Abstract

On a particular class of m-idempotent hyperrings, the relation is the smallest strongly regular equivalence such that the related quotient ring is commutative. Thus, on such hyperrings, is a new representation for the -relation. In this paper, the -parts on hyperrings are defined and compared with complete parts, -parts, and m-complete parts, as generalizations of complete parts in hyperrings. It is also shown how the -parts help us to study the transitivity property of the -relation. Finally, -complete hyperrings are introduced and studied, stressing on the fact that they can be characterized by -parts. The symmetry plays a fundamental role in this study, since the protagonist is an equivalence relation, defined using also the symmetrical group of permutations of order n.

2020 Mathematics Subject Classification:

20N20

1. Introduction

A congruence relation on an algebraic structure is an equivalence relation that is compatible with the given structure, that is, all operations of the structure are well-defined on the equivalence classes. The set of the equivalence classes forms the associated quotient structure, that, in the case of a group, is a quotient group, while in the case of a ring it is a ring. In algebraic hypercompositional structures, where the operations are substituted by hyperoperations (i.e., multi-valued operations), this role of the equivalences is played by the strongly regular relations. Such a relation is defined on a hypergroup by the property: if and , for , then, for any and any , there is . A strongly regular relation on a hyperring R is strongly regular with respect to both hyperoperations of R. The mathematical concept of hyperring was defined by M. Krasner [1] in 1956 in the same paper where the hyperfields were introduced in order to solve an important problem dealing with approximations of complete valued fields by sequences of such fields. This algebraic hypercompositional structure has a similar behaviour as a ring and it contains an additive part , which is a canonical hypergroup and a multiplicative one , that is a semigroup, while the multiplication is bilaterally distributive with respect to the addition. Besides, a Krasner hyperring is also known as an additive hyperring. There are also other types of hyperrings [2] and the most general one is the so called general hyperring, introduced by Vougiouklis [3], where both addition and multiplication are hyperoperations. A short review on the historical part, terminology and the importance of hyperrings is presented by Massouros [4] or Nakassis [5] in their expository papers. The quotient structure associated to a hypergroup modulo a strongly regular relation is a group. This is a strong relationship between hypergroups and groups, that permits to study properties of hypergroups using already known properties of groups. In 1970 Koskas [6] defined the -relation and its transitive closure on a hypergroup H, proving that it is the smallest (with respect to inclusion) strongly regular relation on H such that the quotient is a group. The idea was then extended to the class of hyperrings, where Vougiouklis [3] defined in 1990 a new strongly regular relation, the -relation, on a general hyperring, such that the quotient structure modulo the transitive closure is a ring. Both associated quotient structures modulo and are not commutative. That is why, new strongly regular relations were defined—first the -relation on (semi)hypergroups and then the -relation on a hyperring in order to obtained commutative quotient structures [7,8]. The same symbol was (unfortunately) used to define two different relations, one on hyperrings, and the other one on (semi)hypergroups. In order to avoid confusion, some authors, for example see Reference [9], which prefers denoting the strongly regular relation on hyperrings with capital and we also adopt this notation in our current study.

Because of their “fundamental role”, that is, connecting hypercompositional structures with the corresponding classical structures, Vougiouklis [3,10] named all these strongly regular relations fundamental relations. Thus a fundamental relation defined on a hypercompositional structure is the smallest equivalence (with respect to inclusion) so that the associated quotient is a classical structure of the same type of the hypercompositional structure. The fundamental relations and defined on a (semi)hypergroup H lead to a (semi)group and a commutative (semi)group as quotient structure, while the fundamental relations and on a hyperring are the tool to obtain a ring and a commutative ring, respectively. In 2017, Norouzi and Cristea [11] introduced a particular class of hyperrings where the fundamental relation is not anymore the smallest equivalence such that the associated quotient structure is a ring. On this type of hyperrings they defined the fundamental relation , smaller than , but with the associated quotient structure non-commutative in general. Thereby, the fundamental relation was introduced on such hyperrings, obtaining a commutative quotient ring [12].

On the other hand, all the above mentioned strongly regular relations are not transitive in general. Already in 1970 Koskas [6] had studied the transitivity property of the -relation on hypergroups by using the complete parts, that were used as open subsets of suitable topologies on hypergroups. So they play an important role in defining topological hypercompositional structures [13]. Inspired by these studies, in this article we first define the concept of -part on hyperrings and study it in comparison with the complete part, -part and m-complete part. In particular, we find conditions under which the relation is transitive and prove that the equivalence class, modulo the relation , of any element of a general hyperring is a -part. Finally, we introduce the class of -complete hyperrings, characterize them using the -parts and present their connections with complete, -complete, and -complete hyperrings.

2. Preliminaries on the -Relation on Hyperrings

This section contains the basic definitions and results concerning the -relation on hyperrings that will be used throughout the paper. For more details about hyperstructures theory, specially hyperrings, we refer the readers to References [3,10,14,15] and references therein.

Definition 1.

[15] An algebraic system is said to be a

- (1)

- (general) hyperring, if is a hypergroup, is a semihypergroup, and the hypermultiplication · is distributive with respect to the hyperaddition +. If is a semihypergroup, then is called a semihyperring.

- (2)

- Krasner hyperring, if is a canonical hypergroup and is a semigroup such that 0 is a zero element (called also absorbing element), that is, for all , we have , and the multiplication · is distributive over the hyperaddition +.

On a hyperring R, the -relation was defined by Vougiouklis [3] as follows:

Its transitive closure is the smallest strongly regular relation on R such that the associated quotient is a classical ring, but it is not commutative in general. Later on Davvaz and Vougiouklis [7] introduced the relation in order to obtain a commutative quotient ring. First set and then, for any natural number n, we say that if and only if there exist , a permutation and the elements and the permutations , for , such that and , where . Take then . The quotient structure is a commutative ring.

In Reference [11] the authors defined a new relation on (semi)hyperrings, denoted by , smaller than the -relation, such that its transitive closure on a particular class of hyperrings is the smallest strongly regular relation endowing the quotient set with a ring structure. Let us remember here its definition. Select a constant m, such that . For two elements x and y in R, consider if and only if , for , and . If is a hyperring such that is commutative and implies that there exists for such that for all , then the relation is the smallest strongly regular equivalence on R such that the quotient set is a ring (not necessary commutative). Besides, since the quotient ring is not commutative in general, similar to the role of the -relation, in Reference [12], a strongly regular relation, smaller than the -relation, was defined in order to obtain commutative quotient rings as follows:

A new type of hyperring was introduced, where the transitive closure is strongly regular. Their multiplicative part is commutative and they satisfy the condition—for any nonempty subsets of R and a permutation , if and , then there exist , for , such that

The quotient is always a commutative ring [15], while the quotient is not commutative in general [12]. Actually, if is an m-idempotent hyperring satisfying relation (2), then is the smallest strongly regular equivalence relation on R such that the quotient is a commutative ring. In Reference [12], it is shown that the four fundamental relations defined on hyperrings are not equal in general, but for all m-idempotent Krasner hyperrings, it holds . Moreover, it is proved that on m-idempotent hyperrings satisfying relation (2), which states that the relation is a new representation for the -relation on m-idempotent hyperrings satisfying relation (2).

3. -Parts and Transitivity of the -Relation

Generally, the -relation is not transitive [12], as well as the relations , , , or , so there is the necessity to find a tool, a method to show when these relations are transitive. Koskas was the first to deal with this problem, which was resolved in Reference [6] by introducing the notion of complete parts on (semi)hypergroups. A nonempty subset A of a semihypergroup is called a complete part of H, if implies , for any nonzero natural number n and any elements . In particular, the equivalence class of any element of H is a complete part of H.

The transitivity property of the -relation was studied by Anvariyeh et al. [16], using complete parts on hyperrings. A nonempty subset M of ahyperring is a complete part of R if from it follows that , for , and .

Next -parts [17] were introduced on hyperrings to show when the -relation [7] is transitive. A nonempty subset M of a hyperring R is an -part, if for every , , , and , there is

where .

Moreover, the m-complete parts [18] were defined with respect to the transitivity of the -relation. In this case, a nonempty subset M of R is an m-complete part if implies that , for a constant .

In this section, the -part of a hyperring R is introduced in order to establish a condition for transitivity of the -relation. In this regard, some properties of -parts and some of their differences from complete parts, m-complete parts and -parts are presented.

Definition 2.

Let M be a nonempty subset of a hyperring R. We say that M is an -part, if implies , for every , and .

To start with, a characterization of -parts is stated.

Proposition 1.

Let R be a hyperring. The following conditions are equivalent:

- (i)

- A nonempty subset M of R is a -part.

- (ii)

- For any with the property it follows that .

- (iii)

- For any with the property it follows that .

Proof.

Let M be a -part of R and for and . Hence there exist , and such that and . Since , it follows that and so .

Let such that . Thus there exist , such that , and . The following implications hold:

Now, let M be a nonempty subset of R. If , then there exists . For and every , we have . Thus and . By the hypothesis, it follows that and so . Therefore, M is an -part of R. □

Example 1.

Consider the hyperring as follows:

and define for every . Then, and for all . By Proposition 1, we can see that is a -part, but is not a -part of R, for any .

Proposition 2.

Every α-part is a -part, for every .

Proof.

Proposition 1 is similarly valid for the -relation and -parts ([15]). Therefore, the proof is completed because . □

In the following example we can see that the converse of Proposition 2 is not generally valid:

Example 2.

In the hyperring R defined in Example 1, the set is a -part, but it is not an α-part because , with , while and .

Proposition 3.

Every -part is an m-complete part, for every .

Proof.

It follows immediately by using in the definition of -parts. □

The following example shows that the converse of Proposition 3 is not valid. Moreover, we can see that .

Example 3.

On the set define the following hyperoperations

Then is a noncommutative semihyperring. Put , hence , for every . Thus, implies , and so is a 2-complete part of R. But, and so , while . Therefore, is not a -part of R. Moreover, we have and , which implies that .

It is easy to see that Proposition 1 is valid also to characterize complete parts with respect to the -relation on hyperrings. That is, a nonempty subset M is a complete part if and only if, for any such that it follows that , equivalently with, for any such that it follows that .

Example 4.

Consider the hyperring R in Example 1 and the subset . It can be seen that M is a complete part and also a -part, but is not an α-part, since , but .

Comparing the definitions of the complete parts and m-complete parts, it is easy to see that a complete part of every (semi)hyperring is an m-complete part. But the converse implication is not generally true [18]. Besides, from the following example, we can state that not all -parts are complete parts.

Example 5.

Consider the following hyperoperations on the set :

Then, is a semihyperring. We have for all , and . Hence, is an m-complete part and also a -part, but it is not a complete part of R since , but .

Example 6.

Consider the hyperring in Example 3, where is not a -part, but it is a complete part of R since .

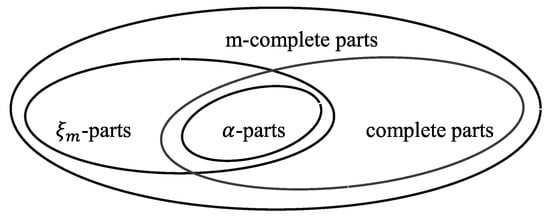

By the above mentioned examples about various type of complete parts in a hyperring, the connections between complete parts, m-complete parts, -parts and -parts in hyperrings may be represented as in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Generalizations of complete parts.

Theorem 1.

Let R be an m-idempotent hyperring (for ) satisfying condition (2). Then a nonempty subset M of R is a -part if and only if M is an α-part of R.

Proof.

By Proposition 2, every -part is a -part.

Now, let M be a -part such that , for , , , and arbitrary elements . Since R is an m-idempotent hyperring, it follows that for every , thus and

for every . Set and . Thus we have

and by condition (2) there exist (and ) such that . So and we have because M is an -part. Hence, , which means that M is an -part. □

Now we are starting the process of finding conditions under which the -relation is transitive. For this, first we define the following set for every element x in R and .

Then, we obtain a different characterization of the set .

Lemma 1.

, for every .

Proof.

For any arbitrary elements such that , there exist , and such that and . Thereby there exists such that , that is, . On the other hand, if , then there exists such that for , , and , which means that . This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.

Let R be a hyperring. If is transitive, then , for every .

Proof.

If is transitive, then . By Lemma 1, we have , equivalently with if and only if . □

The next result states a necessary condition for the set to be a -part of R.

Theorem 3.

Let R be a hyperring and . If , then is a -part of R.

Proof.

Let and such that and take . Hence, there exists such that which implies that . Then . Also, and thus . It follows that , implying that . This proves that is a -part of R. □

In the next result the transitivity of the -relation is discussed.

Theorem 4.

Let R be hyperring and . If is a -part, then is transitive.

Proof.

Let such that and . Since , by Lemma 1, it follows that . And using once again Lemma 1 we obtain , implying . Therefore, is transitive. □

Summarizing the above theorems we can discuss the transitivity property of the -relation on hyperrings by the next result.

Corollary 1.

Let R be a hyperring. Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (1)

- The -relation is transitive;

- (2)

- , for all ;

- (3)

- The set is a -part of R, for every .

4. -Complete Hyperrings

In this section, the concept of -complete hyperrings is introduced by meaning of the -relation and some characterizations are provided using properties of -parts. We present several examples that illustrate the fact that -complete hyperrings are different from -complete hyperrings and -complete hyperrings.

Let recall first the definition of n-complete hyperrings, -complete hyperrings and -complete hyperrings.

For an arbitrary natural number n, a hyperring R is said to be an n-complete hyperring ([17]) if

for all and .

R is called an -complete hyperring [17] if, for all , , and with , there is

where .

For any natural number m, , the hyperring R is an -complete hyperring if

for all and .

Similarly, we can define the concept of -complete hyperrings based on -relation as follows.

Definition 3.

For any natural number m, , we say that a (semi)hyperring R is -complete, if it satisfies the condition

for any , arbitrary elements and an arbitrary permutation .

Example 7.

Consider the hyperring in Example 1. We can see that

for arbitrary , and . So, R is a -complete hyperring.

Example 8.

Consider now the semihyperring in Example 3. Since and , it follows that and so

Therefore R is not -complete.

Corollary 2.

Every -complete hyperring is a -complete hyperring.

Proof.

Let R be an -complete hyperring. For all , take elements in R, the identical permutation, and . Then and , where . Hence,

Clearly, . This completes the proof. □

Generally, a -complete hyperring is not an -complete hyperring, as illustrated by the following example.

Example 9.

Consider the hyperring R in Example 1. We know by Example 7 that R is an -complete hyperring. Since we have , it follows that

Hence the hyperring R is not -complete.

For any m, , we say that a hyperring R is strongly m-idempotent, if , for every . It is known [12] that in any m-idempotent hyperring satisfying condition (2). Then, we can present the converse case of Corollary 2.

Theorem 5.

Any strongly m-idempotent hyperring satisfying condition (2) that is -complete is also an -complete hyperring, for every .

Proof.

Let R be a strongly m-idempotent hyperring satisfying condition (2) and such that R is -complete. For every , , , and , let . This means that there exists such that . Since R is a strongly m-idempotent hyperring, it follows that

Put and . Then, by condition (2), there exist for every (and for ) such that

Hence,

Therefore, . This concludes that R is an -complete hyperring. □

In the following, we discuss the relationship between -complete hyperrings and -complete hyperrings.

Corollary 3.

Every -complete hyperring is an -complete hyperring.

Proof.

The proof follows immediately from the definition of a -complete hyperring, taking the permutation . □

Clearly if R is a commutative hyperring, then we have and so any -complete hyperring is -complete. But the converse of Corollary 3 is not valid in general, as shown in the following example.

Example 10.

Consider the hyperring R in Example 3. By Example 8, we know that R is not a -complete hyperring. Besides we have or or or , for all and . On the other side, one founds that , , and . Hence, , meaning that R is an -complete hyperring.

We conclude this study with a characterization of -complete hyperrings based on the notion of -parts.

Theorem 6.

A hyperring R is -complete if and only if for all where , and .

Proof.

Let R be a -complete hyperring and take an arbitrary . Then

Moreover, if , then , because . Hence, and so .

Conversely, by hypothesis we have

Therefore, R is a -complete hyperring. □

Theorem 7.

Let R be a -complete hyperring for any m, . Then is a -part of R, for every , and .

Proof.

For and , let . Then there exists . For every , with , we have . Hence,

and there by which implies that is a -part of R. □

5. Conclusions

Ten years after the introduction of the fundamental relation in [7] on general hyperrings, Norouzi and Cristea [11] defined a new class of m-idempotent hyperrings satisfying a certain condition, where is no longer the smallest strongly regular relation such that the associated quotient structure is a commutative ring. For this reason, they introduced the -relation, as the transitive closure of the -relation, as a fundamental relation on such hyperrings. Since is not generally transitive, it is useful to find conditions under which the transitivity property holds, too. In this respect, the well-known tool of complete parts has been studied in this paper, but in a general form. After defining the -parts and presenting the relationships with complete parts, m-complete parts, and -parts, the study has focused on finding conditions when is transitive. The second part of the article has dealt with the study of -complete hyperrings and their connections with - and -complete hyperrings. The results have been supported by illustrative examples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.Z., M.N. and I.C.; Funding acquisition, I.C.; Investigation, A.A.Z., M.N. and I.C.; Methodology, A.A.Z., M.N. and I.C.; Writing original draft, A.A.Z. and M.N.; Writing review & editing, I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The third author acknowledges the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P1-0285).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krasner, M. A class of hyperrings and hyperfields. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1983, 6, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, V.; Jafarpour, M.; Hoskova-Mayerova, S.; Aghabozorghi, H.; Leoreanu-Fotea, V.; Bekesiene, S. Derived Hyperstructures from Hyperconics. Mathematics 2020, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougiouklis, T. The fundamental relation in hyperrings. The general hyperfield. In Algebraic Hyperstructures and Applications (Xanthi, 1990); World Sci. Publishing: Teaneck, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Massouros, C.G. On the theory of hyperrings and hyperfields. Algebra Log. 1985, 24, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakassis, A. Recent results in hyperring and hyperfield theory. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1988, 11, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskas, M. Groupoids, demi-hypergroupes et hypergroupes. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1970, 49, 155–192. [Google Scholar]

- Davvaz, B.; Vougiouklis, T. Commutative rings obtained from hyperrings (Hv-rings) with α*-relations. Comm. Algebra 2007, 35, 3307–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freni, D. A new characterization of the derived hypergroup via strongly regular equivalences. Comm. Algebra 2002, 30, 3977–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Nozari, T. A new characterization of fundamental relation on hyperrings. Int. J. Contemp. Math. Sci. 2010, 5, 721–738. [Google Scholar]

- Vougiouklis, T. Hyperstructures and Their Representations; Hadronic Press Inc.: Palm Harbor, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, M.; Cristea, I. Fundamental relation on m-idempotent hyperrings. Open. Math. 2017, 15, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adineh Zadeh, A.; Norouzi, M.; Cristea, I. The commutative quotient structure of m-idempotent hyperrings. An. Şt. Univ. Ovidius Constanţa 2020, 28, 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, D.; Davvaz, B.; Modarres, S.M.S. Topological hypergroups in the sense of Marty. Comm. Algebra 2014, 42, 4712–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, P. Prolegomena of Hypergroup Theory; Aviani Editore: Tricesimo, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Davvaz, B.; Leoreanu-Fotea, V. Hyperring Theory and Applications; International Academic Press: Palm Harbor, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anvariyeh, S.M.; Mirvakili, S.; Davvaz, B. Transitivity of Γ-relation on hyperfields. Bull. Math. Soc. Sci. Math. Roumanie 2008, 51, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mirvakili, S.; Anvariyeh, S.M.; Davvaz, B. On α-relation and transitivity conditions of α. Commun. Algebra 2008, 36, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, M.; Cristea, I. Transitivity of the εm-relation on (m-idempotent) hyperrings. Open. Math. 2018, 16, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).