Abstract

Coastal wetlands are among the most ecologically valuable yet vulnerable ecosystems, particularly in regions experiencing rapid urban expansion. This study provides a four-decade assessment of land use and land cover (LULC) dynamics and their implications for ecosystem service value (ESV) in the Beidagang Wetland Nature Reserve (BWNR), located adjacent to the fast-developing Tianjin region in China. Using an integrated geospatial framework, combining multi-temporal remote sensing, supervised classification, and a modified benefit-transfer valuation approach, we analyzed LULC transitions and the associated variations in ecosystem service values (ESVs) across three critical phases: (i) a period of minimal anthropogenic pressure and climate influence (1984–1999); (ii) a phase of increased human activities (2000–2013); and (iii) an active ecological restoration period (2014–2023). Findings across the three phases show that the LULC changes are not in equilibrium, as indicated by the decrease in vegetation (−46.43%) and bare ground (−31.34%), while the water areas (+547.50%) and built-up areas (+14.40%) increased remarkably. This indicates an intensive human-induced environmental transformation; although some ecosystem service functions degraded, the total ecosystem service value (ESV) of BWNR continued to increase due to water area expansion. The variations in ecosystem service value (ESV) in response to LULC changes resulting from anthropogenic activities and climate change were estimated, and the results show that the total ESV of BWNR was approximately CNY 10,631.1 million in 1984, CNY 15,078.7 million in 2000, CNY 17,768.3 million in 2013, and CNY 19,365.4 million in 2023. Findings from this study will contribute to the theoretical understanding of coastal wetland vulnerability and provide empirical evidence for the coordinated management of wetland ecological conservation and economic development in the context of rapid urbanization in Tianjin’s coastal areas.

1. Introduction

Coastal wetlands deliver a range of valuable ecosystem services (ES), such as water purification [1,2], biodiversity conservation [3,4], and shoreline protection [5,6]. Coastal wetlands are also increasingly recognized for their exceptional biomass productivity and high carbon sequestration rates, which help mitigate climate change [7,8]. However, as coastal wetlands are situated at the land–ocean interface, where pronounced spatial gradients exist in environmental stressors (for instance, salinity), slight changes in those stressors may lead to fundamental alterations in the structure and function of coastal wetland ecosystems [9,10,11]. This vulnerability has led to the global degradation of coastal wetlands over the past few decades [12,13,14]. Countries have made numerous attempts to restore those vital ecosystems, such as re-establishing hydrological connectivity and reintroducing native vegetation [15,16]; however, the effectiveness of those restoration measures has not been fully validated [17,18]. Given the critical ES provided by coastal wetlands, it becomes imperative to assess whether there is an improvement in the ES values (ESVs) resulting from the restoration efforts [19] or not. This will provide valuable insight for evaluating restoration effectiveness and guiding future conservation strategies.

Assessing ESVs in coastal wetlands encounters numerous challenges, partly due to the complex interplay of hydrological, ecological, and biogeochemical processes that can vary significantly within and across coastal wetlands [20,21,22,23]. In particular, coastal wetlands differ markedly in their key processes and key components (hydrological regime, vegetation structure, and habitat characteristics) [24,25], creating pronounced spatiotemporal variability in the delivery of ES [26,27]. Additionally, the impacts induced by climate change and human activities further alter coastal wetland structure and function, introducing uncertainties in ESV assessments [28,29,30]. These complexities, combined with data limitations, may result in biased ES valuations for coastal wetlands [31,32,33], which requires an adaptive and region-specific framework to accurately quantify ESV [34].

Coastal wetlands face severe habitat loss and functional degradation due to intensive human disturbances, resulting in water quality deterioration, coastal erosion, and wetland losses [18,35,36]. Those factors have compromised the capacity of the coastal wetland to deliver critical ES [37,38,39,40]. In particular, land use and land cover (LULC) changes caused by human activities are a primary driver influencing ESVs in coastal wetlands [41,42], as those changes can directly affect the ecosystem structure and function [43]. For instance, similar issues occurred in BWNR during the high-disturbance stage (2000–2013), where wetland fragmentation was caused by aquaculture pond excavation [17]. Rapid urbanization and infrastructure developments [44], including land reclamation and shoreline modification, have further fragmented wetland habitats and resulted in declining biodiversity [45,46,47]. Furthermore, associated with LULC changes, agricultural and industrial pollution has fundamentally altered the ecosystem structures of coastal wetlands and reduced their adaptive resilience [48,49,50]. As human activities pose major challenges for assessing ESVs in coastal wetlands [51,52], an assessment of how LULC dynamics affect ESVs is essential for understanding ecosystem response mechanisms and formulating targeted conservation policies for coastal wetlands [53,54].

To effectively address the above challenges, a comprehensive strategy is essential for quantifying ESVs, including standardized evaluation frameworks that can integrate ecological, social, and economic factors [55]. Thus, the use of the benefit transfer approach (BTA) is a cost-effective method for estimating ESVs by extrapolating data from existing primary valuation studies to a targeted site where primary data are unavailable [56,57,58]. As such, the BTA is valuable in data-scarce regions, where conducting original valuation investigation (contingent valuation and hedonic pricing) is logistically constrained [59]. This approach can also provide immediate information to decision-makers on the benefits of various land use options and the best approaches for the sustainable management of land resources [57,60,61]. Thus, the BTA offers a scientifically robust yet practical method for evaluating ESVs in coastal wetlands, where the complex natural processes combined with human disturbances create unique challenges for conventional valuation approaches [56,61,62].

This study aimed to assess the spatiotemporal changes in the LULC of the Beidagang Wetland Nature Reserve (BWNR) in northern China between 1984 and 2023 and to evaluate their consequent impacts on ESVs. Unlike existing studies focusing on single time periods or single driving factors, this study quantifies the dynamic response of LULC ESV under the combined driving forces of human activities and climate factors using 39-year long-term data and policy node division, providing a more systematic methodological reference for wetland restoration effectiveness assessment.

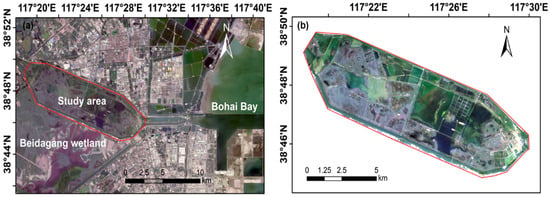

As an important costal wetland that experienced substantial anthropogenic disturbances, the BWNR has undergone extensive restoration efforts to mitigate those disturbances, making it suitable for assessing restoration effectiveness through the ESV analysis. The geographic location and spatial extend of the BWNR are presented in Figure 1.

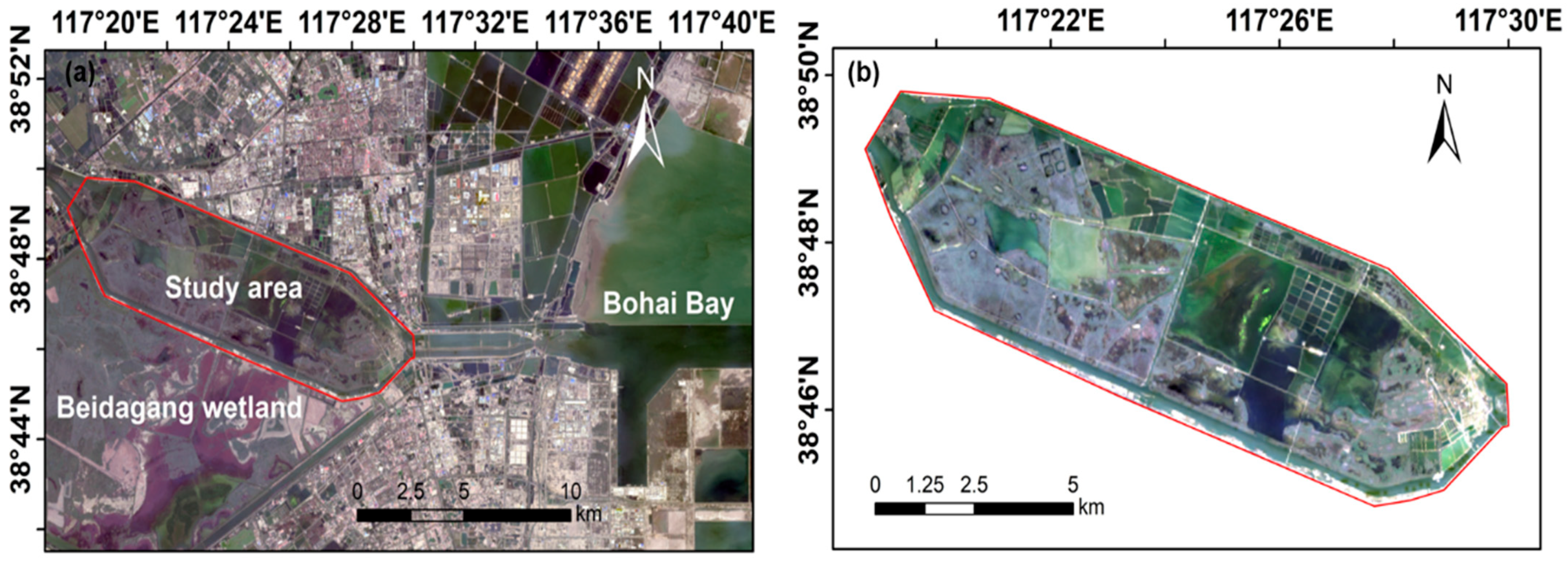

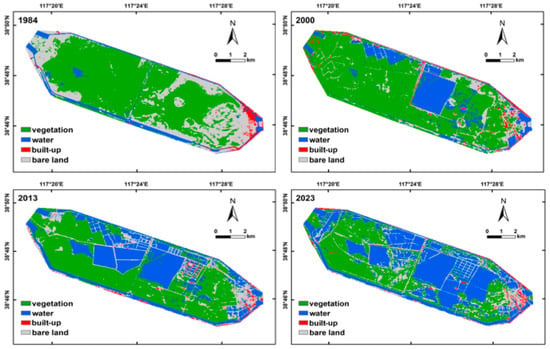

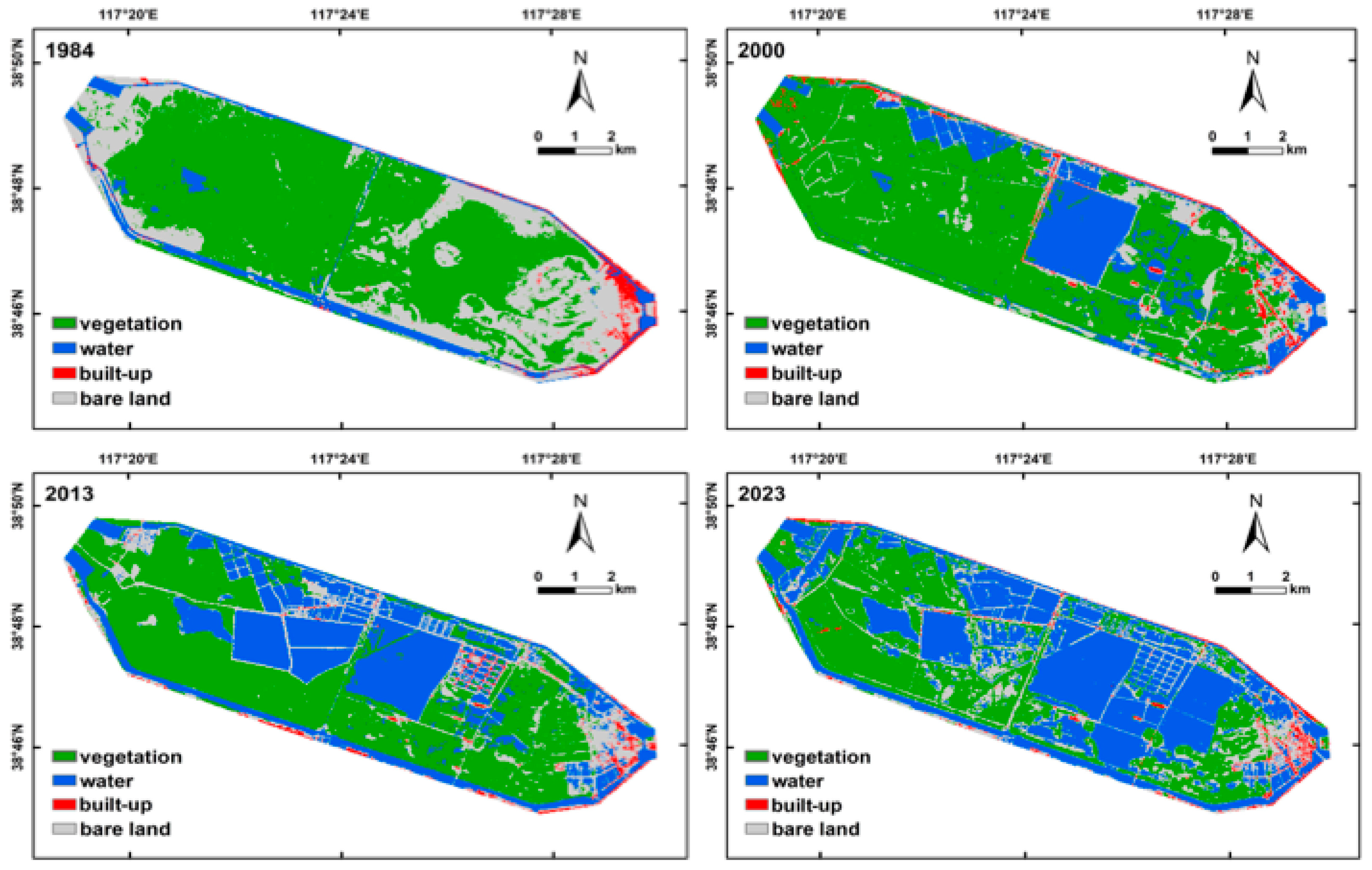

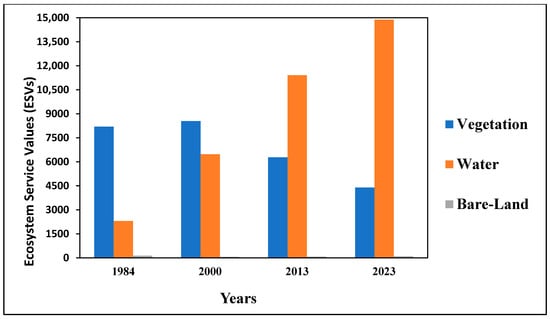

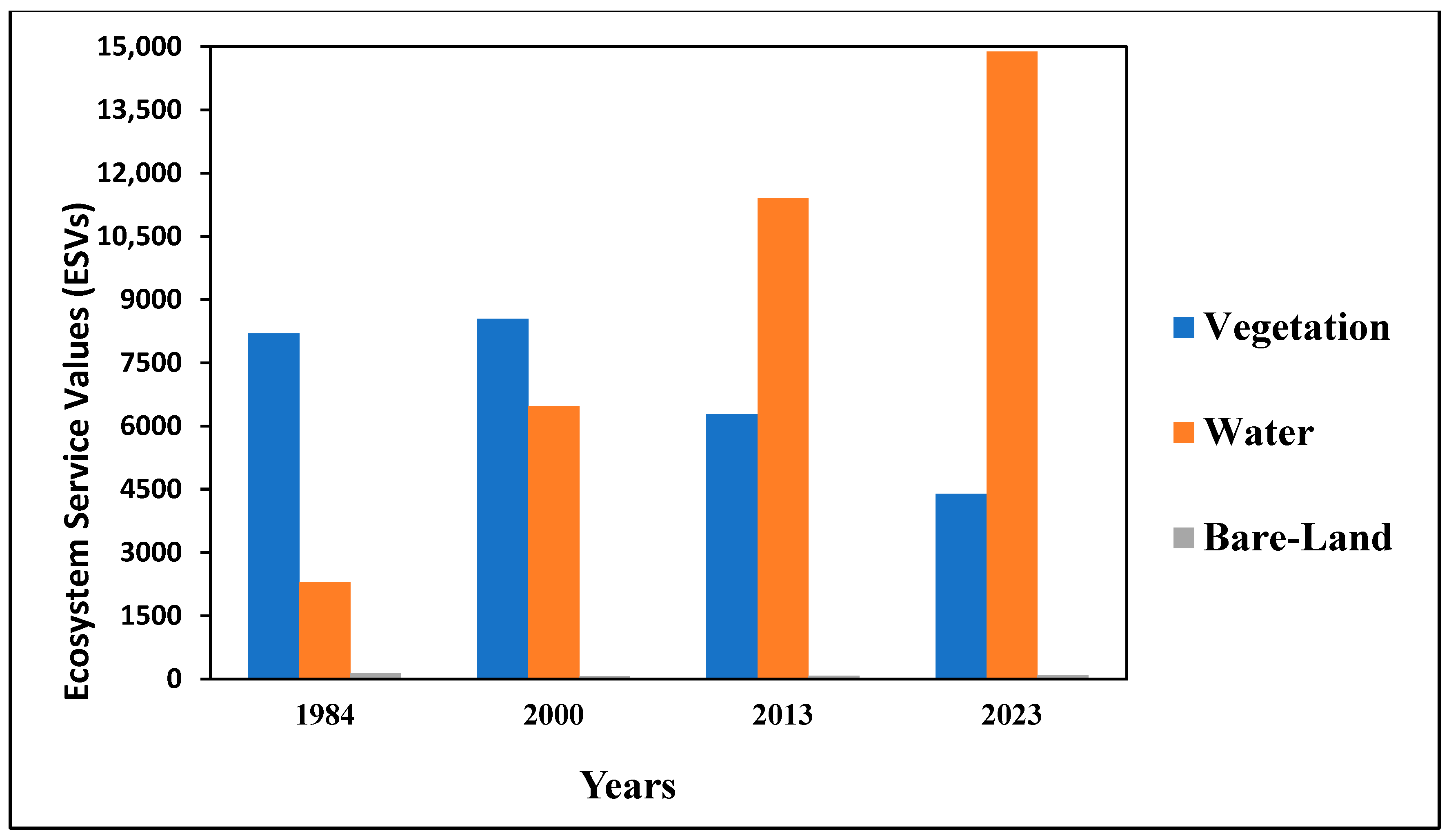

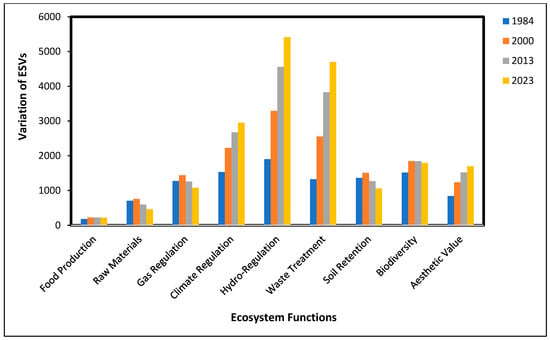

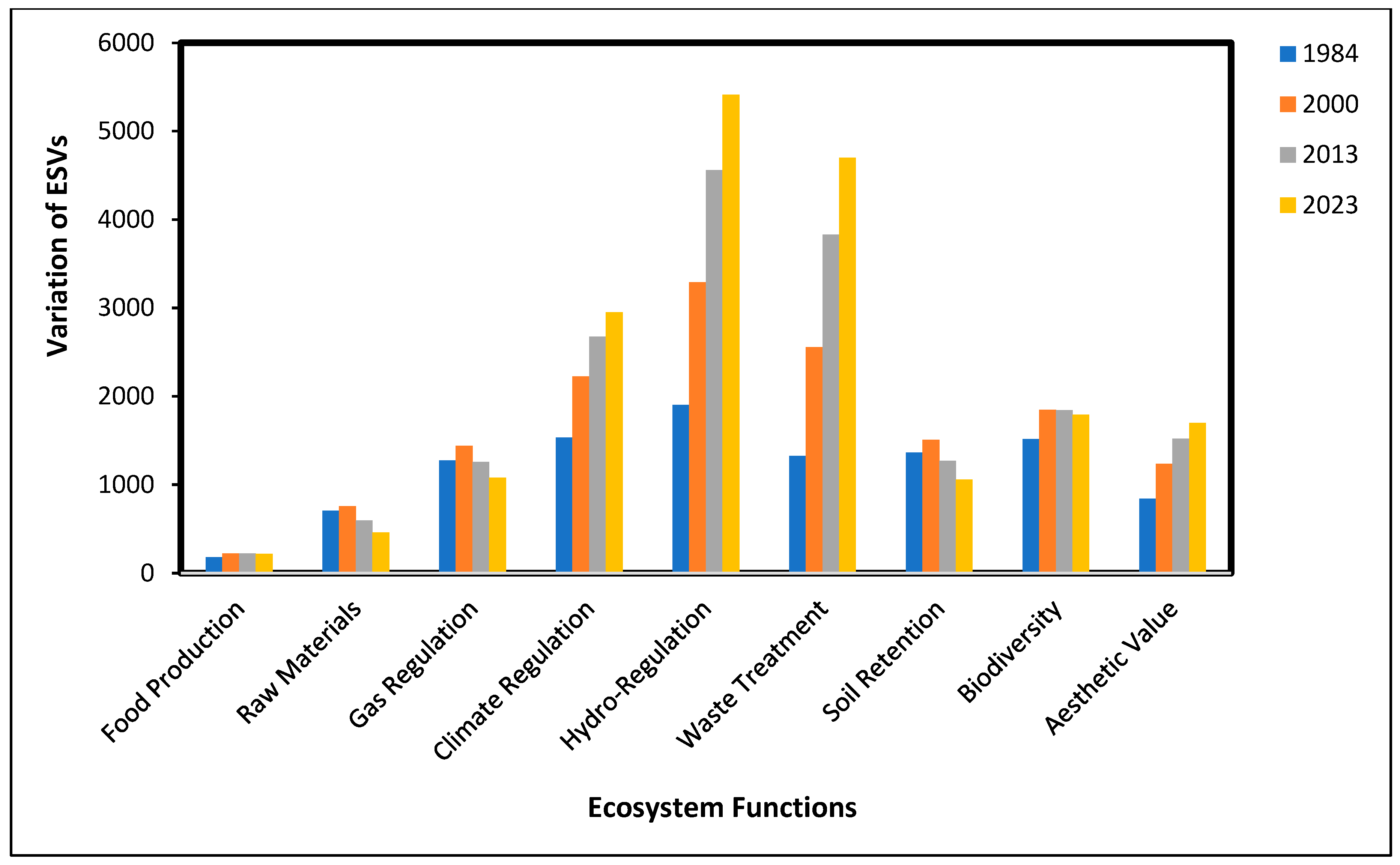

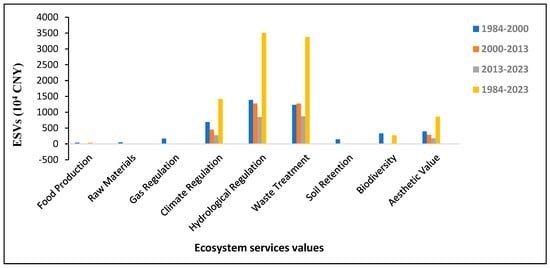

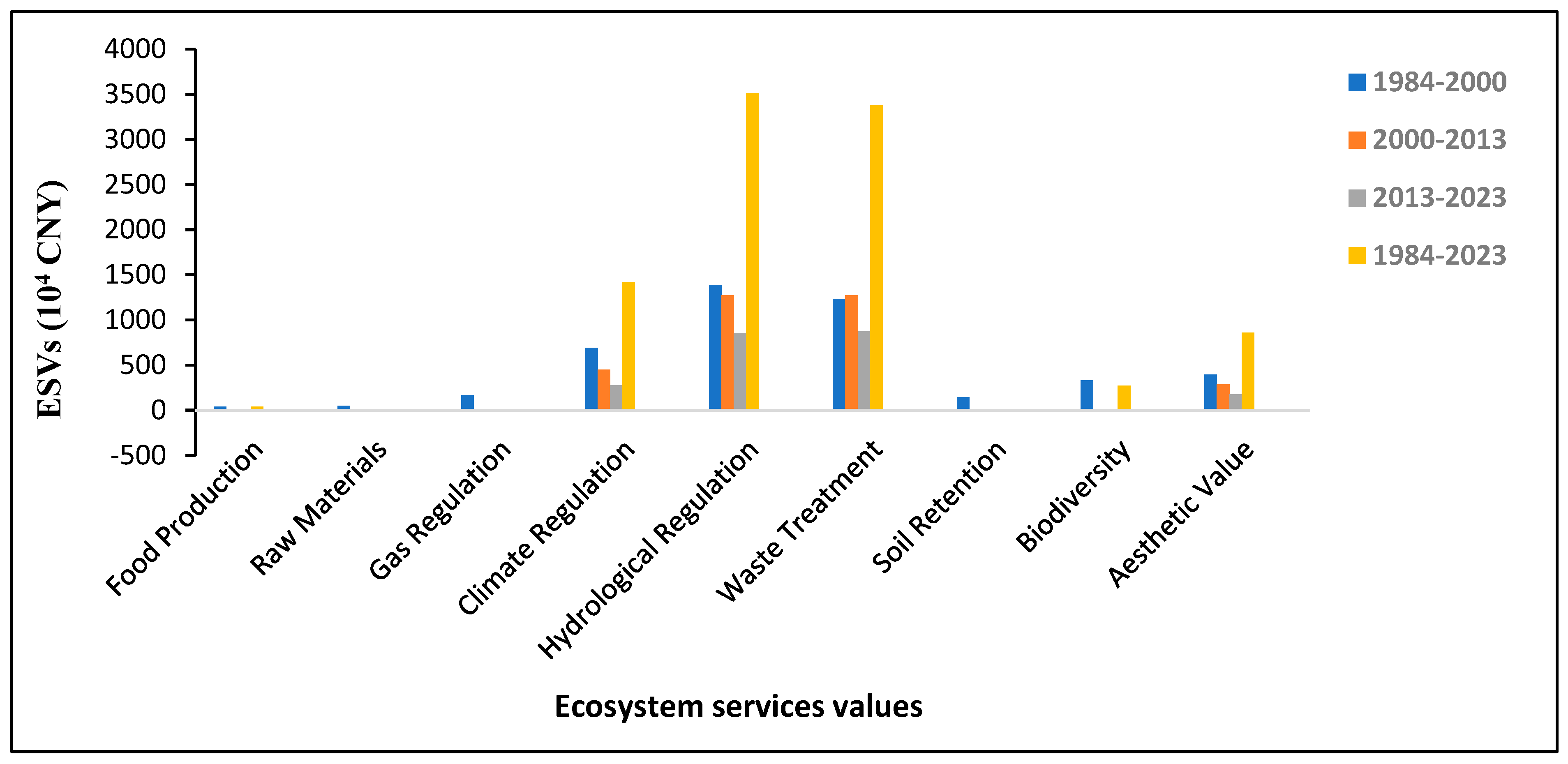

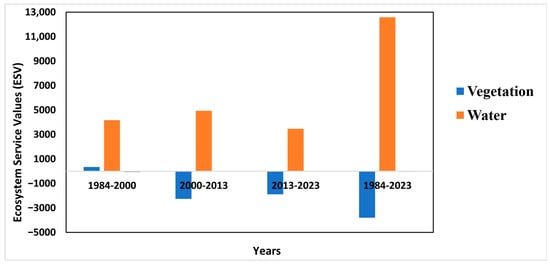

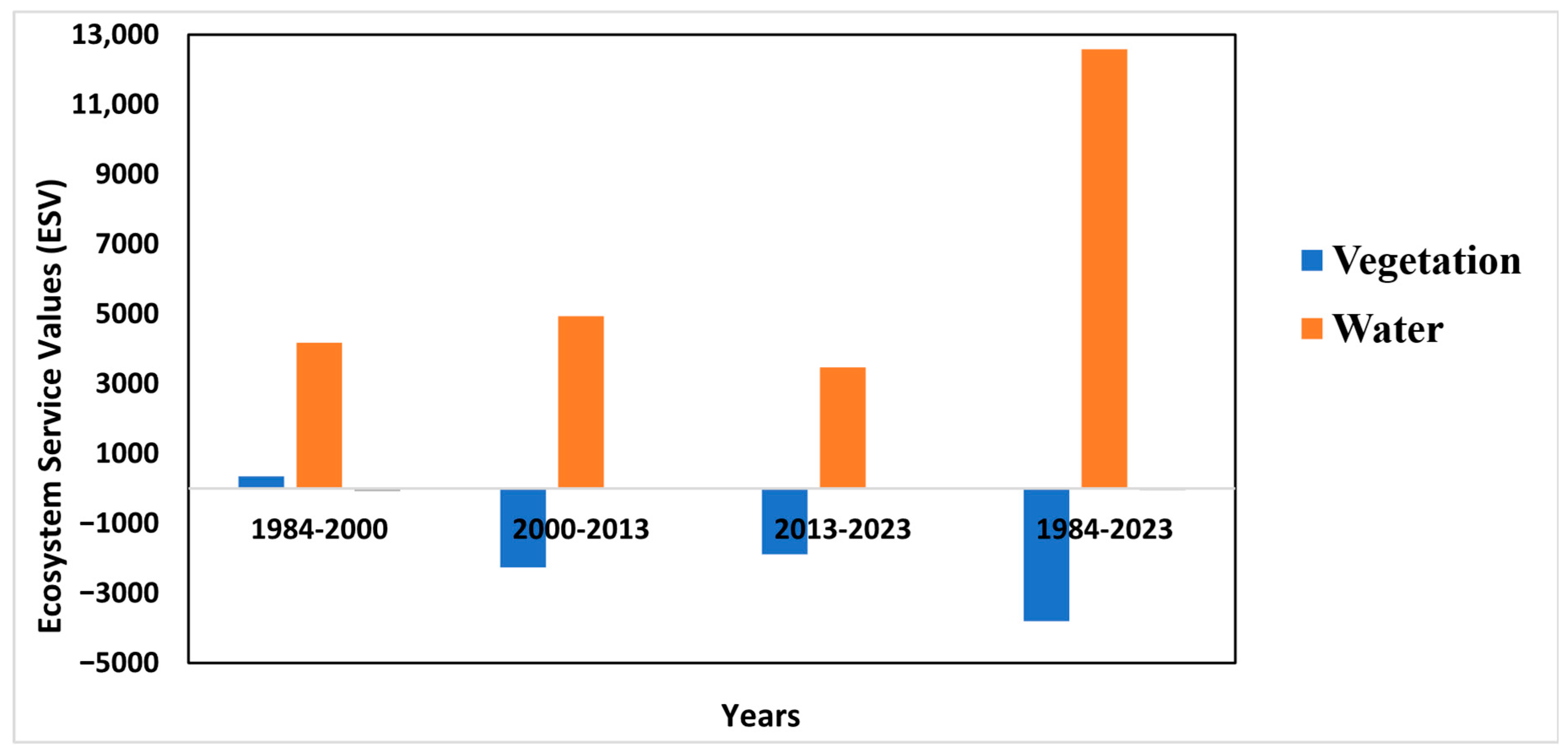

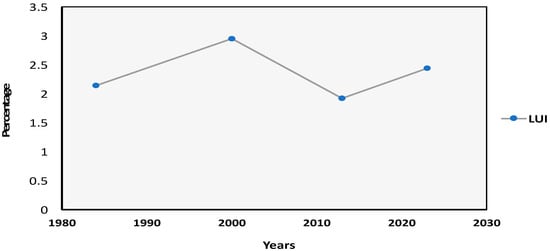

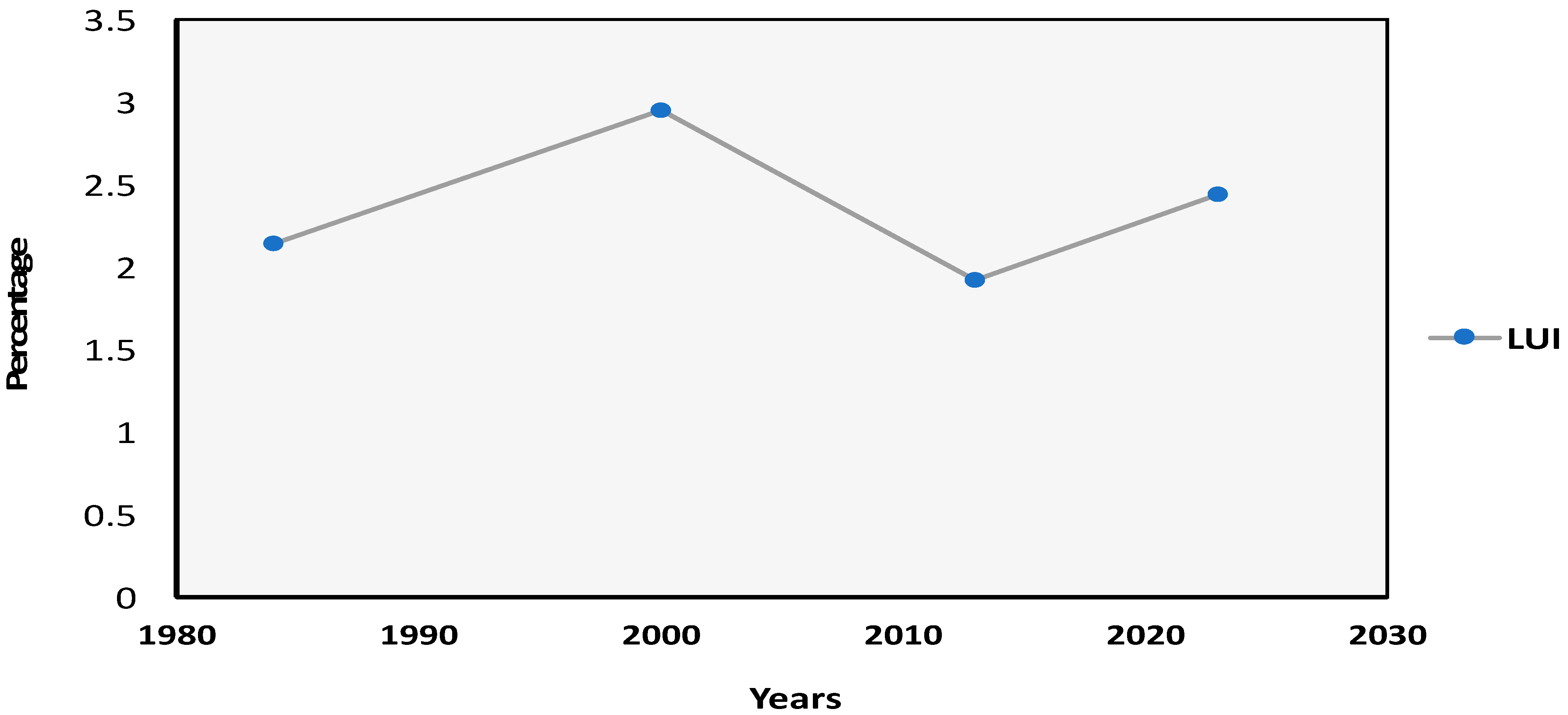

Based on the BTA, an assessment framework was proposed in this study to (1) assess the impact of the LULC on ESVs and (2) evaluate the efficacy of the current conservation policies in mitigating these threats in the BWNR; the overall methodological framework is illustrated in Figure 2. Using this framework, multi-temporal LULC classification maps were produced to characterize long-term spatial and temporal changes in land cover (Figure 3). These LULC dynamics form the basis for quantifying ESVs associated with different land use types (Figure 4) and for analyzing their temporal variations from 1984 to 2023 (Figure 5). In addition, the ESVs of different ecosystem service functions and their long-term changes are assessed to reveal functional shifts in ecosystem services (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Finally, changes in land-intensity, changes in land-use intensity, reflecting the degree of human disturbance and management intervention in the BWNR, are quantified using a land-use intensity index (Figure 8). Tables were included to provide key quantitative information for the study. The adjusted monetary coefficients used to estimate ESVs for different LULC categories are summarized in Table 1. Long-term changes in LULC area in the BWNR are presented in Table 2, while the intensity are rates of LULC change are reported in Table 3. The conversion relationships among different LULC types over the study period are shown in Table 4. Estimated ESVs for different LULC categories are provided in Table 5, and the ESVs of different LULC ecosystem service functions are summarized in Table 6. Long-term ESVs of different LULC categories from 1984 to 2023 are further presented in Table 7, while the corresponding annualized ESV change rates are reported in Table 8. Variations in ESVs among different LULC categories over the study period are summarized in Table 9, and the sensitivity coefficients of ecosystem service values for different LULC classes are provided in Table 10. The results of this study provide a new perspective on coastal wetland management by elucidating the effectiveness of mitigation strategies to overcome the impact of the LULC on ES provisioning.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Area

The study area is a part of the BWNR and is located about 6 km inland from the Bohai Sea in Northern China (Figure 1). Geographically, the BWNR is located in the northern part of China between 117°20′ E and 117°39′ E and 38°45′ N and 38°50′ N. Listed as a Ramsar wetland of international importance (https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/2425) (accessed on 2 May 2025), this ecologically important coastal wetland provides diverse ES; for example, it is a crucial stopover site for migratory water birds along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway [63]. A monsoonal sub-humid climate is prevalent in the region with hot and rainy summers and cold and dry winters [64]. From 1984 to 2023, the local mean annual precipitation (619.7 mm) and air temperature (13.2 °C) were obtained from the long-term observation records of Tianjin Meteorological Station (117°12′ E, 39°08′ N) [17]. Due to its proximity to the Bohai Sea, surface water and groundwater in the BWNR display brackish conditions with a significant spatial gradient along the land–sea direction [47]. Subsequently, vegetation in the area is dominated by two functionally distinct species: Phragmites australis (a perennial common reed with strong flooding endurance but low salinity tolerance) [17] and Suaeda salsa (an annual herbaceous halophyte with poor waterlogging tolerance) [4,24]. Soils in the study area are predominantly silty clay, characterized by low hydraulic permeability and high water-holding capacity [8].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

The most common ecosystem types in the BWNR include lakes, wetlands, rivers, crop lands, fishery ponds, forests, coastal mudflats, and built-up areas. In the early 2000s, extensive excavations commenced around the BWNR, which converted about 25% of the natural area to aquaculture ponds [17]. These activities significantly altered the topographic and hydrological conditions in the area, leading to deteriorated water quality and compromised ecosystem stability. Partly to protect and restore the BWNR’s ecosystem, a local conservation act (the Tianjin Permanent Ecological Protection Zone Management Regulations) was instituted in 2014, which prohibited industrial and agricultural activities in nature reserves and required ecological engineering such as hydrological connectivity restoration. This legislative action was also complemented by several ecological engineering projects in the BWNR, such as reconnecting fragmented drainage ditches into an integrated channel network. Due to recurrent drought in the region, the ecological water replenishments have been conducted annually as necessary, particularly in growing seasons, to ensure adequate water supplies for vegetation growth; however, its effectiveness is still under debate [5,17].

Given the substantial efforts invested in restoring the BWNR’s ecosystem, there is an urgent need to assess whether those efforts led to improved ES. Following [17], the study period was divided into three stages depending on the intensity of human activities and the enactment of key conservation policies: a low-disturbance stage (1984–1999), a high-disturbance stage (2000–2013), and a recovery stage (2014–2023). This temporal division allowed an evaluation of how long-term LULC changes, which were associated with human activities and key conservation policies in the BWNR, impacted ESVs, based on the LULC data from four benchmark years (1984, 2000, 2013, and 2023).

2.2. Methodological Framework

The methodological framework for this study is shown in Figure 2, with the key steps summarized below. First, the LULC in the BWNR was classified using data from Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper, Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus, and Landsat 8/9 Operational Land Imager available on the Google Earth Engine (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets) (accessed on 10 May 2025), including three visible, one near-infrared, two shortwave-infrared, and one quality assessment bands [65]. Due to its robustness in handling high-dimensional data with limited training samples [34,66,67], the support vector machine (SVM) method was employed to classify the LULC into vegetation, water bodies, built-up land, and bare land, with input variables including six reflectance bands and four spectral indices [17,68,69]. To train the SVM model, 545 ground truth data points were obtained from two field surveys in 2022 and 2023, with an additional 210 data points derived by interpreting high-resolution images from a DJI M300RTK unmanned aerial vehicle. Those data were randomly split into 70% and 30% for training and validating the SVM model, respectively. The model validation showed an overall accuracy of 0.865, illustrating the reliability of using the SVM model for classifying the LULC in the BWNR.

Figure 2.

Methodological flow chart of the study.

Figure 2.

Methodological flow chart of the study.

Figure 3.

LULC classification maps for different years.

Figure 3.

LULC classification maps for different years.

Figure 4.

ESVs of different LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 4.

ESVs of different LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

The trained SVM model was then used to determine the LULC in the peak growing seasons (August or September) of 1984, 2000, 2013, and 2023. The transition matrix was used to quantify the LULC changes (for example, from vegetation to water bodies) between different disturbance stages with the following equation [70].

where Sij is the areal change in the area of LULC from type i at the beginning to type j at the end of each period, and n is the total number of LULC types.

Figure 5.

Variations in the ESVs of different LULC types in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 5.

Variations in the ESVs of different LULC types in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 6.

ESVs of different ecosystem service functions in BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 6.

ESVs of different ecosystem service functions in BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 7.

Variations in ESVs of different functions in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 7.

Variations in ESVs of different functions in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Figure 8.

Intensity index of land use.

Figure 8.

Intensity index of land use.

The BTA was then used to quantify the ESVs in the BWNR with the classified LULC. Following [62,71], standard monetary coefficients (i.e., ESV per unit for each LULC type) were obtained from primary valuation studies [72,73] and adjusted based on the local conditions: referring to [43]’s ESV coefficient for Chinese ecosystems, the vegetation coefficient was derived from the weighted average of forest and grassland coefficients (weighted by area proposition of Phragmites australis and Suaeda salsa [74]. The adjusted coefficients used in this study are given in Table 1, which were applied to the classified LULC maps for the peak growing seasons of 1984, 2000, 2013, and 2023.

Table 1.

Annual average ecosystem service value per unit area for different LULC categories in China * (CNY/ha).

Table 1.

Annual average ecosystem service value per unit area for different LULC categories in China * (CNY/ha).

| Ecosystem Functions | Vegetation | Water | Bare Land | Built-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food production | 341.31 | 399.7 | 8.98 | 0 |

| Raw materials | 1500 | 264.97 | 17.96 | 0 |

| Gas regulation | 2613.76 | 1311.37 | 26.95 | 0 |

| Climate regulation | 2528.44 | 7010.46 | 58.38 | 0 |

| Hydrological regulation | 2519.45 | 14,465.51 | 31.44 | 0 |

| Waste treatment | 1365.26 | 13,136.18 | 116.77 | 0 |

| Soil retention | 2811.36 | 1077.84 | 76.35 | 0 |

| Biodiversity | 2865.26 | 3197.59 | 179.64 | 0 |

| Aesthetic value | 1324.85 | 4100.28 | 107.78 | 0 |

| Total | 17,869.69 | 44963.9 | 624.25 | 0 |

*: Values derived from [62].

The total ESV of the BWNR in each year was calculated with the following equation:

where ESV is the total ecosystem service value, is the area of land use type i (ha), is the value coefficient for ecosystem service f of land use type i, i is the land use/land cover type, and f is the ecosystem service function.

2.3. Analytic Metrics

Several analytic metrics were utilized in this study to examine the impact of the LULC changes on the ESV in the BWNR. These metrics help to quantify the LULC changes and assess their influences on ESVs, thereby reducing the estimation uncertainties. Moreover, since different LULC types contribute to different ES, applying such metrics enables a more precise valuation of an individual ESV, which in turn supports informed decision-making processes in land use management [75]. One of the key indicators is the LULC dynamic degree, which measures the rate and intensity of LULC changes over time, including single and comprehensive dynamic degrees [76]. Specifically, the single LULC dynamic degree is the change rate of a specific LULC type over time, with the following equation.

where LULCi is the degree to which a particular LULC unit changes during the study period i, LULCend year and LULCstar year represent the area of the LULC unit at its starting and ending times, respectively, and t denotes the estimation period. Thus, positive values represent an increase in LULC and vice versa.

Compared to the single dynamic degree, the comprehensive dynamic degree reflects the overall pattern of LULC changes within a specific region using the following equation [76].

where n is the number of the LULC types.

The percentage change in ESVs over time is useful for evaluating the impact of human activities and for guiding conservation and policy decisions [5,15]. It measures how much the benefits provided by nature decreased or increased during a certain period.

where ESVyear and ESVfinal are the ESV at the initial and final period, respectively.

The land use intensity is widely used to quantify the impacts of human activities on land during the conversion of the land for coastal developments [77]:

where the built-up area and total area are quantified, respectively.

The sensitivity coefficient is

where ESVk is the ecosystem service value of land use class k, and ESVtotal is the total ecosystem service value of the study area.

3. Results

3.1. The LULC Changes in the Study Area

Table 2 reveals notable changes in the LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023. Over the entire period, vegetation and bare land experienced substantial losses of 46.4% and 31.3%, respectively, while water bodies and built-up areas grew by 547.5% and 14.4%, respectively. Note that the LULC changes in the BWNR displayed varying trends in different disturbance stages. Specifically, from 1984 to 2000, the vegetation area increased from 4586.4 ha to 4780.6 ha, the water body area from 511.1 ha to 1439.3 ha, and the built-up area from 159.4 ha to 219.9 ha, and the bare land decreased from 2208.2 ha to 1024.8 ha (Table 2). Between 2000 and 2013, the vegetation area started decreasing, while the water body and bare land areas increased. Despite the conservation efforts, the vegetation area still suffered a loss from 2013 to 2023, while the water body, built-up, and bare land areas continued to expand.

Table 2.

Changes in the LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Table 2.

Changes in the LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

| LULC Class | Area (ha) | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 2000 | 2013 | 2023 | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | |

| Vegetation | 4586.4 | 4780.6 | 3514.3 | 2456.9 | 194.6 | 4.2 | −1266.3 | −26.5 | −1057.4 | −30.1 | −2129.1 | −46.4 |

| Water | 511.1 | 1439.3 | 2537.4 | 3309.4 | 928.2 | 181.6 | 1098.1 | 76.3 | 772.0 | 30.4 | 2798.3 | 547.5 |

| Built-up | 159.4 | 219.9 | 143.3 | 182.3 | 60.5 | 37.9 | −76.6 | −34.8 | 39.1 | 27.3 | 23.0 | 14.4 |

| Bare land | 2208.2 | 1024.8 | 1269.7 | 1516.1 | −1183.3 | −53.6 | 244.9 | 23.9 | 246.3 | 19.4 | −692.1 | −31.3 |

The single and comprehensive LULC dynamic degrees in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023 are summarized in Table 3, which reveals a clear trend in the LULC change. In particular, the vegetation cover experienced a persistent decline with a cumulative loss of 46.4% over four decades, likely due to the combined impacts of anthropogenic activities and climate change, whereas the expansion of water bodies suggested that water management (for example, ecological water replenishments) largely mitigated climatic constraints in the BWNR [17]. The rate of the LULC changes increased from 0.99% in the low-disturbance stage to 1.42% in the recovery stage, which indicated an acceleration in land modification in recent decades due to pond expansion and climate change. Vegetated areas are mainly converted into pond expansion, water bodies, built-up, bare land, and crop land. The transition matrix of the LULC in the BWNR is reported in Table 4.

Table 3.

Single and comprehensive LULC dynamic degrees in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Table 3.

Single and comprehensive LULC dynamic degrees in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

| Time | Single LULC Dynamic Degree (%) | Comprehensive LULC Dynamic Degree (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | Water | Built-Up | Bare Land | ||

| 1984–2000 | 4.24 | 181.60 | 37.94 | −53.59 | 0.99 |

| 2000–2013 | −26.49 | 76.29 | −34.83 | 23.90 | 1.38 |

| 2013–2023 | −30.09 | 30.43 | 27.26 | 19.40 | 1.42 |

| 1984–2023 | −46.43 | 547.50 | 14.40 | −31.34 | 0.97 |

Table 4.

Transition matrix of the LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Table 4.

Transition matrix of the LULC in the BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

| LULC Class | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | |

| Vegetation–Vegetation | 3322.26 | 44.51 | 2960.64 | 39.66 | 2070.72 | 27.74 | 2402.28 | 32.18 |

| Vegetation–Water | 875.61 | 11.73 | 1104.12 | 14.79 | 842.4 | 11.28 | 1570.14 | 21.03 |

| Vegetation–Built-up | 36.63 | 0.49 | 56.7 | 0.76 | 24.66 | 0.33 | 49.5 | 0.66 |

| Vegetation–Bare land | 351.54 | 4.71 | 659.16 | 8.83 | 576.54 | 7.72 | 564.12 | 7.56 |

| Water–Vegetation | 182.25 | 2.44 | 195.03 | 2.61 | 129.87 | 1.74 | 27.81 | 0.37 |

| Water–Water | 239.22 | 3.20 | 1121.67 | 15.03 | 2146.41 | 28.75 | 448.83 | 6.01 |

| Water–Built-up | 1.44 | 0.02 | 11.07 | 0.15 | 2.97 | 0.04 | 7.29 | 0.10 |

| Water–Bare land | 88.2 | 1.18 | 111.51 | 1.49 | 258.12 | 3.45 | 27.18 | 0.36 |

| Built-up–Vegetation | 12.78 | 0.17 | 49.32 | 0.66 | 9.09 | 0.12 | 3.87 | 0.052 |

| Built-up–Water | 42.03 | 0.56 | 26.82 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.007 | 64.62 | 0.87 |

| Built-up–Built-up | 43.38 | 0.58 | 36.09 | 0.48 | 54.18 | 0.73 | 26.64 | 0.36 |

| Built-up–Bare land | 61.2 | 0.82 | 107.64 | 1.44 | 79.47 | 1.06 | 64.26 | 0.86 |

| Bare land–Vegetation | 1263.33 | 16.92 | 309.24 | 4.14 | 247.23 | 3.31 | 1080.36 | 14.47 |

| Bare-land–Water | 282.42 | 3.78 | 284.76 | 3.81 | 320.04 | 4.29 | 453.78 | 6.08 |

| Bare land–Built-up | 138.42 | 1.85 | 39.42 | 0.53 | 100.53 | 1.35 | 59.85 | 0.80 |

| Bare land–Bare land | 523.89 | 7.02 | 391.41 | 5.24 | 601.92 | 8.06 | 614.16 | 8.23 |

| Total | 7464.6 | 100 | 7464.6 | 100 | 7464.69 | 100 | 7464.69 | 100 |

3.2. Temporal Patterns and Trends in ESVs

The total ESVs estimated for the BWNR in 1984, 2000, 2013, and 2023 are detailed in Table 5. In 1984, the total ESV was estimated at CNY 10,631.1 million with vegetation accounting for the largest contribution, followed by open water and bare land. By 2000, the total ESV increased to CNY 15,078.4 million, in which vegetation remained the largest contributor, followed by open water and bare land. The total ESV in 2013 reached CNY 17,768.3 million, with open water becoming the leading contributor, while the ESV from vegetation decreased to about half of that from open water. At the end of the study period in 2023, the total ESV further increased to CNY 19,365.37 million, with open water remaining the largest contributor, followed by vegetation and bare land.

Table 5.

ESVs of different LULC categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2013 (104 million CNY).

Table 5.

ESVs of different LULC categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2013 (104 million CNY).

| LULC Class | ESV ESVs (CNY Million) | ESV ESVs (CNY Million) Change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 2000 | 2013 | 2023 | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | |

| Vegetation | 8195.1 | 8542.8 | 6279.9 | 4390.4 | 347.7 | −2262.8 | −1889.6 | −3804.7 |

| Water | 2298.2 | 6471.6 | 11,409.1 | 14,880.3 | 4173.4 | 4937.5 | 3471.3 | 12,582.2 |

| Built-up | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bare land | 137.8 | 63.9 | 79.3 | 94.6 | −73.9 | 15.3 | 15.4 | −43.2 |

| Total | 10,631.1 | 15,078.4 | 17,768.3 | 19,365.4 | 4447.3 | 2689.9 | 1597.1 | 8734.3 |

Table 6 presents the estimated values of specific ecosystem service functions (ESVf) in the BWNR between 1984 and 2023, which reveals considerable temporal variations in ESVf over the study period. Hydrological regulation, climate regulation, biodiversity conservation, soil retention, waste treatment, and gas regulation contributed the most ESVf to the total ESV, while raw materials and food production contributed the most to the total ESV in 1984. In 2000, the leading ESVf shifted to water treatment and hydro-regulation, while raw material and food production remained the lowest ESVf. A similar pattern still held in 2013 and 2023, with hydro-regulation contributing the most ESVf. Notably, some of the ESVf showed consistent growth over the study period; however, soil retention, raw materials, and biodiversity experienced negative or unsteady changing rates after 2000. In particular, the ESVf of raw materials, soil retention, and regulation diminished far more than other ESVf (Table 6). This was partly attributed to the expansion of aquaculture land for food production, particularly during the high-disturbance stage. For instance, the land use intensity index increased from 2.14% in 1984 to 2.95% in 2000, although it decreased to 1.85% in 2013 and 2.21% in 2023.

Table 6.

ESVs of different ecosystem service functions in BWNR from 1984 to 2023 (104 CNY).

Table 6.

ESVs of different ecosystem service functions in BWNR from 1984 to 2023 (104 CNY).

| Ecosystem Functions | ESVs (104 Million CNY) | ESVs (104 Million CNY) Changes in Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 2000 | 2013 | 2023 | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | |

| Food Production | 178.94 | 221.62 | 222.51 | 217.50 | 42.68 | 0.89 | −5.01 | 38.56 |

| Raw Materials | 705.41 | 757.07 | 596.66 | 458.98 | 51.66 | −160.41 | −137.68 | −246.43 |

| Gas Regulation | 1271.66 | 1441.04 | 1254.72 | 1080.25 | 169.38 | −186.32 | −174.47 | −191.41 |

| Climate Regulation | 1530.76 | 2223.74 | 2674.80 | 2950.10 | 692.98 | 451.06 | 275.3 | 1419.34 |

| Hydro-Regulation | 1901.72 | 3289.67 | 4559.84 | 5410.97 | 1387.95 | 1270.17 | 851.13 | 3509.25 |

| Waste Treatment | 1323.30 | 2555.31 | 3827.76 | 4700.41 | 1232.01 | 1272.45 | 872.65 | 3377.11 |

| Soil Retention | 1361.25 | 1506.96 | 1271.18 | 1059.00 | 145.71 | −235.78 | −212.18 | −302.25 |

| Biodiversity | 1517.12 | 1848.40 | 1841.10 | 1789.41 | 331.28 | −7.3 | −51.69 | 272.29 |

| Aesthetic Value | 840.95 | 1234.55 | 1519.67 | 1698.79 | 393.6 | 285.12 | 179.12 | 857.84 |

| Total | 10,631.11 | 15,078.36 | 17,768.24 | 19,365.41 | 4447.25 | 2689.88 | 1597.17 | 8734.3 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Driving LULC Dynamics

During the study period, the BWNR experienced significant LULC changes, particularly in the high-disturbance (2000–2013) and recovery (2013–2023) stages, where vegetated areas were converted to open water and bare land (1266.3 ha and 1057.4 ha of vegetation lost, respectively (Table 4). This was mainly due to human activities, excavating agricultural ponds in the BWNR [17]. Interestingly, after the implementation of the conservation act, vegetated areas were still converted to open water and bare land.

Moreover, climate change may have further contributed to these transitions. Importantly, there was no evidence of urbanization within the study area throughout the observation period.

4.2. Impact of LULC Changes on ESVs

It is well established that LULC changes are among the main factors driving ESV fluctuations, as they alter the condition and function of ecosystems, thereby influencing the services they deliver [78,79]. Globally, urbanization increase, industrialization, and agricultural expansion diminish global ecosystem services [80,81] and cost the globe more than USD 6.3 trillion [80,82].

Our estimates showed that the total ESV in the BWNR increased from CNY 10,631.1 million in 1984 to 19,365.4 million in 2023, with a cumulative increase of CNY 8734.3 million; the observed positive trend in total ESV flow is consistent with the findings of [83] but differs from [84] who reported a decrease of 28.82% in global total terrestrial ecosystem services value and found a decline in the total annual ecosystem service value, but our results are consistent with the findings from [85].

The increase in water bodies is the most relevant LULC class contributing to the growth in total ESV. Although the ESV (raw materials, gas regulation, soil retention, and biodiversity) showed a significant decline over the study period, the proportion of ESV growth attributable to water bodies has gradually increased over the past three decades (Table 8).

Table 7.

ESVs of different LULC categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2023 (104 CNY).

Table 7.

ESVs of different LULC categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2023 (104 CNY).

| LULC Class | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | |

| Vegetation | 347.71 | 4.24 | −2262.84 | −26.49 | −1889.56 | −30.09 | −3804.69 | −46.43 |

| Water | 4173.41 | 181.60 | 4937.45 | 76.29 | 3471.3 | 30.43 | 12,582.16 | 547.50 |

| Built-up | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bare land | −73.86 | −53.58 | 15.28 | 23.88 | 15.38 | 19.40 | −43.2 | −31.34 |

| Total | 4447.26 | 132.26 | 2689.89 | 73.68 | 1597.12 | 19.74 | 8734.27 | 469.73 |

Table 8.

Annualized ESV change rates (104CNY/yr).

Table 8.

Annualized ESV change rates (104CNY/yr).

| LULC Class | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (104 CNY/yr) | (104 CNY/yr) | (104 CNY/yr) | (104 CNY/yr) | |

| Vegetation | 21.73 | −174.06 | −188.96 | −97.56 |

| Water | 260.84 | 379.80 | 347.13 | 322.62 |

| Built-up | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bare land | −4.62 | 1.18 | 1.54 | 1.11 |

| Total | 277.96 | 206.91 | 159.71 | 223.96 |

Table 9.

Variations in ESVs of different land use/land cover categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

Table 9.

Variations in ESVs of different land use/land cover categories in BWNR from 1984 to 2023.

| Ecosystem Functions | 1984–2000 | 2000–2013 | 2013–2023 | 1984–2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | ESVs (104 CNY) | % | |

| Food Production | 42.68 | 23.85 | 0.89 | 0.40 | −5.01 | −2.25 | 38.56 | 21.55 |

| Raw Materials | 51.66 | 7.32 | −160.41 | −21.19 | −137.68 | −23.08 | −246.43 | −34.933 |

| Gas Regulation | 169.38 | 13.32 | −186.32 | −12.93 | −174.47 | −13.91 | −191.41 | −15.05 |

| Climate Regulation | 692.98 | 45.27 | 451.06 | 20.28 | 275.3 | 10.29 | 1419.34 | 92.72 |

| Hydrological Regulation | 1387.95 | 72.99 | 1270.17 | 38.61 | 851.13 | 18.67 | 3509.25 | 184.53 |

| Waste Treatment | 1232.01 | 93.10 | 1272.45 | 49.80 | 872.65 | 22.80 | 3377.11 | 255.20 |

| Soil Retention | 145.71 | 10.70 | −235.78 | −15.65 | −212.18 | −16.69 | −302.25 | −22.20 |

| Biodiversity | 331.28 | 21.84 | −7.3 | −0.39 | −51.69 | −2.81 | 272.29 | 17.95 |

| Aesthetic Value | 393.6 | 46.80 | 285.12 | 23.10 | 179.12 | 11.79 | 857.84 | 102.00 |

| Total | 4447.25 | 335.19 | 2689.88 | 82.03 | 1597.17 | 4.81 | 8734.3 | 601.77 |

Table 10.

Sensitivity coefficients of ecosystem service values for different LULC classes in BWNR from 1984 to 2013.

Table 10.

Sensitivity coefficients of ecosystem service values for different LULC classes in BWNR from 1984 to 2013.

| LULC Classes | 1984 | 2000 | 2013 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.23 |

| Water | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.77 |

| Built-up | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bare land | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

The degradation caused by human activities can limit the capacity of ecosystem service functions [86,87]. Due to the historical degradation from urbanization, agriculture [41], and industrial activities, the Chinese government and local authorities have implemented a series of conservation policies to restore and protect the wetlands [88,89]. The conservation policies have demonstrated relative progress in balancing ecological protection and sustainable development. However, their long-term success depends on adaptive management and increased funding. The analysis reveals a consistent increase in most ecosystem service functions across the study period, demonstrating the effectiveness of recent conservation interventions in the region. Some ecosystem service functions have dropped; the observed degradation in ecosystem services is primarily attributed to LULC transformations, particularly the conversion of vegetation to water bodies, built-up, and bare land. Vegetation has a vital role in performing essential functions in regulating climate through carbon sequestration, mitigating the effects of climate change, and preserving biodiversity. Climate change affects vegetation due to rising sea levels [90], as it tends to wash away the coastal vegetation, leading to coastal erosion. Vegetation plays a crucial role in soil conservation by preventing erosion and increasing soil fertility [23]. It is important to protect vegetation because of its positive contribution to ESV and its capacity to ensure long-term environmental health and resilience. The analysis reveals significant declines across functions, ecosystem services, food production, raw materials, gas regulation, soil retention, and biodiversity, which are largely affected during the stipulated periods (Table 8). The compounding effects of industrial effluent discharge, coupled with intensified agricultural runoff from chemical fertilizers and pesticides into water bodies, have accelerated ecosystem service degradation [71]. Vegetation has a vital role in performing essential functions in regulating climate through carbon sequestration, mitigating the effects of climate change, and preserving biodiversity. Vegetation plays a crucial role in soil conservation by preventing erosion, increasing soil fertility, and maintaining water quality, also contributing in a positive way to ESV to ensure long-term environmental health and resilience.

4.2.1. The Low-Disturbance Stage (1984–2000)

The LULC during this period was relatively stable in BWNR, primarily as a result of limited anthropogenic pressures and moderate climate variability. This period reflected low-intensity human land use, as there was limited aquaculture expansion, and the coastal wetlands maintained natural hydrology due to a low human population density and the absence of large-scale infrastructure. Consistent with land use stability, the sensitivity analysis shows that ecosystem service values were dominated by vegetation during this period, with a high sensitivity coefficient (CS = 0.77 in 1984), indicating that vegetated wetlands were the primary contributors to the total ecosystem service value. The relatively low sensitivity of water bodies (CS = 0.22) further suggests that aquatic ecosystems played a secondary role in regulating ecosystem services. Overall, the low variability in sensitivity coefficients during this period reflects a stable ecosystem structure, in which changes in the total ESV were largely controlled by natural land cover components rather than human-induced land use transformations. Coastal wetlands in China did not experience intensive disturbance until the late 1990s with rapid urbanization [4], which is consistent with BWNR entering the high-disturbance stage after 2000, during which aquaculture pond excavation led to significant vegetation loss (Table 2).

4.2.2. The High-Disturbance Stage (2000–2013)

This period recorded significant ecological degradation in BWNR, dominated by intensified anthropogenic pressures and climate change variability. Rapid economic development led to wetland conversion [91] and vegetation losses, where over 50% of the natural wetlands were lost, due to hydrological alterations [38,92]. According to [49], anthropogenic activities cause LULC changes, while unplanned land use practices have precipitated a decline in the wetland area extent [93]. Rapid urbanization reduces the ecosystem service value [80,91,94]. The decrease in vegetation was primarily attributed to urbanization and climate change [95], industrialization [96,97], and the establishment of aquaculture ponds [98]. The sensitivity analysis provides additional insight into how changes in land use lead to ecosystem service losses. The sensitivity coefficient of vegetation declined, reflecting the reduced contribution of vegetated wetlands to the total ecosystem service value, as their spatial extent decreased. The sensitivity coefficient of water bodies increased, indicating a growing dependence of the total EVS on aquatic ecosystems, following the conversion of vegetated wetlands to open water and aquaculture systems.

LULC changes may increase the area of natural wetlands when farmland is abandoned [99,100]. Climate change, combined with population, led to wetland degradation [96]. Climate change affects rainfall and temperature [24], which affect vegetation growth and soil biochemical properties [101]. In Virginia, the rise in sea levels resulted in the loss of coastal marshes [102,103]. According to [38], invasive species decrease vegetation and often outcompete native species, thus affecting the ESV.

4.2.3. Recovery Stage (2013–2023)

Enhancing the protection and recovery of coastal wetland resources requires raising public awareness about the ecological value of the wetlands, which is necessary for the assessment of the value provided by the wetland [80,104]. Balancing economic growth with environmental protection prevents excessive urban expansion, to ensure cities develop sustainably and scientifically. From 2000 to 2013, the BWNR served as a home for migratory birds along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. Recognizing the ecological and economic importance of these wetlands, the Tianjin municipal government introduced conservation measures in 2013 to address the habitat loss, water scarcity, and biodiversity decline as the city aligned its policies with the National Wetland Conservation Program (2014–2020) and the Ecological Civilization framework. The Tianjin municipal government strengthened the legal protections, eco-compensation schemes, and restoration projects [88]. These efforts demonstrated how innovation could balance ecological protection with economic development in rapid urbanization zones. Sensitivity analysis indicates that the contribution of vegetated wetlands to the total ESV stabilized, with a modest decline in the sensitivity coefficient, while the dominance of water bodies continued to increase. Furthermore, the built-up area decreased, primarily due to policies implementation by the Tianjin government during this period. However, persistent challenges, including inconsistent enforcement, economic priorities, funding, and climate change pressures, revealed the limitations of these initiatives. Effective wetland conservation will require stronger governance integration and climate-adaptive management.

5. Conclusions

Our findings provide evidence that anthropogenic and climate change on the BWNR have resulted in a change in LULC over the past thirty-nine years, which has experienced continuous expansion, with the most significant growth occurring between 1984 and 2000 and a decrease in vegetation from 2000 to 2013. The observed large-scale LULC transformations were driven by rapid socioeconomic development, coupled with escalating demands for infrastructure, industrialization, and aquaculture ponds for food production. Notable is the rate of vegetation loss over time; however, the built-up area decreased throughout the study period, which may reflect the efficacy of policy interventions. The impact of the conservation and restoration policies showed positive effects [105]. Sensitivity analysis further clarifies the ecosystem service implications of the land cover dynamics. The sensitivity coefficient of vegetation declined steadily, indicating a reduced contribution of vegetated areas to the total ESV, while the sensitivity of water bodies increased, reflecting their growing dominance in ecosystem service provision.

According to our findings, the water bodies’ ecosystem service value increased by about CNY 12,582.16 million (547.50%) (1984–2023). Together, the total areas of vegetation and bare land dropped by CNY −3804.69 million (46.43%) and CNY −43.2 million (31.34%), respectively. The substantial increase in water bodies and decline in vegetation may result in a decline in ecosystem services and functions (e.g., soil retention, raw materials, and gas regulation. To mitigate ongoing ecosystem degradation and associated declines in ecosystem services, policymakers must address the primary drivers (the rapid expansion of built-up areas) occurring at the expense of vegetation ecosystem degradation and losses of ecosystem service values, specifically. Based on the area proportion (7:3) of Phragmites australis (herb) and Suaeda salsa (shrub), we derived the comprehensive vegetation coefficient using the weighted average of grassland and shrubland ESV coefficients from [43]. Our findings thus set the stage for further research into predicting future LULC dynamics of ecosystem service value. This will involve utilizing remote sensing observations, modeling land suitability analysis, and assessing the vegetation restoration status. We recommend prioritizing a focus on the sustainable management of ecology and social economy, which involves urban planning that balances ecological preservation with socioeconomic development, reducing the negative impacts of human activities on the ecological landscape.

Limitations of This Study

This study analyzed historical LULC changes and estimated ecosystem service values using multi-temporal Landsat imagery. However, remote sensing data present certain limitations. We used a benefit transfer approach to evaluate the ESV in BWNR and employed the coefficient value as refined by [62]. In our study (Table 1), we adjusted the coefficient values by combining the forest coefficient value and the grassland coefficient value to derive the vegetation coefficient value for a more accurate representation of the ecological balance within BWNR. Furthermore, by standardizing these coefficients, we aimed to enhance the reliability of our findings and contribute to more effective environmental management strategies. We also aggregated the wetlands, rivers, or lakes to quantify the water bodies. For bare land, we retained the existing values. This comprehensive approach provides an understanding of land use dynamics [76] and a framework for future research. To better assess the impacts of climate change and human activities on local ecosystems, future studies should further quantity the independent contributions of climate factors (e.g., precipitation and temperature changes) and human activities (e.g., aquaculture and ecological water replenishment) and predict the evolution trend of wetland ESV through scenario simulation.

Author Contributions

M.M.R.B.E.: Writing, review & editing original draft, Validation, Software, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Q.B.: Investigation, Data curation, T.W.: Writing, review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, A.Y.: Writing, review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (24ZYJDJC00340). Tiejun Wang also acknowledges the financial support from Tianjin University. Additional support was provided by the Peiyang Future Scholar Scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Lai, C.; Wu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, X.; Lian, Y. Rapid urbanization impacts on ecosystem services in China’s coastal wetlands: A case study of Beidagang. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolessa, T.; Senbeta, F.; Kidane, M. The impact of land use/land cover change on ecosystem services in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowolo, A.O.; Deng, X.Z.; Olatunji, O.A.; Obayelu, A.E. Assessing changes in the value of ecosystem services in response to land-use/land-cover dynamics in Nigeria. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. The role of ecosystem services in sustainable urban development: A case study from Nanjing, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1743. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Han, C.; Tang, F.; Li, Z.; Tian, H.; Huang, Z.; Ma, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; et al. Potential Impacts of Land Use Change on Ecosystem Service Supply and Demand under Different Scenarios in the Gansu Section of the Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkovic, D.M.; Mitchell, M.; Mason, P.; Duhring, K. The Role of Living Shorelines as Estuarine Habitat Conservation Strategies. Coast. Manag. 2016, 44, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.M.; Wagtendonk, A.J.; Hussain, S.S.; McVittie, A.; Verburg, P.H.; De Groot, R.S.; Van der Ploeg, S. Ecosystem service values for mangroves in Southeast Asia: A meta-analysis and value transfer application. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Bai, J.; Huang, L.; Gu, B.; Lu, Q.; Gao, Z. A review of methodologies and success indicators for coastal wetland restoration. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, B.; Malavika, C. Biodiversity and its conservation in the Sundarban mangrove ecosystem. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 68, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.W.; Cormier, N.; Osland, M.J. Created mangrove wetlands store belowground carbon and surface elevation change enables them to adjust to sea-level rise. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Sergio, F.; Yongxue, L. Classification mapping of salt marsh vegetation by flexible monthly NDVI time-series using Landsat imagery. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 213, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; He, Q.; Gu, B.; Bai, J.; Liu, X. China’s Coastal Wetlands Understanding Environmental Changes and Human Impacts for Management and Conservation. Wetlands 2016, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Min, S.; Wenyan, X.; Jingyi, P. Integrating ecosystem service value in the disclosure of landscape ecological risk changes: A case study in Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2024, 30, 326–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.; Kaplan, D. Restore or retreat? Saltwater intrusion and water management in coastal wetlands. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2017, 3, e01258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.C.; Heggerud, C.M.; Lai, Y.; Morozov, A.; Petrovskii, S.; Cuddington, K.; Hastings, A. When and why ecological systems respond to the rate rather than the magnitude of environmental changes. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 292, 110494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, P.; Wilson, A.; Shen, C.; Ge, Z.; Moffett, K.B.; Santos, I.R.; Chen, X. Surface water and groundwater interactions in salt marshes and their impact on plant ecology and coastal biogeochemistry. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Wang, T.; Han, Q.; Li, X. Vegetation dynamics induced by climate change and human activities: Implications for coastal wetland restoration. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 384, 125594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, G.; Ouyang, N.; Mu, F.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X. Analyzing Coastal Wetland Degradation and its Key Restoration Technologies in the Coastal Area of Jiangsu, China. Wetlands 2018, 38, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, C.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, H. Estimation of carbon storage in coastal wetlands and comparison of different management schemes in South Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 43, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowolo, A.O.; Xiangzheng, D. Land use/land cover change and statistical modelling of cultivated land change drivers in Nigeria, Regional. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huahui, L.; Aoke, C.; Jiao, C.; Shuo, Z.; Yaning, C. Ecosystem Service Evaluation and Influencing Factors Based on Production-Living-Ecological Spaces: A Case Study of the Lower Yellow River. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 34, 7993–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, C.L.; Osland, M.J.; Moon, J.A.; Hall, C.T.; Feher, L.C.; Jones, W.R.; Couvillion, B.R.; Hartley, S.B.; Vervaeke, W.C. Quantifying hydrologic controls on local- and landscape-scale indicators of coastal wetland loss. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Zhang, T.; He, F.; Zhang, W. Assessing and simulating changes in ecosystem service value based on land use/cover change in coastal cities: A case study of Shanghai, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Rivera-Ocasio, E.; Heartsill-Scalley, T.; Davila-Casanova, D.; Rios-López, N.; Gao, Q. Landscape-Level Consequences of Rising Sea-Level on Coastal Wetlands: Saltwater Intrusion Drives Displacement and Mortality in the Twenty-First Century. Wetlands 2019, 39, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Huaqiang, D.; Guomo, Z.; Mengchen, H.; Zihoa, H. The Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Evolutionary Relationship between Urbanization and Eco-Environmental Quality: A Case Study in Hangzhou City, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitoka, E.; Maria, T.; Lena, H.; Apostolakis, A.; Höfer, R.; Weise, K.; Ververis, C. Water-related ecosystems’ mapping and assessment based on remote sensing techniques and geospatial analysis: The SWOS national service case of the Greek Ramsar sites and their catchments. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 245, 111795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.L.; Friess, D.A.; Krauss, K.W.; Cahoon, D.R.; Guntenspergen, G.R.; Phelps, J. A global standard for monitoring coastal wetland vulnerability to accelerated sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutwell, J.L.; Westra, J.V. Benefit Transfer: A Review of Methodologies and Challenges. Resources 2013, 2, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, B.; Singh, S. Assessment of ecosystem services should be based on ecosystem functions and processes: Comments on Das et al. 2019. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guild, R.; Wang, X.; Pedro, A.Q. Climate change impacts on coastal ecosystems. Environ. Res. Clim. 2025, 3, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Krauss, K.W.; Horstman, E.M.; Balke, T.; Bouma, T.J.; Galli, D.; Webb, E.L. Webb Are all intertidal wetlands naturally created equal? Bottlenecks, thresholds and knowledge gaps to mangrove and saltmarsh ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes-Cornell, A.; Grose, S.O.; Pendleton, L. Pendleton Mangrove ecosystem service values and methodological approaches to valuation: Where do we stand? Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Yang, Q. Impacts on Wetlands of Large-scale Land-use Changes by Agricultural Development: The Small Sanjiang Plain, China. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2004, 33, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Lizhou, W.; Yingge, W.; Bowen, Z.; Qi, J.; Jianxin, Y. Disagreements in Equivalent-Factor-Based Valuation of County-Level Ecosystem Services in China: Insights from Comparison among Ten LULC Datasets. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Li, S.; Zhongqiu, S.; Yafei, W.; Yuxia, W. Understanding urban growth in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region over the past 100 years using old maps and Landsat data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bellerby, R.; Craft, C.; Widney, S.E. Coastal wetland loss, consequences, and challenges for restoration. Anthr. Coasts 2018, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, X.; Song, B.; Wang, C. Assessing and predicting changes in ecosystem service values based on land use/cover change in the Bohai Rim coastal zone. Ecol. Indicat. 2020, 111, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, M.L. Assessing benefit transfer for the valuation of ecosystem services. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, T.; Han, Q. Salinity effects on soil structure and hydraulic properties: Implications for pedotransfer functions in coastal areas. Land 2024, 13, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Costanza, R.; Troy, A.; D’Aagostino, J.; Mates, W. Valuing New Jersey’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital: A Spatially Explicit Benefit Transfer Approach. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xie, B.; Degang, Z. Spatial–temporal evolution of ESV and its response to land use change in the Yellow River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.-D.; Lin, Z.; Chun-xia, L.U.; Yu, X.; Cao, C. Expert knowledge-based valuation method of ecosystem services in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 23, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Lyu, Y.; Chen, C.; Choguill, C. Environmental deterioration in rapid urbanisation: Evidence from assessment of ecosystem service values in Wujiang, Suzhou. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C. Urbanization: Processes and driving forces. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhind, S.M. Anthropogenic pollutants: A threat to ecosystem sustainability? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Han, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Bai, Q.; Li, X. Spatial Variability in Soil Hydraulic Properties under Different Vegetation Conditions in a Coastal Wetland. Land 2025, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba Hernández, R.; Camerin, F. The application of ecosystem assessments in land use planning: A case study for supporting decisions toward ecosystem protection. Futures 2024, 161, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šabić, D.; Vujadinović, S.; Stojković, S.; Djurdjić, S. Urban development consequences on the wetland ecosystems transformations—Case study: Pančevački Rit, Serbia. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2018, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, Y.V.; Quintana, R.D.; Radeloff, V.C.; Cavier-Pizarro, G.I. Wetland loss due to land use change in the Lower Paraná River Delta, Argentina. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadier, C.; Bayraktarov, E.; Piccolo, R.; Adame, M.F. Indicators of Coastal Wetlands Restoration Success: A Systematic Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 600220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; Chen, J.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C. Spatiotemporal Pattern Analysis of Land Use Functions in Contiguous Coastal Cities Based on Long-Term Time Series Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of Bohai Sea Region, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Identification of land use conflicts in China’s coastal zones: From the perspective of ecological security. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wanghe, K.; Jiang, H.; Ahmad, S.; Zhang, D. Construction of green infrastructure networks based on the temporal and spatial variation characteristics of multiple ecosystem services in a city on the Tibetan Plateau: A case study in Xining, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shuhua, M. A Quantitative Analysis on the Coordination of Regional Ecological and Economic Development Based on the Ecosystem Service Evaluation. Land 2024, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, M.; Alain, N.R.; Monique, P. Mapping wetlands and land cover change with landsat archives: The added value of geomorphologic data: Cartographie de la dynamique spatio-temporelle des milieux humides à partir d’archives Landsat: La valeur ajoutée de données géomorphologiques. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 44, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsi, M.; Malaviya, S.; Oinam, G. A landscape approach for quantifying land-use and land-cover change (1976–2006) in middle Himalaya. Reg. Environ. Change 2010, 10, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, D.; Thomas, E.; Jessica, L.; Rochelle, D.; Donald, E.; Dennis, F. Impacts of coastal land use and shoreline armoring on estuarine ecosystems: An introduction to a special issue. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Perillo, G.M.; Turner, R.E.; Ashan, D.; Cragg, S.; Luo, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Anthropogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 512636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Wainger, L.A. Benefit Transfer for Ecosystem Service Valuation: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. In Benefit Transfer of Environmental and Resource Values; Johnston, R., Rolfe, J., Rosenberger, R., Brouwer, R., Eds.; The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiayi, Z.; Oleg, G. Edge-urbanization: Land policy, development zones, and urban expansion in Tianjin. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Jianzhong, Z.; Lu, C.; Benjun, J.; Na, S.; Mengqi, T.; Guohua, H. Land use pattern and vegetation cover dynamics in the Three Gorges Reservoir (TGR) intervening basin. Water 2020, 12, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Xiujuan, S.; Yunlong, C.; Miao, L.; Jiajia, L.; Xianshi, J. Variations in fish habitat fragmentation caused by marine reclamation activities in the Bohai coastal region, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Man, W.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zheng, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Estimation of soil organic carbon content in coastal wetlands with measured VIS-NIR spectroscopy using optimized support vector machines and random forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yu, X.; Xia, S.; Zhang, G. Waterbird habitat loss: Fringes of the Yellow and Bohai Seas along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4174–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bin, Z.; Weidong, M.; Mingyue, L. Landsat-based monitoring of the heat effects of urbanization directions and types in Hangzhou City from 2000 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Das, A. Wetland conversion risk assessment of East Kolkata Wetland: A Ramsar site using random forest and support vector machine model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzì, L.; Marino, M.; Stagnitti, M.; Di Stefano, A.; Sciandrello, S.; Cavallaro, L.; Foti, E.; Musumeci, R. Impact of coastal land use on long-term shoreline change. Ocean Coast. 2025, 262, 107583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, V. Water Quality, Air Pollution, and Climate Change: Investigating the Environmental Impacts of Industrialization and Urbanization. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, S.; David Simpson, R.; Matthew Massey, D.; Heberling, M.T.; Wheeler, W.; Corona, J.; Hewitt, J. Benefit Transfer Challenges: Perspectives from U.S. Practitioners. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 69, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y. Exploring the threshold of human activity impact on urban ecosystem service value: A case study of Hefei, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Gu, Y.; Luo, M.; Lu, Z.; Wei, M.; Zhong, J. Shifts in bird ranges and conservation priorities in China under climate change. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeltner, K.; Boyle, K.J.; Paterson, R.W. Meta-analysis and benefit transfer for resource valuation-addressing classical challenges with Bayesian modeling. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 53, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.M.; Van Beukering, P.; Cesar, H.S.J. The recreational value of coral reefs: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Miao, H. Ecosystem service assessment for integrated land-use management in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 101, 105115. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Hong, W.; Wu, C. An improved dynamic evaluation model and land ecosystem service values for Fuzhou City. Resour. Sci. 2013, 53, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, W.R.; Brandon, K.; Brooks, T.M.; Costanza, R.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Portela, R. Global Conservation of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. BioScience 2007, 57, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, Y.; Ruiliang, P.; Yongchao, L. A review on anthropogenic geomorphology. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Aroloye, O.N.; Gerardo, R.C. Long term changes in mangrove landscape of the Niger River Delta, Nigeria. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 12, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, S.M.; K, R. Random Forest and support vector machine classifiers for coastal wetland characterization using the combination of features derived from optical data and synthetic aperture radar dataset. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Duan, L. The Bohai Sea. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Jiang, J. Spatial–Temporal Dynamics of Wetland Vegetation Related to Water Level Fluctuations in Poyang Lake, China. Water 2016, 8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Valdez, V.; Ruiz-Luna, A.; Ghermandi, A.; Nunes, P.A.L.D. Valuation of ecosystem services provided by coastal wetlands in northwest Mexico. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 78, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Cheng, H. Impact of Land Use Change on the Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Service Values in South China Karst Areas. Forests 2023, 14, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, V.V.; Ruiz-Luna, A.; Berlanga-Robles, A.C. Effects of Land Use Changes on Ecosystem Services Value Provided by Coastal Wetlands: Recent and Future Landscape Scenarios. J. Coast Zone Manag. 2016, 19, 418. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Jinfang, C.; Si, Z.; Xiaohui, X.; Shaoliang, Z.; Jun, Z.; Ying, Z. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Driving Factors of Ecosystem Service Value in a Fragile Hilly Area of North China. Land 2022, 11, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat, A.; Wang, J.; Aimaiti, M.; Saydi, M. Correction: Mamat et al. Evolution and Driving Forces of Ecological Service Value in Response to Land Use Change in Tarim Basin, Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2311, Correction in Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Liu, Y.X.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Xu, W.; Zhao, B. Trajectory of coastal wetland vegetation in Xiangshan Bay, China, from image time series. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Feng, B.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, R.; Li, M. An assessment of the Ecological Conservation Redline: Unlocking priority areas for conservation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 67, 1034–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuai, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, M.; Wu, C. Land use, total carbon emissions change and low-carbon land management in Coastal Jiangsu, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Webb, E.L. Variability in mangrove change estimates and implications for the assessment of ecosystem service provision. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Zhen, G.N.; Xiao, C.; Kui, Y.Z.; De, M.Z.; Jian, H.G.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.F.; Li, D.D.; Huang, H.B.; et al. China’s wetland change (1990–2000), determined by remote sensing. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 53, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Barchiesi, S.; Beltrame, C.; Finlayson, C.M.; Galewski, T.; Harrison, I.; Paganini, M.; Perennou, C.; Pritchard, D.E.; Rosenqvist, A.; et al. State of the World’s Wetlands and Their Services to People: A Compilation of Recent Analyses; Ramsar Briefing Note No. 7; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Deng, X. Land-use/land-cover change and ecosystem service provision in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilkovic, D.M.; Benson, G.; Scheld, A.M.; Isdell, R.; Mason, P.; Stafford, S.; Mitchel, M.; Gonzalez-Dorantes, C.; Chambers, R.; Leu, M.; et al. Valuing present and future benefits provided by coastal wetlands and living shorelines. Nat.-Based Solut. 2025, 8, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Balancing Water Ecosystem Services: Assessing Water Yield and Purification in Shanxi. Water 2023, 15, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Chen, L. The role of ecosystem services in the sustainable management of coastal zones: A review. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Darmawan, S.; Sari, D.K.; Wikantika, K.; Tridawati, A.; Hernawati, R.; Sedu, M.K. Identification before-after forest fire and prediction of mangrove forest based on Markov-cellular automata in part of Sembilang national park, Banyuasin, South Sumatra, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhrachy, I. Flash flood hazard mapping using satellite image and GIS tools: A case study of Najran city, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia KSA. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2015, 18, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Weiguo, J.; Wenjie, W.; Zhifeng, W.; Yinghui, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Wetland loss identification and evaluation based on landscape and remote sensing indices in Xiong’an new area. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, H.; Kareiva, P. Ecosystem services. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, R746–R748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; Van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.P.; Anderson, J.S.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I. The ecological economics of land degradation: Impacts on ecosystem service values. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.D.; Wang, Y. High-resolution mapping of tidal wetlands using Sentinel-2 imagery: Challenges and solutions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, K. Evaluating the ecological performance of wetland restoration in the Yellow River Delta, China. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 1090–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.