Abstract

Terrestrial carbon stocks have a substantial effect on the global carbon balance and promoting regional sustainable development. In the midst of growing urbanisation, the Chengdu metropolitan area—a key development pole in western China—has seen a radical reworking of its Production–Living–Ecology (PLE) functional framework. This transition has had a significant impact on the spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon stocks, but the fundamental mechanisms have yet to be comprehensively understood. To address this, this study constructed a GMOP-PLUS-InVEST-GWR coupled model to simulate and analyze the spatiotemporal evolution relationship between PLE functions and carbon stocks under multiple scenarios from 2000 to 2035. Results indicate that the evolution of the PLE functions reveals a trend of enhanced living functions, diminished production functions, and a slight increase in ecological functions. This has resulted in an overall decrease in carbon storage of 1199.63 × 104 t. Simulations indicate that the Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS) represents the optimal pathway for achieving stable carbon sinks and sustainable system development. It maximizes ecological quality improvement (total increase of +454.74 km2 across Zone 5) while minimizing carbon loss (−418.38 × 104 t). Conversely, the Economic Development Scenario (EDS) would result in the greatest carbon loss (−613.18 × 104 t). The impact of PLE functions on carbon stocks exhibits spatial heterogeneity: residential functions show negative effects (coefficients: −1.16 to −2.30), ecological functions yield positive effects (coefficients: 0.87 to 1.65), while the influence of production functions gradually shifts toward enhancing carbon sinks, with positively correlated areas increasing to 81.15%. This study provides scientific basis and spatial decision support for coordinating land development and conservation in rapidly urbanizing regions and enhancing regional carbon sink functions.

1. Introduction

Terrestrial ecosystems are essential to the global carbon cycle, sequestering carbon dioxide through photosynthesis [1,2]. Their carbon storage dynamics are notably affected by changes in land use [3,4,5]. The structure and balance of production–living–ecological (PLE) functions within national territorial spaces serve as the foundation for sustaining ecosystem services, including carbon sink functions [6,7]. The concept of the PLE functions in China closely aligns with the core principles of “Land Use Multifunctionality” that are extensively examined in international academic discourse. This concept has been extensively examined in regions like Europe [8,9], offering a common theoretical basis for comparative research. China’s swift urbanization and industrialization are reshaping its territorial space, disturbing the balance among PLE functions and presenting significant challenges to the carbon storage capacity of terrestrial ecosystems [10,11]. In this context, China’s introduction of “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality” goals [12] has raised territorial spatial planning to a national strategic priority, aiming primarily for low-carbon development via optimized spatial allocation and functional regulation [13]. Consequently, understanding the fundamental mechanisms through which PLE spatial evolution affects carbon storage has emerged as a significant scientific inquiry requiring immediate investigation.

Research on the PLE functions of territorial space and ecosystem services corresponds with the prevailing international paradigm of land use simulation and ecological effect assessment. The InVEST model, developed at Stanford University, serves as a fundamental instrument for the assessment of global ecosystem services. The integration approach utilizing the PLUS model aligns with international standards by combining InVEST with models like CLUE-s and CA-Markov. Recent research, including Liu et al. conducted in Inner Mongolia, has integrated PLUS, InVEST, and Bayesian networks to identify ecologically significant zones, thereby broadening the application of this framework [14]. Luo et al. integrated InVEST with Bayesian networks to investigate the mechanisms underlying the evolution of ecosystem service trade-off intensity in the South Four Lakes basin [15]. In the Chinese context, He et al. [16], Wang et al. [17], and Chen et al. [18,19] have effectively utilized the PLUS-InVEST model chain to forecast carbon stocks in the Yellow River Basin and Hubei Province, as well as to assess ecosystem services in Haikou City. The studies collectively confirm the effectiveness and applicability of this integrated approach in domestic research. The PLUS model excels at simulating detailed land use changes across multiple scenarios, providing a dynamic foundation for analyzing the PLE spatial patterns. The InVEST model effectively quantifies key ecosystem services such as carbon storage, serving as a core metric for evaluating ecological functions. The integrated application of these two models makes this research methodology particularly suitable for evaluating the ecological impacts of land use transformation. It directly supports the systematic identification of PLE functions, future projections, and the analysis of inherent trade-offs, thereby providing scientific basis for regional spatial planning and ecological conservation.

Nonetheless, conventional research methodologies are fundamentally limited by a “land-centric perspective.” This approach attains high spatial precision by classifying PLE functions according to land use types and projecting their future distribution; however, it fails to account for the coexistence, competition, and synergistic interactions among PLE functions in real territorial contexts. The statement also reduces the intricate relationships between PLE functions and ecosystem services [20]. In the context of carbon stock research, current studies reveal two significant limitations: Most investigations primarily concentrate on carbon emissions at the site level or conduct carbon balance analyses [21,22], while giving insufficient attention to carbon stocks as a vital variable in carbon sinks. Secondly, at the level of research entities, simulation methods focused on land use conversion face challenges in clarifying the bidirectional feedback mechanisms between PLE functions and carbon storage capacity.

This study proposes a transition from static “land cover” management to a dynamic “functional flow” regulation perspective to address these limitations. This approach acknowledges that the relationship between carbon stocks and PLE functions is contingent not only on land type but is also significantly affected by attributes of functional intensity.

This study develops an integrated model framework (GMOP-PLUS-InVEST-GWR) to systematically address the identified challenge. We present a grey multi-objective optimization model (GMOP) to establish future land demand, addressing the limitations of conventional scenario simulations that depend on extrapolating historical trends. This method more effectively aligns scenarios with the intricate system requirements of sustainable development [23,24]. The PLUS model subsequently simulates the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of PLE areas through 2035, based on the optimized demand. The InVEST model is utilized to quantitatively evaluate the spatiotemporal variation of carbon stocks across various scenarios. The geographically weighted regression (GWR) model is employed to analyze the spatial non-stationary relationship between PLE functions and carbon stocks, elucidating their local driving mechanisms. This study uses the Chengdu Metropolitan Area as a case study and applies a “function-space-response” analytical framework to clarify the spatial driving mechanisms of PLE functional evolution on carbon stocks within the context of multi-objective optimization. This establishes a scientific foundation for enhancing territorial spatial planning to achieve carbon neutrality objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

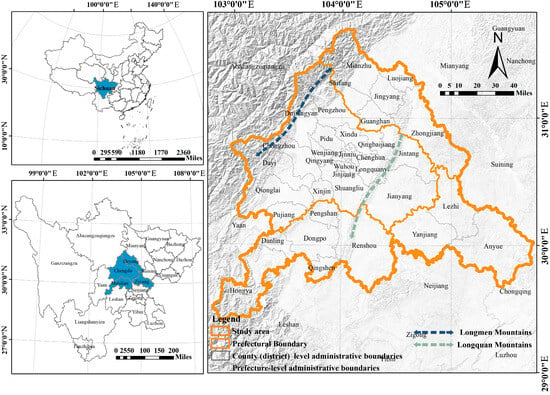

The Chengdu Metropolitan Area (102°49′–105°27′ E, 29°15′–31°42′ N), located in the western Sichuan Basin, features a topography characterised by “one-fifth mountainous terrain, one-fourth flat plains, and one-fourth hilly areas.” The study area averages 1102.84 mm of precipitation annually (Figure 1). The region falls within the subtropical humid monsoon climate zone and encompasses four distinct administrative units: Chengdu City, Deyang City, Meishan City, and Ziyang City. As set out in the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Territorial Spatial Plan (2021–2035) [25], the region’s total planned area is 33,100 square kilometres, with the long-term planning target year set for 2035.

Figure 1.

Schematic map of the study area.

This study investigates the optimization of Production–Living–Ecological (PLE) functions as a driver of low-carbon territorial development. PLE configuration systemically influences carbon stocks by governing land use: optimized production cuts emissions, enhanced ecology boosts sinks, and intensified living spaces reduce footprints. Therefore, research on the spatiotemporal evolution of PLE functions and their carbon stock response is crucial to advance the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Territorial Space Planning and to support regional green, low-carbon development and modernised territorial governance.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

As shown in Table 1, the data types employed in this study include basic, natural environment, socioeconomic, and transportation location data. The land use data were reclassified into nine categories based on the Chinese Academy of Sciences land classification system standards and relevant literature, land use data are available for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 [22,26,27,28]. These categories are as follows: agricultural production space, industrial and mining production space, urban living space, rural living space, grassland ecological space, forest ecological space, river and lake ecological space, other water ecological space, and other ecological space (Table 2). All data were standardized to a 30-metre spatial resolution and projected into the WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_48N coordinate system [29].

Table 1.

Data Types and Sources.

Table 2.

Assessment of the PLE Functions of Land Use Types.

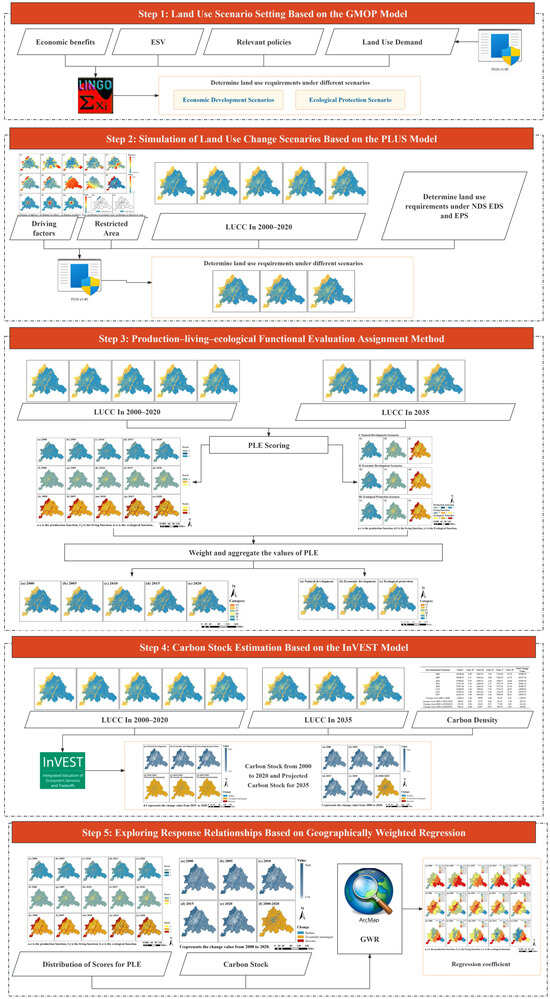

The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 2. The core process comprised five sequential steps: establishment of land use scenarios, simulation of change, evaluation of PLE functions, estimation of carbon stocks, and exploration of response relationships.

Figure 2.

Research flowchart.

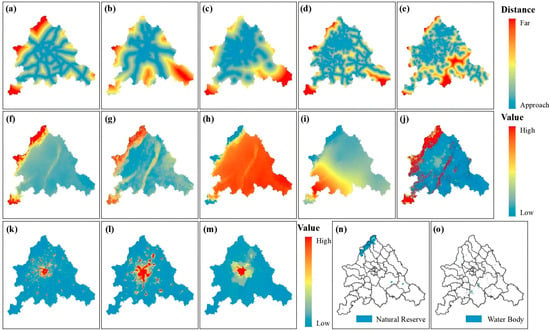

First, with the objective of achieving “maximisation of economic value” and “ecosystem service value” (ESV) functions were constructed on the basis of prior research. These functions, in conjunction with the constraints derived from policies and linear projections, were entered into the Lingo 18.0 model for calculation. This generated land demand results, completed the initial setting of land use scenarios, and provided inputs for subsequent PLUS model operations. Second, LUCC data from the two periods were entered into the “Extract and expansion” module to generate expansion maps. These factors were then combined with the driving factors and restricted areas (Figure 3) and entered into the LERS module. This process was undertaken to validate the model and produce land development potential maps. The land demand outputs from the GMOP model, development potential maps, and 2020 LUCC data were then entered into the CARS module to simulate LUCC outcomes for 2035 under the three scenarios. Third, informed by the LUCC data from 2000 to 2020 and the 2035 LUCC data from the three scenarios in Step 2, PLE functions scoring will be conducted. Following the weighted aggregation of the scoring results, a PLE functions classification map is generated to complete the PLE functions evaluation. Fourth, the LUCC data from 2000 to 2020, the projected LUCC data for 2035, and the carbon density data were entered into the “Carbon Storage and Sequestration” module using the InVEST model. This was done to obtain the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of carbon stocks. Consequently, a spatial characteristic analysis was conducted based on the PLE functions distribution from Step 3 and the carbon stocks distribution from Step 4. Step 5 is analysis of response relationships. Global Moran’s I was used to confirm the spatial clustering of carbon stocks, followed by a Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) to quantify and visualize the local relationship between PLE functions and carbon stocks.

Figure 3.

The driving factors and restricted areas. (a) Distance to highway; (b) Distance to railway; (c) Distance to primary road; (d) Distance to Secondary road; (e) Distance to third-level road; (f) Elevation; (g) Slope; (h) Temperature; (i) Precipitation; (j) Soil; (k) Population density; (l) Nighttime lighting; (m) GDP; (n) Nature Reserve; (o) Water body; ((a–m) is the Driving factors, (n,o) is the limiting factors).

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. PLE Functions Evaluation Weighting Method

The delineation of PLE functions spaces is predicated on the intrinsic relationship between PLE functions and the dominant land use function. This study draws on extant research [22,26,27,28] in order to determine the dominant function of land through land use types and to construct a comprehensive PLE functions evaluation system. In consideration of the particular characteristics of the Chengdu Metropolitan Area, PLE function values were allocated to diverse land categories (Table 2).

The regional characteristics of the study were used to calculate a weighted summation of production, living, and ecological functions values, employing a weighting ratio of 1:1:0.5 [22,26,27,28]. This comprehensive PLE functions value was then used to categorize the study area into six dominant functional types (Table 3).

Table 3.

The PLE Functional Zone Classification.

2.3.2. Land Use Change Scenario Simulation Based on the PLUS Model

- Construction of the PLUS Model;

The PLUS model is an advanced patch-based land use change simulation model. The model combines the Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) and a cellular automata model with multi-type random patch seeds (CARS) [30]. This integrated approach simulates the patch-level evolution of land use types and optimizes the discovery of conversion rules and landscape dynamics.

- Scenario Setting;

The year 2035 has been established as the long-term objective for the territorial spatial planning of the Chengdu Metropolitan Area. The carbon sequestration capacity of high-intensity carbon sink functional zones may reach its zenith during this period, requiring an evaluation of the efficacy of policy implementation. This study analyzes two scenarios for the pivotal milestone year of 2035 to identify sustainable pathways that synchronize economic, ecological, and urban development. Two scenarios were developed based on the baseline Natural Development Scenario (NDS): an Economic Development Scenario (EDS) and an Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS).

- Parameter Setting;

Neighborhood weights reflect the benefit of a particular land use type in either spreading into adjacent areas or preventing encroachment from other types, influenced by neighborhood effects. The expansion intensity of each land use type is determined using historical land use data, with modifications made in accordance with pertinent literature and actual circumstances, as shown in Reference [31]. Table 4 displays the results of neighborhood weights. The precise calculating formula is detailed below:

Table 4.

Neighborhood Weight Magnitude.

In the equation: represents the standardized deviation value, X denotes the change in area across land categories between two periods of land use data, is the maximum value of all land category area changes, and is the minimum value of all land category area changes.

The conversion matrix delineates changes in land use among various land categories. The conversion matrix parameters for various growth scenarios were established based on land conversion trends and the integration of pertinent studies [32,33,34] alongside regulations relevant to the study area (Table 5).

Table 5.

Conversion Matrix Settings.

- Accuracy Verification;

This research employed 2010 land use data to model land use patterns for the year 2020. The validation outcomes reveal a Kappa coefficient of 0.80 and a total accuracy of 0.90. The results indicate a high degree of simulation accuracy, making the model appropriate for forecasting future land use changes in the studied area.

2.3.3. Land Use Scenario Setting Based on the GMOP Model

The Gaussian Multi-Objective Programming (GMOP) model constitutes an advanced iteration of conventional Multi-Objective Programming (MOP). The model in question integrates the GM (1, 1) model with gray prediction theory within a multi-objective framework, facilitating a thorough examination of uncertainty in future land use patterns. This model enables accurate forecasting in high-uncertainty situations by utilizing multi-objective programming to balance economic, ecological, and social priorities. Thus, it produces optimum land use pattern solutions that facilitate effective land use management and decision-making in complex areas. This study is based on the integration of relevant documents, such as the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Territorial Spatial Plan (2021–2035) and the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Development Plan, as well as the use of existing literature [18,35,36]. Using this systematic methodology, three land use change scenarios have been formulated, and the quantity of land use type modules adhering to defined restrictions has been determined. This study seeks to provide decision-makers with optimal benchmark solutions for land use optimisation.

- Scenario Design Based on Multi-Objective Programming;

Natural Development Scenario (NDS): This study simulates autonomous land development pathways from 2000 to 2020, using land use data and considering regional socioeconomic and natural conditions, under the assumption that existing trends will continue without major policy or planning interventions.

Economic Development Scenario (EDS): Future development emphasizes economic growth as the principal objective. The objective functions for the GMOP economic benefit have been established, drawing on pertinent studies [37] for their calculation. The economic benefits associated with land categories are assessed through the output values derived from agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries, in addition to the overall output value of secondary and tertiary industries. The economic benefits for alternative ecological spaces are established at zero.

Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS): This scenario is presented for consideration. This scenario examines significant strategic initiatives for developing ecological civilization and safeguarding ecological space. The objective is to model optimized land use trajectories based on the principle of ecological priority. The scenario is informed by policies including the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Territorial Space Planning (2021–2035) [25] and the Chengdu Metropolitan Area Development Plan [38], which underscore the rigorous application of the “three lines” system—ecological red line, permanent basic farmland, and urban development boundary.

This approach aims to optimize the territorial spatial pattern and improve the integrity and stability of ecosystems. An ecological benefit objective functions for GMOP is established, and the derivation of this function is calculated. The calculation method for ESV is based on relevant studies [18,35,36], which assume ESV values of 0 for industrial and mining production areas, urban residential areas, and rural residential areas. The formula is presented below:

In the equation: represents the economic benefit per unit area for land use type i (10,000 yuan/hm2), and represents the ecosystem service value per unit area for land use type i (10,000 yuan/hm2). denotes the area of the i-th land use type, where i = 1 to 9, sequentially representing agricultural production space, industrial and mining production space, urban living space, rural living space, grassland ecological space, forest ecological space, river and lake ecological space, other water ecological space, and other ecological space. This study utilizes historical economic data from 2000 to 2020 to project the economic and ecological benefits that are anticipated to accrue in 2035.

- Constraints;

Enhancing land use patterns within defined restrictions improves conformity with current policies and plans, hence augmenting the practical guidance and policy relevance of the research. This study delineates limits for diverse land uses, grounded in the current literature and pertinent planning documents [25,38,39], focusing on techniques for developing a framework for the protection and development of metropolitan land space (Table 6).

Table 6.

Formulation of Constraints.

2.3.4. Carbon Stocks Estimation Based on the InVEST Model

This study used the Carbon Storage and Sequestration module of the InVEST model to evaluate carbon stocks. The methodology incorporates carbon density parameters from various carbon pools, including aboveground biomass (living aboveground vegetation), belowground biomass (living plant roots), soil organic matter, and dead organic matter (litter and deceased plants) [40]. The model quantifies organic carbon, which is actively influenced by land use decisions; inorganic carbon pools are considered stable and are not included. The parameters are applied to land cover grids to systematically assess carbon stocks throughout the study area.

In the equation: indicates the carbon density of a specific land category. , , and represent the carbon density (t·hm2) of aboveground biomass (living aboveground vegetation), belowground biomass (living plant roots), soil organic matter, and dead organic matter (litter and dead plants), respectively. denotes the area of this land category (hm2), and indicates the total carbon stock.

This study used carbon density data derived from national carbon density research, alongside studies specific to the Yellow River Basin and Southwest China [16,32,41]. The study conducted by Li Kerang [42] and Alam et al. [43] established the basis for utilizing precipitation and temperature–carbon density relationship models to adjust carbon density values for the study area. This process produced carbon density data for the study region (Table 7), thereby improving the reliability and scientific rigor of carbon stock calculations.

Table 7.

Carbon density values for the study area.

The formula for correcting carbon density is presented as follows:

In the equation: The carbon density values were adjusted using climate-based correction factors. In the equations, and represent mean annual precipitation and mean annual temperature, respectively. For the Yellow River Basin, these values are 456 mm and 8.1 °C [41].

The terms , , and denote the corrected carbon densities (Mg/ha) for soil (based on ), and for biomass (based on and ), respectively. The correction coefficients for biomass carbon density with respect to and are denoted as and , while and represent the overall correction coefficient for biomass and the correction coefficient for soil carbon density, respectively. Subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the study area and the national average of China, respectively.

The resulting corrected carbon density values for the study area, derived using the correction formulas, are summarized in Table 7.

2.3.5. Exploring Response Relationships Based on the Geographically Weighted Regression Model

- Global Moran’s I Analysis;

The Global Moran’s I analysis is used to assess the presence of significant spatial autocorrelation in a variable [44]. A global autocorrelation test was conducted to determine if carbon stocks demonstrates significant spatial autocorrelation, with the calculation of Global Moran’s I. The Moran’s I index varies between −1 and 1. A greater absolute value signifies enhanced spatial autocorrelation. A positive Moran’s I index (greater than 0) signifies a positive correlation, whereas an index of 0 denotes the absence of spatial dispersion or clustering. A negative Moran’s I index (less than 0) signifies a negative correlation.

- Geographically Weighted Regression Model;

The geographically weighted regression (GWR) model permits regression coefficients to fluctuate based on spatial location, thereby elucidating local mechanisms of action. This approach offers a precise interpretation of the spatial heterogeneity of driving factors, accurately reflecting regional variations in their heterogeneity, directionality, and intensity [45]. This study examines the PLE functions as independent variables and carbon stocks as the dependent variable, analyzing the spatial differentiation of the effects of these functions on carbon stocks. The formula is presented below:

In the equation: is the carbon stock; is the intercept; is the kth PLE functions for sample i; is the spatial coordinate of i (i = 1, 2, 3…k); is the random disturbance term. The GWR model calibrates a unique set of coefficients for each location i in space. This is achieved using a weighted least squares approach, where each neighboring observation j is assigned a weight w_ij when calibrating the model for location i. This weight is determined by a spatial kernel function (this study employs a Gaussian function), which is a decreasing function of the distance between locations i and j. Consequently, sample points closer to location i exert a greater influence on the estimation of its local coefficients than those farther away. The spatial extent of this influence is controlled by a key parameter—the bandwidth. In this study, the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) was used to optimally determine the bandwidth, ensuring an optimal balance between the goodness-of-fit and model complexity.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Evolution of the PLE Functions

3.1.1. Analysis of the Evolution of the PLE Functions from 2000 to 2020

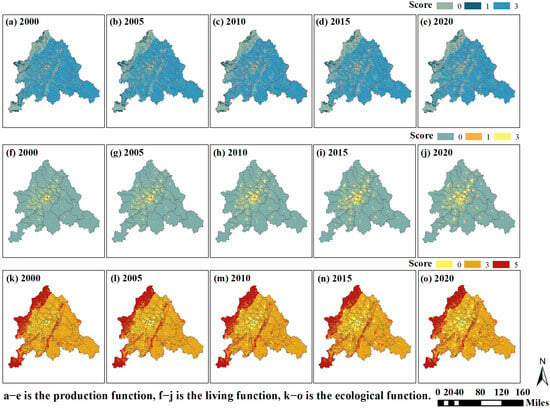

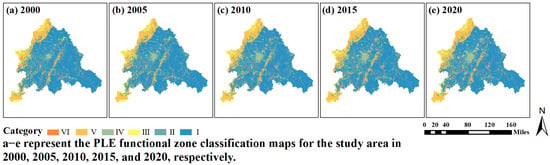

Between 2000 and 2020, the overall productive capacity of the study area experienced a decline, as indicated in Table 8 and Figure 4. Specifically, Zone 3 decreased by 1019.55 km2, while Zone 0 saw an increase of 1082.30 km2. Zone 3 demonstrated a significant spatial distribution, covering a large expanse of the central-eastern plains. Zone 0 displayed a distinct, point-like distribution emanating from urban centers and a linear distribution along the Longmen Mountains to the west. Zone 1 was identified as being intermittently integrated within the western regions of Zone 0. In this timeframe, Zone 0 expanded radially from central areas, increasingly intruding upon the original Zone 3 territory, a trend notably evident between 2000 and 2010. This finding indicates a strong relationship between productive functions and geographical factors, including elevation and proximity to urban centers. Productive functions demonstrated a decrease in the Longmen Mountains, Longquan Mountains, and urban areas. These regions experienced additional expansion alongside urban sprawl.

Table 8.

Area and Change Values of the PLE Functions in the Study Area from 2000 to 2020. (Unit:km2).

Figure 4.

The PLE function map for the study Area, 2000–2020.

From 2000 to 2020, living functions in the study area experienced notable enhancement (Table 8, Figure 4), as indicated by increases of 886.85 km2 and 584.06 km2 in Zones 3 and 1, respectively, whereas Zone 0 saw a reduction of 1470.91 km2. The spatial distribution of high-value residential zones (Zone 3) exhibited a multi-polar pattern, characterized by core clusters located in Chengdu’s five urban districts: Jinjiang, Jinniu, Wuhou, Qingyang, and Chenghua. Zone 3 experienced outward urban expansion characterized by a dotted pattern centered on Chengdu’s urban core, reaching the second ring by 2020 and establishing secondary agglomeration centers in areas such as Jingyang, Dujiangyan, Dongpo, and Yanjiang. Since 2010, Zone 1 has progressively developed and established agglomeration points, dependent on Zone 3, while Zone 0 continues to face encroachment. The spatial arrangement of residential functions aligns closely with patterns of urban growth. The enhancement of these functions is directly linked to urbanization, population density, and economic growth.

From 2000 to 2020, the study area’s ecological functions exhibited an overall trend of reduced coverage but improved quality (Table 8, Figure 4). Specifically, the area classified as Zone 5 increased by 83.47 km2, while Zone 0 expanded by 1470.91 km2. In terms of their spatial distribution, high-value ecological functions zones are primarily located in belts along the Longmen and Longquan mountain ranges, with sporadic points of occurrence in the plains. Zone 0 is characterised by its concentration in urban built-up areas, reflecting its weaker ecological functions. Zone 0 underwent continuous expansion and encroachment upon Zone 3 from 2000 to 2010, after which it decelerated and stabilised. From 2010 to 2020, Zone 5 underwent slight expansion in the Pengshan and Pujiang areas. The overall ecological pattern of the entire region remained stable. The Longmen-Qionglai Mountain Range, located in the northwest, and the Longquan Mountain Range, situated in the southeast, are distinguished by their mountainous terrain and favourable climate, which collectively form a robust ecological foundation. The ecological functions of these areas remain consistently high and stable, thus rendering them crucial ecological support zones for the region.

Between 2000 and 2020, the spatial distribution of PLE functions in the study area demonstrated a pattern characterized by a “stable core and interwoven periphery” (Figure 5). The functional living zone extended outward from the central urban core. The production and ecological functional zones displayed a dispersed distribution pattern at the periphery, characterized by strong integrity, with the robust ecological functional zone and the production functional zone forming a belt-like interlaced configuration across the Longmen and Longquan Mountains. Residential zones experienced continuous expansion in spatial evolution, particularly from 2000 to 2010, marked by significant outward growth: the living area in Zone 3 increased by 602.02 km2. In contrast, production and ecological zones underwent persistent compression, over the past 20 years: production in Zone 0 increased by 1082.30 km2, while ecological Zone 0 increased by 1470.91 km2, marked by diminished coverage and significant land use conversion. Robust ecological zones exhibited stability throughout temporal scales. Starting in 2005, production–living functional zones appeared intermittently in residential areas, achieving stabilization post-2015 in locations including Longquanyi, Shuangliu, Xinjin, and Yanjiang. Other functional zones demonstrated minimal changes, thereby preserving overall structural stability. This evolutionary pattern is mainly due to urbanization, population concentration, and economically driven changes in land use. It is also affected by mountainous ecological conditions and agricultural spatial patterns. The formation of a PLE functional system has resulted in notable central–peripheral differences.

Figure 5.

The PLE functional zone classification map for the study area, 2000–2020.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Evolution of the PLE Functions by 2035

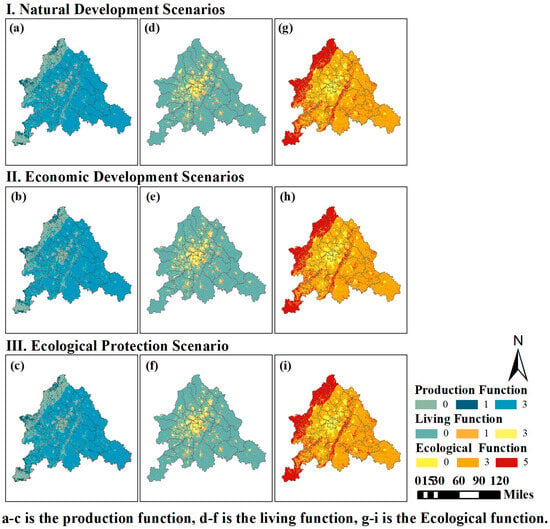

This study used multi-scenario simulations to predict the evolution of the PLE functions in the study area by 2035. The findings demonstrate that functional structures show notable variations across various development scenarios. In the NDS, there is a decline in production and ecological functions, accompanied by an enhancement of living functions. In the EDS, production and living functions are augmented, whereas ecological functions are diminished. The EPS enhances the optimization of ecological functions.

Quantitative analysis (Table 9) indicates that in the natural development scenario, there is a significant reduction in production and ecological functions, with zero-scored zones expanding by 429.64 km2 and 835.38 km2, respectively. In the context of economic development, production functions showed a marginal decline, with Zone 0 experiencing a reduction of only 156.96 km2. The living functions showed a significant improvement, with Zone 0 contracting by 730.91 km2 and Zone 1 expanding by 539.69 km2. In contrast, ecological functions were notably suppressed, with Zone 0 expanding by 730.91 km2. In the ecological priority scenario, Zone 5 demonstrated the most significant improvement in ecological functions quality, with an increase of 454.74 km2, whereas Zone 0 faced the largest decrease of 679.34 km2. Nonetheless, the productive functions encountered considerable limitations, as Zone 0 expanded by 629.05 km2.

Table 9.

Area values and change values of the PLE functions for the study area in 2035. (Unit:km2).

A spatial feature analysis was conducted to assess the spatial distribution patterns of the study area in 2035 under three development scenarios (Figure 6). The analysis revealed that, while patterns remain largely consistent across scenarios, significant changes are evident when compared to the 2020 data. NDS demonstrates a propensity for production functions to aggregate in central locations, resulting in urban growth that encroaches upon neighboring high-value production areas. Furthermore, there is a recorded expansion of Zone 0 in an outward direction. In the realm of economic development, a notable enhancement in living functions occurred, characterized by the outward expansion of Zone 3 from the center, leading to the creation of larger agglomerations. Evidence suggests that areas such as Jingyang and Guanghan exhibited ongoing development trends in conjunction with the central zone. In contrast, Zone 1 underwent significant expansion marked by a multi-centred, point-like configuration. In the ecological development scenario, Zone 3 exhibited expansion in dispersed clusters around the Longmen and Longquan Mountains, accompanied by a notable enhancement in ecological quality. The decrease in the production functions transpired in a manner analogous to that seen in natural circumstances.

Figure 6.

The PLE function map for the study area in 2035.

By 2035, the functional distribution patterns of the PLE spaces in the study area demonstrate clear spatial evolution characteristics (Figure 7). In conclusion, boundaries between functional land types are increasingly dynamic due to more frequent conversions. The spatial aggregation patterns of Class IV areas transform, demonstrating active interactions and conversions with adjacent Class I and II areas. This trend is minimally evident in the economic development scenario. Simultaneously, Class V regions are experiencing expansion along the Longmen and Longquan mountain ranges, demonstrating a more distinct interlaced distribution with Class III areas, particularly under the economic development scenario.

Figure 7.

The PLE functional zone classification map of the study area in 2035.

3.2. Analysis of Carbon Stocks Evolution

3.2.1. Analysis of Carbon Stocks Evolution from 2000 to 2020

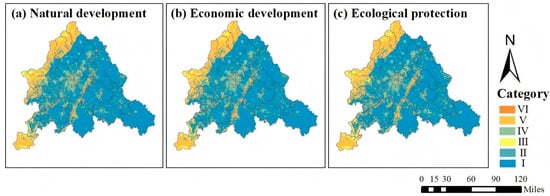

Carbon stocks demonstrated a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2020 (Table 10). Quantitative analysis reveals a decrease of 1199.63 × 104 t, corresponding to a reduction of 4.51%. Analysis of ecological land use categories reveals a decrease in carbon stocks in Class I and Class III areas, while other categories experienced a slight increase. Class I areas underwent a significant decrease of 1250.34 × 104 t, which directly influenced the overall reduction in carbon stocks.

Table 10.

Simulated Carbon Stock and Change Values in the Study Area from 2000 to 2035. (Unit: t).

The spatial characteristics of carbon stocks from 2000 to 2020 demonstrate a central–peripheral differentiation pattern (Figure 8). Areas with low carbon stocks are concentrated in the central zone, whereas the western Longmen Mountains and central Longquan Mountains exhibit higher carbon stocks arranged in a linear pattern.

Figure 8.

Spatial Distribution and Changes in Carbon Stocks from 2000 to 2020.

The research demonstrates notable spatial evolution characteristics in carbon stocks (Figure 8). This results in the expansion of low-value zones within the urban core and the fragmentation of high-value zones in the periphery. The outward radiation of central low-value zones generates new clusters of low-value areas, demonstrating that urbanization persistently encroaches on peripheral ecological land, resulting in a continuous reduction in carbon sink capacity in core and near-core zones. The integrity of high-value zones is compromised, leading to a decline in carbon sink functionality.

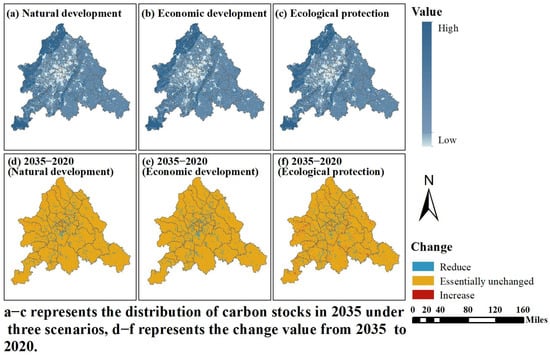

3.2.2. Analysis of Carbon Stocks Evolution by 2035

This research employed multi-scenario simulations to evaluate changes in carbon stocks within the study area by 2035. The results of the study, as presented in Table 10, indicate the following clearly: Carbon stocks demonstrate a decreasing trend across all three scenarios. The Economic Development scenario exhibits the most significant reduction, amounting to 613.18 × 104 t (a 2.47% decline), while the Ecological Conservation scenario shows the least reduction, with a decrease of 418.38 × 104 t (a 1.68% decline). Variations in carbon stocks are primarily determined by Class I and V regions. Class I areas are identified as the primary source of carbon loss, while the expansion of Class V areas, as projected in the Ecological Conservation Scenario, has been shown to partially alleviate this loss.

The spatial distribution of the examined phenomenon demonstrates a consistent pattern of “low in the center, high in the periphery” (Figure 9). A wedge-shaped extension in the central region exhibits low-value areas, while high-value areas are situated along the Longmen and Longquan Mountains. In comparison to 2020, the natural development scenario indicated linear distributions of carbon loss zones in the central region and dispersed points in the eastern region. The economic development scenario exhibited analogous trends, characterized by heightened carbon loss, exacerbated landscape fragmentation, and increased system vulnerability. In the context of ecological conservation, an increase in carbon stocks was observed in a dotted pattern around the “Two Mountains” and in the southern region. This phenomenon demonstrates the maintenance of spatial continuity in carbon sinks and the system’s stability.

Figure 9.

Spatial Distribution and Changes in Carbon Stocks from 2020 to 2035.

3.3. Study on the Relationship Between the Spatiotemporal Evolution of PLE Functions and Carbon Stock Responses

3.3.1. Global Moran’s I Result Analysis

A spatial autocorrelation analysis of carbon stocks in the Chengdu metropolitan area was performed from 2000 to 2020 using ArcGIS 10.8 software. The findings indicated that the Global Moran’s I values for carbon stocks in the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 were 0.208 (p < 0.01), 0.485 (p < 0.01), 0.486 (p < 0.01), 0.486 (p < 0.01), 0.487 (p < 0.01), and 0.493 (p < 0.01), respectively. This finding indicates that carbon stocks in the study area exhibit notable positive spatial autocorrelation and clustering.

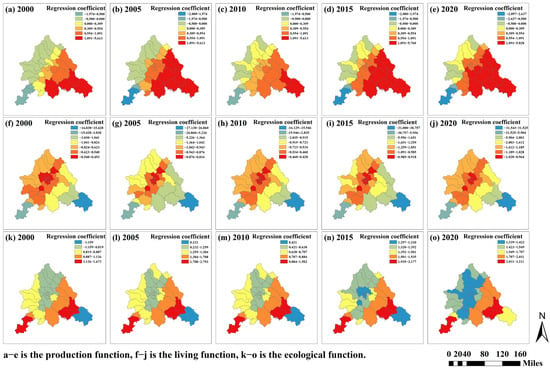

3.3.2. Analysis of GWR Model Fitting Results

Using ArcGIS 10.8 software, a geogewicht regression model analysis was conducted with counties as the basic unit. The dependent variable represented carbon stock distribution within the study area, while the independent variable reflected PLE function distribution. Developed GWR models for the Chengdu metropolitan area for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020, resulting in regression coefficient values across various temporal dimensions and counties.

R2 and AICc were employed to evaluate the validity and accuracy of the GWR model. An R2 value approaching 1 signifies a stronger explanatory capacity of the model for the dependent variable [46]. The Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected (AICc) is an estimator of prediction error and the relative quality of statistical models for a given dataset. A smaller value indicates a stronger agreement between the model estimates and the observed data.

R2 and adjusted R2 are essential metrics for evaluating the fit of regression models. Values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger alignment between the model and the observed data [47]. Table 11 demonstrates that the R2 and adjusted R2 values range from 0.570 to 0.993, indicating a satisfactory model fit.

Table 11.

GWR Model Fitting Results.

Interpretation of the model’s local R2 values reveals they are all distributed above 0.6, indicating a high degree of goodness-of-fit. Analysis of the standardized residuals shows all StdResid values fall within the range [−2.5, 2.5], demonstrating overall satisfactory model performance with no significant prediction bias.

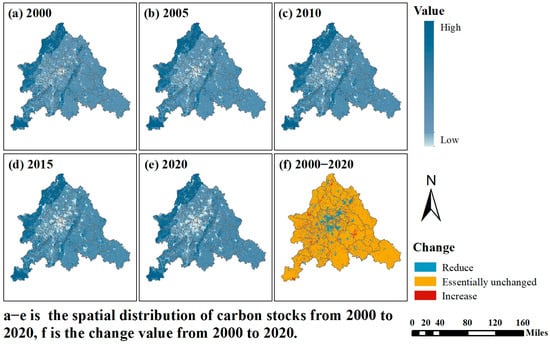

3.3.3. Study on the Impact of Temporal and Spatial Evolution of PLE Functions on Carbon Stocks

From 2000 to 2020 (Figure 10), notable spatiotemporal variability was identified between the PLE functions and carbon stocks in the study area. The relationship between production functions and carbon stocks was complex in quantitative terms. The proportion of areas with positive regression coefficients increased from 62.09% in 2000 to 81.15% in 2020 (Table 12), indicating a sustained expansion of regions where production functions positively influenced carbon stocks. This study’s finding indicated a consistent negative correlation between living functions and carbon stocks, with mean regression coefficients of −1.16, −1.96, −1.08, −2.23, and −2.30 from 2000 to 2020 (Table 13). The study’s finding indicated that ecological functions showed positive outcomes in all years except for 2000, with mean regression coefficients of 0.87, 1.41, 0.73, 1.59, and 1.65 (Table 13).

Figure 10.

Regression coefficient of the impact of the PLE functions on carbon stocks.

Table 12.

Positive Percentage Change in Production Function Area.

Table 13.

Average Regression Coefficient.

The regression coefficient for the production functions exhibits a spatial distribution characterized by positive values in the southeast and negative values in the northwest. The positive-value zone experienced a contraction phase, subsequently followed by expansion. The regression coefficient for the subsistence functions demonstrated a concentric increase from the center outward, with high-value areas progressively shifting eastward and becoming fragmented. The regression coefficient for ecological functions exhibited a distribution trend characterized by low values in the northern and central regions, which progressively increased toward the east. Post-2010, low-value zones in the central-northern regions experienced a gradual contraction, demonstrating a tendency to merge with western areas. This phenomenon indicated a notably enhanced correlation between ecological functions and carbon stocks.

4. Discussion

This study establishes an integrated GMOP-PLUS-InVEST-GWR framework to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of Production–Living–Ecological (PLE) functions and carbon stocks in the Chengdu Metropolitan Area from 2000 to 2020, projecting their trajectories to 2035. This finding holds significant practical importance for aligning regional development with ecological conservation and furthering the “The goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality”.

4.1. Mechanisms of Carbon Stock Impacts from the Transformation of PLE Functions Driven by Urbanization

Research demonstrates that the conversion from production to residential use, driven by urbanization, is the primary factor contributing to the ongoing reduction in regional carbon stocks, whereas ecological policies play a significant role in alleviating this trend. From 2000 to 2020, the study area underwent a reduction in total carbon stock amounting to 1199.63 × 104 t. This alteration corresponds with the increase in residential functional areas by 886.85 km2 and the decrease in productive functional areas by 1019.55 km2, indicating that residential encroachment on productive and ecological spaces directly contributes to carbon loss. This finding aligns with the conclusions of Bowei Wu [48], Li Jingye [49], and others. Residential functions had a significant negative impact on carbon stocks, evidenced by a regression coefficient of −2.30 in 2020. This effect displayed a concentric ring distribution pattern, marked by increasing fragmentation and a shift towards the east. From 2010 to 2015, the expansion of high-value residential zones was propelled by advancements in the Tianfu New Area, Meishan District, and Jianyang District. Socioeconomic factors, including infrastructure expansion and the development of new districts, consistently diminish carbon sink areas in urban–rural transition zones. Subsequent to 2015, this trend was mitigated through the implementation of land use regulations and ecological restoration initiatives.

Although there has been a reduction in ecological functional areas, the structural optimization resulting from initiatives like the conversion of farmland to forests has improved the local carbon sink capacity. The 2020 regression coefficient increased to 1.65 across five subregions, aligning with the ecological engineering benefits identified by Liang et al. [50] and Yao et al. [51]. Ecological restoration in the western regions may redirect agricultural or construction pressures to the southeastern plains, which could counteract regional carbon gains due to the risks associated with carbon leakage. This issue, as highlighted by Sheng et al. [52], emphasizes that the interconnected impacts of cross-regional land use changes must be acknowledged.

4.2. Spatial Patterns of Carbon Sinks Under the Interaction of Natural Background and Human Activities

Carbon stocks display a spatial distribution marked by reduced levels in the central region and elevated levels in the western region, influenced by the elevation gradient of the Longmen-Longquan Mountains. This pattern demonstrates the primary influence of natural baseline conditions on carbon sink functions, supporting research findings that natural factors primarily govern the spatial variation of carbon sinks. Jiao et al. [53] demonstrated that lithological characteristics primarily influence the climate sensitivity of carbon sinks in karst regions. In contrast, Liu et al. [54] identified that topography indirectly affects carbon sinks via vegetation structure.

Production functions positively impact carbon stocks in the southeast, as paddy fields enhance soil organic matter accumulation. Conversely, they negatively affect the northwest, where farmland expansion displaces forest and grassland. The Sichuan-Chongqing Economic Circle has successfully coordinated the carbon stock regression coefficients of ecological functions through the promotion of cross-regional eco-economic governance, which encompasses integrated ecological compensation and spatial planning. Yang et al. [55] highlighted that spatial proximity and infrastructure connectivity are essential for eco-economic synergy. Fragmented high-carbon-sink patches in western regions continue to confront threats from urban expansion, highlighting ongoing spatial governance challenges.

4.3. Policy Implications and Spatial Functions Optimization Pathways Under Multi-Scenario Simulations

Multi-scenario simulations reveal significant trade-offs among ecological, economic, and developmental objectives. Under the No Development Scenario (NDS), carbon stocks are projected to decline continuously without intervention, threatening long-term ecosystem stability. The economic development scenario (EDS), while boosting production efficiency, leads to severe ecological degradation—with living space expanding into ecological and agricultural lands by 730.91 km2, causing the greatest carbon loss (613.18 × 104 t). This outcome highlights the sharp conflict between unilateral economic growth and ecological integrity, corroborating findings from Zhang et al. [56] in the Changjiang-Zhujiang-Huangpu River urban cluster. In contrast, the Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS) demonstrates how targeted interventions enhance ecosystem quality. The ecological functional zones expanded along the “Two Mountains” belt by 454.74 km2, imposing some constraints on agricultural production but reducing carbon loss to 418.38 × 104 t—the lowest value. This confirms that prioritizing ecological conservation is crucial for safeguarding regional carbon sinks and resilience, aligning with the nationwide analysis conclusions by Li et al. [57]. While all scenarios exhibit the common trend of “ecological concentration in the west and expansion of living zones,” the EPS scheme uniquely promotes local carbon sink growth and enhanced spatial stability.

4.4. Differentiated Management Strategy for “PLE Functions” and “Carbon Sinks”

Given the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of carbon stocks, uniform spatial control measures prove ineffective. We recommend adopting a differentiated management strategy to establish a carbon enhancement system centered on three dimensions: mountain barriers, farmland carbon sinks, and urban green corridors.

The western ecological barrier zone (Longmen-Longquan Mountains) should be designated as a core ecological red line area, strictly prohibiting development and construction. Policies should shift from “preventing degradation” to “enhancing quality” by optimizing forest stand structure and establishing ecological corridors.

Eastern urban–rural transition zones and agricultural production areas require strict enforcement of permanent farmland protection and exploration of ecological compensation mechanisms for farmland and promote ecological agriculture to enhance soil carbon sequestration capacity while containing residential sprawl through rigid urban boundaries.

Central urban core areas, functioning as low-carbon reserves, should focus on internal ecological restoration and carbon compensation. By implementing green infrastructure, vertical greening, and restoring degraded ecosystems, the carbon sink potential of urban spaces can be fully unlocked.

4.5. Research Uncertainty Analysis

This study has a few limitations. For the carbon stock assessment, there are two main uncertainties. First, the carbon density values used come from existing literature and models, not direct field measurements, which introduces some data uncertainty. Second, the assessment focuses mainly on horizontal changes in surface vegetation and soil carbon, without reflecting their vertical distribution. Nevertheless, the study made relevant adjustments to the carbon density data, thereby ensuring its applicability to a certain extent.

Second, from a broader methodological perspective, the sequential coupling of multiple models (e.g., PLUS, carbon stock assessment, GWR) may lead to the accumulation of uncertainties, as the output of one model serves as the input for the next. It is important to note, however, that each model was rigorously validated prior to its application. Third, the land-use-based PLE functional classification framework is relatively simplified and could be enhanced by integrating multi-source data.

On broader applicability, the core framework is theoretically transferable to other regions with similar contexts, though its success would depend on the availability of localized data and necessary parameter adjustments.

Despite these limitations, the core conclusions of this study are robust, supported by multi-model coupling, multi-scenario comparisons, and an integrated “pattern-process” analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study uses a comprehensive research framework that integrates multi-objective optimization, spatial simulation, carbon sink assessment, and mechanism analysis. This study discusses the coupling mechanism between the structural transformation of the PLE functions and changes in carbon stock in the study area from 2000 to 2020. This is accomplished through the Coupling-Carbon Sink Assessment-Mechanism Analysis framework. The model forecasts the development of PLE functions and changes in carbon stocks by 2035, serving as a decision-support tool for national land use planning. It incorporates multi-scenario foresight, spatially explicit assessment, and mechanism analysis capabilities. The next key findings are presented:

- (1)

- Between 2000 and 2020, the PLE functions experienced the following changes: an increase in living functions, a decrease in production functions, and an improvement in the quality of ecological functions. The production functions demonstrated a consistent decrease, resulting in a reduction of 1019.55 km2 across three separate zones. The living functions showed a significant increase, with a growth of 886.85 km2 across three separate zones. The designated area for ecological functions decreased while the quality of this area improved, reflecting an increase of 83.47 km2 across five zones. High-value production zones tend to be in the central and eastern regions, whereas high-value livelihood zones correspond with urban distributions. High-value ecological zones have demonstrated stability in their distribution along the Longmen Mountains and Longquan Mountains. The livelihoods of residents in these areas have been affected by the encroachment of production spaces, whereas ecological functions demonstrated uneven expansion in subsequent stages. The evolution was equally influenced by urbanization and ecological policies.

- (2)

- Multi-scenario simulations suggest that, in the natural scenario, production and ecological functions will decline by 2035, with an increase in Zone 0 of 429.64 km2 and 835.38 km2, respectively. In the current economic context, living functions are expected to experience notable changes, characterized by a reduction of 730.91 km2 in Zone 0 and an increase of 539.69 km2 in Zone 1. Simultaneously, ecological functions are expected to diminish, accompanied by an increase of 730.91 km2 in Zone 0. The ecological scenario indicates an improvement in ecological quality, accompanied by an increase in Zone 5 by 454.74 km2. Production capacity is limited, leading to an expansion of 629.05 km2 in Zone 0. Analysis of spatial distribution patterns across scenarios indicates a consistent configuration: living functions expand contiguously, ecological functions extend along the “Two Mountains” axis, and functional conversions occur regularly.

- (3)

- Between 2000 and 2020, carbon stocks decreased by 1199.63 × 104 t, indicating a decline of 4.51%. This was mainly due to a reduction of 1250.34 × 104 t in Class I areas, which displayed a spatial distribution characterized by “lower values in the center and higher values in the west.” The urban carbon sink has been diminished, resulting in the fragmentation of high-value areas. By 2035, the reduction in carbon stocks continued, with the EDS showing the greatest decline (−613.18 × 104 t, −2.47%) and the EPS reflecting the smallest decrease (−418.38 × 104 t, −1.68%). The spatial distribution of the pattern, characterized by a gradient from lower concentrations at the center to higher concentrations at the periphery, remains evident. In the context of ecological protection, the analysis shows that carbon stocks exhibit localized expansion in the “Two Mountains” and southern regions, thereby providing improved support for carbon sink functions and system stability.

- (4)

- The influence of PLE functions on carbon stocks demonstrates intricate spatiotemporal variability. The spatial distribution of carbon sinks, influenced by natural geographical conditions, demonstrates a pattern of “higher in the west, lower in the east.” Human activities, including urbanization and ecological policies, significantly influence the dynamic evolution of these sinks. The findings demonstrate that improved production functions can increase carbon sinks, with the percentage of areas showing a positive impact rising from 58.60% to 81.15%. The regression coefficients for the living functions were primarily negative, between −1.16 and −2.30, whereas those for the ecological functions were mainly positive, ranging from 0.87 to 1.65. The spatial distribution of the production functions is characterized by a pattern of positivity in the southeast and negativity in the northwest, while the negative effects of the living functions show concentric expansion and an eastward shift. The beneficial impacts of the ecological functions are concentrated in the central and western regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and K.Z.; methodology, M.Z.; software, M.Z.; validation, M.Z.; formal analysis, K.Z.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.; visualization, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author of this paper hereby declares: During the writing process, to enhance research efficiency and ensure standardized expression, artificial intelligence tools were utilized. Their application was strictly confined to auxiliary tasks, including preliminary discussions on data analysis approaches, refinement of English expressions, and sentence structure optimization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Li, X.; O’Sullivan, M.; Wigneron, J.P.; Sitch, S.; Ciais, P.; Frankenberg, C.; Fischer, W.W. Recent gains in global terrestrial carbon stocks are mostly stored in nonliving pools. Science 2025, 387, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Ruan, Z.; Du, P. Spatial–temporal evolution analysis of multi-scenario land use and carbon storage based on PLUS-InVEST model: A case study in Dalian, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Yang, Z.H. Analysis of Spatial-temporal Variation and Driving Forces of Carbon Storage in Suzhou City Based on the PLUS-InVEST-Geodetector Model. Huan Jing Ke Xue = Huanjing Kexue 2025, 46, 2963–2975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- John, B.; Yamashita, T.; Ludwig, B.; Flessa, H. Storage of organic carbon in aggregate and density fractions of silty soils under different types of land use. Geoderma 2005, 128, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Chen, K.L.; Yu, D.Y. Evaluation on the impact of land use change on habitat quality in Qinghai Lake Basin. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 28, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.J.; Lin, H.H.; Qi, X.X. A literature review on optimization of spatial development pattern based on ecological-production-living space. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 378–391. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.S.; Zhang, X.Y. Scale effects and influencing factors on production-living-ecological functions trade-offs in the Middle Reaches of Yangtze River urban agglomeration. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, M.C.; Plieninger, T. Addressing landscape multifunctionality in conservation and restoration. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2025, 1, 112–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Caruana, J.; Zammit, A. Assessing the Capacity and Flow of Ecosystem Services in Multifunctional Landscapes: Evidence of a Rural-Urban Gradient in a Mediterranean Small Island State. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.T. Research on the Land Spatial Function Identification and Optimal Control of Henan Province from the Perspective of Symbiosis. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Liang, Y.; Shen, C.; Bu, X.B.; Wang, J. Spatial and Temporal Trade-Offs between Carbon Storage and Crop Production in Chinese Terrestrial Ecosystems, 1995–2100. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 87, 126989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The 14th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035; National Development and Reform Commission: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content%5F5592681.htm (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Luo, H.Z.; Zhang, Y.W.; Li, Y.J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, X.Y.; Luo, X.L.; Shang, W.L.; Yang, X.H.; Meng, X. Deciphering Land Use–Carbon Emissions–Economy Nexus: Decoupling Dynamics and Sustainable Planning Pathways. Nexus 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.-Z.; Zou, L.; Xie, X.-Y.; Duan, J.-J.; Shi, X.-L.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Feng, Y.-Z.; Wang, X. Unlocking Ecosystem Service Potential: Identifying High-Sensitivity and High-Potential Ecological Improvement Areas in Inner Mongolia. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 532, 146952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Guo, J.; Mei, Z. A Bayesian network-based study on the evolution of ecosystem service trade-offs intensity mechanisms in the Nansihu Basin, China. Geocarto Int. 2025, 40, 123–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.S.; Xiao, X.D.; Ding, J.Y. Multi-scenario Simulation of Evolution of Production-Living-Ecological Space and Carbon Stock Assessment in the Yellow River Basin Based on the PLUS-InVEST Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 423, 138782. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.W.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, X.C.; Chen, W.X. Dynamic Changes in the Production-Living-Ecological Space and Ecosystem Service Responses Based on Multi-Scenario Simulations: A Case Study of Hubei Province. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, C. Multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service value for optimization of land use in the Sichuan-Yunnan ecological barrier, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Yang, Q.Y.; Peng, L.X.; Su, K.C.; Zhang, H.Z.; Liu, X.Y. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and scenario simulation of production-living-ecological space at county level in Three Gorges reservoir areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Pu, Y.C.; Gao, W. Spatial correlation analysis and prediction of carbon stock of “Production-living-ecological spaces” in the three northeastern provinces, China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, H.; Zhang, T. Evolution characteristics, carbon emission effects and influencing factors of production-living-ecological space in Taihang Mountain poverty belt, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1347592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, Y.Z.; Liu, J.N.; Li, Y.B. Spatial-temporal evolution of production-living-ecological functions and their carbon emission effects in Liaoning Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 44, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.S.; Wang, W.; Xue, Y.X.; Li, B.Y.; Jin, S.Z. Simulation of multi-scenario land use change and its impact on ecosystem services in China based on PLUS-InVEST model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Pan, P.P.; Wang, X.Y.; Wen, J.Y.; Ren, J.X.; Liu, M.M. Multi-scenario simulation and functional relationship analysis of land use change in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on GMOP-PLUS coupling model. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2023, 39, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Provincial Department of Natural Resources; Office of the Chengdu-Deyang-Meishan-Ziyang Integration Development Leading Group. Chengdu Metropolitan Area Territorial Spatial Plan (2021–2035). 2022. Available online: https://www.chengdu.gov.cn/gkml/kjgh-1/1313152167166607361.shtml (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Xiao, R.; Shao, H.Y.; Li, F.; Xie, H.B. Classification evaluation and spatial-temporal pattern analysis of the “production-living-ecological spaces” in Sichuan Province. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2021, 60, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.X.; Lu, Y.Q.; Lin, J.H.; Qi, X.H.; Hu, G.J.; Li, X. Research on the evolution of spatiotemporal patterns of production-living-ecological space in an urban agglomeration in the Fujian Delta region, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 4286–4295. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Li, Y.R. Classification evaluation and spatial-temporal analysis of "production-living-ecological" spaces in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.-N.; Liao, Y.-Q. Dynamic evolution and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem and socio-economic system coupling coordination in Chengdu Metropolitan Area and its policy implications. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 2599–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guan, Q.F.; Clarke, K.C.; Liu, S.S.; Wang, B.Y.; Yao, Y. Understanding the drivers of sustainable land expansion using a patch-generating land use simulation (PLUS) model: A case study in Wuhan, China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 85, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, H.; Ju, Z.; Sun, G. Simulation and Analysis of Land-Use Change Based on the PLUS Model in the Fuxian Lake Basin (Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, China). Land 2023, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, X.P.; Li, L.X. Carbon storage comparison of ‘production-living-ecological space’ in Karst and non-Karst areas based on the InVEST-FLUS model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Zhou, S.J.; Ouyang, S.Y. The Spatial Prediction and Optimization of Production-Living-Ecological Space Based on Markov–PLUS Model: A Case Study of Yunnan Province. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Naerkezi, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. Multi-Scenario Land Use/Cover Change and Its Impact on Carbon Storage Based on the Coupled GMOP-PLUS-InVEST Model in the Hexi Corridor, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.D.; Zhen, L.; Lu, C.X.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C. Expert Knowledge Based Valuation Method of Ecosystem Services in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2008, 23, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Li, J.F.; Yao, X.W. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Ecosystem Service Value in Wuhan Urban Agglomeration. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 25, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liao, X.K.; Gan, Q.X.; Zhou, M.X. Assessment and Prediction of Ecological Risk in Gansu Section of the Yellow River Basin Coupled with GMOP and FLUS Models. Chin. J. Ecol. 2024, 43, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Government of Sichuan Province. Chengdu Metropolitan Area Development Plan. November 2021. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/ztzl/xxczhjs/ghzc/202203/t20220310_1319047.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Cheng, X.; Xiao, Z.L.; Dai, L.; Hu, X.Y.; Tan, Y.Z. Simulation and Prediction of Carbon Storage Changes in the Panxi Dry Valley Region under Policy-Oriented Scenarios. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Song, W. Quantifying and Mapping the Responses of Selected Ecosystem Services to Projected Land Use Changes. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, D.L.; He, H.; Yu, H.J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, C.; Hu, Z.H.; Li, Q. Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Driving Factors of Carbon Storage in the Yellow River Basin from 1990 to 2020. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2025, 34, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.R.; Wang, S.Q.; Cao, M.K. Vegetation and Soil Carbon Storage in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2003, 33, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.A.; Starr, M.; Clark, B.J.F. Tree Biomass and Soil Organic Carbon Densities across the Sudanese Woodland Savannah: A Regional Carbon Sequestration Study. J. Arid. Environ. 2013, 89, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, E.; Bagheri-Gavkosh, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Geravand, F. Linkage of Geographically Weighted Regression with Spatial Cluster Analyses for Regionalization of Flood Peak Discharges Drivers: Case Studies across Iran. J. Hydrol. 2021, 600, 126512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, S.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: Modelling Spatial Non-Stationarity. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D (Stat.) 1996, 47, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, L.J.; Russell, R.A.; Crabb, D.P. The Coefficient of Determination: What Determines a Useful R2 Statistic? Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 6830–6832. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; He, Y. Urbanization Promotes Carbon Storage or Not? The Evidence during the Rapid Process of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.J.; Yang, G.S.; Su, H.; Yang, J.X. Impact of Urban Expansion on Land Carbon Storage and Its Gradient Effect: A Case Study of Nanjing City. China Land Sci. 2025, 39, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.D. Methodology and Application of Carbon Sink Potential Assessment for Regional Ecological Conservation and Restoration: Based on the Research of the First Batch of Pilots for Ecological Protection and Restoration Project of Mountains-Rivers-Forests-Farmlands-Lakes-Grasslands System. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 3517–3531. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, N.; Liu, G.Q.; Yao, S.B. Evaluating the Effect of Conversion from Farmland to Forest and Grassland Project on Ecosystem Carbon Storage in Loess Hilly-Gully Region Based on InVEST Model. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 42, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, S.; Wang, Y.C. Rural Ecological Restoration Strategies in Plain Agricultural Areas based on the Identification of Ecological Characteristics and Issues through Clustering—A Case Study of Heishan County, Liaoning Province. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, F.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Gong, H.; Sheng, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, H. Bedrock Regulated Climatic Controls on the Interannual Variation of Land Sink in South-West China Karst through Soil Water Availability. CATENA 2024, 237, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, X.; Islam, T.; Jui, M.A.; Li, Y.; Gu, L. Analysis on Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity and Impact Mechanism of Carbon Sink in Qinling Mountains Based on Leaf Area Index. Trees For. People 2025, 22, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Qin, L.S.; Yang, Y.C.; Pan, J.H. Interaction between High-Quality of Urban Development and Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration Areas: Taking the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration as an Example. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 7035–7046. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.W.; Ouyang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.C. Multi-Scenario Simulation and Optimal Regulation of Urban Spatial Expansion Affecting Carbon Storage in Urban Agglomerations: The Case of Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Land Use and Carbon Storage in China: Multi-Scenario Simulation and Driving Factor Analysis Based on the PLUS-InVEST Model and SHAP. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).