There are More than Two Sides to Antisocial Behavior: The Inextricable Link between Hemispheric Specialization and Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cerebral Asymmetry

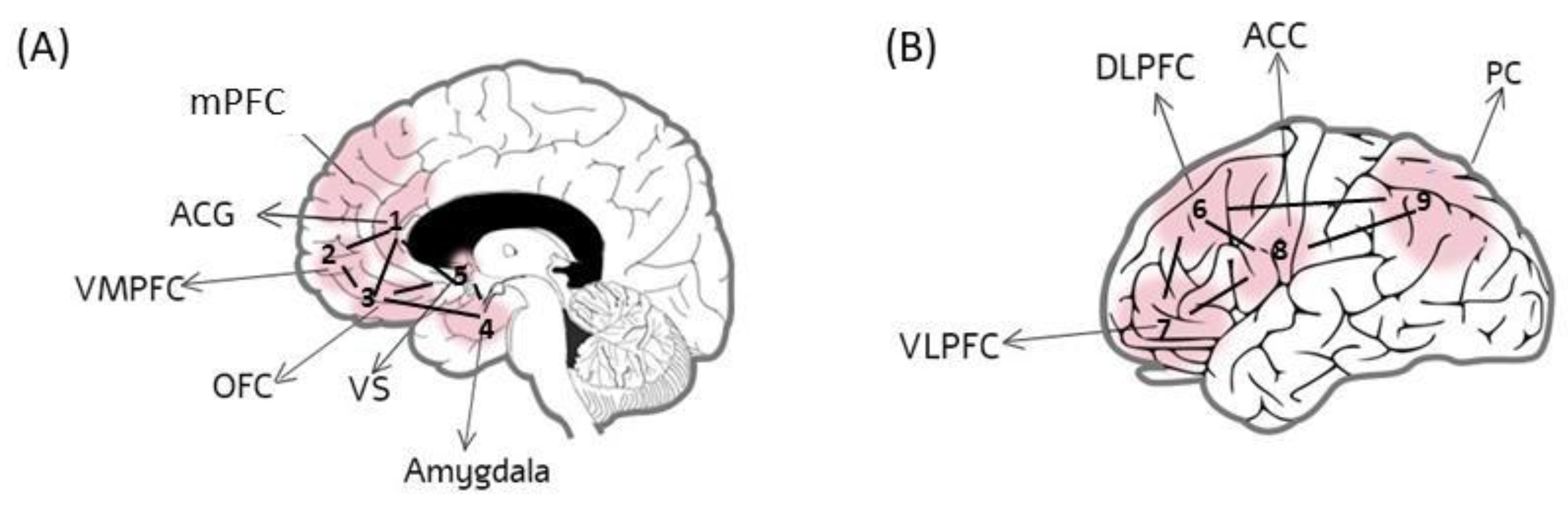

3. Neural and Cognitive Substrates of Antisocial Behavior

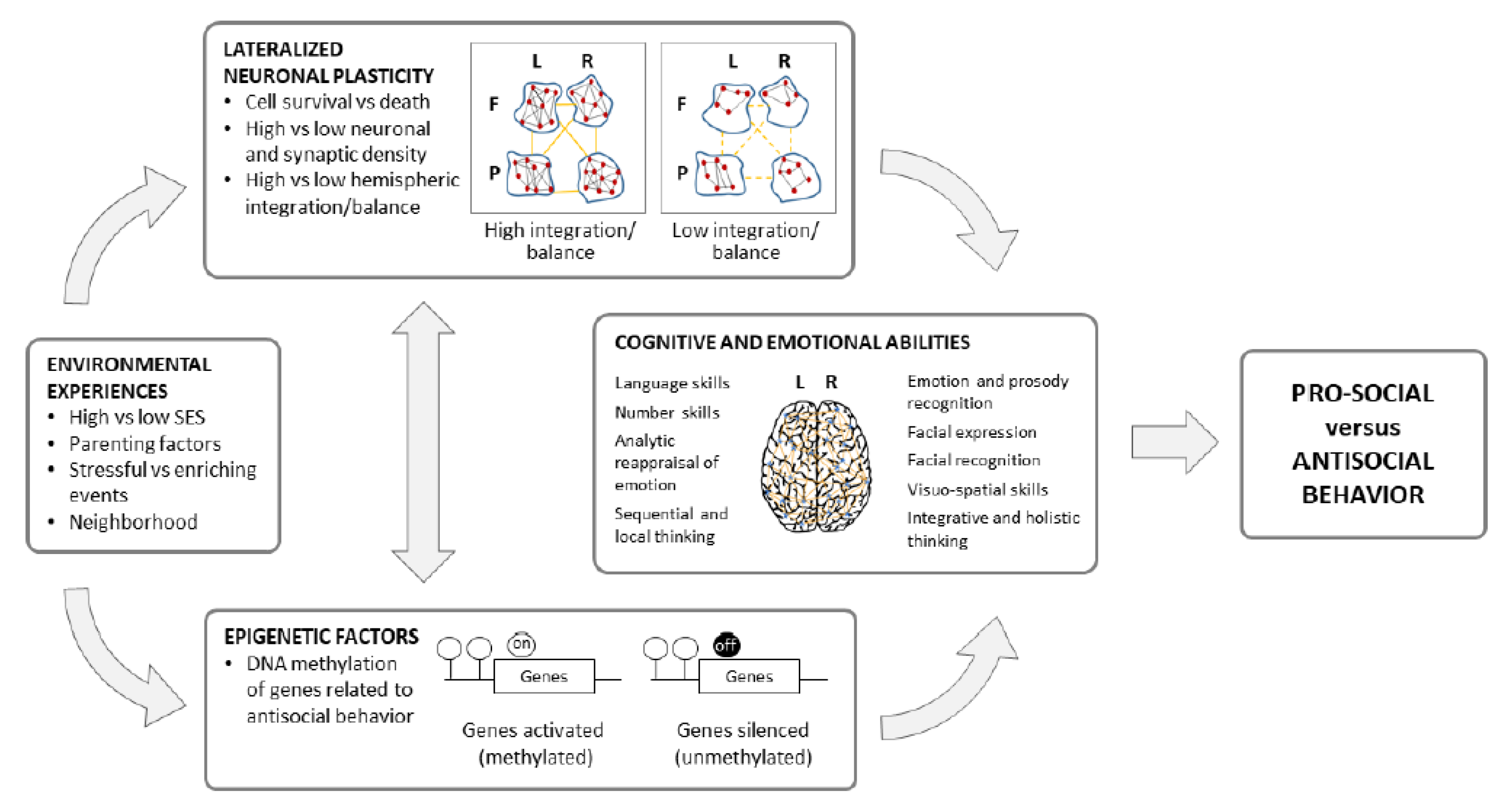

4. Lateralized Neural and Cognitive Substrates in Antisocial Behavior

5. Environmental Influences on Neural Substrates and Behavioral Expressions of Antisocial Tendencies

5.1. Environmental Effects on Early and Ongoing Development of Lateralized Neural Functions Associated with Antisocial Behavior

5.2. Environmental and Contextual Determinants of Antisocial Behavior

6. Implications and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | anterior cingulate cortex |

| ACG | anterior cingulate gyrus |

| APD | antisocial personality disorder |

| DLPFC | dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| DNAm | DNA methylation |

| l-DLPFC | left DLPFC |

| LH | left hemisphere |

| mPFC | medial prefrontal cortex |

| OFC | orbitofrontal cortex |

| PC | parietal cortex |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| r-OFC | right OFC |

| RH | right hemisphere |

| SES | socioeconomic status |

| tDCS | transcranial direct current stimulation |

| VLPFC | ventrolateral prefrontal cortex |

| VMPFC | ventromedial prefrontal cortex |

| vs. | ventral striatum |

References

- Hecht, D. Cerebral lateralization of pro-and anti-social tendencies. Exp. Neurobiol. 2014, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.; Lencz, T.; Taylor, K.; Hellige, J.B.; Bihrle, S.; Lacasse, L.; Lee, M.; Ishikawa, S.; Colletti, P. Corpus callosum abnormalities in psychopathic antisocial individuals. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, T.; Wilshire, C.; Jackson, L. The contribution of neuroscience to forensic explanation. Psychol. Crime Law 2018, 24, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, A.; Yang, Y. Neural foundations to moral reasoning and antisocial behavior. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2006, 1, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, D. An inter-hemispheric imbalance in the psychopath’s brain. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Omiya, Y. Brain asymmetry in cortical thickness is correlated with cognitive function. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolis, V.R.; Corbetta, M.; De Schotten, M.T. The architecture of functional lateralisation and its relationship to callosal connectivity in the human brain. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.Z.; Mathias, S.R.; Guadalupe, T.; Glahn, D.C.; Franke, B.; Crivello, F.; Tzourio-Mazoyer, N.; Fisher, S.E.; Thompson, P.M.; Francks, C.; et al. Mapping cortical brain asymmetry in 17,141 healthy individuals. Studies 2014, 40, E5154–E5163. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, A.; Ferreira, P.A.; Gonzales, J.E. Born this way? A review of neurobiological and environmental evidence for the etiology of psychopathy. Personal. Neurosci. 2019, 2, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.J.; Menon, K.R.; Hunjan, U.G. Neurobiological Aspects of Violent and Criminal Behaviour: Deficits in Frontal Lobe Function and Neurotransmitters. Int. J. Crim. Justice Sci. 2018, 13, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis, M.C.; Häberling, I.S. The many sides of hemispheric asymmetry: A selective review and outlook. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017, 23, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotts, S.J.; Jo, H.J.; Wallace, G.L.; Saad, Z.S.; Cox, R.W.; Martin, A. Two distinct forms of functional lateralization in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, C.L.; van Rootselaar, N.A.; Gibb, R.L. Sensorimotor Lateralization Scaffolds Cognitive Specialization. In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 238, pp. 405–433. [Google Scholar]

- Herbet, G.; Duffau, H. Revisiting the functional anatomy of the human brain: Toward a meta-networking theory of cerebral functions. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 1181–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallortigara, G.; Rogers, L. Survival with an asymmetrical brain: Advantages and disadvantages of cerebral lateralization. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 575–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzaniga, M.S. Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: Does the corpus callosum enable the human condition? Brain 2000, 123, 1293–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, L.; Serrien, D.J. Individual differences and hemispheric asymmetries for language and spatial attention. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badzakova-Trajkov, G.; Häberling, I.S.; Roberts, R.P.; Corballis, M.C. Cerebral asymmetries: Complementary and independent processes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, P.Y.; Zago, L.; Petit, L.; Mazoyer, B.; Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. Revisiting human hemispheric specialization with neuroimaging. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rotenberg, V.S.; Weinberg, I. Human memory, cerebral hemispheres, and the limbic system: A new approach. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1999, 125, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis, M.C. Humanity and the left hemisphere: The story of half a brain. Laterality 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, G.S.; Todd, B.K. A comparative perspective on lateral biases and social behavior. In Progress in Brain Research; Forrester, G.S., Hopkins, W.D., Hudry, K., Lindell, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 238, pp. 377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ocklenburg, S.; Gunturkun, O. Hemispheric asymmetries: The comparative view. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsner, K.N.; Silvers, J.A.; Buhle, J.T. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: A synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1251, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savopoulos, P.; Lindell, A.K. Born criminal? Differences in structural, functional and behavioural lateralization between criminals and noncriminals. Laterality Asymmetries Body Brain Cogn. 2018, 23, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotz, S.A.; Paulmann, S. Emotion, Language, and the Brain: Emotional Speech and Language Comprehension. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2011, 5, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Salehinejad, M.A.; Nitsche, M.A. Interaction of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l-DLPFC) and right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in hot and cold executive functions: Evidence from transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Neuroscience 2018, 369, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, J.T. Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. The executive functions and self-regulation: An evolutionary neuropsychological perspective. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2001, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, I.A.; van Dongen, J.D.; Maes, J.H.; Mars, R.B.; Baskin-Sommers, A.R. Classification and treatment of antisocial individuals: From behavior to biocognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 91, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhansel, L.; Weidler, C.; Votinov, M.; Clemens, B.; Raine, A.; Habel, U. Morphology of the criminal brain: Gray matter reductions are linked to antisocial behavior in offenders. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin, J.R. Neurocognitive elements of antisocial behavior: Relevance of an orbitofrontal cortex account. Brain Cogn. 2004, 55, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, K.; Grothe, M.; Prehn, K.; Vohs, K.; Berger, C.; Hauenstein, K.; Keiper, P.; Domes, J.; Teipel, S.; Herpertz, S.C. Brain volumes differ between diagnostic groups of violent criminal offenders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 263, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, E.S.; Steinberg, L. Adolescent development and the regulation of youth crime. Future Child. 2008, 18, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Gronde, T.; Kempes, M.; van El, C.; Rinne, T.; Pieters, T. Neurobiological correlates in forensic assessment: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, E.P.; Smith, A.R.; Silva, K.; Icenogle, G.; Duell, N.; Chein, J.; Steinberg, L. The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, J.; Güntürkün, O.; Ocklenburg, S. Building an asymmetrical brain: The molecular perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, R. Using dual process models to examine impulsivity throughout neural maturation. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2016, 41, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corballis, M.C. Evolution of cerebral asymmetry. In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 250, pp. 153–178. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, M.; Siegel, J.S.; Shulman, G.L. On the low dimensionality of behavioral deficits and alterations of brain network connectivity after focal injury. Cortex 2018, 107, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.M.; Gazzaniga, M.S. The functional brain architecture of human morality. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaniga, M.S. Principles of human brain organization derived from split-brain studies. Neuron 1995, 14, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, J. The effects of early focal brain injury on lateralization of cognitive function. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1998, 7, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konikkou, K.; Kostantinou, N.; Fanti, K.A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex affects emotional processing: Accounting for individual differences in antisocial behavior. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020, 16, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Raine, A. The neuroanatomical bases of psychopathy: A review of brain imaging findings. In Handbook of Psychopathy; Patrick, C.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 380–400. [Google Scholar]

- Pridmore, S.; Chambers, A.; McArthur, M. Neuroimaging in psychopathy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2005, 39, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, N.T.; Fukusima, S.S.; Aznar-Casanova, J.A. Models of brain asymmetry in emotional processing. Psychol. Neurosci. 2008, 1, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Coan, J.A.; Allen, J.J. Frontal EEG asymmetry and the behavioral activation and inhibition systems. Psychophysiology 2003, 40, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetterman, A.K.; Ode, S.; Robinson, M.D. For which side the bell tolls: The laterality of approach-avoidance associative networks. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.S.R.; Chao, H.H.A.; Lee, T.W. Neural correlates of speeded as compared with delayed responses in a stop signal task: An indirect analog of risk taking and association with an anxiety trait. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Park, S.; Lencz, T.; Bihrle, S.; LaCasse, L.; Widom, C.S.; Al-Dayeh, L.; Singh, M. Reduced right hemisphere activation in severely abused violent offenders during a working memory task: An fMRI study. Aggress. Behav. Off. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 2001, 27, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.D.; Bechara, A.; Tranel, D.; Anderson, S.W.; Richman, L.; Nopoulos, P. Right ventromedial prefrontal cortex: A neuroanatomical correlate of impulse control in boys. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.D.; Tranel, D.; Anderson, S.W.; Nopoulos, P. Right anterior cingulate: A neuroanatomical correlate of aggression and defiance in boys. Behav. Neurosci. 2008, 122, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.C.; Catani, M.; Deeley, Q.; Latham, R.; Daly, E.; Kanaan, R.; Murphy, D.G. Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiehl, K.A.; Smith, A.M.; Mendrek, A.; Forster, B.B.; Hare, R.D.; Liddle, P.F. Temporal lobe abnormalities in semantic processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2004, 130, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.L.; Gänßbauer, S.; Sommer, M.; Döhnel, K.; Weber, T.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Hajak, G. Gray matter changes in right superior temporal gyrus in criminal psychopaths. Evidence from voxel-based morphometry. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2008, 163, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.; Lencz, T.; Bihrle, S.; LaCasse, L.; Colletti, P. Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Raine, A.; Colletti, P.; Toga, A.W.; Narr, K.L. Abnormal temporal and prefrontal cortical gray matter thinning in psychopaths. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 561–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranel, D.; Bechara, A.; Denburg, N.L. Asymmetric functional roles of right and left ventromedial prefrontal cortices in social conduct, decision-making, and emotional processing. Cortex 2002, 38, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, D.G. The neurobiology of abandonment homicide. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2002, 7, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Shi, F.; Liu, H.; Li, G.; Ding, Z.; Shen, H.; Shen, C.; Lee, S.W.; Hu, D.; Wang, W.; et al. Reduced white matter integrity in antisocial personality disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Meloy, J.R.; Bihrle, S.; Stoddard, J.; Lacasse, L.; Buchsbaum, M.S. Reduced prefrontal and increased subcortical brain functioning assessed using positron emission tomography in predatory and affective murderers. Behav. Sci. Law 1998, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaree, H.A.; Everhart, D.E.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Harrison, D.W. Brain lateralization of emotional processing: Historical roots and a future incorporating “dominance”. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2005, 4, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobe, E.R. Independent and collaborative contributions of the cerebral hemispheres to emotional processing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Raine, A. Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2009, 174, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, A.; Baeken, C.; Vanderhasselt, M.A.; Philippot, P.; De Raedt, R. Impact of anodal and cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during attention bias modification: An eye-tracking study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Grabell, A.S.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Huppert, T.J.; Perlman, S.B. The neural substrates of cognitive flexibility are related to individual differences in preschool irritability: A fNIRS investigation. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 25, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luks, T.L.; Simpson, G.V.; Dale, C.L.; Hough, M.G. Preparatory allocation of attention and adjustments in conflict processing. Neuroimage 2007, 35, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, A.; Sommer, A.; Nieratschker, V.; Plewnia, C. Improvement of cognitive control and stabilization of affect by prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Glenn, A.L.; Raine, A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: Implications for the law. Behav. Sci. Law 2008, 26, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.; Yildirim, H.; Atmaca, M. Reduced hippocampus and amygdala volumes in antisocial personality disorder. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 75, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Ishikawa, S.S.; Arce, E.; Lencz, T.; Knuth, K.H.; Bihrle, S.; LaCasse, L.; Colletti, P. Hippocampal structural asymmetry in unsuccessful psychopaths. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 55, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Raine, A.; Narr, K.L.; Colletti, P.; Toga, A.W. Localization of deformations within the amygdala in individuals with psychopathy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallesi, A. Organisation of executive functions: Hemispheric asymmetries. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2012, 24, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprian, G.; Langs, G.; Brugger, P.C.; Bittner, M.; Weber, M.; Arantes, M.; Prayer, D. The prenatal origin of hemispheric asymmetry: An in utero neuroimaging study. Cereb. Cortex 2011, 21, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasung, L.; Turk, E.A.; Ferradal, S.L.; Sutin, J.; Stout, J.N.; Ahtam, B.; Lin, P.; Grant, P.E. Exploring early human brain development with structural and physiological neuroimaging. Neuroimage 2019, 187, 226–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, A.L.; Raine, A. Neurocriminology: Implications for the punishment, prediction and prevention of criminal behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, R.E. Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: The ‘original sin’ hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E. Developmental origins of chronic physical aggression: An international perspective on using singletons, twins and epigenetics. Eur. J. Criminol. 2015, 12, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Vitaro, F.; Côté, S. Developmental origins of chronic physical aggression: A bio-psycho-social model for the next generation of preventive interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuvblad, C.; Beaver, K.M. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tierney, A.L.; Nelson, C.A., III. Brain development and the role of experience in the early years. Zero Three 2009, 30, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Brzosko, Z.; Mierau, S.B.; Paulsen, O. Neuromodulation of Spike-Timing-Dependent plasticity: Past, present, and future. Neuron 2019, 103, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J.; McEwen, B.S. Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenhouse, H.C.; Andersen, S.L. Developmental trajectories during adolescence in males and females: A cross-species understanding of underlying brain changes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, J.; Jernigan, T.L. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010, 20, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Fano, A.; Leshem, R.; Ben-Soussan, T.D. Creating an internal environment of cognitive and psycho-emotional well-being through an external movement-based environment: An overview of Quadrato Motor Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, R. Brain development, impulsivity, risky decision making, and cognitive control: Integrating cognitive and socioemotional processes during adolescence—An introduction to the special Issue. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2016, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Attachment, affect regulation, and the developing right brain: Linking developmental neuroscience to pediatrics. Pediatrics Rev. 2005, 26, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, J.; Nelson, C.A. Early adverse experiences and the developing brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiron, C.; Jambaque, I.; Nabbout, R.; Lounes, R.; Syrota, A.; Dulac, O. The right brain hemisphere is dominant in human infants. Brain J. Neurol. 1997, 120, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsbourne, M. Development of Cerebral Lateralization in Children. In Handbook of Clinical Child Neuropsychology; Reynolds, C.R., Fletcher-Janzen, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Glenn, A.L.; Schug, R.A.; Yang, Y.; Raine, A. The Neurobiology of psychopathy: A neurodevelopmental perspective. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J.R.; Peschardt, K.S.; Budhani, S.; Mitchell DG, V.; Pine, D.S. The development of psychopathy. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshem, R.; Weisburd, D. Epigenetics and hot spots of crime: Rethinking the relationship between genetics and criminal behavior. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2019, 35, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, T.A.; Gregory, A.M.; Eley, T.C. Genes of experience: Explaining the heritability of putative environmental variables through their association with behavioural and emotional traits. Behav. Genet. 2013, 43, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, K.; Poeggel, G.; Holetschka, R.; Helmeke, C.; Braun, K. Paternal deprivation affects the development of corticotrophin-releasing factor-expressing neurones in prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus of the biparental Octodon degus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 23, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, L.A.; Bezdjian, S.; Raine, A. Behavioral genetics: The science of antisocial behavior. Law Contemp. Probl. 2006, 69, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, R.J.R. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisi, C.O.; Moffitt, T.E.; Knodt, A.R.; Harrington, H.; Ireland, D.; Melzer, T.R.; Poulton, R.; Ramrakha, S.; Caspi, A.; Viding, E. Associations between life-course-persistent antisocial behaviour and brain structure in a population-representative longitudinal birth cohort. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, D.A.; Farah, M.J.; Meaney, M.J. Socioeconomic status and the brain: Mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizada, R.D.; Richards, T.L.; Meltzoff, A.; Kuhl, P.K. Socioeconomic status predicts hemispheric specialisation of the left inferior frontal gyrus in young children. Neuroimage 2008, 40, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, D.B. Socioeconomic status, a forgotten variable in lateralization development. Brain Cogn. 2011, 76, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufford, A.J.; Bianco, H.; Kim, P. Socioeconomic disadvantage, brain morphometry, and attentional bias to threat in middle childhood. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 19, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, K.G.; Houston, S.M.; Brito, N.H.; Bartsch, H.; Kan, E.; Kuperman, J.M.; Akshoomoff, N.; Amaral, D.G.; Bloss, C.S.; Libiger, O.; et al. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittle, S.; Dennison, M.; Vijayakumar, N.; Simmons, J.G.; Yücel, M.; Lubman, D.I.; Pantelis, C.; Allen, N.B. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology affect brain development during adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Attachment and the regulation of the right brain. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2000, 2, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teicher, M.H.; Andersen, S.L.; Polcari, A.; Anderson, C.M.; Navalta, C.P.; Kim, D.M. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003, 27, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Henry, L.; Grieve, S.M.; Guilmette, T.J.; Niaura, R.; Bryant, R.; Bruce, S.; Williams, L.M.; Richard, C.C.; Cohen, R.A.; et al. The relationship between early life stress and microstructural integrity of the corpus callosum in a non-clinical population. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Bellis, M.D.; Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2014, 23, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M.H.; Tomoda, A.; Andersen, S.L. Neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment: Are results from human and animal studies comparable? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, C.; Provençal, N.; Suderman, M.; Côté, S.M.; Vitaro, F.; Hallett, M.; Tremblay, R.E.; Szyf, M. DNA methylation signature of childhood chronic physical aggression in T cells of both men and women. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyf, M. DNA methylation, the early-life social environment and behavioral disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2011, 3, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; McClay, J.; Moffitt, T.E.; Mill, J.; Martin, J.; Craig, I.W.; Poulton, R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science 2002, 297, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.B.; Beaver, K.M. The influence of nutritional factors on verbal deficits and psychopathic personality traits: Evidence of the moderating role of the MAOA genotype. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15739–15755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraaijenvanger, E.J.; He, Y.; Spencer, H.; Smith, A.K.; Bos, P.A.; Boks, M.P. Epigenetic variability in the human oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene: A possible pathway from early life experiences to psychopathologies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 96, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, S.; Mariotti, V.; Iofrida, C.; Pellegrini, S. Genes and aggressive behavior: Epigenetic mechanisms underlying individual susceptibility to aversive environments. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltes, R.; Chiocchetti, A.G.; Freitag, C.M. The neurobiological basis of human aggression: A review on genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Am. J. Med Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2016, 171, 650–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svrakic, D.M.; Cloninger, R.C. Epigenetic perspective on behaviour development, personality, and personality disorders. Psychiatr. Danub. 2010, 22, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, C.A.; Walton, E.; Jaffee, S.R.; O’Connor, T.; Maughan, B.; Relton, C.L.; Smith, R.G.; McArdle, W.; Gaunt, T.R.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; et al. Neonatal DNA methylation and early-onset conduct problems: A genome-wide, prospective study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, A.; Sugden, K.; Arseneault, L.; Corcoran, D.L.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Moffitt, T.E.; Newbury, J.B.; Odgers, C.; Rasmussen, L.J. Association of Neighborhood Disadvantage in Childhood With DNA Methylation in Young Adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, E.; Knox, O.; Sugden, K.; Burrage, J.; Wong, C.C.; Belsky, D.W.; Corcoran, D.L.; Arseneault, L.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; et al. Characterizing genetic and environmental influences on variable DNA methylation using monozygotic and dizygotic twins. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Beckley, A. Abandon Twin Research-Embrace Epigenetic Research: Premature Advice for Criminologists. Criminology 2015, 53, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin-Sommers, A.R. Dissecting antisocial behavior: The impact of neural, genetic, and environmental factors. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S.A.; McGue, M.; Iacono, W.G. Environmental contributions to the stability of antisocial behavior over time: Are they shared or non-shared? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.W.; Cabeza, R. Cross-hemispheric collaboration and segregation associated with task difficulty as revealed by structural and functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8191–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, K.E.; Fink, G.R.; Marshall, J.C. Mechanisms of hemispheric specialization: Insights from analyses of connectivity. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolcos, F.; Katsumi, Y.; Moore, M.; Berggren, N.; de Gelder, B.; Derakshan, N.; Hamm, A.O.; Koster, E.H.; Ladouceur, C.D.; Okon-Singer, H.; et al. Neural correlates of emotion-attention interactions: From perception, learning, and memory to social cognition, individual differences, and training interventions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 559–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zilverstand, A.; Song, H.; Uquillas, F.D.O.; Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Cheng, L.; Zou, Z. The influence of emotional interference on cognitive control: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies using the emotional Stroop task. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, D.H.; Banich, M.T. The cerebral hemispheres cooperate to perform complex but not simple tasks. Neuropsychology 2000, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, D.E.; Wager, T.D.; Jonides, J. Interference resolution: Insights from a meta-analysis of neuroimaging tasks. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2007, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeis, N.; Bernhardt, B.C.; Singer, T. Impulse control and underlying functions of the left DLPFC mediate age-related and age-independent individual differences in strategic social behavior. Neuron 2012, 73, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. The orbitofrontal cortex and emotion in health and disease, including depression. Neuropsychologia 2019, 128, 14–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xu, T.; Zhang, R.; Suo, T.; Feng, T. High Self-Control Reduces Risk Preference: The Role of Connectivity between Right Orbitofrontal Cortex and Right Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosson, D.S. Divided visual attention in psychopathic and nonpsychopathic offenders. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y.; Kosson, D.S. State-dependent executive deficits among psychopathic offenders. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. JINS 2005, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosson, D.S.; Miller, S.K.; Byrnes, K.A.; Leveroni, C.L. Testing neuropsychological hypotheses for cognitive deficits in psychopathic criminals: A study of global-local processing. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2007, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Newman, J.P.; Wallace, J.F.; Luh, K.E. Left-hemisphere activation and deficient response modulation in psychopaths. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 11, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonite, M.; Harenski, C.L.; Koenigs, M.R.; Kiehl, K.A.; Kosson, D.S. Testing the left hemisphere activation hypothesis in psychopathic offenders using the Stroop task. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A. Biosocial studies of antisocial and violent behavior in children and adults: A review. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2002, 30, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, A.L.; McCauley, K.E. How biosocial research can improve interventions for antisocial behavior. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2019, 35, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Goozen, S.H.; Fairchild, G. How can the study of biological processes help design new interventions for children with severe antisocial behavior? Dev. Psychopathol. 2008, 20, 941–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.A.; Dix, T. Parenting and naturally occurring declines in the antisocial behavior of children and adolescents: A process model. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2014, 6, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseldijk, L.W.; Bartels, M.; Vink, J.M.; van Beijsterveldt, C.E.; Ligthart, L.; Boomsma, D.I.; Middeldorp, C.M. Genetic and environmental influences on conduct and antisocial personality problems in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerone, K.D.; Dahlberg, C.; Malec, J.F.; Langenbahn, D.M.; Felicetti, T.; Kneipp, S.; Ellmo, W.; Kalmar, K.; Giacino, J.T.; Harley, J.P.; et al. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, J.; Brown, T.T.; Haist, F.; Jernigan, T.L. Brain and Cognitive Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 7th ed.; Richard, M.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, M.; Prime, H.; Jenkins, J.M.; Yeates, K.O.; Williams, T.; Lee, K. On the relation between theory of mind and executive functioning: A developmental cognitive neuroscience perspective. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 2119–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, P.O.H.; Treiber, K. Social disadvantage and crime: A criminological puzzle. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 1232–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfundmair, M.; Graupmann, V.; Frey, D.; Aydin, N. The different behavioral intentions of collectivists and individualists in response to social exclusion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Way, B.M.; Lieberman, M.D. Is there a genetic contribution to cultural differences? Collectivism, individualism and genetic markers of social sensitivity. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2010, 5, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, J.H. Neuroanatomical backgrown to understanding the brain of the young psychopath. Ohio State J. Crim. Law 2006, 3, 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Wertz, J.; Caspi, A.; Belsky, D.W.; Beckley, A.L.; Arseneault, L.; Barnes, J.C.; Corcoran, D.L.; Hogan, S.; Houts, R.M.; Morgan, N.; et al. Genetics and crime: Integrating new genomic discoveries into psychological research about antisocial behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leshem, R. There are More than Two Sides to Antisocial Behavior: The Inextricable Link between Hemispheric Specialization and Environment. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12101671

Leshem R. There are More than Two Sides to Antisocial Behavior: The Inextricable Link between Hemispheric Specialization and Environment. Symmetry. 2020; 12(10):1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12101671

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeshem, Rotem. 2020. "There are More than Two Sides to Antisocial Behavior: The Inextricable Link between Hemispheric Specialization and Environment" Symmetry 12, no. 10: 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12101671

APA StyleLeshem, R. (2020). There are More than Two Sides to Antisocial Behavior: The Inextricable Link between Hemispheric Specialization and Environment. Symmetry, 12(10), 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12101671