Abstract

The paper aims to explore the process of land conversion for tourism development in Vietnam, under the present ambiguous and insecure property rights system. Four case studies in different geographical areas were selected to analyse land conversion and land compensation for tourism projects before and after the implementation of the new land law in 2013. The findings of this study show that, in the present legal system of land and property rights, the rights of local people are not sufficiently guaranteed due to the decisive role of the State not only in defining compensation prices for land in the case of compulsory land acquisition but also in determining whether tourism projects are in the public’s interest or not (thus deciding the appropriate land conversion approach as well as affecting price negotiations). The research also found that, although a voluntary land conversion approach (when the project is not in the public’s interest), based on the 2013 Land Law, offers land users a better negotiation position and a higher compensation payment, possibly reducing land-related conflicts between the State and land users, ambiguity over property rights in fact increased due to the government’s substantial discretion to choose between ‘public purpose’ and ‘economic purpose.’ The paper concludes with questioning whether the present legal basis for compulsory land acquisition is future proof since urbanisation pressure is likely to increase, which may lead to even more land conflicts in the near future.

1. Introduction

As land is a crucial factor for tourism development, the rapid development of this sector has evidently led to an increase in the demand for land [1]. However, that land is often used already by other sectors such as agriculture. For this reason, land acquisition to accommodate the demands for land for tourism often affects various other land users.

Concerning land development, Vietnam is still in the process of adjusting its property rights regime, as part of the broader transition of its economy. Particularly since the introduction of the new land law in 2013, land users have obtained more secure rights over land [2]. However, land in Vietnam is still owned by the State as the representation of the people. Hence, the changes in the legal framework for land conversion have increased the complexity for stakeholders involved in the process.

While many studies have analysed the issue of (agricultural) land conversion for urban development [3,4,5,6], in this paper, we aim to investigate the land conversion process for tourism accommodation development before and after the implementation of the 2013 Land Law and the influence of the ambiguous property rights over land on the land acquisition process in Vietnam. As we will argue below, due to the changes in the 2013 Land Law, these tourism investments may lead to even more conflict because of the potential dispute over public versus private interest projects and the impact on land acquisition. We refer to Mangione [7] to discuss the legal issues and academic debate related to the unclear distinction between public and private interest projects in the case of the expropriation of properties. The present study aimed to add empirical evidence to that debate. Four case studies in different geographical areas were selected to observe how the land was acquired for tourism projects and how affected people were compensated, respectively, before and after the implementation of the 2013 Land Law.

In-depth interviews with relevant stakeholders in the land conversion process were conducted to understand the position of locally affected people and developers’ perspectives on current land conversion mechanisms and compensation issues. Besides, additional data were collected from academic articles, interviews with experts and official government representatives, laws, regulations and documents related to land issues and tourism.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of tourism development in Vietnam. Particularly, it pays attention to the increasing demand for land for tourism in Vietnam over the past years. Section 3 contains a literature review related to property rights over land and land conversion issues in some transitional countries including Vietnam. It focuses on international literature that discusses the (legal) motivation for the expropriation of land. In Section 4, data collection, methodology, and case studies are provided to observe practical applications of Vietnam’s land conversion legal framework. The findings of the study are provided in Section 5, followed by discussion in Section 6. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section 7.

2. Tourism Development in Vietnam in Brief

Tourism in Vietnam is expanding rapidly and increasingly plays a significant role in Vietnam’s economic development [8,9,10], because of its substantial contribution to the national economy, job creation, and income generation for local communities [11,12].

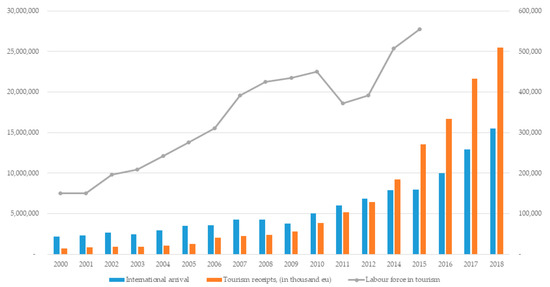

Figure 1 presents the major achievements of the tourism sector in Vietnam over more than a decade. For instance, the number of incoming international tourists in Vietnam dramatically increased from more than 2 million in 2000 up to 15.5 million in 2018. This figure is far above the 2020’s objective stated in Vietnam’s tourism development strategy until 2030 [11,13]. The growth in the number of tourists significantly contributed to the increase in the industry’s receipt in the same period. As shown in Figure 1, tourism receipt has brought about €25.48 billion in 2018. The direct contribution of the tourism sector to the GDP of Vietnam has increased from 6.33% in 2015 to about 8.39% in 2018 [11,14]. In terms of job creation, Figure 1 shows that the tourism sector has created more and more jobs over the years. Employment in this sector concentrates in the field of accommodation services, food, and beverage services [13].

Figure 1.

Vietnam Tourism Development: Some key indicators. Source: Data was adapted based on Vietnam National Administration of Tourism (VNAT)’s reports [11,15,16,17].

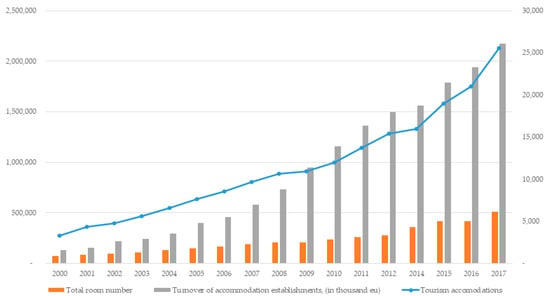

Along with this tourism growth, the number of tourism accommodations and turnover generated from them have also significantly increased over the past years (Figure 2). Revenue of accommodation establishments has grown from €130.74 million in 2000 to €2.175 million in 2017. Obviously, Vietnam’s tourism accommodation sector has been recognized in recent years as a potentially very attractive sector in the eyes of investors.

Figure 2.

The growth of tourist accommodations in Vietnam from 2000 to 2017. Source: Data was adapted based on Vietnam National Administration of Tourism (VNAT)’s reports [11,15,16,17] and General Statistics Office of Vietnam.

Different investment strategies are applied by foreign and domestic investors to develop new hotels in Vietnam. While foreign investors are seeking investment opportunities by operating hotel assets with in-place cash flow, most domestic investors want to develop hotels and resorts from scratch on, on vacant land. As a consequence, investment in the construction of new hotels has significantly increased [18]. However, problems related to the current property rights regime over land and the land conversion system in Vietnam have led to difficulties for the tourism development industry to obtain land.

3. Land and Property Development in Transitional Economies

3.1. Land Conversion in Transitional Countries

According to Alchian and Demsetz [19], property rights can be defined by how a resource can be used based on its owner’s decision. With regard to land resources, in developing countries, many efforts have been made to formalize property rights into private ownership [20] based on the argument that secure individual property rights over land may reduce the risk of expropriation by the State [21]. Moreover, land privatization can improve local people’s livelihood opportunities as well as promote the development of the local economy [22]. However, in transitional countries such as China, Cambodia, and Vietnam, the land privatization process has not been fully implemented: the ownership over land remains with the State, while user rights are transferred to individual users. Moreover, the land conversion process is still strongly controlled by the State and influenced by the mechanisms that the State applies to acquire the land use rights [4]. Due to consecutive adjustments to the laws regulating the land conversion process—typical for transitional economies—ambiguities remain with regard to the property rights regime.

In China, where the State owns all urban land and rural economic collectives own agricultural land, large amounts of farmland are acquired and converted for urban use by the intervention of local governments [23]. Related to the process of rapid urbanization, the development of the tourism sector also led to massive land acquisition in China [1]. Although the projects are believed to support regional economic growth and improve the people’s welfare, the number of landless peasants and social conflicts increase as the State keeps its decisive role in how land is allocated, used and also priced for compensation [4,23,24].

Cambodia is another example of a transitional economy where about 80% of the land is owned by the State, and the land reform was implemented with a focus on the formalization of property [20]. The introduction of the 2001 Land Law in the country recognizes private ownership rights for residential and agricultural land and collective ownership of land for indigenous communities [25]. Nevertheless, the central government has a right to grant concessions for socioeconomic purposes without consulting regional or local administrations [20,25]. The establishment of Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) has adverse impacts on the livelihood of the local population, on the environment, and particularly it has facilitated the phenomenon of land grabbing [26]. In 2004, a tourism project known as the Golden Silver Golf Resort—an investment by Chinese companies in the coastal region of Cambodia—converted 3300 hectares of Ream National Park into golf courses and operated under the Economic Land Concession scheme. Locally affected people were evicted from their land in 2007 without proper compensation [27].

3.2. Property Rights Regime over Land in Vietnam’s Transitional Period

In Vietnam, the economic reform known as Doi moi, initiated in 1986 and in fact still continuing, has evidently affected property right regimes over land in the country [28]. Since this reform, four consecutive land laws have been issued in which an individual or private organisation’s right to use the land has improved [2,29], while the ownership of the land and the right to manage the land remains with the State as the representative of all citizens (see Table 1). This idea was reconfirmed in Article 4 of the newest land law in 2013 as: “Land belongs to the entire people with the State acting as the owner’s representative and uniformly managing the land. The State shall hand over land use rights to land users in accordance with this Law.” It means that the State is the sole owner and administrator of the land in Vietnam [2]. Full private ownership of land still does not exist in Vietnam, even though the Vietnamese government is striving for the land privatization process [30]. This situation has created an ambiguous and uncertain regime of property rights over land in the country [4,30].

Table 1.

Vietnam’s land use rights, from the 1987 Land Law to the 2013 Land Law.

3.3. Recent Debates on the Land Conversion Process in Vietnam

Although the transition of property rights regime over land in Vietnam has gradually given more rights to land users, still some issues and debates remain concerning land conversion due to urbanisation and tourism development in the country. Several authors have analysed the consequences of compulsory land acquisition to acquire agricultural land for industrialization and urban development [31], concerning social dissatisfaction regarding unequal benefits sharing [3,4], the disrupted livelihood of a large number of people and loss of jobs of households and individuals [5,32,33]. Tuyen and Huong [34] showed that, along with the loss of farmland, many affected households had to change their livelihoods to nonfarm activities.

3.3.1. Land Conversion for Urbanization and Industrialization: Causes and Consequences

Basically, Vietnam is still an agricultural-based economy. However, as argued by several scholars, Vietnam’s economy is in the process of the transformation from agricultural to industrial, which would shift agricultural land to nonagricultural land in the near future [5,31,35,36,37,38,39].

Moreover, based on Decision No. 445 /QD-TTg on approving modification of the master plan for development of Vietnam’s urban system by 2025 with vision to 2050, dated 7 April 2009, the demand for urban land is expected to increase from 335,000 ha in 2015 to 450,000 ha by 2050 to meet the expected growth of urban population nationwide from 35 million to 52 million. As a consequence of the rising demand for urban land, particularly in the case of big cities such as Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh, many farmlands have been converted to non-agricultural activities [40]. Based on Hanoi’s land use plan for the period 2000–2010, 11,000 hectares of cropland were planned to be converted annually to accommodate 1736 industrial- and urban-development-related projects [5].

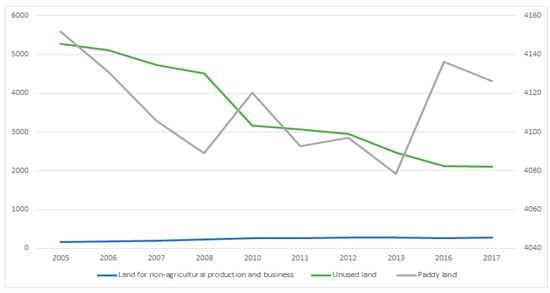

At the national level, the conversion of agricultural land to non-agricultural land has decreased the land for paddy field areas, as shown in Figure 3. This observation is quite consistent with Vo et al. (2018), who reported that, from 2010 to 2014, paddy land areas in 32 provinces of Vietnam have significantly decreased due to the acquisition and conversions of agricultural land for urban developments or other non-agricultural developments. After 2013, the area for paddy land increased again. Although strong empirical evidence is lacking, we believe that this might be partly due to the fact that developers faced greater challenges in negotiations with farmers to acquire agricultural land (see Section 3.4).

Figure 3.

Land use change classified by the purpose of land use in Vietnam 2006–2017; source: Vietnam’s Statistic Yearbook from 2006 to 2018.

3.3.2. Tourism Development: A New Driver for Vietnam’s Land Conversion

Land plays an extremely important role in tourism investment projects in Vietnam. Various studies indicate that large amounts of land have been acquired and converted for the uses of tourism investment projects such as hotels, resorts, or golf courses development, often leading to conflict and social unrest [38,39,41]. As an example, the acquisition of circa a thousand hectares of paddy field in Kim No village on the outskirts of Hanoi for golf courses development has resulted in violence between farmers and developers [42]. Another example is the development of the EcoPark Satellite City Project in Hung Yen province in 2004, consisting of a large residential zone with luxury facilities including a golf course, hotels and restaurants. It covered 500 ha of land and affected more than 4000 households. Up till now, the land acquisition process for this project can be considered as one of the most severe land conflicts in Vietnam, particularly because of the limited compensation paid to the holders of the original land use rights [43]. In recent years, the rapid development of hotels and resorts along the coastline of provinces such as Da Nang, Quang Nam, Khanh Hoa, Binh Thuan has also created conflict with local people [44]. For instance, in the Danang tourist city, the construction of the Lancaster Nam O Resort has blocked fishermen’s access to the beach because of the construction of 2 km-long fences and barriers, to the dismay of the local people [45].

3.4. Two Methods of Land Conversion in Vietnam: Compulsory versus Voluntary

As a result of the introduction of the 2013 Land Law, changes took place in the regulation with regard to the conversion of land. Currently, there are two approaches to land conversion in Vietnam. One is the compulsory land conversion by which land is acquired by the State, and the second one is voluntary land conversion, whereby land is transferred from current land users to land developers voluntarily. The 2013 Land Law regulates that compulsory land conversion can only be used for projects that are in the national or public interest, as distinguished from projects that primarily have a private, economic interest. Land conversion for the latter projects can only be based on voluntary negotiations (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Legal framework for land acquisition in Vietnam from 1987 to 2013.

3.4.1. Compulsory Land Acquisition

Compulsory land acquisition is the power of the government to acquire private rights on land to the benefit of society without the willing consent of its owner or occupant [46]. In Vietnam, despite the significant reforms in land conversion regulations since 1993 till now, the issues related to the scope of application and the state-determined land price for compensation in the compulsory land acquisition mechanism remain controversial. Consequently, it often generates social conflicts around the country [47].

Based on the 1993 Land Law, compulsory land acquisition can be used to provide land for projects related to national defence, security, or other national or public interests [30]. In 1998, the government issued Decree No. 22/1998/ND-CP to stipulate that the national interest could include activities for economic development such as commerce, entertainment, and tourism. Later on, Decree No. 181/2004/NQ-CP stipulated that those national-interest projects can be financed by 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and hence the compulsory land acquisition mechanism can be applied to accommodate such projects as well. Decree No. 87/2007/ND-CP added that the State can also acquire land to develop high-class hotels in tourism areas.

Obviously, the unclear differences between public investment purposes and private investment purposes may cause many social conflicts, because it favours the position of private investors [4,30]. In order to reduce the tension between local communities and the government regarding this issue, the 2013 Land Law was introduced. In this law, land acquisition by the State can only be conducted to accommodate national or public interests which include national defence, security, and socioeconomic development. Compulsory land acquisition cannot be implemented anymore to accommodate economic projects by private investors. The public interests should be included in the land use plan, and then a land acquisition plan should be issued by the government. The affected people must be notified about the plan before an investigation, survey, and measurements to implement the plan are carried out, including the amount of compensation to be paid, support and a resettlement plan for the affected people (see Figure 4). Although the law already stipulates that compulsory land acquisition can only be implemented to accommodate projects that are considered as public purpose and interests, in practice until now, there remains a dispute over how to define the public purpose and interest [48].

Figure 4.

Procedures for compulsory land acquisition. Source: 2013 Land Law, Article 69.

The compensation price is another source of conflict in land acquisition since the State still keeps a decisive role in determining the size of the compensation [47,49]. Large differences between the price set by the State and the market value for the land has led to conflicts over land acquisition in the country [29,50]. To deal with this problem, the Vietnamese national government has changed several times the regulation on how to determine the compensation price when a public authority is involved in a land acquisition process. Based on the 2003 Land Law, when the State applies a compulsory land acquisition, the original land user should be compensated with the price that is ‘close to the actual market price’ (Article 56.1, 2003 Land Law). Decree No. 197/2004/ND-CP further explains that the compensation should cover not only the loss of the land but also the investment that has been made by the original land user as long as that investment has not been covered by the gained benefit from it. The latter is called the remaining land-related investment. In the latest land law introduced in 2013, it is stipulated that a professional consultant should be involved as a third party to determine the value of the land when there is a large difference between the price set by the State and the market price [47]. Nevertheless, the State continues to have considerable power over compensation prices and the concept of ‘close to the actual market price’ remains very ambiguous. As a consequence, insufficient compensation for affected communities and significant gaps between the land price set by the State and land price in the market still lead to community dissatisfaction and conflicts over land acquisition [4,50].

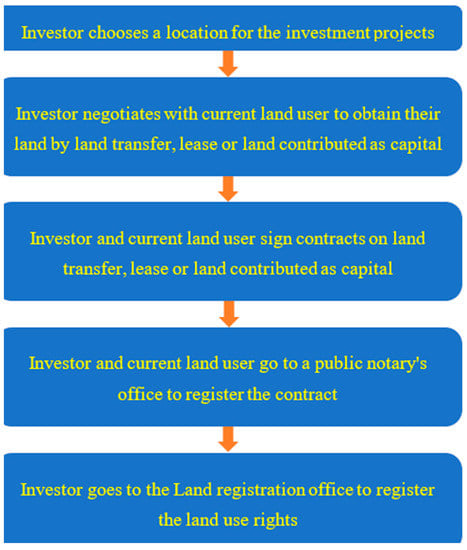

3.4.2. Voluntary Land Conversion

The 2003 Land Law introduced a self-negotiation mechanism in land acquisition processes [51]. According to this mechanism, investors directly negotiate with the current land users without the intervention of government, to acquire land for a development project (see Figure 5). Arguably, this mechanism creates some advantages, especially for affected local communities in a land acquisition process, since they can ask for a higher price for their land than the land price that is set by the government. At the same time, since the government cannot intervene in this process, it causes development delays or leads to stalled projects due to the impact on the developer’s profits.

Figure 5.

Procedures for voluntary land conversion. Source: [51].

3.5. The “Public Purpose Rule” in Compulsory Land Acquisition

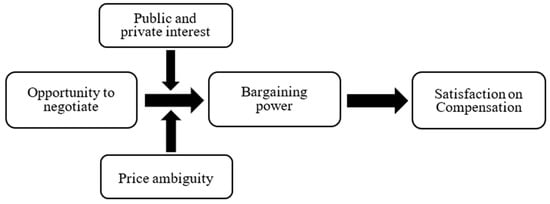

After the introduction of the 2013 Land Law, land users in Vietnam receive more rights and more protection from the State in a land acquisition process, empowering them in negotiations with developers for higher compensation and better support. In practice, however, local communities might still pull the short straw in land conversion processes, not only because of the ambiguities of a two-price system for land and the decisive role of the government in land use planning, but also because of the unclear distinction between public and private interest projects. The latter refers to a broader, international academic and legal debate on the “Public Purpose Rule” in compulsory land acquisition [7]. As Mangione [7] argues, “the literature and discussion on property tenure and the perceptions of what tenure means, leads to the fundamental question of the justification of the acquisition and more specifically the purpose to which the acquired land is intended” (p. 95). This question—that directly relates to the discussion in Vietnam how to decide on the public or private purpose of land conversion projects—has led to continuous debates in many jurisdictions. In recent years, internationally, the so-called Kelo case in the U.S. probably attracted the most attention (Kelo v. City of New London, 125 S. Ct 2655, 2005), but similar cases can be found around the world. The Kelo case resulted in the U.S. in a broadening of the uses being established for compulsory land acquisition, supporting the use of compulsory acquisition for the transfer of acquired land to private developers for urban renewal. Though a fundamental discussion of how we should deal with “public purpose” in land acquisition is beyond the objective of this paper, we argue here that one can distinguish between two opposing standpoints. The Kelo case is, to a certain extent, an example where one might say that the distinction between “public purpose” and “economic interest” with regard to the use of compulsory land acquisition is abandoned but under strict conditions. In other words, compulsory land acquisition can be used both for a public purpose and private economic interest, under strict and transparent conditions that proper compensation is paid and that safe environments are created for those that are harmed for negotiation and to object against it, if needed. The opposite standpoint is to make an explicit distinction between public purpose and private economic interest. With the 2013 Land Law, Vietnam seems to move in that direction. This paper does not offer a legal argument pro or against that decision. Instead, we aim to understand how this works out in practice. Specifically, we would like to observe, from the perspective of different stakeholders, whether the opportunity to negotiate would have an impact on the improvement of bargaining power and lead to better satisfaction on compensation for land users. We would expect that the ambiguities of a two-price system for land and the unclear distinction between public and private interest might hinder this causal relationship. This presumption would serve as our conceptual framework (Figure 6) in analysing different land acquisition cases for tourism developments in Vietnam.

Figure 6.

Conceptual framework.

4. Data Collection, Methodology, and Case Studies

4.1. Data Collection and Methodology

Data collection in this study was based on both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected from observations and interviews with locally affected people, local authorities, developers and experts during fieldworks conducted for 3 months in 2017 and 3 months in 2019. The researcher employed both face-to-face interviews and email interviews. A total of 24 interviews took place during the fieldwork, including 14 interviews with directly affected people, 4 interviews with local authorities, 3 interviews with private-sector developers, and 3 (email) interviews with experts. We interviewed both affected people whose land was successfully acquired and affected people whose land had not been acquired yet. The focuses of our interviews were on three main issues, namely, the involvement of affected people in the land acquisition process, the decision related to the amount of compensation, and the perspectives of affected people on the compensation issue. With local authority, we interviewed the offices that are responsible for acquiring the land. They were asked questions related to the process of land acquisition, the rights of affected people concerning compensation and support issues, and their opinion on Vietnam’s current land conversion mechanism. From the side of the developers, we discussed the difficulties that developers might face to obtain the land for their tourism projects and the effects of such difficulties on the implementation of the projects. Finally, we consulted three experts on their opinions about the problems of land development for tourism in Vietnam. One of them is working on land acquisition in Vietnam, while the two others are experts in the tourism field. They were asked about their opinions on the current land compensation mechanism and benefit-sharing issues among relevant stakeholders in Vietnam’s tourism development process.

The secondary data were collected from People’s Committee of Lam Son Commune, People’s Committee of Quang Cu Ward and a relevant official document from the website of the People’s Committee of Thanh Hoa province and Hoa Binh’s province. Additionally, some information was also retrieved from public media.

4.2. Four Case Studies

Three cases, namely, Village for Ethnic Culture and Tourism in Hoa Binh province, Linh Truong Beach Resort, and FLC Sam Son project, both in Thanh Hoa province, concern how the investors found a way to prevent a negotiation with local people on the transfer of land use rights by taking advantage of the unclear distinction between ‘public’ versus ‘private’ investment purposes. The last case study is an example of voluntary land conversion based on negotiation between an investor and land users. Some basic information about these case studies is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Profile of four projects.

● Case study 1: Village for Ethnic Culture andTourism, Hoa Binh Province

The project is located in the Lam Son Commune, which is a rural mountainous commune of the Luong Son district, Hoa Binh province, in northwest Vietnam (see Figure 7). In this area, thousands of hectares of agricultural land have been converted into non-agricultural land for tourism development, including golf courses, resorts, and hotels.

Figure 7.

Location of case study 1. Source: From fieldwork and Google Maps.

Decision No. 1044/QD-UB dated 14 June 2004 of the People’s Committee of Hoa Binh decided to acquire a total of 141 ha in Lam Son for a tourism project known as Lang Van Hoa Cac dan toc Hoa Binh, run by the Bach Dang Tourism and Investment Joint Stock Co. In 2007, the project was renamed as the centre for entertainment and recreation of Thung lung Nu Hoang. Since 2004, the investor has the right to use that land for 50 years. As mentioned in the project document, the project includes two main parts: the area for Muong’s cultural village and an area for 20 villas. The compulsory land acquisition mechanism was applied for the project.

According to the regulation at that time, the investor should not face any challenges during the land acquisition process since the People’s Committee of Hoa Binh province already approved the project and issued the Decision on Land acquisition. Nevertheless, since there were different types of land that were acquired for this project, various compensation schemes had to be applied, which created some challenges for the investor during the land acquisition process (Table 4).

Table 4.

Compensation and support policy in case study 1.

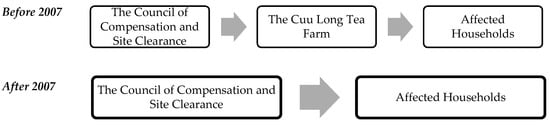

As mentioned in the Decision on Land Acquisition, there were four main types of land users whose land was acquired for the project, which include the Cuu Long Tea Farm company, the Luong Son Plantation company, the People’s Committee of Lam Son commune, and the local households. According to the project manager of the development, the compensation for the households who had contracts with the Cuu Long Tea Farm company was the most difficult one to settle. Figure 8 describes the land compensation process for the Farm and affected households.

Figure 8.

The land compensation process for the Farm and affected households. Source: From a project manager.

On 6 April 2005, the People’s Committee of Hoa Binh province asked the Cuu Long Tea Farm company to terminate the contract with the local households to clear the land, although the duration of the contract had not ended yet, and assigned that land to the investor. Those households only got compensation for the remaining land-related investment at the price of 950 VND/m2 (~€0.038/m2) and no compensation for the land. Consequently, most households did not agree to terminate the contract and stop their farming activities on the land of the Cuu Long farm. To deal with the situation, in 2007 the People’s Committee of Hoa Binh province changed the compensation policy. Based on this new policy, the compensation for the remaining land-related investment increased from 950 VND/m2 to 13,100 VND/m2 (~€0.524/m2) and the amount of 1.5 million VND per labourer (~€60) to support them to find a new job. Also based on this policy, the government under the Council of Compensation and Site Clearance would take the responsibility for compensation payment for the households instead of the Cuu Long Tea Farm company.

● Case study 2: Linh Truong Beach Resort

The Linh Truong Beach Resort is one of many development projects in the Hai Tien Beach Resort Area, Hoang Hoa district, Thanh Hoa province (see Figure 9). In May 2004, the People’s Committee of Thanh Hoa province made a decision to acquire land in Hoang Truong and Hoang Hai communes and assigned the land to two companies, namely, Xu Doai and Viet Tri, to implement tourism projects. According to project license No. 26121000017 of the Thanh Hoa’s People’s Committee in 2011, the tourism project was known as the Linh Truong Beach Resort or the Eureka Linh Truong Beach Resort.

Figure 9.

Location of case study 2. Source: Trivago and Google Maps.

The project was listed as land use for national interest and public interests, and therefore, the compulsory land acquisition mechanism was applicable in this case, and land price for compensation was based on 2004’s stated price framework. According to the local authority, until 2017, 145 households out of 150 affected households have received compensation for land at the price of 13,500 VND/m2 (~€0.5) and an additional 3 million VND (~€120) per household to support for moving. The remaining 5 households asked for a higher price of compensation and also claimed that the project was for business purposes. According to the local people, the land price on the market now is about 6 million VND per m2 (~€240 per m2), and they will move if they get a compensation price of 10 million VND per m2 (~€400 per m2). However, the investor only wanted to give additional supports rather than to increase the land price for compensation. Consequently, no agreement between the investor and the affected households have been reached.

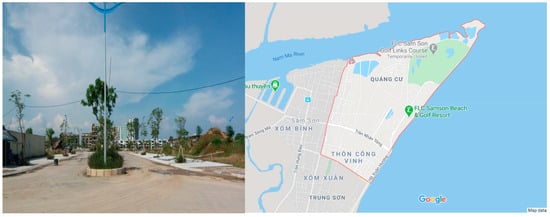

● Case study 3: FLC Sam Son Beach and Golf Resort

Quang Cu ward belongs to the Sam Son coastal city in Thanh Hoa province. The ward has a coastline of 3.3 km and 2.3 km riverfront area (see Figure 10). The arable land in the Quang Cu ward, according to 2019’s Land Use Planning of Thanh Hoa province, amounted to only 1.1 ha, out of a total of 60.47 ha of land used for agriculture. By contrast, land used for non-agricultural sector was up to 581.59 ha. The rapid growth of investments of hotels, resorts, and golf course developments in recent years has contributed significantly to the decrease of agricultural land in the Quang Cu ward.

Figure 10.

Location of case study 3. Source: fieldwork and Google Maps.

FLC Sam Son Beach and Golf Resort is the largest investment project in the Quang Cu ward. The project covered a total area of 200.1485 ha and affected 596 households, with more than 3000 people in total. The development project was divided into two main function zones, namely, FLC Sam Son Golf Course and the FLC ecological tourism urban centre, which include FLC Residences (Villas), the FLC Grand Hotel, and the FLC Luxury Resort. The People’s Committee of Thanh Hoa province granted the permit for the development in 2014.

According to the land acquisition plan of the Thanh Hoa province, both projects are considered as socioeconomic development in the national and public interest. By doing this, the compulsory land acquisition mechanism was applicable in this project.

For this project, the government gave compensation to the affected people for their land, based on their original use, with prices ranging from 1.976 million VND/m2 (~€79.04/m2) to 7.579 million VND/m2 (~€303.16/m2), against the market price of 16–20 million VND/m2 (~€640–€800/m2). In addition, based on Decision No. 2267/UBND-KTTC dated 17 March 2015 of the People’s Committee of Thanh Hoa province, the government also gave every affected household 3 million VND per month (~€120) in 6 months to rent a house and a one-time payment of 15 million VND (~€600) for their livelihood and production stabilization. Meanwhile, the private investor paid the land lease to the government: 2,034,704 VND/m2 (~€81.39/m2) for the villas, 881,378 VND/m2(~€35.26/m2) for the Hotel and Resort and 144,000 VND/m2 (~€5.76/m2) for the Golf Course.

The application of the compulsory land acquisition mechanism with the stated price framework for land compensation, in this case, resulted in strong objections from some of the local residents. They asked for a negotiation mechanism with the investor, because they claimed that the project was for economic development purposes and would only benefit the private investors.

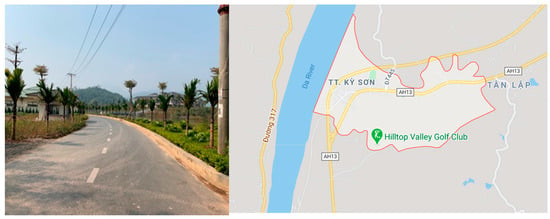

● Case study 4: Geleximco Golf Course, Hoa Binh Province

The Geleximco project, an investment by Hanoi Geleximco Export and Import Stock Company, was approved by the People’s Committee of Hoa Binh province in 2014. The total area of the project is 393 ha, and it is located in the Ky Son district and Hoa Binh city, Hoa Binh province (see Figure 11); 263.9 ha of this project are for a golf course, 59.99 ha are for housing and the development of an ecocity, and 68.99 ha are forest plantation.

Figure 11.

Location of case study 4. Source: fieldwork and Google Maps.

Two approaches to land conversion were applied in this project. First, for the land that was used by local households, after the provincial government approved the project, the investor had to negotiate with the land users on the compensation for the land use rights transfer. The second is for the land that was in use by a public institution. In this case, the local government can directly transfer the user right to the investor.

There were about 179 households who were affected by the project, occupying about 263 ha of the land. The investors negotiated with each of the households for transferring their land and it was done without any significant involvement of public authority. On average, the investor offered a price of 180,000 VND/m2 (~€7.2/m2) against the 120,000 VND/m2 (~€4.8/m2) of the price set by the government. Until 2017, the investor could reach an agreement with almost all households at a price ranging from 230,000 to 260,000 VND/m2 (~€9.2 to €10.4/m2). There were only 2 households, with a total of 23,350 m2 of land, with whom the investor still could not reach an agreement. In May 2017, the investor announced that they would not continue the negotiation with these two households, and instead they would submit a proposal to change the land use plan for the project in which they would exclude the areas that are occupied by these two households.

To conclude, a negotiation mechanism might reduce social dissatisfaction compared with a compulsory land acquisition mechanism, because land users receive the expected price or even a higher price than what they expected. However, for the investor, it is possible to reach an agreement with 80–90% of land users, but it can still be challenging for them to reach an agreement with all land users. Thus, it is still necessary to use an additional compulsory land acquisition mechanism in this case.

5. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on the Land Acquisition Process for Tourism Developments

5.1. Affected People’s Perspectives

On the bargaining power

Obviously, the land users in the compulsory land acquisition process played a passive role in the decision on the size of the compensation. They also had no power to decide whether they should transfer their land-use rights or not. The people whose land was acquired could only accept the decision on land acquisition and the price for compensation which was calculated by the provincial government. As Hoang Truong’s affected land users indicated:

“We were informed by the local authority the decision on land acquisition and compensation plan. We were not allowed to participate in the process of decision-making with regard to land acquisition and compensation.”

Even when the affected local people tried to raise their voice, it did not work. As an individual in the Quang Cu case indicated:

“The households do not agree to move because of the gap between the compensation price and the market price. The locally affected households have made many claims but the local government has denied dealing with our claims. Transaction costs for claiming is also problematic with affected households.”

In contrast with the position of affected people in the compulsory case, in the voluntary land acquisition process, people had more power to negotiate the transferring price. As land users in Ky Son commented:

“We will only sell our land until the investor pays us the price we suggested. Otherwise, no transactions between us and investor will take place.”

On compensation issues

Most of the affected people expressed their dissatisfaction with the compensation offered in the compulsory land acquisition process, as it usually was lower than the market price of the land. As Rong Vong group’s leader, Lam Son commune, said:

“The state agencies imposed compensation prices which were set by the state framework on affected land users without any consultations. That price was lower than the market price. However, it was not the developer’s responsibility.”

Affected people in Quang Cu also shared the same opinion:

“Market price of land was about 4 to 6 million VND per m2, meanwhile, they compensated us at the price of 2 to 2.5million VND per m2. Local people were imposed on the compensated price. If we do not agree or try to object (their offer), they will coerce us to move.”

This opinion is, however, not shared by the affected people when they can negotiate the compensation in a voluntary land acquisition process, since they can get the compensation as they expected. As one household in the Geleximco case said:

“After several negotiations on price, we agreed to sell our land because the investor paid us the expected price.”

However, the primary concern of the affected local people is how to earn a long-term livelihood, since cash compensation is unable to solve that problem. Most of the affected persons in our study are farmers and fisherman; they have faced a lot of challenges in the transformation to a nonfarming livelihood.

“The project in Lam Son causes some negative impacts on the local community’s livelihood. The loss of agricultural land and forest land lead to the increase in unemployment.”

5.2. Local Authority’s Perspectives

On bargaining power

The new 2013 Land Law in Vietnam has given better opportunities to local affected people to negotiate the compensation in a land acquisition process. Although the government is still the sole owner and administrator of the land, the bargaining power of the land users is now recognised by the local authorities:

“With tourism development projects, the developers have to negotiate with the people who have the land on the land price and other compensation payments. The State will not intervene in this process. If 80% of households agree with the developers and only 20% do not the project, in this case, probably has to be cancelled.”

On compensation issues

The affected people might have a better opportunity to obtain better compensation in a voluntary mechanism land acquisition since they can negotiate with the investor. Although the social legitimacy of an acquisition process could be secured when people are better off with a better compensation (Bockhorst 2014), the local government also needs to secure the continuation of a development to support economic growth in their jurisdiction. Considering that Vietnam has experienced a high tourism growth rate in recent years, it is easy to understand that local governments have prioritised tourism as an important growth engine and source of foreign direct investments. Tourism zoning, infrastructure development, and investor-friendly land regulation are needed to pave the way for tourism development. Therefore, the local government might be concerned that the development would get stalled or even fail if the local people push too much for the compensation in a negotiation process. As a local authority commented during an interview:

“For each land user, they (could) ask for a different price which is often much higher than the stated price. They could suggest an incredible price for no reason. If the investor does not agree with their conditions (price), the project will not be implemented.”

The local authority might believe that tourism development can create job opportunities, alleviating poverty, and could improve the capability of local government to eventually support the livelihood of the local people. The local authority in the Lam Son commune mentioned during the interview:

“Affected people frequently do not agree with land price for compensation because it is lower than the market price. But, the developers cannot pay them at the market price. Instead, the local authority may give more additional financial supports which is even higher than compensation money and the developers have to pay for that.”

With this argument in mind, dispossession and displacement of local communities could be justified by invoking the ‘public purpose’ of tourism development, making the local authority to preferably use compulsory land acquisition.

5.3. Developers’ Perspectives

On bargaining power

Sharing the same opinion with the local authority, developers think that land users could play a decisive role in a negotiation case. As the developer in the Lam Son project said:

“It is much more difficult for the developers when only 10% or 20% of land users say no with our compensation payment under no circumstances. So, in such situation, should the State authority take action!”

However, the negotiation mechanism might contribute to a decrease in people’s complaints and conflicts. As confirmed by the developer in the Lam Son project:

“Voluntary land conversion based on negotiation decreases people’s complaints and conflicts related to land because there is no intervention by the State. This mechanism also may be better for investors with a strong financial capacity.”

On compensation issues

Understandably, the compensation arrangements could be a serious issue for developers, especially when it would decrease the profitability of their project plan. This argument was confirmed by developers during the interview:

“When it is necessary, investors can increase the level of compensation. Nevertheless, it should not exceed the expected returns on the investment, otherwise, it will push the investment costs up too much.”

The ambiguous land price is another concern of the developer, as further explained:

“The evaluation of a parcel is the most challenging work for developers.”

“The gap between the price set by the state and the market price of land still exists. In fact, the investors have to negotiate with land users based on a state-price framework (…). But these prices can be unreliable as sellers and buyers often report a lower stated price than the actual price of land transactions.”

5.4. Experts’ Perspectives

On bargaining power

The role of the State is substantial in the land conversion process in Vietnam. In fact, whether a project is considered for economic purpose or for the national and public interest is finally decided by the State. Hence, land users in Vietnam have weak powers in the whole negotiation process. As an expert pointed out:

“Under the current Vietnam’s property right regime, the land is owned by the State whereas people only obtain land use rights. Therefore, any developers (i.e. state-owned or privately-owned companies) with significant support of the State may acquire the land from people under the purpose of national and public interests. The developers, in fact, make a good deal as they can take advantage of the Stated-price framework to compensate unfairly for affected people. In the end, only affected people lose, because they are losing their land and their livelihoods.”

On compensation issues

Due to the serious concern about people’s livelihoods in the long term and insufficient compensation, land compensation regulations in Vietnam should be reconsidered, taking not only economic aspects into consideration, but social aspects as well. As an expert in Hue University commented:

“Land prices for compensation are currently unfair for affected people. They should receive higher compensation prices. Additionally, the compensation package can also be paid in the form of capital contribution or involvement in tourism projects.”

Another expert also suggested:

“Next to a better compensation price based on market value, training, recruiting for jobs or a business contract for affected people should be taken into consideration as well.”

6. Discussion

The introduction of the Land Law in 2013 was expected to reduce land-related conflicts in Vietnam. Nevertheless, in reality, land conversion processes continue to cause controversy regarding the notion of national and public interests versus private interests, the roles of each stakeholder in the land conversion process, and the ambiguous land pricing system. Those issues have resulted in more difficulties in the implementation of development projects [4], and it also has profoundly affected local people.

6.1. Public Interest versus Private Interest

According to the 2013 Land Law, only projects for socioeconomic development in the national and public interests are applicable for compulsory land acquisition in Vietnam. However, the ambiguities in how to define public interest projects still cause land conflicts in the country [30]. Tourism development is a good example of economic sectors in which these conflicts emerge and appear to be difficult to solve. Thousands of land users in our case studies were evicted from their farmland. Consequently, conflicts over land between the State and locally affected people have arisen. Apparently, the attempts to reduce land-related conflicts in the process of land acquisition in Vietnam have not yet brought significant change to the affected local people.

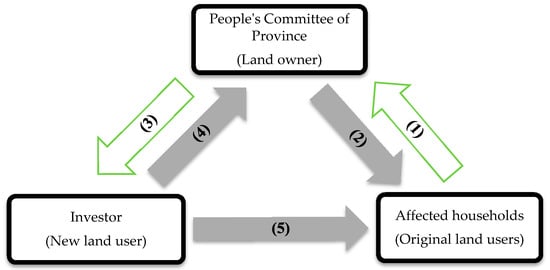

6.2. Roles of the State, Investors, and Land Users

The implementation of the 2013 Land Law in Vietnam has marked significant changes in the land acquisition process, leading to more power for land users. The State’s position has changed from a decisive role into a more supportive role in the process of land conversion for economic projects, while land users have gained a more decisive role in negotiation processes with regard to the implementation of projects that are not considered in the national or public interest (see Figure 12 ).

Figure 12.

The roles of each stakeholder in the compulsory land acquisition process. Source: fieldwork.

However, since the State still has the sole ownership right over the land, it retains the power to decide which projects should go for ‘national and public interest’ purpose, and hence the right to decide whether the compulsory land acquisition mechanism can be applied for a development project that de facto is for economic purposes. It means that land users are still facing the risks of expropriation for the ‘public interest’ projects even though they are, by law, better protected, and their land-use rights are very well defined.

Notes:

- (1)

- To return the land to the State

- (2)

- To pay compensation and additional support for livelihood and production stabilization and others

- (3)

- To assign land and land use right certificates, to issue land lease contracts

- (4)

- To pay the land use fee and land lease fee

- (5)

- To offer job opportunities for affected people (no obligation)

6.3. Compensation Price: the Interests of the State, Investors, and Land Users

Each stakeholder involved in the land conversion process has different interests over the compensation price. For profit-driven investors, their objective is to pay as little compensation as possible to reduce investment costs. For affected land users, they aim for as much compensation as possible. Meanwhile, the two-price system on the land market, namely, the government price system and the market price system, remains problematic in Vietnam, because of the large gap between the two price systems. The State land pricing framework is applicable for calculating the compensation level in a compulsory land acquisition mechanism, while the market price is often used to calculate the value of land use rights in the case of voluntary land conversion. By introducing a low price in the land pricing framework, the State aims to attract more investment in a land development process, ignoring the position of the affected land users. In the case of voluntary land acquisition, social tension over the issue of compensation tends to be reduced as they gain a better deal with investors.

6.4. Compensation for Loss of Livelihoods

Arguably, land users in Vietnam could receive better compensation and support from the State during the process of land conversion after the introduction of the 2013 Land Law. By law, the State should always put a stable livelihood for affected land users after the land conversion process as its top priority. The land law regulated that compensation for affected people should be in the form of land and, if no land is available, compensation in cash and support in training, change of occupation, and job seeking. It means that the central concern is to find a mean for the long-term livelihood of the affected local people. However, in reality, both compensation and supports are usually in the form of cash, as is evident from all our case studies. In case study 1 in the mountainous area of Lam Son, all affected people are farmers and their livelihoods had been based on agriculture. Thus, losing their farming land, they lose their livelihoods. In case study 2, in the coastal area of Hai Tien, affected fishermen were relocated far from the sea. As their livelihood heavily depends on the sea, the eviction from the coastal line caused many difficulties for the local fishing community to find a new means for their living. In other words, a higher level of financial compensation cannot ensure a better life for affected people as they are struggling to find the means for long-term livelihood.

7. Conclusions

Tourism has developed rapidly in Vietnam in recent years, and tourism investment projects have been actively encouraged by the Vietnamese government. At the same time, Vietnam is still in the process of improving its land legal system. Especially, in 2013, the Vietnamese government introduced the latest version of the land law, which subsequently has affected the land conversion process. As a result of the State promotion of tourism investments and land legal system’s reforms, Vietnam has experienced strong growth in tourism projects as well as a significant increase in investment in land for tourism. A large area of land in rural and coastal regions has been converted into tourism purposes. The findings from our case studies show that the land acquisition process continues to cause social dissatisfaction in Vietnam, while the rights of local people are still not guaranteed because of the ambiguities with regard to how projects are defined for ‘public versus private’ interest and the State’s role in defining the compensation prices. Although this result could be complemented with quantitative research in the future to have more general results, it could already contribute to raising a debate on an explicit distinction between “public purpose” and “economic interest,” especially in the context of the land acquisition process. One can expect that the on-going urbanisation trend in Vietnam will put even more pressure on land conversion. This increased urbanisation pressure may lead to further conflict over the purpose of development projects, cannot properly protect the position of local communities in a fair way, and may lead to stalled investment projects and increased financial risk for property developers. Alternatively, one might consider to abandon this explicit distinction made and instead revise the conditions to compulsory land acquisition independent of its purpose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.T.T.D., D.A.A.S., and E.v.d.K.; data curation: M.T.T.D.; formal analysis: M.T.T.D. and D.A.A.S.; investigation: M.T.T.D.; methodology: M.T.T.D., D.A.A.S., and E.v.d.K.; resources: M.T.T.D.; supervision: D.A.A.S. and E.v.d.K.; writing—original draft: M.T.T.D.; writing—review and editing: M.T.T.D., D.A.A.S., and E.v.d.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Vietnamese Government through the Ministry of Education and Training in the form of VIED scholarship 911.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the respondents in the four case studies for their involvement. Special thanks to Mr. Cuong, Mr. Hieu, and Mr. Quyen for arranging our work in the study areas. We are also grateful to the Ministry of Education and Training of Vietnam for the financial support in carrying out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, H.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, X.J. Land policies, tourism projects, and tourism development in Guangdong. J. China Tour. Res. 2017, 13, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. A Curious Case of Property Privatization; Ho Chi Minh City-Vietnam. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.T.; Tran, V.T.; Bui, Q.T.; Man, Q.H.; de Vries Walter, T. Socio-economic effects of agricultural land conversion for urban development: Case study of Hanoi, Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2016, 54 (Suppl. C), 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuc, N.Q.; Van Westen, A.C.M.; Zoomers, A. Agricultural land for urban development: The process of land conversion in Central Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Suu, N. Industrialization and Urbanization in Vietnam: How Appropriation of Agricultural Land Use Rights Transformed Farmers’ Livelihoods in a Peri-Urban Hanoi Village? Final Report of an EADN Individual Research Grant Project, EADN Working Paper; Vietnam National University: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyen, N.Q. Land Law Reforms in Vietnam: Past and Present; Working Paper Series 105; Asian Law Institute, National University of Singapore: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mangione, V. The evolution of the Public Purpose Rule in compulsory acquisition. Prop. Manag. 2010, 28, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D. Tourism policy development in Vietnam: A pro-poor perspective. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Hollenhorst, S.; Harris, C.; McLaughlin, W.; Shook, S. Envrionmental management: A study of Vietnamese hotels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, N.T.K. Sustainable Tourism Development in Vietnam. In Linking Green Productivity to Ecotourism: Experiences in the Asia-Pacific Region; Asian Productivity Organization Publication: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 249–263. [Google Scholar]

- VNAT. Vietnam’s Annual Report on Tourism; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018.

- GOV. Strategy on Viet Nam’s Tourism Development until 2020, Vision to 2030. 2011. Available online: https://www.global-regulation.com/translation/vietnam/2956124/201-qd-ttg-decision%253a-approval-of-the-%2522master-plan-for-development-of-vietnam-tourism-2020-vision%252c-to-2030%2522.html (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- VNAT. Vietnam Annual Tourism Report; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014.

- VNAT. Vietnam’s Annual Report on Tourism; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015.

- VNAT. Some Achievements in the Development of Vietnam’s Tourism Sector; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009.

- VNAT. Report on Evaluation of the First Five Years Implementation of Strategy on Viet Nam’s Tourism Development until 2020, Vision to 2030; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016.

- VNAT. Vietnam’s Annual Report on Tourism; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Tuan, V.K.; Rajagopal, P. Analyzing factors affecting tourism sustainable development towards vietnam in the new era. Eur. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2019, 7, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A.A.; Demsetz, H. The Property Right Paradigm. J. Econ. Hist. 2010, 33, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehr, D. Land reforms and the tragedy of the anticommons—A case study from Cambodia. Sustainability 2012, 4, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeliushnikov, R.; Kuznetsov, A.; Demina, N.; Kuznetsova, O. Threats to security of property rights in a transition economy: An empirical perspective. J. Comp. Econ. 2013, 41, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, H.; Lahiff, E. Land reform in Namaqualand, 1994–2005: A review. J. Arid Environ. 2007, 70, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J. Land Conversion and Misallocation Across Cities in China. SSRN 2019. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.M.Y. “Our Lands are Our Lives”: Gendered Experiences of Resistance to Land Grabbing in Rural Cambodia. Fem. Econ. 2019, 25, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, S.; Heng, K. Assessing the Impacts of Chinese Investments in Cambodia: The Case of Preah Sihanoukville Province. Issues Insights 2019, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D.; Sirithet, A.; Rakyuttitham, A.; Wulandari, S.; Chomchan, S.; Samranjit, P. Land Grabbing and Impacts to Small Scale Farmers in Southeast Asia Sub-Region; Local Act Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015.

- Nguyen, T.B.; Van de Krabben, E.; Samsura, D.A.A. A curious case of property privatization: Two examples of the tragedy of the anticommons in Ho Chi Minh City-Vietnam. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2016, 21, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Vu, K.T. Land Acquisition in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1097–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Musil, C. Periurban Land Redevelopment in Vietnam under Market Socialism. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 1146–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Kim, D.-C. Farmers’ landholding strategy in urban fringe areas: A case study of a transitional commune near Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.F. Land Policy in Vietnam. J. Macromarketing 2011, 32, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingalls, M.; Diepart, J.-C.; Truong, N.; Hayward, D.; Neil, T.; Phomphakdy, C.; Bernhard, R.; Fogarizzu, S.; Epprecht, M.; Nanhthavong, V.; et al. State of Land in the Mekong Region; Bern Open Publishing: Bern, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyen, T.Q.; Van Huong, V. The impact of land loss on household income-The case of Hanoi’s sub-urban areas, Vietnam. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2014, 15, 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Mazyrin, V.M. Economic modernization in Vietnam from industrialization to innovation stage. VNU J. Sci. Econ. Bus. 2013, 29, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T. Perspectives on land grabs in Vietnam. In Land Grabs in Asia; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 166–182. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé, D. Critical reflections on land appropriation and alternative urbanization trajectories in periurban Vietnam. Cities 2016, 53, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.; Mellac, M.; Scurrah, N. The political Economy of Land Governance in Vietnam; Mekong Region Land Governance: Vientiane, Laos, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huu, T.P.; Phuc, N.Q.; Westen, G.V. Vietnam in the debate on land grabbing: Conversion of agricultural land for urban expansion and hydropower development. In Dilemmas of Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Between Dam-Induced Displacement and Sustainable Development; Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, P.; Ouyang, Z.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Park, H.; Chen, J. Urbanization, economic development, environmental and social changes in transitional economies: Vietnam after Doimoi. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 187, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.T.T.; Quynh, T.T.; Say, N.T.; Tien, N.T.T. Pháp luật về quyền tiếp cận biển của cộng đồng—Kinh nghiệm quốc tế và một số gợi ý cho pháp luật Việt Nam; Trường Đại học Kinh tế -Luật, Đại học Quốc Gia Hồ Chí Minh: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Options, E.T. IFIs and Tourism: Perspectives and Debates; Equitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS): Bangalore, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Online, E.J.A. EcoPark Satellite City Project, Hanoi, Vietnam. 19 June 2015. Available online: https://ejatlas.org/conflict/ecopark-satellite-city-project-hanoi-vietnam (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Online, N.L.D. Dùng dằng lối sống biển. 22 May 2019. Available online: https://nld.com.vn/thoi-su/dung-dang-mo-loi-xuong-bien-20190521211701721.htm (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Online, D.N.T. Preserving Fishing Jobs: An Urgent Must-Do. 20 April 2018. Available online: https://baodanang.vn/english/society/201804/preserving-fishing-jobs-an-urgent-must-do-2595646/ (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Studies, F.L.T. Compulsory Acquisition of Land and Compensation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, A.W.; Tu, P.Q.; Burke, A. Conversion of Land Use in Vietnam through a Political Economy Lens. VNU J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Duan, J.; Zhang, G. Land Politics under Market Socialism: The State, Land Policies, and Rural–Urban Land Conversion in China and Vietnam. Land 2018, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E.; Le, A.-D. Saigon-Ho Chi Minh City. Cities 2016, 50, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien Thu, T.; Perera, R. Consequences of the two-price system for land in the land and housing market in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, T.W. Complusory Land Acquisition and Voluntary Land Conversion in Vietnam: The Conceptual Approach, Land Valuation and Grievance Redress Mechanisms; Word Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).