Abstract

Post-industrial waterfronts have become key arenas of urban transformation, where heritage, public space and social equity intersect. This study examined the Xuhui Waterfront in Shanghai under the ‘One River, One Creek’ initiative, which converted former industrial land into a continuous riverfront corridor of parks and cultural venues. The research aimed to evaluate whether this large-scale renewal enhanced social equity or produced new forms of exclusion. A tripartite analytical framework of distributive, procedural and recognitional justice was applied, combining spatial mapping, remote-sensing analysis of vegetation and heat exposure, housing price-to-income ratio assessment, and policy review from 2015 to 2024. The results showed that the continuity of the riverfront, increased greenery and adaptive reuse of industrial structures improved accessibility, environmental quality and cultural enjoyment. However, housing affordability became increasingly polarised, indicating emerging gentrification and generational inequality. This study concluded that this dual outcome reflected the fiscal dependency of state-led renewal on land-lease revenues and high-end development. It suggested that future waterfront projects could adopt financially sustainable yet inclusive models, such as incremental phasing, public–private partnerships and guided self-renewal, to better reconcile heritage conservation, public-space creation and social fairness.

1. Introduction

In many post-industrial cities, former docks, factories and warehouses along rivers or coasts became underused or derelict as economic structures shifted. To reclaim these waterfront zones, cities embarked on urban renewal strategies to convert industrial land into parks, promenades, cultural facilities or mixed-use developments [1]. Such redevelopment often carried ambitions of enhancing urban liveability, reconnecting citizens with water, and stimulating economic growth [2]. However, in practice waterfront renewal has frequently generated contested outcomes in terms of social equity. While some residents or visitors gained access to newly-opened public space, others were displaced, excluded, or priced out. Critics argued that urban renewal tended to favour capital investment, high-end commercial or residential uses, and aesthetic branding, often reinforcing social stratifications rather than redressing them [3].

The notion of spatial justice or social equity in urban space emphasises not only distributional fairness (who obtains access to services, environment, mobility) but also procedural fairness (who participates in decision-making) and recognitional fairness (whose values, identities are respected). This tripartite idea is widely used in urban studies to critique urban renewal projects that look beautiful but are socially exclusionary [4]. Thus, assessing a waterfront urban renewal project through the lens of social equity means asking the following: Did the urban renewal genuinely improve access, inclusion and fairness, or did it privilege certain populations and intensify inequality?

In Shanghai, the Huangpu River and Suzhou Creek, often regarded as the cradle of China’s national industry, played a pivotal role in the city’s modern development. Their convenient waterways greatly facilitated industrial growth and connected Shanghai’s manufacturing sector with both inland regions and overseas markets. Until the 1990s, extensive stretches along the riverbanks were occupied by factories, warehouses and shipyards that symbolised the city’s industrial prosperity. However, in the post-industrial era, many of these facilities suffered from declining productivity and inefficient land use. In response, the municipal government put forward the ‘One River, One Creek’ (OROC, 一江一河) initiative as a strategic framework to reclaim and open the banks of the Huangpu River and Suzhou Creek to the public by creating a continuous riverside open-space corridor that integrates ecological improvement, public access, urban landscape, and heritage conservation. Under this policy, large sections of formerly industrial or infrastructural waterfront in central districts (including Xuhui, Changning, Huangpu, etc.) were targeted for transformation into promenades, green corridors, cultural nodes and recreational spaces. The OROC initiative was not only about landscape aesthetics, but also framed politically as a public service and quality-of-life upgrade. Yet the governance of such megaprojects often involved powerful state and developer actors, with high centralised planning control. Critics have cautioned that such top-down strategies risk sidelining local voices and reinforcing urban inequality, if local socio-spatial dynamics are not carefully integrated [3].

In this case, early waterfront initiatives (e.g., the Huangpu riverfront promenades) gained visibility by claiming to ‘return the river to the people’, yet observers noted that those promenades often attracted higher-income users and commercial uses, rather than serving disadvantaged neighbourhoods in equal measure [3]. Thus, while OROC symbolically elevated the importance of the riverside as public realm, the social equity consequences of its implementation remained underexplored: particularly with regard to who benefitted, who was excluded, and how heritage and identity were negotiated.

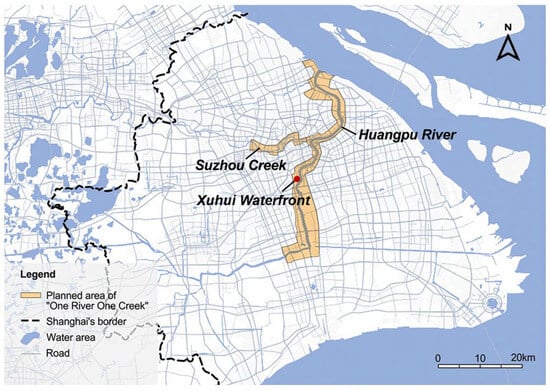

Within the framework of the OROC initiative, Xuhui Waterfront represented a significant case of post-industrial urban renewal in Shanghai (Figure 1) [3]. The area had long been characterised by warehouses, factories and transport infrastructure along the Huangpu River, yet over the past decade it was progressively converted into open public spaces, greenways, cultural venues and a continuous riverside promenade. This transformation raised critical questions about whether the project genuinely enhanced social equity or, conversely, introduced new tensions between heritage preservation, public space provision and processes of gentrification.

Figure 1.

Area of OROC initiative and location of Xuhui Waterfront in Shanghai. Source: Marked by authors on the image illustrated by Feng et al. [3].

This study therefore investigated the extent to which accessibility to public space, cultural facilities and transport improved for different socio-spatial groups, whether environmental quality gains such as greening and heat mitigation were equitably distributed, and how far housing affordability altered in ways that might generate displacement pressures. Attention was also given to the inclusiveness of decision-making processes and the degree to which heritage and identity were incorporated or contested, including the narratives that were foregrounded in the urban renewal.

Against this background, this paper pursued three interrelated objectives. First, it aimed to establish a justice-based framework for assessing social equity in post-industrial waterfront urban renewal that brings together distributive, procedural and recognitional dimensions in a single analytical lens. In this study, the framework is operationalised through a mixed set of spatial, environmental, economic and institutional indicators, some derived from quantitative mapping and remote-sensing analysis and others from documentary and field-based evidence. Second, the paper evaluates changes in equity outcomes in the case of Xuhui Waterfront by combining spatial analysis, environmental datasets, housing affordability metrics and governance review. Third, it reflects on policy and design lessons for how future waterfront urban renewal in Shanghai and other cities might more effectively balance heritage, public-space provision and protection against displacement.

This study therefore integrates the distributive, procedural and recognitional dimensions of social equity into the analysis of a flagship Chinese waterfront urban renewal project. Unlike most existing studies, which tend to examine one or two aspects of justice in isolation, it explicitly links accessibility, environmental change, housing affordability and governance arrangements and heritage representation within a coherent evaluative structure. By applying this structure to the Xuhui Waterfront, the research moves beyond conventional accounts of physical renewal or aesthetic transformation and reveals how state-led waterfront opening can generate both expanded public access and intensified housing-market polarisation. It contributes new empirical evidence from Shanghai, where the OROC initiative has been implemented as a large-scale state-led programme, and advances international debates on post-industrial waterfronts by highlighting the justice implications of land-finance-dependent renewal strategies that can better reconcile heritage, public space and social inclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Equity and Urban Renewal: Distributive, Procedural and Recognitional Justice

Theories of justice in urban planning had long recognised that spatial interventions could entrench or challenge inequalities. Harvey argued that capitalist urbanisation embedded uneven development in the built environment, with planning often serving accumulation rather than redistribution [5]. Soja later developed the notion of spatial justice, emphasising that access to opportunities was mediated through spatial configurations and should be understood as a dimension of social justice in its own right [6].

Fainstein articulated the ‘just city’ framework, identifying equity, democracy and diversity as normative criteria, and prioritising equity when values conflicted [7]. In practice, three interlinked dimensions of justice were commonly applied. Distributive justice concerned the allocation of resources and services, often measured through accessibility indices, housing affordability or exposure to environmental risks [8,9]. Procedural justice related to the inclusiveness of decision-making processes, with Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation still a touchstone for evaluating degrees of empowerment [10]. Recognitional justice, advanced by Fraser, referred to the acknowledgement of cultural difference and minority voices, highlighting that misrecognition perpetuated social subordination [11].

Based on these three dimensions, scholars have progressively operationalised the three dimensions of justice into indicators that can be applied in empirical studies of urban renewal. Building on distributive, procedural and recognitional frameworks, researchers have proposed metrics spanning accessibility to public services, housing affordability, environmental exposure, participatory practices and cultural inclusivity. These indicators, drawn from established literature in planning, transport, environmental justice and community studies, provide a systematic basis for assessing how renewal projects reshape equity outcomes. Table 1 summarises the key indicators adopted in previous studies, their modes of measurement, and the theoretical or empirical sources on which they rest. This triadic model had been increasingly applied in urban renewal studies, yet operationalisation remained uneven. Accessibility and affordability were well-developed as distributive indicators, while procedural and recognitional justice were more difficult to measure empirically and often neglected in evaluations [12].

Table 1.

Indictors to evaluate the social equity of a renewed urban area in existing research.

2.2. Heritage and Post-Industrial Waterfronts: Global and Chinese Perspectives

Heritage had long been a critical dimension of post-industrial waterfront urban renewal. International experiences showed that the adaptive reuse of warehouses, docks and shipyards often became a strategy to rebrand waterfronts and stimulate economic restructuring. In Barcelona, the redevelopment of Port Vell integrated leisure, tourism and cultural uses, reshaping the waterfront into a flagship of the city’s global image [24]. Similar patterns were observed in other European and North American cities, where historic industrial elements were selectively preserved to support place marketing, while ordinary layers of working-class heritage were frequently erased [25,26]. Such practices highlighted the tension between cultural conservation and market-oriented redevelopment.

In the Chinese context, similar dynamics unfolded as waterfronts were repositioned as cultural corridors and public amenities. Along the Huangpu River and Suzhou Creek, industrial heritage was often converted into art museums, cultural centres or creative clusters. Luo and Cao documented how eleven industrial heritage sites in Shanghai were transformed into museums, arguing that while such interventions claimed to reconstruct urban memory, they often produced curated narratives aligned with city branding [27]. Ma, Li and Lan examined the West Bund redevelopment in Xuhui, identifying a ‘dual adaptive reuse’ strategy that combined cultural programming and landscape enhancement. They noted that this approach enhanced accessibility and environmental quality, yet also risked reinforcing social filtering by catering more to affluent groups [28].

Other studies pointed out that heritage reuse in China was closely tied to state-led agendas of spatial upgrading and economic accumulation. Zhang argued that Shanghai’s industrial heritage was mobilised in connection with mega-event logics, embedding heritage within growth-oriented planning strategies rather than community-based inclusion [29]. Zhu and Li further proposed that the concept of ‘sharing’ should underpin heritage revitalisation along urban waterways, emphasising visibility, accessibility and participatory governance as essential conditions for realising heritage’s public value [30].

These cases showed that heritage in waterfront urban renewal was often instrumentalised to produce spectacle, attract investment and foster cultural capital, while issues of equity, accessibility and recognition remained secondary. This highlighted the importance of examining not only which heritage elements were preserved, but also whose histories were represented and who was enabled to access these regenerated spaces.

2.3. Public Space, Gentrification and Environmental Justice

The creation of parks and open spaces had been widely celebrated as a hallmark of waterfront urban renewal. Yet critics warned of the paradox of ‘green gentrification’. Wolch et al. showed that greening in Los Angeles produced ecological benefits but simultaneously displaced vulnerable communities through rising property values [15]. Rigolon reviewed studies globally and confirmed persistent inequities in access to parks, measured through indicators such as residents within a 10–15 min walk [16]. Sister et al. proposed metrics of ‘park pressure’, capturing the imbalance between parkland and resident populations [17].

Environmental justice scholarship added ecological indicators. Harlan et al. revealed that disadvantaged Phoenix neighbourhoods suffered higher exposure to heat stress, measured through normalized difference vegetation index and land surface temperature [18]. Quinton et al. reviewed empirical studies of green gentrification and recommended combining housing market data with environmental indicators to capture displacement dynamics [31]. Cucca et al. (2023) further stressed that waterfronts represented a distinct form of blue gentrification, where riverside greening produced unique dynamics of displacement [32].

Thus, the provision of new riverside parks and cultural venues could not be assumed to enhance equity without examining indicators of access, affordability, environmental quality and social inclusion.

While literature on waterfront urban renewal was extensive, four gaps were evident. First, empirical applications of distributive–procedural–recognitional justice frameworks to waterfront contexts remained limited, particularly in East Asia. Second, indicators were often studied in isolation, with accessibility, affordability, environmental metrics and participation rarely integrated. Third, procedural and recognitional justice were under-operationalised, with participation often tokenistic and heritage voices marginalised. Fourth, Chinese cases were underrepresented in comparative debates, despite rapid transformations in cities like Shanghai.

To address these shortcomings, the present study assembled an indicator framework grounded in established research. Indicators included accessibility to public transport and parks [8,16], service accessibility [21], environmental quality measured through tree cover and mean annual temperature [18], housing affordability [9] and public participation [10]. This integration enabled a holistic evaluation of distributive, procedural and recognitional justice in the Xuhui Waterfront’s urban renewal.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area and Data

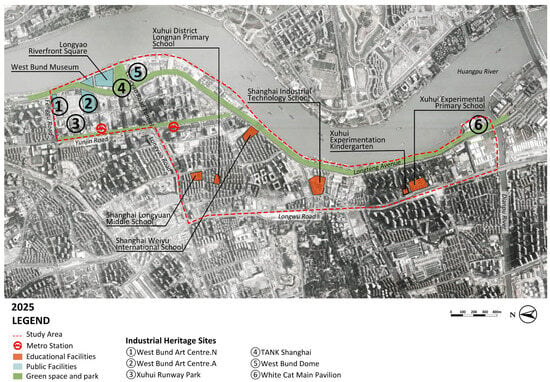

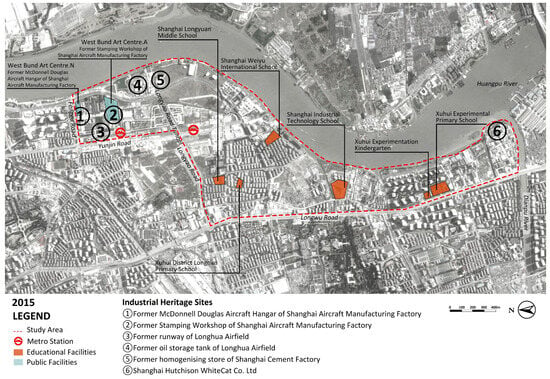

The study focused on the core part of the Xuhui Waterfront in Shanghai, defined by the boundaries of Fenggu Road, Yunjin Road, Longyao Road, Longwu Road, the Dianpu River and the Huangpu River (Figure 2). This area formed a central section of the OROC initiative and represented one of the most visible examples of post-industrial urban renewal in the city, as documented in the Xuhui Waterfront development plans and recent analyses of Shanghai’s waterfront redevelopment [33,34,35,36,37]. Historically, the district contained warehouses, shipyards and industrial facilities that had supported Shanghai’s manufacturing economy during the twentieth century (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Satellite images of Xuhui Waterfront in 2025. Source: Authors marked on satellite images provided by Maxar.

Figure 3.

Satellite images of Xuhui Waterfront in 1979. Source: Authors marked on satellite images provided by National Platform for Common GeoSpatial Information Services of China.

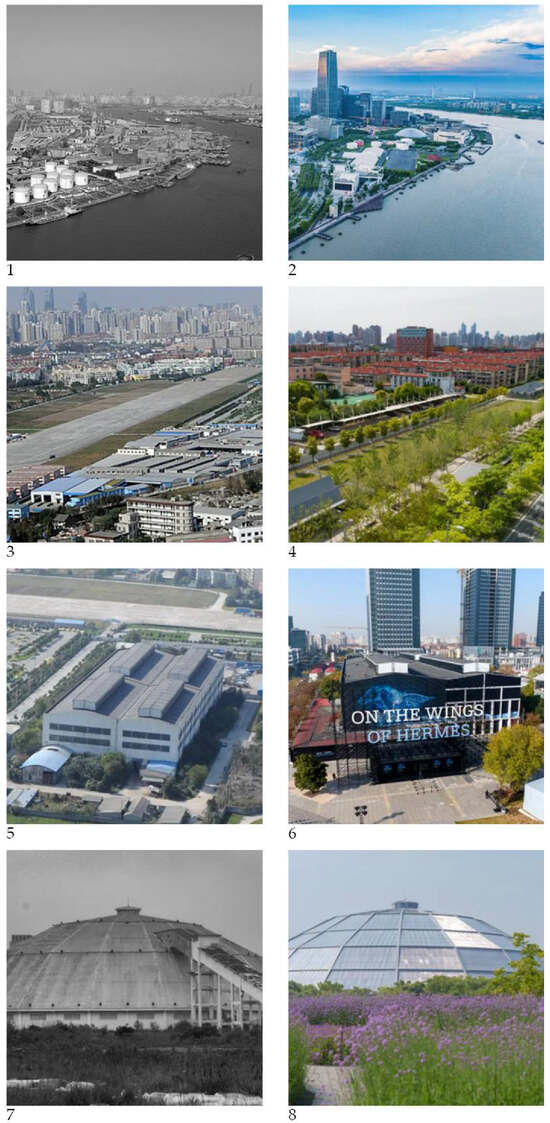

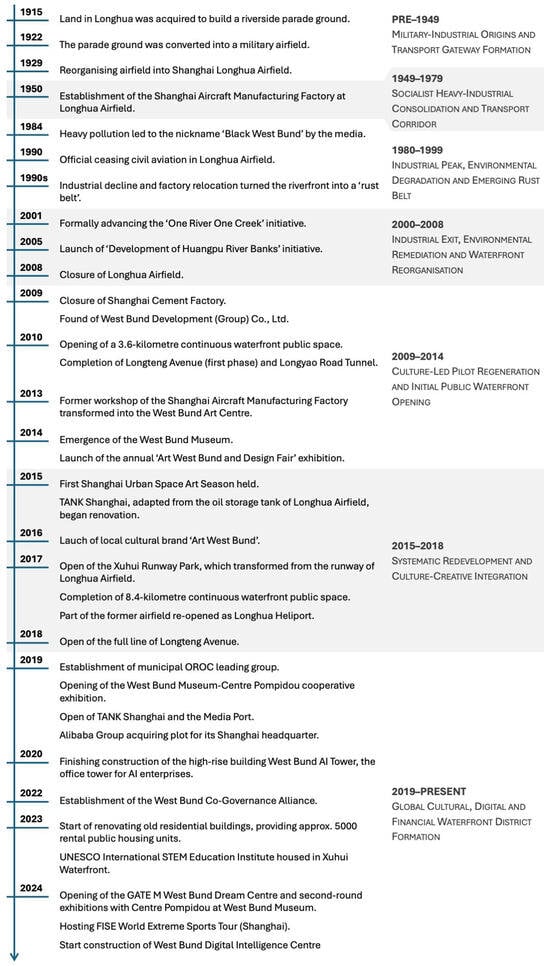

From the 1990s onwards, Shanghai’s urban development entered a transition from an industrial to a post-industrial trajectory, and the waterfront began to shift from a production-oriented riverside to one oriented towards ecological restoration and public use. In 2001 the Shanghai’s municipal master plan (1999–2020) formally advanced the OROC initiative, and between 2002 and 2010, in preparation for the 2010 World Expo, land assembly and enterprise relocation were intensified alongside the Huangpu River, with approximately 3400 enterprises removed from the area. Within this broader process, the Xuhui Waterfront underwent major industrial exit between 2005 and 2008, including the closure of the freight zones of Shanghai Longhua Airfield, and Shanghai Cement Factory, the relocation of roughly 12,000 households, enterprises and public institutions, and the construction of Longteng Avenue and the Longyao Road Tunnel. This reorganised the former ‘Black West Bund’ industrial belt into a reservable riverside land bank. Between 2009 and 2014 the area entered a culture-led pilot phase: the West Bund Development Group was established and proposed a 3.6-km riverside cultural corridor to the public. Early flagship projects such as the Long Museum (West Bund) and the West Bund Art Centre were completed, although the overall focus remained on environmental remediation and demonstration projects rather than comprehensive redevelopment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Satellite images of Xuhui Waterfront in 2015. Source: Authors marked on satellite images provided by DigitalGlobe.

From 2015 onwards, the Xuhui Waterfront shifted from environmental clean-up and symbolic opening to more systematic redevelopment and functional diversification. Industrial heritage reuse and linear open space projects, exemplified by the Shanghai Urban Space Art Season, the renovation of TANK Shanghai and the conversion of the former runway of Shanghai Longhua Airfield into Xuhui Runway Park, rapidly expanded the network of waterfront public spaces and cultural facilities. By the time the 45-kilometre continuous waterfront in the central city was fully opened in 2017, these projects had redefined the urban landscape (Figure 5), consolidating the district’s image as a culture-led flagship of Shanghai’s waterfront renewal [27,28,38].

Figure 5.

Landmarks in Xuhui Waterfront before and after renewal. From up to down: former oil storage tank of Longhua Airfield (1) vs. current TANK Shanghai (2); former runway of Longhua Airfield (3) vs. current Xuhui Runway Park (4); former Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Factory (5) vs. current West Bund Art Centre (6); former homogenising store of Shanghai Cement Factory (7) vs. current West Bund Dome (8). Source: West Bund Development (Group) Co., Ltd.

In 2019, the municipal OROC leading group was established to steer the creation of a world-class waterfront district, and the Xuhui Waterfront had effectively been transformed from a decommissioned industrial belt into an emerging riverside district hosting cultural venues [39]. At the same time, high value-added industries and capital began to concentrate through developments such as the completion of the Media Port (2019) and the West Bund AI Tower (2020), triggering land value restructuring and the superimposition of environmental improvements, public space expansion, industrial upgrading and gentrification pressures (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Timeline for the formation and redevelopment of Xuhui Riverside. Source: Illustrated by the author.

The empirical analysis relied on data collected between 2015 and 2024, integrating spatial mapping, environmental datasets and socio-economic information. The distribution of public facilities, including metro stations, schools and hospitals, was identified through current urban maps, historical satellite imagery and field investigations conducted in 2024 and 2025. These sources enabled the comparison of facility numbers and spatial configurations before and after urban renewal. Information on parkland and open spaces was obtained through time-series imagery from Google Earth (2015–2024) combined with on-site surveys. Visual comparison allowed identification of newly created or expanded green areas along the waterfront. Tree-cover data were drawn from the Global 2000–2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset derived from the Landsat archive [40]. Local and citywide temperature data were acquired from the Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, official meteorological bulletins and the World Data Centre for Renewable Resources and Environment dataset [41]. The land-cover product has a native spatial resolution of 30 m, which is suitable for identifying corridor-scale changes in vegetated land along the riverfront but cannot fully capture very small parks, planting strips or street trees. The temperature dataset is provided at a 1 km grid resolution and was used to derive mean annual air temperature for Shanghai and the Xuhui Waterfront. Given these moderate resolutions, the environmental indicators are interpreted as reflecting broad patterns of greening and heat moderation at the waterfront-corridor scale, rather than microclimatic variations at the level of individual plots or streets. Housing price and residential data were obtained from governmental bulletins and third-party research institute. The dataset included 812 second-hand housing transactions across 18 residential compounds between 2015 and 2024, forming the basis for the price-to-income ratio (PIR) analysis. Policy documents, planning guidelines and consultation records were reviewed to evaluate the procedural and recognitional dimensions of social equity, including the degree of public participation and heritage representation in urban renewal narratives. These official sources were interpreted as policy discourses produced by state and corporate actors rather than neutral descriptions, and were cross-checked against critical scholarship on Shanghai’s waterfront redevelopment, which has highlighted the strongly state-centred character of decision-making, the limited channels for bottom-up participation and the selective mobilisation of industrial heritage for city-branding purposes. Within this constrained evidence base, the findings for procedural and recognitional justice should therefore be understood as indicative of formal institutional design and dominant narratives rather than a comprehensive account of residents’ everyday experiences.

3.2. Analytical Framework for Social Equity Assessment

The evaluation of social equity in the Xuhui Waterfront urban renewal adopted a tripartite framework encompassing distributive, procedural and recognitional justice [5,6,7]. Each dimension was operationalised through two operational indicators, combining spatially explicit measures with qualitative institutional evidence, selected for their theoretical significance and compatibility with available data between 2015 and 2024. This framework enabled an integrated assessment of spatial, environmental, socio-economic and cultural aspects of equity within the context of the OROC initiative. This is an exploratory, indicator-based case study. The analysis relies on descriptive comparisons of pre- and post-renewal conditions, spatial visualisation and qualitative interpretation of policy and branding documents to identify patterned changes in the three dimensions of justice, rather than on inferential statistical models or causal estimation.

3.2.1. Distributive Justice

Distributive justice concerns the fair allocation of spatial and material resources among different social groups. In this study, it was represented by four interrelated indicators: accessibility to transport and public facilities, park accessibility and open-space provision, environmental quality and housing affordability.

Accessibility to metro stations, schools and hospitals reflected the equitable distribution of essential services, aligning with approaches in transport and urban justice research [8,13]. Facility locations and metro stations were compiled from municipal planning documents and online mapping platforms. For 2015 and 2024, the number and spatial distribution of metro stations, primary and secondary schools and hospitals within and immediately around the study area were mapped. Comparative map interpretation and field observation were also employed to identify gains or losses in accessibility.

Park accessibility and open-space provision captured the physical continuity and reach of the riverside promenade, consistent with environmental equity frameworks in relevant research [15,16]. The extent of riverside parks and pedestrian corridors was delineated from satellite imagery and official planning drawings for 2015 and 2024, and was verified through site visits, in order to assess whether a continuous public waterfront had been created and how far public access extended inland.

Environmental quality was represented through tree cover and mean annual temperature, following studies that link urban greening and microclimate to social vulnerability [18]. Tree cover for the Xuhui Waterfront and for Shanghai as a whole was derived from the Global 2000–2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change dataset, and annual mean temperature series were obtained from the 1 km resolution monthly mean temperature dataset for China [40,41]. Gridded values (30 m for land cover and 1 km for temperature) were aggregated over the study area and municipal boundary to compare long-term greening and cooling trends, while recognising that variations below the grid size could not be fully captured.

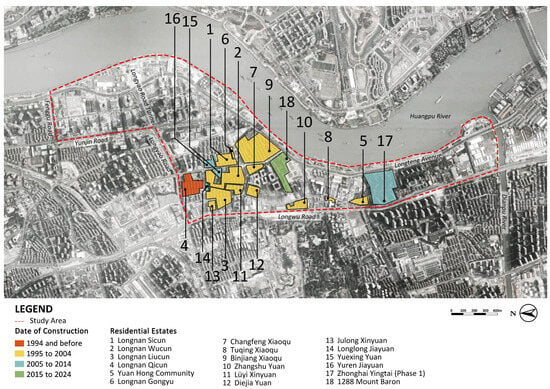

Housing affordability was evaluated using the price-to-income ratio (PIR), a widely applied measure for assessing housing burden in international and Chinese scholarship [9]. Given the effect of government regulation on the primary housing market, new housing prices did not fully reflect the balance between demand and supply. For this reason, second-hand housing transaction prices were used as the more accurate indicator of real market conditions. A dataset comprising 812 transactions from 18 residential estates within the research area between 2015 and 2024 was obtained from the fang.com platform. These estates are distributed across most of the residential sub-areas of the Xuhui Waterfront and were developed in different periods, so the sample was considered to provide a reasonable representation of housing products and transaction activity in the residential portions of the study area (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Locations of the 18 residential estates for evaluating PIR. The northern parts of the study area are mainly redeveloped as business and recreational functions, with only few residential estates.

To establish a reliable benchmark, the overall Xuhui District was taken as the ground truth. As the district-level PIR was not officially published, the ratio was estimated following the method of the Linping Juzhu Dashuju Yanjiuyuan (麟评居住大数据研究院, literally Linping Residential Bigdata Institute), which combined average housing area, disposable household income and district-level second-hand housing prices [42]. In this study, per capita housing area and disposable income were obtained at the scale of Shanghai Municipality because consistent annual statistics at district level were not available for Xuhui between 2015 and 2024. This choice also reflects the effective catchment of the Xuhui Waterfront housing market. As a flagship inner-urban waterfront, its potential buyers are drawn from across the whole city rather than from incumbent residents of Xuhui District alone, and there are no institutional restrictions on intra-urban migration within Shanghai. City-level averages therefore provide a reasonable approximation of the housing space and income conditions of typical purchasers in this segment of the market, whereas price levels are more strongly tied to location and are captured using district-level second-hand housing data for Xuhui. The PIR of Xuhui District was calculated according to the following formula (Equation (1)):

where was the PIR of Xuhui District, was the per capita housing area in Shanghai, was the average second-hand housing transaction price in Xuhui District, and was the yearly per capita disposable income of Shanghai’s urban residents.

The PIR of each residential estate in the Xuhui Waterfront was calculated by dividing the transaction price of each unit by the annual per capita disposable income of Shanghai’s urban residents (Equation (2)):

where was the PIR of each transaction, was the total price of each second-hand housing transaction, and was the yearly per capita disposable income of Shanghai’s urban residents.

The annual PIR of Xuhui District between 2015 and 2024 was summarised in Table 2. For each of the eighteen residential compounds, the maximum and minimum PIRs during the ten-year period were calculated, and the results were presented in Table 3. To eliminate the effect of price fluctuations and to obtain a normalised series, the maximum and minimum PIRs were adjusted against the Xuhui District PIR, and the ten-year average was added to retain the interpretative meaning of PIR as the number of years of income required to purchase a dwelling (Equation (3)).

where was the normalised PIR for each transaction, was the PIR of each transaction, and the was the PIR of Xuhui District. This normalisation was adopted to control for broader market cycles and citywide policy interventions affecting Shanghai’s housing market. Using the Xuhui District PIR as a benchmark allowed estate-level trajectories in the Xuhui Waterfront to be interpreted in relative rather than absolute terms. The indicator therefore highlights whether specific compounds became more or less affordable compared with the surrounding district under shared municipal income conditions. At the same time, relying on city-level averages for income and housing space may overlook intra-district socio-economic differences and under-represent the burden on lower-income groups. The PIR results are therefore interpreted as indicators of relative affordability pressure and social stratification within the wider Shanghai housing market, rather than as precise measures of the housing burden faced by specific income groups in Xuhui District.

Table 2.

Per capita housing area in Shanghai, average second-hand housing transaction price in Xuhui District, yearly per capita disposable income of Shanghai’s urban residents and PIR of Xuhui District from 2015 to 2024.

Table 3.

Yearly maximum and minimum price and PIR of the transactions in Xuhui Waterfront from 2015 to 2024.

3.2.2. Procedural Justice

Procedural justice focuses on fairness in decision-making and the inclusiveness of governance processes. In this study it examined how planning institutions designed and implemented public participation, transparency and accountability mechanisms during the area’s redevelopment. Because direct participatory data, such as interviews, focus groups or ethnographic observation, were not available, the analysis relied on a qualitative review of planning guidelines, statutory plans, design briefs, consultation summaries and official media reports. Particular attention was paid to (a) the formal channels through which residents and stakeholders could be informed or consulted, (b) the timing of engagement within the planning and implementation cycle, and (c) the presence or absence of feedback mechanisms that allowed comments to influence subsequent decisions. These materials were treated as policy narratives produced by state and corporate actors, not as neutral records of civic engagement, and were interpreted in the light of critical studies that have shown how Shanghai’s waterfront projects remain strongly state-centred with restricted opportunities for bottom-up participation and deliberation [30,35,36,38,43]. Drawing on Arnstein’s ladder, the assessment distinguished between different levels of empowerment from informing and consultation to partnership and citizen control [10], but it should be understood as capturing the design of formal mechanisms and publicly reported interactions rather than the full spectrum of residents’ experiences. Future research may extend this dimension through structured interviews or participatory mapping to further capture stakeholder experiences and perceptions.

3.2.3. Recognitional Justice

Recognitional justice concerns the acknowledgement of diverse cultural identities, values and histories within the urban renewal process [11,23]. In this study, recognitional justice was examined through the representation and accessibility of industrial heritage and cultural spaces. Planning and branding documents, official project descriptions, museum and gallery websites, and local media reports on key adaptive reuse projects such as TANK Shanghai and the West Bund Art Museum were qualitatively analysed to trace how industrial histories, neighbourhood communities and creative-class lifestyles were narrated. Particular attention was paid to (a) which historical actors and communities were explicitly mentioned or visually highlighted, (b) how industrial structures and landscapes were renamed and reframed in the renewal process, and (c) how cultural users and everyday audiences were imagined in the textual and visual descriptions. The analysis compared these narratives with the pre-renewal uses of the sites and with critical scholarship on Shanghai’s waterfront redevelopment, in order to identify whose experiences were foregrounded and whose were marginalised. The indicator considered whether the adaptive reuse of factories and warehouses into museums or creative venues reflected inclusive narratives of local identity, or whether it privileged elite cultural consumption. This perspective indicated that equity should be evaluated not only by material distribution but also by whose voices and histories are recognised in the urban landscape [7]. Existing research on Shanghai’s waterfront and industrial-heritage renewal has shown that such projects frequently mobilise heritage to support creative-economy strategies and city branding while marginalising working-class and community memories [27,28,29,30,35]. Against this background, the findings on recognitional justice in this paper indicate whose voices and histories are formally recognised in the renewed urban landscape but do not substitute for in-depth participatory research on how different groups interpret and inhabit these spaces.

Across these three dimensions and six indicators, the study adopted a straightforward comparative design rather than constructing a composite index. For distributive justice, conditions around the mid-2010s baseline and the situation after the main phase of renewal were compared by examining changes in counts, spatial configurations and relative values. Tree-cover change was taken directly from the 2015–2020 land-cover dataset [40], while annual mean temperatures were extracted from the gridded dataset [41] and official statistics to compare long-term warming and potential moderation at the riverfront. Housing affordability was assessed using the PIR indicators described above, focusing on divergence between maximum and minimum values relative to the district benchmark. Procedural and recognitional justice were evaluated qualitatively through planning documents, policy statements, branding materials and media reports. By structuring the analysis across these three dimensions and six indicators, the framework provided a coherent and transparent basis for assessing the social equity outcomes of the Xuhui Waterfront urban renewal, while recognising that the evidence for procedural and recognitional justice is derived primarily from formal documentation and existing scholarship rather than from primary participatory data.

4. Results

4.1. Distributive Justice: Spatial, Environmental and Economic Equity

4.1.1. Accessibility to Public Facilities and Services

Accessibility represents a fundamental aspect of distributive justice, reflecting whether the benefits of urban renewal are spatially and socially equitable. The comparison results between 2015 and 2024 show that the quantity and spatial configuration of essential public facilities remained largely unchanged over the past decade. The area continued to be served by the same metro lines (mainly Line 11), with stations at Longyao Road and Yunjin Road; no new educational or medical facilities were added within the redevelopment zone (Figure 2). This relative stability indicates that the formal accessibility, which was defined by the distance and travel time to basic services, did not significantly improve through facility provision itself. However, accessibility has substantially improved in functional terms due to the restructuring of the urban fabric. The construction of metro Line 23 along Longwu Road, which is the western boundary of the study area, will introduce two new stations within the area and is scheduled for completion in 2027. This planned infrastructure is expected to considerably enhance regional accessibility in the future.

The most notable change lies in the enhancement of spatial continuity and walkability following the implementation of the OROC initiative. The opening of a continuous pedestrian promenade and new cross-connections between previously enclosed industrial parcels created a permeable urban network linking the riverside to surrounding neighbourhoods. Prior to 2015, the waterfront was fragmented by factory boundaries and restricted access roads, limiting the reach of public transport and everyday mobility. By 2024, the transformation of these areas into open public corridors enabled seamless pedestrian and cycling routes connecting metro stations, bus stops, parks and cultural venues along the riverfront.

This spatial reconnection is likely to have particularly benefited non-motorised users and public transport commuters, as indicated by improved continuity of walking and cycling routes and their integration with metro access. This is consistent with the broader objective of promoting equitable and low-carbon mobility. Field observation in 2024 revealed that travel between the Longyao Road and Yunjin Road metro stations and the waterfront area can now be achieved entirely through barrier-free pedestrian routes, with continuous wayfinding and public amenities. This represents a qualitative enhancement of accessibility, helping to transform the area from a formerly segregated industrial enclave into an integrated part of the city’s public space network.

Nevertheless, accessibility gains remain spatially uneven. While the riverfront corridor has become highly connected, the connection with the inland side, particularly towards the west side of Longwu Road, still experiences lower permeability. These disparities suggest that the regeneration’s distributive benefits have concentrated along the primary scenic corridor rather than being evenly extended to the wider urban fabric. Addressing such internal spatial disparities will be essential for promoting more balanced accessibility and social equity in future stages of waterfront management.

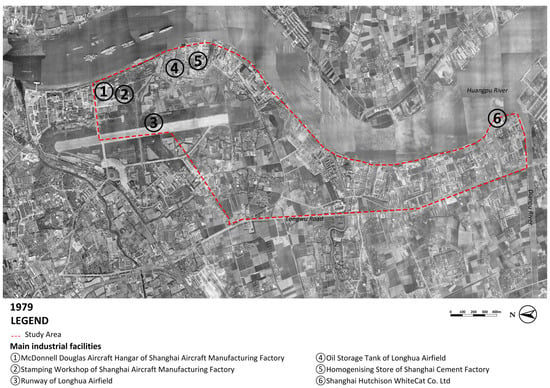

4.1.2. Park Accessibility and Open-Space Provision

The provision and accessibility of public parks form a key component of distributive justice, as they determine how recreational and environmental resources are shared across the urban population. Comparative interpretation of satellite imagery and field observations between 2015 and 2024 indicate a substantial transformation of land use in the Xuhui Waterfront, accompanied by a marked increase in green coverage and public access.

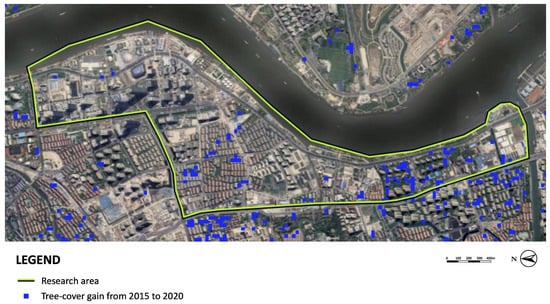

According to the land cover and use dataset [40], the proportion of vegetated land in the study area has increased 12 hectares, which covered approximately 3.7% of the study area, since the mid-2010s by 2020, largely due to the development of residential estates at the former industrial plots (Figure 8). In recent years, there were also newly created parks and linear corridors were incorporated into the West Bund Riverside Park, forming part of the OROC initiative, which aimed at ‘returning the waterfront to the public’ [34,37].

Figure 8.

New tree cover in the study area between 2015 and 2020: marked with blue pixels with resolution of 30 by 30 metres. Source: Author marked on Global Forest Watch interactive map.

The redevelopment introduced continuous pedestrian and cycling routes, improved visual permeability, and multiple public access points along the river. Field observation in 2024 confirmed that the public can now traverse the waterfront without interruption, a condition impossible before industrial clearance. The overall greening rate of the district has visibly increased, as reflected by the continuity of vegetated cover in remote-sensing images. Public use of the space has diversified, with jogging, cycling and open-air cultural events becoming common.

However, accessibility remains spatially uneven. The concentration of parks and high greenery levels along the riverfront contrast with the lower green coverage and limited small-scale parks in inland residential blocks at the central part of the study area. Thus, while overall access to open and green spaces has improved, the spatial distribution of these benefits continues to favour the most visible and tourist-oriented areas of the waterfront.

4.1.3. Environmental Quality

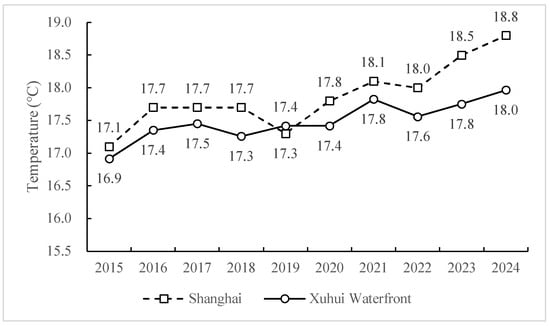

Environmental quality reflects both ecological performance and the comfort of the urban microclimate. In the Xuhui Waterfront, the tree cover is not only an indicator of open-space supply but also of ecological resilience. Dataset [40] showed a consistent increase in vegetated land throughout the study area, confirming the expansion of parks and green corridors. This higher green coverage ratio is generally associated with the literature with improved air quality, runoff retention and biodiversity along the Huangpu River corridor [44,45,46,47], even though these specific effects were not directly measured in the Xuhui Waterfront area.

Temperature data indicated a general warming trend consistent with the wider metropolitan area. Yet the observed temperature rise within the Xuhui Waterfront (1.1 °C) appears moderate compared with the citywide average (1.7 °C), suggesting that increased vegetation and the proximity of open water may help have contributed, alongside broader climatic and urban development factors, to a partial buffering local heat accumulation (Figure 9). Similar moderation effects have been reported in Shanghai’s other renewed waterfront districts [35].

Figure 9.

Annual mean temperature of entire Shanghai and Xuhui Waterfront. Source: Drawn by authors.

Planning documents also highlight environmental targets such as ecological shoreline restoration and storm-water management [37]. Nevertheless, greening remains spatially concentrated: the highest green ratios occur within riverside parks, whereas inner redevelopment plots exhibit less ecological planting. This selective distribution of vegetation produces unequal exposure to heat and environmental comfort, illustrating that environmental justice cannot be achieved solely through overall greening gains but requires a more even spatial distribution of ecological resources. These temperature comparisons therefore provide a tentative indication of relative environmental moderation along the Xuhui riverfront, while acknowledging that localised variations below the 30 m and 1 km grids may not be fully captured.

4.1.4. Housing Affordability and Gentrification

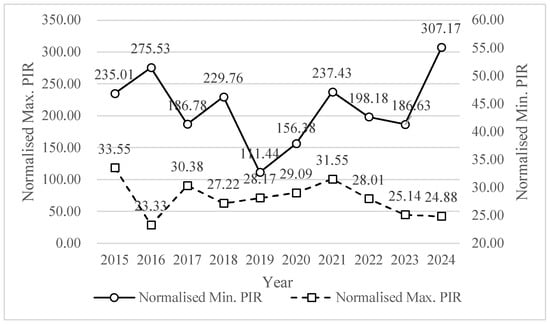

Based on the PIR-based housing affordability indicator described in Section 3.2.1, annual benchmark PIR values for Xuhui District between 2015 and 2024 were compiled together with per capita housing area, average second-hand housing prices and per capita disposable income (Table 2). For the 18 residential estates in the Xuhui Waterfront, the maximum and minimum estate-level PIRs in each year were calculated and then normalised against the district benchmark, and the resulting ten-year ranges are summarised in Table 3.

District-level average second-hand housing prices used in Equation (1) were derived from the gotohui.com platform (Table 2), while estate-level transaction records were obtained from fang.com. As both datasets report realised second-hand housing transaction prices in nominal Chinese Yuan for the Shanghai market, they were treated as directly comparable for the purposes of the PIR calculation. Nevertheless, potential inconsistencies in data collection between platforms and the absence of inflation adjustment may introduce noise into the estimates, so the analysis focuses on relative differences between estates and the district benchmark rather than on precise absolute PIR values.

The normalised PIR for the Xuhui Waterfront demonstrated a clear divergence (Figure 10). Over the ten-year period, the lowest PIR values became progressively lower, while the highest PIR values increased sharply. This polarisation revealed a growing inequality in affordability. For some households, typically those with higher incomes or stronger purchasing power, affordability improved, as income growth outpaced the increase in housing prices, or because they purchased in sub-areas where price growth was more moderate. For others, particularly middle- and lower-income households, affordability worsened, as their incomes lagged behind escalating property prices, leading to higher PIRs and greater financial burden.

Figure 10.

Normalised maximum and minimum PIRs of the transactions in Xuhui Waterfront from 2015 to 2024. Source: Drawn by authors.

This divergence suggested both social stratification and spatial polarisation. Estates with premium views, high-quality amenities and proximity to cultural institutions attracted substantial demand, producing PIRs far above the district average. In contrast, less attractive or peripheral estates displayed lower PIRs, creating an appearance of improved affordability. However, this was often a reflection of weaker demand, limited public service provision or reduced long-term development potential, rather than genuine improvements in accessibility.

From a broader perspective, the imbalance highlighted a decoupling between income growth and housing market dynamics. If overall income levels could not keep pace with the growth of property prices in high-demand areas, it implied that speculative or investment-driven demand was contributing to market escalation. Conversely, lower PIRs in marginal estates could be associated with population outflow or stagnating demand.

The implications of this polarisation are potentially significant for social equity. The PIR patterns suggest that ownership in the renewed riverside market is increasingly skewed towards households with higher purchasing power, while households with lower incomes may face growing barriers to entering or remaining in the local housing market. These tendencies echo patterns observed in other cities, where urban renewal has been associated with gentrification and displacement risks [15,19]. In this context, the combination of rapidly rising PIRs in many residential estates, the concentration of cultural venues and the escalating demand for riverside properties can be interpreted as indicative of emerging gentrification pressure in the Xuhui Waterfront, even if the present dataset does not allow direct measurement of displacement.

4.2. Procedural Justice: Participation and Governance

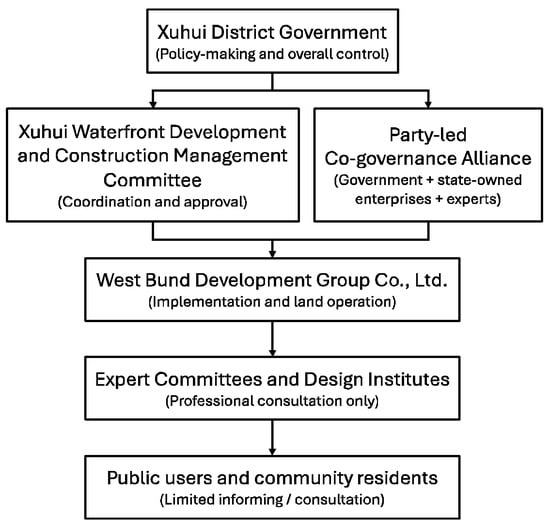

Procedural justice in the Xuhui Waterfront urban renewal reveals a path-dependent governance structure that evolved from a state-led planning tradition. Since the early 2000s, planning and decision-making for the Huangpu River waterfront, including the Xuhui section, have been characterised by administrative coordination, expert consultation, and enterprise implementation, with limited forms of civic participation [7,10].

In 2006, the Xuhui Waterfront core area underwent extensive redevelopment guided by international urban design competitions organised by government agencies. The planning authorities together with international design teams formulated an integrated redevelopment vision covering transport, landscape, urban image and historic environment conservation [33]. However, while the process involved government departments and professional experts, it did not mention public consultation or hearings, reflecting a technocratic and elite-led decision-making model. Public participation was framed mainly as future use rather than present involvement, laying the institutional foundation for subsequent governance patterns.

The establishment of the Xuhui Waterfront Comprehensive Development and Construction Management Committee and the West Bund Development (Group) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) in 2012 formalised this model of top-down coordination. The committee acted as the overall policymaker and the enterprise as the implementing body, jointly managing land consolidation, infrastructure construction, and investment attraction. This structure ensured project efficiency but reinforced a hierarchy in which administrative and corporate actors dominated the planning process.

During the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), the district government emphasised ‘cross-departmental collaboration and state-owned enterprise leadership’ to sustain large-scale construction [34]. In the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), procedural coordination was further institutionalised through the ‘Party-led regional co-governance alliance’, which integrated government agencies, enterprises and expert committees under unified objectives [37]. Although framed as co-governance, this alliance primarily enhanced inter-organisational coordination rather than participatory governance (Table 4).

Table 4.

Evolution of public participation mechanisms in the Xuhui Waterfront renewal.

Public-facing engagement mainly took the form of service-oriented outreach and branding. Initiatives such as the Shui’an Hui (水岸汇, literarily Waterfront Link) service brand and the Smart West Bund digital management platform aimed to improve public experience and administrative responsiveness rather than to empower civic participation [48]. The West Bund Co-Governance Alliance reported in local media was composed mainly of government departments, state-owned enterprises and experts, with little representation of residents or NGOs [49]. Environmental impact assessments and planning documents were publicly disclosed through official online platforms, but these mechanisms served primarily to inform and collect limited feedback rather than to foster deliberation or shared decision-making (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Governance and participation framework of Xuhui Waterfront. Governance flow: decision-making authority concentrates upward, while downward communication is mainly informational and service-oriented. Source: Drawn by authors.

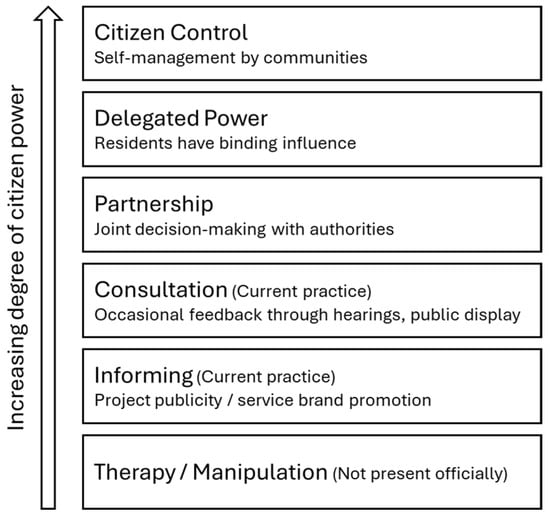

Viewed through Arnstein’s participation ladder [10], the Xuhui Waterfront’s participatory practice corresponds to the lower rungs of informing and consultation, rather than partnership or citizen control (Figure 12). The governance model has achieved managerial coherence and delivery efficiency but remains weak in inclusiveness and deliberative depth. For future urban renewal phases, enhancing procedural fairness would require the introduction of structured public workshops, community advisory committees and transparent feedback channels to move towards a more participatory governance framework.

Figure 12.

Arnstein’s ladder of participation and the position of Xuhui Waterfront: participatory channels exist but remain top-down and limited in influence. Source: Drawn by authors.

4.3. Recognitional Justice: Cultural Identity and Heritage Representation

Recognitional justice in the Xuhui Waterfront urban renewal concerns whose histories, values and cultural identities are represented and celebrated in the transformation of the district. Since the early 2000s, the area has been reframed from an industrial production zone into a flagship cultural corridor under the ‘West Bund’ brand. This transformation demonstrates how heritage and cultural representation have been strategically mobilised to construct a new urban identity for Shanghai, while also revealing tensions between elite-oriented cultural production and inclusive heritage recognition.

During the preliminary stage of its renewal, the masterplan for the Xuhui Waterfront explicitly integrated the adaptive reuse of industrial remains, including the former Longhua Airport hangars and the Shanghai Cement Plant, as core landscape and architectural elements [33]. The urban design competition entries preserved industrial textures and proposed the conversion of factory structures into cultural venues, museums and creative clusters. This vision linked modern urban design with historical continuity, but the narrative of preservation remained framed within professional and governmental discourses rather than community-led heritage appreciation.

In the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), the district government established the ‘Art West Bund’ cultural brand, positioning the waterfront as ‘a world-class waterfront cultural landmark integrating art, science and lifestyle’ [34]. This initiative led to the opening of the West Bund Art Museum (operated in partnership with the Centre Pompidou) and the annual West Bund Art and Design Fair, which together formed the centrepiece of Shanghai’s creative economy. The cultural image of the waterfront thus shifted from an industrial landscape to an international art destination. However, the cultural representation largely catered to the global art market and affluent consumers, rather than reflecting the everyday cultural experiences of local residents and workers displaced during redevelopment.

The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) reinforced this approach, promoting the ‘West Bund Culture and Art Belt’ as part of Shanghai’s ‘Global City of Culture’ initiative [37]. While the plan emphasised ‘cultural confidence’ and ‘heritage activation’, it prioritised high-profile art institutions, such as the TANK Shanghai (converted from disused oil tanks), over community-based cultural facilities. Public events, art festivals and waterfront exhibitions improved cultural accessibility in physical terms but did not necessarily broaden cultural representation. The artistic narrative emphasised modernity and global connectivity, potentially overshadowing local memory and working-class heritage that once defined the area’s identity.

From the perspective of recognitional justice, the Xuhui Waterfront exemplifies the selective heritage activation that accompanies globalised cultural urban renewal. Industrial heritage has been preserved aesthetically but recontextualised to serve the creative economy and urban branding. The process privileges symbolic recognition over participatory interpretation, as cultural representation remains largely curated by state and corporate actors. As Fraser argues, genuine recognitional justice requires both representation and parity of participation in the cultural domain [11]. To advance such justice, future cultural planning in the West Bund could incorporate participatory heritage interpretation programmes, community exhibitions, and educational initiatives that reconnect local narratives with the regenerated cultural landscape.

5. Discussion

5.1. Expansion of Waterfront Access and Cultural Benefits

The continuous opening of the Xuhui Waterfront illustrates a set of intertwined trends around access, environmental quality and the public presence of industrial heritage. Similar patterns have been observed in other post-industrial waterfront projects, where continuous riverside open-space corridors have improved public access and environmental amenities while reshaping urban riverfronts [1,3,4,24,25,35]. At the spatial level, the removal of industrial enclosures and the establishment of a continuous riverside promenade have reconnected previously fragmented industrial parcels through pedestrian and cycling routes, allowing a much wider range of residents and visitors to enjoy direct contact with the river for the first time in decades. This has substantially reduced the physical segregation between the city and the waterfront and has helped to fulfil the policy vision of ‘returning the river to the people’. At the same time, the creation of green space and vegetation is likely to have improved local environmental conditions and mitigated urban heat exposure, as suggested by the enhancement of tree cover and temperature indicators. These changes of indicators point to measurable gains in environmental amenity and recreational opportunities at the scale of the wider metropolis, even though detailed environmental quality metrics were beyond the scope of this study.

Industrial heritage has also been brought into the cultural mainstream. A number of large-scale industrial buildings, such as the former Longhua Airport hangars and oil tanks, have been preserved and transformed into public cultural facilities including the Long Museum, TANK Shanghai and the West Bund Art Museum. These conversions safeguarded the physical remains of industrial structures while providing new platforms for contemporary art, exhibitions and leisure activities. Rather than being demolished or relegated to the background, workers’ landscapes have been reframed as part of Shanghai’s cultural portfolio. From the perspective of distributive and recognitional justice, these trends indicate that high-quality public space and curated encounters with industrial history have become more widely available, even though the depth, inclusiveness and everyday accessibility of such cultural benefits remain subject to further scrutiny.

5.2. Bounded Equity, Socio-Spatial Polarisation and Emerging Gentrification

At the same time, the empirical results reveal that these gains are accompanied by bounded forms of equity and emerging socio-spatial polarisation. The analysis of PIR showed that the housing affordability within the study area became increasingly polarised over the past decade: while some estates experienced relatively moderate PIR levels, others, especially the new riverfront developments with premium amenities, recorded very high PIRs. The sharp divergence between the highest and lowest PIR values indicates that the renewal has been associated with differentiated housing trajectories and a widening gap between more and less affordable compounds. Generational disparities also appeared to widen. The PIR results suggest that younger or lower-income residents found it increasingly difficult to enter the local housing market, whereas older residents who benefited from early property ownership gained substantial asset appreciation. This trajectory is consistent with a gradual shift in the social composition of the area towards higher-income residents. Historically, the area was closely associated with working-class and industrial communities, and the observed PIR polarisation suggests that these groups may now be under increasing pressure, although detailed demographic data on in- and out-migration were not available for this study.

These dynamics resonate with the literature on waterfront-led gentrification, where environmental upgrading and cultural branding often coincide with rising property values and selective inclusion [19,26,31,32]. Concerns about the commodification of public scenery, class-based transfer of property interests and lifestyle replacement have been documented by researchers [50,51]. The environmental assets become vehicles for middle-class consolidation rather than broad-based social inclusion. Regarding the case of Xuhui Waterfront, although the waterfront corridor is physically open to all, the cost of living and housing in adjacent areas filters who can reside nearby and make regular use of the facilities. The waterfront thus operates as a bounded public realm—accessible in principle, but more easily appropriated by groups with higher purchasing power and cultural capital. From a social justice perspective, this pattern suggests that the project simultaneously enhances certain dimensions of accessibility while reproducing or even intensifying socio-spatial boundaries, with different implications for different social groups.

5.3. Understanding the Duality: Fiscal Mechanisms and Structural Constraints

The dual nature of the Xuhui Waterfront’s social outcomes needed to be understood in relation to the wider governance and fiscal regime of Chinese urban renewal. Studies of state entrepreneurialism argued that Chinese cities had been governed through a combination of strong planning centrality and market instruments, with local governments acting through the market to extract land and property values for development finance. Within this model, public-realm and cultural investments were closely tied to land-lease income and property-led growth, and flagship projects were expected to enhance the city’s competitive image while generating new resources of revenue (Figure 13). Existing research on Shanghai’s waterfront and other industrial-area redevelopments showed that such financialised redevelopment strategies tended to prioritise value capture over redistribution, which inevitably narrowed the flexibility for more equity-oriented approaches to planning and participation [29,35,36,43,52,53,54].

Figure 13.

High-rise buildings in Xuhui Waterfront, indicating its identity as an emerging business district. Source: People’s Government of Xuhui District.

From this perspective, the duality observed in the Xuhui case was not merely the outcome of local design decisions, but related structural constraints embedded in the prevailing land-finance and governance system. Similar tensions had also been documented in the studies about inner-city renewals, where redevelopment schemes improved environmental conditions and land-use efficiency yet also displaced long-term residents and weakened everyday social networks [55,56,57]. Different renewal approaches reconfigured the urban morphology while restructuring tenure relations and social composition [58]. These lessons revealed the difficulty of balancing modernisation, heritage conservation and social justice through project-based interventions.

Alongside these cases, the Xuhui Waterfront illustrated how industrial-heritage-led waterfront renewal could simultaneously deliver high-quality public environments and cultural amenities and produce new forms of exclusion through class-biased residential development. Rather than an isolated exception, this pattern appeared as a manifestation of a broader contradiction in contemporary Chinese urban governance, in which state entrepreneurial strategies and land-based fiscal dependence limited the institutional space for more redistributive or participatory models of urban renewal.

5.4. Towards Economically and Socially Sustainable Renewal Models

The experience of the Xuhui Waterfront demonstrated that achieving social equity in industrial heritage renewal required not only equitable spatial design but also a financially sustainable governance structure. Reliance on land-lease revenues and high-end real-estate development to recover public investment had proved efficient in the short term but had also intensified spatial inequality and gentrification. To balance fiscal sustainability with inclusiveness, alternative approaches were observed in international practice, which suggested that large-scale industrial or waterfront urban renewal could be advanced through three complementary pathways: incremental phasing, public–private partnership (PPP) collaboration and guided self-renewal under public planning supervision.

The first approach emphasised scaling down project phases to allow gradual transformation of large sites. This model distributed financial risk over time, reduced the fiscal burden on local authorities, and enabled adaptive feedback from communities. The long-term transformation of London’s South Bank along the River Thames provided a pertinent example. Rather than adopting a single masterplan, regeneration unfolded through successive, smaller interventions by multiple actors, resulting in an ‘organic approach’ to urban change that evolved over several decades [59]. The gradual strategy not only mitigated speculative pressure but also created conditions for diverse social participation and mixed land uses. As a result, it achieved a higher degree of both economic resilience and social equity than large-scale one-off redevelopment, demonstrating that incremental renewal could produce enduring and inclusive urban outcomes.

The second approach relied on the introduction of social and private capital through PPP mechanisms, which distributed investment risks and extended the life cycle of operation and maintenance. The Porto Maravilha project in Rio de Janeiro exemplified this model. The scheme established an innovative PPP structure to implement the regeneration of the old port area in cooperation with the private sector [60]. Under the contractual arrangement, the public authority provided land preparation, infrastructure and regulatory coordination, while the private consortium undertook construction, operation and commercial development. Revenues and responsibilities were shared through long-term concessions and performance-based returns. Although the project also faced challenges such as displacement and social tension [61], its financial model demonstrated how public and private interests could be aligned to achieve both economic sustainability and public-realm enhancement. When social clauses were embedded in the PPP agreement, such as community benefits or affordable housing, distributive justice and accessibility could be further improved.

The third approach encouraged partial self-renewal by property owners or enterprises under a clear planning and heritage-protection framework. This model reduced the state’s direct fiscal responsibility while maintaining planning control and public benefit. The transformation of The Mills in Hong Kong illustrated this strategy. The privately funded project was guided by government planning policies but implemented independently by the Nan Fung Group, which converted the former textile factory into a creative and cultural complex [62] (Figure 14). This approach preserved industrial heritage, activated community memory and provided accessible cultural space without relying on large public expenditure. By enabling local initiative within regulatory guidance, the scheme achieved a balance between economic feasibility and social inclusion, supporting recognitional and distributive aspects of social equity.

Figure 14.

The Mills, aligning with its surrounding landscape after Nan Fung Group’s self-founded renewal. Source: taken by authors.

Taken together, these three models suggested that, in light of the tensions between fiscal dependence and social equity documented in the Xuhui Waterfront, future large-scale industrial heritage and waterfront renewal in China could explore combinations of financial diversification and inclusive governance rather than solely on land-finance-led schemes. Incremental phasing may ease fiscal pressure and enhance long-term adaptability; PPP collaboration may mobilise private investment while maintaining public oversight; and guided self-renewal may empower local actors to contribute to heritage conservation and community life within a clear planning framework. Although these propositions require further testing in other contexts, embedding social equity principles within such economically oriented mechanisms could help future waterfront renewal to reduce dependence on land-lease revenue and move towards more inclusive and balanced urban transformation.

6. Conclusions

The transformation of the Xuhui Waterfront under the OROC initiative provided a distinctive example of how post-industrial waterfront renewal in China could simultaneously advance heritage conservation, public-space creation and environmental improvement. Rather than labelling the Xuhui Waterfront renewal as either a success or a failure, this study highlights how the same project can expand public access and environmental quality while intensifying socio-spatial differentiation, with the balance of perceived gains and losses varying across different social groups and political standpoints.

This study demonstrated that the continuity of the riverfront and the adaptive reuse of industrial heritage achieved meaningful progress in distributive and recognitional justice. Public access to the waterfront had been greatly expanded, industrial structures were preserved and re-imagined as cultural facilities, and the overall environmental quality of the river corridor was enhanced. These achievements collectively represented a tangible form of social equity realised through spatial openness and cultural enjoyment.

Nevertheless, the research also revealed that such equity remained limited. The analysis of housing affordability indicated polarised trends, with rapidly rising property values associated with socio-spatial stratification and signs of emerging gentrification. Generational and class differences also appeared to be accentuated, as higher-income residents were better positioned to benefit from the renewed environment and housing market. These findings underscored the persistent tension between the symbolic inclusiveness of public space and the economic exclusivity of adjacent development. The dual character of the Xuhui Waterfront’s outcomes was rooted in the fiscal structure of China’s state-led urban renewal. The substantial capital required to redevelop industrial land and construct high-quality public environments had compelled local governments to rely on land-lease revenues and property-led growth. This financial dependence constrained the scope of social participation and reinforced market-driven inequality. The Xuhui case therefore exemplified a broader paradox in contemporary Chinese urban renewal: the state’s capacity to deliver spatial and environmental improvements was accompanied by fiscal mechanisms that often undermined distributive and procedural fairness.

To move towards more economically and socially sustainable models, the analysis of the Xuhui Waterfront was combined with the national and international examples to outline three interrelated pathways. Incremental and phased renewal suggests that gradual and adaptive development could disperse financial risk and accommodate diverse social actors. PPP models indicate how shared investment and long-term concession frameworks could align public goals with private resources when equity clauses are incorporated. Guided self-renewal under public-planning frameworks shows how local initiative and heritage preservation could coexist with financial autonomy. These pathways are not presented as prescriptive models but as heuristic directions that respond to specific problems revealed in the Xuhui Waterfront and that could be further explored in other Chinese urban renewal initiatives. Together, they tentatively point to approaches in which China’s existing state-dominated renewal mechanisms might be complemented to achieve a better balance between financial feasibility and inclusiveness.

Theoretically, this research contributed to extending the discourse on social equity in heritage and waterfront contexts by integrating distributive, procedural and recognitional justice within a unified analytical framework. This approach enabled an assessment that went beyond aesthetic or environmental outcomes to address who benefited, who was excluded and how cultural identities were represented, bridging the conceptual gap between social-justice theory and spatial-planning practice in the Chinese context. Practically, the study proposed a replicable multi-indicator framework that combined spatial accessibility, environmental metrics, housing affordability and governance evaluation, offering policymakers a systematic method to assess social equity in urban renewal projects. By identifying alternative renewal pathways, the research also provided actionable insights into how fiscal sustainability and social fairness could be pursued concurrently.

Several limitations remained. The empirical analysis was constrained by data availability and temporal coverage, as it relied primarily on secondary sources and transaction records between 2015 and 2024. The tree-cover- and temperature-based environmental indicators were derived from moderate-resolution datasets and therefore reflected general tendencies at the waterfront-corridor scale rather than microclimatic conditions at the level of individual plots or streets. The PIR indicators, which combined municipal averages for income and housing space with district-level housing prices, were interpreted as relative measures of affordability pressure and social stratification instead of precise estimates of the housing cost burden for particular income groups. In addition, procedural and recognitional justice were examined mainly through policy documents, planning guidelines, consultation summaries and other documentary sources rather than direct participatory data, so the analysis primarily captured the design of formal institutions and dominant policy narratives rather than the full spectrum of residents’ living experiences. Future research could therefore broaden the empirical basis by incorporating longitudinal social surveys, participatory mapping and stakeholder interviews to capture dynamic perceptions of equity. In methodological terms, the present study remains primarily descriptive and indicator-based; future work could complement this by applying multivariate or inferential techniques where data availability permits. Comparative studies across different Chinese cities and international contexts could further test the transferability of the analytical framework and refine strategies for achieving economically viable yet socially just heritage conservation.

In summary, this study demonstrated that embedding social-equity principles within economically sustainable mechanisms was crucial for the long-term success of industrial heritage renewal. By transcending reliance on land-finance models and integrating inclusive governance with diversified funding, future waterfront urban renewal in China could more effectively reconcile heritage conservation, urban vitality and social fairness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Q.D.; Data curation, B.Q.; Formal analysis, B.Q.; Funding acquisition, T.K.; Investigation, W.Z.; Methodology, B.Q.; Supervision, T.K.; Visualisation, W.Z.; Writing—original draft, Q.D. and B.Q.; Writing—review and editing, Q.D. and B.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [52408028]; and the Key Scientific Research Base of Urban Archaeology and Heritage Conservation (Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology), State Administration of Cultural Heritage of China [2024CKBKF05].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OROC | ‘One River, One Creek’ |

| PIR | price-to-income ratio |

| PPP | public–private partnership |

References

- Evans, C.; Harris, M.S.; Taufen, A.; Livesley, S.J.; Crommelin, L. What does it mean for a transitioning urban waterfront to “work” from a sustainability perspective? J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2025, 18, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angradi, T.R.; Williams, K.C.; Hoffman, J.C.; Bolgrien, D.W. Goals, beneficiaries, and indicators of waterfront revitalization in Great Lakes Areas of Concern and coastal communities. J. Great Lakes Res. 2019, 45, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Waterfront regeneration as a political mission: Megaprojects under state entrepreneurialism. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, N.; Fischler, R. Social and Environmental Justice in Waterfront Redevelopment: The Anacostia River, Washington, D.C. Urban Aff. Rev. 2020, 56, 1779–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. The just city. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]