Abstract

Agroecological farming has long been described as more fulfilling than conventional agriculture, in terms of farmers’ labour and sense of autonomy. These assumptions must be reconsidered with adequate theoretical perspectives and with the empirical experience of recent studies. This paper introduces the concept of channels of labour control in agriculture based on four initiatives in Senegalese agroecological horticulture. We build on Bourdieu’s theory of social fields to elaborate a framework that articulates multiple channels of labour control with the type of capital or surplus values structuring power relations during labour processes. Although each of the four agroecological initiatives place a clear emphasis on improving farmers’ well-being, various top-down channels of labour control exist, maintaining most farmworkers as technical demonstrators rather than agents of transformation. These constraints stem from dependence on foreign funding, enforcement of uncoordinated organic standards, and farmers’ incorporation of cultural values through interplays of knowledge and symbolic power with initiative promotors. Pressure on agricultural workers is exacerbated by the context of the neo-liberalisation of Senegalese agriculture and increasingly difficult climatic conditions. A more holistic approach of agroecological initiatives is needed, including the institutionalisation of protected markets for their products, farmers’ inclusion in agroecosystem governance and inclusiveness in the co-production of agroecological knowledge, taking cultural patterns of local communities into account. Recent attempts to scale-up and politicise agroecology through farmers’ organisations, advocacy NGOs, and municipalities may offer new perspectives for a just agroecological transition in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords:

agroecology; work; Senegal; habitus; Bourdieu; social field; political ecology; agrarian studies 1. Introduction

1.1. Reviewing Working Conditions in Agroecology

Agroecology first emerged in the 1970s as a scientific approach and as a set of ecologically sound agricultural practices (e.g., reducing chemical inputs, preserving soil and water, diversifying crops, and trees and livestock production) [1]. Agroecology then progressed to combine its technical and ecological aspects with multiple social and political goals, such as supporting farmers’ autonomy and improving their labour conditions [2,3,4,5]. Under what Altieri and Toledo described as an “agroecological revolution” [6], the agroecological movement promotes ethical principles such as environmental stewardship, food sovereignty, and the virtue of frugality and other spiritual values [7,8]. In this line of thought, Timmerman and Felix [9] claim that work in agroecology is more meaningful compared to conventional farming and can lead to more “contributive justice”, as it compensates for the heavy workload by providing other resources and elements of well-being such as freedom (autonomy of the farm), personal initiative, increased dexterity, social and peer recognition, inter-influence among farmers, and development of farmers’ skills, knowledge, and capabilities.

Despite these claims, little empirical research has been dedicated to the consequences of farmers’ adoption of agroecology for labour conditions, particularly in the Global South. There are many definitions of agroecology and of associated concepts such as sustainable intensification and organic agriculture. Agroecology can be seen as a form of ecological modernisation based on the enhancement of biodiversity and ecological interactions at different levels [10]. Agroecology also links scientific research, practices aimed at enhancing ecological interactions, and social movements involving farmers and consumers [3]. In this study, we therefore refer to agroecology as a holistic agricultural approach that is inclusive of multiple social and ecological sustainability criteria. In this sense, we consider it an umbrella concept that embraces sustainable intensification and organic agriculture as steps toward sustainable agroecological systems.

Research on work-related aspects of agroecology has been mainly dedicated to quantitative measurements in order to optimise labour productivity by reducing labour inputs and increasing yields [11]. In such contexts, agroecological farming is generally understood as being more labour-intensive than industrial farming [12,13]. Some studies argue that agroecology offers better working conditions, but they mainly focus on Western contexts. A major literature review in Europe carried out 20 years ago showed that agroecology requires about 12% more work and has lower yields (by about 30% compared to conventional agriculture), but can allow for greater work satisfaction depending on workers’ perception of what satisfactory work is [14]. More recently, other European studies have reported a positive relationship between farmers’ adoption of organic farming and subjective well-being [15,16]. These studies show that work satisfaction in agroecology also depends on personal and family life and, more generally, on social structures, including gender relations, the organisational aspects of work, types of activity, mobilisation of knowledge, and farmers’ cultural background.

However, other recent studies from Europe and the US provide a less optimistic picture. For example, in their comparative study of Belgian horticulture, Dumont and Baret [17] argue that working conditions in agroecology are not a priori better compared to conventional farming. In both systems, farm workers get positive intrinsic benefits from their work, face technical challenges, and feel they make a useful contribution to society. Dumont and Baret’s findings explicitly demonstrate that although all types of producers feel constrained by their socio-economic context, small agroecological producers suffer the most due to unaffordable prices for land, low food prices, difficult conditions for accessing subsidies, and increasing competition for the supply of vegetable boxes (2017:61). In the US, reciprocal relations with consumers in community-supported agriculture (CSA) can lead to psychological pressures on famers and situations of “self-exploitation”, whereby farmers accept painful activities, long working days, and wages lower than the regional average [18]. In France, agroecological farmers selling through short food-supply chains also feel intense psychological pressure due to the challenge of simultaneously delivering crops that ripen at different times in a vegetable basket, along with the need to perform tedious production tasks every day [19].

In sub-Saharan Africa, international-development organisations and NGOs depict agroecological farming as a new panacea to fight climate-change impacts, reduce international migration by creating decent jobs, and improve livelihood outcomes. However, these booming initiatives have remained understudied [20]. The scarce scientific literature on agroecology in the region suggests a rather critical stance towards the transformative potential of the farming approach [11,21,22,23]. Trade-offs exist between additional workload efforts and ecological or economic benefits [11,22]. Mugwanya [21] argues that the anti-corporate, anti-industrial sentiment inherent in agroecology is disconnected from current economic realities in many African countries and, rather, will trap farmers in poverty instead of enhancing their independence due to the inevitable and substantial productivity trade-offs. A few critical studies warn that the additional workload gets supported by the most vulnerable groups such as women, landless workers, and youth [24,25]. Based on empirical cases studies in Malawi and Kenya, these authors argue that gender issues must be addressed in order to avoid reproducing inequalities in decision-making processes and agroecological practices, resulting in a disproportionate workload for women.

Although the cases mentioned above present mixed positions, they converge on two main ideas. First, in similar socio-economic contexts, the level of workers’ autonomy in making decisions about their work is a core determinant of their working conditions and satisfaction. Second, work conditions strongly depend on social, economic, and political contexts on broader scales and cannot be limited to technical aspects. Both conditions have been scrutinised in the literature in regard to the concept of “labour control” in agricultural development [26,27,28]. These studies have highlighted that farmers’ autonomy and working conditions in agriculture require movement away from the farm level and include contextual socio-economic aspects such as the articulation between global and local governance mechanisms and the impact of economic capital upon marginal areas’ development.

Our study builds on this idea and expands it further. In particular, we argue that agroecological initiatives involve complex mechanisms of labour control that cannot be captured through an analysis limited to employment conditions. We therefore coin the concept of channels of labour control to refer to the multiple mechanisms through which external actors directly or indirectly influence farmers’ working conditions. We present an analytical framework to better define the channels that make sense in agroecological systems and apply it to four cases of agroecological initiatives in Senegal. Considering these six channels allows us to understand to what extent agroecological initiatives enhance farm workers’ labour conditions. We finally discuss the specificities of agroecological initiatives in terms of labour control and the challenges that they imply in the prospects for just agroecological transitions in sub-Saharan Africa [29]. By just agroecological transitions, we mean that agroecological initiatives are not solely limited to a modification of productive techniques leading to ecological efficiency and sustainable yield. To be a “just transition”, agroecology should also preserve or enhance the most vulnerable farmers’ working conditions, avoid unequal access to incomes, inputs, productive infrastructure, land and natural resources, and improve farmers’ agency and autonomy. Some early researches in sub-Saharan Africa have already started to warn against some potential negative impacts of agroecological initiatives on the most vulnerable groups [24,25,30] and the risk that the movement may be co-opted by the “sustainable intensification” lobbies to become the “new green revolution” [31].

1.2. Channels of Labour Control and Multiple Values: A Tentative Framework

Our framework primarily proposes to zoom out the analysis of labour control from the prism of the production process to a broader view that embraces contextual socio-economic mechanisms. Working conditions in agriculture are often evaluated at a farm level, whereas in reality, they depend on multiple systemic and external factors. Literature on local labour-control regimes has explained the articulation between global and local mechanisms of labour control [26,27,28]. Interest has been focused, in particular, on how financial capital shapes labour conditions and processes in marginal areas. However, factors other than financial or formal regulatory instruments play central roles in shaping both work conditions and workers’ autonomy, especially in alternative food systems. Classical mechanisms of labour control such as access to markets, financial incentives, and productive infrastructures give room to other influencing dimensions.

To capture these dimensions, we rely on Bourdieu’s theory of social fields, capitals, and habitus [32,33] with a Marxist interpretation of surplus value to understand the complex patterns of power relations structuring labour in agroecological farming. We put a particular focus on post-colonial North-South-cooperation contexts. Bourdieu’s theory has been applied in research on organic farming in Europe to explain the logics of changing farmers’ cultural preferences [34]. These approaches consider agriculture as a “social field” in which structured power relations depend on the distribution of different types of “capitals”: economic, cultural, social, and symbolic. Farmers’ habitus and practices result from farmer’s incorporation of socially validated norms, values, and symbols, leading to a constructed conception of the “good farmer” [34]. Building on Bourdieu’s theory, we look at different types of capitals not only as predefined resources but also as surplus values produced out of the labour process and structuring power relations [35].

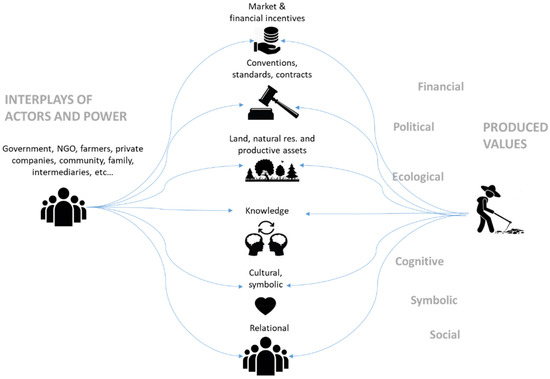

In addition, we postulate that labour control within the agroecological-labour process not only responds to direct coercion, but is relayed by different channels. We identify six major channels of labour control helping to characterise the level of workers’ dependency on or autonomy from external pressures: (1) access to market opportunities and financial incentives; (2) contractual conventions and standards such as fair trade, organic certifications, or specific terms of references between parties [36]; (3) access to land, natural resources, and productive assets [37]; (4) knowledge and technical aspects legitimating “who has the right” solution [38]; (5) symbolic and cultural values contributing to influencing farmers’ engagement [39]; and (6) interpersonal relations considered from a relational perspective [40,41] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Channels of labour control and their indirect links to surplus values.

Figure 1 presents the six channels of labour control and links them with various types of surplus value (and capitals): (1) financial; (2) political; (3) ecological; (4) cognitive; (5) symbolic; and (6) social.

1.2.1. Market Mechanisms and Financial Channel

Market mechanisms and financial transfers are classical instruments of labour control. This aspect includes wages, market strategies, and subsidies. First, wages as financial compensation for farmers’ work are a direct instrument of labour control. Second, access to markets allows farmers to sell their product(s) and compensates for farmers’ work efforts [37]. Stakeholders involved in conventional and alternative food systems develop strategies that modify the smallholders’ conditions of access to local, national, or international markets. These strategies directly affect farmers’ working conditions, as financial compensation for work is a core aspect of working conditions. Third, direct and indirect funding through subsidies is a strategy for supporting agroecological farming but also a good way to legitimate control of the labour process.

1.2.2. Conventions, Standards, and Contract Channel

Conventions, standards, and contracts are binding and non-binding agreements between workers and other parties such as employers, customers’ associations, certification mechanisms, or other third parties involved in production processes. Working contracts, as well as explicit or implicit organisational rules or quality-oriented regulations (organic-labelling criteria, sanitation rules, etc.) can become factors in farm workers’ coercion or protection [36,42]. Any or all of these factors can contribute to social expectations around productive practices that influence the everyday work activities of farmers. In the field of organic farming, organic-certification criteria have deeply transformed the conception of farmers’ work. Additional manual weeding, the implementation of new productive techniques, and an increase in working time are direct consequences of these rules governing farmers’ everyday “professional world” [40].

1.2.3. Land, Natural Resources, and Other Productive Assets Channel

Access to land, natural resources, and other productive assets highly influence farmers’ working conditions [37]. The capacity of some stakeholders to facilitate or hinder access to these resources is a core channel of labour control. Land reforms, large-scale land acquisitions, and land registration are institutional transformations that can affect rural workers by exerting further pressure on or alleviating working conditions. Access to productive infrastructure also contributes to work-effort reduction. For example, access to irrigation infrastructures can considerably reduce the amount of work on a farm and allow farmers to invest their working time in other activities.

1.2.4. Knowledge Channel

Technical knowledge is a source of legitimacy and determines who provides technical support and who is in charge of the more painful and repetitive activities. A capacity to influence someone’s work is bestowed upon a person who masters the knowledge considered legitimate. Based on knowledge legitimacy, an experienced field technician influences farmers’ everyday work by providing advice but also by incentivising farmers to act according to their own protocols [38]. Through their everyday work, agroecological farmers also produce innovative technical knowledge that can be considered a surplus “cognitive value” produced through farmers’ practical experience [38]. Nevertheless, this knowledge is also a direct source of value and empowerment for various actors such as supporting NGOs that compile them and use them in NGO-to-farmers and farmers-to-farmers programmes [43]. NGOs and other technicians, thus, capitalise on farmers’ experience and use it as an instrument for advocacy and legitimacy. In this sense, knowledge is a channel of labour control but also a “surplus value” that can be appropriated by these actors.

1.2.5. Symbolic and Cultural Channel

Agricultural work is always associated with various symbolic and cultural values such as the traditions associated with food production, processing, and consumption, or spiritual beliefs in relation to land and natural entities. The modern world is not exempted from these values. Contemporary examples are the association between production and wellbeing, animal welfare, or other environmental ethics or the value of quality products [44]. The development of these values through discursive practices influences workers’ attitudes. Some values combine with workers’ intrinsic motivations or are partially rejected or considered as exogenous and contested. The labour process contributes to workers’ incorporation of new values in their habitus [34]. Through their physical and cultural practices, farm workers potentially produce symbolic and cultural value, for example by transforming landscapes into cultural heritage that can be then valued by other stakeholders in their marketing strategies (i.e., a bioregion label, etc.). This is why we can say that farmers not only make edible products, but also produce symbolic and cultural surplus value out of their daily work and other activities.

1.2.6. Interpersonal-Relations Channel

Interpersonal relations between farmers and other actors are key aspects of negotiations around the labour processes. A relational perspective states that these relations are not closed in given or static structures. However, these relations are in a constant renegotiation and dynamic of actions where all players have agency and a margin to manoeuvre [45,46]. Networks of social interrelations (including the interplays of statutory positions, charism, and reciprocity) influence workers’ ability to orient their everyday activity. Labour control engages in a form of reciprocal relation and can be classically established between employers and employees, but also between workers and consumers or between workers and any other human and non-human entities [46]. For example, in small groups (such as a short value chain), a sense of loyalty and corporate welfare can play an important role in social control of labour, independent of formal reciprocal agreements such as wages or statutory positions [47]. As we have mentioned in the introduction, this sense of loyalty (e.g., in a direct consumer/producer relationship) can in some cases push farmers to “self-exploitation” to fulfil a consumer’s expectations based on a personal-interrelation experience [18].

2. Materials, Methods, and Context

2.1. Data Collection

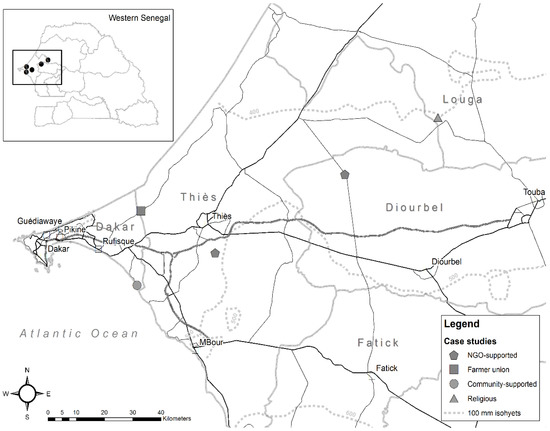

Our study focused on Senegal, where diverse agroecological initiatives exist, some of them more than 30 years old. Senegal has been designated as a pilot country to launch a large agroecological-transition programme in the West African region [48]. We focused on four cases located in North-Western Senegal in the regions of Dakar, Thiès, Djourbel, and Louga (Figure 2), in two different ecosystems: the coastal area and the hinterland. Our cases cover four different modes of production in Senegalese horticulture: the NGO-supported initiatives; the small-scale farm attached to an organic union; community-supported agriculture; and what we have called the “religious agriculture” corresponding to a case of the Sufi brotherhood largely present in the country.

Figure 2.

Localisation map of the four types of agroecological initiatives.

The data-collection process took place over three months from February to April 2019. We visited the production areas and organised focus groups with 4–10 agricultural workers and their managers. In two cases, managers did not let us interview the farmers or workers independently from their supervision. In two other cases, it was possible to talk directly to the farmers and agricultural workers individually or in groups. For this reason, it was not possible to propose a completely homogenous sample in terms of interviews. However, this position of managers was taken as an indicator of labour control and further explored during individual interviews. Semi-direct interviews were also carried out with 17 key stakeholders (NGOs, public agencies, and private associations) at national and regional levels to characterise the social, organisational, and power-related aspects of those agroecological initiatives. In each agroecological initiative, we had the opportunity to interview the highest-responsibility person (NGO director, spiritual chief, union leader, or local manager) and one or two of their technical staff (technical advisors and supervisors). All interviews and focus groups were recorded and subject to selective re-transcription and systematic annotation. We used the Atlas.ti 8 Windows software to code and analyse the transcripts or systematic annotations and perform our analysis.

2.2. Context: Agricultural Policies and Peasant Organisations in Senegal

In Senegal, the agricultural sector is in a critical situation due to severe droughts, declining soil fertility, and food insecurity, all exacerbated by climate change and neo-liberal policies [49]. Until 1984, farmers were supported by the government through inputs provision (improved seeds, fertiliser, and pesticides) and commercialisation support. Since the mid-1980s, however, the New Agricultural Policy tied to International Monetary Fund (IMF) structural-adjustment programmes has led to the complete disengagement of the State and privatisation of the Senegalese food system [50]. From 2000, the government of President Abdoulaye Wade aimed at reaching food security through “special programmes”1 that sought industrialisation and attempted to attract big investors from foreign countries [51]. However, this policy did not achieve its objectives and involved severe cases of land grabbing that led to conflicts with peasants, especially in the Senegal River Valley [52].

After 2012, President Macky Sall reaffirmed the productivist scope of the national agricultural policy with the Programme d’Acceleration de la Cadence de l’Agriculture Sénéglaise (PRACAS)2 plan enacted in 2014, and the National Agency for Insertion and Agricultural Development (ANIDA), which give continuity to Wade’s programmes. PRACAS represents the main agricultural-development strategy, with the objective of reaching self-sufficiency in rice and onions, as well as increasing the production of a few commercial crops such as groundnuts and counter-season fruit and vegetables [53]. Although Sall’s government has recently proposed a “green orientation” for his National Development Plan (called PSE-vert), involving a reforestation programme, most of the current agrarian policies remain unchanged. The government’s lines of actions include developing large-scale irrigation, subsidising chemical inputs, implementing hybrid seeds and mechanisation, conducting conventional research, and securing large agribusiness access to land and water. As an example, a recent report estimated that 700,000 hectares of farmers’ land were subject to dispossession, leading to new conflicts and farmer mobilisations [54].

These liberalisation policies and the development of agribusinesses had strong consequences for labour and income control. On the one hand, liberalisation led to a reduction of male domination over labour in patriarchal households [55]; however, it also reinforced dependency on global-production networks [28]. Different institutions, actors, and dynamics shape labour-control regimes on different levels, from the household up to the global scale [28,56]. Anthropological studies on labour aspects of agricultural farming in Senegal present labour-related questions as complex and hybrid phenomena wherein religion, markets, and the stigma of the colonial order persisting till today coexist in the perspective of growing neo-liberalisation and giving place to particular forms of peasant capitalism [57,58].

These agrarian transformations also witnessed the emergence of peasant movements that attempted to gain ground by defending the interests of family farmers. Initially, the Fédération des organisations non-gouvernmentales du Sénégal (FONGS), created in 1978, and the Cadre national de concertation des ruraux du Sénégal (CNCR), established in 1993, were set up by local peasant organisations to play the role of negotiator with the State and defend peasant interests. Although these organisations succeeded in gaining a political presence at national and international levels, the present movement remains strongly dependent upon external aid (mainly from NGOs), state coercion, and political co-optation [59].

2.3. Emerging Initiatives of Organic and Agroecological Farming

The first systematic organic-farming trials in Senegal started at the end of the 1980s and obtained significant increases in yields [60]. More recently, several agroecological educational programmes such as the FAO Farmer Field School, French national research organisations (National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) and Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD)) and NGOs combined with local farmers’ initiatives have implemented innovative agroecological practices sporadically all over the country [61,62]. These initiatives principally promote crop diversification using old varieties of cereals adapted to local climatic conditions (millet, sorghum, fonio, rice, and niebe), combined with fertiliser and highly nutritive trees (i.e., Moringa oleifera, Acacia Albida, Detarium Senegalensis) [63,64]. Such initiatives also promote the use of bio-compost (mainly livestock manure) and bio-pesticides (such as neem leaves (Azadirachta indica)), irrigation techniques for saving water and conserving soil (mulching), and the restoration of overexploited land (i.e., using Andropogon and Euphorbia plants) [65].

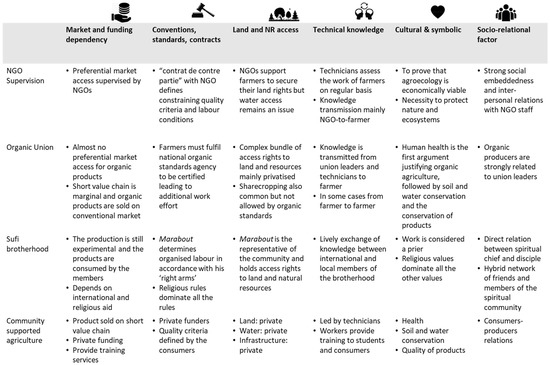

Such technical experiences have been accompanied by a growing mobilisation of farmers’ organisations to create solidarity networks, provide technical assistance, and information, creating banks of local seed varieties and develop value-chain and advocacy support [61,62]. In recent years, collaboration and coordination between actors promoting agroecology has increased, in particular with the creation of a multi-stakeholder coalition platform, the Dynamic for the Agroecological Transition in Senegal (DyTAES) in May 2019. The DyTAES has steered a participatory consultation process in the whole country to elaborate a set of policy recommendations to the central government and other powerful actors (e.g., agribusiness) [66]. Furthermore, local farmer organisations promoting agroecology increasingly steer and take part in farmer’s mobilisations to access natural resources such as land and water [67]. Despite these developments, very little social-science research has been carried out to assess the potential for scaling-up these pilot experiences at a broader level and to see if similar experiences have the potential to generate farmers’ initiatives and autonomy and to emancipate working conditions. In the next section, we present four distinguished types of agroecological-transition initiatives in Senegal. Figure 3 at the end of the following section provides a systematic summary of each initiative according to the six channels of labour control.

Figure 3.

Channels of labour control in Senegalese agroecological initiatives. Source: Elaboration from authors’ field-work interviews.

3. Results

3.1. Presentation of the study areas and selected agroecological initiatives

The four case studies lie within the Sahelian climatic region, which has a hot semi-arid climate with an annual mean temperature over 25 °C and annual mean precipitation between 400 and 500 mm. Nearly all precipitation falls between June and October with high inter-annual variability. Soils are predominantly sandy and permanent surface-water streams are absent. Traditionally, large extensions of millet (Pennisetum glaucum), fonio (Digitaria exilis), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and groundnuts (Arachis hypogaea) were planted during the rainy season. After 1950, horticulture crops including African aubergines (Solanum macrocarpon), tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), chilies (Capsicum spp.), onions (Allium cepa), and lettuce (Lactuca sativa) were introduced to the area to supply the growing cities of Dakar and Touba, encouraged by development programs to improve local food security. These crops mainly thrive during the cool and dry season and heavily rely on groundwater-based irrigation and expensive infrastructures. Therefore, horticulture is particularly well developed in locations closer to the coast, where groundwater is shallow, and where cooler oceanic winds protect fields from dry and hot Harmattan winds and sandstorms. In more inland locations, horticulture requires higher investments due to deeper groundwater tables and the need to protect soils and crops from wind erosion.

3.1.1. NGO-Supported Initiatives

NGO-supported initiatives are horticulture-production programmes almost entirely supported by international NGOs. We examined two similar cases of international NGOs that explicitly refer to the concept of agroecology and run rural-development programmes in several West African countries.

In the first examined case, the village authority provides land access to a community association recognised as a “group of economic interest” (GIE)3 represented by an elected board and composed of 185 workers, 95% of whom are women. A local branch of an international NGO based in France supports the constitution or consolidation of the GIE and provides GIE members with access to irrigation and essential productive assets (tools, inputs). The NGO also provides permanent technical supervision for the production of tomatoes, onions, turnips, aubergines, and lettuce, and supports the commercialisation of products in local and national markets. The products have no third-party organic certification and the use of pesticides is allowed in cases of high necessity (e.g., pest infestation). For this reason, farmers and technicians refer to agroecology as being more permissive than organic agriculture. Labour is supervised by NGO technicians who work very closely with local farmers and create close social inter-relationships. Farmers have to respect a “contrat de contre partie” (counterpart contract) with precise hours of work, turnover, and irrigation time. They must also commit to implement agroecological practices such as organic fertiliser use, mulching, agroforestry, and pest management, which are defined by the NGO headquarters in France and adapted locally by an NGO technician. As one of the two regional coordinators stated, “We provide technical skills; in return, farmers are asked to apply them” (NGO supervisor, 1.3.2019). Major issues mentioned by the technician are the high cost of water pumping and fuel shortages as reasons why some farmers have abandoned production. Local supervisors are also mobilised from the communities according to their technical knowledge or their level of responsibility within community hierarchy to back-up NGO technicians. In this case, NGO staff work very closely with local farmers and create close social inter-relationships.

In the second case, the villagers had their own association (not a GIE) to manage a water drill constructed by a foreign charity organisation in the 1980s. The association board is elected by the villagers and a water committee is designated by the board. A national NGO supported by diverse donors based in Europe and the USA is currently supporting 34 women producing organic cabbage, tomatoes, peppers, onions, lettuces, and mangoes on a total of 1.8 hectares. The NGO has an agreement with the village association by which they provide technical training, seeds, and commercialisation support via a cooperative running an organic-vegetable market. In turn, producers commit to managing water carefully and not bringing in synthetic fertilisers or pesticides. The NGO has no permanent local technician and has designated two local supervisors and one villager to be responsible for the water drill. The three men are not paid but are given a large plot (1 ha in total) with mechanised irrigation facilities, allowing them to reduce their workload and dedicate time to supervising the group of women producers. All women members must take part in watering, which takes two hours every day between 6 and 8 am. After that, they generally return home to take care of their children before school and come back in the afternoon if other activities are required. During the focus group with the producers and the supervisors, women complained about the painfulness of watering, which represents 80% of their workload, and about the very low incomes from their activities. Low incomes are mainly due to unreliable provision of the fuel used for water pumping and high water-drill-maintenance costs.

In both NGO-supervised cases, the approach is very much top-down and strongly steered by the NGO headquarters in Europe and in Senegal. Farmers’ work is supervised and controlled very strictly, and the NGOs’ technical criteria are mandatory for all farmers, particularly in the first case, which is steered by a local branch of an international NGO. Farmers are also expected to perform regular demonstrations for visitors (e.g., researchers, politicians, and civilians) coming to the experimental fields. The NGOs want to demonstrate to a large segment of the Senegalese population the potential of agroecology for creating ecologically and economically sound production: “We want to prove that agroecological production is economically viable. This will be enough to attract farmers and investors” (NGO supervisor, 1.3.2019). The NGOs also support the farmers by securing their land rights and access to water through negotiating with local and national authorities and supporting farmers’ organisations in many of the administrative procedures. Nevertheless, in both cases examined, they have only partly managed to secure water access due to high pumping-fuel costs, shortages, and high maintenance costs. According to NGO technicians, this situation is due to the monopolistic position of a Canadian private company to which the State recently transferred the management of all water drills in the regions of Thies and Diourbel.

3.1.2. Organic Union Farmers

The examined farmers’ union works in the Niayes region dominated by horticultural production (onions, lettuce, aubergines, tomatoes, beans, and peppers) and has supported smallholders engaged in agroecology since 1982. From the 1990s, the union has been strongly supported by a national NGO, international donors and governmental development agencies. The union currently includes 3000 members, but only about 40 of these are engaged in an ongoing organic-certification process (NGO technical advisor, 10.10.2019). The main objective of the union is to “establish a healthy and sustainable agriculture for better food security” and “to support the population in the fight against environmental degradation” (Farmers’ Union main statute, 2019). The motivation to support agroecology in the area followed a study on the impacts of misguided pesticide use upon human health, which progressively became the most important argument for organic practices adoption among farmers [68]. For about 30 years, the union has transferred agroecological knowledge to local farmers via a farmers’ field school and later farmers-to-farmers programmes. The union has also supported farmers in certification processes and in commercialisation to preferential organic markets in Dakar with the help of the national NGO. However, these markets only absorb a small part of the production of a few farmers. Although the union presents itself as apolitical, union members have recently participated in demonstrations related to natural-resources access for smallholder farmers. In 2018, union members took part in a popular street protest against the government’s decision to construct a dozen water drills in the union’s area to supply the city of Dakar with potable water.

To ensure the recognition of agroecological practices, the union uses the organic standards defined by the National Federation of Organic Agriculture (FENAB), of which it is a founding member. These standards take the form of a written “cahier des charges”, a set of rules consisting of good agricultural practices that need to be followed in order to obtain an organic certification. Standards are enforced in the field during irregular visits by a committee composed of members of the FENAB and the local union representatives. Under all circumstances, chemical inputs are totally forbidden for organic producers on the totality of their crops. Standards exert further control of labour through the exclusion of sharecropping (called mbey seddo in the Wolof language), with the argument that the landowner is not in a position to guarantee compliance with the standards. Mbey seddo consists of giving a plot to a landless worker in exchange of a share of production [69]. This is perceived as a restriction for those smallholders who often lack the workforce on their land and wage workers (called surga in Wolof) to help them during activity peaks. Surga used to be treated as members of the family, participating in meals and sometimes receiving a piece of land and being invited to marry a woman of the village (interview with an old farmer in the village, 5.10.2019). However, these conditions appeared only in some ideal situations. More recently, various types of human and labour exploitation have been noticed between surga and their hosts (called njaatige in Wolof) [69]. It was also common for villagers to perform collective work (called santaane) to support each other during peak activity. Due to the high pressure on land and water and the commodification of labour, collective work, as well as some other forms of solidarity, have been reduced.

Besides these restrictions, farmers generally believe that work in agroecology requires more effort than in conventional farming.

Agroecology requires more effort from the point of view of pest management because it requires knowledge and particular strategies which may or may not work. For soil management there is an additional work of soil preparation.(Organic producer, male, 02-05-2019)

The work in agroecology requires more effort, especially for composting.(Organic farmer, female, 45 years, 01-05-2019)

Furthermore, raising awareness of the risks related with chemical inputs has led to a sort of culpability for farmers about the negative consequences for consumer health, as illustrated by the following quotation:

The difference is to believe in what you do. God is asking us not threatening each other. If I use pesticide and you eat it and in 30 years, 15 years or 10 years, you start having health problems, this would be my fault. God doesn’t want it.(Male farmer, 30 years, Organic union, 4.4.2019)

A further issue raised by farmers is the contradiction between their convictions in favour of agroecology, the painfulness of tasks, and the intense frustration over their products not finding sufficient preferential market niches.

Painful is also the fact of not finding a market for our product.(Organic producer, male, 02-05-2019)

Cultivation is not difficult in terms of work; when you have the means it is not hard.(Organic farmer, male, 50 years, 01-05-2019)

Most products of organic agriculture are sold side by side with conventional ones at local markets and face harsh competition with cheap crops from medium agri-business that have boomed in the area in the last 10 years, favoured by municipalities and government authorities. Furthermore, agribusinesses also compete with small farmers for water with higher pumping capacity; they leave small farmers without access to water for several hours a day, further increasing their workload. Affected small-scale farmers tend to sell their labour force to the larger agribusiness for low wages and, ultimately sell their land. In this case, control of work is channelled through the combination of unfair market mechanisms and dispossession from land and natural resources [67].

3.1.3. Community-Supported Agriculture

Our case study of CSA is a private, capital-intensive initiative of a group of French businesswomen who purchased land in the touristic and gentrified coastal area close to the capital city of Dakar. They set up a highly diversified and entirely organic horticultural farm with expensive infrastructure, including a solar-powered irrigation system. An experienced technician supervisor and expert in agroecological-farming techniques hired by the businesswomen manages the farm. The initiative also strongly engages in research and education, as the technician puts it:

We are very happy to receive young people for sharing experiences. We are not researchers, but we do engage in research, because everything we do is noted, it is calculated.(Male technician supervisor, 16.3.2019)

Besides the supervisor, production activities involve four permanent employees, interns (mostly agronomy students), and direct consumers who are often foreign expatriates based in the gentrified periphery of Dakar. The permanent workers only receive a minimum wage for their work, as the CSA farm is not yet economically viable, but they receive board and lodging during their working days.

When we are here, there is no weekend; you are here and you work.(Male technician supervisor, 16.3.2019)

Consumers, among which, many are expats, can harvest their products themselves on the farm and develop personal relationships with workers and staff members:

Here, they call us the local grocery store (…), we receive people and they come to visit and to do their market every day, with their basket, or with their craft paper we are giving to them, they harvest and we sell [the vegetables] to them (…)(Male technician supervisor, 16.3.2019)

The farm also commercialises its products at a monthly market for organic vegetables held in the village and supplies hotels in Dakar. The farm is therefore able to sell most of its products and demand exceeds supply.

The farm manager considers the engagement of the education initiative as both a source of income and as a contribution to local sustainable development. On the one hand, the initiative regularly organises field schools liable to pay costs to support the diffusion of agroecological practices to a broader audience of students, practitioners, or other interested persons. On the other hand, they have also trained a group of women from the village and provided them with access to two areas of fenced land, water, and seeds under the condition that they produce following strict organic criteria. As the manager puts it:

In the agroecological-transition process, women and young people got involved and were trained in ecological and organic farming. Only 104 women went to the end of training, after which an area of 3000 m2 and then another of 5000 m2 was lent to them. Land that is theirs as long as they keep working following our biological and agroecological standards.(Male technician, 16.3.2019)

Through these various activities the CSA initiative manages to control labour via different channels, namely the provision of land, water, and inputs, but also the control of production conditions through the strong training and education focus enhanced by the agroecological orientation of the farm.

3.1.4. Sufi Brotherhood

This case concerns a Bayefall brotherhood community located in a rural area between Touba and Louga. The Bayefall are a branch of the Mourid Islamic Sufi order and attach the utmost importance to work [70]. The spiritual chief (also called the marabout or serigne in Wolof) and his disciples, who form the Bayefall community, have started an ambitious project consisting of agroecological farming and an education programme. The project, started in 2016, consists of developing irrigated horticulture and agroforestry in an area of about 8 ha, adjacent to the community and to a pilgrimage centre also under construction. It has the objective of generating income sources for community members, transmitting knowledge and supporting food sovereignty in the region. According to the marabout, the choice of producing according to agroecological principles is justified by the fact that Bayefall “have to protect life in all its forms […] and resist the domination of industrial agriculture” (The marabout, 13.10.2019). The marabout sees the project as a way to find solutions to social and environmental problems in the country. The community is supported by a broad network of friends and associations based in Europe and the USA, with whom they have collaborated for several decades to implement development programmes in their community and in the surrounding villages. These relations give place to intense exchanges of knowledge and resources across people with different cultural backgrounds. Notwithstanding the firm intention to keep local villages independent from industrial farming and chemicals, the vocation of the community is not to advocate politically to receive support from the State. According to the marabout, the objective of the project is to “prove to the Mourid community that it is possible to produce ecologically and to progressively expand the practices within the entire brotherhood” (13.10.2019).

Though still at an early stage, the project is progressing very quickly due to the spiritual fervour of the marabout’s disciples. Disciples refer to agroecology as a mixture of ecological and humanistic values, but also as a pragmatic way to prevent outmigration from the country as advocated by many NGOs and European cooperation agencies:

For me agroecology is nobility, being in the service of humanity. If you plant a single tree, imagine the number of ants that will live there. The people who use it to heal themselves. They say ‘nourish the earth that nourishes the tree that will nourish you’. I see nothing more noble than cultivating the land. It’s the best way to find autonomy. I appeal to young immigrants who take canoes and who think there are silver trees there. No, I appeal: ‘Go back to earth! It’s the only way to be independent’.(Bayefall disciple working in agroecology, 29 years, 7.11.2019)

The Bayefall workers are not paid financially for their contribution, but receive spiritual recognition and guidance from the marabout. Following the teachings of Cheikh Amadou Bamba and Maam Cheikh Ibrahima Fall, the two founders of the brotherhood, the Bayefall believe that working for the community without expecting financial compensation is sanctifying and can be considered to be a prayer. It is, thus, a way to reaffirm their sense of belonging to the community and to the vast lineage of the brotherhood’s founders [70,71]. The disciple community includes young men but also families from Dakar, nearby towns and a few Europeans who share spiritual and moral values and participate in the collective working activities. Most members of the community declared allegiance to the charismatic and open-minded marabout, who is himself a disciple of a higher-ranking marabout of the brotherhood, and follow all his ndigel (the Wolof word for spiritual orders) without contesting them and thereby develops humility and trust.

If the spiritual chief tells me go to France to take agricultural training, I will go without thinking, as it is the allegiance pact […] you will do whatever you are asked to do and you will leave what you are asked to leave. You have no reason to have your own project.(Bayefall disciple working in agroecology, 30 years, 15.10.2019)

Interviewees insisted on their willingness to leave their past mundane life and dedicate themselves to spiritual elevation through complete abandonment to their spiritual guides.

I started to change, to love something other than what I liked before and to do ‘zirkh’ [religious singing]. When I did, it came inside and I couldn’t stop. There, I saw that the prayers that I made before were raised and I started to feel the light in me and when I am in these states and that I am listening to music that I used to like, it makes me feel nothing. That feeling of love for the mundane world started to come out of me and I knew it was my place. Senebi [name given to the marabout] kept me waiting by telling me that Cheikh Ibrahima Fall [one of the highest spiritual guides in Senegal], those who know how to wait for him will see him coming.(Bayefall disciple working in agroecology, 30 years, 15.10.2019)

This view is reflected in the decision-making process and productive operation, which are almost completely centralised by the marabout, who makes decisions in consultation with his “right arms”, close family and advisors. During working activities, the disciples are supervised by the jawriñ, who are representatives recruited by the marabout on the basis of a degree of trust, and their experience in a given field and spiritual criteria. In the community, there is not much money in circulation and the resources are directly managed by the marabout, who purchases and distributes food, medicine, and other essential goods. The marabout is also the representative of the community with all external social and political entities and he is the one who holds customary and formal access rights to land and natural resources.

4. Discussion

Agroecology has been welcomed with great enthusiasm in sub-Saharan Africa by many organisations belonging to international-development-cooperation networks. A challenge for many of these organisations is to demonstrate the ecological, social, and economic efficiency of their approach in view of gaining legitimacy in the social field of agroecology in Senegal and in sub-Saharan Africa. This stake has been the main focus of most agroecological initiatives flourishing in the region. To reach this objective, many organisations have adopted a somewhat paternalistic and directive approach to support small-scale farmers. Following the approach of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu [32], in this paper, we looked at agroecological farms not only as a fabric of vegetables and other crops, but as a social field within which multiple financial, social, ecological, cognitive (or cultural), and symbolic capitals are structuring power relations. Following this approach, labour control is rarely unidirectional, but takes the form of a complex bundle of power and reciprocal exchanges. Our empirical observations of four different types of agroecological initiatives clearly show that these initiatives are not led by farm workers themselves and therefore tend to limit their potential for emancipation and autonomy. In some cases, the additional workload required to implement agroecological practices is either transferred to the most vulnerable groups or leads to further commodification of work through precarious employment [11,21,22,24,25]. Some of these initiatives, in particular the NGO-supported ones and the CSA, involve top-down transfer of knowledge, technology, and decisions, and are still at the pilot and experimental stage, with much financial and technical dependence on external organisations. This does not mean that labour conditions are more or less painful than in conventional farming, but that power relations in agroecological initiatives are structured around different types of values and channels and therefore lead to different mechanisms of labour control than conventional agriculture [28,56].

Our argument is that agroecological farming in Senegal does not necessarily result in a situation of better working conditions and greater working autonomy for small-scale farmers [6,9], but rather leads to alternative channels of labour control and paternalist approaches. In particular, we conclude that agroecological initiatives: (1) are mostly dependent on international-cooperation funding in a context of inequitable market liberalisation and chemical-input subsidisation; (2) enforce uncoordinated and specific quality standards and a “cahier des charges”, leading to increased local labour control; (3) do not really solve the central problem of farmers’ unequal access to land, natural resources and productive assets; (4) are established through top-down knowledge transfers; (5) lead to farmers’ incorporating new exogenous or hybrid ontological values defining what “good farming” is [34]; and (6) contribute to reinforcing the symbolic power of the dominant actors belonging to the international-development-cooperation network rather than farmers’ organisations.

Coming back to the first point, the dependence on international-cooperation funding can be explained by the current context of agriculture liberalisation, chemical-input subsidisation, and the lack of a preferential market for agroecological products. In this context, financial flows of agroecological initiatives are rarely generated by local, national, or international markets due to the unfair conditions of concurrence with conventional products and the current institutional weaknesses of the certification schemes. Financial resources therefore mainly come from donors based in Western countries who seek to mitigate the consequences of climate change or, more recently, as a strategy to reduce irregular migration from sub-Saharan Africa [72]. As for most NGOs and international-cooperation programmes, the functioning and administrative costs critical for their own maintenance also rely upon external funds [73]. This partly explains the critical dependence on these organisations by the initiatives they are supporting and also explains the pressure that some NGOs’ technicians can exert on farm workers to show appealing results.

Second, organic-certification norms and NGOs’ cahier des charges signed with the supported farmers are progressively being established as alternative and direct channel of labour control. Both types of standards lead to additional workloads that can, in some circumstances, be transferred to the most vulnerable groups of people such as women, landless people, and youths [24,25]. They can also lead to further commodification of labour, increased reliance on wage working, and additional financial pressures on small-holders due to the restrictions on sharecropping enforced by the organic union’s standards. This type of pressure might be mitigated by participatory systems of guarantee (PSG), although for the moment in Senegal, these types of certification are still at an early stage of development and do not have a clear orientation. Moreover, PSG initiatives still lack popularity among the mass of Senegalese consumers to offer sufficient market alternatives in a context of liberalisation of the agrarian sector [52].

Third, access to land, water, and productive assets also plays an important role in shaping farmers’ working autonomy and conditions. This problem is particularly important in the case of counter-seasonal horticulture production requiring large quantities of water, and therefore consequent labour inputs and high infrastructure investments. The control of irrigation infrastructure is therefore a direct instrument of labour control in Senegalese horticulture. In all the visited agroecological initiatives, supporting actors stated their clear intention to facilitate local appropriation of productive assets. Nevertheless, this appropriation is hindered by national policies that encourage the privatisation of these resources in favour of large companies and investors. The situation has been exacerbated since 2018, when the central government decided to transfer the management of all the water drills in the regions of Thies and Diourbel to a Canadian private company. Since then, many communities have complained about the high cost of maintenance and the damaging consequences of the delay in fuel provision and repair upon the loss of production. Local and autonomous management of productive assets by local organisations is a precondition of empowerment and resilience.

Fourth, our cases also confirm the existence of power asymmetries and labour control through the channels of legitimated knowledge, playing a crucial role in agricultural-innovation processes [34,38,40,41,74]. Agroecology started in Senegal following increasing awareness of the impact of chemical inputs upon farmers’ health and fragile ecosystems. This awareness mainly concerns areas of horticultural development, which is a recent innovation in Senegal starting in the 1950s in the Niayes region [68,69]. It is, thus, not surprising that agroecology is considered by most of the interviewed farmers to be a “nassaran” word (a foreign concept) that has emerged with the growing presence of environmental NGOs in the field of horticulture. This link between agroecology and irrigated horticulture development places farmers as “beneficiaries” of technical innovations rather than agents of socio-ecological transformations and hinders knowledge co-production, which is a central aspect of contributive and cognitive justice [10,38].

Fifth, to facilitate farmers’ adoption, agroecology is associated with a set of cultural values justifying the change in technologies as well as the additional workload. Farmers’ incorporation of these values into their habitus [34] is established through everyday practices, sensitisation (e.g., farmer field school), and the symbolic power of the organisation making its promotion at the national scale. As we have seen in our cases, the visited initiatives are all mostly “experimental” in the sense that the social-learning experience counts for more than any other benefit from production itself. Through their work effort, farmers participate in the self-fulfilling prophecy of agroecology. The product of their work generates more added value when it ends up in pamphlets’ pictures or in manuals of good practices than in Dakar’s vegetable markets. This allows those who support these initiatives and feature them in conferences and in the media to increase their symbolic power. Farm workers are to some extent demonstrators of a new way to produce food, and for this reason remain highly conditioned by their promotors.

Sixth, cultural values and symbolic power are strong drivers of workers’ obedience or even submission to labour-control mechanisms, as the case of the Sufi brotherhood shows. In Senegal, as in other African societies, cultural patterns, social ties, and interpersonal values can have a rather stronger influence than market channels, legal standards, and financial exchanges in labour relationships [71,75,76,77,78]. The spiritual value of work is combined with the virtues of frugality and sufficiency that are already popular in European agroecological movements [79,80]. In the case of Bayefall communities, individual labour autonomy is not even foreseen as an aim according to their own cultural values. What mobilises individual action during work is, to the contrary, the total abandonment of the individual to the spiritual chiefs’ agency with the confidence that he will guide the group towards spiritual achievement. Some would see this as a form of top-down labour control and asymmetry of power. In our sense however, we see it as a local appropriation of agroecological principles according to local ontological and cultural values, which is a precondition for a larger process of transformation. Neither NGO supervision nor certification mechanisms are clearly democratic and may contribute to increasing the symbolic power of already powerful stakeholders.

Finally, relational channels play a fundamental role during dynamic interactions between small group of people with strong interpersonal links [45,46]. In all observed cases, part of labour control is established through direct social interactions facilitated by small-scale projects. For vulnerable farmers, joining an initiative is an excellent way to build social capital and develop solidarity and resilience mechanisms in case of needs. The relational approach of farming also teaches us that farmers are never completely subject to coercive structural pressures, but always generate strategies and agency to overcome mechanisms of control [45,46]. Farmers’ participation in agroecological initiatives can be seen as a process of exchange with external stakeholders in view of generating mutual benefits. Despite agroecological initiatives not clearly leading to enhanced farmer autonomy, they can increase the cultural and social capitals of the participants.

Engagement in favour of agroecology is also a rationale for advocacy due to some strong messages and values defended, such as environmental stewardship, food sovereignty, and the emancipation of small-scale farmers from land and resource grabbing [67]. For the farmers’ union as well as for some local authorities in the country, agroecology has started to become an ideological support to gain political legitimacy and negotiation power against other competing actors. These are crucial issues. Farmer support should not be limited to “islands of success” at the farm level, but should go beyond the plot and reach local, regional, and national political spaces [31]. In our view, the main barrier to small-scale agroecological farmers’ emancipation is given by the limited coherence of national and international agrarian policies and the reluctance to include social-justice issues in the negotiations around agroecological transitions [31,81]. Farmers’ working conditions are being undermined by the subsidisation of chemical fertilisers with the help of international lobbies [82], privatisation and dispossession of underground water, privilege accorded to agribusiness detrimental to small-scale farmers, priority given to extractive-industry development in highly productive agricultural areas without real impact assessment and mitigation measures, and extensive and disorganised urbanisation and a lack of clear land security.

To face these challenges, small-scale pilot projects such as the ones we assessed in this paper are the first steps toward supporting the technical development of agroecology at the farm level. Nevertheless, such projects remain insufficient to find solutions to the structural problems mentioned above. The limited negotiation and advocacy capacity of most organisations supporting agroecology is rooted in the strong implication of foreign donors and NGOs that lack political legitimacy at the national level. Foreign donors and NGOs contribute to building small niches of (technical) change, but their capacity to foster the self-determination of farmer organisations is limited. According to organic farmers, the prerequisites for an agroecological transition would be clear government support when it comes to securing equitable access to land and water, protection of preferential market space for organic products, nation-wide technical and logistical support for organic-input provision and development of certification systems, and a fair-value chain. Recent attempts to coalesce advocacy around the Reflexion Group on Land in Senegal (CRAFS) in 2010 and the DyTAES in 2019 seem promising initiatives [66] that will need further assessment.

5. Conclusions

Our approach has shed light upon unrevealed mechanisms of labour control and alerted against the potential unexpected negative social impacts of agroecological initiatives. We hope that in the coming years, programmes aiming at promoting and implementing agroecology in sub-Saharan Africa will continue to grow to address the negative consequences of climate change and respond to the challenges of food-system sustainability. Nevertheless, the women and men playing the most important role in food systems need further recognition and protection. In particular, agricultural workers from the Global South and especially from Africa have remained neglected by scientific and policy interest in recent years [83]. The concept of work itself is usually addressed through neo-classical economic approaches and lacks broader conceptualisation in view of responding to the needs of social-ecological transitions [84]. Researchers and policy makers should remain aware that incomes, food production, and livelihoods all depend upon complex labour processes and work efforts embodied in particular and culturally determined modes of production and human relations. Agroecological-transition processes should therefore also be considered from the political and economic perspective of a “just transition”, whereby work is not limited to an economic input but is a fundamental human activity aiming at generating people’s feelings of self-accomplishment, creativity, and emancipation [29]. To support these principles, farmers and farm workers in sub-Saharan Africa cannot remain closed into what have been called “islands of success” in reference to NGOs’ highly controlled pilot farms. A (re)appropriation of agroecological principles by locally legitimised farmers’ organisations and their extension at broader territorial levels are preconditions for an out-scaling process. In the views of many of the stakeholders consulted, there is an urgent need to support farmers’ appropriation of agroecological principles according to locally and culturally adapted ontological values and power structures. This core principle should be accompanied by rescaling agroecological initiatives at territorial and national levels to implement a more holistic approach that includes institutionalisation of protected markets for agroecological products, farmers’ inclusiveness in the governance of the commons such as land, water, and other natural resources, and clear support for co-production of knowledge and their links to locally accepted and constructed ontological values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: P.B. and S.B.; Field work and comments on draft versions: P.B., S.B., F.M. and S.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research (SNSF), AgroWork project grant number 176736.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nithya Natarajan and Laurie Parsons for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, D.; Nizet, J.; Streith, M.; Stassart, P. Agroécologie: Entre pratiques et Sciences Sociales; Educagri: Dijon, France, 2012; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Dioré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P.M.; Martínez-Torres, M.E. Rural social movements and agroecology: Context, theory, and process. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The New Peasantries: Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in latin america: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabhi, P. La Sobriété Heureuse; Actes Sud: Arles, France, 2010; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel, L.E. Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann, C.; Felix, G.F. Agroecology as a vehicle for contributive justice. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O. Designing agroecological transitions: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1237–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, A.S.; Rusinamhodzi, L. Yield and labor relations of sustainable intensification options for smallholder farmers in sub-saharan africa. A meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana, P.D.; Andrieu, N.; Zerbo, I.; Ouedraogo, Y.; Le Gal, P.Y. Conservation agriculture and performance of farms in west africa. Cah. Agric. 2015, 24, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, S.P. Human resources and sustainable agriculture: A case study from central himalaya. J. Sustain. Agric. 1997, 10, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K. Labour, livelihoods and the quality of life in organic agriculture in europe. Biol. Agric. Horticult. 2000, 17, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, N. Do organic farmers feel happier than conventional ones? An exploratory analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 103, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Mogyorody, V. Organic farming, gender, and the labor process. Rural Soc. 2007, 72, 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, A.M.; Baret, P.V. Why working conditions are a key issue of sustainability in agriculture? A comparison between agroecological, organic and conventional vegetable systems. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 56, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E. The moral economy is a double-edged sword: Explaining farmers’ earnings and self-exploitation in community-supported agriculture. Econ. Geogr. 2013, 89, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupre, L.; Lamine, C.; Navarrete, M. Short food supply chains, long working days: Active work and the construction of professional satisfaction in french diversified organic market gardening. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousseau, F. The untold success story of agroecology in africa. Development 2015, 58, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugwanya, N. Why agroecology is a dead end for africa. Outlook Agric. 2019, 48, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Witter, E.; Corbeels, M.; Tittonell, P. Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in africa: The heretics’ view. Field Crops Res. 2009, 114, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P.; Scopel, E.; Andrieu, N.; Posthumus, H.; Mapfumo, P.; Corbeels, M.; van Halsema, G.E.; Lahmar, R.; Lugandu, S.; Rakotoarisoa, J.; et al. Agroecology-based aggradation-conservation agriculture (abaco): Targeting innovations to combat soil degradation and food insecurity in semi-arid africa. Field Crops Res. 2012, 132, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Hickey, C.; Lupafya, E.; Dakishoni, L. Repairing rifts or reproducing inequalities? Agroecology, food sovereignty, and gender justice in malawi. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 1499–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Martin, A.; Kristjanson, P.; Wollenberg, E. Implications on equity in agricultural carbon market projects: A gendered analysis of access, decision making, and outcomes. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 2080–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E. Local labour control regimes: Uneven development and the social regulation of production. Reg. Stud. 1996, 30, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattenden, J. Working at the margins of global production networks: Local labour control regimes and rural-based labourers in south india. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 1809–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, E. Labour control and the labour question in global production networks: Exploitation and disciplining in senegalese export horticulture. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 18, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Mulvaney, D. The political economy of the ‘just transition’. Geogr. J. 2013, 179, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C.; Schaefer, F.; Skalidou, D. The effectiveness of agricultural certification in developing countries: A systematic review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isgren, E.; Ness, B. Agroecology to promote just sustainability transitions: Analysis of a civil society network in the rwenzori region, western uganda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambrige, UK, 1977; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Darnhofer, I. Of organic farmers and ‘good farmers’: Changing habitus in rural england. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley-Murray, J. Value and capital in bourdieu and marx. In Pierre Bourdieu: Fieldwork in Culture; Brown, N., Szeman, I., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publisher: London, UK; Boulder, CO, USA; New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Raynolds, L.T. Fairtrade, certification, and labor: Global and local tensions in improving conditions for agricultural workers. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolsaet, B. Towards an agroecology of knowledges: Recognition, cognitive justice and farmers’ autonomy in france. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, N. Farmers adoption of integrated crop protection and organic farming: Do moral and social concerns matter? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquil, X.; Cerf, M.; Auricoste, C.; Joannon, A.; Barcellini, F.; Cayre, P.; Chizallet, M.; Dedieu, B.; Hostiou, N.; Hellec, F. Questioning the work of farmers, advisors, teachers and researchers in agro-ecological transition. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquil, X.; Dedieu, B.; Beguin, P. Professional transitions towards sustainable farming systems: The development of farmers’ professional worlds. Work 2017, 57, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T.; Banks, J. Quality, nature, and embeddedness: Some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector*. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 76, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, N.; Rosset, P.M.; Salazar, T.C.; Moreno, A.S.; Morales, H. Mediated territoriality: Rural workers and the efforts to scale out agroecology in nicaragua. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicott, J.B. Agroecology in context. J. Agric. Ethics 1988, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Farming from a process-relational perspective: Making openings for change visible. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Lamine, C.; Strauss, A.; Navarrete, M. The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.; Tilly, C. Inequality and labor processes. In Handbook of Sociology; Smelser, N.J., Ed.; SAGE: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 175–221. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Final Report of the Regional Meeting on Agroecology in Sub-Saharan Africa; FAO: Dakar, Senegal, 2016; Available online: http://www.fao.org/publications/card/zh/c/ad55359b-3bce-4e26-92bc-216bf1c78fa9/ (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Diop, A.M. Sénégal: Dynamiques Paysannes et Souveraineté Alimentaire-le Procès de Production, la Tenue Foncère et la Naissance d’un Mouvement Paysan; Harmattan Sénégal: Sicap karak, Senegal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duruflé, G. Bilan de la nouvelle politique agricole au sénégal. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 1995, 22, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C.; Ba, C.O. Les Politiques Agricoles 2000–2012: Entre Volontarisme et Incohérence; SOAS: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, J. Land grabs, government, peasant and civil society activism in the senegal river valley. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2012, 39, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAER. Programme D’accélération de la Cadence de L’agriculture Sénégalaise (Pracas); Ministère de L’Agriculture et du Développement Rural, Ed.; IPAR: Parap, NT, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, L. L’accaparement des terres, une menace pour lamise à l’échelle de l’agroécologie au sénégal. Agripade 2018, 26–31. Available online: http://www.iedafrique.org/IMG/pdf/agridape_numero_special_fm-fr.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Perry, D.L. Wolof women, economic liberalization and the crisis of masculinity in rural senegal. Ethnology 2005, 44, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, E. Straddling contract and estate farming: Accumulation strategies of senegalese horticultural exporters. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C. Stories of rural accumulation in africa: Trajectories and transitions among rural capitalists in senegal. J. Agrar. Chang. 2007, 7, 453–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copans, J.; Couty, P.; Roch, J.; Rocheteau, G. Maintenance Sociale et Changement Économique au Sénégal; ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hrabanski, M. Internal dynamics, the state, and recourse to external aid: Towards a historical sociology of the peasant movement in senegal since the 1960s. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2010, 37, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, A.M. How can organic farming and agro-ecology contribute? In Africa Can Feed Itself; Naerstad, A., Ed.; AiT: Oslo, Norway, 2007; p. 229. [Google Scholar]