Abstract

In the rapidly urbanizing Global South, megacities face a perplexing “paradox of idleness”: acute land scarcity in the urban core coexisting with inefficient rural homesteads in the hinterland. Using Shanghai as a representative case, this study integrates spatial autocorrelation analysis with Geographical Detector modeling to quantify the spatial differentiation patterns and driving mechanisms of this phenomenon. The results reveal a distinct core-periphery gradient, with vacancy density increasing from the inner suburbs to the remote hinterland. Four regional typologies were identified: dispersed-inefficient, high-density accumulation, sparse-stable, and intensive-efficient. Quantitative analysis identifies demographic aging and low agricultural efficiency as dominant drivers. Counter-intuitively, the study finds that top-down institutional pilots alone exert a negligible direct impact. Instead, interaction analysis confirms a significant policy-bundling effect, in which institutional tools promote revitalization only when coupled with economic and locational incentives. These findings expose a mechanism of “involuntary vacancy” trapped by institutional rigidity, distinct from the market-driven abandonment seen in shrinking or remote Western contexts. Consequently, a gradient-based governance framework is proposed to transition from “one-size-fits-all” regulation to targeted spatial restructuring pathways.

1. Introduction

1.1. The “Paradox of Idleness” Phenomenon

Rapid urbanization in the Global South is typically characterized by escalating demand for land and fierce competition for spatial resources [1,2,3]. However, in the peri-urban fringes of megacities like Shanghai, a contradictory phenomenon has emerged: the widespread idleness of rural homesteads despite high regional land values. While millions of migrants struggle for housing in the city center, vast amounts of rural construction land—technically “occupied” but functionally “hollow”—remain underutilized in the hinterland [4]. This “paradox of idleness” highlights a critical structural mismatch in the flow of urban-rural production factors, posing a severe challenge to sustainable spatial restructuring.

This structural tension finds its most acute manifestation in China. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, idle homesteads nationwide cover over 2 million hectares, with an average vacancy rate of 17.6% [5]. This phenomenon, often described as “occupied but underutilized”, exhibits a strong distance-decay pattern: vacancy rates are typically lower in suburban areas but escalate sharply in outer rural regions [6]. Such disparities not only reflect the imbalance in urban-rural resource allocation but also mirror the broader challenges faced by many developing countries transitioning from extensive expansion to high-quality development.

1.2. Existing Research on Drivers and Governance

Academic studies have extensively analyzed the phenomenon, generally agreeing that it arises from a complex interaction of socioeconomic factors [7]. Economically, the persistent outflow of rural populations creates a fundamental supply-and-demand mismatch [8,9], while socially, shifting lifestyles and intergenerational differences render traditional housing outdated [10,11,12]. Regarding governance, research highlights three primary revitalization models, government-led, collective-led, and multi-stakeholder collaboration [13,14,15], with practical explorations such as Shanghai’s functional transfers and Guangzhou’s land development rights [16].

However, the mechanisms driving vacancy vary significantly across global contexts, presenting patterns that diverge from the Chinese experience. In developed regions, vacancy is typically a symptom of market-driven abandonment or demographic decline: Japan’s “Akiya” crisis is driven by hyper-aging and demographic asset freezing [17,18], while vacancy in Europe and the United States stems largely from long-term depopulation or economic restructuring [19,20,21,22,23]. Conversely, in the Global South, underuse is often shaped by informal speculation and insecure tenure [24,25]. Crucially, in these cases, vacancy reflects either a lack of market value or property insecurity. These existing narratives fail to fully explain the “paradox of idleness” in China’s megacities, where high housing demand coexists with widespread rural vacancy, indicating a need for localized theoretical innovation.

1.3. Uniqueness of the Context in China and Shanghai

This discrepancy highlights the unique institutional context of China. Unlike the “market-driven abandonment” linked to depopulation in Western shrinking cities [26,27], where properties remain tradeable commodities, or the vacancy caused by land tenure insecurity in the Global South [24,25], idleness in China represents a distinct form of “involuntary vacancy” shaped by the dual urban-rural land system.

Under this system, rural homesteads are defined not as private real estate, but as collectively owned, welfare-oriented assets restricted to members of the rural collective. Strict institutional rigidities, specifically the prohibition on selling to external urban residents or capital, combined with the “one household, one homestead” policy and underdeveloped exit mechanisms [28,29], create a structural lock-in. This results in a “land urbanization lag”: while migrants have physically moved to cities for employment, their rural assets remain “frozen” [30,31]. They are trapped in a dilemma where they can neither effectively utilize their homes nor liquidate them, leading to widespread structural idleness.

Shanghai presents a distinct paradigmatic case of this uniqueness. Unlike remote agricultural regions, Shanghai is a high-density megacity where the “hinterland” (areas beyond the Suburban Ring Road) implies not remote wilderness but strictly regulated ecological conservation zones [32]. In these areas, development intensity is rigidly capped by the municipal master plan to safeguard the ecological baseline. This distinction is critical: vacancy here is driven by a unique “structural mismatch”, where assets are trapped by strict planning restrictions rather than a lack of intrinsic economic value, distinguishing it from both ordinary suburban sprawl and traditional rural decline.

1.4. Measurement and Typology

Given this complexity, accurately measuring the phenomenon is challenging. Early studies primarily relied on qualitative methods, including field surveys and statistical data [33,34], which were limited in spatial scope. Recent advancements have facilitated the application of multi-source data, such as power consumption [35] and nighttime lights [36], though these often face constraints regarding cost and timeliness.

To achieve a more detailed understanding, scholars have developed various metrics, ranging from the ratio of unused homestead area to supply-demand indices [30,37]. Furthermore, researchers have created typologies based on multiple criteria: by formation cause, such as new construction without demolishing old structures, inheritance, and migration-induced vacancy [7,38]; by functional status, they distinguish between seasonal and complete vacancy [6]. Nevertheless, relying on single indicators or isolated typologies fails to capture the spatial heterogeneity of megacities. Consequently, a multi-dimensional approach combining “vacancy rate” (intensity) and “distribution density” (clustering) is necessary to accurately reveal the complex spatial reality.

1.5. Research Gaps and Objectives

While existing studies provide a solid foundation, notable gaps remain. Most research focuses on small-to-medium cities or individual villages [5,39,40], limiting their applicability to high-mobility, land-scarce, and highly marketized megacities like Shanghai. From a methodological perspective, the complex interactions between institutional constraints and market forces are rarely quantified [41].

To bridge these gaps, this study uses Shanghai as a representative case and integrates spatial autocorrelation analysis with Geographical Detector modeling to develop a “measurement–identification–driver analysis” framework. We aim to address three main questions: (1) What are the spatial distribution characteristics and regional patterns of idle homesteads in rural Shanghai? (2) How do demographic, economic, land-use, and locational factors individually and collectively influence homestead idleness? (3) How can a gradient-based governance framework be constructed to address the unique “involuntary vacancy” in megacities? By clarifying how Shanghai’s mechanisms diverge from global patterns, this study provides empirical evidence for improving rural land governance in rapidly urbanizing regions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the study area, data sources, and research framework. Section 3 discusses spatial distribution, clustering patterns, and regional differences in idle homesteads. Section 4 examines interaction effects and overall mechanisms, followed by planning suggestions and governance strategies. Section 5 summarizes the key findings, addresses limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection and Overview of Study Area

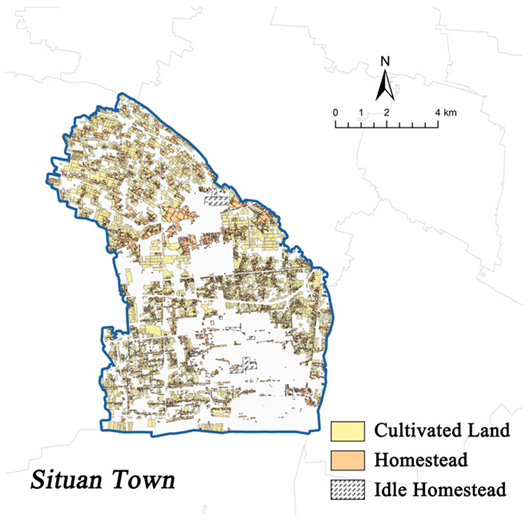

According to statistics from the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Civil Affairs, the City has 108 subdistricts, 108 townships, 5025 neighborhood committees, and 1553 village committees. This study uses Shanghai’s 108 townships as the basic spatial units, covering roughly 5995 km2. The rest of the municipality falls within subdistrict jurisdiction, where rural homesteads are absent (Figure 1). Data from China’s Seventh National Population Census indicates that Shanghai’s permanent resident population reached 24.8836 million in 2020, with an urbanization rate of 89.3%. The study area has approximately 2.892 million permanent residents, including around 1.236 million registered residents. Since it spans suburban and peri-urban zones within a megacity, the study area represents a typical spatial sample for exploring rural spatial restructuring amid high-density urbanization.

Figure 1.

Study area.

Spatially, Shanghai exhibits a polycentric structure supported by the “Five New Towns” strategy (Jiading, Qingpu, Songjiang, Fengxian, and Nanhui). These planned new towns act as major magnetic nodes designed to absorb population and industries from the central city. Consequently, they create a strong “siphon effect” on the surrounding rural areas, accelerating the outflow of the local agricultural population and placing different transformation pressures on rural homesteads compared to traditional agricultural villages in the hinterland.

Furthermore, the “hinterland” in this study (areas beyond the Suburban Ring Road) does not imply remote wilderness as often perceived in Western geography [32]. Instead, it represents a strictly regulated ecological and agricultural conservation zone, where development intensity is rigidly capped by the municipal master plan. This unique spatial planning framework forms the baseline for analyzing regional differences in homestead idleness.

2.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The data used in this study mainly come from the Shanghai Statistical Yearbook and district-level statistical yearbooks, homestead data from Shanghai’s 2020 Third National Land Survey base map, and Seventh National Population Census data. In the Third National Land Survey base map data, code 253 indicates homesteads in use, while code 254 identifies homesteads classified as long-term idle. Together, these categories make up the homestead land dataset. Specifically, code 254 is defined as rural homestead where the surface structures have collapsed, or the housing has been unoccupied for more than 2 years due to migration, yet the land use rights remain registered. This definition distinguishes “structural idleness” caused by rural decline from “seasonal vacancy” (e.g., second homes), thereby ensuring accurate identification of inefficient land use in the context of urbanization.

From the statistical yearbooks, indicators such as the permanent resident population, registered population, non-agricultural population, total number of households, and gross agricultural output were obtained at the township level. Based on the homestead database extracted from the Third National Land Survey base map, we further derived township-level metrics, including total homestead area and idle homestead area. Using GIS spatial neighborhood analysis, centroid points were generated for Shanghai’s 108 townships. Taking Shanghai People’s Square as the reference point for the municipal center, straight-line distances from each township to the city center and to the nearest motorway were calculated.

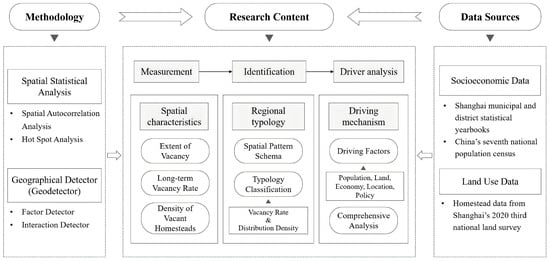

2.3. Study Design

This study combines spatial statistical analysis with Geographical Detector (Geodetector) modeling to develop a “measurement–identification–driver analysis” framework to explore the spatial differences and underlying causes of rural homestead idleness in Shanghai (Figure 2). To achieve accurate spatial characterization and facilitate subsequent typology classification, three indicators were used: the extent of vacancy, the long-term vacancy rate, and the density of vacant homesteads. These indicators measure the overall extent of idleness, the efficiency of homestead utilization, and the level of spatial clustering, respectively. By focusing on the long-term vacancy rate and the density of vacant homesteads as key variables, a quantile classification method was applied to quantitatively assess vacancy intensity and clustering patterns, providing a solid foundation for identifying spatial features and developing regional typologies.

Figure 2.

Research framework.

2.3.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Spatial pattern identification was carried out through spatial autocorrelation analysis to uncover the spatial dependence and heterogeneity of homestead idleness, using both global and local measures. Global spatial autocorrelation analysis assesses whether idle land exhibits spatial clustering, but it cannot pinpoint the exact locations of the clusters. Moran’s I index is commonly used for this purpose, calculated as follows:

where n represents the total number of spatial units, denotes the idle homestead rate of township i, is the spatial weight matrix, and is the sum of all spatial weights.

To further detect the spatial heterogeneity and local clustering structure, local indicators of spatial association (LISA) were applied. By evaluating the statistical association between each unit and its neighbors, four types of local clusters were identified: high-high (H-H), low-low (L-L), high-low (H-L), and low-high (L-H), along with outlier regions. In addition, Getis-Ord Gi* statistics were employed to identify significant hot and cold spots of homestead idleness, providing complementary evidence for spatial concentration patterns.

2.3.2. Geographical Detector (Geodetector)

To analyze the driving mechanism, the Geodetector was employed to identify and quantify the determinants shaping spatial differentiation in homestead idleness. Unlike conventional regression models (e.g., OLS or GWR), which assume linear associations, the Geodetector method effectively quantifies the explanatory power of factors by analyzing the spatial consistency between the dependent variable and potential drivers. This makes it particularly suitable for identifying the complex, nonlinear interaction effects inherent in urban-rural spatial systems. This method is especially beneficial for managing categorical variables, identifying nonlinear relationships, and evaluating interaction effects among multiple factors, making it highly relevant for complex urban-rural systems. Factor detection was applied to measure the individual explanatory power of factors for spatial variation in vacancy rates using the q-value, calculated as follows:

where denotes the number of factor strata, and represent the sample size and variance of stratum , and and denote the sample size and variance of the entire study area.

Furthermore, interaction detection identified the nature of factor interactions by pairing influencing factors, estimating their joint q-value, and comparing it to the q-values of the corresponding single-factor models. This enables a thorough understanding of how demographic, economic, locational, land, and policy factors together influence homestead idleness. The continuous independent variables were discretized into five strata using the quantile method. This method was selected to ensure a balanced sample size within each stratum and to maximize the statistical power of the Geodetector q-statistic.

2.3.3. Selection of Influencing Factors

Drawing on established theoretical frameworks and prior research [10,37,42,43,44,45], this study selected thirteen indicators across five dimensions: demographic, economic, locational, land-use, and policy. Standard variables include population outflow (X1), aging (X2), and density (X3); homestead size (X4) and development intensity (X6); distance to city center (X7); agricultural output (X9), livelihood dependency (X10), and cultivated land density (X11); as well as the homestead withdrawal pilot (X13). Crucially, three indicators were chosen to capture specific structural dynamics: distance to motorway (X8) proxies transport accessibility based on spatial interaction theory [44]; arable-to-settlement land ratio (X5) reflects the balance between production and living spaces [42]; and construction land consolidation intensity (X12) characterizes Shanghai’s unique “negative growth” policy for ecological restoration [45]. The complete dataset (Table 1) was discretized using SPSS version 20.0 quantile classification for Geodetector analysis.

Table 1.

Index system of influencing factors.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Homesteads

Based on Shanghai’s ring-road system and spatial functional structure, the metropolitan area has traditionally been divided into three zones: the central urban area, the near suburbs, and the outer suburbs. However, as the city’s spatial structure has become more polycentric and functionally diverse, this simple tripartite classification no longer effectively captures the nuances of urban-rural transitions. In recent years, scholars have revealed the concentric progression of urban spatial activities through perspectives such as mobile phone signaling data [46], commuting patterns [47], and other forms of spatiotemporal behavioral patterns analysis. To better reflect these transition characteristics, this study further refines the definition of outer suburbs beyond the traditional classification by designating the area outside the Suburban Ring Road as the hinterland.

Shanghai’s ring roads were constructed incrementally to accompany the city’s expansion, marking the transition from the urban core to the suburbs and rural hinterland. Although these roads allow for seamless physical transportation connecting the urban core to the hinterland, they function as critical “institutional thresholds.” The regions between them form distinct government control zones subject to differentiated land-use regulations and resource allocation policies. This creates a unique spatial structure where physical permeability coexists with strict policy boundaries. Therefore, the ring road system serves as a logical basis for the spatial classification in this study.

In the context of Shanghai, the “hinterland” does not imply remote wilderness or abandoned territory, as it is often perceived in Western geography. Instead, it represents a strictly regulated ecological and agricultural conservation zone beyond the suburban ring road. In these areas, development intensity is rigidly capped by the municipal master plan to safeguard the city’s ecological baseline. This distinction is critical for understanding the mechanisms underlying homestead idleness: strict land-use restrictions, rather than mere remoteness, shape the unique settlement patterns here.

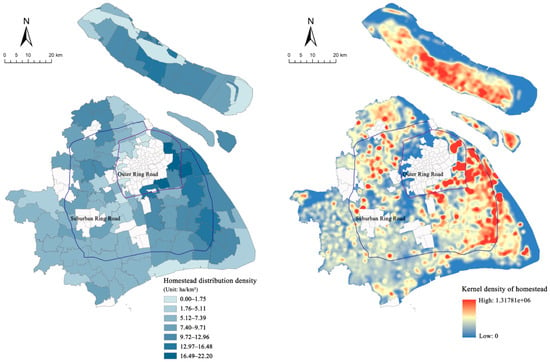

Hence, the study area is divided into three gradient levels: inner suburbs (between the Inner Ring Road and the Outer Ring Road), outer suburbs (between the Outer Ring Road and the Suburban Ring Road), and hinterland (beyond the Suburban Ring Road). The spatial distribution of homestead varies notably across these zones, exhibiting a general pattern of increasing density from the center outward and gradually more complex diffusion structures. In Figure 3, the inner purple and outer blue lines represent the Outer Ring Road and the Suburban Ring Road, respectively. They serve as key boundaries dividing the region into the inner suburbs, outer suburbs, and hinterland.

Figure 3.

Homestead density analysis.

3.1.1. General Characteristics of Homesteads

The average distribution density of rural homesteads in Shanghai is 8.04 ha/km2, showing a distinct spatial gradient that increases from the inner suburbs toward the outer periphery (Figure 3). Kernel density analysis further supports this trend by revealing distinct zonation patterns. At the regional level, Pudong, Jiading, and Chongming display densities of 11.58 ha/km2, 9.79 ha/km2, and 9.30 ha/km2, respectively, forming a high-density peripheral belt. Suburban areas like Baoshan and Minhang have lower densities with a scattered distribution. At the township level, homestead distribution density rises from southwest to northeast. Suburban areas show relatively low density, while the outer suburbs and inland villages form more distinct high-density clusters, reflecting the outward spread of homesteads. Typical areas such as Huinan and Chuansha in the outer suburbs, along with Huating, Miaozhen, and Baozhen in the hinterland, show clustered homestead use and limited spatial capacity. This pattern suggests that outer suburban and hinterland villages experience higher demand for homestead, which influences the future spatial pattern of homestead vacancies.

Per capita homestead levels reveal spatial disparities in land use (Figure 4). Based on the registered agricultural population, the citywide average is 401 square meters, with Minhang, Pudong, Jiading, and Songjiang exceeding the municipal average, while Baoshan ranks the lowest. In contrast, the figure based on permanent resident statistics is only 189 square meters, indicating a significant gap between supply and demand. This gap is larger in Chongming, Pudong, and Minhang, while Qingpu and Fengxian exhibit relatively minor gaps. In some rural hinterland areas such as Chuansha, Laogang, and Baozhen, the resident population is small, but the per capita homestead area is relatively large. This indicates that the pace of population urbanization has outpaced that of land factor marketization. While the population has moved to towns, their homestead resources have not been updated in time. The presence of many people with limited land and a few with abundant land not only worsens spatial imbalances but also creates clear regional differences in homestead idle time.

Figure 4.

Per capita homestead area based on different statistical definitions.

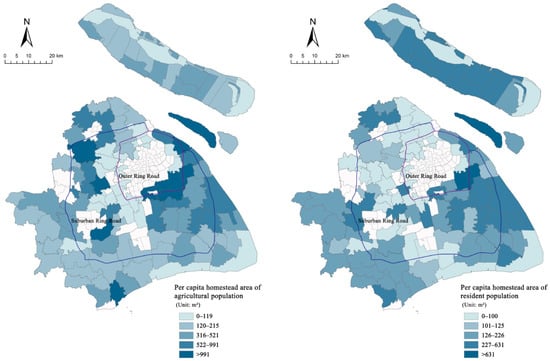

3.1.2. Characteristics of Idle Homesteads

Approximately 84 km2 of rural homestead land in Shanghai remains idle year-round, accounting for 16.3% of the total. These idle homesteads show an uneven distribution, with scattered patches in the inner suburbs, increasing density toward the outer suburbs, and noticeable clustering in remote hinterland areas (Figure 5). On a regional scale, Pudong and Chongming together account for nearly half of the city’s idle land, making them the most concentrated areas in the study region. The five districts of Jiading, Songjiang, Qingpu, Fengxian, and Jinshan collectively account for approximately 40%, while Minhang and Baoshan have relatively smaller amounts. At the township level, some townships on the outskirts of urban expansion, such as Chuansha and Pujiang in the outer suburbs, and Zhujiajiao in the hinterland, have large amounts of idle land. This is attributed to the combined effects of population outflow and land use restrictions. Consequently, rural hinterlands emerge as hotspots of idle homesteads, reflecting a mismatch between population shifts and land-use changes during urban development.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of long-term vacant homesteads across townships.

The distribution of perennial idleness rates further emphasizes disparities in homestead utilization efficiency. The citywide average vacancy rate is 17.25%, with higher rates in the southeast and lower rates in the northwest. At the district level, Pudong has the highest vacancy rate at 37.51%, while Jiading, Songjiang, Minhang, and Baoshan range between 10% and 20%. At the township level, rural areas in the hinterland, such as Huinan, Laogang, and Shuyuan in Pudong, exhibit year-round vacancy rates exceeding 40%. Townships like Huating and Xuxing in Jiading, as well as Dongjing and Chedun in Songjiang, also display moderately high vacancy levels. It shows how urban fringe zones, affected by ongoing population migration and slow land transformation, face grave issues with rural homestead vacancy.

The citywide average density of long-term idle homesteads is 1.72 ha/km2. At the district level, Pudong (5.20 ha/km2) and Jiading (2.05 ha/km2) surpass the citywide average and can therefore be identified as high-density idle zones, while other districts have comparatively sparse distributions. At the township level, areas such as Huinan and Laogang in Pudong, as well as Huating and Xuxing in Jiading, show density values above 7 ha/km2, with several exceeding 10 ha/km2, demonstrating clear clustering patterns. Overall, the spatial distribution of idle homestead density partly overlaps with the long-term vacancy rate. High-density areas often coincide with high vacancy rates, reflecting the combined effects of population outflow and inefficient land use.

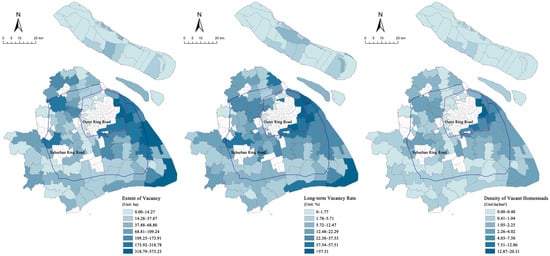

3.2. Spatial Agglomeration and Hotspot Characteristics

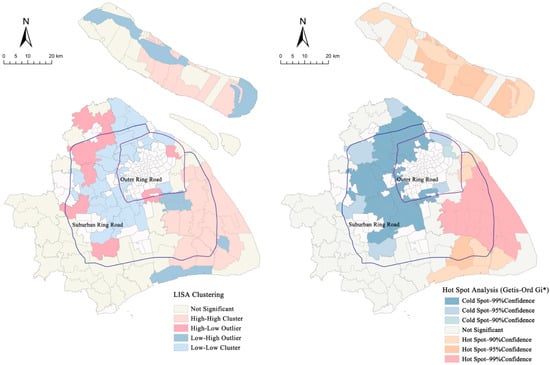

A global spatial autocorrelation analysis is conducted using ArcGIS 10.8. The Z-score for Moran’s I was 10.68, with a p-value < 0.01. All results passed the 1% significance test, indicating a high level of significance (p = 0.54). This suggests that long-term idle homesteads in the study area exhibit strong spatial clustering (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of spatial clustering characteristics.

Local spatial autocorrelation results further reveal spatial clustering patterns, identifying four types of spatial associations: high-high, low-low, high-low, and low-high. The results are primarily characterized by high-high and low-low clusters, indicating that idle homesteads generally show positive spatial correlation. In other words, areas with high proportions of idle homesteads are typically surrounded by townships with similarly high levels of idleness, while areas with low proportions tend to be near other low-value areas. High-high clusters are mainly concentrated in Pudong New District, with a few located in Chongming. These areas exhibit high vacancy rates, and neighboring townships display similar conditions, forming typical high-value clusters. Low-low clusters are mainly found in the suburban regions of Jiading, Baoshan, and Minhang, where land-use efficiency is relatively high, and vacancy rates remain low. In addition, a small number of townships exhibit high-low and low-high clusters, reflecting local variations and showing spatial negative correlation. Sanlin Town in the Pudong New Area shows a high-low pattern because it borders the central urban area, and its administrative boundary includes the Dongming Road Subdistrict. Historically, Dongming Road Subdistrict was separated from Sanlin due to urbanization, creating an intertwined spatial structure that contributes to this high-low association.

The hotspot analysis further reveals that idle homestead distribution hotspots are mainly located in remote suburban areas, such as Pudong and Chongming. Hotspots with a 99% confidence level comprised the largest share, followed by those with 95% confidence. Meanwhile, cold spots formed around the edges of the central urban area in nearby suburban areas. Overall, the spatial locations of hot and cold spots closely correspond to the areas identified as high-clustering and low-clustering regions. Hotspots tend to occur in regions with significant population outflow, limited industrial support, and weaker infrastructure. Coldspots are often found in areas with industrial agglomeration, convenient transportation, and well-developed public services. Nonetheless, a small number of mismatches occur between hotspot and cluster results, reflecting variations in local functional characteristics, demographic conditions, and land-use patterns.

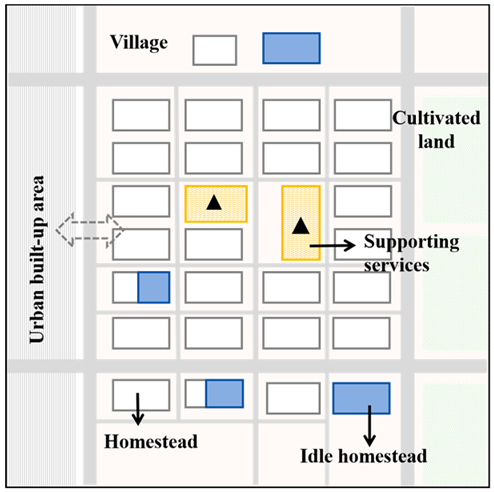

3.3. Regional Differentiation Patterns of Homestead Idleness

To further reveal the spatial heterogeneity of idle homesteads, this study employs two key indicators: the long-term vacancy rate and the density of vacant homesteads. These are applied to classify the land into high and low groups through quantile classification. By combining these two dimensions, four composite types are identified: dispersed-inefficient, high-density accumulation, sparse-stable, and intensive-efficient. This typology aligns with field survey observations, and the specific classification criteria are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Typology characteristics and spatial differentiation of idle homestead regions.

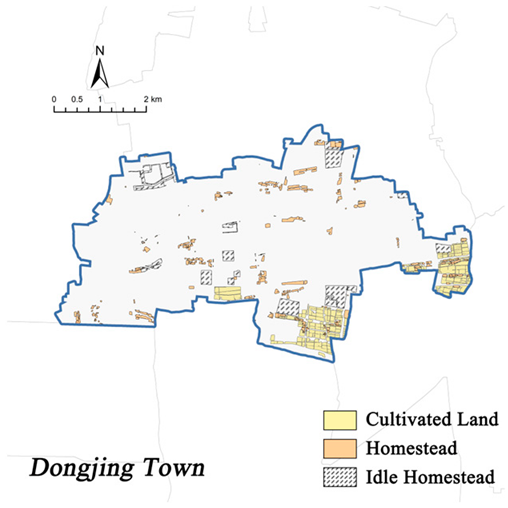

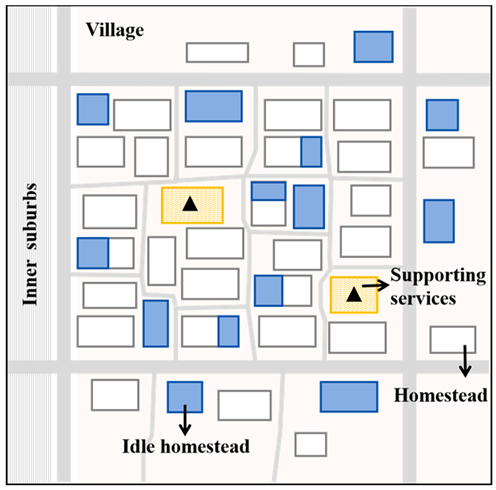

The dispersed-inefficient type is characterized by low homestead density and high vacancy rates, primarily found on the remote suburban fringes and in outer hinterland areas. These locations typically exhibit irregular spatial patterns, a high proportion of vacant plots, and low utilization efficiency. Representative examples include Nanhui New Town in Pudong, Dongjing in Songjiang, and Haiwan in Fengxian. Due to their distance from urban center, these areas struggle with weak industrial growth, limited public services, and a steady outflow of rural residents. At the same time, the number of migrant workers moving in remains low. It has led to a long-standing surplus of homestead supply compared to actual occupancy demand, creating a persistent pattern of land without corresponding population. Taking Nanhui New Town as an illustrative example, it serves as a policy enclave within the broader development of Lingang New City. It encounters challenges, including relatively diminished locational advantages, significant shifts in population structure, and insufficient local employment opportunities. Severe population outflow occurs in certain areas, while homesteads left over from large-scale land acquisitions in earlier stages remain outside the urban functional transformation system, keeping homestead vacancy rates persistently high.

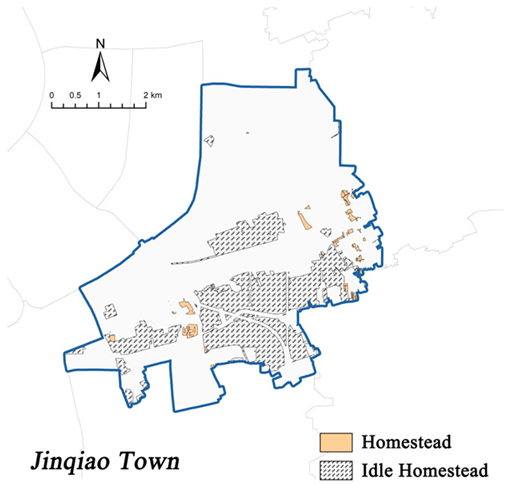

The high-density accumulation type combines high homestead density with high vacancy rates, primarily located in inner and outer suburbs. Typical examples include Jinqiao Town and Gaoxing Town in Pudong. While these areas enjoy prime locations, convenient transportation, strong local industries, and significant population potential, many homestead plots remain unused. The main reason is the widespread expectation of demolition and restrictions on property rights. Many villagers, anticipating future expropriation or redevelopment, hesitate to invest in maintenance or reuse, leading to neglect and prolonged periods of idleness. Furthermore, dilapidated houses cannot be effectively renovated due to strict policy restrictions and thus fail to meet basic living standards. This creates clusters of homes that remain densely packed but are functionally outdated, stuck in a high-density, low-efficiency state despite their advantageous locations. This shows that even in areas near central urban zones and at the forefront of urban growth, homesteads may still be underused without supportive policies and market integration.

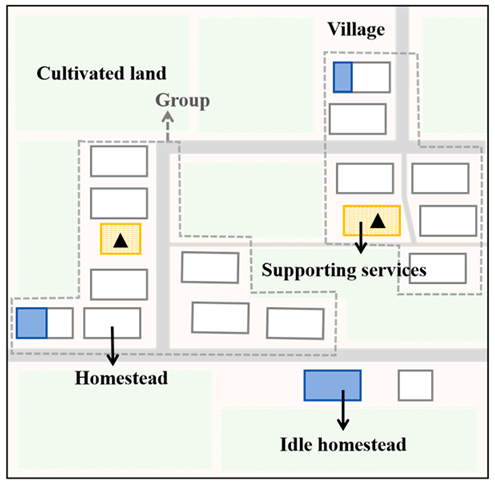

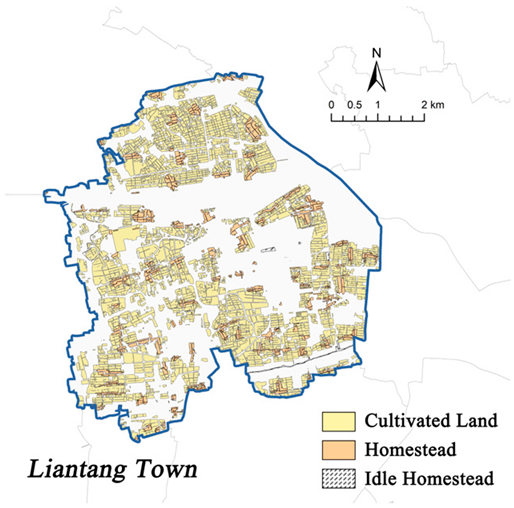

The sparse-stable type features low homestead density and low vacancy rates, typically found in ecological protection zones or regions with strong agri-tourism development in the hinterland, where overall utilization remains steady. For example, areas such as Zhujing in Jinshan District, Liantang in Qingpu District, and Xinbang in Songjiang District are often influenced by ecological conservation, historical preservation, or the integration of agri-tourism. In these areas, land use is strictly regulated by environmental or cultural policies that limit new development while also helping protect existing structures and promote adaptive reuse. The integration of agritourism and eco-recreation further supports operational sustainability and minimal vacancy rates of rural homesteads. Taking Liantang Town as an example, its agritourism integration model effectively revitalizes limited homestead resources, enabling continuous use through tourism services, homestays, and cultural exhibitions, thereby maintaining a low vacancy rate and a stable utilization pattern.

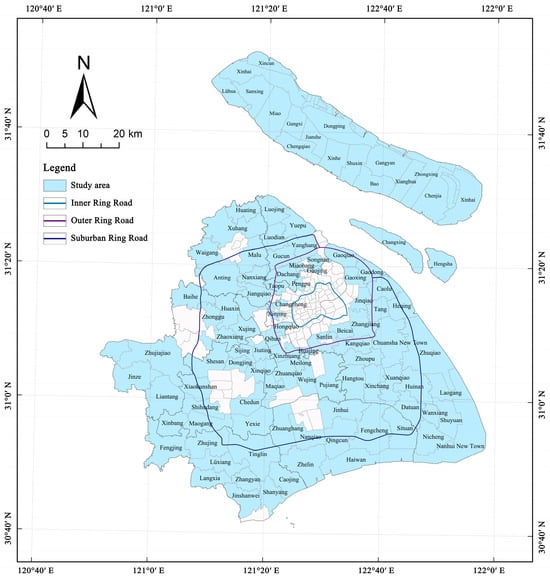

The intensive-efficient type is characterized by a high homestead density and low vacancy rates, mainly located around mature new town development zones in outer suburban and hinterland regions. For instance, Qingpu’s Huaxin Town and Fengxian’s Sitang Town exemplify this pattern. Their homestead resources are closely integrated with regional core functions and utilize transportation networks to manage spillover demand from adjacent areas. Robust industrial clusters support a sizable and stable workforce, resulting in homestead utilization rates well above the municipal average. This efficient and compact utilization model exemplifies a development approach shaped by both policy incentives and market demand, offering valuable insights for enhancing homestead allocation and revitalization in other regions.

3.4. Quantitative Analysis of Driving Factors

The Geodetector analysis (Table 3) identifies demographic hollowing and agricultural efficiency as dominant drivers, revealing a clear hierarchy of influence:

Table 3.

Identification results of dominant factors of homestead idleness.

First, demographic transition acts as the primary stressor. The population aging rate (X2) exerts the strongest explanatory power (q = 0.284), identifying intergenerational imbalance as the critical driver. Coupled with population outflow (X1, q = 0.210) and density (X3, q = 0.197), this confirms that depopulation directly erodes the utilization basis of settlements. Intense outmigration fosters abandonment, while sparsely populated regions succumb to widespread village hollowing [48].

Second, economic viability determines sustainability. Per capita agricultural output (X9, q = 0.283) and cultivated land density (X11, q = 0.231) follow closely, suggesting that low profitability weakens maintenance incentives [42]. Furthermore, livelihood dependency (X10, q = 0.184) highlights structural vulnerability: non-diversified villages are prone to decay [49]. Regarding land resources, the arable-to-settlement ratio (X5, q = 0.206) confirms that natural endowments impose rigid spatial constraints [37].

In contrast, location and policy factors exert secondary influence. Variables such as distance to city center (X7), consolidation intensity (X12), development intensity (X6), and motorway distance (X8) act mainly as indirect conditions. Crucially, the homestead withdrawal pilot (X13) yielded a negligible impact (q = 0.017) and failed the significance test. This offers a profound insight: without complementary economic incentives, isolated top-down pilots function merely as nominal labels rather than effective levers against market forces [50]. Effective intervention requires “bundling” policy with economic advantages.

4. Discussion

4.1. Synergistic Effects of Driving Factors

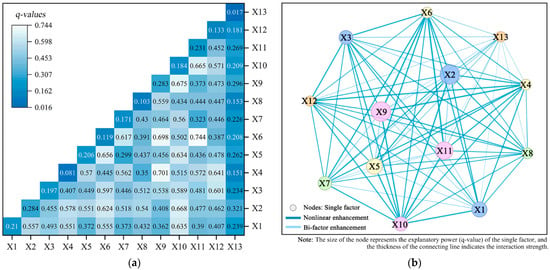

The interaction detector was employed to examine the combined effects of potential drivers and driving mechanisms (Figure 7). The results show a consistent pattern: the interaction between any two factors yields a higher q-value than either factor alone. Most combinations demonstrate nonlinear enhancement. This confirms that homestead idleness is not caused by a single variable. Instead, it results from the complex interplay of multiple factors. Three key mechanisms emerge from this network structure.

Figure 7.

Interaction heatmap and network graph of influencing factors: (a) Interaction detector heatmap; (b) Interaction network analysis.

First, interactions involving economic factors exert the strongest influence, particularly when coupled with land and demographic variables. The high interaction between per capita agricultural output and livelihood dependence (X9 ∩ X10, q = 0.675) underscores that internal agricultural synergies are critical for homestead stability. Meanwhile, the interaction with population aging (X2 ∩ X10) reveals a significant demographic amplification, suggesting that agricultural reliance dictates intervention intensity in an aging society. Most notably, the “strong coupling” of development intensity and cultivated land density (X6 ∩ X11) peaks at a q-value of 0.744, representing the dominant driving pattern of current idleness.

Second, spatial constraints are compounded by economic dependencies. The interaction between the distance to the city center and livelihood dependence (X7 ∩ X10) confirms a mechanism of “dual constraints”: in areas suffering from both locational disadvantages and high agricultural reliance, homesteads are structurally trapped in inefficient utilization [51].

Third, a significant policy-bundling effect is evident. Single-factor analysis showed that the homestead withdrawal pilot (X13) had a negligible direct impact. Yet, its interaction with economic factors (X13 ∩ X1) reveals substantial nonlinear enhancement. This proves that isolated institutional interventions fail to address the root causes of vacancy [28]. Policy tools work as effective multipliers only when “bundled” with economic incentives. This aligns with the limitations of independent land bank initiatives observed in Japan [52,53].

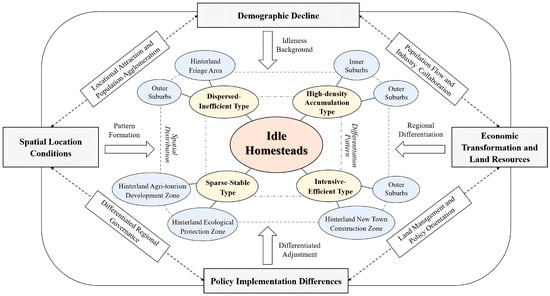

4.2. Formation Mechanism of Involuntary Idleness

Homestead idleness results from a complex mechanism driven by four interacting factors: demographic, economic, spatial, and policy dimensions (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comprehensive mechanism analysis of homestead idleness.

First, demographic decline establishes the baseline conditions for vacancies. As population aging accelerates and younger workers migrate out, a “hollowing out” effect has solidified in outer suburbs, diminishing the fundamental demand for homesteads. Second, economic transformation and land resources further propel regional differentiation. In townships with mismatched land use—where cultivated land and homestead plots are misaligned—insufficient labor leads to resource waste. Conversely, areas with robust industrial bases remain vibrant by integrating agri-tourism or secondary industries, highlighting that industrial synergy is critical for utilization.

Third, spatial location conditions exert additional influence on utilization patterns. Proximity to urban centers fosters high-density accumulation types, which often suffer from underutilization despite high potential value. In contrast, remote outer suburbs exhibit dispersed-inefficient types due to population outflow, whereas hinterlands maintain sparse-stable types supported by ecological policies. Fourth, policy factors produce uneven regulatory impacts. While policies serve as catalysts in inner suburbs with market demand, they often fail to address idleness in economically stagnant outer regions, proving that single-focus measures are limited without industrial support.

Consequently, Shanghai presents a unique “paradox of idleness”: high demand for urban land coexists with inefficient rural vacancy. Our analysis identifies the dual urban-rural land system as the definitive structural barrier. Unlike Western contexts where vacancy often reflects a lack of market demand, this institutional framework creates a rigid barrier that prevents rural homesteads from entering the formal market, even after the rural population has been urbanized. As a result, these assets are trapped in a state of “involuntary idleness”—unable to be inhabited by owners who have migrated, and legally inaccessible to external capital seeking to enter.

4.3. Uniqueness in International Comparative Context

From an international perspective, the mechanism of homestead idleness in Shanghai diverges significantly from global trends. In Japan, the phenomenon is best described as demographic asset freezing. The “Akiya” (vacant house) crisis there is driven primarily by hyper-aging and a weak resale market [17,18]. In Western contexts, vacancy is typically a symptom of market-driven abandonment. Specifically, in parts of Europe, it is often triggered by long-term rural depopulation and shrinkage [19,20,21]. Meanwhile, in the United States, it tends to result from economic restructuring and shifts in housing demand [22,23]. In the Global South, underuse is often shaped by informal speculation due to land inequality and insecure tenure [24,25]. Crucially, in most of these cases, property rights are clear, and vacancy reflects a lack of market value.

In contrast, idleness in Shanghai is not purely a market failure. Instead, it is heavily shaped by China’s specific political context and dual land system. This institutional framework creates a rigid barrier that prevents rural homesteads from entering the formal market. Therefore, unlike the “voluntary abandonment” seen in the West, Shanghai’s “involuntary idleness” represents a structurally distinct phenomenon: it is not a result of disappearing demand, but of institutional friction trapping assets despite their potential value.

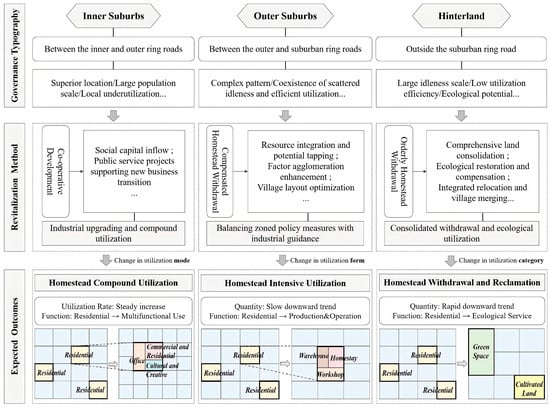

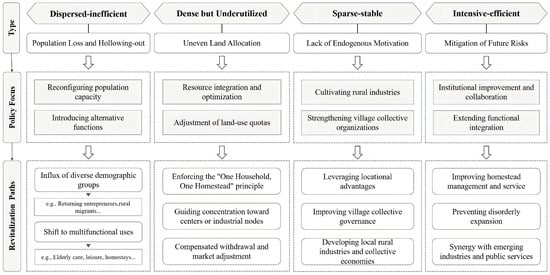

4.4. Differentiated Governance and Revitalization Strategies

4.4.1. Gradient Stratification and Spatial Identification

Governance must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. Given the spatial heterogeneity of population mobility and industrial growth, we propose a gradient-based strategy tailored to local conditions (Figure 9). In the inner suburbs, where locational advantages and population density are prominent, the strategy focuses on functional diversification. Social capital should be introduced to renovate underused homesteads into public service facilities, such as elderly care and community centers. Furthermore, policies must guide a transition from purely residential use to new business models, accommodating production and operational functions.

Figure 9.

Gradient typology.

The outer suburbs present a complex polarization requiring a dual strategy of zoning regulation and industrial guidance. For areas facing continuous depopulation, policy should facilitate spatial restructuring to boost land-use efficiency. Conversely, in regions near new towns or industrial nodes, the priority is strengthening industrial connections. Strategies should repurpose homesteads into rural innovation parks or agritourism ventures, integrating them with regional development to foster positive rural-urban interaction.

The hinterland is characterized by widespread idleness and ecological sensitivity. Governance here requires a strategy centered on withdrawal and ecological restoration. In these marginal zones, strict land-use restrictions must be enforced to safeguard the ecological red line. Simultaneous efforts should encourage compensated withdrawal and land consolidation. By leveraging natural endowments, these areas can transition toward green industries, such as wellness tourism, ensuring ecological value is realized through functional transformation.

4.4.2. Pattern Oriented Activation of Vacancy

Analysis of driving factors reveals distinct regional patterns of idleness, necessitating precise, tailored revitalization paths (Figure 10). In dispersed-inefficient areas driven by hollowing-out, the core task is reconfiguring population capacity. This involves introducing alternative functions, such as leisure retreats and guesthouses, to attract diverse groups like returning entrepreneurs and enhance market flexibility. In dense but underutilized areas suffering from resource mismatch, strictly enforcing the “one household, one homestead” principle is essential. Strategies should emphasize resource integration, using compensated withdrawal and market adjustments to steer residential plots toward central villages or industrial hubs for intensive utilization.

Figure 10.

Paths for categorized policy implementation.

In sparse-stable areas, where idleness is low but endogenous motivation is weak, revitalization depends on cultivating local industries. Strengthening village collective organizations and leveraging locational advantages can solidify the economic foundation, ensuring long-term stability. Finally, for intensive-efficient areas, the focus shifts to institutional improvement to prevent disorderly expansion or functional homogenization. Enhancing transport links and public services will foster synergistic development among homesteads and emerging industries. Additionally, in high-density accumulation zones with commercial potential, we recommend a “cooperative renewal” mechanism. By involving state-owned enterprises and village collectives, this approach ensures farmers receive sustainable dividend income, addressing reluctance to withdraw due to asset appreciation expectations.

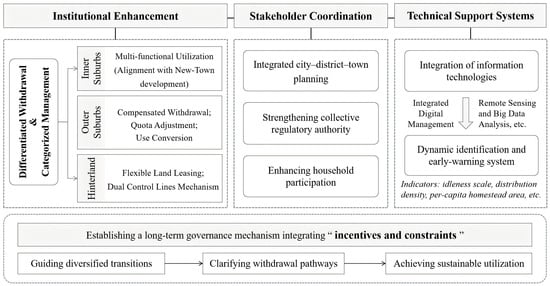

4.4.3. Collaborative Governance and Dynamic Mechanisms

Effective governance requires a multi-stakeholder collaborative mechanism integrating institutional, social, and technical dimensions (Figure 11). Institutionally, we propose a differentiated management system. Inner suburbs should establish standards for multifunctional use aligned with new town development, while outer suburbs focus on quota adjustments and use conversion. For the hinterland, we propose a “20 + 20 year” flexible leasing model inspired by agricultural tenure reforms. This balances social security with property income by setting dual thresholds for residential security and land-use restrictions.

Figure 11.

Dynamic governance mechanism.

Socially, coordination must be strengthened across city, district, and town levels to ensure functional complementarity between new urban developments and neighboring villages. Crucially, village collectives should be granted increased regulatory authority to manage dispersed land as collective resources. Furthermore, establishing a benefit-sharing mechanism is vital to incentivize farmer participation and transform passive owners into active stakeholders.

Technically, long-term governance relies on integrated digital management. Authorities should utilize remote sensing and big data analytics to establish a dynamic identification and early-warning system for idleness scale and distribution density. This system underpins a sustainable mechanism balancing incentives with constraints, clarifying permissible uses and transfer regulations to guide idle resources toward diverse, efficient, and legal applications.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Findings

This study decodes the “paradox of idleness” in megacities by systematically quantifying the spatial differentiation and driving mechanisms of rural homestead vacancy in Shanghai. The key findings are threefold:

First, homestead idleness follows a distinct core-periphery gradient rather than a random distribution. The identification of four regional typologies—dispersed-inefficient, high-density accumulation, sparse-stable, and intensive-efficient—challenges traditional “one-size-fits-all” regulations, confirming that idleness manifests through divergent pathways across peri-urban contexts.

Second, demographic hollowing and low agricultural efficiency are identified as the dominant stressors. Crucially, the analysis reveals the failure of isolated institutional interventions, with the homestead withdrawal pilot accounting for a negligible fraction of variance. Instead, a significant policy-bundling effect is confirmed, where institutional tools achieve nonlinear efficacy only when synergized with economic incentives and locational advantages.

Third, the mechanism of idleness in Shanghai is redefined as “involuntary vacancy” caused by institutional friction. Unlike market-driven abandonment, this phenomenon traps assets in a cycle of decline due to the rigid duality of the land system preventing market circulation. Consequently, the proposed “gradient governance” framework provides a transferable strategy for the Global South, advocating a shift from uniform control to differentiated spatial restructuring aligned with local developmental realities.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

While this study systematically reveals the spatial patterns and drivers of homestead idleness, further exploration in the following areas could deepen the understanding of the underlying mechanisms. First, regarding methodology, although the optimal quantile method was applied to maximize statistical power, the Geographical Detector’s inherent discretization of continuous variables may still introduce sensitivity to zoning scales. Future research could employ multi-scale sensitivity analysis to further verify the robustness of these spatial determinants. Second, the reliance on macro-spatial statistics limits the visibility of micro-level behavioral logic. Specific motivations, ranging from ancestral sentiment to speculative holding, remain difficult to distinguish solely through spatial data. Future work should integrate household surveys and sociological interviews to effectively link these macro-spatial patterns with individual decision-making processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L. (Kaiming Li), K.L. (Kaishun Li), L.W. and L.Y.; methodology, K.L. (Kaishun Li), L.W. and L.Y.; investigation, K.L. (Kaiming Li), L.W. and L.Y.; resources, K.L. (Kaishun Li); data curation, L.Y. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L. (Kaiming Li) and L.W.; writing—review and editing, K.L. (Kaishun Li) and L.W.; funding acquisition, K.L. (Kaiming Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been sponsored by the National Social Science Fund of China (24BGL203).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Building New Countryside in China: A Geographical Perspective. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Introduction to Land Use and Rural Sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Feng, C. The Redundancy of Residential Land in Rural China: The Evolution Process, Current Status and Policy Implications. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Long, H. The Process and Driving Forces of Rural Hollowing in China under Rapid Urbanization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Kong, X.; Jiang, P. Identification of the Human-Land Relationship Involved in the Urbanization of Rural Settlements in Wuhan City Circle, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Huang, S. Withdrawal Intention of Farmers from Vacant Rural Homesteads and Its Influencing Mechanism in Northeast China: A Case Study of Jilin Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J. Determinants and Governance of Unused Rural Residential Bases in the Context of Rural Revitalisation in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J. Evolutionary Process and Mechanism of Population Hollowing out in Rural Villages in the Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China: A Case Study of Yanchi County, Ningxia. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, X. Exploring the Multidimensional Hollowing of Rural Areas in China’s Loess Hilly Region from the Perspective of “Population Outflow”. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2025, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-Dimensional Hollowing Characteristics of Traditional Villages and Its Influence Mechanism Based on the Micro-Scale: A Case Study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Fu, C.; Kong, S.; Du, J.; Li, W. Citizenship Ability, Homestead Utility, and Rural Homestead Transfer of “Amphibious” Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Hou, L.; Jia, B.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, X. Effect of Policy Cognition on the Intention of Villagers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads. Land 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, L. Social Capital for Rural Revitalization in China: A Critical Evaluation on the Government’s New Countryside Programme in Chengdu. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Song, G.; Hu, Z.; Fang, J. An Improved Dynamic Game Analysis of Farmers, Enterprises and Rural Collective Economic Organizations Based on Idle Land Reuse Policy. Land Use Policy 2024, 140, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A Novel Framework for Rural Homestead Land Transfer under Collective Ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Lin, Y. Rural Spatial Transformation and Governance from the Perspective of Land Development Rights: A Case Study of Fenghe Village in Guangzhou. Growth Change 2022, 53, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadayuki, T.; Kanayama, Y.; Arimura, T.H. The Externality of Vacant Houses: The Case of Toshima Municipality, Tokyo, Japan. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2020, 50, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Hino, K.; Muto, S. Negative Externalities of Long-Term Vacant Homes: Evidence from Japan. J. Hous. Econ. 2022, 57, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubeaux, S.; Cunningham Sabot, E. Maximizing the Potential of Vacant Spaces within Shrinking Cities, a German Approach. Cities 2018, 75, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, D.; Behnisch, M.; Jehling, M.; Michaeli, M. Mapping Soft Densification: A Geospatial Approach for Identifying Residential Infill Potentials. Build. Cities 2023, 4, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Madurga, M.-Á.; Esteban-Navarro, M.-Á.; Saz-Gil, I.; Anés-Sanz, S. Depopulation and Residential Dynamics in Teruel (Spain): Sustainable Housing in Rural Areas. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, R. Long-Term Vacant Housing in the United States. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2016, 59, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Deller, S. Effect of Farm Structure on Rural Community Well-Being. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B.; Niminga-Beka, R. Urbanisation in Ghana: Residential Land Use under Siege in Kumasi Central. Cities 2017, 60, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, F.; Wegayehu, F.; Mulugeta, S. Drivers of Informal Settlements at the Peri-Urban Areas of Woldia: Assessment on the Demographic and Socio-Economic Trigger Factors. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-Based Rural Residential Land Consolidation and Allocation Can Help to Revitalize Hollowed Villages in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The Functional Value Evolution of Rural Homesteads in Different Types of Villages: Evidence from a Chinese Traditional Agricultural Village and Homestay Village. Land 2022, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Fang, L. The Impossible in China’s Homestead Management: Free Access, Marketization and Settlement Containment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q. The Functional Evolution and Dynamic Mechanism of Rural Homesteads under the Background of Socioeconomic Transition: An Empirical Study on Macro- and Microscales in China. Land 2022, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Ge, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhai, R. Withdrawal and Transformation of Rural Homesteads in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China Based on Supply-Demand Balance Analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 897514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Duan, K.; He, F.; Si, Y. The Effects and Mechanisms of the Rural Homestead System on the Imbalance of Rural Human–Land Relationships: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration in China. Land 2024, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, D. Striving for Global Cities with Governance Approach in Transitional China: Case Study of Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z. Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: A Survey in Zhejiang, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T. Behavioural Selection of Farmer Households for Rural Homestead Use in China: Self-Occupation and Transfer. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, M.; Lo, K. Estimating Housing Vacancy Rates in Rural China Using Power Consumption Data. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yu, B.; Chen, Z.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, J. A Spatial-Socioeconomic Urban Development Status Curve from NPP-VIIRS Nighttime Light Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Q. Revitalization of Idle Rural Residential Land: Coordinating the Potential Supply for Land Consolidation with the Demand for Rural Revitalization. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Jin, X.; Gan, L.; Jessup, L.H.; Pijanowski, B.C.; Lin, J.; Yang, Q.; Lyu, L. Dynamics of Spatial Associations among Multiple Land Use Functions and Their Driving Mechanisms: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The Impact of Land Consolidation on Rural Vitalization at Village Level: A Case Study of a Chinese Village. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Yang, K.; Qu, X. The Spatial Features and Driving Mechanism of Homestead Agglomeration in the Mountainous and Hilly Areas of Southwestern China: An Empirical Study of 22 Villages in Chongqing. Land 2022, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tian, L.; Yao, Z. Institutional Uncertainty, Fragmented Urbanization and Spatial Lock-in of the Peri-Urban Area of China: A Case of Industrial Land Redevelopment in Panyu. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Lyu, X.; Gu, G.; Zhou, X.; Peng, W. Sustainable Intensification of Cultivated Land Use and Its Influencing Factors at the Farming Household Scale: A Case Study of Shandong Province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, M. Impact of Housing Conditions on Resident Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads and Preferences Regarding Compensation and Resettlement Mode: A Dual-Sample Selection Model. Habitat Int. 2025, 166, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kang, C.; Yin, C.; Tang, J. Influence of Transportation Accessibility on Urban-Rural Income Disparity and Its Spatial Heterogeneity. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Lin, T.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhu, W. Spatial-Temporal Characteristics and Transfer Modes of Rural Homestead in China. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fang, J. Exploring the Disparities in Park Access through Mobile Phone Data: Evidence from Shanghai, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, T. Impact of Megacity Jobs-Housing Spatial Mismatch on Commuting Behaviors: A Case Study on Central Districts of Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Yue, L.; Jiang, X. Transition Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in Suburban Villages of Megacities under Policy Intervention: A Case Study of Dayu Village in Shanghai, China. Land 2023, 12, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Q.; Marcouiller, D.W.; Chen, J. Understanding the Underutilization of Rural Housing Land in China: A Multi-Level Modeling Approach. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 89, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yin, L.; Zeng, Y. How New Rural Elites Facilitate Community-Based Homestead System Reform in Rural China: A Perspective of Village Transformation. Habitat Int. 2024, 149, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Geng, H.; Yue, L.; Li, K.; Huang, L. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Rural Settlements Transformation in the Metropolis: A Case Study of Pudong District, Shanghai. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 755207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Lee, I.; Gkartzios, M. Overview of Social Policies for Town and Village Development in Response to Rural Shrinkage in East Asia: The Cases of Japan, South Korea and China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Shimizu, Y. Innovative Land Bank Models for Addressing Vacant Properties in Japan: A Case Study of Six Approaches. Land 2025, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.