Abstract

The aim of this research is to estimate the parameters of the modified Frechet-exponential (MFE) distribution using different methods when applied to progressive type-II censored samples. These methods include using the maximum likelihood technique and the Bayesian approach, which were used to determine the values of parameters in addition to calculating the reliability and failure functions at time t. The approximate confidence intervals (ACIs) and credible intervals (CRIs) are derived for these parameters. Two bootstrap techniques of parametric type are provided to compute the bootstrap confidence intervals. Both symmetric loss functions such as the squared error loss (SEL) and asymmetric loss functions such as the linear-exponential (LINEX) loss are used in the Bayesian method to obtain the estimates. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) technique is utilized in the Metropolis–Hasting sampler approach to obtain the unknown parameters using the Bayes approach. Two actual datasets are utilized to examine the various progressive schemes and different estimation methods considered in this paper. Additionally, a simulation study is performed to compare the schemes and estimation techniques.

1. Introduction

In lifetime tests and reliability, it is commonplace for experiments to conclude prior to the failure of all test units. The removal of units prior to failure is frequently due to financial and time constraints. In such circumstances, it can be hard for experimenters to obtain all of the sample information within the restricted length of time during a lifetime test. This brings us to the subject of censoring, in which certain surviving units are removed from the experiment following the use of a specific procedure. A life test is considered to be complete if every test item is followed until it fails. In practice, however, most of the information that is available is incomplete. There are several well known censorship techniques, such as type I and type II; see [1]. The progressive type-II censoring (Pro-II C) technique is described as follows: initially, the experimenter sets n independent and identical units on the measure of life. Assuming that the first failure occurs at time , the remaining surviving units have units randomly removed from them. Assuming that the second failure occurs at time , the remaining surviving units then have units randomly removed from them. When the mth failure occurs at time , the experiment is over and the remaining units are withdrawn from the test. The Pro-II C scheme is denoted by , where the censoring scheme R is predetermined before the experiment. It has been frequently observed that type-II censoring is a special instance of Pro-II C, where the scheme is . If a Pro-II C sample with size m and censoring scheme (where m is the number of failure units and failure unit number i can be denoted by from a complete sample with size n which follows a distribution with the CDF as and PDF as ), then the joint PDF of a Pro-II C sample can be written as

where (for details, see [2]).

As an example of a Pro-II C sample, assume that we are interested in studying the time required for relapse in patients suffering from a specific disease. We enroll 100 patients in the study, and each patient is followed up until relapse or the end of the study. However, due to various reasons such as patient withdrawal or loss to follow-up, the study becomes progressively censored over time. Say that after one year, 20 patients have relapsed and the study has ended. At this time, there are still 50 patients who have not relapsed and remain under observation, while 30 patients have withdrawn from the study. These patients are censored for one year. After two years, 30 patients have relapsed and the study has terminated. At this time, there are still 20 patients who have not relapsed and remain under observation. These patients are censored for two years. Finally, after 3 years, 20 patients have relapsed and the study has been completed. In this example, we have Pro-II C data, with different patients being censored at different times depending on when they entered the study. This type of censoring can pose challenges for statistical analysis, as it requires methods that can handle unequal follow-up times.

For this reason, many researchers have shown interest in Pro-II C samples, such as Balakrishnan [3], who suggested a method for creating Pro-II C samples, and Qin et al. [4], who suggested a new test statistic to determine whether Pro-II C samples are drawn from an exponential distribution. Eryilmaz and Bairamov [5] and Montanari et al. [6] conducted fascinating real applications of Pro-II C samples. Tse et al. [7] stated that impossible to predict how many patients will withdraw from a clinical test at each stage due to the random nature of the phenomenon. Although certain tested units may exhibit no failures, the experimenter might conclude during certain reliability trials that testing these units is inappropriate or risky. In such cases, each failure results in a random pattern of removal. For more information on Pro-II C samples, we suggest some recent sources that have covered this type of Pro-II C samples, such as Khalifa et al. [8], Buzaridah et al. [9], Attwa et al. [10], Chen and Gui [11], Hasaballah et al. [12], and Ramadan et al. [13]. This paper contributes to the topic via application to real data through different progressive schemes, thereby providing a more comprehensive representation of the complete data compared to previous studies.

In certain cases, lifetime data do not match classical distributions. This has resulted in numerous modifications and generalizations of classical distributions with the aim of creating more flexible models that can handle lifetime data. One such model is the modified Frechet-exponential (MFE) distribution proposed by [14], which provides better results than other exponential distributions. Say that A random variable Y has a PDF and CDF with two parameters, with > 0 as a scale parameter and > 0 as a shape parameter, as follows:

then, it can be said that Y follows the MFE distribution, while the survival function is

and the hazard rate function is PROVIDED by

Two real datasets are used to study progressive schemes, which are considered in this paper to estimate parameters under Pro-II C samples. Dataset I is taken from Bjerkedal [15], who conducted an experiment involving the survival times (in days) of a group of 72 guinea pigs, while Dataset II is taken from [16], a study involving the recovery times (in months) for a randomized sample of 128 bladder cancer patients.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: maximum likelihood based on Pro-II C is discussed in Section 2; in Section 3, asymptotic intervals of confidence estimates are derived using maximum likelihood estimates; in Section 4, we derive the confidence interval of unknown parameters using two parametric bootstrap processes; the Bayes estimates for the linear-exponential and squared error loss functions are derived in Section 5; in Section 6, the two real datasets are analyzed; in Section 7, a simulation analysis consisting of three schemes is used to estimate the parameters, and the results are discussed; some of the results obtained in Section 6 and Section 7 are analyzed in Section 8; finally, Section 9 presents our conclusions.

2. Maximum-Likelihood Estimation

In this section, we look at how to estimate MFE parameters using progressive type-II censored samples. Consider , as a Pro-II C sample derived from a life test comprising (n) units selected from a population characterized by a probability density function (PDF) of and CDF of , as provided in Equations (2) and (3), with the censoring scheme . Then, from Equation (1), the likelihood function can be written as follows:

After taking the natural logarithm, the log-likelihood function can be written as follows:

The maximum likelihood estimation of the parameters is obtained by differentiating the log-likelihood function ℓ with respect to the parameters and and setting the result to zero, after which we have the following normal equations:

and

We utilize the Newton–Raphson iteration approach to derive the estimates in Equations (8) and (9), where the two equations do not have closed form solutions. This algorithm is explained in detail in [17]. Moreover, using the invariance property of MLEs, the MLEs of and can be obtained after replacing and by and :

3. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals

In this section, we use the variance–covariance matrix to estimate the asymptotic confidence intervals (CIs) of the modified Frechet-exponential (MFE) distribution parameters when As we know that the MLEs of the MFE distribution parameters cannot be computed in closed forms, we calculate the inverse of the observed information matrix to create confidence intervals (CIs) for the parameters, as follows:

The second derivative of Equations (8) and (9) with respect to and yields Equations (12) and (13):

and

Differentiating Equation (8) with respect to , we obtain

We know that if roughly follows a multivariate normal distribution with mean and covariance matrix under certain regularity conditions (see [18]), then the two-sided confidence intervals of and can be written as follows:

where denotes the percentile of the standard normal distribution with the right-tailed probability .

It is important to determine the variances of and in order to construct the asymptotic CI of the reliability and hazard functions, which are functions in the parameters and . We can compute the estimates of variance of and using the delta approach; for further details about the delta method, see [19]. The variance of and can be respectively approximated by

where the gradients of and concerning and are respectively represented by and

Subsequently, the two-sided confidence intervals for ( S(t) ) and ( h(t) ) at the level can be expressed as follows:

4. Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

To determine the distributional features of a test statistic, it is preferable to use the bootstrap approach, which is an empirical method. It also serves as a way to estimate statistics and standard errors. Resampling plans are classified into three types: parametric, semi-parametric, and non-parametric. For small sample sizes, results based on the asymptotic confidence interval clearly perform poorly. Two bootstrap techniques of parametric type are provided to compute the bootstrap confidence intervals, namely, the percentile bootstrap (Boot-p) confidence interval introduced by Efron [20] and the bootstrap-t (Boot-t) confidence interval proposed by Hall [21]; this provides significantly more information on the population value. Boot-t was developed utilizing a Studentized “pivot”, and requires the variance to be estimated for the MLEs of and .

4.1. Percentile Bootstrap (Boot-p) Confidence Interval

- (1)

- Calculate the ML estimates of the parameters and , say, and .

- (2)

- Produce a Pro-II C sample with size m from the MFE distribution using and from the algorithm described in [22].

- (3)

- Calculate the ML estimates of the bootstrap sample, say, and .

- (4)

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 N times and obtain

- (5)

- Sort the bootstrap estimates to obtain an approximate distribution of and .

Let (z) = P(≤ z) be the CDF of , and define = (z) for a specified value of z; then, the approximation bootstrap-p 100(1 − )% confidence interval of is represented by ().

4.2. Bootstrap-t (Boot-t) Confidence Interval

- (1)

- Repeat steps (1)–(3) in Boot-p.

- (2)

- From the variance–covariance matrix (), we have the t-statistic of as =

- (3)

- Repeat steps 1 and 2 N times and obtain

- (4)

- Sort to obtain an approximate distribution of , , ,…,

Let (z) = P(≤ z) be the CDF of and define = + (z) for a specified value of; then, the approximation bootstrap-t 100(1 − )% confidence interval of = (, is expressed as ().

5. Bayes Estimation

The Bayesian methodology considers parameters as random variables, allowing for the utilization of a joint prior distribution to represent uncertainties in the parameters prior to collecting failure data. Given the limited availability of data, which is a prominent challenge in reliability research, the ability to incorporate prior knowledge into the analysis makes the Bayesian approach highly valuable in this context. In this case, the and parameters are assumed to follow independent gamma prior distributions, as follows:

The hyperparameters and for j = 1, 2 are assumed to be known and set to 0.0003. This choice aims to make the prior distribution non-informative; given that the variance of the gamma distribution is equal to , the prior distribution variance becomes large, reducing its impact on the inference process and reflecting a non-informative attitude regarding prior beliefs about the unknown parameters. For more information on selecting the hyperparameters for the prior distribution, see [23].

The posterior distribution for parameters and can be obtained by combining the likelihood function (6) and priors (15), as follows:

The square error loss (SEL) function is utilized in Bayesian estimation to ensure equivalent losses for both overestimation and underestimation. If represents the parameter that an estimator needs to estimate, then the SEL function can be expressed as follows:

We can compute the Bayes estimate with the SEL function:

where

The expression for the LINEX loss function, which is used to estimate the parameter by an estimator , can be represented as

Hence, the Bayes estimate under LINEX loss function of any function of the parameters and , say, , can be derived as follows:

where

It is important to acknowledge that the analytical solution for the multiple integrals calculation in Equations (17) and (18) is not feasible. Therefore, in order to implement the MCMC technique, we generated samples from the joint posterior density function described in Equation (16) using the Gibbs sampling process. From Equation (16), the joint posterior distribution can be expressed by

The full conditionals for and can be stated as follows, up to proportionality:

Due to the absence of standard forms in the joint posterior of and described in Equations (20) and (21), Gibbs sampling is not a feasible choice. Consequently, the implementation of MCMC requires the utilization of the Metropolis–Hastings sampler. The following is the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm within Gibbs sampling:

- (1)

- Begin with (, ) as an initial guess.

- (2)

- Put .

- (3)

- Generate and from and with the normal proposal distribution using the M-H approach shown below.

- (4)

- Generate a proposal from , var()) and a proposal from , var()).

- (i)

- Calculate the acceptance probabilities

- (ii)

- Produce , and from a uniform (0,1) distribution.

- (iii)

- If < , accept the suggestion and set = , else put = .

- (iv)

- If < , accept the suggestion and set = , else put = .

- (5)

- Calculate the survival and failure hazard functions and (t) by substituting and

- (6)

- Put .

- (7)

- Repeat Steps (3)–(6) N times to obtain , and

- (8)

- To calculate the CRs of and and ,as ; then, the CRIs of is

To facilitate convergence and reduce the influence of initial value selection, the initial M simulated variants are disregarded. Subsequently, the chosen samples are for sufficiently large N.

The Bayes estimates under the SEL function for are provided by

The Bayes estimates under the LINEX loss function for are provided by

6. Applications

In this section, two practical datasets are used to compare various estimation methods in calculating parameter values for the modified Frechet-exponential distribution when using Pro-II C samples. A comparison is made between estimation methods as well as between different drawing schemes for obtaining Pro-II C samples in order to determine the best method.

6.1. Dataset I

Dataset I was obtained from Bjerkedal [15], who conducted an experiment involving a group of 72 guinea pigs. In the experiment, different doses of tubercle bacilli were administered and the survival times of the guinea pigs were recorded in days. The data are presented as follows: 0.1, 0.33, 0.44, 0.56, 0.59, 0.72, 0.74, 0.77, 0.92, 0.93, 0.96, 1, 1, 1.02, 1.05, 1.07, 1.08, 1.08, 1.08, 1.09, 1.12, 1.13, 1.15, 1.16, 1.2, 1.21, 1.22, 1.22, 1.24, 1.3, 1.34, 1.36, 1.39, 1.44, 1.46, 1.53, 1.59, 1.6, 1.63, 1.63, 1.68, 1.71, 1.72, 1.76, 1.83, 1.95, 1.96, 1.97, 2.02, 2.13, 2.15, 2.16, 2.22, 2.3, 2.31, 2.4, 2.45, 2.51, 2.53, 2.54, 2.54, 2.78, 2.93, 3.27, 3.42, 3.47, 3.61, 4.02, 4.32, 4.58, 5.55, 7.

This dataset was utilized to obtain Pro-II C samples because of the K-S statistic and p-value for the modified Frechet-exponential distribution, calculated as K-S = and p-value = , indicating that the MFE distribution is appropriate for this dataset. In addition, the negative of the log-likelihood functions (), Akaike information criterion (AIC) [24], and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were computed as follows: = , AIC = , and BIC = .

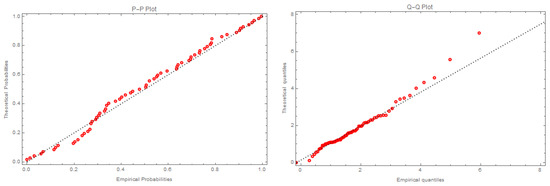

Figure 1 illustrates the empirical probability and empirical quantile functions of the MFED applied to dataset I.

Figure 1.

PP-plot and QQ-plot of MFED for dataset I.

In Table 1, some various progressive schemes were applied to dataset I when the number of failure units m is The comparison was made by calculating the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) statistic and p-value for both the estimated parameters and the complete data.

Table 1.

MLEs, Bayes estimates, and Boot-p and Boot-t estimates.

Table 1 shows the MLEs, Bayes estimates obtained using the SEL function, and estimators using the Boot-p and Boot-t methods based on various progressive schemes ().

From Table 1, we applied the estimation methods described in this paper in more detail to the Pro-II C sample with scheme , where (0.1, 0.33, 0.44, 0.56, 0.59, 0.72, 0.74, 0.77, 0.92, 0.93, 1, 1, 1.02, 1.05, 1.08, 1.08, 1.09, 1.59, 1.95, 2.13, 2.31, 2.78), as its MLE results were close to the MLE results of the complete data in terms of the K-S statistic and p-value. See Appendix A, for guidance on calculating the parameter values of this Pro-II C sample.

Table 2 provides the MLEs of the parameters in addition to the survival and hazard functions at and the Bayes estimates with different values for the shape parameter c of the LINEX loss function.

Table 2.

Estimation of the survival and hazard functions and the parameters of distribution.

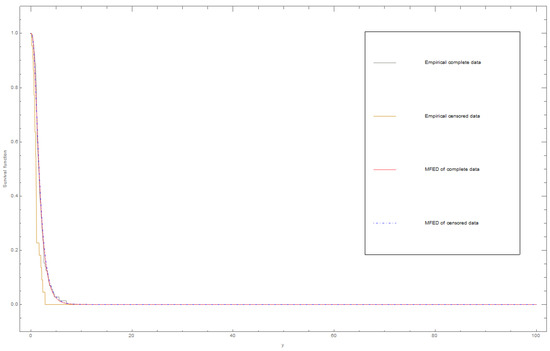

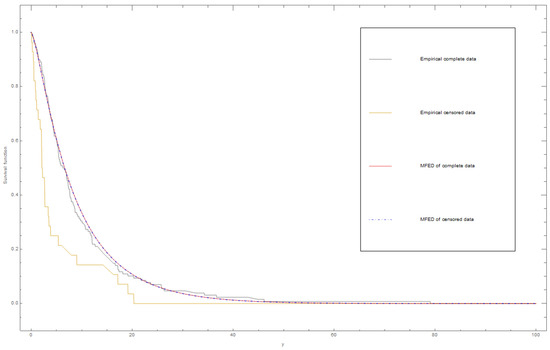

Figure 2 shows the plot of the empirical and fitted survival functions for the complete and censored dataset I using the MLE method.

Figure 2.

Empirical and survival functions for the complete and censored dataset I using the MLE method.

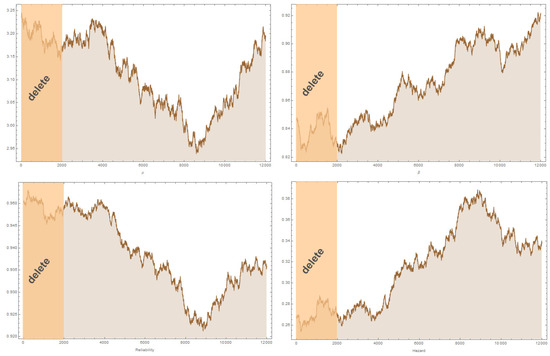

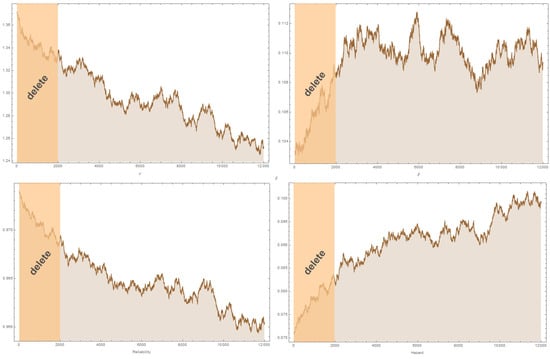

To be more clear about the Bayesian results in Table 2 obtained using the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm within Gibbs sampling, we have added Figure 3, which shows the plots of the 10,000 simulated variants for the parameters of dataset I after we discarded the first 2000 simulated variants.

Figure 3.

Plots of the 12,000 simulated variants for the parameters of dataset I.

Table 3 provides the ACIs and CRIs for and in addition to at .

Table 3.

The and in addition to at .

6.2. Dataset II

Dataset II was obtained from Lee and Wang [16], and consists of the duration of time (in months) to recovery for a randomized sample of 128 patients diagnosed with bladder cancer. Bladder cancer is a medical condition characterized by the abnormal growth of tissue in the bladder. The data are presented as follows: 0.08, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.51, 0.81, 0.9, 1.05, 1.19, 1.26, 1.35, 1.4, 1.46, 1.76, 2.02, 2.02, 2.07, 2.09, 2.23, 2.26, 2.46, 2.54, 2.62, 2.64, 2.69, 2.69, 2.75, 2.83, 2.87, 3.02, 3.25, 3.31, 3.36, 3.36, 3.48, 3.52, 3.57, 3.64, 3.7, 3.82, 3.88, 4.18, 4.23, 4.26, 4.33, 4.34, 4.4, 4.5, 4.51, 4.87, 4.98, 5.06, 5.09, 5.17, 5.32, 5.32, 5.34, 5.41, 5.41, 5.49, 5.62, 5.71, 5.85, 6.25, 6.54, 6.76, 6.93, 6.94, 6.97, 7.09, 7.26, 7.28, 7.32, 7.39, 7.59, 7.62, 7.63, 7.66, 7.87, 7.93, 8.26, 8.37, 8.53, 8.65, 8.66, 9.02, 9.22, 9.47, 9.74, 10.06, 10.34, 10.66, 10.75, 11.25, 11.64, 11.79, 11.98, 12.02, 12.03, 12.07, 12.63, 13.11, 13.29, 13.8, 14.24, 14.76, 14.77, 14.83, 15.96, 16.62, 17.12, 17.14, 17.36, 18.1, 19.13, 20.28, 21.73, 22.69, 23.63, 25.74, 25.82, 26.31, 32.15, 34.26, 36.66, 43.01, 46.12, 79.05.

This dataset was utilized to obtain Pro-II C samples. The K-S statistic and p-value for the modified Frechet-exponential distribution with this dataset were calculated as follows: K-S = and p-value = , indicating that the MFE distribution is appropriate for this dataset. In addition, the negative of the log-likelihood functions (), Akaike information criterion (AIC) [23], and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were computed as follows: = , AIC = , and BIC = .

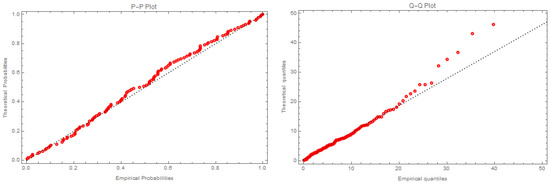

Figure 4 illustrates the empirical probability and empirical quantile functions of the MFED applied to dataset II.

Figure 4.

PP- and QQ-plots of MFED for dataset II.

In Table 4, some various progressive schemes were applied to dataset II when the number of failure units The comparison was made by calculating the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) statistic and p-value for both the estimated parameters and the complete data.

Table 4.

MLEs, the Bayes estimates, and Boot-p and Boot-t estimates.

Table 4 shows the MLEs, Bayes estimates using the SEL function, and estimators using the Boot-p and Boot-t methods based on various progressive schemes ().

From Table 4, we applied the estimation methods described in this paper in more detail on the Pro-II C sample with scheme where 0.08, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.51, 0.81, 0.9, 1.05, 1.35, 1.76, 2.02, 2.02, 2.07, 2.09, 2.23, 2.62, 2.64, 2.69, 3.36, 3.48, 3.82, 5.34, 6.94, 9.02, 14.24, 17.12, 19.13, 20.28), as its MLE results were close to the MLE results of the complete data in terms of the K-S statistic and p-value.

Table 5 provides the MLEs of the parameters in addition to the survival and hazard functions at and the Bayes estimates with different values for the shape parameter c of the LINEX loss function.

Table 5.

Estimation of the survival and hazard functions and the parameters of distribution.

Figure 5 shows the plots of the empirical and fitted survival functions for the complete and censored dataset II using the MLE method.

Figure 5.

Empirical and survival functions for the complete and censored dataset II using the MLE method.

To be more clear about the Bayesian results in Table 5 obtained using the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm within Gibbs sampling, we have added Figure 6, which shows plots of the 10,000 simulated variants for parameters of dataset II after we discarded the first 2000 simulated variants.

Figure 6.

Plots of the 12,000 simulated variants for the parameters of dataset II.

Table 6 provides the ACIs and CRIs for and in addition to at .

Table 6.

The and in addition to at .

7. Simulation

To compare the various methods for estimating the parameters of the MFE distribution for Pro-II C samples, in addition to comparing the various drawing schemes for progressive type-II censored samples, we used initial values of and for the parameters and to generate 1000 progressive type-II censored samples. It is important to note that with (n = 50), 1000 samples of size 50 were generated. To ensure the integrity of the results, various drawing methods were applied to these 1000 samples according to the specified m = 30 and m = 40. Similarly, for the case where (n = 60), 1000 samples were generated and the different drawing methods were applied to these samples to produce Pro-II C samples. Estimates of the parameters and lifetime parameters, including the survival function () and failure function () at t = 0.8 of MFED, were calculated using various estimation methods. In addition, we calculated the mean square error of the estimates, where . In this study, we use the three following progressive schemes:

Scheme I: (, ).

Scheme II: (, ).

Scheme III: (, ).

To determine which scheme is the best, we used the lowest value of the summed mean square error. In addition, the asymptotic MLE and CRI distributions were used to find the 95% CIs, allowing for further comparison of the schemes.

Table 7 presents the estimates obtained through maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian methods for when 2, along with the corresponding mean squared error (MSE) values and confidence intervals.

Table 7.

Estimates for using MLE and Bayesian methods along with their respective MSEs and confidence intervals.

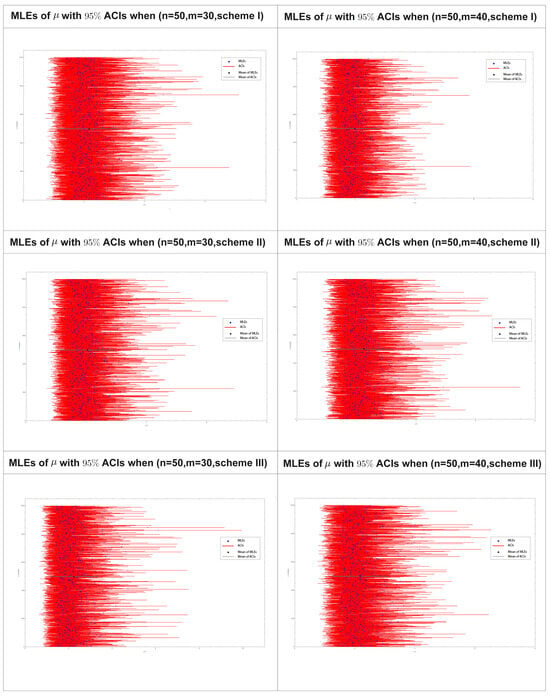

Figure 7 displays the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained using the maximum likelihood estimation distribution of for 1000 progressively type-II censored samples obtained using various drawing schemes, as listed in Table 7 for samples sizes and .

Figure 7.

ACIs of of 1000 Pro-II C samples in Table 7 for various drawing schemes.

From Table 7 and Figure 7 presented above, it is evident that a relationship exists between the effective size (m) and both the mean squared error (MSE) and confidence interval (CI) for , particularly in the first and third schemes. As the effective size increases, there is a decrease in the MSEs and the CIs. This trend is not observed in the second scheme.

Table 8 presents the estimates obtained through maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian methods for when , along with the corresponding mean squared error (MSE) values and confidence intervals.

Table 8.

Estimates using MLE and Bayesian methods with their MSE and confidence intervals.

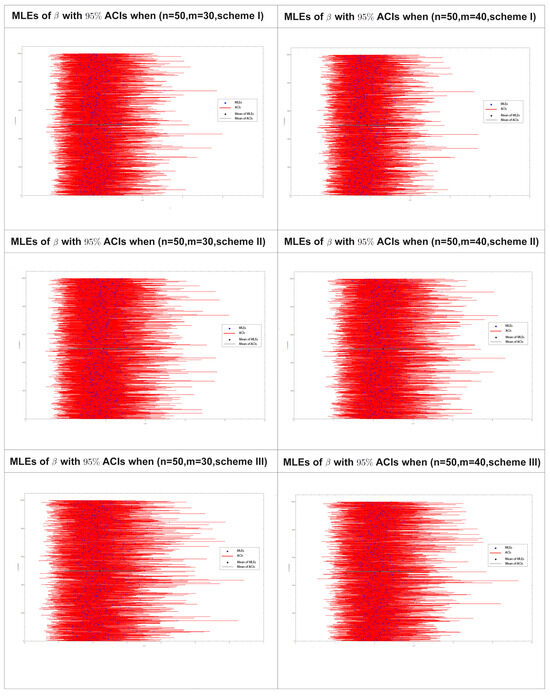

Figure 8 displays the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained using the maximum likelihood estimation distribution of for 1000 progressively type-II censored samples obtained using various drawing schemes, as listed in Table 8 for samples sizes (50, 30) and (50, 40).

Figure 8.

ACIs of of 1000 Pro-II C samples in Table 8 for various drawing schemes.

From Table 8 and Figure 8 presented above, it is evident that a relationship exists between the effective size (m) and both the mean squared error (MSE) and confidence intervals (CI) for , particularly in the first and third schemes. As the effective sizes increase, there is a decrease in the MSEs and the CIs. This trend is not observed in the second scheme.

Table 9 presents the estimates for obtained through maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian methods, along with the corresponding mean squared error (MSE) values and confidence intervals.

Table 9.

Estimates using MLE and Bayesian methods with their MSE and confidence intervals.

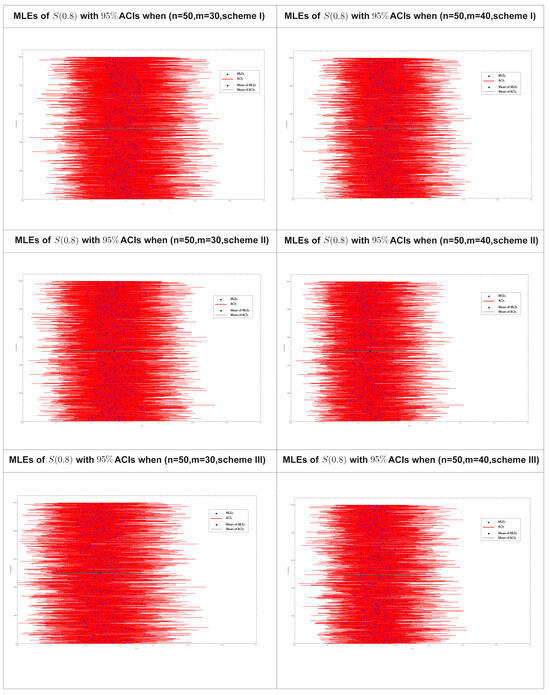

Figure 9 displays the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained using the maximum likelihood estimation distribution of for 1000 progressively type-II censored samples obtained using various drawing schemes, as listed in Table 9 for samples sizes and .

Figure 9.

ACIs of S(0.8) of 1000 Pro-II C samples in Table 9 for various drawing schemes.

From Table 9 and Figure 9 presented above, it is evident that a relationship exists between the effective size (m) and both the mean squared error (MSE) and confidence interval (CI) for , particularly in the first and third schemes. As the effective sizes increase, there is a decrease in the MSEs and the CIs. This trend is not observed in the second scheme.

Table 10 presents the estimates for obtained through maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian methods, along with the corresponding mean squared error (MSE) values and confidence intervals.

Table 10.

Estimates using MLE and Bayesian methods with their MSE and confidence intervals.

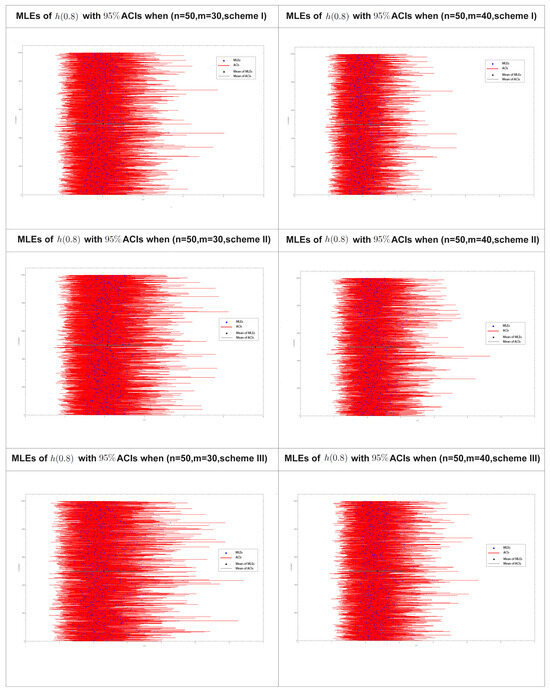

Figure 10 displays the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained using the maximum likelihood estimation distribution of for 1000 progressively type-II censored samples obtained using various drawing schemes, as listed in Table 10 for samples sizes and .

Figure 10.

ACIs of h(0.8) of 1000 Pro-II C samples in Table 10 for various drawing schemes.

From Table 10 and Figure 10 presented above, it is evident that a relationship exists between the effective size (m) and both the mean squared error (MSE) and confidence interval (CI) for , particularly in the first and third schemes. As the effective sizes increase, there is a decrease in the MSEs and the CIs. This trend is not observed in the second scheme.

8. Results and Discussion

In this section, some of the results obtained in Section 6 are analyzed, where different progressive schemes were applied utilizing two actual datasets to derive appropriate estimator values for Pro-II C samples and then compared with some previous studies. For Dataset I, the estimator values were determined for various progressive schemes under the condition of failure units. Notably, suitable estimator values were achieved when employing the scheme , where the estimation results were close to the complete data results using the maximum likelihood method. Furthermore, the boot-t approach had better results than the boot-p method in most cases, and is suggested on this basis. For Bayesian approach, we set the hyperparameter values to 0.0003, which is very small, making the prior distribution variance large. Because the variance of the gamma distribution is , j = 1,2, we can say that the prior belief regarding the unknown parameters is non-informative. For dataset II, the estimator values were computed for various progressive schemes in the case of failure units and appropriate estimator values were obtained when the scheme was equal to . In this case, the estimation results were close to the complete data results when using the maximum likelihood method. For the boot-t and boot-p methods, the boot-t results were better in most progressive schemes, although the results were not good for representing the complete data. In addition, we again set the hyperparameters to the very small value of 0.0003. In scheme , the Bayes results were better than those of other methods. For both datasets, it is important to emphasize that the schemes were selected randomly in instances of unit failure, which may have led to variations in the results. Therefore, we have documented the failed units for the two most effective schemes in datasets I and II in Section 6.

Finally, we discuss some of the results obtained in Section 7. From Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 presented in Section 7, it is evident that a relationship exists between the effective size (m) and mean squared error (MSE), along with the confidence interval (CI) for the estimates, particularly in the first and third schemes. As the effective sizes increase, there is a decrease in the MSEs and the CIs. This trend is not observed in the second scheme. In addition, it is apparent that Bayesian estimation produces the best results when utilizing the LINEX function with a value of c = 2, and that the confidence intervals with the Bayesian approach are smaller and less likely to contain parameter values estimated by a different estimation method.

9. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper is to study various approaches for estimating the parameters of the modified Fréchet-exponential distribution for Pro-II C samples and to suggesting the best progressive scheme. Several different estimation techniques are addressed and a simulation is carried to compare the proposed progressive schemes with the maximum likelihood and Bayes methods in the presence of two loss functions (SEL and LINEX). It is observed that the values of the estimators derived from the two methods are very similar, indicating the relative efficiency of the estimator. The most effective Bayesian methodology, utilizing an asymmetric loss function referred to as the LINEX loss function with a parameter set to (), exhibits enhanced efficacy. Furthermore, the credible intervals generated by the Bayesian method exhibit shorter length compared to the asymptotic confidence intervals derived using the maximum likelihood estimation method.

The significance of Pro-II C samples resides in their application within various progressive schemes that involve the withdrawal of specific sample units upon the failure of an element. From this perspective, we aspire to further investigate these samples by applying the same two schemes that previously demonstrated positive outcomes with other distributions utilizing the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach. Additionally, we intend to explore diverse estimation techniques, including the expectation-maximization algorithm, maximum spacing estimation, and Bayesian methods incorporating alternative loss functions such as the weighted absolute error loss function and quantile loss function.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.F.; Methodology, M.E.B. and D.A.R.; Software, O.S.B.; Validation, D.A.R.; Formal analysis, M.M.H., A.T.F. and D.A.R.; Investigation, M.E.B. and D.A.R.; Resources, A.T.F.; Data curation, M.M.H.; Writing—original draft, M.E.B. and D.A.R.; Writing—review and editing, D.A.R. and A.T.F.; Funding acquisition, M.E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Project Number (RSPD2024R1004).

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2024R1004), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- This code was executed using Wolfram Mathematica software, version 11.3, to find the parameters of the MFE distribution for progressive type-II censored sample.

- complete-data = {0.1, 0.33, 0.44, 0.56, 0.59, 0.72, 0.74, 0.77, 0.92, 0.93, 0.96, 1, 1, 1.02, 1.05, 1.07, 1.08, 1.08, 1.08, 1.09, 1.12, 1.13, 1.15, 1.16, 1.2, 1.21, 1.22, 1.22, 1.24, 1.3, 1.34, 1.36, 1.39, 1.44, 1.46, 1.53, 1.59, 1.6, 1.63, 1.63, 1.68, 1.71, 1.72, 1.76, 1.83, 1.95, 1.96, 1.97, 2.02, 2.13, 2.15, 2.16, 2.22, 2.3, 2.31, 2.4, 2.45, 2.51, 2.53, 2.54, 2.54, 2.78, 2.93, 3.27, 3.42, 3.47, 3.61, 4.02, 4.32, 4.58, 5.55, 7};

- x = {0.1, 0.33, 0.44, 0.56, 0.59, 0.72, 0.74, 0.77, 0.92, 0.93, 1, 1, 1.02, 1.05, 1.08, 1.08, 1.09, 1.59, 1.95, 2.13, 2.31, 2.78}

- n = Length[complete-data]; m = Length[x];

- R = {10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 10, 10, 10, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}

- L = Log[]

- ML = FindRoot[{ L == 0, L == 0 }, {{, 4}, {, 1}}];

- mu = /. ML;

- beta = /. ML;

- t = 0.5;

- Sur[ _, _ ] := Divide[(E^-1) - (E^-(1 - E^(-*t))^, (E^-1) - 1];

- Haz[_, _ ] := Divide[(**(E^((-*t) - (1 - E^(-*t))^))*((1 - E^(-*t))^(-1))), (E^-(1 - E^(-*t))^) - (E^-1)];

- S = Sur[mu, beta];

- H = Haz[mu, beta];

- {mu, beta, S, H}

References

- Klein, J.P.; Moeschberger, M.L. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 1230. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, J. Bayesian Computation with R; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwala, R.; Balakrishnan, N. Some properties of progressive censored order statistics from arbitrary and uniform distributions with applications to inference and simulation. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1998, 70, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yu, J.; Gui, W. Goodness-of-fit test for exponentiality based on spacings for general progressive Type-II censored data. J. Appl. Stat. 2022, 49, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairamov, I.; Eryılmaz, S. Spacings, exceedances and concomitants in progressive type II censoring scheme. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2006, 136, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, G.C.; Mazzanti, G.; Cacciari, M.; Fothergill, J.C. Optimum estimators for the Weibull distribution from censored test. data. Progressively-censored tests [breakdown statistics]. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 1998, 5, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.K.; Yang, C.; Yuen, H.K. Statistical analysis of Weibull distributed lifetime data under Type II progressive censoring with binomial removals. J. Appl. Stat. 2000, 27, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, E.H.; Ramadan, D.A.; Alqifari, H.N.; El-Desouky, B.S. Bayesian Inference for Inverse Power Exponentiated Pareto Distribution Using Progressive Type-II Censoring with Application to Flood-Level Data Analysis. Symmetry 2024, 16, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzaridah, M.M.; Ramadan, D.A.; El-Desouky, B.S. Estimation of Some Lifetime Parameters of Flexible Reduced Logarithmic-Inverse Lomax Distribution under Progressive Type-II Censored Data. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 1690458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwa, R.A.E.W.; Sadk, S.W.; Radwan, T. Estimation of Marshall–Olkin Extended Generalized Extreme Value Distribution Parameters under Progressive Type-II Censoring by Using a Genetic Algorithm. Symmetry 2024, 16, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gui, W. Statistical inference of the generalized inverted exponential distribution under joint progressively type-II censoring. Entropy 2022, 24, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasaballah, M.M.; Tashkandy, Y.A.; Bakr, M.E.; Balogun, O.S.; Ramadan, D.A. Classical and Bayesian inference of inverted modified Lindley distribution based on progressive type-II censoring for modeling engineering data. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 035021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, D.A.; Tashkandy, Y.A.; Bakr, M.E.; Balogun, O.S.; Hasaballah, M.M. Analysis of Marshall–Olkin extended Gumbel type-II distribution under progressive type-II censoring with applications. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 055137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, A.T.; Ramadan, D.A.; El-Desouky, B.S. Statistical Inference of Modified Frechet–Exponential Distribution with Applications to Real-Life Data. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2023, 17, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkedal, T. Acquisition of Resistance in Guinea Pies infected with Different Doses of Virulent Tubercle Bacilli. Am. J. Hyg. 1960, 72, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.T.; Wang, J. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 476. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E.A. Estimation of some lifetime parameters of generalized Gompertz distribution under progressively type-II censored data. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 5567–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, J.F. Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap and Other Resampling Plans; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. Theoretical comparison of bootstrap confidence intervals. Ann. Stat. 1988, 16, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Sandhu, R.A. Best linear unbiased and maximum likelihood estimation for exponential distributions under general progressive type-II censored samples. SankhyĀ Indian J. Stat. Ser. 1996, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Amir-Ahmadi, P.; Matthes, C.; Wang, M.C. Choosing prior hyperparameters: With applications to time-varying parameter models. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2020, 38, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).