Verifiable (2, n) Image Secret Sharing Scheme Using Sudoku Matrix

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sudoku Matrix

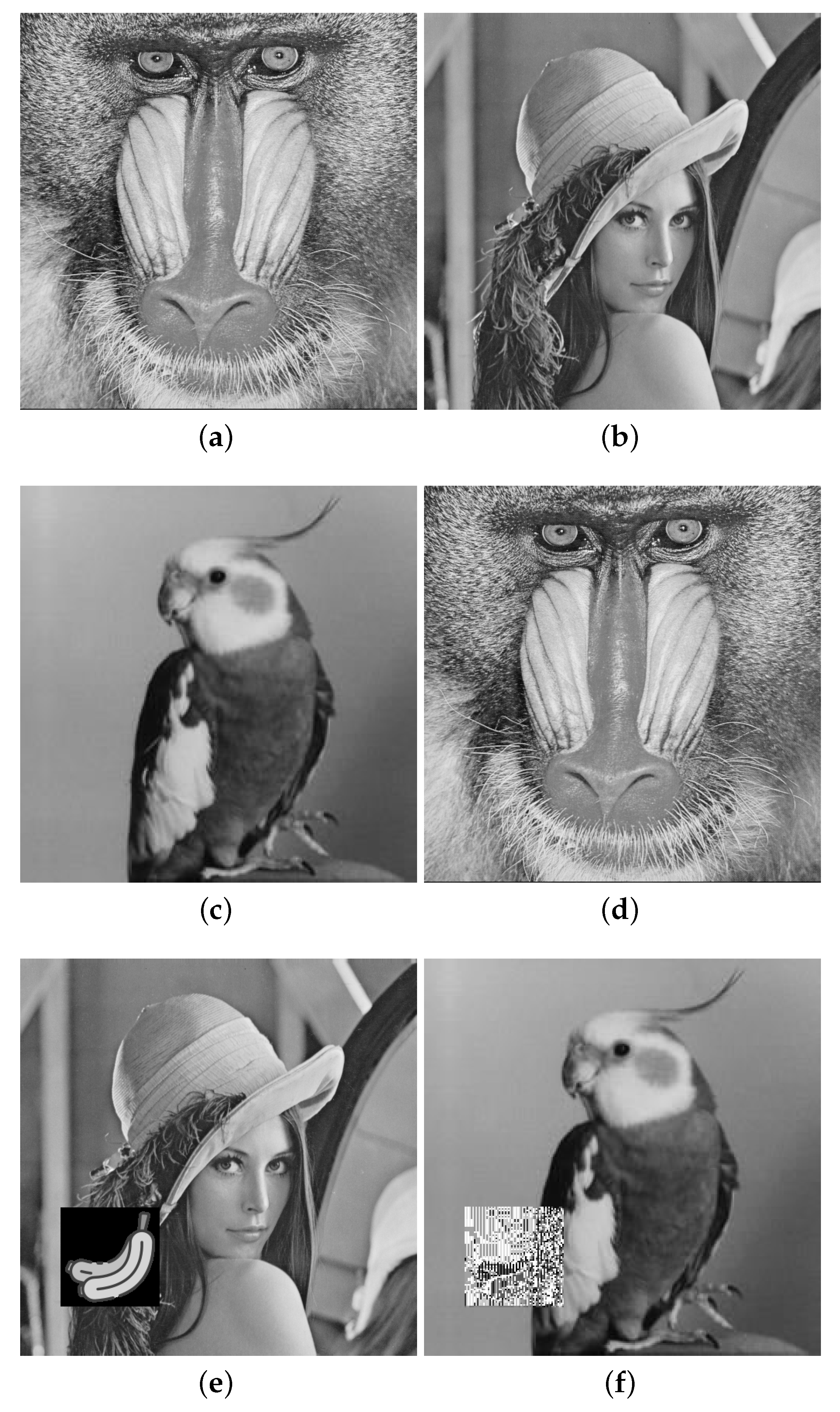

3. Research Methods

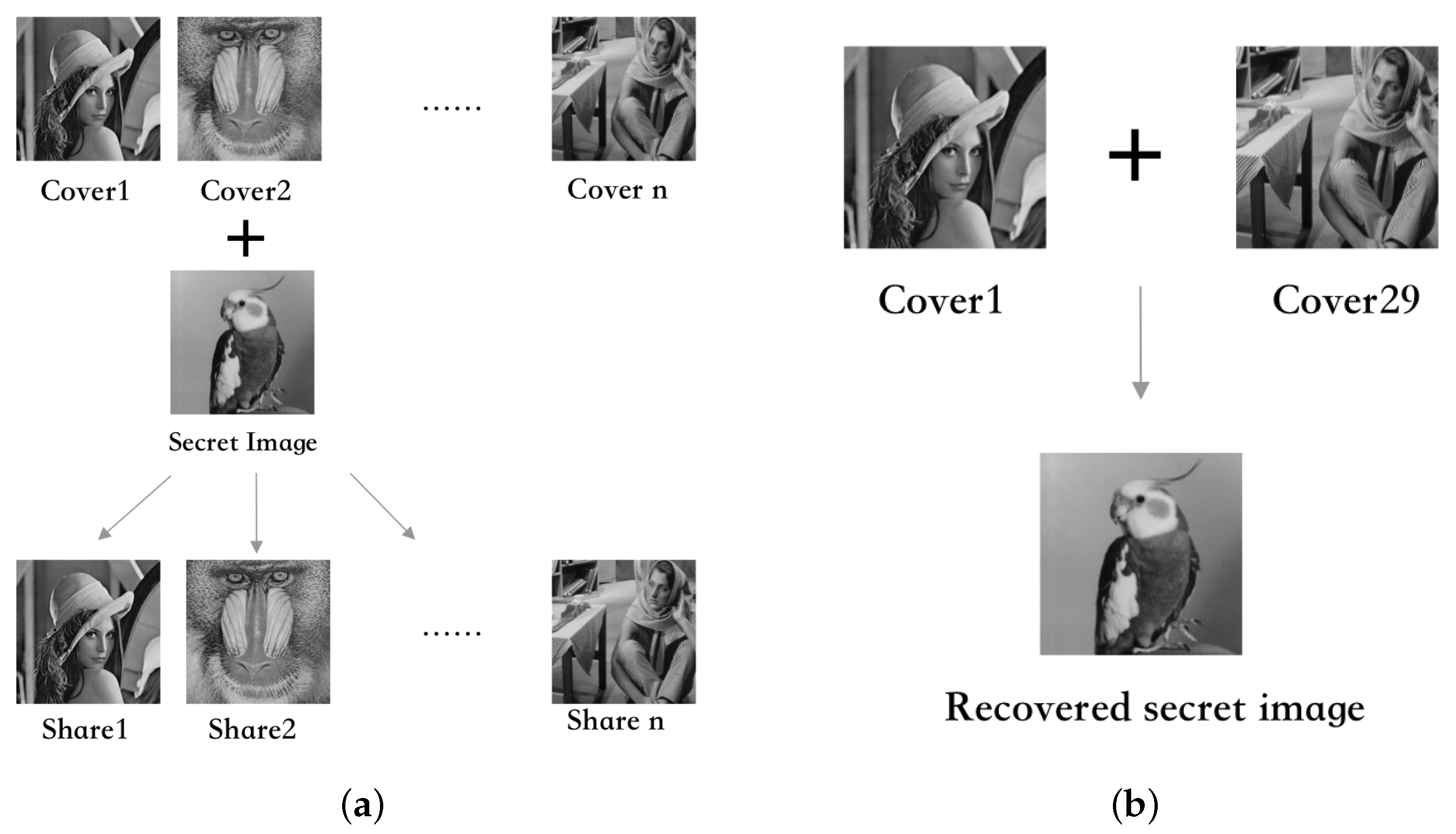

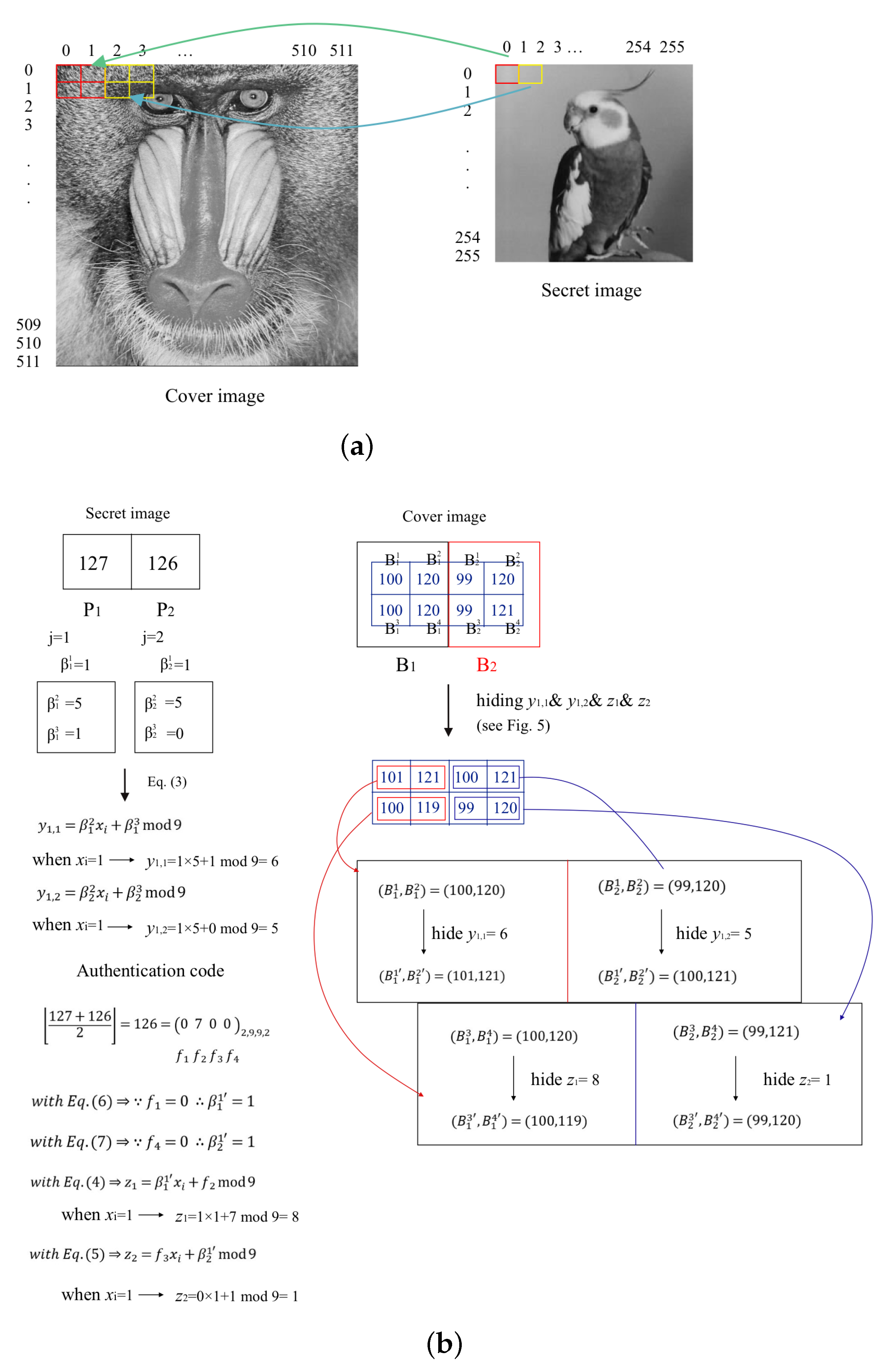

3.1. The Procedure of Hiding Secret Image and Authentication Codes to Cover Images

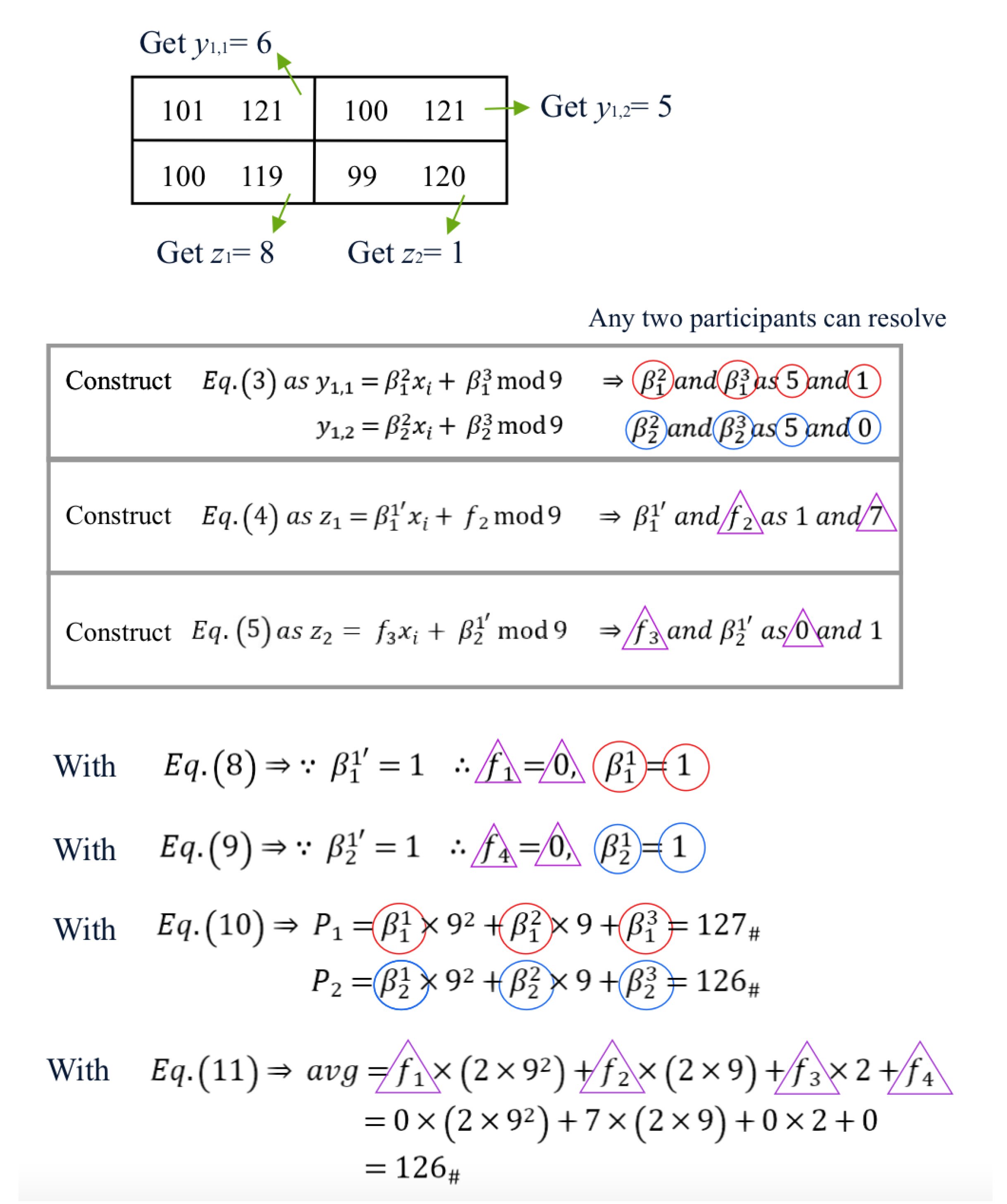

3.2. The Procedure of Secret Image Reconstruction and Authentication

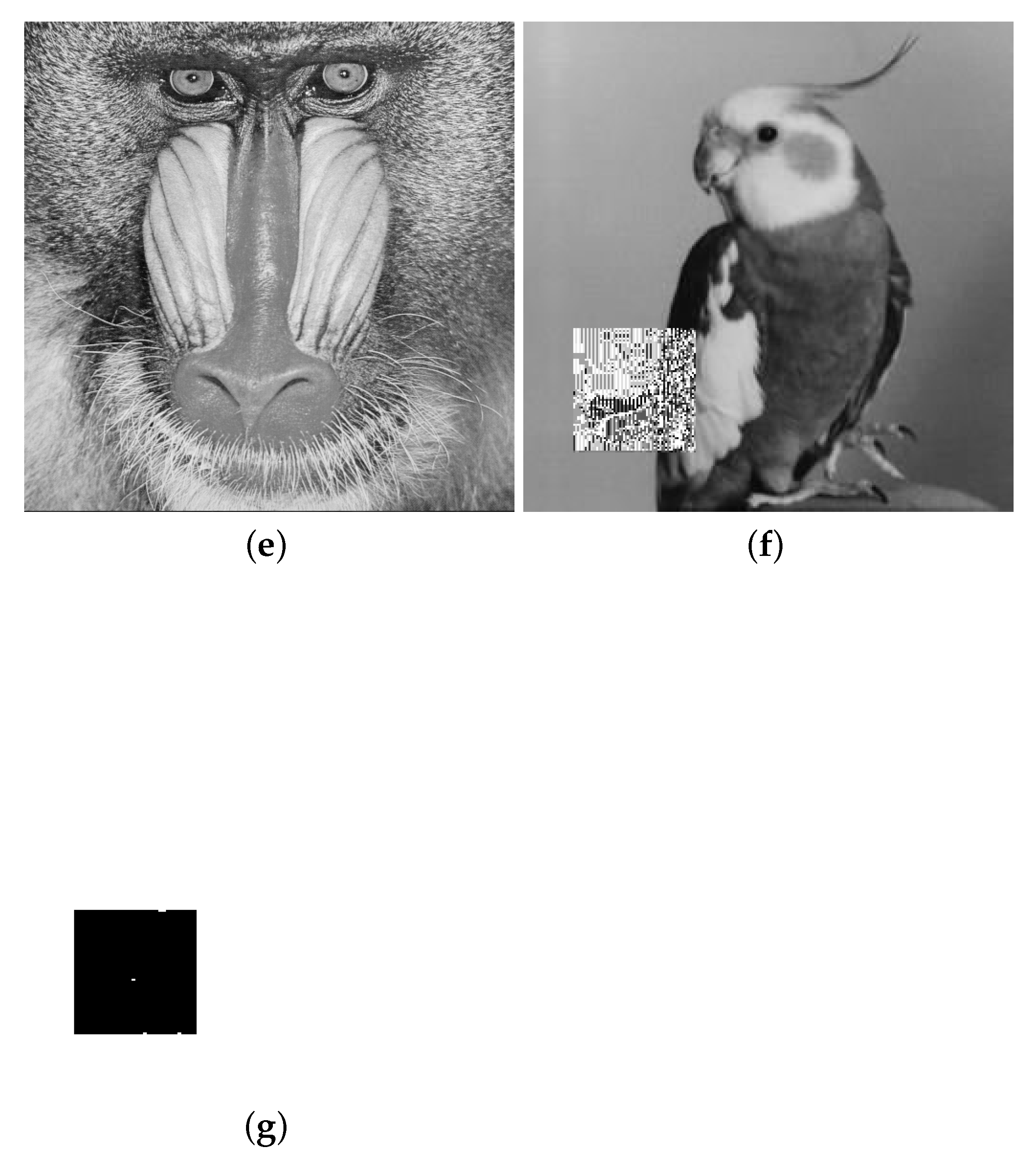

4. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Xiao, D.; Mou, H.; Lu, D.; Peng, M. A compressive sensing based image encryption and compression algorithm with identity authentication and blind signcryption. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 211676–211690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Watanabe, Y. Visual secret sharing schemes encrypting multiple images. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Du, L.; Wei, X.; Meng, D.; Guo, X. High capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images by patch-level sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2015, 46, 1132–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Chang, C.C. High-capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images based on extended run-length coding and block-based MSB plane rearrangement. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 58, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Shiu, C.W.; Horng, G. Encrypted signal-based reversible data hiding with public key cryptosystem. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2014, 25, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Lin, P.Y.; Wu, H.P.; Chen, S.H. Joint hamming coding for high capacity lossless image encryption and embedding scheme. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Chen, T.S.; Wu, H.Y. An improved reversible data hiding in encrypted images using side match. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2012, 19, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Huang, J.; Shi, Y.Q. New framework for reversible data hiding in encrypted domain. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2016, 11, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Shu, C. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images based on absolute mean difference of multiple neighboring pixels. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2015, 28, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Yu, N.; Li, F. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images by reserving room before encryption. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2013, 8, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puteaux, P.; Puech, W. An efficient MSB prediction-based method for high-capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images based on progressive recovery. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2016, 23, 1672–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Reversible data hiding in encrypted JPEG bitstream. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2014, 16, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, X. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images with distributed source encoding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2015, 26, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, W. High-capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images by prediction error. Signal Process. 2014, 104, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, R. Separable and error-free reversible data hiding in encrypted images. Signal Process. 2016, 123, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Zhou, Y. Binary-block embedding for reversible data hiding in encrypted images. Signal Process. 2017, 133, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Zhou, Y. Separable and reversible data hiding in encrypted images using parametric binary tree labeling. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Abel, A.; Tang, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, B. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images based on multi-level encryption and block histogram modification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 3899–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images based on multi-MSB prediction and Huffman coding. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 22, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Reversible data hiding in encrypted image. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2011, 18, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Separable reversible data hiding in encrypted image. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2012, 7, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, N. Reversibility improved data hiding in encrypted images. Signal Process. 2014, 94, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qian, Z.; Feng, G.; Ren, Y. Efficient reversible data hiding in encrypted images. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2014, 25, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Long, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, H. Lossless and reversible data hiding in encrypted images with public-key cryptography. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2015, 26, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Hou, D.; Yu, N. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images by reversible image transformation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2016, 18, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Li, D.; Hu, D.; Ye, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, J. Lossless data hiding algorithm for encrypted images with high capacity. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2016, 75, 13765–13778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, W.; Dong, L.; Liu, X.; Au, O.C.; Tang, Y.Y. Secure reversible image data hiding over encrypted domain via key modulation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2016, 26, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, A. How to share a secret. Commun. ACM 1979, 22, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Kieu, T.D.; Chou, Y.C. Reversible data hiding scheme using two steganographic images. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2007–2007 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 30 October–2 November 2007; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, P.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, M. A sudoku-based secret image sharing scheme with reversibility. J. Commun. 2010, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, L.; Song, X. Reversible image secret sharing. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 3848–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, C.C. A turtle shell-based visual secret sharing scheme with reversibility and authentication. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 25295–25310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Horng, J.H.; Chang, C.C. An authenticatable (2, 3) secret sharing scheme using meaningful share images based on hybrid fractal matrix. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50112–50125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Horng, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Chang, C.C. A reversible secret image sharing scheme based on stick insect matrix. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 130405–130416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, C.C.; Huang, P.C. Security protection using two different image shadows with authentication. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2019, 16, 1914–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Horng, J.H.; Shih, C.S.; Chang, C.C. A maze matrix-based secret image sharing scheme with cheater detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Chang, C.C.; He, M.X.; Lin, C.C. A lightweight authenticable visual secret sharing scheme based on turtle shell structure matrix. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Chang, C.C. LSB-based high-capacity data embedding scheme for digital images. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2009, 5, 4283–4289. [Google Scholar]

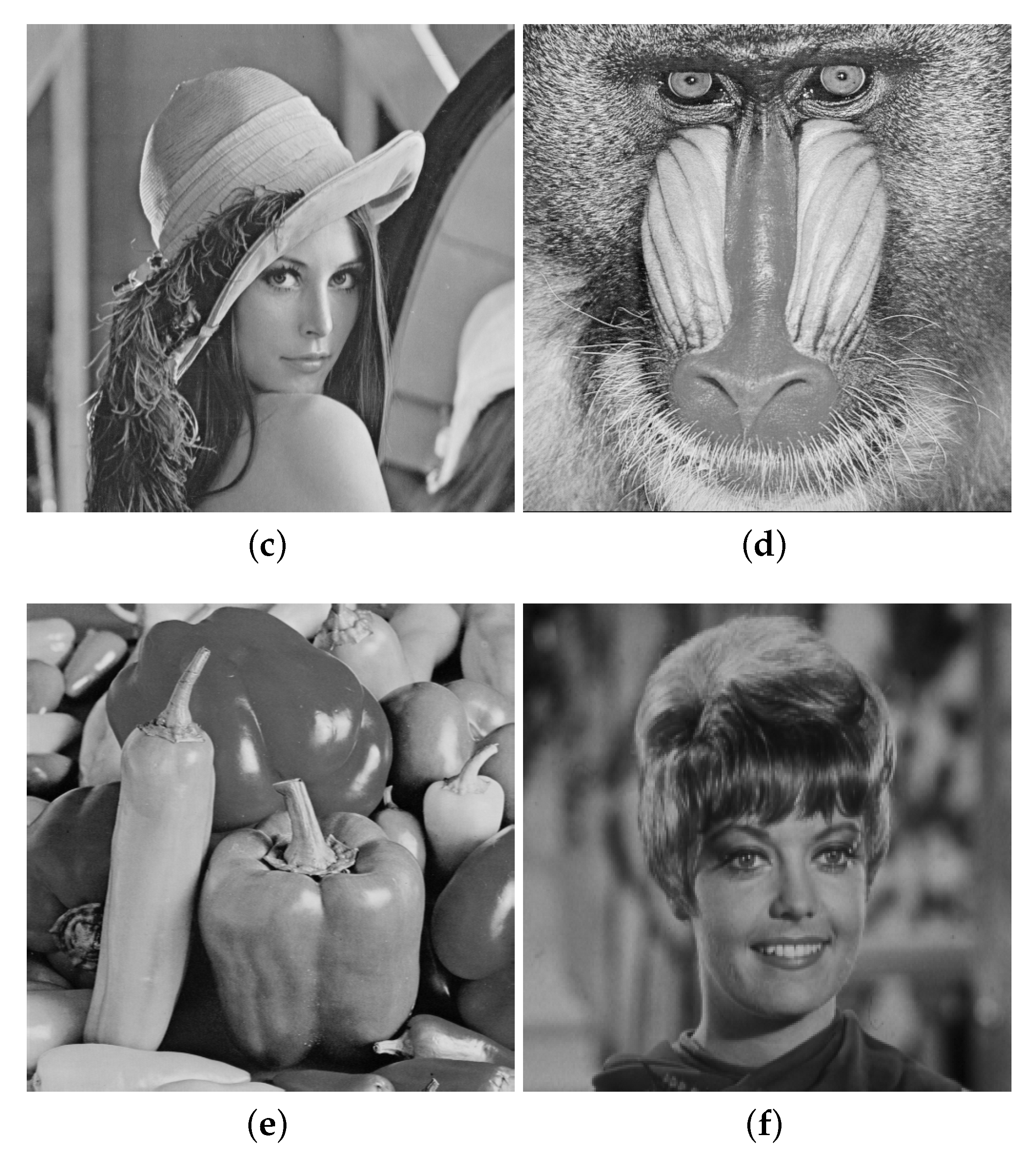

| Secret Images | Lena | Baboon | Pepper | Zelda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | |

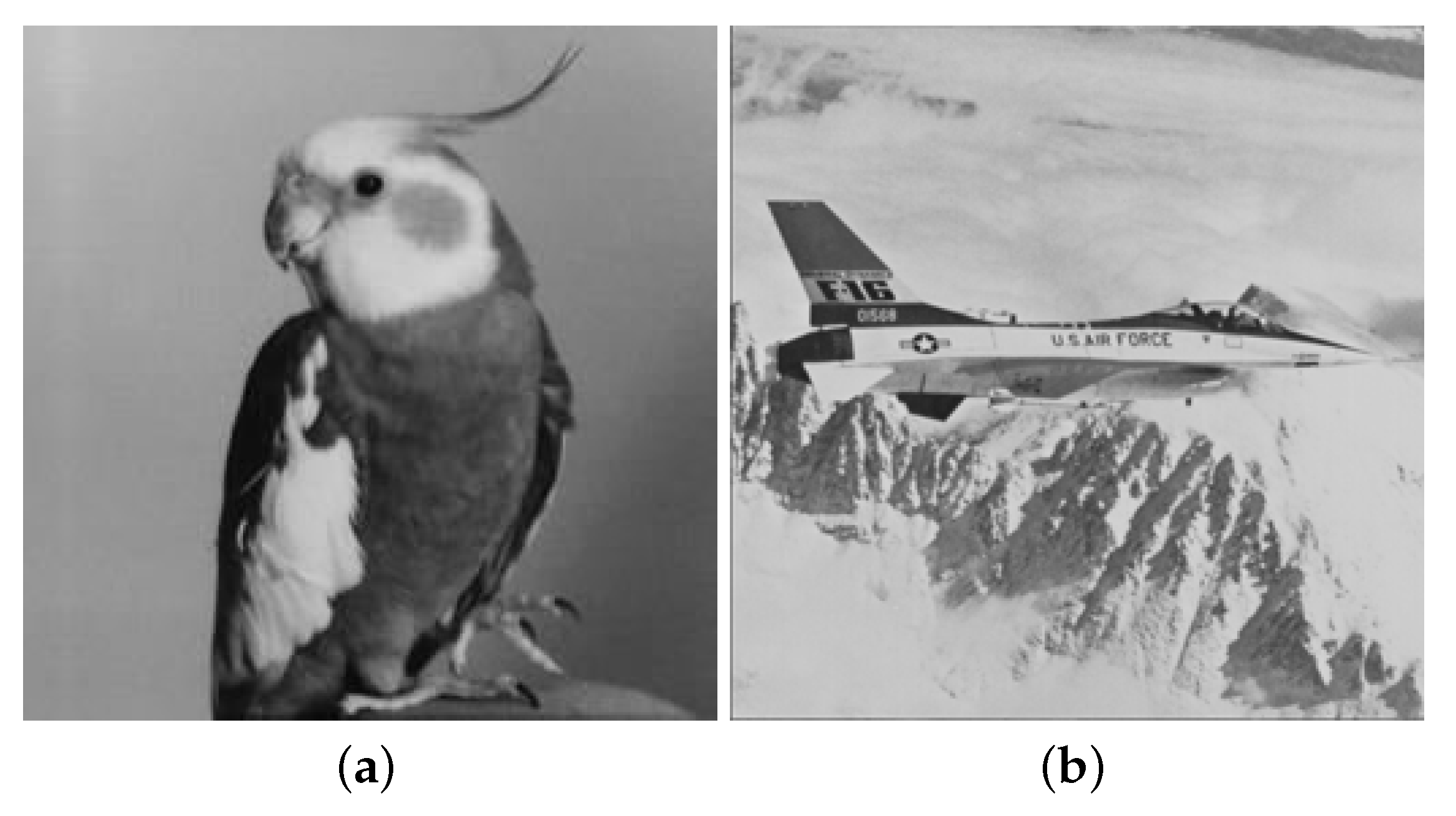

| Bird | 49.88 | 0.993 | 49.88 | 0.998 | 49.88 | 0.993 | 49.89 | 0.990 |

| Jet(F16) | 49.88 | 0.994 | 49.89 | 0.998 | 49.88 | 0.993 | 49.88 | 0.990 |

| Features | Gao et al.’s Scheme [35] | Li et al.’s Scheme [38] | Liu et al.’s Scheme [33] | Liu et al.’s Scheme [36] | Gao et al.’s Scheme [34] | Proposed Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaningful shares | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Reversibility | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | Yes |

| Different cover images | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (k,n)-SIS | (2,2)-SIS | (3,3)-SIS | (2,2)-SIS | (2,2)-SIS | (2,3)-SIS | (2, n)-SIS |

| Fault tolerance | Yes | - | - | - | Yes | Yes |

| Average PSNR | 32.96 | 49.07 | 48.72 | 41.71 | 40.41 | 49.88 |

| Embedding capacity (bits) | 786,432 | 624,215 | 524,288 | 785,525 | 1,310,720 | 786,432 |

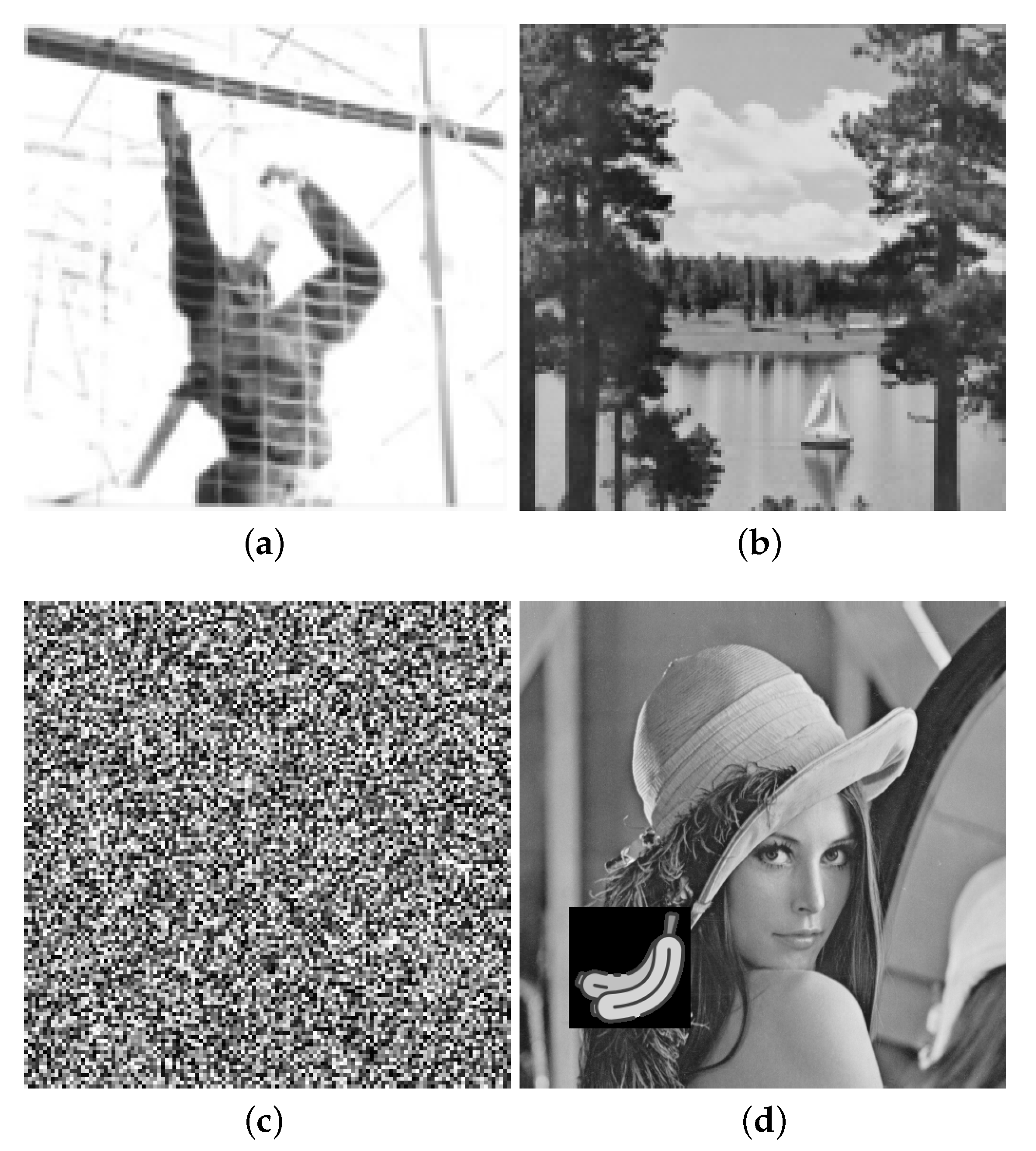

| Tampered Image | Gao et al.’s Scheme [34] | Proposed Scheme | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Special image | 0.684 | 0.942 | 0.997 |

| Standard image | 0.084 | 0.834 | 0.995 |

| Uniform noise | 0.097 | 0.836 | 0.995 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Chiang, M.-H.; Chen, S.-H. Verifiable (2, n) Image Secret Sharing Scheme Using Sudoku Matrix. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14071445

Chen Y-H, Lee J-Y, Chiang M-H, Chen S-H. Verifiable (2, n) Image Secret Sharing Scheme Using Sudoku Matrix. Symmetry. 2022; 14(7):1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14071445

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yi-Hui, Jia-Ye Lee, Min-Hsien Chiang, and Shih-Hsin Chen. 2022. "Verifiable (2, n) Image Secret Sharing Scheme Using Sudoku Matrix" Symmetry 14, no. 7: 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14071445

APA StyleChen, Y.-H., Lee, J.-Y., Chiang, M.-H., & Chen, S.-H. (2022). Verifiable (2, n) Image Secret Sharing Scheme Using Sudoku Matrix. Symmetry, 14(7), 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14071445