Abstract

Urban and population densification have resulted in deteriorating living conditions for populations and the loss of UGSs. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the social, economic and environmental vulnerabilities of our societies, but it has also demonstrated the importance of UGSs as intrinsic elements for maintaining the quality of life of the population and making urban spaces sustainable. Due to its considerable area of UGS, the district of Benfica in Lisbon, Portugal, is the object of study. The study focuses on understanding how the proximity of UGS influences the practice of leisure activities for different publics, and how they are reflected in the populations’ lives, exploring the context during the COVID-19 pandemic. It develops a methodology with a mixed-methods approach: (1) literature review, policies, and urban planning; (2) observation methods, mapping and spatial analysis of UGS types; and (3) surveys. The empirical results indicate the importance of proximity to improve the frequency, namely for the elderly and children. The results also demonstrate that the quality (infrastructure and equipment) of UGS, despite having less walking proximity, is an important element to attract people to use the UGS. A general conclusion is that the proximity and accessibility (walking or public transport) are interlinked in both profiles of UGS, demonstrating a relationship between the place of residence, easy access and frequency of UGS in the practice of activities and the self-assessed physical and mental health benefits.

1. Introduction

A city is the consequence of a complex combination of features, serving as the backdrop for the daily lives of its inhabitants [1]. The swift expansion of urban areas coupled with the escalating population density, often attributed to industrialisation, has precipitated a decline in the living standards of urban populations [2,3,4]. This phenomenon is closely intertwined with poverty, socio-economic disparities, and the degradation of environmental integrity due to excessive resource exploitation, water and air contamination, waste accumulation, and a reduction in green spaces [5,6,7]. Consequently, these factors have engendered health disparities within local communities, leading to a surge in both non-communicable and communicable diseases, as exemplified by the global health crisis of COVID-19 [8,9].

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected vulnerable populations, such as older people and children, impacting their health, well-being, and education [7]. During this period, urban well-being became inextricably linked to what may be seen as a “new lifestyle”, characterised by quarantine measures and a shift towards remote work and education at home [5]. The lockdowns precipitated substantial alterations in individual behaviours and routines [10], amplifying the significance of domestic environments and proximity to green spaces [11].

This increased awareness of the critical role of nearby green public spaces, which emerged as intrinsic elements akin to a “space vaccine”, conferring physical and psychological benefits and enhancing urban well-being and sustainability [4,12]. Studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a propensity among individuals to frequent nearby green spaces, underscoring their importance.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the COVID-19 global health emergency on 5 May 2023 [13], the enduring threat underlines the urgency for policymakers of adopting transformative measures to mitigate the spread of infectious diseases, especially in urban green spaces (UGSs). Insights into the quality, demand dynamics, and utilisation trends of UGSs, both before and during the crisis, are indispensable for devising strategies to enhance the spatial and social functionality, foster social inclusion, and promote physical and mental health, thereby cultivating healthier, more inclusive, and integrated urban environments [14]. In the European Union member states, socio-economic and demographic nuances are reviewed in order to moderate the health and green space relationship [15] and to ensure equitable access to high-quality urban environments, including green and leisure spaces, irrespective of residential location.

Hence, the first research question is related to the assumption that green spaces contribute to the liveability of populations. In this paper, we understand “liveability” as the capacity of urban environments to support healthy, safe, inclusive and environmentally sustainable everyday life, combining physical, social and economic dimensions [15,16]. This aligns with international frameworks such as the New Leipzig Charter and the WHO Healthy Cities approach, which emphasise access to high-quality public and green spaces as core components of liveable cities [16,17]. A complementary research question is based in the assumption that the proximity of green spaces is more relevant than the quality (in terms of infrastructure and amenities) of these spaces, improving their use. The empirical verification contributes to a better understanding of, and further recommendations for, how these spaces can foster healthier and more inclusive urban environments.

While a growing body of literature has analysed the relationship between COVID-19, urban green spaces and well-being—often using large-scale datasets, mobility data or single-method approaches—there is still limited evidence from neighbourhood-scale, applied studies that integrate the spatial structure, proximity, perceived quality and everyday patterns of use in a consolidated urban context. This paper addresses this gap by providing an empirical case study from a Southern European neighbourhood, combining spatial analysis, field observation and user perceptions. By focusing on Benfica, a district characterised by a diverse green structure and a pronounced ageing profile, the study contributes planning-oriented insights into how proximity and quality jointly support liveability and well-being during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article comprises six parts, with the first being the introduction, followed by a literature review focusing on green spaces and their relationship with a healthy environment and COVID-19. Section 3 addresses urban green spaces in Lisbon. Section 4 details the study area and methods, while Section 5 presents and discusses the results based on observations and surveys conducted in Benfica’s green spaces. Section 6 presents the conclusions and recommendations.

2. Green Spaces as Health Promoters

Urbanisation and increasing population density exacerbate the challenge of access to recreational areas, contributing to physical inactivity, which is responsible for approximately 3.2 million deaths annually worldwide [17]. The availability and quality of UGSs correlate with variations in both physical and mental outcomes. Research indicates that increased access to nearby green areas significantly mitigates the mortality risk and the prevalence of chronic diseases such as stroke, asthma, diabetes, obesity, and coronary heart disease [18,19]. Moreover, exposure to green spaces, whether physical or visual (including mere contemplation through a window), is associated with improved mental health, including reduced anxiety, depression, and stress, along with enhanced cognitive functioning, attention, creativity, mood, and overall psychological well-being [18,19,20].

Notably, children, particularly females, benefit from the utilisation of nearby green spaces, exhibiting better concentration, discipline, and functional performance in daily activities. The positive effects of physical activity extend beyond the physical–functional domains, encompassing mental and social dimensions, thereby bolstering individual resilience against physiological and psychological stressors. Conversely, the absence of contact with natural spaces heightens the risk of mental disorders [21].

Children and older adults particularly benefit from regular use of nearby UGSs, showing better functional performance and resilience to stressors, whereas lack of contact with nature has been associated with an increased risk of mental disorders [21].

Theoretical Framework: Restorative Theories and Well-Being

The conceptual foundation of this research builds on two complementary models that explain the restorative potential of contact with nature: the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) by Kaplan and Kaplan (1995) [22] and the Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) by Ulrich (1983) [23]. Both describe how natural environments help restore depleted cognitive and emotional resources, thereby contributing to mental well-being [24].

According to the ART, daily exposure to stressors such as traffic, crowding, or noise leads to attentional fatigue, which can be alleviated by experiences of “soft fascination” in nature that effortlessly capture attention and allow mental recovery [18]. Brief exposure—sometimes under ten minutes—has been shown to improve concentration and reduce mental fatigue [25].

In this study, these theories provide the interpretive basis for understanding users’ perceptions of well-being and health improvement. The reported benefits—especially stress reduction, mood improvement, and cognitive relaxation—observed among survey respondents confirm that proximity to green spaces fosters restoration processes consistent with the ART and SRT assumptions.

The SRT, on the other hand, focuses on emotional and physiological responses [22], showing that visual and sensory contact with vegetation, water, and natural light can reduce stress indicators and promote positive affect. Ulrich does not specifically detail the spatial configurations of a restorative environment but reinforces the increasing importance of exposure to natural environments—given the innate human inclination towards such [26]—given the impacts of disruptive events and adversity imposed by daily life on modern humans [27]. Recent studies have expanded these theoretical perspectives, confirming that biodiversity, multisensory experiences, and micro-scale green areas can significantly enhance mental restoration and stress recovery in urban contexts [28].

Beyond these general mechanisms, evidence suggests that the degree of naturalness and management of urban green spaces (UGSs) shapes their restorative value. More “natural” spaces tend to foster attentional restoration and stress recovery, whereas more “managed” parks enhance the perceived safety, routine use, and social interaction—both supporting well-being through complementary pathways.

The efficacy of UGSs in promoting health depends on the exposure frequency, duration, and intensity, which are contingent on UGS availability and disposition [29]. Exposure can be measured in three ways: frequency (i.e., how often one visits an UGS), duration (i.e., how long a visit to an UGS lasts), and intensity (i.e., what activity can be performed during a visit). The provision of UGSs can also be measured in three ways: quantity (i.e., how many UGSs exist in each geographical area), quality (i.e., how qualitatively attractive an UGS is), and accessibility (i.e., access to the UGS, free or paid, and geographically close or far from where people live) [30].

Beyond the quantity and accessibility, several authors have operationalised UGS quality through attributes such as the safety, cleanliness, maintenance, aesthetics, comfort, lighting, and availability of facilities. These perceived quality dimensions strongly influence both the frequency of visits and the magnitude of physical and mental health benefits associated with UGS use, particularly for stress reduction, social interaction, and perceived safety among vulnerable groups. These indicators are widely used in international UGS quality frameworks and public health assessments [19,31,32]. In this study, these dimensions provide the conceptual basis for the empirical evaluation of Benfica’s UGSs.

3. The Concept of Urban Green Space and Its Association with the Portuguese Context

The concept of UGS has presented changes throughout history, essentially associated with the evolution of the city. These spaces are then located within the urban boundary and are defined as open spaces of public or private domain, covered by permeable surfaces, soil [31,33] or referring to all forms of vegetation. These spaces play a crucial role in shaping liveable cities, denoting environments that are safe, clean, aesthetically pleasing, economically vibrant, accessible to diverse populations, efficiently managed, and imbued with a sense of community. UGSs encompass a diverse array of areas, including formal parks, green roofs, woodlands, community gardens, lawns, sports fields, shrubbery, and ornamental plant arrangements. Additionally, they can encompass more informal and seemingly neglected areas such as vacant lots, spaces along highways and railways, pavements, and abandoned properties [14,31,34].

UGSs assume varied characteristics and dimensions, as well as a variety of uses and functions. A set of dimensions can characterise them: localisation, size, function, quality and safety, distance from users and intended publics, besides being related to the landscape quality and user perception [18]. Green land uses in urban areas have been studied extensively for their contributions to urban quality of life [35], as part of the urban green infrastructure [31].

The green structure of urban areas comprises main and secondary substructures. The main structure comprises spaces with varying densities of vegetation, offering a multitude of services and amenities to attract users from different social and age groups. This structure includes a diverse range of typologies, such as gardens, parks, sports areas, urban gardens, and specialised enclosures like zoos and exhibition parks. Conversely, the secondary green structure consists of public spaces adjacent to residential, service, and economic areas, forming smaller, neighbourhood-oriented spaces (called proximity or neighbourhood UGSs) catering to the local population within a walking distance of up to 400 m [36].

In Lisbon, the Municipal Master Plan of 2020 delineates the Municipal Ecological Structure, which includes the Fundamental Ecological Structure at the metropolitan level and the Integrated Ecological Structure at the municipal level. The former includes corridors and wetland systems, while the latter features green spaces. These spaces are categorised as follows:

- Recreation and production: Permeable areas designated for urban agriculture and recreational activities, including collective amenities and infrastructure for leisure and tourism.

- Protection and conservation: Areas dedicated to conserving ecosystems, habitats, and valuable vegetation, with restrictions on construction except for recreational support and fire-control infrastructure.

- Road infrastructure frames: Spaces under different levels of restriction that only allow support facilities.

- Riverside spaces: Areas providing ecological balance and recreational opportunities, ensuring pedestrian access to riverbanks and landscape enjoyment.

In Lisbon, UGSs such as parks and gardens are recognised in the city’s Municipal Master Plan (PDM/Plano Diretor Municipal) [37] as essential for improving the quality of life of residents and supporting environmental sustainability. These spaces contribute to urban resilience by improving air quality, promoting biodiversity, and providing areas for recreation. Ensuring equitable access to these areas is a priority outlined in the PDM, reflecting Lisbon’s commitment to creating a more sustainable and liveable urban environment.

Furthermore, Lisbon’s Plano Verde (Green Plan, 2020) [38] and the Urban Biodiversity Strategy reinforce the PDM’s objectives by establishing a continuous ecological network that integrates the main and secondary green structures. These instruments promote connectivity between parks, gardens, and neighbourhood green corridors, following the principles of the Healthy Cities initiative and the European Green Capital 2020 programme. In Benfica, this policy framework guides the requalification of local parks such as Silva Porto and Quinta da Granja, ensuring equitable access to safe, inclusive, and multifunctional spaces. By embedding ecological and social functions into spatial planning, Lisbon aims to enhance the physical and mental well-being of residents and contribute to climate resilience at the neighbourhood scale. Lisbon’s green planning strategy aligns with transdisciplinary approaches that integrate ecological, social, and health dimensions of urban infrastructure [39]. In recent years, several municipal and community-led initiatives have contributed to the diversification and improvement of Lisbon’s green infrastructure. Examples include Agrofloresta de Campolide—Bela Flor Respira, which transformed a degraded hillside into an agroforestry park through community participation, and Vale do Casal Vistoso Urban Forest, a reforestation project that promoted biodiversity and climate resilience. In addition, the Green Corridor of Monsanto has been extended to improve the pedestrian and ecological connections across the city. These initiatives illustrate Lisbon’s ongoing commitment to expanding and regenerating its green spaces in response to the climate crisis [38,40,41].

4. Study Area and Methodology

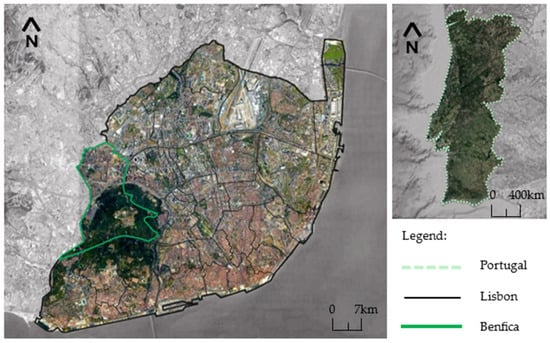

This study focuses on Benfica, a district in the municipality of Lisbon, and examines the impact of its UGSs on residents’ quality of life. Covering 8.02 km2, Benfica constitutes 9.5% of Lisbon’s total area and is part of the city’s Northwest Zone (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic framing of the study area. Location of the municipality of Lisbon with all the districts. Benfica is highlighted in dark grey. Source: [5].

Originally a rural village connected by a suburban railway, Benfica has evolved into a densely populated district with significant socio-spatial diversity, community engagement, and potential for urban centrality.

Aligned with European and Portuguese demographics, Benfica has experienced a population decline over the past decade. In 2021, Benfica had a population density of 4409.2 inhabitants/km2, compared to 5455.2 inhabitants/km2 in Lisbon. Between 2011 and 2021, Benfica’s population decreased by about 4%, accompanied by clear signs of ageing. The share of residents aged 75 and older rose from 13.6% to 17.2%, while the working-age group slightly declined. Women remain the majority (55.3%), particularly among the older age groups. These demographic shifts underline the growing importance of accessible and inclusive urban green spaces for elderly residents (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characterisation of Portugal, Lisbon, and Benfica. Source: [42,43].

Table 2.

Population living in Benfica by age group and gender. Source: [44,45].

This demographic shift has been accompanied by a significant increase in the ageing population, with the elderly dependency ratio reaching 48.2 (Table 1).

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative techniques to assess the UGSs in Benfica. The methodology included the following:

- Cartographic observation: Mapping of UGSs using geographic information systems (GISs) to identify the spatial distribution and typologies.

- Quantitative surveys: Structured surveys were conducted with UGS users to collect data on demographics, usage patterns, and health impacts. The survey included 80% closed questions on the frequency of use, reasons for visiting, and perceived health benefits. A total of 120 surveys were conducted from August to September 2021, via on-site intercept sampling with voluntary participation, across different locations, days, and time periods. Approximately 20 surveys were conducted in each of the six analysed urban green spaces, ensuring balanced representation across different locations within Benfica.

- The questionnaire comprised 25 questions divided into three thematic blocks: (1) users’ socio-demographic profile; (2) patterns of use—frequency, duration, activities, and travel modes; and (3) self-perceived health and well-being before, during, and after the COVID-19 restrictions. Although the questionnaire did not ask for the exact home-to-UGS distance, proximity was indirectly captured through respondents’ reported mode of access (predominantly walking) and travel time to each park. These indicators are commonly used as proxies for walkable proximity in urban green space studies. A five-point Likert scale was applied to evaluate the perceived quality attributes, such as cleanliness, safety, maintenance, comfort, lighting, and diversity of facilities. These quality indicators were not defined arbitrarily; rather, they were adapted from established frameworks in the literature that identify the perceived safety, cleanliness, maintenance, comfort, lighting, and availability of facilities as core determinants of UGS quality and restorativeness. These parameters have been shown to influence usage patterns, perceived well-being, and the likelihood of experiencing restorative benefits in urban green environments [18,19,31]. Accordingly, our survey grid translated these theoretically grounded quality dimensions into an operational tool adapted to the Benfica context. Surveys were conducted in six UGSs across Benfica on weekdays and the weekends between them, covering different times of the day. Although the sampling strategy was designed as simple random sampling, participation relied on voluntary availability, which is consistent with an on-site intercept sampling approach commonly used in neighbourhood-scale exploratory studies. Although participation was voluntary, on-site observation revealed that most respondents were habitual users of the selected UGSs, regularly visiting these spaces before, during and after the COVID-19 restrictions. This constraint limits the application of inferential statistical tests; however, the approach remains methodologically robust and appropriate for an exploratory, neighbourhood-scale case study focused on usage patterns and user perceptions rather than statistical generalisation. This reduces the likelihood that the survey captured only occasional or COVID-19-specific visitors. Nevertheless, the diversity of sites and schedules ensured representativeness across age and gender groups, enabling reliable characterisation of the usage patterns. Similar post-lockdown studies have confirmed that the frequency of visits to nearby green areas is closely related to psychological recovery and life satisfaction across user groups [46,47].

- Qualitative observations: On-site observations of UGSs were conducted to evaluate the accessibility, infrastructure, and variety of activities offered. This involved examining both internal and external access, maintenance quality, and user interactions. The qualitative observations were based on a grid that traduced these aspects, as translated into Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3. Summary of the urban green structure in Benfica. Source: [5,36].

Table 3. Summary of the urban green structure in Benfica. Source: [5,36]. Table 4. Accessibility and mobility parameters of the analysed UGSs in Benfica, based on field observation and user surveys. Source: [5].

Table 4. Accessibility and mobility parameters of the analysed UGSs in Benfica, based on field observation and user surveys. Source: [5].

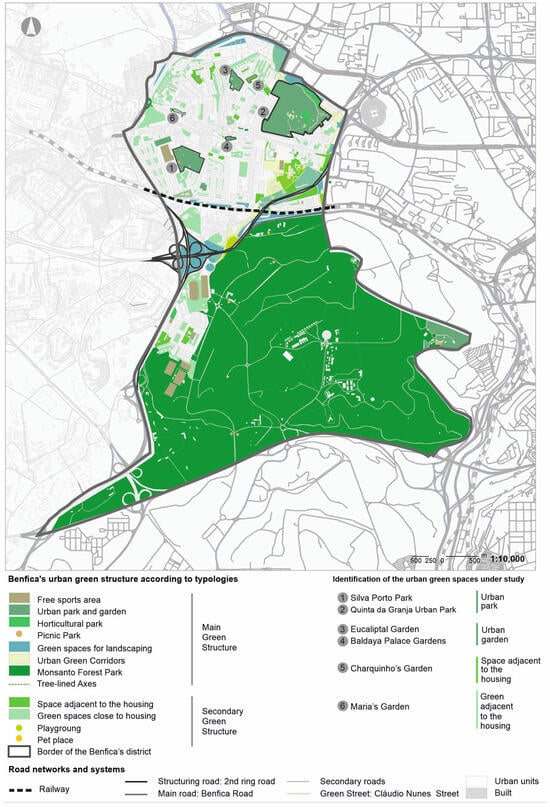

While Benfica includes a significant portion of the Monsanto Forest Park, the primary focus of this study was on urban parks such as Silva Porto Park, Quinta da Granja Urban Park, Baldaya Palace Gardens, Maria’s Garden, Eucaliptal Garden, and Charquinho’s Garden (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of the analysed urban green spaces (UGSs) in Benfica: Silva Porto Park, Quinta da Granja Urban Park, and Baldaya Palace Garden. Source: [5].

This district represents a particularly unique area within Lisbon’s green infrastructure, as part of its territory is occupied by the extensive Monsanto Forest Park—the largest green area in the city—which establishes physical and ecological continuity with the neighbouring parish of São Domingos de Benfica and the adjacent municipality of Amadora. This connection functions as a metropolitan green corridor, linking Benfica’s local urban parks to the wider ecological and recreational network of Lisbon. These inter-district linkages enhance accessibility to green spaces and reinforce Benfica’s strategic role in the city’s green structure.

5. Results and Discussion

Benfica stands out from most of the residential neighbourhoods in Lisbon in terms of the value, number, and diversity of UGSs, including historical areas such as Quinta da Granja, smaller public spaces, and heritage sites like the Baldaya Palace Garden and Monsanto Forest Park. The latter, the largest UGS, covers approximately 1000 ha citywide and 400 ha within Benfica. Cartographic observation reveals that Benfica’s existing green space structure comprises comprises a diverse set of urban green space typologies, classified into main and secondary green structures and detailed according to specific functional categories, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3.

Figure 3.

Typology of Benfica’s UGSs and identification of the UGSs under study. Source: [5].

The analysis of Benfica’s UGSs included (i) spatial identification and classification of green spaces by typology and green structure (Figure 3) and (ii) assessment of the minimum green area requirements per inhabitant (Table 3).

The cartographic analysis reveals that Benfica’s green space structure covers approximately 4.5 km2, representing 56% of the urban surface. The per capita green area is 127.55 m2, reinforcing the effectiveness of UGSs in providing public health benefits. Most of this area is attributed to Monsanto Forest Park. Comparative analysis with other studies shows that Benfica’s UGSs provide a high per capita green area relative to other European urban areas. However, the distribution of UGSs shows discrepancies between the northern and southern parts of the district, indicating the need for equitable urban planning to maximise access to UGSs.

Table 3 provides a detailed description of the different UGS types in the study area, based on a grid.

Benfica features a diverse network of urban green corridors, including tree-lined pavements and central separators that connect the urban fabric. Gardens and smaller landscaped spaces enhance the green continuum principle, whilst parks, being large, continuous green spaces, support urban landscapes and improve the quality of public space. Comparable patterns were identified in international studies, where pocket parks, greenways and multifunctional spaces played complementary roles in enhancing well-being during and after the COVID-19 pandemic [48,49].

The application of the chosen methodology matches the research purpose, as Benfica’s green structure was analysed in order to understand the interaction between individuals and green public spaces. The parameters examined include “accessibility and mobility” and the “activities available” at each site.

Public spaces in Portugal are freely open to community use, as are UGSs (Table 4). In Benfica, they can be accessed by various modes (walking, soft mobility, private vehicle, or public transport), except for Charquinho’s Garden, which is primarily accessible on foot. Benfica benefits from the proximity of the Sintra railway line, which strengthens the interconnection between locations.

Accessibility was assessed by parameters such as the ease of access, proximity, and internal accessibility. Internal accessibility issues were noted in parks such as Silva Porto Park and Eucaliptal Garden, where age-related challenges and lack of ramps impact usability, indicating a critical need to improve access and ensure equitable use. Silva Porto Park and Eucaliptal Garden also exhibit negative aspects owing to age-related challenges and steep slopes lacking ramps, handrails, and tactile paving.

It was observed that the Eucaliptal Garden’s playground could be improved by repairing the pavement or even its substitution by a softer material. These findings align with those of various research studies, which also emphasise the importance of accessibility in ensuring equitable use of urban green spaces. Recommendations include improving infrastructure to enhance accessibility and maintenance. Ensuring accessibility enhances inclusion and quality of life, which should be considered in future improvements.

The diversity of amenities offered in Benfica’s UGSs is linked to the available infrastructure and equipment. Thus, all the UGSs include pedestrian spaces, with Silva Porto Park and Quinta da Granja Urban Park offering the highest variety of activities, although they lack specific amenities like cycling spaces and pet-friendly areas (Table 5).

Table 5.

Activities that can be carried out in UGSs in Benfica. Source: [5].

The activities listed in Table 5, combined with the accessibility and quality parameters, formed the basis for the subsequent evaluation of user satisfaction and perceived well-being. Eucaliptal Garden lacks cycling and pet spaces but features a popular playground, in contrast to Charquinho Garden, which includes sports facilities but lacks a playground. Meanwhile, Baldaya Palace Garden and Maria’s Garden are both unsuitable for sports and primarily serve pedestrian use. Users seek stimulating and pleasant spaces that are easily navigable and well-integrated. The quality indicators assessed in this study reflect internationally recognised dimensions of UGS quality, such as safety, cleanliness, comfort, lighting, maintenance, and diversity of facilities. These attributes correspond to established frameworks demonstrating that perceived safety and adequate infrastructure are prerequisites for users to experience restorative and health benefits in urban green settings [18,19,31]. The consistency between users’ satisfaction scores and these theoretical dimensions reinforces the relevance of evaluating UGS quality as a multidimensional concept. Benfica’s UGSs offer diverse possibilities, catering to various user needs and providing physical and mental health benefits, whilst the urban structure of Benfica also supports a range of recreational options, contributing to overall well-being and social interaction.

The survey complemented the observation grid by examining user demographics, usage patterns, and health impacts. The analysis focused on the (i) age distribution of UGS users, (ii) frequency of UGS utilisation and reasons for selecting these spaces, and (iii) health impact of UGS usage before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most respondents were working-age adults (76.7%), with a notable presence of individuals aged 25 to 34 years (25.83%) and 35 to 44 years (20%). In contrast, younger age groups (18–24 years) and children (under 18) were less represented (11.67% and 1.67%, respectively). The user demographics reflect the general trends of the district, with UGSs typically frequented by nearby residents. Most respondents accessed the UGSs on foot, indicating short travel distances between their homes and the green areas. This functional proximity, inferred from the mode of access and frequency of visits, supports the interpretation that accessible UGSs contribute to residents’ perceived well-being. The survey results indicate that working-age adults (76.7%) are the primary users of UGSs, with a high frequency of daily visits to spaces such as Quinta da Granja Urban Park and Eucaliptal Garden. The usage patterns reflect the proximity of UGSs to users’ residences, with frequent visitors typically spending shorter periods in their local spaces. Comparison of these findings with studies that show that proximity and accessibility influence green space usage highlights the need for improved integration of UGSs into daily life to maximise their health benefits.

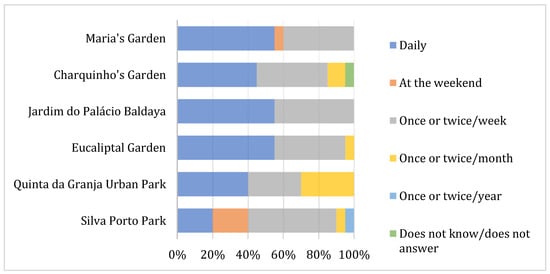

The frequency of UGS use (Figure 4) data show that most respondents visited daily, with Quinta da Granja Urban Park, Eucaliptal Garden, Baldaya Palace Garden, Charquinho Garden, and Maria’s Garden each reporting high daily visit rates. Weekly visits were reported by 41% of respondents, notably at Silva Porto Park (50%).

Figure 4.

Frequency of use of UGSs in Benfica. Source: [5].

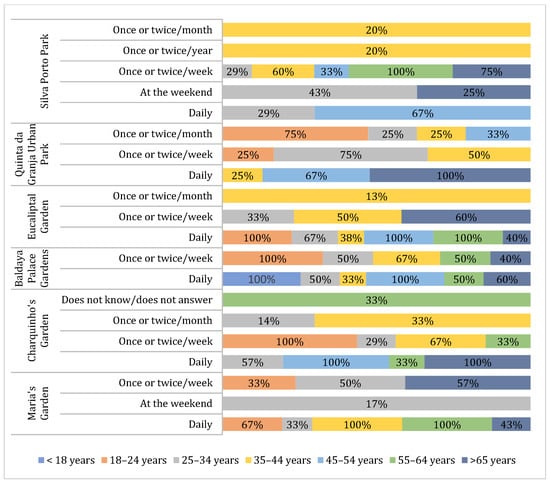

With regard to the age range (Figure 5), older groups tend to use UGSs every day, whereas individuals aged 25 to 44 visit these spaces once or twice a week, probably on their free days or weekends. This is likely due to differences in time availability.

Figure 5.

Frequency of UGS use by age in Benfica. Source: [5].

A significant number of visitors (40%) spend almost an hour in Silva Porto Park, while the urban agricultural activities of Quinta da Granja result in 35% of users spending over 120 min there. Visitors to the Eucaliptal Garden show varied usage patterns, with significant time spent on both physical and non-physical activities. Users were concentrated in three categories—between 20 and 40 min (25%), based on sports activities; between 61 and 90 min (25%); and between 91 and 120 min (25%), spent on both non-physical recreational activities such as reading and playing cards and using the restaurant infrastructure. A similar situation was observed in the Baldaya Palace Garden, which also has a café and restaurant that encourage people to stay for 41–60 min (25%) and 61–90 min (25%), respectively.

The diverse uses of UGSs cater to various user interests. Notably, the category “other”, encompassing activities such as socialising with friends, reading or studying, and engaging in sports, was prominently represented at Quinta da Granja Urban Park, accounting for 31%. This category is particularly associated with activities unique to this park, including the vegetable garden and cycling facilities.

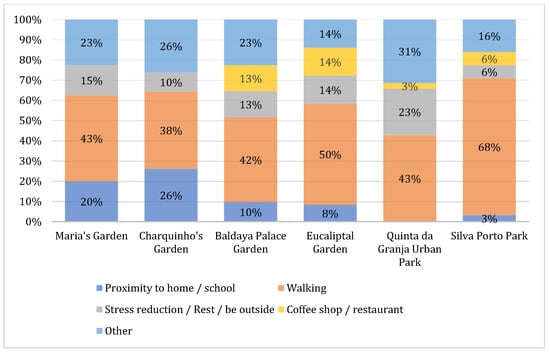

Although many studies mention the benefits of UGSs for physical health through participation in physical activities, this study reveals that the frequency and reasons why visitors like these spaces are related, in the case of most UGSs, to low-physical-intensity activities (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Thus, it is not only the number of UGSs that appears to be important but also their location (proximity) and accessibility as well as the diversity of available activities that allow users to enjoy moments of leisure and well-being and obtain the associated health benefits.

Figure 6.

Main reasons for choosing to visit UGSs in Benfica. Source: [5].

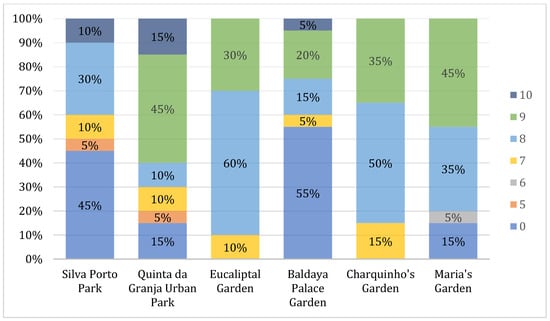

Since several authors have demonstrated that UGSs play a crucial role in promoting a good quality of life [38,50], users were also asked to self-assess the impact of UGSs on their health, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, UGSs provided essential physical and mental health benefits, especially for the elderly. While some spaces, such as Silva Porto Park and Baldaya Palace Garden, were closed during the period of confinement, many users reported an increase in visits to UGSs once the restrictions were lifted, accompanied by high satisfaction scores regarding the impact of UGSs on their physical and mental health (Figure 7). Hence, this study confirms that UGSs contributed significantly to both physical and mental health, particularly post-pandemic, as users continued to value their benefits for their overall well-being even after the lockdown. These findings can also be interpreted through the lens of restorative theories. The frequent motivations of “stress reduction”, “rest” and “being outside” correspond to the emotional and psychophysiological mechanisms described by the Stress Recovery Theory (SRT), where natural environments reduce stress responses and promote emotional regulation. Simultaneously, the predominance of low-intensity activities such as walking, contemplation, reading or sitting aligns with the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), as these activities involve “soft fascination” and support cognitive restoration. The reported improvements in mood, relaxation, and concentration—particularly among elderly and frequent users—demonstrate that Benfica’s UGSs enable both stress recovery and attention restoration in everyday conditions. Thus, residents’ behaviours and feelings empirically confirm the key assumptions of these theoretical models in a post-pandemic Southern European context.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of Benfica’s UGSs’ contributions to users’ physical and mental health during the COVID-19 confinement period, in percentages. Source: [5].

Additionally, the overall assessment indicates that UGSs are crucial for mental health, benefiting all age groups. Generally, the local UGSs were deemed sufficient, while community-driven UGS initiatives, such as in Maria’s Garden, received more positive feedback and could be expanded to other areas.

While Benfica’s UGSs have a positive impact on residents, evolving community needs should be addressed when making adjustments or during maintenance. Thus, enhancements are proposed to improve usage, foster interpersonal and intergenerational relationships, and enhance the district’s “healthy” and “human” dimensions. To effectively manage UGSs in the post-pandemic context, it is crucial to adopt an integrated, participatory approach involving community stakeholders [51]. UGSs are key to the Healthy City framework, which supports both physical and social environments to maximise human potential. The proposed interventions include reinforcing the green network, creating new UGSs, and enhancing existing ones, whilst the recommendations aim to address coverage gaps, increase the green space per inhabitant, and expand vegetation in underutilised areas or those negatively impacting the urban fabric, particularly in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 6).

Table 6.

Proposals for enhancing UGSs in Benfica. Source: [5].

The timing of the data collection, in the late phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (August–September 2021), influenced users’ behaviour and perception. Many respondents reported an increased need for outdoor recreation after prolonged confinement, associating green spaces with emotional relief and social reconnection. This contextual factor partly explains the higher visitation rates recorded among the elderly and families with children. The findings suggest that proximity to safe and well-maintained UGSs was crucial for psychological resilience during and immediately after the lockdown periods, reaffirming their role as public health infrastructures.

6. Conclusions

Urban environments are in a constant process of transformation to meet the physical and psychological needs of their inhabitants, increasingly emphasising the creation of healthy spaces that enhance overall well-being. Urban green spaces (UGSs) are vital to this endeavour, serving as indicators of environmental, economic, and social quality, thereby contributing to quality of life.

The reduction in natural areas within urban settings has fostered a disconnect between people and nature, reinforcing the need to promote access to UGSs as a public health priority. In contrast, exposure to nature provides numerous benefits for human well-being, underscoring the necessity of interventions that promote access to UGSs as a public health priority. The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified awareness of social and environmental issues, further underscoring the importance of UGSs during times of confinement. The pandemic has significantly altered behaviours and perceptions, highlighting the necessity of understanding how users evaluate the quality and quantity of UGSs.

This study focused on the impact of proximity to UGSs on activities across various demographic groups and its influence on the overall well-being of the population, specifically in the Benfica District of Lisbon, Portugal. Utilising a mixed-methods approach that integrated qualitative and quantitative techniques with cartographic analysis, the research provided a thorough examination of UGSs from the sociocultural and environmental perspectives. The findings reveal that UGSs in Benfica significantly enhance urban quality of life, improving aesthetics and offering recreational and sports opportunities. These spaces facilitate meaningful connections with nature, thereby positively impacting residents’ well-being.

Beyond confirming the relevance of urban green spaces for health and well-being during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, this study offers an applied contribution at the neighbourhood scale, responding to the need for place-based evidence in urban planning research. By integrating spatial analysis, field observation and user perceptions within a single local green structure, the findings provide insights that complement large-scale or method-specific studies, supporting planning and design decisions oriented towards liveability in ageing urban contexts.

The findings of this pilot study indicate that proximity and quality jointly influence how urban green spaces support liveability and health. While exact home-to-UGS distances were not measured, our usage patterns by mode of access (predominantly on foot) and self-reported travel time are consistent with previous research showing that closer walking catchments are associated with higher visit frequency and greater perceived physical and mental benefits, whereas parks offering better maintenance, safety and amenities tend to attract users from a wider area. This duality—proximity as enabler and quality as motivator—suggests that accessibility (safe, short walking access) and environmental quality (well-maintained, multifunctional settings) work together to encourage regular use and restorative experiences. Consequently, interventions should prioritise easy pedestrian access, maintenance quality, safety, and diversity of activities to engage user groups who traditionally underutilise these spaces.

Despite the evident benefits provided by UGSs in Benfica, certain limitations are noted. The study’s geographic focus on the Benfica District may not represent other urban contexts, and the reliance on self-reported data could introduce bias, potentially affecting the conclusions regarding the perceived benefits of UGSs. Consequently, this research should be viewed as a pilot study, with potential applicability to other districts.

Furthermore, the survey was conducted between August and September 2021, during the late phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. This timing may have influenced respondents’ perceptions, as reliance on and appreciation of urban green spaces were likely heightened following periods of confinement. Consequently, the reported benefits of UGSs might partially reflect this contextual sensitivity, reinforcing the importance of maintaining access to such spaces in times of social or health crises. Additionally, this study acknowledges that the sample size, although adequate for a pilot study at the neighbourhood scale, may limit the generalisability of the findings. However, field observation showed that the respondents were largely regular and habitual users of Benfica’s UGSs, which mitigates—though it does not fully eliminate—the risk of atypical or pandemic-specific usage patterns influencing the results. Thus, the behavioural tendencies observed are likely representative of routine interactions with these spaces, even beyond the COVID-19 period.

Although the UGSs in Benfica offer substantial benefits, there remains room for improvement, particularly in terms of accessibility, infrastructure, and maintenance. Tailored interventions that ensure ease of access, safety, diverse activities, and promotional initiatives can effectively engage users who typically do not utilise these spaces.

Integrating user feedback into nature-based health interventions and urban planning is crucial for developing inclusive and effective green infrastructure. Future research should investigate the barriers to accessing and utilising UGSs across various socio-economic contexts and employ longitudinal methodologies to assess the long-term effects of these spaces on public health. Furthermore, it is essential to explore the implementation of policies aimed at enhancing the quality and accessibility of UGSs, paying particular attention to vulnerable communities. These conclusions align with the One Health perspective (an integrated framework connecting human, animal, and environmental health), highlighting that accessible and biodiverse urban green networks can enhance both human and environmental well-being [39,52].

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.d.C.C., E.M.d.C. and S.M.; methodology, J.d.C.C., E.M.d.C. and S.M.; formal analysis, J.d.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.d.C.C., E.M.d.C. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, J.d.C.C., E.M.d.C. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia UID/295/2025CEG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, H. Exploring the Impact of Urban Built Environment on Public Emotions Based on Social Media Data: A Case Study of Wuhan. Land 2021, 10, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, E.M.; Fumega, J.; Louro, A. Defining Sustainable Communities: Development of a Toolkit for Policy Orientation. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2013, 6, 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.J. Urban health challenges in Europe. J. Urban Health Bull. 2013, 90, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, J.; Morgado, S.; Marques da Costa, E. Towards Healthier Cities. Urban Green Spaces (UGS) in the Neighbourhood of Benfica, Lisbon. In Proceedings of the 57th World Planning Congress of the International Society of City and Regional Planners “Planning Unlocked: New Times, Better Places, Stronger Communities”, Doha, Qatar, 8–11 November 2021; pp. 670–680, ISBN/EAN 978-90-75524-69-7. Available online: https://doha2021.dryfta.com/programme/discussions/sponsor-lounge/proceedings (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Cunha, J. Urban Green Spaces of Proximity and Healthy City: A Reading from the District of Benfica—Lisbon. Master’s Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, February 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/51741 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Morgado, S.; Cunha, J.d.C. Grounded in the Landscape—Climate Action, Well-being and Public Space in a Small Town in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Land 2023, 12, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, D.; Lukman, K.M.; Jingga, M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Quevedo, J.M.D.; Kohsaka, R. Urban Gardening and Wellbeing in PandemicEra: Preliminary Results from a Socio-Environmental Factors Approach. Land 2022, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirol, E.; Getaz, L.; Stoll, B.; Chappuis, F.; Loutan, L. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases 2014: Attaining the Nine Global Non-Communicable Diseases Targets; A Shared Responsibility; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J.; Qin, M.; Vlachantoni, A. Changing living arrangements and stress during COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from four birth cohorts in the UK. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 13, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, A.; Fleming, L.E.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.P.; Uyarra, M.C. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Wang, L. Environmental justice and park accessibility in urban China: Evidence from Shanghai. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2021, 63, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louro, A.; Marques da Costa, N.; Marques da Costa, E. From Livable Communities to Livable Metropolis: Challenges for Urban Mobility in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Portugal). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: Development of a theoretical framework. Environ. Urban. 2019, 32, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. New Leipzig Charter—The Transformative Power of Cities for the Common Good; New Leipzig Charter: Leipzig, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/brochures/2020/new-leipzig-charter-the-transformative-power-of-cities-for-the-common-good (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. Fact Sheet No. 358, Reviewed September 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs358/en/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Marques da Costa, E.; Kállay, T. Impacts of Green Spaces on Physical and Mental Health. URBACT Health & Greenspace. Urbact.eu. 2020. Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/media/thematic_report_no1_impacts_on_health_healthgreenspace_2910.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces and Health: A Review of Evidence; OMS; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urbanhealth/publications/2016/urban-green-spaces-andhealth-a-review-of-evidence-2016 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Urban. 2023, 35, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G. Selecting the best theory to implement planned change. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 20, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Garling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Avaliando o valor restaurador do ambiente: Um estudo sobre idosos em comparação com adultos jovens e adolescentes. Int. J. Psicol. 2007, 42, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Guest’s editors’ introduction: Restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S.; Zijlema, W.; Marquez, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Van de Berg, M.; Kruize, H.; Maas, J.; et al. Restoration in Mental Health after Visiting Urban Green Spaces: Who Is Most Affected? Comparison between Good/Poor Mental Health in Four European Cities. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, G.; Fielding, J.; Diercke, M.; Campese, C.; Enouf, V.; Gaymard, A.; Bella, A.; Sognamiglio, P.; Moros, M.J.S.; Riutort, A.N.; et al. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the WHO European Region, 24 January to 21 February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25, 2000178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y.; Diehl, J.A. A conceptual framework for studying urban greenspaces effects on health. J. Urban Ecol. 2017, 3, jux015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessoufou, K.; Sithole, M.; Elansary, H.O. Effects of urban green spaces on human perceived health improvements: Provision of green spaces is not enough but how people use them matters. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.K.; Jordan, H.C.; Horsley, J. Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and well-being: Prospects for planning. J. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Miwa, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological responses of young males during springtime walks in urban parks. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2014, 33, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, S. Lisbon: Metropolis and Urbanised Landscape. In Urban Developments in Brazil and Portugal; Nova Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Lorente, M.M. O Papel dos Espaços Verdes Urbanos na Promoção da Saúde: Uma Revisão Atualizada. Rev. Saúde Urbana 2022, 10, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, M.M. A Evolução do Conceito de Espaço Verde Público Urbano. Agros 1992, 75, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Lei nº 70/2020, of 4 September 2020. Diário da Repúlblica No. 173/2020 II Series. Alteration by Adaptation of the Lisbon Municipal Master Plan. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/declaracao/70-2020-141967637 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Telles, G.R. Plano Verde de Lisboa: Componente do Plano Director Municipal de Lisboa; Colibri: Lisboa, Portugal, 1997; ISBN 978-9728288747. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.B.; Andersson, E. A Transdisciplinary Framework to Unlock the Potential Benefits of Green Spaces for Urban Communities Under Changing Contexts. BioScience 2023, 73, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML). Estratégia de Biodiversidade Urbana de Lisboa; CML: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. Available online: https://www.lisboa.pt/temas/ambiente/estrategia (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- European Commission. European Green Capital 2020: Lisbon—Summary Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/urban-environment/european-green-capital-award/winning-cities/lisbon-2020_en (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2011 Population and Housing Census: Resident Population by Place of Residence and Demographic Indicators (Population Change, Population Density, Youth Dependency Ratio, Elderly Dependency Ratio); INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2021 Population and Housing Census: Resident Population by Place of Residence and Demographic Indicators (Population Change, Population Density, Youth Dependency Ratio, Elderly Dependency Ratio); INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2011 Population and Housing Census: Resident Population by Age Group and Sex, Benfica Parish; INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2021 Population and Housing Census: Resident Population by Age Group and Sex, Benfica Parish; INE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patwary, M.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Uddin, M.N. Exposure to Urban Green Spaces and Mental Health During Post-Lockdown Recovery. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1334425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refisch, M.; Kurz, K.; Hartmann, J. Urban Green Space Usage and Life Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024, 19, 1139–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomitaka, M.; Takano, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Sasaki, T. Shifting Roles of Urban Greenspace Types in Supporting Subjective Well-Being Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 9, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Wang, W.; Fu, S.; Zeng, W. An Investigation of the Restorative Benefits of Different Spaces in an Urban Riverside Greenway for College Students—A Simple Autumn Outdoor Experiment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agência Europeia do Ambiente. Construir o Futuro que Queremos Ter, 1st ed.; Serviço das Publicações da União Europeia: Luxemburg, 2012; ISBN 978-92-9213-269-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ko, Y.; Kim, W.; Kim, G.; Lee, J.; Eyman, O.T.G.; Chowdhury, S.; Adiwal, J.; Son, Y.; Lee, W.-K. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Perception and Use of Urban Green Spaces in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez Castañeda, N.; Pineda-Pinto, M.; Gulsrud, N.M.; Cooper, C.; O’Donnell, M.; Collier, M. Exploring the Restorative Capacity of Urban Green Spaces and Their Biodiversity through an Adapted One Health Approach: A Scoping Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 100, 128489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.