Abstract

Rapid urbanization threatens soil biodiversity and ecosystem functions, but the structural and physiological adaptations of soil microorganisms to urbanization remain unclear. We examined variations in soil microbial biomass, community structure and membrane lipid composition along an urban–suburban–exurban gradient in Guangzhou, China, using phospholipid fatty acid analysis. Samples were collected from four to five quadrats per site at three depths during dry and wet seasons. PERMANOVA revealed that both the urbanization gradient and the soil depth significantly shaped microbial communities. Depth was the strongest driver, explaining 45.5% of the variance in total microbial biomass, while site explained 27.2%. Microbial biomass decreased from exurban to urban sites and from surface to deep soils. Concurrently, the ratios of fungi/bacteria and Gram-positive/Gram-negative bacteria increased in urban areas and deeper soils. Physiologically, the membrane lipids shifted toward more saturated fatty acids in urban and surface soils, while unsaturated fatty acids predominated in exurban and deeper layers. These shifts in microbial community structure and membrane lipid composition were strongly correlated with key soil properties, including soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and bulk density. The findings demonstrate urbanization diminishes microbial biomass and triggers adaptive microbial responses, providing a scientific basis for the sustainable management of urban forests.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of urbanization, environmental challenges such as the heat island effect, biodiversity loss and habitat fragmentation have become increasingly prominent, leading to soil degradation, heavy metal pollution, and alterations in soil structure and quality, all of which can consequently influence the ecosystem services and functions of urban forests [1,2,3]. Soil microbiota constitute a large part of belowground biodiversity [4,5] and play pivotal roles in multiple ecosystem functions such as organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, and pollutant detoxification [6,7]. Soil microbial communities are highly sensitive to environmental changes, making them ideal bioindicators for assessing soil health and ecosystem stability under urban stress [8,9]. Therefore, evaluating microbial responses to urbanization-induced environmental gradients is central to understanding the ecological resilience and sustainability of urban forests.

The sensitivity of soil microbial communities to urbanization has been documented in numerous studies, but the results are controversial [10,11]. For instance, some studies have reported that urbanization increased soil microbial biomass, diversity, and metabolic activity in urban areas relative to suburban or rural regions [9,12]. In contrast, others have demonstrated suppressed microbial biomass, diversity and functioning in urban soils [13,14,15]. Such contradictory findings may result from differences in geographic scales, habitat conditions, and/or diverse environmental perturbations across study regions [9,16,17]. Although studies have demonstrated that urbanization significantly alters microbial biomass and community structure, our understanding of microbial physiological adaptations (e.g., membrane lipid remodeling) at the cellular level remains limited [18].

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) profiling is uniquely positioned to address this integral gap, offering a powerful tool for simultaneously characterizing microbial biomass (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungi), balances of community structure (e.g., ratios of Gram-positive bacteria/Gram-negative bacteria and fungi/bacteria), and physiological stress adaptations (e.g., shifts toward saturated fatty acids to maintain membrane fluidity under warming conditions; [18,19]). This multidimensional capacity makes PLFA analysis particularly suited to investigating the structural responses and physiological adaptations of soil microbial communities to urbanization, especially along well-defined urban–suburban–exurban gradients. Therefore, a systematic investigation of microbial biomass, community structure and membrane lipid composition is essential for advancing our mechanistic understanding of microbial responses and adaptations to urbanization and predicting soil quality in urban forests.

Here, we use PLFA analysis to investigate variations in microbial biomass, community structure and membrane lipid composition in forest soils along an urban–suburban–exurban gradient across different soil depths and between dry and wet seasons. We hypothesized the following: (1) Microbial community structure will shift significantly along the urbanization gradient, with exurban areas supporting a higher microbial biomass of major microbial groups (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and actinobacteria) than urban sites. This pattern is expected to be driven by reductions in soil nutrients and increases in abiotic stress, leading to lower total PLFA concentrations in urban soils. (2) Microbial membrane lipid composition will undergo adaptive remodeling in response to urbanization, with the relative abundance of saturated fatty acids increasing significantly in urban compared with exurban soils. Such shifts likely reflect an adjustment to urban environmental stresses (e.g., nutrient limitation, temperature fluctuations), as higher saturation enhances membrane rigidity and stability under adverse conditions. (3) These microbial characteristics (biomass, community structure, and membrane lipid composition) will correlate strongly with urbanization-modified soil properties, such as soil nutrient availability and physical structure, which directly regulate microbial community and adaptive strategies. The findings are expected to provide a deeper mechanistic understanding of urban soil ecosystem functioning and offer valuable insights for the conservation and sustainable management of urban forests in the face of continuing global urbanization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Soil Sampling

This study was conducted in Guangzhou (112°57′–114°03′ E, 22°26′–23°56′ N), Guangdong Province, South China, a core city of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and a representative region of rapid urbanization in China. The area experiences a typical subtropical climate with distinct dry and wet seasons. The wet season extends from April to September and the dry season from October to March. Over the past decade, the mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation were 23.1 °C and 2059.7 mm, respectively (Guangzhou Climate Bulletin). The monthly average temperature peaks at 29.7 °C in July and reaches a minimum of 14.3 °C in January. The zonal vegetation is a south subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest, and the predominant soil type is Latosolic Red soil derived from sandstone, shale, and granite [20].

Guangzhou covers an administrative area of 7434 km2. By 2024, the urbanization rate had reached 87.24%, with a permanent resident population of 18.978 million and a population density of 2553 persons km−2. Driven by sustained economic growth and urban expansion, the city has developed a pronounced ecological gradient from urban to rural areas. For example, forest coverage is lower in the central urban area and increases toward the peripheral zones [21]. This distinct urbanization gradient provides an ideal platform for studying the response mechanisms of forest ecosystems to anthropogenic pressures.

2.2. Soil Sampling

Based on land use type, impervious surface distribution, and the degree of human disturbance [22,23], Guangzhou was divided into an urban–suburban–exurban gradient (Figure S1). Along this gradient, Baiyun Mountain Scenic Area (BYS; urban), Maofeng Mountain Forest Park (MFS; suburban), and Shimen National Forest Park (SM; exurban) were selected as study sites (Table S1). At each site, four to five 20 m × 20 m quadrats were established, with a minimum separation of 100 m between quadrats to ensure spatial independence and minimize edge effects [24,25]. Soil samples were collected from each site in January and July 2024 at depths of 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm. Therefore, a total of 78 soil samples (4 to 5 quadrats × 3 depths × 3 sites × 2 seasons) were collected. The samples were immediately placed in iceboxes and transported to the laboratory. They were then sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove gravel and plant residues, homogenized, and stored for further soil property determination and PLFA analysis. Samples from each quadrat were processed and analyzed individually. Additionally, intact soil cores of 100 cm3 were collected from each quadrat at the three depths using a cutting ring for soil bulk density (BD) determination.

2.3. Analyses of Soil Properties

Soil organic carbon (SOC) and total nitrogen (TN) contents were determined with an elemental analyzer after air-drying and sieving through a 100-mesh sieve. Soil BD was calculated by oven-drying the intact soil cores at 105 °C to constant weight and then dividing the dry weight by the core volume (100 cm3). Soil pH was measured potentiometrically in a 1:2.5 soil–water suspension. Total phosphorus (TP) was quantified by NaOH fusion-molybdenum antimony anti-spectrophotometry, and available phosphorus (AP) was extracted with NaHCO3 and measured by molybdenum blue spectrophotometry. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and nitrogen (DON) were extracted with 0.5 mol·L−1 K2SO4 and analyzed using a TOC analyzer. Gravimetric soil water content (SWC) was determined by oven-drying soil samples at 105 °C for 48 h. The soil properties are summarized in Table S2.

2.4. PLFA Analysis

Soil microbial biomass, community structure and membrane lipid composition were assessed using PLFA profiles extracted from each individual soil sample following the method modified by Bossio and Scow [26]. Briefly, 8 g of freeze-dried soil was extracted using a chloroform–methanol–phosphate buffer mixture (1:2:0.8, v/v/v), and trans-esterified into fatty acid methyl esters using 1 mL 0.2 M methanolic KOH. After extraction, the individual fatty acid methyl esters were detected using an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a MIDI Sherlock Microbial Identification System (MIDI Inc., Newark, DE, USA) (detailed procedures are provided in Methods S1). The individual PLFA concentration was calculated based on the internal standard (19:0, methyl nonadecanoate, C20H40O2) and is expressed as nmol PLFA per gram of dry soil.

PLFAs were assigned to specific microbial groups according to the method described previously [18,27,28,29]. The corresponding biomarkers are listed in Table S3. Bacterial PLFAs were the sum of Gram-positive (GP), Gram-negative (GN), and actinobacterial PLFAs. Total microbial PLFAs were defined as the sum of bacterial and fungal PLFAs. The ratio of fungal to bacterial (F/B) and GP to GN (GP/GN) PLFAs was used to evaluate shifts in microbial community structure. To characterize microbial membrane lipid composition, PLFAs were further categorized into saturated fatty acids with branches (BRFAs), saturated fatty acids without branches (SAFAs) and unsaturated fatty acids (UNFAs). Both absolute (nmol/g) and relative (mol %) biomass were employed in the analysis. The absolute biomass was used to assess the actual biomass of specific microbial or lipid groups in the soils (e.g., total PLFAs, bacterial and SAFAs), while relative biomass was used to characterize the proportions of specific microbial or lipid groups in the total microbial PLFA pool.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm), and their interactions to microbial indices were tested by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the adonis2 function in the vegan package with “Manhattan” as the method. The assumption of homogeneity of group dispersions was tested by permutational analysis of multivariate dispersions (PERMDISP) using the betadisper function in the vegan package. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was applied to detect differences in soil properties and microbial indices (i.e., microbial biomass, community composition and membrane lipid composition) among soil depths within each site, as well as among sites for the same depth. Prior to the one-way ANOVA, the normality of data distribution and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Data that did not meet the assumptions were appropriately transformed. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to visualize patterns in microbial community structure. Pairwise permutational multivariate ANOVA (pairwise PERMANOVA) via the pairwiseAdonis package was further used to test the differences in microbial indices among sites and soil depths. Finally, a Mantel test was employed to explore the relationships between microbial indices and environmental factors. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.5.1).

3. Results

3.1. Soil Microbial Biomass and Community Structure

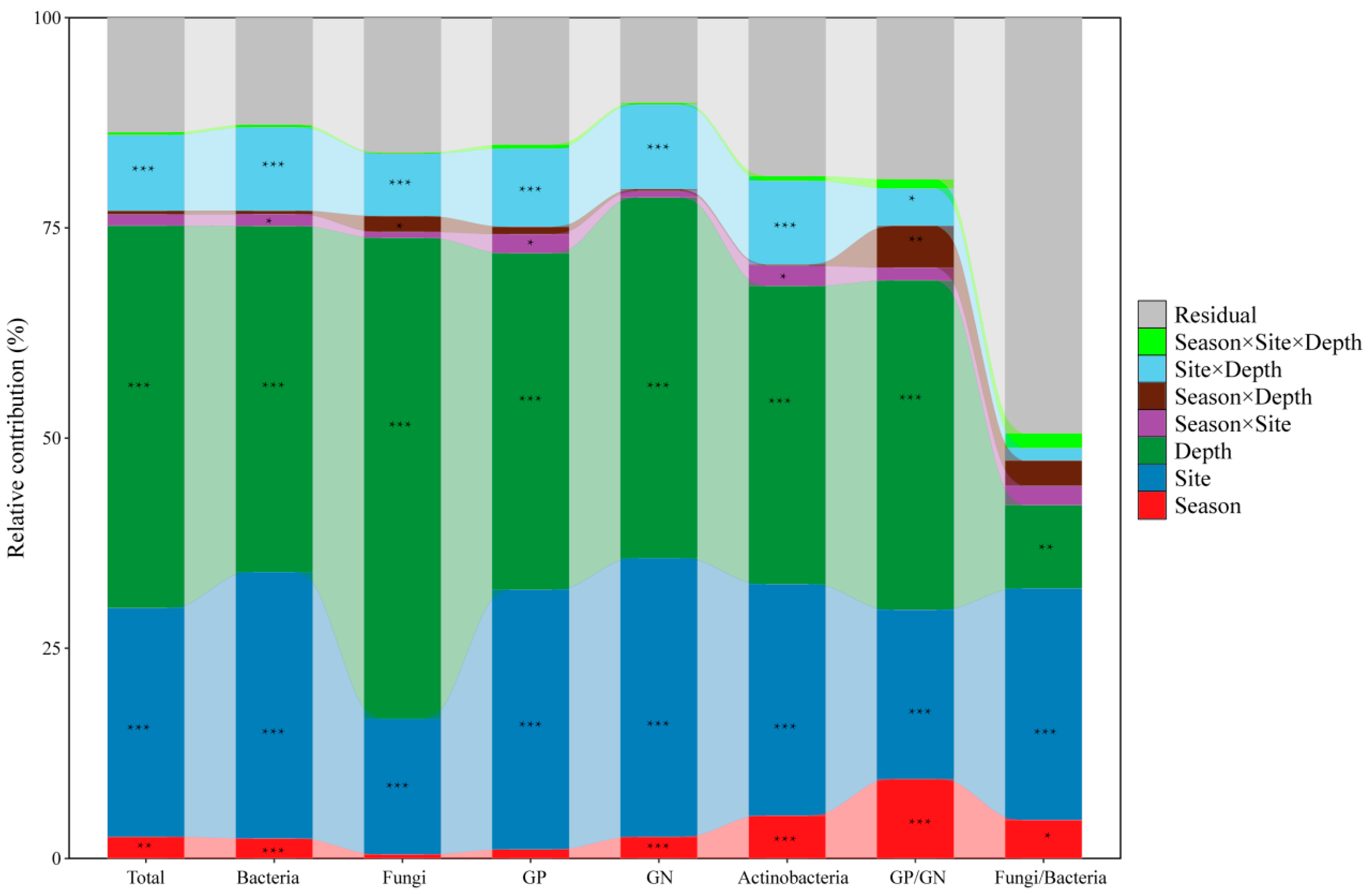

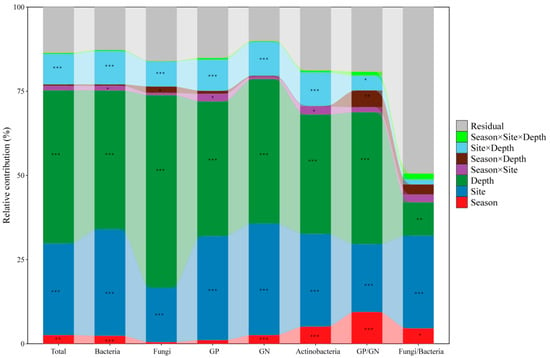

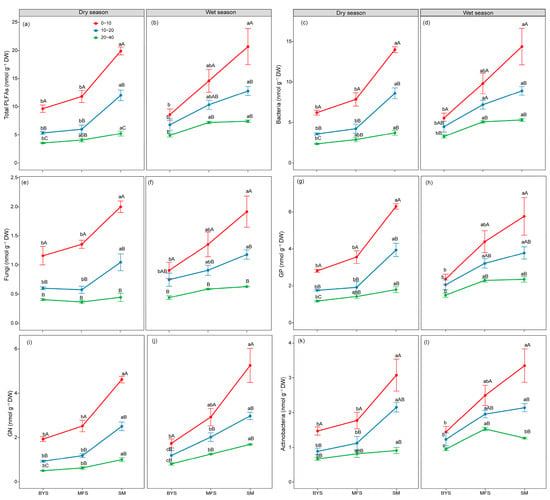

The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), and soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm) to the absolute and relative biomass of microbial groups and community structures were determined by PERMANOVA (Figure 1 and Figure S2). The results demonstrated that soil depth and site were the two most dominant factors explaining the variance across nearly all microbial indicators, with PERMDISP confirming that these factors also significantly influenced within-group dispersion (p < 0.001; Table S4). This indicated that within-group variability was not equal across all sites and depths, accounting for the significant PERMANOVA results. In contrast, season alone exhibited a relatively limited effect on most microbial groups, with small contributions < 5% and no significant effect on within-group dispersion (PERMDISP, p > 0.05). Notable exceptions were the ratios of GP/GN and F/B, for which the season alone had a significant influence, explaining 9.45% (F = 29.53, p < 0.001) and 4.58% (F = 5.56, p = 0.023) of the variance, respectively. Moreover, the three-way interaction season × site × depth also showed significant dispersion effects (PERMDISP, p ≤ 0.04; Table S4), suggesting that their variability was shaped by complex interactions among all factors, beyond seasonal shifts alone. Among the interaction terms, site × depth was consistently important in both PERMANOVA (explaining 7–10% variance, p < 0.001) and PERMDISP (p < 0.001), demonstrating that the effects of depth on microbial communities were site-specific in terms of both composition and dispersion.

Figure 1.

The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm), and their interactions on absolute biomass of microbial groups and community structure were indicated by PERMANOVA. Asterisk indicates significance level (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). GP: Gram-positive bacteria; GN: Gram-negative bacteria.

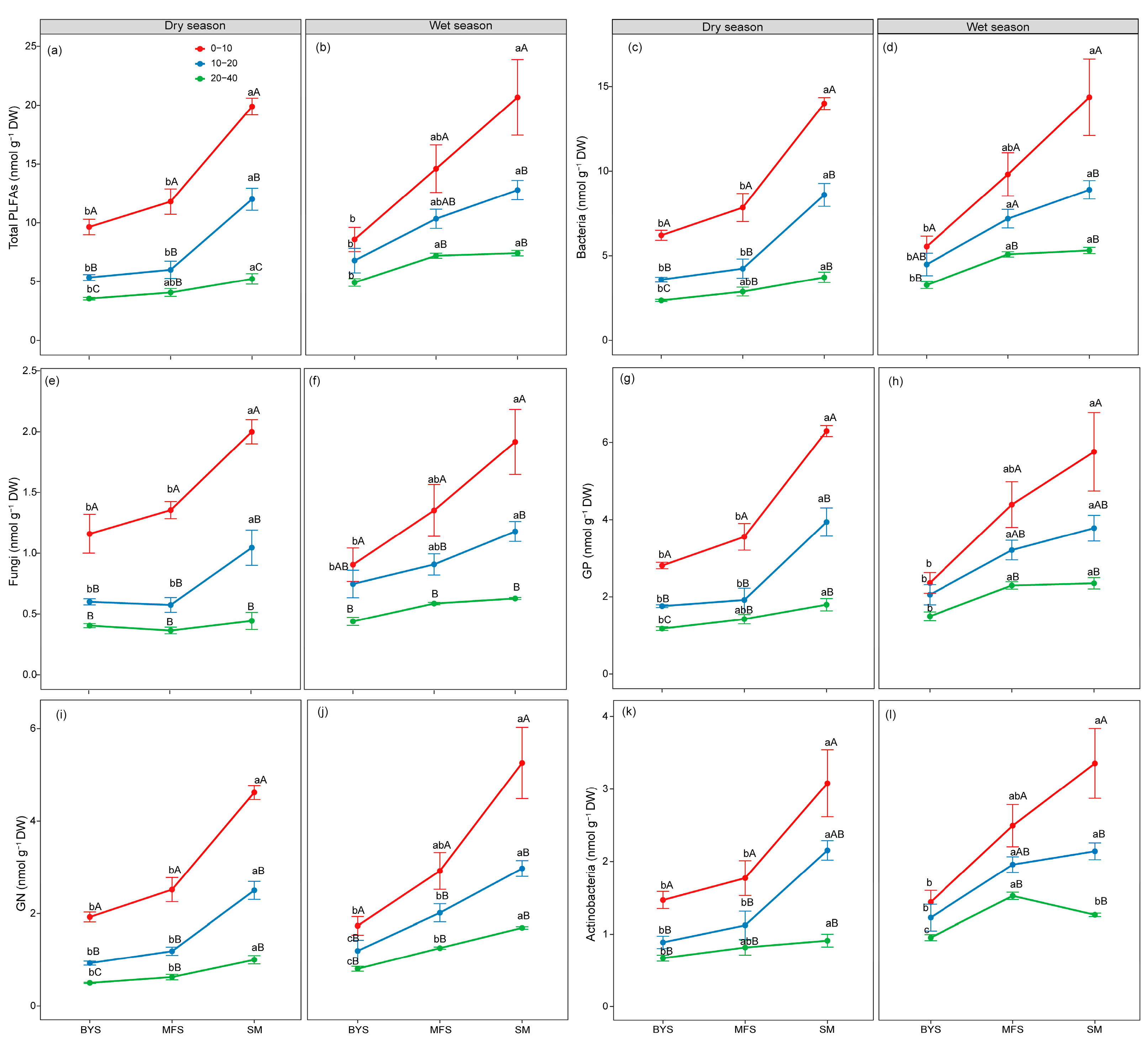

The one-way ANOVA results showed that soil microbial biomass and community composition exhibited significant spatio-temporal variations, with distinct patterns observed along soil depth and urban–suburban–exurban gradients (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Soil depth (0−10 cm, 10−20 cm, and 20−40 cm) induced a consistent vertical gradient in microbial biomass, with all microbial groups declining significantly with increasing depth (p < 0.05). Specifically, the 0−10 cm surface soil supported the highest microbial biomass across all groups, whereas the 20−40 cm deep soil exhibited the lowest biomass (Figure 2). This trend was consistent between wet and dry seasons, highlighting the strong regulatory role of soil depth in microbial distribution. Along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient, microbial biomass and community structure also varied significantly, with SM consistently supporting the highest microbial biomass, followed by MFS and BYS (p < 0.05; Figure 2). This pattern remained stable across seasons and soil depths, reflecting the influence of human disturbance intensity on microbial habitats.

Figure 2.

The variations in absolute biomass (nmol PLFA g−1 soil) of total microbial (a,b), bacterial (c,d), fungal (e,f), GP (g,h), GN (i,j), and Actinobacterial (k,l) PLFAs along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient and across different soil layers in the dry and wet seasons. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 4 or 5). Lowercase letters show significant differences between sampling sites in the same soil layer, and uppercase letters represent significant differences between soil layers at the same site (p < 0.05) as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test. GP: Gram-positive bacteria; GN: Gram-negative bacteria.

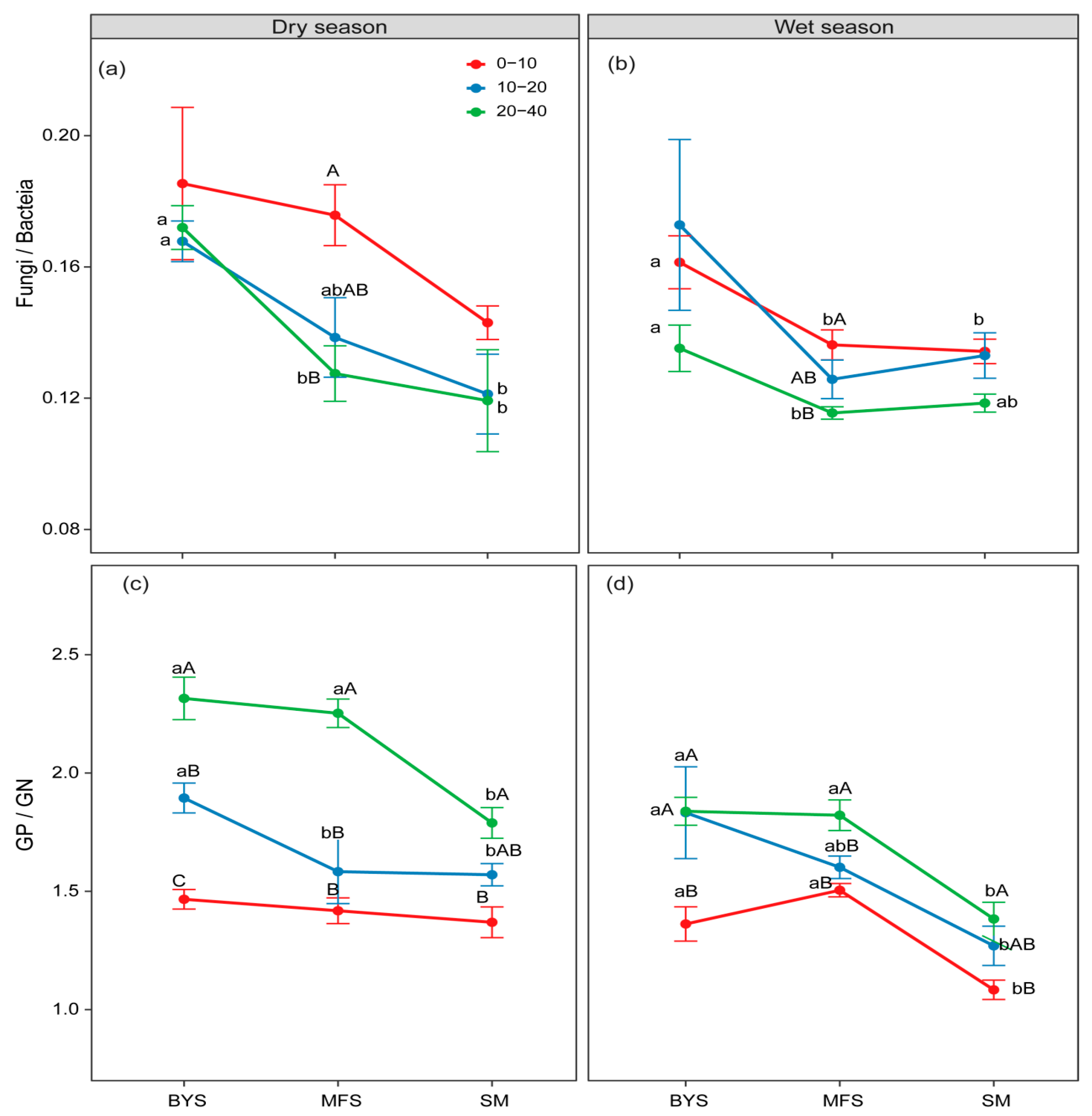

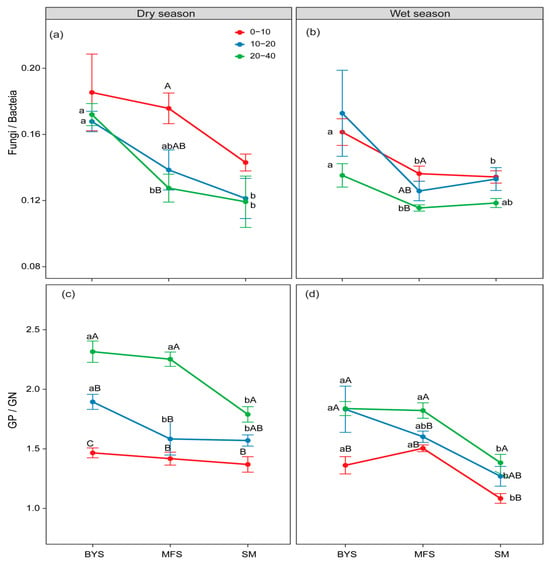

Figure 3.

The variations in fungi/bacteria (a,b) and GP/GN (c,d) along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient and across different soil layers in the dry and wet seasons. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 4 or 5). Lowercase letters show significant differences between sampling sites in the same soil layer, and uppercase letters represent significant differences between soil layers at the same site (p < 0.05) as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test. GP: Gram-positive bacteria; GN: Gram-negative bacteria.

The relative biomass of soil microbial groups varied systematically across sites and depths (Figure S3). The relative biomass of GN and fungi generally decreased with soil depth, whereas GP, actinobacteria and bacteria showed opposite trends. Additionally, a consistent urban–suburban–exurban gradient was observed for bacteria and GN, with their relative biomass being significantly highest at SM (exurban), followed by MFS (suburban), and lowest at BYS (urban). In contrast, the relative biomass of fungi was highest at BYS, followed by MFS, and lowest at SM. This differential response indicates a shift from resource-acquisitive communities towards stress-tolerant taxa.

However, the ratios of F/B ratio and GP/GN showed opposite trends to those of soil microbial biomass across soil depths and along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient, which reflects the adaptive adjustment of microbial communities to environmental constraints. Specifically, the F/B and GP/GN ratios were higher in 20−40 cm than in 0−10 cm surface soil at all sites (except for the F/B ratio during the wet season) and were higher at BYS than at SM across seasons and soil depths (Figure 3).

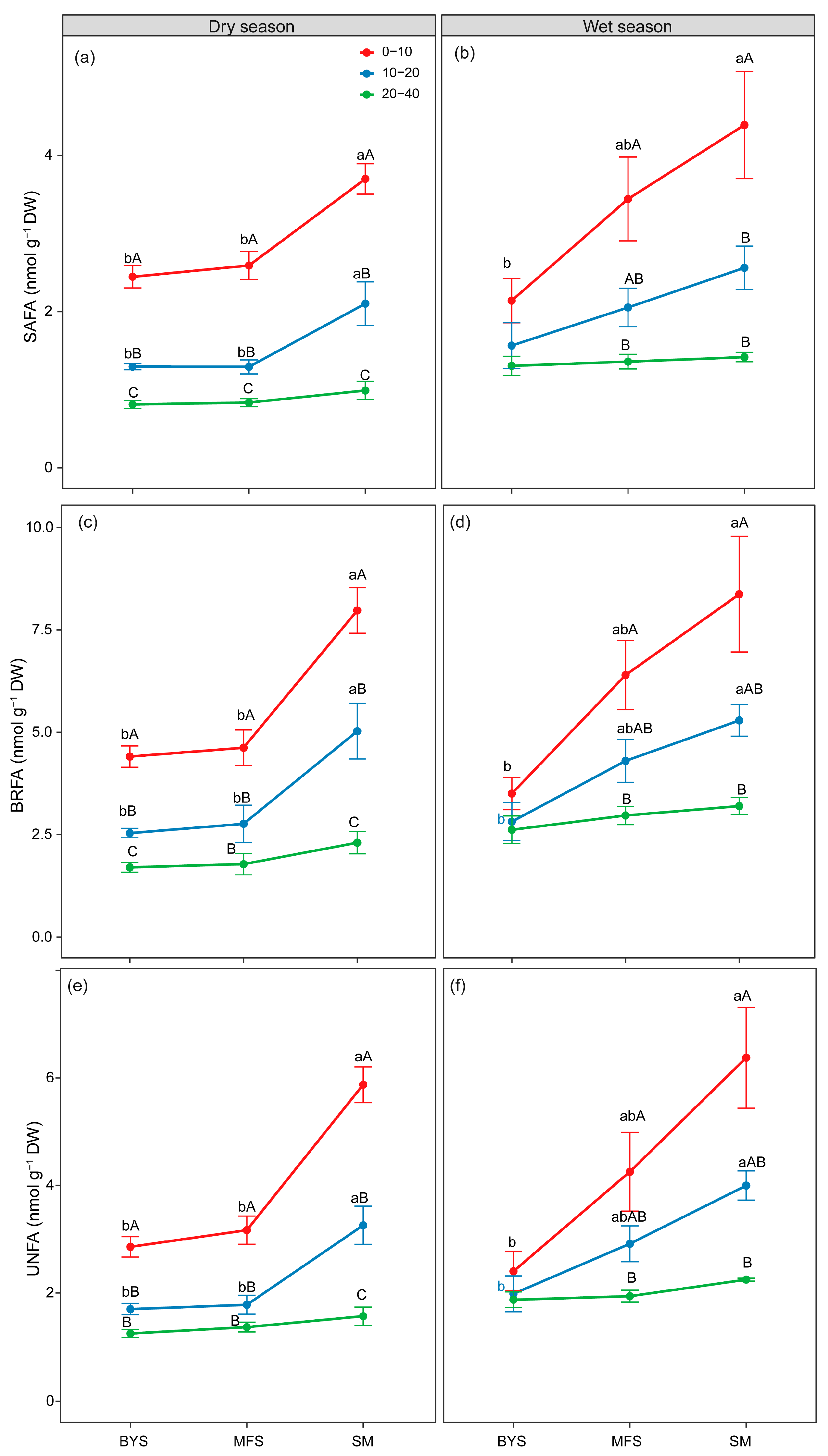

3.2. Soil Microbial Membrane Lipid Composition

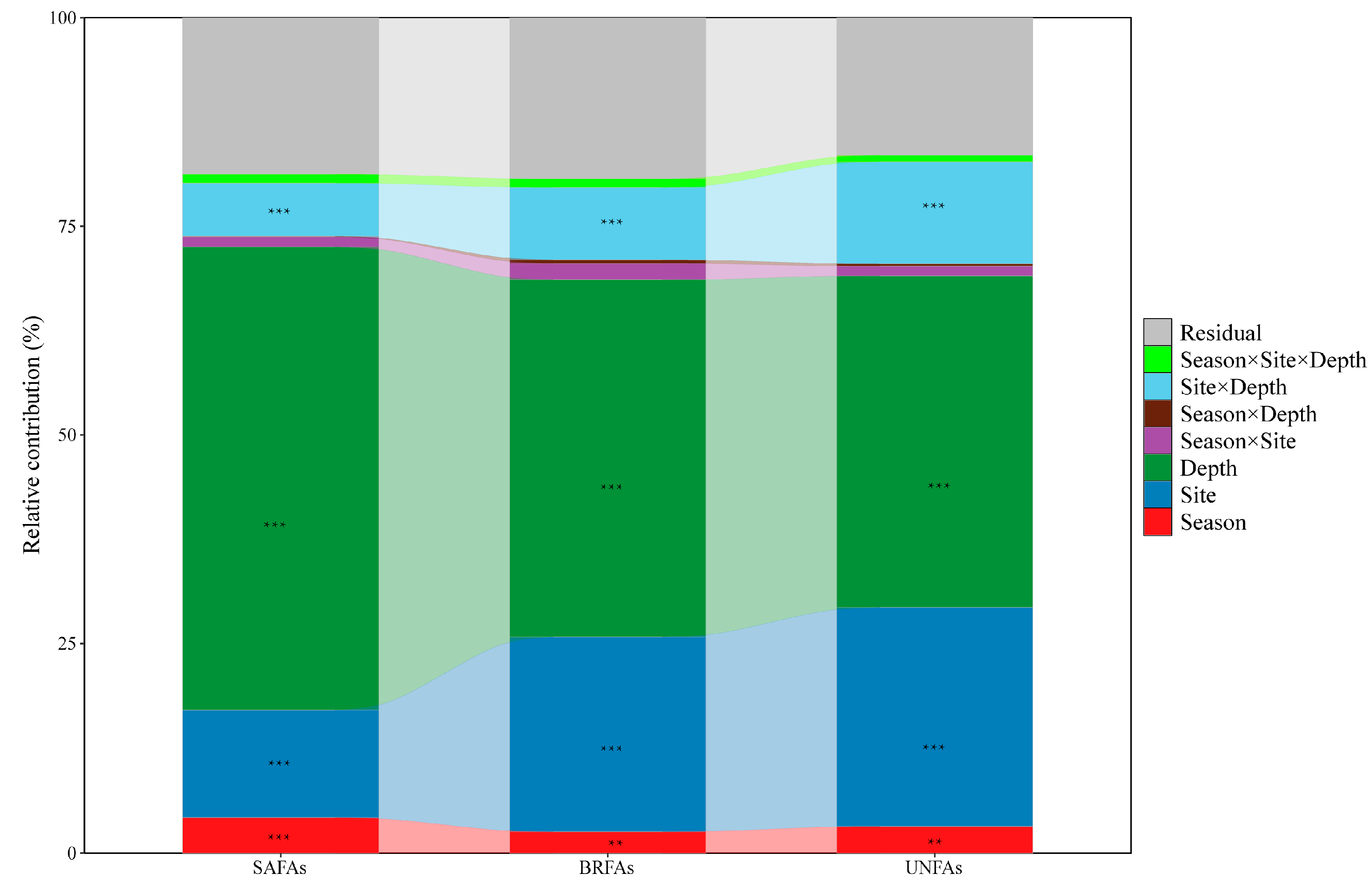

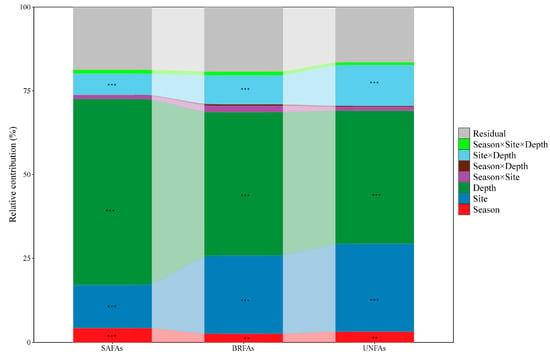

The PERMANOVA results highlighted that season, site, soil depth and the interaction of site × depth significantly affected the absolute biomass of soil microbial membrane lipid composition (Figure 4; p < 0.01). For all three lipid categories, depth explained the largest proportion of variance (39.8–55.5%, F = 66.49–88.76, p < 0.001). Site contributed 12.9–26.2% of variance, with stronger effects on UNFAs (F = 47.69, p < 0.001) and BRFAs (F = 36.19, p < 0.001) than on SAFAs (F = 20.57, p < 0.001). Season contributed minimally to the three lipid categories, with a more pronounced effect on SAFAs (R2 = 4.14%, F = 13.24, p < 0.001) than on UNFAs (R2 = 3.12%, F = 11.36, p = 0.002) and BRFAs (R2 = 2.48%, F = 7.71, p = 0.007). However, the combined effects of season, site, soil depth and their interactions can only explained 76.35%, 28.62%, 47.49% variance of the relative biomass of SAFAs, BRFAs, and UNFAs, respectively (Figure S4). Specifically, season (R2 = 2.91%, F = 7.37, p = 0.003), site (R2 = 32.06%, F = 40.67, p < 0.001), soil depth (R2 = 34.13%, F = 43.29, p < 0.001) alone significantly affected the relative biomass of SAFAs, whereas only the interaction of season × site significantly influenced on that of BRFAs (R2 = 9.18%, F = 3.86, p = 0.031). Site (R2 = 12.22%, F = 6.98, p < 0.001), For UNFAs, soil depth (R2 = 12.62%, F7.21, p = 0.002) and their interaction (R2 = 11.96%, F = 3.42, p = 0.014) were significant. Additionally, PERMDISP analysis (Table S4) revealed that within-group dispersion varied significantly across sites and depths for all three lipid categories (p < 0.001), indicating the heterogeneity in lipid composition is shaped not only by differences between groups (as shown by PERMANOVA) but also by within-group variability in dispersion.

Figure 4.

The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm), and their interactions on absolute biomass of soil microbial membrane lipid composition were indicated by PERMANOVA. Asterisk indicates significance level (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). BRFAs: saturated fatty acids with branches; SAFA: saturated fatty acids without branches; and UNFAs: unsaturated fatty acids.

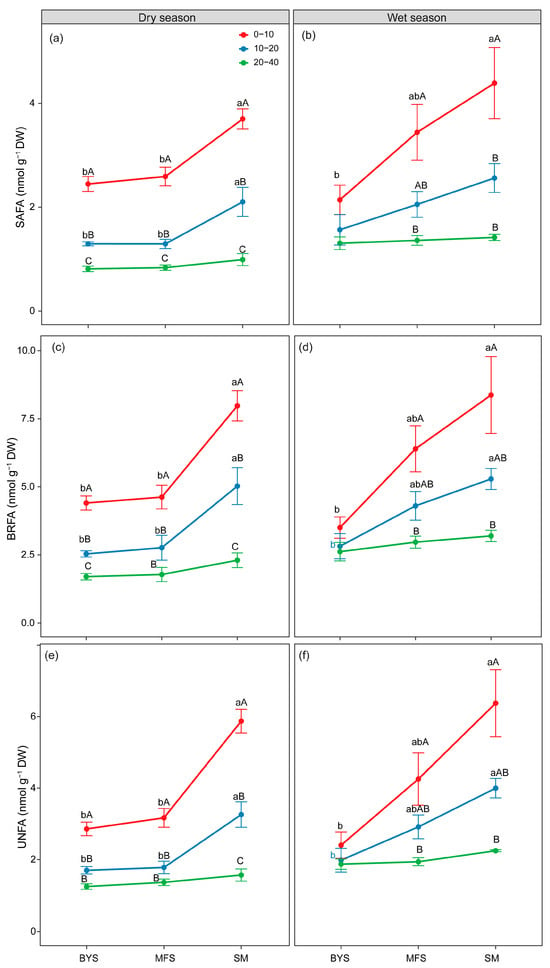

Furthermore, soil depth induced consistent vertical gradients in the absolute biomass of SAFAs, BRFAs, and UNFAs with significantly higher biomass in 0–10 cm surface soil than in 20–40 cm deep soil (Figure 5a–f). A stronger depth effect was observed at SM. Additionally, the absolute biomass of SAFAs, BRFAs, and UNFAs displayed a clear increasing pattern along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient, showing a biomass order of SM > MFS > BYS. A stronger site effect was observed in 0–10 cm surface soil, while no significant variations were found among the sites in 20–40 cm surface soil.

Figure 5.

The variations in absolute biomass (nmol PLFA g−1; soil) of SAFAs (a,b), BRFAs (c,d) and UNFAs (e,f) along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient and across different soil layers in the dry and wet seasons. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 4 or 5). Lowercase letters show significant differences between sampling sites in the same soil layer, and uppercase letters represent significant differences between soil layers at the same site (p < 0.05) as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test. BRFAs: saturated fatty acids with branches; SAFAs: saturated fatty acids without branches; and UNFAs: unsaturated fatty acids.

Moreover, the relative biomass of SAFAs showed an obvious vertical decline with increasing soil depth. In the 0–10 cm surface layer, the relative biomass of SAFAs reached 0.35–0.45 mol % across all sites, but it decreased significantly as depth increased. For instance, it dropped to 0.30–0.40 mol % in the 10–20 cm layer and further declined to 0.25–0.35 mol % in the 20–40 cm deep layer (Figure S5a–f). In sharp contrast, the relative biomass of UNFAs displayed the opposite vertical trend. Namely, it increased with soil depth, especially at the BYS site. In the 0–10 cm surface layer, the relative biomass of UNFAs was relatively low (0.30–0.38 mol %), but it increased to 0.35–0.45 mol % in the 20–40 cm layer. The relative biomass of SAFAs displayed a clear decreasing pattern along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient. For example, the relative biomass of SAFAs at BYS was significantly higher than at SM (p < 0.05), with the most significant differences observed in the 0–10 cm and 10–20 cm soil layers. In contrast to SAFAs, the relative biomass of UNFAs exhibited an increasing trend along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient, particularly in the 0–10 cm soil layer (Figure S6e,f). The relative biomass of UNFAs at SM was significantly higher than at BYS in the 0–10 cm layer (p < 0.05). However, the relative biomass of BRFAs was conserved, demonstrating no significant differences across either soil depth or the urban–suburban–exurban gradient (Figure S5c,d).

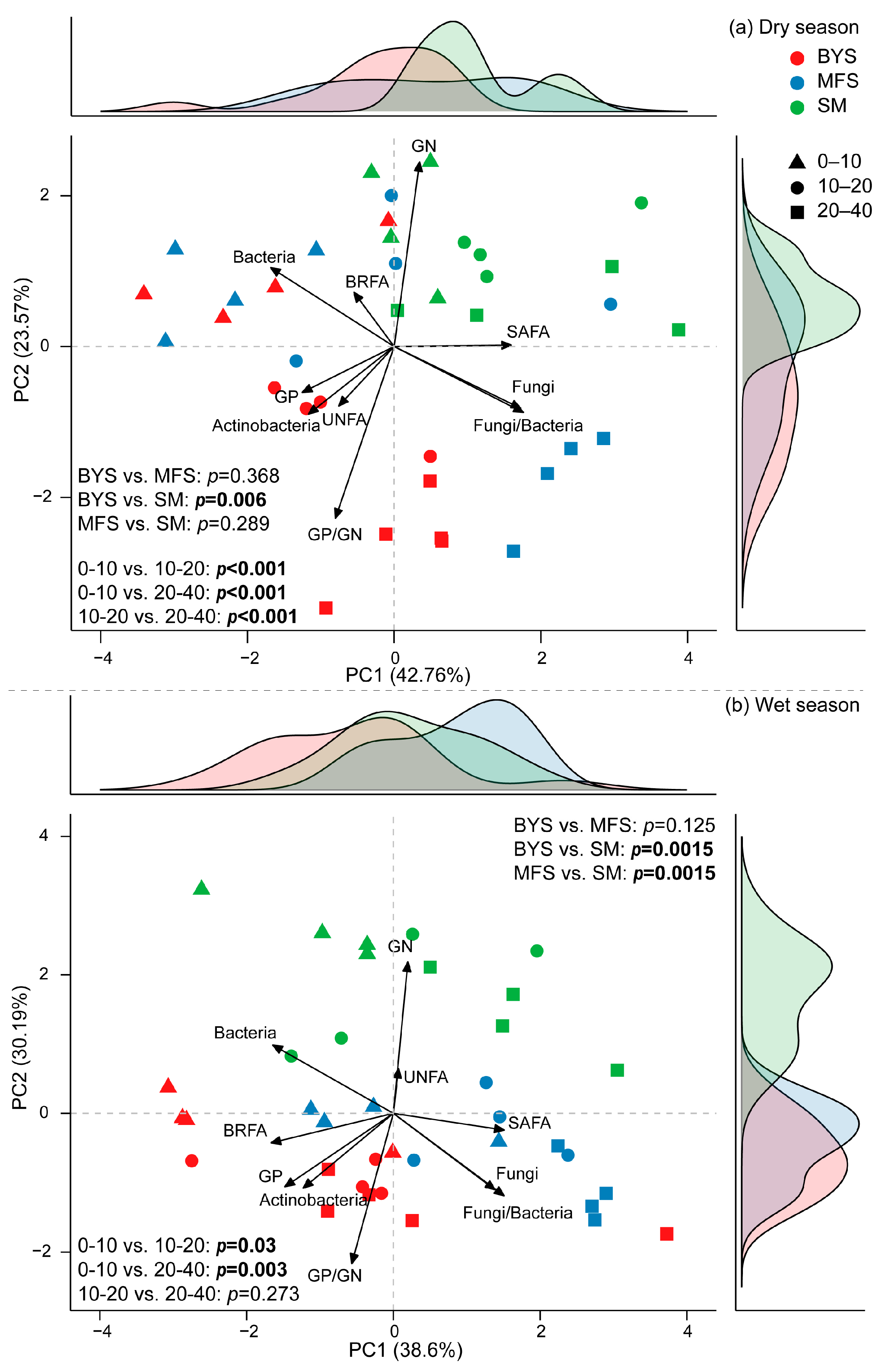

3.3. Soil Microbial Community Characteristics and Influencing Factors

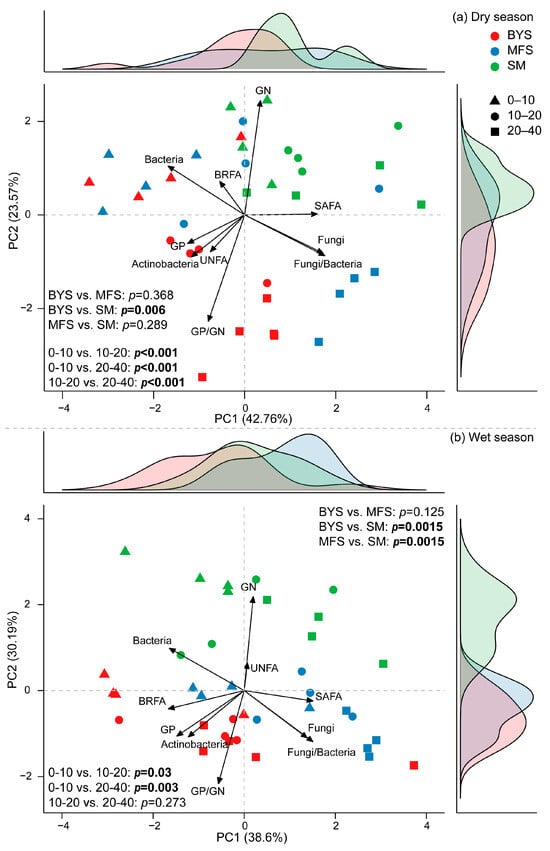

The principal component analysis (PCA) of the relative biomass of different microbial groups (normalized, accounting for 66.33% and 68.7% of the variations in dry and wet season, respectively; Figure 6) was roughly separated by site and soil depth. The relative biomass of GN, GP/GN, F/B, fungi, and bacteria contributed more to such variation patterns. Specifically, PC1 and PC2 explained 42.76% and 23.57% of the total variance in the dry season, respectively (Figure 6a). Samples from different soil depths were clearly separated along the principal components, indicating that soil depth had a significant influence on microbial communities (p < 0.001). In contrast, differences between sites were limited; for example, BYS and SM differed significantly (p = 0.006), while no significant differences were found between BYS and MFS (p = 0.368) or between MFS and SM (p = 0.289). During the wet season (Figure 6b), PC1 and PC2 accounted for 38.6% and 30.19% of the variance, respectively. The separation of samples by soil depth remained evident, such as significant separation between 0 and 10 cm and 10–20 cm (p = 0.03) and between 0 and 10 cm and 20–40 cm (p = 0.003), but there was non-significant separation between 10 and 20 cm and 20–40 cm (p = 0.273). During the wet season, site differences became more pronounced. This was evidenced by highly significant differences between BYS and SM (p = 0.0015) and between MFS and SM (p = 0.0015).

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis of soil microbial community with marginal density plots in the dry (a) and wet seasons (b). Colors in the density plots correspond to sites, with red representing BYS, blue representing MFS, and green representing SM.

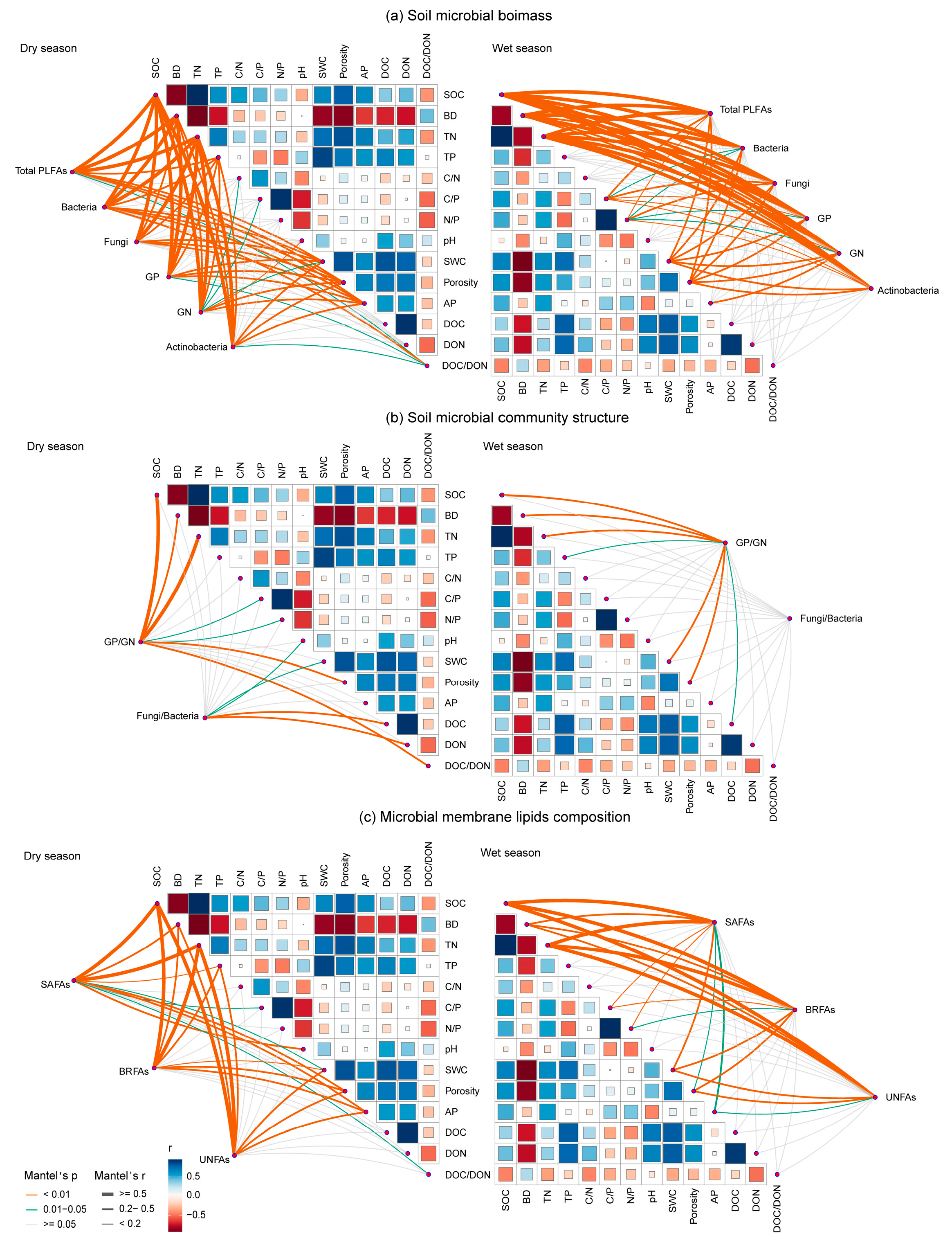

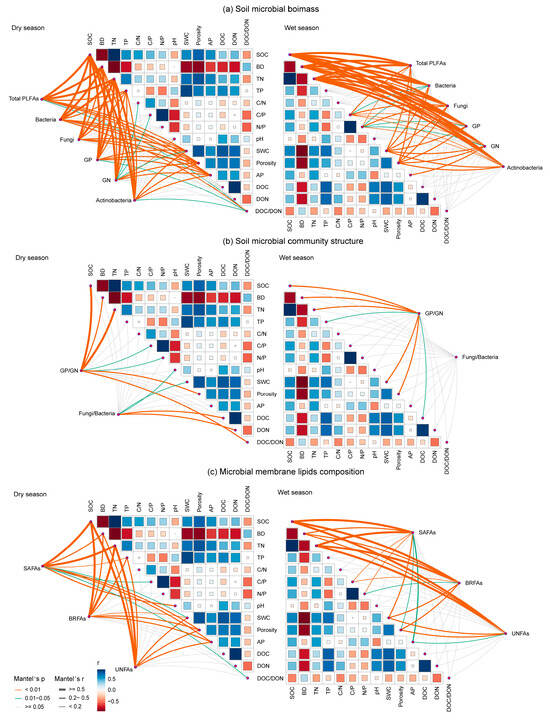

Mantel’s tests were employed to assess the relationships between various microbial indices and environmental factors across dry and wet seasons. The results confirmed that soil microbial indices were collectively regulated by multiple soil properties, with distinct yet overlapping key drivers for each group (Figure 7). Specifically, SOC, BD, and TN emerged as the most influential factors driving the soil microbial biomass (Mantel’s r > 0.5, p < 0.001). The microbial community structure, represented by the GP/GN ratio, was significantly correlated with SWC, TN, BD, and SOC, while the F/B ratio was primarily linked to DOC and DON. The categories of membrane lipid composition showed strong significant correlations with SOC and TN (Mantel’s r > 0.5, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, the relative biomass of fungi was significantly correlated with SOC, BD, and TN (Mantel’s r > 0.48 in dry season and Mantel’s r > 0.4 in wet season, respectively; p < 0.001), while the biomass of bacteria was significantly weakly correlated with soil pH, AP, and TN (p < 0.05; Figure S6a). The relative biomass of SAFAs was mainly associated with C/P, soil pH and DOC in the dry season, while the relative biomass of SAFAs, BRFAs and UNFAs was significantly related to soil pH, AP and DOC (p < 0.05; Figure S6b).

Figure 7.

Pairwise comparisons between soil properties and microbial biomass (a), community structure (b), and membrane lipid composition (c) in the dry and wet seasons. The color gradients denote Spearman’s correlation coefficients; line edge width corresponds to Mantel’s r statistic for the corresponding distance correlations, and edge color denotes the statistical significance based on 9999 permutations. SWC, soil water content; BD, soil bulk density; SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; C/N, soil organic carbon to total nitrogen ratio; C/P, soil organic carbon to total phosphorus ratio; N/P, total nitrogen to total phosphorus ratio; AP, available phosphorus; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; DON, dissolved organic nitrogen; DOC/DON, dissolved organic carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. GP: Gram-positive bacteria; GN: Gram-negative bacteria; BRFAs: saturated fatty acids with branches; SAFAs: saturated fatty acids without branches; and UNFAs: unsaturated fatty acids.

4. Discussion

4.1. Microbial Community Shifts Along the Urban–Suburban–Exurban Gradient

Our results demonstrate that soil microbial biomass and community structure exhibit significant variations along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient (BYS-MFS-SM) and across different soil depths. The observed decline in total microbial biomass, as well as the biomass of specific groups (e.g., bacteria and fungi), from the exurban (SM) to the urban (BYS) site (Figure 2) aligns with our first hypothesis and corroborates the findings from other urban ecosystems where human disturbance has suppressed soil biota [13,14]. This suppression is likely mediated by a suite of urban-associated stressors, including increased soil compaction (higher BD), potential pollutant accumulation, reduced litter production and fine root biomass, and altered microclimates (e.g., the urban heat island effect) [30,31,32]. In contrast, the exurban forests, characterized by lower human disturbance, higher litter inputs, and better-preserved habitat conditions, provide more favorable environments for microbial growth [33,34], as evidenced by the higher soil nutrients (Table S2).

While our study confirms the well-established ecological rule of decreasing microbial biomass with increasing soil depth across various ecosystems [35,36], a key finding lies in the modulation of this vertical pattern by urbanization. The significant site × depth interaction reveals that the rate of this decline is not uniform. Surface soil (0–10 cm) is a hotspot for microbial activity and conducive to microbial growth, as it has higher organic matter, moisture, and oxygen contents than in deeper soil [37,38]. However, deep layers are progressively resource-limited, with low C input and nutrient availability [39,40]. The significant site × depth interaction further reveals that the impact of depth on microbial biomass is site-specific. For instance, the depth-related decline in biomass was more pronounced in the exurban forest (SM) than in the urban site (BYS). This may be attributed to the steeper gradient in resource availability (e.g., SOC, TN) between surface and deep layers in exurban soils, whereas urban soils exhibit a more homogenized nutrient profile across depths (Table S2). Simultaneously, deep soils are characterized by stable but resource-limited niches. Microorganisms in these layers often exhibit specialized metabolic pathways to adapt to low-oxygen and low-nutrient environments [41,42]. This functional specialization results in a high degree of homogeneity within a specific depth, but sharp divergence between depths, thereby amplifying the depth effect relative to the site effect. Furthermore, the deep soil layers act as a physical barrier, restricting the downward migration of surface microbes and leading to decoupling between surface and deep communities [43]. This finding shifts the focus from documenting the vertical gradient to understanding how urbanization alters its intensity, highlighting a nuanced interaction between natural stratification and anthropogenic disturbance.

Despite a distinct subtropical dry–wet season climate, seasonal variation played a relatively minor role compared with the dominant effects of soil depth and urbanization (Figure 1, Figure 4, Figures S2 and S4). This muted seasonal contribution may be attributed to the prior adaptation of soil microbial communities to chronic urban stressors. The inherent physiological plasticity and rapid generation times of soil microorganisms likely facilitated this rapid adaptation, leading to a community that exhibits less responsiveness to seasonal climatic fluctuations [44]. Furthermore, the variability among sites outweighs the seasonal shifts within each site, leading to the seasonal variability of microbial biomass being masked by spatial variability [45,46].

Community structure indices (the F/B and GP/GN ratios) displayed trends opposite to those of microbial biomass along both the urban–suburban–exurban and soil depth gradients, indicating a community-level strategic shift towards microbial stress tolerance [47,48]. Fungi have extensive hyphal networks, large genomes, and diverse metabolic pathways, making them more tolerant to nutrient scarcity and soil compaction than bacteria [49]. In contrast, soil bacteria, with their higher resource acquisition efficiency and lower metabolic demands, tend to prioritize investment in rapid growth and reproduction over resource acquisition under resource-rich conditions [48]. Similarly, GP bacteria, possessing thicker and more rigid cell walls, are generally more resistant to physical disturbance and nutrient limitation compared with GN bacteria [50,51,52]. This community-level restructuring highlights a key microbial strategy under urbanization pressure, shifting from high-biomass, and fast-growing communities to slower-growing, stress-resistant ones.

4.2. Adaptive Changes in Microbial Membrane Lipid Composition

Our results provide clear evidence of adaptive changes in microbial membrane lipid composition in response to urbanization and soil depth, supporting our second hypothesis. The increased relative biomass of saturated fatty acids (SAFAs) in urban soils and surface layers, coupled with the increase in unsaturated fatty acids (UNFAs) in exurban and deeper soils (Figure S5), provides compelling evidence for physiological adaptation at the cellular level. Microbes can regulate membrane fluidity by altering the saturation of their phospholipid fatty acids under stress—a homeoviscous adaptation mechanism [53,54]. The urban environment, characterized by the heat island effect and potentially greater fluctuations in temperature and moisture, likely imposes thermal and osmotic stress on soil microbes [55,56]. In response, urban communities increase the proportion of SAFAs for the purpose of lowering membrane fluidity and stabilizing cell structure that can maintain its functional integrity under stressful conditions [57,58]. Conversely, the resource-rich conditions of exurban soils allow microbes to maintain a higher proportion of UNFAs, which create a more fluid membrane that facilitates nutrient transport and metabolic activity [18,19,59]. The fact that these trends were most pronounced in the surface soil, where it experiences the greatest environmental fluctuations, further strengthens the interpretation. Additionally, the lack of significant variation in branched fatty acids (BRFAs) across gradients suggests that this particular membrane adaptation strategy would be masked by other factors (e.g., nutrient availability). This finding underscores the specificity of different lipid-based adaptation pathways.

4.3. Linking Microbial Responses to Key Edaphic Drivers

The Mantel’s results robustly confirmed our third hypothesis, revealing that the variations in microbial communities were intricately linked to a set of key soil properties. SOC, TN, and BD emerged as the main regulators, exerting strong and pervasive influences on microbial biomass, community structure (GP/GN ratio), and membrane lipid composition (Figure 7). These factors effectively encapsulate the core alterations induced by urbanization, such as the degradation of soil physical structure (increased BD) and the alteration of nutrient cycling and availability (SOC, TN) [9,13]. The strong correlation between SOC, TN, and membrane lipid composition effectively couples the availability of key soil resources with strategic microbial investment in cellular membrane structures [60].

Distinct, group-specific drivers also highlight the niche differentiation and adaptation strategies among microbial taxa [61]. The fungal-to-bacterial (F/B) ratio was uniquely and primarily correlated with dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen (DOC, DON), pointing to the particular sensitivity of community balance to the labile fraction of soil organic matter. This aligns with the known ecological strategy of fungi, whose extensive hyphal networks confer a superior ability to forage for patchy, soluble resources compared with bacteria [62,63]. In contrast, the GP/GN ratio was associated with a broader suite of factors, including SWC, TN, BD, and SOC. This reflects the multifaceted niche partitioning between bacterial groups, involving differential responses to physical disturbance, nutrient limitation, and osmotic stress, which linked to their distinct cell wall architectures and life-history strategies [64,65]. This highlights that the microbial response to urbanization is not static but is modulated by urbanization-induced soil and climatic variations, a crucial consideration for predicting long-term ecosystem dynamics under global change.

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

While our study provides valuable insights into microbial responses to urbanization, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the PLFA method, while robust for assessing broad-scale community structure and physiological status, has inherent limitations. It offers taxonomic resolution only to broad groups (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria) and cannot distinguish taxa at the species level, potentially masking fine-scale compositional changes. Secondly, although we measured key soil properties, other unmeasured urban stressors, such as specific pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, microplastics) or specific management histories, could be important co-drivers of the observed microbial patterns. Finally, our sample size (n = 4 or 5 per group) provided sufficient statistical power to detect the predominant effects of urbanization and soil depth, but may have limitations when detecting the full extent of small-scale spatial heterogeneity in urban soil ecosystems.

Future research should build upon these findings by employing complementary techniques. Metagenomics would provide finer taxonomic resolution and directly reveal functional genetic adaptations across the urbanization gradient. High-resolution lipidomics could delineate the full spectrum of membrane lipid remodeling with greater specificity in response to stress. Most importantly, manipulative experiments (e.g., warming, nutrient addition and precipitation change) are needed to link specific environmental stressors to the observed microbial structural and physiological responses, and consequently to their driven ecosystem functions. Finally, a long-term study across multiple years would clarify the stability and trajectory of microbial adaptations under ongoing urbanization.

5. Conclusions

This study provides integrated evidence that urbanization significantly alters not only the structure and biomass of soil microbial communities but also their physiological adaptations at the cellular level. The results showed that microbial biomass consistently decreased from exurban to urban sites and from surface to deep soils. Meanwhile, community structure shifted toward higher F/B and GP/GN ratios in urban soils and deep layers. The microbial membrane lipid composition showed adaptive changes, with higher saturation in urban and surface soils, likely as a response to environmental stress. These microbial patterns were strongly driven by key soil properties, including SOC, TN, BD, and SWC, highlighting the role of nutrient and physical conditions in mediating urbanization effects. These findings enhance our mechanistic understanding of how soil microbes respond and adapt to urbanization, offering insights for developing strategies to mitigate urbanization impacts on soil health and guiding sustainable urban forest development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15020242/s1, Methods S1 [7,66,67,68]: Detailed procedures of PLFAs. Table S1: Overview of the studied forests. Table S2: Physicochemical properties of different soil layers along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient. Table S3: Phospholipid fatty acid signatures selected to characterize microbial community structure in this study. Table S4: Sample dispersion with groups was tested by permutational analysis of multivariate dispersions (PERMDISP). Figure S1: The location of study sites BYS-MFS-SM in Guangzhou. Figure S2: The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm), and their interactions on relative biomass of microbial groups and community structure indicated by PERMANOVA. Figure S3: The variations in relative biomass of microbial groups along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient and across different soil layers in the dry and wet seasons. Figure S4. The contributions of season (dry and wet seasons), site (BYS, MFS, and SM), soil depth (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm), and their interactions on relative biomass of soil microbial membrane lipid composition indicated by PERMANOVA. Figure S5: The variations in the relative biomass of microbial membrane lipid composition along the urban–suburban–exurban gradient and across different soil layers in the dry and wet seasons. Figure S6: Pairwise comparisons between soil properties and the relative biomass of microbial groups (a), and membrane lipid composition (b) in the dry and wet seasons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and Z.L.; methodology, J.H. and J.T.; software, J.H.; validation, J.H., Y.Q., Y.P. and Z.L.; formal analysis, J.H. and Y.C.; investigation, J.H., J.T., Y.Q., Y.C. and G.C.; resources, J.H., Y.P. and Z.L.; data curation, Y.C. and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H., J.T. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.C., Y.P. and Z.L.; visualization, J.H., J.T. and Y.Q.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Y.P. and Z.L.; funding acquisition, J.H., Y.P. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Development Project of Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (202206010058), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515110821), the budget project of Guangzhou forestry and landscape Bureau department (202307130200), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3802602).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the administration of Baiyun Mountain Scenic Area, Maofeng Mountain Forest Park, and Shimen National Forest Park for granting us permission to conduct soil sampling. We are also grateful to our colleagues for their invaluable assistance in field sampling and laboratory analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mitchell, M.G.E.; Devisscher, T. Strong Relationships between Urbanization, Landscape Structure, and Ecosystem Service Multifunctionality in Urban Forest Fragments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, M.F.U.; Doh, Y.H.; Lee, B.G. Impact of Urbanization on Land Surface Temperature and Surface Urban Heat Island Using Optical Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of Jeju Island, Republic of Korea. Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.-M. The Main Drivers of Biodiversity Loss: A Brief Overview. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 7, 000346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.I.; Thomson, B.C.; James, P.; Bell, T.; Bailey, M.; Whiteley, A.S. The Bacterial Biogeography of British Soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tan, X.; Nie, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Mo, J.; Leloup, J.; Nunan, N.; Ye, Q.; et al. Distinct Responses of Abundant and Rare Soil Bacteria to Nitrogen Addition in Tropical Forest Soils. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03003-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, K.; Chu, H.; Eldridge, D.J.; Gaitan, J.J.; Liu, Y.-R.; Sokoya, B.; Wang, J.-T.; Hu, H.-W.; He, J.-Z.; Sun, W.; et al. Soil Biodiversity Supports the Delivery of Multiple Ecosystem Functions in Urban Greenspaces. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Nie, Y.; Tan, X.; Hu, A.; Li, Z.; Dai, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, G.; Shen, W. Latitudinal Patterns and Drivers of Plant Lignin and Microbial Necromass Accumulation in Forest Soils: Disentangling Microbial and Abiotic Controls. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 194, 109438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xie, S.; Zang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Multiple Anthropogenic Environmental Stressors Structure Soil Bacterial Diversity and Community Network. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 198, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Robinson, J.M.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Potapov, A.; Yao, H.; Zhu, B.; Tiunov, A.V.; Zhang, L.; Chan, F.K.S.; Chang, S.X.; et al. Unforeseen High Continental-Scale Soil Microbiome Homogenization in Urban Greenspaces. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp Schmidt, D.J.; Pouyat, R.; Szlavecz, K.; Setälä, H.; Kotze, D.J.; Yesilonis, I.; Cilliers, S.; Hornung, E.; Dombos, M.; Yarwood, S.A. Urbanization Erodes Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Diversity and May Cause Microbial Communities to Converge. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Barberán, A.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Wurzburger, N.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Impact of Urbanization on Soil Microbial Diversity and Composition in the Megacity of Shanghai. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enloe, H.A.; Lockaby, B.G.; Zipperer, W.C.; Somers, G.L. Urbanization Effects on Soil Nitrogen Transformations and Microbial Biomass in the Subtropics. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Wei, H. Coupled Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Fractions and Microbial Community Composition in Urban and Suburban Forests. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, T.; Fu, Y.; Chen, B.; Crotty, F.; Murray, P.J.; Yu, S.; Xu, C.; Liu, W. Spatial Change in Glomalin-Related Soil Protein and Its Relationships with Soil Enzyme Activities and Microbial Community Structures during Urbanization in Nanchang, China. Geoderma 2023, 434, 116476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Gao, J.; Tang, M.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, D.; Yang, X.; Chen, B. Urbanization Reduces the Stability of Soil Microbial Community by Reshaping the Diversity and Network Complexity. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Su, L.; Hui, N.; Jumpponen, A.; Kotze, D.J.; Lu, C.; Pouyat, R.; Szlavecz, K.; Wardle, D.A.; Yesilonis, I.; et al. Urbanisation Shapes Microbial Community Composition and Functional Attributes More so than Vegetation Type in Urban Greenspaces across Climatic Zones. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. The Composition and Assembly of Soil Microbial Communities Differ across Vegetation Cover Types of Urban Green Spaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tan, X.; Nie, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhou, W.; Shen, W. Enhancement of Saturated Fatty Acid Content in Soil Microbial Membranes across Natural and Experimental Warming Gradients. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2023, 176, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; He, J.; Zheng, G.; Tan, X.; Cui, S. Climate-Driven Microbial Communities Regulate Soil Organic Carbon Stocks Along the Elevational Gradient on Alpine Grassland over the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qiu, J.; Chen, X.; Luo, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, G. Soil Mesofauna Community Changes in Response to the Environmental Gradients of Urbanization in Guangzhou City. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 8, 546433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Urban Expansion Dynamics and Modes in Metropolitan Guangzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Xia, J.; Chen, X.; Fan, L.; Liu, S.; Qin, Y.; Qin, Z.; Xiao, X.; Xu, W.; Yue, C.; et al. Reconstructing Long-Term Forest Cover in China by Fusing National Forest Inventory and 20 Land Use and Land Cover Data Sets. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2023, 128, e2022JG007101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Annual Maps of Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Xu, F. Moderate Thinning Enhances Soil Carbon-Nitrogen Cycling and Microbial Diversity in Degraded Mixed Forests. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1652531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, S.; Xu, J. Soil C:N:P Stoichiometry in Two Contrasting Urban Forests in the Guangzhou Metropolis: Differences and Related Dominates. Forests 2025, 16, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, D.A.; Scow, K.M. Impacts of Carbon and Flooding on Soil Microbial Communities: Phospholipid Fatty Acid Profiles and Substrate Utilization Patterns. Microb. Ecol. 1998, 35, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joergensen, R.G. Phospholipid Fatty Acids in Soil—Drawbacks and Future Prospects. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Q.; Zhong, B.; Chen, W.; Mo, J.; Wang, F.; Lu, X. Consistent Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Soil Microbial Communities across Three Successional Stages in Tropical Forest Ecosystems. CATENA 2023, 227, 107116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xiao, M.; Wu, J.; Tong, Y.; Ji, J.; Huang, Q.; Ding, F.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Effects of Microplastics on Photosynthesized C Allocation in a Rice-Soil System and Its Utilization by Soil Microbial Groups. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y. Surface Urban Heat Island Disparities and the Role of Urban Form across the Urban-Rural Gradient. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, M.; Dou, X.; Liu, X. Urbanization Weakens Soil Carbon Stocks but Enhances Carbon Stability through Coupled Physicochemical and Microbial Mechanisms in Beijing Urban-Rural Forests. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asabere, S.B.; Zeppenfeld, T.; Nketia, K.A.; Sauer, D. Urbanization Leads to Increases in pH, Carbonate, and Soil Organic Matter Stocks of Arable Soils of Kumasi, Ghana (West Africa). Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Wei, H. Urbanization Induced Changes in the Accumulation Mode of Organic Carbon in the Surface Soil of Subtropical Forests. CATENA 2022, 214, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, L.; Zhao, F.; Tang, J.; Bu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, L. Effects of Urban–Rural Environmental Gradient on Soil Microbial Community in Rapidly Urbanizing Area. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2023, 9, 0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Ding, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhu, B. Changes in Soil Total, Microbial and Enzymatic C-N-P Contents and Stoichiometry with Depth and Latitude in Forest Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Jing, X.; Feng, W. Divergent Vertical Distributions of Microbial Biomass with Soil Depth among Groups and Land Uses. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Biswas, A.; Adamchuk, V.I. Implementation of a Sigmoid Depth Function to Describe Change of Soil pH with Depth. Geoderma 2017, 289, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, D.; McClure, R.; Jansson, J. Trends in Microbial Community Composition and Function by Soil Depth. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wei, W.; Mustafa, A.; Chen, W.; Mao, Q.; Mo, J.; Li, S.; Lu, X. Divergent Microbial Metabolic Limitations Across Soil Depths After Two Decades of High Nitrogen Inputs in a Primary Tropical Forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawska-Wlodarczyk, K.; Kushwaha, P.; Stokes, O.; Rasmussen, C.; Neilson, J.W.; Maier, R.M.; Babst-Kostecka, A. Depth-Dependent Heterogeneity in Topsoil Stockpiles Influences Plant-Microbe Interactions and Revegetation Success in Arid Mine Reclamation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1003, 180673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Quensen, J.; Williams, T.A.; Thompson, M.; Streeter, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, S.; Wei, G.; et al. Diversification, Niche Adaptation, and Evolution of a Candidate Phylum Thriving in the Deep Critical Zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2424463122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.; Varliero, G.; Qi, W.; Stierli, B.; Walthert, L.; Brunner, I. Shotgun Metagenomics of Deep Forest Soil Layers Show Evidence of Altered Microbial Genetic Potential for Biogeochemical Cycling. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 828977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, S.; Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Brangarí, A.C.; et al. Deciphering Microbiomes Dozens of Meters under Our Feet and Their Edaphoclimatic and Spatial Drivers. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecon, R.; Or, D. Biophysical Processes Supporting the Diversity of Microbial Life in Soil. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; He, L.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Janssens, I.A.; Wang, J.; Pang, G.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X. Latitudinal Shifts of Soil Microbial Biomass Seasonality. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tedersoo, L.; Hu, A.; Han, C.; He, D.; Wei, H.; Jiao, M.; Anslan, S.; Nie, Y.; Jia, Y.; et al. Greater Diversity of Soil Fungal Communities and Distinguishable Seasonal Variation in Temperate Deciduous Forests Compared with Subtropical Evergreen Forests of Eastern China. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Raza, M.M.; Abbas, T.; Guan, X.; Zhou, W.; He, P. Responses of Soil Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities under Nitrogen Addition in Fluvo-Aquic and Black Soil of North China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1249471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Nie, M. Opposite Effects of N on Warming-Induced Changes in Bacterial and Fungal Diversity. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, T.; Luo, Y.; Shi, M.; Tian, X.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial Interactions for Nutrient Acquisition in Soil: Miners, Scavengers, and Carriers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Kätterer, T.; Thornton, B.; Börjesson, G. Dynamics of Fungal and Bacterial Groups and Their Carbon Sources during the Growing Season of Maize in a Long-Term Experiment. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yan, X.; Wang, D.; Siddique, I.A.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Yang, L.; Miao, Y.; Han, S. Soil Microbial Community Based on PLFA Profiles in an Age Sequence of Pomegranate Plantation in the Middle Yellow River Floodplain. Diversity 2021, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.G.; Nicolitch, O.; Griffiths, R.I.; Goodall, T.; Jones, B.; Weser, C.; Langridge, H.; Davison, J.; Dellavalle, A.; Eisenhauer, N.; et al. Soil Microbiomes Show Consistent and Predictable Responses to Extreme Events. Nature 2024, 636, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinensky, M. Homeoviscous Adaptation—A Homeostatic Process That Regulates the Viscosity of Membrane Lipids in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, R.; Ejsing, C.S.; Antonny, B. Homeoviscous Adaptation and the Regulation of Membrane Lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 4776–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepeeva, A.N.; Glushakova, A.M.; Kachalkin, A.V. Yeast Communities of the Moscow City Soils. Microbiology 2018, 87, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, M.; Joulian, C.; Motelica-Heino, M.; Norini, M.-P.; Hellal, J. Resistance and Resilience of Soil Nitrogen Cycling to Drought and Heat Stress in Rehabilitated Urban Soils. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 727468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.A. Thermal Adaptation of Decomposer Communities in Warming Soils. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, T.W.; Bradford, M.A. Thermal Acclimation in Widespread Heterotrophic Soil Microbes. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Xu, M.; Chi, Y.; Yu, S.; Wan, S.; He, N. Microbial Membranes Related to the Thermal Acclimation of Soil Heterotrophic Respiration in a Temperate Steppe in Northern China. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Yao, L. Soil Microbial Community and Physicochemical Properties Together Drive Soil Organic Carbon in Cunninghamia Lanceolata Plantations of Different Stand Ages. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metze, D.; Schnecker, J.; de Carlan, C.L.N.; Bhattarai, B.; Verbruggen, E.; Ostonen, I.; Janssens, I.A.; Sigurdsson, B.D.; Hausmann, B.; Kaiser, C.; et al. Soil Warming Increases the Number of Growing Bacterial Taxa but Not Their Growth Rates. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Frey, S.D. Revisiting the Hypothesis That Fungal-to-Bacterial Dominance Characterizes Turnover of Soil Organic Matter and Nutrients. Ecol. Monogr. 2015, 85, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E. Fungal Biomass Production and Turnover in Soil Estimated Using the Acetate-in-Ergosterol Technique. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2173–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; Li, Q. Negative Interactions between Bacteria and Fungi Modulate Life History Strategies of Soil Bacterial Communities in Temperate Shrublands under Precipitation Gradients. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 3459–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Wang, B.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Chang, S.X. Deciphering Factors Driving Soil Microbial Life-History Strategies in Restored Grasslands. iMeta 2023, 2, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhang, T.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Ye, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, J.; Mao, Q.; Mo, J.; et al. Temporal Patterns of Soil Carbon Emission in Tropical Forests under Long-Term Nitrogen Deposition. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, T.; Zhu, X.; Wu, D.; Petticord, D.F.; Hui, D.; et al. Roots Dominate Over Extraradical Hyphae in Driving Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation During Tropical Forest Succession. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yuan, Y.; Mou, Z.; Li, Y.; Kuang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Lambers, H.; et al. Faster Accumulation and Greater Contribution of Glomalin to the Soil Organic Carbon Pool than Amino Sugars Do under Tropical Coastal Forest Restoration. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.