Abstract

Quantum cryptography is a well-stated field within quantum applications where quantum information is used to set secure communications, authentication, and secret keys. Now used in quantum devices with those purposes, particularly Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), which proposes a secret key between two parties free of effective eavesdropping, at least at a higher level than classical cryptography. The best-known quantum protocol to securely share a secret key is the BB84 one. Other protocols have been proposed as adaptations of it. Most of them are based on the quantum indeterminacy for non-orthogonal quantum states. Their security is commonly based on the large length of the key. In the current work, a BB84-like procedure for QKD based on double quantum teleportation allows the sharing of the key statement using several parties. Thus, the quantum bits of information are assembled among three parties via entanglement, instead of travelling through a unique quantum channel as in the traditional protocol. Asymmetry in the double teleportation plus post-measurement retains the secrecy in the process. Despite requiring more complex control and resources, the procedure dramatically reduces the probability of success for an eavesdropper under individual attacks, because of the ignorance of the processing times in the procedure. Quantum Bit Error Rate remains in the acceptable threshold and it becomes configurable. The article depicts the double quantum teleportation procedure, the associated control to introduce the QKD scheme, the analysis of individual attacks performed by an eavesdropper, and a brief comparison with other protocols.

1. Introduction

With the development of quantum applications, particularly quantum cryptography [1], new cryptosystems intended to be unconditionally secure are being developed. Such cryptosystems are commonly composed of a sender and a receiver assuming to share an Encryption and a Decryption key [2]. Then, a message can be encrypted and transmitted from the sender’s end to the receiver’s end. Along the way, an eavesdropper can try to steal the key intended to be transmitted between them. For instance, experimental implementations are led using imperfect photon detectors, thus allowing the loss of some photons [3] and allowing an intruder to tamper these imperfect devices to obtain advantages against the security of the protocol [4,5]. Due to this feasibility, it is necessary to strengthen the security in all cryptosystems.

With this purpose, new research aiming to obtain better unbreakable ways of key distribution between two parties has been conducted. Such development has boosted technology implementing Quantum Key Distribution (QKD). There, two entities (sender and receiver) can communicate securely to set codification keys. The peculiarity of quantum cryptography is the use of fundamental aspects of quantum mechanics such as the uncertainty principle [6], entanglement [7], and the quantum measurement theory [8] to provide a set of constraints on the communication channel to make it safer [9]. The generation of this quantum key can be distributed through many protocols developed for this purpose [10]. Some existing QKD protocols include BB84 [11], B92 [12], SARG04 [13], and E91 [14].

In this sense, quantum cryptography has become a leading development for the secure transmission of data [15]. After the last-mentioned QKD protocols, quantum cryptography has been refining its methods and complexity to keep off quantum hacking as a counterpart [16]. Thus, post-quantum cryptography pursues cryptography algorithms being secure against cryptanalytic attacks performed by quantum computers [17]. Otherwise, QKD can be made unconditionally secure over arbitrarily long distances against attacks by an eavesdropper [18]. Thus, quantum cryptography is requiring more complex procedures including quantum processing to enhance security.

In another trend, for the development of communications, quantum teleportation has played a central role in communication enhancements. Various approaches seeking experimental implementations of such algorithms soon emerged [19,20]. Since then, the great importance of the development of quantum teleportation has boosted applications in quantum communication to a large extent. Some of them include the creation of quantum networks [21], cryptography applications regarding quantum computing systems [22], settlement of photonic quantum computing [23], and particularly teleportation-based quantum cryptography protocols [24] as complementary scaffolding procedures improving its efficiency and security.

Improvements in the quality of teleportation involve new approaches. Some of them for long-distance quantum teleportation with the use of a fiber-delayed Bell state measurement (BSM) [25] and others using optical fiber to avoid using large-aperture optics and other complex techniques [26,27]. Teleportation is being combined with quantum strategies as a causal order [28] to remove some underlying noisy effects. Recently, an analysis for a double teleportation process for the same input state has been presented in [29,30]. In such a scenario, one main party (Alice) has prepared the input state and then shared two entangled resources with another two parties (here called Bob and Bob) keeping one qubit of each pair. A central resource, in principle accessible for the three parties, works as a control to decide who of the Bob’s will receive the teleported state. With such a scheme, cryptography protocols can be performed to set secure authentication methods [30].

This work presents a BB84-like shared protocol exploiting double teleportation to generate controlled correlated information to set a quantum key between two final parties. Despite BB84 being one of the first quantum cryptography protocols, it has remained as a heraldic one. Nowadays, variations of such protocol are still proposed to improve some of its features, thus remaining valid in the contemporary literature. While the traditional BB84 protocol employs a single quantum channel to transmit the key in the form of two-level states first settled on an unknown basis for the receiver, in the current proposal, non-local features of double teleportation combined with asymmetric post-processing allow us to assemble this key during it. It reduces the action time for an eavesdropper by reducing his rate of success while the key has still not been assembled. Some outstanding outcomes in this procedure are:

- A notable rate of success for the coincident basis scenario between the sender and the receiver closer to the ideal case in the original BB84 protocol;

- A dramatic reduction of success for an eavesdropper under individual attacks for the undetected scenario during a reconciliation step;

- A practical reduced time of action for an eavesdropper due to the non-local properties of the key assembling and the absence of a physical quantum channel;

- A configurable setup to adjust some quantitative working features in the procedure as the eavesdropper success ratio or the Quantum Bit Error Rate (QBER).

The structure of the article is as follows. The second section introduces the protocol in the contemporary scenario of quantum cryptography. The third section develops the main lines to perform the double teleportation and the necessary post-processing for the task, together with some remarks about its non-locality features. Then, the control of such asymmetric post-processing to distribute quantum keys between those two parties is presented in the fourth section, setting the scenario for QKD. The fifth section first discusses the contemporary validity of the BB84 protocol in the literature; then, it properly analyses the QKD protocol departing from the previous development, as well as the inclusion of an eavesdropper in the process presented to quantify the vulnerability under individual attacks in terms of its success and detection. The sixth section includes brief discussions about benchmarking for the procedure, possible effects related to decoherence, and fidelity. Conclusions are settled in the last section.

2. Introductory Remarks for Contemporary Post-Quantum Cryptography

Quantum cryptography is the science that pretends to exploit any quantum mechanical feature to perform cryptography tasks, which means methods of encryption naturally using the properties of quantum mechanics to secure and transmit data without hacking. The economy in quantum cryptography has been pursued through the main original developments despite the contemporary technology at the time those works were published. Possibly, QKD is the most important contribution to quantum cryptography by promoting the fusion of classical and quantum approaches, setting a natural incubator in which to develop the field.

The first quantum protocol for QKD was the BB84 one [11] based on quantum conjugate variables. Such protocol states a procedure to state a key in the form of a chain of zeroes and ones without a direct transmission from the sender to the receiver. Instead, the key is codified through a series of quantum resources randomly prepared by the sender on one from two orthogonal agreed bases. Then, they are stochastically found by the receiver through random measurements on such bases. In the end, the bases used are shared by both parts to conserve the identical outcomes when the bases meet. Such a procedure allows us to detect eavesdropping when it intermediately alters the coincident bases and outcomes through a different basis measurement.

Thus, QKD protocols, as that mentioned before, first used quantum correlations to set a quantum key between two parties (another one similar is the B92 [12]). Soon, other protocols appeared exploiting the statistical nature of quantum systems involved, as in the SARG04 [13]. While alternative protocols such as the E91 [14] used entanglement pairs more than just the quantum nature of states in terms of orthogonal basis in a symmetrical treatment of information to construct the key together. Moreover, Quantum Key Agreement (QKA) protocols [31] introduced a shared decision generation for the key.

When quantum computers are introduced to break quantum codes of such developments, the scenario was moved to secure protocols including quantum computer-based attacks. It has raised the post-quantum cryptography terrain to set secure protocols against quantum computer attacks. Despite this, the roadmap is unclear because some of the most current classical symmetric cryptographic protocols are still considered to be relatively secure against quantum computer attacks [32], thus it is believed that classical approaches in theoretical cryptography could be combined with quantum cryptography trends [33].

The current development introduces some elements exploiting quantum processing together with extreme features of quantum information as double teleportation, non-local operations performed via entanglement, and controlled measurements by quantum machines. Some features of the protocol also combine QKA approaches. Thus, they allocate the current proposal in the terrain of post-quantum cryptography (or quantum-safe cryptography) to set a QKD procedure reducing the eavesdropper success.

Other technology concerns should be considered because of the growing complexity of the post-quantum protocols including more complex processing and finer theoretical cryptography considerations. Such aspects are similar to those premises considered in quantum processing: quality and reliability on state generation processes, development of coherent quantum gates to preserve their supposed quantum nature, and faithfully quantum measurement. Those aspects are remarked through the development.

3. Double Teleportation as Superposition and Parallel Post-Processing

Multiple teleportation exploits the quantum linearity to extend the traditional teleportation procedure to perform virtual transference of states and processing. In the end, global states could be recovered for concrete tasks. Quantum states obtained by multiple teleportation exhibit interesting non-local properties [29] and they could be used with cryptography purposes [30]. In this section, we will describe the process only for double teleportation (DT) with additional post-processing (PP). Then, in Section 4, we deal with the control problem (TC) to share and transfer concrete quantum states to be used for QKD purposes (QKD) in Section 5. To ease the reading, we first account in Table 1 for the key symbols (states, operators, and related key quantities) through the entire development.

Table 1.

States, Gates, and Parameters involved in the analysis through each step (DT, PP, TC, QKD) of the whole QKD protocol.

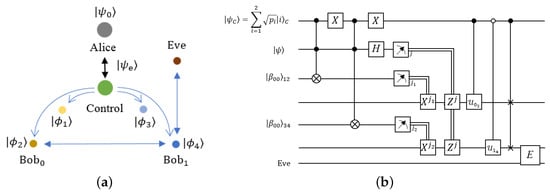

3.1. Double Teleportation Process as Superposition

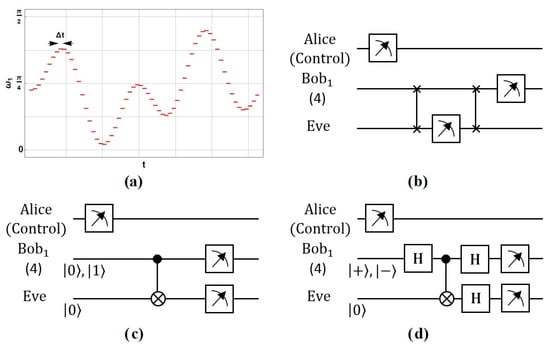

Figure 1a synthetically depicts the process followed for double teleportation immersed in the context of QKD. In the current section, we develop the double teleportation process as it was originally presented [29]. As it was stated, one party (Alice) generates secretly an arbitrary state (known or unknown) to then potentially transmit it in superposition by teleportation to other two parties (Bob and Bob). The presence of an eavesdropper (Eve) acting on Bob is possible, so it is shown in Figure 1a,b, but her action will be considered and depicted at the end. In this case, instead of the traditional algorithm, the process intends to virtually teleport such state to those two simultaneous receivers, Bob and Bob [29].

Figure 1.

(a) Three main parties performing double controlled teleportation with a central control accessible for all of them; a possible eavesdropper is present; (b) Quantum circuit representing the main elements of the double teleportation process.

The process begins with the main qubit to be teleported in possession of Alice, where . In this work, the Bell states will be written: . Then, a pair of Bell entangled resources are prepared to be shared with each one of both receivers to implement the teleportation process (subscripts state the numbering of the resources). In the process, a control state is required to rule the quantum transmission on a concrete receiver , with: . Thus, if control is settled in the state then is teleported to Bob, otherwise to Bob if the control is . Then, the global initial state being considered becomes:

Then, the following controlled gate is applied: , which is clearly unitary [29]. In fact, this gate is basically a pair of Toffoli gates each one followed by another:

Then, remarking that (there, X is the NOT gate), and considering that , the double teleportation process follows by applying a Hadamard gate on the qubit to be teleported, :

dropping the tensor products for the sake of simplicity, remarking that and , and expanding some Bell states to express it in terms of [29]. Clearly, those steps state an extension of the traditional teleportation algorithm [34] for qubits. Finally, performing measurements on the original qubit to teleportate, as well as the qubits 1 and 3 (being part of the entangled resources) with respective outcomes and , we get the un-normalized post-measurement state:

where if the exponent on an operator is zero, it implies that such operator is omitted. It is easy to notice that each one of the eight possible measurement outcomes occur with probability of . Thus, normalizing and finally, as a function of the outcomes, applying the generic correction ( are the Pauli operators), we obtain [29]:

where we dropped the states for the qubits 1 and 3, as well as the original qubit for the sake of simplicity. This state represents the virtual teleportation to both Bob’s. Figure 1b shows the quantum circuit of the process depicted, based on the traditional teleportation algorithm [34]. Black dots in the controlled operations are traditional controls , while white dots corresponds to negative controls: . The action of Eve is just indicative, we deal with the eavesdropping intervention below. In the next subsection, we will perform certain post-processing to introduce the necessary tasks to set QKD.

3.2. Post-Processing Following to Double Teleportation

In the last expression, each outcome still can be managed by the control state to perform different processing on each virtual teleported qubit. Applying the operator (see Figure 1b on the right in the form of a pair of controlled gates):

Such asymmetric post-processing following to the double teleportation will set the successful secrecy for the QKD procedure. Thus, by defining (with ) as the output of each processing , then we will get:

As a useful possibility for further applications, we consider the final transference of the state from Bob to Bob by applying a controlled to send the processed output state on the qubit 4: (see Figure 1b on the right).

Note operations and are few practical because qubits are far away from qubit 4. We show them in such last synthetic forms, but they can be equivalently achieved using additional entangled resources between Alice/Bob and Bob. The details about the equivalence of such processes are given in the Appendix A and Appendix B. There, related techniques required are delayed measurements [35] and quantum controlled measurements [36,37]. In any case, it gives the following state settled on the qubit 4 in possession of Bob:

disregarding the separable qubit 2. In addition, Alice will decide to measure the control state on an eligible orthogonal basis given by , with . It means, can be written as:

to ease the identification of the measurement outcomes in such basis. In the following, we will commonly drop the labels C for the control and 4 for the qubit 4, which now become clear from the development.

3.3. Entanglement and Non-Locality Activation

The double teleportation plus post-processing process depicted at this point has been previously analysed in terms of generation of non-local properties [29]. In fact, after of the measurement of the control state on the basis , a wide type of entangled states could be generated if each Bob introduces additional local resources. Using the concurrence as entanglement measurement, it was shown that they can range from separable states to maximally entangled ones. In addition, the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH) inequality has been used to demonstrate the non-locality activation through the involved quantity (there, is the correlation between the measurements ). This quantity reaches the Tsirelson’s bound in the process, indicating the non-locality activation. Such analysis dealt with the measurement basis settled by the operators and to get the correlations on a setup testing of the CHSH inequality. It means that the state transference depicted strongly undergoes through a non-local process generating non-locality correlations. Such non-local transference has been also demonstrated between a couple of semiconductor microcavities connected by optical fiber for solid-state physics [38,39] using geometric quantum discord and concurrence as main non-locality quantifiers. Despite the process presented in that article proposing entanglement to generate quantum states at distance, those works set a certain kind of alternative technology to share or generate quantum states in a second party using non-classical light.

3.4. Concrete Post-Processing and Information Transference via Post-Measurement

We will consider the asymmetric post-processing performed by Bob and Bob as:

characterized by the parameter . Thus, asymmetry is introduced by the differentiated parameter in each post-processing, together with the different value for the strength of the teleportation, and the control measurement. By expressing in its Bloch representation, in such scenario, the probabilities to get the measurement outcome of or becomes [30]:

where . Because , for such reason if , then the probability to get is one in any case. As we will see, we can use the previous process to generate and distribute quantum keys, if Alice works together with Bob as a central computer performing part of the processing, while Bob is an associated user.

4. Transference of Programmed Quantum States Using Double Teleportation

In the current section, we deal with the control problem for the transference to Bob of a programmed state prepared by Alice/Bob. The post-processing in (12) is stated to introduce a public and classical authentication fingerprint . Then, we will assume this fingerprint could be known as an extreme case by an eavesdropper to emphasize the quantum features of the procedure. Without such authentication, the remaining state exchange will not work [30]. In addition, as we will note in the procedure to be presented, an advantage is that the state being transferred does not exist until it becomes assembled by the collaboration of the involved parts.

4.1. Generation of Quantum States as a Collaboration among Three Parties

Following the discussion in the last section, by inserting explicitly the action of (12) on :

with . We note that if , it means such parameter takes one of the two possible values or . In such case, the last expression naturally states an orthogonal basis defined by the couple of vectors:

they could be selected through the initial election of on the Bloch sphere meridian containing the states and . It still leaves sufficient room to choose a quasi arbitrary state. Integrating those expressions in (11), we get:

For further applications, we will require certain coefficients of each pair in the previous expression become zero. It is only possible if , meaning that . Then, . In such case, the probabilities (13) and (14) for the measurements on the control state are:

4.2. General Notation for the Control of Post-Selection Problem

In the current subsection, we are interested in the post-selection by Alice/Bob of certain states as well as in the control and Bob systems. With that purpose, we develop a general notation to solve the problem. First, by defining:

then, clearly . In those terms, reads:

If then Alice/Bob pretends to control the post-selection of and , two conditions should be imposed. The first one is:

which post-selects one of for certain j. It could be solved by demanding:

Such a condition states a possible asymmetric treatment () to introduce the secrecy of the QKD procedure [29]. Such condition states an asymmetric treatment to introduce the secrecy of the QKD procedure because the transmitted state to Bob remains uncertain. It immediately implies the fulfilling of:

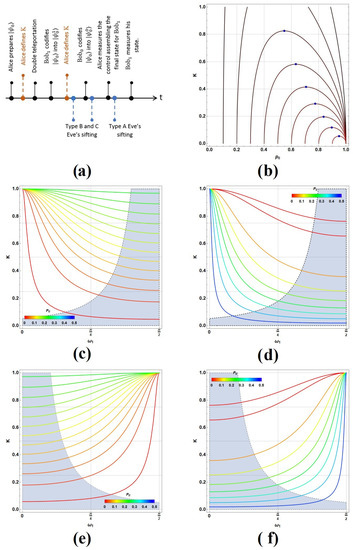

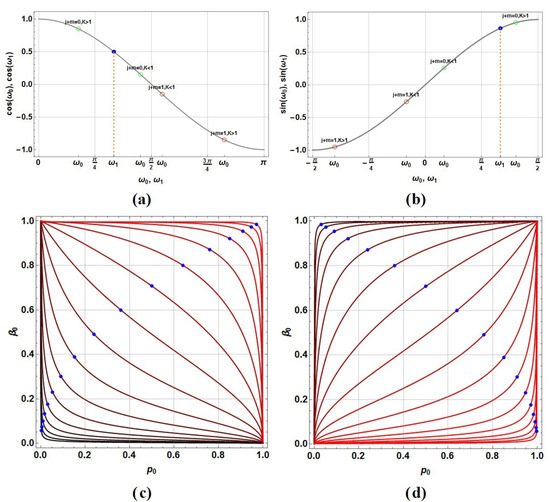

Equation (25) states the way to select when is first settled choosing certain value for K stating certain secret asymmetry in the election (together with , all those parameters under the control of Alice/Bob). Figure 2a,b show such process for and respectively (remembering that the selected state for Bob is ). If the restriction is settled (such condition it is not completely necessary but it eases some further expressions), upon the selection of , then could be selected as it is indicated by the green circles in both figures ( or ); otherwise, if , could be selected as in the red circles ( or ). There, we restrict for and for . Note in any case that will fulfill. Consequently, the election of K stated by (24) relates with . Those relations are shown in Figure 2c,d for and respectively. Each red curve corresponds to certain K value being selected. While , the darkest red curves show the lowest values for , and the lightest ones the largest values for .

Figure 2.

(a,b) Plots exhibiting the process of selection of departing from the selection of through the condition (25) for each case (left) or (right). (c,d) Possible values for the combination of upon the prior selection of K (each red curve) for each case (left) or (right); blue dots show the values of maximizing .

The second condition is obtained by substituting the first condition in the probability of success (13) or (14) for :

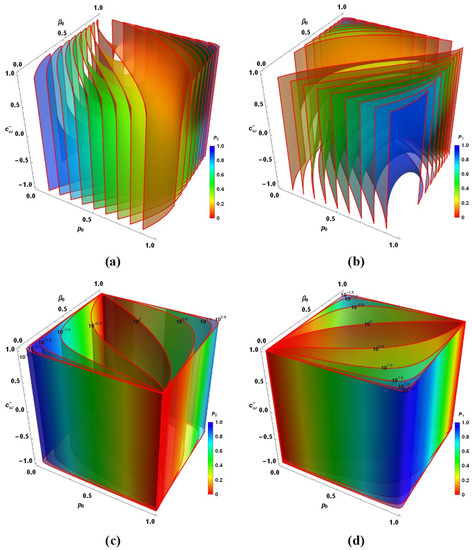

by choosing a high value for (ideally ). By defining , we note that depends from , and in general, as Figure 3 shows. Figure 3a,b show the contours on which become constant in agreement with the color scale on the right (for on the left and right respectively). Below, Figure 3c,d show the three dimensional version of Figure 2c,d with their K values shown in black in their top. In addition, each contour was additionally coloured in agreement with their value in each point of the space (from the reddest for to the bluest for , also in agreement with the color bar besides and with the previous plots). In fact, the solutions are first found by selecting K and then intersecting each lower plot with its corresponding upper plot (for the same j value). Despite, is not an independent parameter as the last intersection shows.

Figure 3.

(a,b) Contour plots of for respectively as function of , and . (c,d) Three-dimensional version of plots in Figure 2c,d, now including and coloured from red () to blue () in agreement with values through them for respectively.

4.3. Control Prescriptions for the Quantum State Transference

In fact, we can analyse in terms of and K (using the fact with ):

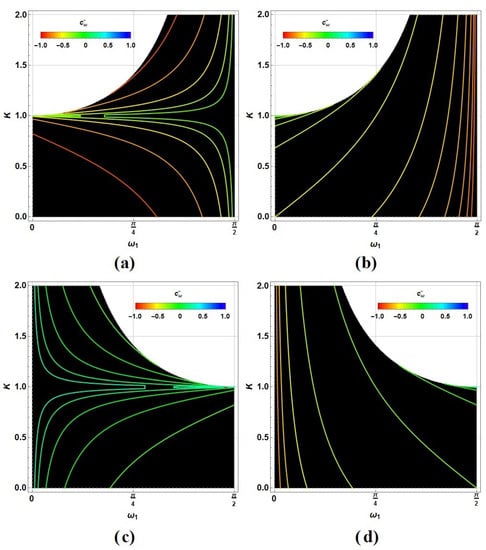

Thus, when each upper contour intersects to their lower partner, it generates the affordable solutions. Such solutions are shown in the Figure 4 but in the variables to be selected, (remembering that the selected state for Bob is ): (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) (in fact, , but we will maintain just those simpler expressions in the following). Curves in each plot show some affordable solutions (black region) for each value in color from red () to blue (). We have plotted the region only in the more convenient interval for being congruent with the previous remark. values are not restricted in their strength, but clearly reduces the possible solutions.

Figure 4.

Solutions for as function of and K in color (reddest for and bluest for ) for (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) .

Solving (24) for and introducing the overall restrictions in (26), we get the following expression for :

The coefficient there, , depends only on and K. An easy analysis shows that such coefficient reaches its maximum for becoming . Such optimal values are also shown for each K-curve in Figure 2c,d with blue dots. Because it is zero in their edges , then the values of such coefficient are folded in the intervals and .

Figure 5 depicts for (a) , (b) , (d) , and (e) (remembering that the selected state transmitted to Bob is ). They are three-dimensional regions (transparent clear gray regions) under the main maximal surface plotted in dark gray, which corresponds to the two folded points generated vertically by (shown by the arrows in the Figure 5a,b,d,e). Figure 5c,f show the comparison between the corresponding maximum values in each case, (c) and (f) respectively, remarking the advantage for (green) against (red), thus it is better to choose m with a different parity of the selected j. In such cases, could be selected almost openly, to then select those K values reaching at least near from 1, thus controlling better the stochastic selection of . Note in the figures, that the regions have been maintained in as it was initially recommended in the procedure. In addition, we have not extended the interval for K further than , because plot regions there become restricted to narrower non-rectangular regions as it was shown in the Figure 4, becoming unpractical because of the restricted combinations of and K values able to be selected. Still, in the practice, also provides valuable solutions.

Figure 5.

Plots for in (28) as function of and K for the cases (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) . Comparisons for the cases (e) , and (f) exhibiting the advantage for to reach higher values for .

Another important remark should be stated—Despite the election of is quite recommendable to maximize . It implies that Alice should decide to prepare the control state determining K from the beginning. Instead, the election of K independently of opens the opportunity to not fix the form of the states until the application of when should be settled (at least around a certain neighborhood of to reach the higher values of , still keeping the efficiency of the process).

6. Some Final Considerations about Benchmarking, Decoherence Effects, and Fidelity

Through the history of QKD developments since the BB84 protocol, many other approaches and different aspects in the key distribution have been tried. Of course, one of the main aspects is the security against eavesdropping, but others aspects sometimes go in different directions, for instance, the economy in the quantum resources or the robustness against quantum computer attacks. In the last case, the reduction of quantum resources in terms of not only efficiency but a feasible operation is important. Clearly, in the procedure being developed here, the economy has not been the focus, instead of the security, particularly based on the distributed tasks to set the key.

6.1. QBER and a Brief Comparison with Other Similar QKD Protocols

Thus, comparison between protocols is usually complicated because there are lots of elements to be performed. Moreover, some developments put more attention on certain variables to highlight the goodness of their approaches. In this subsection, we account for a review of similar BB84-like protocols in terms of some relative indicators for security. Despite the current development, the is the outstanding feature because it measures the effective use of the sifting for Eve (when she gets the correct outcome without detection), the most common comparative reference is the QBER. Thus, we show in the Appendix D, that the conditional QBER (relative to the useful outcomes when the basis of Alice and Bob) becomes:

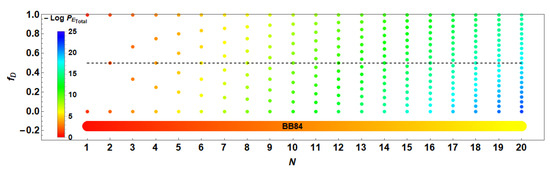

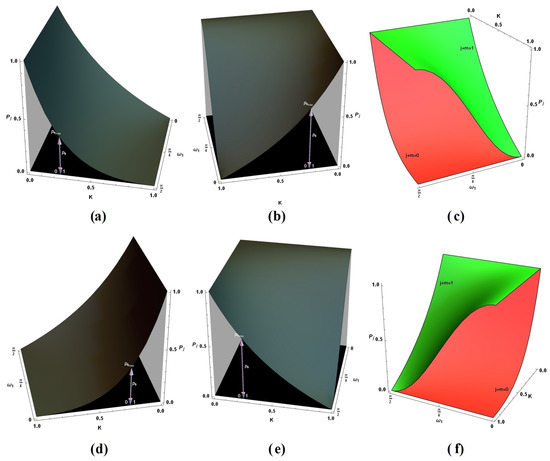

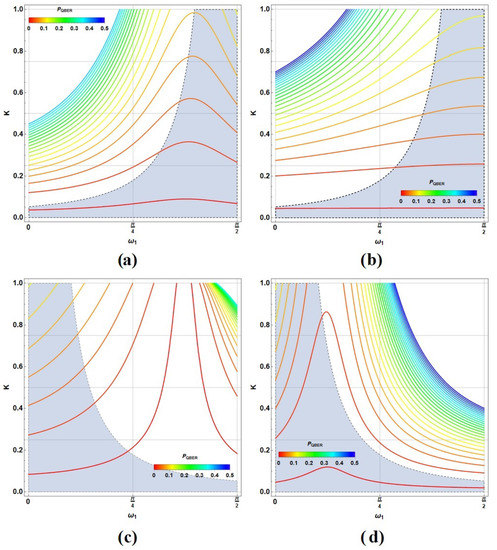

Again, note the coefficient is non-meaningful due , but instead, is proportional to . In addition, note that , then . Figure 9 shows the contour plots for as function of and K corresponding to (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; and (d) remarking the region with . Each contour value of was coloured in agreement with the color bar besides.

Figure 9.

Contour lines for the conditional QBER, , as function of and K in color for (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; and (d) . corresponds to the gray region.

Inside the region shown with and , the QBER drops in average around (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) relative to each figure. Despite, alternative elections with larger K and values (as instance and ) raises those values to (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) respectively, near of the threshold for the QBER in the BB84 protocol [55], and under the security bound of [56]. This fact is interesting because the method is configurable by selecting the region where and are both satisfactory. Thus, if QBER is the main goal (the detection of eavesdropper more than its failure), then, regions with larger K values could be more practical. Still, some considerations should be analysed due to decoherence effects that could increase the QBER [57], thus reaching the security bound. It will be discussed in the next subsection.

As it was stated in Section 5, the trend of BB84-like protocols has continued by proposing new approaches mainly based on this protocol. Thus, the BBM92 protocol [12] reports for individual attacks a theoretical QBER of and a success probability of eavesdropping of as the BB84 one. The SSP98 protocol [40] has reported theoretical QBER values of and success probability of . Nevertheless, practical implementations report QBER’s of and [58] for BB84 and SSP98 respectively. The SARG04 protocol [13] has reported QBER from and for single-photon and double photon pulses respectively. In newer protocols based on BB84 as MKP16 protocol [43] the QBER range from until depending on the initial number of qubits generated. Thus, the development of QKD protocols is not uniformly developed going first on the proposal, the QBER or success probability analysis, the attack type to be considered in the analysis. Each one could have different complexity, requiring further developments for its analysis through those several approaches highlighting their goodness. For the current procedure, the QBER is on the range of the BB84 protocols, despite, it exhibits outstanding properties in terms of the reduced Eve success probability, his possible configuration, and the existence of quantum correlations during the quantum key generation.

6.2. Fidelity and Possible Decoherence Effects Due to the Environment

Technical implementations for security protocols involving quantum processing, as the current one, will depend strongly on the physical system where it pretends to be implemented. Quantum decoherence due to the interaction with the environment differently affects setups settled on photonic systems than matter systems. While photonic implementations are recommended whenever quantum information should not be stored. Despite quantum processing is commonly settled on gates models, all of them finally involve or reduce to physical interactions ruled by a Hamiltonian. For matter, the preferred approach to analyse such decoherence are the quantum open systems equations as Linblad or Redfield ones [59]. A simpler but none-less useful approach is the modelling of decoherence through non-Hermitian Hamiltonians [60]. Still, both approaches can become complex if a large number of gates are involved.

Thus, quantum decoherence is the main challenge to reach scalability and reliability. In addition, it is known that decoherence effects (dephasing, amplitude, and depolarizing) increase harmfully the QBER to undesired effects near from the security bound [57]. A precise quantification about the fidelity of such systems is complex because it depends on the type and size of the gate and its architecture; also, on the number and kind of the quantum states involved, particularly those involving entanglement. For these reasons, together with the development of quantum information and its processing, this problem has been tackled through practical considerations for different implementations on matter and for the most typical gates [61]. While for photonic implementations decoherence becomes mild, it is not true for matter systems. Thus, gates as , Hadamard, , Toffoli, and so forth, all of them involved in the current procedure, have been recently analysed for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) using the Lindblad equation to give certain guidelines to quantum circuit designers about the decoherence for the most typical gates, thus reporting their fidelity behavior [62]. Such analysis shows as expected, that the decoherence process and the further loss of fidelity depend on the input state and the type of decoherence. By analyzing amplitude and phase damping as the most representative examples of noise, several aspects arise in the analysis: (a) deeper circuits (circuits with more gates) of course exhibit lower fidelity, (b) multiqubit gates do not necessarily show lower fidelity than single qubit ones, and (c) shorter time-scales to reach each gate still maintain fidelities near to one. For Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) technologies, global coherence times are in the range of 50–100 s. Dealing with fidelities routinely implemented above for single qubits gates, but also many two qubits gates. While, individual operation times are in the order of nanoseconds, so large circuits can be addressed during the entire coherence times [63]. Thus, circuits containing tens of gates are currently able to be implemented. Table 4 accounts for the gates and their barely type arranged by process (DT for double teleportation and PP for post-processing) and the number of qubits involved. More than half are single qubits gates, showing that the implementation on matter-based technologies is in order.

Table 4.

Depth and number of each type of gate involved through the different steps of the whole QKD protocol (DT and PP).

6.3. Quantum Processing in QKD Developments and Post-Quantum Cryptography

The protocol proposed has implemented quantum processing to a great extent compared with the most traditional procedures. Because quantum cryptography promises unconditional security in data communication because it is currently pretended to be deployed for military and commercial applications, it should be secure. Despite QKD is being widely adopted, it still faces several important challenges regarding the rates for secret key settlement, communication distance and decoherence, deployment sizes, the effective cost in terms of quantum resources, maintenance, and security [64]. As it was stated through the development, quantum coherence is preferable mandatory to reach all the basic features provided by Quantum mechanics.

Quantum computers are believed to solve (at least via problem translation) any exponential problem in principle solvable by a classical computer but not in a finite time. Then, due to classical cryptography protocols are commonly breakable in an exponential time, they are susceptible to failure under such scenarios. Then, with the advent of quantum computers, the necessity to develop secure QKD protocols under their possible attacks is mandatory. Post-quantum cryptography (sometimes also referred as quantum-safe cryptography) deals with cryptographic algorithms thought to be secure against cryptanalytic attacks performed by an ideal quantum computer in terms of coherence, prompt quantum resources, and speed-up [32].

While in conventional symmetric cryptography algorithms, the security in communication is solely related to the secrecy of the encryption key, other QKD protocols currently studied, exploit an asymmetry in their implementation, thus stating the state-of-the-art in their practical implementations [64]. In the post-quantum cryptography terrain, despite currently experimental quantum computers still lacking processing power to break any contemporary cryptographic algorithm, people working in the frontier of theoretical cryptography are preparing impressive protocols to prepare for a time when quantum computers become a real threat. It requires implementing mathematics, physics, and technology to a great extent.

Cryptography systems are commonly grouped in several cryptographic classes [17]. Despite linear, our procedure could be adapted to be asymmetrically non-linear in (24); together, authentication introduced by parameters could be specialized to introduce a Courtois, Finiasz and Sendrier Signature scheme [65], thus being able to fall in the Multivariate-quadratic-equations and the Code-based schemes. It suggests a fusion between the classical cryptography schemes with trends based on Quantum mechanics features.

7. Conclusions

The BB84 protocol is the most representative protocol in quantum cryptography. The protocol uses a single quantum channel to transfer quantum encoding states. Despite an outstanding security performance, it still allows the possibility to steal the key by interfering with the mentioned quantum channel under individual attacks by an eavesdropper. Since its development, many other BB84-like protocols have been developed, many of them called by specific names despite their clear similitude to the BB84 one. There is not a unique line of development, instead, they commonly attend to some improvements in the protocol such as economy, security, and so forth.

In the present work, a protocol for the settlement of QKD using double teleportation and quantum processing together has been proposed. The procedure generates an entangled multipartite system among three parties plus a control system. The involved entanglement, together with local control, still allows us to manipulate the global quantum state on different parts to those exerting it. The process involved in the double teleportation plus post-processing has been shown to have non-locality activation, thus stating quantum correlations. Thus, an asymmetric post-processing scheme is proposed to generate and assemble a quantum state on a selected basis (defined by the state to teleport) on one of those parts. Then, it is shaped under the proper control, finally setting the QKD protocol.

7.1. Summarizing and Featuring the Protocol

The QKD procedure presented is intended to generate sensitive secret information to transmit it to a second party but is still assembled by post-measurement during the process, instead of like previous QKD protocols, such as the BB84, where any sensible information is transmitted by a quantum channel directly, being affordable for eavesdroppers at all times. Thus, the protocol presented also considers the action of a possible eavesdropper performing an individual attack under time uncertainty. In fact, with the correct prescriptions, Alice can guarantee with the desired success threshold on her post-measurement, a faithful reproduction of the BB84 protocol. Nevertheless, the control complexity is increased, together with implementations of double teleportation and quantum processing, the success for the eavesdropper becomes notably reduced if the attack is performed before the assembling. QBER remains in the typical range and it could be configurable on the election region of the parameters. Thus, while the eavesdropper has in the BB84 protocol a theoretical chance of success on the useful key, in the present protocol, the probability of success drops down to as low as between and , thus improving the security.

Due to the processing complexity involved, aspects regarding the decoherence demand attention. There is not a unique procedure to quantify the loss of fidelity for a trend of gates, mainly because it depends on their architecture, specific physical realization and, inclusively, on the input states being considered. Despite this, for technologies other than light (which reaches large decoherence times), such as NISQ ones, currently there is a good fidelity performance of around for the range of tens of gates. Then, despite the reports stating an increase of QBER due to decoherence, it still could be controlled by reducing the operation times of the gates as in the NISQ technologies.

7.2. Future and Additional Research

Additional research of course should be extended to probe the effectiveness extent against collective and coherent eavesdropping attacks for this protocol using asymptotic formulas or numerical analytic approaches [66]. We have limited our analysis to individual attacks, assuming Eve only has access to public communication and the end of quantum edge of Bob before the assembling of the key. However, for collective attacks, where Eve brings each quantum signal and hears all public communication between Alice and Bob [18], more decisive probes are needed.

Together, extensions for the current approach in the six-states protocol direction [40,47] should be tried with more general and complex processing to that established in (12), instead with the full form for two-quibit rotations: , with , thus introducing additional parameters for the basis selection. In that trend, deeper elements regarding the classical authentication and the mathematical relation stated by the parameter K could be oriented to well-stated methods in classical cryptography.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.; methodology, F.D.; software, C.C.-I. and F.D.; validation, C.C.-I. and F.D.; formal analysis, F.D.; investigation, C.C.-I.; resources, C.C.-I. and F.D.; data curation, C.C.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.-I. and F.D.; writing—review and editing, C.C.-I. and F.D.; visualization, C.C.-I. and F.D.; supervision, F.D.; project administration, C.C.-I. and F.D.; funding acquisition, C.C.-I. and F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the economic support to publish this article to the School of Engineering and Science from Tecnologico de Monterrey. Carlos Cardoso-Isidoro and Francisco Delgado acknowledge the support of CONACYT.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Control on Faraway Non-Local Resources

Controlled operations on faraway non-local parties as that in the second factor of (7), , are not possible to be performed directly (assuming that the control and qubit 4 cannot be moved from their locations). Nevertheless, they can be achieved via LOCC with the support of an entangled pair where qubit a is in possession of Alice and b is sent to Bob:

A direct calculation shows that a such state can be written in the basis of the Bell states for the qubits C and a as:

then, Alice applies the operation on her qubits, getting:

The following development could be achieved using delayed measurements [35] or still just controlled operations. Despite, they commonly require interactions between faraway resources, which implies some of them will be moved from their locations using extra classical communication operations. Instead, we will use projective measurements and corrections. Thus, Alice measures their qubits obtaining the outcomes and respectively. Using classical communication, Alice shares those outcomes with Bob who applies the controlled operation . The outcome is:

thus, Bob applies the controlled operation :

Finally, qubit b is sent to Alice to perform the operation:

which, disregarding the qubits a and b, is the same state obtained by .

Appendix B. SWAP Operations between Faraway Non-Local Parties

As in the Appendix A, we will show how to perform the operation between the faraway parties (assuming they cannot be moved close together). Again, we will use the entangled resource where qubit a is in possession of Bob and b is sent to Bob:

As before, by rearranging the qubits 2 and a in the first term of (A8), and expressing it in terms of Bell stats basis:

then, Alice and Bob apply the controlled operation on their qubits (where, . Then, it becomes:

then, Bob measures qubits 2 and a if the control register is , getting and using controlled quantum measurements [36,37]. Thus:

Using controlled classical communication, the measurement outcomes are shared with Bob just if the control register is to perform the operation and then , all of them on his qubits. Similarly, Bob applies and . It gives:

Finally, Bob uses controlled quantum measurements again when the control register is to measure the qubit a getting as outcome. He performs and uses controlled classical communication to share the outcome to Bob who performs . It gives the state:

which, disregarding , fits with in (10) upon the application of .

Appendix C. Conditional Probability for Eve Success in the Protocol

Departing from the double teleported state after of the Bob processing but before to the Bob processing and Alice’s measurement of the control system:

then, we consider the state stated on the basis generated by the parameters:

so, we get the expressions for the following projections:

where we have defined the quantity:

Then, Eve performs the sifting on the Bob state measuring it and then returning it to Bob. In addition, Bob processing is followed, which gives (omitting the tensor product for simplicity, but indicating the systems with a proper subscript):

where the previous expressions have been applied on the corresponding projections on the Bob state. At this point, note that the Eve sifting could be performed equivalently before or after to the Bob processing because measurement and the last processing works on different systems. It implies that Type B and C become equivalent for the current calculation as it was stated in Section 5.2. Thus, in any case Eve obtains as outcome (after selecting the basis defined by ).

In the following step, the is applied between the Bob’s, giving:

Then, Alice performs the measurement of the control state on the basis stated by the election of K. Here, she hits her selection so the next measurement performed by Bob could be performed equivalently after or before to the Alice’s measurement for calculation purposes. Employing such property, we get first:

where it has been assumed that he hits on the same basis selection and outcome that Eve to then get the success probability of her. Then, finally performing the Alice’s measurement with outcome :

We will need to switch as the outcome obtained by Eve and Bob in the main text. In this way, by imposing the prescriptions to assemble the transmitted state from Alice to Bob discussed in the text: , as well as Formulas (24) and (25), we calculate the norm of the last state. It corresponds to the success probability for Eve, P, given when Eve and Bob meet their outcomes and basis, while Alice succeeds in her planned measurement:

where we have reduced applying the prescriptions. Note this probability is referred to the entire process. To get the conditional or relative probability to the useful key cases, , we will need to divide P by the corresponding to restrict the universe to the successful control measurement outcome, because in fact, it implies that Alice, Eve, and Bob meet their measurement basis and outcomes.

Appendix D. Conditional QBER in the Protocol

Similarly to the Eve success probability, taking the teleported state after of the Bob processing but before to the Bob processing and the Alice’s measurement of the control system (A14), then we consider the sifting and measurement from Eve, reaching the outcome , with , the basis planned by Alice. is also not necessarily equal to (the outcome finally obtained by Bob). Following the expressions (A15)–(A17): and , where, in this case, we introduced the quantity:

As before, Eve performs the sifting, measuring, and returning on the Bob state. Then, Bob processing is followed similarly as in (A19), giving:

Observe that, in any case, Eve obtains as the outcome (by selecting the basis defined by ). Now, the is applied between the Bob’s, obtaining:

Now, Alice performs the measurement of the control state on the basis stated by K, hitting and generating the state on qubit 4, thus:

where it has been assumed that he hits on a different basis selection than Eve, and a different outcome, but still in the same basis than Alice planned. It will let, under the reconciliation, notice the presence of Eve. Then, finally performing Alice’s measurement with outcome :

where is the same expression as in (A18) but changing k by and . As in the Appendix C, we set the prescriptions there. With this, and . Additionally, we note that if is the outcome planned by Alice to reach Bob in absence of the Eve’s intervention, then we will need set . It implies that . Finally, by obtaining the norm of (A28), then summing over , we get the absolute QBER (without disregarding the failures in the control measurement by Alice):

To get the conditional or relative QBER to the useful key cases, , we will need, as before, to divide by the corresponding to restrict the universe to the successful control measurement outcome.

References

- Hong, K.W.; Foong, O.M.; Low, T.J. Challenges in Quantum Key Distribution: A Review. In ICINS ’16: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Network Security; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, C.; Parag, A.; Datta, S. Different Vulnerabilities And Challenges Of Quantum Key Distribution Protocol: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2017, 8, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. Cryptography. In Theoretical Advances in Practical Quantum Cryptography; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, V.; Anisimov, A.; Skaar, J. Effects of detector efficiency mismatch on security of quantum cryptosystems. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 022313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeed, S.; Radchenko, I.; Kaiser, S.; Bourgoin, J.P.; Pappa, A.; Monat, L.; Legré, M.; Makarov, V. Attacks exploiting deviation of mean photon number in quantum key distribution and coin tossing. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 91, 032326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, D. The Uncertainty relations in quantum mechanics. Curr. Sci. 2014, 107, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.A.B. Entanglement. In Quantum Mechanics for Scientists and Engineers; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gyongyosi, L.; Imre, S. Dense Quantum Measurement Theory. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.-F.; Zhen, Y.-Z.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Chen, Z.-B.; Liu, N.-L.; Chen, K.; Pan, J.-W. Highly Efficient Quantum Key Distribution Immune to All Detector Attacks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1410.2928. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Gupta, D.-L.; Singh, A.-K. Quantum Key Distribution Protocols: A Review. IOSR J. Comput. Eng. 2014, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G. Quantum Cryptography: Public Key Distribution and Coin Tossing. In Proceedings of the Computer System and Signal Processing, Bangalore, India, 10–12 December 1984; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H. Quantum cryptography using any two nonorthogonal states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarani, V.; Acin, A.; Ribordy, G.; Gisin, N. Quantum Cryptography Protocols Robust against Photon Number Splitting Attacks for Weak Laser Pulse Implementations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 057901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert, A.-K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathi, V.; Vishnu-Vardhan, B.; Krishna, A.-V.-N. Quantum Cryptography and Quantum Key Distribution Protocols: A Survey. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing, Bhimavaram, India, 27–28 February 2016; pp. 556–562. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.; Nordholt, J. Refining Quantum Cryptography. Science 2011, 333, 1584–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Lange, T. Post-Quantum Cryptography: Dealing with the Fallout of Physics Success; Cryptology ePrint Archive: Report 2017/314; TU/e: Eindhoven, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, H.K.; Chau, H.F. Unconditional Security of Quantum Key Distribution over Arbitrarily Long Distances. Science 1999, 283, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwmeester, D.; Pan, J.; Mattle, K.; Eibl, M.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 1997, 390, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Kulik, S.P.; Shih, Y. Quantum Teleportation of a Polarization State with a Complete Bell State Measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.C.; Mao, Y.L.; Chen, S.J.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, W.J.; Miki, S.; Yamashita, T.; Terai, H.; et al. Quantum teleportation with independent sources and prior entanglement distribution over a network. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Cryptography in the Age of Quantum Computers 2.0; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, B.J.; Spring, J.B.; Humphreys, P.C.; Thomas-Peter, N.; Barbieri, M.; Kolthammer, W.S.; Jin, X.M.; Langford, N.K.; Kundys, D.; Gates, J.C.; et al. Quantum teleportation on a photonic chip. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.; Rigolin, G. Asymptotic security analysis of teleportation-based quantum cryptography. Quantum Inf. Process. 2020, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Riedmatten, H.; Marcikic, I.; Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H.; Collins, D.; Gisin, N. Long Distance Quantum Teleportation in a Quantum Relay Configuration. Phys. Rev. Let. 2004, 92, 047904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursin, R.; Jennewein, T.; Aspelmeyer, M.; Kaltenbaek, R.; Lindenthal, M.; Walther, P.; Zeilinger, A. Quantum teleportation across the Danube. Nature 2004, 430, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesue, H.; Dyer, S.D.; Stevens, M.J.; Verma, V.; Mirin, R.P.; Nam, S.W. Quantum teleportation over 100 km of fiber using highly efficient superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. Optica 2015, 2, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Isidoro, C.; Delgado, F. Symmetries in Teleportation Assisted by N-Channels under Indefinite Causal Order and Post-Measurement. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Isidoro, C.; Delgado, F. Post-selected double teleportation and the modelling of its related non-local properties. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2090, 012033. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Isidoro, C.; Delgado, F. Quantum authentication using double teleportation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Zeng, G.; Xiong, J. Quantum key agreement protocol. Electron. Lett. 2004, 40, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Smith-Tone, D. Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. Introduction to post-quantum cryptography. In Post-Quantum Cryptography; Bernstein, D.J., Buchmann, J., Dahmen, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Crépeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W.K. Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, O.A. Topics in Quantum Computing; CreateSpace Independent Pub: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dusek, M.; Buzek, V. Quantum-controlled measurement device for quantum-state discrimination. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 66, 022112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiurásek, J.; Dusek, M.; Filip, R. Universal measurement apparatus controlled by quantum software. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 190401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.-B.; Eleuch, H.; Raymond-Ooi, C.-H. Non-locality Correlation in Two Driven Qubits Inside an Open Coherent Cavity: Trace Norm Distance and Maximum Bell Function. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Eleuch, H. Quantum correlation control for two semiconductor microcavities connected by an optical fiber. Phys. Scr. 2017, 92, 065101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruß, D. Optimal Eavesdropping in Quantum Cryptography with Six States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 3018–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.-H.; Brassard, G.; Mermin, N.-D. Quantum cryptography without Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusca, D.; Boaron, A.; Curty, M.; Martin, A.; Zbinden, H. Security proof for a simplified Bennett-Brassard 1984 quantum-key-distribution protocol. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 052336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, M.; Poonia, R.-C. Design a New Protocol and Compare with BB84 Protocol for Quantum Key Distribution. In Soft Computing for Problem Solving Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Serna, E.-H. Quantum Key Distribution from a Random Seed. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1311.1582v2. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, S.-K.; Hwang, T. Quantum key agreement protocol based on BB84. Opt. Commun. 2010, 283, 1192–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, F.; Franz, T.; Berta, M.; Leverrier, A.; Scholz, V.; Tomamichel, M.; Werner, R. Erratum: Continuous variable quantum key distribution: Finite-key analysis of composable security against coherent attacks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 019902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechmann-Pasquinucci, H.; Gisin, N. Incoherent and coherent eavesdropping in the 6-state protocol of quantum cryptography. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 59, 4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirandola, S.; Andersen, U.L.; Banchi, L.; Berta, M.; Bunandar, D.; Colbeck, R.; Englund, D.; Gehring, T.; Lupo, C.; Ottaviani, C.; et al. Advances in Quantum Cryptography. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2020, 12, 1012–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M.; Liss, R.; Mor, T. Security Against Collective Attacks of a Modified BB84 QKD Protocol with Information only in One Basis. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk, Porto, Portugal, 24–26 April 2017; Volume 1, pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos, G.M.; Khalique, A.; Alber, G. Provable entanglement and information cost for qubit-based quantum key-distribution protocols. Eur. Phys. J. D 2015, 37, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lo, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, K. Decoy State Quantum Key Distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 230504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zha, X.; Chen, Z.; Shi, R.; Wang, D.; Peng, T.; Yan, L. Performance Analysis of Quantum Key Distribution Technology for Power Business. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Guha, S.; Shapiro, J.; Bash, B. Performance analysis of free-space quantum key distribution using multiple spatial modes. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 19305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.; Xu, F.; Pan, J.; Ekert, A. Security Analysis of Quantum Key Distribution with Small Block Length and Its Application to Quantum Space Communications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottesman, D.; Lo, H. Proof of security of quantum key distribution with two-way classical communications. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2003, 49, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisin, N.; Ribordy, G.; Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wen, Q.; Gao, F.; Zhu, F. Robust variations of the Bennett-Brassard 1984 protocol against collective noise. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 80, 032321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H. Asymptotically Optimal Quantum Key Distribution Protocols. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.01973v3. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, H.; Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eleuch, H.; Rotter, I. Nearby states in non-Hermitian quantum systems I: Two states. Eur. Phys. J. D 2015, 69, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, S.; Pachos, J.; Hinds, E.; Knight, P. Quantum Gates and Decoherence. In Quantum Coherence; Springer: Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ash Saki, A.; Alam, M.; Ghosh, S. Study of Decoherence in Quantum Computers: A Circuit-Design Perspective. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.04323v1. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaergaard, M.; Schwartz, M.; Braumüller, J.; Krantz, P.; Wang, J.; Gustavsson, S.; Oliver, W. Physics Superconducting Qubits: Current State of Play. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter 2019, 11, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti, E.; Lo, H.; Qi, B.; Yuan, Z. Practical challenges in quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 2016, 2, 16025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, N.; Finiaz, M.; Sendrier, N. How to achieve a McEliece-based Digital Signature Scheme. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2001. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 2248, pp. 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bunandar, D.; Govia, L.; Krovi, H.; Englund, D. Numerical finite-key analysis of quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 2020, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).