lift acts transitively on . As , and acts regularly on , it follows that . This proves (i).

To prove (ii), first note that q must be inverse-consistent since ℘ is. Let W be an arbitrary closed walk in , and let be the set of its lifts in . Denote by the projection of W along , which is a closed walk in X. Since , the set of walks projects to along ℘. So, . As ℘ is a regular covering, the walks in , and hence in , are either all closed or all open. Thus, q is regular by Corollary 7(2). This proves the first part of (ii).

As for the second part of (ii), suppose that is regular. Since the covering q must be regular by the first part above, and since the composition is regular by assumption, lifts along q to by (i). Thus, projects along q.

Conversely, suppose that is inverse-consistent, and let project along q to . As is transitive on , the projection is transitive on . Hence, is transitive on as it contains . But then is regular. In this case, lifts to by (i), so projects onto . This proves the second part of (ii). □

Remark 2.

If the composition of two regular covering projections is regular, then the group projects along q to , by (i) above. However, if and q are regular and projects along q, then is not necessarily regular since might project to a proper subgroup of . Below is an example.

Example 7.

Let X be a one-vertex graph with one loop and one semiedge, and let Z be the graph on eight vertices , informally described as an 8-cycle with additional edges , , , and , which form a 1-factor. The mapping of the graph Z onto X, where the 8-cycle is wrapped onto the loop while the 1-factor projects onto the semiedge, is a covering projection . This covering is irregular since the only nontrivial automorphism of Z that preserves the orientation of the 8-cycle is the rotation taking , , , and . Hence, . Now, let Y be the complete graph on four vertices . The mapping of Z onto Y, taking , , and , is a regular covering . It wraps the 8-cycle onto the 4-cycle and maps the 1-factor onto the 1-factor . Thus, , and projects to the identity automorphism of Y. Now, mapping Y onto X by wrapping the 4-cycle onto the loop and the 1-factor onto the semiedge is a regular covering . Obviously, . This is an example where q and r are both regular coverings, the group projects along q, and the covering is irregular.

So far, we have considered the decomposition of regular coverings in terms of lifting and/or projecting the groups of covering transformations. As for decomposing a regular covering ℘ via a regular covering , Theorem 11 tells us that ℘ has a decomposition via if and only if

which can be substituted by comparing the (weak) fundamental groups. If the regular coverings are reconstructed by regular voltages, the above condition can be rephrased in a manner that has far-reaching consequences. The simplification stems from the fact that the local group is equal to the voltage group and that the voltage group and the group of covering transformations are isomorphic.

Theorem 14.

Let and be connected regular derived coverings, where is a connected graphoid. Then, has a decomposition via if and only if any of the following equivalent conditions hold:

- (i)

- There exists an epimorphism such that ;

- (ii)

- There is a normal subgroup such that is equivalent to the regular derived covering , where the voltage function is defined by ;

- (iii)

- There is a 1-fold covering , where is a normal subgroup.

Proof.

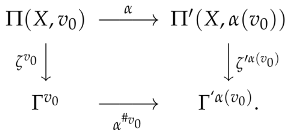

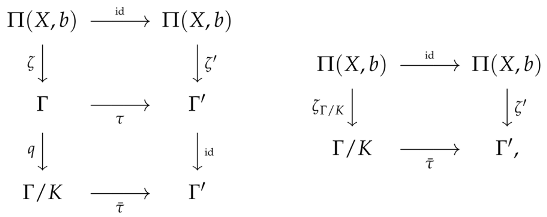

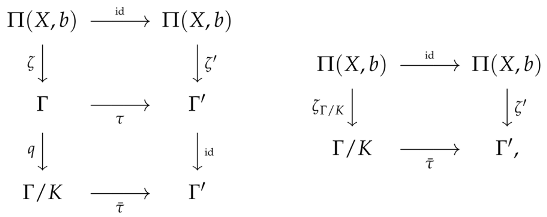

By Theorem 11, has a decomposition via if and only if . But since with regular voltages, the local group is equal to the voltage group, and the stabiliser is equal to the kernel of the local homomorphism, such a decomposition exists if and only if . This is further equivalent to requiring that there exists an epimorphism such that the following diagram

is commutative, which establishes equivalence with (i).

is commutative, which establishes equivalence with (i).

is commutative, which establishes equivalence with (i).

is commutative, which establishes equivalence with (i).Further, the existence of an epimorphism with is equivalent to having an isomorphism , where and , such that the following diagrams

are commutative. The derived covering is then equivalent to by condition (7) of Corollary 6. This establishes equivalence between (i) and (ii).

are commutative. The derived covering is then equivalent to by condition (7) of Corollary 6. This establishes equivalence between (i) and (ii).

are commutative. The derived covering is then equivalent to by condition (7) of Corollary 6. This establishes equivalence between (i) and (ii).

are commutative. The derived covering is then equivalent to by condition (7) of Corollary 6. This establishes equivalence between (i) and (ii).In order to establish equivalence with (iii), suppose first that has a decomposition via . By (ii), we may assume that is equivalent to the derived covering . Hence, has a decomposition , and the covering r is regular by (ii) of Theorem 13. Recall that and . Moreover, by (ii) of Theorem 13, we also have that holds. We now show that .

First note that if is the quotient homomorphism, then is a covering between two regular right voltage actions. This is obvious since is exactly the equality .

Let , , be the regular action by left multiplication, which can be uniquely identified as an element of . If is the quotient mapping, then there is a mapping defined by , that is, . The mapping can be viewed as an element of , and as an epimorphism . The kernel of the homomorphism is . Thus, , as claimed. By (7) of Corollary 7, it follows that taking the regular quotient by the left action of K gives a 1-fold covering , in fact, a 1-fold covering .

Conversely, if a 1-fold covering, as stated in (iii), exists, then has a decomposition via . □

5.3. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we showed that in the context of graphoids, an arbitrary abstract action of the fundamental monoid does not determine a covering for which this action corresponds to the action of the fundamental monoid via unique walk lifting. However, up to equivalence, a covering of graphoids exists for any given abstract action of the weak fundamental group, and an action of the fundamental group determines a homogeneous covering. This extends the classical results valid for graphs and, more generally, in topology.

Also, we discussed decompositions of regular coverings by regular coverings. The next step is to consider the decomposition of G-admissible regular coverings by G-admissible regular coverings, where G is a given group of automorphisms of a fixed connected graphoid X. In general topological spaces, the problem was initiated by Venkatesh [28]. This was then used in [21] to derive a combinatorial approach in terms of voltage actions on graphs, with special emphasis on the elementary abelian coverings, where the group of covering transformations is elementary abelian. Providing non-trivial examples and constructing new interesting families of graphoids with a particular degree of symmetry is also of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.M. and B.Z.; methodology, A.M. and B.Z.; validation, A.M. and B.Z.; formal analysis, A.M. and B.Z.; investigation, A.M. and B.Z.; resources, A.M. and B.Z.; data curation, A.M. and B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and B.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and B.Z.; visualisation, A.M. and B.Z.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, B.Z.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by “Ministrstvo za visoko šolstvo, znanost in tehnologijo Slovenije”, program No. P1-0285. The APC was funded by FAMNIT, Univerza na Primorskem, Glagoljaška 8, 6000 Koper, Slovenija.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Malnič, A.; Zgrablić, B. Covers of general digraphs. Ars Math. Contemp. 2023. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, N.L. Algebraic Graph Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Djoković, D.Ž. Automorphisms of graphs and coverings. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 1974, 16, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gross, J.L. Voltage graphs. Discret. Math. 1974, 9, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezell, C.L. Observations on the construction of covers using permutation voltage assignments. Discret. Math. 1979, 28, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Biggs, N.L. Homological coverings of graphs. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1984, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škoviera, M. A contribution to the theory of voltage graphs. Discret. Math. 1986, 61, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.L.; Tucker, T.W. Topological Graph Theory; Wiley–Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Archdeacon, D.; Gvozdjak, P.; Širáň, J. Constructing and forbidding automorphisms in lifted maps. Math. Slovaca 1997, 47, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Brodnik, A.; Malnič, A.; Požar, R. The simultaneous conjugacy problem in the symmetric group. Math. Comp. 2021, 90, 2977–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, M.D.E.; Ma, J. Arc-transitive abelian regular covers of cubic graphs. J. Algebra 2013, 387, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.F.; Marušič, D.; Waller, A.O. On 2-arc-transitive covers of complete graphs. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 1998, 74, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.A. Elementary abelian regular coverings of Platonic maps. Case I: Ordinary representations. J. Algebr. Comb. 2015, 41, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.Q.; Wang, K. s-Regular cyclic coverings of the three-dimensional hypercube Q3. Eur. J. Comb. 2003, 24, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feng, Y.Q.; Kwak, J.H. s-Regular dihedral coverings of the complete graph of order 4. Chin. Ann. Math. B 2004, 25, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, R.; Hofmann, G.W.; Neeb, K.H. Semi-edges, reflections and Coxeter groups. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2007, 359, 3647–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hofmeister, M. Enumeration of concrete regular covering projections. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 1995, 8, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzman, B.; Malnič, A.; Potočnik, P. Tetravalent vertex-and edge-transitive graphs over doubled cycles. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 2018, 131, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Zhu, Y.Z. Covers and pseudocovers of symmetric graphs. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.02679v1. [Google Scholar]

- Malnič, A.; Nedela, R.; Škoviera, M. Lifting graph automorphisms by voltage assignments. Eur. J. Comb. 2000, 21, 927–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnič, A.; Marušič, D.; Potočnik, P. Elementary abelian covers of graphs. J. Algebr. Comb. 2004, 20, 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, P.; Požar, R. Smallest tetravalent half-arc-transitive graphs with the vertex-stabiliser isomorphic to the dihedral group of order 8. J. Comb. Theory Ser. A 2017, 145, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Požar, R. Sectional split extensions arising from lifts of groups. Ars Math. Contemp. 2013, 6, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Požar, R. Testing whether the lifted group splits. Ars Math. Contemp. 2016, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Požar, R. Computing stable epimorphisms onto finite groups. J. Symb. Comput. 2019, 92, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Požar, R. Fast computation of the centralizer of a permutation group in the symmetric group. J. Symb. Comput. 2024, 123, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I. Isomorphism of some graph coverings. Discret. Math. 1994, 128, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A. Graph Coverings and Group Liftings; preprint; Department of Mathematics, University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Du, S.F.; Kwak, J.H.; Xu, M.Y. 2-Arc-transitive metacyclic covers of complete graphs. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 2015, 111, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, W.; Harary, F.; Malle, G. Covers of digraphs. Math. Slovaca 1980, 30, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Fiala, J.; Seifrtová, M. A novel approach to covers of multigraphs with semiedges. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2024. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).