Abstract

This study investigates the integration of forestry into strategic planning across territorial levels in the context of the bioeconomy, using the Czech Republic as a case study of an EU member state. This is examined through a qualitative content analysis of regional and territorial local plans, to identify which topics are associated with forestry (n = 67). Using the example of a private forest owner, the specific implementation is then shown. To gather feedback on the assessed strategic documents, we compared economic results for state, municipal, and private forest owners. The research assumption is that the lower the territorial local level, the greater the importance local governments attach to forestry. The main featured topics are the water regime, sustainable forestry, biodiversity support, climate change, maintenance infrastructure, social functions, and economic competitiveness. The results show that the assumption that the lower the territorial planning level, the more forestry is featured in strategies was not confirmed. The relationship is rather the opposite. The presented economic results clearly demonstrate that financial contributions to forest management are a logical consequence of policies. These results correlated with those of the content analysis. The multi-level approach and use of economic data provide valuable empirical depth, and the main finding challenges common assumptions about policy emphasis at lower governance levels.

1. Introduction

Over the years, forestry has developed in response to historical, political, and cultural developments. Today, we can define forestry, according to [1], as the profession embracing science, art, and the practice of creating, managing, using, and conserving forests and associated resources for human benefit in a sustainable manner to meet desired goals, needs, and values.

Forestry includes a whole range of related disciplines, including forest policy. This can be defined as an analytical political process that includes formulating the goals of human activity in the care and use of forests, and implementing them through feedback ratings [2]. At the beginning of this process, there are various conflicts of interest (such as forest products and services and forests as part of the landscape and the environment), which should be regulated through relevant programs (or a set of plans). For this purpose, forest policymakers work with information tools (consulting, education, research, public relations, regional forest management plans, etc.), economic instruments (e.g., financial subsidies, management and marketing, and evaluation and certification), and regulatory instruments (legal norms/legislations, strategies, forest management plans, regulations, directives, etc.).

It is through forest planning that forest policy objectives take concrete form. According to [3], the concept of forest management planning has evolved over centuries in a highly holistic manner as societal expectations for forests’ roles have diversified. The basic tool of forest management planning is a management plan. This can be defined as a predetermined course of action and direction to achieve a set of results, usually specified as goals, objectives, and policies [1].

The objectives of forest planning can be diverse, from setting strategic visions to assessing the current state of the forest, identifying the results and outputs of forest management, and setting political goals [3].

According to [3], the hierarchy of forest planning is generally based on the objectives of the national forest policy, reflected in the regional strategy forest plan, which in turn shapes the forest management plan. Here, the objectives are applied mainly through the forest owner, specifically through the operational plan, which determines a schedule of specific activities, based on the implementation plan, that are then carried out (realized).

In contrast, the available literature offers many definitions of regional development, varying in their degree of specificity. According to [4], regional development is a set of activities aimed at improving the economic well-being of a territory and the quality of life of its inhabitants. These activities may include economic strategies, research, entrepreneurship, the labor market, technological innovation, political lobbying, and the development of the social and environmental areas. More specific examples include understanding regional development as an effort to reduce social inequalities and promote environmental sustainability, inclusive governance, and cultural diversity, as explained in [5].

In the context of this study, we consider regional development as a set of activities on which local actors agree to contribute to the region’s development across environmental, economic, and social dimensions.

We focus on the strategic-planning dimension of regional development because strategic documents at supranational, national, regional, local, and municipal levels shape the priorities and directions for territorial development, including the position and expected contribution of forestry. Understanding how these documents articulate forestry-related objectives is therefore essential for assessing the role forestry is expected to play in regional development.

In this study, we focus on the forest-based component of the broader bioeconomy, namely the part that relies on forestry and forest-based value chains. This focus is important because forestry is a core pillar of the bioeconomy, providing renewable biomass for material and energy uses, contributing to climate change mitigation, generating employment and income in rural areas, and maintaining key ecosystem services [6,7,8]. Clarifying this role allows us to examine how strategic documents reflect the potential of forestry to support sustainable regional development.

Although previous research has analyzed forest- and bioeconomy-related strategies at the European Union and national levels or within individual regions [9,10,11], there remains a lack of systematic comparisons that examine how forestry and the forest-based bioeconomy are incorporated into strategic development documents across multiple governance levels—international, national, regional, and municipal—within a single EU member state. Addressing this gap is crucial for understanding how consistently (or inconsistently) the expected contribution of forestry is framed across territorial levels and how this alignment shapes regional and municipal development priorities.

The analysis identifies several forestry-related themes that appear across governance levels; these themes are derived inductively from the content analysis and are described in detail in the Methods section.

Instead of formulating a formal, testable hypothesis, we draw on general principles commonly discussed in regional development and public administration, such as subsidiarity, decentralization, and the integration of local knowledge [12,13]. These principles suggest that lower territorial levels may place greater emphasis on sectoral issues with strong territorial and socio-economic relevance, including forestry. We therefore use this as an analytical expectation that helps us interpret how forestry-related topics resonate across supranational, national, regional, and municipal strategic documents, rather than as a hypothesis to be tested.

From the point of view of analysis at the European Union (hereinafter referred to as the EU) member-state level, it is possible to describe the anchoring of spatial and regional planning with an impact on forestry in a selected member state. As an example, a Central European state is the best choice. The Czech Republic (hereinafter, CZ) was selected for this case study.

In the context of the analysis defined in the introduction, we focused more closely on investigating which topics related to forestry and the forest-based bioeconomy are emphasized at different territorial levels (n = 67) and address the following research questions:

- ○

- RQ1: How is forestry included in strategic development plans at the supranational, national, regional, local, and municipal levels?

- ○

- RQ2: How does this specifically affect the forest bioeconomy, and what are its impacts?

- ○

- RQ3: How does forestry planning specifically reflect the regional development requirements of these documents?

The research questions presented are examined through a methodological approach of a content analysis of selected conceptual documents.

2. Theoretical Framework

Forestry is common in rural areas, where it contributes to local economic and social development [14]. In [15], the use of different theories of regional development for the forest-based sector was examined at national, regional, and local levels.

The conclusions of those presented in [15] show that no theory alone can fully capture the specific characteristics of the forest-based sector. Local conditions and the influence of policies and human activities, which vary from region to region, need to be considered in forestry development. Therefore, a single theoretical framework cannot be used. According to [16], sustainable forest use contributes to the socio-economic development of rural areas. In the long term, there is a need to focus more on adopting sustainable production methods that reconcile economic, social, and environmental interests.

The European Commission [17] defines rural development as part of the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy. It sees rural development through this pillar as an effort to increase the competitiveness of agriculture and forestry, ensuring sustainable management of natural resources and climate action, and achieving balanced territorial development of rural economies and communities, including job creation and retention.

In addition to financial instruments, strategic and spatial planning are important for rural development. This study focuses exclusively on strategic planning, which is often confused with spatial planning (as noted, for example, in [18]). In addition, strategic spatial planning also exists, which was defined by [19] as a process through which a variety of public and private actors with a stake in the region—such as public-sector planners, politicians, private land holders, and organizations representing community and environmental issues—come together in diverse institutional settings to prepare strategic plans by developing interrelated strategies for the management of spatial change. Strategic documents can often lead to changes in the spatial plan. This also works the other way around, with the spatial plan serving as a guide for creating a strategic plan [20].

According to [21], strategic planning and spatial planning are different but complementary tools for territorial development. Strategic planning focuses on why a municipality wants to develop, specifically on the content and direction of that development. It is a voluntary process, grounded in the local government’s powers, aimed at setting a vision, priorities, and specific steps to improve people’s quality of life or strengthen the local economy. Strategic planning is not legally mandatory, but municipalities are subject to detailed regulation [22].

According to this, rural development is a deliberate and coordinated process that aims to permanently improve the quality of life of residents in rural areas. This process is comprehensive—it includes economic, social, environmental, and cultural components. It is a set of investments, policies, and activities that support sustainable agricultural operations, diversify the local economy, develop infrastructure and services, and strengthen local communities’ participation in determining the direction of their region.

This study focuses on strategic plans and their implementation in forestry. This field has already been the subject of research by several authors, using examples from the European area (e.g., [9,23,24,25,26]).

The authors of [27] studied how different European regions manage and implement forestry strategies within the broader bioeconomy, focusing on the level of societal involvement. Their findings show that forestry strategies are more often developed and implemented at the regional level rather than the national level, reflecting the specific needs and opportunities of each region. They also identified that the involvement of NGOs, civil society, and the wider public is limited in the implementation of these strategies.

The authors of [28] emphasized that to achieve the true sustainability of forest resources, it is necessary to improve the quality and availability of data used for decision-making. Cooperation between member states and regional authorities is key in this regard.

The authors of [6] recommend increasing public support and attention to forestry. In this study [27], there is a need to increase the use of forestry’s potential for regional development.

The authors noted in [7] that integrating ecological, economic, and social aspects into strategic decision-making for forest resource management is necessary.

According to [29], foreign direct investment can also play a strategically important role and should be encouraged. These investments can be directed towards the development of plantations, processing plants, paper and pulp production, and other forestry-related sectors.

The importance of government plans, policies, and public support, especially at the regional and local level, for the long-term sustainable development of forestry is emphasized in [10]. These plans are usually formalized in strategic documents.

A key opportunity for strategic forestry in the circular bioeconomy, particularly through national-level policy support, is outlined in [8]. This support includes increased funding for research and innovation, the development of supporting policies, and the strengthening of environmental measures such as carbon taxation. The authors identified a lack of objectives for forest development and insufficient cooperation and knowledge sharing as challenges in strategic planning.

On the contrary, forest planning usually includes several different types of plans. According to [3], the hierarchy of forest plans is based on an implementation plan, which sets out in detail how each operation in each area will be carried out. Overarching this is an operational plan, which determines and schedules activities needed in each part of the forest and allocates resources based on the forest management plan (it is usually prepared for a period of 10 years, with a tolerance of ± 5 years, and is usually mandatory according to the legislation of the given state). This is considered the most important strategy and includes a set of objectives for the concrete forest management unit, along with the actions needed to achieve them.

The forest management plan is based on the regional strategy forest plan, which is usually prepared by a regional government or a designated state institution. It contains sets of strategic plans for forest products and services, forest industries, and land use allocation.

Forest policies or strategies are usually prepared at the national level and are the basis for a regional strategy forest plan. They contain sets of national-level objectives for forests and their goods and services. Within the EU member states, this is usually based on a combination of national requirements and the European Commission’s forestry policy. Action plans for these policies are further developed to specify national and EU forestry policies.

In addition, so-called National Forest Programmes were formulated at the continental level (Pan-European Process) and constitute a comprehensive social and political framework for achieving sustainable forest management at the country level, in accordance with each country’s national conditions, objectives, and priorities [30].

Strategic documents on bioeconomy within the EU have been studied in [11], among others. The authors state that each EU country emphasizes the importance of the bioeconomy in several of its annual reports, including those on the state of forests and forestry. They also demonstrate this importance by allocating financial resources to support the bioeconomy. However, their analysis has shown that perceptions and definitions of the bioeconomy vary from country to country. This is also confirmed, for example, in [9].

Regional forest strategy plans, as special strategic documents, are used by forest owners and municipal representatives, and they serve as a basis. When we understand this as a tool of forestry policy, it should be implemented in line with subsidiarity, i.e., decision-making and responsibility should take place at the lowest possible administrative level and as close as possible to citizens. According to Yamada [31], regional forest planning can enable participatory planning involving various stakeholders and decision-makers, and participatory models can serve as tools to support such an approach. The main objectives of these methods are to integrate knowledge and harmonize stakeholder views. Subsidiarity should then be ensured by the territorial plan itself, which is usually publicly presented during legislative processes and subsequently validated. Subsidiarity is perceived here as the opposite of centralism and should support decentralization and self-government. Forest management plans and territorial plans should ensure integration. They are built on specific local knowledge (especially regarding the characteristics and specifics of natural conditions, social requirements, e.g., protection, nature, ownership requirements, environmental limits, and resources: economic, social, technical, etc.). At the local level, the most hierarchically important documents are the forest management plan and the municipality’s territorial plan.

This study features relevant concepts with an impact on forestry at individual territorial levels. First, the national and supranational levels (here understood as the EU level, i.e., valid for all EU member states) were analyzed, followed by local and municipal concepts, and community-led local development strategies within local action groups (hereinafter referred to as LAGs, in the plural). According to [32], LAGs are defined as a myriad of public, business, and non-profit sectors, such as neighborhood associations, municipalities, third-sector organizations, and economic, educational, and religious institutions. LAG partners reflect intrinsic territorial specificities, e.g., agricultural associations will be strong in rural LAGs.

The strategies, conventions, policies, or intentions themselves also reflect changing environmental conditions. Their driving forces are natural disturbances and geopolitical events. The latter also occurs as an indirect effect on the owners and of what they enforce. They are incorporated into strategies, conventions, intentions, policies, and subsequently into legislation.

Regional forestry development from a bioeconomy perspective can be well illustrated by a forest property with diverse natural conditions, including lowlands, midlands, and mountains. This fully represented the natural conditions and different influences from land use (protected area, proximity to a large city or agglomeration).

For comparison, it is appropriate to look for the difference between a state owner and a private owner. A private forest owner may be less susceptible to societal or other state pressures and requirements. The decision-making of private forest owners is considered freer and better illustrates the economic efficiency of management; it is less constrained by legislation than that of state forests.

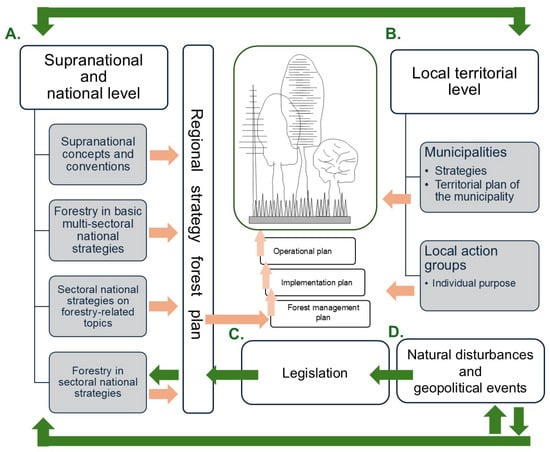

A conceptual diagram illustrating the expected relationship among governance level, planning tools, and thematic emphasis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual diagram visualizing the methodological approach, conducted through the content analysis of selected conceptual documents with respect to legislation and the impact of natural disturbances and geopolitical events.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Czech Republic as a Study Area

The CZ is a country in the heart of Europe. It has an area of 78,866 km2 and a mean altitude of 430 m. The CZ is an exemplary state with deep roots in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (covering more than seven countries in today’s EU), which was subsequently affected by the First and Second World Wars and later experienced the rise of communism, which was ended by a coup. This state later became an EU member state. Of the 27 members, 10 countries joined in 2004. According to [33], the CZ can be understood as an average country with adequate forest cover, forest productivity (amount of wood in m3 per 1 ha), and economic results.

The CZ is designated as the representative EU member state based on its natural conditions, encompassing three biogeographic regions (Alpine, Pannonian, and a significant portion of continental regions [34]). EU legislative compliance that must be adhered to, as well as national legislation arising from cultural–historical development, includes the Common Agricultural Policy and the Rural Development Programme. The forestry sector’s contribution to GDP in the EU is 0.7% [33], a figure also reflected in the Czech Republic, where it ranges between 0.7% and 0.6%. The share of deciduous and coniferous trees in the CZ is 30% to 70%, the same as in the European Union. The country is also a Schengen member, located in the middle of this space. According to [35], the forest cover of the territory is around 34%. Coniferous trees (67.7%) currently dominate the territory, followed by deciduous trees (30.1%). The total and average stocks of wood in the territory of the state reach 686 million m3 and 263 m3·ha−1 (calculated with clearing areas), respectively. The ownership structure of forests is divided proportionally between state (54%), municipal (17%), and private (29%) forest owners, of which 5.4% are forests owned by religious and church societies. The average GVA between 2013 and 2023 was 0.5% at current prices. Around 13.5 thousand people work stably in the forestry sector in CZ.

The CZ is also described as a country with a medium level of economic development but a high potential for bioeconomy development, with the CZ’s bioeconomy classified as mixed (i.e., encompassing all CZ bioeconomies).

Spatial planning is enshrined in CZ legislation, specifically the Building Act 283/2021 Coll [36]. Spatial planning focuses on the spatial organization of an area, i.e., where and how it can be used. This results in legally binding documents that determine the rules for investors, owners, and public institutions. Strategic and spatial planning should be interconnected; however, in practice, they often operate separately, which reduces the effectiveness of planning. A strategic plan can determine the development direction and motivate progress, but only a spatial plan provides specific spatial options. Without harmonization of both documents, there is a risk of conflicts of interest, project delays, or inefficient use of the area.

The spatial plan classifies areas into distinct types based on their permitted functional use. Forest areas and natural and landscape areas are relevant for forestry [36].

In the CZ, the Ministry for Regional Development has developed a Rural Development Concept [37].

In the CZ, no separate conceptual document has yet been published that addresses the bioeconomy at the national level. The ideas and principles of the bioeconomy have long appeared in a few national strategies across different ministries. The most prominent can be found in the Strategy of the Ministry of Agriculture of the CZ [38]. Another important national conceptual document that reflects the bioeconomy’s ideas is the CZ 2030 Strategic Framework.

Forest bioeconomy in the CZ has been studied, for example, by [39,40]. According to [9,32], there is no commonly agreed-upon definition of forest bioeconomy, and it plays different roles in different EU countries.

The acceptance of bioeconomy principles in strategic documents on a European level was addressed, for example, in [9,40]. At the regional level in the CZ, the application of strategic documents to regional planning [41] was addressed in [42], where no direct bioeconomy strategies were identified in any of the regions examined. However, some strategies that are at least partially related to the bioeconomy were recorded. Based on this, it can be stated that although efforts to incorporate the concept of a bioeconomy have been observed across all regions, developments to support it are still in their initial phase.

3.2. Analyzed Documents of Regional Development in Forestry Concerning Forest Owners

For the content analysis, municipalities and LAGs were selected, the territory of which is managed by one of the significant actors in forestry in the CZ—Archbishop’s Forests and Estates Olomouc (hereinafter referred to as AFEO). The AFEO is a forestry company that manages up to 40,000 hectares of forestland and is one of the largest private landowners in the CZ. The area of forest land represents approximately 1.5% of the area of all forests in the CZ. AFEO is a property that covers forests across 34 municipalities.

Specifically, the following concepts were selected for analysis:

- Supranational and national territorial level:

- ○

- Supranational concepts and conventions on forestry-related topics (sustainable development, environmental protection, and sustainable management of natural resources):

- ▪

- UN Sustainable Development Goals [43];

- ▪

- UN Strategic Plan for Forests 2017–2030 [44];

- ▪

- Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030 [45];

- ▪

- EU Forestry Strategy to 2030 [46];

- ▪

- Framework Convention on the Protection and Sustainable Development of the Carpathians [47].

- ○

- Forestry in basic multi-sectoral national strategies:

- ▪

- Strategic Framework of the Czech Republic 2030 [48];

- ▪

- Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ [49];

- ▪

- Rural Development Concept 2021–2027 [50].

- ○

- Sectoral national strategies on forestry-related topics (sustainable development, environmental protection, and sustainable management of natural resources):

- ▪

- State Environmental Policy of the Czech Republic 2030 with a view to 2050 [51];

- ▪

- Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change in the Conditions of the Czech Republic [52];

- ▪

- State Nature and Landscape Protection Program of the Czech Republic for the Period 2020–2025 [53];

- ▪

- Biodiversity Protection Strategy of the Czech Republic 2016–2025 [54];

- ▪

- Concept for Protection against the Consequences of Drought for the Territory of the Czech Republic [55].

- ○

- Forestry in sectoral national strategies:

- ▪

- Concept of the State Forestry Policy until 2035 [56];

- ▪

- Strategy of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic with a view to 2030 [38];

- ▪

- Strategy for the Development of the Czech Forest State Enterprise, state company [57].

- Territorial level of municipalities and local action groups:

- ○

- Forestry in the strategies of municipalities whose territories are managed by AFEO:

- ▪

- There are 70 municipalities in total, but only 34 of them have local plans (the rest (36) have no local plans related to this study).

- ○

- Forestry in the strategies of LAGs whose territory is managed by AFEO:

- ▪

- A total of 17 LAGs were considered in the analysis. This represents all action groups that cover the given municipalities (LAGs usually bring together several municipalities).

In total, 16 strategic documents at the national and supranational levels, 34 local plans from municipalities, and 17 LAGs’ strategies were analyzed, for a total of 67 documents.

All these documents are publicly accessible (a) on the webpage portals of the relevant ministries (Ministry of the Environment of the CZ: https://mzp.gov.cz/cz accessed on 13 November 2025; Ministry of Agriculture of the CZ: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/en accessed on 13 November 2025; Ministry of Regional Development of the CZ: https://mmr.gov.cz/en/homepage accessed on 13 November 2025) and (b) on the official boards of specific municipalities managed by municipalities with extended activity of the II or III level (link in the delegated activities of local government between regional authorities and other municipal authorities, NUTS4 [41]) and fall within the Olomouc (https://www.olkraj.cz/olomouc-region-official-website accessed on 13 November 2025), Zlín (https://zlinskykraj.cz/ accessed on 13 November 2025), and Moravian-Silesian regions (https://www.msk.cz/index-en.html accessed on 1 December 2025).

In addition to these analyzed documents, it is necessary to consider existing legislation, which is the result of previously enacted documents. Legislation directly influences the feasibility of implementing policies, plans, and strategies.

The whole visualization of this process, as understood for this study, is shown in Figure 1. Arrows show the influences and processes that shape different perspectives; here, we observed connections, functions, and impacts.

The content analysis of the conceptual documents was based on a search for the keywords “forest”, “forestry”, “forest management”, and “forest ecosystem”. If these words were found, the context in which these words were used was analyzed, and the specific topic in connection with forestry that is addressed in the document was noted. Keywords were searched in both the analytical and draft sections of the documents, with the analysis focusing primarily on the draft sections, where greater thematic variability was identified.

This was performed manually. The documents were read and compared. That is, if a given word was found, the context to which it relates was read, and the area of the given issue to which it relates was identified.

The topics were then joined into individual issues and compared at the territorial level. As part of this comparative analysis, the results were visualized using graphic outputs to show the frequency of occurrence of individual topics at different territorial levels. This approach enabled evaluation of differences and similarities in forestry approaches across individual strategies and concepts, thereby achieving the research objectives. From the analyzed documents, the most frequently mentioned thematic categories or topics were identified.

To examine RQ1, “How does this specifically affect the forest bioeconomy and what are its impacts?”, the impact was assessed based on the economic results of forest management.

To assess the impact on the forest bioeconomy, a clear indicator was used: the economic result achieved through the management of 1 ha for a given period (in EUR per 1 ha of forest property; 1 EUR = 25 CZK). To assess whether the application and establishment of concepts and strategies have an impact on the forest bioeconomy, a comparison was made to the economic results of forest owners (without contributions to forest management) and included contributions to forest management for previous programming periods, namely, 2014 to 2020 and 2021 to 2027 (the results for other periods are not known). This result may reflect the impacts of individual legislative changes, stemming from local and regional policies and adjustments to various subsidy measures that forest owners can use, which are defined precisely through conventions and strategies.

The economic results of the forest owner were compared (profit per 1 ha of forest over the years). This economic indicator is chosen for illustrative contrast between different types of ownership. At the same time, it is an economic indicator that the forest owner is obliged to publish in its annual report. Economic profit per unit of forest area can be considered an important bioeconomic indicator. It is the ability of the forest owner to work with the forest’s biological potential and soil production, under various influences, in relation to the applied (limiting) legislative and motivational conditions. This refers to planning and strategic documents.

The impact of local and municipal strategies was assessed based on these results. The data on the forest bioeconomy for AFEO, the analyzed forestry company, were primarily drawn from publicly available annual reports, which every economic subject paying taxes in the EU must publish.

Revenue includes revenue from its own production, services, and goods (the analyzed company is a limited liability company and does not own land but manages it under a lease agreement; it also owns a wood-processing facility—a sawmill for cutting wood).

An additional comparison was made based on the economic results for state, municipal, and private forest owners. These data are published annually by the Czech Statistical Office and are freely available here: https://csu.gov.cz/ accessed on 13 November 2025.

Contributions to forest management, from which financial subsidies can be drawn, are presented by regional authorities, the State Agricultural and Intervention Fund, and the Ministry of Agriculture of CZ. The purpose of the subsidies is primarily to finance silviculture activities, protective measures for forest stands, horse riding, forest infrastructure, and technical equipment.

4. Results

4.1. Regional Development in Forestry: Content Analysis of Selected Conceptual Documents

To address RQ1 (“How is forestry included in strategic development plans at the supranational, national, regional, local, and municipal levels?”), we first compared how forestry is mentioned and described in strategic and conceptual documents across all territorial levels.

The analyzed parts of the documents showed significant differences between the different territorial levels of the strategic concepts. At the national and supranational level, forestry is described in detail in all areas from various perspectives, including environmental, economic, and social.

In contrast, in the analyzed parts of municipality and LAG documents, information on forestry is either not available at all, limited to information on the share of forest areas in the total area of the municipality or region, or available in terms of the share of forestry in the local economy (through the presence of economic entities or employees according to their affiliation to CZ-NACE codes [58]). More detailed information on forestry is not available in any LAG strategy and is present in only a third of municipal strategies. Municipal strategies include data on forest conditions, forest resource management, and the adaptation of forestry to current challenges, such as climate change and bark beetle infestations. These documents often describe flora and fauna; the management of municipal forests, including the employment of seasonal workers; and forest protection.

In the draft parts of the strategies analyzed, most mentions of forestry occur in national and supranational strategies, whereas municipalities and local action groups are less likely to mention it. There is no mention of forestry in more than 2/3 of the draft parts of municipal and local action group strategies. In national and supranational strategies, forestry is mentioned. It is observed that the lower the territorial level, the less forestry is addressed. However, suppose the topic of forestry is mentioned in drafted municipal and local action group strategies. In that case, it is at a greater level of detail than in national and supranational concepts, where the topic of forestry is addressed at a more general, declarative level.

More than half of municipal strategies and more than 10% of local action group strategies do not mention forestry in either the analytical or draft parts.

4.2. Impacts of a Forest Bioeconomy on Forest Management

To address RQ2 (“How does this specifically affect the forest bioeconomy and what are its impacts?”), we used economic results from forest management as an indicator of the forest-based bioeconomy and compared the performance of different ownership types and the AFEO company over time.

The results of forest management must be assessed from the perspective of the occurrence of natural disturbances and geopolitical events (in recent years, forests in Central Europe have been affected by the collapse of spruce monocultures, which has caused problems related to wood removal, a large amount of low-quality wood, droughts, and also local flooding). Coronavirus disease (identified in 2019), the measures taken to address it (which generally reduced demand for wood), problems related to labor and production capacity, the war in Ukraine, and other factors have also had geopolitical effects.

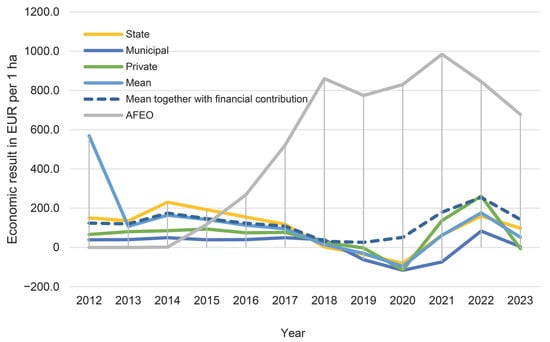

The overall economic management results for state, municipal, and private forests are shown in Figure 2. A comparison of economic results within the framework of financial contributions to forest management is also presented, along with the enterprise’s management results.

Figure 2.

A comparison of economic results for individual types of owners, including financial contributions to forest management, with AFEO results from 2012 to 2023. Source data from [59,60,61,62,63].

The presented results clearly demonstrate that within the framework of financial contributions to forest management, which are a logical consequence of policy measures, there is an effort to economically support owners in times of crisis and to significantly improve economic management. This has had the greatest effect on municipal forests. This is also in agreement with the results of the content analysis; namely, at the local level, the operation of LAGs has one of the greatest impacts on forestry. On the other hand, municipal forests yield the lowest economic returns (without financial contributions). This may be caused by many factors. First, it could be caused by the property’s size and the impossibility of influencing the natural conditions (municipal forests often have small areas) under which they are managed. Naturally, the larger the forest area, the better the management conditions for the forest owner are (economic costs are spread out, natural selection is more diverse, and management can be better structured). In the case of private entities (private forest owners), there is logically a greater emphasis on economic results, whereas in state forests, protected areas and other non-productive forest functions and ecosystem services are supported, for example, through policies.

4.3. Details of Topics in the Analyzed Documents

Building on the overview provided for RQ1, this subsection addresses RQ3 (“How does forestry planning specifically reflect the regional development requirements of these documents?”) by examining which forestry-related topics are emphasized and how they mirror environmental, economic, and social priorities in regional development.

A more detailed analysis revealed several recurring forestry-related concepts. The occurrence of these topics varied across territorial levels. The following topics were noted:

- Sustainable forestry and biodiversity;

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation;

- Water regime in forests;

- Economic competitiveness of forestry;

- Social and non-productive functions of forests;

- Forest maintenance and forest infrastructure;

- Other topics.

4.3.1. Sustainable Forestry and Biodiversity

At the supranational and national levels, the most common topics in draft strategy sections are environmental and biodiversity protection. This theme occurs in all the strategies analyzed. A key priority is to halt deforestation and restore forest ecosystems, which includes ensuring their health and stability. Emphasis is placed on the tree species composition of planted forest stands, which should correspond to habitat conditions (state) and prevent soil degradation. Sustainable forest management, which promotes environmentally friendly and economically viable management methods, is also a frequent theme. Species and landscape diversity are supported, with a preference for more resistant tree species.

National and supranational strategies often include recommendations to reduce management intensity, increase forest species diversity, and leave some wood to decay naturally. Emphasis is also placed on protecting species and minimizing forest fragmentation to ensure healthy biodiversity development. A specific example is selective management methods that support the natural restoration of ecosystems; increasing forest areas and supporting afforestation are also often mentioned.

On the other hand, the topic of environmental protection and biodiversity is less addressed in municipalities’ and LAGs’ strategies. In municipalities, it occurs only in certain parts of strategies, while it is included in less than half of LAG strategies. Nevertheless, in municipalities, this topic is mentioned most often compared to other topics. This is because forestry is generally underrepresented in municipal strategies (see below). In LAGs, it is also one of the most common topics. The content of these topics is very similar to that of supranational and national strategies.

The strategies focus on adjusting forest stands towards a natural structure and tree species composition to strengthen the ecological stability of forests and their resistance to external influences such as climate change and pests. These adjustments include supporting habitat-appropriate tree species that contribute to long-term ecological balance. The strategies also include afforestation, but at the same time, emphasis is placed on the consistent protection of greenery outside the forest. Strategies focus on activities that support biodiversity, such as restoring the species and age structure of forests and the natural regeneration of forest stands, and include sustainable forest management and environmentally friendly practices. The strategies also mention the development of small businesses or small-scale agriculture and forestry with an emphasis on organic operations.

4.3.2. Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation

The second most common topic at the national and supranational strategies is climate change and its mitigation through forests and forest management. The topic is included in more than half of the analyzed strategies.

The priority strategies for this topic are the restoration and protection of forests, which are important for carbon sequestration, reducing floodplain risks, and supporting drought resistance. Adaptation of forests to the extreme manifestations of climate change, such as bark beetle disasters or long-term drought, is also important. The strategies also focus on strengthening forests’ role as renewable energy sources and ensuring their ecological stability amid changing climate conditions.

The topic of climate change is mentioned only within broader municipal strategies, yet it is the most frequently mentioned, alongside sustainable forestry and biodiversity. In the case of LAGs, the topic is mentioned only in strategies. The content of the strategies is very similar to that at the national and supranational levels, but these documents are more detailed.

The strategies focus on supporting adaptation to climate change, risk prevention, and increasing resilience to natural disasters, including rain-related events, windstorms, and forest fires, with an emphasis on sustainable landscape management. Specifically, the strategies include assessing the condition of forest stands, especially in the context of bark beetle disasters. The strategies support both investment projects and awareness campaigns to increase landscape resilience, including the creation of watercourses, pools, and infiltration strips. The initiatives also focus on improving the environment through community energy and other climate-friendly solutions.

4.3.3. Water Regime in Forests

Another frequent topic mentioned in national and supranational strategies concerns the water regime in forests, which is included in more than half of the analyzed strategies.

The strategies focus on forests’ role in protecting water resources and maintaining a stable water regime across the landscape. According to the analyzed strategies, forests support the natural infiltration of water into the soil, which helps restore groundwater resources and stabilizes the water regime of the rural landscape. Water retention in forest ecosystems is key to maintaining enough water in the landscape; protecting soil from erosion is also essential.

With one exception, this topic does not appear at all in municipal strategies, while it appears in less than 1/3 of LAG strategies. In contrast to national and transnational strategies, the latter exhibit a higher level of detail.

The strategies focus on implementing measures to retain water in the landscape, especially in forested areas, to support flood protection and improve the water regime. Water regime modifications include channeling water and creating small water features that support natural water retention. These strategies aim to prevent natural events such as floods and to promote long-term stability of the water regime.

4.3.4. Economic Competitiveness of Forestry

The topic of forestry’s economic competitiveness is also present in 1/3 of national and supranational strategies.

The strategies emphasize the economic benefits of forests, which play a significant role in improving living conditions, especially for poor and vulnerable groups. Forestry contributes to the development of the bioeconomy, job creation, and income security for foresters. The bioeconomy concept is very new in these strategies.

The social benefits of forests include the cultural and health functions they provide to society. The economic competitiveness of forestry is strengthened by supporting innovative and SMART solutions in forestry activities. Many authors consider that innovations within the forestry economy support the bioeconomy.

This topic does not appear in municipal strategies. However, it is represented in more than half of LAG strategies, which is significantly more than in national and supranational strategies. One reason for this may be that it is a topic that can be supported by EU financial funds, to which LAGs often adapt their strategies. LAGs are thematically more detailed.

LAGs primarily focus on supporting small- and medium-scale forestry entrepreneurs and on promoting forestry products and their marketing. The emphasis is on modernizing wood-processing and forestry enterprises through innovations and equipment, including machinery, IT technologies, and other necessary tools. Investments in income diversification help rural forestry enterprises to remain competitive and create new job opportunities. At the same time, supporting local wood production and wood processing is key and can be understood as supporting the bioeconomy.

4.3.5. Social and Non-Productive Functions of Forests

The topic of non-productive functions of forests, e.g., recreation and tourism, does not appear in national and supranational strategies, except for the Framework Convention on the Protection and Sustainable Development of the Carpathians [47]. The CZ is one of eight countries that have adopted this convention. Similarly, within the EU, one can find, for example, the Alpine Convention [64], which operates on the same principle and served as the basis for the creation of the Carpathian Convention [47]. This strategy discusses sustainable tourism development and the importance of forests in maintaining cultural heritage and traditional knowledge.

This topic also does not appear in municipal strategies, with one exception addressing local foresters marking tourist routes. On the contrary, in LAG strategies, this is the most frequently represented topic.

LAG strategies focus on supporting non-productive forest functions, in particular, strengthening their recreational and environmental use. This includes the construction of recreational infrastructure, such as bicycle paths, nature trails, rest areas, bridges, information panels, and game elements, to make forest areas more attractive for tourism. Non-productive investments are also mentioned, including measures to ensure visitor safety, such as railings, footbridges, and waste disposal facilities. The activities are intended to improve the use of forests for society.

4.3.6. Forest Maintenance and Forest Infrastructure

A theme exclusive to local and regional strategies is the support for equipment and infrastructure for forest maintenance; this theme does not appear at the national or supranational level. On the other hand, it is a frequent theme in LAG strategies. More than half of LAGs have included the theme in their strategies.

The strategies emphasize the need to invest in modernizing forestry technologies, machinery, and infrastructure to increase forestry efficiency. Investments focus on the acquisition and modernization of forestry machinery, such as tractors and forwarders, and on improving the quality of wood-processing operations. At the same time, emphasis is placed on repairing and expanding forest roads, which are often in poor condition. Modernization also includes buildings and equipment, as well as the optimization of non-productive infrastructure in forests. These measures aim to improve forest conditions and support the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of the sector.

The theme is addressed only by some of the analyzed municipal strategies, which focus on acquiring equipment for forest management, particularly when the municipality owns and manages its own forests.

4.3.7. Other Themes

During the content analysis of the strategies, we primarily focused on the most common concepts. However, all topics related to forestry, including less common ones, were recorded. At the supranational and national territorial levels, these include sustainable production and consumption of forest products such as wood, and the importance of strengthening capacities and financial resources for sustainable forest management. The involvement of local communities, the private sector, and other stakeholders is also mentioned, as is the need for international cooperation in forest protection. There are also references to the use of renewable energy sources and support for innovation, for example, in the field of modern wooden buildings and agroforestry. There is also a need to support forestry research and innovation, as well as to implement measures to address the excessive population of ungulates.

In municipal strategies, other topics only appear in some cases. There were references to innovations in forestry and to strengthening residents’ identity through local forests. Other topics appear only in some cases for LAGs as well. Specifically, the strategies identified the need for cooperation between the public sphere and forestry entrepreneurs, as well as for educational events for workers and the wider public.

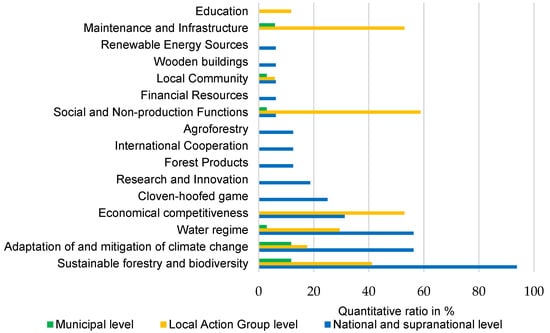

To provide an overall summary of the prevalence of individual forestry topics in the analyzed documents, we present a quantitative comparison in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The quantitative ratio (in %) of individual forestry topics across the analyzed documents at different levels.

If we look at the individual levels, we can determine the frequency of these topics in strategies at those levels. Points are marked in the following intervals according to the percentage of occurrence: ••• = occurred in 51–100% of analyzed strategies; •• = occurred in 26–50% of analyzed strategies; • = occurred in 1–25% of analyzed strategies. The comparison results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The frequency of topic representation in strategies across individual territorial levels.

5. Discussion

In the present study, the topics that pose the greatest challenges for forestry and its contribution to the socio-economic development of the territory, as identified in the selected strategic documents, are examined. These topics are often emphasized in strategic documents as key to solving the socio-economic problems associated with rural development. The available literature covers a variety of topics that can be addressed through forestry.

The topic of research question RQ2: “How does this specifically affect the forest bioeconomy and what are its impacts?” is discussed by a number of scholarly sources.

Forestry is a key pillar of the bioeconomy, as defined by the authors of [65] as “the sustainable production of renewable bioresources and their processing into food, feed, industrial goods and bioenergy.” According to their research, forestry within the bioeconomy significantly contributes to sustainable development. This importance can be demonstrated, for example, by the share of forestry in total GDP, as determined in [66]. In 2019, forestry accounted for 1.21% of total GDP in the CZ [60], above the European average. In the report [66], based on 2015 data, it was found, for example, that, in Finland, forestry and related sectors accounted for EU 513 million of the total bioeconomy, and in 2023, the income was EU 3747 million [67]. Next, agriculture, fisheries, and forestry are also very important for rural livelihoods and generate about 476,260 jobs in the EU, which work in the forestry and logging sector [33].

The importance of forestry for the development of the bioeconomy in Nordic countries is emphasized in [68]. This importance is especially noted in supporting employment and regional innovation. The use of forest biomass for energy purposes plays a crucial role in these countries, particularly its potential to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Forestry thus offers significant potential as a driver of environmentally friendly and socially sensitive economic growth, especially in rural areas. The authors of [6] also note that forestry, as part of the bioeconomy, supports regional development mainly through the sustainable use of forest resources. Employment plays a key role, especially in rural areas where forests are predominantly located.

The authors of [28] confirm these findings and add that forestry has a positive impact on job creation, ecosystem services, and supporting local economies.

In [23], a socio-economic assessment of the impacts of forestry on rural development, specifically at a regional level in the United Kingdom, is presented. The author emphasizes the importance of forestry in generating economic activity through logging and employment in the forestry sector. This study shows that forests and forest landscapes positively influence other sectors of the economy, such as tourism and recreation. In some cases, these effects can even have a more significant role in regions than the economic impacts of logging itself. Although these impacts do not have a direct economic impact, they significantly improve residents’ quality of life.

Similar conclusions are drawn in the study in [6], which demonstrates the positive impact of forestry on socio-economic development using the example of Greece. Forestry in this context contributes both direct and indirect effects. The direct effects include employment and income from wood sales, while the indirect effects focus on biodiversity protection and climate change prevention. Forests are also popular places for outdoor activities and tourism due to their esthetic benefits and recreational opportunities.

The importance of forest ecosystems, not only as a source of wood but for other products as well, is also described in [7]. According to the authors, forest ecosystems protect the landscape from erosion, regulate water flows, and support tourism.

Forestry is analyzed using examples from Croatia, Latvia, Poland, and Romania [69], and from Finland, France, Italy, and Lithuania [70]. The main challenges in these countries include increasing the volume of raw wood materials, improving species composition to increase productivity, and introducing efficient mechanized operations for pre-production clearing and innovative forest management.

The research question RQ3, “How does forestry planning specifically reflect the regional development requirements of these documents?”, is also extensively discussed in the literature.

According to the study presented in [71], the main topics solved by strategies from the point of view of forests and role of them in bioeconomy are sustainable development, biomass accessibility, forest biodiversity, climate change, social values and benefits of forests, efficiency of forests, competitiveness of forest sector, forests and employment, forest owners, role of forests products and involvements of the key actors form the forests sector to bioeconomy.

Other factors that contribute to the development of forestry were identified in [10]. These include government plans and local policies, investment in research and development, the quality of education and talent development, and the business environment.

Using the CZ as an example, [69] highlighted that the importance of forestry for job opportunities is particularly evident in border areas. In addition to its direct contributions, this sector supports the development of other areas, such as tourism, recreation, and services. Forestry, therefore, plays a significant role in strengthening rural areas’ overall social capital.

The results of an analysis of the forest bioeconomy according to [9] can be used by relevant stakeholders in countries to develop a new business plan or promote their current business activities, for example. By implementing the bioeconomy strategy, the local rural economy, particularly in the forest-based sector, can also be promoted. The FAO [72] also attempted to mitigate climate change by providing forest biomass for bioenergy.

There is currently no strategy in the CZ to support the forest bioeconomy in the coming years. Currently, the so-called Platform for Forest Bioeconomy [73] is being established as a team to promote the forest bioeconomy [74]. The team’s aims, among other things, are to integrate policies addressing certain aspects of the circular bioeconomy into a comprehensive strategic document in the CZ and to develop an integrated system of policy instruments that minimizes government spending on introducing the bioeconomy and maximizes bioeconomy production. The first step for policy integration should be a comparison of the functions of strategic and conceptual documents within the framework of regional development, as presented in this study.

They [75] mentioned that regional planning is a contested arena of strategic planning. They approach the complexity of regional planning from three perspectives: interests, institutions, and relationships. Let us keep in mind that sustainable forestry, with an emphasis on deepening results that impact the overall development of the bioeconomy, is anchored in strategies developed at various levels. This is therefore of significant interest. Based on the results we have achieved, when these interests are very little reflected in practical implementation, i.e., at the lowest level. Certain gaps can then be seen in the area of relationships and institutions. Suppose we focus on relationships, as [75] suggests. In that case, the perspective of ‘relations’ uncovers the complex constellations of actors and processes associated with planning, involving various administrative scales, territorial entities, and sectoral policies.

The forestry area is a sectoral policy. It is included under the agriculture area and is primarily under this ministry in most EU countries. At the same time, regional planning is included in the Ministry of Regional Development. Does this mean that there are gaps in the insufficient connection between regional planning institutions and sectoral policies, especially forestry? Then, there is the institutional area, which raises the question of whether there is sufficient institutional connection or emphasis on implementing strategic plans and policies through specific institutions into given sectoral policies, i.e., how much institutional connection is ensured in forestry and regional development. The most important instrument seems to be the regional strategy forest plan.

Within the theoretical framework, we include the regional strategy forest plan in the process, assuming that these plans process interests at the national and supranational levels, including legislative requirements, and that they should serve as the basis for processing forest management plans and municipal territorial plans. The question is how much this is implemented in practice. Is there sufficient connection at both the higher and lower levels? Here, we see that it will be necessary to focus on regional strategy forest plans and their verification, both from the position of content and from the position of application. Our assumption of the appropriate use of regional strategy forest plans is presented in Figure 1.

The answer to whether there is sufficient use of the regional strategy forest plans, but also whether there is sufficient processing for the needs of regional planning and development, may also be that these plans are processed for a period of 20 years and are essentially static, rather allowing for a visual form and spatial planning, but no longer so focused on soft implementation goals. Moreover, Yamada [31] also notes this and concludes that influencing the timing and location of individual forestry activities may enable appropriate regional-scale management to achieve sustainable forest management.

It is necessary to strengthen the link between regional strategy forest plans and territorial (municipal) plans, which is currently minimal, especially in the Czech Republic, and to ensure that regional strategy forest plans connect with them, and vice versa. This requires appropriate policy instruments, at least those that are informative and supportive.

So far, there is no EU legislative norm that requires or encourages forestry planning documents to serve as the basis for spatial planning documents. There is no such obligation under EU law in the field of forestry. It turns out that introducing it would be appropriate, especially if we want to support the bioeconomy.

6. Conclusions

Within the framework of the obtained results, RQ1: “How is forestry incorporated into strategic development plans at the supranational, national, regional, local, and municipal levels?” can be answered as follows: It can be concluded that, at the supranational and national level, mainly topics such as sustainable forestry and biodiversity, and the adaptation and mitigation of climate change and the water regime are addressed. Within the framework of LAG strategies, these topics include economic competitiveness, the social and non-productive functions of forests, and maintenance and infrastructure education. At the municipal level, strategies only address a few of the same issues as at the supranational and national levels, as well as social and non-productive functions (especially in the context of recreational activities in forests), local communities, and education. The regional level is covered by LAG strategies. It can therefore be said that the supranational and national levels are primarily directed at solving ecological issues (marginally, then economic issues, such as economic competitiveness). At the same time, the latter also touches on all topics. The regional level is focused on solving economic and marginally social issues.

Our assumption that the lower the territorial level, the greater the importance attached to forestry was not confirmed. The connection is rather the opposite. At the supranational and national levels, forestry is addressed in various contexts far more often than at the municipal and regional levels. However, the level of detail shows the opposite trend—the highest level of detail is not found in municipal strategies, which can be directly linked to management planning documents (forest management plans).

This may mean that issues addressed at the supranational and national levels may have only a limited impact in practical implementation.

In response to RQ2: “How does this specifically affect the forest bioeconomy and what are its impacts?”, it is possible to clarify how the presence or absence of forestry in strategic documents is linked to bioeconomic outcomes, including access to funding, policy support, and implementation efficiency. Using the example of a forestry company, the economic results comparison shows that state forests consistently achieve the best results. This can be understood as the result of the action of individual strategies and documents, especially at the national level (link to state forest owner). The economic contribution of the state through subsidies is particularly significant for municipal forests. For a private forest owner with a sufficiently large forest cover, this may positively affect bioeconomic outcomes; even so, their economic results are significantly better than those of other types of owners, regardless of the presence of a strategic document to support forest bioeconomy. These strategic documents supporting bioeconomic outcomes for small-scale private forest owners can be existential. This should be the subject of further research.

The results related to the question RQ3: “How does forestry planning specifically reflect the regional development requirements of these documents?” indicate that the main topics that are featured in the analyzed strategic documents include the following: water regime, sustainable forestry and biodiversity support, climate change, maintenance infrastructure, social functions, and economic competitiveness. At the local level, they are biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability.

Issues such as rural employment, innovation, labor productivity, and other topics essential to regional development are not adequately addressed, which has a direct impact on the bioeconomy and its support.

Linking policies to direct economic results is a clear indicator of whether they are working. In this study, we consider regional development as a set of activities through which local actors agree to contribute to the region’s development across environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Forestry is therefore very important. It is neglected in some policies at different levels, as shown by the content analysis results.

This study’s novelty, its systematic, cross-level analysis of forestry planning, contributes to the field of regional development by strongly pointing out that planning tools in forestry (forestry plans and especially regional strategy forest plans) are not sufficiently used to implement development strategies defined at supranational and national levels. Similarly, this area is not sufficiently covered in the implementation of territorial plans at the municipal level. This finding should motivate future researchers to address how to better integrate regional development policies (including an emphasis on supporting the bioeconomy) into forestry at the local and municipal levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H. and Z.Š.; methodology, K.H. and Z.Š.; validation, K.H., Z.Š. and O.H.; formal analysis, K.H. and Z.Š.; investigation, K.H. and Z.Š.; resources, K.H. and Z.Š.; data curation, K.H. and Z.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H. and Z.Š.; writing—review and editing, K.H. and Z.Š.; visualization, K.H., Z.Š. and O.H.; supervision, K.H. and Z.Š.; project administration, K.H.; funding acquisition, K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Technological Agency of the Czech Republic, grant number TQ01000532 “Proposal possibilities for sustainable regional development of forestry from the bioeconomy point of view”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank Ernest Weber (Vriedberg) and Gustav Schulze (Nikolsburg) for their support and very valuable advice on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Helms, J.A. (Ed.) Terminology of forest science, technology, practice, and products. In The Dictionary of Forestry; Society of American Foresters: Bethesda, MD, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- van Hensbergen, H.; Shono, K.; Cedergren, J. A Guide to Multiple-Use Forest Management Planning for Small and Medium Forest Enterprises; Forestry Working Paper, No. 39; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A.; Haughton, G.; Maude, A. Developing Locally: An International Comparison of Local and Regional Economic Development; Caroline Wilding 2003; The Policy Press University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2003; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Haughton, G.; Counsell, D. Regions, Spatial Strategies, and Sustainable Development; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Forestry Bioeconomy Contribution on Socio-economic Development: Evidence from Greece. Land 2022, 11, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; Vizzarri, M.; Lasserre, B.; Sallustio, L.; Tavone, A. Natural capital and bioeconomy: Challenges and opportunities for forestry. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2014, 38, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; D’amato, D.; Stern, T. Forest-based circular bioeconomy: Matching sustainability challenges and novel business opportunities. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwestri, R.C.; Hájek, M.; Šodková, M.; Sane, M.; Kašpar, J. Bioeconomy in the National Forest Strategy: A Comparison Study in Germany and the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barañano, L.; Unamunzaga, O.; Garbisu, N.; Briers, S.; Orfanidou, T.; Schmid, B.; Martínez de Arano, I.; Araujo, A.; Garbisu, C. Assessment of the Development of Forest-Based Bioeconomy in European Regions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, R.; Palátová, P.; Kalábová, M.; Jarský, V. Forest Bioeconomy from the Perspectives of Different EU Countries and Its Potential for Measuring Sustainability. Forests 2023, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J.; Grant, B. Subsidiarity: More than a principle of decentralization—A view from local government. Publius J. Fed. 2017, 47, 522–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Coenen, L.; Morgan, K. Directionality and subsidiarity: Sustainability challenges in regional development policy. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2492171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandan Nambiar Ao, E.K. Forestry for rural development, poverty reduction and climate change mitigation: We can help more with wood. Aust. For. 2015, 78, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykkyläinen, M.; Hyttinen, P.; Mononem, A. Theories on regional development and their relevance to the forest sector. Silva Fenn. 1997, 31, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, S.E. The role of the forest resources in the socio-economic development of the rural areas. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1578–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to Be Drawn Up by Member States Under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Regulations (EU) No 1305/2013 and (EU) No 1307/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2115/oj/eng (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Nowak, M.; Pantyley, V.; Blaszke, M.; Fakeyeva, L.; Lozynskyy, R.; Petrisor, A.-I. Spatial Planning at the National Level: Comparison of Legal and Strategic Instruments in a Case Study of Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. Land 2023, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersperger, A.M.; Grădinaru, S.; Oliveira, E.; Pagliarin, S.; Palka, G. Understanding strategic spatial planning to effectively guide development of urban regions. Cities 2019, 94, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.B.; Kienast, F.; Hersperger, A.M. The compliance of land-use planning with strategic spatial planning–insights from Zurich, Switzerland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 1231–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Půček, M. Strategické Versus Územní Plánování. Online. Urbanismus a Územní Rozvoj, 2009, roč. 12, č. 1–2, s. 3–7. Available online: https://www.uur.cz/media/3i4pwfpt/02_strategicke.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- The Parliament of the Czech Republic. Act No. 248/2000 Coll. on the Support of Regional Development Describes the Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic; Parliament of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Slee, B. The socio-economic evaluation of the impact of forestry on rural development: A regional level analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubeczko, K.; Rametsteiner, E.; Weiss, G. The role of sectoral and regional innovation systems in supporting innovations in forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Letizia, G.; De Lucia, C.; Pazienza, P.; Cappelletti, G.M. Forest bioeconomy at regional scale: A systematic literature review and future policy perspectives. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 155, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Detten, R. Sustainability as a guideline for strategic planning? The problem of long-term forest management in the face of uncertainty. Eur. J. For. Res. 2011, 130, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Forestry Institute. Bioregions Facility 5 Years in Review 2020–2025: Activities and Impact. 2025. p. 27. Available online: https://bioregions.efi.int/bioregions-facility-5-years-in-review-2020-2025-activities-and-impact/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Imbrenda, V.; Coluzzi, R.; Mariani, F.; Nosova, B.; Cudlinova, E.; Salvia, R.; Quaranta, G.; Salvati, L.; Lanfredi, M. Working in (Slow) Progress: Socio-Environmental and Economic Dynamics in the Forestry Sector and the Contribution to Sustainable Development in Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, M.; Cecilia Alonso, C. FDI for forestry: An impact evaluation of regional development. Rev. Reg. Res. Gesellschaft für 2024, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe. The Role of National Forest Programmes in the Pan-European Context. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Role on National Forest Programmes in Europe, Vienna, Austria, 14–16 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Y. Can a regional-level forest management policy achieve sustainable forest management? For. Policy Econ. 2018, 90, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvig, A.; Zivojinovic, I.; Hujala, T. Social Innovation as a Prospect for the Forest Bioeconomy: Selected Examples from Europe. Forests 2019, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustafor. Forests, Forestry and Logging. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Forests,_forestry_and_logging#Forest_areas_in_the_EU_are_expanding (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- European Environmental Agency. Biogeographical Regions in Europe. 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/biogeographical-regions-in-europe-2 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic. Report on the State of Forests and Forest Management 2023. 2025. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/publikace/zprava-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho-hospodarstvi-cr/zprava-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho-hospodarstvi-2023 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Czech Republic. Act No. 283/2021 Coll., Building Act. In: Collection of Laws of the Czech Republic [Online]. 2021. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2021-283 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ministry of Regional Development of the Czech Republic. Rural Development Concept. 2019; p. 216. Available online: https://mmr.gov.cz/cs/ministerstvo/regionalni-rozvoj/regionalni-politika/koncepce-a-strategie/koncepce-rozvoje-venkova (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic. Strategy of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic with a View to 2030. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/ministerstvo-zemedelstvi/koncepce-a-strategie/strategie-resortu-ministerstva-1 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Palátová, P.; Purwestri, R.; Marcinekova, L. Forest bioeconomy in three European countries: Finland, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. Int. For. Rev. 2022, 24, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, L.; Giertliová, B.; Hajdúchová, I.; Šálka, J. Acceptance of bioeconomy principles in strategic documents on European and Slovak level. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 92, 02044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europena Commision. Commission Regulation (EC) No 105/2007 of 1 February 2007 amending the annexes to Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Establishment of a Common Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS). 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007R0105 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Volrábová, K. Bioekonomika z Pohledu Regionů v České Republice. Bachelor’s Thesis, Czech University of Life Science, Praha, Czech Republic, 2024. Available online: https://theses.cz/id/u6xl4z/53045404 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly; Seventieth Session; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]