Abstract

Urban Flooding is one of the most prevalent natural hazards worldwide, leading to substantial human and economic losses. Therefore, the assessment and mapping of flood hazard levels are essential for reducing the impact of future flood disasters. This study develops and integrates a methodology to evaluate urban flood susceptibility in Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan, a semi-arid region with limited prior research. Landsat imagery from 2004 to 2024 was used to analyze land use land cover change (LULCC), indicating that built-up areas increased from 124 to 180 km2 in 2004 to 2024, respectively, while agricultural land decreased from 1978 km2 to 1883 km2 during the same period. Climate data exhibit increases in temperatures and intensifying rainfall, exacerbating flood hazards. Geospatial analysis of elevation, slope, drainage density, and proximity to water bodies highlights the high susceptibility of low-lying areas. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was employed to integrate diverse flood risk factors and produce accurate flood hazard maps. The findings show that very-high flood susceptibility zones expanded from 1537 to 1699 km2 in 2004 to 2024, whereas low-susceptibility zones declined from 131 km2 to 110 km2. Socioeconomic indicators such as population density, built-up density, and education accessibility were also incorporated into the assessment. This study underscores the need for adaptive land use planning, resilient drainage systems, and community-based flood risk reduction strategies. The findings provide actionable insights for sustainable flood management and demonstrate the value of combining GIS, remote sensing, and multi-criteria analysis in data-scarce, conflict-affected regions.

1. Introduction

Climate change is altering the hydrological cycle around the world, leading to extreme weather conditions [1]. Over the past few decades, both the intensity and frequency of natural disasters have increased globally, resulting in significant human and socioeconomic losses. Large-scale analyses show a dramatic escalation in disaster occurrences, particularly since the 1960s, with the most substantial increases and economic losses reported in the 2000s and 2010s [2,3]. The economic losses due to urban flooding can be immense, with global weather-related disaster losses exceeding $300 billion in 2017, and the trend is rising due to increased urbanization and climate change, which cause heavy rainfall and flood events [4]. Globally, floods are the most frequently occurring and widespread natural disaster [5].

Besides rainfall intensity, the main causes that trigger urban floods include unplanned urban sprawl, increased impervious surfaces such as concrete and asphalt, and anthropogenic activities with natural water-cycles, such as altering stream banks and modifying hydraulic characteristics of streams [6,7,8]. Flood disasters have affected an increasing number of people globally in the 21st century, with recent studies estimating that over two billion people have been impacted by floods in just the past 20 years [9]. Afghanistan is affected by climate change at a very high rate, leading to more frequent and severe extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and heatwaves. The country has experienced a significant rise in average temperature of about 1.8 °C since 1950, which has intensified these events and increased the risks of crop failure, livestock starvation, and disease outbreaks [10,11]. According to a 2024 report, Afghanistan is ranked fourth among the most climate-vulnerable countries globally, highlighting its extreme susceptibility to climate-related impacts such as drought, food insecurity, and displacement [12]. Afghanistan has experienced several severe flood events in its history, with recent years bringing particularly devastating impacts. In 2022, a major flood struck the Pul-e-Alam and Khoshi districts of Logar province, marking one of the most disastrous years for the country and causing widespread damage and devastation [13]. Another significant event occurred on 26 August 2020, when extreme flash floods hit Charikar city in Parwan province, resulting in the deaths of around 150 people and the destruction of nearly 500 houses [14,15]. Floods in Afghanistan not only cause immediate destruction but also have long-term impacts on food security, livelihoods, and economic stability, affecting roughly one million Afghans annually [16]. Urban populations are highly vulnerable to climatic extremes due to factors such as rapid urbanization, high population density, inadequate infrastructure, and social inequalities [17,18]. These populations often face limited food availability, water stress, destruction of livelihoods, and both physical and mental health challenges, with women and the urban poor population at particular risk due to limited adaptive capacity and decision-making power [19,20]. The interactions between urban growth and climate change are evident, while urban expansion and impervious surfaces drive runoff and flood risk and climate change increases the frequency and severity of extreme precipitation events [21]. Urban systems are recognized as complex and adaptable, comprising intertwined socio-ecological and socio-technical designs. These systems involve dynamic interactions between natural, technological, and social components, which together shape urban resilience, sustainability, and quality of life [22,23]. An index-based approach to flood resilience assessment measures the social, economic, ecological, and infrastructural components of communities by integrating multiple indicators into a composite index. Studies in Alexandria, Egypt, and several cities in China have developed comprehensive flood susceptibility and resilience indices using methods like principal component analysis (PCA), analytic hierarchy process (AHP), and entropy weighting to objectively select and weight indicators across these four dimensions [24]. Integrated decision support systems, such as digital twins and planning support layers, allow urban planners to simulate the impacts of land use and drainage system performance under different climate scenarios, improving the ability to make informed, resilience-focused decisions [25].

A recent study applied a multi-criteria decision-making approach, specifically the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to map flood resilience in urban areas by focusing on three main aspects of the capability of the drainage system, the urban community’s ability to recover quickly from flood losses, and the urban system’s capacity to remove flood water [26]. Advanced visualization technologies, such as digital twins, virtual reality, and GIS-based mapping, further enhance the ability to display spatial and temporal changes in flood resilience, supporting more informed and participatory decision-making [27]. Urbanization in Afghanistan has led to rapid and disproportionate growth in major cities like Jalalabad in Nangarhar Province, which has expanded its built-up area by 30% between 1998 and 2018, outpacing smaller towns in the region [28]. This trend is driven by strong factors such as better facilities, economic opportunities, and services in larger cities, which attract residents from rural areas and smaller towns, further accelerating urbanization and making these cities even more dominant. The consequences of this rapid, uneven urbanization include increased pressure on infrastructure, environmental degradation, such as loss of vegetation and higher land surface temperatures, and depletion of natural resources like groundwater. Urbanization, loss of forest cover, and inadequate land use planning have further amplified flood risks, making populations more vulnerable to these disasters.

Various evaluation methods can yield divergent outcomes for the same problem, though achieving consistent conclusions remains challenging. This study introduces, for the first time at the provincial scale, a multi-criteria decision-making based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process approach for flood assessment, thereby addressing a methodological gap not previously examined in this region. This study aims to provide a comprehensive, integrated assessment of urban flood susceptibility in Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan, by combining land use and land cover change analysis, climate variability, and geoenvironmental factors through remote sensing, GIS, and multi-criteria decision analysis. Given the region’s data scarcity and rapid urbanization, we address the critical gap in this work by applying the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to weigh diverse flood risk indicators, thereby producing spatially explicit flood susceptibility maps. The main purpose of this study is to generate actionable insights that inform adaptive land use planning, resilient infrastructure development, and community-based flood risk reduction strategies tailored to the unique socio-environmental context of a conflict-affected, semi-arid region.

2. Study Area

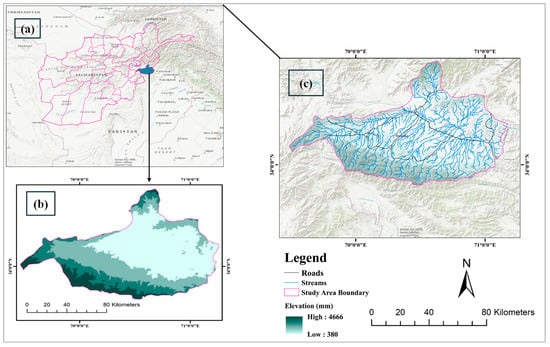

The Eastern Hindu Kush region, including Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan, is characterized by rugged mountainous terrain with elevations ranging from 2000 to 3500 m above mean sea level. This area forms part of the broader Hindu Kush Mountain system, which is distinguished by deep valleys, high peaks, and a complex mosaic of microclimates resulting from its diverse topography. Available research provides limited but valuable insight into the region’s demographics. For instance, a 2003 survey in Nangarhar Province recorded 362 households, with an average of 2.8 respondents per household aged 15 years or older. The region’s complex relief has been largely shaped by tectonic interactions between the Indian and Eurasian plates, leading to the accretion of multiple Lithtectonic blocks and the formation of prominent suture and fault zones.

These processes are associated with several major orogenic mountain-building events, the Variscan, Hercynian, Cimmerian, and Himalayan Alpine orogenies, each contributing to the region’s intricate geological structure. The geology of the Eastern Hindu Kush, particularly in Nangarhar, is dominated by metamorphic and sedimentary formations, including gneiss, schist, and limestone, interspersed with Quaternary alluvial deposits along valley floors. The structural framework is controlled by fault systems and suture zones, a result of the ongoing collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates, which has produced steep gradients and differential erosion. Hydro geologically, the Kabul River Basin and its tributaries form the principal drainage system, where permeable alluvial aquifers occur along river valleys, facilitating groundwater recharge during wet seasons. In contrast, the upland zones underlain by impermeable bedrock and thin soils exhibit limited infiltration, promoting rapid surface runoff during high-intensity rainfall events.

The study area illustrates the spatial relationship between rock types, fault structures, elevation classes, and drainage networks, providing improved context for understanding flood susceptibility in the region. The study region (Figure 1) highlights that flood-prone areas are typically concentrated in low-lying alluvial plains and valley bottoms composed of unconsolidated materials. Nangarhar Province is periodically affected by flash floods and fluvial flooding, primarily triggered by intense rainfall and rapid snowmelt from high-elevation zones. Owing to the steep slopes and narrow valleys of the Hindu Kush, flash floods are the most frequent and destructive type of flooding, occurring after short-duration, high-intensity rainfall events during the monsoon season (June–September). Fluvial flooding occurs in some low-lying areas when the Kabul River and its tributaries overflow their banks, while pluvial surface water flooding occasionally affects semi-urban areas with inadequate drainage infrastructure. Rainfall in the province is concentrated in the summer months, often exceeding 80–100 mm during extreme events, while significant snowfall occurs in winter [29]. The combination of high elevation, steep terrain, and intense monsoonal precipitation creates a mosaic of microclimates supporting diverse vegetation from dense forests on southeastern slopes to open woodlands and steppe grasslands elsewhere. Recent studies in Nangarhar confirm that local farmers perceive substantial climate variability, including rising temperatures, more frequent droughts, and altered precipitation patterns impacting agriculture and water resources [30]. Climate projections indicate that eastern Afghanistan, including Nangarhar, may experience increased summer precipitation under some future scenarios, though significant uncertainty remains among models [31]. Together, these geological, hydrological, and climatic characteristics explain the area’s high susceptibility to both drought and flooding.

Figure 1.

Study area location map (a), elevation (b), and (c) drainage network of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan.

3. Dataset

Satellite, reanalysis, and observed data products play a critical role in climate and hydrological research, particularly in regions with limited ground-based observations. These datasets improve spatial accuracy and minimize systematic errors, thereby enhancing the robustness of environmental analyses. Landsat imagery (Landsat 5, 7, and 8) from 2004, 2014, and 2024, with a 30 m resolution, was employed for land cover classification and change detection, focusing on NIR, Red, and Green bands for vegetation and surface differentiation. DEM data from ALPSRP262080370-RTC and ALPSRP262080360-RTC (2010, 12.5 m resolution) provided topographic information, crucial for terrain corrections and understanding land use variations. Population density data from World Pop (2004–2024, 97 m resolution) were integrated to explore demographic influences on land cover changes. Finally, ERA5 Reanalysis rainfall data (2004, 2014, 2024, 0.25° resolution) offered precipitation estimates, essential for understanding the role of rainfall in land cover and flood dynamics, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data acquisition table.

Random Forest LULC Classification and Validation

The Random Forest (RF) algorithm is widely recognized for its high accuracy and robustness in LULC classification, especially in heterogeneous landscapes and over multiple time periods [32]. Multispectral Landsat imagery from Landsat 5, 7, and 8 can be effectively processed using a supervised classification approach in Google Earth Engine (GEE), with the RF model trained on representative training samples selected through visual interpretation and reference datasets. Defining land cover classes such as built-up, agriculture, water bodies, and open space based on spectral characteristics and an effective approach in remote sensing and land cover mapping. Randomly distributing training samples across the study area is a common strategy to capture the variability within each land cover class, and splitting the dataset into 70% for model training and 30% for validation is widely used to ensure robust model assessment [33]. Classification performance is commonly assessed using a confusion matrix, which provides detailed information on the number of correct and incorrect predictions for each class, allowing calculation of metrics such as precision, recall, producer’s and user’s accuracy, and overall accuracy. Reported overall accuracies of 92%, 94%, and 91% with Kappa coefficients of 0.91, 0.92, and 0.89 for 2004, 2014, and 2024, respectively (Table 2) indicate high classification reliability and strong agreement between predicted and actual land cover classes.

Table 2.

Accuracy metrics of Random Forest–based LULC classification (2004–2024).

4. Methodology

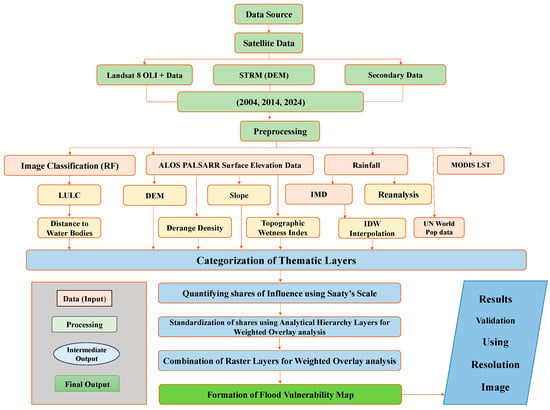

The methodology applied in this study follows the structured sequence in Figure 2 to assess urban flood susceptibility in the study area. RS data from Landsat’s 5, 7 and 8 and DEM from STRM (2004, 2014, 2024) were processed for LULC classification using the RF model. Data preprocessing was performed to improve the quality and ensure the reliability of the results. Various thematic layers, including slope, distance to water bodies, and topographic wetness index, were integrated with secondary data such as population density, rainfall, and MODIS LST. Temporal trends were analyzed using the Sen’s slope method, while rainfall distribution was estimated using IDW interpolation. All factors were then normalized and combined using the AHP and weighted overlay analysis. This methodology generated a comprehensive flood vulnerability map by quantifying the influence of each factor, integrating both physical and socio-economic variables, and offering insights for adaptive flood risk management.

Figure 2.

Methodological workflow of the study.

4.1. Sen’s Estimator of Slope

Theil–Sen slope estimator [34] was employed in this study to quantify the magnitude and direction of linear trends in the seasonal and annual rainfall time series. This non-parametric method computes the median of all pairwise slopes between data points, providing a robust measure of trend magnitude that is less sensitive to outliers and non-normal data distributions compared to conventional least-squares regression [35]. The slope between two data points in the time series was determined using the following expression:

where Q = slope between and ; = data point at time j; data point at time k; j = time after time k.

4.2. Spatial Interpolation Using Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW)

The Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method (Shepard, 1968) was used to interpolate rainfall data and generate spatially continuous precipitation surfaces. IDW estimates unknown values as a weighted average of nearby observations, where weights decrease with increasing distance. The estimated rainfall at an unsampled location (p0) is calculated as follows:

- Z(Xο) = estimated value at the unknown location;

- Z = observed value at the known location;

- di = distance between and ;

- p = power parameter (commonly set to 2) that controls how rapidly influence decreases with distance;

- n = number of neighboring points used in the interpolation.

The IDW interpolation method was applied in a GIS environment to generate continuous rainfall surfaces from CHIRPS data (2004, 2014, 2024), which were integrated with LULC and geophysical factors in the AHP framework to map flood susceptibility in Nangarhar Province.

4.3. Rainfall Variability and Trend Analysis (2004–2024)

Flooding in Nangarhar Province is mainly caused by intense and irregular rainfall events. The region experiences two distinct rainfall regimes: winter precipitation (December–March) from western disturbances and summer monsoon rains (June–September) associated with the South Asian monsoon. Major flood events typically occur between July and September, when short-duration, high-intensity rainfall and cloudbursts are common. In recent years, climate change and rapid urbanization have altered rainfall patterns, increasing the frequency and severity of flash floods and enhancing urban flood susceptibility across the province.

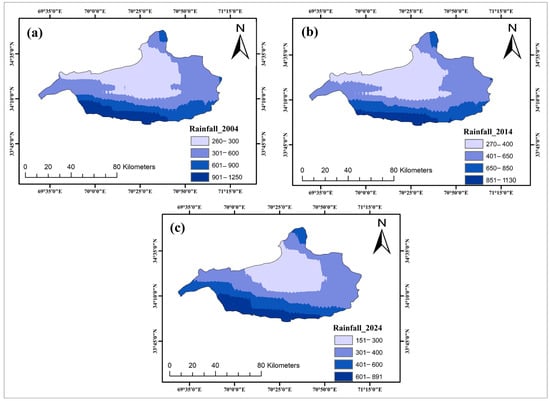

Rainfall variability across Nangarhar Province was analyzed using CHIRPS precipitation data for 2004, 2014, and 2024, matching the temporal framework of the LULC analysis. The rainfall data were spatially interpolated using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method in a GIS environment, generating continuous rainfall distribution maps for each period (Figure 3a–c). In 2004 (Figure 3a), annual rainfall ranged between 260 mm and 1250 mm, with the highest precipitation observed in the southern and central regions. By 2014 (Figure 3b), rainfall patterns shifted slightly northward, ranging from 270 mm to 1130 mm, indicating a modest decline in overall intensity but a broader spatial spread of mid-range rainfall zones. In 2024 (Figure 3c), the total rainfall further decreased to 151–891 mm, particularly across northern and central areas, showing a gradual drying trend over the two decades.

Figure 3.

IDW-interpolated rainfall distribution in Nangarhar Province for (a) 2004, (b) 2014, and (c) 2024.

Temporal trends derived from Sen’s slope estimator confirm this decreasing rainfall tendency, revealing negative slopes across much of the province, consistent with regional climatic drying. These spatial and temporal variations in rainfall, when integrated with LULC change data within the AHP-based flood susceptibility framework, demonstrate how declining rainfall and urban expansion jointly alter runoff dynamics. The rainfall maps represent multi-year averages corresponding to each study period, providing a realistic depiction of climatic variability rather than a single-year snapshot. The observed reductions in precipitation intensity and spatial redistribution suggest increased flood variability and localized inundation risks, emphasizing the need to consider short-term rainfall fluctuations in urban flood adaptation strategies for Nangarhar Province.

4.4. Socioeconomic Indicators of Flood Susceptibility

4.4.1. Population Density

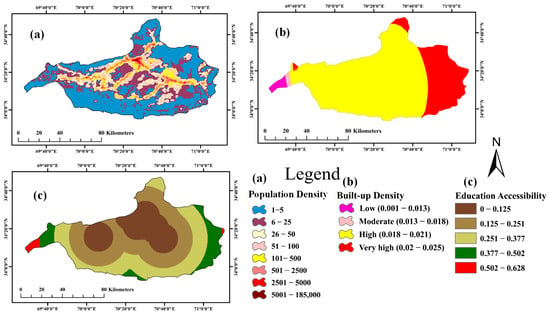

Population density (Figure 4a) serves as a key socioeconomic indicator influencing flood susceptibility in Nangarhar Province. Urban areas with higher population density tend to have more built-up and paved surfaces, which can reduce water infiltration and contribute to groundwater depletion [36]. Hazard zones are geographic areas identified as being at higher risk for natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, cyclones, and landslides, and these zones are subject to potential losses in the event of such disasters. Exposure refers to the extent to which people, property, and infrastructure are present in these hazard zones, making them vulnerable to catastrophic environmental stress and potential economic, social, and human losses [37]. Studies have shown that a significant proportion of buildings and critical infrastructure are located within hazard hotspots, increasing the likelihood of substantial losses when disasters occur. The population density range of 5001 to 185,000 people per square kilometer is extremely high and represents some of the densest urban environments globally.

Figure 4.

Socioeconomic indicators of flood susceptibility of the study area: (a) population density, (b) built-up density, and (c) education accessibility.

4.4.2. Built-Up Density and Urban Flood Susceptibility

Built-up density, which reflects the concentration of impervious surfaces like buildings and paved areas, plays a significant role in flood generation and runoff patterns, as shown in Figure 4b. High-density development increases impervious coverage, reducing the land’s ability to absorb rainfall and leading to greater surface runoff and higher flood risk [38]. Studies show that not only the total amount but also the spatial distribution of impervious surfaces can intensify flash flooding and alter the timing and magnitude of peak runoff, especially in urbanized watersheds.

Urban morphology, including building congestion and floor area ratio, has been identified as a dominant factor influencing the magnitude and spatial clustering of flood risk, especially in high-density urban areas [39]. The relationship between built-up density and flooding is further complicated by local factors such as drainage capacity, topography, and rainfall patterns, but the expansion and spatial arrangement of impervious surfaces remain key drivers of urban flood hazards. A built-up density value in the range of 0.02 to 0.025 typically represents the proportion of land area covered by impervious surfaces, such as buildings and paved areas, within a given spatial unit.

4.4.3. Education Accessibility and Flood Resilience

Education accessibility, as shown in Figure 4c and indicated by the spatial distribution of educational facilities, is closely linked to community awareness and adaptive capacity toward flood risks [40]. Research from flood-prone regions shows that higher levels of education are associated with greater awareness of climate risks and a stronger intention to adopt adaptive measures, such as early warning systems and household-level flood preparedness. Communities with better access to education tend to have higher adaptive capacity, as education enhances understanding of flood risks, encourages proactive behavior, and supports the development of local coping strategies [41]. Areas with higher accessibility to schools, particularly within urban centers, are generally associated with greater public awareness, improved preparedness, and stronger institutional response to flood events. Research shows that schools play a crucial role in disaster risk education, serving as hubs for awareness and preparedness activities that benefit both students and the wider community. Integrating education into resilience assessment tools and disaster planning is recommended to enhance both immediate preparedness and long-term adaptive capacity.

4.5. Analysis of Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

The analytical hierarchy process has been widely used as a weight for various flood-related criteria such as land use, elevation, slope, drainage, rainfall, and socio-economic factors within GIS platforms for urban flood risk and resilience assessments. We also used this method to assign weights to each criterion regarding urban flood resilience. Based on the fundamental scale (Table 3), the pair-wise comparison method was employed to determine the relative weights of each criterion. The procedure involved five sequential steps: (i) conducting pair-wise comparisons of the criteria using expert judgments, (ii) aggregating the eight expert judgments using the geometric mean method, (iii) constructing the preference matrix (Table 4), (iv) deriving the normalized matrix (Table 5), and (v) computing the consistency ratio to assess the reliability of the judgments for each criterion.

Table 3.

Saaty’s fundamental scale of relative importance.

Table 4.

AHP pair-wise analysis of parameters scale.

Table 5.

Relative weights with their corresponding rank.

Pairwise comparison is the core step in the AHP, as it determines the relative importance of each criterion in urban flood resilience assessment. Therefore, assigning appropriate values to each criterion is a critical step in ensuring the accuracy of the analysis. In this study, the selection of these values was guided by relevant literature and established empirical knowledge. Consultation with domain purpose, eight experts, including GIS specialists, disaster management professionals, and urban planners, was undertaken to ensure that the pairwise comparisons incorporated both technical expertise and practical insight [42].

A structured approach was adopted in which eight experts, two from each relevant discipline, were individually interviewed to evaluate the relative importance of each criterion. Each expert provided independent assessments using the established judgment framework, thereby reducing potential group bias and ensuring a comprehensive representation of diverse professional perspectives. The numeric Rating used for judgments was taken from Table 4.

The validity of the calculated weights was assessed using the Consistency Ratio (CR), a numerical measure that evaluates the logical coherence of pairwise comparisons (Equation (5)). The CR is defined as the ratio of the Consistency Index (CI) to the Random Index (RI) (Table 6). The RI represents a standard reference value determined by the number of criteria, as established in previous studies (Table 5).

Table 6.

Random consistency indices for AHP pair-wise comparison matrices.

4.6. Geoenvironmental Distributions of Nangahar Province

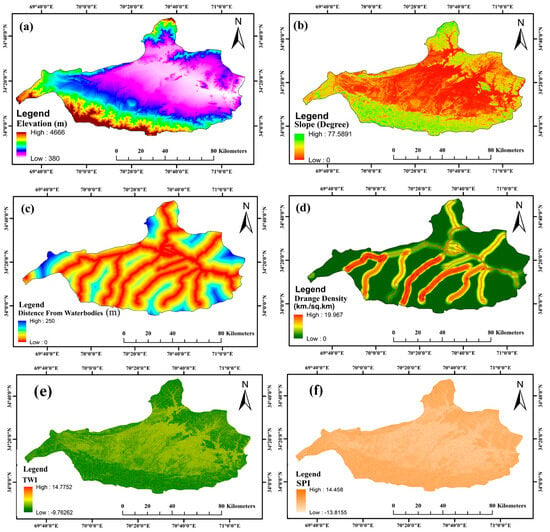

Elevation, slope, drainage density, Stream Power Index (SPI), Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), and proximity to water bodies collectively define the geomorphometric and hydrological framework that governs flood susceptibility within a watershed. These interrelated factors determine the spatial distribution of runoff, surface accumulation, and inundation potential, and thus are essential components in flood hazard modeling and risk assessment. Elevation is a critical topographic factor influencing flood susceptibility within a region [42]. Low-lying plains are more prone to inundation due to surface runoff from higher elevations [43]. The Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) PALSAR Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was utilized to assess the study area’s elevation using the Extraction by Mask tool in ArcGIS 10.7.1. Elevation ranges from 380 to 4666 m, as shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Geoenvironmental and topographic distributions of Nangarhar (a) elevation, (b) slope, (c) distance from water bodies, (d) DD, (e) TWI, and (f) SPI.

Slope serves as a critical morphometric variable influencing the velocity and direction of surface runoff. Steeper slopes enhance runoff and reduce infiltration, whereas gentler slopes facilitate water retention and prolonged inundation [44,45]. The study area slope range 0 to 77.5198 degrees is shown in Figure 5b. The slope not only determines the flow path of water but also interacts with other variables such as SPI and TWI, directly influencing erosional intensity and moisture accumulation patterns [46].

Distance from water bodies such as rivers, lakes, and streams is a critical determinant of flood risk in both urban and rural environments. Surface elevation models are commonly used to calculate the actual distance from surrounding water bodies, which is essential for hydrological analysis and land use planning (Figure 5c). Numerous studies identify distance from rivers as one of the most important predictors in flood susceptibility models. Areas closer to these water bodies are generally more susceptible to flooding due to their exposure to overflow, high water tables, and the natural drainage patterns of the landscape. Advanced methods, such as those using multi-generated data, can simultaneously detect water bodies and generate accurate DEMs, allowing for precise measurement of distances between land features and water bodies.

Drainage density, defined as the total length of drainage channels per unit area, is a key determinant of how urban landscapes respond to intense rainfall and flood events. Drainage density (DD) is typically estimated by DEMs by delineating the stream network, assigning stream order, and calculating line density, which together provide a quantitative measure of how densely streams are distributed across a landscape, as shown in Figure 5d. Moreover, the structure and connectivity of the drainage network, such as whether it is branched or looped, also influence how efficiently runoff is conveyed, with looped networks generally providing more reliable peak runoff reduction.

The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) is a widely used hydrological indicator that quantifies the potential for water accumulation in a landscape based on local slope and upslope contributing area. TWI is calculated as the natural logarithm of the ratio between the specific contributing area and the tangent of the local slope, making it especially effective for identifying areas prone to soil saturation and flooding (Figure 5e). Numerous studies have demonstrated that high TWI values correspond to locations with greater flood risk, both in natural and urban environments, and TWI-based mapping has been successfully applied for flood risk zoning, land use planning, and rapid flood hazard assessment. The accuracy of TWI-based flood mapping depends on the resolution of the digital elevation model (DEM) used, with higher-resolution DEMs providing more precise identification of flood-prone zones. The TWI formula takes the form of Equation (4) below:

The TWI, denoted as W in the equation, is calculated as the natural logarithm of the upslope catchment area per unit contour length (a) divided by the tangent of the local slope (tanβ). This index quantifies how topography influences hydrological processes by describing both the tendency for water to accumulate at a given point (through a) and the effect of gravity on water movement (through the slope, β) [43].

The Stream Power Index (SPI) quantifies the erosive potential of flowing water by integrating local slope and upstream contributing area [47]. Concurrently, a spatial analysis of the SPI was conducted using the high-resolution DEM to quantify the theoretical erosive force of surface runoff (Figure 5f). High SPI values indicate zones of elevated flow energy, which are often associated with increased channel erosion and higher flood potential, particularly in mountainous and urbanized catchments where rapid runoff can induce flash floods [48,49]. The integration of SPI into flood susceptibility models, often in combination with the (TWI) and other geomorphological factors, significantly enhances the predictive performance and spatial accuracy of flood risk mapping, supporting more effective urban flood management and mitigation strategies.

where As is the specific catchment area (m2/m) and β is the local slope angle in radians. Higher SPI values indicate zones with greater flow energy and potential for erosion, which are often linked to increased flood susceptibility, especially in urban and semi-urban environments [50].

4.7. Accuracy Assessment Metrics

where

- TP = True Positive (flooded areas correctly classified as flooded);

- TN = True Negative (non-flooded areas correctly classified as non-flooded);

- FP = False Positive (non-flooded areas incorrectly classified as flooded);

- FN = False Negative (flooded areas incorrectly classified as non-flooded).

The equations below help to determine precision (Equation (6)), obtain recall using (Equation (7)), and determine the F1-score using (Equation (9)) for each class category.

Harmonic mean of precision and recall, expressing the overall accuracy and balance between the correctness and completeness of flood classification obtained through Equation (9).

5. Results

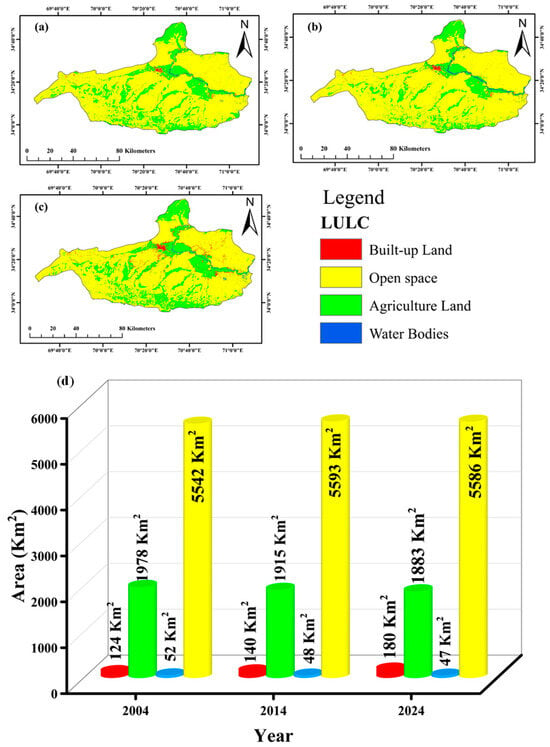

5.1. Distribution and Change in Regional LULC

GIS and remote sensing technologies are proven, cost-effective, and accurate alternatives for understanding and monitoring landscape dynamics, supporting a wide range of environmental and resource management applications. Multitemporal and multispectral RS technologies offer robust, accurate, and scalable solutions for LULC detection, mapping, and monitoring, making them essential tools for understanding and managing landscape dynamics. LULC changes, especially urbanization and the expansion of impervious surfaces, such as pavements and buildings, significantly reduce soil infiltration capacity and increase surface runoff. This leads to faster and higher peak flows during rainfall events, raising the risk and severity of flooding. In contrast, areas with natural vegetation or wetlands have higher infiltration rates and act as buffers, reducing flood risk. To understand LULC classification using RF 120-point samples per class is a validated and widely used approach in LULC mapping, balancing efficiency and accuracy. Stratified or equal sampling ensures all classes are well represented, supporting robust classification and reliable accuracy assessment, which allows for accurate mapping and monitoring of changes over time, as shown in Figure 6a–c. In this study, using remote sensing and GIS confirms a clear, measurable pattern of urban expansion over 20-year periods in diverse global contexts. Built-up areas have consistently increased, often at the expense of agricultural land, vegetation, and other natural covers. Research shows that built-up areas around Jalalabad City were relatively limited in extent and primarily clustered around the urban core and adjacent settlements. Jalalabad, as the capital of Nangarhar province, has built-up land mainly concentrated within the city boundaries and its immediate surroundings, as shown in Figure 6a. In 2004, built-up areas in Jalalabad were minimal, covering about 124 km2 and primarily concentrated around the city and its adjoining settlements, consistent with early-stage urban growth patterns. A progressive increase in built-up land area, such as from 140 km2 in 2014 to 180 km2 in 2024, is a hallmark of rapid urbanization see Figure 6c,d. This trend is widely observed in cities globally, where built-up areas expand significantly over short periods, often at the expense of agricultural and vegetative land. A gradual reduction in water bodies from 52 km2 in 2004 to 48 km2 in 2014 and 47 km2 in 2024 reflects a well-documented pattern in rapidly urbanizing regions. Numerous studies confirm that urban expansion often leads to the direct loss of surface water bodies, as built-up areas encroach on lakes, rivers, and wetlands. The decline in water body area is closely linked to reduced surface water storage capacity, which leads to a loss of surface water storage, also heightening flood risk. Slight fluctuations in open space area, as described from 5542 km2 in 2004 to 5593 km2 in 2014, then marginally down to 5586 km2 in 2024, are typical in landscapes experiencing both agricultural intensification and urban expansion, see Figure 6d. Studies show that even minor reductions in open space, often due to conversion to built-up and agricultural land, can lead to increased flood risk by reducing the land’s natural water retention and infiltration capacity. Driven by agricultural and urban expansion, it can erode the landscape’s natural flood-buffering capacity, underscoring the importance of open space conservation in flood risk management. A consistent reduction in agricultural land from 1978 km2 in 2004 to 1915 km2 in 2014, and 1883 km2 in 2024 mirrors global and regional trends where fertile floodplains are increasingly converted into residential and commercial zones. The conversion of fertile floodplains to urban and commercial uses not only reduces agricultural output but also increases flood risk and undermines food security. Studies confirm that such land use changes lead to higher flood frequency, greater flood damage, and reduced flood mitigation services. The transitions from permeable agricultural to impervious built-up land surfaces are a primary driver of increased urban flood susceptibility. Impervious surfaces such as roads, rooftops, and parking lots prevent water infiltration, leading to higher surface runoff, reduced groundwater recharge, and faster hydrologic response times. The steady decline in agricultural land area is a clear indicator of the ongoing conversion of fertile floodplains into residential and commercial zones, with significant consequences for flood risk, food security, and sustainable land management.

Figure 6.

LULC Maps of Nangarhar: (a) 2004, (b) 2014, (c) 2024, and (d) area distribution of LULC categories across these years.

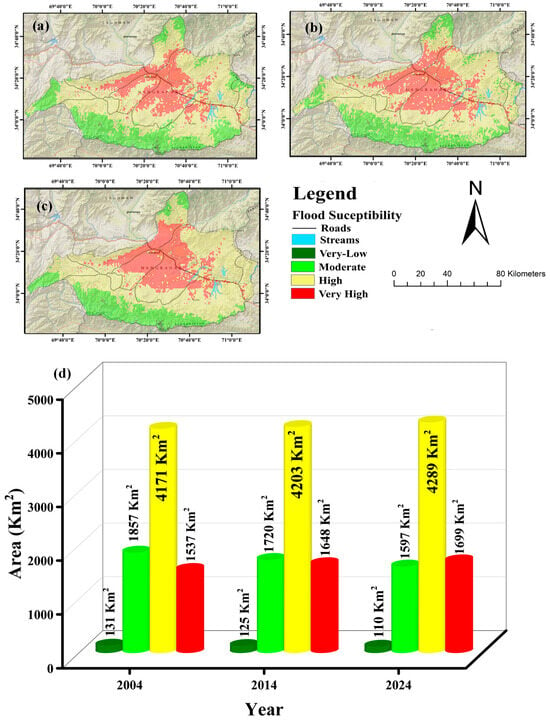

5.2. Regional Flood Susceptibility Mapping to LULC Classes

Susceptibility refers to the degree to which a system is likely to be affected by a hazard, and it is a key concept in hazard and risk assessment [51]. The assumption that flood impacts on property occur only when there is direct contact with floodwater is an oversimplification. In studies evaluating urban flood susceptibility, indicators such as building density, population density, and education accessibility are recognized as important factors, though the specific combination and weighting of indicators can vary by study. The process is checked using the maximum value of indicators, indicating a consistent and reliable judgment matrix. The weights assigned to each indicator, such as building density, population density, and education accessibility, were integrated and processed using a GIS-based AHP tool within ArcGIS to generate a flood susceptibility map. This approach is widely used in flood risk studies, where the weighted indicators are combined through spatial analysis in GIS to produce a map that visually represents areas of varying flood susceptibility. The process involves overlaying thematic layers corresponding to each indicator, applying the normalized weights, and using a weighted linear combination or overlay method to calculate a composite susceptibility score for each spatial unit. The resultant map typically classifies the study area into categories such as very low, low, moderate, high, and very high susceptibility, providing actionable insights for urban planners and disaster management authorities, as shown in Figure 7a–c. Flood susceptibility mapping (Figure 7a) shows that central plains and areas near rivers are at moderate to high risk, while elevated northern and southern regions tend to have low susceptibility. This pattern is robust across multiple studies and regions, emphasizing the critical role of topography and hydrology in flood risk distribution. Additionally, low and very low flood susceptibility in mountainous regions is robustly linked to topographic features and the preservation of natural land cover. In 2004, built-up land occupied approximately 1537 km2, which increased to 1648 km2 in 2014 and further expanded to 1699 km2 in 2024 see Figure 7d. This consistent urban growth reflects intensified urbanization driven by population pressure and infrastructural development. Limited urbanization and stable vegetation help maintain hydrological balance, reinforcing the protective effect of elevation and slope against flooding. By 2014, the spatial distribution of flood susceptibility in many regions had changed notably, with increased high-risk zones in urban and low-lying areas and a reduction in very low-susceptibility zones in Figure 7b. The expansion of high and very high flood risk zones around Jalalabad city and nearby urban settlements is a well-documented phenomenon in rapidly urbanizing land cover transformation and climate change impacts in the region. Conversely, agricultural land decreased from 1857 km2 in 2004 to 1720 km2 in 2014 and further to 1597 km2 in 2024, indicating that the conversion of fertile land into impervious surfaces and reduced vegetation cover, and unplanned development are the primary contributors to this heightened flood susceptibility. The conversion of green spaces and agricultural land to built-up areas reduces the landscape’s natural ability to absorb rainfall, further amplifying flood risk. In 2024 (Figure 7c), the pattern has become more critical, with very high susceptibility areas now occupying substantial portions of central and southeastern regions across multiple hazard types. The expansion of high-susceptibility flood areas is a direct result of urban sprawl, population growth, and climate variability, leading to greater flood risk and disproportionately impacting vulnerable communities. Additionally, water bodies exhibited a slight reduction from 131 km2 in 2004 to 125 km2 in 2014 and 110 km2 in 2024, suggesting the degradation of surface water resources, possibly due to siltation, urban runoff, and channel modification. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events, further amplifying flood hazards. Although open spaces showed a marginal increase from 4171 km2 in 2004 to 4203 km2 in 2014 and 4289 km2 in 2024, this may represent barren or undeveloped land rather than ecologically functional open areas, as shown in Figure 7d. Research consistently shows that the northwestern highlands remain relatively stable with low flood potential due to their topographic advantage, while the central plains experience increased flood hazard intensity. Addressing these challenges requires integrated urban planning, climate adaptation, and targeted support for at-risk populations.

Figure 7.

Flood susceptibility map of Nangarhar: (a) 2004, (b) 2014, (c) 2024, and (d) area distribution of Flood susceptibility map categories across these years.

5.3. LULC Dynamics and Flood Susceptibility Trends

Spatiotemporal dynamics of LULC and their corresponding flood susceptibility trends from 2004 to 2024 are shown in Table 7. Increase in built-up land, rising from 1.98% to 2.84% is indicative of accelerated urbanization, a trend consistently linked to heightened flood susceptibility due to the proliferation of impervious surfaces, which amplify surface runoff and diminish infiltration capacity. Simultaneously, agricultural land decreased from 31.62% to 29.73%, reflecting the conversion of permeable, absorptive landscapes into urban or semi-urban uses, which further reduces natural flood mitigation capacity. The reduction in agricultural coverage correlates with a decline in moderate flood zones, suggesting a loss of natural absorption areas and a shift toward more severe flood risk categories.

Table 7.

LULC changes and associated flood susceptibility trends (2004–2024).

Water bodies exhibited relative stability over the study region, with only minor fluctuations in area from 0.83% to 0.74% and consistently overlapped with zones of high to moderate flood susceptibility, reflecting their inherent hydrological role as natural flood-prone areas. The slight increase in open space from 65.57% to 66.69% may offer some buffering capacity against flood intensity; however, this effect appears limited, likely due to the simultaneous expansion of urban surfaces, which are associated with increased imperviousness and runoff. Collectively, these findings underscore that urban expansion is a principal factor driving heightened flood susceptibility, emphasizing the necessity for integrated land use planning and comprehensive flood risk management strategies to bolster hydrological resilience and promote ecological sustainability in the region.

5.4. Quantitative Validation of the Flood Susceptibility Model

Accuracy in studies is commonly assessed using a combination of metrics derived from the confusion matrix, including precision, recall, F1 score, and overall accuracy. The confusion matrix provides a detailed breakdown of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, which are essential for calculating these metrics and understanding model strengths and weaknesses. Precision measures the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions, while recall sensitivity assesses the proportion of true positives identified out of all actual positives. The F1 score balances these two by calculating their harmonic meaning, offering a single measure that accounts for both false positives and false negatives. Overall accuracy reflects the proportion of correct predictions among all predictions. To validate the reliability of the AHP-based flood susceptibility map, NDWI-derived flood inventory data were used for quantitative comparison, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Confusion matrix for validation of the AHP-based flood susceptibility map.

An overall accuracy of 82%, with a precision of 76.9%, a recall of 72.7%, and an F1-score of 74.7%, indicates that the AHP-based flood susceptibility model demonstrates strong agreement between predicted and observed flood-prone areas, as shown in Table 9. These metrics suggest the model is effective at both correctly identifying flood-prone zones with high recall and minimizing false positives with high precision, resulting in a balanced and robust performance.

Table 9.

Validation Metrics from the Derived Confusion Matrix.

Overall accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly classified instances (both true positives and true negatives) out of the total number of instances in the dataset, providing a general measure of how often the model makes correct predictions. These metrics, along with others derived from the confusion matrix, are widely used in research to assess and compare the effectiveness of classification models.

6. Discussion

6.1. Urban Expansion and Flood Hazard Interaction

Floods are consistently identified as the most frequent and widespread hydrometeorological disasters worldwide [52]. The main causes of urban floods are rapid, unplanned urban expansion, which increases impervious surfaces, such as roads and buildings, reducing natural infiltration and dramatically increasing surface runoff. This leads to higher flood peaks and more frequent urban flooding, even when rainfall patterns remain unchanged [53,54]. Urban flooding is primarily triggered when the volume of surface runoff from rainfall surpasses the capacity of urban drainage systems. This can occur in two main scenarios: (1) intense storms that quickly overwhelm sewers and drainage networks designed for lower return periods, and (2) moderate rainfall events that cause flooding due to poorly planned, undersized, or unmaintained drainage systems [55,56]. Factors such as increased impervious surfaces from urbanization, blocked or inefficient inlets, and lack of surface drainage exacerbate this risk [57,58]. Urban floods are increasingly triggered by rapid, poorly managed urbanization, encroachment, illegal construction, and lack of effective planning. These human activities amplify flood risk by increasing runoff, reducing natural drainage, and placing vulnerable populations in harm’s way [59,60]. Nangarhar, like many areas in the Kabul River Basin and neighboring regions, faces a high risk of urban flooding due to a combination of rapid urbanization, inadequate infrastructure, and exposure to extreme weather events. The region’s susceptibility is compounded by limited resilience at the household and community levels, as seen in similar flood-prone districts in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, which were also severely affected by the 2010 floods [61,62]. The 2010 floods in the region, including Nangarhar and adjacent districts, were catastrophic, destroying tens of thousands of homes, displacing large populations, and causing significant casualties. These areas have experienced repeated, large-scale flood disasters, with the 2010 event standing out for its widespread destruction and loss of life. The devastation highlighted the high susceptibility and low resilience of local communities, with many households lacking the resources or institutional support needed to recover quickly. The 2014 flood was one of the most devastating in recent history for several South Asian regions, including the Lower Chenab Plain in Pakistan and the Kashmir Valley. In the Lower Chenab Plain, the floodwaters persisted for nearly two months, causing extensive damage to both agricultural and built-up areas. In the Kashmir Valley, the 2014 flood resulted in more than 100 deaths and widespread destruction of infrastructure, with over 175,000 residential houses damaged, 80% of which were submerged to more than half their height, and nearly 20% completely collapsed [63]. Without significant improvements in urban planning, drainage infrastructure, and climate adaptation, urban flooding will become more frequent and severe due to the combined effects of unplanned development, population growth, and climate change. Proactive interventions are urgently needed to reduce future risks [64]. Therefore, it is critical to assess the resilience of the city to urban floods that would help in reducing the risk of future flooding events. In this regard, a multi-criteria, integrated assessment approach provides a robust framework for evaluating and improving urban flood resilience in Nangarhar. This method enables targeted, evidence-based interventions to reduce future flood risks and build a more resilient city.

6.2. Comparative Approaches to Flood Resilience Assessment

Globally oriented, multi-domain MCDA and MCDI frameworks provide methodological robustness and cross-context comparability [65]. The study presents a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework for urban flood resilience that uses a composite index across three thematic pillars: infrastructural, institutional, and population, often interpreted as internal capacity, to enhance the reliability of community flood resilience assessments. A multi-criteria, multi-domain approach captures the complex, interdependent factors that determine resilience, improving both diagnostic accuracy and policy guidance [66]. The specialized multi-criteria index maps flood resilience by focusing on three core capabilities: drainage system performance, urban recovery capacity, and urban water evacuation removal, while integrating them within a broader multi-criteria framework [44]. Adaptations emphasize context-specific drainage networks, local recovery dynamics, and urban water management practices, improving relevance for planning, risk reduction, and resource allocation in Nangarhar. While this framework remains robust, comprehensive assessments also incorporate structural protection, adaptive capacity, social equity, and institutional resilience [45]. This structure enhances spatially explicit assessment, scenario analysis, and policy guidance beyond single-dimension indicators. System optimization, supported by community engagement and advanced technologies, is critical for Nangarhar to address its growing flood risks and build long-term resilience.

6.3. Climate and Land Use Impacts on Flood Susceptibility

Climatic variations in eastern Afghanistan, notably the increase in summer precipitation and rising temperatures, heighten flood susceptibility by intensifying rainfall-runoff responses [46,47]. Regional studies show that precipitation during the warmest quarter and extreme rainfall events are significant contributors to flood risk. Climate change scenarios forecast an expansion of flood-prone areas in Afghanistan and neighboring South Asian countries [48]. The growth of high-risk flood zones from 2004 to 2024 corresponds with climate change intensifying extreme rainfall events, thereby increasing both the frequency and severity of urban floods. Multiple studies indicate that climate change results in more intense and frequent extreme rainfall, particularly in urban areas, thereby elevating the risk and magnitude of urban flooding [49,67]. In Nangarhar, localized topography and climatic variability interact with land use changes, creating compounded hydrological stresses. Research indicates that watershed hydrology is shaped by the interplay among terrain, climate fluctuations, and LULCC. Steep or mountainous topography exacerbates the effects of urbanization and deforestation, leading to increased surface runoff, reduced infiltration, and heightened flood risk, especially with more intense rainfall patterns [68,69]. Urban expansion and agricultural conversion further disrupt natural hydrological processes, amplifying the impacts of climate-driven changes in precipitation and temperature.

The combined effects of LULC and climate variability often surpass their individual impacts, with spatial variability in hydrological responses influenced by local terrain and land management practices [70]. The proliferation of impervious surfaces and subsequent hydrological modifications challenge existing drainage networks in urban areas such as Nangarhar. As impervious surfaces increase, a greater percentage of rainfall becomes surface runoff, overwhelming drainage systems not designed for such high volumes, resulting in heightened flood risk and surface inundation [23,71]. Inadequately designed or undersized drainage systems can exacerbate flood hazards during intense rainfall events [57]. Insufficient stormwater drainage, increased impervious surfaces, and climate change can overwhelm drainage systems even during moderate rainfall, resulting in extensive urban flooding [72]. The expansion of flood-prone zones in Nangarhar, coupled with inadequate drainage infrastructure, underscores the urgent need for adaptive drainage planning. Research from other rapidly urbanizing and flood-prone regions illustrates that adaptive strategies, such as integrating green infrastructure, increasing drainage channel capacity, and employing data-driven planning, are essential for managing increased runoff and mitigating flood risks. A combination of infrastructure upgrades, nature-based solutions, and participatory planning involving local stakeholders results in more resilient and sustainable urban drainage systems. Flexible adaptation pathways and decision-support tools enable cities to respond to climate uncertainties and evolving flood hazards, ensuring drainage improvements remain effective as conditions change. Prioritizing drainage system optimization, supported by community engagement and advanced technologies, is critical for Nangarhar to address growing flood risks and build long-term resilience.

7. Policy Implications

7.1. Hazard-Informed Urban Planning

Flood susceptibility maps developed in this study should be formally adopted in Nangarhar’s urban and provincial lands and planning frameworks. Directing new settlements, infrastructure, and critical facilities away from high-risk flood zones will reduce exposure. Zoning regulations can help prevent unplanned expansion into hazard-prone areas, ensuring safer long-term urban growth.

7.2. Strengthening Drainage Infrastructure

The rapid increase in built-up land has overwhelmed existing stormwater drainage systems. Investment in resilient drainage, such as retention basins, wider culverts, and permeable pavements, is urgently needed. Incorporating green–blue infrastructure like wetlands and vegetated swales can further enhance natural flood absorption.

7.3. Protection of Agricultural and Ecological Land

Agricultural land loss to urban sprawl has amplified surface runoff and reduced natural flood buffers. Policies restricting the conversion of fertile land and encouraging riparian vegetation can mitigate flood risk. Ecological restoration of small wetlands and floodplains offers cost-effective natural flood management solutions.

7.4. Climate-Resilient Development Planning

Projected increases in rainfall intensity demand revisions to infrastructure design standards. Roads, bridges, and housing must be built to withstand more frequent and intense flood events. Water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) approaches should be piloted in Jalalabad to demonstrate climate-resilient planning.

7.5. Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction (CBDRR)

Local communities, particularly refugees and vulnerable groups, face the highest flood risks. Early warning systems using SMS alerts, community sirens, and mobile apps can save lives. Training programs on flood preparedness and incentives for resilient housing can empower households to adapt.

7.6. Integration into National Disaster Risk Reduction Frameworks

The results should inform Afghanistan’s National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA) and be linked with global resilience programs. Flood susceptibility maps can guide insurance schemes, evacuation routes, and relief planning. Embedding this geospatial evidence in national frameworks will reduce disaster losses.

7.7. Data-Driven Policy and Monitoring

Remote sensing and GIS provide an affordable approach for continuous flood monitoring. Authorities should establish a provincial flood monitoring cell in Jalalabad to update hazard maps every 3–5 years. International donors and academic institutions can support capacity building in geospatial risk assessment.

8. Conclusions

Research demonstrates that integrating ArcGIS, remote sensing, and the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) is an effective approach for assessing urban flood resilience, especially in data-scarce and rapidly urbanizing regions. By introducing a resilience framework tailored to Nangarhar, the assessment presented in our study provides a foundation for future research and practical applications in other cities of Afghanistan, where rapid urbanization and unplanned infrastructure have increased flood risks. Additionally, a lack of advanced early warning systems, low public awareness, insufficient flood risk assessment and management policies were identified in the study region, making it highly vulnerable to urban flooding. This study exhibits that the likelihood of urban floods is highest in the central city of Jalalabad in Nangarhar province, while other parts have lower flood potential, aligning with broader research on urban flood risk assessment. Research on urban flood susceptibility consistently shows that the central part of the city is more susceptible to flooding than the peripheral part of the city. This heightened susceptibility is primarily due to higher population density, greater concentration of impervious surfaces, and more intense development in city centers, all of which reduce natural water recycling and increase surface runoff during heavy rainfall events. Additionally, overwhelmed or insufficient drainage systems in the central area of the city further contribute to the increased flood risk. Due to the lack of coordination from the local government, the city’s water drainage system has become less effective, significantly increasing the risk of urban flooding. Future studies on urban flood resilience in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan, would benefit from incorporating high-resolution satellite imagery and advanced analytical tools such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) to enhance model efficiency, accuracy, and reliability. Research from other regions demonstrates that using deep learning models, including ANNs and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in combination with satellite data, significantly improves flood susceptibility and risk assessments, providing more precise and actionable flood maps for urban planning and disaster management. These findings can help the government agencies, NGOs, UN bodies, and local community-based organizations (CBOs) to implement both structural and non-structural measures that enhance community resilience to urban floods. Effective strategies include reinforcing and maintaining critical infrastructure, developing robust drainage systems, and integrating blue–green infrastructure such as parks and wetlands to manage stormwater and reduce flood risk. Research highlights the importance of community involvement, social capital, and collaboration between authorities and residents in both the preparedness and recovery phases. Additionally, community education and awareness programs provide precise information about extreme weather events, such as through community-led warning systems and improved weather forecasts, empowering residents to take early action and reducing susceptibility. Integrating social inclusiveness and disaster response budgets into flood risk management plans further enhances resilience, especially in resource-deficient settings. These combined strategies create a more robust foundation for communities to withstand, adapt to, and recover from urban flood events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A. and W.P.; Methodology, I.A.; Software, I.A.; Formal analysis, I.A.; Resources, K.Y.F. and S.M.A.; Data curation, H.M.B.J.; Writing—original draft, I.A.; Writing—review & editing, W.P., S.U., K.Y.F., S.M.A., E.R.A. and A.A.A.A.; Visualization, S.U.; Supervision, W.P.; Funding acquisition, W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R673), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R673), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bertilsson, L.; Wiklund, K.; de Moura Tebaldi, I.; Rezende, O.M.; Veról, A.P.; Miguez, M.G. Urban flood resilience—A multi-criteria index to integrate flood resilience into urban planning. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R.; Aleksova, B.; Lukić, T. Geospatial and temporal patterns of natural and man-made (Technological) disasters (1900–2024): Insights from different socio-economic and demographic perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feifei, W. Formation Mechanism of High-Cold and High-Altitude Landslide Disasters Caused by Complex Goaf Groups. J. Min. Sci. 2025, 61, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Ikram, R.M.A.; Su, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Matrix scenario-based urban flooding damage prediction via convolutional neural network. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J. Global flood disaster research graph analysis based on literature mining. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSousa, S.; Bhaskar, A.S.; Kelleher, C.; Livneh, B. Understanding Spatiotemporal Patterns and Drivers of Urban Flooding Using Municipal Reports. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Qi, W.; Xu, H.; Zhao, K. An integrated quantitative framework to assess the impacts of disaster-inducing factors on causing urban flood. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 1903–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, T.; Li, J. Experimental and MPM modelling of widened levee failure under the combined effect of heavy rainfall and high riverine water levels. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 184, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, S.; Curran, A.; Bouwer, L.M. Floods have become less deadly: An analysis of global flood fatalities 1975–2022. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 6327–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhundzadah, N.A. Analyzing temperature, precipitation, and river discharge trends in Afghanistan’s main river basins using innovative trend analysis, Mann–Kendall, and Sen’s slope methods. Climate 2024, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A. At the Crossroads of Physics and Climate: A Comprehensive Review of Climate Change in Afghanistan. Nangarhar Univ. Int. J. Biosci. 2024, 3, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Xu, B.; Kamara, M.; Rahmani, B. Impacts of climate change in Afghanistan and an overview of sustainable development efforts. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 2, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nab, A.W.; Kumar, V.; Rajapakse, R. Innovative methods for rapid flood inundation mapping in Pul-e-Alam and Khoshi districts of Afghanistan using Landsat 9 images: Spectral indices vs. machine learning models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 2495–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel-Rastgar, F.; Sivakumar, V. A case study of an extreme flooding episode in Charikar, Eastern Afghanistan. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2023, 14, 4689–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atefi, M.R.; Miura, H. Detection of flash flood inundated areas using relative difference in NDVI from sentinel-2 images: A case study of the August 2020 event in Charikar, Afghanistan. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolchi, J.; Wang, H.; Pede, V. Impact of floods on food security in rural Afghanistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 112, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, E.W.; Amoadu, M.; Obeng, P.; Sarfo, J.O. Climate change, urban vulnerabilities and adaptation in Africa: A scoping review. Clim. Chang. 2024, 177, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X. Global space-time patterns of sub-daily extreme precipitation and its relationship with temperature and wind speed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 084019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngu, N.H.; Tan, N.Q.; Non, D.Q.; Dinh, N.C.; Nhi, P.T.P. Unveiling urban households’ livelihood vulnerability to climate change: An intersectional analysis of Hue City, Vietnam. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 19, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ping, W.; Razzaq, A.; Muhammad, B.J.H.; ALI, W. Assessing urban thermal field variance and surface urban heat island effects. An Ecological Study in Malakand Division, Pakistan Évaluation de la variance du champ thermique urbain et des effets d’îlot de chaleur urbain de surface. Une étude écologique dans la Division de Malakand, au Pakistan. Georeview 2024, 34, 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Andreadis, K.M.; Wing, O.E.; Colven, E.; Gleason, C.J.; Bates, P.D.; Brown, C.M. Urbanizing the floodplain: Global changes of imperviousness in flood-prone areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Samuelsson, K.; Marcus, L.; Gren, Å.; Legeby, A.; Berghauser Pont, M.; Barthel, S. Frontiers in social–ecological urbanism. Land 2022, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, R.; Yu, B.; Li, T.; Yeh, S.-W. A moderator of tropical impacts on climate in Canadian Arctic Archipelago during boreal summer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdrabo, K.I.; Kantoush, S.A.; Esmaiel, A.; Saber, M.; Sumi, T.; Almamari, M.; Elboshy, B.; Ghoniem, S. An integrated indicator-based approach for constructing an urban flood vulnerability index as an urban decision-making tool using the PCA and AHP techniques: A case study of Alexandria, Egypt. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truu, M.; Annus, I.; Roosimägi, J.; Kändler, N.; Vassiljev, A.; Kaur, K. Integrated decision support system for pluvial flood-resilient spatial planning in urban areas. Water 2021, 13, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; Muñoz-Arriola, F.; Garg, D.; Khare, D. Assessing urban community resilience to flood using a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making approach: A case of Guwahati City, Assam, India. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, V.; Piadeh, F.; Behzadian, K.; Kapelan, Z. A critical review for the application of cutting-edge digital visualisation technologies for effective urban flood risk management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Qiao, X.; Tariq, A. Impact assessment of planned and unplanned urbanization on land surface temperature in Afghanistan using machine learning algorithms: A path toward sustainability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, S.; Joshi, N.; Maurya, H.K.; Gupta, D.; Sharma, K.K. Understanding precipitation characteristics of Afghanistan at provincial scale. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 150, 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.A.; Sarwary, M.; Baber, B.M.; Qaderi, A.S.; Safi, Z. Farmer Perceptions to Climate Variability and Adaption Strategies in Nangrahar Province. Nangarhar Univ. Int. J. Biosci. 2024, 3, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, M.; Qiao, X. Evaluating the impact of urbanization patterns on LST and UHI effect in Afghanistan’s Cities: A machine learning approach for sustainable urban planning. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Saber, M.; Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H.; Homayouni, S. Urban land use and land cover change analysis using random forest classification of landsat time series. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, Z.; Wang, L.; Yu, W.; Tan, D.; Gao, B.; Feng, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y. Improving the accuracy of land cover mapping by distributing training samples. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSubih, M.; Kumari, M.; Mallick, J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Islam, S.; Singh, C.K. Time series trend analysis of rainfall in last five decades and its quantification in Aseer Region of Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, R.; Pokorná, L. Parametric versus non-parametric estimates of climatic trends. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2004, 77, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazly, M.I. Excessive Water Usage, and Its Impact on Underground Water Depletion in Jalalabad City Zone. Nangarhar Univ. Int. J. Biosci. 2024, 3, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, R.; Wu, J.; Tang, R.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Multi-hazard direct economic loss risk assessment on the Tibet Plateau. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2368075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardana, N.; Abenayake, C.; Jayasinghe, A.; Dias, N. An urban density-based runoff simulation framework to envisage flood resilience of cities. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jia, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z. Synergistic assessment of multi-scenario urban waterlogging through data-driven decoupling analysis in high-density urban areas: A case study in Shenzhen, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazlbash, S.K.; Zubair, M.; Manzoor, S.A.; ul Haq, A.; Baloch, M.S. Socioeconomic determinants of climate change adaptations in the flood-prone rural community of Indus Basin, Pakistan. Environ. Dev. 2021, 37, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, S.R.; Khanal, N.R.; Nepal, P.; Rai, S.K.; Ghimire, P.K.; Pradhan, N.S. Community assessment of flood risks and early warning system in ratu watershed, Koshi basin, Nepal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Y. Progress in Geospatial Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen, R.; Zinko, U.; Seibert, J. On the calculation of the topographic wetness index: Evaluation of different methods based on field observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2006, 10, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Yue, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Yan, X. Discussion on Major Drought Issues in the Northern Drought-Prone Belt in China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E678–E706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kang, J.; Liu, W.; Li, M.; Su, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, X.; Shang, L.; Zhang, F.; Guo, C. Design and study of mine silo drainage method based on fuzzy control and Avoiding Peak Filling Valley strategy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janizadeh, S.; Kim, D.; Jun, C.; Bateni, S.M.; Pandey, M.; Mishra, V.N. Impact of climate change on future flood susceptibility projections under shared socioeconomic pathway scenarios in South Asia using artificial intelligence algorithms. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.F.; Lu, H.L.; Wang, G.Q.; Qiu, J. Long-term capturability of atmospheric water on a global scale. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Dong, Y.; Bai, L.; Dong, W.; Qu, A. Predicting Urban Residents’ Climate Change Risk Perceptions: The Role of Heat and Green Space Exposure Indicators in Harbin’s Residential Environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 134, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne, G.; Waduge, A.; Bogahawaththa, M.; Rathnayake, U.; Meddage, D. Adapting cities to the surge: A comprehensive review of climate-induced urban flooding. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabameri, A.; Seyed Danesh, A.; Santosh, M.; Cerda, A.; Chandra Pal, S.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Roy, P.; Chowdhuri, I. Flood susceptibility mapping using meta-heuristic algorithms. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2022, 13, 949–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Zhang, J.; Hussain, M.; Ullah, S.; Liu, X.; Khan, S.N.; Baig, M.A.; Hassan, W.; Al-Shaibah, B. Gis-based urban flood resilience assessment using urban flood resilience model: A case study of Peshawar City, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. Knowledge domain and development trend of urban flood vulnerability research: A bibliometric analysis. Water 2023, 15, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Bourke, R. Urbanization impacts on flood risks based on urban growth data and coupled flood models. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Zhu, G.; Jiao, Y.; Qiu, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q. Soil salinity patterns reveal changes in the water cycle of inland river basins in arid zones. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 5049–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palla, A.; Colli, M.; Candela, A.; Aronica, G.; Lanza, L. Pluvial flooding in urban areas: The role of surface drainage efficiency. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S663–S676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Qi, X.; Chen, L.; Zhu, G.; Meng, G.; Wang, Y.; Huang, E.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, W. Hydrological processes in continental valley basins: Evidence from water stable isotopes. Catena 2025, 259, 109314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Jia, H.; Ashraf, A.; Yin, D.; Chen, Z.; Ahmed, R.; Israr, M. A novel GIS-SWMM-ABM approach for flood risk assessment in data-scarce urban drainage systems. Water 2024, 16, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Qiu, H.; Wei, Y.; Huangfu, W.; Yang, D. A proposed method for landslide detection based on transfer learning and graph neural network. Geosci. Front. 2025, 16, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, E.; Rahman, A.A.; Rainis, R.; Seri, N.A.; Fuzi, N.F.A. The impacts of land use changes in urban hydrology, runoff and flooding: A review. Curr. Urban Stud. 2023, 11, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, D.; Bai, Y.; Fang, H.; Sun, B.; Wang, N.; Li, B. Intelligent siltation diagnosis for drainage pipelines using weak-form analysis and theory-guided neural networks in geo-infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2025, 176, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Ye, J.; Abid, M.; Khan, J.; Amir, S.M. Flood hazards: Household vulnerability and resilience in disaster-prone districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan. Nat. Hazards 2018, 93, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Tayyab, M.; Zhang, J.; Shah, A.A.; Ullah, K.; Mehmood, U.; Al-Shaibah, B. GIS-based multi-criteria approach for flood vulnerability assessment and mapping in district Shangla: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.; Chisenga, C.; Saleem, N.; Hassan, H. Operational monitoring and damage assessment of riverine flood-2014 in the lower Chenab plain, Punjab, Pakistan, using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Zhu, G.; Meng, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Miao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shi, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q. Historical dataset of reservoir construction in arid regions. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashar, N.; Lakra, H.S.; Shaw, R.; Kaur, H. Urban Flood Resilience: A comprehensive review of assessment methods, tools, and techniques to manage disaster. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2023, 20, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]