Abstract

This study analyzes the establishment of Local Agri-Food Systems (LAFSs) in the triple-border region between the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, by identifying and mapping potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production. An integrated analysis of data sources was treated, processed, and integrated into a common spatial support. Land use and land cover data were used from demographic and agricultural censuses, from the Rural Environmental Registry, agrarian reform settlement projects and conservation units. Our study revealed that 23.73% of the regional area has potential for peasant production, identifying four regions that stand out in terms of this potential. The area presented livestock and animal husbandry as the main agri-food chain, with potential for processing within the territory itself, in addition to extractive activities in the Atlantic Forest biome. The results indicate that there are possibilities for the establishment of LAFSs as a local development strategy associated with social inclusion and environmental responsibility, although there is a need to expand and strengthen the transportation and marketing channels for products from these short chains. The cartographies produced aim to contribute as auxiliary instruments to land use planning and management, seeking to strengthen LAFSs at different scales of governance.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, land use planning has faced the challenge of incorporating more integrated approaches capable of engaging with contemporary socioeconomic and environmental transformations. The International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning, published in 2015 by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme [1], address different territorial scales and emphasize the importance of promoting regional economies of scale and agglomeration. This aims to strengthen interactions between urban and rural spaces and to reduce the dichotomous logic traditionally associated with the urban–rural divide in planning structures. In this context, the concept of extensive urbanization [2] contributes to a holistic approach that acknowledges the complexity of contemporary socio-spatial forms and processes, which extend beyond the boundaries of cities.

The so-called Local Agri-food Systems (LAFSs) emerge as a concrete economic alternative for shaping territorial development plans, as they offer—at the scale of lived territories—an alternative to extensive national and global industrial supply chains. LAFSs consist of a structure in which food is produced, processed, and marketed within a defined geographical area [3], aiming to provide products that represent—or can represent—characteristics such as location, nature, health, and reliability [4].

These systems are composed of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs), which represent a new form of interaction between production and consumption by restoring knowledge of the product’s origin and its connection with the symbolic, cultural, and environmental values embedded in the production methods associated with the offered goods [5]. In this sense, LAFSs and SFSCs find one of their main expressions in peasant agriculture. Essential for food production, sustainability, and overall development [6], peasant agriculture plays a highly relevant role in shaping these short-chain agri-food systems.

Public policies related to land use planning must consider the specificities of each form of short supply circuit and comprehensively address the stages of production, intermediation, consumption, and their interconnections [7]. Furthermore, analyzing short supply circuits requires recognizing the particularities of local and regional contexts [8]. The concept of territory adopted is based on the definition proposed by the geographer Milton Santos. This approach was chosen due to its ability to offer a comprehensive and critical analysis of the territory. For Santos, territory is not merely a physical space, nor is it solely political, economic, social or cultural. The used territory is constituted by objects and actions continuously interacting [9]. This concept is related to local agri-food systems and land use planning, since there are constant interactions between the actors involved in these systems, such as farmers, organizations, public authorities, and consumers operating in different territories. As such, policies should be tailored to these diverse territorial realities to promote more effective and context-sensitive strategies. Territory must also be understood in a broad and systemic manner, integrating the physical and geographical environment as a fundamental component of both the productive structure and consumption patterns [10].

To make these production territories visible, cartographic tools are essential for effective land use planning. The International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning [1], by recognizing the territory as a structuring element of public policy, emphasize that local authorities should develop a shared and strategic spatial vision through the creation of appropriate mapping tools.

In this context, Local Agri-food Systems (LAFSs) and Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) offer concrete alternatives for strengthening urban–rural connections across different territorial settings and serve as strategic tools for land use planning. However, for these initiatives to be effectively scaled up, it is essential that they become the subject of studies and analyses that account for their specificities and challenges.

This study analyzes the establishment of Local Agri-Food Systems (LAFSs) in the triple-border region between the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, by identifying and mapping potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production and defining regions that stand out in terms of this potential. This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents Brazilian experiences and studies related to LAFSs and SFSCs; Section 3 outlines the materials and methods used; and the following sections present the results and discussion.

2. Background

Brazilian Experiences and Examples Related to SFSCs

The terms Alternative Agri-food Networks (AAFNs) and Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) have emerged more recently and have been predominantly examined by scholars from countries in the Global North, with particular emphasis on Europe [5]. The most prominent initiatives and civil society organizations structured as AAFNs are primarily found in the United Kingdom, other Western European countries, and North America [11]. However, these concepts are also applicable for analyzing and describing processes and phenomena in the Global South, particularly in countries such as Brazil [5].

Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) encompass various accepted definitions, each with its own focus, which can be summarized as follows: (1) bypassing stages of commercial intermediation to create a more direct connection between producer and final consumer; (2) reducing the geographical and cultural distance the product travels before reaching the consumer; and (3) strengthening the roles of both consumers and producers within the food supply chain. SFSCs have emerged as new models for rethinking food production and consumption, grounded in principles of environmental and social sustainability [12]. They contrast with conventional agriculture, which is characterized by capital-intensive systems and rooted in the mechanical–chemical–genetic paradigm [13].

In Brazil, beginning in the 1990s, studies began to focus on the processes of food production, processing, and domestic marketing. Research on rural family agro-industries initially concentrated on the southern region of the country but gradually expanded to the northern and northeastern regions as well. An analysis of the literature from recent decades reveals the development of a growing research agenda on short food supply chains in Brazil—even when the term itself is not always explicitly used [5].

Ploeg, Ye, and Schneider [14] present case studies that illustrate the emergence of peasant markets in southern Brazil. A notable example is the Southern Commercialization Circuit of the Ecovida Agroecology Network, established in 1998 to offer an alternative to the dominant agricultural model in the country. This network spans the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and the southern region of São Paulo [15]. According to the authors, this circuit draws a distinction between commerce and circulation, resulting in a redefinition of roles and social relationships. It is the peasant producers themselves who manage the network and control the flow of goods along the established routes. The first guiding principle of the circuit is to define both the origin and destination of the food, allowing only those products that cannot be produced locally or are out of season to be brought in. Additionally, only the portion of production that cannot be sold locally is transported and marketed elsewhere. The second principle seeks to minimize the number of transfers a product undergoes before reaching its final destination.

In the context of the Jequitinhonha Valley, located in the northeastern region of Minas Gerais, the Research and Support Center for Family Farming has been conducting studies on local street markets since 2000. Among the findings presented by Ribeiro et al. [16], a key observation is that each market displays unique characteristics, with the products offered varying according to the customs and specificities of each locality. In the small municipalities of the region, these markets are capable of supplying a significant portion of the population, particularly urban residents who seek food with a known and traceable origin.

In Brazil’s northern region, important studies have been carried out in the Amazon biome by the Center for Advanced Amazonian Studies at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). These studies aim to understand, characterize, and analyze the peasant economy linked to the biome—an economy rooted in the native forest and sociobiodiversity—by employing concepts such as production chains, Local Productive and Innovative Arrangements and Systems (APLIs), and value chains [17,18,19,20].

There are also initiatives led by the third sector that contribute to the development and consolidation of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs). One such example is the CaipiratechLAB project, developed by Silo1, which aims to “create and expand opportunities for young peasants to live, work, and reconnect with rural life, becoming agents of change in their communities” [21]. As part of this program, a free digital platform was developed to provide training, communication, and sales opportunities specifically tailored for farmers and processors in the family farming sector within the triple-border region of the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. The agri-food production sites featured on the platform have been mapped by Silo since 2020 and present a diverse range of food products, including fresh items such as vegetables, fruits, dairy, meat, mushrooms, herbs, and honey, as well as processed goods such as cheese, sweets (jams, fruit compote, dulce de leche, and cakes), flour, bread, and more.

In the examples of SFSCs mentioned, the initiatives were developed by producers themselves, consumers, and/or other civil society actors. However, in the Brazilian context, public food procurement programs also play a prominent role, particularly the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (PNAE).

The PNAE is considered the largest school feeding program in Latin America, based on factors such as its longevity, continuity, institutional commitment, universality of service, total number of students served, and the volume of financial resources invested [22]. Since its early inception in the 1950s, the development of what is now known as PNAE has evolved in response to Brazil’s socio-political and economic landscape. A significant milestone occurred in 2009, when Law No. 11.947 established that at least 30% of transfers from the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE) must be allocated to purchasing products from family farming producers, preferably from within the municipality or nearby regions. This policy created a promising interface between school feeding and local production by opening institutional market opportunities that had previously been largely inaccessible to family farmers [23].

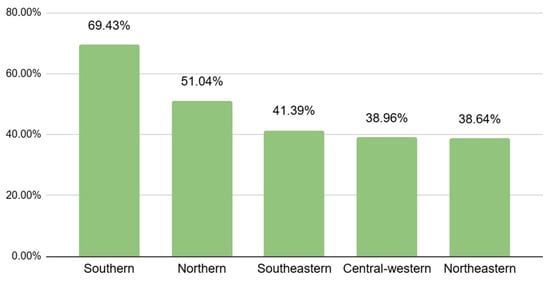

Despite legislative advances that have strengthened the connection with family farming, the implementation of this policy has encountered various tensions and challenges. Data analysis [24] reveals significant spatial inequalities in the procurement of food for school meals (Figure 1). In 2022, the national average for purchases from family farming producers was 45.15%. However, a considerable variation emerges when comparing percentages across Brazil’s regions and municipalities. The southern region of the country recorded the highest average, at 69.43%, followed by the northern, southeastern, central-western, and northeastern regions.

Figure 1.

Percentage of food procurement from family farming by region in 2022.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

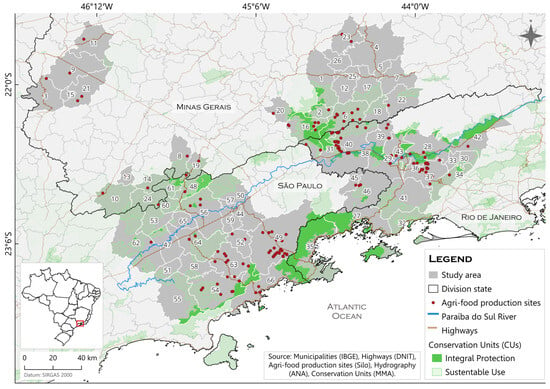

The study area encompasses a total of 66 municipalities surrounding the triple-border region between the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo (Figure 2). Specifically, the area includes 26 municipalities in Minas Gerais, 17 in Rio de Janeiro, and 23 in São Paulo. The selection of municipalities began with those where agri-food production areas had been previously mapped by Silo, which confirmed the presence of producers in the territory. When addressing Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs), the delimitation was expanded to consider a broader territory of possibilities for these chains. This expansion was based on the principle that “things closer to each other are more similar than things farther apart” [25]. Therefore, neighboring municipalities of the selected ones were included to ensure greater territorial continuity and to better capture the dynamics involved in these chains.

Figure 2.

Study area in the triple-border region between the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Municipalities: 1. Aiuruoca, 2. Alagoa, 3. Andradas, 4. Andrelândia, 5. Arantina, 6. Bocaina de Minas, 7. Bom Jardim de Minas, 8. Brazópolis, 9. Caldas, 10. Camanducaia, 11. Campestre, 12. Carvalhos, 13. Córrego do Bom Jesus, 14. Gonçalves, 15. Ibitiúra de Minas, 16. Itamonte, 17. Liberdade, 18. Passa Vinte, 19. Piranguçu, 20. Pouso Alto, 21. Santa Rita de Caldas, 22. Santa Rita de Jacutinga, 23. São Vicente de Minas, 24. Sapucaí-Mirim, 25. Seritinga, 26. Serranos, 27. Angra dos Reis, 28. Barra do Piraí, 29. Barra Mansa, 30. Engenheiro Paulo de Frontin, 31. Itatiaia, 32. Mangaratiba, 33. Mendes, 34. Paracambi, 35. Paraty, 36. Pinheiral, 37. Piraí, 38. Porto Real, 39. Quatis, 40. Resende, 41. Rio Claro, 42. Vassouras, 43. Volta Redonda, 44. Aparecida, 45. Arapeí, 46. Bananal, 47. Caçapava, 48. Campos do Jordão, 49. Cunha, 50. Guaratinguetá, 51. Jambeiro, 52. Lagoinha, 53. Monteiro Lobato, 54. Natividade da Serra, 55. Paraibuna, 56. Pindamonhangaba, 57. Potim, 58. Redenção da Terra, 59. Roseira, 60. Santo Antônio do Pinhal, 61. São Bento do Sapucaí, 62. São José dos Campos, 63. São Luiz do Paraitinga, 64. Taubaté, 65. Tremembé, 66. Ubatuba.

The total area of the selected municipalities is 28,060.84 km2. The largest municipality in terms of territorial extension is Cunha, located in the state of São Paulo, with 1407.25 km2, while the smallest is Potim, also in São Paulo, with 44.64 km2. According to data from the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MMA), Conservation Units (CUs) cover 38.67% of the total area of these municipalities. Of the 10,851.72 km2 designated as Conservation Units, 2430.8 km2 (22.4%) fall within Integral Protection Units, and 8420.9 km2 (77.6%) within Sustainable Use Units.

According to data from the 2017 Agricultural Census [26], the municipalities within the study area comprise a total of 29,572 Agricultural Establishments (AEs). Of these, 20,689 (approximately 70%) are classified as family farming units. In Minas Gerais, 12,672 out of 15,882 establishments are dedicated to family farming. In Rio de Janeiro, the figure is 3252 out of a total of 5963, while in São Paulo, 4765 out of 7727 agricultural establishments fall under the category of family farming.

Livestock and animal husbandry represent the primary activity in the Family Farming Agricultural Establishments (EAAFs) of the municipalities in Minas Gerais, being practiced in 61.26% of them [26]. Notable exceptions include the municipalities of Andradas, Campestre, and Ibitiúra de Minas, where the cultivation of permanent crops is predominant. A similar pattern is observed in the municipalities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, where livestock and animal husbandry are the main activities in 61.22% and 75.82% of establishments, respectively. Exceptions include Paracambi/RJ, Mangaratiba/RJ, and Mendes/RJ, as well as Ubatuba/SP, where permanent crops are more prevalent. In Campos do Jordão/SP and Santo Antônio do Pinhal/SP, horticulture and floriculture stand out as the most prominent activities [26].

Although located in different states, the municipalities within the study area all share the presence of the Atlantic Forest biome (Mata Atlântica). To varying degrees, the historical occupation and deforestation of this native forest have been primarily driven by land use and occupation dynamics, influenced by the gold and coffee economies, the expansion of agriculture and livestock, and the processes of urbanization and industrialization [27,28,29].

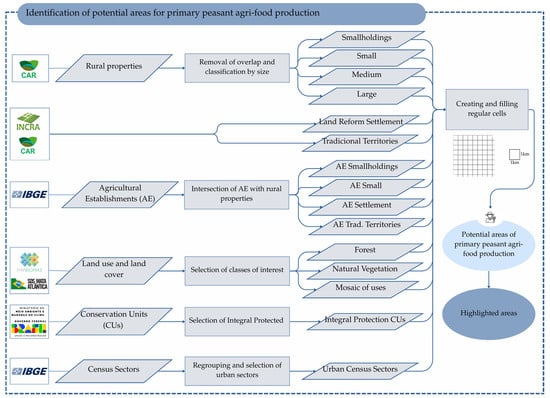

3.2. General Methodological Flowchart

Figure 3 presents the processes carried out for the identification of areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production and the definition of highlighted areas in terms of this potential.

Figure 3.

General Methodological Flowchart for the identification of potential areas for primary peasant agri-food production.

3.3. Data Collection

The selection of data for Stage 1 of this research is based on premises associated with the peasant mode of production (Table 1). Auxiliary data that are open and available for the entire national territory can be used as indicators of the existence of these potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production. The rural properties from the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) [30] maintained by the Brazilian Forest Service (SFB), the Agricultural Establishments from the National Address Registry for Statistical Purposes (CNEFE) [31] maintained by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the land reform projects [32] from the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), the Integral Protection Conservation Units (UCs) [33] from the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MMA), and the land use and land cover classes from Mapbiomas [34] and SOS Mata Atlântica [35] were used to identify these areas.

Table 1.

Data sources and their respective justifications for identifying areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production.

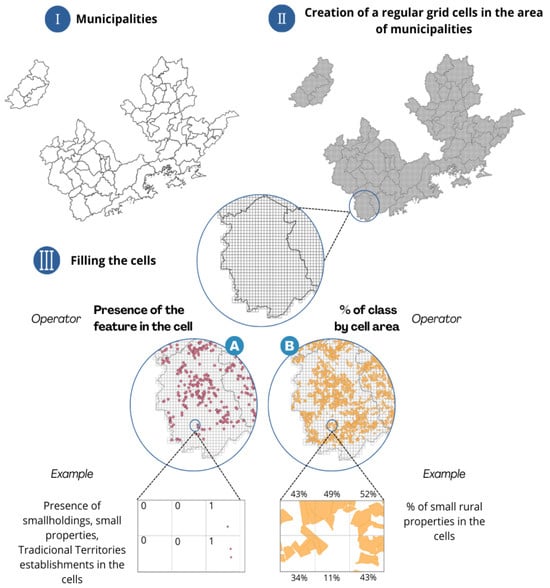

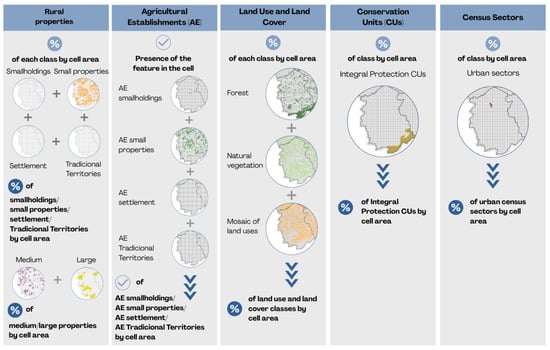

3.4. Filling of Regular Grid Cells

After processing the data, the generated variables were integrated into a regular grid of 1 km × 1 km cells (Figure 4). The transformation of the geometric support of the original data aims to standardize information from different sources and geometries (vector, raster, and other cell-based data formats) into a single spatiotemporal base [46]. The choice of cell size was guided by the core objective of the research: the identification of areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production. This resolution proved to be more appropriate as it allows for a more detailed spatial reading, capable of detecting small-scale production activities associated with the peasant mode of production.

Figure 4.

Creation of regular grid cells in the municipalities of the study area and examples of filling them in. Situation A demonstrates the use of the feature presence operator in the cell. As an example, it presents agricultural establishments classified as smallholdings, small properties and Traditional Territories, represented by the point feature in pink. In this case, the value 0 indicates the absence of the feature in the cell, while the value 1 indicates its presence, regardless of the absolute number of occurrences. Situation B exemplifies the use of the class percentage operator by cell area. The example shows the proportion of the area occupied by small rural properties within each cell, represented in orange.

The statistical operators used for populating the cells were the percentage of each class by cell area, which represents the proportion that each class occupies in relation to the total area of the cell, and presence, which indicates whether a given feature is present in each cell.

The data were aggregated into cells to result in the following variables: (1) percentage of rural properties classified as smallholdings, small farms, settlements, and traditional territories per cell area; (2) percentage of medium and large rural properties per cell area; (3) presence of agricultural establishments classified as smallholdings, small farms, in settlements and in traditional territories; (4) percentage of land use and land cover classes per cell area; (5) percentage of Integral Protection Conservation Units (CUs) per cell area; (6) percentage of urban census tracts per cell area. Figure 5 presents a summary of the operators employed to populate the cells and the resulting variables.

Figure 5.

Summary of the operators used to fill the cells and the resulting variables for the identification of primary peasant agri-food production.

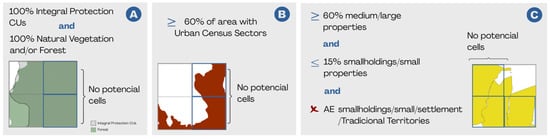

3.5. Classification of Cells Based on the Potential for Peasant Primary Production

Based on the variables aggregated within each spatial analysis cell, an evaluation was conducted to identify characteristics that could limit or prevent the development of primary peasant production (Figure 6). As a result, cells presenting any of the following conditions—referred to as Situations A, B, or C—were classified as non-potential areas.

Figure 6.

Situations in which the cell was classified as not potential for peasant production. (A) Shows an example of two cells classified as non-potential, as they contain 100% natural vegetation or forest (green color) and are entirely located within Integral Protection CUs (hatched area). (B) Shows two cells classified as non-potential, with more than sixty percent of their area occupied by urban census sectors (red color). (C) Shows three examples of non-potential cells that contain a percentage greater than 60% of medium rural properties, do not have smallholdings or small properties and do not have agricultural establishments in traditional territories, settlements, smallholdings or small properties.

- Situation A: Refers to areas located within Integral Protection Conservation Units (CUs), which are primarily intended for biodiversity preservation. These territories are typically covered by native forest and natural vegetation, emphasizing the need for environmental protection. Such restrictions significantly limit the viability of primary peasant activities.

- Situation B: Concerns areas experiencing urban expansion, which may lead to real estate pressures and land use conflicts. These dynamics make it unfeasible to sustain or establish peasant practices. Furthermore, access to natural resources in such areas tends to be more limited, undermining the continuity of traditional agricultural livelihoods.

- Situation C: Applies to areas where medium and large rural properties account for more than half of the cell’s territory. This land concentration may lead to potential conflicts between large-scale and small-scale producers. It can obstruct the development of peasant practices by limiting access to land and essential resources needed to maintain their production systems and way of life.

Next, decision rules were established based on the selected variables, the characteristics of the study area, and a review of relevant literature on the identification of areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production. The degree of potential was classified into six levels: very high, high, good, medium, low, and very low (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Peasant potential—No potential, very low, low, medium, good, high and very high.

Cells with higher percentages of smallholdings and small rural properties, in combination with the presence of settlements and traditional territories, high values for land use and land cover classes, and the presence of agricultural establishments associated with small-scale production, indicate greater potential for primary peasant activities. Conversely, as the proportion of these favorable variables decreases—and/or the percentage of medium and large rural properties increases—the potential of a given cell to support peasant production also declines. The complete set of decision rules, structured as pseudo-code (a mix of natural language and programming logic used to represent rule-based reasoning), is available in Supplementary Materials (Table S2).

After identifying the areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production, the next step was to determine the most prominent areas in terms of this potential. The selection of municipalities was based on the absolute number of cells classified as having very high, high, or good peasant potential, the proportion of these cells relative to the total area of each municipality and the Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) method [47,48]2.

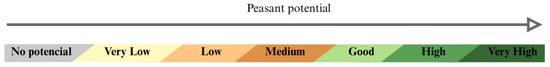

3.6. Observation Panel

To guide these analyses of the area with potential for primary peasant agri-food production, an Observation Panel was adopted. This tool is designed to explore complex processes and phenomena through an integrative approach. It is composed of a set of graphical representations—including images, diagrams, photographs, maps as and tabular formats [49,50]. Figure 8 shows the Observation Panel with seven sets of elements described below:

Figure 8.

Seven sets for interpreting the Observation Panel. I—Municipalities within the Area, II—Area Information; III—Number of potential areas; IV—Percentage of potential areas; V—Dimensions used to determine potential areas for peasant primary production; VI—Family farming establishments and VII—Microenterprises in the agricultural sector.

- I—Municipalities within the Area, with the spatial distribution of potential areas for primary peasant agrifood production;

- II—Area Information: location, total area, and population;

- III—Number of potential areas (very high, high, good) per municipality;

- IV—Percentage of potential areas (very high, high, and good) in relation to the total area of the municipality;

- V—Dimensions used to determine potential areas for peasant primary production: area in km2 of land use and land cover classes, number of agricultural establishments (small and small farms), and the area in km2 of small, small, medium, and large rural properties;

- VI—Family farming establishments: percentage of the total number of agricultural establishments in the municipalities of the Area and the main activities carried out;

- VII—Microenterprises in the agricultural sector: total number of CNPJs (Brazilian Corporate Taxpayers’ Registry) for primary and processing activities and the main activities carried out.

4. Results

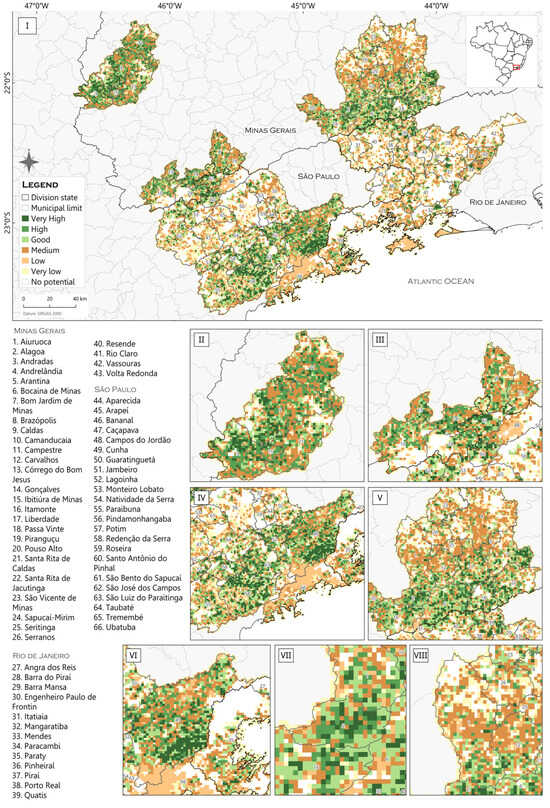

Out of a total of 29,946 spatial analysis cells, 5.1% (1526) were classified as having very high potential for primary peasant agri-food production, while 7.4% (2205) were classified as high potential, and 11.23% (3355) as good potential. An additional 21.3% (6369) were classified as medium potential, 10.67% (3185) as low potential, and 18.5% (5537) as very low potential. Finally, 25.66% (7660) of the cells were identified as non-potential areas. The spatial distribution of these classifications is presented in Figure 9, which illustrates the cartography of areas with potential for primary peasant agri-food production.

Figure 9.

Potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production. I—Potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production throughout the study area, II—Municipalities of Andradas, Caldas, Campestre, Ibitiúra de Minas and Santa Rita de Caldas, III—Border between Minas Gerais and São Paulo, IV—Area close to the coast of São Paulo, V—Border between Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, VI—Cunha (SP) and Paraty (RJ), VII—Alagoa (MG), VIII—Aiuruoca (MG).

By summing the cells classified as having very high, high, and good potential, the municipality of Cunha (São Paulo) stands out with the highest absolute number 690 cells, representing 47.26% of its total area. It is followed by Natividade da Serra (SP), with 435 cells (51.48%), and Caldas (Minas Gerais), with 339 cells (46.19%). In fourth place is Bocaina de Minas (MG), with 319 cells, which corresponds to 62.92% of the municipality. São Luiz do Paraitinga (SP) ranks fifth, with 262 cells, representing 42.39% of its territory.

When focusing specifically on the proportion of potential areas relative to each municipality’s total area, Alagoa (MG) ranks first, with 67.46% of its territory identified as having very high, high, or good potential. It is followed by Bocaina de Minas (MG) with 62.92%, Ibitiúra de Minas (MG) with 57.97%, Santo Antônio do Pinhal (SP) with 56.06%, and Passa Vinte (MG) with 52%.

Maps II, III, IV and V shows the areas with the highest concentrations of very high, high, and good potential cells. In map VI we see the municipality of Cunha (SP), which has the largest number of potential cells alongside Paraty (RJ), with a significant number of potential cells due to the presence of protected areas and large rural properties. Map VIII displays the municipality of Aiuruoca (MG), which has a unique configuration in the distribution of cells, a greater number of no potential cells in the north, medium potential in a more central area, and a concentration of very high, high, and good potential cells in the south.

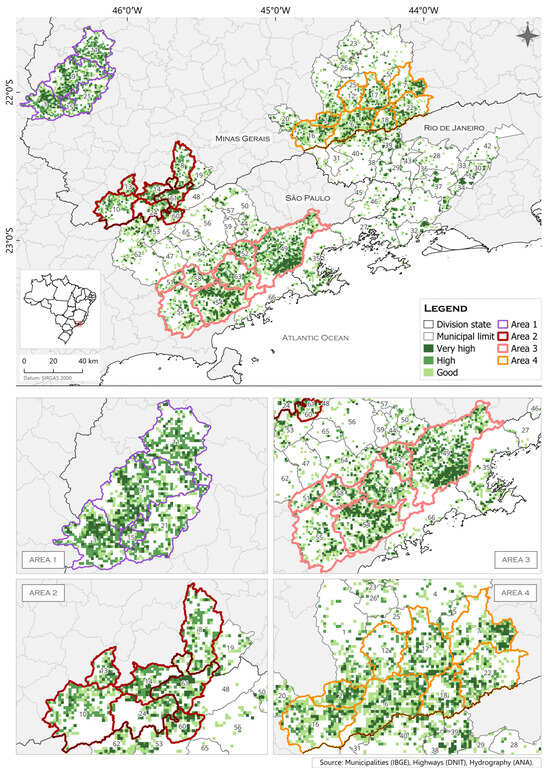

The definition of highlighted areas (Figure 10) was based on a more restrictive territorial scenario, which included only municipalities where the proportion of areas with peasant potential exceeded 25% of the total municipal territory. Under a more optimistic scenario, additional municipalities could also be considered—even those with lower proportions—in order to recognize and encourage emerging peasant initiatives that demonstrate potential for growth and consolidation. While alternative groupings of municipalities may be explored in future studies, the current approach seeks to contribute to the identification of priority areas according to the parameters established in this scenario, thereby facilitating the formulation of effective land use planning strategies.

Figure 10.

Highlighted areas of the peasant primary agri-food production. Area 1—Andradas (3), Caldas (9), Campestre (11), Ibitiúra de Minas (15), Santa Rita de Caldas (21). Area 2—Brasópolis (8), Camanducaia (10), Córrego do Bom Jesus (13), Gonçalves (14), Santo Antônio do Pinhal (60), São Bento do Sapucaí (61), Sapucaí-Mirim (24). Area 3—Cunha (49), Jambeiro (51), Lagoinha (52), Natividade da Serra (54), Paraibuna (55), Redenção da Serra (58), São Luiz do Paraitinga (63). Area 4—Alagoa (2), Carvalhos (12), Bocaina de Minas (6), Bom Jardim de Minas (7), Itamonte (16), Liberdade (17), Passa Vinte (18), Santa Rita de Jacutinga (22).

The first highlighted area is located in Minas Gerais and includes the municipalities of Andradas, Caldas, Campestre, Ibitiúra de Minas, and Santa Rita de Caldas. The second area covers municipalities across both Minas Gerais and São Paulo, including Brasópolis (MG), Camanducaia (MG), Córrego do Bom Jesus (MG), Gonçalves (MG), Santo Antônio do Pinhal (SP), São Bento do Sapucaí (SP), and Sapucaí-Mirim (MG). The third area consists of coastal-adjacent municipalities in São Paulo, specifically Cunha, Jambeiro, Lagoinha, Natividade da Serra, Paraibuna, Redenção da Serra, and São Luiz do Paraitinga. The fourth and final area comprises municipalities in Minas Gerais: Alagoa, Carvalhos, Bocaina de Minas, Bom Jardim de Minas, Itamonte, Liberdade, Passa Vinte and Santa Rita de Jacutinga.

This study chose to focus exclusively on Area 3 in order to examine its primary agri-food production and processing activities, the status of municipal participation in the National School Feeding Program (PNAE) regarding procurement from family farming, as well as to highlight examples of primary production in the territory and existing farmer organization initiatives. Among the four areas of interest identified in this research, Area 3 was chosen for the following reasons: (a) it presents significant primary agrifood production linked to extractivism in the Atlantic Forest biome, with emphasis on products such as the juçara palm fruit, pine nuts, and Cambuci; (b) it has relevant examples of organizations and associations focused on developing local production; (c) it has diagnosis of farmer organizations and collectives, provided by Akarui, which presents the main agricultural and processing activities carried out, as well as the main marketing channels used by farmers. This diagnosis, together with data from the Agricultural Census and microenterprises, contributed to the identification of the area’s main productive characteristics; (d) in relation to the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), the choice of Area 3 is also justified by the presence of municipalities with different levels of food acquisition from family farming, such as Cunha (7.72%) and Paraibuna (57.7%), enabling a comparative analysis between different realities.

5. Discussion

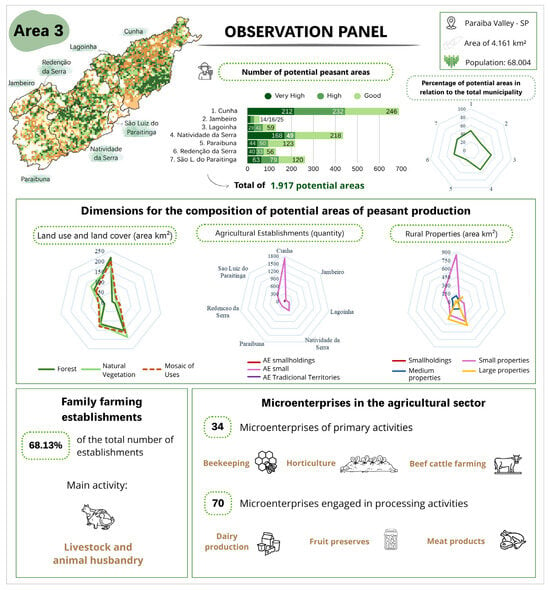

The area under study (Figure 11) is situated on the hills and backlands of the Serra do Mar, along the Paraíba do Sul River Basin, and includes the municipalities of Cunha, Jambeiro, Lagoinha, Natividade da Serra, Redenção da Serra, and São Luiz do Paraitinga.

Figure 11.

Observation Panel for Area 3—Cunha, Jambeiro, Lagoinha, Natividade da Serra, Paraibuna, Redenção da Serra and São Luiz do Paraitinga.

The environmental history of the municipalities within the region known as Vale do Paraíba is marked by extensive deforestation in mountainous areas for coffee cultivation, pasture establishment, and eucalyptus plantations. These activities significantly altered the original Atlantic Forest vegetation, leaving only a few large and well-preserved remnants [51].

The historical trajectory of Natividade da Serra and Redenção da Serra also includes episodes of forced displacement of rural producers—particularly during the 1970s, when the construction of dams in Paraibuna, São Luiz do Paraitinga, Santa Branca, and Jaguari led to the flooding of rural properties. As a consequence, many producers migrated to urban centers, while others redirected their activities toward large-scale eucalyptus cultivation and livestock farming [51,52,53].

According to the 2017 Agricultural Census [26], 68.13% of the total agricultural establishments in the area are associated with family farming. Among the main activities, livestock farming—especially cattle raising—is the most prominent. A survey of microenterprises in the agricultural sector identified 34 registered businesses (CNPJs) related to primary production, with beekeeping as the leading activity, followed by horticulture and beef cattle farming. In terms of processing activities, there are 70 registered CNPJs, with four primary sectors standing out: the production of dairy products, fruit preserves, meat products, and cocoa- and chocolate-based goods.

In this area, extractivist activities involving native species of the Atlantic Forest are also present, including the harvesting of pinhão (Araucaria seeds), cambuci, and juçara palm fruit. Within this context, several institutions have developed initiatives focused on the sustainable use of these resources as part of broader strategies for Atlantic Forest conservation. For example, Akarui3 implements projects aimed at promoting the sustainable management of the juçara palm fruit. The Auá Institute4 created the Cambuci Route, an initiative that seeks to revitalize the cultural heritage associated with this native fruit. Similarly, the organization SerraAcima5 has launched a project to enhance the value of the pinhão production chain.

The presence of these activities, closely linked to the Atlantic Forest biome, reinforces the potential of Local Agri-food Systems (LAFSs) to leverage sociobiodiversity. These systems contribute to the integration of environmental conservation, income generation, and the social inclusion of rural families [54]. This perspective is further illustrated in the study by [55], which proposes the inclusion of juçara fruit pulp in school meals in the municipality of Caraguatatuba, São Paulo. This initiative exemplifies a strategy to add value to local food production within the dynamics of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs).

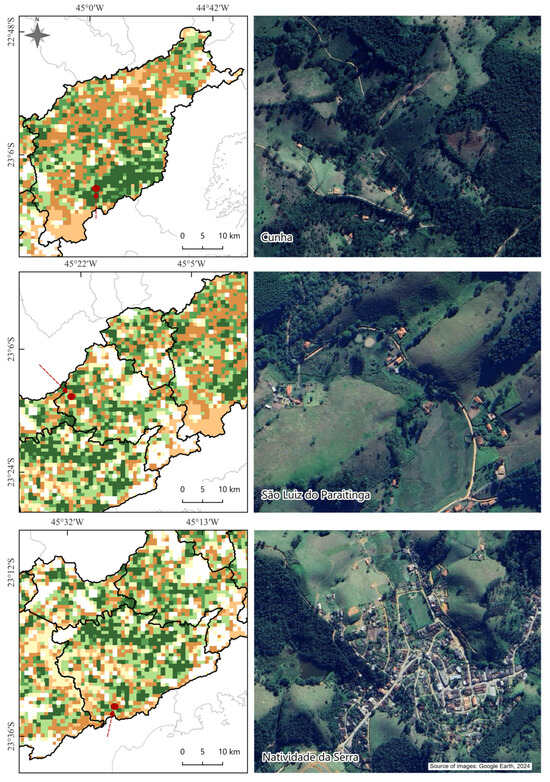

Figure 12 shows three examples of primary agri-food production in the territory. The Area A is located in the municipality of Cunha (SP) in a very high potential cell, with the presence of primary agricultural microenterprises, such as beekeeping and cattle raising, as well as an agrifood production site mapped by Silo. Area B is located in São Luiz do Paraitinga, in a high potential cell, where there is a production site mapped by Silo. Area C, in a periurban area, is located in a high potential cell, with the presence of primary horticulture and cattle raising microenterprises.

Figure 12.

Examples of primary peasant agri-food production in the municipalities of Cunha (SP), São Luiz do Paraitinga (SP) and Natividade da Serra (SP). The arrows and red dots indicates the location of the image area on the map.

Among the farmer collectives participating in the Agroecology Network of the Vale do Paraíba in this area, the following were identified: the Minhoca Agroecological Partners Association (São Luiz do Paraitinga), individual farmers from Cunha, and the Association of Agroecological Producers of Cunha. In a diagnostic study of the organizations and farmer collectives participating in the Agroecology Network of the Vale do Paraíba, conducted in 2024 [56], the main agricultural activities carried out by these collectives were identified as: dairy and beef cattle farming, fruit cultivation (native and exotic species), beekeeping, chicken farming for egg production, Agroforestry Systems (SAFs), vegetable farming (olericulture), mushroom cultivation, and pig farming. In terms of processed products, the collectives produce a wide variety of items, including dairy derivatives, jams and preserves, sauces, honey, pickled foods, cornmeal and flours, tinctures, and essential oils, among others.

Given this context, the potential of these municipalities becomes evident in the construction and consolidation of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) that encompass both primary production and product processing. These initiatives reflect the ability of local actors to integrate diverse agricultural practices with value-added transformation processes. The sales channels utilized by these collectives are equally diverse and include institutional programs such as the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), as well as door-to-door sales, Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) schemes, food basket deliveries, distribution centers (e.g., Ceagesp and Ceasa), local supermarkets, restaurants, and agroecological markets.

An analysis of 2022 data from the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE) [24] on the procurement of food products from family farming by the municipalities revealed that only São Luiz do Paraitinga reported purchases from family farming, with a recorded percentage of 34.34%. In contrast, the remaining municipalities in the study area—Cunha, Lagoinha, Natividade da Serra, Paraibuna, and Redenção da Serra—did not report any purchases from family farming in that year.

To determine whether this situation persisted in previous years, data from 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 were reviewed. The analysis revealed that Natividade da Serra and Paraibuna reported purchases from family farming in 2019, with recorded rates of 52.6% and 57.7%, respectively. In contrast, Cunha, Lagoinha, and Redenção da Serra only reported purchases in 2017, with percentages of 7.72%, 38.46%, and 63.69%, respectively. In 2018, it is particularly noteworthy that Cunha, Lagoinha, and Redenção da Serra did not appear in the national database, suggesting either a lack of activity or failure to report.

These findings may reflect either a failure to report data by the municipal administrators responsible for implementing the National School Feeding Program (PNAE) or a broader discontinuity in municipal engagement with public policies aimed at sourcing food from family farming. This context suggests institutional weaknesses in the consolidation of such initiatives across most municipalities. These weaknesses may be attributed to various factors, including a lack of inter-institutional coordination, operational challenges, or even political and administrative disinterest on the part of local governments.

Data from the 2017 Agricultural Census reveal that in the municipality of Lagoinha, 68.98% of family farmers are affiliated (Table 2) with cooperatives, professional organizations/unions, producer associations/movements, or neighborhood associations. In contrast, the other municipalities demonstrate significantly lower levels of farmer association. In a study of municipalities in the state of Santa Catarina [57], the authors point out that the solutions for the operationalization of deliveries depend on the characteristics of each municipality. In cases where farmers are more organized, the cooperatives provide an organizational structure for the logistics of food delivery. In the situations that involve individual farmers or smaller cooperatives, the solution adopted by municipal governments was to provide a center for receiving goods.

Table 2.

Association of producers responsible for family farming establishments by municipality.

The low percentage of food purchased from family farming in the municipality of Cunha (SP) is not justified by the absence of primary peasant agri-food production in the territory, but possibly by other factors that may limit its inclusion in this marketing channel. As hypotheses, one may consider the lack of knowledge of this local reality by those responsible for preparing the public calls, the low organization and association of farmers and the absence of documentation required for participation as suppliers in the PNAE, in addition to the lack of information and guidelines regarding the public call notices [23,58].

In the study by Valadares et al. [23], the authors identify several key success factors for municipalities engaged in the procurement of products from family farming. These include the coordination of local government bodies, particularly the Departments of Education and Agriculture, with representative entities of family farmers, as well as with technical assistance organizations such as Emater. The authors also highlight the importance of adapting legal instruments related to program implementation—such as public procurement notices—and ensuring that regulatory frameworks, including those related to sanitary inspection and certification, are aligned with the realities of local production.

Based on this analysis, it is evident that the territory demonstrates strong potential in both food production and processing, supported by the presence of active local associations and institutions. There is clear room to enhance this potential, particularly through inter-municipal cooperation, which could help to strengthen existing marketing channels and, most importantly, expand the procurement of food from family farming through programs such as the National School Feeding Program (PNAE).

Field Visits

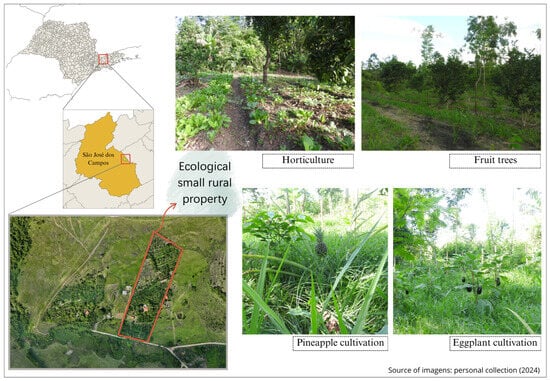

During the course of this research, two field experiences were conducted throughout 2024. The first took place at Silo’s headquarters in the municipality of Resende, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, with participation in the CaipiraTechLab course. The second was carried out at the Ecological small rural property, located in the Nova Esperança settlement, in the municipality of São José dos Campos, in the state of São Paulo. Although these interactions did not reveal the full diversity and scope of the peasant producers present in the study area, contributed to the understanding of some characteristics of this mode of production.

Participation in the CaipiraTechLAB Course enabled the exchange of experiences and ideas with producers. Based on these observations, it was possible to reflect on the characteristics that express the diversity among them. Three fundamental issues should be considered: (1) the way in which they became producers—whether through family tradition (parents and grandparents already engaged in farming) or by choosing this occupation at some point in life for a specific reason; (2) whether or not use processing technologies for their products; and (3) the forms of commercialization and transportation of their products. In general, based on the accounts of some producers, it was noted that there is a perception of the importance of their work, particularly in producing healthy food both for their own families and for consumers.

Although the municipality of São José dos Campos did not stand out as one of the main concentrations of potential areas for primary peasant agri-food production, it is possible to identify the presence of these areas in specific regions of the territory. The methodological and analytical approach adopted in this study seeks to reveal these spatialities. In this way, it becomes possible to highlight the characteristics of these territories, often invisible, and thus contribute to the recognition and valorization of the diversity of peasant production.

A representative example of a primary peasant production site is the Ecological small rural property, located in the Nova Esperança I Settlement, in a rural census sector near the municipal border of São José dos Campos and Caçapava. There, a family of farmers develops an Agroforestry System (AFS), characterized by a significant variety of fruits, roots and vegetables (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Example of primary peasant agri-food production in the municipality of São José dos Campos (SP), in the Nova Esperança I settlement.

The presence of producers belonging to agrarian reform projects, the development of agricultural practices related to the Atlantic Forest biome and the evidence of family labor associated with the reproduction of domestic units, demonstrated the relations with the secondary data used to identify potential areas of primary peasant agri-food production. The investigation of the landscapes and contexts identified from the data helped to understand how these elements are articulated in the configuration of these peasant territories.

By synthesizing the identified cases in relation to the SFSCs, it was observed that fairs do not constitute the main channel for these producers, despite being recognized in the literature as an important means of marketing production [59,60,61]. Door-to-door sales, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) initiatives and school meals provision were the main channels reported. In these channels, face-to-face interactions predominate, in which consumers purchase products directly from the producer [62]. Furthermore, definitions and conventions of product quality highlighted by the literature were verified in the reported cases, such as artisanal and in the rural properties production, as well as, as the adoption of sustainable practices, including organic agriculture and AFS.

Despite advances in Brazilian legislation that strengthened ties with family farming in 2009, its implementation still faces various difficulties and limitations, as already presented. A search for studies addressing the reality of the municipalities in the study area, regarding the acquisition of food from family farming through the PNAE program, did not identify specific references. Therefore, examples from other municipalities were used as a strategy for approximation and reflection, in addition to international studies related to school feeding programs and farmers’ associations.

In other countries around the world, pilot projects, experiences, and programs also link school feeding to local food production. In the case of China, for example, the study by Liu, Liu, and Bi [63] presents the benefits of so-called home-grown school feeding. However, they also point out its limitations, such as transportation restrictions related to the distance from the production site to the school. Depending on the distance to be traveled, farmers end up supplying the products monthly and, sometimes, due to the time and cost of transportation, prefer not to use this marketing channel with the school. It is noted that these limitations related to transportation logistics are also identified in the study carried out in municipalities in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil, as pointed out by Schwartzman et al. [64]. Nsamzinshuti et al. [65] state that logistics is one of the challenges for Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) to become a concrete alternative to the globalized food model.

Regarding farmer organizations, Bui et al. [66], in a study conducted with small farmers in Vietnam in 2020, state that cooperatives create opportunities for collaboration, starting new businesses, and obtaining support from local authorities or organizations. The study by Cruz and Assis [67] in municipalities in the southern coastal region of the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, shows that informal groups can be a way to stimulate organization and thus facilitate access to the PNAE (National School Feeding Program), in cases where farmers do not yet have formalized organizations. In the context of municipalities in the Metropolitan region of the state of São Paulo, Rocha, Pereira, and Baccarin [68] point to the need for opening spaces for dialog for greater interaction between family farmers, organizations, and public authorities to identify possibilities and limitations for meeting the demand for food for school meals.

It becomes fundamental to rethink the planning of food systems in order to promote a more integrated and participatory approach among the actors involved. Berkhout, Sovová, and Sonneveld [69], in investigating the resilience of food systems from the perspective of rural-urban relations, recommend, among other things for research and public policies, what is called network governance. Given the complexities of interactions in rural-urban food systems, there is a need for the participation of groups from different scales and sectors in joint decision-making, especially including actors who are usually excluded from governance mechanisms. In this context, horizontal relationships between technical planners and the target audience should result in bottom-up planning, necessarily involving popular sectors in collective decisions [70].

6. Conclusions

This study developed tools to support land use planning and management through mapping that describes the development of SIALs in the triple border region between the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Since territorial development plans a regional scale in Brazil seek to strengthen and expand the long-chain markets, highlighting alternative experiences to this mainstream model ensures that new strategies observing the possibilities for capital and social gains that can come with the short-chain markets that can be organized around the LAFs local/regional systems in the hope that in this way they become part of the development agenda.

The methodological contribution is the creation of a methodology capable of identifying potential areas for peasant primary agrifood production by selecting variables that enable or hinder the development of these practices over the regional space. Because the data are open and available nationwide, they can be replicated and rethought for other Brazilian municipalities that are part of other micro-regions. The cartographies produced aim to contribute as auxiliary instruments to land use planning and management, seeking to strengthen LAFSs at different scales of governance.

The land use and land cover classes used to identify potential areas, although less refined in resolution, were important in indicating their occurrence, which may be related to small-scale agriculture and extractive activities in the studied area. The use of rural property in conjunction with agricultural establishments data was important for confirming the occurrence of agricultural activities in these locations, which were also more prevalent on small rural properties. Although a low geographic coincidence was observed after the intersection of the data, a similar situation has been noted in other regions of Brazil [71], this procedure allowed for the characterization of the establishments.

For the analyzed area, the results indicate that there are possibilities for the establishment of LAFSs as a local development strategy associated with social inclusion and environmental responsibility. However, for this, there is a need to reorganize the transportation logistics systems and strengthen the institutional framework and the marketing channels for products that have their origins based on small properties managed by peasants’s production modes to effectively establish these already existent short agrifood chains.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010083/s1, Table S1: Classification of rural propertis by size; Table S2: Classification rules for potential primary peasant agri-food production areas.

Author Contributions

Complete preparation of the manuscript (Conceptualization, methodology, results and discussion) B.D.d.S., T.M.A. and A.M.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), process number 2023/18219-0.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AEs | Agricultural Establishments |

| AAFNs | Alternative Agri-food Networks |

| AFS | Agroforestry System |

| APLIs | Arrangements and Systems |

| CAR | Rural Environmental Registry |

| CNEFE | National Address Registry for Statistical Purposes |

| CSA | Community Supported Agriculture |

| CUs | Conservation Units |

| UFPA | Federal University of Pará |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| INCRA | National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform |

| INPE | National Institute for Space Research |

| LAFSs | Local Agri-food Systems |

| MMA | Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change |

| PAA | Food Acquisition Program |

| PNAE | National School Feeding Program |

| SFSCs | Short Food Supply Chains |

Notes

| 1 | Silo—Art and Rural Latitude is a Civil Society Organization (CSO) established in 2017 and located in the Environmental Protection Area of Serrinha do Alambari, in the Serra da Mantiqueira, at the triple-border region between the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. |

| 2 | The estimator operates by counting all points located within a defined influence radius, taking into account the weighting of each point based on its distance from the location of interest [47,48]. |

| 3 | <https://www.akarui.org.br/a-akarui> (accessed on 5 November 2025). |

| 4 | <https://institutoaua.org.br/> (accessed on 5 November 2025). |

| 5 | <https://www.serracima.org.br/> (accessed 5 on November 2025). |

References

- Onu-Habitat. Diretrizes Internacionais para Planejamento Urbano e Territorial, 1st ed.; Onu-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/diretrizes-internacionais-para-planejamento-urbano-e-territorial (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Monte-Mór, R.L. Urbanização Extensiva e Lógicas de Povoamento: Um Olhar Ambiental. In Território, Globalização e Fragmentação, 1st ed.; Santos, M., Souza, M.A., Silveira, M.L., Eds.; Hucitec/Anpur: São Paulo, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Baláza, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of their Socio-Economic Characteristics, 1st ed.; Joint Research Centre: Sevilla, Spain, 2013; p. 128. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC80420 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Aguiar, L.C.; Delgrossi, M.E.; Thomé, K.M. Short food supply chain: Characteristics of a family farm. Cienc. Rural 2018, 48, e20170775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazolla, M.; Schneider, S. Cadeias Curtas e Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas. In Cadeias Curtas e Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas: Negócios e Mercados da Agricultura Familiar, 1st ed.; Gazolla, M., Schneider, S., Eds.; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017; pp. 9–24. Available online: https://www.lume.ufrgs.br/bitstream/handle/10183/232245/001020657.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. Sete Teses Sobre a Agricultura Camponesa. In Agricultura Familiar Camponesa na Construção do Futuro; Peterson, P., Ed.; AS-PTA Agricultura Familiar e Agroecologia: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; pp. 17–31. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283451041_Sete_teses_sobre_a_agricultura_camponesa (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Acosta, M.D.H.; Colino, E.V.; Savarese, M. De Pandemias y seguridad alimentaria: Mapeo de circuitos cortos de abastecimiento en Río Negro-Datos relevados. Otra Econ. 2022, 15, 166–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, R.G.; Gracia, A. Construyendo resiliencia alimentaria local: Experiencias de circuitos cortos en el centro y sureste de México. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2021, 18, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. O Retorno do Território. In Território: Globalização e Fragmentação, 4th ed.; Santos, M., Souza, M.A.A., Silveira, M.L., Eds.; Hucitec: São Paulo, Brazil, 1994; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fernàndez, M.C.L. Territorios, Ciudades y Sistemas Alimentarios: Una Visión Estratégica. Estudio de Caso: México. In Sistemas Alimentarios en América Latina y el Caribe-Desafíos en un Escenario Pospandemia; Silva, J.G., Jales, M., Rapallo, R., Días-Bonilla, E., Girardi, G., Del Grossi, M., Luiselli, C., Sotomayor, O., Rodríguez, A., Rodrigues, M., et al., Eds.; FAO y CIDES: Panamá City, Panamá, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Z.; Schumilas, T.; Scott, S. Um Retrato das Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas na China. In Cadeias Curtas e Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas: Negócios e Mercados da Agricultura Familiar; Gazolla, M., Schneider, S., Eds.; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017; pp. 473–490. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Inovações Econômicas em Cadeias Curtas de Abastecimento Alimentar. In Cadeias Curtas e Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas: Negócios e Mercados da Agricultura Familiar; Gazolla, M., Schneider, S., Eds.; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Folhes, R.T.; Fernandes, D.A. A dominância do paradigma tecnológico mecânico-químico-genético nas políticas para o desenvolvimento da bioeconomia na Amazônia (Paper 540). Pap. NAEA 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; YE, J.; Schneider, S. Reading markets politically: On the transformativity and relevance of peasant markets. J. Peasant. Stud. 2022, 50, 1852–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Histórico da Rede Ecovida. 2025. Available online: https://ecovida.org.br/info/sobre/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ribeiro, A.E.M.; Galizoni, F.M.; Lima, V.M.P.; Cruz, M.S.; Araújo, A.M.; Rocha, C.V. Investigação e Extensão Universitária em Feiras Livres—Experiências no Vale do rio Jequitinhonha, Brasil. In Redes y Circuitos Cortos de Comercialización Agroalimentarios, 1st ed.; Camacho, Y.A., Molina, J.P., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, F.A. Arranjos e Sistemas Produtivos e Inovativos Locais—As possibilidades do Conceito na Constituição de um Sistema de Planejamento para a Amazônia. Rev. Bras. Inov. 2006, 5, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durr, J.; Costa, F.D.A. Cadeias produtivas de base agrária e desenvolvimento regional: O caso da região do Baixo Tocantins. Amazon. Cienc. Desenvolv. 2008, 3, 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, D.G.; Costa, F.D.A.; Brienza Júnior, S.; Mello, D.G. Mercado e potencialidades dos produtos oriundos de floresta secundária em áreas de produção familiar. Novos Cad. NAEA 2009, 12, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Costa, F.A. Economia camponesa referida ao bioma da Amazônia: Atores, territórios e atributos. Pap. NAEA 2020, 29, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silo Programas. CaipiraTechLab. Available online: https://silo.org.br/caipiratechlab/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Turpin, M.E. A alimentação escolar como fator de desenvolvimento local por meio do apoio aos agricultores familiares. Segur. Aliment. Nutr. 2009, 16, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadares, A.A.; Alves, F.; Bastian, L.; Silva, S.P. Da Regra aos Fatos: Condicionantes da Aquisição de Produtos da Agricultura Familiar para a Alimentação Escolar em Municípios Brasileiros; Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea): Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dados da Agricultura Familiar. Available online: https://www.gov.br/fnde/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/programas/pnae/consultas/pnae-dados-da-agricultura-familiar (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Tobler, W.R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit Region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censo Agropecuário de 2017: Resultados Definitivos. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2017/resultados-definitivos (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Dean, W. A Ferro e Fogo: A História e a Devastação da Mata Atlântica Brasileira; Companhia das Letras: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996; p. 484. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, D.C. O ‘Bosque de Madeiras’ e Outras Histórias: A Mata Atlântica no Brasil Colonial (Séculos XVIII e XIX). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, D.A.P.; Ribas, R.P. Caderno Regional do Estado do Rio de Janeiro: Região do Médio Paraíba; Imprensa Oficial: Niterói, Brazil, 2017; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- Serviço Florestal Brasileiro (SFB). Cadastro Ambiental Rural (CAR). Available online: https://consultapublica.car.gov.br/publico/imoveis/index (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Cadastro Nacional de Endereços para Fins Estatísticos (CNEFE). Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/38734-cadastro-nacional-de-enderecos-para-fins-estatisticos.html?=&t=downloads (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA). Projetos de Reforma Agrária. Available online: https://www.gov.br/incra/pt-br/assuntos/reforma-agraria (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ministério do meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima (MMA). Cadastro Nacional de Unidades de Conservação (CNUC). Available online: https://cnuc.mma.gov.br/map (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Mapbiomas. Coleções. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/colecoes-mapbiomas/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Sos Mata Atlântica. Atlas Dos Remanescentes Florestais. Available online: http://mapas.sosma.org.br/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Brasil. Law 8.629. 1993. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L8629.htm (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- INCRA—National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform. Módulo fiscal. Available online: https://www.gov.br/incra/pt-br/assuntos/governanca-fundiaria/modulo-fiscal (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. Camponeses e a Arte da Agricultura: Um Manifesto Chayanoviano, 1st ed.; Editora Unesp: São Paulo, Brazil; Editora UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2016; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Wanderley, M.N.B. Raízes históricas do campesinato brasileiro. Agric. Fam. Real. Perspect. 1996, 3, 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M.R. Cartografias da Agricultura Urbana: Contribuições ao Planejamento Territorial na Região Metropolitana do Vale do Paraíba e Litoral Norte. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, H.M.; Costa, F.A. Agricultura Camponesa. In Dicionário da Educação do Campo; Caldart, R.S., Pereira, I.B., Alentejano, P., Frigotto, G., Eds.; Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Expressão Popular: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012; pp. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, V.M.; Carvalho, J.G. Campesinato e neoextrativismo em São Paulo: Dinâmicas e conflitos da atividade sucroenergética na região de Ribeirão Preto. Rev. Bras. Estud. Urbanos Reg. 2024, 26, e202418pt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.R.; Escada, M.I.S.; Marujo, R.F.B.; Monteiro, A.M.V. Cartografia do invisível: Revelando a agricultura de pequena escala com imagens Rapideye na região do baixo Tocantins. Rev. Dep. Geogr. 2019, 38, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descrição da Legenda. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/codigos-de-legenda/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Brasil. Law 9.985. 2000. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9985.htm (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Amaral, S.; Gavlak, A.; Escada, M.I.S.; Monteiro, A.M.V. Using remote sensing and census tract data to improve representation of population spatial distribution: Case studies in the Brazilian Amazon. Popul. Environ. 2012, 34, 142–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.C.; Gatrell, A.C. Interactive Spatial Data Analysis; Longman Scientific & Technical: Essex, UK, 1995; p. 413. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.S.; Câmara, G. Análise Espacial de Eventos Pontuais. In Análise Espacial de Dados Geográficos; Druck, S., Carvalho, M.S., Câmara, G., Monteiro, A.V.M., Eds.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anazawa, T.M. Vulnerabilidade e Território no Litoral Norte de São Paulo: Indicadores, Perfis de Ativos e Trajetórias. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anazawa, T.M. A Grave Escassez Hídrica e as Dimensões de um Desastre Socialmente Construído: A Região Metropolitana de Campinas Entre 2013–2015. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Devide, A.C.P.; Castro, C.M.; Ribeiro, R.L.D.; Abboud, A.C.S.; Pereira, M.G.P.; Rumjanek, N.G. História Ambiental do Vale do Paraíba Paulista, Brasil. Rev. Biocienc. 2014, 20, 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Comitê Executivo de Estudos Integrados da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paraíba do Sul (CEEIVAP). Plano de Recursos Hídricos da Bacia do Rio Paraíba do Sul: Resumo: Análise dos Impactos e das Medidas Mitigadoras que Envolvem a Construção e Operação de Usinas Hidrelétricas: Relatório; Comitê Executivo de Estudos Integrados da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paraíba do Sul (CEEIVAP): São Paulo, Brazil, 2007; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Comitê Executivo de Estudos Integrados da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paraíba do Sul (CEEIVAP). Relatório Técnico Sobre a Situação dos Reservatórios com Subsídios para Ações de Melhoria da Gestão na Bacia do Rio Paraíba do Sul; Comitê Executivo de Estudos Integrados da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paraíba do Sul (CEEIVAP): São Paulo, Brazil, 2010; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Galvanese, C.; Puga, B.P.; Grigoletto, F. Desafios à exploração sustentável da sociobiodiversidade como vetor de desenvolvimento de territórios rurais no Brasil. Raízes Rev. Cienc. Sociais Econ. 2024, 43, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.F.M.; Vazquez, G.H. Programa de inclusão da polpa do fruto da palmeira juçara na merenda escolar de Caraguatatuba/SP. Rev. Nac. Gerenciamento Cid. 2019, 7, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rede de Agroecologia do Vale do Paraíba (Akarui, Tekoporã, São Luiz do Paraitinga, São Paulo, Brazil). Personal communication, 2024.

- Elias, L.D.P.; Belik, W.; Cunha, M.P.D.; Guilhoto, J.J.M. Impactos socioeconômicos do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar na agricultura familiar de Santa Catarina. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 57, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.E.M.; Retière, M.I.H.; Almeida, N.; Dos Santos, C.F. A participação da agricultura familiar no Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar: Estudo de casos em municípios paulistas da região administrativa de Campinas. Segur. Aliment. Nutr. 2017, 24, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.S.; Zanini, M.C.C. Algumas Considerações Sobre a Família Camponesa: Desafios e Estratégias na Reprodução Social do Campesinato no Feirão Colonial de Santa Maria/RS. In Mercados, Campesinato e Cidades: Abordagens Possíveis; Zanini, M.C.C., Ed.; Oikos: São Leopoldo, Brazil, 2015; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cassol, A.; Schneider, S. Construindo a Confiança nas Cadeias Curtas: Interações Sociais, VALORES e qualidade na Feira do Pequeno Produtor de Passo Fundo/RS. In Cadeias Curtas e Redes Agroalimentares Alternativas: Negócios e Mercados da Agricultura Familiar; Gazolla, M., Schneider, S., Eds.; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017; pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.S.; Ribeiro, E.M.; Perondi, M.A.; Oliveira, D.C.; Costa, H.M. Agricultura familiar, feiras livres e feirantes no Alto Jequitinhonha. Rev. Campo Territ. 2020, 15, 90–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Jieying, B. Shortening food supply chain in home-grown school feeding: Experiences and lessons from south central China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. 2023, 26, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, F. Antecedentes e elementos da vinculação do programa de alimentação escolar do Brasil com a agricultura familiar. Cad. Saúde Publica 2017, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamzinshuti, A.; Janjevic, M.; Rigo, N.; Ndiaye, A.B. Logistics collaboration solutions to improve short food supply chain solution performance. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Supply Chain Management, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 17–19 May 2017; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.N.; Nguyen, A.H.; Le, T.T.H.; Nguyen, V.P.; Le, T.T.H.; Tran, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.M.; Le, T.K.O.; Nguyen, T.K.O.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; et al. Can a short food supply chain create sustainable benefits for small farmers in developing countries? An exploratory study of Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.F.; Assis, T.R.P. Contribuições de três organizações para a comercialização da agricultura familiar no PNAE, no território sul litorâneo do Espírito Santo. Interações 2019, 20, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; Pereira, E.L.; Baccarin, J.G. Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar e agricultores familiares contemplados: O caso da região metropolitana de São Paulo. Retratos Assentamentos 2024, 27, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, E.; Sovová, L.; Sonneveld, A. The role of urban–rural connections in building food system resilience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte-Mór, R.L.M. Urbanização Extensiva e Economia dos Setores Populares. In O Brasil, a América Latina e o Mundo: Espacialidades Contemporâneas; Oliveira, M.P., Coelho, M.C.N., Corrêa, A.M., Eds.; Lamparina: São Paulo, Brazil; Federação de Powerlifting do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FEPERJ): Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Geografia (Anpege): São Paulo, Brazil, 2008; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, E.E.D.; Carvalho, C.A.D.; Martinho, P.R.R. O Mundo Rural do Censo Agropecuário não é o do Cadastro Ambiental rural? In Uma Jornada Pelos Contrastes do Brasil: Cem anos do Censo Agropecuário; Vieira Filho, J.E.R., Gasques, J.G., Eds.; Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA): Brasília, Brazil, 2020; pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.