Abstract

In this paper, algebraic relations were established that determined the invariance of a transformed number after several transformations. The restrictions that determine the group structure of these relationships were analyzed, as was the case of the Klein group. Parametric functions associated with the existence of cycles were presented, as well as the role of the number of their links in the grouping of numbers in higher-order equivalence classes. For this, we developed a methodology based on binary equivalence relations and the complete parameterization of the Kaprekar routine using Ki functions of parametric transformation.

1. Introduction

The process known as Kaprekar’s routine consists of sorting the digits in a number in descending order. Then, the opposite arrangement takes place, i.e., in ascending order. These two arrangements are subtracted one from another, resulting in an image of the original number. In 1949, Datlatreya Kaprekar [1] showed that when iterating such a process with four-digit numbers, the result was always 6174.

This routine of transformation has always aroused interest among fans of mathematical games [2]. However, additionally, there is important research regarding this routine has taken place among mathematicians specialized in Number Theory. Much of this effort has been directed to determining constants and cycles in various numbering systems and numbers of digits, as well as some aspects of transformation chains such as maximum distances.

Thus, the work of Prichett et al. stands out [3,4]. This group of researchers established the basic functions of numerical transformation. An n-digit is a constant of Kaprekar if and only if that number is a fixed point under Kaprekar’s routine and all numbers are transformed to that number after a finite number of applications of Kaprekar’s transformations. They determined the all one-cycle at base 10 and showed that the only decadic Kaprekar’s constants are 495 and 6174. In 2005, Walden [5] already presented some new results on the Kaprekar’s constant, establishing the unique four-adic, seven-digit and five-adic, nine-digit Kaprekar’s constant and showing that 15, 21, 27 or 33-digit Kaprekar constants do not exist. The work on the Kaprekar’s constant has continued with the interesting contributions of Dolan [6], Prince [7], Hanover [8] and Thakur [9], among others.

In addition to the study of Kaprekar’s constants, the number of transformations necessary to reach the constants or cycles has also been studied. Thus, in a recent work, Yamagami [10] collected data on the number of cycles N (b, n) and their number of links l (b, n) for some bases 2 ≤ b ≤ 15 and numbers of digits 2 ≤ n ≤ 15, many of which were calculated by the author. He noted: “It is very hard to obtain general results on b-adic n-digit Kaprekar loops for all b and n without observing any case-by-case results”. Therefore, he thinks that results with specific n or b values as in the known results above are very valuable to further research. In this article, he considers a case where b = 2 and n = 2. He proves that any two-adic Kaprekar’s constant is the two-adic expression of a product of two suitable Mersenne numbers. He also obtains some formulas for the Kaprekar distances. In 2018, together with Matsui [11], he published other paper on three-adic Kaprekar loops. They obtained the formulas for the number for all three-adic n-digit Kaprekar loops and their lengths in terms of n. Wang and Lu [12] continued Yamagami’s studies and completed them with a general solution. Meanwhile, Devlan and Zang [13] determined the maximum number of iterations required to reach a fixed point in the four-digit process.

The constant 6174 has always been surrounded by a halo of mystery [14]. The exploration of Kaprekar’s constant is a problem that allows for multiple approaches to investigation. This possibility, together with its mysterious nature, explains why it is frequently used as a didactic resource [15]. The discovery of the patterns produced by Kaprekar’s process promotes much excitement and insight into the world of mathematical discovery among students [16].

On the other hand, recent studies have investigated variations of the Kaprekar’s transformation [17,18]. In particular, we highlight the interesting paper of Bajorska-Harapinska et al. [19], which presented and discussed some variations of Kaprekar’s transformation. They were especially interested in the orbits of such transformations. For such, they understood the sets of all iterations of a transformation function on a fixed point. They provided their full description for small numbers and also proved some general properties. In 2021, Stephen et al. [20] already defined generalized αs-Meir–Keeler contractions in Sb-metric spaces and used them to examine the existence and uniqueness of fixed points.

There is a current of opinion that understands there are important gaps in the understanding of Kaprekar’s process. We are interested in investigating the possible connections with Group Theory. We have not found previous studies on this aspect or on the existing symmetries in the transformation chains. In fact, the verification of this gap in the literature has been the main motivation of our work.

In this work, we approach the study of the transformation in base 10 with generality of the number of digits, and the following questions will be addressed:

- –

- What are the algebraic relations that must exist between the numbers for their images to coincide after one or several transformations? For example:

- ○

- Why do 83,246,529 and 17,487,561 return the same transformed number?

- ○

- Why do 8,178,382,562 and 4,774,473,809 return the same number after two transformations?

- ○

- Why do 5,068,069 and 3,071,934 return the same number after four transformations?

- –

- What algebraic structures underpin these symmetries?

- –

- What is the relation between cycles and the algebraic architecture of the transformation schemes?

2. Design of the Investigation and Methods

Every number has an image through Kaprekar’s routine, and that image is unique. The image of a number is uniquely determined by some parameters α that characterize it (Section 3). All numbers with the same parameters give the same image. This leads to the study of Kaprekar’s routine in parametric terms.

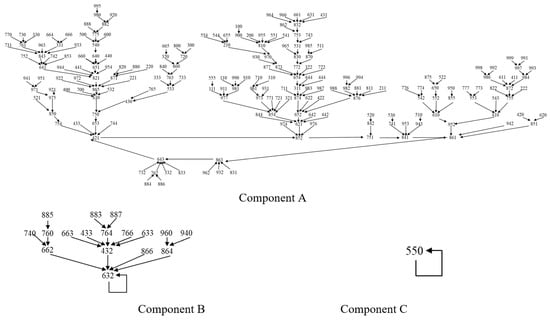

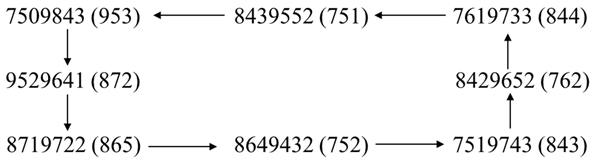

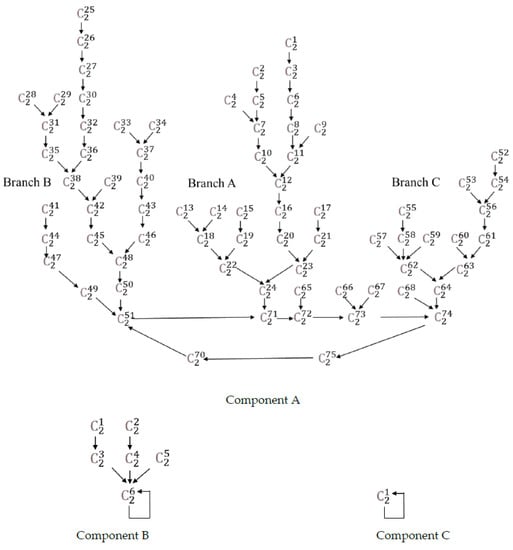

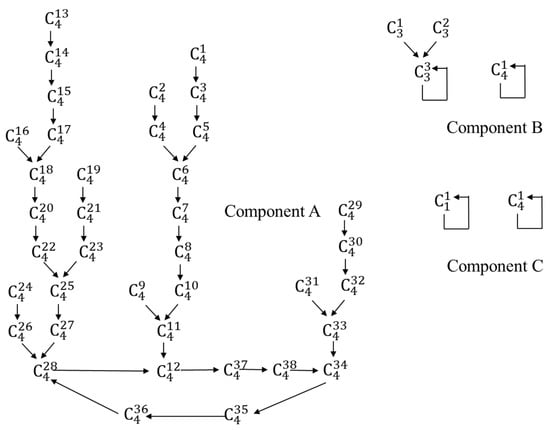

The scheme of parametric transformations can have one or more components. An example can be seen in Scheme 1, corresponding to a 6-digit case with three components. Any component of a scheme is necessarily coalescent and contains a transformation constant (parameters whose image is themselves) or a cycle of 2 or more links. This is due to the uniqueness of the transformation and to the fact that the set of all numerical images is a subset of the multiples of 9 (Section 3). Its cardinal is much smaller than that of the set of reference numbers.

Scheme 1.

Parametric transformation schemes in A6. Each number is a class (α ß γ).

Consequently, invariances necessarily appear: sets of numbers that give the same image after one or more transformations. Or, in a dual way, these can be parameters that give the same parametric image. Our fundamental objective is to find the algebraic relations that determine these invariances, or, in other words, to identify the symmetries algebraically.

For this, we employed binary equivalence relations. These relationships, characterized by their reflexive, symmetric and transitive properties, allow one to establish partitions in a set of numbers (or of the parameters) so that all the elements of a class have the same image. We thus defined a binary equivalence relation Rr of order r as the one that exists between numbers that give the same image after r transformations (Section 7.1). As a result of what has already been said, the relation R1 is the one that exists between numbers with the same parameters.

However, how can we determine the R2 and higher relations? For this, we studied and developed the properties of the Rr relations. Among them, we found (33) α1 Rr α2 ↔ α′1 Rr-1 α′2, with α′ being the parametric image of α. This relationship is methodologically fundamental. It allows one to obtain the higher-order Rr relations from the lower-order ones. For example, R3 can be obtained from R2. For this, it is necessary to develop Ki functions of parametric transformation such that Ki (α) = α′ (Section 4). Each of these functions is associated with a permutation that reorders the digits of the transformed number in decreasing order. However, not all permutations are possible; the restriction must be met (3). This leads to a technical difficulty in the development of the functions Ki.

When parametric transformation functions Ki and er functions are associated with equivalences, we can algebraically determine higher-order equivalences. If an equivalence Rr is imposed on the images of two parametric classes α1 and α2, Ki (α1) and Kj (α2), the result will be an algebraic relation between α1 and α2 so that α1 Rr + 1 α2. In summary, one of the basic methods used is (51).

(er × Ki) (α1) = Kj (α2)

Other analogous methods derive from the properties of the Rr developed in Section 7.1.

Another methodological contribution of this work is to show how Ki functions can be used to study constants and cycles.

3. The General Process

Let any number n of w digits n = a1 a2 … aw belong to set Aw ⊂ ℤ, excluding numbers with identical digits. Let numbers of fewer digits be included, as long as they are completed by adding zeros to their left. Let us use the decimal numeral system, so that 0 ≤ ai ≤ 9, I = 1, … w.

Let Od be an operator that sorts the digits of a number in descending order:

x = Od (n) = x1 x2 … xw, xi ≥ xi + 1 and let Ou be another operator which does the opposite: y = Ou (n) = xw xw-i … x1.

Generalized Kaprekar’s routine is formalized through an operator K such that

K (n) = n′ = x − y = Od (n) − Ou (n)

For example, if n = 83,246,529, Od (n) = x = 98,654,322

Ou (n) = y = 22,345,689, n′ = K (n) = x − y = 76,308,633

The iteration of the process r times is represented by

agreeing that K0 (n) = n and writing K1 = K for convenience.

In our example, K2 (83,246,529) = 84,326,652.

Arranging the digits through Od allows us to define the following parameters, which result from subtracting the digits in x that are symmetrical compared to the central value.

must be verified as a consequence of the arrangements (1) forced by the routine.

αs ≥ α s + 1, s = 1, … h − 1

Thus, for w = 4, α1 = x1 − x4, α2 = x2 − x3. For simplicity, these parameters are referred to as α = α1 and ß = α2 in further examples. In a similar way, the same parameters exist in A5.

As is shown below, parameters αs uniquely determine the image of a number. Consequently, any number is characterized by their parameters, which are represented as follows:

When the situation is unambiguous, such parameters are written together as a number of h digits.

The transformation functions are the following:

- (1)

- If 0 < αs ≤ 9, s = 1, 2, … h

- (1.1)

- w =, h = w/2

f1 (α1 α2 … αh) = (x1-xw x2-xw-1 … xw-1-x2 xw-x1) = (α1 α2 … αh -αh …-α2 -α1) =

(α1 α2 … αh − 1 αh − 1 9 − αh 9 − αh−1 9 − α2 10 − α1)

(α1 α2 … αh − 1 αh − 1 9 − αh 9 − αh−1 9 − α2 10 − α1)

So, for 6-digit numbers (w = 6)

f1 (α1 α2 α3) = (α1 α2 α3 − 1 9 − α3 9 − α2 10 − α1)

f1 (α ß γ) = (α ß γ−1 9−γ 9−ß 10−α), α = α1 > 0, ß = α2 > 0, γ = α3 > 0

For instance, what is the image of 631,764?

Od (631,764) = 766,431, α = 7-1 = 6, ß = 6-3 = 3, γ = 6 − 4 = 2

p (631,764) = 632, f1 (632) = 631,764

K (631,764) = 631,764

Apparently, this number transforms into itself. It is a transformation or balance constant in A6.

However, note that any number with these same parameters will yield the same image nE. For example, m = 632,000, p (m) = 632, m′ = K (m) = nE.

Any permutation P of the digits in

(6 + a 3 + b 2 + c a b c), 0 ≤ a ≤ 3, 0 ≤ b ≤ 6, 0 ≤ c ≤ 7, a ≥ b ≥ c, a > c

Digits a′s in those numbers transformed by f1 must satisfy the following restrictions:

In the case of A6: a′1 + a′6 = 10, a′2 + a′5 = 9, a′3 + a′4 = 8, as = 27

- (1.2)

- w =+ 1, h = (w − 1)/2

In this case, function f1 is similar to the last one, but it includes a 9 as a central digit in the transformed number

f1 (α1 α2 … αh) = (α1 α2 … αh−1 αh − 1 9 9 − αh 9 − αh−1… 9 − α2 10 − α1)

For instance, the image of a telephone number

n = 34,326,714,825 would be

Od = 87,654,433,221, α1 = 7, α2 = 5, α3 = 4, α4 = 2, α5 = 1

f1 (75,421) = (7 5 4 2 1 – 1 9 9 − 1 9 − 2 9 − 4 9 − 5 10 − 7) = 75,420,987,543

Notably, for seven-digit numbers

f1 (α ß γ) = (α ß γ − 1 9 9 − γ 9 − ß 10 − α)

The digits in the transformed number must satisfy

- (2)

- If 0 < αs ≤ 9, 1 ≤ s<r and αs = 0, s ≥ r (r > 2)

- (2.1)

- w =, h = w/2

Basic function f2 is similar to (4) but adding v = 2 (h + 1 − r) digits 9 to the middle part (two nines per null parameter):

thus satisfying the conditions

a′r-1 + a′w-r + 2 = 8, a′r = a′r + 1 = … = a′w-s + 1 = 9

Specifically, for A6

f2 (α ß 0) = (α ß-1 9 9 9-ß 10-α)

For example, let n = 549,945 have the image

Od (n) = 995,544, p (n) = 550, f2 (550) = 549,945, the original number itself. This is another constant in A6.

- (2.2)

- w =+ 1, h = (w − 1)/2

Function f2 is similar to the last one but adds an extra 9 as a middle digit in the transformed number:

adding to conditions (5), a′h + 1 = 9

For A7 and γ = 0, the result is

f2 (α ß 0) = (α ß-1 9 9 9 9-ß 10-α) with

a′1 + a′7 = 10, a′2 + a′6 = 8, a′3 = a′4 = a′5 = 9

- (3)

- If 0 < α1 ≤ 9 and αs = 0, s ≥ 2

which implies the following restrictions for the transformed numbers

a′1 + a′w= 9, a′2 = … = a′w − 1 = 9

These two expressions are valid both for even and odd numbers of digits.

For A6, the result is

and for A7

f3 (α 0 0) = (α − 1 9 9 9 9 10 − α)

f3 (α 0 0) = (α − 1 9 9 9 9 9 10 − α)

Functions f1, f2 and f3 are similar to the ones developed by (4). These functions are an epimorphism of AW in BW ⊂ AW, which comprises those multiples of 9 that verify some requirement (5a.1), (5b.1) or (6.1) and that have anti images.

4. Parametric Functions

The previous development returns

which suggests the transformation process should be analyzed in parametric terms. To this end, it is necessary to know the parameters of the transformed numbers.

p (m) = p (n) ↔ K (m) = K (n)

One of the questions in the introduction is thus answered. Both numbers 83,246,529 and 17,487,561 return the same number after their transformations because both have the same parameters (7631).

Let us specify the notation used so far:

- –

- K, in a broad sense, refers to the transformation. Its argument is a number and its image is the transformed number K (n) = n′.

- –

- fi is used in a specific sense. It acts upon parameters and yields the numerical image of all numbers whose parameters are those specified.

p (n) = α, fi (α) = n′, α = α1 α2 …αh

- –

- K can also be used broadly, by extension, to mean the parameters of some transformed number, thus transforming parameters into parameters:

K (α) = α′, α′ = p (n′)

This is the biggest problem in transformations. The digits in the transformed number are not necessarily arranged, so it is not possible to determine its parameters right away. Thus, operators Od and Ou, which establish a permutation Pi that sorts the digits, must operate. Od (n′) = Pi (n′). If Pi is identified, then α′ is directly discovered. A specific function Ki (α) = α′ can therefore be associated with each permutation Pi.

This is a tedious process, since the possible permutations will grow factorially as the number of digits increases:

- –

- With w =2 and w = 3, there are just two functions Ki (α);

- –

- With w = 4 and w = 5, there are 11 functions Ki (α ß) and 2 functions Ki (α 0);

- –

- With w = 6 and w = 7, there are two functions Ki (α 0 0), 11 functions Ki (α ß 0) and 117 functions Ki (α ß γ);

- –

- With w and w + 1 digits, the number of functions Ki (α1 α2 …αs … αh), αs > 0, s = 1, … h approaches w!/h! by default. This is because in Od (n′), a permutation with αr-s to the left of αr is, under (3), only possible if αr = αr − s.

Let us see some examples of these functions.

- (1)

- Functions Ki based on (4)

w =, h = w/2, f1(α) defined in (4) and P1 (1 2 3 …w)

P1 is defined as the digit arrangement described in (4).

K1(α) = [α1 − (10 − α1) α2 − (9 − α2) … αh − 1 − (9 − αh−1) αh − 1 − (9 − αh)] =

[2α1 − 10 2α2 − 9 … 2αh − 1 − 9 2αh − 10]

[2α1 − 10 2α2 − 9 … 2αh − 1 − 9 2αh − 10]

The domain of existence of this function K1 (α) = α′ is determined by the restrictions imposed by Od (n′), with the digits being sorted in descending order (1) in permutation P1

which implies αh ≥ 5, and under (3), αs ≥5, s ≥ 1, y α1 ≥ α2 + 1

α1 ≥ α2, …, αh – 1 ≥ 9 – αh, 9 – αh ≥ 9-αh−1, …, 9 – α3 ≥ 9 – α2, 9 – α2 ≥ 10 – α1

Briefly, the existence conditions for K1 (α) are

For instance,

n = 181,771,978,221, w = 12, h = 6, p(n) = 877,655 = α, which satisfies (16);

K1 (877,655) = 655,310 and indeed, f1(n) = 877,654,443,222 = n′, p(n′) = 655,310 = α′.

Note that this α′ does not satisfy (16), so it cannot be transformed through K1. We need a function Ki based on (8), with αh = α6 = 0 (see (27) in the last case in Section (3).

w =, h = w/2, f1 (α) defined in (4) and P2 (h + 1 …w 1 2 … h)

Od (n′) = (9-αh 9 − αh−1 … 9 − α2 10 − α1 α1 α2 … αh − 1 αh − 1)

K2 (α) = (10 − 2αh 9 − 2αh−1 … 9 − 2α2 10-2α1)

For instance, in A6

K2 (541) = 810

w =, h = w/2 and P3 (h + 1 1 h + 2…w 2 3… h) in (4)

Od (n′) = (9-αh α1 9-αh−1 9-αh−2 … 9-α3 9-α2 10-α1 α2 … αh−1 αh-1)

K3 (α) = (10-2αh α1-αh−1 9- αh−1- αh−2 … 9- α3-α2 α1- α2-1)

αh ≤ 10+ αh−1 -2αh; 1 ≤ αh ≤ 4

This is an important function that generates a family of transformation constants.

- (2)

- Functions Ki based on (6)

The permutations refer to the digits to the right of 9 in (6)

w =+ 1, h = (w-1)/2, f1 (α) defined in (6) and P1

Od (n′) = (9 αl α2 … αh − 1 αh-1 9-αh 9-αh − 1 … 9-α2 10-αl)

The presence of a 9 completely changes function K1

with the existence conditions

K1 (α) = (α1-1 α1+ α2-9 α2+ α3-9 … αh − 1+ αh-9)

For example, n = 8,650,000, p (n) = 865 = α

α = 865 satisfies the conditions (20) and, in fact,

n′ = f1 (n) = 8,649,432, Od (n′) = 9,864,432, p (n′) = 752 = α′

K1 (α) = (8-1 8 + 6-9 6 + 5-9) = 752

w =+ 1, h = (w-1)/2, and P2 in (6)

Od (n′) = (9 9-αh 9-αh−1 … 9-α2 10-αl αl α2 … αh−1 αh-1)

K2 (α) = (10-αh 9-αh- αh−1 … 9-α3- α2 9- α2-αl)

αh−1 ≥ 1, 1 < αh < 5

For example, n = 2,515,324 p(n) = 432

and in fact, since 432 satisfies the existence conditions of K2

w = 7, h = 3 por (6), n′ = f1 (n) = 4,319,766, p (n′) = 842

K2 (432) = (10-2 9-2-3 9-3-4) = 842

w =+ 1, h = (w-1)/2 ≥ 4, P4 (1 h + 2 2 h + 3 … h + s 3 4 … s 2 h 2 h + 1 h), s = h-1 en (6)

Od (n′) = (9 α1 9-αh α2 9-αh−1 … 9-α3 α3 … αh−1 9-α2 10-α1 αh-1)

K4(α) = (10-αh 2α1-10 α2-αh α2-αh−1 9-αh−2-αh−1 … 9-α4-α3)

h ≥ 4; 9 ≤ α1 + αh ≤ 11, α2 + αh ≤ 9, α2 + αh−1 ≥ 9, α3 ≤ 4

For example, in w = 15, h = 7

K4 (8,643,332) = 8,643,332; therefore, this number is a parametric constant in w = 15, with the numeric constant of 15 digits, 864,333,197,666,532.

f1 (α) = (α1 α2 … α6 α7-1 9 9-α7 9-α6 … 9-α2 10-α1) = n′

Od (n′) = (9 α1 9-α7 α2 9-α6 … 9-α3 α3 … α6 9- α2 10-α1 α7-1)

K4 (α) = (10- α7 2α1-10 α2-α7 α2-α6 9-α5-α6 9- α4-α5 9-α3-α4)

Similarly, for nine digits

K4 (α ß γ δ) = (10-δ 2α-10 ß-δ ß- γ), K4 (8642) = 8642, which is a parametric constant in A8.

K4 (α), defined in a general way at w = + 1, is an important parametric function from which one-cycles derive.

- (3)

- Functions Ki based on (8)

Functions Ki based on (8), h = w/2 are complex, as they depend on the number of null parameters compared to the number of non-null parameters. If r ≤ 1 + h/2, αr = 0, then the functions’ structure remains, since (8) provides as many nines as it provides varying digits. If there are more non-null than null parameters, r > 1 + h/2, then functions Ki will vary with each r increment.

Let us see some examples:

- –

- w = , r ≤ 1 + h/2, α3 = 0, h ≥ 4 in (8) and P1

If permutation P1 (1234) is used to the right of numbers 9 in Od (n′)

the associated function is

For example: K21 (85,000) = 75,510

- –

- w =, r ≥ 1 + h/2, α3 = 0, h = 3 in (8) and P1

n′ = f2 (α1 α2 0) = (α1 α2-1 9 9 9-α2 10-α1)

Od (n′) = (9 9 α1 α2-1 9-α2 10-α1)

K22 (α1 α2 0) = (α1-1 α2 α1-α2 + 1), 6 ≤ α1 ≤ 9, 5 ≤ α2 ≤ 9, α1 ≥ α2 + 1, 2α2 ≥ α1 + 1

For example: K22 (850) = 754

- –

- w =, r ≤ 1 + h/2, α3 = 0, h ≥ 4 in (8), P2 (1423)

For example: K23 (5500) = 5544

- –

- w =, r > 1 + h/2, α3 = 0, h = 3 in (8), P2

Od (n′) = (9 9 α1 10-α1 α2-1 9-α2)

K24 (α1 α2 0) = (α2 10-α2 2α1-10), 5 ≤ α1 ≤ 9, 5 ≤ α2 ≤ 9, α1 + α2 ≤ 11

With r ≤ 1 + h/2, functions differ from those with r >1 + h/2

- –

- w = , αh = 0, h = w/2 = 6 in(8), P3 = (6 1 7 2 3 8 9 10 4 5)

As an example of applying (15), we found:

n′ = 877,654,443,222, α′ = p (n′) = 655,310. Such α′ cannot be transformed with K1. It is a case w = 12, h = 6, α6 = 0 which can be transformed with the function

K25 (α ß γ δ ε 0) = (10- ε 9-δ α-ε-1 α + ß-9 γ-δ ß-γ),

α >1, α ≥ ß + 1, α + ß ≥ 9, 9 ≤ α+ δ ≤ 10, α + ε ≤ 9

α + δ-ε ≤ 10, ß + δ ≤ 9, ß + ε ≤ 8, 2γ ≥ ß + δ, γ ≥ 5, δ ≥ ε + 1, α + ß + δ-γ ≥ 9, ε ≥ 1

This function is associated with the aforementioned permutation P3, in a specific case of (8)

f2 (α ß γ δ ε 0) = (α ß γ δ ε -1 9 9 9-ε 9-δ 9-γ 9-ß 10-α),

f2 (655,310) = 655,309,986,444, K25 (655,310) = 964,220

- (4)

- Functions Ki based on (10)

As previously stated, when the number of digits is odd, w = + 1, h = (w-1)/2, function f2 is similar to the one corresponding for numbers with w = , but it includes one more 9 as a middle digit in the transformed number.

Such an addition does not alter functions Ki if r ≤ 1 + h/2, αr = 0, although it does change the last parameters of α′ if r > 1 + h/2.

In parallel with the cases considered in (3):

- –

- α3 = 0, w = 7, h = 3 in (10) and P1 (1234)

K26 (α1 α2 0) = (α1-1 α2 10- α2), 5 ≤ α1 ≤ 9, 5 ≤ α2 ≤ 9, α1 ≥ α2 + 1

- –

- α3 = 0, w = 7, h = 3 in (10) and P2 (1423)

K27 (α1 α2 0) = (α2 10- α2 α1-1), 5 ≤ α1 ≤ 9, 5 ≤ α2 ≤ 9, α1 + α2 ≤ 11

which is also a closer expression to K23 than to K24

- (5)

- Functions Ki based on (12)

There are only two functions Ki based on (12):

valid both for w = with h = w/2 and for w = + 1 with h = (w-1)/2

Table 1.

Some functions Ki in A6, w = 6, h = 3.

Table 2.

Some functions Ki in A7, w = 7, h = 3.

5. Balance: Transformation Constants

Let balance exist when there is an αE and a Ki(α) such that Ki(αE) = αE or, equivalently, K (nE) = nE, p (nE) = αE.

As a corollary, (nE) = nE, (αE) = αE, ∀r ≥ 1.

Let nE be called transformation constant and αE parametric constant. If all the numbers n Aw, by reiterating their transformation they become nE; we will say that nE is a Kaprekar constant. This is equivalent to the existence of a constant and a one-component scheme in Aw.

A transformation constant is a single-link cycle, which is why some authors call the constant a one-cycle [4]. Others call it a fixed point [5,12,13]. In relation with this fixed point and with the cycles, in general, the classic work of Prichett et al. [4] and the more recent, innovative input of Yamagami [10,11] and Bajorska-Harapinska et al. [19] should be highlighted.

In the example of (4), we see how 631,764 transforms into itself, and the same is true for α = p(n) = 632, K(632) = 632. Therefore, 631,764 = nE and 632 = αE.

The constants in base 10 have been exhaustively studied by Prichett et al. [3,4], who showed that in base 10, there are only two Kaprekar constants, 495 in A3 and 6174 in A4. They also determined one-cycles for different w-digits.

Our objective in this section is not to make a detailed study of the constants, but to show how families of constants can be derived directly from the Ki functions. In this regard, we show two examples: the family αE = 6 3 3 2 in w = 2 h, h ≥ 2 and the family αE = 8 6 4 3 3 2 in w = 2 h + 1, h ≥ 7. We also show two singular constants, αE = 550 in A6 and αE = 5 in A3.

Constants nE = 633176 64, αE = 63 32, w = 2 h

Indeed, Od (nE) = 76 6643 31 and Ou (nE) = 13 3466 67

For this expression to be valid, at least the two extreme digits and the two middle digits must be present. Such is the case with 6174, which is the renowned Kaprekar’s constant [1]. The associated parametric constants are αE = 63 32.

Such constants, which generalize Kaprekar’s constant for w-digits, w = , derive from function (18) associated with permutation P3 (h + 1 1 h + 2 … w 2 3 … h)

with the restrictions imposed in K3. There is a unique solution which is αE = 6 3 3 2

K3 (α) = α → α1 = 10-2αh, α2 = α1-αh−1, α3 = 9-αh−1-αh−2 … αh = α1-α2-1

For instance, for w = 8, h = 4

K3 (α) = K3 (α ß γ δ) = (10-2δ α-γ 9-ß-γ α-ß-1)

1 ≤ 10-2δ + α-γ ≤ 10; ß + γ ≤ 9; α ≥ ß + 1, α + γ ≥ 9, α ≤ 10 + γ-2δ, 1 ≤ δ ≤ 4

Imposing the equality condition

α = 10-2δ, ß = α-γ, γ = 9-ß-γ, δ = α-ß-1, there is only one solution: α = 6, ß = 3, γ = 3,

δ = 2 → αE = 6332, which satisfies the existence conditions and f1 (6332) = 63,317,664 = nE.

In the case where w = 4, h = 2, P3 = (3142), and the associated function is

K3 (α ß) = (10-2ß 2α-10) α ≥ 5, α + ß ≤ 9

K3 (α ß) = (α ß) → α = 10-2ß, ß = 2α-10 → α = 6, ß = 2

f1 (6 2) = 6174, which is Kaprekar’s constant.

This family of constants cannot exist if w = + 1, since a 9 being present in (6) completely changes function K3. It is not valid for w = 2 either, since permutation P3 does not make sense.

Constants nE = 8643 31,976 532, αE = 8643 32, w = 2 h + 1, h ≥ 4

They are derived from the function (22) associated with the permutation

P4 (1 h+2 2 h+3…h+s 3 4…s 2h 2h+1), s = h + 1, h ≥ 4. De K4 (α) = α and taking into account the domain of existence of P4, it results in αE.

P4 (1 h+2 2 h+3…h+s 3 4…s 2h 2h+1)

Constant nE = 549,945 and αE = 550

Derives from K24 in A6 (Table 1)

α = ß, ß = 10-ß, 0 = 2α-10 → α = 5, ß = 5, γ = 0 ↔ αE = 550

f2 (550) = 549,945 = nE

This constant cannot be generalized.

Constant nE = 495 and αE = 5

This is the other Kaprekar’s constant. If w = 3, f1 (α) = (α-1 9 10-α) and O (n′), this allows for two permutations P12 = (9 α-1 10-α) and P21 = (9 10-α α-1) as well as two associated functions K1 (α) = (α-1) and K2 (α) = (10- α). αE = 5 results from K2 (α) = α and f1 (5) = 495. It is thus another constant that cannot be generalized.

There are other functions of just one parameter. Such is the case of

- –

- w = 2 with f1 (α) = (α-1 10-α) and two functions Ki,

K1 (α) = (2α-11) and K2 (α) = (11-2α), which obviously cannot satisfy the condition

Ki (α) = α. In A2, there cannot be any transformation constant.

- –

- The same is true for functions

where condition K (α) = α leads to impossible results. In these cases, there cannot be any transformation constant either.

6. Cycles: Terminology and Functions (α)

There is a cycle of r links if and only if there are r parameters αci and r functions

Kci (α), such that Kci (αci) = αci + 1 being αci = αcj ↔ i ≡ j (mod r).

This amounts to the existence of r operators such that (αci) = αci, i = 1 …r.

In terms of numbers, it demands the existence of r numbers

Let us analyze the case A6 for six-digit numbers. The parametric transformation schemes are shown in Scheme 1.

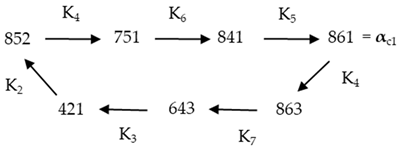

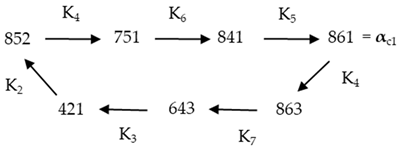

Main component A, consisting of 201 parametric classes out of the 219 existing classes, is articulated on a seven-class cycle, which can be conventionally called

861= αc1, 863= αc2, 643 = αc3, 421 = αc4, 852 = αc5, 751 = αc6, 841 = αc7

Each class becomes the following one with the functions in Table 1, indicated in the diagram:

Naturally, there are seven operators , r = 1, 2 … 7, which transform parameters separated by r links. Thus,

Any operator (αci) built with s > 7 will coincide with other (αci) 1 ≤ t ≤ 7 if and only if s ≡ t (mod 7). The existence of the cycle demands the coupling between functions Ki. The image of one function must belong to the domain of existence of the following one.

In numerical terms, the cycle consists of the following numbers

nc1 = 840,852, nc2 = 860,832, nc3 = 862,632, nc4 = 642,654, nc5 = 420,876, nc6 = 851,742,

nc7 = 750,843, being p (nci) = αci.

In A2, there is a five-link cycle. In A3 and A4, there is only one articulated on a Kaprekar’s constant. In A5, there are two four-link cycles and one two-link cycle.

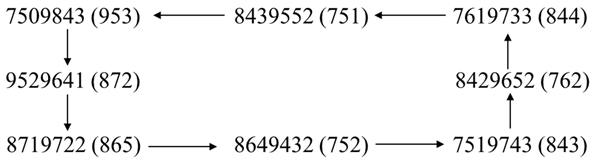

In A7, consisting of seven-digit numbers, all 219 existing parametric classes (α ß γ) group with the following cycle formed by eight links:

7. Symmetries

7.1. Equivalence Relations

Let two numbers m and n be equivalent Rr of order r if and only if

Since (m) = [K(m)], the following recurrence equations are found:

m Rr n ↔ K(m) Rr-1 K(n) r ≥ 1

Note that if two numbers are equivalent, they are so for any equivalence of a higher order:

m Rr n → m Rr + s n s ≥ 0

It is necessary to distinguish new equivalences Rr, those which are not of a lower order:

from old equivalences aRr, those that are also of a lower order:

m (aRr) n→ m Rr-1 n r > 0

The notation Rr does not specify whether an equivalence is new or old.

Equivalence of an order are binary equivalence relations that have the following features:

symmetry m Rr n ↔ n Rr m ∀ m,n

transitivity m Rr n and n Rr q → m Rr q ∀ m,n,q

They allow for numbers to be grouped in equivalence classes of order r:

These equivalence classes are pairwise disjoint, and their intersection is set Aw, generating a partition in Aw.

Because two numbers that are equivalent are so for any equivalence of a higher order (35), classes Cr include both the new and old equivalences. This hierarchical and inclusive feature of binary relations Rr is essential to better understand the convergence of this process.

Cr = {m,n ∈ Aw, m Rr n}, aCr = { p,q ∈ Aw, p Rr−1 q} Cr = Cr ∪ aCr

The transitive feature and relation (35) yield

m Rr n and n Rr + s q → m Rr + s q s ≥ 0

In our methodological approach to the analysis of the Kaprekar process, it is essential to extend the concept of equivalence Rr defined between numbers to sets of numbers with images in common, to equivalence classes.

Considering the last relationship, if

n ∈ and q ∈ results n Rt q. This is due to the univocal character of the transformation. All numbers belonging to a class Cv have the same image in the v-th transformation. From here on, any subsequent transformation will have the same image. Consequently, the element that best represents the transformation is not the number, but the equivalence class. Thus, we can agree to define the equivalence relation between classes according to

The direction of the arrow to the left must be understood in the sense that if two classes y have a relation Rt, then all numbers m and n belonging to those classes have a relation Rt. In particular, it turns out

From relation (14), it follows that the C1 equivalence classes are defined by the parametric classes (we will return to this topic in Section 7.3). α represents the parameters of a number α = (α1 α2 … αh) = p(n) and also the set of numbers that has the same parameters. As what characterizes a class C1 are precisely these parameters, we can agree to specify each C1 by its corresponding parameters, being able to write = αi, if in the context there is no room for confusion. With this convention α has a double meaning: parameters of a number and a set of numbers with the parameters that are specified.

By extension, we say that two parametric classes α1 and α2 are equivalent to Rr if and only if the numbers with the respective parameters are equivalent:

α1 Rr α2 ↔ m Rr n, p(m) = α1, p(n) = α2

Expression (44) allows us to translate some of the previous relationships into a parametric class language. For example, from (43) it results

Going back to expression (14) and to definition (32), it results

To any equivalence Rr can be associated a function or operator er such that

with the domain of existence of Rr.

α1 Rr α2 ↔ er (α1) = α2

It is a kind of representation that facilitates notation of calculations.

7.2. Product of Equivalences

Applying an equivalence onto another one normally yields another equivalence. By using the usual representation of the product of functions

the domains of existence will have to be compatible. Thus, taking equivalences that will be later deduced

ei [ej (α)] = (ei x ej) (α) = ek (α)

However,

Moreover, the product is conditioned by restriction (3). Therefore, if α = (α ß γ),

α ≥ ß ≥ γ

(α) = ( × ) (α) = (α 9-ß 10-γ) not valid because it demands γ ≥ ß + 1, which contradicts (3).

Additionally, the other way around, the product of non-allowed equivalences can generate an allowed one. Thus,

In summary, the product of equivalences demands that the resulting equivalence’s domain of existence be determined.

7.3. Symmetries R0 and R1

Symmetry R0 has been conventionally defined as the non-transformation: m R0 n ↔ K0 (m) = K0 (n) ↔ m = n. Each equivalence class C0 consists of a single number. There are as many classes C0 as there are numbers belonging to AW.

Due to (14), symmetry R1 is the one containing those numbers with the same parameters which return the same number after one transformation. Therefore, parametric classes, understood as the set of numbers with the same parameters, match with equivalence classes C1. Scheme 1 shows all these classes and their transformations in the case of A6.

As these classes uniquely determine the image of any number belonging to them, they are an essential element when understanding Kaprekar’s routine.

7.4. Symmetries R2

R2 symmetries are those that exist between numbers whose transformed seconds coincide.

As a result of Rr definition (32)

m R2 n ↔ K2 (m) = K2 (n) and because of (46)

m R2 n ↔ p [K (m)] = p [K (n)]

7.4.1. Permutations of the Same Sequence

If two numbers m and n, p(m) = α1, p(n) = α2 return images with transpositions of digits compatible with belonging to Bw, the ordered sequences will be identical Od (m′) = Od (n′) and their parameters will match α′1 = α′2, as will their numeric images

m″ = f (α′1) = f (α′2) = n″, thus verifying the condition of m R2 n.

Not just any transposition is valid. Only those that respect the conditions (5) or (7) of belonging to Bw are valid.

R2 equivalences based on (4a) and (4b)

Od (m′) = Od (n′) and p (m′) = p (n′) ↔ α1 R2 α2

We used f1 corresponding to w = , (4). The result for w = + 1 does not change, since including a central 9 in the sequences of m′ and n′ does not modify the reasoning. Likewise, the symmetric digits can be transposed in relation to the middle ones, αs and 9-αs, s = 2, 3 … h-1, or the middle digits themselves, αh-1 and 9-αh, returning the following binary equivalences by simple transposition, where α1 = (α1 α2 … αh).

- –

- Equivalences α1α2, α2 = (10-α1 α2 …αh), α1 + α2≤ 10

- –

- Equivalences α1α2, α2 = (α1 α2 … αs−1 9-αs αs + 1 …αh), s = 2, …h-1

αs−1 + αs ≥ 9, αs + αs + 1 ≤ 9

For example: w = 11, α1 = 76,632, α2 = 76,332

f1 (α2) the permutation P = (1 2 9 4 5 6 7 8 3 10 11) of f1 (α1) and K (α1) = K (α2) = 84,433 consistent with (48). Besides, f1 (8 4 4 3 3) = (8 4 4 3 2 9 6 6 5 5 2) =

f1 (α1) = 76,631,976,333, f1 (α2) = 76,331,976,633 being

= K (7 6 6 3 1 9 7 6 3 3) = K (7 6 3 3 1 9 7 6 6 3 3).

- –

- Equivalences α1α2, α2 = (α1 α2 …αh−1 10-αh), αh−1 + αh≥ 10

However, multiple transpositions are limited by (3):

- –

- Non-equivalence α1α2

αs + r−1 ≤ 9- αs and αs + r−1 ≥ 9-αs + r

αs + r ≥ 9- αs + r−1 ≥ αs → αs + r = αs = αs + i, i = 0, 1, … r

9- αs ≥ αs → αs ≤ 4 → αs + r−1 = αs + r ≤ 4

- –

- Non-equivalence α1α2

αh−1 ≤ 9- αs and αh−1 ≥ 10-αh

αh ≥ 10- αh−1 ≥ 10-(9- αs) = 1+ αs, impossible, since αh ≤ αs

- –

- Equivalence α1α2,α2 = (10-α1 α2 … αh−1 10-αh) → α2 = (5 5) = α1

It is a specific identity solution:

- –

- Equivalence α1α2, α2 = (α1 … αs−1 9-αs … 9-αs + r αs + r+1 αh)

According to (3), 9- αs ≥ 9-αs + r → αs + r = αs

Domain of existence:

αs ≥ 9- αs − 1, αs + r + 1 ≤ 9- αs + r, αs + i = αs, i = 0, 1 … r + 1, 2 ≤ s <h

For example: w = 10:

α1 = 75,552 and α2 = 74,442, f1 (α1) = 7,555,174,443, f1 (α2) = 7,444,175,553, where f1 (α2) is the permutation P = (1 9 8 7 5 6 4 3 2 10) of f1 (α1) and K (α1) = K (α2) = 64,111 according to (48).

- –

- Equivalence α1α2, α2 = (10-α1 α2 9-α3 … 9-αr αr + 1 αh)

9-α3 ≤ α2 ≤10- α1→ α2≤ α3≥ α1-1→ α1= α2 = α3 = 5

Domain of existence:

αs = 5, s = 1, 2…r, αr + 1 ≤ 9- αr

For example, α1 = 555,532, α2 = 554,432, w = 12:

where f1 (α2) is a permutation P = (1 2 10 9 5 6 7 8 4 3 11 12) of f1 (α1) and K (α1) = K (α2) = 631,110.

f1 (α1) = 555,531,764,445, f1 (α2) = 554,431,765,545

- –

- Equivalence α1α2, α2 = (10-α1 9-α2.…9-αr αr + 1 αh)

α1-1 ≤ α2 ≤ α1, αs = α2, s = 2, 3, … r

For example: w = 9, α1 = 8772, α2 = 2222:

f1 (α1) = 877,197,222, f1 (α2) = 222,197,778, where f1 (α2) is the permutation

P = (9 8 74 5 6 3 2 1) of f1 (α1) and K (α1) = K (α2) = 8655.

R2 based on (8) or (10)

If we consider αr as αh, the previous equivalences are valid. For example,

R2 based on (12)

Only the transposition of extreme digits is possible. That is, if

which is a permutation of the same digits compatible with (13), so

Od [f3 (α1)] = Od [f3 (α2)] ↔ α′1 = K (α1) = α′2 = K (α2) ↔ α1 R2 α2.

- –

- Equivalence (α 00)(11-α 00), α≥ 2

Example: α1 = 300, α2 = 800, α1 R2 α2 since K (α1) = K (α2) = 720.

7.4.2. Permutation of Different Sequences

There are equivalences where the digits from the sequence do not necessarily remain.

- –

- Equivalence α1α2

α1 = (α1 α2 … αh), α2 = (10-αh 9-αh−1 9-αh−2 … 9-α3 9-α2 10-α1),

Under (15) K1 (α1) = (2-10 2-9 … 2-9 2-10).

Under (17) K2 (α2) = (10-2 9-2 … 9-2 10-2).

If K1 (α1) = K2 (α2) → + = 10, + = 9, s = 1, 2, … h-2.

Note that α1 + Ou (α2) = (10 9 9 10).

For example,

α1 and α2 verify the equivalence, and f1 (α) corresponds to (4). m′ and n′ do not keep the same digits, but p (m′) = p (n′) = 84,331 and K2 (m) = K2 (n) = 8,433,086,652. This answers the second question in the introduction.

m = 8,178,382,562, p (m) = α1 = 76,641, m′ = f1 (α1) = 7,664,085,333

n = 4,774,473,809, p (n) = α2 = 95,333, n′ = f1 (α2) = 9,533,266,641

This equivalence, contrary to what happens with the previous ones, is not valid for odd w. In the previous example, w = 10. Let w = 11 and keep the same parameters p (m) = α1 = 76,641, p (n) = α2 = 95,333.

Now, the function f1 that must be used is the one corresponding to (6):

which are similar to the previous ones but with a 9 in the middle position:

m′ = f1 (α1) = 76,640,985,333, n′ = f1 (α2) = 95,332,966,641

p (m′) = 95,432, p (n′) = 87,332.

Adding a 9 in the sequence of digits makes symmetry break.

This equivalence may generate permutations of digits from the same sequence. Such is the case of α1 = 87,662 and α2 = 83,322, α1 α2.

being Od (m′) = Od (n′). It is just a numeric coincidence, even if for these parameters does not match any of the previous equivalences.

m′ = f1 (α1) = 8,766,173,322, n′ = f1 (α2) = 8,332,177,662

is a very common equivalence given the few restrictions of its domain of existence.

The product of equivalences × creates a family of derivative equivalences. Table 3 shows the equivalences R2 common in A6 and A7, and Table 4 shows derivative equivalences in A6. The superscripts in the equivalences are simplified by using correlative natural numbers. corresponds to a double translocation and to a triple one, but none of them are an equivalence.

Table 3.

Equivalences R2 with three parameters, α = (α ß γ).

Table 4.

Derivative equivalences in A6, α = (α ß γ).

Some of these derivative equivalences are not reciprocal, but

α1 α2 → α2 R2 α1, because K (α1) = K (α2). Thus, there is always another such that α2 α1.

- –

- Equivalence α1α2, α1 = (α 0 0), α2 = [(α + 9)/2 (19-α)/2 5], α = 5, 7, 9, w =

Indeed, under (30), K31 (α) = (-1 10- 0 0) under (15) with (16),

K1 ( ) = (2-10 2-9 … 2-9 2-10).

- –

- Equivalence α1α2, α1 = (α 0 0), α2 = [(10-(α/2) 4 + (α/2) 5], α = 2, 4, 6, w =

This results from using K32 (α1) instead of K31 (α1).

As a consequence, 200 955, 400 865 and 600 775.

Note that classes 100, 300 and 800 are excluded from . Class 100 does not have an equivalent R2 different from itself and 300 .

Equivalences and do not operate on numbers with w-digits, w = + 1.

- –

- In Aw, w = + 1, there are specific equivalences R2, unshared with w = . However, such R2 vary with w, and thus general expressions do not exist. Table 5 shows all those existing in A7 and A5. Some of these equivalences, such as , also generate equivalences R2 from the same sequence, e.g., 977 R2 973. Furthermore, if the domains of existence of Ki and Kj have classes (α ß γ) in common, they generate equivalences R1.

Table 5. Equivalences R2 in Aw, w = + 1, not found in w = .

Table 5. Equivalences R2 in Aw, w = + 1, not found in w = .

7.4.3. Equivalence Classes C2

Equivalence classes C2, which include numbers whose second transformations match, are an essential element in understanding the architecture of transformation trees. As an analogy, were parametric classes C1 the leaves of a tree, classes C2 would be the little branches that group the leaves together. The existence of equivalences R2 contributes to new branches in the transformation schemes by means of cycles.

In Table 6, equivalence classes C2 in A6 are shown. Some classes C1 do not have equivalent R2, such as 555 , but others have up to 5 equivalents. Such is the case of : any class 863, 833, 762, 732 and 332 belonging to it will become 643. Additionally, any number belonging to such classes will return the same image (642,654) after two transformations. In this example, 863 = αc2, 643 = αc3 and 642,654 = nc4.

Table 6.

Equivalence classes C2 in A6.

Scheme 2 shows the transformations of classes C2 in A6. When compared to Scheme 1, the structure of schemes stands out.

Scheme 2.

Transformation scheme of equivalence classes C2 in A6.

7.5. Groups of Equivalence R2

In theory, transpositions in those sequences compatible with the transformation functions should form subgroups of symmetric group Sh of all h-element possible permutations. This should be true for the product of those equivalences in Set I based on (4) or (6), those in Set II based on (8) or (10) and those in Set III based on (12).

However, generally speaking, this is not true for sets I and II. This is due to the fact that as h increases, some multiple transpositions are forbidden by (3). Such is the case of discussed in Section 7.4.1. Specifically, for A6 and A7, the product of equivalences e2 and transpositions n2 of Set I are shown in Table 7. Apart from the general associativity in the products of transpositions, as well as the existence of the neutral element , it is also worth noting the involutory ↔ features. However, the product is no longer a closed binary relation between equivalences, since the product of some of them returns , which although being transpositions, are not equivalences.

Table 7.

Product of equivalences R2 in A6 and A7 based on the transposition of digits from the same sequence. (f × g) (α) = f [g (α)]. (Equivalences e2 are defined in Table 4).

As h decreases, the forbidden general multiple transpositions disappear, and all transpositions generate equivalences. This happens when there are two non-null parameters—classes (α1 α2 00) from Set II and (α1 α2) from Set I with h = 2. Table 7 (Group II) shows the product of equivalences for A6 and A7. The same is true for the four equivalences of Set I in A4 and A5. The product of the equivalence in these cases has an isomorph group structure of Klein group. This group is characterized because all of its elements coincide with their inverses. In addition, it is a subgroup of the symmetric group S4 of all four-element possible permutations.

When the number of non-null parameters decreases to 1, a cyclical subgroup isomorphic to ℤ2 appears. Such is the case of the general equivalence (Section 7.4.1). Table 7 (Group III) shows the products for and This situation also occurs in and .

Naturally, any involutory equivalence, along with the identical, form a group isomorphic to ℤ2. Such is the case of in A6, which in this case does not exist in A7. However, its derivative functions (Table 4), along with the equivalence itself, do not have a subgroup structure, since the product of the former generates equivalences of Set I.

7.6. Symmetries R3 and Higher

From (44) and (33) it results

α1 Rr α2 ↔ α′1 Rr-1 α′2, α′1 = Ki (α1), α′2 = Kj (α2)

Specifically: α1 R3 α2 ↔ α′1 R2 α′2

One of the approaches to obtain the algebraic expressions of equivalences R3 is based on this expression. If an equivalence R2 is imposed on the images of two classes α1 and α2, Ki (α1) and Kj (α2), the result will be an algebraic relation between α1 and α2 so that α1 R3 α2:

(e2 x Ki) (α1) = Kj (α2)

As a few examples, we introduce the following equivalences:

Equivalence α1α2, α1 = (α1 α2 … αh), α2 = (15-α1 α2 … αh)

For example, in A6:

Which provides the following equivalences:

or in terms of classes C2, for (45)

Equivalence α1 α2, α1 = (α1 α2 …αh), α2 = (α1 α2 …αh−1 15-αh)

For example, in A6:

Equivalence α1 α2, α1 = (α1 α2 … αh), α2 = (α1 α2 … αh−1 28-2αh − 1-αh)

derives from × K1 (α1) = K1 (α2).

For example, in A7:

Equivalence α1 α2, α1 = (α 0 0), α2 = [1/2 (21-α) 5 5]

Equivalence R3 is often limited to a couple of classes. Such is the case of

which entails γ2 = ß2, α1 = 9, α2 = 6, and since K7 demands 5 ≤ ß ≤ 8 y 2 ≤ γ ≤ 5 → γ = ß = 5.

The equivalence is reduced to 900 655.

This situation becomes generalized when increasing the order of the equivalence. Thus, in A7:

Equivalence α1 α2, α1 = (α ß γ), α2 = (α 48-4α-ß + 2γ γ)

derives from x K4 (α1) = K4 (α2), only valid for 981 961, which answers another of the questions in the introduction:

5,068,069 R4 3,071,934 because p(5,068,069) = 981 and p(3,071,934) = 961

Equivalence 533 621

Indeed, (533) = (621) = 864. Or, equivalently, m = 4,687,437, p(m) = 533, n = 4,693,554, p(n) = (621), (m) = (n) = 8,639,532 → m R7 n.

However, the algebraic relation between 533 and 621, or between m and n, as in the two previous examples, is not extendible to other classes α1 R7 α2.

As order r of equivalence Rr increases, it is less interesting to establish the determining algebraic relation.

7.7. Symmetries and Cycles

The schemes are articulated on the cycles, whether they have several links r or only one (transformation constants).

Equivalence classes Cr group numbers with the same image Cr-1. In general, α1 Rs α2 ↔ α′1 Rs-1 α′2. For example, classes C1 963, 933, 761, 731 and 331 all belong to because their image is the same, 843 (Table 6). Analogously, and belong to the same class C5 because they have the same image (Scheme 3). This relation forces the transformation tree to swallow the leaves and little branches as s increases, and therefore, only the big branches and the trunk remain visible, using an analog language.

Scheme 3.

Transformations between equivalence classes C4 in A6. (C3 are included in component B, while C1 appear in component C).

The absorption process occurs in the whole scheme as well as in the cycles. The latter act as black holes that swallow those classes converging with them. Each class (ci) from the cycle groups with classes Cs which have (ci + 1) as an image from the cycle, resulting in a new class (cj). The process continues until Cs = Cs + 1 for all classes Cs in the scheme. This way, we reach the top of new equivalences Rs = Ru, where there are only as many classes Cu as there are links r in the cycle,, i = 1, 2, … r.

Each class belongs to the cycle and groups all classes Cs, s = 0, 1, 2…u-1, whose distance (number of transformations) to αci is a multiple of r. Thus, the number of links in the cycle establishes the distance pattern for the subsequent groups.

For instance, Table 8 shows the seven classes resulting from u = 13 transformations in component A from A6. As stated several times, component A has a cycle of r = 7 links. Class 661 ⊂ ⊂ and αC1 = 861 ⊂ ⊂ (Table 6). Class 661 needs 14 (2 x r) transformations to become 861—the same number of transformations that needs to reach (Scheme 2) or to reach (Scheme 3). Class 430 only requires r = 7 transformations.

Table 8.

Inclusion relations C2 ⊂ C4 ⊂ C13 in A6.

8. Discussion

We understand symmetry as invariance during transformation. This has been the aim of this paper, trying to understand why sets of different numbers return identical images, not only with a single transformation, but with any number r of them. To this end, here, binary equivalence relations of order r were used. Two numbers m and n present an equivalence relation m Rr n if and only if (m) = (n). This simple relationship allows the numbers to be grouped into Cr equivalence classes such that all their numbers give the same transform after r transformations. The use of these equivalences together with the complete parameterization of the transformation by means of Ki functions enabled us to find algebraic relations which explain the invariance of transformations.

The first step was to parameterize numbers. Any number n can have some parameters α which determine its image. We established the general functions f that conduct such transformation f (α) = n′, n′ being the image of n under Kaprekar’s routine. These functions are similar to those established by (4). From here, equivalence classes of order 1 arise—those consisting of numbers with equal parameters and give the same transformed. The transformed numbers are multiples of 9 that satisfy some strict requirements. We analyzed this aspect in detail, as it conditions the existence of symmetries.

The second step was to determine the parameters α of the transformed number. Here lies one of the main problems with transformation. The transformed number need not have its digits sorted in ascending or descending order, which is a prerequisite to determine its parameters. The permutation that arranges the digits must therefore be established. However, this is no easy task, since the number of permutations grows factorially as the number of digits increases. Once both the permutation and the domain of existence have been established, α′ is automatically defined. We established the procedure to construct the functions Ki (α) = α ‘, each one associated with a permutation. It is a novel contribution.

With these tools, we were able to approach equivalences Rr of a higher order. For this, the simple relation α1 Rr α2 ↔ α′1 Rr-1 α′2 can be very useful. Starting from equivalences R1, we can then move onto R2, R3, etc.

We showed that there are some R2—relations which must exist between numbers for their second transformation to match– that are universal. Those in sets I, II and III are valid for numbers with both an even number of digits (w = ) and an odd number (w = + 1). Others are only valid for w = . Thus, for example, the numbers whose parameters are α1 = (α1 α2 …αh) give the same numbers after two transformations as those with parameters α2 = (10-αh 9-αh−1 9-αh−2 … 9-α3 9-α2 10-α1), a1 ≥ a2 + 1. It is a α1 R2 α2 valid for w = 2 h, that is, for numbers with an even number of digits. It is an involutional equivalence.

The products of equivalences I and II only have group algebraic structures for low values of w. The equivalences of set I, for w = 4 or 5, while those of set II, for w = 6 or 7. Therefore, the group is isomorphic of the Klein group. The equivalences of set III are universal, thus generating a group isomorphic to ℤ2. The reason why there are not any more groups lies in relation (3), which forces the parameters to be arranged. Many permutations violate this arrangement, resulting in transpositions without a domain of existence in the product of equivalences.

Recently, Bajorska-Harapinska et al. [19] showed interest in these algebraic structures. In the last section of their work, they made an attempt to introduce Kaprekar-style transformation in some algebraic structures. As an example, they defined two transformations in the spirit of Kaprekar on symmetric groups Sn.

The new higher equivalence classes demand increasingly narrow domains of existence. Their algebraic relation is often only valid for a few classes Ci. With this, they are less and less interesting as r increases.

The development of functions Ki allowed us to approach another feature of transformations—the relation between cycles and symmetries. Transformation schemes are articulated on cycles. They can be leafy or not. Thus, in A6, component A contains 201 classes C1 and it is articulated on a seven-link cycle. Component B contains 17 classes, and it is articulated on the constant 631,764, whose parameters are αE = 632. Component C only contains class αE = 550, whose numeric constant is 549,945. In A7, the 219 existing parametric classes are grouped on an eight-link cycle. How many classes make up a component of a scheme will depend on the structure of functions K1, or equivalently, on the compatibility between successive permutations. This compatibility varies with Aw.

Additionally, dependent on each Aw is the coexistence of cycles and constants—in A2, there is a single cycle, in A3 and A4, a scheme of one component with a constant (a Kaprekar constant), in A5, three cycles, in A6, one cycle and two constants, in A7, a single cycle, etc.

The structuration of the schemes in equivalence classes follows a grouping pattern mediated by the number of links in the cycle. This number establishes the “meter” of distances for the successive groupings of the equivalence classes.

In short, Kaprekar’s routine raised the issue of the uniqueness of its constants. Prichett et al. [4] showed that there are only two Kaprekar constants in base 10. Additionally, in this paper, we see that there are several unique facts. The basic transformation applied to numbers in base 10 forces not only the transformed number to be a multiple of 9, but also its digits to satisfy some strict requirements (5), (7) …. In many cases, such numeric and parametric restrictions (3) lead to uniqueness. The algebraization of Kaprekar’s routine has proven the existence of universal relations as well. Such is the case of some R2 symmetries and the existence of universal groups, such as the Klein group.

We hope that our contribution will help arouse interest in this and other numeric transformations.

9. Conclusions

The combination of binary equivalence relations and parametric transformation functions has made it possible to configure a methodology capable of identifying and characterizing symmetries. Thus, we found algebraic relationships that determine these symmetries. Of particular interest are the symmetries associated with R2 equivalences, that is, those that generate numerical invariance after two transformations. These equivalences, together with R1, are the most frequent. We highlight:

- (a)

- R2 equivalences corresponding to transformations of digits of the same sequence (type I)

α2 = (10-α1 α2….αh), α1 + α2 ≤ 10

α3 = (α1 α2 … αs−1 9-αs αs + 1 …αh), s = 2, …h-1 αs−1 + αs ≥ 9, αs + αs + 1 ≤ 9

α4 = (α1 α2…αh-1 10- αh ), αh−1 + αh ≥ 10

All the previous equivalences correspond to simple transpositions. Only the multiple transpositions indicated in the text are possible and they lead to , , y .

Type II

If α1 = (α1 … αr 0 0) then the previous equivalences are valid if we consider αr as αh. This gives rise to a family of equivalences .

Type III

If α1 = (α 0 0) then α1 (11-α 0 0), α ≥ 2.

All equivalences are general, regardless of the number of digits.

- (b)

- Equivalences R2 corresponding to permutation of different sequences.

stands out for presenting few restrictions. α1 α2

α1 = (α1 α2 … αh), α2 = (10-αh 9-αh − 1 9-αh − 2 … 9-α3 9-α2 10-α1)

α1 ≥ α2 + 1, w even and h = w/2

The R3 equivalencies explain the numerical invariance after scheme transformations. We highlight:

with many more restrictions than R2, as specified in the text.

α2 = (15-α1 α2… αh)

α3 = (α1 α2 …αh − 1 15-αh)

α4 = (α1 α2 …αh − 1 28-2αh − 1-αh)

More R3 and higher equivalences are shown in the article. In particular, all the existing R2 for w = 6 and w = 7 are shown.

The products of equivalences I and II only have group algebraic structures for low values of w. The equivalences of set I, for w = 4 or 5, while those of set II, for w = 6 or 7. Therefore, the group is isomorphic of the Klein group. The equivalences of set III are universal, thus generating a group isomorphic to ℤ2.

The length of the cycles—its number of links—are the pattern of distances which determines how classes are grouped around the cycle’s nodes.

Parametric transformation functions have also been useful for studying constants and cycles. We show how families of constants can be derived directly from the Ki functions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

To María José Díez, professor at the UPV, for her selfless help in the correction of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaprekar, D. Another solitaire game. Scr. Math. 1949, 15, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M. Mathematical games. Sci. Am. 1975, 232, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapenta, J.F.; Ludington, A.L.; Prichett, G.D. An algorithm to determine self-producing r-digit g-adic integers. J. Mathematik. Band 1979, 310, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Prichett, G.D.; Ludington, A.L.; Lapenta, J.F. The determination of all decadic Kaprekar constants. Fibonacci Q. 1981, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, B.L. Searching for Kaprekar’s constants: Algorithms and results. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2005, 18, 2999–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolan, S. A classification of Kaprekar constants. Math. Gaz. 2011, 95, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, T. Kaprekar constant revised. Int. J. Math. Arch. 2013, 4, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hanover, D. The base dependent behavior of Kaprekar’s routine: A theoretical and computational study revealing new regularities. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.06308v1 [math.GM]. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, D.S. Kaprekar phenomena. Proceeding Ropar Conf. RMS-Lect. Notes Ser. 2019, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagami, A. On 2-adic Kaprekar constants and 2-digit Kaprekar distances. J. Number Theory 2018, 185, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagami, A.; Matsui, Y. On 3-adic Kaprekar loops. JP J. Algebra Number Theory Appl. 2018, 40, 957–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, W. On 2-digit and 3-digit Kaprekar’s routine. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.09708. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, P.; Zeng, T. Maximum distances in the four-digit Kaprekar process. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11756v1. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Y. Mysterious Number 6174. 2006. Available online: https://plus.maths.org/content/mysterious-number-6174 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Peterson, K.; Pulapaka, H. The Kaprekar routine and other digit games for undergraduate exploration. J. Math. Sci. 2008, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, D.; Goldman, B. Kaprekar’s Constant. Math. Teach. 2014, 98, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrends, E. The mystery of the number 1089-how Fibonacci numbers come into play. Elem. Math. 2015, 70, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phoopha, N.; Pongsriiam, P. Notes on 1089 and a variation of the Kaprekar operator. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2021, 16, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Bajorska-Harapińska, B.; Pleszczyński, M.; Różański, M.; Szweda, M.; Witula, R. Generalizations of Kaprekar’s transformation and Kaprekar-style transformations. In Selected Problems on Experimental Mathematics; Wituła, R., Bajorska-Harapińska, B., Hetmaniok, E., Słota, D., Trawiński, T., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2017; pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, T.; Rohen, Y.; Saleem, N.; Devi, M.B.; Singh, A. Fixed Points of Generalized α-Meir-Keeler Contraction Mappings in Sb-Metric Spaces. Hindawi J. Funct. Spaces 2021, 4684290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).