Abstract

We solve the boundary value problem for Einstein’s gravitational field equations in the presence of matter in the form of an incompressible perfect fluid of density and pressure field located in a ball . We find a 1-parameter family of time-independent and radially symmetric solutions satisfying the boundary conditions and on , where is the exterior Schwarzschild solution (solving the gravitational field equations for a point mass M concentrated at ) and containing (for ) the interior Schwarzschild solution, i.e., the classical perfect fluid star model. We show that Schwarzschild’s requirement identifies the “physical” (i.e., such that and is bounded in ) solutions for some neighbourhood of . For every star model , we compute the volume of the region in terms of abelian integrals of the first, second, and third kind in Legendre form.

1. A Boundary Value Problem

The interior Schwarzschild solution (cf. K. Schwarzschild, [1])

provides a simple model of a star, shaped as a homogeneous sphere of incompressible fluid with radius . The Lorentzian metric (1) is a time-independent and radially symmetric solution to the boundary value problem for gravitational field equations

for nonempty space, whose matter and energy content is described by the energy-momentum tensor

where and p are the density and pressure fields, respectively, and is the exterior Schwarzschild solution, i.e.,

Lorentzian metric is only defined in the region of . In particular, it must be

Solutions to (2) and (3) are looked for in the form

where the unknown functions and are determined from the field equations under the additional assumption that the fluid matter is at rest, i.e., the components of the velocity four vector are with . If we set then

hence, becomes

(the energy-momentum tensor for the perfect fluid at rest). The nonzero components of the Ricci tensor of the metric (7) are

Then, scalar curvature is

Substitution from (8) –(12) into (2) turns (2) and (3) into the boundary value problem

where . There are but three independent field Equations (13)–(15), for Equations (2) with coincide. So, (13)–(15) is a system of ODEs with four unknowns and a physically reasonable solution should satisfy and . The addition of (13) and (14)

yields [for any physically reasonable solution ]. Let us eliminate p between (14) and (15), respectively differentiate (14), so that to obtain

Lastly, let us eliminate between (17) and (20) so that to obtain

which readily determines , provided that and p are known. The main result in [1] is that ODEs system (13)–(15) may be integrated under the additional assumption that the fluid is incompressible, i.e., constant. The assumption that is constant is justified by its advantages in the mathematical handling of Equations (13)–(15). Indeed, if , then (13) readily furnishes

where is a constant of integration. If then hence [by (7)] at i.e., the space-time described by g is singular on the 2-surface , at least from the nineteenth-century perspective adopted in [2] (pp. 1–3). To derive a solution without singularities of the sort, K. Schwarzschild chose (cf. [1]) (and then is readily determined from (22)). It is our purpose in the present paper to determine the remaining (a fortiori unbounded) solutions to the boundary value problem (13)–(16) corresponding to choices . Other interior Schwarzschild-type solutions were determined by P.S. Florides (cf. [3]), A.L. Mehra (cf. [4]), N.K. Kofinti (cf. [5]), and O. Gron (cf. [6], further generalizing the work in [3]). Let us set

so that (22) reads

Next, let us integrate (21) (under the assumption that is constant) to obtain

where is a constant of integration. Moreover, we eliminate between (24) and (17)

which may be written

Let us replace from (23) to obtain the following ODE with the unknown

By a change of dependent variable , Equation (26) may be written

For every and , we adopt customary notation , where . Let . To compute the integral in (29), let us consider the polynomial and set

We need to distinguish among the following cases: (I) , (II) , and (III) . In Case (I), one has and , while , and , . Moreover, set is

where . Consequently, one has the decomposition

where and (keeping in mind that and ). Next,

Hence,

where is a constant of integration (the general solution to (28)). For , the solution obtained in [1][i.e., the general solution to homogenous equation ] is

[coinciding with as given by (30)]. In Case (II), one has , , and set is

yielding the decomposition

so that once again

leading to (30). In Case (III),

and decomposes as leading to (30), i.e.,

The associated inhomogeneous equation (i.e., (27) with )

admits the obvious (constant) solution ; hence, the general solution to (32) is

The determination of a particular solution to (27) is a considerably more difficult problem, involving hyperelliptic integrals. Equation (27) reads

or ; hence, (by (30) with )

is a particular solution to inhomogeneous Equation (27). Hence, the general solution to (27) is

so that

Let be the metric tensor defined by (7) with and , respectively given by (23) and (35), i.e.,

(). Let us set and , so that

and then

As is customary, the constants of integration are determined by the boundary conditions that the coefficients of the Lorentzian metrics (36) and (5) coincide on , and (p vanishes at the boundary, so that it matches continuously with the zero pressure at the exterior of the fluid star). The identification of coefficients (in (36) and (5) at )

yields

This is equivalent to and yields

By taking into account and , we may rewrite (38) as

and density is determined [under the requirement of regularity (i.e., looking for a bounded solution ) (as in [1]), and the boundary condition (40) leads to

(determining )]. We are left with the determination of constants A and B in (36). To this end, let us return to (24) and substitute from (35) so that to obtain

which evaluated at gives (by the boundary condition )

or (by and together with (37))

or

Moreover, by identifying the coefficients (of Lorentzian metrics (36) and (5))at

or (by (42))

yielding

where . Let us substitute from (43)–(74) into (36)–(37) so that to obtain

For ,

Let us eliminate between (40) (with ) and so that to obtain

The calculation of the dimensionless quantity (46) for -Centauri and Sun (at the present age years, respectively, at age where Gyr) is reported in Table 1 (gravitational constant ·· and speed of light in vacuum ·).Let and be, respectively, Sun’s mass and radius at age t, so that kg and km.

Table 1.

Calculation of for Sun and -Centauri.

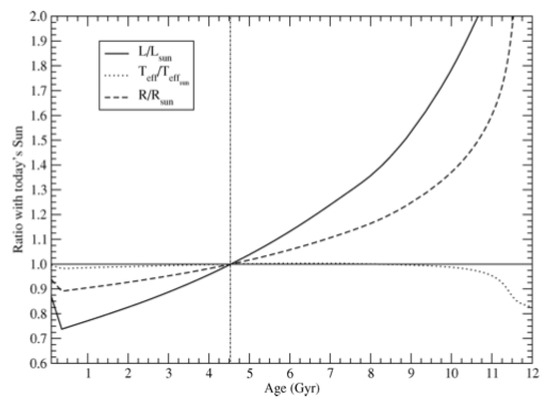

Data used for -Centauri are and (cf. e.g., [7]); after Gyr from present age. Dimensionless quantity decreases at later ages both as a function of (cf. Figure 1) and as a function of M (as Sun expels per year from emission of electromagnetic energy and ejection of matter with solar wind, cf. [8]).

Figure 1.

Evolution of the radius (effective temperature, and luminosity) of the Sun from the zero-age main sequence to the start of its red giant phase (cf. [9]).

(agreeing with (9.154) in [10] (p. 290)). Moreover,

hence,

(agreeing with (9.156) in [10] (p. 290)).

One has (with a satisfying (38))

hence

In particular, is only defined in (a region contained in) (and because of for any for the exterior Schwarzschild solution), so that

hence (the coefficient of ),

where . The hyperelliptic integral in (49) may be derived from the integral in (60), thought of as a parametric integral

while the calculation of the antiderivative in (60) is addressed in Appendix A.

2. Pressure Field

To fully solve the boundary value problem (13)–(16), one is left with the determination of pressure field . To this end, we recall (24), implying (by and ) that . Yet or (by (43))

yielding . Note that (by (6) and (39)) hence,

or

As a consequence of (40), where

Let us substitute from (52), (50) (with ) and (59) into (24). We obtain where

where we set

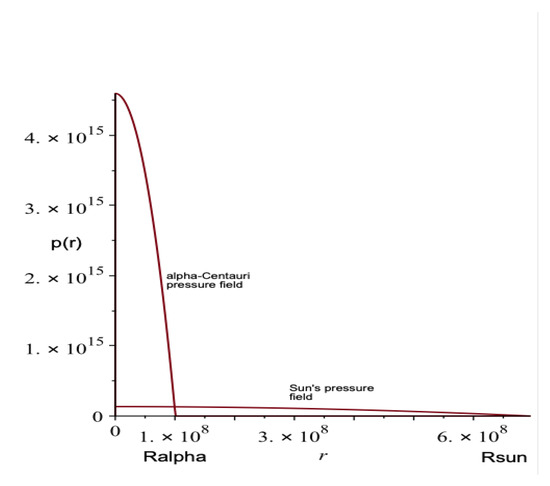

For , Formula (53) becomes

(expressing the pressure field in the case considered by K. Schwarzschild, cf. op. cit.) (see Figure 2). We prove the following theorem: the following statements are equivalent: (i) and (ii) there is an open neighbourhood of the origin , such that, for any , pressure field is a bounded function in the interval . With notations (54) and (55), pressure is bounded in if and only if for any . We first attack the implication (ii) ⟹ (i). In particular (under Hypothesis (ii)), is bounded in , yielding

where hence (56) is equivalent to

so that it must be or

which is (i). This is precisely the requirement (on structural parameters and M) discovered by K. Schwarzschild (cf. op. cit., or formula (9.163) in [10] (p. 292)) that ought to hold in order that pressure may never become infinite inside the fluid.

Figure 2.

Pressure fields and (Schwarzschild’s solution i.e., ).

To prove the implication (i) ⟹ (ii) is to show that the previous result persists under a small 1-parameter variation of about . Let us assume that requirement (57) is satisfied. Then, (56) holds, so that (as is strictly decreasing in )one has . Let us consider auxiliary function defined in . By the continuity of , property persists in some open neighbourhood i.e., or for any . Lastly, as is strictly decreasing in , we may conclude that

Q.e.d. As a corollary, we may show that the maximum domain of the “physical” solution (obeying to the requirements , , and is bounded in )is , for any . Here denotes the closed ball of radius and center .

Indeed, as and in , the domain is determined by the requirements , and . To compute , note first that and

Consequently, if i) then for any , while if ii) , there is a unique such that , for any , and for any .

3. Volume Calculations

The “true” physical density is not constant as an effect of curvature i.e., the metric (with ) varies in the fluid ambient, and the very notion of density depends on . To compute the “physical” density, let us set (the “physically meaningful” radial interval), i.e.,

Similarly, and . The “physical” volume element is then

Let us integrate in (59) over , and so that to determine the total volume

To compute V, we rely on considerations in Appendix A (reducing the underlying indefinite integral to the canonical Legendre form). Let us assume that

(yielding , and , with the notations in Appendix A). The first of the assumptions (61) yields , and (61) is then equivalent to , where is the only positive root of the polynomial . Indeed (by the boundary condition (38)) is equivalent (for positive a) to . Yet, , F is monotonously increasing in , and hence there is a unique , such that . Lastly, the last two requirements in (61) are satisfied for every . Next, note that

Indeed, starting from inequality (62) is equivalent to or (by replacing from ) where . Yet for any . Q.e.d.

Let us set

The domain of g is (cf. Table A1).Note that

(hence, integral in (60) is well-defined).To prove (63) one observes first that

The remainder of the argument is by contradiction. If , then (by (64)) or [again by ] [in contradiction with ]. As a corollary to (63)

where . Indeed

[by substitution from , and ]. As part of the reduction to the canonical form scheme one needs to apply a homographic change of variables under the integral sign. Yet the pre-images of are separated by the singularity ; hence, one needs to split (by taking into account (62))integral as and apply the transformations and , respectively. This leads to generalized integrals, so a bit of extra pedantry is needed to correctly apply change of variable theorems, i.e.,

where

with A) , respectively, B) . Here, [so that ]. Next, one decomposes into even and odd components, i.e., ; hence, (in Case (A))

(by with )

(where ] or [by , )

(where ) and

(by (A22))

where

Indeed, , , and

Lastly, (in Case (A))

or

with the Legendre notations

for the abelian integrals of the first, second, and third kind of module k. As to Case (B),

[by setting

[with or [by , ]

Note that and . Summing up our previous calculations

hence,

where

Thus,

and

Then (in Case (B))

Summing up (by (66)–(68))

Going back to (60), volume of region , whose geometry is governed by , is

In particular, for [as (38) with yields

This is the case examined by K. Schwarzschild (cf. op. cit.); practical evidence was previously gathered that ; hence, we may consider the truncated Taylor expansion of as a function of , i.e., for every

for some function such that lies between 0 and x, or

and

Estimate (71) follows from

Indeed, if for instance , then yields ; hence,

and , so that

i.e.,

Similarly,

and so that

Lastly, estimates (73)–(76) yield (72) for any . Of course, the use of (74) and (76) does not lead to an optimal estimate on ((72) is to be preferred only for its mathematical elegance).

4. Conclusions and Open Problems

In the present paper, we examined a fundamental issue, present in most textbooks nowadays on general relativity and gravitation theory, i.e., the derivation of the interior Schwarzschild solution (cf. e.g., [10] (pp. 280–295)) and the resulting simple model of a star. To determine (and actually where is the (constant) density and the (radial) pressure field), one looks for a line element of the form and needs to solve the boundary value problem (13)–(16) for . The general solution of the ODE system (13)–(15) contains three constants of integration , and the given boundary conditions determine the first two, while the third is but subject to the constraint . This leads to a 1-parameter family of solutions to (13)–(16) with the property that is bounded at if and only if . K. Schwarzschild discarded the solutions with on the ground that the determinant of each with vanishes at ; this is, of course, also the case for , and the question arises whether any of the additional solutions is physically acceptable, thus leading to alternative geometric descriptions of the interior of a star of incompressible fluid. We explicitly determine the solutions and show that the requirement (57) i.e., , which in Schwarzschild’s work is equivalent to staying finite in , is also equivalent to the boundedness of in , though only for a lying in some open neighbourhood of . It should be observed that estimate (6) i.e., is slightly improved by estimate (57); and , so that the requirement (57) provides a slightly smaller upper bound on the amount M of fluid that can be packed into a ball of radius , in agreement with the geometry of space-time as described by the Lorentzian metric . K. Schwarzschild used metric tensor to compute the volume of the region

and derived the truncated Taylor development of with respect to the parameter

When the geometry is described by , the parameter is , as may be argued by invoking experimental evidence, and development (77) gives a fair approximation to volume . We slightly improved Schwarzschild’s result by developing to arbitrary fixed order (cf. our (70) in ) and providing a mathematically elegant estimate on the Taylor rest (cf. (71) in )

On the basis of our discussion of the parameter in for the Sun, one has beyond Sun’s present age, and Formulas (70) and (71) remain accurate up to the start of Sun’s red giant phase. The calculation of the volume

turned out to be more involved, as depending upon the evaluation of an abelian integral that may not be expressed in terms of algebraic functions, and which we can only reduce to the canonical Legendre form (cf. (60) and (69) in ) confined to case for some constant (whose precise description is given in ). Going back to (38), one has hence . Of course, one should take into account the upper bound on a imposed by (51) implying

However, the right-hand side of (78) is in general (hence truncated Taylor approximation of as a function of is meaningless).

As a byproduct of (77), one obtains (cf. [1], or (9.178) in [10] (p. 294)) the truncated Taylor approximation of the mass defect

and uses (79) (together with the classical mechanics calculation of the surface potential on a sphere) to attribute to the loss of energy in packing the matter under its own gravitational energy. A similar formula for the mass defect is not known. That spherically symmetric solutions such as [where , cf. (51)] are appropriate for the calculation of mass defect of strange stars appears to be accounted for by [11].

Computing the bundle boundary (or Schmidt boundary, cf. [2]) of space-times , , and perhaps quantum-mechanically resolving the resulting singularities ([12,13,14]) is an open problem.

Author Contributions

The authors have equally contributed to the elaboration and writing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. An Abelian Integral

Our purpose in this section is bringing to the canonical form the abelian integral

where is the rational function . Starting from

one sets as customary

and distinguishes three cases as (I) , (II) , (III) , where . Integral (A1) is abelian in Cases (I)–(II) (while in Case (III) it reduces to a rational integral). To apply the classical scheme of reduction to the canonical (Legendre) form, one needs a decomposition of (A2) into second-degree factors . The required algebraic information is summarised in Table A1.

where and . For the remainder of Appendix, our calculations are confined to the case . One starts from the decomposition and applies the homography with and , so that to obtain

together with the requirements and or equivalently and i.e.,

yielding

Table A1.

Algebraic information on .

Table A1.

Algebraic information on .

| Cases | Real Root | Free Term | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | ||||

| , | ||||

| (II) |

So far,

(where are given by (A3)).Note that

The signs of the numbers , and are relevant (to the reduction to the canonical form). Note that and as . Hence, . Moreover,

The discussion of the signs of and requires a disjunction of cases, as (i) and , (ii) and , (iii) and , and (iv) and . For instance, in Case (i) (by (A3)), and , while , so that a further splitting of Case (i) in subcases is needed, as (i and or (i and . In the end,

- (i

- ,

- (i

- ,

- (ii)

- ,

- (iii

- ,

- (iii

- .

- (iv)

- .

Next, we need to split (A5) into even and odd terms, i.e.,

with

so that (A4) becomes

where the first integral should be further reduced to the canonical form, while the second is an ordinary Euler integral. Next, note that

Q.e.d.

We only illustrate the treatment of Case (i where , and . For the Euler integral, Euler’s substitution of the third kind is

Hence,

and [by (A8) with ]

so that

or

where

Going back to (A9), we set and (with and ). Let us substitute from

into (A9), so that to obtain

Note that (by (A6)) , and a calculation shows that

If we adopt the customary notations

then (by (A15))

where

(with , ) is certainly an elliptic integral of the first kind. As to , one starts from the (well-known) recurrence relation

and sets and , so that to obtain

and , where

is certainly an elliptic integral of the second kind. Elliptic integrals of the third kind

may be derived from with by setting ; hence,

Consequently, (by (A17)–(A19)), Equation (A16) becomes

Summing up (by (A1), (A4), (A9), (A13), (A14) and (A20)) under the transformations

(A1) becomes

where

Note that (by (A11)) ; hence, the “divergent” terms in (A21) sum up to (by )

References

- Schwarzschild, K. Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus Inkompressibler Flüssigkeit nach der Einsteinschen Theorie; Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss.: Berlin, Germany, 1916; pp. 424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C.J.S. The Analysis of Space-Time Singularities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Florides, P.S. A new interior Schwarzschild solution. Proc. Royal Soc. London Ser. A 1974, 337, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.L. An interior solution for a charge sphere in general relativity. Phys. Lett. A 1983, 88, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofinti, N.K. On a new interior Schwarzschild solution. Gen. Relativ. Grav. 1985, 17, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gron, O. A charged generalization of Florides’ interior Schwarzschild solution. Gen. Relativ. Grav. 1986, 18, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ségransan, D.; Kervella, P.; Forveille, T.; Queloz, D. First radius measurements of very low mass stars with the VLTI. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 397, L5–L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, W.B.; Ostlie, A.D. An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics; Cambridge University Press, University Printing House: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. 409. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas, I. Solar and Stellar Variability: Impact on Earth and Planets; Kosovichev, A.G., Andrei, A.H., Roelot, J.P., Eds.; International Astronomical Union Symposium, Volume 264; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, R.; Bazin, M.; Schiffer, M. Introduction to General Relativity; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanyan, Y.L.; Grigoryan, A.K.; Khachatryan, G.A. On the mass defect of strange stars. Astrophysics 1995, 38, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Bojowald, M. Quantum geometry and the Schwarzschild singularity. arXiv 2005, arXiv:gr-qc/0509075v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, V.; Winkler, O. On singularity resolution in quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 69, 084016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, V.; Winkler, O. Quantum resolution of black hole singularities. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, L127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).