Abstract

By addressing the challenges of management difficulties, insufficient integration of driver analysis, and single-dimensional analysis in the governance of illegal land use and illegal construction (collectively referred to as the “Two Illegalities”) under rapid urbanization, this study designs and implements a GIS-based governance system using Xiamen City as the study area. First, we propose a standardized data-processing workflow and construct a comprehensive management platform integrating multi-source data fusion, spatiotemporal visualization, intelligent analysis, and customized report generation, effectively lowering the barrier for non-professional users. Second, utilizing methods integrated into the platform, such as Moran’s I and centroid trajectory analysis, we deeply analyze the spatiotemporal evolution and driving mechanisms of “Two Illegalities” activities in Xiamen from 2018 to 2023. The results indicate that the distribution of “Two Illegalities” exhibits significant spatial clustering, with hotspots concentrated in urban–rural transition zones. The spatial morphology evolved from multi-core diffusion to the contraction of agglomeration belts. This evolution is essentially the result of the dynamic adaptation between regional economic development gradients, urbanization processes, and policy-enforcement synergy mechanisms. Through a modular, open technical architecture and a “Data-Technology-Enforcement” collaborative mechanism, the system significantly improves information management efficiency and the scientific basis of decision-making. It provides a replicable and scalable technical framework and practical paradigm for similar cities to transform “Two Illegalities” governance from passive disposal to active prevention and control.

1. Introduction

China’s rapid urbanization has intensified the contradiction between land supply and demand, making illegal land use and illegal construction (hereinafter referred to as the “Two Illegalities”, denoting suspected cases in this study) a persistent challenge constraining high-quality urban development and refined governance [1,2,3]. These activities not only undermine the authority of territorial spatial planning and encroach upon public resources but also pose significant threats to social stability, the ecological integrity, and public safety [4,5,6,7]. The scale of this issue is substantial: official data indicate that in 2023 alone, approximately 209,000 cases were detected nationwide, covering an area of 88,000 hectares. It is estimated that millions of land parcels may be implicated in “Two Illegalities”, presenting immense challenges for government agencies in managing land information [8,9,10].

Traditional management methods primarily rely on manual recordkeeping and static charts, often leading to fragmented data, limited knowledge discovery, and weak decision support [11,12]. The development of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) [13] and remote sensing technologies [14] has provided new pathways for managing and analyzing massive, multi-source spatial data [15,16]. These tools enable the integrated management, intelligent analysis, and intuitive visualization of spatial information, which are critical for effective “Two Illegalities” governance.

Current research on the “Two Illegalities” leveraging remote sensing and GIS focuses on two core directions. The first centers on the construction of multi-functional integrated platforms driven by remote sensing data. Specific efforts include: building cross-departmental collaborative management platforms to enhance overall regulatory execution [17]; integrating planning, detection, and governance functions to construct a unified technical support system [18]; implementing dynamic monitoring based on grid management architectures to support data-driven, refined governance [19]; introducing high-resolution imagery to improve the precision of monitoring and risk early-warning [20]; and digitizing the entire monitoring and verification process to strengthen the reliability and efficiency of business processing [21].

The second research direction involves multi-source data fusion analysis of the driving factors behind the “Two Illegalities”. For instance, studies have explored assessment methods and evolutionary laws of legacy illegal urban planning issues from the perspective of urban transition [22]; employed multi-criteria analysis to clarify the intrinsic link between urban spatial configuration and building violations, confirming economic factors as core variables [23]; applied isomorphism theory to attribute the prevalence of illegal land use to local institutional pressures and market uncertainty in specific industries, systematically explaining the impact mechanisms of these pressures on incidence rates and severity [24]; and utilized structural equation modeling combined with Pearson correlation tests and confirmatory factor analysis to quantify core drivers and their interactions [25].

However, existing research and application systems still face two key limitations. First, there is insufficient integration between platform-based management and driver analysis. Most platforms emphasize control functions but fail to embed analytical insights into management workflows to optimize strategy formulation. And analyses often remain detached from actual management scenarios, limiting the practical applicability of research findings. Second, driver analyses lack dimensionality and depth. Existing studies mostly focus on one or a few isolated factors, with inadequate analysis of multi-factor interactions and spatiotemporal dynamics, making it difficult to fully reveal the formation and evolution mechanisms of “Two Illegalities”. These limitations ultimately constrain the transformation from a “reactive response” to a “proactive prevention and control” governance paradigm of the “Two Illegalities”.

To address these challenges, this study selects Xiamen, a typical city in Southern China, as the study area to design and implement a GIS-based “Two Illegalities” governance system grounded in spatial analysis. The specific contributions are as follows:

- (1)

- A standardized processing workflow is proposed for the “Two Illegalities” scenario, achieving efficient integration and application of multi-source, heterogeneous, and massive data, and providing a unified data foundation for both platform control and in-depth driver analysis;

- (2)

- A management platform is constructed, which integrates spatiotemporal visualization, multi-temporal comparison, comprehensive querying, and customized report generation, lowering the technical barrier for non-specialists and enhancing the intuitiveness and scientific rigor of governance decision-making;

- (3)

- The core drivers, multi-factor interaction effects, and spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the “Two Illegalities” phenomenon are explored, providing a scientific basis for identifying key prevention areas, optimizing enforcement resource allocation, and formulating source control policies.

This system has been applied to “Two Illegalities” management practice and driver analysis in Xiamen. Beyond satisfying practical needs, it is designed as a replicable and scalable technical framework, providing practical reference and technical support for “Two Illegalities” governance in similar regions.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

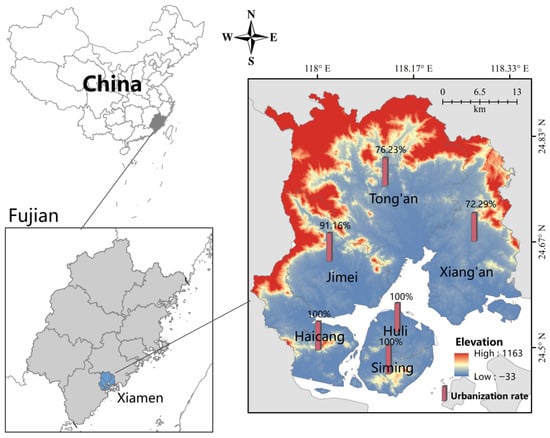

This study selects Xiamen City, Fujian Province, as the empirical case. In 2023, Xiamen had a total land area of 1699.01 km2, with a built-up area of only 397.84 km2, a permanent population of 5.35 million, and a built-up area population density as high as 13,448 persons/km2. Furthermore, the difference in urbanization rates between regions reaches nearly 30%. As a rapidly developing coastal city and tourist destination, Xiamen faces significant spatial resource constraints. Sustained economic growth and population inflows generate strong construction demand, while stringent ecological protection policies and urban landscape controls limit developable land [26]. This intense contradiction has led to the large-scale emergence of “Two Illegalities”. Data show that an average of nearly 5000 suspected “Two Illegalities” cases were detected each year from 2018 to 2023, with the annual disposed area exceeding 5 million m2 in both 2022 and 2023. Therefore, Xiamen was selected to verify the technical applicability and governance efficacy of the constructed GIS platform in a complex urban environment characterized by distinct urbanization gradients, a prominent urban–rural dual structure, and unbalanced development, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of Xiamen City of Fujian, China, and its six districts.

2.2. Data Sources

This study integrates multi-source data, including remote sensing imagery, vector data, and field survey records, to ensure the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the analysis results, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data sources and descriptions.

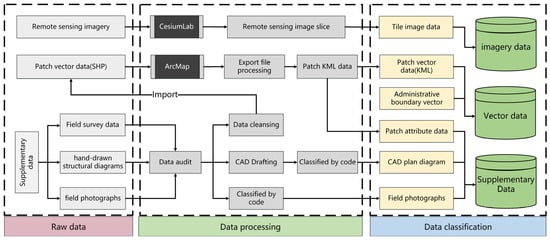

2.3. Data Processing

To establish a comprehensive, multi-temporal, and integrated information management system for the “Two Illegalities” activities, all data were processed and standardized to meet system loading requirements. First, field-collected baseline land parcel information was preprocessed and integrated with existing parcel boundaries in Shapefile (SHP) format. The merged data were imported into ArcMap (v10.8), reprojected to the China Geodetic Coordinate System 2000 (CGCS2000) coordinate system, and exported as Keyhole Markup Zipped (KMZ) files. These KMZ files were subsequently converted to Keyhole Markup Language (KML) format to enable efficient retrieval by the front-end application. Parcel identification numbers were mapped to unique system Identification (ID), guaranteeing a unique identifier for each land parcel.

After standardizing land parcel attributes, field survey photographs and Computer Aided Design (CAD) deliverables were systematically categorized, organized, and ingested into the database according to their land parcel IDs. This process created an interlinked multi-source dataset, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Data processing workflow.

For remote sensing imagery, the CesiumLab (v4) tiling technique was applied in accordance with OGC Web Map Tile Service (WMTS) specifications. The resulting tiles were uniformly published and configured for cross-domain access within an Nginx (v1.21.6) environment, enabling efficient tile storage and dynamic front-end retrieval. This workflow ensured systematic and logically coherent data organization, providing robust technical support for subsequent spatial analysis and visualization.

Upon completion of data processing, all datasets were classified and integrated into the “Two Illegalities” management system and categorized into three main types: remote sensing imagery, business data, and vector data. Business data encompass parcel-level attribute information, plane diagram, and field photographs. Vector data comprise land parcel boundaries and administrative division geometries.

3. The Proposed System

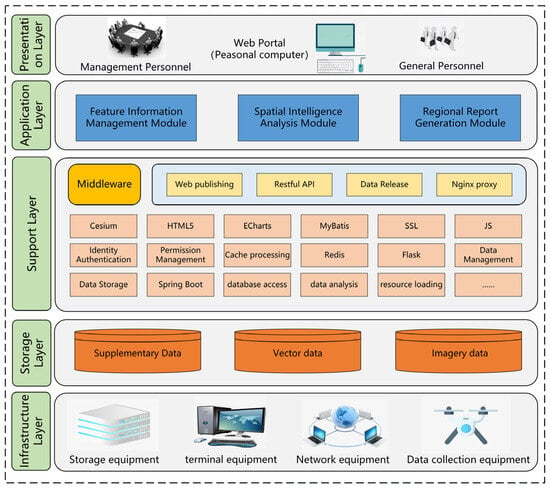

3.1. Overall System Architecture Design

Advances in natural resource monitoring technologies have led to the accumulation of data associated with “Two Illegalities” land parcels. This growth presents new challenges for information management systems: how to design management functions that accommodate data heterogeneity (e.g., enabling differentiated visualization of remote sensing imagery and parcel-level vector data), and how to ensure that analytical results are sufficiently interpretable to support effective governmental decision-making.

To address these challenges, this study proposed a multi-layer visual analytics system framework. The framework integrates technologies for data management, analytical processing, and database operation, providing comprehensive functionalities for querying and retrieval, spatial visualization, and spatial analysis of land parcel data. The system adopts a five-tier architecture (Figure 3), comprising the presentation layer, application layer, support layer, data layer, and infrastructure services layer.

Figure 3.

Visual analytics system architecture.

Presentation Layer: Serves as the primary user-system interface, enabling users to submit data queries and analytical requests, and visualize processed results.

Application Layer: Hosts the system’s core functional modules. By interacting with the support layer, it orchestrates business processes, ensuring reliable and efficient service delivery.

Support Layer: Acts as the technical core of the system, offering key services such as spatial analysis, data management, and visualization. It processes requests from the application layer and interacts with the data layer to enable flexible, secure, and high-performance system functions.

Data Storage Layer: Manages storage, retrieval, and access control for all system data, including vector data, attribute data, remote sensing imagery, and other geospatial resources.

Infrastructure Layer: Provides the physical and computational foundation of the system, delivering stable and scalable support to upper-layer applications and services.

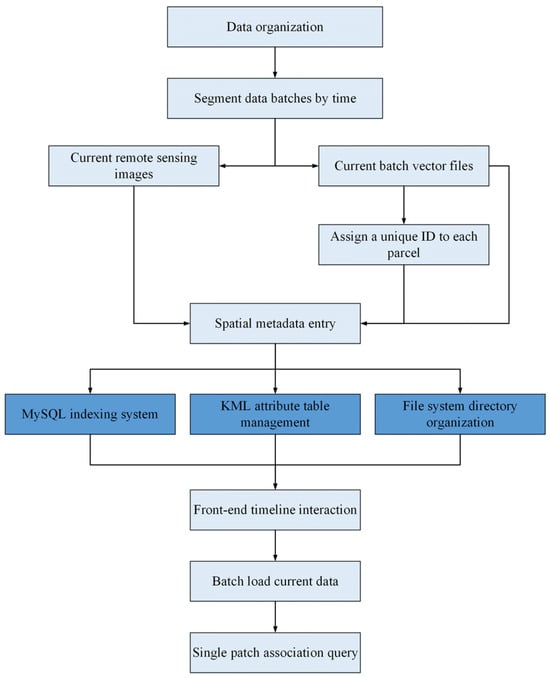

3.2. Land Parcel Information Management Mechanism

The land parcel information management module is designed to support the investigation and archival of “Two Illegalities” parcels. It contains an integrated framework for querying, multi-temporal comparison, and electronic case file generation.

Specifically, the query function, supported by back-end RESTful APIs, enables rapid retrieval and automated spatial positioning based on multiple criteria, including address, parcel status, and area. The temporal comparison feature integrates multi-temporal datasets through standardized timestamps, supporting dynamic data switching and intuitive visualization of spatiotemporal changes. The archive generation function consolidates land parcel attributes with field-collected photos to create standardized, archivable electronic case files.

To support these capabilities, the system employs a dual-indexing mechanism based on “Patch ID + Discovery Time” (Figure 4). Discovery Time serves as the primary index, enabling timeline-driven navigation across multi-temporal datasets while ensuring synchronized display of land parcels and their corresponding remote sensing imagery for each period. By objectively capturing temporal information and land use conditions, the remote sensing imagery functions as critical electronic evidence. This supports not only the identification of “Two Illegalities” parcels but also provides a reliable basis for evaluating the effectiveness of subsequent remediation measures.

Figure 4.

Workflow of land parcel information association.

Patch ID acts as the secondary index, facilitating associative queries following batch loading of multi-temporal data. Each land parcel is assigned a unique ID that serves as a unified primary key across KML attribute tables, MySQL database tables, and the file system directory structure. This indexing system significantly enhances data integrity and traceability in land parcel management while establishing a robust technical foundation for the deep integration of multi-source information.

3.3. Spatial Statistical Analysis Methods

The intelligent analysis module employs spatial algorithms and visualization techniques to analyze the distribution patterns of “Two Illegalities”, enabling a transition from experience-based to data-driven governance. This module integrates three core analytical functions. The information visualization function, implemented using ECharts (v5), generates graphical representations of land parcel attributes, such as violation type and building type. The hotspot detection function applies Moran’s I statistics to identify villages with statistically significant spatial clustering of illegal parcels. The centroid trajectory analysis calculates annual centroid coordinates to visualize the spatiotemporal dynamics of “Two Illegalities” distribution.

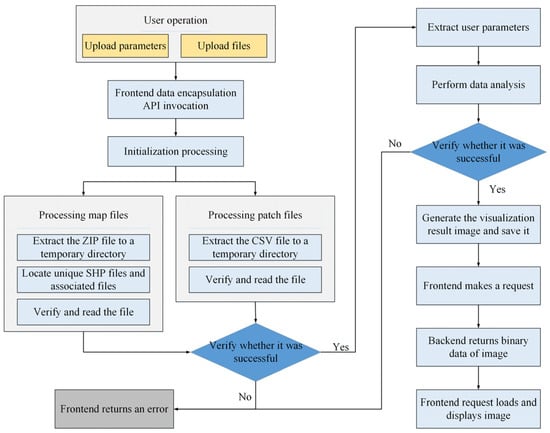

For Moran’s I and centroid trajectory analyses, the system provides a real-time analytical capability that processes user-uploaded files. This functionality is developed in Python (v3.8) using the Flask web framework to handle analytical requests, with the front-end invoking the back-end via standardized API calls. As shown in Figure 5, this design encapsulates complex spatial analysis logic within an accessible web interface, allowing non-specialist users to obtain actionable results efficiently by simple data uploads and parameter configuration, thereby democratizing access to advanced spatial analytical methods.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the spatial analysis function.

To effectively identify the spatial clustering patterns of “Two Illegalities” and accurately delineate genuine hotspot areas, this study employs Moran’s I as the computational method. Moran’s I comprises both global and local indices. Global Moran’s I describes overall spatial autocorrelation across the study area [27,28], whereas local Moran’s I identifies specific locations and types of spatial clusters at the level for individual spatial units [29,30].

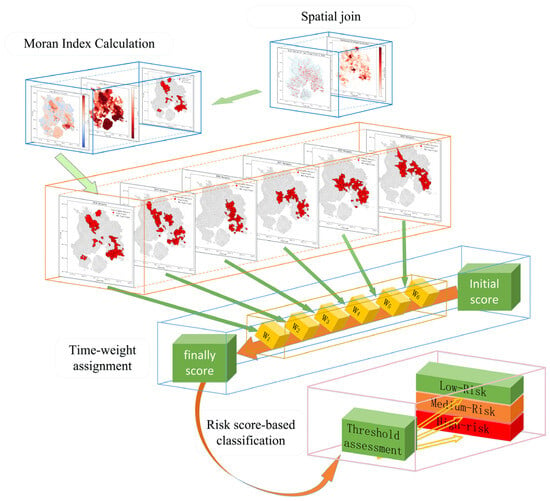

The established workflow for high-value cluster hotspot analysis is illustrated in Figure 6. It involves four stages: spatial join, Moran’s I calculation, time-weight assignment, and risk score-based classification.

Figure 6.

Hotspot analysis workflow.

Firstly, polygon data are converted to point features to reduce computational complexity, followed by spatial aggregation at the village level. Then, a spatial weights matrix is constructed to calculate both global and local Moran’s I indices, revealing region-wide spatial aggregation pattern and pinpointing of High-High (HH) clustering, respectively [31,32]. Subsequently, hotspots identified in different years are labeled and annual baseline scores are assigned to corresponding villages. After accounting for the time decay effect, a weighted overlay of scores for each village is conducted to obtain the final composite risk score. Based on these scores, villages are categorized into core high-aggregation zones, potential high-aggregation zones, and low-aggregation zones, with clear cartographic representation of these categories on the output maps.

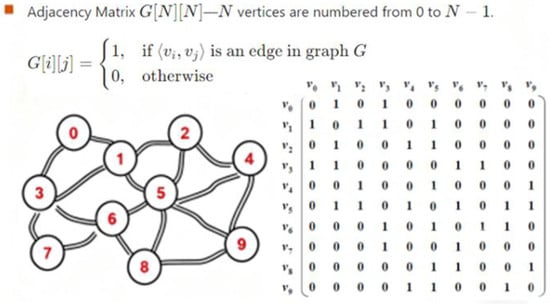

The Moran index commonly employs spatial weighting matrices based on adjacency criteria such as Rook (shared edges), Bishop (shared vertices only), and Queen (shared edges or vertices). Given the compact spatial distribution of villages in Xiamen and their complex boundary configurations, neighboring villages only share a single vertex (such as at the corner where three villages meet) rather than a complete edge. If connected using Rook criterion (which only recognizes edge-sharing neighbors), such diagonally adjacent villages would be excluded, resulting in an “incomplete” spatial weight matrix. To address this limitation, the Queen adjacency criterion was selected to capture these spatial relationships among villages [33]. As illustrated in Figure 7, this approach effectively captures finer-grained neighborhood relationships.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the first-order Queen contiguity spatial weight matrix. The red numbers in the left panel correspond to those in the matrix.

This study employs the centroid method to convert polygonal patches into point features. Direct spatial joining using raw parcel vector data typically results in inefficient computation due to excessive data volume and prolonged processing times. To optimize performance, vector patches are converted to point features prior to analysis. However, for irregularly shaped or large patches, the centroid may exhibit slight deviations from the actual locations of illegal constructions. As this study focuses on identifying villages exhibiting strong spatial clustering, minor positional shifts in illegal constructions exert negligible influence on village-level aggregation statistics.

To optimize performance, patch vectors are converted to point features prior to analysis. These point data are then spatially joined with administrative boundary vectors and subjected to row-standardized spatial weights to minimize the influence of varying numbers of neighboring units. Global Moran’s I is employed to evaluate the overall spatial autocorrelation of “Two Illegalities” parcel distribution across Xiamen City, calculated as follows:

where and are the attribute values of spatial units and , respectively; is the mean value of all spatial units; is the spatial weight between units and ; equals the total number of features; and is the aggregation of all spatial weights:

The calculated I represents the degree of global spatial autocorrelation. I > 0 indicates positive spatial autocorrelation, where similar values cluster in space. The magnitude of I reflects the strength of this clustering. Conversely, < 0 suggests negative spatial autocorrelation, representing a dispersed spatial pattern. When = 0, the spatial pattern is considered random, indicating no significant spatial dependence.

Building upon Global Moran’s I, Local Moran’s I is used to analyze the local spatial autocorrelation of attribute values for each observational unit and to identify the characteristics of spatial associations between them. The formula is as follows:

where and are the attribute values of spatial units and , respectively; is the mean value of all spatial units; is the total number of spatial units; is the spatial weight between spatial units and ; and is a standardization factor. A positive local Moran’s I value indicates positive local spatial autocorrelation between the attribute value of the unit and its neighboring units, while a negative value suggests a negative correlation. The calculated Moran’s I value alone cannot determine the statistical significance of the spatial autocorrelation. Typically, the standardized statistical score (Z-score) is used to assess significance [29]. The Z-score is calculated as follows:

where and represent the expected value and variance of , respectively. A permutation test with 999 replicates was conducted to calculate the significance probability (p-value). Statistical significance for hotspot identification was defined by p-value < 0.001 and Z-score > 1.96. To account for the influence of recent “Two Illegalities” activities on the hotspot assessment, an exponential decay model was applied to assign time-varying weights. It was assumed that more recent cases exert a greater impact on current spatial aggregation patterns. The weighting function is defined as follows:

The time weighting factor represents the weigh assigned to year t, spanning from the study period’s starting year t0 to the most recent year t1. An attenuation factor of α = 0.4 was selected to emphasize the risk contribution of recent hotspots within the current governance cycle while preserving the cumulative effect of historically high-incidence areas. This approach avoids the biases associated with extreme α values and was validated through sensitivity analysis. Finally, each village’s hotspot risk score is calculated based on annual weightings, with the risk formula defined as:

where represents the binary marker value of village i in year t, indicating whether it was identified as a high-value aggregation hotspot in that particular year. Then, based on the hotspot risk scores, the areas are correspondingly classified into high-risk zones, medium-risk zones, and low-risk zones.

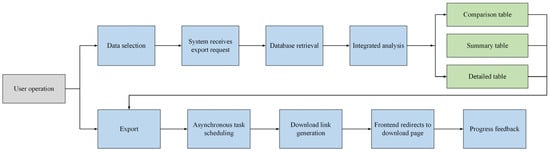

3.4. Customized Multi-Dimensional Report Generation

To effectively translate data analytics into actionable law enforcement measures, this study develops a customized reporting module. This module bridges underlying spatial data with high-level decision-making, transforming static land parcel records into multi-dimensional, dynamic reports that directly support governance actions. The workflow is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Workflow for generating summary and detailed reports.

Initially, users define the spatiotemporal scope and output format through the front-end interface. These parameters are transmitted via standardized API calls to activate the back-end data-processing engine. Subsequently, the system extracts the complete set of management attributes for the targeted land parcels from the MySQL operational database, forming a foundational dataset for report generation. Based on this dataset, the module simultaneously generates three types of customized analytical reports, each tailored to specific analytical perspectives and governance levels:

- (1)

- Summary Report: It aggregates statistical data by sub-district or town-level administrative units to support regional priority assessment. By analyzing the proportional distribution of both land parcel counts and affected areas across regions, it rapidly identifies the high-incidence zones of “Two Illegalities”, providing a foundation for the targeted allocation of law enforcement resources.

- (2)

- Detailed Report: It operates at the individual parcel level, providing precise, parcel-specific information to guide micro-level law enforcement actions. It detects concealed violations, such as discrepancies between approved planning areas and actual measured construction footprints that exceed regulatory thresholds, by comparative spatial analysis, thereby assisting subsequent verification.

- (3)

- Comparative Report: It conducts data comparisons for individual sub-districts across different time periods, enabling the quantitative assessment of policy implementation effectiveness.

4. Results

4.1. Integrated Multi-Source Data Visualization

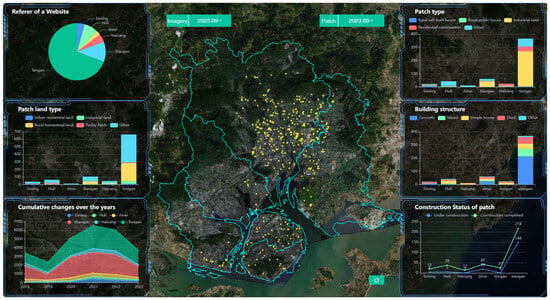

The system achieves integrated visualization and spatiotemporal querying of “Two Illegalities” parcel data. Figure 9 shows the parcel attribute visualization for September 2023. Users can select parcels from different periods via the central option panel to display their information. The interface simultaneously presents analytical charts for depicting the distributions of violation types, structural types, and land use classifications.

Figure 9.

System interface showing the visualization of integrated multi-source data. The middle panel shows the spatial distribution of “Two Illegalities” parcels (yellow dots) in Xiamen, China in September 2023. Surrounding panels show related data analyses.

The results clearly show that, during this period, the proportion of illegal parcels in Tongan District was far higher than in other districts, especially in the “under construction” category, highlighting the need for strengthened dynamic monitoring. Land use analysis based on spatial zoning of parcel locations indicates that industrial land is the primary type of illegal land use across all six districts, accounting for over half of the cases in each. Additionally, “Two Illegalities” on rural homesteads also constitute a significant proportion in Tongan and Xiangan Districts.

4.2. Refined Management of Comprehensive Land Parcel Archives

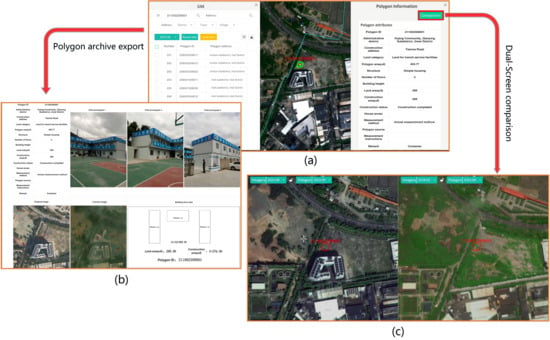

Utilizing multi-condition search and query functionalities, users can precisely locate parcels via unique identifiers or fuzzy searches based on address information. As shown in Figure 10a, selecting a specific parcel displays its geographic location on the base map alongside detailed attributes such as address, area, construction timeframe, land use, field photos, and multi-period comparative imagery.

Figure 10.

Spatial retrieval and associated information display for land parcels. (a) Spatial retrieval results; (b) complete archive for the parcel; (c) dual-screen multi-temporal comparison for the selected parcel.

The complete parcel archive is shown in Figure 10b. Clicking the comparison button opens a dual-screen interface (Figure 10c) that enables simultaneous visualization of 2D imagery for the same parcel across different time periods. This functionality provides intuitive support for identifying illegal construction activities, particularly cases of “reconstruction after demolition”, significantly improving verification efficiency and accuracy.

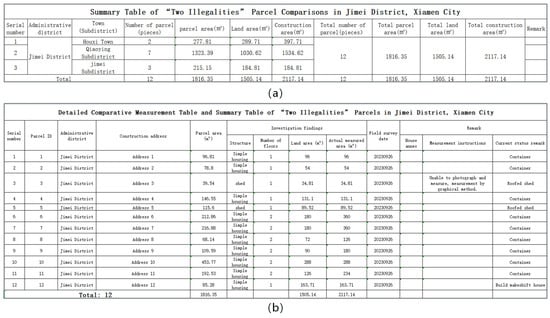

The system enables users to generate summary and detailed reports for parcels within any user-defined spatiotemporal range. Figure 11 displays the summary and detailed reports for illegal parcels found in Jimei District in September 2023. As shown in Figure 11a, only three sub-districts in Jimei District reported illegal construction activities during this period. These cases are characterized by low incidence counts but large spatial footprints. Specifically, Houxi Town recorded two parcels, Qiaoying Sub-district three, while Jimei Sub-district showed a relatively higher concentration with seven parcels, indicating an uneven regional distribution. Figure 11b reflects the actual situation of individual parcels within each sub-district, demonstrating the diversity of “Two Illegalities” manifestations. This diversity poses practical challenges for field investigation and evidence collection, requiring differentiated enforcement strategies based on the specific attributes of each parcel.

Figure 11.

Summary and detailed reports of “Two Illegalities” land parcels in Jimei District, Xiamen City for September 2023: (a) summary report; (b) detailed report.

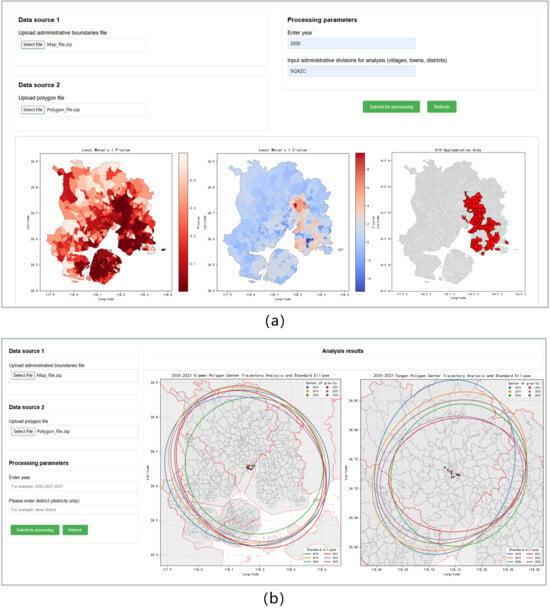

4.3. Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis of “Two Illegalities”

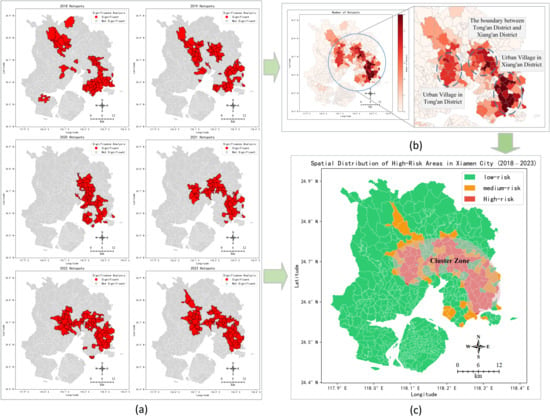

The system integrates Local Moran’s I and centroid trajectory analysis to provide a scientific basis for targeted remediation and proactive prevention of “Two Illegalities.” As shown in Figure 12a, users can upload a compressed package containing parcel SHP files and corresponding Comma-Separated Values (CSV) attribute tables, along with input parameters such as the target year and aggregation unit. Through simple parameter configuration, the system performs Local Moran’s I analysis, accurately identifying village-level units with statistically significant HH clustering and high significance. This allows for the delineation of annual priority remediation zones and provides data support for the prioritized allocation of enforcement resources.

Figure 12.

Visualization of (a) Local Moran’s I analysis and (b) centroid shift trajectory analysis of “Two Illegalities” land parcels in Xiamen.

Furthermore, the system integrates centroid trajectory analysis functionality. As illustrated in Figure 12b, by inputting target area and parcel information files, users can quickly obtain the migration paths of “Two Illegalities” activities for the entire region and specific target areas over recent years. This analysis helps identify spatial movement patterns and facilitates the preliminary determination of directional trends. Based on these insights, government departments can delineate “prevention and early-warning zones”.

To investigate the spatial pattern of “Two Illegalities” activities, this study utilized the system’s integrated analysis capabilities to conduct spatial statistical analysis. First, a global spatial autocorrelation analysis was performed on data from 2018 to 2023. The results in Table 2 show that the Moran’s I for all years passed the significance test, indicating a stable positive spatial correlation in the distribution of “Two Illegalities” in Xiamen throughout the study period, demonstrating significant spatial clustering patterns [34].

Table 2.

Global Moran’s I value for the study area from 2018 to 2023.

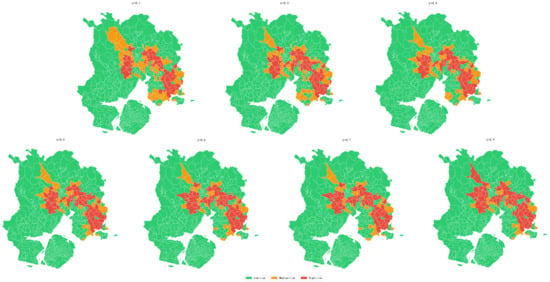

To verify the rationality of selecting α = 0.4, this study systematically evaluated the impact of different time decay coefficients on analysis results. First, a spatial visual comparison of classification results, as shown in Figure 13, indicates that under different α settings, the overall spatial pattern of risk levels remains stable: high-risk villages consistently exhibit clustered distribution; medium-risk villages form transitional zones on the periphery of high-risk villages; and low-risk villages dominate the remaining areas.

Figure 13.

Spatial visualization results for risk levels at different α values.

Second, using high-risk village proportion adaptability and core area coincidence as core evaluation indicators, Table 3 shows that when α = 0.4, the coincidence rate between high-risk villages and the core area reaches 71.7%. This covers most actual high-incidence villages without generating an excessive number of high-risk villages due to an overly α, which would dilute the concentration of the core area. The corresponding proportion of high-risk villages proportion is 9.5%, aligning with the enforcement strategy of “key remediation for the minority, routine supervision for the majority”.

Table 3.

Comparison of key risk classification indicators across different α values, with the core area defined as the top 60 villages ranked by total “Two Illegalities” incidents over the past two years.

Figure 14 displays the Local Moran’s I analysis and clustering results for Xiamen from 2018 to 2023. As shown in Figure 14a, during 2018–2019, high-value clustering exhibited multi-point diffusion and edge penetration: sporadic high-clustering parcels appeared simultaneously along urban–rural fringes and urban expansion frontiers, gradually spreading to surrounding areas. From 2020 to 2023, high-value clustering demonstrated range contraction and pattern fragmentation. Previously contiguous high-clustering areas in the core zone fragmented into dispersed parcels, and new high-clustering areas in peripheral regions decreased significantly. As shown in Figure 15, this can be verified.

Figure 14.

Spatial-temporal patterns of “Two Illegalities” activities in Xiamen (2018–2023): (a) Interannual variation in high-value clusters; (b) persistent high-value aggregation areas; (c) analysis of high-value hotspot clusters.

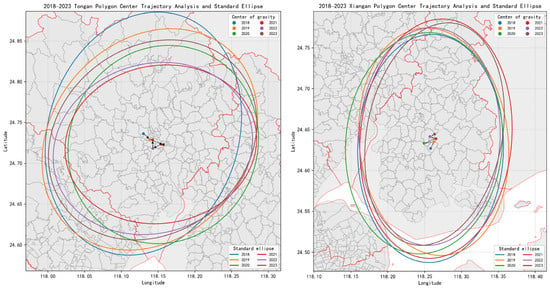

Figure 15.

Center of gravity shift trajectory of Tong’an District and Xiang’an District.

Moreover, annually identified high-clustering areas are mainly located in Tongan and Xiangan Districts, involving numerous villages. This is significantly less frequent in other regions. Figure 14b presents the recurrence frequency of hotspots for each village over the study period, revealing that they are mainly distributed in urban–rural transition zones such as Hongtang Town and Xiangping Sub-district in Tongan District, and the central-western parts of Xiangan District (e.g., Neicuo Town, Maxiang Sub-district, Xindian Sub-district).

As shown in Figure 14c, the spatiotemporal distribution of high-clustering hotspots from 2018 to 2023 indicates that high- and medium-risk areas are highly concentrated within the Tongan and Xiangan Districts, specifically within the agglomeration belt.

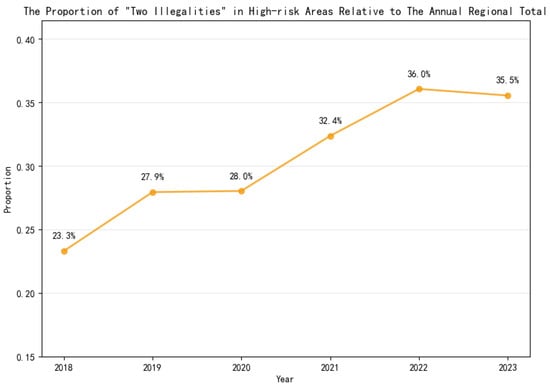

Furthermore, this study calculated the proportion of “Two Illegalities” in high-risk areas relative to the total volume across Xiamen City (Figure 16). The results show that this proportion increased significantly from 23.3% in 2018 to 36% in 2022, then declined to 35.5% in 2023. Combined with the findings from local Moran’s I analysis and gravity center trajectory analysis, this trend collectively indicates a spatial shift in “two violations” aggregations, which is from diffusion to contraction within core clusters.

Figure 16.

Proportion of “Two Illegalities” in High-Risk Areas relative to the total volume across Xiamen City (2018–2023).

Combining data from the Fujian Statistical Yearbook and relevant urban planning documents, this study further delineates the stage-specific spatial evolution characteristics of “Two Illegalities” below.

In 2018, HH clustering of “Two Illegalities” in Xiamen presented a dual-core pattern in the northwest and southeast, with core areas concentrated in the prohibited and restricted construction zones of Tongan and Xiangan Districts [35]. Marked disparities in enforcement intensity and development pressure were observed between the island and off-island areas, as well as among the four off-island districts, corresponding to pronounced gradients in urbanization rates. As shown in Table 4, Huli and Siming Districts (on the island) reached 100% urbanization [36], achieving region-wide control of “Two Illegalities” and the absence of statistically significant hotspots.

Table 4.

Urbanization rates of districts in Xiamen City.

Among the off-island districts, Haicang (91.1% urbanized) and Jimei (87.5% urbanized) recorded fewer “Two Illegalities” agglomeration spots, due to their limited rural land cover and advanced urban development. In contrast, Tongan (71.4% urbanized) and Xiangan (59.7% urbanized) retained vast rural areas and recorded a higher density of such agglomeration spots. In Tongan, “Two Illegalities” were concentrated in facility agriculture belts and urban–rural transition sections, where legacy violations coexisted with new infractions, characterized by sporadic unauthorized constructions and excessive homestead reconstruction in peripheral restricted zones. In Xiangan, “Two Illegalities” were dominated by urban village-related cases, forming a region-wide core hotspot.

During 2019–2020, driven by off-land expansion and industrial park upgrading, a Tongan–Xiangan interconnection zone emerged as a new development core for Xiamen, called the Tong-Xiang New Area [37]. Consequently, the “Two Illegalities” surged, and the hotspot clusters in the two districts gradually merged, forming a cross-regional “Two Illegalities” agglomeration belt.

From 2021 to 2022, influenced by adjustments in village spatial control policies and updated development plans, particularly to the revision of restricted construction zones [38], Tongan and Xiangan remained in a phase of rapid development. The contiguous expansion trend of the “Two Illegalities” agglomeration belt intensified, whereas no growth in such activities was observed in other regions.

In 2023, the agglomeration belt stabilized overall. Huli and Siming Districts remained free of statistically significant hotspots. Haicang’s urbanization rate rose to 100%, and Jimei’s rose to 91.16%. Neither of them showed evidence of spatial clustering “Two Illegalities”. Tongan’s urbanization rate increased to 76.23%, and Xiangan’s to 72.29%. “Two Illegalities” activities became concentrated in the agglomeration belt, with their scale gradually stabilizing and only minor fluctuations detected in surrounding areas.

5. Discussion

5.1. Application Value of the “Two Illegalities” Governance Platform

Addressing the multi-source, heterogeneous, and massive data in “Two Illegalities” scenarios, this paper proposes a standardized data-processing workflow.

First, data are input into a standardized data integration framework, which is independent of specific data sources. Key data standards include a unified spatiotemporal baseline adopting the CGCS2000 national geodetic coordinate system and standard timestamps, which is the basis for multi-period data comparison and a core data list requiring the integration of remote sensing imagery (resolution better than 1 m), administrative division vectors, and business data tables containing core attributes. Second, the system adopts a browser/server (B/S) architecture that enforces separation of concerns. Key technical services are provided via standard Python libraries, and a loose-coupled design ensures that individual modules can be independently upgraded or replaced. For example, other cities can migrate algorithm services from the current Flask to other microservice frameworks according to local computing environments without rewriting business logic. The separation of front-end and back-end also allows for customized visualization interfaces based on local needs.

Third, the “Data-Technology-Enforcement” tripartite collaborative mechanism formed in Xiamen’s practice involves the natural resource department providing basic data, the technical team responsible for platform support, and the urban management enforcement department leading business applications.

Furthermore, the platform strives to transform professional spatial analysis capabilities into tools that are intuitively understandable and easily operable for frontline governors. Specifically: First, the minimalist design of operational workflows. The platform encapsulates spatial statistical analyses like Moran’s I and centroid trajectories into a lightweight process of “uploading standard format files—selecting year and aggregation unit parameters—one-click execution”, allowing non-professionals to complete spatial analysis. Second, the visualization and intuitiveness of interaction and results. The platform enables dynamic switching of multi-period data via a time slider, provides dual-screen image comparison, and automatically converts analysis results into heat maps and statistical charts, transforming abstract spatial patterns into intuitive, decipherable decision-making information.

The management efficiency improvement realized by this platform is substantial. For instance, retrieving “Two Illegalities” building archives previously involved 9 departments and 12 types of data, taking 16 h; using the platform, this time is reduced to 4 h, an efficiency increase of 75% [38]. At the governance efficacy level, nearly 700,000 m2 of illegal construction was demolished city wide from January to May 2025 [39]. By identifying hotspots and generating remediation reports, this system provides key “targeted” support for such large-scale special actions, avoiding resource wastage [40]. At the micro-operational level, taking the specific action of demolishing 2458 m2 of illegal construction in Siming District in 2025 as an example [41], the refined management of “one parcel, one archive” and multi-period imagery comparison functions provided by the system effectively served high-frequency, scattered on-site disposal. To objectively evaluate the practical benefits of this platform compared to common technical routes, this system was compared with two typical solutions, as compared in Table 5. Although existing studies have not explicitly quantified response speed, this system demonstrates advantages in data presentation, technical architecture, and functional hierarchy while maintaining low deployment costs.

Table 5.

Comparison table of other systems with this system.

5.2. Underlying Mechanisms of the “Two Illegalities” Activities

The deep mechanisms underlying the spatial evolution of “Two Illegalities” can be summarized as the synergistic effect of multiple core dimensions, where differences in economic and urbanization development gradients are foundational drivers, and policy-enforcement synergy mechanisms are core regulatory factors. From an economic dimension, regional economic development levels and industrial structure differences directly determine the genesis scenarios and scale of “Two Illegalities”—mature economic regions have standardized industrial formats and orderly urban renewal, leaving narrow survival space for “Two Illegalities”; rapidly developing regions, driven by industrial expansion and surging housing demand for people’s livelihoods, superimposed on land resource constraints, catalyze “Two Illegalities” behaviors [42,43]. The policy-enforcement synergy mechanism permeates the entire governance process, forming differentiated regulatory effects: regions with better development foundations build a policy system of “regulating stock + strictly controlling increment”, paired with a service-oriented enforcement mode. Through efficient approval, cross-departmental collaboration, and flexible guidance, precise adaptation of policy and enforcement is achieved, curbing “Two Illegalities” at the source. In regions with lagging development, policies focus on resolving historical legacy issues, while enforcement relies mainly on rigid control and post-event punishment. The insufficient adaptation between policy and enforcement fails to channel hidden “Two Illegalities” demands, further solidifying the spatial distribution pattern of “Two Illegalities”.

The adaptability of multiple dimensions dominates the phasic transformation of “Two Illegalities” spatial morphology. In regions with mature urbanization and developed economies, abundant governance resources and a perfect, highly efficient policy-enforcement system enable smooth responses to various adjustments, maintaining a stable state of low “Two Illegalities” incidence [44,45]. In regions where rapid urbanization synchronizes with economic expansion, impacted by drastic urban–rural spatial transitions, poor connection during policy transition periods, and lagging enforcement modes, the adaptation among the three becomes unbalanced, easily leading to phasic rebounds in illegal construction.

In summary, the evolutionary trajectory of Xiamen’s “Two Illegalities” space from multi-core, cross-regional distribution to agglomeration belts during the study period is essentially the result of the dynamic adaptation of economic development gradients, urbanization stages, and policy-enforcement synergy mechanisms. The adaptability of these three directly determines the phasic transformation of “Two Illegalities” spatial morphology. These laws have universal applicability for cities with distinct urbanization gradients, prominent urban–rural dual structures, and unbalanced economic development. They provide theoretical reference and practical paradigms for similar cities to build highly adaptive policy-enforcement synergy systems based on their own economic and urbanization realities, identify incentives for high “Two Illegalities” incidence, and optimize governance paths, assisting in the realization of positive interactions between “Two Illegalities” governance, urban–rural integration, and high-quality economic development.

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

Although this study reveals the correlation between “Two Illegalities” distribution, urbanization gradients, and policy implementation based on spatial analysis and macroscopic statistical indicators, it fails to quantitatively integrate socio-economic drivers. Challenges include low accessibility and privacy concerns regarding micro-data such as income levels and population mobility and inconsistencies in statistical scope, time nodes, and spatial units of socio-economic data. These limit the research from crossing from “spatial pattern description” to “precise prediction.” Furthermore, the mechanism of “Two Illegalities” behaviors possesses complexity and spatiotemporal lag. Although “urban–rural transition zones” are identified as high-incidence areas, data limitations make it difficult to quantitatively answer whether “land acquisition compensation expectations”, “rental economy income”, or “weak grassroots governance resources” constitute the primary driver in a specific village. This forces the formulation of governance strategies to rely to some extent on qualitative experience.

In the future, as data foundations improve, spatial econometric models can be established to predict the spatiotemporal evolution trends of “Two Illegalities” risks under different scenarios, enhancing governance decision-making.

6. Conclusions

Addressing the demand for precision and efficiency in urban “Two Illegalities” governance, this study designed a GIS-based platform integrated with multi-source data management and spatial statistical analysis functionalities, using Xiamen City as a case study. Through systematic platform development and practical deployment, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- A standardized data integration framework featuring unified spatiotemporal baselines and core data catalogs, along with a modular open technical architecture, was constructed to tackle the challenges of multi-source, heterogeneous, and massive data in “Two Illegalities” governance. Based on Xiamen’s implementation experience, a tripartite collaborative mechanism of “Data-Technology-Enforcement” was formed, providing a reusable solution for cross-regional application and promotion;

- (2)

- A management platform was constructed, with integrated functionalities including spatiotemporal analysis visualization, parcel visualization, data analysis, multi-period imagery comparison, comprehensive query, parcel archive management, and customized report generation. Practical validation demonstrates that this platform improves governance efficiency by 75% compared with traditional manual management methods, lowers the operational threshold for non-professional users, and enhances the intuitiveness and scientific rigor of governance decision-making;

- (3)

- Based on the analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of “Two Illegalities” aggregation hotspots during the study period, high-aggregation zones have evolved from a multi-core diffusion pattern to a concentrated aggregation belt, which is spatially clustered in urban–rural transition zones. Statistical results show that the proportion of “Two Illegalities” activities in the identified 53 high-risk villages/streets relative to the annual city wide total in Xiamen increased by 12.2% over the study period. This evolutionary pattern is essentially an inevitable outcome of the dynamic interplay between regional economic development gradients, urbanization processes, and policy-enforcement synergy mechanisms. The underlying mechanisms provide a universal theoretical reference and practical paradigm for similar cities with distinct urbanization gradients and prominent urban–rural dual structures, enabling them to develop adaptive policy-enforcement systems and optimize the governance pathways for “Two Illegalities.”

Despite these contributions, this study is subject to limitations, particularly regarding the time lags in capturing “Two Illegalities” activities. Future research will focus on integrating real-time monitoring technologies such as drones and the Internet of Things (IoT) to build an integrated air-space-ground monitoring network. Additionally, machine learning models will be introduced to conduct multi-factor-driven risk prediction and simulation for “Two Illegalities”, further advancing the precision and proactivity of urban governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.H. and Y.Z.; software, C.L.; validation, C.L., Y.H., Y.J. and X.W.; formal analysis, C.L. and Y.J.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, Y.H. and Y.Z.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.H.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.K.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation Guiding Project (2024Y0057); Fujian Construction Science and Technology Research and Development Project (2025-K-66); Fujian Provincial Natural Resources Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Year 2025 (KY-100000-04-2025-023); and the Key Laboratory of Southeast Coast Marine Information Intelligent Perception and Application, MNR (No. 24201).

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions, which have vastly helped to improve the quality of the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bao, Y.; Du, H.; Huang, Z.; Ren, S.; Yin, G.; Mao, R. Assessing and Mitigating the Carbon Emissions from Illegal Urban Buildings: A Spatial Lifecycle Analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostankovich, V.; Afanasyev, I. Illegal Buildings Detection from Satellite Images Using GoogLeNet and Cadastral Map. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Funchal, Portugal, 25–27 September 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H. Legal and Illegal Processes of Building Disposal Under the Vision of Urban Planning. Open House Int. 2019, 44, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Xi, Z. Characteristics, Hazards, and Control of Illegal Villa (Houses): Evidence from the Northern Piedmont of Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 21059–21064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Mao, R. Towards Smart City Supervision: A Detection Pipeline for Illegal Buildings. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2026, 163, 113052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Shang, C.; Shen, Q. Remote Sensing Image-Based Building Change Detection: A Case Study of the Qinling Mountains in China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Governance Theory Improves the Remote Sensing Monitoring System of Illegal Land Use. Resour. Sci. 2013, 35, 561–568. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X. Can Land Market Development Suppress Illegal Land Use in China? Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Chai, J.; Wei, C. Spatial-Temporal Characteristics of Illegal Land Use and Its Driving Factors in China from 2004 to 2017. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, M.; Chen, C.-F.; Chiang, S.-H.; Chang, K.-T.; Lin, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chou, Y.-C. Illegal Land Use Change Assessment Using GIS and Remote Sensing to Support Sustainable Land Management Strategies in Taiwan. Geocarto Int. 2019, 34, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Su, M.; Eklou, J.; Lin, W.; Chen, P.; Cheng, N. Enhancing Efficiency of Handling Illegal Constructions Using the SOMCM Algorithm: A Case Study in Taipei. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2025, 39, 04025059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Peng, B.; Chen, B.; Liu, M.; Yu, W.; He, Y.; Ren, D. Multiscale Fusion Network for Rural Newly Constructed Building Detection in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9160–9173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelRahman, M.A.E. An overview of land degradation, desertification and sustainable land management using GIS and remote sensing applications. Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. Nat. 2023, 34, 767–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayilov, J.; Binnataliyeva, T. Application of Remote Sensing Techniques in the Construction and Management of Smart Cities. In International Conference on Smart Environment and Green Technologies—ICSEGT2024; Mammadov, F.S., Aliev, R.A., Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1251, pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, L.; Luo, N.; Xu, M. YMMNet: A More Accurate and Lightweight Detector of Illegal Buildings for Smart Cities. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 5866–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ouyang, D.; Yang, Y.; Yang, B. Monitoring and Governance of Illegal Urban Construction. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 3109–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R. Management and Application of Illegal Construction Data through Multi-Source Data Collaboration. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2022, 2, 286–290+321. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Q. Design and Application of Integrated Management Information System of Preventing and Controlling Illegal Construction. Urban Land Use 2017, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Zong, H.; Qi, C.; Amp, Q.S. Research and Practice on Fine Governance of Urban Illegal Construction. Urban Geotech. Investig. Surv. 2019, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Ma, W.; Ma, Z.; Fu, W.; Chen, C.; Yang, C.-F.; Liu, Z. Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing and a Monitoring Information System to Enhance the Management of Unauthorized Structures. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, C. Research on Intelligent recognition of Violation Based on Big Data of Urban Construction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Geomatics in the Big Data Era (ICGBD), Guilin, China, 15–17 November 2019; Volume XLII-3/W10, pp. 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yin, T. Mobile Application of Land Law Enforcement and Supervision. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Tan, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 135, pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- López-Casado, D.; Fernández-Salinas, V. The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain). Land 2023, 12, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikdeli, S. Investigation of the key factors influencing the urban building code violations in Mashhad, Northeastern Iran (2002–2022). City Territ. Archit. 2025, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, R. Illegal land use by Italian firms: An empirical analysis through the lens of isomorphism. Land Use Policy 2022, 121, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalambordezfooly, R.; Hosseini, F. Factors Affecting Illegal Land-use Changes in Residential Areas: (Case Study: District 6 of Tehran). J. Reg. City Plan. 2023, 34, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiamen Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://tjj.xm.gov.cn/tjzl/ndgb/202105/t20210527_2554550.htm (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Rahman, M.T.; Jamal, A.; Al-Ahmadi, H.M. Examining Hotspots of Traffic Collisions and Their Spatial Relationships with Land Use: A GIS-Based Geographically Weighted Regression Approach for Dammam, Saudi Arabia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xie, S.; Liu, F.; Tang, J.; Gong, L.; Liu, X.; Wen, T.; Wang, T. GIS-Based Assessment of Spatial and Temporal Disparities of Urban Health Index in Shenzhen, China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1429143. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Dai, J. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Evolution of Global World Cultural Heritage, 1972–2024. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazaymeh, K.; Almagbile, A.; Alomari, A.H. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Traffic Accidents Hotspots Based on Geospatial Techniques. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Stødle, K.; Flage, R.; Guikema, S.D. Identifying Power Outage Hotspots to Support Risk Management Planning. Risk Anal. 2025, 45, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, M. Mapping Spatial Inequity in Urban Fire Service Provision: A Moran’s I Analysis of Station Pressure Distribution. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Huang, Q.; Li, M.; Hu, W. Illegal Land Use Risk Assessment of Shenzhen City, China. J. Maps 2015, 11, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Planning. Available online: https://zygh.xm.gov.cn/zwgk/zdxxgk/ghcg/zxgh/202001/t20200113_2499452.htm (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Fujian Provincial Department of Industry and Information Technology. Available online: https://gxt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/xw/hydt/snhydt/202512/t20251202_7041124.htm (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Planning. Available online: https://zygh.xm.gov.cn/zwgk/zdxxgk/ghcg/zxgh/202305/t20230518_2759699.htm (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- People’s Daily Online. Available online: http://fj.people.cn/n2/2025/0919/c181466-41357092.html (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- People’s Daily Online. Available online: http://fj.people.cn/n2/2025/0528/c181466-41241802.html (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Xiangan District People’s Government of Xiamen City. Available online: https://www.xiangan.gov.cn/mlxa/ztzl/zqsk/gzls/202412/t20241220_1082954.htm (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Xiamen News. Available online: https://siming.xmnn.cn/jdgz/202409/t20240926_233121.htm (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Zhao, B.; He, X.; Liu, B.; Tang, J.; Deng, M.; Liu, H. Detecting Urban Commercial Districts by Fusing Points of Interest and Population Heat Data with Region-Growing Algorithms. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Liao, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Shao, G. Assessment of Ecological Risks Induced by Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Xiamen City, China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, B. Illegal Construction in China’s Urban Villages: Influence of Herding and Social Networks. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; He, Y.; Yu, P.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fan, M.; Lin, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Urbanization in the Xiamen Special Economic Zone Based on Nighttime-Light Data from 1992 to 2020. Land 2022, 11, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.